|

ARKANSAS POST

The Arkansas Post Story |

|

Appendix 2:

DESCRIPTIONS AND LOCATIONS OF ARKANSAS POST

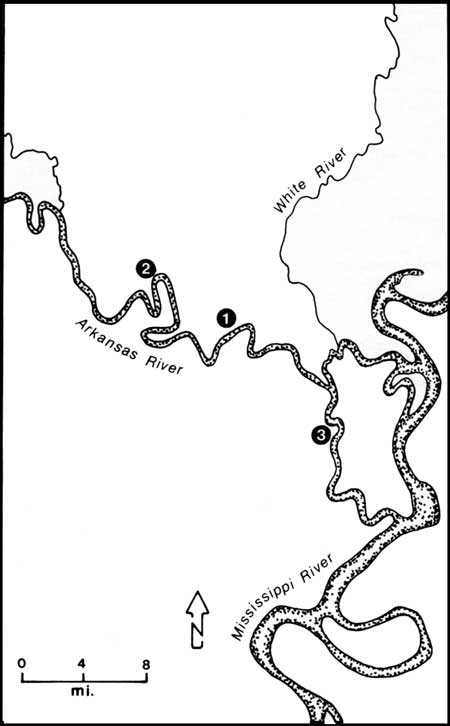

During the 118 years that France and Spain maintained a presence on the Arkansas River, their posts occupied several locations. To service river traffic on the Mississippi, proximity to the mouth of the Arkansas was essential. Few sites within 30 miles of the mouth of the river, however, were high enough to escape inundation during the devastating floods that occurred frequently along the lower Arkansas. Furthermore, defense of the post depended on the presence of the Quapaw Indians who often relocated their villages. As a result, the post was moved and rebuilt several times.

The different locations of Arkansas Post have been the subject of much controversy. Historians have rarely agreed on the number of posts represented, the dates constructed, or the locations they have occupied. Fortunately for the present study, two recent works have clarified this issue. First, one location of Arkansas Post has been verified in the field by University of Arkansas archeologist Burney B. McClurkan. [1] Second, historian Morris S. Arnold has diligently researched original documents that support the existance of seven posts in three different geographic locations. [2] The following discussion blends elements of both studies with descriptions of the different Arkansas Posts.

| ||||||||

Figure 41. The three locations of

Arkansas Post. After Morris S. Arnold, "The relocation of Arkansas Post

to Ecores Rouges in 1779," In Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 42

(Winter 1983), 323. Seven different French and Spanish forts have

existed along the lower Arkansas River, in three basic geographic

locations.

|

POST #1 (1686-1698)

In 1686, Henri de Tonti left six men on the Arkansas River to build a trading house and open commerce with the Quapaw Indians. The first recorded description of this post comes from Henri Joutel who arrived on the Arkansas in July, 1687, with the survivors of La Salle's last expedition.

Being come to a river [Arkansas] that was between us and the village, and looking over to the further side we discovered a great cross, and at a small distance from it a house built after the French fashion. [3]

It is seated on a small eminency, half a musket-shot from the village [Assotoue], [with] plains lying on one side of it. [4]

Joutel reveals that the post was on the north bank of the Arkansas River adjacent to the Quapaw village of Assotoue. [5] Further locational information is provided by De Tonti who visited the post for the first time in January, 1690. The location of my "commercial house," commented De Tonti, was at the village of Assotoue who "lived on a branch of the river [Arkansas] coming from the west," nine miles from the mouth of the river. [6]

The first post on the Arkansas was probably abandoned in 1698 following De Tonti's presence on the river to enforce the royal edict forbidding the trapping of furs south of Canada. By 1700, De Tonti's former factor led a party of English to the mouth of the Arkansas to trade with the Quapaw. [7]

Historian Stanley Faye has stated that the location of De Tonti's post was on the bank of Lake Dumond, a former channel of the Arkansas River. Partial support for this location is the presence of a nearby Quapaw village site, that archeologists concede may be the location of Assotoue. [8]

POST #2 (1721-1726)

