OPPORTUNITY AND CHALLENGE

The Story of BLM

|

|

|

PROLOGUE:

The Public Domain From 1776-1946

There was nothing but land; not a country at all,

but the material out of which countries are made.

—Willa Cather

My Antonia, 1918

|

PROLOGUE

The Public Domain from 1776-1946

|

|

|

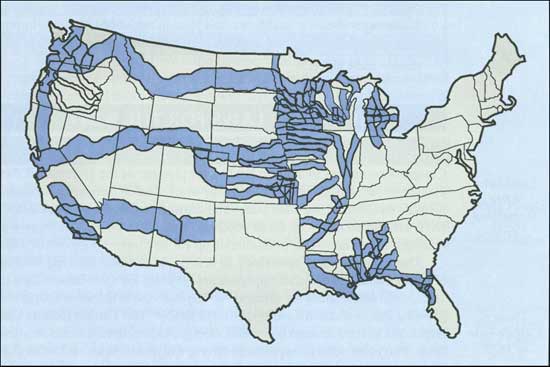

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) today administers

what remains of the nation's once vast land holdings—the public

domain. The public domain once stretched from the Appalachian Mountains

to the Pacific and "constituted," in historian Frederick Jackson Turner's

mind, "the richest free gift that was ever spread out before civilized

man." Of the 1.8 billion acres of public land

acquired by the United States, two-thirds went to individuals,

corporations, and the states. Of that remaining, much was set aside for

national forests, wildlife refuges, national parks and monuments, and

other public purposes, leaving BLM to manage some 270 million acres, as

well as 570 million acres of mineral estate.

|

|

Overview |

|

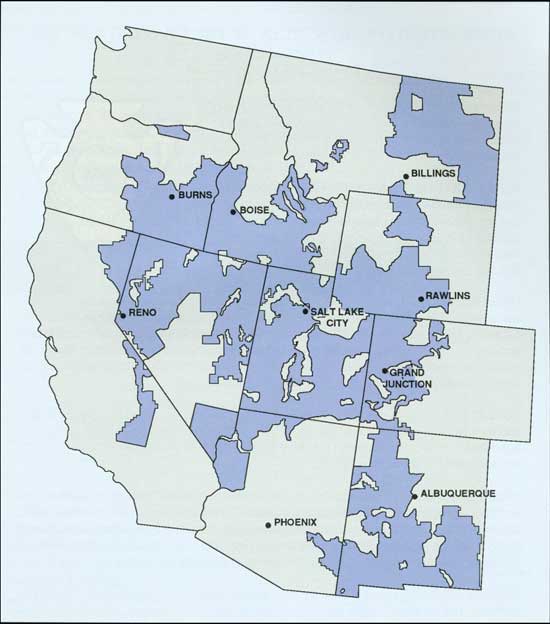

Lands managed by BLM are often scattered and take on

checkerboard, jigsaw, and patchwork patterns, but in much of the Great

Basin, desert Southwest, and Alaska, solid blocks of public land

predominate. These land patterns are inherited: the result of the public

land policies pursued by the country prior to the agency's founding in

1946.

To the young American nation the public domain

represented challenge and opportunity—a wilderness waiting to be

transformed into an agricultural Eden. The nation also needed revenue. A

policy of disposing of public lands through auction seemed to meet both

these needs. As the need for revenue lessened, policy shifted to one of

development and lands were generously provided to settlers,

corporations, and the states. But as the public domain diminished, the

government chose to set aside timber, mineral, and grazing lands and

regulate their development as a means of preserving the opportunity of

the public domain.

|

|

|

ACQUISITION OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN

|

|

|

"The back Lands [sic] claimed by the British

Crown," contended Maryland legislators in November 1776, "if secured

by the blood and treasure of all, ought in reason, justice, and policy...be

considered as a common stock." With that declaration, Maryland

raised the issue of what should become of the territory between the

Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. The issue proved

contentious and threatened the bonds that held the new union of states

together.

|

|

Original

Public

Domain |

|

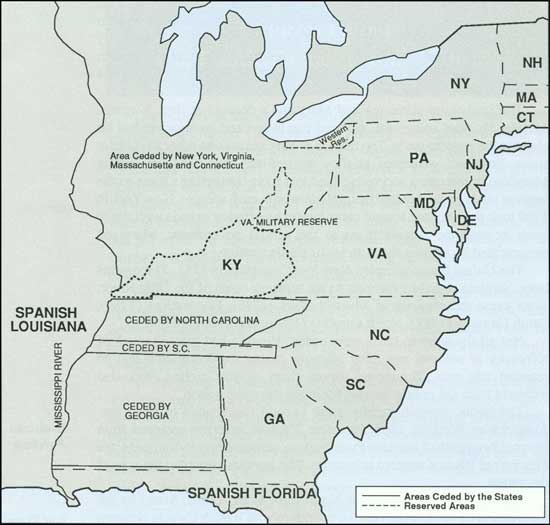

Seven states had claims to the region. Virginia,

Massachusetts, Connecticut, North Carolina, South Carolina, and

Georgia had early colonial charters from England granting them title to

the lands beyond the Appalachians. New York's claim resulted from

concessions by the Iroquois Indians. The remaining states had no claims to the

area.

For states without land claims, like Maryland, the

disposition of western lands was of major importance. They needed

land to reward the soldiers who served in their regiments against the

British. Maryland also feared that if Virginia and the other land-claim

states took title to lands in the trans-Appalachian West, they would

dominate the nation economically and politically. Maryland demanded that

the land-claim states relinquish their title to the central government

and vowed not to sign the Articles of Confederation until that was

done.

The land-claim states resisted Maryland's demand at

first. Virginia, Maryland's chief antagonist, declared that the central

government had no claim to the western lands. The resolve of Virginia

and the other land-claim states, however, weakened as they realized the

importance of having Maryland in the union and recognized that their

conflicting claims to the western lands could threaten their relations

with each another. New York in 1780 took the first step toward

compromise by offering to cede its claim to lands beyond the

Appalachians to the central government. Maryland reciprocated by signing

the Articles of Confederation.

The United States accepted New York's cession in 1781.

Three years later, Virginia ceded its interests to the territory

north of the Ohio River. Then came the cessions of Massachusetts (1785),

Connecticut (1786), South Carolina (1787), North Carolina (1790), and

Georgia (1802).

Not all the western lands were ceded. Virginia had

granted much of Kentucky to soldiers and other interests during the

Revolution and so retained this area. Tennessee, carved from North

Carolina, was also withheld from the public domain for much the same

reason.

|

|

|

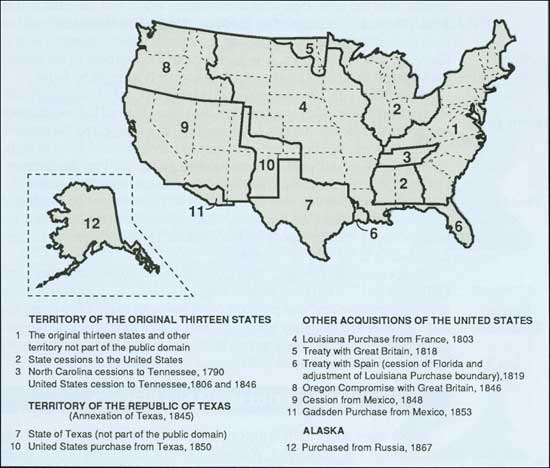

The public domain rapidly grew beyond the bounds of

the trans-Appalachian West. In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson acquired

from France (through the Louisiana Purchase) the immense

region drained by the Mississippi River's western tributaries. The purchase

doubled the size of the nation.

|

|

Louisiana

Purchase |

|

The Red River Valley of the North came to the United

States by the Convention of 1818, which set the boundary with

British Canada between Lake Superior and the Rocky Mountains at the 49th

Parallel. By treaty with Spain the following year, Florida was acquired and

the western border of the Louisiana Purchase redrawn.

|

|

Red

River

Country |

|

America's "Manifest Destiny" to span the continent

was fulfilled in the 1840s. The United States and Britain in 1846 ended

their joint occupation of the Oregon Country by dividing the region

along the 49th Parallel. That same year also saw the beginning of war

with Mexico. American troops seized control of New Mexico and

long-coveted California, and by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848,

the United States took title to the Southwest from Mexico for $15

million.

