OPPORTUNITY AND CHALLENGE

The Story of BLM

|

|

|

THE SEARCH FOR AN IDENTITY:

The Bureau of Land Management, 1946-1960

"I frankly say...that the very title of the bureau raises a very big

question mark in my mind. It seems to me that the very purpose to be

subserved is to change the historical policy of the United States from

one of holding the public lands for transfer to ownership under private

persons, to one of proprietary handling on the part of the United States

government."

—U.S. Senator Guy Cordon, Oregon

Congressional Record, July 13, 1946

|

THE SEARCH FOR AN IDENTITY

The Bureau of Land Management, 1946-1960

|

|

|

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) from 1946 to 1960

was an agency in search of an identity. The executive reorganization

creating the Bureau simply merged the General Land Office (GLO) and

Grazing Service. BLM had no new mandate, only the authorities and

functions of its predecessors.

The first years found the agency struggling to

survive. It was hindered in its organization effort and haunted by the

Grazing Service's fee increase debacle. There was serious question as to

whether the agency would survive.

|

|

Overview |

|

In 1948, a new Director, Marion Clawson, brought life

to BLM. Clawson laid the foundation for effective public land and

resource management. BLM decentralized administrative and resource

management functions, recognized resource interrelationships, and

stressed the importance of land classification and planning to multiple

use management.

Clawson was succeeded in 1953 by Edward Woozley. The

new Director's conservation philosophy differed from that held by

Clawson, but the basic thrust of better management through

decentralization and multiple use development remained. By the end of

Woozley's 8-year tenure, BLM had matured into a professionally competent

land managing agency.

|

|

|

THE MERGER

|

|

|

The Bureau of Land Management came into being when

the General Land Office and Grazing Service ceased to exist—the

direct result of the Reorganization Plan No.3 Act of 1946. To head the

new agency, a Director was to be appointed by the Secretary of the

Interior. Unlike predecessors in the GLO and Grazing Service, who were

presidential appointees, the new agency chief was to be selected under

the classified civil service system. Also to be appointed were an

Associate Director and "so many Assistant Directors...as may be

necessary."

|

|

Reorganization

Plan No. 3

Act of 1946 |

|

The Reorganization Plan, however, did not provide a

mandate for the newly formed agency. BLM was simply placed under the

Secretary of the Interior and "the functions of the General Land Office

and Grazing Service...consolidated to form a new agency." The Bureau,

therefore, had to continue administering the public lands using the

outmoded and often conflicting mandates of the 3,500 laws passed during

the previous 150 years. The major statute directing BLM activities was

the Taylor Grazing Act, which provided for the administration of grazing

"pending final disposition" of the public lands. 'This [was] hardly

a firm basis," as natural resources professor Sally Fairfax points out,

"for a comprehensive land planning management scheme."

|

|

No Mandate |

|

Another problem facing the Bureau was the integration

of the General Land Office and Grazing Service into one organization.

BLM resulted from a merging of the oldest federal agency with one of the

youngest—two agencies with different organizational structures and

philosophies. GLO was centralized, with most authority placed with the

commissioner; the Grazing Service was decentralized. The General Land

Office handled a variety of resources, while the Grazing Service dealt

primarily with range management. Creating a new organization out of

these two agencies posed a challenge.

|

|

GLO and

Grazing

Service

Differences |

|

THE EARLY YEARS

|

|

|

BLM struggled in its first two years to simply

survive. A new organizational structure was outlined, but attempts to

put it in place were hindered by congressional opposition. The nightmare

of the Grazing Service appropriations debacle also haunted the

agency.

|

|

|

Fred W. Johnson, who had been Commissioner of the

General Land Office, was selected by Secretary of the Interior J. A.

Krug in 1946 to be the Bureau's temporary Director. Johnson was in poor

health and did not promise to be an effective leader, but Krug

undoubtedly felt selecting the Grazing Service's Clarence Forsling would

only have continued congressional attacks. To assist Johnson, Krug

turned again to the former GLO. He appointed Joel D. Wolfsohn, the

former Assistant Commissioner who had directed GLO activities for

Johnson, to be Acting Associate Director, and Thomas Havell, a long-time

GLO employee having good relations with Capital Hill, to be temporary

Assistant Director. To Wolfsohn and Havel would go the task of molding

BLM into an agency.

|

|

BLM's First

Director |

|

|

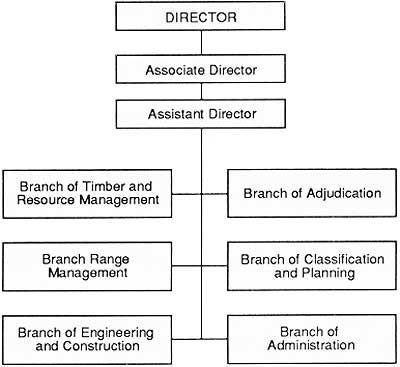

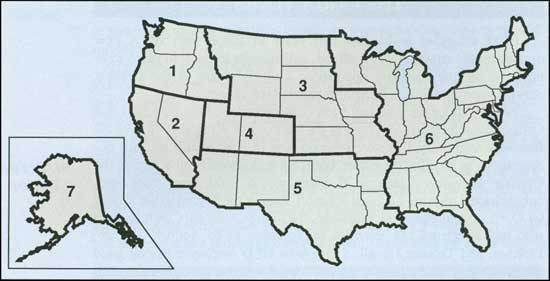

BLM organizational structure in 1946

|

|

|

|

BLM's organization called not only for the

integration of General Land Office and Grazing Service functions and personnel,

but also for improved public land administration and public service

through decentralized operations. A three-tiered organization was

outlined which featured a Washington office headquarters and regional

and district field offices. Headquarters arranged itself around the

Bureau's major functions— range management, timber management, land

and mineral adjudication, classification and planning, survey and

engineering, and administrative services. The field offices were

organized around the Grazing Service's district office system, as well

as the GLO's Oregon and California (O&C) forestry offices and land

and survey offices. With this type of organizational structure, the

agency could maintain on-the-ground management of public lands and

resources; public land users could get on-the-spot handling of

administrative matters.

|

|

BLM's

Organization |

|

|

BLM regions in 1946

|

|

|

The key to BLM's proposed organization, however, was

the regional offices. The Bureau of Land Management hoped, as director

Johnson stated, to furnish "better service...through regionalized

handling of cases...affording wider opportunity than ever before for

resource development under prudent conservation safeguards." This meant

delegating Washington office adjudication functions to regional

administrators.

|

|

|

Seven regional offices were established, each

responsible for more than one state. These were used in place of the

single-state setup employed by the Grazing Service so that state

political and economic interests could not dominate regional personnel.

Congress, however, prevented the transfer of responsibilities from

Washington, arguing that the Bureau's regional offices would strengthen

bureaucratic control over public lands and user groups and hinder

congressional oversight of the agency's actions. Therefore, in the

Interior Appropriations Act of 1947, Congress banned the "transfer or

removal of any function or duties...heretofore held and administered in

[Washington]...unless specific approval [had] been given by

Congress."

|

|

Congressional

Opposition to

BLM

Organization |

|

Congress addressed another major concern in the

Appropriations Act. The very name of the agency—the Bureau of Land

Management—aroused suspicion among some western politicians. They

believed, as Senator Guy Cordon of Oregon did, that the agency's title

implied abandoning the nation's long-held policy of transferring public

lands to individuals and private interests in favor of a policy of

federal retention and proprietorship. Congress, consequently, directed

Bureau funds be used for the "disposal," as well as the management and

protection of, public lands, something that had not been done in recent

General Land Office and Grazing Service appropriations acts.

|

|

|

The Bureau's organizational efforts also suffered

from the Grazing Service fee increase controversy. Congressional

appropriation cuts gutted the range management program. With 86

personnel to oversee 150 million acres of grazing land, BLM could not

effectively process grazing applications, monitor range conditions,

prevent trespass, or build range improvements.

|

|

Solution to

Grazing Fee

Controversy |

|

The grazing district advisory boards, fearing a

breakdown of order on the public range, stepped in. Using monies

received from Taylor Grazing Act fees for range improvements, the

advisory boards paid the salaries of BLM range employees. Having the

advisory boards pay agency employee salaries put the Bureau in an

awkward position. "In effect," as political scientist Phillip O. Foss

notes, "the regulators were being supervised by those who were to be

regulated." BLM needed to be independent if it was to perform its duties

properly.

|

|

|

Secretary of the Interior Krug understood this. From

talks with western livestock interests, he knew that ranchers would

accept a slight grazing fee increase. To study the situation, Krug

appointed California rancher Rex L. Nicholson. Nicholson concluded that

BLM needed only 242 people to adequately manage the public range. He

recommended increasing the grazing fee from 5 cents to 8 cents per

animal unit month (AUM). Two cents were to go for range improvements,

with the remaining 6 cents to be distributed between the states and the

Federal treasury. The federal government's share of the fee covered 70

percent of range administration costs—those functions benefiting

only users. The remaining 30 percent— programs of general public

good—would be funded by Congress. The National Advisory Board

Council accepted Nicholson's formula and, in 1947, Congress gave its

approval to the grazing fee increase and distribution plan.

|

|

The

Nicholson

Plan |

|

The plan, however, did not help BLM. Congress could

not adequately fund programs not covered by grazing fees. This, and the

fact that Nicholson's administrative cost estimates were too low, left

the Bureau's range management program little better off than before.

