|

Alaska Subsistence

A National Park Service Management History |

|

Chapter 3:

SUBSISTENCE IN ALASKA'S PARKS, 1910-1971

In December 1971, when Congress passed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, the National Park Service managed some 6.9 million acres of Alaska real estate. That acreage covered less than 2 percent of Alaska's land mass but it comprised more than 28 percent of all NPS-managed land. [1] By that date, the agency had gained experience managing five Alaska park units, all of which had been established between 1910 and 1925. Two of the five units were established in order to preserve exceptional examples of Native American values and architecture, while the other three park units considered Native American values slightly if at all. It is perhaps ironic to note that the two units established with Native American values in mind have been largely irrelevant to the subsistence issue, while the three parks which soft-pedaled Native values (at least in their original goals) have had, by necessity, a long record of dealing with Native American and other rural residents' values and concerns.

Alaska's first national park unit was Sitka National Monument, established by presidential proclamation in August 1910 to commemorate two items of Native American interest: a remarkable collection of totems and the site of an epic 1804 battle between local Tlingits and the Russian Navy. The battle had been a major turning point in Russian-Tlingit relations, and the eventual Russian victory allowed for the subsequent Russian settlement of Sitka. The totems, carved by Haida craftsmen, were of remarkable importance as well; they had been collected from various Southeastern villages, brought to the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis, and had been returned to Indian River Park after the festivities had concluded. The territory's second park unit, proclaimed in October 1916, was based on a similar theme. Old Kasaan National Monument was established to protect a recently-abandoned Haida village that contained a wide variety of artistry—dwellings, totems, house posts, and other domestic architecture.

Although both monuments were established in hopes of commemorating and preserving Native architecture and artistic values, only one succeeded in doing so. Sitka National Monument was successfully managed because it was located adjacent to an active small town, and because hundreds of tourists visited the site each year. But Old Kasaan National Monument, remote and located well away from the major steamship route, fell victim to an early fire, and both weather and neglect caused the remaining objects to deteriorate into insignificance. Sitka National Monument, now known as Sitka National Historical Park, has become an increasingly popular destination over the years. At Old Kasaan, however, the site became so degraded that in 1955, Congress (at the agency's urging) delisted the national monument. Both sites, because of their small size (and in Sitka's case, its urban location) have hosted few subsistence activities over the years, and as the following chapter notes, Congress did not consider subsistence activities at Sitka National Historical Park when it passed the Alaska Lands Act in 1980. The remainder of this chapter considers subsistence issues in the three large park units that were established prior to the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act: Mount McKinley National Park, Katmai National Monument, and Glacier Bay National Monument. [2]

A. Mount McKinley National Park

Mount McKinley National Park was established on February 26, 1917, when President Wilson signed the bill that Congress had passed just a week earlier. The park was the brainchild of Charles Sheldon, a wealthy hunter-naturalist from Vermont, who had first visited the area in 1906 and had been so captivated by the experience that he returned a year later, built a cabin along the Toklat River, and spent the winter there. Sheldon, though a visitor, lived a subsistence lifestyle, killing meat as necessary for sustenance. Though particularly interested in Dall sheep, he was highly intrigued by the area's caribou populations and, as historian William Brown notes, "birds, bears, moose, foxes, and the multitudes of small creatures [also] caught his attention." During his ten-month stay along the Toklat River he befriended several Kantishna miners and also met some market hunters, but so far as is known, he met few if any area Natives. [3]

Sheldon hatched the idea of a "Denali National Park"—based on a "heraldic display of wildlife posed against stupendous mountain scenery"—in a January 1908 journal entry. He did not immediately act on that idea, however. In August 1912, Congress passed an act that created an Alaska Railroad Commission; this was followed two years later by the Alaska Railroad Act, which paved the way for a government-backed railroad connecting the Gulf of Alaska with the Alaskan interior. Sheldon's concerns turned to alarm in April 1915, when President Wilson announced that the route to be followed, from Seward to Fairbanks, would go through the Nenana River Canyon, just east of the magnificent gamelands where he had lived and studied. [4] Worried that a railroad to the area would bring market hunters who would decimate the area's wildlife, Sheldon acted. Five months later, the influential Boone and Crockett Club, of which Sheldon was a longtime officer, formally endorsed a McKinley park proposal.

The park idea, once released to the public, soon captured the imagination of many members of the Eastern elite. But Alaskans, by contrast, were solidly against any bill that promised restrictions against hunting, either by setting bag limits, imposing unreasonably short hunting seasons, or instituting hunting closures over specified geographical areas. The McKinley park bill, realistically speaking, affected only one populated area. But that area—the Kantishna mining district—was well known to Alaska's delegate, James Wickersham (who had reconnoitered the area during his unsuccessful attempt to climb Mount McKinley in 1903), and the park proposal called for much of the Kantishna area to be surrounded by parkland. Wickersham was normally a conservationist; he was familiar with the park's backers and had attended several Boone and Crockett Club dinners over the years. [5] But in order to mollify his Kantishna-area constituents, he demanded that language be inserted into the park bill allowing local prospectors and miners to "take and kill game or birds therein as may be needed for their actual necessities when short of food; but in no case shall animals or birds be killed in said park for sale or removal therefrom, or wantonly." [6]

Given that language, the McKinley park bill passed the Senate unanimously in 1916 and—largely on the basis of a National Geographic Magazine article that appeared the following January—House action quickly followed. What emerged from the legislative battle was the nation's second largest national park. (Only Yellowstone was larger.) But from the point of view of subsistence users, the bill was particularly remarkable because Mount McKinley, unlike any other national park or monument, legalized subsistence hunting, at least under certain conditions. For more than a decade following the bill's passage, Mount McKinley was the only national park where local hunters legally enjoyed that privilege. [7]

