|

Alaska Subsistence

A National Park Service Management History |

|

Chapter 5:

INITIAL SUBSISTENCE MANAGEMENT EFFORTS

On December 1, 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed a proclamation that established seventeen national monuments covering some 55,965,000 acres of Alaska land. The NPS that day was put in charge of thirteen monuments; the other four were to be administered by either the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or the U.S. Forest Service. Of the ten new monuments and three expanded monuments placed under NPS stewardship, the proclamation decreed that "the opportunity for the local residents to engage in subsistence hunting ... will continue under the administration of this monument" in every case, except in the new Kenai Fjords National Monument. With a flourish of his pen, therefore, President Carter legitimized subsistence activities on some 40,210,000 acres of newly proclaimed NPS-managed land. [1]

A. Establishing a Regulatory Framework

|

| In 1979, and again in 1981, Michael Finley helped craft regulations (primarily related to subsistence) for Alaska's new NPS units. Finley later served as the superintendent for both Yosemite and Yellowstone national parks. NPS (AKSO) |

As was noted in Chapter 4, the NPS and other land management agencies had known since mid-October 1978 that Congress would not be able to produce an Alaska lands bill prior to the December 17 deadline, and since mid-November there had been some inkling that the president would be issuing a proclamation to protect those lands until such time as Congress was able to act. Immediately after President Carter issued his December 1 proclamation, Interior Department officials recognized that the state could not enforce a ban on hunting in the new monuments and the Department could not enforce the proclamation's other provisions. The department, therefore, assembled a three-person, Washington-based team—Molly N. Ross and Thomas R. Lundquist from the DOI's Office of the Solicitor, and Michael V. Finley from the NPS's Division of Ranger Activities and Protection—that began assembling management regulations for the new monuments. The process of compiling and approving the new management regulations would take several months; in the meantime, established NPS management regulations prevailed in all of the newly-designated monuments. [2]

The team quickly recognized that the new Alaskan monuments were distinct from other national monuments because of various subsistence and access provisions contained in the president's proclamation. In order to legitimize those activities, which were technically illegal under existing management regulations, and to calm the fears of many rural Alaskans, both the NPS and the Fish and Wildlife Service issued final interim rules on December 26—effective immediately—allowing relaxed subsistence and access provisions. [3] In an Interior Department directive published in the January 15, 1979 Congressional Record, Secretary Andrus noted that the regulations were "aimed at giving short term guidance on issues such as subsistence and access on the new monuments." They were issued, he noted, "in order to modify existing NPS regulations which may have barred, among other things, subsistence activities by local rural residents and in-holders, and routes and methods of access to areas within and across the new national monuments." The temporary regulations specifically stated that the new monuments would be open to subsistence hunting, fishing, and trapping, and also allowed the use of airplanes for subsistence purposes. Regarding commercial trapping, NPS official Robert Peterson determined—inasmuch as the 1978-79 trapping season was already underway—that the activity would be allowed for the remainder of the season. [4]

Meanwhile, two team members (Molly Ross and Michael Finley) continued their work, often meeting with—and paying close attention to—the core subsistence group in the NPS's Anchorage office. On February 28, 1979, the NPS published an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking in the Federal Register. From that date until April 6, the agency solicited public comments regarding how the new national monuments should be managed. Comments were solicited in the following subject areas: aircraft access; unattended and abandoned property; firearms, traps, and nets; illegal cabins; firewood; pets (i.e., dog teams); subsistence; hunting and trapping; and mining. The public reacted to the comment period by submitting 1,979 letters, all but 248 of which were form letters from the Alaska Outdoor Association. Ross and Finley spent the next several months sifting through the comments; the document that emerged from their analysis was signed by Robert L. Herpst, the Interior Department's Assistant Secretary for Fish and Wildlife and Parks, and was published as a twenty-page proposed rule in the June 28, 1979 Federal Register. [5] For the next ninety days, the public was invited to submit comments on the general management regulations. The NPS, hoping to elicit the broadest possible response, held well-advertised public hearings in both Anchorage and Fairbanks in mid-August; in addition, "informal public meetings were held in virtually every community affected by the proposed rules." [6] The agency received a total of 245 public comments by the September 26 deadline, and it was anticipated that a final rule would be issued on November 1. But in a surprise move, Interior Department officials took no further action in the matter. They perhaps reasoned that the Final Interim Rule that had become effective on December 26, 1978 was sufficient for administering the newly-established monument lands for the time being, but they also recognized—or perhaps hoped—that Congress would soon pass an Alaska lands bill, which would demand the preparation of a new set of management regulations. [7] Therefore, the public comments that were submitted during the summer of 1979 were held in reserve awaiting a more permanent outcome from Congress.

The regulations outlined in the proposed rule covered a broad range of topics, and they played a central role in how subsistence activities would be managed, both in the immediate and long-term future. The regulations, for example, made the first statements about how the NPS would regulate aircraft use; they stated that fixed-wing aircraft would be allowed, although park superintendents had the ability to ban their entry on either a temporary or permanent basis under certain specified circumstances. Regarding cabin use, those who used cabins on NPS land could continue that use, at least for the time being; those who used cabins built before March 25, 1974 could obtain a renewable five-year permit, while cabins built after that date were eligible for only a non-renewable, one-year permit. [8] Regarding weapons, the regulations distinguished between recreational users, who could carry only firearms, and local rural residents authorized to engage in subsistence uses who "would be permitted to use, possess and carry weapons, traps and nets in accordance with applicable State and Federal law." Motorboat use would be generally permitted, except in various small lakes in Lake Clark National Monument; off-road vehicles would be restricted to "established roads and parking areas;" and snowmobiles "would be permitted only in specific areas or on specific routes." In all three cases, park superintendents would have the power to restrict access on either a temporary or permanent basis. [9]

|

| A major discussion point in the formulation of the 1979 regulations centered on where, and to what extent, aircraft would be allowed for subsistence uses. Paul Starr photo |

The topic of subsistence, officials readily agreed, "was perhaps the most divisive of all the issues submitted for comment." Members of the Alaska Outdoor Association submitted 1,731 form letters opposing any subsistence program that did not allow all Alaskans to share equally in the state's fish and wildlife resources. Urban Alaskans generally favored state control and rural Alaskans favored federal control. [10] The NPS, however, proposed "a hybrid State/Federal structure as suggested by the comments from the major environmental organizations, the AFN, and several other commentors." At the time, differing subsistence management schemes were being proposed in the various "d-2" bills on Capitol Hill, and the Service "selected and combined the features which it believes best accommodate the management needs of the new Alaska National Monuments." [11]

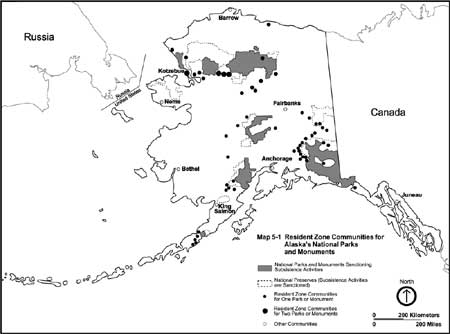

The subsistence section of the proposed rule broke new ground by defining "local rural residents" and by proposing that eligibility should be based either on residence in a so-called residence zone or on the possession of a designated subsistence permit. The regulations specified that there would be 39 designated "resident zone communities." [12] (See Table 5-1, following page.) In addition, Section 13.43 of the regulations provided specific criteria under which residents who lived outside those communities could qualify for subsistence permits. A special provision for Gates of the Arctic National Monument allowed Anaktuvuk Pass residents to use aircraft, under certain circumstances, to conduct subsistence activities; another, for Lake Clark National Monument, prohibited the subsistence hunting of Dall sheep. [13]

Table 5-1. Resident Zone Communities for Alaska National Parks and Monuments, 1979-1981

|

Aniakchak N.M.: Bering Land Bridge N.M.: Cape Krusenstern N.M.: Denali N.M./N.P.: Gates of the Arctic N.M./N.P.: Katmai N.M.: |