Thus, the Bureau's beginnings were not auspicious.

Its inability to implement an organizational structure and secure

adequate funding made it ineffective. Secretary of the Interior Krug

called BLM "one of the...worst run Bureaus" within his Department.

Employee morale was low. Many employees, particularly in Washington,

looked upon their work as simply a job, and few had a sense of

dedication. The future looked bleak, but a new Director would soon turn

the situation around.

|

|

MARION CLAWSON: A SENSE OF MISSION

|

|

|

The Bureau of Land Management was invigorated in 1948

with the appointment of a new Director. Western ranchers and

congressional supporters did not feel Fred W. Johnson was sufficiently

attuned to their needs and demands. Secretary of the Interior Krug

agreed new leadership was needed but rejected suggestions of livestock

interests for a new Director. He wanted someone who would be accepted by

stockraisers, yet would exercise independence. He turned to Marion

Clawson.

|

|

Search for

New

Leadership |

|

Clawson was BLM's regional administrator in San

Francisco. He had joined BLM in 1946 after many years with the

Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Agricultural Economics. A Nevadan,

Clawson had an undergraduate degree in agricultural economics from the

University of Nevada and a doctorate in economics from Harvard. He also

understood the ranching business. His father had a small ranch in Nevada

and his dissertation at Harvard had been on the economics of the western

livestock industry.

|

|

Director

Marion

Clawson |

|

Clawson did not think his work at BLM was challenging

and was disheartened by the agency's inability to decentralize and

secure adequate funding for its programs. He was searching for other

work when Joel Wolfsohn, who was resigning, asked him if he wanted the

Associate Director position with BLM. Clawson declined, commenting that

he would not be able to accomplish anything unless he was Director. Soon

afterwards, Interior Secretary Krug offered him the directorship.

|

|

|

The Secretary bluntly told Clawson that he considered

the Bureau of Land Management to be poorly managed. Krug made it clear

to Clawson that the agency needed new blood if change was to be made.

Clawson had his mandate—to transform BLM.

|

|

Mandate for

Change |

|

Clawson's first task was to reorganize the Bureau.

Assistant Director Thomas Havell had to go because of his "old GLO"

attitude. So did the chiefs of most of the branches. Clawson replaced

these people with individuals from outside BLM. For Assistant Director,

and later Associate Director, he selected Roscoe Bell, who had worked

many years in the Department of Agriculture. Clawson filled a number of

other positions with people he had known in the Bureau of Agricultural

Economics.

|

|

|

Director Clawson pursued decentralization. He

believed strongly that decentralization was essential if BLM was to

become effective, efficient, and responsive. Clawson convinced Congress

in 1948 to remove most of its restrictions against delegating authority

to the regional administrators. The next year, no restrictions were

imposed; by the end of fiscal year 1949, 85 percent of the Bureau's

adjudicative functions had been decentralized to the regional and

district offices.

|

|

Decentralization

of BLM

Functions |

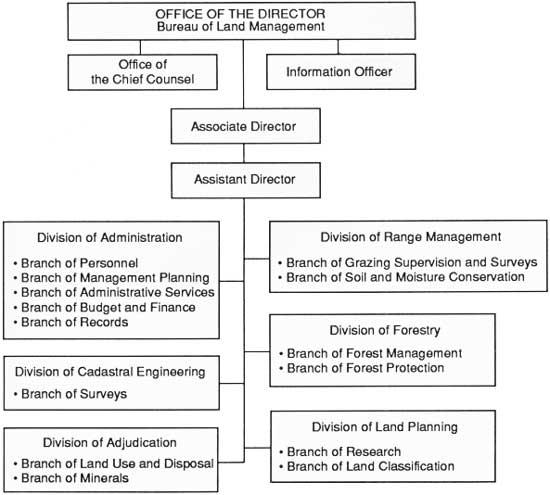

|

Clawson's reorganization made Washington responsible

for overall supervision and development of long-range management and

conservation programs for the public lands. The Director's technical

expertise rested with the Washington office's six branches, which he

transformed into divisions and subdivided into other branches.

Beneath the Washington Office came the regions.

Regional Administrators were directly responsible to the Director. The

regions handled most case adjudications and developed the long-term

plans for the public lands and resources within their jurisdictions.

Regional staffs were organized along lines similar to those of the

Washington Office and provided technical advice to district offices.

|

|

|

|

BLM organizational structure in 1950

|

|

|

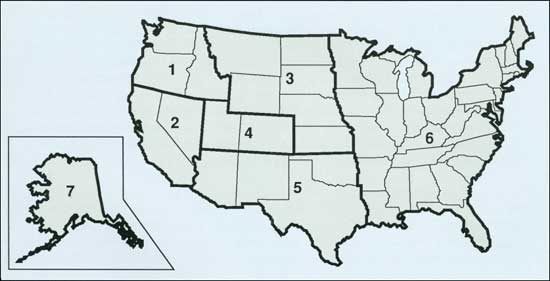

BLM regions in 1950

|

|

A DIRECTOR'S PERSPECTIVE: 1948-1953

by Marion Clawson

Marion Clawson (Jennifer Reese)

|

Editor's Note: Marion Clawson began his career

with the Bureau of Agricultural Economics in 1929 after graduating

from the University of Nevada, Reno, with a degree in agriculture.

He moved to BLM in January 1947 as its first Regional Administrator

in San Francisco. The following statement has been excerpted from a

chapter about Clawson's BLM experience in his latest book, From

Sagebrush to Sage—The Making of a Natural Resource Economist

(Washington, DC, Ana Publications; 1987).

The five years from March 1948 to April 1953 when

I was Director of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) was the most

exciting, rewarding and sometimes frustrating period in my life. We

had many interesting bureaucratic adventures, from surviving drastic

cuts in our budget to obtaining BLM's first supplemental appropriations

for range and forestry programs. My main contributions to the Bureau

were to make its work more efficient and to decentralize its operations

to regional and field offices.

In December 1947, Assistant Secretary Davidson asked

me to come to Washington to discuss my becoming Associate Director of

BLM. I replied that I was unwilling to consider the job, because real

power in the Bureau lay with Tom Havell and this was a case where one

had to be the unquestioned top officer or not take on any responsibility

of top leadership.

I met with Secretary of the Interior Julius Krug and

his Under Secretary for exactly 16 minutes and was offered the position

of Director. After I accepted, Krug said that I would have to bring some

new blood into the Bureau. I agreed, but then added that it was more

important to get some old blood out, and he said, "It can be done."

So that was my charter.

About noon on 4 March 1948, I was sworn in as

Director of BLM. Within a month the House and Senate held budget

hearings. In all my professional life I have never had a more

difficult and strenuous time than the two hours or so I spent before

the appropriations subcommittee in the Senate, when our appropriation

request was under review. I was fighting to get funds restored to

the levels we had asked, to save the regional offices (which I thought

were basic), and to get permission to decentralize. I thought the

latter was extremely important for a number of reasons: decentralization

would put routine decisions nearer the land and the people they

affected, it would put the same routing decisions in the hands of new

people who were anxious to make a good showing, and it simply was

inefficient to have paper constantly flowing from the field to Washington

and back again.

In the end, we emerged as well as could be expected,

given that a struggle was underway between a Congress of one party and

a President of the other. As I recall, we got our requested funds

with a provision that was immensely helpful to me—Washington office

funds were cut and field funds were increased by the same amount. There

was no prohibition against decentralization and our regional offices

survived.