It was clear from the Congressional hearings preceding the park's establishment that the protection of game populations from market hunters was the park's primary goal, and the NPS's management activities during the park's initial years were also clearly focused in that direction. But the agency's work was severely hampered by a lack of money. Although the park bill passed in early 1917, Congress did not vote to authorize operating funds until midway through the 1920-21 fiscal year, and the first NPS representative—Superintendent Henry P. "Harry" Karstens—did not arrive until June 1921. [8] During those intervening four years, the government railroad crept ever closer to the park. Some feared the worst about the effect of that access on game populations; one area visitor noted that "there has been great destruction of game and fur-bearing animals" in the park, while another feared that "the Mt. McKinley Park meat hunters appear to be slaughtering without stint." A Kantishna-based observer, however, flatly stated in a February 1920 letter [quoted verbatim] that these accounts are

all Pipedream Stories and not founded on facts ... to my knowledge the Scheep are holding their own, the Caribou have incrased enormously ... and the Moose are the only ones that are loosing out, on account of the Cow-killing especially by Indians in the late Winter. The Indian never goes any further then his Belly drives him, when Fish are plenty they never come in in here; but the last 3 years Salmon wher Scarce and the Indians had to get meat. If you want to save the Game, feed the Indians in Fishless Years. [9]

Once on the ground, Karstens—who had lived in the north country for more than twenty years and was locally known as the "Seventy Mile Kid"—was forced to work virtually from scratch. Operating on the most meager of budgets, he and his assistants had to to spend much of their time constructing park buildings—either near McKinley Park Station, at the present-day headquarters complex, along the park road, or at various perimeter locations. The cabins along the perimeter, and along the park road as well, supported extended ranger patrols against market hunters, and by the late 1920s depredations against the park's wildlife were becoming increasingly rare. Rangers recognized, however, that the original park boundaries had failed to include some of the most favorable sheep and caribou habitat. So to better protect the area's megafauna, the park's boundaries were expanded in 1922 and again in 1932. [10]

As noted in the previous chapter, the NPS, on a nationwide basis, had an inimical attitude toward hunters during this period; it was explicitly mentioned in both Secretary Lane's 1918 letter to Director Mather, and was mentioned again in Secretary Work's 1925 letter. [11] That attitude, combined with the clear recognition that much of the early park rangers' effort at Mount McKinley was being expended to combat the depredations of market hunters, did not bode well for the legitimate rights of area subsistence hunters.

Part of the problem, Karstens soon learned, was one of definition. The park's enabling act specifically allowed local residents to "take and kill game or birds therein as may be needed for their actual necessities when short of food," but what was the difference between gathering "actual necessities when short of food" (by prospectors and miners) and poaching (by market hunters and recreational sportsmen)? NPS officials in Washington, in 1921, sent Karstens a series of strongly-worded draft regulations, which empowered park staff to punish violators of the poaching ban with the confiscation of their game and their hunting outfits. They were less helpful, however, in formulating a system that would prevent market hunters and poachers from masquerading as prospectors and miners. Karstens, asked for his opinion on the matter, pushed for a regulation that would allow local miners to feed game meat to their dogs under hardship conditions, and he also pushed for a special exception for two local Indian groups, who often engaged in springtime hunting in the park because they had exhausted the dried and smoked fish supply laid out the previous summer. The final regulations did not specifically allow for either provision. They did, however, require that prospectors and miners keep tabs of the game that they killed, and on an informal basis, NPS officials let it be known that the local Indians' needs for food was a delicate issue, suggesting that enforcement actions against them be undertaken only under egregious circumstances. [12]

The obvious ambiguities regarding the hunting provision became a headache to Karstens almost as soon as he arrived at the park; conservationists railed about the wanton killing of park game, while those representing the mining constituency propounded opposing arguments. At times, such as when Interior Secretary Work prepared his 1923 report to the president, concern over wanton game killing (justified or not) rose to such heights that proposals were made to repeal the hunting provision. But his recommendation was not backed up by either Congressional action or by a sufficient park budget to hire a sufficient ranger force to terminate poaching and market hunting. (From 1922 to 1924, Karstens and an assistant ranger comprised the entire park staff.) And the difficulty in identifying deserving game users finally forced Karstens to urge a change in the regulation. As he noted in a January 1924 letter,

My recommendation would be to close the park to all hunting. As long as prospectors are allowed to kill game, just as surely will the object of this park be defeated. Any townie can take a pick and pan and go into the park and call himself a prospector. This is often the case. Compromises will not do, for compromises only leave loopholes for further abuse. [13]

Karstens's letter gave further evidence to those who hoped to repeal the hunting provision. Meanwhile, problems continued. A park ranger, for example, cited local resident Jack Donnelly for killing and transporting game from the park, but a local jury, in February 1924, failed to convict him "because of the reluctance of the people ... to convict anyone for illegal hunting." That same month, influential Outside outdoorsman William N. Beach was convicted of illegally killing a sheep in the park after openly boasting of the deed to a Washington NPS official. (He was fined $10 and court costs.) And as late as 1927, Chief Ranger Fritz Nyberg was well aware that there were at least 25 trappers operating along the park's boundaries, "practically all" of whom "have dogs that are fed from caribou and sheep." But neither funds nor cabins were sufficient to patrol the park's boundary and prevent depredations. [14]

