OPPORTUNITY AND CHALLENGE

The Story of BLM

|

|

|

A MULTIPLE USE MANDATE:

The 1960s

Transition from custodianship to action programs is part of the

new dimension by which BLM is putting the public lands to work in

the public interest.

—Stewart Udall

The Third Wave, 1966

|

A MULTIPLE USE MANDATE

The 1960s

|

|

|

The 1960s brought rapid growth and fundamental change

to BLM—tumultuous change that permanently altered the Bureau's

course. President Kennedy took notice of the public lands, saying they

were vital to the nation's economic well-being but

suffered from "uncontrolled use and a lack of proper management." The

White House asked BLM to accelerate its inventory of the public lands

and develop a program of balanced use to reconcile resource

conflicts.

|

|

Overview |

|

A fledgling multiple use philosophy within the Bureau

was legally endorsed for the public lands in the Classification and

Multiple Use Act (CMU Act) of 1964. BLM was reorganized to reflect new

programs and authorities under this mandate: concerns for wildlife,

recreation, soil, and water resources were integrated into traditional

programs (range, forestry, lands, and minerals) through a land use

planning process.

|

|

|

Inspired by the conservation accomplishments of

Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt, Secretary Udall launched the

nation's "Third Conservation Wave" by requesting a

new legislative mandate for the public lands from Congress. Part of this

agenda included formal recognition of

multiple use management on BLM lands,

patterned after the Forest Service's Multiple Use Sustained Yield Act of

1960. Other components centered on getting BLM a more flexible land sale

authority and repealing outdated settlement acts.

|

|

The Third

Conservation

Wave |

|

But more than a push for legislation, the Third

Conservation Wave was a philosophy—one that viewed natural

resources as finite, interrelated, and vulnerable components of larger

systems. According to Udall, the Interior Department had "the prime

function of planning for the future of America and working to conserve

the natural resources which sustain its life." The Department's 1961

Annual Report spoke of a "quiet crisis" facing America's citizens, the

result of unplanned progress and explosive growth—something that

threatened the nation's natural resources and its citizens' quality of

life. Careful management of America's public lands could turn the tide,

and this could only be done with extensive planning and involvement from

the public.

Udall's program was only part of a growing national

conservation movement. With more leisure time on their hands, urban

Americans began to take notice of the public lands. Recreation groups

and conservation organizations gained many new members in the 1960s and

began to petition Congress for new parks, wilderness areas, and outdoor

recreation facilities. While BLM was not as well known by the general

public as were the National Park Service and the Forest Service (as

evidenced by the omission of BLM lands from the Wilderness Act of 1964),

the Bureau saw its local and regional constituents grow.

Citizen lobbies soon began to voice concern on

protecting endangered wildlife and combating pollution. By the end of

the decade, overall environmental quality emerged as a national issue.

The Third Conservation Wave grew into a demand for action from Congress,

the Interior Department, and BLM. According to natural resources

professor Sally K. Fairfax, "resource issues have never been discussed

with such emotional intensity as they were in the late 1960s and early

1970s."

|

|

|

Three Directors oversaw BLM's growth into a multiple

use agency during the 1960s: Karl S. Landstrom (February 1961 - June

1963), Charles H. Stoddard (June 1963 - June 1966) and Boyd L. Rasmussen

(June 1966 - June 1971). Landstrom supervised the drafting of

Secretary Udall's legislative agenda and worked to reduce the Bureau's

growing backlog of pending land applications. Stoddard began to

implement the new legislation and reorganized the Bureau to more

effectively manage its workload. To integrate all this activity on the

ground, Stoddard started the development of a multiple use planning

system on the public lands.

|

|

New

Leadership |

|

Boyd Rasmussen completed these tasks and introduced

initiatives of his own. Land use classifications under the CMU Act were

completed and a planning system was implemented in the field. Rasmussen

worked to "depoliticize" BLM's decisionmaking process, giving the

Department and Congress the task of deciding sensitive political issues,

such as grazing fee formulas. In addition, Rasmussen directed BLM's

early efforts toward obtaining a comprehensive management statute for

the public lands—a goal eventually attained through passage of the

Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976.

|

|

|

Reflecting their increasing visibility, 167 million

acres of BLM lands in the 11 western states were renamed the National

Land Reserve, and after implementation of the CMU Act, National Resource

Lands. At the end of the decade, BLM and Congress began to recognize

unique values on the public lands and designate special management

areas—natural areas, recreation lands, primitive areas, and

national conservation areas—to protect areas identified in the

classification process.

|

|

The National

Land Reserve |

|

In 1963 Secretary Udall designated Resource

Conservation Areas on BLM lands in each of the western states to

demonstrate how active management of the public lands would provide

benefits to all resources, including soil and water, forage (both

wildlife and livestock), and forests. Director Stoddard said "we hope to

acquaint every American with the thought that he is part owner of a

great national treasure—which is becoming ever more valuable as our

population grows." Secretary Udall urged conservationists to visit these

areas and follow their progress through on-the-ground inspections and

discussions at club meetings.

