|

Alaska Subsistence

A National Park Service Management History |

|

Chapter 4:

THE ALASKA LANDS QUESTION, 1971-1980

A. Congress Passes a Native Claims Settlement Bill

As noted in Chapter 1, Alaska's Native peoples, by and large, had rejected the traditional reservation system that had predominated in other U.S. states. Lacking that land base, these groups, over the years, had pressed the U.S. Congress for a bill that would provide legal rights to their traditional use lands. The Federal government, however, never showed much inclination to respond to Natives' needs; the closest it had come to doing so had been in during the 1940s, when Interior Secretary Harold Ickes had implemented a series of "IRA reservations," so named because they were authorized by amendments to the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act. Those reservations, however, proved to be of limited value and most were of short duration; and as the decade of the 1960s dawned, the only lands specifically allotted to Alaska Natives were a smattering of 160-acre parcels (that had been granted by the 1906 Allotment Act) and such individual parcels as Natives had been able to acquire. [1] Except for the Metlakatla reservation near Ketchikan, Alaska Natives owned virtually no communal land. This state of affairs, to be sure, was not perceived as a critical problem during the first half of the twentieth century; as late as 1960, non-Natives had little continuing interest in the vast majority of Alaska's land base, and conflicts over ownership and resource use were small in scope and generated little heat in the public policy arena.

A series of events beginning in the mid-1960s brought increased pressure for a Native land claims bill. The first major event, necessitated by Natives' ire over state land selections, was Interior Secretary Stewart Udall's land freeze, which was carried out in stages beginning in 1966. The formation of the Alaska Federation of Natives during the winter of 1966-67 helped crystallize support for a land claims bill. But what really created momentum for a Native claims bill was the Prudhoe Bay oil strike, along with the concomitant recognition that the North Slope's "black gold" would be valueless if a way could not be built to carry the oil to Outside markets; and the Interior Department refused to allow the construction of a pipeline unless the Native claims issue was addressed. [2]

Because Natives claimed rights to lands throughout Alaska, the net effect of each of these actions was to increase pressure for Natives to consummate a lands settlement, and a major byproduct of that increasing pressure was that each proposal that purported to resolve the issue resulted in an increasing number of acres for Native ownership and use. One of the first Native claim proposals, for instance, was a 1963 Interior Department plan that would have granted 160-acre tracts to individuals for homes, fish camps, and hunting sites, along with "small acreages" for village growth. (As noted in Chapter 1, the Native Allotment Act, passed sixty years earlier, had already granted Natives the right to obtain 160-acre parcels if they could prove use and occupancy.) One subsequent proposal called for the creation of a 20-square-mile (i.e., 12,800-acre) reservation surrounding each Native village, while another, somewhat later proposal suggested a 50,000-acre grant to each village along with a small cash payment to village residents. [3]

Congress made its first attempt to solve the native land claims issue in June 1967 when Senator Ernest Gruening, at the request of the Interior Department, introduced S. 1964, which would have authorized a maximum of 50,000 acres in trust for each Native village. Native rights leaders were vociferously opposed to S. 1964—Emil Notti stated that it was "in no way fair to the Native people of Alaska." So just ten days later, both Gruening and Rep. Howard Pollock (D-Alaska) submitted bills (S. 2020 and H.R. 11164, respectively) on behalf of the Alaska Federation of Natives. These bills were intended to confer jurisdiction upon the Court of Claims regarding Alaska Natives' land claims. Later that year, Edward "Bob" Bartlett, Alaska's other U.S. Senator, submitted his own bill (S. 2690) pertaining to the land claims issue. All four bills were brief and none were extensively debated, although they did serve as a vehicle for further discussions. [4]

By January 1968, a land claims task force appointed by Governor Walter Hickel recommended that Native villages be granted a total of 40 million acres and that cash payments be provided which, under specified conditions, would total more than $100 million. Later that year, the Federal Field Committee for Development Planning in Alaska issued a report, entitled Alaska Natives and the Land, that recommended a land grant of from four to seven million acres plus a cash grant of $100 million and 10 percent of public lands mineral royalties; shortly afterward, the Interior Department countered with a proposal to provide 12.5 million acres and $500 million. [5] The Natives soon weighed in with their own proposal, which included 40 million acres and $500 million; in addition, it called for the creation of twelve regional Native corporations that would manage the land and money received in the settlement. But no one in a position of power advocated extensive Native land grants; Senator Henry Jackson (D-Wash.) stated that "The last thing that I think we want is tremendous land grants, resulting in large, idle enclaves of land," while another Senate Interior Committee member, Clinton Anderson (D-N.M.) asked, "If all the people who claimed aboriginal title were granted land, there would not be enough for the rest of us, would there?" As in 1967, none of the land-claims settlement bills submitted in either Congressional chamber received so much as a committee hearing. [6]

Up until this time, the various legislative proposals did not include land in southeastern Alaska. But as noted in Chapter 1, a January 1969 Court of Claims decision awarded the Tlingit and Haida plaintiffs money and land in a case that had first been filed back in 1935. Despite that award, however, the court had decreed that Indian title had not been extinguished to more than 2.6 million acres of land in Alaska's southeast. As a result, Natives in southeastern Alaska joined their colleagues elsewhere in the state to push for an equitable lands settlement.

Early in 1969, Congress began sorting through the various proposals, and the Senate Interior Committee attempted to work out an acceptable bill that fall. Bickering within the committee, and occasional leaks to the press of the Committee's negotiations, effectively prevented progress for several months. Then, in April 1970, a Federal judge halted all work on the proposed pipeline until the native claims issue could be worked out (see Chapter 1); as a result, various oil companies joined the chorus of those pushing for a viable Native claims bill. Within a week, the Senate Interior Committee reported a bill out, which called for $1 billion in compensation plus 40 million acres of land surrounding the villages. That bill, S. 1830, passed the Senate in July 1970, but the House did not act. The bill died with the adjournment that fall of the 91st Congress. [7]

Early in 1971, the prospects for a bill looked bleak. But in April, President Richard Nixon presented a special message to Congress that called for a 40 million-acre land entitlement and a $1 billion compensation package; that same month, Chairman Henry Jackson of the Senate Interior Committee submitted a revised bill (S. 35) that was co-sponsored by Alaska's two newly-minted senators, Mike Gravel and Ted Stevens. Attention then shifted to a House subcommittee, which reported out its version of a bill in early August, and on October 20 the entire House passed a land claims bill (H. 10367). In early November, the Senate overwhelmingly passed a bill that differed significantly from the House's version. The House-Senate conference committee sifted through these differences and reported out compromise legislation in early December. That compromise, which called for a $962.5 million cash payment, a 40 million-acre land conveyance, and numerous other provisions, was passed by both legislative bodies. President Nixon signed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) on December 18, 1971. [8]

|

| Alaska's two U.S. Senators during the 1970s were Mike Gravel (left) and Ted Stevens. ADN |

Alaska Natives were hopeful that that any land settlement bill that passed Congress would contain language that would provide not only land ownership but also legal protection for the Natives' continued use of the public lands. This provision was necessary because, as Alaska Natives and the Land had made clear, Alaska Natives needed far more land for their traditional uses than simple land grants could provide. To provide for this need, the earliest land-settlement bills—S. 1964, introduced in mid-June 1967—included the first tentative attempt to legislate protections for continued Native access and use. Section 3(e) of the brief bill stated, in part, that

The Secretary of the Interior may ... issue to natives exclusive or nonexclusive permits, for twenty-five years or less, to use for hunting, fishing, and trapping purposes any lands in Alaska that are owned by the United States without thereby acquiring any privilege other than those stated in the permits. Any patents or leases hereafter issued in such areas ... may contain a reservation to the United States of the right to issue such permits and to renew them for an additional term of not to exceed twenty-five years in the discretion of the Secretary. [9]