Those who, in light of today's attitudes, were genuine park-area subsistence users were treated unevenly when discovered by NPS rangers. So far as the records indicate, no local non-Natives were cited for slaughtering game meat in the park, primarily because rangers, on their patrols, discovered that virtually every person found with a freshly-killed animal claimed to be a prospector or miner. Once, however, Natives were arrested under similar circumstances. On November 15, 1924, a park ranger caught two Nenana men, Enoch John and Titus Bettis, with four freshly-killed sheep within the park boundary. The two men freely admitted their guilt and were "pretty well scared and repentant" to park officials. But they committed their offense because of ignorance: "some of the white men around Healy" had advised them that these hunting grounds were outside of the park, and park officials were also quick to recognize that John's health was poor, his eyesight was failing, and his family's "living conditions were bad and they had very little food in the house." Superintendent Karstens, asked to resolve the matter, simply asked the two Natives to sign an affidavit acknowledging their act, and he also admonished them "to use their good influence with the tribe and tell them they must not hunt in the park." Acting Director Arno Cammerer, upon receiving Karstens's report, congratulated him on the "excellent manner in which you handled these cases" and that "publishing your disposition of these cases in Healy was good business and will be helpful." [15]

Karstens's January 1924 letter, as it turned out, proved critical in the battle over the fate of the park's controversial hunting provision. The letter, combined with other reports that documented wholesale killing of park wildlife, jolted park protectors into convening the following month and organizing an anti-hunting legislative strategy. That strategy finally bore fruit on May 21, 1928, when Congress repealed the hunting provision. For more than fifty years after the passage of that act, hunting of all types was prohibited in Mount McKinley National Park. [16]

|

|

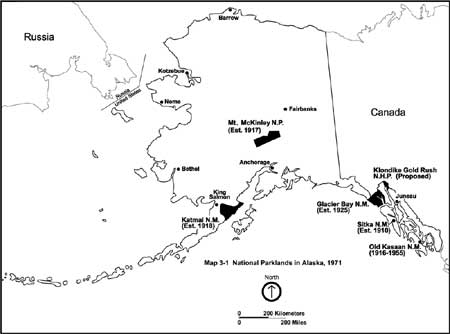

Map 3-1. National Parklands in Alaska,

1971.

(click on image for an

enlargement in a new window)

|

B. Katmai National Monument

The remote Katmai region of southwestern Alaska, which was little known at the time even to most other Alaskans, became world famous in early June 1912. An Aleutian Range volcano, which was then thought to be Mount Katmai, erupted with such force that it deposited several cubic miles of volcanic ash on the surrounding countryside. Scientists soon recognized that the explosion was one of the largest to be recorded in historic times. In its aftermath, scientists from both the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Geographic Society flocked to the area. A botanist from Ohio State University, Robert Fiske Griggs, headed NGS expeditions to the area during the summers of 1915, 1916, and 1917, and the publicity that followed his discovery of the "Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes" (the "smokes" were fumaroles, or jets of volcanic steam, that emanated from the valley floor west of the eruption site) captivated Interior Department officials to such an extent that President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed the area a national monument in September 1918. [17]

In 1930, Griggs returned to the area—his first trip back since 1919—in order to study plant succession in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. Griggs entered the monument by ascending the Naknek River and by crossing the length of Naknek Lake; and despite the scope of his research, he was not oblivious to the area's remarkable fish and wildlife populations. As Griggs may or may not have known, his visit to the area took place in the midst of a long-running controversy over the protection of the Alaskan brown bear, and game-protection advocates beginning in 1928 had proposed either Admiralty Island or Chichagof Island (both in southeastern Alaska) as national monuments. NPS officials, at the time, were totally incapable of managing their existing national monuments (the agency's 1930 budget for all of the country's national monuments was only $46,000), so they had little interest in acquiring a new management area. But they did want to placate the wildlife conservationists, so after Griggs returned from his sojourn that year, Assistant Interior Secretary Ernest Walker Sawyer quizzed him about Katmai's brown bear populations. Sawyer, by his letter, sincerely hoped that Griggs would provide him ammunition that would justify the expansion of Katmai's boundaries so as to include areas of prime brown bear habitat. And to a large extent, Griggs' letter, dated November 22, 1930, did not disappoint; it noted that "the Katmai National Monument is the only place in the world where the great Alaskan brown bear can be preserved for posterity." He outlined a large area of brown bear habitat north, northwest, and northeast of the existing monument, one which, with small alterations, was accepted by Interior Department officials and signed by President Herbert Hoover five months later. Hoover's proclamation, signed April 24, 1931, more than doubled the monument's size; for more than 45 years thereafter, Katmai had more land area than any other NPS unit. [18]

Neither Wilson's nor Hoover's proclamations mentioned any human occupation of the area. [19] What may not have been widely known, however, was that former Native villages were included in both the original monument and area included in the 1931 expansion. These villages, along with several other longtime area habitation sites, both west of the Aleutian Range and along the Pacific littoral, had been evacuated as a result of the June 1912 eruption. The residents, fearful for their lives, had all moved voluntarily—the coastal inhabitants to Perryville, south of Chignik, and the interior villagers to New Savonoski, near Naknek—but before long, many of these residents yearned for their former homelands. New Savonoski residents, for example, made several attempts to resettle Old Savonoski, their former village, only to quickly recognize the impossibility of doing so because of the suffocating ash layer. [20] NPS officials, who had not yet set foot in the monument, were only vaguely aware of the former villages and had no inkling of any attempted resettlement efforts; had they been apprised of them, they would probably have resisted the Natives' efforts, assuming that the agency's conduct toward Katmai's Natives was similar to the way it had interacted with Natives elsewhere in the country (see Chapter 2).