Kobuk Valley N.M./N.P.: Lake Clark N.M./N.P.: Wrangell-St. Elias N.M./N.P.: Yukon Charley N.M.: | |

Note: A = added | ||

During the seven-month period in which the proposed management regulations were being formulated and subject to public comment, NPS officials attempted to establish a management structure that would complement the vast new acreage that the president and Congress were in the process of bestowing. For more than a decade prior to the December 1978 presidential proclamations, the NPS had supported a central-office presence in Alaska; it had been variously known as the Alaska Field Office, the Alaska Group Office, the Alaska State Office and, most recently, the Alaska Area Office. When Alaska Area Office Director G. Bryan Harry, in September 1978, transferred to Honolulu to become director of the NPS's Pacific Area Office, NPS Director William Whalen let it be known that his replacement, whoever it might be, would serve as an ad hoc regional director. John E. Cook, whom Whalen picked for the job that month, was a third-generation NPS employee who had previously served as both an Associate Director in Washington as well as the Southwest Regional Office director. Whalen picked him, in large part, because he "has had more experience setting up new park system areas than anyone I know. ... The actions we take and do not take in Alaska now will set the tone for our work there for decades to come." Cook, for his part, was equally excited about the challenge, averring that it was "too good an opportunity to pass up." Well before he assumed his position in March 1979, Cook made it clear that he would report directly to Whalen. Cook would serve as Area Director in name only; in due time, he would become the agency's first regional director for Alaska. [14]

Throughout much of 1979, both before and after the proposed rule was issued, the NPS had virtually no ability to administer the many bureaucratic functions that might have logically followed from President Carter's proclamations. Because Congress had played no role in establishing the various monuments, and because the agency had little advance notice of their establishment, the NPS in large part was forced to administer the new monuments using existing resources. The agency knew full well that many Alaska residents were openly hostile to the establishment of new national parklands, and a large-scale protest near Cantwell and more small-scale protests in communities surrounding Wrangell-St. Elias and Yukon Charley Rivers national monuments were obvious manifestations of that hostility. [15] Those attitudes clearly indicated that the agency should take a cautious, incremental approach toward its newly acquired lands, and considering the budgetary situation, the NPS had few other options. The agency estimated that the management of the monuments during Fiscal Year 1979 would cost between $3.5 million and $5.2 million. Personnel ceilings and budget constraints, however, prevented the agency from assigning new people to the monuments or acquiring management facilities, and its request to reprogram existing funds for the purpose was denied. [16]

Despite a general lack of funds, Alaska Area Director John Cook realized that specific situations—the hunting season, for example—demanded an NPS presence, and he felt that the agency should pursue an "aggressive, selective enforcement of sport hunting" in the newly-designated monuments. In the summer of 1979, therefore, he recruited and organized a 22-person team, all of them on loan from other NPS regions. By August 1 the so-called "Ranger Task Force" was on duty in Anchorage, and team members remained in various Alaska-based positions until the hunting season began to taper off. During the winter of 1979-80 the NPS again had a minimal presence in the new monuments; Cook was, however, able to hire three permanent, full-time rangers whose sole responsibilities would be managing the new monuments. [17] Staffing remained largely absent until the late summer of 1980, when the agency deployed a smaller group, informally known as the "Ranger II Task Force." The 1979 and 1980 task force rangers had a wide variety of responsibilities: patrolling huge areas, answering hundreds of questions about the monuments, searching for downed aircraft, and issuing citations (when necessary) for illegal hunting. [18] Most of their hunting-related work involved sport hunting. Subsistence conflicts doubtless surfaced from time to time, but rangers issued no citations during this period for violations of subsistence regulations.

B. ANILCA and its Management Ramifications

The agency's presence in the new monuments remained small and only occasionally visible until December 2, 1980, when President Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act. This act established by statute that subsistence hunting, fishing, and gathering would be legitimate activities on some 41,458,000 acres of new parklands. The lands under consideration were much the same as those in the national monuments that had been designated two years earlier. [19] Section 1322 of ANILCA, however, had abolished the national monuments; that act of abolition, by extension, also nullified the interim management regulations that had been effective since late December of 1978.

In the wake of ANILCA's passage, NPS officials scurried to assemble a management authority for the newly established park units. A major task that had to be undertaken immediately—even before the various superintendents were hired—was the creation and implementation of management regulations for the newly expanded parklands. As was the case in late 1978 and early 1979, haste was warranted in the issuance of regulations. As noted in the Federal Register, "many of the[se] provisions relieve the otherwise applicable restrictions of [existing regulation], which are inappropriate in the unique Alaska setting. For example, standard restrictions on access, firearms, preservation of natural features, abandoned property, and camping and picnicking are relieved by these regulations." [20]

|

| John Cook was chosen to direct the NPS's Alaska office in September 1978 and remained at the helm in Anchorage until 1983. NPS (AKSO) |

The task of drafting the management guidelines fell to five Interior Department employees. Solicitors Molly Ross and Thomas Lundquist, and Michael Finley, now part of the Department's Division of Legislation, were veterans of the effort that had compiled the 1979 regulations; joining them were Maureen Finnerty, of the NPS's Division of Ranger Activities and Protection, and William F. Paleck, from the NPS's newly-established Alaska Regional Office in Anchorage. [21] Using as a template the June 1979 Proposed Rule, the 245 letters that had been submitted during the 90-day period that followed its issuance, the changes in land status between the 1978 proclamations and the 1980 Congressional act, and ANILCA's legislative history, [22] Ross and Finley issued a new Proposed Rule for Alaska's newly-established parklands on January 19, 1981 and gave the public 45 days—until March 6—to submit comments on the proposed regulations. [23]

The January 1981 regulations, in fact, differed significantly from those that had been announced in the proposed rule issued nineteen months earlier. Some of the changes, to be sure, were obvious adjustments to the units that had been designated in ANILCA; others, however, were modifications based either on public testimony or the changed opinions of NPS decision makers. In the subsistence section, for example, the January 1981 regulations defined a family for the first time; changed the method by which resident zones were determined; changed the system (in Sec. 1344) under which people living outside resident zone communities could conduct subsistence activities; deleted the prohibition of specific uses (Dall sheep hunting and motorboat use) in the new Lake Clark unit; added Cantwell to the list of subsistence zone communities; and modified numerous other subsistence-related provisions. [24] A key contributor to the tone of the new regulations was NPS planner Dick Hensel, formerly of the Fish and Wildlife Service, who urged that the regulations be as flexible as possible; due to the vagaries of subsistence harvesting patterns, he averred that "subsistence is not a regulatory program in its usual sense" and worked to have the regulations reflect that fluidity. [25]

The public was given until March 16, ten days later than originally scheduled, to submit comments. A four-person team—everyone on the January 1981 team except Michael Finley—then began to analyze the 391 submitted comments. [26] The team was operating under a severe, self-imposed time constraint—the agency had announced in January that it hoped to issue final regulations in late March—but the volume and complexity of comments forced the team to make a more deliberate effort. A Final Rule was not published until June 17, 1981. [27] The rule was made "immediately effective to provide public guidance in time for peak park use seasons." Federal regulators, moreover, recognized that the regulations were not the last word; they were "the minimum necessary for interim administration of Alaska park areas." They also promised that "[f]urther rulemaking efforts will involve more expansive public guidance on the implementation and interpretation of ANILCA." [28]

Comments were submitted on a variety of subject areas, but subsistence issues continued to be both vexatious and contentious; as noted in the Federal Register, "the issue of subsistence continues to be the most difficult of all the issues affecting the new National Park Service areas in Alaska." The State of Alaska, and many in-state groups, felt that the federal government should play no role in regulating subsistence, particularly during the first year following ANILCA's passage. In deference to those attitudes, the agency agreed to delete a system of residence zones and subsistence permits as they pertained to the national preserves, although it stood firm in its conviction that it would manage subsistence activities in preserves as well as in the parks and monuments. In another compromise with Alaska-based interests, the regulations did not contain any provisions that would have immediately implemented sections 806 (federal monitoring), 807 (judicial enforcement), 810 (impacts on land use decisions), and 812 (research). The agency, however, averred that it had "certain basic responsibilities" to carry out the other provisions of ANILCA as they pertained to subsistence activities. The NPS had no problem with the state's regulation of subsistence activities so long as it was consistent with federal law; the agency, in fact, anticipated "that a State subsistence program, implementing ANILCA's various mandates, [would] eventually supersede most federal regulation of subsistence." [29]