During the years I served as Director, the demand for

nearly all natural resource commodities rose and this had a substantial

impact on the public lands. Range management, soil and moisture conservation,

oil and gas leasing, and O&C forest management were major programs

during my tenure. The number and variety of applications for use of the

public lands or for records about them never ceased to amaze me. For instance,

we experienced a six-fold increase in applications for oil and gas leasing.

Our staff developed a new application form that greatly

speeded the leasing process and prevented clever applicants or agents from

tying up lands by filing slightly conflicting applications (thereby creating

nearly cost-free options to lease the land), I can still recall the glee with

which we and Assistant Secretary Davidson received outraged complaints from

applicants that we had become too efficient and it was costing them money!

Appropriations are the lifeblood of every federal agency.

Policy is as often made and/or implemented in decisions about appropriations

as it is in decisions about substantive legislation. Two incidents produced

breakthroughs in getting adequate funding for BLM.

The spread of a poisonous weed, halogeten, into

various western grazing areas enabled us, with the approval of the

Assistant Secretary, to obtain a supplemental appropriation to reseed

depleted ranges—which was desirable irrespective of halogeten. In

the end, we got something in excess of $2 million supplemental—and

this at a time when our regular appropriation was around $6 million.

With that, BLM launched a large-scale program of reseeding rangelands.

This increase went into our "base" in all the other years I remained at

BLM.

The other breakthrough concerned timber access roads in

the O&C area of Oregon. The GLO and BLM never had appropriations to

build access roads but were dependent upon timber purchasers building roads.

This lack of roads often meant a greatly reduced competition and hence a

much lower price for the timber sold.

One winter an unusually severe storm along the Oregon

coast blew down a great deal of timber. In some of these areas an

infestation of bugs was already killing live trees. These bugs could

thrive even better on blowdown timber and from that base more aggressively

infest stands of live trees. The solution was to harvest both blowdown

and intermingled standing live trees, as rapidly as possible; and for

this access roads were needed. We got a supplemental road-building appropriations

of something between $2 and $3 million; this was the beginning of BLM's

road-building in the O&C area.

In the area of communications, I utilized staff meetings

as a major management tool. I started them early on because I genuinely

wanted our divisions to know what was going on and I was convinced that an

informed Director's staff meeting the last hour of the day on every Wednesday—the

hour chosen so that people who talked too long held everyone to overtime.

A newsletter was then distributed to all employees.

At this time I formulated my second law of administration:

keep them galloping. If one can provide real leadership, develop goals

and likely means of reaching those goals, and generally run both a tight

and an innovative organization, there is much less time for petty gossiping

and dilatory actions. I did my best to keep BLM galloping. As with the

actual running of wild horses, a certain amount of whooping and hollering

was necessary.

|

|

|

Four types of field offices operated beneath the

regional level: district land offices, public survey offices, district

grazing offices, and district forestry offices. Here BLM carried out

most of its management, protection, and disposal activities. A manager

headed each office and was accountable to the regulating Regional

Administrator.

|

|

|

Clawson also gave BLM a sense of mission and purpose

by instituting a "dynamic program for resource management." Key to this

agenda was the concept of multiple use management. "Multiple use,"

according to Clawson, "is [a] system under which the same area of land

is used simultaneously for two or more purposes, often by two or more

different persons or groups." These uses could be complementary, or, as

was most often the case, competitive with one another. Clawson thought

multiple use management desirable and wanted it practiced on

BLM-administered lands.

|

|

Multiple Use

Ethic |

|

Multiple use management offered BLM managers

considerable opportunity and challenge. Land use decisions had to take

into account not only the benefits and impacts of an activity but also

their interactions with other activities. Managers now needed to know

the resource values of the public lands under their jurisdiction. This

required inventory and classification actions, so that the best and

highest priority uses of public lands, along with the most advantageous

land-tenure arrangements to promote them, could be determined.

|

|

|

Clawson emphasized land inventory and classification.

The Taylor Grazing Act directed that lands in grazing districts be

classified before disposal, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt's

general withdrawal orders of 1934 and 1935 directed the same be done

(except in Alaska) for public lands outside the grazing districts. The

Grazing Service and General Land Office had inaugurated studies, but

little of the public domain was inventoried and classified. The

classification work generally responded to individual applications for

land disposal, but case-by-case classifications

did not give BLM managers an overall picture of an

area's character and economics. This required more general

classifications of larger areas.

|

|

Land

Inventory and

Classification |

|

|

Acres classified under Taylor Grazing Act authority

|

|

|

The Missouri River Basin Project, an interagency land

inventory effort begun after World War II, helped facilitate the

agency's gathering of resource data. BLM also inaugurated smaller area

studies, usually small drainage basins where BLM had complex land and

resource use problems to resolve. The data gathered was then, as Clawson

noted, integrated into the development of long-term range plans "wherein

all tenure, protection, rehabilitation, development, and use activities

are properly and effectively balanced and implemented...initiated by

BLM, rather than in response to uncoordinated private demands for public

lands and resources."

|

|

|

Carrying out that objective required considerable

coordination. Clawson wanted to address that need through what he called

"area administration" to achieve better and cheaper management of the

public lands. Area administration meant having in a district office all

resource and technical specialists necessary for district managers to

make informed, effective, and efficient land disposal and use

decisions.

|

|

Area

Administration

Concept |

|

Clawson's "area administration" concept, which he

introduced in the summer of 1952 and his emphasis on decentralization,

land inventory and classification, along with other innovations, pushed

BLM toward becoming a viable conservation and multiple resource agency.

By the end of his tenure in 1953, range and timber lands were better

administered, wildlife and recreation resources were given added

attention, and the management of lands and minerals programs was

improved.

|

|

|

|

BLM emblem introduced by Marion Clawson in 1953 illustrated the

agency's development and management program

|

|

|

|

THE RANGE MANAGEMENT DILEMMA

|

|

|

Clawson knew successful implementation of his

conservation policy depended much on what BLM could accomplish on the

public range. The lands needed improvement, and this could only be

accomplished through better supervision and the institution of rangeland

plans and programs. However, these required more employees and

additional funding. Clawson knew that and attacked the problem head

on.

|

|

Range

Staffing

Problems |

|

The limited number of range management personnel

threatened to forestal any attempts at improving the program.

Nicholson's 1947 grazing proposal had stated that at least 242 personnel

would be needed for BLM to carry out its Taylor Grazing Act

responsibilities. Despite implementation of the 8-cent per AUM fee

increase that Nicholson said was necessary to cover range administration

costs, BLM in 1948 had little more than half the

personnel (123) recommended. The following year the

staff had climbed to 182, but by 1950 the number had dropped to 176.

|

|

|

BLM's grazing monitoring program, trespass

enforcement efforts, and range condition studies were hampered. Clawson

had to correct the situation if any progress was to be made. The 8-cent

an AUM fee was simply not providing sufficient funding and an increase

was obviously needed. He persuaded the National Advisory Board Council

to raise the AUM fee by 4 cents so that he could increase his range

management staff to 250 employees. In 1951, grazing district fees were

raised to 12 cents per AUM, with 2 cents of the fee still going for

construction of range improvements.

|

|

Grazing Fee

Increase |

|

The fee increase allowed BLM to hire new employees,

many of whom had college degrees in range management, and enabled the

Bureau to intensify its range management and supervision efforts.

Detection of grazing trespasses increased. Range resource inventories

and surveys of dependent ranch properties were begun in all regions to

facilitate adjudication of range use privileges. All of this helped

BLM's efforts to stop deterioration of the public range.

|

|

Range

Program

Advanced |

|

Range inventory work was particularly important.

