|

Big Bend

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 4:

A Dream in Waiting: Promotion of a Land Base for Big Bend National Park, 1936

Momentum towards establishment of Big Bend National Park, so apparent in the critical year of 1935, led park promoters and NPS officials to expect more good fortune in their quest to acquire over 1,200 square miles of land. With congressional approval in hand, the park service and Brewster County chamber of commerce anticipated in 1936 a year of intense coverage to gain public support and state legislative authorization in the biennial session of 1937. Then the surprising veto that year by Governor James Allred of state house speaker Coke Stevenson's park purchase bill stalled the ambitions of NPS and local park champions alike. From this ensued a laborious process to generate private donations of money and lands that challenged all who had dreamed in 1935 of creation of Texas's first national park.

Throughout 1935, Everett Townsend had traversed the haunting landscape of the Big Bend country to study land ownership patterns and potential costs for state acquisition. He had discovered much about the status of property in the area, and in January of that year had warned NPS and state officials that the process would not be easy. In addition to the 150,000 acres owned outright by Texas, the Lone Star state, said Townsend, "has an equity in probably 60 or 65% of the remainder of the lands that will be within the boundary designated by the National Park Service." Along with these lands came state claims to the mineral rights beneath them. Townsend explained that "these lands were sold to the Original Grantees on terms which permitted the payment of 1/40 of the principal at the time of purchase." Then the new owners faced "deferred payments to be extended over a period of forty years, bearing interest at the rate of 3%." Very few of the owners of these lands had paid in full, and "in most cases none of the principal has been paid and the individual owes to the State the entire 39/40." Because of the lack of concern by state and local officials about the condition of ownership, said Townsend, "in times past these lands have frequently changed hands between individuals by the simple process of the purchaser paying the seller a bonus per acre and assuming the obligations due the State." [1]

Knowing the land and its owners as he did, and conscious of Texas's lack of familiarity with federal land law, Townsend recommended to the state and NPS that an elaborate system of surveying and purchasing be implemented. He wrote that "an appropriation of a sum sufficient to pay the bonus price to the owners of State Land and to buy the patented land (35 or 40% of the total acreage) should be asked of the legislature." In addition, "an appropriation to compensate the State Public School Fund for the surface and mineral rights to all State or school lands should be asked also of the legislature." Townsend once more dismissed claims of mineral wealth in the Big Bend country, as "the whole area has been prospected for more than fifty years and there seems little likelihood of any considerable minerals (either hard or petroleum) being found within the region." Further, said Townsend, "it is a well known fact that minerals can be more safely stored underneath the ground in their native elements than by any other method devised by man." He also noted that "the markets for most minerals are glutted today, because of over production." Townsend thus sought to "reaffirm that if any [minerals] do exist there they will be securely stored to be scientifically developed should the need ever arise for them." A similar case could be made for terminating leases for cattle grazing. "The poor grazing quality on the surface," he reported, meant that "it will take seventy five to one hundred acres per cow or horse." Big Bend ranchers also suffered from the fact that "there are many 640 acre tracts that will not support one animal through the year." With the NPS spending "vast sums in the development of the Park area," the "additional consumption of gasoline in Texas" by motoring tourists, and the potential for visitation to an international park someday, Lone Star legislators would do well to accept the gift extended by the U.S. Congress and prepare for land acquisition soon. [2]

Following upon his recommendations, Townsend by 1936 had developed a classification system for the 643,115 acres of privately owned land in the Big Bend area. If a landowner had managed to secure good pasture and water, he or she could anticipate earning anywhere from one dollar to ten dollars per acre in a sale to the state. These ranchers and farmers also were the most conscientious in their payment of property taxes. These "Class I" lands comprised 286,094 acres, or 44 percent of the private property needed for the park. Townsend's "Class II" lands were "owned by non-residents in quantities of two surveys or more each." All of these 228,832 acres (or 35 percent of the park area) were "unimproved and minus water with rare exceptions." Townsend also noted that "several years taxes are due on some of the patented land," while "much of the Public School land is far in arrears for interest due on unpaid principals and for State, County, and School taxes." These lands, estimated Townsend, would be worth only one dollar to $1.50 per acre. Finally, his "Class III" acreage (128,189 acres, or 20 percent of the park) was "owned by non-residents in quantities of less than two surveys each." Like Class II lands, these properties had little water and few improvements. In this category Townsend discovered that "the greater number of patented surveys and some of the Public Schools [lands] have been sub-divided and many individuals own tracts of less than one acre each." Predicted Townsend: "It will be more difficult to contact these numerous owners and make purchases." Thus he recommended that the state "place a higher valuation" on this property ($2.50 per acre). He encouraged such generosity, even though "some of it [the land] will probably be forfeited (sale cancelled) for non-payment of the interest to the School Fund." Finally, Townsend cautioned that "careful resurveying of the whole region may result in reducing the totals by about 12,000 to 13,000 acres." [3]

Upon completion of his work in 1936, Townsend had learned that the NPS and Texas State Parks Board would need to examine some 1,179 land surveys, amounting to 788,683.75 acres. Absentee owners claimed the largest individual parcels, with the Texas and Pacific Railway in control of 41,600 acres. Of ranchers living on their lands in the Big Bend country, Townsend identified Homer Wilson in the Chisos Basin as the largest single owner (at 30,149.5 acres). The Cartledge family, possessors of three parcels in the Castolon/Santa Elena area, owned 30,817 acres jointly. Other local ranchers with spreads in excess of 10,000 acres were Boye Babb (10,891 acres), Sam R. Nail (11,842.5 acres), W.E. Simpson (14,080 acres), J.J. Willis (25,232 acres), and a ranch owned by "Herring and Johnson" (23,040 acres). In all, Townsend named 82 individual or family owners of property residing in the future Big Bend National Park (or having what Townsend called "local ties), of whom thirteen (or one-sixth) were Hispanic. The most prosperous Hispanic rancher was R.A. Serna, with 3,840 acres, while a woman named Juana Hernandez of Terlingua was reported to have 1,280 acres (two sections), the use of which Townsend identified as "farm and home." Of note also was the fact that none of the thirteen Hispanic landowners were delinquent in their tax payments, while the Odessa auto dealer Willis owed back taxes on all of his properties. [4]

Big Bend's future depended most heavily, its sponsors thought, upon the Texas state legislature to appropriate the monies necessary for the direct purchase of the acreage surveyed by Everett Townsend. But the delay between legislative sessions meant that the year 1936 would not see action on any park bill. Instead, promoters engaged in a series of publicity ventures designed to inform Lone Star residents of the value of Big Bend to their future. In March 1936, Herbert Maier wrote to Conrad Wirth to seek advice about "the value of motion picture and lecture publicity" for the park. Maier knew of earlier efforts to film in the Big Bend area, and recommended that the park service "have a man make the Chambers of Commerce, Rotary and Kiwanis Clubs, churches and schools in the State, especially the more thickly populated part." In so doing, said the ECW regional officer, ""public opinion would swing in favor of acquisition and the latter would be greatly hastened." [5]

