|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers |

|

FISH WEIRS AS PART OF THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

ANNE FRAZER ROGERS

WESTERN CAROLINA UNIVERSITY

Fish as a food source has been utilized in eastern North America since at least 2500 B.C., the beginning of the Late Archaic period. Fish provides animal protein which be can eaten fresh or stored for future consumption by drying or smoking. It may have contributed more to prehistoric diets than has been generally recognized. Because of their relatively fragile nature and small size, fish bones frequently do not preserve well in archaeological contexts, and the number of bones recovered can be affected by the use of equipment which is not designed to recover very small faunal remains. Fish hooks have been found in archaeological sites dating to the Late Archaic period, and it is likely that other means of capturing fish were in use at this early time as well. [1] Other methods may have included the use of nets, spears, fish poison, and various types of traps. The use of fish weirs represents an additional technique of capturing fish. Various forms of these are found throughout North America, absent only in those areas which have relatively unpredictable or minimal stream flows. [2]

Many methods used to capture fish also would not have left recognizable evidence in the archaeological record, as wood, bone, and fiber implements are subject to decay, especially in wet environments. For that reason, it is difficult to determine the range of methods used to capture fish, but it is likely that prehistoric peoples were familiar with a number of ways to obtain them. Ethnographically there is evidence for the use of nets, spears, bows and arrows, vegetable poisons, basket traps, and hooks and lines of various types.

The use of weirs is one of the most efficient means of capturing fish in terms of effort expended in relation to potential return. Various forms of these have been found throughout much of North America, constructed of wood, stone, or both. Rostlund suggests that while all weirs had a similar purpose, they varied greatly in form. [3] This reflects in part the situations in which they were constructed and also the purpose for which they were intended.

The principal function of a weir is to guide fish in to a situation that facilitates capture. In the case of weirs in tidal waters, fish come upstream with the current and are trapped when the tidal water recedes. In areas where anadromous fish swim upstream to spawn, weirs force the fish into enclosures where they can be easily taken. In inland rivers, fish are channeled downstream through a V-shaped structure where they can be captured in nets or traps, or by spearing or shooting with a bow and arrow. Stewart (1977) provides excellent illustrations of the various types of weirs and basket traps used on the Pacific Northwest Coast. [4]

In 1700 John Lawson visited North Carolina where he encountered the use of fish weirs along the coast. He describes "Jack, Pike, or Pickerel" being taken as an important fish and continues to say, "I once took out of a Ware, above three hundred of the Fish, at a time." [5] Several years later, John Brickell, also traveling in North Carolina, describes the capture of herring in "large Wears with Hedges of long Poles or Hollow Canes, that hinder their passage only in the middle, where an artificial pond is made to take them in, so that they cannot return." [6]

In a 1902 description of the Kepel fish dam on the Klamath River in northwest California, Yurok informants explained the construction of a dam or weir used to catch salmon as they swam upstream to spawn. This was made of poles, logs, and small stakes and was designed to force the salmon into enclosures from which they could not escape. [7] These weirs were constructed annually, requiring ten days to build. They were then used for ten days and were then intentionally destroyed, even though the salmon run lasted for several weeks. [8]

The construction of this weir involved much ceremonial activity, lasting from fifty-one to sixty-two days. [9] The emphasis on ceremonial proceedings may have indicated the importance of this storable protein food which helped to sustain them throughout the year, but it likely had social connotations as well. As this was one of the few communal activities engaged in by the Yurok, the ceremonial aspects may also have served to increase group solidarity.

In the southeastern United States, there are also ethnographic accounts of the use of weirs. These accounts include the use of nets and traps in conjunction with the use weirs. In Speck's description of the various hunting, trapping and fishing activities practiced by the Catawba Indians of South Carolina, he mentions weirs constructed of brush or stone. These were used in conjunction with basket traps which are described as follows:

In material and construction the basket trap is the same here as it is over the Atlantic coast region wherever found. The material is of white oak unplaned splints averaging one inch in width. The weave is checker-work (under-one-over-one) for both uprights and filling. The small or rear end is closed by the bent over splints, not by a plug of wood as are those of the Whites and Negroes...The entry to the basket is, as usual in such constructions, provided with splints with their free ends pointing toward the center of the interior and fastened to converge in the manner of a funnel. The entering funnel extends about two-thirds the length of the interior. The fish enter the basket to reach the bait, passing through the splint funnel but cannot go in the opposite direction to escape. The fish-trap, baited with corn bread, onions or persimmons, is attached to the bank of the lagoon where it is set by a line tied to a tree, and weighted with a stone. There being no opening at the rear of the Catawba fish-basket, the fish caught have to be removed by clumsily pressing down the in-turned splints of the funnel and squeezing them out by the way they entered. Some informants say that occasionally several splints in the side of the basket are left loose so that they may be taken out to empty the basket of fish. [10]

