|

Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park Colorado |

|

NPS photo | |

Our surroundings were of the wildest possible description. The roar of the water...was constantly in our ears, and the walls of the canyon, towering half mile in height above us, were seemingly vertical. Occasionally a rock would fall from one side or the other, with a roar and crash, exploding like a ton of dynamite when it struck bottom, making us think our last day had come.

—Abraham Lincoln Fellows, 1901

An Awesome Gorge

The canyon has been a mighty barrier to humans from time immemorial. Only its rims, never the gorge, show evidence of human occupation—not even by Ute Indians living in the area since written history began. No early Spanish explorers to the Southwest reported seeing the canyon. The expedition led by Capt. John W. Gunnison. whose name was given to the river, bypassed the gorge in its search for a river crossing. The first written record came from the Hayden Expedition of 1873-74. The Hayden and, later, Denver & Rio Grande Railroad survey parties deemed Black Canyon inaccessible.

Geological diagrams show why this canyon was named "Black ... It is so deep, so sheer, and so narrow that very little sunlight can penetrate it. Early travelers found it shadow-shrouded and foreboding. By 1900 the nearby Uncompahgre Valley wanted river water for irrigation, so five residents hazarded an exploratory float of the river but gave up after a month. In 1901 Abraham Lincoln Fellows and William Torrence floated it on a rubber mattress—33 miles in nine day—and said an irrigation tunnel was feasible. The 5.8-mile Gunnison Diversion Tunnel, begun in 1905 and dedicated in 1909, still delivers water for irrigation.

Area citizens began lobbying in the 1930s to include the canyon in the National Park System. It was proclaimed a national monument in 1933. Congress made it a national park in 1999, and the park now contains 14 miles of the canyon's total 48-mile length. Congress has also designated the park lands below the canyon rims for additional protection within the National Wilderness Preservation System. Wilderness designation is meant to protect forever the land's natural conditions, opportunities for solitude and primitive recreation, and scientific, educational, and historical values. Wilderness enables many people to sense themselves as part of the whole community of life on Earth. Preserving wilderness shows restraint and humility, recognizing what we don't know about the land, which ultimately feeds, clothes, and shelters all.

A Canyon Landscape Primer

"Some are longer, some are deeper, some are narrower, and a few have walls as steep," writes geologist Wallace Hansen. "But no other canyon in North America combines the depth, narrowness, sheerness and somber countenance of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison." Diagrams contrast Black Canyon's profile with those of Yosemite Valley and the Grand Canyon, showing how different canyons form.

Rivers are rare in this region. Where one does occur, diversity of life enlivens the landscape. Streamside or riparian communities account for much of the American West's total biological diversity. Riverside at canyon bottom here are river birch, boxelder, willow, serviceberry, and cottonwood trees. These create food and shelter for insects, birds, and mammals, sheltering even fish and aquatic mammals that can live nowhere else. Canyon walls are special niches, too. Without them canyon wren music would not enthrall us. The national park hosts other wildlife, ranging from weasel and badger to cougar and bear.

Anatomy of Three Canyons

Black Canyon of the Gunnison:

Hard rock uplifted then cut through by fast-moving water

In just 48 miles in Black Canyon the Gunnison River loses more elevation

than the 1,500-mile Mississippi River does from Minnesota to the Gulf of

Mexico. The power of fast falling enables the river to erode tough

rock.

The river drops an average of 96 feet per mile in the national park. It drops 480 feet in one two-mile stretch. Fast, debris-laden water carving hard rock made the canyon walls so steep.

Slow, continuous, unyielding erosion formed the canyon, drop by drop and flood by flood. Rockfalls and landslides play occasional roles. The river first set its course over soft volcanic rock. It then cut down to harder, older crystalline rock of the dome-shaped Gunnison Uplift. Once entrenched in its course, the river had to keep cutting through this hard core for two million years. The Gunnison River now carves its Black Canyon more slowly because dams upstream lessened seasonal flooding. Undammed, the river used to slam through this gorge in flood stage at 12,000 cubic feet per second with 2.75-million-horsepower force, dramatically scouring the riverbed and eroding canyon walls. At Warner Point the gorge is 2,772 feet deep.