Because of the area's remoteness—the Russian-era saying "God's in his heaven and the czar is far away" was still applicable here—area residents, both Native and non-Native, continued to use the monument for years after the monument's establishment. Because most of the area within the original (1918) monument was largely overlain by a foot or more of volcanic ash, few alternative uses were available for that land. But between 1918 and 1931, a number of Naknek-area residents began to filter into the area that Hoover would eventually include in the expanded monument. Trappers—some Native, others non-Native—were the most visible users; at least five lived legally in the monument each winter during the years that preceded Hoover's 1931 proclamation. Remote as the area was, the proclamation had no effect on area lifeways, and it was not until 1936 that an Alaska Game Commission officer visited the area and informed NPS officials of area trapping activity. Two years later a General Land Office investigator, A. C. Kinsley, spoke to most of the trappers and determined the legitimacy of their claims. (Those who had settled prior to 1931 were entitled to a claim to their trapping cabins but were not allowed to trap; those who came after 1931 could neither settle nor trap. To trappers, the distinction meant little.) Most moved out soon afterward, but a few had to be forcibly evicted. The onset of World War II diverted federal authorities to more critical wartime pursuits, and by the late 1940s it was discovered that a few trappers had returned to the monument. Those, however, were quickly routed, and by 1950 (when active, staffed management of the monument began) the problem had vanished. [21]

Reindeer herders, a primarily Native occupation that had been active since the 1890s, constituted a second group that moved into the monument during this period. According to Mount McKinley Superintendent Frank Been, who visited the park for several weeks in 1940, a herd of 10,000 reindeer had been brought "to the vicinity of the Naknek River ... sometime within the past 10 years," and that a portion of that herd "could graze into the north west corner of the park"—that is, in the area west of Lake Coville and north of Naknek Lake. At least one reindeer station was established in the monument at this time; it was located on Northwest Arm, near the northwestern end of Naknek Lake. This group left of its own accord prior to any intervention by NPS or other government officials. [22]

During the 1920s and 1930s, a number of local Native residents made annual hunting pilgrimages from either New Savonoski or South Naknek to the Savonoski River valley. (This valley was primarily outside the monument during the 1920s but was within its boundaries after April 1931.) Throughout this period these expeditions were scarcely noticed by the authorities, but when permission was asked to continue the practice, the NPS issued a denial and in 1939 the hunts came to a halt. [23]

Area Natives also carried on subsistence fishing activities in the monument. Louis Corbley, the Mount McKinley ranger who flew over the monument in 1937, landed at both Lake Brooks and "Old Village" (Old Savonoski, which had been abandoned since 1912), and in early September 1940, Superintendent Frank Been visited both Savonoski village and the two-cabin "fishing village" at the mouth of Brooks River. At the latter site, Been observed Native fishing activities—gill netting and fish drying on racks—and he also spoke at length with "One-Arm Nick" Melgenak, the "Native chief at New Savonoski." (As later testimony made clear, Melgenak and his family had made an annual trek to the site since 1924 if not before.) Been, who was accompanied by Fred Lucas, the Naknek-based U.S. Bureau of Fisheries agent, learned that the fish were "dried for dog food and for the Indian, who uses the fish for food, especially when money for white man's food runs low." He also learned that "the law permits taking salmon that are to be used for dog food, or food for the one who catches them. The salmon may be caught at any time and any place if the catch is to be used for dog food even though the product is for sales as dog food." Lucas estimated that 150,000 salmon spawned in either Brooks Lake or Brooks River, and although Natives harvested fewer than 10,000 of them, he "deplored the take of these fertile salmon because they were caught before they had deposited their eggs." [24]

So far as is known, the Melgenak family and other area Natives continued to visit the Brooks River mouth to harvest salmon each year during the 1940s. But in 1950, Northern Consolidated Airlines established a sport fishing camp nearby. Soon afterward, area Natives began to delay their arrival at the site until after the camp had closed for the season. Testimony collected during the 1980s consistently indicates that Natives arrived each year during the 1950s, but beginning about 1960 their visits became less frequent. [25] (They may also have harvested fish at other monument locations, but the NPS's presence at the monument during this period was so limited that the two groups rarely encountered one another away from Brooks Camp.) It was not until 1969 that the monument had become an independently-managed entity; by that time, Native fishing trips into the monument had all but ceased. [26]

C. Glacier Bay National Monument

Glacier Bay National Monument, in southeastern Alaska, has witnessed a more long-standing, contentious controversy over subsistence rights than any other Alaska park unit. The Tlingit and Haida peoples who traditionally populated southeastern Alaska were the first to be impacted by commercial fishing and other U.S.-based economic development activities; perhaps for that reason, it is not surprising that these Native groups were also the first to organize themselves, economically and politically. By the time Glacier Bay National Monument was proclaimed by President Calvin Coolidge, in February 1925, southeastern Natives had been living and interacting with U.S.-based migrants for more than fifty years, and they had been interacting with European-based peoples for well over a century. This long exposure, combined with the complex, powerful culture that southeastern Natives had enjoyed prior to European contact, suggests—at least in hindsight—that neither the National Park Service nor any other governmental agency would be able to unduly restrict the Natives' lifestyle without vociferous protest.

