|

Aztec Ruins National Monument New Mexico |

|

NPS photo | |

From the late 1000s to the late 1200s, ancestral Pueblo people at Aztec planned and built a settlement that included large public buildings, smaller structures, earthworks, and ceremonial buildings. Aztec's extended community rivaled Chaco Canyon, 55 miles south, where a network of structures flourished between 850 and 1130.

Aztec's first inhabitants were influenced by Chaco architecture, ceramics, and ceremonial life. At first Aztec may have been a place that supported Chaco activities. Later it may have been a center in its own right when Chaco Canyon's regional influence waned after 1100.

Aztec's population ebbed at times but persisted through cycles of drought and cultural changes. Even after many generations, the community's final layout adhered to a master plan set out by the first builders. The people left in the late 1200s, leaving well-preserved structures and artifacts that tell their stories. Today many Southwest tribes, descendants of the ancestral Pueblo people of Aztec, maintain cultural and spiritual ties to this site.

An Ancestral Community

The River Gives Life Rising in the San Juan Mountains to the north, the Animas River flows across the plains of northwestern New Mexico. Near today's city of Aztec, early farmers took advantage of the river's year-round water. Ancestral Pueblo people had long lived in the Four Corners region, and sometime late in the 1000s a group began building a large complex overlooking the river.

When construction ceased in the late 1200s, the community consisted of great houses, tri-walled kivas, small residential pueblos, earthworks, roads, and great kivas. The formal layout of the settlement, purposeful landscape modifications, and the orientation and visual relationships among the buildings indicate a grand design. Over 200 years it reached its final expression, long after the blueprint was conceived and building began.

Most prominent are the great houses—well planned, public buildings of many connected rooms surrounding a central plaza. Construction of larger great houses followed. By 1105 the people began harvesting wood from distant sources to build the largest structure, now known as West Ruin. After two episodes of stockpiling timber followed by intense construction, this great house took its final form by 1130.

Architecture on a Grand Scale The West Ruin resembled the great houses built at Chaco and elsewhere in the Southwest. The three-story building had over 500 rooms and many kivas—circular ceremonial chambers—including a great kiva in the plaza that was used for community events. The thick, tapering walls had a core of roughly shaped stones and mud mortar sandwiched between sandstone masonry exteriors.

Building continued over the next 150 years on East Ruin, a great house of similar construction and layout as West Ruin. They raised walls for scores of smaller structures and sculpted the landscape. Earth pedestals elevated larger buildings, berms marked the space surrounding them, and linear features on the ground, called roads, radiated across the area. In its early years the settlement was marked by a strong Chacoan influence, and it prospered as a regional administrative, trade, and ceremonial center. Later, despite periodic droughts and the decline of the Chacoan social and economic system, Aztec's regional prominence persisted as construction and remodeling continued in the Chacoan style.

Moving On By the late 1200s people had moved from Aztec and the Four Corners region. Why did they leave? Perhaps it was drought or social, religious, or political issues. Maybe it was the allure of distant places. They moved south to the better-watered country of the Rio Grande drainage and west into Arizona, where their descendants live today. But this site is not forgotten. Many American Indians maintain deep spiritual ties with this ancestral place through oral tradition, prayer, and ceremony.

Pottery Styles Over Time

The style of pottery vessels reflect changing cultural influences on a population. The first inhabitants made or traded pottery similar to ware found at Chaco Canyon. The pitcher with the human effigy, the bowl with lug handles, and the black bowl, represent pottery styles from the first Aztec inhabitants. This style is often characterized by tapered rims and hatched designs in mineral paint.

Items found in later deposits are of a style made throughout the San Juan Basin after 1200. The bowl, kiva jar, mug, and canteens are examples of the craft practiced by Aztec's later people. They are identified by solid designs drawn in vegetable paint, square rims, and thick, heavily polished walls.

Excavating the Ruins

Why Aztec? Don't be fooled by the name. These structures were not built by the Aztec Indians of central Mexico but by ancestral Pueblo people who lived here centuries before the Aztec empire prospered. Inspired by popular histories about Cortez's conquest of Mexico, and thinking that the Aztec built these structures, Anglo settlers named the place Aztec.

In 1859 geologist Dr. John S. Newberry, the first recorded visitor at Aztec, found West Ruin in a fair state of preservation, with walls 25 feet high in places and many rooms undisturbed. From the rubble he concluded that a large population had once lived here. Fortunately, Newberry recorded much of the site before it was looted over the next 50 years.

When anthropologist Lewis H. Morgan investigated the site in 1878, he estimated that a quarter of the pueblo's stones had been carted away by settlers for building material. A few years later a local teacher and his students found things their predecessors had missed, including a room with human burials and well-preserved objects. Artifacts soon vanished as others broke into rooms untouched for centuries. Not until 1889, when West Ruin passed into private ownership, did the site become relatively safe from looting.

In 1916 New York's American Museum of Natural History began sponsoring excavations. Earl H. Morris, age 25, headed the first dig at Aztec. He spent the next seven seasons excavating and stabilizing West Ruin, the Great Kiva, and a few rooms in the East Ruin. In the 1930s Morris supervised the reconstruction of the Great Kiva.

In 1923, to preserve this valuable site. Congress designated it Aztec Ruins National Monument. In 1987 it was declared a World Heritage Site.

