|

ACADIA

The Sieur de Monts National Monument and its Historical Associations Sieur de Monts Publications XVII |

|

THE WHITE MOUNTAIN NATIONAL FOREST

HERBERT A. SMITH.

FOREST SERVICE EDITOR.

The Federal Government is building up a National Forest in the White Mountain region of New Hampshire by the purchase of the necessary lands from private owners. As the lands are bought they are put under administration. The first land was bought in 1913. By the close of 1916 title had been acquired to 205,289 acres, and arrangements had been completed for the purchase of 76,970 acres more. The total acquired or covered by approved contracts of sale at the opening of the summer of 1917 is 375,000 acres.

|

This is equal to about half of what may be called the main mass of the White Mountains — the region stretching from the southern base of the Sandwich range on the south to the Ammonusuc and Moose River Valleys on the north, and including the Presidential, Carter, and Franconia Ranges. Ultimately the Forest will probably reach a size of something like a million acres. This is about the average size of the National Forests which the Government has established in the mountain regions of the West, out of the public lands. It will carry the Forest northward over the mountains beyond the Ammonusuc and Moose Rivers as far as and including the Pliny Range. Some of the land already bought lies in this northern extension of the White Mountain region.

The Government is buying up these forested mountains in order that all the interests of the public in their right use and protection may be fully safeguarded through orderly, intelligent development of their value. The Nation is taking over in the White Mountains a productive resource, in order that it may continue to be productive, and productive of all the public benefits which can be realized with skillful management. These benefits are chiefly the regulation of water supplies, the sustained yield of wood, and the enjoyment by the people of the rare recreative and scenic value of the region. To adjust and harmonize these diversified forms of use so that all may go on at once without needless sacrifice of one to another, and with preference for that of highest public value where interests conflict, is the task which the Government has undertaken.

|

| MOUNT WEBSTER — FROM MOUNT WILLARD |

Unrestricted private ownership of mountainous forest land risks the sacrifice of important public interests to individual interests, waste and impairment of the resources, and, in the end, widespread devastation. In the White Mountains recognition of the public loss began nearly forty years ago. The cutting of the virgin forests by lumbermen and the ravages wrought by fire aroused inquiry for some method of protecting the interests of the public. But it was not until 1911 that legislation authorizing protective measures was secured. In that year Congress provided for the acquisition by the Government of lands whose control would "promote or protect the navigation of streams on whose watersheds they lie" — the so-called Weeks Law. In accordance with this law, the Nation is now purchasing the White Mountain land, but much of it without the original stand of timber, and some of it so desolated by fire that the restoration of timber growth can take place only after the lapse of many years.

Nevertheless, action came not too late to save the glory of New England's finest mountains, for the present generation and for all time. Scarred though their sides and summits are by occasional disfiguring breaks in the forest mantle of living green, dark-hued where the spruce and fir wrap the upper slopes, emerald and vivid below the evergreen belt where the hardwoods crowd into the conifers, they are still to the eye much what they were a hundred years ago.

Even then visitors had begun to pilgrimage into the almost unbroken wilderness that stretched from the uplands of the Connecticut Valley to the Maine border and from Winnipesaukee to Canada, to look upon the rugged "White Hills" in their lonely grandeur. These first pilgrims, forerunners of the tens of thousands who each summer now make the easy journey from point to point in luxury, found rude accommodation in the occasional cabins of pioneer settlers.

|

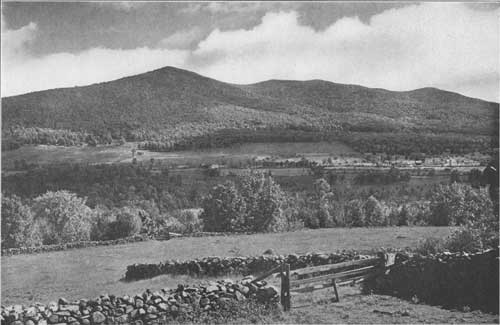

| STARR KING MOUNTAIN |

In 1797, and again in 1803, President Timothy Dwight of Yale College rode on horseback up the Connecticut Valley and through the Crawford Notch. An account of what he saw is given in his "Travels in New York and New England," published in 1823. Settlement of the country back from the valley towns was at an early stage; the roads were of the worst, the houses few and scattered. Yet the ravages of fire had begun.