|

|

Oregon

Country

and the

Southwest |

|

When Texas joined the Union in 1845, it retained

title to its vacant and unappropriated lands. The federal government,

however, purchased the northwest portion of Texas in 1850 and added it

to the public domain. Three years later, James Gadsden negotiated the

purchase of 19 million acres along the Mexican border needed for a

southern transcontinental railroad route. The region was described at

the time by Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton as "utterly desolate,

desert, and God-forsaken."

|

|

Texas and the

Gadsden

Purchase |

|

|

Western land cessions by the original states

|

|

|

"Most astonishing of all the United States' acquisitions of territory,"

in public land historian Paul Wallace Gates' mind, "was the purchase of

Alaska." Americans had expressed no interest in the northern

icebox. The Russian Tsar, however, wanted to sell, and in 1867

Secretary of State William H. Seward obliged. For $7.2 million, the United States

acquired more than 365 million acres and made its last addition to the public

domain.

|

|

Alaska |

|

THE LAND ORDINANCE OF 1785

|

|

|

When New York offered to relinquish its claim to the

western lands in 1780, the Congress of the Confederation responded with

a pledge that "the unappropriated lands that may be ceded or

relinquished to the United States, by any particular state...shall be

disposed of for the common benefit of the United States." This raised

the issue of how public lands should be disposed of.

|

|

|

|

Aquisition of the public domain

|

|

|

Most in Congress agreed that the public lands should

be used as a source of revenue for the nation's cash-starved treasury

and provide land, as promised, to soldiers who had enlisted in the

Continental Army. There was sharp difference, however, as to how

disposal should be carried out.

|

|

Land System

Debate |

|

Most southern delegates favored a system of

indiscriminate location and subsequent survey, as had been the practice

in their states. Others advocated more orderly settlement, voicing

arguments set forth by Thomas Jefferson, that indiscriminate location

with subsequent survey led only to costly and protracted lawsuits as

owners sought to establish boundaries. What they wanted was a system,

like in New England, where survey preceded settlement.

|

|

|

The Confederation in the Land Ordinance of May 20,

1785, opted for the policy of orderly settlement. After Indian title

issues had been quieted by treaty, the public lands were to be surveyed

and numbered by the Geographer of the United States into townships, 6

miles square, and seven ranges. (In this, a rectangular survey system,

townships are numbered in a north-south direction; ranges, in an

east-west direction.) One-seventh of the townships, selected at random,

were to be used to satisfy military land warrants. The remaining

townships were to be auctioned at not less than $1

an acre. Half the townships were to be offered whole

and the other half in "lots," later called sections, 1-mile square. The

United States reserved Lot 16 in each of the townships to provide

revenue for public schools as well as four other lots for later sale.

The government also reserved rights to one third interest in any gold,

silver, lead, or copper that might be found.

|

|

Land

Ordinance

Provisions |

|

Operation of the Land Ordinance disappointed

Confederation officials. Surveys were slow. The Geographer of the United

States Thomas Hutchins began work in the fall of 1785,

but dense forests, swamps, and the threat of Indian attack resulted in

the survey of only four ranges after 2 years of work.

|

|

Surveys Begin |

|

Impatient to sell public lands and bring revenue into

the treasury, Congress ordered the completed townships auctioned in

the fall of 1787. Not one whole township sold and

only 108,431 acres were bid for. Indian troubles, the distance of the lands from agricultural

markets, and the availability of cheaper lands in the original 13

states were all factors contributing to the lack of interest.

|

|

First Land

Sale |

|

Desperate for revenue, the Confederation abandoned

the Land Ordinance of 1785 and contracted to sell public

lands, without competition, to two speculative land companies: 1.5 million acres to

the Ohio Company and 1 million to a company headed

by John Cleve Symmes. Both offered Congress mere pennies per acre but, in the end, were

able to purchase only a portion of the lands contracted.

|

|

Sales to

Speculators |

|

EARLY PUBLIC LAND POLICY

|

|

|

The United States ratified the Constitution in 1788,

rendering the Land Ordinance of 1785 inoperable. A new public land policy

had to be enacted. By Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2, of the

Constitution, the task fell to Congress, for it had the "Power to dispose of and

make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory and other

Property belonging to the United States."

|

|

Constitution

and the Public

Domain |

|

Congress debated the public lands questions for

several years but no general policy was enacted until 1796.

Interestingly, the debates did not center on whether the public lands

should continue as a source of revenue, since the national debt

continued to be troublesome, but rather to whom the lands should be

sold. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton wanted the lands sold

to capitalists and land companies who could pay top price for public

lands. Pennsylvania Congressman Albert Gallatin, an adherent of Thomas

Jefferson thinking on public land matters, did not oppose Hamilton's

thinking, but did urge that cash poor farmers be accommodated.

|

|

Land System

Debate

Renewed |

|

The Land Law of 1796 sought a compromise between the

positions. The law provided for the disposal of the public lands north

of the Ohio River by the Department of the Treasury. Lands could be

purchased in unlimited quantities at the minimum price of $2 per acre,

with the full balance not due for a year. Half the townships sold in

quarter townships, the other half was offered in 640-acre sections.

Congressman Gallatin and his supporters hoped that settlers would pool

their resources to buy the 640-acre tracts, but when bidding for prime

agricultural land, monied interests had the advantage.

|

|

Land Law of

1796 |

|

JEFFERSON AND HAMILTON AND THE PUBLIC

LANDS

by Jerry A. O'Callaghan

Volunteer Historian

Thomas Jefferson (Jennifer Reese)

Alexander Hamilton (Jennifer Reese)

|

Thomas Jefferson, the nation's first Secretary of

State, and Alexander Hamilton, its first Secretary of the Treasury, had

strong opposing views on which social/economic groups could best

guarantee the future of the new nation.

Jefferson, a Virginia landowner, wanted

self-sufficient family farmers as the base from which to build

the new nation. He assumed they would produce enough to feed and clothe

themselves, and sell the surplus to buy other necessities. Because they

were landowners, Jefferson also assumed they would take an interest in

public affairs. Their rural lives would allow them to study public

issues and officials, unswayed by the commercial, industrial, or

financial preoccupations of cities.

Jefferson wanted the government to sell public lands

to small farmers in tracts that would provide the self-sufficiency he

envisioned. In short, Jefferson's public lands strategy was to retail

small tracts at cut rate.

Hamilton, a New York lawyer, cast his lot with, in his

words, "the rich, the able, and the well-born," who could organize and

finance commercial and industrial enterprises. Hamilton's plan was more

complicated. He saw public lands as a way to back the government bonds

sold to merchants, bankers, and others. He favored auctioning public

lands in large blocks to promote maximum revenue with low overhead. By

investing in land, "the rich, the able, and the well-born" helped

guarantee revenue that would return their capital with annual

interest.

Hamilton's strategy, then, was to sell public lands

at wholesale and bind the merchants and bankers to the new nation.

Hamilton's view prevailed in the Public Land Act of 1796. Hamilton's

plan required small farmers to buy their farms from those who had the

money to respond to his strategy. Small farmers did not stand still for

such treatment. Their aggravation brought on the Land Act of 1800, which

authorized local land offices, reduced the minimum size for purchase and

extended credit. In 1820 credit was abolished, but the minimum price was

lowered. The ultimate in the retail policy was the Homestead Act of

1862. Under it, at no cash costs other than fees, settlers could buy

160-acre, self-sufficient farms with their time and labor.

Jefferson's views quickly supplanted Hamilton's.