The other three bills submitted that year contained no such protection. By the following year, however, Secretary Udall's land freeze had been in effect for over a year, and optimism about the Prudhoe Bay oil strike was quickly spreading. Perhaps in response, all three of the land-settlement bills introduced in 1968 addressed the issue of "aboriginal use and occupancy." S. 2906, introduced on February 1, stated that "The Natives of Alaska may continue to use or occupy, for hunting, fishing, and trapping purposes, and for any other aboriginal use any lands that are owned by the United States." But H.R. 15049, introduced the same day by Rep. Howard Pollock, made no such sweeping provision; it stated only that the Interior Secretary could grant lands outside the state's various Native villages "if he finds that such additional grant is warranted by the economic needs of the native group or his determination that the native group has not received a reasonably fair and equitable portion of the lands settled upon all native groups and granted by this Act." A third bill (S. 3859), submitted by Sen. Gruening in July 1968, was similar to the plan described in S. 1964 a year earlier; it gave the Interior Secretary the ability to "issue permits to Natives in Alaska giving them the exclusive privilege for not more than fifty years from the date of this Act to hunt, fish, trap, and pick berries ... on any land in Alaska that is owned by the United States. Such use shall not preclude other uses of the land, and shall terminate if the land is patented or leased." None of these bills advanced beyond the committee stage. [10]

On April 15, 1969, the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs broke new ground when it submitted S. 1830, the "Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1969." S. 1830, among its other provisions, introduced the term "subsistence" to the legislative lexicon. [11] Section 13 of the bill, which addressed the "Protection of Subsistence Resources," stated that the Interior Secretary

shall, after a public hearing, ... determine whether or not an emergency exists with respect to the depletion of subsistence biotic resources in any given area of the State and may thereupon delimit and declare that such area will be closed to entry for hunting, fishing, or trapping, except by residents of such area ... The closing authorized by this section shall not be for a period of more than three years, and may be extended by the Secretary after hearing, and a published finding that the emergency continues to exist. [12]

This bill (both its subsistence provisions and other elements) was considerably revised and expanded over the following year. [13] As noted above, S. 1830 passed the Senate in July 1970 but, owing to inaction in the House, it did not become law.

During the next few months, additional effort was expended toward perfecting the bill's subsistence provisions, so by the time the Interior Department introduced a new land claims bill the following January (S. 35), the subsistence title (Section 21) had doubled in length. It continued, with some modifications, the provisions contained within S. 1830. In addition, it gave the Interior Secretary the power "to classify ... public lands surrounding any or all of the Native Villages ... as Subsistence Use Units," and it was those units that the Interior Secretary was empowered to close if, as noted above, "subsistence biotic resources" became depleted. According to longtime AFN attorney Donald Mitchell, the subsistence section in S. 35 "wasn't particularly friendly toward Native interests" and was not the product of any AFN officials. He averred that its probable author was David Hickok, a staff member on the Federal Field Committee for Development Planning in Alaska. [14]

As S. 35 made its way through the legislative process that year, its subsistence provisions became further refined, and by October 1971 a four-page subsistence title had emerged. It included provisions for both subsistence units and for closure of such units if necessary, as the January iteration of the bill had delineated. In addition, it specified that the various Native villages described in the Act "shall designate the areas ... which (A) historically have been used for subsistence purposes by their members, and (B) still are necessary, desirable and in use for such purposes." The Alaska Native Commission, which would be created by the Act, was empowered to determine the amount of these "subsistence use permit lands" for each village; the total amount of these lands for all villages would be 20,000,000 acres. The title further stated that "five years after the issuance of each subsistence use permit, and every five years thereafter, the Secretary shall review the question of whether the area still is being use for subsistence purposes. If the Secretary finds ... that the area is not being so used in whole or in part, he shall terminate the permit with respect to the unused lands." As in the January version of S. 35, Natives were not consulted on any of the language contained in Section 21. [15]

These subsistence provisions were included in the bill that passed the Senate in early November. But the House-passed bill omitted any such provisions, primarily because Wayne Aspinall (D-Colo.), the head of the House Interior Committee, felt that existing law was sufficient to provide these protections. When the House-Senate conference committee met to iron out the differences between the two bills, the powerful Aspinall prevailed on the Senate conferees to accept the House bill as it pertained to the all-important subjects of land and money. (It did so despite two last-minute appeals to the contrary by the Alaska Federation of Natives.) The remaining, "B-List" sections of the bill—that dealt with subsistence and other management issues—were referred by Senator Alan Bible (D-Nev.) to Alaska's Congressional delegation for resolution. These issues were decided, to a large extent, at a meeting in Senator Stevens's office on Saturday, December 4. Meeting attendees included the state's Congressional delegation (Rep. Nick Begich and senators Ted Stevens and Mike Gravel), along with Alaska Governor William A. Egan and Attorney General John Havelock. No Alaska Natives were present. A memorandum that was prepared after that meeting recommended that no subsistence provisions should be included in the bill reported by the conference committee. The conference, in turn, accepted that recommendation. Natives, upon hearing the news of what had transpired at the weekend meeting, were outraged at being excluded and were similarly chagrined at many of the group's conclusions. They were not, however, angry at the lack of a subsistence provision. Subsistence, at the time, was "not a political issue," and conflicts over subsistence resources on Alaska's public lands were few and far between. [16]

Although the bill, as signed into law, lacked a specific subsistence provision, the conference report accompanying the bill expressly stated that the bill protected Native subsistence users. A section of the report that was probably written by David Hickok noted the following:

The conference committee, after careful consideration believes that all Native interest in subsistence resource lands can and will be protected by the secretary through the exercise of his existing withdrawal authority. The secretary could, for example, withdraw appropriate lands and classify them in a manner which would protect native subsistence needs and requirements by closing appropriate lands to entry by non-residents when the subsistence resources of these land are in short supply or otherwise threatened. The conference committee expects both the secretary and the state to take any action necessary to protect the subsistence needs of the Natives. [17]

Alaska conservationists, who had become increasingly active during the 1960s, were concerned when they heard about the large amounts of acreage that were being considered as part of the various Native claims settlement bills. (This concern had been growing ever since State land selections had begun a decade earlier.) Conservationists' concerns, which were also shared by officials in the various Federal land management agencies, resulted in pressure to include a special lands provision in any Native claims bill that emerged from Congress. This provision, its proponents hoped, would call for a survey and evaluation of the Alaska's federal lands for parklands, wildlife refuges, and other "national interest" lands. [18] The head of the influential Federal Field Committee for Development Planning in Alaska, Joseph Fitzgerald, recognized as early as 1966 that planning for a multifaceted "park complex" would be central to any Native claims settlement, and Fitzgerald assigned David Hickok, a member of his staff, to work with Congressional leaders on a national interest lands provision that would be included in Native claims legislation.

Federal land management officials, during this period, were also active in the planning arena. The Interior Department, in accordance with the Multiple Use and Classification Act of 1964, was charged with reviewing its lands to determine which should be disposed of and which should be retained under multiple use management, and by the late 1960s the Bureau of Land Management had completed a classification scheme in the Iliamna Lake area. [19] The National Park Service, for its part, had been planning for potential Alaska parklands since the fall of 1964. By the late 1960s it had already completed a number of initial planning studies, and provisions for park planning had gained a more broad-based legitimacy through the efforts of Interior Secretary Walter Hickel's Alaska Parks and Monuments Advisory Commission and the Federal Field Committee for Development Planning in Alaska. [20]

Legislative efforts to include a national interest lands provision had begun early. Such a provision was included in S. 1830 (which the Senate had passed in 1970), and due to pressure from conservationists, it was also included in various bills that the Senate Interior and Insular Affairs Committee considered in 1971. On the House side, conservation-minded representatives John Saylor (R-Pa.) and Morris Udall (D-Ariz.) had announced in May that they intended to introduce an interest lands provision, but due to lobbying by Natives, the State of Alaska, the oil industry, and administration officials, an amendment calling for a national interest provision was defeated in both the House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee and the full House. But Alan Bible (D-Nev.), a member of the Senate Interior and Insular Affairs Committee, vowed to fight for a national interest lands provision, and when he introduced such an amendment on the Senate floor on November 1, the Senate regarded it as non-controversial and handily accepted it. In the House-Senate conference committee, the interest lands provisions was considered on December 9, and the conferees readily agreed to the provision—specifically, a provision that would give the Interior Secretary authority to withdraw up to 80 million acres, to be studied for possible inclusion to either the national park, wildlife refuge, wild and scenic river, or national forest systems. [21] This provision, known as the "d-2" provision because it was located in Section 17 (d) (2) of ANCSA, was the fundamental engine that drove NPS planning in Alaska for the remainder of the decade.

|

|

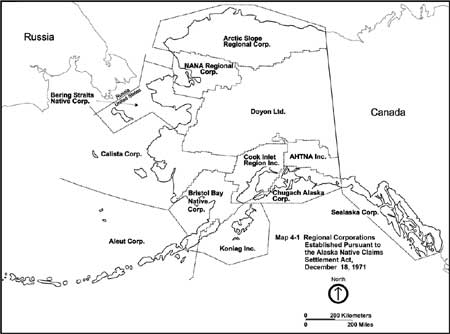

Map 4-1. Regional Corporations Established

Pursuant to the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, December 18,

1971.