Speck also describes other methods used by the Catawba to obtain fish. One method involves impaling fish on cane or hardwood spears with fire-hardened ends. Speck says these implements were manufactured when needed and discarded after use. The Catawba also used bows and arrows, poisoned fish with the bark of the walnut tree (Juglans nigra), fished with a hook and line, strung trot-lines across rivers and streams, or used a net carried by two men walking on opposite sides of a creek to capture fish. [11]

While any or all of these methods may have been used prehistorically as well as historically, the advantage of using weirs to assist in the capture of fish is obvious. In coastal areas, fish are easily trapped behind dams or weirs when tides recede. Where fish swim upstream to spawn, large number of fish can be taken in a short period of time. In inland river and streams, the use of weirs is extremely efficient in terms of high return in relation to the amount of energy expended.

In the Southern Appalachian area, there is evidence of the use of weirs in a number of rivers and streams. While the dates at which these weirs were first constructed is impossible to determine, their widespread distribution is an indication of their previous utility. They are found in the Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and Georgia. In Georgia, weirs can still be seen in the Etowah River near the Etowah Mounds. In southwestern Virginia and upper east Tennessee, they have been reported in the Clinch and Holston rivers. In North Carolina, they are found in the Nantahala River at Standing Indian Campground, in the Hiwassee River near Murphy, in the Little Tennessee near the Cowee Mound site, and in several places in the Tuckaseegee River. There are no doubt weirs in other areas as well.

Weirs have tended to persist in these areas, in spite of legislation enacted in 1877 which could have served to eliminate them. The purpose of this law is not clear, but it may have been associated with efforts at that time to establish a commercial fishing industry in Jackson County. The law reads as follows:

AN ACT TO PREVENT THE OBSTRUCTION TO THE PASSAGE OF FISH IN THE TUCKASEEGEE RIVER.

Section 1. The General Assembly of North Carolina do enact, It shall be unlawful for any obstruction to the passage of fish up the Tuckaseegee river to remain in said river up to the mouth of Colooche creek in the county of Jackson, during the months of April and May, of each year, hereafter.

Sec. 2. It shall be the duty of any justice of he peace living within the limits of any of the townships of said county adjoining said river to see that this act is enforced, and said justices shall have full authority to enforce the same.

Sec. 3. Any one violating the provisions of this act shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof shall be punished by a fine not exceeding fifty dollars, or imprisoned [not] more than thirty days for each offence.

Sec. 5. That this act shall be in force from and after its ratification.

Ratified the 10th day of March, A.D. [12] (The "Colooche Creek" referred to in this passage is most likely Cullowhee Creek. Also, Sec. 4 is missing in the original).

In light of this statute, it is surprising that any weirs remain intact in this area. There has also been extensive flooding on the Tuckaseegee River in the past, with a major flood of one hundred-year proportions occurring in 1940. However, there are still several weirs visible under ideal conditions. In general, identification of these structures is dependent on water level, although careful observation of water surfaces in areas here they can be expected often indicates their presence.

Three weirs in Jackson County exemplify the range of visibility which characterizes these structures. All appear to be of prehistoric origin, and one has a history of recent utilization. These three weirs are similar in configuration to others observed in the Southern Appalachian area. Constructed of river cobbles and approximately twenty to thirty centimeters high, they are roughly V-shaped, with asymmetrical sides. The bottom of the V is downstream and is open to allow fish to pass through. The opening is oriented towards one bank rather than directly downstream. As a result, one side of the V is longer than the other.

All of these weirs are located in similar topographic situations. Each is in a shallow section of the river, at a depth which would allow unimpeded wading except in times of unusually high water. Banks tend to be low in these sections, permitting easy access to the river. In each case, there is a large, relatively flat terrace present on one or both sides of the river. A prehistoric archaeological site is adjacent to each weir. Unfortunately, these sites have not been scientifically investigated, so temporal assignment for their occupation is not available.