Nevertheless Hamilton has prevailed over all with national and

international markets placing a premium on one-crop farming—the

antithesis of self-sufficient farming. Such commercial agriculture gives

great economic rewards. It also takes them away. Jefferson's influence

is present in federal agricultural policy to mitigate wide market swings

and natural disasters such as drought.

|

|

|

Another notable feature of the Land Law of 1796 was

the retention of the rectangular survey system established by the Land

Ordinance of 1785. As before, public lands were to be surveyed before

sale. Surveys were to be contracted to independent surveyors who would

follow the direction of a surveyor general. In executing township

surveys, they were to note "all mines, salt licks, salt springs, and

mill-seats...all water-courses...and also the quality of the lands" in

their notebooks, so that purchasers could be informed about the

character of the lands being offered.

|

|

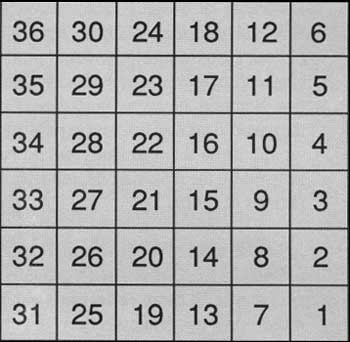

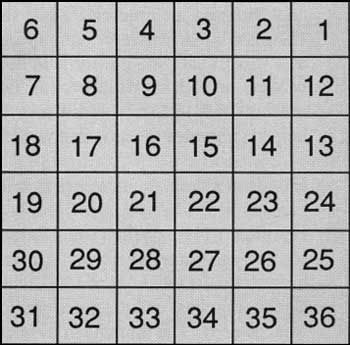

Rectangular

Survey System |

|

|

Township configuration under the Land Law of 1796

|

|

|

Township configuration under the Land Ordinance of 1785

|

|

|

The sale of public lands came 2 years later. The

results, as with the earlier Land Ordinance, were disappointing. At

auctions held in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, less than 50,000 acres

sold. Congress reacted to the poor showing by amending the Land Law of

1796.

|

|

|

The Land Law of 1800 embodied many provisions

advocated by frontier interests. Tracts offered for sale were reduced to

half sections (320 acres) and purchasers were given 4 years to pay the

amount bid, with an 8 percent discount if the entire amount was paid at

the time of auction. Another important feature of the act was the

establishment of land offices in Cincinnati, Chillicothe, Marietta, and

Steubenville. The offices were near the lands being sold and gave

westerners an opportunity to bid on the offered lands.

|

|

Land Law of

1800 |

|

The local land office became an important center of

activity on the frontier. Here, people made entry for the public lands.

Administering the offices were a register and receiver, appointed and

removed at the discretion of the President. The register entered the

land applications in the record books and on the survey plats of the

office. The receiver handled all payments and receipts. These actions

were supervised by the Secretary of the Treasury in Washington. Land

offices were moved or closed as the public lands within their

jurisdictions dwindled or as new public lands were being surveyed and

opened to entry. More than 360 district land offices were ultimately

established.

|

|

Local Land

Office System |

|

The Land Law of 1800 stimulated a sharp increase in land sales. By the

close of 1802, more than 750,000 acres had been sold. Further

stimulation came with the Land Law of 1804, which extended credit

payments and reduced the size of tracts offered for auction from 320 to

160 acres.

|

|

Land Law of

1804 |

|

Congress also opened the public lands south of Tennessee to sale. The

Land Law of 1803 ordered the region surveyed under the rectangular

system and sold in the manner set forth by the Land Law of 1800.

Hundreds of thousands of acres in the South were soon put on the market

and sold.

|

|

Public Lands

in the South |

|

THE GENERAL LAND OFFICE

|

|

|

To handle the rapidly growing public land business,

Congress created the General Land Office (GLO) in 1812. Headed by a

commissioner, the GLO was given the responsibility to "superintend,

execute, and perform all such acts and things touching or respecting the

public lands of the United States." Previously, public land sales had

been handled directly by the Secretary of the Treasury, while the

Department of War had administered military land warrants and the State

Department, land patents. The General Land Office was placed within the

Treasury Department until 1849, when it was transferred to the new

Department of the Interior.

|

|

Duties and

Function |

|

|

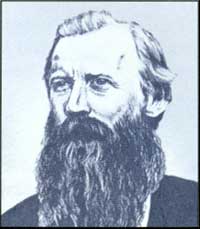

Edward Tiffin (BLM)

|

|

|

|

Responsibility for organizing the GLO went to Edward

Tiffin, its first commissioner. Tiffin, a physician,

former U.S. Senator, and farmer,

set about the task without delay. With a chief clerk and staff of eight,

Tiffin consolidated the land records spread throughout Washington and

began the daily business of processing land entries.

|

|

First GLO

Commissioner |

|

THE BOOM AND BUST CYCLES OF PUBLIC LAND SALES

|

|

|

Public land sales declined with the outbreak of war

with Great Britain in 1812. After the war, however, there was an

unprecedented rush for public lands. Land cessions by the Indians

defeated during the War of 1812 opened the trans-Appalachian region to

farmers and speculators, but the main catalyst for the coming boom was

the rise in agricultural prices. The GLO auctioned off 1.5 million acres

of public land in 1815; within 4 years, 5.5 million acres had been sold.

Competition for land was intense. In some parts

of the South, prime cotton land sold for as much as

$78 an acre.

|

|

Land Rush |

|

COMMISSIONERS OF THE GENERAL LAND

OFFICE

by Jerry A. O'Callaghan

Volunteer Historian

Editor's Note: Jerry O'Callaghan, a 21-year veteran

of BLM, has been a volunteer historian for the Bureau since retiring in 1982 as Assistant

Director of Lands and Minerals.

The Commissionership of the General Land Office has

been one of the nation's most prestigious and sought-after posts. When

Abraham Lincoln's strong bid in 1849 failed, he was so disappointed that

he took a long leave from politics.

Thirty-four Commissioners of the General Land Office

presided over the distribution of one billion plus acres of public

lands—roughly half of the United States' total land area. The

distribution is possibly the largest and most beneficent real estate

deal in history, giving the language an idiom, "doing a land office

business," for a high volume of retail trade.

The General Land Office was created in 1812 to

relieve the Secretary of the Treasury from having to oversee directly

the local land offices. It was a quasi-judicial, ministerial office

centralized in Washington, and became part of the newly formed

Department of the Interior in 1849.

Edward Tiffin, the first commissioner, combined a

long public career with the practice of medicine. When the British

burned Washington's federal buildings in 1814, Tiffin arranged for the

removal of the land records to safety across the Potomac River.

So he could return to Ohio, Tiffin arranged a trade

with Josiah Meigs, the Surveyor-General, with Tiffin himself becoming

Surveyor-General stationed in Cincinnati. Incidentally, Tiffin has been

considered a superb Surveyor-General, a position closely related and

equally important to that of the Commissioner of the General Land Office

to which it later became subordinate.

No commissioner became President, but John McLean

became an Associate Justice of the United States and was often talked

about as a presidential candidate. Thomas A. Hendricks, after his

commissionership, served in the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S.

Senate. He was able to serve only nine months of his term as Vice

President before his death.

Although he served as commissioner a short time,

James Shields must have been very persuasive. He went on to become a senator from

Minnesota, California, and Missouri.

William Sparks was an aggressively forthright

commissioner. His efforts to redress what the public saw as preferential

treatment of the land grant railroads, syndicates and speculators, to

the disadvantage of actual settlers, aroused congressional and press

ire. Three of his annual reports in the mid-1880s were cogent arguments

for public land reform. Both L.C.Q. Lamar, Secretary of the Interior,

and President Cleveland backed him, but Sparks resigned before his term

was over in a difference with Lamar on a railroad case.

Many commissioners had been state governors. The

last, Fred Johnson, was also, briefly, the

Bureau of Land Management's first director.

|

|

|

Then came panic.