As Ted Catton's park administrative history indicates, the 1925 monument proclamation was the direct result of a campaign orchestrated by the Ecological Society of America, and more specifically by ecologist William S. Cooper and botanist Robert F. Griggs. When these two men first floated the monument idea, they were unaware of any Native issues related to land rights or ownership; citing the oft-used "worthless lands argument," [27] they assured the skeptical that the establishment of a monument would not impair economic growth because the area was economically useless. Before long, mining interests and homesteaders—both of which were locally active—came forth to denounce the proposal, and on the basis of utilitarian concerns (which included a few small Native allotments near the bay's mouth), the proposed area was substantially reduced. Coolidge's proclamation, signed February 26, 1925, made no mention of any Native connection to the area; the only cited evidence of a cultural context was that the monument had a "historic interest, having been visited by explorers and scientists since the early voyages of Vancouver in 1794, who have left valuable records of such visits and explorations." No attempt was made to extinguish any of the Native allotments prior to the issuance of Coolidge's proclamation. [28]

Because the new park unit remained unstaffed for years after its establishment, the agency had no way of knowing if area Natives (or non-Natives, for that matter) used the newly-withdrawn area for subsistence activities. But from the monument's inception, the agency intended to keep such uses away from the monument. Using a paradoxical argument that must have confounded local residents, the NPS prohibited the use of "firearms, traps, seines, and nets" in the monument without a custodian's permission, but the agency assigned no monument custodian from whom permission could be sought. Despite that prohibition, a number of Tlingits residing in Hoonah asked a Bureau of Indian Affairs official about hunting and carrying firearms in the monument; and a few months later, more than 150 Hoonah residents petitioned Alaska delegate Tony Dimond to allow hair seal hunting in the monument. These two actions took place in the spring and summer of 1937, some two years before the monument's boundaries were expanded to include all of Glacier Bay's waters. [29] Notably, however, neither action was forwarded to NPS or other Interior Department officials, and the lack of such action prevented Native use patterns from being taken into account during the period in which the monument expansion was being proposed.

In April 1939, President Roosevelt more than doubled the size of Glacier Bay National Monument, and within a few months administration officials became aware of how much Hoonah-area Tlingits used the newly-acquired monument lands. (The NPS had been told that "various officials or families among the Indians" claimed small tracts of newly-proclaimed monument land, but the agency felt that they were primarily of individual rather than tribal interest.) The BIA, which was not consulted prior to Roosevelt's action, loudly protested the monument expansion and defended the Hoonahs' continued use of Glacier Bay resources. The NPS responded by dispatching Mount McKinley Superintendent Frank Been to Hoonah that August, and in October 1939 the two agencies met and agreed to allow the Natives "normal use" of the monument's wildlife. This allowance included hunting (of both terrestrial and marine animals), trapping, and gull egg collecting. [30] In the eyes of NPS officials, however, this agreement was of an interim nature; as agency director Arno Cammerer noted in a December 1939 letter to Frank Been, "It is our intention to permit the Indians to take hair seals and to collect gull eggs and berries as they have done in the past, until a definite wildlife policy can be determined." [31]

Although they continued to honor the October 1939 agreement, NPS officials made no secret that they were uncomfortable with some of its ramifications; namely, it undermined their agency's authority, and it gave Native residents (who were allowed to hunt, trap, and gather in the monument) rights and privileges that were not extended to non-Native residents. For those reasons, the agency began looking for ways to rescind the agreement as early as 1940. Owing to the slashed budgets that World War II brought, however, nothing was done for the time being. But in 1944 the NPS arranged for the Fish and Wildlife Service to begin patrolling monument waters. (They did so because the fisheries agency, unlike the NPS, was financially and logistically able to enforce federal regulations there.) Hoonah residents were soon warned to cease trapping and seal hunting in Glacier Bay, and a year later, an F&WS warden arrested "three or four" Natives for hunting and trapping in the monument.

During this same period, the BIA was undertaking a nationwide investigation of Native land claims, and as part of that effort the Interior Department delegated a study of the Tlingits' rights in southeastern Alaska to attorney Theodore H. Haas and anthropologist Walter R. Goldschmidt. Of particular interest to the NPS, the two men attempted to clarify areas in the monument where Tlingits could claim possessory rights. Their report, released in the fall of 1946, concluded that the Tlingits' claims extended over large parts of Glacier Bay, Dundas Bay, and Excursion Inlet, all of which were included in the monument. The publication of that report brought BIA and NPS officials together again to work out an updated agreement. That meeting took place in December 1946, during a time of economic duress on the Hoonahs' part. The agreement worked out that day gave the Hoonahs the right—for four years only—to hunt hair seals, carry firearms, and hunt berries in the monument. [32]