The NPS recognized that the definitions of certain terms would be an important aspect of subsistence management, and in recognition of that importance, the agency discussed several terms that had been incorporated into ANILCA. Regarding "healthy" and "natural and healthy" (as noted in Sections 802(1), 808(b), and 815(1)), the regulations did not explicitly define either term, although explanatory paragraphs sprinkled throughout the regulations shed light on their applicability. The agency also chose not to define the terms "customarily and traditionally," suggesting instead that establishing such a definition demanded additional comment, research, and advice from various local advisory bodies. In addition, it modified the application of the "customary trade" concept that had been propounded in both the June 1979 and January 1981 proposed rules to include the "making and selling of certain handicraft articles out of plant materials" in Kobuk Valley National Park and a portion of Gates of the Arctic National Preserve. [30]

The terms "local resident" and "rural resident" had been used in ANILCA, and because only "local rural residents" (either subsistence permit holders or those who lived in resident zone communities) were eligible to carry on subsistence activities, the regulations sought to define the term more specifically. The regulations suggested specific criteria—tax returns, voter registration, and so forth—that would help determine whether an individual qualified as a "local rural resident," and they also listed specific cities and towns that, in the agency's opinion, either qualified or did not qualify as "rural" communities. But this list was by no means exhaustive; another effort, at some later date, would need to more clearly define the boundary line between urban and rural. [31]

Regarding the "where traditional" clause (which pertained to five of the newly-established park units), the NPS—perhaps on Dick Hensel's advice—chose not to designate any specific hunting zones. Instead, it noted that various local advisory bodies "should facilitate such local input into these designations." The agency warned, however, that "local rural residents should comply with ... Congressional intent ... by not hunting in any areas [of these five park units] where subsistence hunting has not, in recent history, occurred." [32]

In regards to the determination of resident zones, the NPS recognized that it was treading a narrow, median pathway. At one extreme was the state, which wanted to abolish all resident zones, thus opening up subsistence hunting opportunities to all regardless of their residence; while at the other extreme, conservation groups wanted resident zones replaced by subsistence permits, thus ensuring that only well-established hunters would be allowed subsistence hunting privileges in the national parks and monuments. The NPS, guided by ANILCA's legislative history, insisted that resident zones would be the primary mechanism for determining subsistence eligibility; in deference to the state, however, the agency agreed to adopt a more liberal definition for what constituted a bona fide resident zone community. [33] Because of that liberalized definition, the number of resident zone communities increased for most of the new park units, and the total number of communities near national parks or monuments rose from 31 to 53. (See Table 5-1.) The agency hoped, by selecting a relatively large number of resident zone communities, to reduce the number of subsistence users that would need to obtain subsistence permits. (These became known as "13.44 permits" because they were discussed in Sec. 13.44 of the final regulations.) [34]

|

| The first group of seasonal employees to work in Alaska's parks after ANILCA's passage met in June 1981; several became experts on subsistence matters. Top row, left to right: Dick Ring* (GAAR), Kim Bartel (YUCH), Mary Hoyne (WRST), Timothy Wingate (LACL), Ray Bane* (GAAR), Jacquelynn Shea (GAAR). Second row: George Wuerthner (GAAR), Linda Lee (CAKR), Debbie Sturdevant, Kit Mullen (WRST), Susan Steinacher (GAAR), Skye Swanson (GAAR). Third row: Thomas Rulland (GAAR), Gladys Commack (CAKR), Gail McConnell (CAKR), Clair Roberts (LACL), William Goebel (YUCH), John Morris. Bottom row: David Chesky (LACL), Charlie Crangle (LACL), Karen Jettmar (CAKR), William "Bud" Rice (NOAT), Maggie Yurick (GAAR), Steve Ulvi (YUCH), Mike Tollefson* (LACL). NPS (AKSO). Those marked with a * were not seasonal employees. |

During the seven-month period following ANILCA's passage in which management regulations were being drafted and approved, NPS officials in Alaska were carrying on a myriad of other activities in an attempt to establish facilities and personnel in the newly-established park units. Within weeks of ANILCA's passage, Alaska Regional Office [35] Director John Cook began hiring the first new park superintendents (see Appendix 3), and by the late spring of 1981 a skeletal management presence was on site at each of the new parks. (The number of permanent, full-time staff ranged from two to six that first year.) Considering the acreages and responsibilities involved, the initial park budgets were decidedly modest. The first park headquarters, as a rule, were humble affairs; in a few fortunate cases, the agency was able to carve out space in existing federal facilities, but elsewhere, park staffs were forced to make do with a substandard or deteriorating physical plant. [36]

Cook, who had been no stranger to confrontation during his previous management stints, recognized that anti-NPS sentiment in the aftermath of ANILCA ran high in many parts of Alaska. Agency personnel in the vicinity of many park areas, moreover, had had little interaction with local residents. In response to those conditions, Cook deliberately chose a non-confrontational management style and recommended a similar attitude on the part of his staff. The new regional director was fully aware that ANILCA's provisions, along with the newly-approved management regulations, had given the agency broad management power over the parks and park users; but he was also keenly aware that arbitrary or excessive exercise of that power would antagonize many Alaska residents. He recognized, for the time being at least, that it was of primary importance that the agency, both on an institutional and personal level, be good neighbors and low-key educators. [37]

This attitude was reflected in the agency's approach to subsistence. During the mid-to-late 1970s, when the agency was formulating its various final environmental statements and defending the proposed parks before Congress, a subsistence "brain trust" had developed among the Alaska NPS staff. The initial members of this ad hoc group, Robert Belous and T. Stell Newman, had written several subsistence policy statements (see Chapter 4), and in the late 1970s they were joined by historian William E. Brown, anthropologist (and CPSU head) Zorro Bradley, and others. Cook, recognizing the group's collective expertise, gave the group a high degree of independence in day-to-day policy formulation. That policy, carried out at the park level by the various superintendents and by rangers, was primarily educational during this period. [38] After ANILCA was passed, Belous continued to use a "soft touch" approach and made periodic, informal visits to those communities with which they had become familiar during the mid-1970s. Subsistence expert Ray Bane, who was living in Bettles at the time, made similar visits throughout northern Alaska. And park staff, most notably Superintendent C. Mack Shaver (of the Northwest Alaska Areas cluster) did likewise, hoping by their visits to establish trust, dispel rumors, and provide information about agency operations. [39]

|

|

Map 5-1. Resident Zone Communities for Alaska's

National Parks and Monuments.