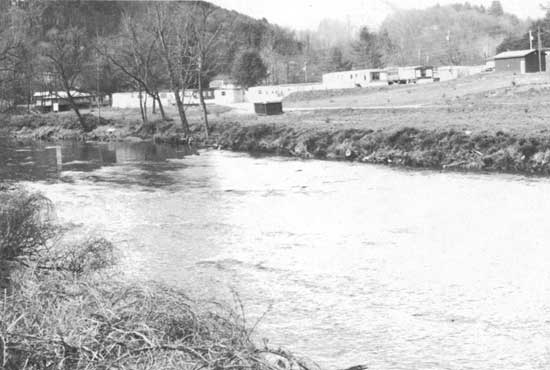

The first weir is immediately downstream from the present town of Cullowhee. The valley along Cullowhee Creek and the Tuckaseegee River in this area was extensively occupied prehistorically. The weir is less than one kilometer from a large Mississippian village and mound site and is within two kilometers of another site which contained evidence of Woodland, Mississippian, and historic Cherokee occupation.

|

| Figure 1. Cullowhee fish weir |

This weir was the most difficult to identify. While ripples in this section of the river had suggested the presence of a weir, it was not until the river was at an unusually low level that the weir could be clearly seen. It still exhibits the characteristic V-shaped form, although it appears to have been disturbed by either human or natural forces. The walls are no longer intact, and its outline is somewhat irregular, but it is undeniably a weir.

Approximately five hundred meters upstream from this weir are two additional obstructions that may be remnants of weirs, but these are so seriously disturbed that their identification is questionable. It is possible that these are weirs which were partially destroyed as a result of the statute passed in 1877.

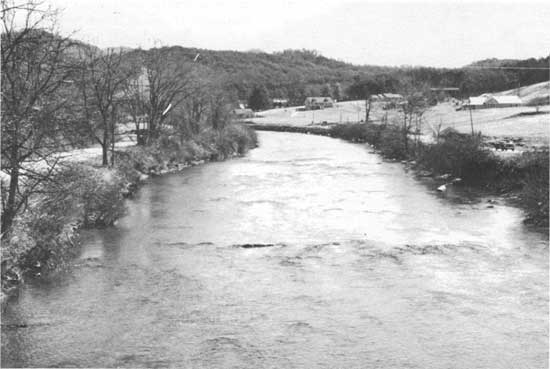

A second, more easily recognizable weir is located further downstream in the Tuckaseegee, in the wide bottom south of the town of Webster. This weir is mostly obscured except during periods of low water, but then its configuration is well delineated (Figure 3). It also has the characteristic V-shape, with walls formed by river cobbles and an opening at the downstream end.

|

| Figure 2. Webster fish weir. |

The third weir, also located near the town of Webster, is the best defined of the three (Figure 4). This definition, however, appears to be the result of relatively recent rebuilding. According to Mr. James Allman, the present occupant of the property adjacent to this weir, it was built by his great-grandfather Allman and a friend around 1880. [13] While this might be true, there are several reasons to believe that this weir was originally constructed prehistorically. First, the presence of prehistoric artifacts in both the garden of Mr. Allman and on the terrace across the river from his property strongly suggests that this is a prehistoric structure which was refurbished or reconstructed in recent times.

|

| Figure 3. Allman fish weir. |

Its location is sufficiently similar to that of the others in the area to support this suggestion, and its shape is virtually identical to the two upstream. Furthermore, since the previously mentioned North Carolina statute of 1877 specifically prohibited obstructions to the passage of fish during certain months of the year, it is doubtful that the effort required to construct such an obstruction would have been undertaken. The weir was later repaired by James Allman's grandfather, Mr. Arthur Allman, during the 1920s. One interesting aspect of Allman's recollections of the weir is its utilization as late as the 1940s. According to James Allman, his grandfather Arthur used the weir consistently until he was told by the local game and fish warden, a Mr. Ashe, that using traps to catch fish had become illegal in North Carolina. James Allman says that his grandfather stopped using the weir at that time, leaving his trap on the bank of the river where it eventually decayed.

Allman's recollection of the trap is that it was made from scraps obtained from a sawmill. These scraps consisted of the edges sawn from boards as they were trimmed, and ranged in width from one-half to two or three inches. Allman remembers the trap as being rectangular with a removable top. It was constructed so that fish could enter easily but were prevented from swimming back out by a cone-shaped arrangement of pointed slats facing the interior of the trap. The end of the cone was sufficiently narrow to prevent the fish from escaping, in a configuration similar to the Catawba basket trap described by Speck (1946). The trap was anchored at the downstream end of the weir by placing rocks on its top. It was only partially submerged, and could be opened easily to remove the fish which it contained.