Stimulating Maier's interest in media productions on Big Bend was the visit in March by George Grant, chief photographer for the NPS. Grant traveled throughout the future park, and crossed into Mexico with Everett Townsend to document the wonders of the Fronteriza Mountains. The NPS hoped to use Grant's images in an upcoming display at the Texas Centennial festivities in Dallas, and with a presentation that Maier and other park service officials planned in Mexico City later that year. "Since the Mexican area has never been photographed," Maier told Wirth, "I think it will be a very fine thing if Grant can bring back a complete collection." One reason for the necessity to keep Grant in the field was that "[W.D.] Smithers, the photographer at Alpine, who has such a wonderful and the only collection of Big Bend pictures, has had difficulty with the State Parks Board, and is leaving Alpine." Smithers' unhappiness led him to "lock up his negatives," denying their use to the NPS "nor to anyone else." Grant considered this latter decision by Smithers as tragic, as he informed Maier: "I think this Big Bend project is the most important thing we [the park service] have on the docket at the present time." He found "the Big Bend country to be as big as Yellowstone [National Park] and even more varied." The ruggedness of the terrain, and the isolation of the CCC camp, led Grant to complain that "the way I am working at present . . . is not practical to do any justice to this area." This he attributed to "dust storms, rain, wind and many other conditions that make good photography impossible at this time of the year." The NPS photographer sought "encouragement from both you [Maier] and Wirth," as "under present conditions here it seems too much of a waste of time to stay here indefinitely." [6]

Townsend's service to George Grant, along with his earlier work in land title research, led Maier to ask the former Texas Ranger to travel to Austin upon returning from the photographic survey to "undertake an investigation of the present land ownership status of the various Texas park areas in which the CCC has undertaken, has completed, or is undertaking developments." Maier nominated Townsend for this task because Washington officials of the NPS had learned of the displeasure expressed by Pat Neff, chairman of the Texas State Parks Board, who in Maier's words "is especially sensitive when any subject involving honest dealing is concerned." The parks board "no longer has an attorney," Maier reported, and "since the investigation is up to us the only man who could undertake it without serious conflict is Mr. Townsend." The departure of D.C. Colp as parks board director had been acrimonious, and "you can realize that Mr. Colp left that sort of thing, undoubtedly, in a very questionable state." Besides not having legal counsel, the board lacked funds "for carrying on lengthy title investigations." Thus Maier had advised Townsend "to go into the investigation of each area to only a reasonable degree so that the National Park Service will be reasonably protected if questions regarding this matter arise." [7]

Townsend's research of all Texas CCC property acquisitions dramatized the complexity of politics, economics, and history that affected Big Bend. He discovered that "there is no certificate filed by the State Land Commissioner showing transfer of all school land within that area." Townsend thus advised Colonel R.O. Whiteaker, chief engineer for the state parks board, that "such certificate should be requested from the Land Commissioner or in lieu thereof, some other acknowledgement of the transfer of these lands." He had learned that Whiteaker "had prepared two hundred and thirteen (213) deeds of such character covering the same number of tax suits and sales to the State, but these deeds have not been signed by the [Brewster County] sheriff." Townsend believed that "the rather high costs . . . of completing these deeds has deterred further progress in that direction." He hoped that his friendships in Alpine would allow him to identify a notary public who would process all of the deeds "for a very nominal fee [$500]." Townsend's only concern was "whether or not the law will permit these two officials to charge less than the statutory fee for such services." [8]

The realities of Brewster County land acquisition continued to engage the attention of NPS officials as they planned for the 1937 Texas legislative session. J.W. Gilmer, owner of some 60,000 acres of land near the proposed park entrance at Persimmon Gap, wrote in May 1936 to Maier to offer the services of his "Big Bend Abstract Company." Gilmer claimed to have worked in the "land business" for a quarter-century, the past eight years of that in Alpine. "My knowledge of the park area," said Gilmer, "and having been interested in the park [ever] since it originated, and knowing the big job it will be to secure these lands, have prompted me in making application to your office for the job of assisting in the work." Even as Gilmer expressed optimism for the future of Big Bend, Maier and his NPS colleagues would read in the Dallas Morning News of May 18 the headline: "Chance of Big Bend Park Being National Domain Is Dwindling." Correspondent Alonzo Wasson reported that "those in a position to size up the prospect have become pessimistic with respect to the Big Bend Park project." Wasson cited "the large number of private ownerships within the boundaries of the school lands that were dedicated as a State park by act of the Legislature." Instead of trading their lands to the TSPB, local ranchers in possession of 200,000 acres "have announced they would part with their holdings only for cash." The Morning News claimed that "these owners are seized of a strong hunch that their lands are rich in minerals, and have graduated their prices by their high faiths." Given this obstructionism, wrote Wasson, "there seems no possibility that a solid block of such area as the Federal Government requires for establishing a national park can be pieced together." [9]

More troubling to Wasson, however, was "the recent dictum" of NPS director Arno B. Cammerer "that the gift if it was to be made acceptable to the Federal Government, would have to be freed from the operation of that provision of the act of the Legislature which, in offering the surface, reserved all minerals that might be found to underlie it." Wasson could find no language in the 1935 congressional edict authorizing Big Bend National Park that mandated such a concession, "but it is assumed that Cammerer speaks by the book in saying that the title to the surface must convey ownership also of whatever mineral wealth may be hidden beneath." The Lone Star state had sold school lands in the past "without reservation of the mineral estate," said the Morning News reporter, "and nearly every such sale sowed the seed of regret." Wasson could not imagine that the Texas lawmakers, "great and genuine as is the desire to see the Big Bend become a national park, could be persuaded to deed away a mineral prospect as promising as that which the geologists have declared is there presented." Since "there is no possibility that any Legislature . . . would comply with the terms set forth by Cammerer," Wasson predicted that "it looks as though the Big Bend Park is destined to remain a State park." Unless the NPS relented in their demands, "the Federal Government will have to content itself with the surface without all of anything there may be beneath." This meant that the 4,000 acres set aside for the CCC camp "will not measure up to the proportions of a national park, but . . . will make a sizable State park." [10]

Wasson's article sparked much debate among Big Bend sponsors in west Texas, the state capital at Austin, and within the park service. Horace Morelock of Sul Ross State Teachers College asked Maier how to present the NPS's version of the Big Bend land-acquisition story to several audiences that he would address. The "Highway 67 Association" had asked the Sul Ross president to speak on the importance of Big Bend National Park to their plans for a Dallas-to-Presidio route. "I am wondering if Wasson's article will be helpful or hurtful," asked Morelock, and he wanted advice on "what I should say to this group with references to his conclusions." More important to Morelock was his service on the executive board of the Texas State Teachers Association. "A good many people seem to think," Morelock informed Maier, "that the State Teachers Association of Texas will be the only stumbling block in the way to getting a deed to the school land." Morelock had asked the teachers board to come to the Big Bend area to "make a personal investigation as to the intrinsic value of school land." For his presentation to the executive committee in Fort Worth on June 6, Morelock had hoped to emphasize how "the money to be derived from the sale of gasoline . . . which would go to the school fund would be worth much more to the public schools of Texas than they would ever get out of the land." Yet the Morning News article had highlighted the way in which "the mineral rights have crept into the picture." As rumors spread that Governor Allred might ask for a special (or "call") session of the legislature, one that could address the land questions for Big Bend, Morelock wanted the NPS to assuage the doubts of the teachers executive board, with a personal appearance by Maier the most effective means to accomplish this. [11]