On March 1, 1722, French explorer Benard de La Harpe arrived on the Arkansas River and found Lieutenant La Boulaye and Second Lieutenant De Francome living at the Quapaw village of "Zautoouys." Initially, La Boulaye had occupied a site at the village of "Ouyapes" on the Mississippi River, but because of flooding, the garrison moved one month later. A single soldier, Saint Dominique, remained at Ouyapes to await the arrival of trade goods for the warehouse the French maintained there. [9] The remainder of the garrison, at the time of La Harpe's inspection, had been sent to cultivate fields at the Law colony where they had permission to become inhabitants. [10]

Apparently, "Zautoouys" is merely a different spelling of "Assoutoue." Information indicates, however, that the Quapaw village had been relocated south of the Arkansas River since Joutel's 1687 description. A map prepared by Lt. Jean Benjamin Francois Dumont, scientist for La Harpe's expedition, clearly indicates that Zautoouys was south of the Arkansas River, the post immediately north of the river, and the Law colony a greater distance northeast of the garrison. [11] Dumont further attests to the continuity of La Boulaye's post and De Tonti's original 1686 location. [12] Of the post, Dumont remarked:

There is no fort in the place, only four or five palisaded houses, a guardhouse and a cabin which serves as a storehouse. [13]

La Harpe indicated that the Law colony was situated approximately three miles west by northwest of the post and that the expedition crossed a small stream to get there. The site of the concession was a "beautiful plain surrounded by fertile valleys and a little stream of fine clear wholesome water." [14] La Harpe found:

about forty-seven persons including Mr. Menard, Commander, and Labro [his son the magazine guard], a surgeon, and an apothecary.

Their works still consist of only a score of cabins poorly arranged and three acres of cleared ground. [15]

Sometime between La Harpe's departure from and return to the concession on April 28, the majority of colonists had abandoned the post. Deron de Artaquette, a company official, visited the concession one year later and observed the faltering colony:

there were only three miserable huts, fourteen Frenchmen and six negroes whom Sr. Dufresne, who is the director there for the company employs in clearing the land. [16]

Visiting the garrison later in the day, De Artaquette observed that the post contained only a hut for Commandant La Boulaye and a barn, that served as lodging for the soldiers stationed there.

Following dissolution of the concession, a garrison remained on the Arkansas until 1726. In that year, the Jesuits assumed responsibility for preserving the French alliance with the Quapaw, and Father Paul du Poisson traveled to the Arkansas. Apparently, the concession had been vacated since Du Poisson commented:

I was lodged in the house of the Company of Indies—which is the house of the commander when there is one here. [17]

Following the death of Du Poisson in 1728, the Arkansas was evidently abandoned. [18]

It is apparent from the previous discussion that three European landmarks were present on the Arkansas from 1721-1728:

1) A factory or warehouse at the Quapaw village of Ouyapes on the Mississippi;

2) A French garrison that occupied a site on the north bank of the Arkansas across from the Quapaw village of Assotoue/Zautoouys. The location of the garrison was apparently the same as that occupied by De Tonti's 1686 post and;

3) The Law colony that was about one league or three miles from the post. Depending upon which account is used, the colony was either northeast or west by northwest of the post.

POST #3 (1732-1751)

Lieutenant Coulange and 12 men came to the Arkansas in 1732 and selected a site on the north bank about 12 miles from the mouth of the river. One account suggests that Coulange occupied the same site as had La Boulaye and De Tonti before him. [19] By 1734, the works constructed were described as:

a wooden house on sleepers thirty-two feet long by eighteen feet wide, roofed with bark, consisting of three rooms on the ground floor, one of which has a fireplace, the floors and ceilings of cyprus, a powder magazine built of wood on sleepers ten feet long and eight feet wide, a prison built of posts driven into the ground, roofed with bark, ten feet long by eight feet wide, and a building which serves as a barracks, also of posts driven into the ground forty feet long by sixteen feet wide, roofed with bark. [20]

Father Vitry recorded this description in 1738:

The fort is small; a larger one [is] not needed for the twelve men who are there commanded by an officer. A few Frenchmen attracted by the hope of trade with the Indians are settled nearby.

