|

ACADIA

The Sieur de Monts National Monument and its Historical Associations Sieur de Monts Publications XVII |

|

NOTCH OF THE WHITE MOUNTAINS, VISITED IN 1797.

TIMOTHY DWIGHT, PRESIDENT OF YALE COLLEGE.

On the morning of Tuesday, October 3, we pursued our journey. For some time before we set out, the wind blew with great strength from the northwest, in this region the ordinary harbinger of rain. The clouds, rapidly descending, embosomed the mountains almost to their base. The sky suddenly became dark; the clouds were tossed in wild and fantastical forms, and poured down the deep channels between the mountains with a torrent-like violence; and the whole heavens were overspread with a more gloomy and forbidding aspect than I had ever before seen. The scenery in the Notch of the White Mountains, commencing at the distance of five miles from Rosebrook's, was one of the principal objects which had allured us into this region. A gentleman from Lancaster, perfectly acquainted with this part of the country, had joined us at Rosebrook's, and proposed to be our companion and guide through this day's journey, and to give us all the necessary information concerning the objects of which we were in quest. If we stayed in Rosebrook's, we should lose his company and information. If we proceeded on our journey, as the weather was, we should lose our prospects; many of the objects being at such a season invisible, and others seen with the greatest disadvantage. Happily for us, our storm vanished as suddenly as it came on; the wind ceased almost in a moment; the clouds began to rise and separate; and we commenced our journey in the best spirits.

|

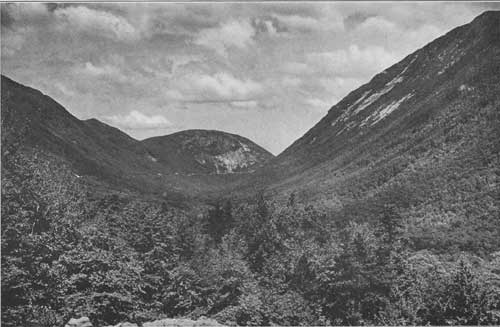

| THE HEART OF CRAWFORD NOTCH |

From Rosebrook's our road lay for about two miles along the Ammonoosuc, on an interval. We then began to ascend an easy slope, which is the base of these mountains. After proceeding along the slope two miles farther, we crossed a small brook, one of the head waters of the Ammonoosuc; and within the distance of a furlong we crossed another, which is the head water of the Saco. The latter stream, turning to the east, speedily enters a pond, about thirty rods in diameter, lying at a small distance on the northern side of the road; and thence, crossing the road again and winding along the margin of a meadow formed by a beaver dam, enters the Notch. The northeastern cluster of mountains begins to ascend from the pond. The diameter of the meadow is about a furlong. The beaver dam was erected just below the Notch, in a place happily selected for this purpose. The mountains were scarcely visible at all until we came upon them.

The weather had now become perfectly fine. The clouds, assuming a fleecy aspect, rose to a great height, and floated in a thin dispersion. The wind was a mere zephyr; and the sky exhibited the clear and beautiful blue of autumn.

|

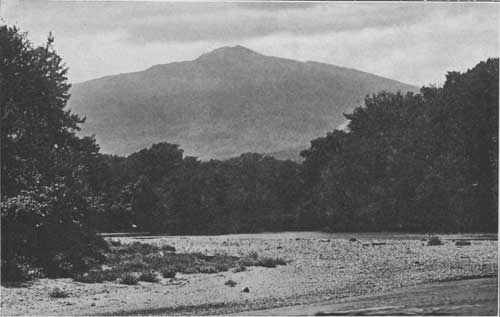

| DIXVILLE NOTCH |

The Notch of the White Mountains is a phrase appropriated to a very narrow defile extending two miles in length between two huge cliffs, apparently rent asunder by some vast convulsion of nature. This convulsion was, in my own view, unquestionably that of the Deluge. There are here, and throughout New England, no eminent proofs of volcanic violence; nor any strong exhibitions of the power of earthquakes. Nor has history recorded any earthquake or volcano in other countries of sufficient efficacy to produce the phenomena of this place. The objects rent asunder are too great, the ruin is too vast and too complete, to have been accomplished by these agents. The change appears to have been effectuated when the surface of the earth extensively subsided; when countries and continents assumed a new face and a general commotion of the elements produced the disruption of some mountains, and merged others beneath the common level of desolation. Nothing less than this will account for the sundering of a long range of great rocks, or rather of vast mountains; or for the existing evidences of the immense force by which the rupture was effected.