Echoing the sentiments of Morelock was Everett Townsend, who saw the Wasson piece as a critical juncture in negotiations with the state legislature. The long-time champion of a national park in Brewster County asked Maier to attend the Fort Worth convention of the state teachers association because the Morning News had its facts wrong about mineral deposits in the park area. "After a careful survey," said Townsend, "the National Park Commission carefully excluded all known mineral lands from the designated area." Further, "the region embraced within the Park area has been diligently prospected by scientists as well as the 'grub staker' and nothing of any value has ever been found therein." Townsend conceded that "there is one exception to this last statement," as "a small quicksilver mine was operated for a few years at the north end of the Mariscal Mountain." Its prospectors found "no great sight of ore," and the site "has long been abandoned," even though "a thousand holes have dug all around it." Townsend concluded that "the more than fifty years of intensive prospecting has developed a thorough knowledge of all of the formations of the region," and "no one of scientific understanding expects minerals of value to be found there." Then Townsend got to the heart of the matter of school lands and mineral rights. "It has been my pleasure and my pain," he told Maier, "to be lined up with and against the school teachers of Texas." He knew "their weight as friends and as foes." Townsend advised Maier that "I want 'em on our side in this coming contest," as "with their help we will have little trouble in obtaining our objective." Once the teachers saw that "the whole program is so obviously in their favor they will not object to the ceding of a few hundred thousand acres of purely desert land." To sweeten the deal for the Texas school teachers, Townsend suggested that "as a great out-of-doors University preserved and cared for by the Government, [Big Bend] will be of much greater value to the schools than under the present status." [12]

The next step for local promoters of Big Bend was to contact the state teachers association to express their concerns over the mineral rights issue in general, and the Morning News story in particular. Morelock wrote to Lewis B. Cooper, director of the association's research department, to determine that organization's sentiments. "There are several angles to this whole situation," the Sul Ross president acknowledged, and he hoped to "present them from an impartial point of view." Like Townsend, Morelock saw as critical an awareness of the teachers group "of returns on [the] tourist trade to the Chisos Mountains in the event an International Park is established there." He referred to data generated by the New Mexico State Highway Department, which in 1935 had invested $30,000 to advertise tourism to the "Sunshine State." "Their tourist trade," said Morelock, "during that year increased to the extent of $11,000,000.00." In response to this windfall of visitation to the historic and natural wonders of New Mexico, that state would "spend this year $60,000.00 because of what they realized on the other investment." Morelock knew that "there is the feeling that since the University of Texas realized such returns on its oil lands in this section [east Texas], public school people are hoping they might get the same returns from the minerals of the Chisos Mountains." He asked Cooper to invite "the State geologists of Texas and the Government geologists who have made a study of this matter" to speak to the convention. In so doing, the teachers could gain "such information on State minerals as will best help them to proceed intelligently and in the best interests of the public schools." Morelock saw only good things resulting from such a thoughtful approach, as teachers would "realize [that] an International Park within [Texas's] borders . . . would produce for the public schools a revenue for all time to come." [13]

The level of anxiety displayed by the Big Bend sponsors prompted Herbert Maier to respond to Morelock's entreaties, counseling patience rather than panic. He apologized for declining their invitation to travel to Fort Worth for the teachers' convention, noting that "it was necessary that I be at the CCC Exhibit building at [the Texas Centennial in Dallas] that day, pulling it together for the opening." More importantly, Maier "felt reluctant to speak on two or three of the subjects suggested in Mr. Townsend's letter." From his wider angle of vision at the NPS, Maier recognized that "of course some opposition is to be expected before the Big Bend area finally becomes a National park." It was "a perfectly natural condition," as "very few areas, if any, have come into the National Park System without opposition from certain sources." Morelock also needed to know, said Maier, that "during the period preceding acquisition, the National Park Service may act in an advisory capacity, but it is not considered the best policy for field officers to take too active a hand in promotion." In regards to the issue of mineral rights, Maier warned once again (despite the Morning News story) that "the Federal Government cannot accept any land for National Park purposes unless both the surface and sub-surface rights are turned over in fee simple." He agreed with Morelock and Townsend that "it is not at all likely that minerals of any considerable economic value will ever be found in the area as outlined." Yet "we cannot expect this matter of the mineral rights to keep from creeping into the picture." He advised Morelock that "it is just as well for it to come to the front at the start, since it will probably prove to be the major stumbling block." Whatever the anxieties of the local interests, Maier declared: "I have no doubt in my mind but that it can be overcome." [14]

Maier's advice notwithstanding, Morelock and Townsend spent much of that summer appealing to state and local officials to resolve the mineral rights questions threatening land acquisition at Big Bend. Townsend informed Maier of his intentions to contact Coke Stevenson, speaker of the state house of representatives from the Hill Country town of Junction, and "probably the most [eminent] lawyer who is well versed in all of the laws pertaining to the School Lands of Texas." Morelock for his part appealed to L.A. Woods, superintendent of education for the state of Texas, to join a party visiting Big Bend that included "the President of the State Board of Education, . . . and the President of the State Teachers Association." This group could "inspect the ground in person, and be ready to make a report on this subject at the next Legislature." Ben F. Tisinger, the teachers' association president, had informed Morelock "that he planned to spend a part of his vacation in this section." If Woods could join the group, "the Chamber of Commerce here will be happy to take all three of you down to the Chisos Mountains for a personal inspection of the park area." [15]

The work of Morelock and Townsend to change attitudes about the public school lands met with some success in July 1936. Maier contacted NPS officials in Washington with word that "one of the citizens in west Texas who is interested in the Big Bend area may be in a position to donate approximately 2000 acres within the proposed park boundaries to the Federal Government." Such a gesture, said Maier, would publicize "the idea that this will not only start the 'ball rolling,' but will result in an advantage to the National Park Service in that the latter can say that some land has already been donated for park purposes." Maier's hope was that "further donations may and probably would be made to supplement this acreage," and "quite a nucleus may be on hand in a short time, not so much for practical purposes, as for psychological effect." Maier conceded that "the Department of the Interior would probably not accept a fraction of the proposed area." Thus "the suggestion . . . might be made that the citizen in question should deed the land to the state now for future national park purposes, if and when the total acreage has been acquired and is ready for transfer." Yet the ECW regional director saw problems connected to the controversy over public school lands, and feared "that the donation of this acreage to the state in this case would be 'buried' and the action would have little salient effect." [16]

A breakthrough in the mineral rights controversy came in July 1936, when Maier wrote to Conrad Wirth about a decision by the Texas state attorney general. "It has now been definitely decided," said Maier, "that the School Fund can release its mineral rights but some reimbursement will have to be made." Maier was not sure "whether 25 [cents] per acre will be regarded as a gift, and nothing less than say a dollar per acre can be regarded as a sale." He expected the attorney general to resolve this detail soon, and thus proceeded to the more pressing question of legislation for the acquisition program. "I had Mr. Townsend in the office the past two days," Maier told Wirth, and "we went over the whole thing." Above all else, the two men agreed that "the State Representatives and Senators must be lined up in favor of the issuing of warrants for the purchase of the land." When they decided upon an amount to request of the Lone Star lawmakers, Maier estimated that "offhand I would says that only a million and a half dollars may be needed to handle the whole thing." The ECW's regional director then approached Wirth's superior, NPS director Arno Cammerer, for advice on taking a more aggressive and public stance on the land-acquisition matter. "I have been continually urged to appear before certain groups," he told Cammerer, "to explain to them how the School Fund will actually benefit by relinquishing its rights to the land." Such groups as the state teachers convention "have desired me to make rather definite statements on the approximate amount of money which the Federal Government will spend eventually on the development of the area." Maier knew that "for an employee of the National Park Service to do this may be out of line," yet he also believed that "it can be handled discreetly and without embarrassment." Thus Maier asked Cammerer to "be given permission to accept certain invitations where this seems advisable, and to work with them." He warned the NPS director that "it is quite possible that some criticism may result due to the strong emphasis on States Rights in Texas." Nonetheless, "the U.S. Forest Service recently has had considerable land in East Texas turned over to the Government for National Forest purposes." This indicated to Maier that NPS policy might need to change, as Texas slowly came to appreciate the benefits brought to the Lone Star state by federal land management agencies. [17]