(click on image for an

enlargement in a new window)

|

B. The Interior Department Begins Planning for New Parks

The National Park Service, which managed less than seven million acres of Alaska land in December 1971, reacted to ANCSA's passage by commencing an immediate, whirlwind effort to identify and evaluate lands for consideration as National Park System units. On December 21, just three days after the bill signing, Director George Hartzog assigned Theodor Swem, the agency's Assistant Director for Cooperative Activities, to coordinate the agency's Alaska effort; six days later, Swem requested the assistance of Richard Stenmark of the Alaska Group Office in Anchorage in identifying and evaluating proposed withdrawal areas. [22] The NPS and other land management agencies acted quickly because they had to: according to the timetable laid out in ANCSA, they had just 90 days to make a preliminary withdrawal of d-2 lands and nine months to issue a final withdrawal order. Given that timetable, agency officials hurriedly compiled what meager resources they had on Alaska's outstanding natural and cultural areas; they then began assembling an ad hoc planning team that was intended to provide information and guidance about potential parklands—either new NPS units or extensions to existing units.

On March 15, 1972, Interior Secretary Rogers C. B. Morton made the preliminary withdrawal of d-2 lands. (See Table 4-1 at right.) They comprised the following areas (names in italics are of present park units).

The combined acreage of the twelve proposed new units and two park additions totaled some 45 million acres. Significantly, the NPS made no provision, during this initial withdrawal, for land that would later be included in either Kenai Fjords National Park or Cape Krusenstern National Monument, and the initial withdrawal also failed to include any additions to Glacier Bay National Monument. [23]

In May 1972, just a few weeks after Morton's withdrawal, NPS Assistant Director Ted Swem brought a contingent of NPS planners to Alaska, and for the next several months the team fanned out across the state and did what it could to gather information about these and other potential parklands. NPS staff also worked with other Interior Department agencies to coordinate the land withdrawal process. [24] On September 13, Interior Secretary Morton issued his final 80,000,000-acre land withdrawal, which included 41.7 million acres for new or expanded NPS units. During the six-month study period, the NPS dropped several areas and added new ones, so that the September withdrawal areas largely approximated the areas—at least in name—that Congress adopted several years later.

Once the withdrawal process was completed, the NPS and the other land management agencies had another major ANCSA-imposed deadline to meet: the completion, by mid-December 1973, of master plans and draft environmental impact statements for each of the proposed national interest lands units. In response to that mandate, these agencies began to intensively study the areas that they had selected; they studied each unit's wildlife and fisheries, inventoried cultural resources, assessed interpretive themes and tourist potential, local and area transportation patterns, and performed other research tasks intended to demonstrate the suitability of these areas to Congress and the public.

As part of that information gathering effort, these agencies responded to the data they gathered by increasing or decreasing the size of the various proposed units; and in response to conflicts between these agencies, the total acreage assigned to each agency's withdrawals changed as well. This fine-tuning took place during various increments between late 1972 and late 1973, and it continued throughout the following year during the agencies' preparation of final environmental statements for each of the various proposed units. Table 4-2 on the facing page shows the extent to which unit acreages changed during this period.

Table 4-2. Evolution of Proposed NPS Areas, September 1972 to January 1975

| Area Name (Sept. 1972) |

Area Name (Dec.1973/Jan. 1975) |

Study Area Acreage | ||

| Sept. 1972 | Dec. 1973 | Jan. 1975# | ||

New Areas: | ||||

| Aniakchak Crater | Aniakchak Caldera | 740,200 | 440,000 | 580,000 |

| (none) | Cape Krusenstern | (none) | 350,000 | 343,000 |

| Gates of the Arctic | Gates of the Arctic | 9,388,000 | 8,360,000 | 9,170,000 |

| Great Kobuk Sand Dunes | Kobuk Valley | 1,454,000 | 1,850,000 | 1,854,000 |

| Imuruk | Chukchi-Imuruk | 2,150,900 | 2,690,000^ | 2,708,000 |

| Kenai Fjords | Harding Icefields-Kenai Fjords | 95,400 | 300,000 | 305,000 |

| Lake Clark Pass | Lake Clark | 3,725,620 | 2,610,000 | 2,821,000 |

| Noatak | Noatak | 7,874,700 | 7,500,000* | 7,590,000* |

| Wrangell-St. | Wrangell-St. Elias | 10,613,540 | 13,200,000@ | 14,140,000@ |

| Yukon River | Yukon-Charley Rivers | 1,233,660 | 1,970,000 | 2,283,000 |

Additions to Existing Park Units: | ||||

| Katmai National Monument | 1,411,900 | 1,187,000 | 2,054,000 | |

| Mount McKinley National Park | 2,996,640 [25] | 3,180,000 | 3,210,000 [26] | |

# - The various final environmental statements were issued between November 1974 and February 1975; January 1975 was chosen as a midpoint during the publication process.

^ - In Dec. 1973, Chukchi-Imuruk National Wildlands was a joint proposal between NPS and the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife (BSF&W), but by January 1975 the unit proposal was for Chukchi-Imuruk National Reserve, to be administered by the NPS.

* Proposals called for the Noatak National Ecological Reserve (in Dec. 1973) and the Noatak National Arctic Range (in Jan. 1975) to be jointly managed by the BSF&W and the Bureau of Land Management. It is included here because of Noatak's eventual inclusion as an NPS unit.

@ - In December 1973, the Wrangell-St. Elias area was divided into a Wrangell-St. Elias National Park (NPS, 8,640,000 acres) and the Wrangell Mountain National Forest (USFS, 4,560,000 acres); by January 1975, the acreage of the NPS area was still 8,640,000 acres while the USFS area had risen to 5,500,000 acres.

|

|

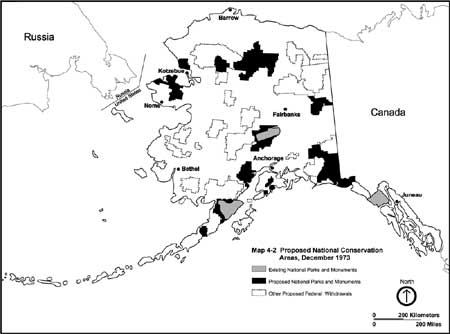

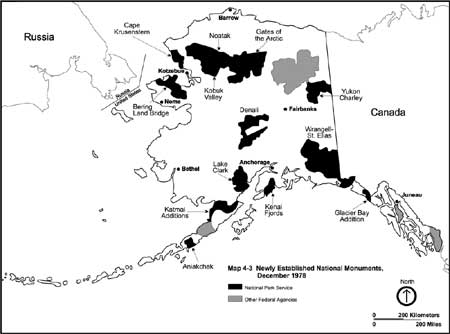

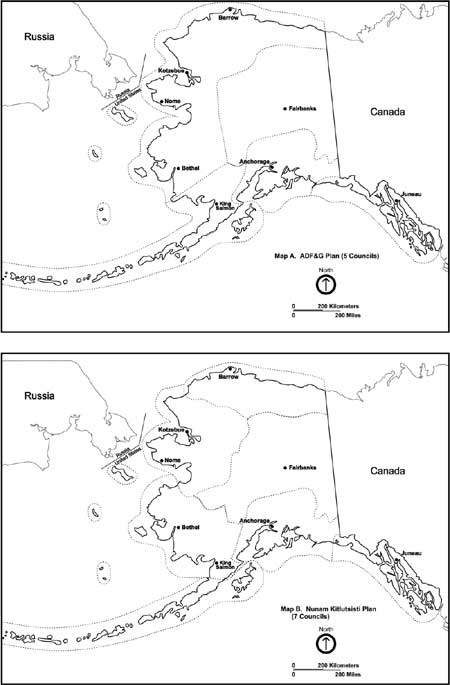

Map 4-2. Proposed National Conservation Areas,

December 1973.

