|

National Park Service

MISSION 66 VISITOR CENTERS The History of a Building Type |

|

INTRODUCTION

The Origins of Mission 66

In 1949, Newton Drury, director of the National Park Service, described the parks as "victims of the war." [1] Neglected since the New Deal era improvements of the 1930s, the national parks were in desperate need of funds for basic maintenance, not to mention protection from an increasing number of visitors. Between 1931 and 1948, total visits to the national park system jumped from about 3,500,000 to almost 30,000,000, but park facilities remained essentially as they were before the war. Without immediate improvements, the parks risked losing the "nature" that attracted people to them. Already, the floor of Yosemite Valley had become a parking lot littered with cars, tents, and refuse. Brilliant Pool, a popular thermal feature at Yellowstone, looked like a trash pit. Drury realized that new, modern facilities could help conserve park land by limiting public impact on fragile natural areas. But the necessary improvements required significantly larger appropriations from Congress. Throughout his tenure, Drury remained unable to obtain the necessary federal support for his program. [2]

As Drury worried about "the dilemma of our parks," and basic methods of sustaining them, he also participated in planning a major architectural event: the competition for the design of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial in St. Louis. Conceived during Franklin Delano Roosevelt's administration, the memorial project lagged during World War II, but in 1945 the idea was revived and with it the added incentive of providing a symbol of national recovery. The advisor for the design competition, George Howe, was known for his collaboration with William Lescaze on the Philadelphia Saving Fund Society (PSFS) building in Philadelphia, the skyscraper that brought the International Style to mainstream America in 1932. The competition attracted national media attention and submissions from one hundred and seventy-two architects, including Eliel Saarinen, The Architect's Collaborative (founded by Walter Gropius), and sculptor Isamu Noguchi. [3] Fiske Kimball, William Wurster, and Richard Neutra were among the judges who unanimously awarded first prize to the design of Eliel's son, Eero Saarinen. The 630-foot stainless steel arch was a monument to westward expansion, an engineering feat and an icon of modernist architecture. The conception, design, and construction of the gateway extended from the New Deal (the era of Park Service Rustic) to Mission 66, the ten-year park development program founded in 1956. Bolstered by a decade of congressional funding, the Mission 66 program would result in the construction of countless roads and trail systems and thousands of residential, maintenance, and administrative facilities, as well as the beginning of new methods for managing and conserving resources. When the arch was finally dedicated in 1968, Mission 66 had left a legacy of modern architecture in the national parks. [4]

Authorization for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial was still pending in 1951, the year Conrad Wirth took over as director of the Park Service. Even more pressing problems of funding for new construction and facility maintenance remained unsolved. Over the next few years, the conditions Drury had described in 1949 would become a subject of public concern, not to mention ridicule. Social critic Bernard DeVoto led the crusade for park improvement with an article in his Harper's column, "The Easy Chair," entitled "Let's Close the National Parks," which suggested keeping the parks from the public until funds could be found to maintain them properly. [5] The story caught the attention of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., a longtime park patron, who wrote to President Eisenhower of his concern over this potential "national tragedy." Eisenhower's staff responded with a standard apology, but Rockefeller's letter did cause the President to request a briefing from Secretary of the Interior Douglas McKay on conditions in the parks. [6] As the need for massive "renovation" of the Park Service entered the public forum and reached the President's desk, the Park Service's pressing maintenance problems continued to mount. [7]

During the summer of 1954, Department of the Interior Undersecretary Ralph Tudor began a reorganization of his department that would indirectly result in the Mission 66 program. The leadership hierarchy of each bureau was "realigned" and a Technical Review Section established to coordinate the agencies. This procedure included a board of businessmen that examined Park Service policies in the hope of streamlining the bureaucracy. Issues of western mineral and water rights were of particular concern at the time because of the controversy surrounding the proposed construction of the Echo Park Dam at Dinosaur National Monument. Horace M. Albright, former director of the Park Service, served on an advisory committee for mineral resources. According to historian Elmo Richardson, the reorganization allowed Conrad Wirth to focus attention on the crisis in the Park Service, and its history of "subjective and procedural problems." Once the door was open, Wirth had a captive audience for his improvement program. [8]

Director Wirth's recollection of the birth of Mission 66 is fittingly more dramatic. In Parks, Politics and the People, Wirth remembers one "weekend in February, 1955," when he conceived of a comprehensive program to launch the Park Service into the modern age. [9] The brainstorm occurred once Wirth envisioned the Park Service's dilemma through the eyes of a congressman. Rather than submit a yearly budget, as in the past, he would ask for an entire decade of funding, thereby ensuring money for building projects that might last many years. Congressmen who wanted real improvements for the parks in their districts would support increased appropriations for the entire construction period. Armed with a secure budget, the program would generate public support through its missionary status and implied celebration of the Park Service's golden anniversary in 1966. Mission 66 would allow the Park Service to repair and build roads, bridges and trails, hire additional employees, construct new facilities ranging from campsites to administration buildings, improve employee housing, and obtain land for future parks. This effort would require more than 670 million dollars over the next decade. From its birth, Mission 66 was touted as a program to elevate the parks to modern standards of comfort and efficiency, as well as an attempt to conserve natural resources. Wirth immediately organized two committees to work on the Mission 66 program, a steering committee and a Mission 66 committee, with representatives from several branches of the Park Service, many of whom were to devote themselves full-time to the project. Lemuel Garrison put aside his new appointment as chief of conservation and protection to act as chairman of the steering committee. In his memoirs, Garrison captures the energy behind the mission and its fearless confrontation of park problems; each superintendent was asked to write a list of "everything needed to put 'his' park facilities into immediate condition for managing the current visitor load, while protecting the park itself." [10] They were also to estimate the number of visitors ten years in the future. During this early planning stage, the Mission 66 staff reviewed the history of Park Service development policy and began a pilot study of Mount Rainier National Park, Washington, chosen as typical of parks with a range of problems. From this study, the Mission 66 staff derived a list of priorities for determining park needs, which would also assist the superintendents in their assessments. One result of the project was the creation of park standards throughout the system. Each park was to have a uniform entrance marker listing park resources, a minimum number of employees, paved trails to popular points of interest, and other amenities; visitors could expect the same basic facilities in every park. The Mount Rainier study also led to seven additional pilot studies, a sampling of parks of various types throughout the country. [11]

Figure 1. Mission 66 Committee, 1956 (left to right: Howard Stagner, naturalist; Bob Coates, economist; Jack Dodd, forester; Bill Carnes, landscape architect; Harold Smith, fiscal; Roy Appleman, historian; Ray Freeman, landscape architect). (Courtesy National Park Service Historic Photograph Collections, Harpers Ferry Center.) |

During the course of its research, the planning staff benefited from public and personnel interviews and more general information from a national survey. In April 1955, private funding was obtained for "A Survey of the Public Concerning the National Parks." Audience Research, Inc., polled a national sample of 1,754 American adults to determine the level of knowledge about parks and park-related concerns. Although results indicate an appalling lack of education—twenty-two percent couldn't name a single park—they also confirmed the continued rapid increase in visitation and the general dissatisfaction of those who had made park visits. Over two-thirds of the visitors voiced complaints, the most common of which were overcrowding and the need for overnight accommodations. Of those visitors with suggestions for improvement, eighteen percent desired "more information about the sights to be seen, plaques, printed material, guide maps, lectures, etc." This response, second only to "more facilities for sleeping," demonstrated the public desire for the kinds of interpretive services gathered together in future visitor centers. [12]