"When we entered upon this farm in 1803," he wrote, "a fire which not long before had been kindled in its skirts had spread over an extensive portion of the mountain on the northeast; and consumed all the vegetation, and most of the soil, which was chiefly vegetable mould, in its progress. The whole tract, from the base to the summit, was alternately white and dappled; while the melancholy remains of half-burnt trees, which hung here and there on the sides of the immense steeps, finished the picture of barrenness and death."

Thomas Starr King refers in his admirable work, "The White Hills; Their Legends, Landscape, and Poetry," to the devastation of Mount Crawford by a great fire which, according to "old Mr. Crawford," occurred about 1815. "The time may well arrive," he writes, "when careful records of these irreparable mischiefs, which destroy in their progress the very vitality of our mountains, and leave nothing but crumbling rocks, the shelter of a strange and spurious vegetation, — nothing but the ruins of nature — shall possess a mournful value." But it was not until a much later day, when the lumbermen began to operate extensively in the pure spruce forests of the upper slopes, that the fire menace reached a point at which public sentiment became sufficiently aroused to demand with insistence some efficient remedy.

It was the arrival of the era of the railroad which really opened the White Mountains to the public. Through the first half of the nineteenth century their spreading fame drew a slowly increasing number of travelers into the region, in spite of the obstacles presented by indifferent accommodations and lack of transportation facilities.

In 1819 Abel Crawford opened a footway to Mount Washington, and in 1822 Ethan Allen Crawford opened a road along the Ammonusuc; these attracted attention and visitors. But in 1837, King tells us, the White Mountains were still a secluded district where the inns offered "only the homely cheer of country fare, and the paths to Mount Washington were rarely trodden by any one who did not prize the very way, rough as it might be, too much to search for easier ones."

|

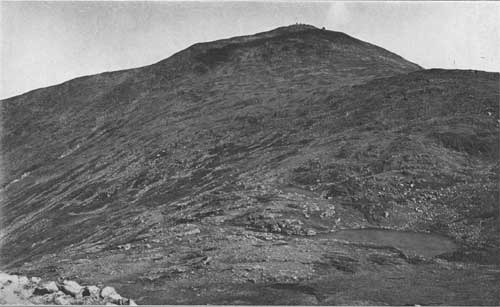

| MOUNT WASHINGTON AND THE LAKES OF THE CLOUDS |

In 1840 the first horse was ridden to the summit. The decade which followed was that in which railroads began to play a part in the economic development of the State. From the middle of the century on, the popularity of the White Mountains grew fast.

In 1846 there was published in Boston "The White Mountain and Lake Winnepissiogee Guide Book"; and from 1849 to 1859 there was an average of a new guide book a year for White Mountain travelers. One published in Concord, N. H., in 1850 makes mention of the Mount Washington House, kept by Horace Fabyan, as containing about 100 rooms, "new, light, and airy, the majority erected during the last two years." At Littleton, the White Mountain House, "one of the most pleasant and convenient stopping places to be found any where on the route," is "fitted up in the most modern style regardless of expense, and everything desirable or usual in hotels is there found." Between such points of resort stages ran regularly for the tourists. Even though the encomiums of the guide books are liberally discounted, they show how the summer visitors were coming in.

In the period of prosperity and expansion which came in the seventies the number of persons in the East seeking summer recreation increased apace. The vacation habit was forming. By 1880 the commercial value to the State of the yearly influx of visitors and tourists had become fully recognized as of very great importance. At the same time, the development of private lumbering operations and the ravages of forest fires after lumbering were producing results that called forth vigorous protests against the despoliation of the forests and the marring of scenic beauty.