(click on image for an

enlargement in a new window)

|

C. NPS Planners Consider the Subsistence Question

Driven by the promise of vast new additions to its system, [27] National Park Service leaders in the wake of ANCSA's passage began their planning effort, hoping in the process to maximize the number of acres in new or expanded park units—provided, of course, that the resources included in those areas were of sufficient caliber to warrant NPS designation. Subsistence values were a secondary consideration. Agency planners, recognizing ANCSA's generous land conveyance provisions, took care to avoid including village sites in the various proposed park units. Beyond that consideration, however, they had no compunction about including subsistence use areas within the various proposed units. Never, either at this early stage or at any other time in the proposal process, did any NPS official propose redrawing proposed boundary lines in order to exclude subsistence users. As historian Frank Williss has noted, the NPS's new approach—of preserving large ecosystems as a primary goal rather than providing for recreational and developmental needs within the parks—was one witnessed, to some extent, throughout the National Park System. Because of the acreages involved, however, the tilt toward preservation (combined, simultaneously, with a concern for the protection of traditional land uses) was more pronounced in Alaska than elsewhere. [28]

At the time of ANCSA's passage, subsistence activities had been taking place throughout Alaska for hundreds if not thousands of years. Urban as well as rural residents harvested subsistence resources; both Natives and non-Natives participated in a subsistence lifestyle. Some depended on subsistence resources more than others; a subsistence-based lifestyle remained healthy and strong in many areas, while in several areas subsistence activities were becoming less important. [29] But NPS planners, along with other federal officials, were only vaguely cognizant of these and other essential facts about Alaska's subsistence lifestyle. (The initial definition of subsistence, according to one early planner, was "timber and game for local use.") [30] NPS officials, as a consequence, commenced the park proposal process relying more on preconception and supposition than on hard, verifiable data. It is not surprising, therefore, that the agency's initial subsistence-related proposals were dramatically transformed during the planning process that preceded the passage of Alaska lands legislation.

The NPS made its first public utterance about subsistence activities in the proposed parks in July 1972, when it issued a short report documenting values and issues related to its various proposed units (as listed in the March 1972 preliminary withdrawals). This report, which paved the way for the revised recommendations that Secretary Morton issued two months later, expressly condoned the legitimacy of the Alaska Native cultures when it stated that

Nowhere else in America are the landscapes and life communities so directly and obviously involved with the cultural heritage of the people. In its growing involvement with cultural themes, the National Park Service would expect to work closely and successfully with the Alaskan natives to ensure that new parks in Alaska are not only expressive of a national land ethic but also of the cultural heritage of these Alaskans. [31]

|

| Inupiat hunters hauling a seal kill just offshore from the proposed Cape Krusenstern National Monument during the summer of 1974. NPS (ATF Box 13), photo 4465-20, by Robert Belous |

The report was less specific about overtly condoning the legitimacy of subsistence uses. It did, however, briefly describe subsistence activities (including harvesting areas and species hunted) for the various proposed park units. Seen from a historical perspective, the report's approach to subsistence appears unpolished—there are several references to "subsistency" hunting and fishing—but because virtually no subsistence data existed that pertained to the national interest lands, the newly-obtained information proved highly valuable. [32] Significantly, subsistence uses as described in the report seem to apply only to Alaska Natives. One shortcoming of the report was its failure to mention any human uses in the proposed Aniakchak Crater unit. (This omission was corrected in subsequent reports.) In addition, the report noted that in the proposed Katmai extension, "many of [the] animals [in the proposed unit] have never been hunted by man and know little fear of him;" and regarding the proposed Kenai Fjords unit, the report noted that human use "tends to be extremely light, with fishermen being the most numerous public intruders." These notes, brief as they were, may have set a precedent because the Alaska Lands Act, as passed in 1980, did not authorize subsistence activities either in Kenai Fjords National Park or in the newly-expanded portions of Katmai National Park. [33]

Shortly after the release of the July 1972 park proposal document, state and federal authorities settled a legal matter in a way that had far-reaching ramifications on the future of Alaska subsistence. The conflict was over land claims. The previous January, the State of Alaska—which had been unable to file any claims during the years preceding ANCSA's passage—had filed for 77,000,000 acres under the Statehood Act. Two months later, however, confrontation arose when Interior Secretary Morton made his initial 80,000,000-acre national interest lands withdrawal. A month later, the state sued over the legality of some 42,000,000 acres that had been claimed by both governments. The land-claims conflict, if allowed to fester, threatened to derail the national interest lands planning process, but on September 2, the state announced that it had agreed to drop its lawsuit and its claim to the contested acreage. In return for that action, however, the state was allowed to select large blocks of national interest lands that had been part of the Gates of the Arctic and Mount McKinley park proposals. In addition, the state extracted a crucial concession: that some 124,000 acres of land in the Aniakchak Crater proposal area would be open to sport hunting. [34] Before long, NPS and Congressional authorities recognized that lands in other proposed park units also needed to provide for sport hunting; and as noted below, Congressional approval of the first two NPS-administered "national preserves" in October 1974 created a classification under which sport hunting could be authorized. The September 2, 1972 agreement, in short, proved to be the wedge that, years later, resulted in 19,000,000 acres of national preserves in Alaska.

Between September 1972 and December 1973, as noted above, a primary purpose of the NPS's Alaska Task Force was the further investigation of the various proposed park units, and the fruits of that investigation were encapsulated in various master plans and draft environmental impact statements (DEISs). To a large extent, the NPS forged its subsistence policy during that time. (Most of this was ad hoc policymaking, although Bob Belous of the NPS, in November 1973, completed an interim report on subsistence use in the proposed parklands at the behest of Assistant NPS Director Ted Swem and Alaska Task Force Director Al Henson. [35]) Most if not all of the documents produced in December 1973 included a separate section discussing subsistence, and the subsistence recommendations emanating from these documents are a logical outcome of those discussions.

Most of these recommendations were surprisingly consistent with one another. In statements that presaged the possibilities for both cultural change and ecological degradation, the various DEISs and master plans typically made the following recommendation:

Except as may otherwise be prohibited by law, existing traditional subsistence uses of renewable resources will be permitted until it is demonstrated that these uses are no longer necessary for human survival. If the subsistence use of a resource demonstrates that continued subsistence uses may result in a progressive reduction of animal or plant resources which could lead to long range alterations of ecosystems, the managing agency, following consultation with communities and affected individuals, shall have the authority to restrict subsistence activities in part or all of the park. [36]

|

| Inupiat woman poling a boat in northwestern Alaska, 1974. NPS photo by Robert Belous |

In a notable departure from the implications suggested in the July 1972 document, all of the units proposed to be added to the National Park System, including Kenai Fjords and the Katmai extension, included provisions for subsistence within their DEISs. Another notable change was that race was no longer a factor in determining subsistence eligibility. [37] But clouding the picture was the fact that many subsistence users would be competing with others for the available resources. This was because the proposals for six of the nine new NPS areas—Aniakchak Caldera, Chukchi-Imuruk, Gates of the Arctic, Lake Clark, Wrangell-St. Elias, and Yukon-Charley—allowed sport hunting to continue. This state of affairs was doubtless spurred by pressure from hunting groups and was a logical outgrowth of the September 1972 decision that had ensured the continuation of sport hunting in portions of the Aniakchak proposal. [38]