Figure 2. Conrad Wirth, second from left, sampling bison and elk meat at the American Pioneer Dinner, 1956. Undersecretary Clarence Davis is on the left and Mrs. Singer and Russell Singer, ex-vice president of the American Automobile Association, are on the right. Photograph by Abbie Rowe. (Courtesy National Park Service Historic Photograph Collections, Harpers Ferry Center.) |

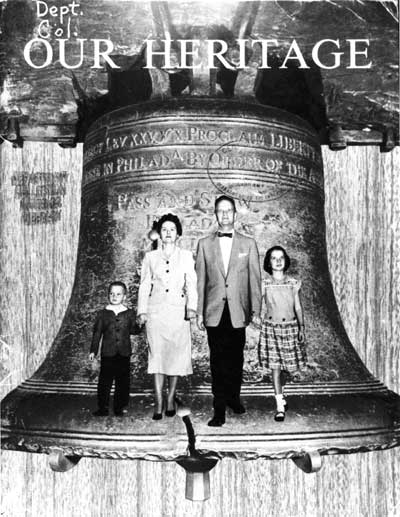

By necessity, Wirth's preliminary planning of the Mission 66 program was geared towards promotion, and, in particular, selling his idea to Congress. Along with the pilot studies, the staff was to produce a basic outline of the program for the Public Service Conference at Great Smoky Mountains on September 18, 1955. Since a future meeting with the President had been confirmed in May, Wirth hoped to reserve "Mission 66" until then, but news of the program leaked out after the conference. In anticipation of the congressional meeting, the staff began work on a promotional booklet and final report. [13] After several dry runs and administrative delays, Wirth introduced Mission 66 to the President and his cabinet on January 27, 1956. The program received immediate approval from the President. The necessary documents for final authorization were signed in early February, and Mission 66 was officially introduced to the public at an American Pioneer Dinner held at the Department of the Interior on February 8th. Highlights of this event included a presentation by Wirth, a Walt Disney movie entitled "Adventure in the National Parks," and the circulation of Our Heritage, a promotional booklet. Wirth himself was involved in the minute details of his carefully orchestrated marketing campaign. He personally chose the cover for Our Heritage—the Riley family of Williamsburg, Virginia, superimposed over a photograph of the liberty bell. The Rileys represented the ideal American family, the most desirable park visitors. Having achieved its immediate goals, the Mission 66 organizational staff was disbanded that month. A core group of the original members remained to help direct the ongoing program. [14]

Figure 3. Our Heritage, brochure cover, National Park Service, 1955. |

Modern Architecture in America

Although the foundations of the modern movement in architecture were laid in the mid-nineteenth century, the "new tradition" did not reach mainstream America until the late 1920s. Henry-Russell Hitchcock wrote about this phenomena in Modern Architecture (1929), and in 1932 introduced the International Style to New York in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. In their attempt to come to terms with recent innovations in architectural design, Hitchcock and his collaborator, Philip Johnson, described buildings like the PSFS skyscraper and Richard Neutra's Lovell House as examples of an "International Style." The primary characteristics of the style—emphasis on volume, regular organization of plan, and absence of applied ornament—represented a revolution in architectural design, according to the curators. Traditional methods of craftsmanship were replaced by more efficient methods of machine production. Over twenty years earlier, such founding fathers of the modern movement as Adolf Loos, Peter Behrens, and FrankLloyd Wright preached that acceptance of this "machine aesthetic" freed architects from restraining conventions and would ultimately lead to a truly modern architecture. [15]

Hitchcock and Johnson traced the popularization of the International Style to the work of Swiss architect Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier (1887-1965). Le Corbusier began his career in the office of Auguste Perret, worked briefly for Berhens and Josef Hoffman, and founded the Purism branch of cubist painting with the French painter Amedee Ozenfant. By lifting residential spaces off the ground with thin columns, spiraling ramps, and terraces, Le Corbusier transformed the traditional parlor into an open space full of light and air. His houses not only accommodated automobiles and adopted the aesthetics of ocean liners, but were themselves "machines for living in." If Le Corbusier's villas of the 1920s exemplified the International Style, his writings on architecture brought the new movement into a public forum. Le Corbusier spread his architectural gospel in his own periodical, L'Esprit Nouveau, and through a few simple manifestos, beginning with Vers une architecture in 1923. Three years later, he described the "five points of architecture," a list of qualities essential to the new architecture. The basic elements—columns, roof terraces, free plans, strip windows, and free facades—would not have seemed so revolutionary were it not for Le Corbusier's passionate desire to cure social ills through design. Although his buildings never gained much popularity in the United States, Le Corbusier's philosophy exerted a profound influence over the development of American modernism. Even in the 1950s and 1960s, a watered-down form of the five points was visible in the design of modernist buildings.

The International Style exhibition also introduced Americans to the work of Walter Gropius, the German architect and founder of an innovative school of architecture and design. Established in Weimar in 1919, Gropius' Bauhaus taught a total approach to design that encouraged the collaboration of artists from different disciplines. Architects not only worked with furniture makers, sculptors, and painters in the design of buildings, but also mastered traditional crafts such as woodworking, weaving, and bookbinding. Practical training in workshops enabled students to apply the knowledge of generations to modern conditions. This experimental, team-oriented design philosophy created political divisions in the school, and in 1925 it moved to Dessau for a fresh start. Gropius' new glass and plaster Bauhaus building adapted characteristics of the modern factory, the imitation of which had come to suggest productivity and technological power. As a school, the Bauhaus generated publicity for the modern movement as well as for the collaborative method of architectural design. It also gave American architects a glimpse of "the new architecture" in an institutional building, as opposed to a private home.

Although not considered a proponent of the International Style, FrankLloyd Wright was responsible for some of the most innovative housing of the century, beginning with his own Oak Park home and studio in 1889. The 1910-1911 publication of his work by the Berlin firm Wasmuth immediately attracted the attention of the elite European design world. Among Wright's admirers were two young Viennese architects—Rudolph Schindler and Richard J. Neutra—inspired by his drawings to seek modern architecture in America. Schindler set out for Chicago in 1914, and eventually Neutra followed him to Los Angeles, where they both hoped to find an audience for their work. They brought with them background in European modernism and experience in the offices of such pioneers as Adolf Loos and Erich Mendelsohn. Not only would they transform Southern California, but, with Wright, forever alter the future of American architecture.

Wright's Prairie Style houses hunkered down in the landscape and expressed a patriotic esteem for natural beauty, while Neutra's Lovell House (1927-1929) exposed a pristine white surface and flexed athletic cantilevers. Modernism in America would borrow from both. Wright attempted to create houses that blended with their environment through aesthetic means, but also recalled national values. The center of a Wright house was a hearth typically created of local stones and symbolic of domestic stability. In contrast, Neutra's residential architecture represented American individuality through aesthetic and technological freedom. The houses were free of restraining conventions; walls disappeared and windows opened up to the outdoors. The Neutra house symbolized American progress through efficiency, both of material and of plan. In his Wie Baut Amerika? (1927), Neutra used photographs of Chicago skyscraper construction to illustrate how innovation in engineering might influence architectural design. Whereas Wright searched for natural associations, Neutra buildings made "no naturalistic concessions to their surroundings." [16]

Despite all their differences, Wright and Neutra shared a design aesthetic perhaps best illustrated by their respective residential designs for Edgar J. Kaufmann. Wright's famous "Fallingwater" in Bear Run, Pennsylvania, was designed for Kaufmann in 1936; eleven years later, Neutra designed the Kaufmann residence in Palm Springs, California. Upon first examination the two houses, developed for two entirely different climates and locations, appear to have little in common. Fallingwater is a mass of solid masonry and concrete planes built up over a natural waterfall. The Kaufmann residence is practically translucent with glass window walls opening up the living quarters to the Southern California sun. Nevertheless, both houses use horizontal planes and stone masonry to create a connection with the landscape. Although Wright employs a series of terraces and Neutra focuses on a single plane, the buildings share a floating quality, a characteristic of modern architecture facilitated by structural innovation.