The missionary is a Jesuit [Father Avond]. The lodging of the father is a makeshift hut; the walls are made of split log, the roof of cyprus bark, and the chimney of mud, mixed with dry grass which is the straw of the country. I have lived elsewhere in such dwellings but nowhere did I have so much fresh air. The house is full of cracks from top to bottom. [21]

In 1751, Captain De La Houssaye assumed command of the post. Since the habitant village had been attacked by Chickasaw Indians two years earlier, La Houssaye moved the post to a more easily defended location. [22]

POST #4 (1751-1756)

According to La Houssaye, the site selected for the new post was on the north bank of the Arkansas about forty-five miles above the mouth of the river. [23] This site is within the boundaries of the present Arkansas Post National Memorial. Apparently, construction of the post was initiated in October, 1751, but may not have been completed until 1755. A description and valuation of the post reveals that on completion, the fort was enclosed by an 11-foot high wall of double stakes, 720 feet in length. Platforms for cannon batteries were set in the angles formed by three bastions. Inside the fort, a number of buildings were constructed including a commanding officer's quarter, barracks, an oven, magazine, and latrines. Another building contained rooms of the storekeeper and interpreter, and housed the hospital and storehouse. A prison was constructed beneath a cannon platform in one of the bastions. Ultimately this location proved to be too inaccessible for boat traffic on the Mississippi River. As a result, the post was moved in 1756. [24]

POST #5 (1756-1779)

A 1766 account found the fort located:

a few miles from the mouth of the river [Arkansas], [opposite which is an island 15 miles long] in the neighborhood of the Indian village. [25]

Shortly before Spain assumed control of Louisiana, British Captain Philip Pittman made an inspection of French forts and settlements throughout the province. Of Arkansas Post, Pittman said:

the fort is situated three leagues [nine miles] up the river Arkansas, and is built with stockades in a quadrangular form. The sides of the exterior polygon are about 180 feet, and one 3-pounder is mounted in the flanks and faces of each bastion. The buildings within the fort are: a barracks with three rooms for soldiers, commanding officer's house, a powder magazine for provisions, and an apartment for the commissary, all of which are in ruinous condition. The fort stands about 200 yards from the waterside, and is garrisoned by a captain, a lieutenant, and French soldiers, including sergeants and corporals. There are eight houses without the fort occupied by as many families, who have cleared the land about 900 yards in depth. [26]

In 1776, Captain Balthasar de Villiers assumed command of the post. In 1778, a particularly damaging flood, a problem that plagued the post since its removal in 1756, prompted De Villiers to request a change in location. De Villiers favored two former post sites: the bank of Lake Dumond and Ecores Rouges or Red Bluffs. When it was learned that the river had separated from the former site at Lake Dumond, however, De Villiers requested that the post be relocated at Ecores Rouges. It was reasoned that this location was more easily defended and, being above the forks where the White River entered the Arkansas, would be more effective in keeping British hunters out of the district. Furthermore, De Villiers believed that river traffic had slowed so much by 1777 that a site near the Mississippi was no longer a necessity. The request cleared official channels, and the post was relocated in 1779. [27]

In 1882, Dr. Edward Palmer identified the site of Arkansas Post (1756-1779). In 1971, University of Arkansas archeologist Burney B. McClurkan rediscovered this location. Unfortunately, before an in-depth investigation could be undertaken, the Arkansas River overflowed its banks, as it had so many times before, destroying most if not all of the site. [28]

POST #6 (1779-1792)

On March 16, 1779, Commandant Balthazar de Villiers reported that the move to Ecores Rouges or Red Bluffs had been accomplished. The site of the new settlement he described as three hills adjacent to the river. On the first hill ascending the river, some Quapaw Indians had already settled. On the second hill, De Villiers located a number of Anglo-American refugee families, and on the third hill he placed the Franco-Spanish families and projected a fort. Construction of the fort progressed slowly. By July, 1781, the fort was finally completed. De Villiers described the finished work:

It is made of red oak stakes thirteen feet high, with diameters of 10 to 15 or 16 inches split in two and reinforced by similar stockades to a height of six feet and a banquette of two feet. Thus, I have built a reinforced stockade around all the necessary places, including a house 45 feet long and 15 feet wide, and a storehouse, both serving to lodge my troops, and around several smaller buildings, all of them built at my own expense when I arrived here. The openings for the cannon and swivel guns are covered with sliding panels which are bullet-proof. [29]

De Villiers first used the title "Fort Carlos III," to refer to this post in a letter of December 24, 1779, to Governor Jose Galvez. [30]