(click on image for an

enlargement in a new window)

|

C. Alaskans React to the State and Federal Subsistence Laws

As noted in Chapter 4, the Alaska State Legislature passed a basic subsistence law in 1978. Governor Hammond signed it on July 12, and it became effective on October 10. Among its other provisions, the law "established in the Department of Fish and Game a section of subsistence hunting and fishing." [40] The new Subsistence Section was not given the usual management and enforcement responsibilities; instead, its role was limited to socioeconomic research and various planning functions. During its first two years, the division grew slowly; though a chief (Dr. Thomas D. Lonner), an assistant chief (Paul Cunningham), and a support person (Tricia Collins) came on board in February 1979, the Section was not actually operational until that summer. (See Appendix 1.) The first field-office positions were not filled until the fall of 1979, and the Section was not fully functioning until 1980. Once up and running, the Section began producing a series of technical reports; most were of a qualitative nature and were a direct response to regulatory proposals being considered by the Alaska Boards of Fisheries and Game. By the spring of 1981, Section personnel were working in nine different offices scattered around the state. [41] On July 1 of that year, via administrative means, the Subsistence Section was upgraded to Division status. Staff growth during this period was dramatic. [42]

| NPS Historian Bill Brown, the region's first cultural resource chief, was an influential player in subsistence policy development both before and after ANILCA's passage. Nan E. Elliot photo, from I'd Swap My Skidoo for You |

During the same two-year period, the legislature continued to keep a close eye on subsistence issues. The state's House of Representatives, for example, had a Special Committee on Subsistence that had been active since 1978 (see Chapter 4). This committee, which was dominated by members of the so-called "Bush caucus," remained active through the early 1980s. The committee during this period worked all year long; between legislative sessions it served a general oversight function for the Department of Fish and Game, collecting and distributing information on a wide range of subsistence issues and working with federal authorities on Alaska Lands legislation. [43] Perhaps because the new subsistence law had little immediate impact on hunting or fishing regulations, and because the federal government had not yet passed an Alaska Lands Act, the state legislature had little interest during this period in either modifying or repealing the 1978 subsistence law. [44]

The legislature's "wait-and-see" attitude during this period was shared, to some extent, by members of the state's Board of Game and Board of Fisheries. The joint boards, in March 1979, held a meeting before a "packed house" in Anchorage to consider adopting new regulations in the wake of the subsistence law's passage. [45] They deferred taking such a step for the time being; four days later, however, they adopted a "Policy Statement on the Subsistence Utilization of Fish and Game" that was, in large part, a reflection of verbiage in the 1978 subsistence law. In addition, they moved to publish the first booklet that was exclusively devoted to subsistence fishing regulations. (As noted in Chapter 1, subsistence regulations had been published ever since 1960, but they were scattered within the annual commercial fishing regulations booklets.) In lieu of regulations, the fish and game boards continued to apply a common regulatory framework to all harvests. Separate subsistence regulations reflective of the new subsistence law were not approved until after the Alaska Lands Act was passed. [46]

The joint boards, reacting to pressure applied by both Governor Hammond and the evolving Alaska Lands Bill, also acted on the long-simmering issue of regional advisory councils. On April 7, 1979, as noted in Chapter 4, the boards promulgated regulations that established five vaguely-defined fish and game regions, each of which would support a regional advisory council. Four of the regional councils held meetings that year. [47] A fish and game official, stressing the tentative nature of the councils, stated that

none of these regional councils are required to meet. Instead, what we intend to do is offer Advisory Committees the opportunity to meet as a regional council and to discuss regional issues ... Scheduling the meetings as we have done demonstrates the good faith of both Boards in improving the Advisory Committee system. [48]

|

| Charles M. (Mack) Shaver served as the first superintendent of the NPS's so-called Northwest Alaska Areas: Cape Krusenstern National Monument, Kobuk Valley National Park, and Noatak National Preserve. NPS (AKSO) |

Fish and Game Commissioner Ronald Skoog defended the board's role. The councils, he noted, "should help our efforts in the Congress relative to 'regionalization' as proposed in the current (d)(2) legislation. It should at least demonstrate that the State is attempting to improve the public participation process by promulgating responsive regulations and by addressing the concerns of rural residents." Speaking in early 1981, Skoog further noted that "since regional councils were established, more than half of their recommendations have been adopted." Among rural subsistence interests, however, the meetings of the newly-created councils were greeted with skepticism if not cynicism. An observer at one October 1979 meeting concluded that it was "less than completely effective in providing public input into the regulatory process," while a participant at another meeting noted it was "merely a forum for the executive director of the Boards of Fish and Game to express his personal opinions." [49]

In December 1980, the Board of Fisheries held its first hearings on the state's 1978 subsistence law. It did so in response to worries about overfishing in Cook Inlet; since the passage of the 1978 law, there had been a huge increase in the number of subsistence fishing permit applications, and a substantial increase in the subsistence salmon harvest was an inevitable result. In order to rationalize that activity, and in response to the District Court's decision in the so-called Tyonek case (Native Village of Tyonek vs. Alaska Board of Fisheries), [50] the board established ten characteristics for identifying the "customary and traditional uses" of Cook Inlet salmon. Based on those characteristics, the board decided to adopt a set of criteria drawn from them, and then to apply those criteria to various communities, groups, and individuals who wanted to conduct subsistence fishing activities in Cook Inlet. The board partially completed this task in December 1980; three months later, the board completed the task and issued its first subsistence fishing regulations under the new (1978) law. [51]

The passage of Alaska Lands Act legislation in late 1980, and the clear recognition that a rural subsistence preference was a critical adjunct of federal as well as state law, caused a furor of protest among many Alaskans, particularly urban sportsmen and their representatives. (Many blamed Alaska's Congressional delegation for the rural preference; Fairbanks resident Bill Waugaman, for example, stated that "Stevens and Young have always gone along with the Alaska Federation of Natives lobbyists" and that "it was Senator Stevens who told us in 1978 that there would be no subsistence section in the Alaska Lands Act if the state adopted its own subsistence law." [52]) Their collective frustration was expressed in two similar moves—a citizens' initiative and a legislative approach—that aimed to repeal the 1978 subsistence law.

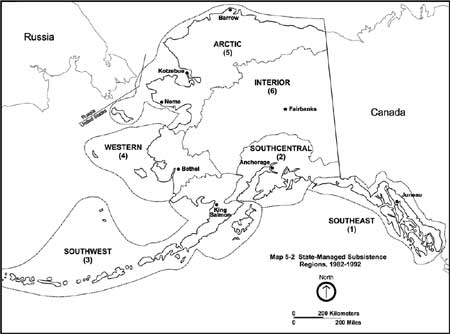

Action on the citizens' initiative, called the "Personal Consumption of Fish and Game" initiative or simply the Personal Use Initiative, was already underway within days of ANILCA's passage. Sam E. McDowell, Warren E. Olson, and Tom Scarborough submitted an initial petition for "The Alaska Anti-Discrimination Fishing and Hunting Act" on December 18; a month later, however, the Attorney General rejected it because "the title of your initiative does not accurately express the subject of the bill." Undeterred, backers rewrote the petition and submitted it again, and on March 25, the Attorney General approved the initiative and allowed its backer to begin gathering the 16,265 signatures necessary for it to be placed before Alaska's voters. [53] Broad in its approach, the initiative pledged to not only repeal existing Fish and Game Code provisions that related to subsistence hunting and fishing, but it also "would, for fishing, hunting, or trapping for personal consumption, prevent classification of persons on the basis of economic status, land ownership, local residency, past use or dependence on the resource, or lack of alternative resources."

By the time the voter's initiative had been readied for signature gathering, a legislative bill (HB 343) had been introduced by Rep. Ramona Barnes (R-Anchorage). Less than two weeks after its March 16 submittal, the House Special Committee on Subsistence held a hearing on the bill at East High School in Anchorage. Some 600 people jammed into the hearing room; according to press reports, the vast majority in attendance backed Rep. Barnes' bill. [54] The Alaska House then voted on whether to move the bill out of the Special Committee. But in a crucial April 23 test, and on three subsequent occasions, Barnes was unable to muster a majority vote. On June 3, she withdrew her bill. [55] The backers of the personal use initiative, meanwhile, worked to gather a sufficient number of signatures to secure a place on the ballot. Completed petitions were filed with the Division of Elections by January 11, 1982, and on March 5, Lieutenant Governor Terry Miller certified to the requisite number of valid signatures. Both backers and opponents geared up for a statewide vote, which would take place at the next general election on November 4, 1982. [56]

| Ronald O. Skoog served as Alaska's Commissioner of Fish and Game under Governor Hammond, from 1974 through 1982. ASL/PCA 01-4515 |