If Wright, Neutra, and the Europeans introduced in the Museum of Modern Art exhibit provided models for future buildings, the New Deal and the second world war acted as catalysts for a full-fledged modern movement in America. New Deal planning—the government's desperate effort to recover from depression—turned methods of federal administration upside down, creating an atmosphere more accepting of innovation. Although the war was detrimental to construction in America, it caused the immigration of many prominent European architects fluent in International Style theory and practice. Some of the most influential of these architects established themselves in American universities. Mies van der Rohe became the head of architecture at Armour Institute, the future Illinois Institute of Technology. Laszlo Moholy-Nagy founded the New Bauhaus in Chicago in 1937, the same year Gropius and Marcel Breuer brought Bauhaus philosophy to Harvard University. As chairman of the architecture department, Gropius taught the value of collaborating on design problems, a method he practiced through his firm, The Architects Collaborative.

During the Depression, the Public Works Administration hired modernist architects to design housing for industrial workers, setting a stylistic precedent for subsidized federal building programs. Among the first such examples of efficient, multi-unit housing was the Carl Mackley Homes in Philadelphia, an International Style complex designed by the German immigrant Oscar Stonorov. During World War II, the government once again turned to modernist architects to solve its housing problems. Stonorov was called on to design several projects in 1941-1942, including Audubon Village in Camden, New Jersey, and Pennypack Woods in Philadelphia. At the same time, Neutra was working with other prominent architects on the design for Avion Village in Grand Prairie, Texas. This project was followed by another government commission, a community development for shipyard workers in San Pedro, California, called Channel Heights. Gropius and Breuer's housing for ALCOA employees in New Kensington, Pennsylvania, initially mocked as "chicken coops," proved to be a remarkably efficient solution to the problem of inexpensive housing and limited space. These flat-roofed buildings were not considered aesthetically pleasing at the time, but their streamlined shape and strip windows would become ubiquitous during the 1950s and 1960s. [17]

The most obvious architectural indications of recovery from World War II were the skyscrapers that began to populate American cities in the early fifties. Lever House, designed by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM) in 1951, set the standard for the modern office building, complete with street-level plaza. In Manhattan, the Seagram Building by Mies, Johnson, Kahn and Jacobs presented a shimmering steel skeleton articulated by bronze projecting I-beams. The excess and innovation of the 1950s and 1960s resulted, in part, from aggressive methods of commercial development in the nation's largest cities. Under the auspices of urban renewal, countless downtowns were gutted by freeways. New government complexes replaced tenement housing. Highrise apartments were substituted for entire neighborhoods. Cities were re-zoned for commercial use and residential communities established on their outskirts. The emergence of such modern housing and zoning efforts is demonstrated by an urban renewal project on the edge of Los Angeles. Richard Neutra and Robert Alexander began their partnership with a design intended to transform the Mexican-American "slum" known as Chavez Ravine into high-density housing. The thriving state of the neighborhood was hardly noticed, especially since planners described the need for additional housing close to the spreading city. Only after Ravine residents were forced to clear out in preparation for development did local politicians put an end to the project. Their 1953 decision did not reflect an enlightened view of the area's value, but rather a growing fear of communism represented by government-sponsored public housing projects. [18]

The early fifties were a time of great change in American cities and in cultural attitudes toward the family, patriotism, and technology. As Mission 66 planners prepared for a decade of development in the parks, skyscrapers and high-density housing replaced historic buildings and familiar neighborhoods. For the majority of the population in positions of political power, downtown highrises and business centers anticipated a better, more efficient lifestyle for all Americans. The forces at work—capitalism and a society obsessed with progress—were prevalent throughout the country; it was only a matter of time before they would enter the national parks. [19]

Modern Architecture in the Parks

Mission 66 reached the drawing boards in the mid-1950s, when park architecture included late Victorian lodges constructed by private concessioners, rustic architecture designed by the Park Service in the 1920s and 1930s, and temporary facilities erected to accommodate visitors during wartime, but often still in use. The Park Service Rustic style developed in the 1920s emphasized natural materials and associations with the surrounding landscape; eventually "rustic" became a label for any building erected by the Park Service that met this criteria, whether by imitating an adobe presidio or an alpine retreat. Such rustic construction demanded the labor of both skilled and unskilled craftsmen, and, during the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) provided the cheap manpower that allowed for such painstaking construction at low cost. Visitors and park personnel came to expect well-groomed trails, amenities like stone drinking fountains and steps, trailside museums, and other architectural features which appeared part of the natural landscape.

The prospect of modern architecture in the national parks shocked those not imbued with its progressive attitudes, inspired with its missionary zeal, or knowledgeable about its origins. News of modern architectural development immediately provoked an outcry from environmentalists and nostalgic visitors. One of the most outspoken critics of the new style was Devereux Butcher of the National Parks Association. As early as 1952, Butcher wrote of his horror at finding contemporary buildings in Great Smoky Mountains and Everglades and criticized the Park Service for abandoning its "long-established policy of designing buildings that harmonize with their environment and with existing styles." Among the eyesores he discovered were a curio store with "blazing red roof and hideous design," a residence "ugly beyond words to describe," and a utility building that might as well have been a factory. Later in the decade, David Brower and Ansel Adams joined Butcher in condemning such park development, although these critics focused more on issues of resource conservation than architectural style. [20]

Despite the criticism of Butcher and others, the Park Service felt it had remained consistent with its tradition of architectural design in harmony with the surrounding landscape. In fact, the design methodology behind the use of rustic architecture was adapted to explain contemporary design decisions. According to Director Wirth, Mission 66 buildings were intended to blend into the landscape, but through their plainness rather than by identification with natural features. Even the qualities that defined rustic architecture—local boulders, rough beams, etc.—might draw attention to a building created to serve a practical function. [21] As if to illustrate this fact, the Park Service refused to approve a restaurant designed by Frank Lloyd Wright for the concessioner at Yosemite Valley in 1954. Wirth called the building ". . . a mushroom-dome type of thing. A thing to see, instead of being for service." [22] The Park Service communicated this architectural philosophy in its early promotional literature, as well as in its relations with the national media. In August 1956, Architectural Record reported that Mission 66 would produce "simple contemporary buildings that perform their assigned function and respect their environment." [23] The magazine also emphasized that while this policy had traditionally led to the use of stone and redwood, "preliminary designs for the newer buildings show a trend toward more liberal use of steel and glass." One example of this trend was Dinosaur National Monument's Quarry Visitor Center, the much-acclaimed modernist facility designed by Anshen and Allen, Architects, of San Francisco. Two years after the rejection of Wright's "mushroom," the Park Service approved a modernist visitor center with a steel and glass exhibit area that made it "a thing to see." A decade later, at the conclusion of Mission 66, the Park Service would celebrate the dedication of the Headquarters at Rocky Mountain, designed by Taliesin Associated Architects, Ltd., the firm that evolved from the office Wright established in Scottsdale, Arizona, in 1938.