Further advancing the cause of publicity for Big Bend was completion in August of a Texas travelogue, made by M.S. Leopold of the NPS's Motion Picture Production Section. Leopold sent an advance copy to Morelock and Townsend for their review, and planned to present the motion picture at the Texas Centennial in Dallas. Morelock found somewhat disturbing the decision by Leopold to cut out "the college scenes (including pioneer dance in Outdoor Theater, horseback riding, tennis and bowling, also a panorama of the town [of Alpine] taken from the grandstand of the Athletic Field)." Morelock considered these essential to any film about the region, as "Alpine is the open gateway to the Big Bend National Park, and the people of this section are not only expected to do all the work but to furnish practically all the money necessary to get this project before the people of Texas." In particular, "the college has taken an active part in this program," said the Sul Ross president, "and has spent both money and time to the end that the people of Texas might know about the wonderful scenery in the Chisos Mountains." Sul Ross also had "organized groups of students in attendance upon our Summer School from all parts of Texas for week-end trips down into the Chisos Mountains," so that "they might go home and tell their people about the advantages of this area for a national park." Claimed Morelock: "Naturally, when the college, as a part of this set-up, is excluded from the motion picture, it is difficult for us to maintain our enthusiasm." Especially galling to Morelock was the insistence of universities and colleges in Texas to be included in the NPS movie. "Of course," said Morelock, "the other institutions would like to capitalize through this picture [on] the opportunity to get before the people of Texas, but they have no valid claim on being a part of the Big Bend National Park." [18]

For Townsend, the Big Bend movie had other problems beyond the affront to Sul Ross and Alpine. "The film is very good," he told Maier, "but does not contain enough of the Park Area to attract the desired attention." Townsend had traveled with Leopold and the NPS film crew, and recalled that "we shot from the top of Boquillas Canyon, around the two Boquillas villages on both sides of the river, at Johnson's [Ranch], in Pine Canyon and Blue Creek." Unfortunately, said Townsend, "none of these are in the reel." He also remembered that "some good stuff was taken from the South Rim, which does not appear in the picture." Then he criticized rather sharply "the psychological effect [that] the showing of 'so much oil' may have upon the minds of our educational people." Local park sponsors had begun "a crusade to educate the school teachers of Texas to the idea of dedicating a great domain of school land together with all mineral rights, to the public for recreational purposes." Yet Leopold's story began with "an epitome of the vast oil resource of the State, scattered from one end of it to the other," and continued in that vein throughout the film. Townsend recognized that "it was correct to show the Gulf [Sulphur] Company's holdings and give them credit and praise for the production of the picture." Instead of a brief glimpse of Big Bend, however, Leopold should "call attention to [Texas's] lack of National Parks and then swing Colorado, Arizona, or California (one of these [that] have the most parks) onto the screen, show its park sites, and some of the vast crowds who flock to those places." Townsend had come to this realization after screening the film to the Alpine Lion's Club, whom the NPS had asked to critique the story line before release of some 40 to 50 reels of the film throughout Texas. Townsend told club members that "my objection to this picture is that it is made for the purpose of selling our Park to the very people who now have rich incomes from the oil industry." He found it problematic that the NPS would "go ahead and devote the first half of the reel to showing the resources of their great wealth," then asking them "to give half a million acres of undeveloped land" to the federal government for a park. [19]

Where Morelock's entreaties for scenes of his college campus failed to move the NPS, Townsend's more trenchant criticism led Herbert Maier to ask the Interior department's division of motion pictures to change the storyline and edit the footage. Maier informed Ellsworth C. Dent of the motion picture division that "it is too short, and furthermore, the first half of the reel is given over entirely to the benefits derived from exploitation of natural resources in Texas." The ECW regional director noted that "it is the opinion all around that it is most unfortunate that a reel designed to advocate the perpetuation of a primitive area is tied in as the tail to a kite to about a thousand feet of film depicting [oil development]." Maier could only conclude: "The whole thing, you will agree, is incongruous." While the NPS had little choice but to recognize the patronage of the Gulf Sulphur Company in the film's production, "the thing will by no means do for the need we hoped it might fill, since it may defeat our purpose." Maier hoped that Dent could prepare instead "a single reel . . . consisting entirely of Big Bend scenic subject matter." This version should eliminate "all of the Sulphur and helium material," as well as "the State Park subject." Maier noted that "the editor apparently intended to lead up to the Big Bend subject, but we feel that this film should step out immediately with a bang as to Big Bend country rather than that its final effectiveness should be softened by a gradual build-up." Target audiences for the Big Bend film included "Rotary, Kiwanis and [Lions] Clubs, church organizations, schools, etc." Equally important was a screening to take place that fall at the gathering in El Paso of Mexican and U.S. officials planning the international peace park. [20]

What had happened to the Big Bend film would repeat itself throughout the process of publicizing Texas' first national park: the differing perspectives of NPS officials in Washington, state officials in Austin, and local sponsors of the park. Herbert Maier would write in late August to Fanning Hearon of the Interior department's motion picture division, about the need to rethink the messages transmitted in the promotional venture. "I realize how the film may be viewed by Washington with an eye to its commendability," said Maier. Yet "if you were out here in the plains States," he told Hearon, "you would realize that the words 'oil' or 'mineral rights' are the most magical words in the English language, especially when dealing with school lands." Maier doubted "if there is any area in the world which has had a parallel experience with that of Texas." Recalling the history of public land sales in the Lone Star state, Maier noted that "as far as the settlers in many parts of Texas knew, until very recently, there was not a remote possibility of mineral deposits on their land." Then "in the early '20's somebody invented the core drill," said the ECW regional director, "which was capable of going down 6000 to 8000 feet." Such advances in technology revealed "immense oil-bearing deposits . . . at this level and below." "Subsequently," said Maier, "the Public School Fund which held tremendous but apparently valueless acreages suddenly found itself on Wall Street, and the University of Texas overnight became the wealthiest university in the World." As a result, Maier told Hearon, "the probability of mineral deposits of all kinds has been indelibly impressed upon the minds of all Texans for the duration of the human race (or at least for the duration of the ECW)." [21]

Maier's appeal to Hearon included the caution that "from the standpoint of a Texan, the Leopold film would appear to have been designed to defeat its own purpose." Knowing of the heavy workload facing Hearon's motion picture division, Maier asked that he "send us a sample print of the strip, or a reel of all the scenes of the Big Bend you have available." The ECW had "access to a motion picture laboratory nearby," and could "run off the various scenes and cut those we feel desirable and splice same in the order that we feel best." Hearon accepted Maier's offer, submitting to the ECW official the work print of the Big Bend film, along with "nearly 2000 extra feet of Big Bend scenes made by cameramen of this Division and the cameramen [who] did the Gulf Sulphur job." Hearon advised Maier to "do what you like with the extra footage, arranging it as you want it to appear in the special Big Bend production and indicating any titles you want used." He did, however, warn Maier that "we must ask that the work print of the Gulf Sulphur subject be left untouched." Hearon further cautioned: "Despite how enthusiastic you and the Texas people may become, it has been our experience that one-reel subjects are much easier to handle and much more effective." His willingness to accommodate the editing request from Maier resulted from a preliminary advertisement of the picture by the Interior department. "You will be interested to hear," Hearon informed Maier, "that requests for the original Big Bend picture are more than double the amount of prints available in this Division and at the Pittsburgh office of the [U.S.] Bureau of Mines." [22]