Particular attention was paid to subsistence at five of the proposed parks. In the Wrangell-St. Elias National Park proposal document, an extended discussion on the subject detailed differences between subsistence and sport harvests, and it also included several harvest tables that had been prepared by a resource management team from the Joint Federal-State Land Use Planning Commission. [39] At Kobuk Valley, a primary purpose of the NPS proposal was "to foster the continuation of the Alaska Eskimo culture by providing for traditional resources uses, such as hunting, fishing, and gathering, provided such uses are consistent with the preservation of primary resource values." To accomplish that goal, the agency proposed that the monument be closed to sport hunting, and perhaps to justify the proposed hunting ban, the draft EIS provided an extensive discussion of the Eskimos' strong dependence on subsistence harvests for their food intake. [40] Noatak, similar to Kobuk Valley, was singled out as an area where subsistence activities were a central aspect of the proposal. Stating that "the Noatak Valley represents the largest undeveloped and pristine river valley in the United States ... best characterized as a vast primitive expanse by virtue of low human numbers, scant development, outstanding scenery, and concentrations of wildlife," the draft EIS concluded that the Noatak and adjacent Squirrel River basins were "of significant value as natural, undisturbed laboratories," in large part because "such areas are practically nonexistent in the conterminous United States, and are becoming increasingly rare worldwide." Based on that premise, a primary purpose of the so-called Noatak National Ecological Range—to be jointly managed by the Bureau of Land Management and the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife—was "to continue to make available renewable natural resources for subsistence uses, and to protect and conserve these resources for all Americans." As with the Kobuk Valley proposal, the Noatak document provided extensive data to demonstrate area residents' dependence on locally available fish, game, and other food sources. [41] A fourth proposal in which subsistence values were emphasized was the Chukchi-Imuruk National Wildlands document. A primary purpose of this unit, which was to be co-managed by the the NPS and the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, was the "interpretation of the ecological, geological, cultural, and scenic features and processes of the area, with emphasis on developing understanding and respect for an alternative cultural system as exemplified by the present day American Eskimo culture." [42]

A final proposal in which extensive attention was paid to subsistence lifeways and resources was at Gates of the Arctic. Of particular interest at the proposed park were the Nunamiut people—so-called mountain Eskimos—who resided at Anaktuvuk Pass. As historian Ted Catton has explained in remarkable detail, these villagers were historically anomalous to other northern Alaskan residents in that they were inland, nomadic people whose diet and lifestyle revolved around caribou and their migrations. By 1900, however, most of the Nunamiut had moved to the Arctic coast, and by 1920 the mountains were probably entirely deserted. (So-called "push factors"—namely, a crash in the caribou population—were the primary cause of the migration, but the "pull factors" of whaling ships, trading posts, and mission schools along the Arctic coast may have also played a role.) During their tenure along the coast many Nunamiut learned English, adopted Christianity, and absorbed other aspects of American culture. But the lure of the mountains (and a rebound in the caribou population) caused the group to migrate seasonally away from the coast, and after 1939 they gave up traveling to the coast altogether. In 1943, a Nunamiut group was "discovered" by pilot Sigurd Wien at the north end of Chandler Lake; two years later, a USGS surveyor witnessed a Nunamiut caribou hunt. [43]

In 1949, the Nunamiut—five families from Chandler Lake, followed by eight families from the Killik River—moved to a plateau at the headwaters of the John River and founded the village of Anaktuvuk Pass; before long a school, airstrip, and church were established at the site. [44] The Nunamiut, like other Native peoples, welcomed these and other trappings of modern civilization. Non-Natives who encountered them, however, were mesmerized by the more traditional aspects of culture that they represented. Located in the isolated wilderness of northern Alaska, and carrying on many traditions that had remained unchanged for hundreds of years, those who visited—and wrote about—the Nunamiut identified this so-called "lost tribe" as being uniquely "ancient," "Stone Age," and "timeless." This distinction, whether it was accurate or not, was shared by anthropologists, government planners, and other observers, and it fit neatly into the widely-held notion—largely promulgated by conservationist Robert Marshall—that the central Brooks Range was the "ultimate" or "last great wilderness." [45] A series of anthropologists, drawn to Anaktuvuk Pass, were so enamored by what they saw that they encouraged the Nunamiut to value their primitiveness. The villagers responded to these visits amicably enough; even so, they marched ahead and—to the dismay of many—acquired new technology as the occasion demanded. By doing so, they lost much of their charm in the perception of non-Natives, many of whom were ardent wilderness enthusiasts. The Nunamiut, sensitive to these changing attitudes, soon began to feel that they were being treated as intruders in their own homeland. [46]

It was in the midst of this process—in which outsiders' admiration of the Nunamiut's traditional lifestyle was being tempered by the invasion of new technology—that the NPS began considering a parkland in the central Brooks Range. The agency, at the behest of Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, had first considered the area as a park unit back in 1962, when he had sponsored the visitation of a film crew to the Arrigetch Peaks area. Political sensitivities forced Udall to leave that film footage on the proverbial cutting room floor, and the park idea was shelved for the time being. [47] Then, in June 1968, an NPS team again reconnoitered the area. (During that visit, planner Merrill Mattes acidly noted that Anaktuvuk Pass was "not exactly Shangri-La.") The report resulting from that visit recommended a 4.1 million-acre, two-unit Gates of the Arctic National Park; the two units of that park, perhaps in deference to the Nunamiut presence, were drawn well away from Anaktuvuk Pass and the John River valley. That park proposal, along with proposals pertaining to Mount McKinley National Park, Katmai National Monument and four non-Alaska park areas, were forwarded to Interior Secretary Stewart Udall in a package that became known as "Project P." This package, which was forwarded to President Lyndon Johnson in January 1969—in the last few days before Richard Nixon was inaugurated—proved controversial. As a result—and several reasons have been speculated behind his action—Johnson signed proclamations pertaining to only three of the seven park proposals. Of the Alaska proposals, Johnson agreed to sign only the Katmai expansion proclamation; left unsigned were proclamations to create Gates of the Arctic National Monument, along with a proposed 2.2 million-acre expansion to Mount McKinley National Park. [48]

No sooner had the monument proposal been rejected than progress—in the form of a winter haul road—thrust its way up the John River Valley and through Anaktuvuk Pass. The road, dubbed the "Hickel Highway," was carved out during the midwinter months of 1968-69, and for six weeks after its completion large trucks roared through the village. A similar scenario repeated itself for a few weeks the following winter. [49] Then, in December 1971, came ANCSA's passage, and with it came the legal right for newly organized regional and village corporations to select land in and around Anaktuvuk Pass. [50]

It was in the atmosphere of these changes that the NPS resurrected its Gates of the Arctic park proposal. At first, NPS planners (who were hired in May 1972) paid little attention to the area's Native populations. The July 1972 proposal boundaries, for example, stayed more than 12 miles away from Anaktuvuk Pass, and the brief report on the park proposal merely noted that "caribou and moose are hunted mainly for subsistence by local people, many of whom depend upon the game for most of their food." [51]

Shortly after the issuance of that report, Native interests began to recognize that the National Park Service might well be an ally in their cause. Anticipating (or perhaps hoping) that the NPS would protect their subsistence resources, the Nunamiut Corporation (the newly-established village corporation for Anaktuvuk Pass) and the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation (the regional corporation encompassing the village) began to entertain the idea of a permanent dual-ownership arrangement. Sensing common ground with the NPS, Native officials formalized this idea on April 23, 1973, when ASRC's president testified before the Joint Federal-State Land Use Planning Commission that the Inupiat Eskimos were in favor of a Nunamiut National Park that would be cooperatively managed by the NPS and the Eskimos. This bold action was the first proposal of its kind in Alaska. [52]

|

| Drying fish nets near Ambler, September 1974. NPS (ATF Box 10), photo 4765-7, by Robert Belous |

In response to the ASRC proposal, NPS planner John Kauffmann began discussing with the Nunamiut just how such a park plan might jibe with the agency's own proposals. What emerged from those discussions was a proposal, issued in December 1973, for a tripartite park unit. The eastern and western thirds of the central Brooks Range would be designated the Gates of the Arctic Wilderness Park; in this 7,130,000 acre area, which the NPS would manage, subsistence hunting by Natives would be permitted, but non-Native sportsmen would be limited to "fair-chase hunting." (The fair-chase concept, hearkening back to the methods practiced by elite sportsmen decades earlier, suggested a minimum ten-day stay in the wilderness and a lack of dependence on radio and other communications.) Sandwiched between the two units of the wilderness park, an area called the Nunamiut National Wildlands was proposed. In that 2,390,000-acre expanse, which included Anaktuvuk Pass and adjacent areas, management would be largely similar to that of the wilderness park. In the wildlands, however, subsistence hunting would take priority over sport hunting, and the NPS, the Nunamiut Corporation, and the ASRC would cooperatively manage the area. Ironically, the continuation of subsistence activities was not an expressly stated purpose of either the wilderness park or the wildlands proposal; instead, the wildlands proposal was more generic. It stated that a primary purpose would be "to assure that the outstanding cultural, natural, and recreational resources in the area are managed in a manner which will perpetuate the resource values for public use and benefit." [53]