America's economy collapsed in 1819. Cotton and other

agricultural prices plummeted and banks failed. The economic depression

threatened the financial stability of the United States. During the land

rush, speculators had taken advantage of the federal government's

liberal payment terms; at the time of the collapse, nearly $23 million

was still owed to the Treasury.

|

|

|

Congress quickly abandoned the credit system. The

Land Law of 1820 discontinued the sale of lands on credit. Full payment

for land had to be made at the time of purchase. However, buyers could

now purchase land for as little as $1.25 an acre and the size of tracts

could be as small as 80 acres. The buyers could still purchase public

lands in unlimited quantities and lands not sold at auction were subject

to private entry at the minimum price.

|

|

Land Law of

1820 |

|

Land speculation did not end with the Land Law of

1820. Although sales declined with the panic of 1819, they increased

steadily during the 1820s. A big jump in land sales came in 1835 when

the acreage sold climbed to 12.5 million acres from the previous year's

4.6 million acres. In 1836, more than 20 million acres were sold. This

surge in sales resulted from an improved economy, an expanded road and

canal system in the West, available money, and the opening of new lands

west of the Mississippi River created by the federal government's

removal of trans-Appalachian Indian tribes.

|

|

Land Sales in

1830s |

|

The federal government was "doing a land-office

business" and the increased sales enabled it to pay off the national

debt. The rampant speculation, however, was being financed by state

bank-issued currency of uncertain value. This fact forced President

Andrew Jackson to issue the Specie Circular of 1836 requiring all

payments for public land to be made in gold and silver coin. This action

brought an end to the land sale boom and sales once again declined.

|

|

|

MILITARY VETERAN LANDS AND PRIVATE LAND CLAIMS

|

|

|

The General Land Office was concerned with more than

land sales during these years. There were also military land warrants

and private land claims.

|

|

|

At the outbreak of the Revolution, the Continental

Congress and states offered land bounties to recruits who joined the

army and navy. The federal government offered the same incentives used

to raise an army for the War of 1812. Giving land for military service

was a time-honored practice. Historian Paul Gates points out that the

practice recognized "that land was not always easy to obtain, was much

in demand, and that a land bounty might prove more attractive than

anything else the government could promise."

|

|

Military Land

Bounties |

|

The amount of land offered to soldiers varied

according to rank. Privates in the Continental Army during the

Revolution received 100 acres, whereas major generals got 1,100

acres.

The call for Virginia and the other land-states to

relinquish their claims to the region west of the Appalachian Mountains

was partly spurred by the need to provide land to soldiers and sailors.

The Land Ordinance of 1785 provided that one-seventh of the townships

surveyed in the first seven ranges be set aside for the location of

military land warrants. Congress later established a military district

in Ohio for the location of these warrants. Other military bounty land

reserves were established in Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas after the

War of 1812. In 1842, Congress began permitting veterans to select

public lands outside the military districts.

The policy of giving land bounties for military

service continued until the Civil War. War veterans were then given the

privilege of deducting all or part of their military service from the

period of residence and cultivation required under the Homestead

Act.

|

|

|

Private land claims were another concern for the

General Land Office. With each addition to the public domain, the United

States recognized land titles granted by previous sovereigns. This

required verifying claims and issuing patents to confirm titles.

|

|

Private Land

Claims |

|

Adjudication of private land claims was difficult.

Claims often conflicted and rights of ownership complicated by missing

documents. Fraudulent title papers were another problem. Sorting out the

titles required lengthy hearings to determine the legitimacy of the

claims.

The first claims came with the acquisition of the

trans-Appalachian frontier. With the purchase of Louisiana from France

the GLO was swamped with private claims given by both the French and the

Spanish. Thousands of claims were presented, most for lands in Missouri

and Louisiana. To expedite adjudication, Congress established land

commission boards, but the poor documentation for most title claims

slowed their confirmation. Several thousand claims remained outstanding

for more than 50 years.

|

|

|

THE POLICY OF PREEMPTION

|

|

|

The federal government's policy of auctioning public lands had

always placed frontier settlers at a disadvantage compared with monied

capitalists and speculators. Frontier farmers found money hard to

come by, forcing many to build a home, clear land, and eke out what income

they could on unsurveyed public lands.

|

|

Pioneer

Dilemma |

|

The policy of orderly settlement, however, sought to dissuade such

squatting activity. The Confederation used troops to

remove trespassers who had settled north of the Ohio River. The federal

government used the same tactic, and an 1807 law provided for the removal,

imprisonment, and fining of trespassers. These efforts, however, did little to deter the

squatters.

|

|

Action

Against

Squatters |

|

As surveys and sales progressed westward, squatter communities

formed "claim associations" to protect their interests and regulate

how lands were claimed and recorded. They also protected

members from "claim jumpers" and worked to intimidate anyone who dared bid against

a member's claim at auction.

|

|

Claim Clubs |

|

The government did, though reluctantly at first,

provide some of these settlers with relief by extending the privilege of

preemption. Preemption was the preferential right of an individual to

purchase, at the minimum price, public lands that he or she had

improved. The preemption concept had been used in southern colonies

prior to the Revolution, but the Confederation and federal government

initially rejected the practice in favor of selling lands for

revenue.

|

|

Preemption

Concept |

|

Frontier interests did not let the idea of preemption

lapse. Congress received petition after petition asking that the

privilege be allowed. In 1799, Congress gave Ohio settlers, who had been

duped by a speculator, the right to preempt the lands they had settled.

Limited rights of preemption were then granted to settlers in Indiana,

Illinois, Alabama, Mississippi, and other public land states and

territories. The first general grant of preemption came in 1830 but

applied only to those who had settled on public lands prior to the law.

The grant allowed claimants to enter 160 acres at the minimum price as

long as the right was exercised prior to the auction of a tract and

within 1 year of the law's passage. The law was extended temporarily

several times until 1841 when Congress passed a permanent preemption

measure.

|

|

Early

Preemption

Laws |

|

The Preemption Law of 1841 allowed "every person,

being the head of a family, or widow, or single man over the age of

twenty-one years," and who was a citizen or declared his or her intent

to become a citizen, the one time privilege of entering up to 160 acres

of surveyed public land at the minimum price per acre. The claimant, or

entryperson, had to reside on the tract entered and to have cultivated

the land. Public lands occupied as towns or places of trade, containing

known mines, or those reserved by the government, could not be

entered.

|

|

General

Preemption

Law |

|

This Preemption Law, in the words of historian Roy

Robbins, was a "frontier triumph." Congress had come to recognize the

plight of frontier farmers and had decided that allowing settlement of

the public domain was as important a consideration as the raising of

revenue. The new law allowed tens-of-thousands of farmers to obtain

title to the lands they had worked so hard at improving.

|

|

Frontier

Triumph |

|

THE GRADUATION PRINCIPLE

|

|

|

The rapid westward movement of the frontier bypassed

scattered tracts of public land. These were the less desirable

lands—rough and broken in character, often with inferior soils.

Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, a champion of frontier interests,

pointed out as early as 1824 that these "worthless" lands sold at the

same minimum price per acre as the best public lands—$1.25. The

Senator argued for years that these less desirable lands would sell only

if the price was reduced, and that reducing the price would actually

increase revenue to the government. Benton also wanted the lands sold to

the actual settlers rather than monied interests and speculators.

|

|

Forgotten

Lands |

|

In 1854, Congress adopted Senator Benton's proposal.

The Graduation Law provided that the less desirable lands open to

private entry for (a) more than 10 years be offered for $1 an acre; (b) more

than 15 years, 75 cents an acre; (c) 20 or more years, 50 cents; (d) more than 25 years, 25 cents;

and (e) over 30 years, 12-1/2 cents. Buyers had to live on or own a farm

adjacent to the parcel purchased, and no more than 320 acres could be

bought by any one individual.

|

|

Graduation

Law of 1854 |

|

The effects of the law were immediate. Public land sales in 1854

exceeded 7 million acres, a 700 percent increase over the previous year.

The figure more than doubled in 1855. Unfortunately,

speculators were again the beneficiaries through the use of fraudulent

entries, forcing Congress to repeal the law in 1862.

|

|

Graduation

Law Sales |

|

"FREE LAND" AND THE HOMESTEAD ACT

|

|

|

The Graduation and Preemption Laws helped placate frontier demands

for land but what pioneer farmers really wanted was

"free land." They argued that free land was their due. They transformed

the public lands from wilderness to farmlands. They were the bulwark against Indian

hostilities. And upon their efforts rested the country's economic, political, and

social strength.

|

|

Demand for

Free Land |

|

Congress had on occasion offered free land in regions the nation

wanted settled. The Armed Occupation Law of 1842 offered 160 acres of land

to each person willing to fight the Indian insurgence in

Florida and occupy and cultivate the land for 5 years. Between 1850 and 1853,

Congress offered 320 acres to single men and 640 acres to couples who had settled

in the Oregon Country or who migrated there. A similar, but less generous

proposition was extended in 1854 to include the New Mexico Territory.

|

|

Early Land

Donation

Laws |

|

Debate over a free land or homestead law began in the 1840s.