In 1787, four rises of the river had badly eroded the bank under Fort Carlos III. By the end of the year, only 18 inches of overhanging esplanade remained, forcing Commandant Valliere to remove the artillery. In February, 1788, another rise of the river tore away a bastion and by March the stockade wall nearest the river slipped down the bank. By the end of the year, little remained of Fort Carlos III, and the garrison was forced to quarter beyond the ruined enclosure. In spite of Valliere's frequent complaints to the governor, a lack of funds delayed construction for almost two years. On July 20, 1790, Captain Ignace Delino de Chalmette assumed command of the garrison. Shortly afterward, the citizens of the post presented him with a memorial soliciting a new fort through which they offered to supply stakes for a stockade. De Chalmette purveyed this most recent request to the governor and on January 20, 1791, permission to rebuild the fort was granted. [31]

POST #7 (1792-1812)

After receiving permission to rebuild the fort, Commandant De Chalmette selected a new location next to the habitant's fields within a cannon shot of the village. On March 1, 1792, De Chalmette took possession of the new fort and named it San Esteban after the governor's given name. [32]

In February, 1793, the commander of the Spanish ship, La Fleche, described Fort San Esteban:

the fort of Arkansas is situated in the middle of a hill that overlooks the Arkansas River. The fort is surrounded by round stakes of white oak protected against carbine shots. It has a bastion on the east and another on the west in which are mounted a cannon of four and two swivel guns. In the fort there is a house, barracks, and a ware house covered with shingles. Above the fort there are about thirty houses, with galleries around covered with shingles, which form two streets. Below the fort there are about a dozen quite pretty plots of four by four arpents [44x44 feet], where there are very beautiful fields. [33]

In 1796 French General Victor Collot, far less impressed than the commander of La Fleche had been, described the fort as:

two ill-constructed huts, situated on the left, at a distance of seventy-five miles from the river of Arkansas, surrounded with great palisades, without a ditch or parapet, and containing four six-pounders, bear the name of fort. [34]

On July 22, 1802, Commandant Carlos de Villemont transferred possession of the post to Captain Francisco Caso y Luengo. The inventory made at the time of this transfer listed the buildings and artillery of the fort in good condition. In 1803, the United States purchased Louisiana from Napolean Bonaparte, emperor of France. In January, 1802, Marques de Casa Calvo, in charge of the Spanish evacuation, ordered Caso y Luengo to transfer the post to United States representative James B. Many. As with any change of command, both men prepared an inventory of the fort, dated March 23, 1804, that listed the following structures and their condition:

-One barrack 50 feet long by 10 feet wide, covered with shingles, flanked on top with a double clay chimney and at the end a division which is used as a prison.

-A kitchen for the commandant 20 feet long by 12 feet broad covered with shingles with a division for the war supplies. It is in a poor condition throughout.

-An earthen oven near the fort in normal condition.

-Three sentry boxes in poor condition.

-One flag staff in good condition. The locks, keys, hinges, latches, respectively, for each building in normal order. [35]

American captain George B. Armistead regarrisoned the post with 16 American troops. [36] Fort San Esteban, thereafter known as Fort Madison, maintained a garrison until the outbreak of the War of 1812. [37] Apparently, remnants of Fort Madison were visible in 1819 when William Woodruff visited the site and found that "no fort was standing, but there were some palisades." A somewhat contradictory observation was made by Daniel T. Witter in the same year:

I in the company with several gentlemen, went out to look at the old fort. Gov. Miller was one of the party. We found a large unfinished building, built of hewn logs and intended as a sort of block house. It had the appearance of not having been built long before that date and I learned from Gen. Allen, who was one of the party, that U.S. troops had been stationed there not long before, under the command of Major Armistead. I saw no walls or breastworks and presume it was intended for what in military parlence [sic.] is called "Cantonment." There were no troops there at that time and probably had not been for some 3 or 4 years. [38]

During preliminary test excavations at Arkansas Post, National Park Service archeologist Preston Holder identified what he believed was the stockade of Fort Carlos III or Fort San Esteban. Holder's conclusion was based on limited evidence and has since been refuted by William A. Westbury, Southern Methodist University archeologist. [39] It is evident from historical documentation that Fort Carlos III was undermined by the river, and historian Edwin C. Bearss has suggested the same fate for Fort San Esteban/Madison. [40]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

arpo/history/app2.htm

Last Updated: 13-Feb-2006