|

|

Resource Conservation

Areas |

|

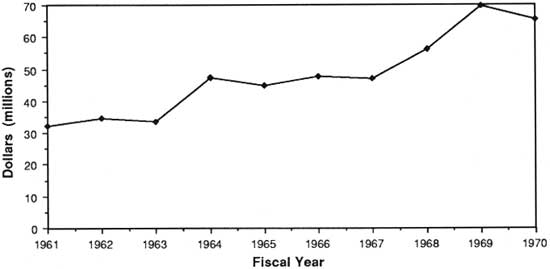

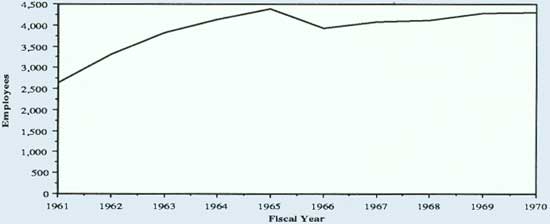

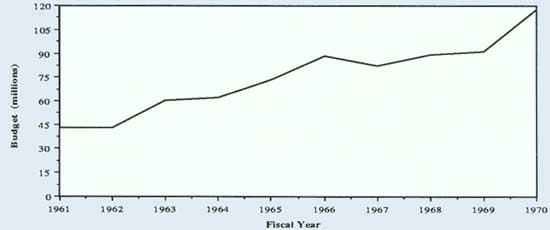

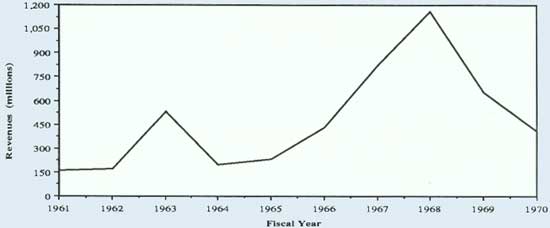

This explosion of activity in the 1960s led to a new

land ethic, but it was not achieved without cost: controversies erupted

and debates intensified as BLM advanced its multiple use mission.

Reflecting America's growing concern for its public lands (and the

Bureau's new mandates), BLM's workforce grew from about 2,600 in 1960 to

4,300 in 1970, with its budget growing from $36 million to $118 million.

Revenues also grew—to over a billion dollars in 1969—thanks in large measure

to increasing Outer Continental Shelf revenues.

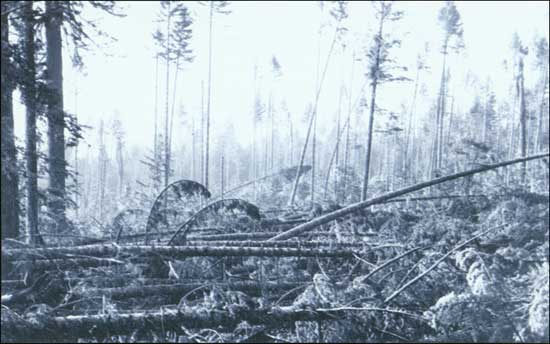

Many of BLM's 300-plus million acres of public domain

holdings in Alaska were destined for transfer to other federal agencies

and the state, once Native claims to the land were settled. Controversy

also broke out over allowable cuts for O&C forests, which wasn't

resolved until the end of the decade. In the minerals arena, Outer

Continental Shelf (OCS) lands, totalling 2 billion acres, witnessed

great growth in drilling activity.

|

|

|

A NEW CONSERVATION PHILOSOPHY

|

|

|

Under Karl Landstrom, BLM began to transform itself

from an agency primarily processing land and mineral applications into

an agency actively planning for the nation's future needs. The Bureau

stepped up inventories of public land resources and invited the public

to help decide how they should be managed.

The Bureau's state advisory boards and National

Advisory Board Council (NABC) were reorganized in 1961 to broaden their

representation by public land users. NABC's membership was increased

from 30 to 42, with representatives added from conservation groups,

county governments, forestry and mining interests, and the oil and gas

industry.

BLM was reorganized the same year; service centers in

Denver and Portland took over the functions of the Field Administrative

Offices and provided scarce skills (e.g., botany, hydrology, cultural

resource management) to the field. State Offices were strengthened,

bringing BLM's work closer to interested land users and groups, plus

state and local agencies. An Engineering Division was established in

Washington to assist in road building and other field office

construction activities.

Traditional programs continued to broaden their focus

to a multiple use framework. Range activities, for example, moved from

adjudication of grazing privileges to inventories of forage, soil, and

watershed conditions. BLM State Offices began to hire wildlife

biologists and outdoor recreation planners to implement new

programs.

|

|

|

During the 1950s and 1960s, a new breed of employee

entered BLM. He—or she—had college training in natural

resource management, usually a degree, plus membership in a professional

society (the Society for Range Management was founded in 1948; the

Society of American Foresters was founded in 1900). They brought with

them new educational backgrounds, new attitudes, and stronger multiple

use philosophies—and soon clashed with old-timers from the GLO and

the Grazing Service. George Turcott started his career with BLM as a

range conservationist in 1950 and rose through the ranks to become

Associate Director in the 1970s. According to Turcott, there was a

strong "don't-rock-the-boat" philosophy in the Bureau in the '50s and

early '60s. "We had all this [range] adjudication work to do and

everybody was trying to find ways to do it without making anybody

mad....We thought that there just had to be more to our jobs than

this."

|

|

Employees: A

New Breed |

|

SERVICE CENTER ROLE IN BLM

by Ed Dettman

Chief, Division of Administrative Services, BLM Service Center

Two service centers, one in Portland, Oregon and one

in Denver, Colorado, were established in 1963. They replaced Field

Administrative Offices (FAOs) in Salt Lake City, San Francisco, and

Portland. The service centers were premised on two fundamental

principles to achieve economies of scale through centralization of

administrative and technical equipment and personnel, and to provide an

effective setting for scarce skills which could be utilized jointly by

field offices and BLM's Washington Office.

The fundamental structure for both centers was the

same, but external factors resulted in significant differences in staff

sizes and assigned functions. For example, all financial processing

functions (voucher audit, payroll, and payments) were centralized in

Denver due to the Treasury Department's major disbursing office there.

Likewise, the initial start-up costs for mainframe computing equipment

and staffing dictated the formation of an Automated Data Processing

organization in Denver without a full counterpart in Portland.