The entrance of the chasm is formed by two rocks, standing perpendicularly at the distance of twenty-two feet from each other: one about twenty feet in height, the other about twelve. Half of the space is occupied by the brook mentioned as the head stream of the Saco; the other half by the road. The stream is lost and invisible beneath a mass of fragments, partly blown out of the road and partly thrown down by some great convulsion.

|

| LOST RIVER |

When we entered the Notch, we were struck with the wild and solemn appearance of everything before us. The scale on which all the objects in view were formed was the scale of grandeur only. The rocks, rude and ragged in a manner rarely paralleled, were fashioned and piled on each other by a hand operating only in the boldest and most irregular manner. As we advanced, these appearances increased rapidly. Huge masses of granite, of every abrupt form and hoary with a moss which seemed the product of ages, recalling to the mind the "Saxum vetustum" of Virgil, speedily rose to a mountainous height. Before us the view closed almost instantaneously and presented nothing to the eye but an impassable barrier of mountains.

About half a mile from the entrance of the chasm we saw in full view the most beautiful cascade, perhaps, in the world. It issued from a mountain on the right, about eight hundred feet above the subjacent valley, and at the distance of about two miles from us. The stream ran over a series of rocks, almost perpendicular, with a course so little broken as to preserve the appearance of an uniform current, and yet so far disturbed as to be perfectly white. The sun shone with the clearest splendour from a station in the heavens the most advantageous to our prospect; and the cascade glittered down the vast steep, like a stream of burnished silver.

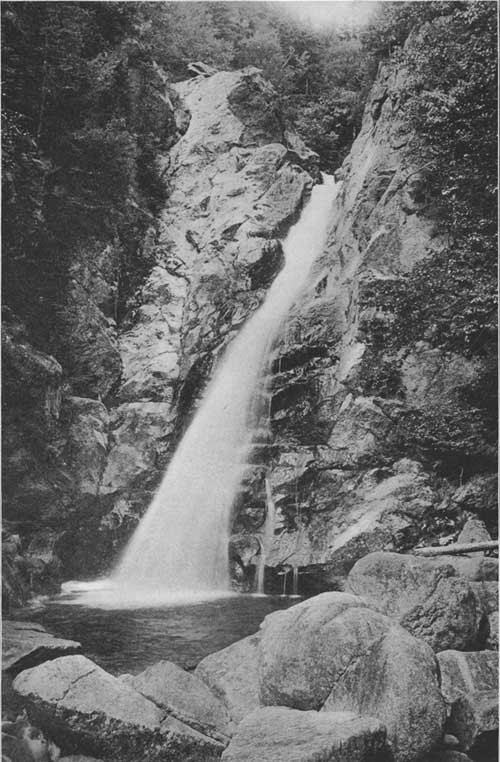

At the distance of three-quarters of a mile from the entrance, we passed a brook, known in this region by the name of the Flume from the strong resemblance to that object exhibited by the channel which it has worn for a considerable length in a bed of rocks, the sides being perpendicular to the bottom. This elegant piece of water we determined to examine further, and, alighting from our horses, walked up the acclivity, perhaps a furlong. The stream fell from a height of 240 or 250 feet over three precipices: the second receding a small distance from the front of the first, and the third from that of the second. Down the first and second, it fell in a single current; and down the third in three, which united their streams at the bottom in a fine basin, formed by the hand of nature in the rocks immediately beneath us. It is impossible for a brook of this size to be modelled into more diversified or more delightful forms; or for a cascade to descend over precipices more happily fitted to finish its beauty. The cliffs, together with a level at their foot, furnished a considerable opening, surrounded by the forest. The sunbeams, penetrating through the trees, painted here a great variety of fine images of light, and edged an equally numerous and diversified collection of shadows; both dancing on the waters, and alternately silvering and obscuring their course. Purer water was never seen. Exclusively of its murmurs, the world around us was solemn and silent. Everything assumed the character of enchantment; and had I been educated in the Grecian mythology, I should scarcely have been surprised to find an assemblage of Dryads, Naiads, and Oreads sporting on the little plain below our feet. The purity of this water was discernible, not only by its limpid appearance, and its taste, but from several other circumstances. Its course is wholly over hard granite; and the rocks and the stones in its bed, and at its side, instead of being covered with adventitious substances, were washed perfectly clean; and by their neat appearance added not a little to the beauty of the scenery.