For years after that agreement was forged, the Hoonahs walked a tightrope between their moral claim to the area, based on historical use and cultural ties, and the agency's longtime prohibitions against hunting. The NPS's regional director, for example, laid the groundwork to prevent the pact's renewal as early as 1947; biologist Lowell Sumner, after a ten-day visit that June, wrote a report questioning the legitimacy of the Hoonahs' seal hunting practices. (Specifically, Sumner noted the Hoonahs' recent increase in the seal harvest and the overtly commercial nature of that harvest; "the natives today have forsaken their ancestral way of life," he intoned. Based on that perception, he decried the apparent decline in the bay's seal population in light of the Natives' new hunting practices. He also urged the prohibition of seal hunting in various portions of the bay that had been glaciated in 1890. [33]) A visit to Hoonah in 1948 by Assistant Interior Secretary William Warne tipped the scales back in favor of the Natives, but the NPS, in the spring of 1950, countered by assigning a seasonal ranger, Duane Jacobs, to Glacier Bay. (The agency had been trying to establish a presence at the monument for several years, but other budgetary priorities had intervened.) Jacobs's marching orders were to "visit the area this summer, view the situation, and bring forth a factual study report as to the protection needs of the area." [34] In his concluding report that fall, Jacobs noted that "widespread evidence of poaching [of various animal species] was found," and that "the greater part of this poaching can properly be charged against the native population ... which centers in and around Hoonah...." He was careful to note that that not all of the Indians were violators and that not all of the Hoonahs' game violations were occurring in Glacier Bay, and he further noted that the existing state of affairs stemmed largely from a lack of previous enforcement efforts. To reduce the poaching problem, Jacobs urged the establishment of "a small force of rangers, well equipped and extremely mobile," and he "strongly recommended that the agreement allowing natives to hunt seals in monument waters be cancelled." Despite those recommendations, however, the monument's ranger force remained small throughout the 1950s. And regarding DOI's four-year seal-hunting agreement, the December 1950 deadline came and went without incident, and the 1946 agreement lapsed. [35]

During the next few years, the seal hunting issue was not a high NPS priority; few overt conflicts took place between the Hoonahs and agency rangers, which led the agency to assume that Native use of the bay was minimal and fading. When the issue arose again at a meeting in early 1954, all parties—the NPS, F&WS, BIA and the Hoonahs—all agreed that the "continued use" of Glacier Bay resources by Hoonah Natives was a "fair and logical solution to the problem." The various officials agreed in principle to renew the 1946 agreement, with an added proviso that local seal hunters be required to obtain permits. That agreement was renewed, largely without changes, in 1956, 1958, 1960, and 1962. [36]

In 1963, the context of Native seal hunting in the monument began to dramatically change. These seals had long been hunted in many Alaskan coastal areas, by both Natives and non-Natives, and because the animals' diet consisted at least partially of salmon, the territory had awarded a bounty to seal hunters ever since 1927. The bounty, however, was seldom sufficient to warrant harvesting for that reason alone, and seal harvesting remained at a fairly low level. But beginning in the fall of 1962, the overharvesting of seals in the North Atlantic and Arctic oceans—the areas that had traditionally supplied the commercial seal market—resulted in a new wave of interest in Alaskan harbor seal (hair seal) pelts, and the increasing value of seal pelts caused many to significantly augment their harbor seal harvesting activities. From 1963 to 1966, a record number of seals were harvested throughout Alaska, by both Natives and non-Natives. After the mid-1960s, harvests abated somewhat, but widespread harvesting continued in Alaska until 1972, when the Congressional passage of the Marine Mammal Protection Act prohibited non-Natives from taking seals, whales, polar bears, sea otters, and other marine mammals. [37]

It was within the context of the newly "discovered" harbor seal market that two Glacier Bay rangers, in March 1964, encountered a Hoonah encampment on Garforth Island, a small island in the bay just west of Mount Wright. The abandoned camp, which had been used by two seal hunters the previous summer, bore unmistakable evidence that a large herd of seals—some 243, by the rangers' count—had been harvested. The ranger, appalled by the sight of so many rotting corpses, was well aware that the practice was legal; even so, he declared that "this type of shooting has no place in a National Monument." Soon afterward, he learned that another hunter had recently taken 300 seals from the bay. Guessing that the bay's total seal population was 800 to 1,000 strong, he rued that "there are no bag limits, no closed season, and no closed area to protect this population ... Under present agreement this entire herd could be wiped out if the natives so desire." [38]

The increased seal take caused NPS officials—none of whom had been on staff when the previous (1939, 1946, or 1954) agreements had been signed—to reassess the legitimacy of seal hunting in Glacier Bay. Those who dictated park policy during the mid-1960s took a hard line against seal hunting, at least in their public statements; they asserted that the earlier agreements had been forged to help the Hoonahs through the critical period following World War II, and the monument's latest master plan (completed in 1957) had stated that Native seal hunting would be "reduced and eliminated within a reasonable period of time." NPS officials, however, fully recognized that many Hoonahs were small-scale subsistence users. They were also aware that the only local residents who were making a significant impact on the monument's seal populations were a few large-scale seal hunters, who openly declared their interest in harvesting solely for the monetary rewards brought by hides and bounty. Faced with the impossibility of sanctioning the activities of one group while prohibiting those of another, and charged by Congress with protecting the park "and the wild life therein" (as noted in the NPS's 1916 Organic Act), agency officials had little choice but to push for a termination of the seal-hunting agreement that had been in place, in one form or another, since 1939. Given the agency's quandary, it was perhaps beneficial to all of the involved parties that interest in the subject declined during the waning years of the 1960s. In part, this state of affairs was attributable to a decline in the number of seal hunting permits, and it was also because NPS officials in Washington told park staff to let the issue subside. [39]

Local Natives, despite the lack of a currently-functioning agreement, continued to hunt seals in the monument. But the vexing issue was by no means resolved, and the uncertainty surrounding it would hang over the heads of both seal hunters and park staff until well after the December 1971 passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. How the issue was handled during the 1970s is discussed in Chapter 4; more recent activities surrounding this issue are discussed in chapters 6 and 8.