In 1973, the Portland Service Center functions were

consolidated into the Denver Service Center. Based on cost efficiencies

and other factors, the Records Improvement Project and the Western Field

Office for reimbursable cadastral surveys for other agencies were left

duty-stationed in Portland with management oversight and direction from

Denver.

Throughout the 25 years of its existence, the role of

the Service Center has been constantly changing and always

controversial. Its sincerest critics highlight instances in which

Service Center initiatives have lacked either the field offices'

pragmatic sensitivity to political realities or the Washington Office's

sense of policy integration and timing. Its sincerest advocates point to

the unwavering connection between new skills, systems and technologies

which have come into the Bureau at all levels and their genesis and

support by Service Center personnel and initiatives. The Service Center

concept, constantly adjusted to meet changing needs and priorities, has

proven to be an enduring and essential element in the development of

improved technical, administrative, and scientific support for public

land management.

|

|

|

Like Turcott, many employees moved throughout the

West and to Washington to build their careers. And like their

predecessors, they recognized that the public lands had many values and

uses. They saw the Forest Service attain multiple use management

authority in the Multiple Use Sustained Yield Act of 1960, which

recognized wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation as resource

programs. At all levels of the organization, they wondered why BLM

didn't have the same mandate.

|

|

|

A LAND OFFICE BUSINESS

|

|

|

Much of the pressure to review and modernize the nation's land laws came

from a backlog of applications for agricultural entry that developed in

the 1950s. In 1961, BLM implemented an 18-month moratorium on accepting

any further applications so that it could reduce a backlog of more

than 60,000 applications—some pending for more than four years. BLM

needed to review its overall lands program and devise a better system

for handling applications. To back this up, BLM documented what happened

with applications under the Homestead and Desert Land Acts.

The 'Land Office business' has been very glamorous at times; sort of

romantic at times; but hectic most of the time.

— Karl S. Landstrom

|

|

|

A DIRECTOR'S PERSPECTIVE: 1961-1963

by Karl S. Landstrom

Karl S. Landstrom (Jennifer Reese)

|

Editor's Note: Karl S. Landstrom entered government as a farm economist

with the Department of Agriculture in 1937 and joined BLM in 1949. He has

degrees in economics from the University of Oregon and in law from George

Washington University. Landstrom was named BLM Director in 1961. In 1963

he became Secretary Udall's assistant for land utilization and later served

as his representative to the Public Land Law Review Commission's Advisory

Council.

I joined BLM's Portland regional office in

1949 as a land economist. In 1953 was transferred to Washington

because I had declined to classify certain public lands in Idaho as

proper for entry under the Desert Land Act—lands that were

unsuitable agriculturally or that had questionable water supplies. I

learned of my impending transfer two weeks before official notice from a

commercial land locator operating in Idaho.

While I was in Washington I served as Chief of the

Bureau's Branch of Land Classification in the Division of Land Planning.

I drafted regulations and manuals, wrote case decisions. and testified

on the Hill on pending lands legislation. I also developed a training

program on land appraisal standards.

I left BLM in 1959 to become a legislative consultant

to the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, where I worked

until 1961. While there, I worked with Stewart Udall, who was a member

of the Committee. During the change in administrations I applied to be

Director of BLM through Mr. Udall. I understand that my appointment had

been endorsed by Wayne Aspinall, Chairman of the Committee.

By January of 1961 BLM was beset with an intolerable

backlog of land disposal applications. The backlog was an embarrassment

to BLM employees who worked with the public and were criticized as

though they, and not the land laws themselves, were the cause of the

situation.

Under a general land reform program instituted under

President Kennedy and Secretary Udall, the Bureau moved ahead with

deliberate speed. Associate Director Harold Hochmuth and I took

aggressive steps to remedy the situation, beginning with an 18-month

moratorium in 1961-62 and continuing into a legislative campaign, later

culminating in far-reaching reforms. Numerous drafts of proposed land

law legislation were submitted by BLM through the Department to the

Congress. The process had been set in motion leading to the

establishment of the Public Land Law Review Commission in 1964.

Something also had to be done to curb widespread loss

of public confidence in BLM, from both commercial and conservation

interests. BLM was sharply criticized by both grazing users, who

resented proposed cuts in grazing allotments, and wildlife interests,

who demanded that overgrazing be eliminated. The morale of employees in

the Bureau had suffered on account of these problems and an influx of

top personnel from outside the agency during the preceding eight

years.

As Director I took care to assure that most top-level

personnel were selected from within BLM ranks. In addition, I worked to

establish multiple use advisory boards that were more representative of

our many constituents. After my first meeting with BLM's National

Advisory Board Council, I recommended it be reorganized to reflect a

more balanced viewpoint toward public land administration.

Reorganization of the Council and the state-level boards was approved

by the Department

The Vale project in Oregon gave new life to rangeland

rehabilitation. It marked the beginning of a movement that proved highly

beneficial in improving rangelands—and general relations between

ranchers and BLM.

The project gained impetus in remarks I made at the

end of a meeting BLM personnel had with people in Vale County, Oregon,

including Congressman Al Ullman and Senator Wayne Morse. I said how much

I would like to see efforts toward range rehabilitation expanded, such

as increasing sagebrush removal and the planting of crested wheatgress.

Senator Morse asked how much money it would take. I made a quick mental

guess and said something like $15 million and three years. The formal

estimate was not much different. The upshot was we got immediate funding

for a pilot project in the Vale District. Other Senators soon got wind

of this work and obtained funding for their own projects.