Aside from questions that surrounded the potential repeal of the subsistence law, subsistence matters were considered in a broad variety of venues during 1981 and 1982. In the spring of 1981, for example, the state Board of Game (as noted above) adopted subsistence hunting regulations. Other matters were put off until the legislative session ended, but soon afterward, state and federal authorities began a series of interactions that were designed to bring the state into compliance with ANILCA's provisions. [57] Fish and Game commissioner Ronald Skoog commenced the process on May 27 by submitting a compilation of state statutes, regulations, and other documents pertaining to subsistence. Interior Department officials, in response, met with ADF&G representatives on September 3 and discussed the documents' perceived shortcomings. Follow-up meetings were held on September 28 and 29 and again on November 5 and 6. [58] State officials dragged their feet because they were reluctant to toy with the state's regulatory and advisory system. [59] Federal officials, however, knew they held the upper hand; according to Section 805(d) of ANILCA, the federal government could legally assume control over the subsistence program if the state, by December 2, failed to adopt regulations related to definition, preference, and participation (as specified in Sections 803, 804, and 805). To conform to that timetable, ADF&G officials held a meeting of the joint game and fish boards on December 1, just one day before the deadline. At that meeting, the joint boards passed a key resolution that was intended to respond to federal concerns. [60]

Regarding issues of definition (Section 803), the combined boards recognized that ANILCA called for subsistence use only in areas where such use was "customary and traditional." Given that recognition, they initially defined "subsistence uses" as

Customary and traditional uses in Alaska of wild, renewable resources for direct personal or family consumption as food, shelter, fuel, clothing, tools, or transportation, for the making and selling of handicraft articles out of nonedible byproducts of fish and wildlife resources taken for personal or family consumption, and for the customary trade, barter or sharing for personal or family consumption.

The joint boards also defined "rural subsistence uses," and noted that the boards would "identify rural and other subsistence uses of fish or game resources" by referring to eight criteria that helped identify customary and traditional uses. (These criteria were similar to the ten "characteristics of subsistence fisheries" for the Cook Inlet Area, as noted above, that the Board of Fisheries had grappled with beginning in December 1980.) For instance, was there a long-term, consistent pattern of use? Did it recur in specific seasons of the year? Was the resource harvested near a user's residence? Were the skills involved in resource harvesting handed down from generation to generation? And did individuals use a wide variety of game and fish species? These patterns of use typified subsistence harvesting methods; as a result, affirmative responses to these and similar questions clarified "customary and traditional" uses by individuals and communities. These criteria, it should be noted, could be applied in urban as well as rural communities, and the combined fish and game boards avoided a specific definition of "rural areas" in their resolution. [61]

|

| Ramona Barnes (R-Anchorage), who served in the State House for ten terms (1979-85 and 1987-2001), was an avid states' rights advocate who, in 1982, sponsored a bill to repeal the state's 1978 subsistence law. Alaska LAA |

Another ticklish issue related to preference was a determination of how fish and wildlife resources would be apportioned in times of scarcity. The 1978 law, as noted above, had listed three criteria that outlined the degree to which local residents depended on subsistence resources. (These criteria were 1) customary and direct dependence upon the resource as the mainstay of one's livelihood, 2) local residency, and 3) availability of alternative resources.) The joint board's December 1981 resolution incorporated these criteria. Under no conditions, it noted, would fish or game managers allow populations to drop to the point that a sustained yield management regime could not be maintained. [62]

Regarding local and regional participation (Section 805), the combined boards addressed the status and role of the regional fish and game councils. As noted above, the joint boards had established five such councils in April 1979, and ADF&G officials had held meetings of four of those councils during the intervening two years. Several state legislators, in the wake of ANILCA's passage, had let it be known that "the state of Alaska currently has regulations in place and is currently operating regional councils and local councils which do all of the things enumerated in Section 805" of ANILCA. Federal authorities, however, reminded the state that ANILCA demanded at least six such councils, and that provision for these councils needed to be established by regulation. In response, the boards addressed the matter in their resolution and stated that the councils "shall take appropriate action, within their authority, to provide for rural and other subsistence uses." [63]

The joint boards, having passed a general policy on subsistence, also passed their first hunting regulations that provided for a subsistence preference. Specifically, residents of particular areas within game management units 23, 24, and 26—most of whom lived in or near newly-designated NPS units—were provided an increased opportunity to hunt Dall (mountain) sheep. [64] Having taken those actions, the joint boards were hopeful that the federal government would immediately certify their efforts and allow the state to formally assume control over the subsistence management program outlined in ANILCA. The Interior Secretary's office, however, delayed action, and for the next several months it was "engaged in a review process." [65]

Just two months after the Fish and Game Boards established a regulatory basis for the regional fish and game councils, board staff organized initial, two-day meetings for the six councils. (See Table 5-2, facing page.) The councils met during February and March 1982; a quorum was achieved everywhere except in Bethel, where the Western Regional Council met. Just as in their 1979 incarnation, each regional council was composed of the chairs of the various local advisory committees within that region; the number of committee members thus ranged from 4 to 15. [66] (See Appendix 2.) The meetings were primarily introductory, but as part of the agenda, council members were asked to nominate three people to each park or monument subsistence resource commission in their region. [67]

Table 5-2. Regional Advisory Council Chronology, 1971-present

1971 — Sen. Jay Hammond (R-Naknek) submits a bill calling for ten regional fish and game boards. It passes the Legislature, but Gov. William Egan vetoes it.

Oct. 1977 — H.R. 39 calls for a series of federally-controlled regional subsistence boards

Feb. 1978 — Revised H.R. 39 calls for between 5 and 12 state-managed regional subsistence management councils

May 1978 — House-passed H.R. 39 calls for "at least five" regional subsistence councils. The bill that passed the Senate committee in October includes an identical provision.

1979 — state legislators propose two bills; one calls for seven regional fish and game boards, the other for six regional advisory councils. Neither bill passes.

Mar.-Apr. 1979 — joint fish and game boards, following a 1978 plan, establish regulations for five fish and game regions, each with an advisory council

May 1979 — U.S. House passes H.R. 39, which calls for seven regional advisory councils

Summer-Fall 1979 — four of the five state-managed regional councils meet

Aug. 1980 — Senate-passed bill calls for "at least six" such councils. In Dec. 1980, this bill becomes law.

Feb.-Mar. 1982 — Initial meetings of the six state-managed councils. In April, the combined fish and game boards pass revised council regulations

1982-84 — Sporadic meetings of some councils; by late 1983, most were inactive.

Late 1984-early 1985 — hiring of staff coordinators signals renewed interest in RACs.

Mid-to-late 1980s — A few councils meet during 1985-86 period, but generally quiet in late 1987-early 1988. Partial revival of state councils in 1988 and 1989.

1990-92 — Shortly after federal assumption, FSB commissions study on effectiveness of regional and local decisionmaking. Study recommends federal manage- ment of regional decisionmaking; FSB adopts this alternative in April 1992. State-managed regional councils cease functioning soon afterward.

1992-93 — Selection process for regional council members and coordinators.

Sept.-Oct. 1993 — First federally-sponsored RAC meetings.

|

| During the 1970s, William P. Horn served as a staff assistant to Rep. Don Young. After ANILCA became law, he became Interior Secretary Watt's undersecretary in charge of Alaskan affairs. He remained in that position until 1988. ADN |

In the midst of these meeting dates, Interior Secretary Watt formally responded to the adequacy of the state subsistence program. In a February 25 letter addressed to Governor Hammond, Watt noted that, in most aspects, "the State program appears to satisfy section 805(d) of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act." His primary concern was that the state had "not demonstrated that it has established 'laws' which provide for all of the essential provisions" of sections 803, 804, and 805. He specifically noted that the joint boards' December 1981 resolution "cannot be relied upon to satisfy Title VIII because it has not been promulgated as a regulation and thus is not binding on the Boards of Fisheries and Game." A second difficulty, Watt noted, was that the definition of "subsistence uses" as included in the December 1981 resolution was not specific to "rural Alaska residents" as ANILCA demanded. The state program must "identify ... rural subsistence users and extend ... the section 804 priority [for rural residents] and section 805 participation scheme [for regional councils] to those users." Finally, Watt stated that during times of fish or game scarcity, the state's program "must provide that restrictions will be applied among rural residents engaged in subsistence uses; the December 1981 policy resolution gave "the highest priority to local residents in rural areas" but omitted any requirement that these residents be subsistence users. Hoping to be helpful, Watt delineated his suggestions by specific additions and deletions to text in the December 1981 policy resolution. He assured Hammond that "If enacted in its entirety as a regulation, the approach embodied in the suggested edited revision would comply with all applicable provisions of Title VIII." [68]