The contradiction between Park Service design philosophy and practice frustrated environmentalists, who were quick to point out the ironies unfolding before them and to criticize the Mission 66 program as heading toward excessive and unnecessary development. Within the Park Service, architects appear to have embraced the opportunity to modernize facilities and experiment with new design concepts. For example, Cecil Doty, a leading Park Service architect at the Western Office of Design and Construction (WODC) in San Francisco had designed the rustic Santa Fe Headquarters building in 1937. By the early 1950s, however, he recalled "a change in philosophy. . . . That's why you started seeing [concrete] block in a lot of things. We couldn't help but change. . . . I can't understand how anyone could think otherwise, how it could keep from changing." [24] Doty's statement provides a key to understanding the legacy of Mission 66 architecture, the purpose of which was not to design buildings for atmosphere, whimsy or aesthetic pleasure, but for change: to meet the demands of an estimated eighty million visitors by 1966, to anticipate the requirements of modern transportation, and to exercise the potential of new construction technology. As Director Wirth explained, the Park Service not only had to serve greater numbers of visitors, but to understand their increased need for appropriate facilities. The pressures of the modern condition"the stress and restless activity of this machine age, when man is sending satellites spinning into orbit around the sun and our own earth"—required more frequent renewal in "the peace and solitude offered by nature." [25] Even critics agreed that some kind of action was necessary to bring the parks up to contemporary standards; for Park Service personnel, Mission 66 offered hope for the future of the system.

Mission 66 promoters and pioneers of the modern movement shared a belief in the power of architecture to change behavior; the language used to describe the program mirrored that of Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe. Wirth told his steering committee to be "as objective as possible. Each was to be free to question anything if he thought a better way could be found. Nothing was to be sacred except the ultimate purpose to be served. Man, methods, and time-honored practices were to be accorded no vested deference." [26] This need to abandon the past and rely on new approaches—the modernist philosophy in a nutshell—reflected the plight of a society recovering from depression and war. During the 1950s, America looked to the modern movement for answers to social and economic questions, and it seemed to offer answers: buildings could not only house the indigent, but help them to conform to middleclass ideals; ergonomic office towers would produce more efficient workers. The utopian idea that improvements in the built environment might transform society dated back to antiquity, but the technology available to seek that transformation was new, and it inspired a generation of modern architects. A writer for Architectural Record expressed this sense of limitless potential for park architecture in 1957:

Let us not decide, just because we cannot draw it on the back of an envelope, that the great and sympathetic architecture cannot exist. I shall have to insist that the effort to achieve or acquire great architecture has almost never been tried. The whole habit of thinking in the parks is the other way. We have not dared to let man design in the parks; we have not asked to see what he might do. We have slapped his hand and told him not to try anything. [27]

Modern architecture expressed progress, efficiency, health, and innovation—values the Park Service hoped to embody over the next decade.

Figure 4. Grist cover, National Park Service, September-October, 1957. |

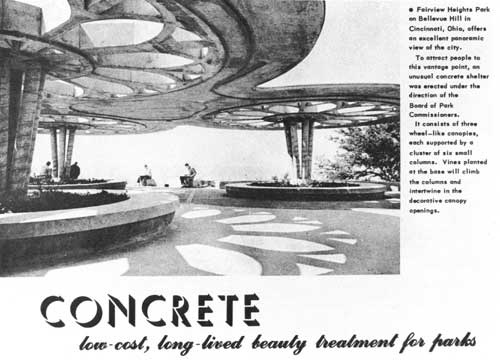

The social acceptance of modernism and its use in the parks was also a matter of urgency and economics. The Park Service needed to serve huge numbers of people as quickly as possible, and, despite increased funding, it had to do so on a limited budget. The materials that modern buildings were composed of—inexpensive steel, concrete, and glass—allowed more facilities to be built for more parks. In its publication Grist, the Park Service praised concrete as "low-cost, long-lived beauty treatment for parks." Asphalt was "nature's own product for nature's preserves," and asbestos-cement products "building materials for beauty, economy, permanence." [28] The use of such materials was obviously loaded with cultural significance; concrete was certainly not new, and even the reinforced variety dated back to 1859. It was the appearance of mass production, a condition implying that a standard for human comfort had been attained, that appealed to followers of the modern movement. In the 1950s and 1960s, American society not only embraced modern materials and the ideals they represented, but became aware of the Park Service's interest in such advances. The Reynolds Metals Company invited Director Wirth to a meeting about progress in aluminum engineering. Wirth attended the event and acquired a copy of the book sponsored by the company, a survey of modernist architecture and interviews with important modern architects. [29]

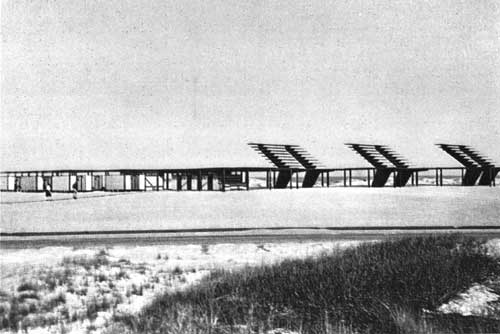

Despite the general acceptance of modernism, Americans were still unfamiliar with modern architecture in national parks. The success of the Mission 66 program depended, in large part, on a tremendous public relations campaign. The program was promoted with press releases notifying newspapers of ground breakings, building dedications, and other indications of progress; signs identifying its projects; and various community events focusing on public education. Newspaper coverage of early Mission 66 projects describes the shock of the modern style in places the public expected "wilderness" and history. When The New York Times reported on the controversy surrounding Gilbert Stanley Underwood's Jackson Lake Lodge, the reporter emphasized the contrast between the new concrete building and the area's wild west tradition, noting that "sheepmen," "naturalists," and "gamblers" "now heatedly discuss the pros and cons of modern architecture." Nevertheless, the Times clearly admired "the artful blend of comfortable modern with western" even as critics called it "a slab sided concrete abomination." The Virginian Pilot was more conservative in its coverage of the "modern trend in architectural ideas" exhibited in the shade structures at Coquina Beach, Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Although Donald F. Benson, a Park Service architect at the Eastern Office of Design and Construction (EODC) received a Progressive Architecture award citation for the design, the paper warned that, "until people get used to the modern trend," the new shelters would "cause as much comment as three nude men on a Republican Convention Program." [30] The Coquina facilities, destroyed by a storm in the early 1990s, soon became among the most widely praised designs of the Mission 66 era. [31]

Figure 5. Jackson Lake Lodge, Grand Teton National Park, Moose, Wyoming. n.d. Photograph by Jackson Hole Preserve, New York. (Courtesy National Park Service Historic Photograph Collections, Harpers Ferry Center.) |

Figure 6. Coquina Beach shelter, Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, as pictured in an undated postcard from the collection of Donald Benson. |

If modern architecture seemed out of place in certain settings, it was rapidly becoming familiar in both suburbs and cities. By the 1950s, the new tradition in architecture had stood the test of time, and the revolutionary designs of its founders were adapted and incorporated into mainstream American culture. For models of design, then, the youthful generation of Park Service architects and planners looked not to their old-fashioned predecessors in the parks, but to the work of such geniuses of modernism as Breuer, Neutra, and Eero Saarinen. But if Park Service designers could be conservative in their choice of modernism, they must also have been aware of dissension in the ranks of the architectural elite. A 1961 symposium on the state of national architecture brought a panel of influential practitioners together to discuss the current "period of chaoticism." All agreed that the promise of the new tradition had not been fulfilled; confusion and a depressing aimlessness prevailed. Amid this frustration, a glimmer of optimism called The Philadelphia School offered some direction. This group of young architects admired the buildings of Louis Kahn as well as the philosophy underlying his work. Kahn and his Philadelphia School rejected the traditional tenets of stripped-down modernism, seeking instead the spiritual side of design. Prominent members of this loosely associated group included Robert Venturi, Robert Geddes, and the firm of Mitchell, Cunningham, Giurgola, Associates (later known as Mitchell/Giurgola, Architects). [32]

The Park Service accepted modernism at a time when the new tradition had aged, and its post-modern backlash not yet emerged. The visitor center designed by Mitchell/Giurgola for the Wright Brothers Memorial was featured in a "news report" in Progressive Architecture suggesting that the Park Service had finally caught up with the standard required by the modern visitor. "The design of visitors' facilities provided for national tourist attractions seems to be decidedly on the upgrade, at least as far as the work for National Park Service is concerned. Disappearing one hopes, are the rustic-rock snuggery and giant-size "log cabin" previously favored." [33] That the progressive periodical chose two visitor centers to "exemplify new park architecture" was not surprising. The Park Service intended for the new visitor center buildings to represent the values and results of its system-wide development campaign. Whether or not the Park Service knew it was embracing a new strain of modernism is unclear.