Knowing the condition of public rangelands, BLM could take steps to

prevent further range deterioration. District managers could reduce the

number of livestock grazed, although stockraisers opposed these

reductions and usually succeeded in stopping the grazing cuts. Range

improvement and rehabilitation plans could be implemented. Fencing and

water source development permitted livestock to be distributed in a

manner that prevented overgrazing, while reseeding gave new life to

depleted range.

|

|

|

BLM financed the construction of range improvements

with the 2 cents received from the AUM fee assessed ranchers and from

appropriations under the National Soil Conservation Act for soil erosion

control projects. Ranchers and grazing advisory boards also contributed

money, materials, and labor. BLM, however, could still do little more

than maintain existing projects. Director Clawson in his 1951 report

Rebuilding the Federal Range asked Congress for more funds, noting

that more than 38,000 stock-watering improvements and 68,000 miles of

fence, along with other items, needed to be constructed. However,

Congress made no effort to provide the additional funding Clawson

wanted.

|

|

Range

Improvement

Needs |

|

Congress responded more favorably to BLM efforts to

rehabilitate the range. The Director in his 1951 report on public range

conditions noted that 22 million acres of public land needed

revegetation. He was again unable to get direct funding for this effort,

but he was indirectly successful by getting Congress to enact the

Halogeton Control Act of 1952.

|

|

|

Halogeton is a weed poisonous to livestock that

establishes itself on range in poor condition. The weed, however, can be

controlled through maintenance and redevelopment of healthy ranges. The

Halogeton Control Act sought to arrest Halogeton's rapid spread across

the West and, consequently, provided BLM with badly needed range

restoration funds.

|

|

Range

Depletion and

the Halogeton

Problem |

|

THE RANGE ADVISORY BOARD SYSTEM

A. D. Brownfield, Chairman, National Advisory Board Council

From Our Public Lands, October 1951

The range advisory boards of the Bureau of Land

Management have proven in 15 or 16 years operation valuable adjuncts

in the administration of the Taylor Grazing Act. The system was inaugurated

by the first Director of Grazing with success...so much so, that Congress

soon took notice of the good results, and by amendment to the act, made

the provision for advisory boards permanent.

The Plan for selecting these advisors is in

keeping with our traditional American way of choosing Government

representatives—that is, by election—and thus had support

from the beginning. At the outset, and in compliance with the law,

in order to determine who would be allowed to vote, districts were

set up in each State, and each livestock producer therein was allowed

a vote for the advisors of his own districts.

Instituting the system by popular election allayed

suspicion and facilitated cooperation by those users of the public

range (or public domain) who had never known regulation, or considered

any law necessary for their protection and guidance in the proper use

of their fee lands and leased lands. It brought into the various local

offices for assistance to the Secretary representative men from "the

wide open spaces" better qualified to advise and recommend on proper

division and use of the range, and furnish information on its past use

by contending applicants, and the approximate carrying capacities of

the range. It would have taken years of research and untold quantities

of taxpayers' money to have gathered the information that was quickly

furnished by these professionals of the range. Very little dissatisfaction

has ever been registered against the system, proof of which lies in the

fact that in all of the 10 Western States in which there are grazing

districts, citizens of no one of these States have petitioned for a change

to something different.

The method of administrative procedure was extremely

simple and applicable to range use. All the range was first rated as

to proper number of stock to be grazed, and seasons of use. Each applicant

for a permit was required to furnish accurate information as to his owned

or controlled land and water; he also had to state the numbers and class

of livestock grazed on the public domain prior to the passage of the Taylor

Act. Where reductions in numbers were found necessary to protect the range

such reductions were on a prorated basis in community allotments. In

individual allotments, reduction was made to fit the carrying capacity.

In the absence of basic data on range surveys, classification,

topography, etc., these advisory board members furnished timely information

until such work cold be started and completed (Much of which has not as yet

been finished). Moreover, they serve as popular unpaid policemen for

regulating grazing, trespassing, and other abuses. They also give

information on necessary range improvement facilities—such as

fences, wells, dams, reservoirs, stock trails, driveways, cooperative

plans with State agencies, land exchanges, soil and moisture expenditures,

and many other programs.

Decentralized government has made and kept America

strong. There is no substitute for it. The same has proven true for

good land management. Personal contact with the users of the range

through the advisory board system has made "home rule" on the range work.

|

|

|

FORESTRY PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT

|

|

|

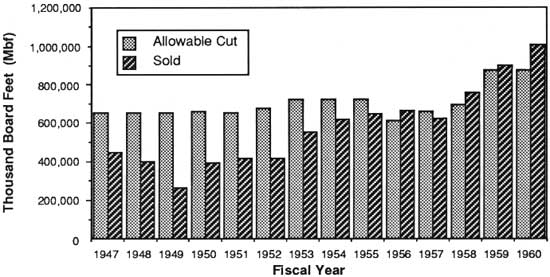

The Bureau's forestry program went through

significant changes during the Clawson years. BLM introduced a new sales

policy for the revested Oregon and California land grant lands in western

Oregon that increased competition and laid the foundation for better

management. It also inaugurated the management of public domain

timberlands.

BLM found management of the O&C revested lands in

western Oregon particularly challenging. When Marion Clawson became

Director, the regional administrator in Portland, Walter Horning, who

was formerly Chief of the General Land Office's O&C Administration,

remained committed to a policy of achieving sustained-yield management

for both O&C forests and private timberlands through cooperative

agreements. The plan allowed private landowners to purchase stumpage

rights to the intermixed O&C forest lands at appraised value and

under 100-year cooperative agreements if they consented to follow

sustained yield requirements developed by BLM.

|

|

|

The 100-year cooperative agreements plan, however,

brought strong criticism. Many interests, particularly timber operators

who did not own lands within the O&C area, felt the plan would give

cooperators a monopoly. Revenues from O&C timber sales would

decline, it was argued, and landowners would have no incentive to permit

multiple use or implement good forestry practices. The protest, led by

the Association of O&C counties, forced BLM to abandon Horning's

plan in 1948.

|

|

O&C Policy

Problems |

|

Director Clawson, as part of his 1948 reorganization

effort, replaced Walter Horning with Dan Goldy. Goldy was an economist

who had worked in the Interior Department on O&C matters. He felt

that the timber operators within the O&C area had the monopoly.

Goldy, fervently believing in competition and equal opportunity,

developed a timber policy that would end the monopolistic and poor

timber practices encouraged on adjoining private lands.

|

|

|

First, potential buyers had to be assured of access

to BLM's O&C tracts. Most access roads within the area were privately built and controlled.

The Bureau instituted a policy requiring the builders to

give BLM and its timber purchasers reciprocal use of

rights-of-way across adjacent private lands.

BLM also sought to end its dependence on private

access roads through construction of its own road system. This would not

only give O&C timber purchasers access rights, but would also lead

to better timber conservation practices because BLM could then build

into areas of overripe or damaged timber in need of harvesting. The

Bureau began building its road system in 1950. The following year, when

extensive fires and wind storms damaged and downed more than 700 million

board feet of timber, Director Clawson was able to get additional

appropriations from Congress to build more roads into the affected

areas.

|

|

New O&C

Policies |

|

Policy further called for timber companies to submit

suggestions as to what lands should be offered for sale during the

following year. In consultation with the district O&C advisory boards, BLM then

developed a sales plan based on these suggestions and informed

prospective buyers months before auction.

The first competitive sales under the new policy came in 1950. The

volume of sales jumped from 265 million board feet to nearly 396

million. During the following year, the volume sold remained the same as

in 1950, but the price bid went from $4.8 million to $8.7 million.

|

|

|

|

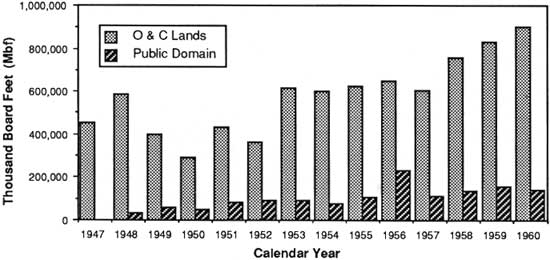

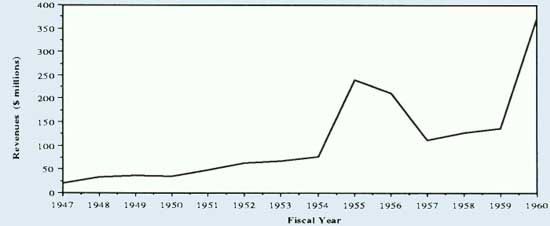

O&C timber sales 1947-1960

|

|

|

O&C timber sale values

|

|

|

Other changes instituted during Clawson's tenure

further enhanced BLM administration of O&C lands. The forestry staff

in Oregon gave new emphasis to timber inventories. Inventories were

essential to determine the amount of timber that could be cut. BLM began

new inventories that not only calculated the volume of available timber

but provided information on the age, quality, size, and the location of

stands from roads and processors. The new data was used to develop

management plans and helped BLM better determine how much timber could

be sold each year on a sustained yield basis.

|

|

|

The most significant change, however, involved the

O&C advisory boards. In 1948, the Department of the Interior and BLM

reorganized the boards to promote broader public representation. Members

now represented not only the timber industry, State of Oregon, and

counties, but also labor, mining, agriculture, recreation, wildlife, and

conservation groups. This action more closely reflected the multiple use

character of O&C lands and gave BLM a broader management

perspective.