The 1961 reorganization eliminating regional offices

established State Offices as the major second level of administration,

supported by service centers in Portland and Denver. Another

accomplishment was the decentralization of plat and tract book records

from Washington, DC to the land offices, further saving costs and

expediting service to the public. But to be very frank, this move was

stimulated by Secretary Udall, who learned there used to be a gymnasium

in the Interior building, which was now occupied by these voluminous

records. He asked me to clear them out, which I did; thereafter BLM

employees and others shot baskets and played volleyball as well as

enjoying the gym's new sauna!

I found it relatively easy to reinstate a

conservation-minded administration under Secretary Udall's "Third

Conservation Wave," although there were a number of difficulties along

the way. I found at times that members of the Secretariat were acutely

sensitive to pressures from commercial groups, especially when voiced

through members of Congress or their staffs.

After leaving the Bureau I worked as Assistant to the

Secretary for Land Utilization and served as the Department's member of

the Public Land Law Review Commission's Advisory Council. My greatest

achievement, in cooperation with friends from the Forest Service, was

preventing the substitution of 'dominant use' for 'multiple use'

management on the public lands. In the 1960s there were members of

Congress who felt that multiple use was merely a "meaningless jumble of

words."

Ed Cliff of the Forest Service joined with me in

defending multiple use, a professional concept going back to the first

conservation wave under President Theodore Roosevelt. This effort

culminated the work I began as Director to seek formal recognition of

multiple use management for BLM lands.

|

|

|

Farming on arid western lands was a formidable

challenge if one lacked a dependable water source. Only 14 percent of

Homestead applications were being allowed by BLM and, of these, only

about 50 percent went to patent and were transferred into private

ownership after residency and land development requirements had been

met. Only 17 percent of Desert Land Act applications were approved by

BLM, and only 1 percent ever went to patent.

About 120 patents were issued annually during the

1950s for public lands in the lower 48 states. In Alaska, 150 patents

were granted annually; in 65 years, only 3,200 patents were issued

(totaling 400,000 acres, or 0.1 percent of Alaska's total land area) out

of more than 10,000 claims.

|

|

|

|

A successful desert land entry depended on a reliable water supply. (BLM)

|

|

|

When BLM's moratorium was lifted, BLM implemented

what Landstrom termed a "petition-classification system" that cut by

more than half the time to process applications. Demands for public

lands by communities and industries, however, continued to grow. The

Recreation and Public Purposes Act limited most sales of lands to 640

acres. BLM needed more flexibility, plus a mandate to classify and

manage its holdings.

In 1962 Assistant Secretary John Carver notified

Congress that the nation's nonmineral public land laws were in need of

modernization. BLM had shown that lands suitable for agriculture had

already passed out of federal ownership. The Bureau also needed formal

recognition of what it was beginning in earnest under Secretary Udall:

multiple use management of the nation's public lands.

Three acts passed in 1964 as part of a legislative

package arranged by Wayne Aspinall, Chairman of the House Interior and

Insular Affairs Committee. The Department got the Classification and

Multiple Use Act plus the Public Land Sale Act, while Aspinall got

approval for what he wanted, the Public Land Law Review Commission

(PLLRC). As part of this deal, the Wilderness Act, which did not include

BLM lands, was released from Aspinall's committee and passed both

Houses.

Aspinall had become increasingly wary of the

initiatives proposed by the Executive Branch—and disagreed with

their direction. Wanting Congress to reassert what he felt was its

traditional role in establishing land policy and supervising agency

activities, Aspinall was successful in insisting that the CMU and Public

Sale Acts be made temporary pending Congress' study of the public land

laws.

|

|

|

CLASSIFICATION AND MULTIPLE USE ACT

|

|

|

The CMU Act became BLM's biggest challenge—and

opportunity—of the decade. People in BLM, the Department, and

Congress differed greatly over the act's interpretation and

implementation. Central to this story were BLM's people: employees

determined how BLM got its job done and how it emerged as a land

management agency.

Though only a temporary authority, the CMU Act

provided a definition of multiple use as the "combination of surface and

subsurface resources of the public lands that will best meet the present

and future needs of the American people." The act listed ten elements of

multiple use, including wildlife, recreation, watershed, and range, and

directed BLM to classify its lands for retention in federal ownership or

disposal. But it did not specify how much land should be classified.

At the time it passed, no one in Congress (or BLM)

thought the Bureau could inventory and classify the majority of its

holdings in the 11 western states by the time the act was set to expire

in 1968. But it did, classifying more than 175 million acres for

retention in federal ownership under multiple use management (including

32 million acres in Alaska) and 3.4 million acres for disposal.

The CMU Act changed BLM forever: it would no longer

classify lands on a case-by-case basis, evaluating petitions from land

users. BLM now planned how all its lands and resources would be managed.

The Bureau no longer managed its holdings along individual program

lines; it integrated each activity into land use plans that would "best

meet the present and future needs of the American people." To do this

required involving the public in BLM's decisionmaking process.

|

|

|

Under Charles Stoddard, regulations for the CMU act

were developed with public input and comment. Draft regulations were sent to

interested individuals, organizations, state

and local governments, and other federal agencies for review, and they were discussed at 65

public meetings throughout the country.

|

|

CMU

Regulations |

|

The final regulations, adopted in October 1965,

incorporated many changes suggested by people outside BLM. As future

events would confirm, this was only the beginning of public

involvement for the Bureau.

The CMU Act required that BLM's classification

activities be consistent with state and local government programs,

plans, and zoning regulations. Proposed classifications were sent to

state and local governments and planning commissions. Proposals for

retention were sent to these entities as well as to public land users

and BLM's multiple use advisory boards.

BLM classified lands by collecting and analyzing

information on areas and their uses, and then contacted individuals,

groups, and agencies for further information. Meetings were held to

assess public attitudes and sentiments about retention or disposal

actions. BLM then drafted a proposed classification, published it in the

Federal Register, and held a public hearing. Only then were

classifications made final, through publication in the Federal

Register.