Yosemite:

Hard, river-cut rock later gouged by glaciers

Yosemite Valley, seven miles long and variably a mile wide, features

starkly vertical granitic walls and plunging waterfalls that contrast

sharply with its mostly fiat, upper valley floor. There the Merced River

looks far too docile to have helped create such a valley.

Uplift and westward tilting of the Sierra Nevada 10 million years ago turned a meandering Merced River into a fast, canyon-carving stream. Continued uplift three million years ago empowered the Merced to cut a V-shaped valley 3,000 feet deep. From one million to 250,000 years ago, a series of ponderous glaciers gouged-out today's U-shaped valley, leaving tributary streams hanging as high waterfalls. Glacial events also resulted in filling the valley with the lake sediments and rubble that leveled its floor. Black Canyon escaped such glaciation—or it might look more like Yosemite.

Grand Canyon:

Soft, river-carved rock sculpted by erosion

Some five or six million years of erosion have left the Grand Canyon a

mile deep, four to 18 miles wide, and 217 miles long. The semi-arid

area's 15 inches of yearly precipitation mostly come in violent summer

storms that maximize erosion.

The width and distinctive shape of the vast gorge of the Colorado River result from how its greatly varied types of rock resist erosion. Harder rocks erode to cliffs. Softer rocks erode to slopes. Various minerals, most containing iron, give Grand Canyon rocks their subtle red, yellow, and green colorations that shift with the changing qualities of sunlight. The Grand Canyon has been eroding three times as long as Black Canyon.

Canyon Life: It's for the Birds

Canyons aren't barriers to birds. In search of food and water, birds can readily fly to depths and heights forbidding for the energy budgets of other animals, including humans.

Great horned owls hunt rabbits and rodents on canyon rims at night. Their prey eat nuts, seeds, and berries—of pinyon, juniper. and Gambel oak trees and serviceberry and other shrubs prevalent on canyon rims. Its disc-shaped face channels sound waves to the owl's ears—slits at the side of its head, not those feathers atop it. Great horned owls are year-round residents because rabbits and rodents stay active in winter.

Mountain bluebirds share canyon rim habitat with owls but are daytime eaters of insects. Like owls, bluebirds are linked to their habitat by its vegetation, which feeds their insect prey. Bluebirds are migratory, not year-round residents here. They nest in trees and are most often seen in spring and early summer when nesting and rearing their young. They get some moisture from their insect prey but need access to open water, too.

Steller's jays also live on the canyon rims or upper reaches of side canyons where Douglas fir trees grow. They eat seeds and nuts and some insects. They get some moisture from the insects but need access to open water in puddles or ponds. Like other jays, they can seem raucous, meddlesome, and contentious, but Steller's jays, while less attracted to campgrounds, are as opportunistic as other jays about food on picnic tables.

Peregrine falcons nest on ledges on canyon walls and prey on flying birds, swooping down at them as fast as 200 mph. Their balled-up claws shatter prey's bones like bludgeons. Even a bald eagle pursued by a falcon for getting too close to its nest or eyrie may go right to ground to escape contact. Falcons mostly feed on aerial-feeding swifts and swallows but also on jays and an occasional dove.

White-throated swifts are aerial feeders on insects whose scientific name means "rock-inhabiting air sailor." Pairs even copulate in a downward, spinning flight that only looks out of control. Flying on the level these swifts are one of the swiftest of all birds. White-throated swifts nest high on canyon walls in rock crevices and feed mostly in early morning and at evening, when flying-insects are most active.

Canyon wrens sing so wildly, sweetly, and hauntingly that they even figure in a lot of present-day music. These wrens are far more often heard than seen. They nest on ledges like peregrine falcons do, laying eggs in depressions. They hop and poke about ledges and alcoves looking for spiders and insects to eat. At Black Canyon these wrens are seldom if ever seen down along the river itself.