|

|

O&C

Advisory

Boards |

|

BLM also developed a forest policy for public lands

outside the O&C area. There were an estimated 3 million acres of

commercial forest lands and 25 million acres of woodland, exclusive of

Alaska, on public lands. Prior to 1947, BLM had no authority to manage

these lands. It could only dispose of the lands or remove dead-and-down

timber to reduce fire danger. The Materials Act of 1947 changed this,

permitting BLM to sell timber from public lands.

|

|

|

BLM recognized public domain timber would not equal

the volume or value of O&C timber, but because many of the stands

were important to local economies, they too needed management. BLM,

however, did not have foresters to oversee or administer these lands

until 1949, when an increase in funding allowed BLM to place foresters

in each regional office and a few grazing districts. Inventories

subsequently began and sustained yield cutting plans were developed.

|

|

Public

Domain

Timber

Resources |

|

BLM also pushed forestry efforts in Alaska. The

Territory had 125 million acres of public timberland. Stumpage from

Alaska's public lands could be sold through the Act of

May 14, 1898. The General Land Office's local land officers had handled timber

sales until the responsibility was transferred in 1946 to the Alaskan

Fire Control Service (AFCS). With the creation of the Bureau of Land

Management, the AFCS became Alaska's Division of Forestry. Like the

AFCS, it provided fire protection, controlled forest use, supervised

timber sales, set up sustained yield forestry units, and encouraged new

wood-using industries. The new Division, however, put more emphasis on

timber inventory work.

|

|

Forestry in

Alaska |

|

FIRE SUPPRESSION

|

|

|

Fire prevention and suppression was an integral part of BLM's timber and

range management programs. When Clawson became Director, the Bureau's

fire program had changed little from that of the General Land Office and

the Grazing Service.

|

|

|

Fire suppression efforts under the GLO and Grazing Service largely

depended on cooperative agreements with federal and state

agencies and local protection organizations. Insufficient funds

forced BLM to continue this practice on the nearly 6 million acres of forest

land in California, Idaho, Montana, Minnesota, Arkansas, Washington, and Oregon.

|

|

Fire

Protection

Contracted |

|

In other areas, BLM used its grazing and forestry district personnel

to develop a fire suppression organization. District fire

crews were established and could be supplemented, during large fires, with

personnel from other districts.

|

|

BLM Fire

Program |

|

To assist district crews, BLM in 1951 began

purchasing 4-wheel-drive high-pressure pumper trucks. The vehicles,

though few in number, quickly proved their value as two-person crews

showed the pumpers' effectiveness in suppressing range fires. That same

year, BLM also began installing high-frequency radio networks in an

effort to decrease response time to fires and more effectively

coordinate firefighting efforts.

|

|

|

In Alaska, the Bureau did what it could to maintain

the small, but well organized Alaskan Fire Control Service it had

inherited from the General Land Office. Firefighters in Alaska found

themselves confronted with an increasing fire problem as settlement,

tourism, and military activity increased after World War II. Fire

control efforts, although hampered by Alaska's immense size and lack of

access were aided by cooperative agreements with other federal

departments and agencies. The U.S. Weather Bureau supplied forecasts and

relayed emergencies, while military and Civil Aeronautics Authority

aircraft aided in fire detection and the transportation of crews and

equipment.

|

|

Fire

Protection in

Alaska |

|

WILDLIFE

|

|

|

The fire program's primary purpose was to protect

forest and rangelands from damage and waste, but the program also

benefited wildlife habitat. And the Taylor Grazing Act addressed the

importance of wildlife on the public lands by opening grazing districts

to hunting and fishing and allowing the Secretary of the Interior to

work with state wildlife agencies in managing wildlife habitat.

|

|

|

The Grazing Service took wildlife habitat into

consideration and permitted wildlife interests to play an active role in

administering the grazing districts in New Mexico and Oregon. New Mexico

stockraisers included one wildlife representative on their advisory

boards. By 1939, all district boards had wildlife representatives. The

Grazing Service also worked closely with state and federal wildlife

officials and hunting and fishing groups.

|

|

Grazing

Service Policy |

|

BLM continued the Grazing Service policy toward

wildlife. Wildlife habitat management was an important part of BLM's

range program. District managers worked closely with their advisory

board's wildlife representative and state officials in managing wildlife

on public lands. Some states helped the Bureau in rangeland reseeding

efforts, which increased forage for wildlife as well as for

livestock.

|

|

Early BLM

Policy |

|

RECREATION

|

|

|

Recreation was another important resource on public lands. The

Recreation Act of 1926 provided for the transfer and lease of

recreational lands to state, territorial, and local governments if they

were not needed by the federal government.

|

|

Recreation

Act of 1926 |

|

TALES OF EARLY BLM FORESTRY IN ALASKA

by Edwin Zaidlicz

Former Montana State Director

It was the bitterly cold winter of 1949 when I joined

BLM by replacing the first professional forester in the northern half of

Alaska at Fairbanks. The forestry program was truly embryonic and our

first responsibility had to do with containing tundra fires and as need

and time warranted, we processed fire wood permits.

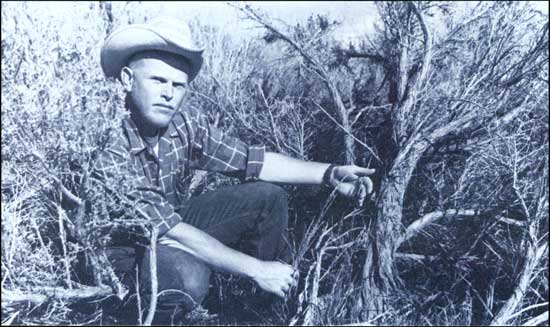

Edwin "Moose" Zaidlicz in 1951. (Edwin Zaidlicz)

The Homestead Act was alive and well with our

management authority and objective based on the land laws that

encouraged land disposal. For a forester trained under the principle of

long-term forest management under sustained uniform yield, a

philosophical stress quickly developed. BLM appeared unready to accept

long-term management of public land for any purpose.

I soon found myself at odds with the man in the fine

office across the street—the Fairbanks Land Office manager. Until

I, as the "cheechako stump jumper" arrived, his role as a "Fed" was

time-honored and respected.

Then, during the next spring, Bob Robinson, our head

forester in Anchorage, budgeted enough to hire three more foresters for

Fairbanks.

Our "strange breed of cats" group had few

regulations, no manuals other than those for fire and fiscal management

and almost no direct supervision. Communications with Anchorage involved

very slow mail, emergency air flights or our "Mukluk telegraph," a

system of in-house war surplus radios.

Quickly we learned to use our own discretion rather

than risk an undesirable and tardy decision from the south. We enjoyed a

commonality of purpose, unlimited energy and enthusiasm, and an

unavoidable need for creativity and innovation. State-of-the-art

technical props included the radio, a Cessna 180 plane on floats or

skis, a Polaroid Land camera and a handful of college textbooks.

Undaunted, we "came out of the chute" by initiating

1) The first timber inventory of interior Alaska by

sampling stands along the Yukon, Porcupine, Tanana and Chena rivers.

Even then I squirmed at our audacity and possible sampling error. The

Cessna and an outboard river boat served for transportation. Our aerial

photography consisted of shots with hand-held cameras;

2) A small tree nursery and a post-treatment

experiment. Dr. Harold Lutz, a forest soils authority from Yale and Dr.

Ray Taylor, Chief of the USFS Alaskan Research station visited us. We

proudly demonstrated our Rube Goldberg watering system. Dr.

Taylor, a gentle and kindly man, expressed guarded admiration for our

initiative and novel operation. Dr. Lutz, a crusty pragmatist, made

a more objective observation— "Your Herculean efforts will perhaps

retard the cause of scientific forestry 100 years;"

3) Having the full support of the Air Force and the

use of their vast depot of heavy equipment to take charge of any

threatening tundra fires, we did some dramatic improvisation. We

dispersed eight D8 caterpillar tractors in two units under a "USFS one

lick fire line approach." A serious fire was quickly controlled. We were

then visited by Mr. Gustafson, Fire Chief of USFS in D.C. and Mr.