Modernist architecture and planning approached the gates of the nation's capitol in 1965, when the Park Service collaborated on the Pennsylvania Avenue Historic District inspired by President Kennedy. During his inaugural parade, the President commented on the unsightly appearance of Pennsylvania Avenue, and it fell to Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall to instigate improvements. Udall consulted with Nat Owings, principal of SOM, the nationally famous architectural firm known for its major planning projects and modern office buildings. [34] For the area bounded by the Capitol and the White House, Owings "contemplated a totally new creation along Pennsylvania Avenue . . . we'd tear down everything there and build a monumental national avenue framed with totally new monumental structures." [35] In an effort to generate funds for the scheme, the Park Service conducted an historical study of the area and ultimately declared it an historic site in 1965. The growing consciousness of the importance of historic preservation, which culminated in the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, helped to save potentially endangered historic buildings within the district, such as the Willard Hotel. Ironically, the Park Service's own policy towards historic areas compromised the modernist redevelopment plan. One result of the Mission 66 program was the realization that historic buildings and districts required federal protection. [36]

A New Building Type

Even before the commencement of the Mission 66 building program, its public relations campaign addressed important issues in the design of a new type of visitor facility—the visitor center. The cover of the September "Mission 66 Report" depicts the national park system as a scale balancing protection and use, a balance the centralized visitor center was intended to achieve, at least in principle, through the management of visitor circulation. Our Heritage described the visitor center as "one of the most pressing needs, and one of the most useful facilities for helping the visitor to see the park and enjoy his visit." Visitor centers were lauded as "the center of the entire information and public service program for a park." [37] One hundred and nine visitor centers were slated for construction over the ten-year period. This new type of park facility would not only embody new park visitor management policies, but also the spirit of Mission 66, which looked forward to an efficient Park Service for the modern age.

During the early 1950s, Park Service architects and planners began developing a centralized service facility to manage increased visitation. Small rustic museums, such as those designed by Herbert Maier in the 1920s and 1930s, could no longer meet the needs of tourists expecting trailer lots and modern campgrounds. The updated facility, equipped with basic services and educational exhibits, was known in its early stages as an "administrative-museum building," "public service building," or "public use building." As this range of labels suggests, the Park Service was struggling not only to combine museum services and administrative facilities but to develop a new building type that would supplement old-fashioned museum exhibits with modern methods of interpretation. In February 1956, Director Wirth issued a memorandum to help clarify the use of terminology applied to the new buildings, explaining that "there are differences in the descriptive title, although most of the buildings are similar in purpose, character and use." [38] From then on, Wirth expected park staff to use "visitor center" for every such facility, even "in place of Park Headquarters when it is a major point of visitor concentration." As late as 1958, however, the matter remained unclear to many park visitors. When the topic was raised at a design conference, it was noted that "the term 'Visitor Center' is sometimes confusing to the public as it is an unusual and specialized facility which may be associated with shopping centers with which the general public is familiar." [39] If still puzzling to some, the building's label emphasized the novelty of the visitor center and bolstered the Park Service's image with high-profile examples of Mission 66 progress.

The Custer Battlefield museum and administration building, designed by Daniel M. Robbins & Associates of Omaha, demonstrates the transition from early Park Service museum buildings to standard Mission 66 visitor centers. The building was constructed in 1950, the first year since World War II that congressional appropriations for the parks included museum funding. [40] A lobby space and offices were incorporated into the new museum, but orientation areas remained small; no audio-visual or auditorium space was included, and restrooms were relegated to the basement. Visitor circulation between the various areas does not appear to have been a major consideration. In 1964, the WODC made preliminary designs for an addition to the "visitor center," and construction drawings were drafted by Max R. Garcia, a contract architect based in San Francisco. The new wing added restrooms and offices to one end of the building. [41]

The Department of the Interior Annual Report for 1953 announced the commencement of "the first major public use development at Flamingo, on Florida Bay," which would consist of "a boat basin and other developments . . . camping and picnic facilities, dock and shelter building, roads, and water and sewer systems." At this time, "public use" was still a general term, applicable to a marina or an interpretive facility. The report also noted "administration and public-use buildings at Joshua Tree and Saguaro National Monuments, and utility buildings in Potomac Park, Washington, D.C., and at Death Valley National Monument." [42] Other early precedents for visitor centers included the public information centers at Yorktown and Jamestown.

The public use building planned for Carlsbad Caverns in July 1953 underwent the transition to visitor center during its design and construction. Preliminary drawings for the building were produced by the Office of Design and Construction in Washington, D.C., before the creation of the eastern and western design offices. Thomas C. Vint, chief of the Washington office, signed off on the proposal for a streamlined, two-story public use building with steel and glass facade. It featured a central lobby area and, on the left side, a coffee shop/fountain/dining room, curio store, and kitchen. The museum and auditorium were entered from the right side of the lobby, which included the women's restroom. Park Service offices were in the basement, along with the men's restroom, and on the second floor, where they overlooked the double-height lobby. [43] By December 1954, a more detailed preliminary design for the Carlsbad Caverns facility had been drafted in which the entrance lobby was attached to a lounge area on the right side surrounded by restrooms, an exhibit space, and a ticket booth. The concession area was further defined as a curio shop, coffee shop, nursery, playroom, kitchen, and offices. This design incorporated an existing elevator building constructed in 1932, and one wing of the new facility was built by the concessioner, the Cavern Supply Company, with guidance from the Mission 66 staff. [44] The 1955 Annual Report called it "a public use building and elevator lobby, museum and naturalists' offices." [45] By January 1956, "the Public Use Building was in the final stage of preparation," but when bids for construction were opened in March, the building was referred to as a visitor center. [46] In his dedication speech nearly three years later, Conrad Wirth praised the Carlsbad Caverns Visitor Center for its use of "modern design" and "modern high-speed passenger elevators." [47]

Figures 7 and 8. Carlsbad Caverns Visitor Center. (Photos by Jack E. Boucher. Courtesy National Park Service Historic Photograph Collections, Harpers Ferry Center.) |

Early proposals for the public use building at Grand Canyon suggest a similar struggle with programmatic aspects of the new facility. Preliminary drawings of the building were produced in 1954, with several proposals designed by Cecil Doty. One early scheme featured rooms organized around an open courtyard, a floor plan reminiscent of Doty's design for the Santa Fe Headquarters almost twenty years earlier. The visitor entered the lobby and faced an information desk. Restrooms were on the right, and a hall led to a wing of offices. Exhibit spaces began on the left side and wrapped around the interior courtyard. An auditorium was located behind the exhibit space. The expanded role research would play in the Mission 66 program was suggested by a series of three "study collection" rooms, an associated workshop, library, and storage for the reference print and slide files. Administrative offices were located in this area. The courtyard scheme allowed visitors to enter and exit rooms across the patio as they pleased.