Fish captured in this trap were hog suckers, white suckers, and red horse. These are all bottom-feeding fish and tend to be very bony. Mr. Allman said that his grandmother would preserve red horse, but not the other types of fish, by placing them in a fifty-gallon barrel between layers of salt. He said this salting process caused the smaller bones to "dissolve," making it possible to eat the fish more easily than when they were consumed fresh. This could have provided a dietary advantage. If small bones were consumed along with the flesh, they would add a small amount of calcium to the diet. A serving of red horse provides 98 kilocalories, 18 grams protein, and 2.3 grams of fat. [14]

Allman also remembered that his grandmother would preserve catfish by canning them in glass jars. These fish were skinned and gutted by his grandfather and sliced laterally into steaks to prepare them for canning. His grandmother would roll the catfish steaks in cornmeal and fry them to prepare them for the table. Catfish provide 103 kilocalories, 17.6 grams protein, and 3.1 grams of fat per serving. [15]

While Allman did not mention that catfish were captured in the trap placed at the end of the weir, their use as a storable food source indicates that the river was considered an important source of food for the Allman family, both for immediate consumption and for future use.

Both historically and prehistorically, fish appear to have been an important component of the diet of people in the Southern Appalachian mountains. They can be eaten fresh, stored for future use, and would have been an important adjunct to the small and large mammals that are usually thought to have provided the bulk of animal protein in the diets of these people. The widespread presence of weirs suggests that these structures played at least some part in subsistence procurement.

Although weirs that can be easily recognized are usually recorded by archaeologists, there has been little attempt to undertake a systematic study of their distribution or their placement on the cultural landscape. This is due in part to the difficulty of providing weirs with a temporal assignment, which limits their use in reconstructing the culture history of an area. However, their widespread occurrence indicates that they were useful to the prehistoric inhabitants of the area and were used to some extent by the later occupants as well. While sometimes difficult to recognize, weirs can be identified if careful examination is carried out in area where they are likely to be located. These include shallow sections of rivers which are bounded on one or both sides by relatively flat terraces. Even though many of these structures may have been partially or completely destroyed, an understanding of their placement and distribution can be of real value in understanding the utilization of the terrain by both prehistoric and historic occupants. As important components of the cultural landscape, fish weirs need to be recognized, interpreted, and preserved whenever possible.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allman, James. Personal communication, Sylva North Carolina, 29 December, 1992.

Brickell, John. The Natural History of North Carolina. 1737. Reprint. Murfreesboro, North Carolina: Johnson Publishing Co., 1968.

Claflin, William. "The Stallings Island Mound, Columbia County, Georgia," papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Anthropology, no. 14 (Cambridge, Mass, 1931).

Waterman, T.T., and A. L. Kroeber. The Kepel Fish Dam. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, vol. XXXV. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1943.

Watt, Bernice K., and Annabel L. Merrill. Composition of Foods. Agriculture Handbook no. 8. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture, 1965.

Lawson, John. A New Voyage to Carolina. 1709. Reprint. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1967.

Rostlund Erhard. Freshwater Fish and Fishing in Native North America. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1952.

Speck, Frank G. Catawba Hunting, Trapping and Fishing. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum, 1946.

Stewart, Hilary. Indian Fishing. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1977.

ENDNOTES

1 William Claflin, "The Stallings Island Mound, Columbia County, Georgia," Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Anthropology, no. 14 (Cambridge, Mass, 1931), 1-46.

2 Erhard Rostlund, Freshwater Fish and Fishing in Native North America (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1952), map 35.

4 Hilary Stewart, Indian Fishing (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1977).

5 John Lawson, A New Voyage to Carolina, 1709, Reprint (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 1967), 162.

6 John Brickell, The Natural History of North Carolina, 1737, Reprint (Murfreesboro, North Carolina: Johnson Publishing Co., 1968), 366.

7 T. T. Waterman and A. L. Kroeber, The Kepel Fish Dam, University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, vol. XXXV (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1943) 49.

10 Frank G. Speck, Catawba Hunting, Trapping and Fishing (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum, 1946), 16-17.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

appalachian/sec6.htm

Last Updated: 30-Sep-2008