Frontier advocates of the homestead principle were joined by eastern labor

reformers who envisioned free land as a means by which

industrial workers could escape low wages, job insecurity, and deplorable

working conditions. Against the proposal were industrialists from the

Northeast who feared a homestead law would empty cities of workers and weaken their domination

over labor. The South also worried. The delicate political balance

between the slave and free states in the Senate could be undermined by

opening the undeveloped territories to small, independent farmers

opposed to slavery.

|

|

The

Homestead

Principle |

|

Despite opposition, support for the idea of homesteads increased

over time. In 1860, Congress finally passed a compromise measure whereby

settlers could purchase 160 acres at 25 cents an acre

if they resided on and cultivated their tracts for 5 years. President James

Buchanan, however, vetoed the legislation, stating that the law would

reduce public land revenues and undermine the present land system.

Furthermore, Buchanan thought the law was unconstitutional.

|

|

Homestead

Law Vetoed |

|

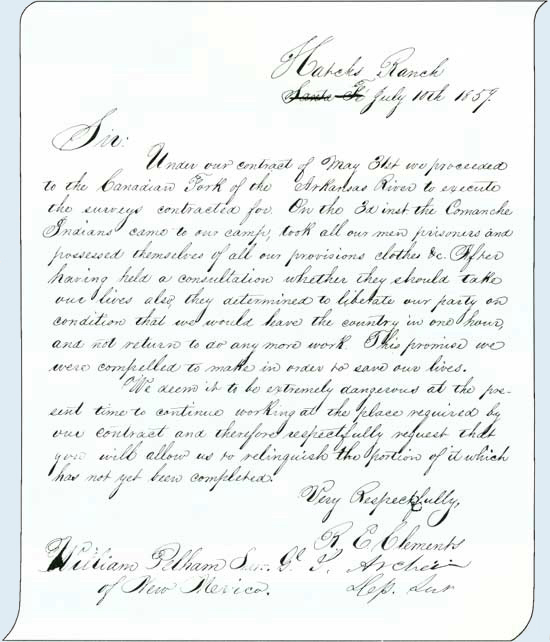

SURVEYING NEW MEXICO TERRITORY IN 1859

The men employed by the General Land Office to survey

the public lands in the 1800s were often on the cutting edge of the

frontier. In the wilderness these deputy surveyors and their crews faced

myriad dangers and many lost their lives. Indian problems were one

hazard often encountered by survey crews and in 1859 two surveyors wrote

the following about their near brush with death.

The Surveyor General of New Mexico granted this request. (National

Archives, Denver Branch)

|

|

|

The Republican Party's 1860 presidential platform called for passage

of a homestead measure. With Abraham Lincoln's election and

the South's secession from the Union, Republicans made good on

their promise. Under the Homestead Act of May 20, 1862, heads of households,

widows, and single persons over 21 years old could apply for 160 acres subject to

entry under the Preemption Law. Patent for the land would be issued after 5

years of residence and cultivation or, if applicants so

chose, they could commute their claim before the end of 5 years to a

cash entry, paying the minimum price per acre.

|

|

The

Homestead

Act |

|

|

Abraham Lincoln (Jennifer Reese)

|

|

|

|

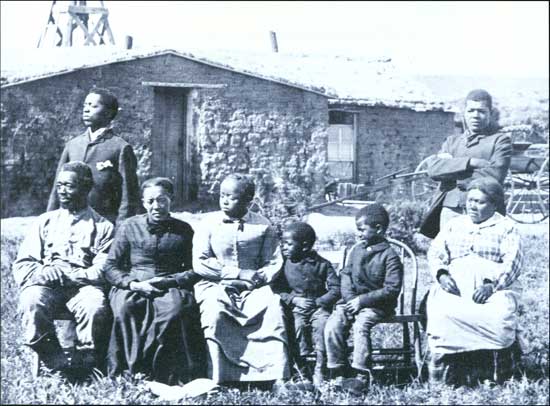

The Homestead Law was seen as a great democratic

measure by its supporters. The law, however, was but a promise; not

all could take advantage of it. The Homestead Law offered free land

but building of a home and breaking soil for crops took capital. The

environment also worked to defeat the dreams of many. Of the more than

1.3 million homestead entries filed before 1900, only about half would

go to patent.

|

|

Vision and

Reality |

|

|

Homesteading in Nebraska in 1887 (Denver Public Library Western

History Collection)

|

|

|

TOWNSITE LAWS

|

|

|

Congress also turned its attention to townsites on

public lands. As early as 1824, counties were allowed to preempt a quarter section

(160 acres) of land for county seats. In 1844 towns founded on the public lands

were allowed to preempt up to 320 acres, and in 1864 and 1867 Congress

enacted new provisions that permitted towns to take title to even larger

areas. Most communities established on the public lands did not take

advantage of the townsite laws, but cities such as Denver, Boise, and

Carson City did.

|

|

Townsite

Laws |

|

MINERAL LAND POLICY

|

|

|

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 caught

the United States without a general mineral land policy, and Congress

took no immediate steps to institute one. Miners, who quickly spread

their search for precious metals across the Pacific Coast and Rocky

Mountains, were forced to develop their own laws and regulations.

Prospectors organized mining districts and devised rules as to how

claims were staked and "title" was held. These rules were then enforced

by miner courts.

|

|

California

Gold Rush |

|

The government did have experience in dealing with

mineral lands. The Confederation had reserved a one-third interest in

all gold, silver, lead, and other minerals in the Land Ordinance of

1785. The federal government initially ignored the issue, only reserving

saline lands. But in 1807 it chose to reserve and lease public lands

valuable for lead in the Indiana Territory. The policy was extended to

Missouri and the Great Lakes region by 1816. The War Department, because

of the importance of lead in making rifle shot, administered the leasing

program, but found it could not cope with miners' resistance to

government oversight.

|

|

Early Mineral

Policy |

|

The leasing of lead deposits in Missouri ended in

1829. In 1845, President James Polk told Congress that the "system of

managing the mineral lands of the United States is believed to be

radically defective," costing the government more to administer than the

royalties it received. Congress agreed, and from 1846 to 1850, the lease

policy was abandoned in favor of the disposal of lead, copper, and iron

deposits in the Great Lakes region by preemption and sale.

Congress, however, avoided the mineral question in

the West. Presidents, Secretaries of the Interior, and General Land

Office Commissioners repeatedly asked for enactment of a policy—be

it lease, preemption, or sale—but Congress remained silent until

1866.

|

|

|

The first mining law was introduced by Senator

William Stewart of Nevada. As enacted, the Mining Law of 1866 declared

that "mineral lands of the public domain...be free and open to

exploration and occupation," and deal with the patenting of

lodes—claims containing gold, silver, or other precious metals

occurring in veins. Lode claims were subject to the customs and rules of

local mining districts, as long as they did not conflict with federal

law. The law also provided for the patenting of lode claims on which at

least $1,000 in actual labor and improvements had been completed. The

length of a claim could not exceed 200 feet and the miners could follow

the "dips, angles, and variations" of their lodes into adjacent

property. Metes-and-bounds surveys of the claims were to be made under

the direction of the Surveyor General, and the cost of patenting a claim

was $5 an acre.

|

|

Lode Mining

Law of 1866 |

|

In 1870, Congress passed a second mining statute,

this one pertaining to placer claims. The act defined placers as "all

forms of deposit, excepting, veins of quartz, or other rock in place."

Claims could be as little as 10 acres but no one person or association

of persons could have a single claim for more than a quarter section.

Claims had to conform with the legal subdivisions of the surveyed

townships, but metes-and-bounds surveys were allowed in unsurveyed

areas. The cost of patenting a placer claim was set at $2.50 an

acre.

|

|

Placer

Mining Law

of 1870 |

|

WILLIAM MORRIS STEWART -

"FATHER" OF THE MINING LAW

by William Condit

Mining Law and Salable Minerals, Washington Office

William M. Stewart (Jennifer Reese)

|

William Morris Stewart was the chief protagonist in

debates to secure passage of laws that recognized the governance system

miners had established by organizing into mining districts in the remote

and largely lawless West.

Born in upstate New York in 1827, Stewart turned to

study law in 1849 and went off to Yale to pursue a degree. He quit

school the next year to join the rush to the California gold camps.

There he engaged in gold mining, but with little success. Stewart again

turned to study law and was admitted to the California bar in 1852. Two

years later he became Attorney General of California.