Other designs for Grand Canyon's public use building centered around the lobby space and information counter. In one scheme, the museum wing was located on the left, with three square rooms en suite—exhibit room, study collection, and workshop. The restrooms were located immediately to the right of the entrance, and the library and offices behind the information counter. An alternative known as "Plan B" consisted of a similar arrangement of spaces, but omitted many of the interior partitions, foreseeing the "open plan" of the future. Despite variations in plan, the front facade of the various proposals remained remarkably similar. The entrance area was mostly glass framed in decorative brick. The exhibit wing to the left was cement stucco and the wing to the right either additional brick or stucco. The building was long and low, with little to attract attention except the flagpole and sign.

By 1955, the courtyard scheme had been chosen, perhaps because its plan allowed for more flexible circulation. Visitors entered a lobby and were confronted with an information desk on their right, directly in front of the rangers and superintendents' offices. The library and restrooms were straight ahead, and the exhibit space, lecture room, study collection/workshop, and offices arranged in clockwise procession around the courtyard. Other versions of this plan included an auditorium behind the exhibit room, but this facility was never built. The public use building was an immediate source of pride for the Park Service, which praised this "visitor center" as "a one-stop service unit" in 1956. An information desk complete with uniformed ranger, lobby exhibits, an illustrated talk, and a park museum "where a great variety of exhibits, arranged in orderly and effective fashion" were among the many conveniences for the visitor. The presence of the park superintendent and naturalist was also considered remarkable, as were the study collection, workshop, and library. According to the Park Service, the new building provided much-needed efficiency and economy. [48]

Figure 9. Grand Canyon Visitor Center, originally known as a public use building, in 1998. (Courtesy National Park Service.) |

A New Style

The Mission 66 era visitor center also embodied a distinctive new architectural style that can be described as "Park Service Modern." By the late 1930s, Park Service architects had become aware of the influence of European modernism on many of their contemporary professionals, but the strong institutional tradition of rustic architectural design prevented modern architecture from having a significant influence. Park Service designers knew that American architecture was changing fundamentally, and the situation had also changed in the national parks. Years of deferred maintenance followed by unprecedented levels of park use put tremendous pressure on New Deal era facilities. "Rustic" began to take on negative connotations of dated, inadequate, and even unsanitary. At the same time the profession of architecture in the United States embraced modern architecture with unqualified enthusiasm, and the American construction industry was being transformed by new inexpensive materials and labor saving techniques.

Park Service Modern architecture responded to the new context of postwar social, demographic, and economic conditions. The new style was an integral part of a broader effort at the Park Service to reinvent the agency, and the national park system, for the postwar world. The creators of Park Service Modern were certainly not new to the Park Service or to national park design. Director Wirth, for example, had been responsible for the Park Service's state park development program in the 1930s. His chief of the Washington planning and design office, Tom Vint, had been chief landscape architect since 1927, and was one of the principal creators of the Park Service Rustic style. Other Park Service planners and designers who remained active in the 1950s, such as Cecil Doty, had been principal figures during the prewar, Park Service Rustic era. But if in many ways this group continued the tradition of park planning that they had created over the previous decades, in other ways, postwar conditions, new practices in the construction industry, and federal budget policies of the era necessitated new approaches to national park management.

These new approaches were especially evident in the design of the new visitor centers. The showcase facilities were clearly intended to exploit the functional advantages offered by postwar architectural theory and construction techniques. The larger, more complex programming of the visitor center encouraged Park Service architects, especially Cecil Doty, to take advantage of free plans, flat roofs, and other established elements of modern design in order to create spaces in which larger numbers of visitors could circulate easily and locate essential services efficiently. Such planning implied the use of concrete construction and prefabricated components and was further complemented by unorthodox fenestration and other aspects of contemporary modern design. At the same time, Park Service Modern also built on some precedents of earlier rustic design, especially in the use of interior courtyards and plain facades, which Cecil Doty had used, for example, in Pueblo revival structures of the 1930s.

The architectural elevations of Park Service Modern visitor centers—apparently so different from the applied ornament and historical associations of Park Service Rustic—also reflected the new approach to designing what was, after all, a new building type. Stripped of most overtly decorative or associative elements, the architects typically employed textured concrete with panels of stone veneer, painted steel columns, and flat roofs with projecting flat terraces. These were established formal elements of the modern idiom, but they also often allowed the sometimes large and complex buildings to maintain a low, horizontal profile that remained as unobtrusive as possible. Many visitor centers were sited on slopes, so that the public was presented with a single-story elevation, while the rear (service/administrative façade) dropped down to house two levels of offices. Stone and textured concrete could also take on earth tones that reduced visual contrast with landscape settings. The Park Service Modern style developed by the Park Service during the Mission 66 era was a distinctive new approach to park architecture. The style was quickly adopted and expanded upon by Park Service consultants, notably Mitchell/Giurgola and Neutra. The Park Service Modern style soon had a widespread influence on park architecture not only in the United States, but internationally as well.

Park Service Modern architecture also reinterpreted the long-standing commitment to "harmonize" architecture with park landscapes. The Park Service Rustic style had been essentially picturesque architecture that allowed buildings and other structures to be perceived as aesthetically harmonious elements of larger landscape compositions. The pseudo-vernacular imagery and rough-hewn materials of this style conformed with the artistic conventions of landscape genres, and therefore constituted "appropriate" architectural elements in the perceived scene. Rustic buildings harmonized with the site not just by being unobtrusive, but by being consistent with an aesthetic appreciation of the place. Park Service Modern buildings were no longer truly part of the park landscape, in this sense, since they were not sited or designed to be part of picturesque landscape compositions. But in many cases this meant that buildings could be sited in less sensitive areas, near park entrances or along main roads within the park. At times, the new, larger visitor centers could be even less obtrusive than rustic buildings often had been. Park Service Modern architecture, at its best, did "harmonize" with its setting, but in a new way. Stripped of the ornamentation and associations of rustic design, Mission 66 development could be both more understated and more efficient. If the complex programs and extensive floor areas of the new visitor centers had been designed in a rustic idiom, the buildings probably would have taken on the dimensions and appearance of major resort hotels. Park Service Modern offered a new approach that, when successful, provided more programmatic and functional space for less architectural presence.

The new style had its critics from the very beginning, but Park Service Modern, as developed by Park Service designers during the Mission 66 era, became as influential in the history of American national and state park management as the Park Service Rustic style had been. During the postwar era, the Park Service succeeded once again in establishing the stylistic and typological prototypes for new state and national park development all over the country.

The Visitor Center

The Mission 66 visitor center remains today as the most complete and significant expression of the Park Service Modern style. Mission 66 planners coined the term "visitor center" to describe a building that combined old and new building programs and that served as the centerpiece of a new era of planning for American national parks. The influence of the Mission 66 visitor center was profound. New visitor centers (and the planning ideas and architectural style they implied) were used in the development or redevelopment of scores of state parks in the United States, as well as nascent national park systems in Europe, Africa, and elsewhere. In 2000, the visitor center is still the core facility of park development programs for parks of various sizes and in various contexts all over the world.

The use of the word "center" indicated the planners desire to centralize park interpretive and museum displays, new types of interpretive presentations, park administrative offices, restrooms, and various other facilities. The underlying theory relates to contemporary planning ideas such as shopping centers, corporate campuses, and industrial parks, all of which sought to give new civic form to emerging patterns of daily life and urban expansion in the late 1940s and 1950s. Like the shopping center, the visitor center made it possible for people to park their cars at a central point, and from there have access to a range of services or attractions. Earlier "park village" planning had typically been more decentralized, with different functions (museum, administration building, comfort station) spread out in an arrangement of individual, rustic buildings. The Mission 66 visitor center brought these activities together in a single, larger building intended to serve as a control point for what planners called "visitor flow," as well as a more efficient means of serving far larger numbers of visitors and cars in a more concentrated area. Centralized activities created a more efficient pattern of public use, and assured that even as their number grew to unprecedented levels, all visitors would receive basic orientation and services in the most efficient way possible.