D. The Alaska Native Cultural Center Proposal

The National Park Service had no Alaska presence outside of the various parks and monuments throughout the territorial period and for the first several years of statehood. But in November 1964, newly-appointed NPS Director George Hartzog appointed a special task force to prepare an analysis of "the best remaining possibilities for the service in Alaska," and two months later, the group produced Operation Great Land, a bold blueprint of potential agency activities. Among its many recommendations, the report identified thirty-nine Alaska zones or sites that contained outstanding recreational, natural, or historical values, and it also called for the establishment of an Alaska-based office. In response, the agency established the Alaska Field Office, located in Anchorage. The office, opened in April 1965, was minimally staffed; it seldom consisted of more than a biologist, a planner, and a secretary. The staff worked under the direction of the Mount McKinley National Park Superintendent. [40]

In October 1967, the potential for an enhanced level of agency activity arose when NPS Director Hartzog, along with Assistant Director Theodor Swem, were invited to meet with Governor Walter Hickel in Juneau. At this meeting, which had been arranged by Federal Field Committee for Development Planning in Alaska chairman Joseph Fitzgerald, the two NPS officials floated various park proposals. [41]

In addition, Hickel—at the behest of Congresswoman Julia Butler Hansen (D-Wash.), who had just returned from an Alaskan vacation—was presented with the "Native Cultural Centers" idea. This concept envisioned that the National Park Service would assist in

the development of places where Alaska visitors can see examples of native culture in appropriate settings and, through meeting and talking with natives, can gain greater understanding and appreciation for those who have inhabited this strange, hostile land for centuries. [42]

The beneficiaries of this idea, however, would by no means be limited to tourists. Natives, and Native communities, were recognized as being in the midst of a rapid transformation between traditional and modern ways, and traditional occupations, housing styles, and other cultural elements were being cast aside as Natives—particularly in western and northern Alaska—attempted to cope with those changes. The NPS hoped that the establishment of various cultural centers might serve as cultural touchstones, where Natives across the state would learn about their own traditional culture. [43]

The NPS's San Francisco Service Center responded to the Juneau meeting by designating a three-person team to travel to selected sites in "native Alaska." That four-week trip, taken in May and June 1968, was intended to investigate not only the cultural center idea but to "examine the present state of preservation among the native villages and recommend courses of historic preservation which could result in greater understanding and appreciation of the native cultures by visitors and the native Alaskans themselves." The trio visited several of Alaska's largest population centers, including Barrow, Kotzebue, Nome, Juneau, Wrangell, Ketchikan, Fairbanks, and Anchorage. The team also visited six Eskimo (Inupiat) villages, two Siberian Yup'ik villages, and two Athapaskan villages. It made no attempt to visit any Central Yup'ik villages, and it opted not to focus on Aleut culture because the Aleuts "retain very few of the old cultural traditions." [44]

The team's report, written shortly after its return to San Francisco, was quick to point out that "It is not a foregone conclusion that the National Park Service is the most logical agency to spearhead this study, or to 'carry the ball' on the cultural center concept. But a first step must be taken by someone if the goal of cultural preservation is to be achieved." Having said that, the team recommended the establishment of three centers, all located "near the larger cities and readily accessible to the tourists": an Eskimo Native Culture Center in Nome, an Athapascan Native Culture Center in Fairbanks, and Southeast Coastal Indian Culture Center in Ketchikan. Regarding preservation, the report recommended that "some of the most representative native villages" be designated National Historic Landmarks "to give them proper recognition and encourage local preservation efforts." Finally, it recommended that Congress designate a commission "to investigate establishment of cultural centers and their effect on the state and the nation." The commission would be composed of representatives from a variety of federal and state agencies, native groups, and tourism organizations. [45]

It is difficult to ascertain the immediate reaction to the issuance of this report, but it had little practical effect. During the next few years, no one—neither the NPS, Native groups, nor tourism organizations—stepped up to adopt any of the report's recommendations. The report, however, was nevertheless valuable because it signaled the NPS's interest in Native preservation issues, both in the identification and analysis of structural preservation (which had been the NPS's traditional role, as evidenced by Sitka and Old Kasaan National Monuments) but in broader cultural preservation issues as well. The agency stepped gingerly into the latter theme and made it clearly known that resolving such issues was best handled by Native groups themselves, but the agency's concern over the loss of traditional cultural elements motivated the agency to both present the issue to a broader public and suggest possible solutions.

Notes — Chapter 3

1 Webster's Geographical Dictionary (Springfield, Mass., G. & C. Merriam Co., 1967), 1188-91; John Ise, The National Park Service; A Critical History (New York, Arno Press, 1979), 2.

2 Congress authorized Klondike Gold Rush NHP, in the Skagway area, in June 1976. Perhaps because of its small size (about 13,000 acres), the park was judged not to have significant subsistence values.

3 William E. Brown, A History of the Denali-Mount McKinley Region, Alaska (Santa Fe, NPS, 1991), 75-77, 83. Native use of the area has been documented in Terry L. Haynes, David B. Anderson, and William E. Simeone, Denali National Park and Preserve: Ethnographic Overview and Assessment (Fairbanks, NPS/ADF&G), 2001.

4 Joan M. Antonson and William S. Hanable, Alaska's Heritage, Alaska Historical Commission Studies in History No. 133 (Anchorage, Alaska Historical Society, 1985), 369-70.

5 Brown, A History of the Denali-Mount McKinley Region, 32-34, 87-88, 91.

7 Ibid., 92-93; Lary M. Dilsaver, ed., America's National Park System; the Critical Documents (Lanham, Md.; Rowman and Littlefield, 1994), 63-64.