In 1860, news of the fabulous silver discoveries on

the Comstock Lode drew him to Virginia City in the Nevada Territory. For

the next several years Stewart represented mining interests in fierce

litigation battles over possessory rights to portions of the Comstock

Lode. By all accounts he was domineering in the courtroom, a trait that

served him well later in life. (Stewart allegedly waved a gun while

interrogating a witness of "questionable veracity"!)

Based on his accomplishments in territorial politics,

Stewart was elected to serve as one of Nevada's first U.S. senators.

Stewart proved an eloquent "apologist" for lode and placer miners

occupying the public lands in technical trespass. Since no federal

statute authorized the settlement and mining of mineral lands, he

championed their system of self-governance. He believed "free mining" by

U.S. citizens should be encouraged by enactment of a law granting

patents to the discoverers of mineral wealth who diligently worked their

deposits under the rules of their mining districts.

After the Senate was persuaded, only the powerful

chairman of the House Committee on Public Lands, George Julian of Ohio,

stood between Stewart and passage of a lode law. Julian could bottle up

the bill in committee indefinitely. Stewart out-maneuvered his foe by

substituting his lode bill for one that had already passed the House,

dealing with rights-of-way for ditch and canal owners on public land.

Upon Senate passage, it was sent back to the House where Julian was

unsuccessful in having the bill referred to his committee. On July 28,

1866, the full House of Representatives passed Stewart's bill by a vote

of 77 to 34, a remarkable margin considering that most seats were held

by eastern congressmen who were expected to support legislation that

produced federal revenues from the public land.

In 1870, Stewart sought to persuade Congress that

placer miners on the public lands needed similar legislative recognition

of their possessory rights and an opportunity to patent their claims.

Julian continued to protest "free mining" policies but to no avail;

Congress went with Stewart's views again. On May 10, 1872, Congress

merged the lode and placer statutes and made technical amendments, such

as granting defined preemptive rights to lode claimants for the

discovered lode and the area of land flanking the lode.

|

|

|

Congress restated its mining policy in 1872 with the

passage of the General Mining Law. This law declared that "valuable"

mineral deposits rather than simply "mineral deposits" as stated in the

Lode Mining Law of 1866, were to be "free and open to exploration and

purchase." Local mining customs were still recognized. Lode locations,

however, could be no more than 1,500 feet long and 600 feet wide.

Furthermore, individual claimants were limited to 20 acres, while

associations or groups could still have 160-acre claims. To protect

their claims from others, claimants had to perform $100 of assessment

work yearly and show at least $500 worth of improvements before the

claims could be patented. Milling or processing sites could be entered

on nonmineral lands but could not exceed 5 acres. Survey requirements

and the per-acre cost of patenting a claim remained the same as

before.

|

|

General

Mining Law

of 1872 |

|

|

Placer Mining at Cripple Creek, Colorado in 1893 (State Historical

Society of Colorado)

|

|

|

The enactment of the mining laws transformed miners

from trespassers into legitimate occupants of the public lands. Valid

claims were given a status akin to private property. More important, the

development of minerals on the public lands was given priority over

other possible land uses.

In 1873 Congress provided for the sale of public

lands valuable for coal deposits. The law replaced an 1864 statute that

offered coal lands at auction for no less than $20 an acre and an 1865

law that permitted miners who had developed coal deposits prior to

enactment to preempt their mines. Neither law had been effective. The

new statute was intended as a remedy,

providing for the location, development, and preemption of 160 acres to

individuals and up to 640 acres to associations that had spent at least

$5,000 in development. The minimum price was set at $20 an acre if the

claim was within 15 miles of a railroad and at least $10 an acre, if

further out.

|

|

Coal Lands

Law of 1873 |

|

GEOLOGICAL SURVEYS

|

|

|

After the Civil War, Congress began funding scientific and geologic

explorations of the West to further encourage mineral development of

public lands. Ferdinand Hayden, Clarence King, Lieutenant

George Wheeler, and John Wesley Powell conducted expeditions

over large areas of the Great Plains, Rocky Mountains, and Great Basin, mapping the

terrain and describing the resources. In 1879, Congress consolidated

these independent efforts into one organization, the U.S. Geological

Survey.

|

|

Early

Exploration |

|

The Geological Survey was responsible for "the classification of the

public lands and examination of the Geological Structure,

mineral resources and products of the national domain." Under its first

Director, Clarence King, and his successor, John Wesley Powell,

the Geological Survey established itself as a competent, scientific

organization. Its studies

became highly valued by private industry and the General Land Office

came to depend on its geologic and hydrographic knowledge.

|

|

U.S.

Geological

Survey |

|

STATE AND RAILROAD LAND GRANTS

|

|

|

Congress shared the bounty of the public domain with

more than miners and settlers. Soon after passage of the Homestead Act,

it provided immense grants of lands to the states and railroad

corporations.

|

|

|

The Morrill Act of 1862 provided each state within

the Union 30,000 acres of public land for each senator and

representative to finance agricultural and mechanical arts colleges.

States with public lands chose the acreage from the public lands within

their boundaries. States having no public land, or little remaining

acreage, were given scrip. Scrip, which was issued in 160-acre

increments and sold to private parties by the states, could be used to

locate and pay for any nonmineral public lands open to sale or private

entry. From this grant, schools such as Cornell and Illinois State

University were established.

|

|

Public Lands

for Colleges |

|

By providing lands to the states for the

establishment of agricultural colleges, Congress was simply continuing

its tradition of granting public lands for schools. The Confederation,

in the Land Ordinance of 1785, had reserved Section 16 in each township

to finance public education in the Ohio Country. The federal government

reinstituted this practice when it admitted Ohio into the Union in 1802.

The practice was continued with other states, partly to placate them for

having to disclaim any right, title, or interest to the public lands

within their boundaries. After 1848, states received two sections of

land from each township, which increased to four sections with the

admission of Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico.

|

|

Early Grants

in Aid of

Education |

|

Congress also provided public lands to the states to

finance institutions such as schools for the deaf and blind, and prisons.

Most important to the economic development of the public land states

were the grants for internal improvements. Under the land grants, roads

and canals could be built and waterways improved. In 1841, Congress

granted each of the public land states 500,000 acres of land for such

purposes. Congress also gave lands classified as swamp and overflow to

various states prior to the Civil War.

|

|

Internal

Improvement

Grants |

|

The day before President Lincoln signed the Morrill

Act, he approved a law granting lands to aid the construction of the

first transcontinental railroad. Congress gave the Central Pacific and

Union Pacific railroad companies "every alternate section of public

land, designated by odd numbers, to the amount of five alternate

sections per mile on each side of said railroad, on the line thereof,

and within the limits of ten miles on each side of said road." In 1864,

the grant was increased to 20 alternate sections for each mile of track.

Lands reserved by the United States, to which a preemption or homestead

claim had been attached at the time the railroad's route was fixed, were

excluded, as were all mineral lands except those known to be chiefly

valuable for iron or coal.

|

|

First

Transcontinental

Railroad

Land Grants |

|

Before the Central Pacific and Union Pacific grant,

Congress had given public lands to the states to encourage railroad

construction. The practice began in 1850 with the Illinois grant for the

Illinois Central Railroad and extended to other states in the Midwest

and South in the decade that followed. But with few states between the

Missouri River and the Pacific Ocean, and a vast territory to be

crossed, a new policy for granting lands directly to railroad

corporations became necessary.

|

|

Early

Railroad

Land Grants |

|

|

Limits of the railroad land grants

|

|

|

The Central Pacific and Union Pacific grant was

followed by others. The largest went to the Northern Pacific Railroad

Company, which built a line from Lake Superior to Puget Sound. Northern

Pacific received 20 odd numbered sections for each mile of right-of-way

across states and 40 odd numbered sections for each mile across the

territories. The massive grant, if it had been entirely fulfilled, would

have provided 47 million acres of public land to the company, more than

twice the acreage provided for the first transcontinental route. From

1862 to 1871, Congress granted nearly 128 million acres to corporations

for the construction of railroads.