American dippers or water ouzels live and nest along the river. They can walk under fast-moving water to feed, using their wings to stay submerged. They probe for aquatic insects and larvae, fish eggs, and small fish. Dippers bob up and down at up to 60 dips per minute. Their plump body type, like a beaver's, and plentiful down adapt them to cold-water living. They may build their nests of moss behind waterfalls or cascades.

When You Get Here

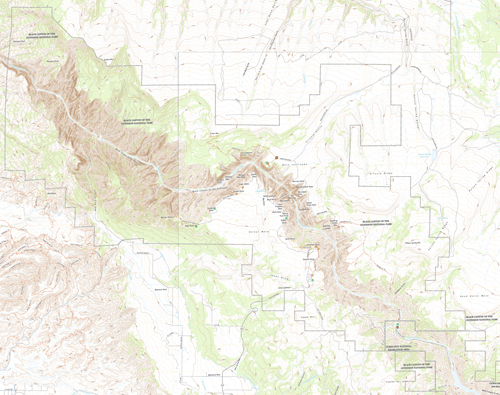

(click for larger maps) |

Stop first at South Rim Visitor Center for accessibility information, exhibits, publications, wilderness permits, and Junior Ranger programs for children. Read the park newspaper for activities, safety, and park-use information. Ranger-guided activities are offered in summer and winter. Ask at South Rim Visitor Center for more information.

The park offers no overnight lodging except camping. Full services, including lodging, are available in nearby communities. Two campgrounds, one on each rim, operate first-come, first-served. You can reserve sites in loops A and B in South Rim Campground at www.recreation.gov. Camping conditions improve as soon as snow has cleared and are usually good until late November. Conserve water; it must be trucked in and is not available late fall through spring. Firewood is not provided and gathering it is prohibited.

Plants, rocks, and cultural artifacts must not be disturbed. Build fires only in grills in the campgrounds. Pets must be leashed and are permitted on most overlook trails; they are prohibited in the inner canyon and wilderness area. Hunting is prohibited. Colorado Gold Medal Waters apply to fishing regulations; Colorado license required. Private property exists in t he park, with conservation easements that limit development. No public access is provided. For firearms regulations ask a ranger or check the park website.

For Safety's Sake

Never throw anything from the rim into the canyon! Even a small

stone can be fatal to someone below. Stay on trails and supervise

children closely. Weathered rock makes rim edges hazardous, and many

places have no guardrails.

Climbing here is for the experienced climber. Ask a park ranger about routes and degrees of difficulty. All inner canyon activities, including hiking, climbing, and kayaking, require a wilderness permit.

The Gunnison River is for experienced kayakers, and rafting is highly discouraged in the national park. Rafters put in at the Chukar Trail in Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area for an intermediate run through the lower canyon. For more information contact Bureau of Land Management.

Weather may be unpredictable at any season of the year. There are a number of trails, most at the rim. Remember, you are at 8,000 eet above sea level. Take precautions, drink plenty of water, and slow down.

Winter snow closes both rim roads to vehicles, but they are open for cross-country skiing and for snowshoeing. South Rim Road is plowed to Gunnison Point, and the visitor center is open all year, except for Thanksgiving Day, December 25, and January 1.

Access

The park is 250 miles southwest of Denver. South Rim is 15 miles

east of Montrose via US 50 and CO 347; its latitude/longitude are

38.55056, -107.68667, for GPS. North Rim is 11 mile; south of

Crawford via CO 92 and Black Canyon Road; its latitude/longitude are

38.58702, -107.68667. Roads closed to vehicles in winter usually reopen

mid-April. Service animals are welcome.

There is no bridge between the north and south rims of the canyon. Allow two to three hours to drive from one side to the other.

Accessibility: We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. South Rim Campground has accessible campsites and restrooms. South Rim Visitor Center, South Rim restrooms, and restrooms at North Rim Ranger Station are all accessible.

East Portal Road (closed in winter) provides access to the Gunnison River and to Curecanti National Recreation Area. The extremely steep road has hairpin curves and 16-percent grades. Vehicles over 22 feet long, including trailers, are prohibited. Outdoor exhibits explain the Gunnison Tunnel. Camping, fishing, and picnicking are available.