A promotional film that spoke to the perceptions and concerns of Texas audiences came none too soon for the NPS and local park promoters, as Governor Allred had indeed announced a special session of the Texas legislature. Everett Townsend spoke with house speaker Coke Stevenson, who suggested that the Big Bend sponsors delay any request for financial assistance. One reason, said Townsend to Maier, was that "fifty percent of the new house are new members." Stevenson thought it more prudent to approach the legislature in January, when the freshmen members had taken their seats. Yet Townsend continued to canvass legislators about the merits of the Big Bend project. He offered to coordinate more trips to the park area by state lawmakers, and asked whether the NPS could support his lobbying efforts and research into school lands records while in Austin. Herbert Maier worried that "all travel incurred by anyone connected with the State Park Commission, directly or indirectly, of Texas, should be borne by the State Park Commission." Yet Townsend had "been with us too long not to know where you need to exercise discretion." Maier acknowledged that "both you and I are so zealously imbued with the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps in the Big Bend area that we are willing and prepared to meet any expectations which the General Accounting Office may take in our expense account from our personal pockets." The ECW officer informed Townsend that "I am with you a hundred percent in putting across the Big Bend National Park as an outstanding monument to the efforts of the CCC, even if it calls upon me personally 'as a Californian and a Texan' to meet exceptions of the General Accounting Office." He believed that Townsend's lobbying and research work was "justifiable in the consummation of the CCC endeavor in the Big Bend in Texas." [23]

While Townsend worked the halls of the Texas legislature on behalf of the NPS, Maier prepared top officials of the park service for discussion of the land-acquisition program while in El Paso for the international park conference. To Conrad Wirth, Maier noted that the actual purchase price for the 643,115 acres of private lands would not be onerous (an average of two dollars per acre), and that the campaign to influence the opinions of the Texas school teachers' association had gained momentum. "As it now stands," said Maier, "the School Fund receives 1 [cent] of the 4 [cent] tax on gasoline." The NPS, which earlier in the year had dismissed the uniqueness of the school lands issue, accepted the fact that "the School Fund now has before it the impressive precedent of having suddenly discovered in 1924 that its 'worthless' school lands in the eastern part of the State contained oil deposits." Not only had the Austin campus become richly endowed from the revenues, but "the School Fund as a result of this also carries a surplus running into several million dollars." The ECW official reported that "it is planned to introduce a bill in the coming State legislative session in January, calling for authorization to purchase the private land holdings by the issuing of warrants against the land in the amount of about $1,250,000." Once the warrants had been issued, landowners could "convert them into cash, although at a discount," because "it would require a constitutional amendment to issue bonds [to purchase the lands]." [24]

Then Maier introduced a new obstacle to the land-purchase bill: "industrial lobbyists." At the ongoing special session of the legislature, members debated "the new State Pension Fund which, if it is to become permanent, will call for about $6,500,000 additional taxes per year." "The State," reported Maier, "is already about $12,000,000 in the red;" a condition that he considered "nothing unusual in a State having the size and resources of Texas." In a normal year, said the ECW officer, "the State is usually from five to twelve million dollars in the red." Yet "the bill proposing the purchase of the private land is bound to meet with a strong opposition from industries, because industry is so heavily taxed in this state where homes of less than $3,500 valuation are exempt from taxation." In addition, "there has been a strong opposition to a sales tax," wrote Maier. "But after all," he believed, "a million and a quarter dollars is a very low figure for such an area, especially in view of the many millions that would eventually result to the State." Maier did express concern about the campaign to inform Texans east of the Big Bend country of the merits of the park. "Most of these people," said Maier, "have never been to the western half [of Texas] and are not particularly interested in a project benefiting that part of the state." Nonetheless, "a great deal of good work has been done in contacting the Members of the Legislature and a great many have already pledged their support of the proposed bill." Maier also noted that the attorney general had agreed to a "sale" of the 97,799.60 acres of school lands at the cash value of one cent per acre. This the attorney general had ruled was not "a gift," and "at this price the amount involved [$978] would be negligible." [25]

The mineral rights issue, and the need for resolution in advance of the 1937 Texas legislative session, reached all the way to the NPS director's desk in Washington. Maier wrote to Arno Cammerer to solicit either his attendance at the Texas schoolteachers' association conference, or that of a high-ranking NPS representative. T.H. Shelby, chairman of the executive committee of the teachers' association, told Maier that he would support waiver of the mineral rights "if it can be proven that the income that will result to the School Fund from the establishment of the national park would be greater than that which might obtain from future mineral developments." "Of course," Maier declared, "such a comparison is one that only the Lord himself could prove." Yet the NPS needed a spokesman at the convention to state "what the [Interior] Secretary will accept and what he will not accept in the case of mineral restrictions." Maier advised that "a clean-cut proposition on the part of the National Park Service representative at the meeting appears obligatory." Maier did not wish to commit the NPS to a position not easily defended, yet "favorable consideration of the Appropriation Bill by the State Legislature in January is so very definitely dependent upon a prior indication of support by the School Fund, which is the strongest lobby in Texas." [26]

With the stakes so high, and the need for positive imagery so critical, NPS historian William Hogan approached Maier in October 1936 with what he called "a suggestion which may seem unusual at first glance but which is more than justified by the facts." He wanted his superior in Oklahoma City to consider employing the noted Texas historian, Walter Prescott Webb, as an historical consultant. Hogan, a former student of Webb's at the University of Texas, described the scholar's 1931 study of the Great Plains as "one of the greatest contributions ever made to western historiography, perhaps the greatest since Frederick Jackson Turner's 1893 epoch making address before the American Historical Association." Hogan knew that Webb had taken a leave of absence for the 1936-1937 academic year, and suggested that "he be requested to visit the Big Bend country with the end in view of preparing a series of historical sketches, perhaps three in number, relating to the historical background of the proposed international park." Hogan had "reason to believe that Dr. Webb would seriously consider such an offer," as the Texas professor "not only has a personal interest in the proposed Big Bend Park, but he is also the type of writer who enjoys and believes in the necessity for field work as a preparation for writing." The NPS should also realize that "if he should decline the offer, it would probably be because of salary considerations." The standard NPS consulting rate of "ten dollars per day is a small salary," said Hogan, "for a man who has sold the movie rights in his last book [The Texas Rangers] at a figure variously reported to be from ten thousand dollars to twenty-five thousand dollars." Hogan also encouraged swift action, as "Dr. Webb may never be available again," and "his plans for the next nine months are fast maturing." [27]

The NPS historian also contended that "a still more pressing reason is that the historical and legendary background of the Big Bend country can best be found out now, before the influx of tourists and dude ranches." In addition, "Dr. Webb is a master at writing history from modern, living sources;" a key aspect of a project where "men are yet living who can speak with authority about the development of this part of the West." As to those NPS officials who might prefer a park service historian, Hogan replied that "Dr. Webb's contribution, whatever it may be, will be absolutely unique and . . . no other man in the historical profession, either in or out of the National Park Service, is so well equipped to make the type of study herein suggested." Webb would not be asked to write "the whole history of the Big Bend area," as "that will, of course, be a future task of National Park Service historical technicians." Instead, the agency should realize that "the employment of such an eminent historian and writer would, undoubtedly, give the National Park Service an invaluable contact with the historical profession." This, in turn, "would serve to give Park Service historical activities a higher rating among historians," an important feature of NPS work in light of passage in 1935 of the Historical Sites Act, giving the park service a mandate to preserve America's cultural and historic treasures alongside its monuments to natural beauty. [28]

