|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers |

|

RURAL HISTORIC LANDSCAPES AND INTERPRETIVE PLANNING ON SOUTHERN NATIONAL FORESTS

DELCE DYER AND QUENTIN BASS

The U.S. Forest Service manages over four million acres in six Southern Appalachian forests. The Cherokee National Forest in Tennessee is one such Appalachian forest with a wide variety of cultural resources found throughout its 625,000-acre expanse. Most of these resources can be considered cultural landscapes, and each exemplifies typical patterns of land use over time in the Southern Appalachians.

In the past year, National Forests in the Southern Region have been developing forest-specific master plans for interpretive services. At each Forest, a mission statement, a set of specific goals, and an initial inventory of interpretive resources has been developed by an interpretive team of landscape architects, archaeologists, recreation specialists, and others. In addition to this planning approach, the Cherokee National Forest has recently received a draft "Cultural Resource Overview" which provides a bibliographic base for documenting and assessing forest cultural resources.

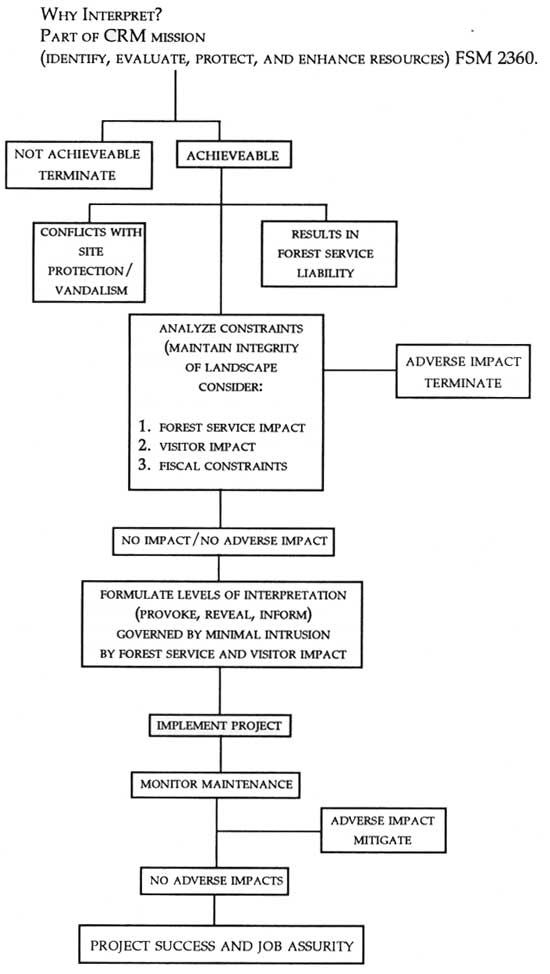

Whether an agency is trying to interpret themes over thousands of acres or just one acre, a systematic process is necessary to determine what and how to reveal cultural landscapes to the public. The Forest Archeologist has prepared a flow chart to clarify steps in the interpretive planning process (Figure 1). The following are also a few questions to be considered by cultural resource managers:

1. What landscapes should we, as single agencies and members of Southern Appalachian Man and the Biosphere Cooperative (SAMAB), strive to conserve and in what condition?

2. Do we allow the public to view fragile cultural resources, or do we keep them secreted away for their own protection?

3. What do we want to interpret to the public? We can be guided by interpretive goals and Appalachian themes/contexts developed on-forest, through SAMAB, and through other multi-agency partnerships to determine which resources best reflect our interpretive goals.

4. How do we plan for, monitor, and mitigate the effects of increased tourism upon those cultural landscapes placed under our curation?

5. How do we sensitively interface modern additions—visitor circulation, restrooms, parking, signage—with the least intrusion to the cultural landscape?

PLANNING STEPS FOR CULTURAL LANDSCAPE INTERPRETATION

Given these criteria, it is incumbent that cultural resource managers and land planners develop and delineate aesthetic design guidelines and tailor them to the individual cultural resources on a case-by-case basis. One possible method for guiding design of sensitive amenities may be the Recreation Opportunity Spectrum (ROS) system, a land management planning system developed by the Forest Service in the early 1980s. [1] This is a system that strives to categorize settings and facilities sought by visitors into a range of seven landscape experiences from primitive to urban. These guidelines can be applied to interpretive development, but in the Southern Region, they have not yet been tied to interpretative facilities.

The following examples of categories of cultural landscapes from the Cherokee National Forest will help introduce the range of resources found on public and private lands throughout the Southern Appalachians.

OLD ROADS/WATER CROSSINGS

The Unicoi Turnpike was a major artery used by the Cherokee Indians and later by Euro-American settlers to travel between South Carolina, North Carolina, and east Tennessee. A pristine, preserved, two-mile section of the historic roadway still exists in a remote area of the Hiwassee District near the North Carolina border.