BLM met with the National Association of Counties,

the U.S. Conference of Mayors, the National League of Cities, and the

Council of State Governments to explain and implement the CMU program.

As a result of these discussions, BLM decided to work with pilot

counties in each western state to test the classification process.

County governments developed planning and zoning regulations and the

Bureau held an Urban and Rural Land Planning Conference in Reno, Nevada,

to explain the act and to develop classification procedures.

Valley County, Montana, was the first successful test

of the process. BLM's initial assumption that scattered lands would be

classified for disposal was opposed by the public—many of these

lands had scenic or recreational values or provided access to larger

public land areas. Local groups urged BLM to focus its efforts on larger

blocked areas under the CMU act, which BLM did. In 1966 BLM classified

its first lands under the act: 614,000 acres for retention in multiple

use management.

Another pilot project proved a formidable challenge:

Clark County, Nevada had several jurisdictions with competing annexation

programs. The CMU Act required that a single comprehensive plan be

developed for the area. To reconcile their differences, groups within

the county formed the Las Vegas Valley Planning Council, which eventually

devised a plan for the county's 7 million acres.

During this process, a recreation committee, with

involvement of local citizens, developed a plan for the Spring Mountain

area, which was classified for retention and then designated by

Secretary Udall in 1967 as the Red Rocks Recreation Lands—the first

such designation made under the CMU Act.

|

|

|

|

White Rock Spring in Red Rocks Recreation Area (BLM)

|

|

|

Other classification efforts confirmed that the

public favored retention of almost all the public lands in federal

ownership—and this from almost all BLM user groups. Livestock

operators, wildlife groups, and recreationists wanted continued use of

the public lands, and only retention could provide this.

Because the CMU act was a temporary measure, BLM's

first regulations provided that its classifications would expire at the

time the act did. But in 1967 BLM convinced the Department that CMU

classifications had long-term values and should be continued

indefinitely.

In implementing BLM's large-scale classifications,

Director Rasmussen convinced Secretary Udall to back the field's

broad-brush approach, with the idea that classifying public lands in

large areas decide their fate once and for all. Once this was done, it

would be difficult to undo—and only Congress or the Secretary could

do it—freeing BLM to manage its holdings under a multiple use

mandate. In this way, BLM's National Resource Lands were established, in

a manner somewhat analogous to the creation of a system of national

forests.

|

|

|

THE CLASSIFICATION AND MULTIPLE USE

ACT

by Irving Senzel

Editor's Note: Irving Senzel began his career with

the General Land Office in 1939. In his more than 30-year career, Mr.

Senzel held many positions. including Chief of the Division of Lands and

Minerals Standards and Technology under Director Stoddard and Assistant

Director for Lands and Minerals under Director Rasmussen. In these jobs he

was responsible for overseeing implementation of the Classification and

Multiple Use Act of 1964.

What role did I play in the CMU Act program? Well, I

had nothing to do with drafting the law. That was done in the House

Interior Committee. However, because of the Lands and Minerals positions

I held (Division Chief and later Assistant Director), I became involved

in its interpretation and implementation.

After the House enacted the bill, I was told not to

propose any amendments; I initiated two letters to the Senate Interior

Committee interpreting provisions of the bill that I thought were

ambiguous. These letters later proved important to our defense of our

program, particularly since they dealt in part with the question of

segregating lands from locations under the mining laws. Our remarks were

significant since the Senate passed the House bill without amendment.

In the implementation of the CMU Act, I had primary

responsibility for the preparation of classification regulations,

drafting of manual sections on public-participation procedures, and

monitoring progress of the program. In this work, we were plowing new

ground in active give-and-take with the public in the public lands

areas. We were anxious to make sure that our field efforts were

conducted in a fully professional, objective manner.

The field undertook program operations with

enthusiasm. BLMers spent long hours, including evenings and weekends, in

preparation, public meetings, discussions with State and local

officials, show-me tours, and what not. All this soon resulted in a flow

of classification orders for publication in the Federal Register.

Our progress apparently took some people by surprise, for from the Hill

and a couple of other places came demands that BLM stop its work under

the Act.

In a Director's staff meeting called to discuss this

development, I argued against acceding to this demand chiefly because

(1) what we were doing was consistent with the directives of the law,

(2) our interpretations, proposed regulations and criteria, and proposed

field procedures were all exposed to detailed public and Congressional

scrutiny before adoption, (3) the general public in the public-lands

areas responded well to our operations, and (4) surrender without a

fight would be a serious blow to field morale, which was then very high.

Field personnel were doing a job they thought needed to be done.

We took the matter up with Secretary Udall, who then

gave us the green light to continue with our work. The Hill was informed of this decision.

When the statutory period terminated, the field had

completed classifications for more than 150 million acres, a remarkable

achievement especially since the Bureau received no additional funding

from the Act to do this pioneering work.

|

|

|

Proof of the public's support for retention of BLM

lands in public ownership came in July 1968, when BLM proposed to

classify 119,000 acres of lands in Pima and Pinal counties, Arizona, for

disposal (along with 354,000 acres for retention). Objections from the

public and user groups caused BLM to abandon the proposal; the acreage

to be disposed eventually dropped to 6,600 acres.

Some in Congress—Wayne Aspinall in

particular—strongly disagreed with BLM's approach, asserting that

the agency was stretching its authority. A critical test of BLM's

strategy came when Aspinall wanted to extend the Public Land Law Review

Commission Act without the CMU Act. The Senate (Senator Jackson in

particular) would not agree to this request and extended both acts until

1970.