|

|

Northern

Pacific

Railroad

Land Grant |

|

These multimillion-acre "checkerboard" empires came

under criticism in the late 1860s. Many westerners raised the cry of

monopoly as railroads failed to bring their lands to market; the people

demanded that the public lands be reserved for actual settlers. They

called for an end to the grants and for the forfeiture of unearned and

unsold land grants. Congress responded at first by placing "homestead

clauses" on any railroad land grant legislation that required companies

to sell their grants in quarter-section tracts for $2.50 an acre to

actual settlers. After 1871, Congress refused all further railroad land

grants. Legislation on forfeiture came years later, but few land grants

were revoked as a result.

|

|

End of

Railroad

Land Grant

Policy |

| Selected Railroad Land Grants as of 1941 |

| Company | Acres |

| Central Pacific | 11,199,560 |

| Union Pacific | 19,156,460 |

| Santa Fe Pacific (Atlantic & Pacific) | 11,595,341 |

| Northern Pacific | 39,064,567 |

| Southern Pacific | 7,907,966 |

| Oregon and California | 2,777,632 |

|

|

|

NEW LAND LAWS FOR THE WEST

|

|

|

As if settlers did not already have enough

competition for public lands, Congress continued to auction lands after

passage of the Homestead Act. Congress ordered millions of acres to

market in Wisconsin, Nebraska, Kansas, California, and other states and

territories. Good agricultural lands were offered at many of these

auctions. But, after 1870, Congress was reluctant to put any more public

lands up for auction.

|

|

Land Sales

After

Homestead

Law |

|

The Congressional reluctance to sell public lands

coincided with an effort to expand settlement opportunities. By the

Timber Culture Law of 1873, 160 acres could be entered by anyone

interested in planting and growing trees on land naturally devoid of

timber. The Timber Culture Law responded to the common belief that trees

would bring rain to the semiarid West. Forty acres had to be planted in

trees, with the trees set no farther than 12 feet apart. No residence

was required and patent would pass if the trees had been kept in

"healthy, growing condition for ten years." Amendments

to the law in 1874 and 1878 reduced the acreage

planted to 10 acres and permitted patenting within 8 years.

|

|

Timber

Culture Law

of 1873 |

|

The Desert Land Law was passed in 1877. It applied to

public lands "exclusive of timber lands and mineral lands which will

not, without irrigation, produce some agricultural crop." Entry could be

made for a full section (640 acres), at a cost of $1.25 per acre, and

patents if irrigation was accomplished within 3 years. The law applied

only to the States of California, Oregon, and Nevada, and to the

Territories of Washington, Idaho, Utah, Dakota, Montana, Arizona, New

Mexico, and Wyoming. The State of Colorado was included in 1891. Like

the Timber Culture Law, no residence was required.

|

|

Desert Land

Law of 1877 |

|

Congress had enacted the Timber Culture and Desert

Land Laws to give settlers flexibility. Both laws recognized that the

public lands west of the 100th Meridian were semiarid in character and

that settlers needed more land than east of the meridian for successful

farming operations to be established. The laws allowed settlers to

acquire up to 1,120 acres when used in conjunction with the Preemption

and Homestead Laws.

|

|

Timber

Culture and

Desert Land

Law in

Operation |

|

Proving up—successfully patenting

lands—under the Timber Culture and Desert Land Laws, however, was

difficult. The Timber Culture Law, after its amendment in 1878, required

claimants who had entered 160 acres to have 6,750 trees in "living (and)

thrifty" condition at the end of 8 years. In the semiarid West this was

difficult to achieve, and only 65,000 of the 260,000 entries filed under

the law were patented under the tree planting provisions of the law.

Success under the Desert Land Law was little better.

Construction of irrigation works was expensive and most settlers found

they could not comply with the requirements of the law. Many settlers

responded to the situation by resorting to fraudulent methods of proving

up on their claims.

Fraud was also used with the Timber Culture and other

laws. The situation became so bad that much of the work in the General

Land Office became more and more concerned with the detection and

prosecution of fraudulent claims.

|

|

|

LAND FRAUD

|

|

|

Fraud, as stated previously, had been a problem since

the creation of the public domain. By the 1870s, evidence of the

illegal appropriation of the public lands and resources became

pronounced. In 1879, Congress created the first Public Lands Commission

to look into how the land laws might be revised but then paid little

attention to the recommendations.

|

|

First Public

Lands

Commission |

|

In his annual report for 1882, Commissioner of the

General Land Office Noah McFarland noted that investigations by his

bureau had found "that great quantities of valuable coal and iron lands,

forests of timber, and the available agricultural lands in whole regions

of grazing country have been monopolized." Mineral, livestock, and

timber companies had people make entries under the Preemption and

Homestead Laws and then purchased the claims after patenting

requirements had been met so they could amass large

landholdings. The Timber Culture Law was used by

speculators to secure interests in lands they knew later settlers would

buy. Stockraisers used the Desert Land Law to control access to streams

and rivers. They also fenced public lands to exclude other ranchers and

settlers from rangelands they used. In Colorado alone, 3 million acres

were fenced.

|

|

Commissioner

McFarland

and Land

Fraud |

|

THE BEAUBIEN-MIRANDA (MAXWELL)

MEXICAN LAND GRANT

By Andrew Senti

Realty Specialist, Colorado State Office

Editor's Note: The United States has, with each

acquisition of the public domain, recognized

land titles granted by the previous sovereign. Of the

thousands of private land claims and

grants patented, those in New Mexico and California

were the largest and among the most complicated to adjudicate.

The Beaubien-Miranda grant (within present Colorado

and New Mexico) had its origin in a brief period when the territory was

under Mexican rule. On January 8, 1841, a fur trader of French-Canadian

ancestry named Carlos Beaubien and Guadalupe Miranda, a Mexican citizen,

filed a petition with the Civil and Military Governor of New Mexico

asking for a grant of land that they promised to settle and develop. The

grant given to Beaubien and Miranda was the largest of several large

private land grants approved by Mexican officials in 1843-1844.

The grant consisted of a 1,714,765-acre tract of land

in the County of Taos. Its boundaries were described by a

metes-and-bounds description that used natural boundaries — streams,

mountain ranges, etc. A portion of the grant's boundary description went

as follows: "commencing below the junction of the Rayado and Red Rivers

from thence in a direct line to the east to the first hills from thence

following the course of the Red River in a northerly direction to the

junction of Una de Gato with Red River."

The grant to Beaubien and Miranda far exceeded the 11

square leagues (44,800 acres) allowed under Mexican law. In historical

perspective, these large, rather hastily processed grants appear to have

been an attempt to foster occupancy along the vulnerable northern and

eastern boundaries of the Mexican Territory and encourage settlement and

at least agricultural development.

Beaubian sold his half of the grant in 1858 to Lucian

B. Maxwell, an American who had married Beaubian's daughter in 1842. It

thereafter became commonly known as the Maxwell Grant.

By the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848, the

United States acquired New Mexico and pledged to recognize the land

grants made by the Mexican government. The General Land Office

recommended patenting of the Maxwell Grant in 1857. Congress confirmed

the grant on June 21, 1860. but conflicting claims of interest in the

grant by others, delayed final confirmation of the grant by the U.S.

Supreme Court until 1887.

Perhaps some of the ordeal of confirming the Maxwell

and other land grants can be attributed to centuries-old Spanish

philosophy toward land tenure that clashed with Anglo-American

attitudes. Anglo-American thought leaned toward economic aspects, while

Spanish social and political thought valued land as a territorial

dimension of society. Anglo-Americans found this difficult to

understand.

|

|

COMMISSIONER WILLIAM A. J. SPARKS

CONFRONTS PUBLIC LAND FRAUD

Annual Report of the Commissioners of the General

Land Office, 1885

William A. J. Sparks (Jennifer Reese)

|

At the onset of my administration I was confronted

with overwhelming evidences that the public domain was being made the

prey of unscrupulous speculation and the worst forms of land monopoly

through systematic frauds carried on and consummated under the public

land laws.

In many sections of the country, notably throughout

regions dominated by cattle raising interests...entries were chiefly

fictitious and fraudulent and made in bulk through concerted methods

adopted by organizations that had parceled out the country among themselves

and inclosures defended by armed riders and protected against immigration

and settlement by systems of espionage and intimidation.

In other cases...individual speculation, following

the progress of public surveys, was covering townships of agricultural

land with entries made for the purpose of selling the claims to others,

or by entries procured for the acquisition of lands in large bodies. Again,

in timbered regions, the forests were being appropriated by domestic and

foreign corporations through suborned entries made in fraud and evasion of

law. Newly-discovered coal-fields were being seized and possessed in

like manner.