The NPS, at both the local and national levels, and the various Native parties were all in full agreement with the proposal as outlined above. But the Federal government's Office of Management and Budget (OMB) was not. On December 16, 1973—just one day before the Interior Secretary's deadline to forward this and the other park proposals to Congress—the OMB rejected the National Wildlands concept, which was to have been applied to both the Nunamiut and Chukchi-Imuruk proposals. As noted in an errata sheet that was stapled to the front of each draft EIS, the OMB explained that the national park system should not be encumbered with new area designations. Much to the chagrin of Interior Department officials, the OMB refused to countenance proposals in which the NPS shared its management authority with non-Federal parties (in the Nunamiut case) or with other Federal agencies (in the Chukchi-Imuruk case). In the Nunamiut case, OMB was willing to allow a cooperative agreement issued by the Interior Secretary allowing a Native corporation "mutually compatible administration" of park lands; in the Chukchi-Imuruk case, Interior Department officials reacted to OMB's dictum by declaring that the NPS would administer the area. [54]

As noted above, the period between September 1972 and December 1973 witnessed a huge increase of NPS knowledge about land use activities on lands being proposed for inclusion in park units, and the issuance of the various DEISs in December 1973 reflected the agency's increasing sophistication toward subsistence matters. The various DEISs, by proposing the continuation of subsistence activities in all of the proposed park units, clearly showed that the NPS was sensitive to the needs of both Native and non-Native subsistence users. (See Table 4-3, opposite page.) The Federal government, moreover, openly advocated subsistence as a core value in two proposed park units (Kobuk Valley and Noatak [55]), and in the Gates of the Arctic proposal, the NPS supported a unit—the Nunamiut National Wildlands—that would be jointly managed with two Native corporations. The OMB's rejection of the latter proposal tempered the agency's future actions toward that park proposal, but it in no way diminished the agency's philosophical attitudes toward the value of subsistence in that area. The NPS, quite apparently, had a special recognition toward subsistence values in the proposed northern-tier parks: Gates of the Arctic, Noatak, Kobuk Valley, Cape Krusenstern, and Chukchi-Imuruk. As former employee Bob Belous noted, the agency had no intention of downplaying the significance of subsistence activities in the other proposed park areas. Subsistence in the northern tier parks, however, "was more susceptible to publicity," and the photographs and descriptions that emanated from the various NPS proposal documents for these park units often highlighted Natives, Native harvesting, and Native craft items. [56]

Table 4-3. Subsistence Eligibility in the Proposed Alaska Parklands, 1973-1980

| Proposed Park Unit |

12/73 DEIS | 1/75 FES | 10/77a HR 39 |

10/77b HR 39 | 2/78 HR 39 | 5/78 HR 39 |

10/78 S 9 | 12/78 Proc. | 1/79 HR 39 |

5/79 HR 39 | 10/79 S 9 | 12/80 Law |

| Aniakchak | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y(t) |

| Bering Land Bridge | Y* | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | (Y) | Y | Y | Y | (Y) | (Y) |

| Cape Krusenstern | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Gates of the Arctic | Y* | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y(t) | Y | Y | Y | Y(t) | Y(t) |

| Kenai Fjords | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Kobuk Valle | Y* | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Lake Clark | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y(t) |

| Noatak | Y* | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | (Y) | Y | Y | Y | (Y) | (Y) |

| Wrangell-St. Elias | Y* | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y(t) |

| Yukon-Charley R's | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | (Y) | Y | Y | Y | (Y) | (Y) |

| Denali Additions | Y | Y | N | Y! | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y(t) |

| Glacier Bay Add'ns | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Katmai Additions | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Alagnak Wild. R.@ | -- | -- | N | N | Y | Y | Y | -- | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Note: The above chart covers subsistence uses on proposed new lands only. Several of the units noted above, at various times during the proposal process, had both parks (or monuments) and preserves. In those cases, the above use decisions pertain only to the proposed parks or monuments; in all of the adjacent preserves, subsistence uses are allowed. The names given for the proposed park units are those in the final (Dec. 1980) bill; other names, as noted elsewhere, were often used in the various environmental statements or draft legislative bills.

Document Identification:

DEIS = Draft

Environmental Impact Statement; FES = Final Environmental Statement; HR

39 = House Bill 39; 10/77a = 10/12/77 Committee Print #1; 10/77b =

10/28/77 Committee Print #2; S 9 = Senate Bill 9, Proc. = Presidential

Proclamation; Law = Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act,

signed 12/2/80.

Symbols on Chart:

Y = subsistence is sanctioned

N = subsistence is prohibited

Y(t) = subsistence is sanctioned "where such uses are traditional"

Y* = subsistence is sanctioned, and additional measures are proposed to

protect subsistence values

Y = subsistence is a purpose of the proposed parkland

Y = "protecting the viability of subsistence resources" is a

purpose of the proposed parkland

(Y) = subsistence is sanctioned by virtue of its status as a proposed

national preserve

Y! = subsistence is sanctioned only on the proposed North Addition

@ = Alagnak Wild River was in an "area of environmental concern" near

the proposed Katmai National Park in 1973 and 1975. In the 95th

Congress, the House continued to treat the Alagnak as part of a proposed

Katmai addition. But S 9, in Oct. 1978, gave it separate treatment,

and bills in the 96th Congress did the same.

D. NPS Subsistence Activities in Alaska, 1972-1973

After NPS planners, as part of their work with the Alaska Task Force, turned in their recommendations about proposed park units to Congress in December 1973, the focus of the park planning process officially moved from the executive to the legislative branch. Congress, however, showed little interest in the matter; as Frank Williss has noted, "Neither the Nixon nor the Ford administrations showed any inclination to work for passage of the bill in 1974 or subsequent years." NPS staff, however, remained active on the issue. The agency continued to carry on an intensive effort to gather data that would be available as Congress deliberated the measure; much of that activity, at least initially, was directed toward the preparation of final environmental statements for the various proposed park units. [57]

During the preparation of the draft and final environmental documents, NPS personnel were active in other spheres that dealt with subsistence uses and Native relationships in Alaska. One focus of activity was a renewed spotlight on the Native Alaskan heritage center idea. As noted in Chapter 3, an NPS planning team in 1968 had recommended the establishment of at least three Alaska Native cultural centers: that is, easily-accessible sites where both visitors and Alaska residents could learn about Native Alaskans and their lifeways. That idea had not emerged from the proposal stage, but within a year of the passage of ANCSA in late 1971 the idea of a series of heritage centers that would "collect, document, and preserve local artifacts and ... display them in a meaningful, organized manner" was presented in a NPS report. [58]

The report, which compiled both Native and non-Native ideas related to the topic, shied away from specific recommendations. Instead, the report suggested a range of alternatives: one or more state centers (primarily for tourists) that would represent all Alaska Natives, one or more regional centers (for both tourists and Natives) that would be located in each regional corporation's geographical boundaries, and a series of village centers (primarily for villagers) that would "provide communal focal points ... so important to village social life and necessary for village cohesiveness." The NPS, for its part, offered technical and organizational capabilities; it also offered staff that might assist with the design and implementation process (although the agency "should not primarily serve as the final producer of working plans"). The agency even suggested a series of pilot projects and a list of regional corporations that might logically adopt those projects. It did not, however, offer major funding for such centers; money to build and maintain these facilities would need to come either from grant programs of private organizations and foundations or from the regional corporations themselves. [59]