Blackerby of the USFS Regional Office to study our "perma-frost fire

control." Gustafson, clearly impressed, observed that our "fire trails

could unquestionably be seen from the moon;"

4) In an effort to improve the stagnant economy of

our District, we got involved with a troubled Swedish homesteader to

gather and process birch tree sap—much as is done on maple trees.

While the syrup proved quite tasty, our new industry never displaced

firewood cutting or muskrat trapping;

5) During the winter of '50-'51, Bob Robinson

initiated the first formal timber inventory to undergird a possible

timber operation in Alaska's southern district on Windy Bay. Three

foresters from Anchorage and I were flown into the tract by a WWII

"Goose" piloted by Bob McCormick. We had a large double canvas tent, our

personal gear, grub for 30 days and explicit instructions from Bob R.

For emergency use we had a special surplus-parts radio. About the time

McCormick waggled his wings in his departing flyover, we confirmed the

radio didn't work.

After 5 weeks, we completed our field sampling and

were returned to civilization. Living in continual snowstorms and

howling winds with three unwashed companions in a tent that served for

cooking and living was an unforgettable experience and gave me a new

meaning for the term "cabin fever." I did learn that it is possible to

respect and admire another sharing the same traumatic circumstance. It

was there that I made a life-long friend of the legendary Jim Scott.

Perhaps the highlight of my forestry career in Alaska

occurred in the fall of 1951 when I almost succeeded in putting my

admirer, the Fairbanks Land Office Manager, in jail for a fire and game

violation. The word of this "forestry action" quickly spread throughout

Alaska and BLM. The manager was arraigned, fined and lost his game

license. Shortly thereafter, he was actually promoted to a more

desirable post in the States and I got the opportunity to transfer to

the O & C in Roseburg, Oregon.

My vivid recollection of those adventurous days of

early Alaskan forestry highlight impressions of vast untapped resources,

immense distances, unparalleled natural beauty and the troubling

insignificance of man's puny efforts to impact or manage any of the

resources, especially timber and wildlife. Even our natural disasters

were brutally intimidating; our 1951 Porcupine River fire burned 2

million acres in what seemed like a couple of days. To simply map the

burn area took 5 hours of flight in a Cessna 180. We had to carry

5-gallon tins of fuel to gas up on shallow duck lakes.

Clearly the quality of humility in a neophyte

forester is desirable and Mother Nature provides

a dramatic setting in Alaska for developing it.

|

|

|

BLM's lack of legislative authority to provide recreational

opportunities did not dampen the agency's interest or

efforts in recreation. Some BLM resource programs benefited recreationists

indirectly—such as wildlife habitat management and access road

construction. The Bureau's land classification program identified many potential

sites for acquisition under the Recreation Act of 1926. In some areas,

district personnel built

facilities, such as camp and picnic grounds, even though they did not

have the authority to do so.

|

|

Lack of

General

Recreation

Development

Authority |

|

The increasing public demand for recreational opportunities after

World War II was furthered by the Small Tract Act of 1938. This law,

as amended, provided for the sale or lease of tracts not

exceeding 5 acres that were determined to be chiefly valuable for recreational,

residential, business, or community site purposes. In 1949 there were nearly

7,500 Small Tract Act leases. Clawson commented that the Small Tract Act had

become the law preferred by those seeking a home on the public domain.

He was right. By 1952 the number of Small Tract Act leases had climbed

to more than 25,000, and nearly 300 parcels had been sold for

patent.

|

|

Small Tract

Act |

|

LAND HUNGER IN THE EARLY 1950s

|

|

|

The Small Tract Act was indicative of public land

activity after World War II. Homestead, Desert Land, and other types of

entries increased sharply. Interest was particularly high among

veterans, who received preference in making entries, but BLM had to deny

many of the applications because the lands entered were not suited to

agricultural development. As Director Clawson stressed, public land

policy since the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 looked to "the management

and protection—and selective, rather than summary disposal—of

the approximately 778 million acres of public domain and their resources

in [the] continental United States and Alaska." Statements such as this

did not dissuade potential settlers; the lure of the public lands was

too strong.

|

|

Post-World

War II Boom |

|

Alaska experienced much of the boom. Thousands of

military and civilian personnel sent to Alaska during World War II saw

first-hand the opportunities Alaska had to offer, and many stayed to

take advantage of the situation. Hundreds of others came after the war

by way of the Alaska Highway, drawn by stories of the Territory's

riches.

|

|

Alaska: Land

of Promise |

|

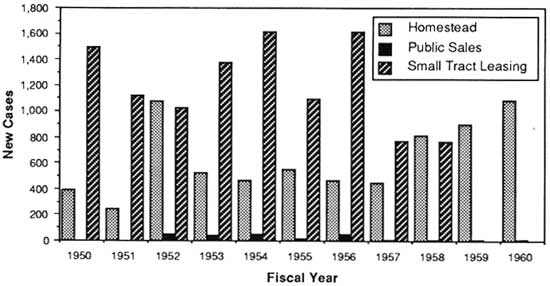

Many who came to Alaska used the Homestead Law to

acquire land; from 1946 to 1953 more than 3,300 such entries were made.

Competing with the Homestead Law was the Small Tract Act. Extended to

the Territory in 1945, Small Tract Act sites were used to acquire lands

for homesites, weekend cabins, and businesses around Anchorage and

Fairbanks. By 1953, 600 sites had been sold and nearly 2,500 tracts were

under lease.

Settlement and development of Alaska, however, was

retarded by the lack of survey. Surveys were needed to adjudicate

applications for use and disposal of public lands, but at that time only

2.5 million acres, or 1 percent of the Territory, had been surveyed

under the rectangular system. BLM made surveys a high priority, but appropriations

during Clawson's tenure permitted little more than 100,000 acres to be

surveyed.

|

|

|

|

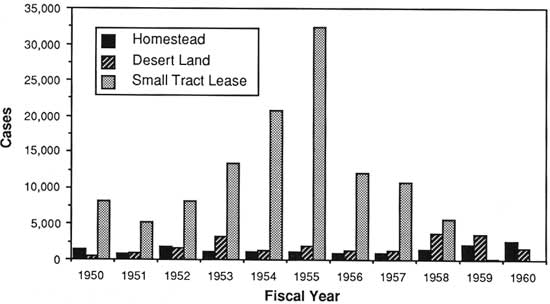

New land case actions in Alaska 1950-1960

|

|

|

Land classification in Alaska was another important

issue. BLM wanted orderly settlement and development for the Territory.

The Bureau, however, had no general land classification mandate in

Alaska, and so, the agency made do with the few authorities it did

have.

Classifications required under the Small Tract Act

were used to identify public lands values and control development around

Anchorage, Fairbanks, and other Alaskan towns. The Alaska Public Sales

Act of 1949 was also used to advantage. This law provided for the

auction of 160-acre parcels of surveyed and unsurveyed lands to

individuals and other interests who met certain criteria. Successful

bidders were required to file a satisfactory plan of development for the

tract and complete their project within 3 years or forfeit both the land

and the money bid. In 1952, the Bureau, in cooperation with the Soil

Conservation Service, launched a program of planned homestead

development by identifying suitable lands and marking out farm units for

prospective settlers.

|

|

|

Land applications were also increasing in the "Lower

48." The Bureau's decentralization of land case adjudication

to the regional offices helped speed processing, but the crush of

applications was overwhelming.

|

|

Lower 48

Lands

Situation |

|

In response to the increasing backlog, BLM wrote new

regulations to streamline the adjudication of cases. The Bureau also

began developing a new land record system. Through a microfilming

process, certain land records, such as patents, could be more easily

used and more effectively preserved. BLM also created a Division of

Lands from its adjudication and land planning divisions in 1951 in an

effort to more effectively administer the lands program.