The question of my own duty, as the administrative

officer immediately charged under the law with seeing that the public

lands were disposed of only according to law, was at once forced upon

me. Should I continue to certify and request the issue of patents by

the President indiscriminately upon entries which there was every

reasonable ground to believe were fraudulent...or should I withhold

such final action until examinations could be made and the false claims

separated from those that were valid? Should I disregard cumulative

evidences of the universality of fraudulent appropriation of public

lands and become an official instrumentality of their consummation, or

should I say: "I mean to know what I am doing before I ask the President

of the United States to sign any more land patents?"

As a measure...of indispensable precaution I notified

the several divisions...that final action should be suspended upon

entries made in states and territories in which the greater degree of

fraud had been developed, and where the larger disposable area of public

lands remained.

This notification, or order, was not expected to be

acceptable to those whose purposes it is falsely and fraudulently to

acquire title to public lands, nor to those whose profitable vocation

was to promote the speedy obtainment of patents for compensation for

fee. It was a public measure in the public interest...intended to

check...conspiracies against the government.

I have caused lists of suspended entries to be

placed in the hands of special agents for examination and report,

and am convinced that it is not safe to issue patents or pre-emption,

commuted homestead, and other entries in which fraud most largely

prevails without such examination.

|

|

|

McFarland established a corps of agents to

investigate illegal entries and fencing. The new agents joined others

already assigned to investigating illegal timber cutting. These agents,

however, were few; a single investigator was often responsible for an

entire state or territory, limiting what could be accomplished. To help,

the Commissioner called for the repeal of the Preemption and Timber

Culture and the other land laws being fraudulently used. He also called

for enactment of an anti-fencing statute, the only request Congress

acted on.

|

|

|

McFarland's successor, William A. J. Sparks,

continued the fight against fraud. Sparks saw illegality everywhere. To

combat it, he suspended all pending patent applications under the

various land laws and began reinterpreting the land laws and their

requirements to prevent their misuse.

|

|

Commissioner

Sparks and

Land Fraud |

|

The new Commissioner was joined in his crusade

against fraud. His New Mexico Surveyor General, George Julian, also

railed against illegal practices. Julian was particularly concerned

about private land grant claims made by Spain and Mexico. Charged with

adjudicating these claims, the Surveyor General of New Mexico found many

of the claims to be forgeries or excessive in the lands they

included.

The zeal of Sparks and his lieutenants brought

protests. The Cheyenne Sun in 1887 derided the Commissioner by

declaring that the West "shalt have no other god than William Andrew

Jackson Sparks, and none other shalt thou worship." Such protests became

too much for President Grover Cleveland and he eventually had to ask for

Sparks' resignation.

|

|

|

The efforts of McFarland and Sparks had a telling

effect on fraud. While not eliminating it, they reduced fraudulent

activity on the public lands. The two commissioners also clearly brought

the problem to the attention of Congress. Public land law reform was

needed, and Congress, always slow to react on land matters, did

eventually react. In 1890, individuals were restricted from acquiring

more than 320 acres of public land. Under the General Public Lands

Reform Act of 1891, Congress stopped auctioning public lands under the

Land Law of 1820, repealed the Timber Culture and Preemption acts

(though not without some saving clauses), and reduced Desert Land

entries to 320 acres.

|

|

Public Land

Law Reform |

|

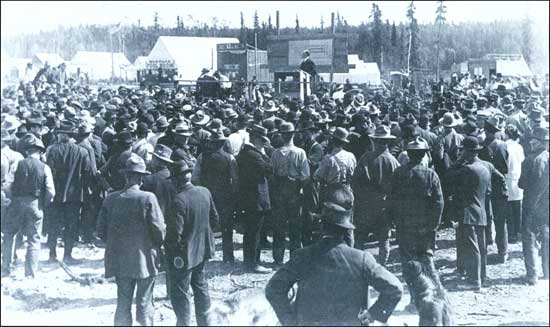

LAND RUSH IN OKLAHOMA TERRITORY

by Anthony Rice

From OUR PUBLIC LANDS (Summer 1976)

Editor's Note: In 1889 the opening of Indian lands in

Oklahoma Territory to homesteaders began. Early openings provided

opportunities for settlers to race for homestead tracts. The last "rush"

came with the opening of the 6,500,000-acre "Cherokee Strip" in 1893.

Among the 45 clerks hired by the General Land Office to handle homestead

applications was Anthony Rice, who wrote the following account of his

experience of the Cherokee Strip.

It was a "Public Land Opening," in its wildest sense.

I will attempt to describe it as I saw [it] and as it in reality was.

In order to prevent parties who had no rights under

the homestead laws from entering the land and thereby defeat the chances

of those who were entitled thereto, the "booth" or registration system

was adopted. Accordingly, nine booths were established, five of which

were on the northern and four on the southern line of the [Cherokee

Strip].

The booths were open from September 11 to September

19, 1893, between the hours of 7 A.M. and 6 P.M. Over 115,000 persons

registered, while the lands fit for homesteading would provide for only

about 20,000.

I registered a blind man and in order to satisfy my

curiosity, I inquired of his guardian what possible chance the poor

fellow had in this wild scramble and how he proposed to make the race.

The guardian replied that he would stand him on the line and as soon as

the gun was fired, he would make one jump and plant his flag. I am

afraid that this fellow, if he got in front of that crowd, was himself

planted, instead of the flag.

The hardships endured were indescribable. Persons

slept on the line for two and three days, waiting to be

registered....And all this was endured for what? In the bare hope of

realizing that which is so characteristic of our present speculative

generation — the desire to get "something for nothing."

At high noon on September 16, 1893, the soldiers fired

their guns and off started the greatest and most wonderful race of all

times. About 150,000 persons went pell mell, helter skelter. Some went

on horseback, some in vehicles of every conceivable description, some by

train and some on foot.

The trains were loaded. Every inch of the roofs were

covered and many hung on the sides of the cars by holding to the window sills, while the

open windows furnished room for some.

You have often heard of doing a "Land Office

Business." We did it there.

(BLM)

|

|

|

THE DWINDLING PUBLIC DOMAIN

|

|

|

By 1891, the public domain was rapidly diminishing.

In 1887, Congress, seeking to satisfy the nation's hunger for land, had

adopted a policy of giving individual farms to reservation Indians and

opening the remaining Indian lands to settlers. The Great Sioux Indian

Reservation in South Dakota, Chippewa lands in Minnesota, and the famous

"land rush" openings in Oklahoma, were among the many Indian

reservations opened to settlers. But the opening of Indian reservations

did little to alleviate the increasing demands.

|

|

Opening

Indian Lands |

|

Questions of how and to whom public lands would be

allocated became increasingly divisive; competing interests struggled to

gain control of the lands and resources they needed. This was

complicated by the federal government's more active role in

administering the use of public lands and resources, as the idea of

conservation began sweeping the nation.

|

|

|

THE COMING OF CONSERVATION

|

|

|

Early conservation efforts focused on public timberlands.

When Americans moved west from the Appalachian

Mountains pioneers gave little thought to conserving forests. Forests were an

impediment to progress. Trees were everywhere and made the clearing of land

for farming difficult.

|

|

Early

Attitudes

Toward

Timberlands |

|

The federal government disposed of these timberlands like any

others. Most forested areas east of the Mississippi River were sold at

auction. Agricultural lands with timber could be settled under

provision of the Preemption and Homestead Laws. In 1878, Congress

passed the Timber and Stone Law providing a quarter-section of land chiefly

valuable for timber or stone at the minimum cost of $2.50 an acre. Until

1892, the law applied only to California, Nevada, Oregon, and

Washington; afterwards it included all the public land states.

|

|

Timber and

Stone Law of

1878 |

|

Timberlands were quickly disappearing by the late 1800s. Many areas

around the Great Lakes had been clear cut and timber

production in the South was rapidly increasing. Fear arose that the

nation would soon have no more forests and calls for conserving what timberland remained began to

be heard.

|

|

Timber

Famine Scare |

|

The first response to this concern came with passage of the General

Public Lands Reform Law of 1891. The last section of the law allowed

the President to withdraw and reserve public lands "wholly or