8 Brown, A History of the Denali-Mount McKinley Region, 95, 136, 138, 146.

9 Fred Hauselmann (Little Moose Creek, Kantishna Mining District; mailed from Nenana) to Secretary of the Interior, February 7, 1920, in "Wild Animals, Parts 1 and 2" file, Box 112, MOMC, Central Classified Files, Entry 6, RG 79, NARA DC.

10 Brown, A History of the Denali-Mount McKinley Region, 136, 138-45, 185-89.

11 As mentioned in Chapter 2, Secretary Work's letter stated that Mount McKinley (due to specific language in its enabling act) was an exception to the general prohibition against.

12 Brown, A History of the Denali-Mount McKinley Region, 138, 145-47.

15 Documents also refer to one of the hunters as Enos John and Enock John; the above spelling is as it appeared on the affidavit. Harry Karstens to NPS Director, November 18, 1924; Cammerer to Karstens, December 23, 1924; both in "Wild Animals, part 1 & 2" file, Box 112, Central Classified Files, Mount McKinley, Entry 6, RG 79, NARA DC.

16 Brown, A History of the Denali-Mount McKinley Region, 148-49.

17 Frank Norris, Isolated Paradise; An Administrative History of the Katmai and Aniakchak National Park Units (Anchorage, NPS, 1996), 17, 22-34.

19 The 1931 proclamation noted that the land under consideration contained "features of historical and scientific interest," but this phrase was probably included to complement language originally propounded in the 1906 Antiquities Act, which was Hoover's authority for the expanding the monument.

20 John A. Hussey, Embattled Katmai; A History of Katmai National Monument (San Francisco, NPS, August 1971), 329-69; Janet Clemens and Frank Norris, Building in an Ashen Land; Katmai National Park and Preserve Historic Resource Study (Anchorage, NPS, 1999), 30-32.

21 Clemens and Norris, Building in an Ashen Land, 114-18.

23 Hussey, Embattled Katmai, 369.

24 Frank T. Been, Field Notes of Katmai National Monument Inspection, November 12, 1940, pp. 9-11, 15, 24; Norris, Isolated Paradise, 214-15.

25 Norris, Isolated Paradise, 214-17, 332; Clemens and Norris, Building in an Ashen Land, 129-30. As former park employee Pat McClenahan has noted, at least one witness in the so-called Melgenak land case claimed that NPS officials during the 1950s pressured Natives to leave the Brooks Camp area. The mere presence of the concessions camp there also played a role. Natives certainly disliked the increasing scrutiny of sport fishermen, and they likewise resented the fact that their long-established fishing patterns had been upset in the interest of accommodating Outside sportsmen. In the summer of 1966, someone—from either the NPS or the concessioner—razed the last of the structures associated with the Natives' use of the area. McClenahan to author, May 14, 2002.

26 As Isolated Paradise notes on pp. 402-03, area Natives had long been harvesting late-spawning red salmon ("redfish") near the Naknek Lake outlet, but this area was not incorporated into the monument until January 1969. Park superintendents for decades afterward doubtless knew about this fishery, and they also had the power to close it down, but they did nothing to regulate it until the early 1990s.

27 Historian Alfred Runte ably developed the "worthless lands thesis" in National Parks; the American Experience (Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1979), 48-64.

28 Theodore Catton, Land Reborn; A History of Administration and Visitor Use in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve (Anchorage, NPS, 1995), 51-52, 56-58, 114.

29 Ibid., 102. The local Natives are now known as the Huna Tlingit.

32 Ibid., 119-24; Walter R. Goldschmidt and Theodore H. Haas, Possessory Rights of the Natives of Southeastern Alaska (Washington, DC, Bureau of Indian Affairs), 1946.

33 Lowell Sumner, Special Report on the Hunting Rights of the Hoonah Natives in Glacier Bay National Monument, (NPS, Region Four, August 1947), 1, 3, 7, in GLBA Archives.

34 O. A. Tomlinson to Supt. Yosemite, April 25, 1950, in GLBA File 201, RG 79, NARA San Bruno.

35 Duane Jacobs, Report of Special Assignment at Glacier Bay National Monument, 1950 Season, in GLBA File 207, RG 79, NARA San Bruno; Catton, Land Reborn, 125-30.

36 Catton, Land Reborn, 131-32, 192.

37 Linda Cook and Frank Norris, A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast; Kenai Fjords National Park Historic Resource Study (Anchorage, NPS, 1998), 136-40.

38 Catton, Land Reborn, 191-94.

39 Ibid., 197-99, 202, 206; Wayne Howell to author, December 11, 2001.

40 G. Frank Williss, "Do Things Right the First Time;" the National Park Service and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980 (Denver, NPS, September 1985), 34-43.

41 Frank Norris, Legacy of the Gold Rush; An Administrative History of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (Anchorage, NPS, 1996), 84. Hickel showed interest in just one of the proposals, a historical park in the Skagway area. The momentum generated by that meeting resulted, nine years later, in the Congressional passage of the bill that authorized Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park.

42 NPS, Alaska Cultural Complex, A Reconnaissance Report, June 1968, 2.

44 Team members included Merrill J. Mattes, team captain and planner; Reed Jarvis, historian; and Zorro Bradley, archeologist. The Inupiat villages included Point Hope, Noatak, Kivalina, Wainwright, Wales, and Shishmaref; the Siberian Yup'ik villages included Gambell and Savoonga; and the Athapaskan villages included Fort Yukon and Arctic Village. NPS, Alaska Cultural Complex, 1-6, 24.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

alaska_subsistence/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 14-Mar-2003