In 1881 conditions had reached a point which brought about action by the State. A commission was created by the legislature to inquire into the extent to which the forests were being destroyed, and into the wisdom or necessity for the adoption of forest laws.

|

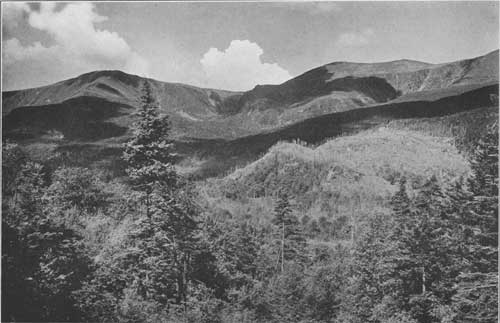

| MOUNT WASHINGTON FROM PINKHAM NOTCH — SHOWING TUCKERMAN'S RAVINE |

The report of this commission pointed out that at least half the State was most valuable for permanent timber production, that the great waterpowers within and without the State demanded forest preservation, and that the scenic and recreation value of the region was much too important as a State asset to be recklessly sacrificed. Thus the reasons for preventing the evils inevitable under private ownership and unrestricted exploitation of the forests were even at that time recognized. That nevertheless it took a full generation to secure a remedy was not for lack of knowledge of the need to do something, but because a course of action which would put a stop to the admitted evils and which public sentiment would support had not been found.

In the meantime, destruction of the forest was advancing at a rapidly accelerating pace. In 1850 the reported value of New Hampshire's lumber cut was a little over one million dollars; in 1870, over four and a quarter million; in 1890, over five and a half million; and in 1900, nearly nine and a quarter million. And this progressive drain upon the forest resources of the State was accompanied by a change in the methods used, which made the lumbering more and more destructive.

First the white pine was cut out. Then the spruce of the lower slopes bore the brunt of the attack. As the demand for lumber increased it paid to cut smaller and smaller trees, with the result that lumbering grew steadily more intensive. In the earlier stages, the cutting was to a large extent a preliminary to agricultural development. Since the forest in the lower and less rugged portions of the region was typically mixed hardwoods and conifers, or "softwoods," and since it was chiefly the latter which the lumbermen sought, the lumbering in this form of growth did not as a rule strip the land. But as the century advanced towards its close, the loggers began to reach the pure spruce timber which protected the upper slopes.

|

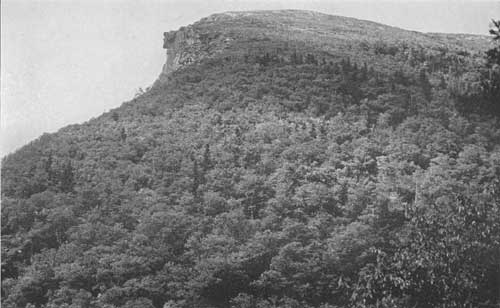

| MIXED WOODS BELOW THE PROFILE |

A rapidly developing pulp industry for the manufacture of newsprint paper opened a market for material too small for the lumber manufacturer. Moreover, when the scene of operations was the thin-soiled upper slopes covered with conifers it did not pay to leave anything behind which had a sale value, for whatever remained was likely to be blown down by the wind. The debris in the wake of the logger became a fire-trap of the most formidable character. Protection against fire was not worth its cost to the private owner, whose interest was limited to getting all that he could from the existing stand. Left to itself, therefore, natural economic development could have but one result — the sweeping out of existence of the timber resource and the final desolation of the entire region above the hardwoods.