Considering the commitment of Mission 66 era planners to accommodating the growing numbers of people who wanted to visit the parks, the centralized visitor center was an essential approach to park preservation. The visitor center facilitated, yet concentrated, public activities and so helped prevent more random, destructive patterns of use. The siting of visitor centers was determined by new considerations in park master planning that involved the circulation of unprecedented numbers of people and cars. While on the one hand the Park Service remained committed to making the parks accessible to all who wanted to use them, on the other agency planners also felt it was desirable to continue to concentrate automotive access in relatively narrow areas and road corridors, most of which were already developed for the purpose. As a result, Mission 66 development plans (at least in larger parks) usually called for the intensification of development in existing front country areas, rather than opening back country areas to new uses. This implied road widenings, the expansion of campgrounds and parking lots, and often, the construction of a new visitor center. The visitor center was therefore sited in relation to the overall park circulation plan, in order to efficiently intercept visitor traffic. The criteria for siting Mission 66 visitor centers therefore differed significantly from the criteria for siting and designing the rustic park villages and museums of the prewar era.

The planning and design of visitor centers began in the Park Service offices of design and construction in San Francisco (WODC) and Philadelphia (EODC). Both offices had been established as part of the Park Service's reorganization in 1953, and both were overseen by the central planning and design office in Washington, D.C. Neither the WODC nor the EODC was prepared for the quantity of work Mission 66 would bring to the drawing boards. Rather than hire additional architects and landscape architects who would have to be laid off at the conclusion of Mission 66, the Park Service planned to contract out work to private firms on a project by project basis. In most cases, the Park Service furnished contract architects with preliminary drawings, which the consultants would then use as the basis for the developed design. In some cases, consultants simply provided the contract drawings for designs that had been fully developed in-house. Visitor centers were typically the most expensive new buildings in the parks, as well as high-profile commissions and, therefore, attractive to private consulting firms. [49]

Although the need to hire additional employees for architectural work was commonly explained as a matter of practical necessity, A. Clark Stratton, who replaced Tom Vint as the director of the Washington planning and design office in 1961, offered a different explanation for the influx of contract architects. In an interview, Stratton described how the Park Service was required by the General Services Administration (GSA) to hire professional design consultants for all buildings exceeding $200,000 in cost. Stratton's office could request authority from the GSA to hire their own consultants, or they could allow the GSA to manage their larger projects. Once the specifications and working drawings had been completed, the Park Service took over construction supervision. During the early years of the Mission 66 program, the GSA had handled the Yorktown and Jamestown contracts, yielding "not too satisfactory" results, according to Stratton. The Park Service clearly preferred managing its own projects. Stratton's comments help to explain why most of the Park Service's contracts with private architects involved larger visitor center commissions, while lower budget projects were left to in-house designers. Smaller park buildings, such as comfort stations and employee housing, were standardized and controlled under strict budgetary limitations. [50]

But whether or not consulting architects were employed, in all projects the Park Service retained control over the location of buildings and, in many cases, significant aspects of the consulting firm's design. The planning of early visitor centers reflected the Mission 66 concern with protection and use, the idea that park development provided the key to preservation. According to the 1955 Annual Report, the Park Service decided to locate administration offices, warehouses, shops, and residences away from areas devoted to visitors, creating separate "zones" for maintenance, employee housing, administration, and visitor services. Location within the park was also an important interpretive issue. Planners debated whether visitor centers provided better visitor orientation from a location near the entrance to the park, or were more effective near a significant feature that visitors would want to see and know more about. In some cases, this issue was resolved by creating secondary visitor centers, which were usually little more than a single exhibit space equipped with restrooms.

Throughout the Mission 66 period, the Park Service's overriding goal for its visitor centers was to improve interpretation and stimulate public interest in the park. To do this, the park's "story" was to be told as clearly and effectively as possible. Historians and interpreters played crucial roles in the Mission 66 planning process. According to Robert Utley, chief historian for the Park Service beginning in 1964, historians such as Roy Appleman and Ronald Lee favored siting visitor centers "right on top of the resource" so that visitors could "see virtually everything from the visitor center." [51] The location of visitor centers in sensitive areas often occurred at cultural sites and battlefields, where the purpose of the visitor's trip to the site was to gain a fairly comprehensive understanding of an important historic event. The preservation of cultural and natural resources sometimes became a concern, but was rarely articulated, according to Utley. The siting of a visitor center among the ruined structures at Fort Union, for example, was deemed advantageous for interpretation. During the Mission 66 period, the Park Service strove to educate the public, sometimes even at the expense of encroaching on the historical or natural environment. Mission 66 historians and planners believed that more effective public education justified such encroachments, and that the resulting understanding of sites would lead to greater support for preservation. But if this priority meant sometimes siting visitor centers in sensitive areas, it did not extend to other types of development. Director Wirth emphasized that "definite steps were taken to move as many of the administrative, government housing, and utility buildings and shops as possible out of the national parks to reduce their interference with the enjoyment of park visitors." [52]

Within the visitor center building, Park Service designers faced the challenge of orienting visitors and directing them to desired services. These design decisions also affected visitor impact on park resources. The visitor center was considered "the hub of the park interpretive program," and a method of orienting park visitors who "lacking these services, drive almost aimlessly about the parks without adequate benefit and enjoyment from their trips." [53] Not only was the visitor center a signpost intended to attract the aimless visitor within, but also a method of distributing information and other services in the most efficient and significant manner. Park Service architects confronted such issues in the development of building "circulation" or "flow" diagrams. Visitor circulation patterns were particularly important in this type of building, because people were expected to use the building in different ways; while some would study the exhibits and watch the films, others were only interested in visiting the restrooms or purchasing a park map. At this early date, Park Service architects had no precedents for use patterns, and, therefore, only a vague idea of how the new buildings would function.

The Park Service design and construction staff and interpretation staffs held joint meetings on visitor center planning in November 1957 (EODC) and February 1958 (WODC) and distributed their general findings in a summary. The discussions focused on participants' experience at early visitor centers, particularly those at Colonial National Historical Park and Grand Canyon. Conference participants discussed the desirability of open design, the need for outdoor restrooms, the importance of determining anticipated numbers of visitors, and the consideration of administrative requirements. Planning visitor center interpretation in conjunction with roadside and trailside interpretation was also encouraged. Individual spaces were to be designed with environmental factors in mind. If the lobby served as "a transition area for the harassed visitor between the crowded highway and the park atmosphere," it should "convey a mood and invite a relaxed frame of mind." Assembly rooms had actually become multiple use spaces and were more effective with flat rather than sloping floors. These spaces also played a role in the visitor's "transition from 'outside' into the park atmosphere." Exhibits might require artificial light for curatorial purposes, but they also benefited from a little daylight "to avoid claustrophobia." Finally, information counters could only function effectively at the minimum height requirements suggested, and portable counters were often most useful. [54]

In his discussion of visitor center placement, John B. Cabot, supervising architect for the EODC, described three potential locations. An entrance visitor center established the mood of the park and introduced the visitor to "the total interpretation of park values." The "en route" center posed the problem of simultaneously introducing the visitor to the park and providing information about the site to be visited. Most common was the "terminal visitor center," located at a popular destination, which supplied the visitor with a summary of park values while incorporating relevant information about the area; architects of these centers were encouraged to make use of surrounding views in their designs. According to Cabot, the location of the visitor center influenced the development of the building program because placement "affects how, in what sequence, the story is told, as well as how much or how little." This narrative depended, to a great extent, on the type of park under consideration. Whereas any of dozens of locations on the edge of natural areas might serve to orient visitors in wilderness parks, most historical parks could only be adequately understood with the help of interpretation presented in close proximity to the commemorative site. In a January 1960 report on visitor centers, the chief of interpretation commended the "desirable" siting of Colonial (Yorktown), which featured an "excellent view of the battlefield from the Seige Line Lookout on the roof of the visitor center," but criticized that of Grand Canyon, which stood midway between Mather Point and Grand Canyon Village, as "too far removed (1/3 mile) from the Canyon Rim . . ." Park Naturalist Shultz commented that "a visitor center should be 'in touch' with the feature it interprets." [55]