Director Clawson called for a congressional review of

public land laws. He pointed out, like the General Land Office had

before him, that many of the laws under which the Bureau operated were "to a

large degree outmoded and incoherent" and in need of revision. However, Congress felt that the

policies did not need substantial revision.

|

|

|

MINERALS

|

|

|

Development of federal minerals became increasingly

important after World War II. Truman's Reorganization Plan No. 3 gave the

Secretary of the Interior responsibility for all mineral activity on

federal lands. The Bureau continued General Land Office functions by issuing leases

and administering mining claims on the public lands. It also began overseeing

the leasing of mineral estates acquired by the federal government with the passage

of the Acquired Minerals Leasing Act in 1947.

|

|

Mineral

Leasing

Responsibility |

|

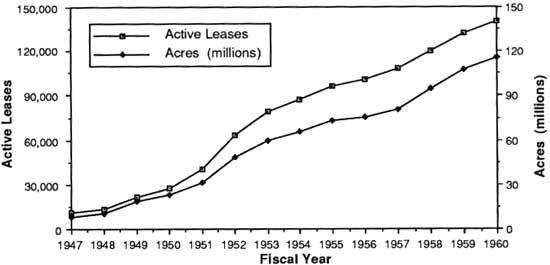

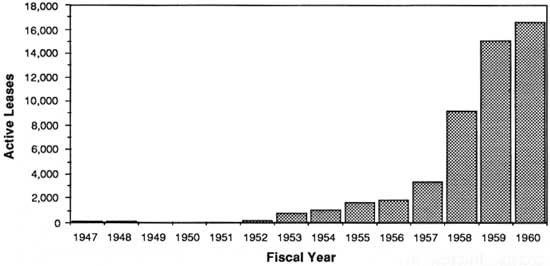

Oil and gas activity best reflected the new surge of

mineral activity on the public lands. Petroleum companies had increased

their lease and exploration for oil and gas during World War II and

continued this activity after 1945. A boom in activity,

however, did not come until 1950. That year

alone saw 16,000 noncompetitive leases

filed compared to the 4,000-a-year average during World War II. In 1951,

BLM created a Division of Minerals at Washington headquarters to better

handle the resulting workload. This action came at the right time. In

that same year, an unprecedented boom in petroleum leasing came with the

discovery of oil in the Williston Basin in North Dakota and Montana. The

resulting "black gold fever" caused the number of new oil and gas lease

applications to jump to nearly 32,000 in fiscal year 1952.

|

|

Oil & Gas

Boom |

|

|

Active Oil & Gas leases for public domain lands 1947-1960

|

|

|

Increased oil and gas leasing created many headaches

for BLM, but the worst was the age-old problem of speculation and fraud.

Through newspaper and magazine advertisements, oil and gas brokers

appealed to the desire of people to get-rich-quick by offering to file

40-acre federal leases for them. "The practice," complained Director

Clawson, "not only swamped land offices with thousands of applications,

but retarded the orderly exploration for oil and gas." The Justice

Department called the practices of the oil and gas brokers unethical but did not have

sufficient evidence of misrepresentation to prosecute the filing firms.

BLM did, however, try to end the problem by revising its regulations to

prohibit the issuance of leases for less than 640 acres in areas outside

producing units.

|

|

Speculation

and Fraud |

|

THE CLAWSON LEGACY

|

|

|

By 1953, Marion Clawson had transformed the Bureau of

Land Management into a multiple resource agency. As Director, he had

been able to institute reorganization and policy changes with little

controversy. The Bureau under Clawson also strengthened many programs

through better funding and the hiring of additional people. Clawson

established a firm foundation upon which the Bureau's resource programs

could build and the agency's developing multiple use ethic could grow.

It was a commendable job, but his land management philosophy differed

from that of the new Eisenhower Administration; he was forced to leave

the Bureau of Land Management in 1953.

|

|

Clawson

Accomplishments |

|

THE EISENHOWER ADMINISTRATION AND "PARTNERSHIP IN CONSERVATION"

|

|

|

The Presidential election of 1952 swept Dwight

Eisenhower and the Republican Party into the executive branch after a

20-year hiatus. Republicans were not hesitant in using their victory to

reshape public land policy. They did not intend a wholesale dismantling

of the conservation policies inaugurated by the Democrats, but they did

seek to loosen the restrictions they felt Democratic conservation policy

had placed in the way of private development of public lands and

resources.

|

|

Republicans

Gain the

White House |

|

"Partnership" was the key word of the Eisenhower

Administration's public lands policy. "The best national resources

program for America," stated Eisenhower in his first State of the Union

Address, "will not result from exclusive dependence on federal

bureaucracy. It will involve a partnership of the states and local

communities, private citizens and the federal government, all working

together." Eisenhower selected Douglas McKay, Governor of Oregon, as his

Secretary of the Interior. McKay was more blunt in expressing the new

Administration's public lands policy. After taking his new job, he

declared, "we're here in the saddle as an administration representing

business and industry." To accomplish this, McKay emphasized reduced

bureaucracy, greater states' rights, and a freer hand for private

interests. The new Secretary wanted agency chiefs who adhered to this

philosophy and in McKay's view, Marion Clawson was not such a man.

|

|

New

Conservation

Thrust |

|

Clawson was viewed by the incoming Republicans as an

advocate of central planning by government and as having the opinion

that government could manage resources better than private interests.

This led some Republicans to suspect Clawson of being a socialist.

Clawson had to go; Secretary McKay asked the BLM Director to resign. Clawson refused,

citing his civil service status required a reason for his removal. McKay

found one: insubordination.

|

|

Clawson

Leaves |

|

DIRECTOR EDWARD WOOZLEY: A CHANGE IN DIRECTION

|

|

|

Marion Clawson was replaced in May 1953 by Edward

Woozley. Woozley, the commissioner for state lands in Idaho, supported

the Eisenhower Administration's States' rights platform and pro-business

and industry stance. The Idahoan was also described by supporters as

"capable, imaginative, and resolute." This was a man more to McKay's

liking; however, Woozley did not meet the civil service requirements for

Director and so had to serve as Bureau Administrator for the first year

of his nearly 8-year tenure.

|

|

Director

Edward

Woozley |

|

Among Woozley's first actions was the reorganization

of BLM. He and Secretary McKay felt the Bureau was too centralized, even

after Clawson's restructuring. A committee comprising three Departmental

employees and three members of the public agreed with the assessment.

They concluded that there remained "too great a concentration of

operations in the Washington and regional offices."

|

|

BLM

Reorganized |

|

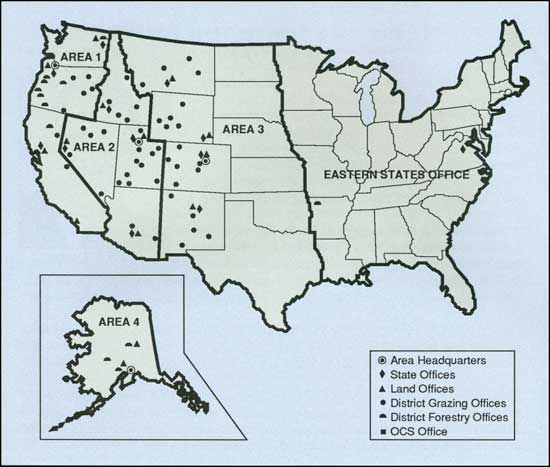

Acting on the committee's recommendations, Washington

headquarters was restricted to providing major policy direction to the

field organization. The regional offices were reorganized into four Area

Offices—not to be confused with Marion Clawson's "area

administration" initiative—with Area Administrators having general

administrative and supervisory responsibility over the activities within

their jurisdictions.

Most of the former regional office responsibilities

went to a new organizational level called State Offices (except Alaska).

These became the highest level of operations and implementation in the

field, taking on adjudicative, land classification, and other land and

resource functions. The State Supervisors in these offices dealt with

state officials within their jurisdiction and developed long-range

resource management and disposal programs. Along with their resource

staffs, the State Supervisors also provided advice and technical

direction to the District Offices.

District Offices continued as the lowest

organizational level. The District Land Offices maintained land status

records and took applications for public lands and minerals. District

Grazing and Forestry Offices handled applications for range use and

timber cutting as well as other actions.

Woozley, like Clawson before him, felt this

decentralization of responsibilities and functions would bring public

land management and decisionmaking closer to the user level, thus

increasing efficiency and lowering administrative costs. The

reorganization was implemented in 1954, and BLM's structure changed very

little during the remainder of Woozley's tenure.

|

|

|

Woozley saw BLM as a business manager and felt that

"the full worth of the valuable resources on the public lands may

be realized with a minimum expense to the taxpayer and that through

careful cooperation with private enterprise, these lands can produce the

products on which local, state, and national economy depend." This

outlook would characterize the Woozley years.

|

|

BLM is a

Business |

|

|

BLM reorganization of 1954

|

|

|

RANGE MANAGEMENT ISSUES

|

|

|

When Woozley became Administrator, the range

management program again became a center of controversy. The Republican

Party Platform for the 1952 Presidential election had called for

legislation that would better define the rights of public land users and

protect those rights against administrative interference. In line with

that pronouncement, Republican Congressman Wesley D'Ewart introduced

legislation aimed at making the privilege of grazing on public lands a

legal right by guaranteeing grazing use and providing for judicial

review of administrative decisions.

|

|

New

Range Use

Controversies |

|

Conservationists immediately attacked the D'Ewart

bill. Montana Senator James Murray called it "another monumental

giveaway" measure. The Department of the Interior could not even support

the bill, and the legislation, as well as an amended version in 1954,

was defeated.

|

|

|

A DIRECTOR'S PERSPECTIVE:

1953-1961

by Edward Woozley

Edward Woozley (Jennifer Reese)

|

Editor's Note: Edward Woozley came to BLM with

the Eisenhower Administration in 1953 and helped shape

Secretary of the Interior Douglas McKay's "Partnership in Conservation"

policy. Woozley was suited to the challenge. He had been Idaho Land

Commissioner and appraised land for the Idaho State Land Board and the

Production Credit Corporation. In July 1960, Director Woozley wrote of

the BLM's accomplishments in the years since his appointment.