It was the growing perception of this fact that brought the awakening of the public to a sense of what it had at stake. But how to apply a remedy was a difficult question. The State commission appointed in 1881 made its report in 1885, but proposed no constructive program beyond a plan for the inauguration of a system of fire protection of a primitive and inadequate character. A second commission, appointed in 1889, reported in 1891 that the cost of State forest ownership on an extensive scale was too great to make this course practicable. It did, however, recommend purchases by the State of "carefully selected sections of the mountain region, of small extent, to be held perpetually and so cared for and protected that their natural wild attractiveness shall be permanently maintained."

An outcome of the report of this commission was the creation, in 1893, of a permanent State Forest Commission. Partly through purchase and partly through gift, the State has come into possession of a number of small tracts containing in all about 9,000 acres. But by the beginning of the present century the logic of the situation was beginning to make clear that if the large problem was to be solved it must be solved quickly, and on broader lines than those along which State action could be looked for.

|

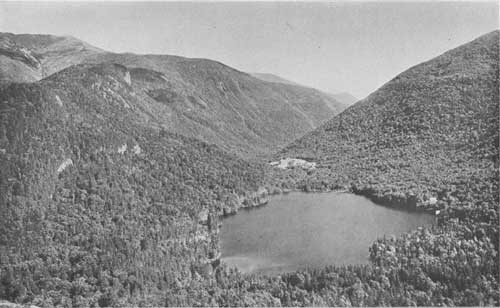

| A FOREST SCENE — ECHO LAKE FROM BALD MOUNTAIN |

Organized effort for Federal ownership began in 1901. It was set on foot partly by residents of Massachusetts, who realized that the interests affected were not limited to New Hampshire. Two years later, the first bills providing for the purchase of lands in the White Mountains were introduced in Congress. But the plan at first found small favor. Forestry as a national undertaking was still in its early infancy, if indeed it could fairly be said to have been born. Some sixty-two million acres of "forest reserves" had been created in the West, but plans for putting their resources to good use had not been devised and only the most rudimentary administrative provision for their care had been made. In short, they were reserves in every sense of the word — Government property metaphorically placarded "Keep Out!" and locally unpopular as obstacles in the path of economic progress. The expenditure of Federal funds to buy eastern forest lands was regarded askance, as a proposal to embark on a new and dangerous policy involving both the use of public funds for local and uncertain benefits and the extension of government into a field of activity which it should not enter. Political orthodoxy was shocked at the thought of what might happen if national ownership and management of this form of property were to begin.

Year after year the legislation was brought forward only to be defeated. It was soon combined, however, with the proposal for similar legislation in the southern Appalachians which had arisen independently still earlier. As the movement for Federal action gained strength, opposition was based largely on the ground that the bills were unconstitutional. But in the end the rising tide of public sentiment carried the law through — the so-called Weeks Law. By limiting the purchases to lands necessary to the regulation of the flow of navigable streams and providing for a determination of the fact that national control of the lands to be purchased would promote or protect navigation, the question of constitutionality was successfully met.

It was the interstate importance of the White Mountain region which from the outset furnished the main reason for Federal ownership. While the interstate character of the benefits aimed at was conspicuously in evidence in the matter of stream protection, it was by no means confined to this form of public benefit.

|

| LAKE GLORIETTE |

As a recreational region, the White Mountains, it was pointed out, have a large value for all the Northeastern and many of the Central States, forming as they do a resort for great numbers of visitors from Boston, New York, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Chicago, and other cities and towns of the populous territory east of the Mississippi. Similarly, the forests of the White Mountains are industrially important as sources of timber supply for manufacturing establishments in the States surrounding New Hampshire, whose products go into all parts of the country. But of outstanding significance was the influence of the White Mountain region upon the industrial and economic life of the New England States through its peculiar relation to their rivers, which are both arteries of commerce and sources of energy through water-power development.