The next scheduled meeting of the joint fish and game board was in early April 1982. The adoption of regulations that would be compatible with ANILCA was an important agenda item, so to clarify the federal government's stance, ADF&G Commissioner Ron Skoog invited William P. Horn, the Interior Undersecretary charged with advising Watt on "d-2" issues, to speak at the Anchorage meeting. [69] (See Appendix 1.) Horn, at the meeting, put a human face on the regulations laid out in Watt's letter, and he emphasized that "the department remains, philosophically and policy wise, strongly committed to state management." If the board approved compatible regulations, Horn promised that "the [Interior] secretary will immediately issue the letter of approval and the responsibilities for implementing this program will remain firmly in the state. I guess I can't emphasize enough how much we wish we could do that...." He warned, however, that unless the board issued "some form of a regulation or law that establishes the [rural] priority in a proper fashion that conforms with the federal statute, we will shortly be forced to issue some kind of preliminary finding of noncompliance." If the department issued such a finding, the federal government might be forced to assume fish and wildlife management on Alaska's federal lands, "perhaps as soon as a month and a half from now," Horn added. [70]

Although Watt, in his letter, had noted that the state had some flexibility in responding to the three problem areas—"the State definition [of 'rural Alaska residents'] need not be identical to section 803," for example—many fish and game board members recognized that they had little latitude in complying with the federal government's dictum. Jim Rearden, a Game Board member from Homer, called it "blackmail," while joint boards chair Clint Buckmaster, from Sitka, noted that he was "sick to the core and the heart" over his decision. Some board members, along with many outside observers, used an analogy to poker; they concluded that the state should call the federal government's "bluff" and dare them to take over fish and wildlife management. ("The situation could hardly be worse than it is now," many felt.) Others, however, urged the joint boards to adopt the revised regulation. After three hours of deliberations, the boards voted 10 to 3 to comply with federal subsistence requirements. [71]

|

| Shown in this early-1980s photograph (left to right) are John Sandor (U.S. Forest Service), Keith Schreiner (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service), unidentified, Interior Secretary James Watt, Sen. Ted Stevens, Sen. Frank Murkowski, and Curt McVee (Bureau of Land Management). Watt, in May 1982, certified that the State of Alaska's subsistence program was in compliance with ANILCA provisions. NPS (AKSO) |

The joint board regulation, as decided on April 6, made no mention of what constituted a "rural" Alaskan, and neither the Alaska legislature nor the joint boards had specifically defined rural residency since the October 1978 passage of the state's subsistence law. But just a day later, the fish and game boards moved to conform with Section 804 of ANILCA by defining which areas were eligible to hunt and fish for subsistence purposes. It defined as rural (and therefore eligible for subsistence) those areas that were "outside of the road-connected area of a borough, municipality, or other community with a population of 7,000 or more, as determined by the Alaska Department of Community and Regional Affairs." Excluded were the residents of Anchorage along with the "road connected" portions of the state's most heavily-populated boroughs: Fairbanks North Star, Juneau, Kenai Peninsula, Ketchikan Gateway, Kodiak Island, Matanuska-Susitna, and Sitka. These areas, when combined, comprised only a small part of Alaska's land mass; populations levels outside of the road system, however, were so scattered that only 15 percent of the state's residents, according to this system, qualified as subsistence users. [72]

On April 29, 1982, Governor Hammond transmitted the final elements of the state's subsistence and use program to the Interior Secretary James Watt. On May 14, Watt responded by certifying to Hammond that the state's subsistence program "will be in compliance with sections 803, 804, and 805 of ANILCA as of June 2, 1982. As a result of this certification of compliance, the State retains its traditional role in the regulation of fish and wildlife resources on the public lands of Alaska." A mid-May press report noted that "Watt's action was a direct rebuff to those opposing a priority subsistence measure." [73]

One immediate response to the Interior Department's certification of the state's subsistence program—and the various late-winter meetings of the regional advisory councils—was that the federal government began to reimburse the state for certain costs related to subsistence management. Section 805(e) of ANILCA had stated that "The Secretary shall reimburse the State ... for reasonable costs relating to the establishment and operation of the regional advisory councils." Based on the fact that the state had organized various late-winter meetings of the regional advisory councils, as well as its fulfillment of the other federally-mandated aspects of its subsistence program, the federal government provided the state with a $960,000 reimbursement for Fiscal Year 1982. During the following funding cycle, reimbursements were increased to $1 million and remained at that level for the next several fiscal years. (See Table 5-3, following page.)

Table 5-3. State Subsistence Budgets and Federal Reimbursements, 1982-1990

| Fiscal Year |

Reimbursable State Subsistence Program Funds |

Federal Reimbursement |

Federal Contribution (Percent) |

| 1982 | $2,512,200 | $ 960,000 | 38.2 |

| 1983 | 2,957,000 | 1,000,000 | 33.8 |

| 1984 | 3,804,000 | 1,000,000 | 26.2 |

| 1985 | 4,367,800 | 1,000,000 | 22.8 |

| 1986 | 4,270,000 | 980,000 | 23.0 |

| 1987 | 3,324,800 | 932,000 | 28.0 |

| 1988 | 2,995,000 | 974,000 | 32.5 |

| 1989 | 2,600,000 | 974,000 | 37.5 |

| 1990 | 3,000,000+ | 750,000 | 25.0 |

Source: Section 806 and 813 reports; Richard Marshall and Larry Peterson, A Review of the Existing Alaska Department of Fish and Game Advisory System and a Determination of its Adequacy in Fulfilling the Secretary of the Interior's and the Secretary of Agriculture's Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act Title VIII Responsibilities (Anchorage, F&WS, June 1991), 7.

On August 23—more than three months after Watt certified the state's program—Interior Undersecretary Horn wrote to the regional directors of the various Alaska land management agencies and laid out guidelines on how the state's program would be monitored by federal officials. A key decision made in that letter was the designation of a single agency that would coordinate federal monitoring efforts. In that letter, Horn noted, "it has been determined that lead responsibility for the monitoring of fish and wildlife populations on all public lands will be vested in the Fish and Wildlife Service." [74] The F&WS's role as a centralizing agency for subsistence matters was initially quite small. A precedent had been set, however, and in early 1983 the Secretary designated the F&WS as the lead agency for the federal government's annual Section 806 (monitoring) reports. [75] Later that same year, the agency was asked to coordinate the Interior Department's review and response to the various Regional Council annual reports. [76] In future years, the F&WS would be called on to shoulder additional coordinating functions as federal managers assumed more subsistence responsibilities. [77]

During the six months that intervened between the Interior Secretary's program certification and the November 1982 election, Alaska voters were given ample opportunity to consider the legitimacy of the "Personal Consumption of Fish and Game" initiative (often called the Personal Use Initiative) which had been certified by the state elections division in March 1982. As noted on the ballot, the proposal

would, for fishing, hunting, or trapping for personal consumption, prevent classification of persons on the basis of economic status, land ownership, local residency, past use or dependence on the resource, or lack of alternative resources. It would, as does existing law, also bar classification by race or sex for any taking of fish or game. It repeals existing provisions of the Fish and Game Code which provide for, or relate to, subsistence hunting and fishing. [78]

The proposition would, in short, repeal all state-sponsored legislative and regulatory actions that, since 1978, had established a legal basis for subsistence in Alaska.