The Old Copper Road, on the banks of the Ocoee River and adjacent to the Ocoee Scenic Byway, is another historic road built in the 1850s with Cherokee Indian labor to improve transportation of copper from its source in Copperhill to the railroad in Cleveland, Tennessee, a distance of thirty-five miles. The last significant segment of the road, a four-mile length, is currently used by local residents to access a popular swimming area called "Blue Hole," so named from the bluish tint cast by copper sediments in the water. Plans are underway to restore this section of the Copper Road and develop the area into a major recreation corridor.

With portions of nine rivers and innumerable streams running through the lands of the Cherokee National Forest, there are scores of river-fording sites that range widely in historic importance. One well-known ford is located on the Tennessee-North Carolina line on the French Broad River at a place known as Paint Rock on the Nolichucky Ranger District. The site has a long history as a culturally significant locale, as evidenced by prehistoric pictographs on Paint Rock, archeological remnants of a blockhouse dating to the 1790s, and remains of structures from subsequent layers of settlement. Another site of this type is a ford located at the mouth of Little Citico Creek on the Tellico Ranger District. This point served as an 1819 boundary corner which defined a northernmost point of Cherokee lands prior to the Cherokee Removal of 1838. The area is currently being developed into a horse camp and trail system: the old ford will provide a solid-base crossing for the horses. The area's archaeological sites associated with this period are also preserved.

NATIVE AMERICAN SITES

One excellent example which displays the continuum of Native American habitation on the Cherokee National Forest is the 345-acre tract known as the Jackson Farm on the Unaka District near Greeneville, Tennessee. Spectacularly preserved archaeological evidence of prehistoric, early historic, and protohistoric occupations, as well as the entire range of Euro-American exploration and settlement patterns are present at this site and can be investigated and interpreted through on-going archeological research. Located on the Nolichucky River between Greeneville and Jonesborough, Tennessee's two oldest towns, the site has excellent potential for tying Native American land use directly to later aspects of Southern Appalachian development.

UPLAND GRAZING

Transhumance, the seasonal movement of livestock to upland pasturage, was a major land-use pattern unique in America to the Appalachians. Along the upper elevations of the Cherokee National Forest are the remnants of a number of grassy "balds," the product of this upland grazing of cattle and sheep during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Multi-resource inventories and management plans for each of the Cherokee's "balds" are scheduled. Out of these studies will come information on historic boundaries, associated structures, fence patterns, and site-specific historic land-use practices. Plans are now underway for protection and interpretation of a series of these balds along the Tellico-Robbinsville Road, a proposed scenic byway which, when completed, will provide an overmountain connection between Tennessee and North Carolina.

Rock walls along the Appalachian Trail and elsewhere are often associated with upland grazing. A few extant structures, such as the log shepherd's cabin on the Appalachian Trail near Shady Valley, Tennessee (now used as a hikers' shelter), and archeological remnants of other structures attest to this widespread practice.

FARMSTEADS

The Forest Service is engaged in a major land acquisition program for the protection and relocation of the Appalachian Trail, a national scenic trail. In the process, the Cherokee National Forest has acquired a number of old farmsteads. One recent acquisition, near Dennis Cove on the Unaka District, included a double-pen log house (in poor condition), a log barn, a mature Chinese chestnut grove, some old apple trees, and other small scale elements.

Another significant farmstead acquired through the same process is the Scott-Booher tract near Shady Valley, on the Watauga District. At one time, the site was considered the most complete single rural historic landscape on the Forest. Public access to the site has been limited to foot traffic only, over about a half-mile of old road that offers glimpses of the farmstead. The approach road passes a series of fenced areas, all with similar gates: the orchard; the entrance to the house yard; the side yard and various outbuildings; the vegetable garden; and the barnyard/clothes washing place. Still in existence are a number of small scale elements, including a hand-hewn clothesline pole and the house spring, surrounded by a stone wall (one of five springs on the site). A twenty-tree apple orchard has a number of antique varieties yet to be identified. Through the umbrella of an organization like SAMAB, a comprehensive inventory of historic fruit varieties, old roses, and other ornamentals, as well as small-scale elements used at historic house sites in the Appalachians, could be compiled and made available to researchers of the regional cultural landscape.

One final note about the Scott-Booher site: the house was burned by arsonists in early 1991, which brings up tricky preservation and interpretive questions. Should we try to maintain structures which are susceptible to arson and vandalism? With the loss of one or more major architectural features, has the integrity of the site been too compromised? Should the fences, gates, and outbuildings be maintained as if the whole unit were still intact? Can the relict landscape itself be interpreted with signage?

FIRE TOWERS

Fire detection and its architecture is a part of Forest Service heritage. Towers on the Cherokee National Forest were constructed between 1920 and the mid-1940s, a few of these by the Civilian Conservation Corps. Each tower was labelled with huge identifying characters fashioned from poured concrete forms flush-mounted in the ground. On the Cherokee National Forest, the labels ranged from C-1 to C-18. C-1 is located near the VA-TN border, now on the Appalachian Trail; C-15 is atop Buck Bald on the Hiwassee District in the southern portion of the Forest.