So far as is known, this report did not result in any immediate action toward implementing heritage centers in Alaska. The concepts presented in the report, however, did not winnow away. During the 1970s, several entities considered the idea, but the idea remained in the conceptual stage until after the passage of the Alaska Lands Act. In 1987, momentum finally began to build when various Native organizations founded a group dedicated to planning and constructing such a center. That group surmounted numerous obstacles in its quest. By the summer of 1994 they had obtained a 26-acre parcel, and on May 8, 1999 the Alaska Native Heritage Center opened to the public. The site has been open on a year-round basis ever since. A detailed account of the process that resulted in the center is noted below. [60]

Throughout this period, NPS officials were dealing with ongoing issues relative to allowable activities within the existing parklands. As Chapters 2 and 3 have suggested, subsistence uses at Mount McKinley National Park and Katmai National Monument were not an issue; regulations at these and most other U.S. park units prohibited hunting, subsistence fishing, trapping, and other consumptive uses. At Glacier Bay National Monument, however, the agency's official prohibitions were tempered by the recognition that harbor seal harvesting, berry picking, and other subsistence activities had long been practiced by Tlingits residing in nearby Hoonah. In recognition of that fact the Interior Department had adopted, with some misgivings, a laissez-faire attitude; NPS Director Arno Cammerer, in 1939, had noted that the agency had "no intention of making any sudden changes in the uses which the Indians have been accustomed to make of the monument area," and in December 1946 that attitude was reflected in an agreement forged in Washington between the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the NPS. [61] That agreement, again with some misgivings, was renewed in 1954, 1956, 1958, and 1960. But the March 1964 discovery by NPS rangers of scores of Native-killed harbor seal carcasses forced the agency to rethink its previous position in the matter. The recognition that at least some Hoonahs were harvesting seals for commercial purposes, and the inability to legally separate the few market hunters from others who made only occasional use of the monument's subsistence uses, caused some park officials to conclude that there was no easy way to sanction Native seal hunting without jeopardizing the monument's resources. [62]

Park officials, at the suggestion of the agency's Washington hierarchy, decided to let the seal problem subside, and the agency tried its best to ignore the problem for the remainder of the decade. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, with its multitudinous provisions, had the potential to address this problem. But as noted above, the Act did not contain a provision protecting Native people's historic uses of public lands for subsistence purposes, and a solution to Glacier Bay's subsistence dilemma remained unsolved. [63] But less than a year later, on October 21, 1972, President Nixon signed the Marine Mammal Protection Act into law. The law's primary thrust was the prohibition of marine mammal harvesting. Specifically excluded from the prohibition, however, was "any Indian, Aleut, or Eskimo who dwells on the coast of the North Pacific Ocean or the Arctic Ocean." The Act condoned subsistence harvesting, and it also allowed a limited commercial use of the harvested animals. But it did not allow these Natives to engage in a blatant commercial harvest, nor did it allow marine mammal harvests to be "accomplished in a wasteful manner." [64]

Feeling empowered by provisions in the Act, Glacier Bay Superintendent Robert Howe wrote to his superior, Alaska State Director Stanley T. Albright. In that letter, written just five days after the Act's passage, he asked for authority to terminate harbor seal harvesting in the monument. Howe noted that "We truly believe that seal hunting in Glacier Bay is neither legal nor longer necessary. In fact, considering the new national legislation it might be illegal anywhere when 'hide hunting' is the end result." Three weeks later, Albright telephoned Howe and asked him to inform Hoonah's residents that their harvesting privileges in the monument had been terminated. Whether he immediately did so is uncertain, and the first documented communication on the matter between the NPS and Hoonah residents did not take place until January 1974, when the monument's chief ranger telephoned Hoonah's mayor, Frank See, and told him about the hunting prohibition. The agency never put the rule against Native hunting in writing, nor did it ever hold a public meeting on the subject. But perhaps because the mayor and other Hoonah residents were in the midst of other matters that were just as critical to the community—if not more so—agency officials received no protests regarding the hunting ban. Beginning in 1974, therefore, the NPS maintained an official prohibition against Native hunting in Glacier Bay. [65]

E. Studying the Proposed Parks, 1974-1976

After the NPS and other Federal land management agencies, as required by the ANCSA timetable, turned in the various draft EISs and master plans for the proposed conservation areas in December 1973, emphasis turned toward the preparation of a series of final environmental statements (FESs). To a large extent, changes in the EISs would be based on the tenor of public comment. In addition, however, the gathering and analysis of new data by agency staff brought more changes. As in the rest of the Alaska planning effort, there was little time to lose; final documents which incorporated both the additional field work and the heavy volume of public participation had to be completed and published in little more than a year. [66]

In order to prepare the various final environmental statements, NPS personnel fanned out across the state during the summer of 1974. The preparation of the FESs took place that fall. They were completed and distributed to the public between December 1974 and February 1975.

In their approach to subsistence, the recommendations in the various FESs were even more far-reaching than those in the December 1973 draft EISs. All proposed NPS units, for example, were still open to valid subsistence uses. As in the various draft documents, almost all of the final environmental statements issued the following boilerplate statement, which was similar to (though more specific than) language in the December 1973 documents:

Except as may be otherwise prohibited by Federal or State law, existing traditional subsistence uses of renewable resources will be permitted until it is determined by the Secretary of the Interior that utilization not physically necessary to maintain human life is necessary to provide opportunities for the survival of Alaskan cultures centering on subsistence as a way of life. If it is demonstrated that continued subsistence uses may result in a progressive reduction of animal or plant resources which could lead to long range alterations of ecosystems, the managing agency, following consultation with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, communities and affected individuals, shall have the authority to restrict subsistence activities in part or all of the park unit. [67]

|

| By 1968, when this photo (in Barrow) was taken, snowmachines were beginning to replace dog teams throughout rural Alaska. NPS (ATF Box 8), photo by Merrill J. Mattes |

Additional subsistence-related proposals were also offered. Most of the proposals for NPS-administered units—in fact, all but the Gates of the Arctic and Yukon-Charley proposals—included proposed park purposes that related to either Native subsistence activities or other Native activities. [68] The two strongest of these statements were at Cape Krusenstern, where the NPS promised "to encourage and assist in every way possible the preservation and interpretation of present-day Native cultures," and at Kobuk Valley, where the agency stated its intention "to foster the continuation of the Alaska Eskimo culture by providing for traditional resource uses, such as hunting, fishing, and gathering, provided such uses are consistent with the preservation of primary resources values." [69] Three proposed park units—Aniakchak, Harding Icefield-Kenai Fjords, and Lake Clark—had as a purpose "to provide for Native involvement in ongoing monument operations, research, and the provision of visitor services" [70] Both the Katmai and the Lake Clark proposals included language, in their park purposes, calling upon the agency "to encourage and foster cooperative agreements between the NPS and Native groups [as well as with other entities] to help assure optimum use of the region's resources" [71] Still other park purposes were for "developing understanding and respect for ... the present-day American Eskimo culture" (for the Chukchi-Imuruk proposal) and "to insure that ... traditional Native lifestyles and subsistence uses are allowed to continue" (for the Harding Icefields-Kenai Fjords proposal). [72] Provisions pertaining to access were also offered. At Aniakchak, the agency promised to "work with Natives in providing for access to lands in the monument in which Natives have interests," and the Gates of the Arctic FES stated that "The Secretary [of the Interior] may authorize snowmobile use for subsistence purposes within the park." The Gates of the Arctic document, in addition, introduced the traditional use concept. "Traditional subsistence use of the park," it noted, "will be allowed to continue." The document later went on to define as traditional such activities as hunting, fishing, trapping, and fuel gathering. [73]

A key element in the preparation of the various FESs was the growing expertise about the proposed parks by NPS staff. Some of these employees specialized in particular themes—geology or zoology, for example—but others immersed themselves in the study of particular clusters of park units. This expertise had begun back in the spring of 1972, when the agency had decided to organize four study teams to collect information for the various proposed park units. The initial captains of these study teams, chosen in May of that year, were John Kauffmann, Paul Fritz, Urban Rogers, and John Reynolds; in addition, the agency assigned Zorro Bradley to head a fifth team that would study historical and archeological areas and provide cultural resource assistance to the other four teams. [74] During the preparation of the draft and final EISs the personnel heading the study teams changed; Paul Fritz and Urban Rogers, for instance, were replaced by Gerald Wright and Fred Eubanks, respectively. Beginning in early 1975, however, the level of park expertise dramatically increased when Director Gary Everhardt decided to add ten new professionals to the planning team. These "keymen," as they were called, were given the task of gathering and coordinating knowledge about individual park units. John Kauffmann, who since 1972 had been spearheading the agency's efforts for several proposed parks in northwestern Alaska, became the keyman for the Gates of the Arctic proposal, but most of the other keymen transferred to their new positions from the Denver Service Center. [75]