Source: NPS Brochure (2013)

|

Establishment

Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park — October 21, 1999 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Brief Discussion of the Potential for Construction of a Water Supply Well for NPS Facilities at the South Rim, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park (Larry Martin, January 14, 2005)

A Brief Discussion of the Potential for Construction of a Water Supply Well for the North Rim of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park (Larry Martin, January 5, 2005)

A Brief History of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument (Platt Cline, 1936)

Administrative History of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument (Richard HG. Beidleman, 1965)

Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2009/227 (Tim Hogan, Nan Lederer, Dina Clark and Walter Fertig, July 2009)

Archeological Survey of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument and Archeological Inventory and Evaluation of Curecanti Recreation Area Midwest Archeological Center Occasional Studies in Anthropology No. 7 (Mark A. Stiger and Scott L. Carpenter [Black Canyon] and Mark A. Stiger [Curecanti], 1980)

Black Canyon of the Gunnison: Today and Yesterday (HTML edition) USGS Bulletin 1191 (William R. Hansen, 1965)

Fire Management Plan Environmental Assessment, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park and Curecanti National Recreation Area (October 2024)

Fish of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument (James S. Day, 1975)

Fishes and Fish Habitats in Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument (Brian S. Kinnear and Robert E. Vincent, 1967)

Foundation Document, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, Colorado (December 2013)

Foundation Document Overview, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, Colorado (January 2013)

General Management Plan: Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument and Curecanti National Recreation Area (September 1997)

Geologic and Physiographic Highlights of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River and Vicinity, Colorado (Wallace R. Hansen, extract from New Mexico Geological Society Guidebook, 32nd Field Conference, 1981)

Geologic Map of the Black Ridge Quadrangle, Delta and Montrose Counties, Colorado (Wallace R. Hansen, 1968)

Geologic Map of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River and Vicinity, Western Colorado (Wallace R. Hansen, 1971)

Geologic Resource Evaluation Report, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park & Curecanti National Recreation Area NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2005/001 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, January 2005)

Geomorphic and Sedimentologic Characteristics of Alluvial Reaches in the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument, Colorado U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations Report 99-4082 (John G. Elliott and Lauren A. Hammack, 1999)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

North Rim Road (Janene Caywood, March 23, 1998, revised 2005)

Paleontological Discoveries at= Curecanti National Recreation Area and Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation, Colorado (Alison L. Koch, Forest Frost and Kelli C. Trujillo, New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science Bulletin 36, 2006, ©New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, all rights reserved)

Park Newspaper (Visitor Guide/The Portal): 2003 • 2006 • 2007 • 2008 • 2009 • 2011 • 2012 • 2020

Preliminary Studies of the Agrostology of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument (James W. Rominger, 1983)

Resource/Boundary Evaluation for Lands Adjacent to Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument, Colorado (January 1990)

State of the Park Report, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, Colorado State of the Park Series No. 12 (2014)

Statement for management — Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument (July 1992)

The Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument (Richard G. Beidleman, extract from The Colorado Magazine, Vol. XL No. 3, July 1963)

The Geologic Story of Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area, Colorado USGS Professional Paper 1699 (Karl S. Kellogg, 2004)

The Road Inventory for Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument, Colorado (Federal Highway Administration, April 1999)

Through the Canyon (Mark T. Warner, extract from The Colorado Magazine, Vol. XL No. 3, July 1963)

Vascular Plant Species Discoveries in the Northern Colorado Plateau Network: Update for 2008-2011 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2012/582 (Walter Fertig, Sarah Topp, Mary Moran, Terri Hildebrand, Jeff Ott and Derrick Zobell, May 2012)

Vegetation and Soil Trends, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park and Curecanti National Recreation Area, 2011-2012 NPS Science Report NPS/SR-2025/254 (Carolyn Livensperger, March 2025)

Why the Smoke? Prescribed Fires 2006 Gunnison, CO Zone Fire Management (Bureau of Land Management, 2006)

Black Canyon (NPS)

blca/index.htm

Last Updated: 19-Mar-2025