While lands classified for retention were segregated

from settlement laws, they were not precluded from mineral leasing or

most mining activity. Less than 1 percent of the lands classified for

retention were segregated from mining, and these were generally areas

under 1,000 acres identified as valuable recreation areas, wildlife

habitats, or cultural resource sites.

Once the public land tenure issue was decided, BLM

was ready to recognize special values on the public lands and designate

special management areas. According to Assistant Director Jerry

O'Callaghan, "the classification [process] identified public values

which could have been lost in a case-by-case classification." BLM's

first primitive areas, Paria Canyon and Aravaipa Canyon, were created

through BLM land classification actions in 1969, along with the

Vermillion Cliffs Natural Area.

According to former Director Marion Clawson, the

Classification and Multiple Use Act "gave the Bureau a psychological

lift that has led to its taking the initiative more and more often." The

act made public involvement and interagency cooperation a permanent part

of public land management. By July 1968, 188 local government boards and

commissions had reviewed proposed classifications. More than 15,000

local officials participated in CMU public meetings and hearings.

|

|

|

THE PUBLIC LAND SALE ACT

|

|

|

The Public Land Sale Act allowed BLM to sell tracts

of land up to 5,120 acres "for the orderly growth and development of

communities" after local zoning and planning had taken place. To

implement the act, BLM District Managers met with local governments and

planning commissions in ten test counties to develop cooperative

procedures.

The Act required that lands be classified under the

CMU Act before they could be sold. Lands were then appraised and sold at

fair market value to state or local governments or high bids were taken

at auction from private individuals, organizations, or corporations

meeting the act's criteria.

|

|

|

REORGANIZATION

|

|

|

Using the CMU Act as his authority, Charles Stoddard

reorganized BLM in 1965 to integrate new programs. New divisions

(wildlife, recreation, and watershed) were created in the Washington

Office and the Bureau's line managers—State Directors and District

Managers—were strengthened with new responsibilities to coordinate

on-the-ground activities. Budget work and program evaluation were moved

from BLM's program staffs and consolidated under the Assistant Director

for Administration and the Division of Program Evaluation to further

integrate and organize the Bureau's activities.

By this time, added workloads and management

responsibilities in the field were making BLM District Offices too large

for managers to have a working knowledge of everything that occurred in

their districts. An organizational study of BLM in 1964 by Dr. George

Shipman of the University of Washington recommended that BLM change its

organizational structure and management systems to provide better

service to public land users. Another major conclusion, according to

former Colorado State Director Dale Andrus, was that "coordinated land

use decisions had to be made at the grass-roots level."

|

|

Detached

Resource

Area Offices |

|

A NEW EMBLEM FOR BLM

by Charles H. Stoddard

The tired old emblem of user groups—the logger,

cowboy, oil driller, and surveyor—produced a poor image, never had

Bureau acceptance, and was too busy for reproduction. Accordingly, we

held a contest in 1965 to develop a new emblem. The winning emblem

features today's winding river, grassland, a conifer tree, and a

mountain, snow-capped as a result of mountain climber Udall's

suggestion.

|

|

|

Serving as a Management Analyst and Assistant

Director in Washington in the 1960s, Andrus was responsible for much of

the organizational work in creating BLM Resource Area Offices. According

to Andrus, it was critical that the Bureau designate a single official

to manage and be responsible for all BLM activities in a specific

geographic area. These activities included land use planning, managing

minerals and natural resources, processing lands cases, and providing

information to the public. A general rule of thumb of three to four

areas per district was set forth in the implementing instructions,

according to Andrus. "Criteria used to identify Resource Area boundaries

were kind and amount of workload, geographic barriers, political

subdivisions, and watershed basins."

By 1965, several Bureau field offices had already

followed Idaho's lead in establishing "Division Managers" within

Districts, making them responsible for management of specific geographic

areas—with the District Offices providing planning and program

coordination, plus technical and administrative assistance. Resource

Area Offices were officially recognized in July 1966 in BLM Manual

Section 1213.37. Special project offices or unit offices in O&C

Districts (e.g., Tillamook, Oregon) were already performing this

function; in other locations (e.g., Durango and Meeker, Colorado) former

District Offices were converted into detached Resource Area Offices

during statewide reorganizations.

|

|

|

PLLRC: A CLOSER LOOK AT PUBLIC LAND MANAGEMENT

|

|

|

At the same time BLM was classifying its lands for

retention in multiple use management or disposal to the private sector,

the Public Land Law Review Commission was studying the nation's 3,000

land laws and federal management of the public domain to identify

problems and recommend new policy, programs, and legislation. Its

Chairman, Wayne Aspinall, had strong disagreements with BLM and the

Department over how the Bureau was carrying out its

responsibilities.

The Public Land Law Review Commission (PLLRC) was

established mainly through the efforts of Wayne Aspinall. While

Presidents Kennedy and Johnson and the Interior Department were

introducing conservation related legislation to the Congress, Aspinall

was trying to get Congress to rebuff these initiatives and establish

federal land policy by itself. At the commission's first meeting,

Aspinall was named chairman. Other members included six senators, six

representatives, and six presidential appointees. An Advisory Council

was formed with liaison officers from each of the land-managing agencies

plus 25 members appointed by PLLRC to represent land users.

PLLRC commissioned studies on commodities and land

uses, intergovernmental relations, regional and local land use patterns,

government management of public lands, and historical development of

public land laws. Its reports included studies of fish, wildlife,

forage, and mineral resources; OCS lands; future demands for

commodities; withdrawals and reservations; and virtually every other

land management policy or activity BLM was involved in. Conservation

groups and most of the public, however, were not involved in this

process and ignored it, focusing their attention on wilderness debates,

oil spills, and Alaska policies, plus passage of the National

Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and other conservation legislation.

|

|

|

A DIRECTOR'S PERSPECTIVE: 1963-1966

by Charles H. Stoddard

Charles Stoddard (Jennifer Reese)

|

Editor's Note: Charles Stoddard worked for the U.S.