In addition to their park responsibilities, each of the keymen was assigned an additional collateral duty, and one high priority project in the latter category was the preparation of a subsistence policy statement. Robert Belous, the keyman for the Cape Krusenstern and Kobuk Valley proposals, had written an interim subsistence report back in November 1973; as a follow-up, he issued a Subsistence Policy for Proposed NPS Areas in Alaska, completed in September 1975. Belous then teamed up with Dr. T. Stell Newman, the keyman for the Chukchi-Imuruk proposal, and in April 1976 the two completed a Draft Secretarial Policy: Subsistence Uses of New National Park Service Areas in Alaska. Newman wrote a final subsistence policy document, The National Park Service and Subsistence: A Summary, which was issued in November 1977. [76] The 1976 draft policy was "widely circulated in Alaska for public comment" (according to language in the 1977 study), and the comments generated in response to that draft helped mold the Secretary of the Interior's position on subsistence when he submitted the Department's proposals to Congress in September 1977. In prefatory remarks for the 1977 study, Newman noted that in order to gain a "better understanding of this unique lifestyle," the NPS had conducted "over ten man-years of professional anthropological research ... on the nature of subsistence in the proposed parklands." [77]

|

| Bob Belous worked for the NPS in Alaska from 1972 through the early 1980s. Besides his excellence as a photographer, he played a major role in forging the agency's subsistence policies. NPS (AKSO) |

As historian Bill Brown has noted, a major source of philosophical guidance for agency officials during this period was ecologist Raymond Dasmann and his concept of the "future primitive." Dasmann, in a seminal 1975 paper on the subject, noted that it was "a good time to reexamine the entire concept of national parks and all equivalent protected areas." "Is it not strange," he stated, that park managers the world over had "taken for granted that people and nature were somehow incompatible"? After suggesting that the world was divided into "ecosystem people" (that is, people who were members of "indigenous traditional cultures") and "biosphere people" (that is, "those who are tied in with the global technological civilization"), he noted that ecosystem people were institutionally fragile because they were dependent upon a single ecosystem for their survival. Historically, he noted, only biosphere people had created national parks. But because of a sharp rise in global development, ecosystem-based homelands were rapidly diminishing. Concerned about that trend, he urged that a profound change be instituted in how national parks should function. "National parks," he noted, "must not serve as a means for displacing the members of traditional societies who have always cared for the land and its biota." "Few anywhere would argue with the concept of national parks," he continued, "but many would argue with the way the concept has been applied—too often at the cost of displacement of traditional cultures, and nearly always with insufficient consideration for the practices and policies affecting the lands outside of the park." He therefore made several specific recommendations. First, "The rights of members of indigenous cultures to the lands they have traditionally occupied must be recognized, and any plans for establishing parks or reserves in these lands must be developed in consultation with, and in agreement with, the people involved." In addition, Dasmann urged that "wherever national parks are created, their protection needs to be coordinated with the people who occupy the surrounding lands. Those who are most affected by the presence of a national park must fully share in its benefits...." NPS officials recognized that their options were limited in the various long-established parklands of the Lower 48 states. In Alaska, however, the millions of acres being considered as new national parklands provided an excellent tableau where Dasmann's ideas might be manifested. [78]

|

| G. Bryan Harry, who served as director of the NPS's Alaska Area Office from 1975 to 1978, called Belous a "gigantic philosophical champion of Natives in the national parks." NPS (AKSO) |

All three of the documents that Belous and Newman produced from 1975 to 1977 were philosophically consistent with, and were logical extensions of, the recommendations that had been laid out in the draft and final EISs. The documents were unequivocal regarding the legitimacy of subsistence activities in the various proposed park units. The 1975 study, for example, noted that the NPS "recognizes that the continuance of such harvest of wild food and other biological resources from lands currently proposed as additions to the National Park System ... is an important opportunity for retaining an unbroken link with the Nation's cultural past." It further noted that

The goal of this proposed policy on subsistence use of renewable resources on national parklands created under ANCSA is to provide the opportunity for rural Native people engaged in a genuinely subsistence-centered lifestyle to continue if they so desire, to allow such people to decide for themselves their own degree of dependency and the rate at which acculturation may take place.

Portions of the 1975 draft policy, as noted above, suggested a preference for Native use. Other parts of that policy, however, backed off from that preference. Subsistence permits, for example, would be issued to "local residents who have demonstrated customary and consistent use of [Subsistence] Zones for the direct consumptive use of renewable resources at the time of enactment of ANCSA," a local resident being defined as "a Native or non-Native living in the vicinity of a Subsistence Zone and making consistent and customary use of the Zone for subsistence purposes." The 1976 and 1977 documents made clear that Natives and non-Natives would have equal access to subsistence resources; as noted in the 1976 report, "The need for subsistence resources is not the exclusive claim of Native people in Alaska.... This is consistent with the Alaska State Constitution which recognizes no racial priority but considers all citizens equal under the law." [79]

Other key areas of subsistence policy were first discussed and evaluated in these documents. The idea of a Subsistence Resource Council as a local management element first arose in the 1975 statement, as one leg in a "tripartite" arrangement that would also include the NPS and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. The rationale that demanded the existence of a series of subsistence councils also brought about the insistence that subsistence resources be managed on a regional basis. The study noted that "Because of broad variations in subsistence use patterns and problems across the state ... each unit will be managed under a separate and distinct management plan with a local subsistence resource council representing each unit." Third, the agency made it clear that the proposed subsistence provisions, appropriate as they were, would pertain only to the Alaska parks. The 1976 study noted that because the allowance of subsistence principles comprised "a distinct departure from longstanding NPS management principles," it was therefore "imperative that such design and management departures ... are not to be a precedent for alteration of park system management for existing units in or outside the State of Alaska."

A final theme the various policy statements covered was the subsistence zone idea. The policy writers made it clear that subsistence, in the agency's opinion, was a modern as well as a traditional land use, and that "ancient aboriginal ways of life [should not] be artificially restored or preserved as a static remnant of the past through legislation or prohibition." But even though the agency had no intention of generally suppressing subsistence activities, it did conclude that subsistence uses should not be allowed throughout all of the proposed park units. As the 1976 document made clear,

Not all parklands proposed under ANCSA, or regions within such parklands, are of equal importance for subsistence purposes. Areas of special importance and consistent utilization will be designated as "Subsistence Zones." The Secretary will designate such Zones following consultation with the local Subsistence Resource Council and the State Department of Fish and Game.

The 1977 document reiterated the contrast in subsistence dependency; it noted that "Subsistence needs and practices vary widely across the state, from a major dependence in the northwestern Alaska proposals to scant dependence in most other proposed parklands." It also took the subsistence zone idea from the general to the specific; it contained maps outlining proposed subsistence zones for all but three of the proposed parks. No subsistence zone was planned for Aniakchak, either because data was unavailable or because subsistence use was deemed "slight," and subsistence zone maps were omitted for the Glacier Bay extensions and for the Noatak proposal because insufficient data was available to delineate an accurate use area.

Another activity that the NPS undertook during the 1974-1976 period—one that played a large role in delineating the various subsistence zones noted above—was the completion of a series of studies on subsistence use in the various proposed parks. As has been noted, virtually no data was available about subsistence use in the national interest lands prior to ANCSA, and park planners eagerly sought subsistence data to help guide the evolving legislative proposals. The preparation of these studies was entrusted to the University of Alaska's Cooperative Park Studies Unit, which had been established in 1972 to stimulate park-related research. One of CPSU's two subentities was the Anthropology and Historical Preservation Program, which was headed by Zorro Bradley, an NPS anthropologist and adjunct faculty member at the Fairbanks campus. [80]