This initiative, which appeared on the ballot as Proposition 7, was favored by the Alaska Outdoor Council and a broad array of sport hunters and sport fishers, many of whom resided in urban areas. Organized under the ad hoc, Anchorage-based Alaskans for Equal Hunting and Fishing Rights or the Fairbanks-based Citizens for Equal Hunting and Fishing Rights, initiative backers stated that "Alaskans are not happy with the present discriminatory system in both state and federal law.... The present law has effectively repealed subsistence for 85% of Alaska's residents. [79] Passage of this initiative would restore the concept of equality in fish and wildlife resource allocation." They urged changes in both state and federal laws that related to subsistence. But many others, who formed under the umbrella group Alaskans for Sensible Fish and Game Management or Southeasterners Organized for Subsistence, liked the provisions of the 1978 law and wanted the keep the status quo. They warned that despite the obvious state's-rights orientation of Secretary Watt, passage of the initiative would bring an immediate federal takeover of fish and wildlife management. They argued, moreover, that ANILCA—the keystone of the state's subsistence management system—would be virtually impossible to change if the initiative was approved. Governor Hammond and all three members of Alaska's Congressional delegation urged Alaskans to reject the measure. [80]

After a tense, combative campaign, Alaskans cast their vote on the Personal Use Initiative on November 2, 1982. The initiative was decisively defeated, 111,770 to 79,679 (58.4% to 41.6%). The state-managed program—with its rural preference—appeared to be secure, at least for the foreseeable future. Outgoing Fish and Game Commissioner Ron Skoog, who supported the initiative, noted that the fish and game boards would be meeting in December and might choose to tinker with the definition of "rural" at that time. Skoog also felt that the "good, strong expression of public opinion" expressed by the initiative might spur the legislature into renewed action; and he also felt that William Sheffield, the newly-elected governor, might provide a new spark in the subsistence debate by appointing sympathetic members to the fish and game boards. [81]

Neither Sheffield nor the Thirteenth (1983-84) Alaska Legislature showed any particular inclination to meddle with the rural preference issue. [82] The joint fish and game boards, however, appeared unwilling to accept the status quo. At a March 24, 1983 meeting, the joint boards repealed the regulation defining rural residence (Alaska Administrative Code, Title 5, Section 99.020) that they had approved in April 1982. They took the action because the Alaska Attorney General, in a February 25 letter to Governor Sheffield, had determined that a definition of "rural" was not required by either state or federal law; the joint board's year-old definition, moreover, "posed equal protection and vagueness problems." [83] The Interior Department accepted that change. As a 1984 Interior Department report noted,

The Boards did not substitute another definition for this term. The rural resident requirement of section 803 is satisfied, however, by the "rural" provision of 5 AAC § 99.010(a)(2). [This section states that "subsistence uses are customary and traditional uses by rural Alaska residents."] It is also anticipated that the criteria of 5 AAC § 99.010(b)(1)-(8), which identify customary and traditional uses, will result in the application of the preference to rural residents, as required by sections 803 and 804. [84]

The joint boards' action thus removed specific geographical boundaries delineating rural from urban areas. Making those distinctions, in the future, would be a function of customary and traditional use determinations.

|

|

Map 5-2. State-Managed Subsistence Regions,

1982-1992.

(click on image for an

enlargement in a new window)

|

D. The NPS Organizes a Subsistence Program

|

| Roger Contor served as the NPS's regional director for Alaska from 1983 to 1985. NPS (AKSO) |

|

| Lou Waller, in his capacity as regional chief of the NPS's Subsistence Division, was a key player in subsistence decision making between 1984 and the mid-1990s. Lou Waller photo |

Although, as noted above, NPS officials (along with Interior Department solicitors) had been active in establishing management regulations for the various new and expanded national park units, the agency's only other major subsistence-related duty pertained to the establishment and operation of subsistence resource commissions (SRCs). [85] Section 808 of ANILCA had specified the formation of seven park or monument SRCs, whose members were to be appointed "within one year from the date of enactment of this Act:" in other words, by December 2, 1981. The Act stated that the Interior Secretary was responsible for appointing one-third of the SRC members, but the remaining members were appointed by either the Governor of Alaska or by the various state-managed regional advisory councils. On December 1—one day before the Congressional deadline—NPS representative Bob Belous appeared before a joint meeting of the Alaska fish and game boards to announce that his agency was having only limited success in establishing the various SRCs. Belous noted that the NPS, acting on behalf of the Interior Secretary, had selected its quota of seven SRC candidates. But the two non-Federal entities had failed to fulfill their part of the bargain. (Indeed, the six regional advisory councils that fulfilled ANILCA's requirements had not yet been established.) Belous, however, was not gloating. He noted, somewhat sheepishly, that the funding that had been requested to support the various SRCs had been recently stricken from the FY 1982 federal budget. Because of a budget stalemate, he admitted that it was "impossible to predict" if support funding would be restored any time soon. [86]

Budget problems for the agency in Alaska proved to be a long-term problem. Despite those difficulties, however, a full complement of 63 Alaskans had been chosen for the new SRCs within three months of Belous's presentation to the fish and game boards. As part of the state effort to gain federal approval for its activities relative to Title VIII of ANILCA, Governor Hammond appointed three members to each of the seven SRCs; and the newly-formed regional advisory councils, at their initial (February or March 1982) meetings, also appointed members to park and monument SRCs that were located in their regions. By the end of March, all nine members had been chosen for each of the seven SRCs, and by late May, ADF&G had passed on these names to NPS Regional Director John Cook. [87]

The NPS, meanwhile, was also active. The NPS, working with the Interior Department's Solicitor's Office, began preparing charters for the seven SRCs. In late April 1982, these charters were submitted for approval to Interior Secretary Watt, and on May 20, Acting Interior Secretary Donald Hodel approved all seven charters. The charters specified that they would be operating indefinitely; that members would be initially appointed for staggered terms (either one, two, or three-year terms) and for three-year terms thereafter; that the SRCs would meet twice per year, and that the Interior Department would spend $10,000 per year for their support. [88] Hodel sent the letter to NPS Director Russell E. Dickenson, who forwarded a copy to Morris Udall and James McClure. These two men chaired committees in the House and Senate, respectively, that oversaw Interior Department operations. [89]

Meanwhile, the NPS and the other federal land management agencies in Alaska had begun to work with Alaska fish and game officials on a workable Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). During the winter of 1981-1982, as noted above, the state and federal governments were slowly working out the conditions under which the Interior Secretary would certify the state's subsistence management program, and an MOU was intended to clarify the subsistence responsibilities of each state and federal agency. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was able to quickly arrive at mutually agreeable language with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, and on March 13, 1982—a full two months before Interior Secretary Watt certified the state's management program—ADF&G and F&WS signed their MOU. [90] Hopes were high that the NPS would sign its MOU with the state soon afterward—in April an Interior Department official stated that he was "currently negotiating" such an agreement—but the agreement was not signed by both parties until October 14. The MOU, in general, reiterated the fact that the subsistence management lay squarely in the state's hands; the state's management program, however, had to recognize NPS management guidelines and the Federal role as specified in ANILCA. The MOU listed a series of functions to which either the federal or the state agency was solely responsible, and it also listed a series of goals that were the mutual responsibility of both agencies. [91]

During the same week that NPS official John Cook and Fish and Game Commissioner Ron Skoog signed their MOU, the state and federal governments announced the appointment of the 63 initial SRC representatives. A month later, on November 4, their terms officially began; their terms would expire in November of either 1983, 1984, or 1985. The NPS hoped that the SRCs would quickly become active, but (as a 1984 letter tactfully explained it), there were "a series of procedural and administrative delays which have prevented the operation" of the various commissions. [92] Funding was the key sticking point; no funds were available to support the SRCs in either the 1982 or 1983 fiscal years.

As part of its oversight responsibility as outlined in Section 806 of ANILCA, the Interior Secretary (and his staff) in the summer of 1983 compiled an initial report that "monitor[ed] the provisions by the State of the subsistence preference set forth in section 804." That report, which was intended to be prepared "annually and at such other times as [the Secretary] deems necessary," was prepared for the relevant Senate and House committee as well as for the State of Alaska. In January 1984, the completed report was forwarded to the relevant committee chairs in the U.S. House and Senate. Twenty-seven pages long exclusive of attachments and staff comments, it chronicled the many efforts between state and federal officials to collaborate on a mutually-agreeable subsistence management plan. [93] This was the first of a series of Section 806 reports that would be prepared, in response to ANILCA's dictates, for the remainder of the decade.