Hogan's idea fired the imagination of Herbert Maier, who wrestled with the constraints of New Deal funding and the realities of park promotion. Maier wrote to Branch Spalding, acting assistant director of the NPS in Washington, to solicit funds for Webb's work. "At the present time," said Maier, "we are doing everything possible to emphasize to the people of Texas their great opportunity in turning over the Big Bend area to the federal government as a national park." To expedite this process, said Maier, "we must emphasize its values." Thus he considered "the temporary employment of Dr. Walter P. Webb as an outstanding opportunity." Spalding wasted little time replying to Maier that "this idea is one which we naturally support very enthusiastically." He had asked the personnel division of the NPS for advice on a fee for Webb, and learned that "it might be possible to secure as much as $20.00 per day." Spalding cautioned that "all of this, of course, assumes that sufficient money is available in the [CCC] camps of your Region to meet this sum." Maier then turned to Hogan to identify the potential for funding, and to outline "a very clear-cut understanding with Dr. Webb as to just what he would produce in the time that would be allotted to him." Maier knew "the value that would probable result from Dr. Webb's work." Nonetheless, said the ECW official, "we must bear in mind that the appropriation under which we are working is part of the relief administration and funds must be spread out as much as possible." He also recognized that "any such writing would return profit to Dr. Webb." Maier thus warned that "the profit would be his and the royalties would not accrue to the government as would otherwise be the case." Yet the imperatives of park promotion led Maier to conclude: "I am very much in favor of getting the material from Dr. Webb, especially at this time." [29]

Even as Herbert Maier pursued the talents of Walter Prescott Webb to promote the future Big Bend National Park, he also in late 1936 had to contend with the lack of photographs for use in publicity. George Grant had yet to generate a set of prints from his venture into the Big Bend country and Mexico. Maier also learned of the reason why W.D. Smithers had denied the NPS use of his collection of Big Bend photos. In correspondence with Fanning Hearon, Maier reported that Smithers "has had a falling out with the Texas State Parks Board in connection with the right to take photographs in this area." Smithers for years "had done considerable business in the making of photographic post cards and scenic views of this area as a commercial activity." When Smithers "locked up all of his negatives," and "consistently refused to furnish any prints of any kind of the Big Bend," he left Alpine "on a scientific expedition," said Maier, "Lord knows where." What few copies the NPS had of Smithers' work "have had extensive use," he told Hearon, "and are second-rate." Maier now believed that "it is unreasonable to offer these same second-rate copies over and over again in connection with articles and publicity material we are constantly being requested to submit for publication." [30]

As 1936 drew to a close, concern over the land acquisition plan became more intense with word that Ira Hector, the Chisos Basin rancher on whose property the CCC camp stood, wanted permission to build a residence and corral on "Section 16," which the Texas state parks board had yet to purchase. Camp superintendent Morgan reported to William Lawson of the state parks board that Hector's "cattle are doing a lot of damage and his attitude is getting worse and worse." Hector was "continually burning things in the area," Morgan continued, "and causing damage to trees and other vegetation." The solution, said Morgan, was to "satisfy him on this section 16 and get him out of here," a strategy that the CCC camp director called "a very wise move." The Hector controversy led Maier to write William Lawson about the larger issue of land acquisition. The ECW official recalled that "this land is a part of an estate left to [Hector] and his sisters some time ago," with Ira Hector "the only one attempting to make any sort of a living on this land." Then D.C. Colp, Lawson's predecessor as executive secretary of the parks board, had negotiated with Hector "to pay . . . a certain amount for the land he holds in Green Gulch, which is absolutely necessary as a road is to be built to the heart of the area." In exchange, "Hector was to retain grazing rights." Maier since had learned that "this contract [with the state parks board] was not carried out and that Hector has never received any of the money for the portion of his land, excluding grazing rights." [31]

With the legislative session in Austin set to open within 30 days, Maier pressed Lawson for advice on correcting Colp's oversight. "As regards the road we are building into the Basin," said Maier, "which is to be the principal development area regardless of whether the Big Bend becomes a national park or not," the NPS faced an obstruction - Ira Hector's cabin- which was "right in the narrowest portion of Green Gulch." Said the ECW regional director: "It is absolutely necessary to run the road through the corral and cabin site in order to get up over the Pass, since at this point there is a deep ravine and the canyon cannot be more than 100 yards wide." Then the NPS needed resolution of "this confounded matter of grazing rights." Maier claimed that "Hector's cattle run wild over the Chisos Mountains, and they are continually cutting through trail banks and shoulders, and breaking down road bank sloping activity" undertaken by the CCC. The work crews had graded the road "to its objective, with the exception of the gap at Hector's cabin, and this is doubly serious because a vehicular bridge at this point has to be left incompleted." Maier further expounded upon Hector's habit of burning all of the maguey or century plants that he could find. "These beautiful specimens," said the ECW official, "dot the landscape everywhere in the Chisos." The park service had learned that "someone once told Hector that they [the plants] are poisonous to cattle." Since "Hector believes this," said Maier, he "now has the distinction of being the only man in the world who is cracked on the subject." Maier described Hector's behavior as "everytime he sees one of these beautiful things towering perhaps twelve feet in height, he must set fire thereto." Compounding the problem of environmental damage was the fire hazard created by such indiscriminate burning. Yet Maier found Hector to be "comparatively careful, and I know that he is sincere when he feels that this growth is injurious to his stock." [32]

This latter admission made the land-use controversy most difficult for Maier to resolve. "He is a dandy fellow," Maier told the parks board executive secretary, "a dyed-in-the-wool West Texan, and a good wrangler." Maier did "not know the terms of the original written or verbal agreement between [Hector] and Mr. Colp," and thus could not "say who has been in the wrong." Maier then revealed the challenge that the NPS had faced in the Big Bend country with the state of Texas as a land-acquisition partner. "I most decidedly do know," said Maier, "with all due respect to Mr. Colp, that the latter was better at making promises and closing agreements than with the carrying out of these covenants." In conversation with Everett Townsend, the latter believed that "Brewster County can somehow complete the purchase of Hector's land, particularly that which is needed for the completion of the section of road described." The county could use its own general fund, advised Townsend, "or perhaps through some special appropriation." Maier speculated that the county would need an additional $3,500 beyond what the parks board already had paid Hector, but that the NPS could not contribute to this latest payment. Because of criticism engendered by the original action, Maier suggested that "it would, perhaps, be simpler for Brewster County to purchase the Hector land with an eye to selling it later to the state Government, when and if the State acquires the land for national park purposes." [33]

As if it were an omen of events to come in 1937, the discovery by Herbert Maier of the extralegal practices of D.C. Colp portended the failure of Texas to appropriate the funds needed to purchase lands in south Brewster County. Robert Morgan had learned from the chief engineer of the state park board that "he did not see any chance for the Legislature to do anything" in the 1937 session. R.O. Whiteaker had come to the CCC camp with three state representatives, and Everett Townsend, in mid-November, and the party contended that "it is almost impossible to hope for any success for our efforts." To this Morgan could only add: "This has led me to believe that probably you [Maier] are not getting very much assistance from that point." He claimed that "from my previous political experiences in Austin I long ago came to the conclusion that the Oil Companies come very near to controlling the legislature bodies." His assumption "has been confirmed to a certain extent lately by conversations I have had with parties who have visited us here." Morgan thought that "we might accomplish a lot if we could get the Oil Companies sold on the proposition and get them to use their lobby for us." The CCC superintendent recommended that Maier approach a friend of his, L.W. Kemp, formerly of the "Asphalt Sales Division of the Texas Co. [later renamed 'Texaco']." Kemp was "very popular around the Capitol," said Morgan, "and with all the contractors and engineers in Texas." An added bonus for the NPS was that Kemp "is a member of the Centennial Committee on Historical points." Because Kemp had "lots of contact with the Legislature on matters of this kind and knows every angle of the lobby business," Morgan believed that "his influence . . . would help." Then the CCC superintendent warned Maier of yet another political problem facing the Big Bend land program. "I am informed," wrote Morgan, "that in all probability there will be quite a fight over the Speaker of the House this next session." Coke Stevenson "will probably be lined up in opposition to the man having the backing of Governor Allred." While the NPS could do nothing about internal Texas politics, Morgan wondered: "Just what influence this would have on a [park] bill sponsored by Mr. Stevenson is a question worthy of some consideration." [34]