Forest Service, the Bureau of Agricultural Economics and private

research foundations, including Resources for the Future, and was

director of Secretary Udall's Program Staff before serving as Director

of BLM. He holds degrees in forestry and forest economics from the

Universities of Wisconsin and Michigan.

During three years as Director, I oversaw major

changes in organization structure, program direction, and land-use

planning—changes that were designed to help BLM clarify its goals

and evolve into today's multiple-use organization.

Prior to my arrival, BLM had Professor George Shipman of the University

of Washington study the Bureau's organization structure and

recommend improvements. He saw the BLM as divided,

uncoordinated, and unilateral in structure, citing its case-by-case

orientation, its custodial (as opposed to managerial) approach, and its

lack of a mission or goal. He went on to say, "Unless you can spell out

a goal, a set of objectives, I can't be of much value to you nor can I

come up with any organizational recommendations. Organization must be

tailored to mission."

I feel my major contribution as Director was to help

define our problems so that we could set forth clear objectives, and

tailor BLM's organization structure to carry out programs that would

meet these objectives.

Following the analysis made by Professor Shipman, BLM

went through a major Washington Office reorganization, going from a

five-functional group structure (survey, minerals, lands, forestry, and

range) to a basic staff and line structure. The line established was

from Assistant Directors through the State Offices to the Districts. In

addition, we replaced single purpose, case-by-case directives with

coordinated instructions to field offices, amidst cries of protest from

guardians of the status quo.

In lieu of a regional office set up, Service Centers

were established in Denver and Portland to provide technical support to

State and District offices. The Boise Interagency Fire Center was

established in 1965.

Legislative Developments—Except for the Taylor

Grazing Act of 1934 and the O&C Forestry Act of 1937, BLM was hemmed

in by old disposal laws and special bills for relief of individual

situations. This deadlock was broken by providing classification

criteria in the new Classification and Multiple Use Act, which were

applied to the lands prior to their retention or disposal. Because there

would be impacts arising from changes in land use, we made certain that

regulations provided a system of public meetings at the grass roots to

institutionalize local participation in the land management

decisionmaking process. This began a process for stabilizing the tenure

of retained lands by the Public Land Law Review Commission and,

ultimately, FLPMA.

Resource Management Programs—Resource project

work varied considerably in the field. It was carried on without effective technical

guidelines from Washington or State Offices and was carried out by user

request rather than program need. For example, when BLM field staffs

initiated soil and water conservation projects, many were installed off

the contour—thus increasing erosion.

BLM's grazing management lacked modern range

management techniques such as rotation grazing. I asked Dr. Glen Fulcher

from the University of Nevada to head up our Range Staff. Fulcher

brought in Gus Hormay, a Forest Service researcher who had developed a

"rest-rotation" grazing system designed to bring about range

reestablishment in over-grazed areas without reseeding. Enthusiasm for

this new approach grew: when I left BLM an average of one rancher per

District had a rotation plan under practice.

Management of the Bureau's forest land was subject to

considerable pressure from user groups seeking regular increases in

allowable cut limits. We curtailed excessive expansion of these

sustained yield limits in several confrontations where the public

interest was able to override local pressures.

Much of the Bureau's Soil and Moisture funds were

allocated to range improvements—not to eroding lands nor to

efforts to restore overgrazed lands. A special Frail Lands Study,

undertaken in 1964 by Cyril Jensen and Clarence Forsling, identified

about 45 million acres of public land on which accelerated erosion was

taking place. Senator Hayden was instrumental in obtaining

appropriations for BLM to begin genuine erosion control efforts.

Although the Bureau had authority for managing

wildlife habitat under the Taylor Grazing Act, no active program was in

operation nor were funds directed to this purpose. In 1964, Bob Smith

(former Arizona Game and Fish Director) put wildlife on an equal footing

with forestry and recreation. Al Day, former Director of the Fish and

Wildlife Service, examined the wildlife program and laid out plans for

habitat improvement, location of wildlife managers in Districts with

heaviest wildlife resources, and a variety of special projects.

Land Use Planning—Multiple use management plans

had never been instituted in the Bureau because of its single-purpose approach (range,

forestry, etc.). A workable planning system, the Unit Resource Analysis, was implemented

after considerable testing in the field. URAs provided the Bureau's first means of integrating

all project work and land use for a District into a management system.

Personnel Matters—Modern resource management

requires not only technical expertise from many disciplines but also

knowledge of social sciences and administrators who can blend all

disciplines into a unified program. I sought to encourage "generalists"

in the Bureau and to give them a separate ladder for advancement.

Lacking any trained land use planners in BLM, I instituted a special

program at the University of Wisconsin in regional planning.

Minority group employment in BLM lagged. This was

partly because of inertia and a lack of people trained in the fields

needed by BLM. I initiated efforts to recruit Native Americans in areas

near BLM operations plus blacks from southern agricultural schools.

In my opinion the Bureau of Land Management has some

of the best trained personnel available in government. I'm proud to have

been associated with these fine employees and look back with pride on my

years with the BLM. To assure a solid future, BLM must remain a land

management agency—in place of its real estate disposal past.

|

|

|

In 1970 PLLRC released its report, "One Third of the

Nation's Land." Reflecting Aspinall's sentiments, it asked Congress to

establish policy on a variety of public land matters. The report

recommended that all federal lands not specifically set aside by

Congress, such as national forests and monuments, be made eligible for

disposal—but in another section stated that the nation's policy of

disposing the unappropriated public domain be reversed.