|

| GLEN ELLIS CASCADE |

From this spot the mountains speedily began to open with increased majesty; and in several instances rose to a perpendicular height, a little less than a mile. The bosom of both ranges was overspread, in all the inferior regions, by a mixture of evergreens with trees whose leaves are deciduous. The annual foliage had been already changed by the frost. Of the effects of this change it is, perhaps, impossible for an in habitant of Great Britain, as I have been assured by several foreigners, to form an adequate conception, without visiting an American forest. When I was a youth, I remarked that Thomson had entirely omitted, in his Seasons, this fine part of autumnal imagery. Upon inquiring of an English gentleman the probable cause of the omission, he informed me, that no such scenery existed in Great Britain. In this country it is often among the most splendid beauties of nature. All the leaves of trees, which are not evergreens, are by the first severe frost changed from their verdure towards the perfection of that colour which they are capable of ultimately assuming, through yellow, orange, and red, to a pretty deep brown. As the frost affects different trees, and the different leaves of the same tree, in very different degrees, a vast multitude of tinctures are commonly found on those of a single tree, and always on those of a grove or forest. These colours, also, in all their varieties are generally full; and in many instances are among the most exquisite which are found in the regions of nature. Different sorts of trees are susceptible of different degrees of this beauty. Among them the maple is pre-eminently distinguished by the prodigious varieties, the finished beauty, and the intense lustre of its hues; varying through all the dyes, between a rich green and the most perfect crimson, or, more definitely, the red of the prismatic image.

|

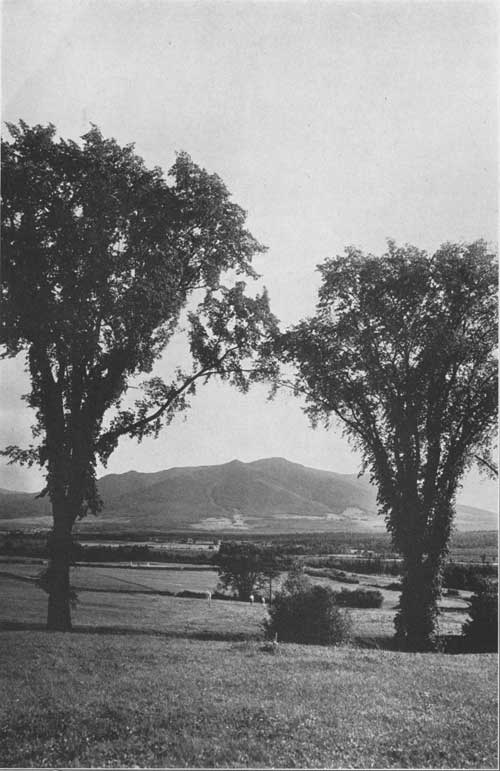

| CHERRY MOUNTAIN |

I have remarked that the annual foliage on these mountains had been already changed by the frost. Of course, the darkness of the evergreens was finely illumined by the brilliant yellow of the birch, the beech, and the cherry, and the more brilliant orange and crimson of the maple. The effect of this universal diffusion of gay and splendid light was to render the preponderating deep green more solemn. The dark was the gloom of evening, approximating to night. Over the whole, the azure of the sky cast a deep, misty blue, blending toward the summits every other hue, and predominating over all.

As the eye ascended these steeps, the light decayed, and gradually ceased. On the inferior summits rose crowns of conical firs and spruces. On the superior eminences, the trees, growing less and less, yielded to the chilling atmosphere, and marked the limit of forest vegetation. Above, the surface was covered with a mass of shrubs, terminating at a still higher elevation in a shroud of dark-coloured moss.

As we passed onward through this singular valley, occasional torrents, formed by the rains and dissolving snows at the close of winter, had left behind them, in many places, perpetual monuments of their progress, in perpendicular, narrow, and irregular paths, of immense length, where they had washed the precipices naked and white from the summit of the mountain to the base.

Wide and deep chasms, also, at times met the eye, both on the summits and the sides, and strongly impressed the imagination with the thought, that a hand, of immeasurable power, had rent asunder the solid rocks, and tumbled them into the subjacent valley. Over all, hoary cliffs, rising with proud supremacy, frowned awfully on the world below, and finished the landscape.

By our side the Saco was alternately visible and lost, and increased, almost at every step, by the junction of tributary streams. Its course was a perpetual cascade, and with its sprightly murmurs furnished the only contrast to the majestic scenery around us.

|

| <<< Previous | Next >>> |

sieur_de_monts/17/sec5.htm

Last Updated: 03-Dec-2009