Back from the ocean, for myriads of years, the streams have been cutting, in their age-long task of remaking the face of the earth, towards this central elevation from which the waters drain east, west, north, and south. Upon the mountain flanks their tentacles rest like a network of shining threads, deepening their channels and bearing slowly seaward what short-visioned man sometimes calls the everlasting hills. The White Mountain uplift is a central citadel into which the drainage system of northern New England is pressing from all sides. Maine, Massachusetts, and Connecticut use the waters which New Hampshire feeds into the Androscoggin, the Saco, the Merrimac, and the Connecticut. All four have their principal importance and use beyond the borders of New Hampshire. Protection of these streams against irregular flows and silting through erosion was manifestly a matter of interstate concern.

|

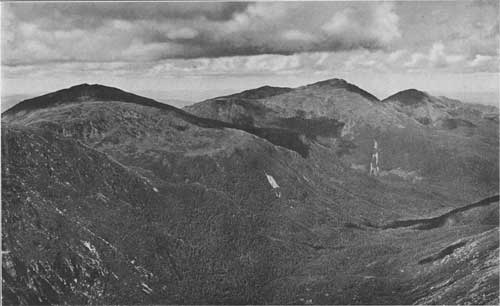

| GREAT GULF AND NORTHERN PEAKS — FROM MOUNT WASHINGTON |

These reasons for national action were reinforced by certain special considerations. New Hampshire, a State without great cities or extensive manufacturing districts, lacked the wealth which would have permittted it to assume without heavy sacrifice the burden involved in acquiring promptly and protecting adequately the White Mountain lands. Conditions had, however, reached a point which made it plain that if the forests were to be saved immediate action was necessary. The lumbering of the higher and steeper slopes was beginning, with spectacularly ruinous results. On these slopes, which were generally covered by pure stands of spruce, the almost inevitable fires after lumbering left little in their wake but bare rock; for the slash was both heavy and inflammable, and the soil itself so largely made up of vegetable matter that neither living trees nor seed on or in the ground nor anything in which trees could grow was likely to be left behind.

The beginning of the remedial action was delayed for a time after the enactment of the Weeks Law by the careful safeguards embodied in the Law itself, to prevent ill-considered purchases. Under these safeguards the Government has proved a good buyer, and it is believed that the lands could undoubtedly be sold again for more than they cost, were it desired to dispose of them. Thus the fears formerly expressed in some quarters that a purchase law would permit private owners to unload on the Government on terms more advantageous to themselves than to the public have proved unfounded. The first purchases in the White Mountains were made in 1913. As soon as the Government began to take title, plans for administration became necessary. Thus public ownership entered upon its final stage — that of organization and development on constructive lines.

The first requisite was fire protection. Organization of the territory into districts, each in charge of a forest officer, provides the necessary leadership. Fire fighting in the woods is a matter in which the men of the Forest Service have become proficient through long experience. It was a simple matter to adapt to local conditions the methods which had been worked out in the National Forests of the West. An elastic protective force is expanded to its maximum in the danger season, when a vigilant watch is kept by lookouts and patrol men. The protective force of the State forester assists in the work. Trails and telephone lines have been built where existing means of communication were most inadequate to the need; in the White Mountains, however, there is less urgent necessity for the Government to equip the Forest with such improvements than there is in the National Forests of the West and South. Sales of timber are being made for the primary purpose of cleaning up the forest and securing a better growth of timber. Incidentally, the returns from such sales are already reimbursing a large part of the cost of administration and protection, and are likely soon to equal the entire operating cost.

|

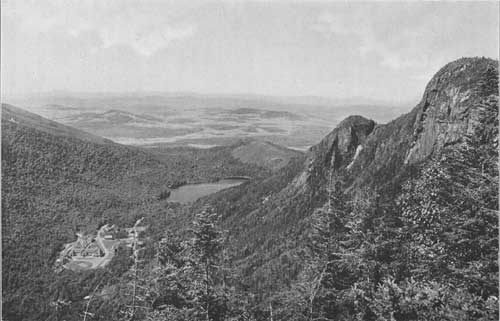

| FRANCONIA NOTCH FROM MT. LAFAYETTE |

All in all, though the work is so lately begun it is already effecting a very considerable change in the conditions. Not only has the progress of the forces of destruction been halted; there is in evidence a marked gain. The protection given for the past four years has prevented any considerable damage from fire, and some of the slopes which five years ago showed bald rock are now green with on-coming forest growth.