Remarkable Ruins

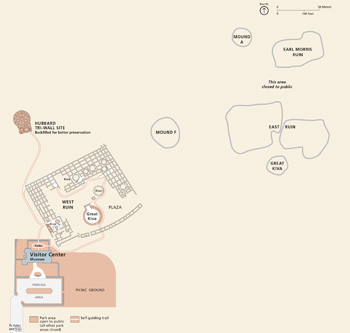

(click for larger map) |

The number, variety, and massive scale ot the structures concentrated in this small area are remarkable. Along with the large features are remnants of smaller buildings, roads, earthworks, and kivas.

The placement, orientation, and relationship of these features suggest that the initial builders carefully planned the community and that succeeding generations kept to the plan.

West Ruin The largest of the houses had at least 500 rooms that rose to three stories. It was a public building—akin to modern public monuments, civic centers, or places of worship. Excavation revealed original roofs with centuries-old wood and vast deposits of well-preserved artifacts left by the ancestral Pueblo people.

Hubbard Tri-Wall Site One of a few tri-wall structures in the Southwest, it was built of three concentric walls divided into 22 rooms encircling a kiva. This complex stood atop two earlier structures; one was adobe. Construction may date from the early 1100s.

Mound F and Mound A These tri-walled structures were almost twice the diameter of the Hubbard site. Mound F is the largest such structure in the Southwest.

East Ruin The Great Kiva in its central plaza is larger than the kiva in West Ruin.

Earl Morris Ruin Little is known about this site. Morris, the archeologist, may have run tests on the site, but he left no record of his findings.

Planning Your Visit

Getting Here The park is in the city of Aztec, N. Mex. near the junction of U.S. 550 and Aztec Blvd. (N. Mex. 516).

Visitor Center Start here for information, publications, and exhibits. It is open 8 am to 5 pm daily, with longer hours in summer. The park is closed Thanksgiving Day, December 25, and January 1.

Activities A self-guiding trail leads to West Ruin and the Hubbard Tri-Wall Site. The other ruins are closed to the public. For information about activities and programs, contact the park or visit www.nps.gov/azru.

Safety First Watch out for uneven steps and surfaces, ice or mud, low doorways, and dim lighting. Stay on the surfaced trail. Do not climb on ruin walls. All natural and cultural resources are protected by federal law.

Source: NPS Brochure (2018)

Documents

A Conservation Study of an Anasazi Earthen Mural at Aztec Ruins National Monument (Mima Eliana Goldberger, 1992)

An Archeological Reconnaissance of a Late Bonito Phase Occupation near Aztec Ruins National Monument, New Mexico (John R. Stein and Peter J. McKenna, 1988)

Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History: Volume XXVI (1928)

The Aztec Ruin Part I (Earl H. Morris, 1919)

The House of the Great Kiva at the Aztec Ruin Part II (Earl H. Morris, 1921)

Burials in the Aztec Ruin Part III (Earl H. Morris, 1924)

The Aztec Ruin Annex Part IV (Earl H. Morris, 1924)

Notes on the Excavations in the Aztec Ruins Part V (Earl H. Morris, 1928)

Aztec Ruins National Monument: Administrative History of an Archeological Preserve (HTML edition) (Robert H. Lister and Florence C. Lister, 1990)

Circular Relating to Historic and Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest and Their Preservation (Edgar L. Hewitt, 1904)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Historical Vernacular Landscape (2005)

Excavation of a Portion of the East Ruins, Aztec Ruins National Monument, New Mexico (HTML edition) (Roland Richert, 1964, reprint 1975)

Foundation Document, Aztec Ruins National Monument, New Mexico (August 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Aztec Ruins National Monument, New Mexico (February 2016)

General Management Plan, Development Concept Plan: Aztec Ruins National Monument, New Mexico (September 1989)

General Management Plan and Environmental Assessment, Aztec Ruins National Monument, New Mexico (February 2010)

Geological Resources Inventory Report, Aztec Ruins National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR-2016/1245 (Katie KellerLynn, July 2016)

Historic Handbook #36: Aztec Ruins National Monument (John M. Corbett, 1962)

Historic Structures Preservation Guide, Aztec Ruins National Monument (Stephen E. Adams, January 3, 1983)

Historic Vernacular Landscape: Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Aztec Ruins National Monument (2005)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Aztec Ruins Administration Building/Museum (Janene Caywood and Ann Huber, May 17, 1996)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Aztec Ruins National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SCPN/NRR-2019/1984 (Lisa Baril, Kimberly Struthers and Mark Brunson, August 2019)

Park Newspaper (InterPARK Messenger): c1990s • 1992

Plants in the Region of Aztec Ruins National Monument (Ora M. Clark, April 6, 1950)

Relocate Ruins Road Environmental Assessment (2002)

Resource Management Plan, Aztec Ruins National Monument (1996)

Ruins Preservation Guide, Aztec Ruins National Monument Active Working Edition (Stephen E. Adams, February 1979)

Salmon Pueblo Archaeological Research Collection

The Hubbard Site and Other Tri-Wall Structures in New Mexico and Colorado Archeological Research Series No. 5 (R. Gordon Vivian, 1959)

Vegetation Management and Cultural Landscape Preservation Maintenance Plan/Environmental Assessment (December 2012)

azru/index.htm

Last Updated: 25-Feb-2025