Herbert Maier received independent corroboration of Morgan's claims after Thanksgiving, when Leo A. McClatchy, associate regional planner for the NPS office in Oklahoma City, wrote to his superior that "executives of Texas metropolitan newspapers . . . are of the opinion [that] there is very little chance of passing through the 1937 Texas Legislature a bill carrying an appropriation to purchase land to establish the Park." McClatchy, well-connected in media circles, reported that "the next Legislature will be very 'tight' on appropriations, and will probably throw aside all bills seeking funds for projects that are not deemed to be immediately essential." Big Bend, unfortunately, fell "in this class," said McClatchy's confidants, who believed that "it would require the active support of influential organizations and individuals who are strong politically, to get such a bill passed." This "active support," however, "does not appear to be available." McClatchy had found no concentrated opposition to the land program; indeed, "all of the newspaper people with whom I talked are friendly to the park." They also had "given help both in their editorial and news columns." Several media officials "suggested [that] the National Park Service should drum up this active support." McClatchy could only offer standard NPS policy that "we could not be placed in the position of a federal agency attempting to tell a State what the State should do." The park service, McClatchy reiterated, was "ready to cooperate in every way possible, but that we cannot come into the State and take the initiative." In response, the Texas media representatives mentioned that the land bill "should be introduced in January," as "committee hearings would develop considerable publicity, and would pave the way for getting the appropriation from a later session . . . when the State is in a better financial position than it is now." [35]

At year's end, no one in the NPS could predict the mood of the Lone Star lawmakers towards the land-acquisition bill. Newspapers as distant as the San Francisco News carried Leo McClatchy's press releases on the merits of Big Bend. In a story entitled "1,200,000 Acres of Peace Proposed on U.S. Border," the California daily told its readers: "While President Roosevelt at Buenos Aires was lending the weight of his presence and his well-chosen words toward the securing of peace among men of good will in the two Americas, scientists of neighboring North American republics are examining the possibilities of a proposed International Peace Park in the Big Bend country of the Rio Grande." After outlining the standard NPS description of Big Bend's extraordinary ecology and geology, the News asked: "With a region combining the sublime and the startling, Jack Garner presiding [as vice-president] over the Senate, and Maury Maverick in the [U.S.] House, can there be any doubt of the future of the Big Bend country?" Everett Townsend, however, saw another side to the land-acquisition controversy not conveyed to readers of park service publicity. In a last-minute canvass of state lawmakers over the Christmas holidays, Townsend had learned that the Texas State Teachers Association would not accept any settlement of the mineral-rights claims that they held in south Brewster County. Coke Stevenson had told Townsend to have NPS officials ready in Austin at the start of the legislative session to meet with the state attorney general, and to draft a bill soon thereafter. Then the NPS should invite the attorney general "or one of his assistants," said Townsend, to visit Big Bend. Having these officials in the future park area as the legislators discussed land purchase would generate valuable publicity, as well as prepare the attorney general to make the NPS's case effectively in Austin. [36]

In light of this mixture of editorial support and legislative opposition, the park service weighed in with its own brochure at the end of 1936 entitled, "The Big Bend National Park: A State Asset." When readers turned past the cover photography of "St. Helena Canyon," the first sentence read: "What would be a finer thing for Texas, just as an advertising medium, than to have located within its borders one of the largest National Parks on the American Continent?" The brochure quickly moved to quotations from major newspapers nationwide on the value of Big Bend to the American people. Even the New York Times of November 15 had only words of praise for this "symbol of peace between two nations." The Times's editors declared that "nature lovers will travel in the next few years to enjoy the splendors and scenic beauties of what eventually is expected to be the largest international park on this continent." They noted that "the international nature of the project was virtually assured last week when committees representing the United States and Mexico met at El Paso, Texas, and worked out detailed plans for cooperation between the two governments." In addition, editorialized the Times, "almost all of the superlative adjectives imaginable have been used by visitors to describe those parts of the Big Bend park site which they have seen." [37]

As if to demonstrate the power of Big Bend upon the imagination, the park service brochure stated: "This little Empire, shut off from the rest of Texas by a kind of no man's land, holds within its confines the last vestiges of the primitive West." The brochure evoked a land "rich in romances of the long ago, in Indian legends, in folklore, in cowboy songs, and its border feuds." Added to this was the scientific value of Big Bend, leading "eminent scientists from all parts of the country [to visit] this treasure-house annually for new specimens and discoveries." For those drawn to the natural beauty of America's national parks, Big Bend offered "its magic purple of mountains; . . . its green, rolling uplands; . . . its verdant riot of canyon depths and gray crags brooding above; . . its flaming sunsets; and . . . its white-starred depths of night." To this land "artists from Texas and beyond its borders are finding new materials in color and form." The brochure writers thus predicted: "What a fortunate date for Texas when paintings of her own scenery shall adorn the art galleries, homes, and public schools all over the State!" In a more realistic vein, the brochure noted that "good highways will follow in the wake of the Park." Once the Big Bend country had access to the outside world, "what would be more natural and logical," asked the writers, "than for the American tourist from the heart of the United States to take the most direct route through the Chisos Mountains, linger there awhile to marvel at its wonders, and then journey on into the fairy land of Old Mexico rich in its art treasures, fascinating in its tumultuous but enlightening history, and glorious in its scenery!" Even if visitors had more prosaic tastes and desires, said the brochure, they too could find solace and wonder in the Big Bend. "But it is as a Playground that the Big Bend National Park would be most valuable to Texas people," declared the NPS brochure. "The family with moderate means could afford to take a vacation and a much needed rest within the borders of its own state," while "the business man, perplexed with his problems or wearied with his toils, could find within striking distance of his business, just the relief he needs in the quiet retreats of mountain fastnesses." [38]

Eighteen months after Congress had authorized creation of Big Bend National Park, the patterns of land acquisition and publicity had become clear. Park service officials and local park sponsors mixed imagery of isolation and wilderness with beauty and wonder to attract future visitors, and to convince Texans of the rare opportunity awaiting them with their first national park unit. Yet behind the scenes, these same individuals struggled with the realities of the Depression, the New Deal, Texas's relationship to the federal government, and the power of ranchers and corporate officials to direct the fortunes of Brewster County. Once the Lone Star lawmakers gathered in Austin to discuss the fate of Big Bend National Park, the NPS and its private-sector allies could only hope that months of planning and dreaming would make a difference.

| |

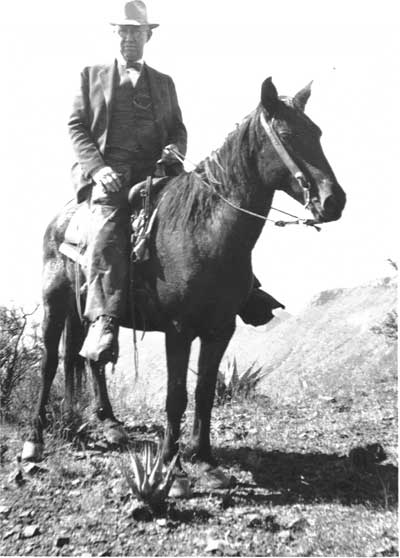

| Figure 8: Congressman Thomason Riding Horseback in the Chisos Mountains, 1933 | |

Endnotes

1 Memorandum of Townsend, "State Legislation Needed For The Acquistion Of The Territory To Be Embraced Within The Proposed Big Bend National Park," January 13, 1935, Townsend Collection, Box 8, Wallet 23, Folder 24, Archives of the Big Bend, SRSU.