Perhaps even more important in the long run than these tangible and material benefits of public ownership has been the stimulus to a larger and clearer realization of the value of the region which Government leadership in its protection and development is bringing about. The mere fact that a permanent public enterprise has been entered upon through the creation of the White Mountain National Forest has increased the number of visitors, and has reacted upon local sentiment regarding the responsibility of private landowners to the public for a certain measure of co-operation as a part of good citizenship. Fire protection is now general and heartily aided by all classes of local residents. It is easier to secure lands needed by the Government on terms not dictated solely by a spirit of narrow self-interest. The organizations which are actively working for improved conditions and better facilities for enjoyment of the recreational and esthetic values of the region, of which the chief are the Appalachian Club and the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests, have been greatly heartened and strengthened by the creation and administration of the National Forest. In short, community participation in the project is a growing reality, and promises much for the welfare of the region.

The influence of the enterprise is felt far afield. Late in 1916 the various trail-building organizations of New England met in conference and decided to correlate their efforts with a view to developing a trail system under a general plan of wide scope. It is proposed to link up in this way the lake region of Maine, the White Mountains, the Green Mountains, and even the Adirondacks and the Palisade Park and New York City. Thus the pedestrian, whose simple pleasure in exploring the shady by-ways of rural New England has been largely taken away by the march of progress in the form of road improvement and whirring automobiles, may once again come into his own.

The fish and game resources of the White Mountains will under national management undoubtedly be markedly augmented. The streams are already stocked to some extent with trout, and deer and grouse are fairly abundant in certain localities. But the control of hunting and fishing is at present inadequate, governed as it is solely by the general game laws of the State. Development of the wild life of the Forest as an integral part of its value to the public calls for carefully planned and close co-operation between the State and the Federal Government, to the end that the woods and streams may again abound in their natural denizens.

The history of what has taken place in the forests of the White Mountains epitomizes in a broad way the history of the movement for forest preservation in the United States. Beginning with the first appearance of white men and the contact of civilization with the primeval wilderness, there was begun a struggle for subjugation of the forest in order to make room for settlement and community life.

At first the timber was an incumbrance, valueless because of its abundance, and blocking development. Fires were started to aid in clearing the land, and even when they swept far away and laid waste the mountain slopes, the destruction which was wrought was lightly regarded. With advance in economic development and the knitting together of the country through a network of railroads came a period in which exploitation of the virgin forest became vigorous, extensive, and of a progressively devastating character. Then a few far-sighted persons, at first regarded as impractical visionaries, began to urge the need for conservation of the forest resource for the sake of future timber supplies, for its influence upon water supplies, and for its value to the public in connection with recreation and scenic protection.

Gradually public sentiment groped to a realization of the fact that private ownership of mountainous forest lands is incompatible with the best public interest. With hesitancy and in the face of many misgivings as to the possibility of efficient management of public property through public officials, requiring, if it is to be successful, a high degree of intelligence, probity, and stability of policy, public ownership was undertaken. What the full measure of its results will be it is as yet too soon to say. That depends on the ability of the American people to maintain permanently, as a Government activity, administration of a public resource, of increasing money value, without allowing it to be infected by politics or placed in the hands of men lacking in competence and foresight. Nevertheless, it is scarcely possible that national ownership and management of forests like those in the White Mountains can ever fail to do better for the protection of the public welfare than private ownership and management, without public regulation. The strength of the situation lies in the fact that there now exists, and is certain to continue, an alert and powerful public sentiment which will not tolerate the handling of the resource in ways that are seen to threaten the impairment of its value and its beauty.

| <<< Previous | Next >>> |

sieur_de_monts/17/sec4.htm

Last Updated: 03-Dec-2009