Once planners had chosen a building site, architects considered the park's story on a more intimate level. Cabot demonstrated how "visitor sequence diagrams" (flow diagrams) showed alternatives for visitor travel through a series of spaces; a typical example placed reception/information (lobby) in the center, with the assembly (auditorium), toilets, administration, and interpretation (museum exhibits) areas grouped around it. In the diagrams, spaces were represented by circles of varying sizes. One alternative placed a circulation terrace between the various areas, allowing the visitor to choose his or her route. Cabot suggested that architects develop a sequence analysis, flow diagram, and estimates of spatial dimensions before beginning preliminary drawings. Such planning required a close working relationship between museum professionals and architects, as indicated by Cabot's lengthy outline for visitor center design. [56] The "architectural treatment" of assembly or audio-visual rooms depended, in part, on mechanical systems and park programs. Funding for certain "audio-visual devices" became available in 1956, too late for incorporation into early visitor center plans, such as the Fort Frederica Visitor Center on St. Simons Island, Georgia. In the future, Ronald Lee recommended supplying architects with audio-visual related information, including descriptions of the devices, whether accommodations were needed for slide or film projectors, the audience's seating requirements, and the possibility of dividing auditorium space for several smaller presentations. Architectural consideration of such factors would lead to the development of "rooms which open from the lobby and which are separated from the exhibit rooms in order to keep the devices from distracting the visitor in his enjoyment of the exhibits." [57] Both Cabot and Lee encouraged architects to work closely with the interpretive branch and to contact consultants at the Washington Office for assistance in designing suitable spaces.

The professional partnership between Park Service designers and planners and interpreters and curators dated back at least to the creation of the Museum Division in 1935. During the planning stages of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, the Museum Division developed exhibits for the future museum and catalogued significant architectural fragments from the site as it was cleared for construction. In the early 1940s, architect Lyle Bennett wrote up a "Checklist for Museum Planning," addressing issues that would become relevant in his Mission 66 visitor centers designs. The close relationship between exhibit and architectural designers was strengthened by Tom Vint during the early years of Mission 66. Vint discussed exhibits at Grand Canyon with architect Cecil Doty, and it was typical for him to consult with Ralph H. Lewis or another museum expert on interpretive aspects of visitor center design. [58] Ten years after the official conclusion of Mission 66, Lewis published Manual for Museums, a technical handbook for curators on collections management. Although visitor centers are beyond the scope of the work, its frontispiece is a color photograph of the Mission 66 visitor center at Wright Brothers National Memorial. This "characteristic example of museums in the National Park System," was still a suitable representation of current Park Service curatorial standards nearly twenty years after its construction. [59]

Mission 66 caused a surge of activity in the museum branch of the Park Service that led to the re-opening of the Western Museum Laboratory in San Francisco's Old Mint building. [60] Within months of its organization, the laboratory began work on exhibits for Quarry Visitor Center at Dinosaur National Monument, the Mission 66 building slated for a grand opening June 1, 1958. [61] Correspondence between the Division of Interpretation and the director indicates that Park Service museum professionals influenced the design of the center. The contract architects, Anshen and Allen, drew up exhibit plans based on the Western Museum Laboratory's requirements. In April, the Laboratory corrected some circulation problems in the construction drawings. [62] Since the museum professionals must have provided preliminary designs, other alterations may have taken place during the planning process.

The development of the visitor center not only increased the demand for museum work, but also opportunities to supplement traditional dioramas and displays with more innovative "hands on" exhibits and audio-visual productions. The Mission 66 report of 1956 noted that museums were frequently part of the administration building or visitor center and emphasized the great importance of museum collections in preserving "priceless national legacies." Audio-visual presentations were also seen as a means of reducing costs and presenting interpretive material more quickly and effectively. Improvements in mechanical systems and the production of high-quality 16 mm films were the wave of the future. This technology would replace more traditional museum exhibits—and change the role of museum professionals—in later visitor centers, such as the Headquarters at Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado. Even the 1963 preliminary designs for this building featured an enlarged audio-visual room rather than exhibit space, demonstrating the transformation from museum-administration building to visitor center within the decade.

Figure 10. This abstract rendition of a visitor center appeared on the cover of the 1959 National Park Service brochure, Mission 66 in Action. |

The cover of "Mission 66 in Action," a 1958 brochure promoting the program, features a streamlined, modern visitor center and viewing terrace dotted with visitors. Another drawing of a simple, rectangular visitor center building is pictured inside. Thirty-four of these new "focal points of park activity" had already been completed and twenty were under construction. By this time, the Park Service was on its way towards establishing standards for visitor centers, at least in terms of in-house examples. The design conference offered park architects important tips on early planning and guidelines for developing appropriate buildings. Park publications promoted modern materials for design, and during the early 1960s, Park Service personnel could look at their own publications for guidance.

Park Practice Design, a joint publication of the Park Service and the National Conference on State Parks, featured a rustic wood museum building in 1957, but qualified its praise with the observation that it had "limited application because of its architectural character and the fact that it would be relatively expensive to construct." These issues were no longer applicable in 1962, when the publication emphasized the centralization of functions, circulation of visitors, and presence of modern utilities in visitor centers at Pipestone, George Washington Carver, and Everglades. Writing for the Park Service newsletter Guidelines, Howard R. Stagner, chief of the Division of Natural History and a member of the original Mission 66 planning staff, compared visitor centers to modern businesses. The overwhelming purpose was luring people inside. Stagner noted the absence of any standard plan for visitor centers, since each varied according to its reason for being. Taken out of context, the visitor center had no inherent value, but placed near a point of interest, it became indispensable to the curious park visitor. By 1963, museum professionals described how the visitor center allowed the Park Service to "orient the public according to its own objectives." This was achieved through what had already become a standard set of experiences: approaching the information desk, discovering one's location on a map, watching a narrated slide production, visiting the museum, taking in a view, and then proceeding down the road to a major attraction. [63]

During the last few years of Mission 66, both the EODC and the WODC experimented with visitor center plans that moved away from the centralized, single building model. The new designs were of two basic types—an entry lobby with distinct wings for other services and a series of independent buildings grouped around a courtyard or terrace. The visitor center and administration building at Saratoga, New York, designed by Don Benson and the EODC staff in 1960-1962, is an early example of this effort to clarify services and the circulation between them. Offices are housed in a hut-like space adjacent to a similar form containing a lobby and roofed terraces. These six-sided "huts" are connected by a corridor to the assembly/museum area, which is similar in plan and outward appearance. The exterior walls of all three areas are covered with beveled wood siding and the six-sided pointed roofs are protected by hand-split wood shingles. Although the Salt Pond Visitor Center (1964), Cape Cod National Seashore, Massachusetts, was based on a different plan and aesthetic treatment, it also effectively dispersed services into three distinct areas. EODC Architect Ben Biderman designed the visitor center with a central entrance lobby between an audio-visual room and museum. The elevation reads as three separate buildings, but the two wings are connected to the lobby with glassed-in corridors. In contrast to the Saratoga Visitor Center, Salt Pond emphasized the character of each area with distinctive roof designs and wall treatments.

Figure 11. Salt Pond Visitor Center, Cape Cod National Seashore. Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center. |