3 Memorandum of Townsend (?), "Big Bend National Park Project: A Classification and Study on Land Values," n.d. (1936?), Townsend Collection, Box 8, Wallet 23, Folder 4, Archives of the Big Bend, SRSU.

4 Memorandum of Townsend (?), "Big Bend National Park Project: Land Data," n.d. (1936?), Townsend Collection, Box 8, Wallet 23, Folder 4; Higgins to Townsend, July 29, 1935, Townsend Collection, Box 8, Wallet 23, Folder 20; Memorandum of Townsend (?), "Partial list of Tax Delinquents In Big Bend Park Area," January 18, 1936, Townsend Collection, Box 8, Wallet 23, Folder 25, Archives of the Big Bend, SRSU.

5 Maier to Wirth, March 9, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments, and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 94, Folder: 4th Progress Report on Big Bend - Region III, DEN NARA.

6 Telegram of George Grant, Fort Bliss, TX, to Maier, March 7, 1936; Maier to Wirth, March 8, 1936; Maier to Grant, March 9, 1936; Grant to Maier, March 11, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments, and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 94, Folder: 4th Progress Report on Big Bend - Region III, DEN NARA.

7 Maier to Townsend, March 10, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments, and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 94, Folder: 4th Progress Report on Big Bend - Region III; Memorandum of Maier to National Park Service, Washington, DC, March 28, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, EDW and ERA Work in National Forests, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Big Bend National Park, TX/Bryce Canyon National Monument, UT, Box 97, Folder: 833-10 (CCC) Botanical Exhibits, DEN NARA.

8 Townsend to Col. R.O. Whiteaker, Chief Engineer, Texas State Parks Board, Austin, March 31, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments, and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 94, Folder: 4th Progress Report on Big Bend - Region III, DEN NARA.

9 J.W. Gilmer, Big Bend Abstract Co, Inc., Alpine, TX, to Maier, May 18, 1936; Alonzo Wasson, "Chance of Big Bend Park Being National Domain Is Dwindling," The Dallas Morning News, May 18, 1936, RG 79, NPS SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments, and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 94, Folder: General April 1, 1936-July 30, 1936, DEN NARA.

10 Wasson, "Chance of Big Bend Park," Dallas Morning News, May 18, 1936.

11 Morelock to Maier, May 21, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments, and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 94, Folder: General April 1, 1936-July 30, 1936, DEN NARA.

12 Townsend to Maier, May 22, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments, and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 94, Folder: General April 1, 1936-July 30, 1936, DEN NARA.

13 Morelock to Lewis B. Cooper, Director, Research Department, State Teachers Association, Fort Worth, TX, May 25, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments, and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 94, Folder: General April 1, 1936-July 30, 1936, DEN NARA.

14 Maier to Morelock, June 13, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments, and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 94, Folder: General April 1, 1936-July 30, 1936, DEN NARA.

15 Townsend to Maier, June 14, 1936; Morelock to L.A. Woods, Superintendent, State Department of Education, Austin, TX, June 23, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments, and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 94, Folder: General April 1, 1936-July 30, 1936, DEN NARA.

16 Maier to the NPS Director, Washington, DC, Attn: Mr. Moskey, July 1, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments, and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 94, Folder: General April 1, 1936-July 30, 1936, DEN NARA.

17 Maier to Wirth, July 3, 1936; Maier to the NPS Director, Attn: Mr. Fred Johnston, July 3, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments, and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 94, Folder: General April 1, 1936-July 30, 1936, DEN NARA.

18 Morelock to M.S. Leopold, Supervising Engineer, Motion Picture Production Section, Information Division, Department of the Interior, Washington, DC, August 1, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 96, Folder: General Part 2, DEN NARA.

19 Towsend to Maier, August 9, 1936; "Remarks Made By E.E. Townsend, On Showing The Big Bend Movie To The Lion's Club, Alpine, Texas, August 11, 1936," RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 96, Folder: General Part 2, DEN NARA.

20 Maier to Ellsworth C. Dent, Division of Motion Pictures, Office of the Secretary, Department of the Interior, Washington, DC, August 18, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 96, Folder: General Part 2, DEN NARA.

21 Maier to Fanning Hearon, Division of Motion Pictures, Office of the Secretary, Department of the Interior, Washington, DC, August 29, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 96, Folder: General Part 2, DEN NARA.

22 Ibid.; Hearon to Maier, September 10, October 6, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 96, Folder: General Part 2, DEN NARA.

23 Townsend to Maier, September 11, 21, 1936; Maier to Townsend, September 26, October 8, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 96, Folder: General Part 2, DEN NARA.

24 Maier to Wirth, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments, and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 22, Folder: 800 Protection Services to Public #2, DEN NARA.

26 Maier to Cammerer, November 16, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 96, Folder: General Part 2, DEN NARA.

27Memorandum of William R. Hogan, Associate Historian, NPS, Oklahoma City, to Maier, "Employment of Historical Consultant for Big Bend Area," October 12, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 96, Folder: General Part 2, DEN NARA.

28 Ibid. For a more thorough assessement of the forces shaping the Historic Sites Act of 1935, see Michael Kammen, Mystic Chords of Memory, 460-71.

29 Maier to Branch Spalding, Acting Assistant Director, NPS, Washington, DC, October 14, 1936; Spalding to Maier, November 5, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments, and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box x, Folder: xx; Maier to Hogan, November 27, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 96, Folder: General Part 2, DEN NARA.

30 Maier to Hearon, December 1, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 95, Folder: DSP 1, DEN NARA.

31 R.D. Morgan, Superintendent, SP-33-T, NPS, Marathon, TX, to Mr. (William) Lawson, November 17, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 96, Folder: General Part 2; Maier to William J. Lawson, December 2, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 95, Folder: General Part 3, DEN NARA.

34 R.D. Morgan to Maier, November 24, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 96, Folder: General Part 2, DEN NARA.

35 Memorandum of Leo A. McClatchy, Associate Recreational Planner, NPS, Oklahoma City, to Maier, "Big Bend National Park," December 7, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 95, Folder: General Part 3, DEN NARA.

36 "1,200,000 Acres of Peace Proposed on U.S. Border," San Francisco News, December 23, 1936; Townsend to Maier, December 28, 1936, RG 79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to CCC, ECW, and ERA Work in National Parks, Forests and Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1933-1934, Box 95, Folder: General Part 3, DEN NARA.

37 "The Big Bend National Park: A State Asset," n.d. (December 1936?), Townsend Collection, Box 9, Wallet 27, Folder 2, Archives of the Big Bend, SRSU.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bibe/adhi/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 03-Mar-2003