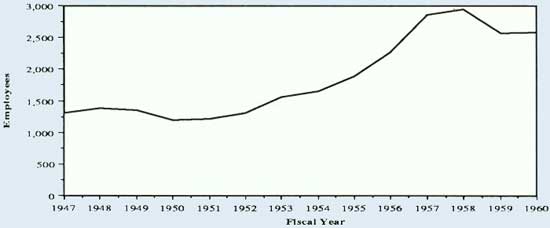

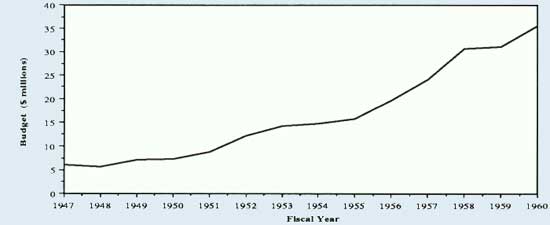

We in the Bureau have been giving much thought to the future in

recent months. Our look ahead certainly told us that there still remains

much to be done in managing the Nation's resources. But the enormity of

the job ahead shouldn't cause us to lose sight of some of the

achievements we have made in the past. The last seven

years have been impressive.

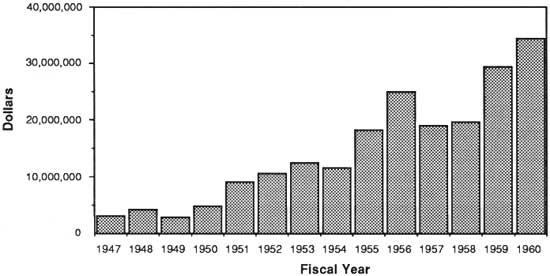

For FY 1953 Congress appropriated slightly more than

$14 million. For the year just ending the figure will be closer to $34

million, and the figure will probably be higher next year, if the

various receipts from which we get a share, come up to expectations.

Receipts too, give an idea of the growth that has

been made. In 1953, the cumulative total of receipts by BLM and its

predecessors over some 140 years reached the landmark figure of $1

billion. In the last seven years, that figure has been reached for the

second time. In FY 1960 alone our receipts will be approximately $375

million.

Of course our growth cannot be measured in terms of

money alone. In 1953, a new record was set when 626 million board feet

of timber was cut on O & C lands. For this past year the cut will be

approximately a billion board feet. In 1953, we closed about 60,000

cases in our lands and minerals adjudication processes. When the final

figures are totaled for 1960, the number of cases closed will be close

to 220,000. Our classification and investigation program in the same

period will show a gain of 35 percent over the 23,306 cases closed in

1953. In our cadastral survey program the total number of acres surveyed

each year is now approaching 2,000,000, an increase of about 16 percent

over 1953. But the big jump comes in original surveys, where our present

program calls for surveying more than twice the acreage surveyed in

1953.

Statistics tell only part of our story. The Bureau,

for example, has supported and helped prepare innumerable pieces of

legislation advancing the cause of conservation and resource management.

The 1954 amendment to the Recreation and Public Purposes Act has

provided a tool of increasing importance to the Bureau in meeting the

Nation's increasing demand for resources devoted to recreation and

leisure time activity. The Outer Continental Shelf Act, passed in August

1953, already has returned to the U. S. Treasury more than $434 million,

with an additional $300 million held in escrow pending final

determination of its distribution by the Supreme Court.

Another major legislative milestone was the passage

in 1955 of Public Law 167, the most important piece of minerals legislation since the

1920 Mineral Leasing Act. Multiple use of surface resources, and the

elimination of many serious conflicts between surface management and

mining operations, became achievable realities as a result of the Bureau

program developed under this law.

While legislation is behind some of the changes in

the Bureau's activity, major importance must be attached to those

non-legislative changes which also have been instituted. The concept of

a unified and coordinated program of resource management based on state

boundaries, was a major purpose of our 1954 reorganization and the

increased effectiveness of operations within the various states has

proven the value of that move.

Long range conservation programs tell a significant

story of Bureau progress. The Bureau's reforestation program is a case

in point. A comprehensive inventory in 1957 showed that more than

150,000 acres of western Oregon forest lands needed artificial

reforesting. In that year the Bureau began a greatly accelerated forest

land rehabilitation program and to date 75,000 acres have been planted.

This program will place cutover and burned lands in production 5 to 20

years sooner than nature's normal processes.

Great strides have been made also in a variety of

management activities. The deterioration of the public lands records

through age and use threatened to make these vital records useless to

future generations. Early recognition of this problem and the

development of our long range records improvement project has enabled us

to take an enormous step forward, in not only preserving them but

putting them in a form that adds greatly to the clarity and ease of

use.

Surveys of our land offices, our forestry programs,

and the operation of our grazing districts have led to significant

changes in the organization and management of our activities, thereby

increasing their efficiency, and enhancing their ability to serve the

public.

Speeded operations through automation have become

increasingly significant in recent years. We now acquire forest

inventory data through automatic data processing in Oregon; bills are

automatically prepared from punched paper tape in Cheyenne; a robot

typing machine prepares answers to correspondence in Los Angeles; and

photocopy and other reproducing equipment enables us to prepare almost

instantaneously, copies of records and maps, from originals or from

microfilm.

Field techniques likewise have benefited from the

adoption of new tools and equipment. The Bureau pioneered the program of

fighting major fires in Alaska through airborne borate drops. Our

engineering survey parties have achieved outstanding results through the

use of helicopters, photogrammetry, and tellurometric equipment, the

first truly major changes in surveying techniques in more than a

century.

In all, these have been eventful years. Progress

hasn't always been as fast as we would like, but when we look back to

where we have been, it is clear that we have made great strides. The

road ahead looks more promising today than ever before. When we recall

the idea that "What's past is prologue," it can be said that the future

looks very bright.

|

|

|

Woozley was sensitive to the debate on Capitol Hill

and wanted to cool the controversy. Some ranchers complained that nearly

half of them operated on public lands with only year-to-year leases;

they wanted more secure tenures. Woozley addressed the problem by

declaring it the Bureau's policy to give more than 90 percent of its

range users 10-year grazing leases as fast as the necessary reappraisals

of user leases would permit.

|

|

|

Woozley, therefore, made range adjudication the range

management program's highest priority. BLM's range staff stepped up work

on range condition inventories and the surveying of private ranch

properties to determine carrying capacities and grazing use privileges.

The work was slow because of the limited staff, but the Bureau moved

ahead and made great strides in adjudicating range privileges.

|

|

Range

Adjudication

Efforts |

|

|

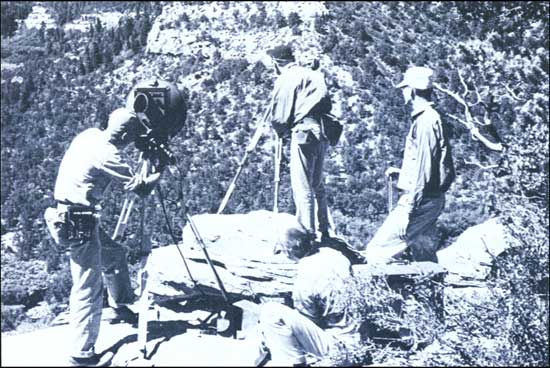

Range inventory work near Dillon, Montana

|

|

|

The reappraisals led to controversy. BLM grazing

district managers, with "hard and cold facts" in hand, often reduced

range use to levels more compatible with the new carrying capacity

determinations. Stockraisers did not like the cuts and resisted BLM's