With the advent of all-aerial detection, these structures have become anachronistic and have fallen into complete disuse. Several towers have been taken down in recent years. Remote locations and disuse have left the structures open to vandalism. As funding is available, extant towers and tower sites will be inventoried and documented. With a renewed interest in interpretation, selected towers may become facilities/points for interpretation of a by-gone era of forest management. The Meadow Creek tower on the Nolichucky District in Cocke County, Tennessee, is in fairly good condition, and is currently being maintained against vandalism. The structure is one of two of its architectural type on the Forest—a large square building, no more than twenty feet above ground level, accessed by a stairway, with a wide outdoor deck surrounding the interior windowed viewing-and-living facility. The architectural style better lends itself to public access than towers fifty feet or more above ground, accessed by narrow ladders or stairs. This structure could remain in place to interpret fire detection and could perhaps be retrofitted to be barrier-free. On the other hand, a tall tower such as the ninety-foot one at Oswald Dome near the Ocoee River seems dangerous for even fire spotters to climb! If this structure is taken down, it is possible that the cab could be mounted at ground level, either outdoors or inside a visitor center, to allow Forest visitors to climb through the trap door and operate the "Osborne Fire Finder" inside the diminutive space.

CIVILIAN CONSERVATION CORPS

On the lands of the Cherokee National Forest, there is a wide range of CCC-constructed camps and recreation areas, in varying states of preservation and repair. Some are in good condition, where modern development has been incorporated with sensitivity; others are poorly maintained or have been altered with little attention to the historic fabric.

McKamy Lake is one of at least five extant CCC-constructed swimming holes still in existence on the Cherokee National Forest. Located in a campground off the Ocoee Scenic Byway, this is the best preserved and is the most used of the CCC swimming areas. Heavy-timbered pavilions constructed by CCC labor remain in a number of picnic grounds; among these are Horse Creek, Backbone Rock, and The Laurels. Two 1937 photographs of the Laurels, a picnic area between Johnson City and Erwin were recently unearthed. Some elements are no longer there, but the old growth is still a prevalent feature. The 1937 plans called for retention of "Grove of White Pine and Hemlock (Demi-Virgin)." In 1958 and later, a series of site alterations were made, some sensitive, others not so. The roofing on the two pavilions was changed from wood to asbestos shingles. Paved walkways were installed in an attempt at barrier-free circulation or minimum maintenance. Some rock retaining walls, particularly those that completed an accessible wading area, were sensitive to the original design.

The Tellico Ranger Station was built for the Forest Service on the site of the first CCC camp in the state. The original CCC administrative office remains on-site, complete with terracing and stone wall. Two large buildings flanking the ranger station were used by the CCC enrollees; one is the former dining hall, now used for offices, classrooms, and storage. Barracks and other buildings were concentrated behind the present ranger station. Most of these structures, however were removed as the CCC camp was closing. What remains from the CCC era—administrative office, powerhouse, dining hall and its twin storage building, CCC-built ranger office, entrance drive, and other landscape elements—retain to a large degree the integrity of their original fabric. Down the Tellico River Road from the ranger station is the Dam Creek Picnic Area, marked by a typical CCC portal. The Dam Creek portal is similar to one at the Pink Beds picnic ground on the Pisgah National Forest, with the exception of a large carving wheel inside the shelter. This is a wonderful area with lots of old growth and secret nooks and crannies. The design and materials of this picnic area are relatively intact. Small scale elements remain, like low concrete grills, water fountains, a slate-lined drainage system, and a series of contemplation sites. The CCC designers anticipated heavy site use by constructing flagstone pads underneath each picnic site and bench.

Another type of CCC resource is the abandoned site of a former camp, like Camp Rolling Stone, in a remote corner of the Hiwassee District near the North Carolina border and the Unicoi Turnpike. Enough remains on the ground at this former camp to determine the arrangement. A camp swimming pool was fashioned by widening a part of the creek that ran through the camp. Extant are the steps to the barracks, chimneys to administrative buildings and mess hall, remains of the latrine, and the camp's protected water source, a spring with a dry-laid stone hood.

These are by no means an exhaustive inventory of the Forest's cultural landscapes. Southern forests are just beginning to develop their interpretive plans. These are however, representative of what can be found throughout the Appalachian forests, along with historic logging sites, caves, railroad beds, and a host of other resources.

All of us who are involved with public interpretation have a challenge before us, not only to inventory, document, evaluate, and protect our cultural landscapes, but to plan how to present them to the visiting public in the safest, most informative, thought-provoking and least intrusive way.

ENDNOTE

1 United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Regional Office, 1986 ROS Book (Atlanta: USDAFS, 1986).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

appalachian/sec5.htm

Last Updated: 30-Sep-2008