During 1982 and 1983, the NPS underwent a number of staff changes that, in sum, had significant repercussions on how the agency managed its subsistence program. John Cook, who had overseen Alaska's subsistence program from the days that had immediately followed the national monument proclamations, left Alaska in March 1983, and during the same period several members of the freewheeling subsistence "brain trust"—including Bill Brown and Bob Belous—severed their ties with the agency's regional office operation. In May 1983, Cook was replaced by Roger J. Contor, a self-described conservative who was then serving as superintendent of Olympic National Park in Washington. [94] (Contor, as noted in Chapter 4, was no stranger to Alaska affairs; from 1977 to 1979, he had served as NPS Director William Whalen's point man for Alaska.) Contor, to a greater degree than Cook, felt that Alaska's park units could be managed much like those located elsewhere in the system. As Contor described it, he spent much of his tenure in Alaska "trying to preserve the integrity of the word 'park'." Based on the newly-protective Servicewide stance that Congress had adopted in the 1978 act that expanded Redwood National Park, Contor's philosophy was to limit activities within parks that were not specifically guaranteed by either ANILCA or subsequent regulations. [95]

In December 1983, the agency's subsistence program gained new momentum when Contor named Dr. Louis R. Waller to co-ordinate the Alaska subsistence effort. Waller, a ten-year Alaska veteran with the Bureau of Land Management, had worked in the bush (in McGrath) as well as in Anchorage. He assumed his new position in January 1984. [96] His appointment was a major step forward in organizing the agency's subsistence management efforts; although the agency had been responsible for subsistence matters since December 1980 (and to a lesser extent since December 1978), no one before Waller had worked full-time on problems related to subsistence coordination or management. (See Appendix 3.) Waller thereafter served as the primary point of contact for subsistence issues, although many of the agency's subsistence decisions were the joint product of discussions between Waller, Contor, and Associate Regional Director Michael Finley.

The long-awaited funding to operate the various subsistence resource commissions finally became available in December 1983, and soon afterward the agency took steps to make them active, operating entities. [97] In March 1984, Waller contacted the six superintendents of parks for which Congress had designated SRCs, [98] and arrangements were made to hold a series of introductory meetings. (See Table 5-4, following page.) The first such meeting was that of the Aniakchak SRC, held in King Salmon on April 18. These were followed, in quick succession by a combined meeting of the Cape Krusenstern, Gates of the Arctic, and Kobuk Valley SRCs in Kotzebue on May 3; of the Denali and Lake Clark SRCs, in Anchorage on May 10-11; and the Wrangell-St. Elias SRC, near Copper Center on May 15-16. Sufficient members of each commission except Aniakchak were present to constitute a quorum. [99] The various park superintendents (who were the designated commission management officers), along with subsistence coordinator Lou Waller, presided over these meetings and provided extensive background literature to each commission. A key agenda item was the selection of a chairperson (see Appendix 4); much of the remainder of the various meetings was devoted to a description and clarification of the various commissions' roles and functions. The various SRC members were told that one of their first responsibilities would be (as noted in Sec. 808(a) of ANILCA) to "devise and recommend to the Secretary and the Governor a program for subsistence hunting within the park or park monument." [100] (See Appendix 5.)

Table 5-4. Subsistence Resource Commission Chronology, 1977-present

Jan. 1977 — Initial version of H.R. 39 provided for "regulatory subsistence boards"

Oct. 1977 — Committee print of H.R. 39 proposes an "Alaska Subsistence Management Council" as well as for regional and local advisory committees

Oct. 1978 — Senate Committee version of H.R. 39 first proposes park and monument subsistence resource commissions

1979-80 — House-passed version of H.R. 39 (May 1979) provides for regional and local subsistence advisory committees (but not SRCs), but Senate-passed version (August 1980) includes an SRC provision.

Dec. 1980 — Senate bill becomes law.

1981-82 — Initial SRC members selected, but commissions remain inactive due to lack of startup funding

April 1984 — Initial SRC meeting was for the Aniakchak SRC, in King Salmon. Remaining SRCs held their introductory meetings a month later.

Nov. 1985 — Initial SRC Chairs meeting, in Anchorage. Subsequent meetings held in Nov. 1988 (Fairbanks) and Dec. 1989 (Anchorage)

1986-87 — Initial hunting plan recommendations submitted to the Interior Secretary

1988 — The Interior Secretary responds to the initial recommendations.

1994 — Initial SRCs began submitting game management recommendations to RACs; by 1996 this was a regularly-accepted, if informal, practice

June 1996 — Resumption of SRC Chairs meeting, annual meetings held thereafter

Nov. 1998 — SRCs given authority to submit some recommendations to NPS's Regional Director instead of to Interior Secretary

March 2002 — First SRC non-game Hunting Plan recommendations become federal regulations

Waller, during this period, also worked with the Alaska Game Board in order to inform the board—and Alaska's hunters—about NPS hunting policies in the various park units established by ANILCA. In 1983, the agency had been pleased when the board revised its widely-distributed hunting regulations booklet to reflect the prohibition of sport hunting in the various parks and monuments. In March 1984, however, it became concerned with several proposals that the board was considering for land in and around Gates of the Arctic National Park. The agency questioned, for example, the need to change a regulation that had not been requested by local residents; it was concerned that the boundary of a proposed bull moose hunting regulation was a national park unit boundary and not a game management unit boundary; it was perplexed that brown bear proposals were being considered that did not match well-defined traditional use patterns; and it was alarmed at proposed wolf control programs that might affect wolf populations within the national parks. [101]

Despite the NPS's arguments to the contrary, the Board of Game, at its March 1984 meeting, implemented the regulations that pertained to the Gates of the Arctic area. The agency, however, refused to sit idly by. On August 22, Regional Director Roger Contor wrote the game board a detailed letter that bemoaned a "problem with communications" between the two bodies. He reminded the board, moreover, that the State-Federal Memorandum of Understanding, signed in October 1982, required "timely consultation, coordination of resource planning," and a pledge "to resolve management differences between the [ADF&G] and the Service before expressing a position in public." Contor broadly hinted that the state had sidestepped the MOU in its Gates of the Arctic proposals; he then briefly outlined several of the NPS's primary management tenets and described why the proposed regulations clashed with them. He specifically noted that a "natural and healthy" management mandate in the parks and monuments (as specified in ANILCA) often diverged from the state's mandate for "sustained yield" management, and he criticized that board for not paying heed to the "where traditional" clause as elaborated upon in the legislative history. He then reiterated some of the specific concerns that the agency had expressed in its March letter. [102]

|

| In 1983 or 1984, key NPS personnel met for a superintendents' conference at Glacier Bay Lodge. Top row, left to right: Mike Finley (ARO), Jim Berens (ARO), Dave Mihalic (YUCH), Dave Morris (KATM). Second row: Robert Cunningham (DENA), Mack Shaver (NWAK), Bill Welch (ARO). Third row: Ernie Suazo (SITK), Dick Sims (KLGO), Dave Moore (KEFJ), Larry Rose (BELA), Bob Peterson (ARO). Fourth row: Mr. & Mrs. Roger Contor (ARO), Mike Tollefson (GLBA), Paul Haertel (LACL). Bottom row: Mrs. Finley, unidentified, Mrs. Welch, Mrs. Ring (holding infant), Chuck Budge (WRST). NPS (AKSO) |

In response to Contor's missive, Alaska Fish and Game Commissioner Don Collinsworth wrote an equally detailed letter, responding to Contor point by point. He, like Contor, quoted extensively from ANILCA's legislative history. Collinsworth recommended, "as a courtesy to the National Park Service," that the Board of Game reconsider two of its three previous proposals. And to avoid such conflict in the future, he laid out a four-step process by which the two agencies would be kept informed of potential changes in the hunting regulations for areas within the NPS's purview. [103]