PLLRC also proposed merging the Forest Service and

BLM into a Department of Natural Resources (a proposal soon taken up by

Presidents Nixon and Carter). The commission recommended that Congress

limit the exercise of Executive authority, especially on withdrawals,

and called for Congress to determine revenues for consumptive uses of

federal lands. PLLRC further recommended grants of federal funds to

states and counties in lieu of taxes.

In these proposals, PLLRC proved prophetic: Congress

soon began prescribing specific management techniques and standards to

be followed by federal agencies, thus limiting their traditional

discretion in management actions and policy implementation. But PLLRC's

report, though voluminous, was often contradictory. Its recommendation

to classify public lands for their "highest and best use" was seen as an

endorsement of dominant use over multiple use on the public lands.

Life Magazine reported that the PLLRC report

was written by people "who believe in the commodity approach...and

consequently it gallops headlong in the wrong direction." Sports

Illustrated said that Aspinall's commission recommended "accelerated

exploitation and disposal of the lands" and that its recommendations

were made "on the basis of little publicized hearings and highly

secretive deliberations." Professor Paul Culhane reflected that "many of

the commission's recommendations appeared to have little impact on

federal policy, perhaps because they seemed too pro-industry and out of

step with the times when released during the fervent early years of

environmentalist activism. However, the PLLRC firmly asserted that the

era of disposal of public lands was over."

Thus, while President Nixon proclaimed NEPA as

heralding the start of an environmental decade in 1970, PLLRC "played to

an empty theater" according to Dr. Sally Fairfax. But few others in

Congress or elsewhere had examined public land issues. PLLRC's studies

and recommendations were available when the public and Congress were

ready to address public lands issues—which would be soon. PLLRC compiled

a great deal of information and opened a discussion that continued

through passage of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act.

|

|

|

PLANNING: THE DEVELOPMENT OF MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK PLANS

|

|

"If we are to maintain man's proper relationship with nature...we must

broaden the role of resource planning in the

management of our national affairs."

[DOI Annual Report - 1961]

Implementing multiple use management on the public

lands required planning. And effective planning required that the public

be involved in BLM's decisionmaking process. Once this was begun, there

would be no turning back; the public took an increasing interest in BLM

and increasingly did not agree with the agency's management.

The story of planning in the 1960s is the eventual

development of Management Framework Plans (MFPs), integrating all of the

Bureau's on-the-ground activities into a single effort. As a first

step, the Bureau needed a way to develop land use plans independently of

the applications it received. The Master Unit system was created in 1961

for BLM to decide on land tenure before reacting to specific land-use

applications. Units of study (Master Units) were defined, information

gathered, and the data analyzed to determine potential land uses. The

Bureau then categorized its lands into title transfer projects, land

management projects, and residual management areas where detailed

land-use plans would not be appropriate.

In 1963, working with state agencies and county

commissions, BLM developed a plan to coordinate Recreation and Public

Purposes Act (R&PP) land transfers in the Las Vegas area and manage

the remaining public lands. Citizen groups were involved on a recreation

subcommittee while county commissions developed overall plans.

Once the CMU act passed, BLM Director Charles

Stoddard created the Office of Program Evaluation in Washington to

develop a multiple use planning process for the field. BLM's challenge

was to devise a planning system that would incorporate individual

activity plans (master unit, allotment management, and watershed plans)

into more general area plans. The system had to be clearly understood by

employees, constituents, and the public, and be standardized enough to

ensure consistent results across the Bureau. It also needed to integrate

the resource allocation techniques used by different programs.

Stoddard, originally from Wisconsin, knew of a

successful land use planning system used in his state during the 1920s

and 1930s. The system featured land classification and zoning

procedures—plus participation and approval from the public before

final decisions were reached—and served as a model for BLM's

system. Nevertheless, implementation of a comprehensive planning system

represented a major organizational change for the Bureau. Field managers

needed to be convinced that a uniform, Bureauwide land use planning

system was needed when they were used to doing these jobs in their own

ways. Several attempts and many years were necessary to implement a

workable system. To encourage the process, Stoddard began sending BLM

managers to the University of Wisconsin for training in regional land

use planning.

BLM's first step was to identify planning units and

collect resource data. Unit Resource Analyses (URAs) were prepared to

summarize resource inventory data collected in planning units.

Social and economic data were also collected so that they could be

considered when it came time to develop management alternatives.

But then what? More than a few field managers were

apprehensive about a system that would require public involvement and

identify management alternatives before BLM arrived at decisions. Why

should BLM tip its hand to users and the public in the early stages of

its decisionmaking process? In many districts, BLM would have enough

controversy to handle once a final decision was made.

Finding a way for each program and the public to

identify and advocate resource uses—and follow them through the

process so that no potential was overlooked—was tricky. How would

disagreements be resolved? How much would the public be involved in

decisionmaking? BLM planners had a long way to go to convince BLM field

offices that planning was a good and necessary thing—and that using

the system to address and resolve differences among land users would

save the Bureau from repeated headaches in the future.

An important step in getting MFPs off the ground was

testing the process in the field and showing it would work. In 1968, Art

Zimmerman, District Manager of the Montrose District in Colorado, asked

to test the process to see if it could help resolve strong disagreements

on resource allocations among the district's user groups. After this and

further tests in Oregon and California proved successful, MFPs were

ready to be implemented in the field.

|

|

|

MINERALS

|

|

|

According to Director Stoddard, "BLM's minerals

activity could hardly be called a program" in the early 1960s. The

Geological Survey classified minerals, approved exploration and mining

plans, and monitored this activity, which "prevented BLM from giving

effective direction to location, rate, and timing of mineral exploration

and development."

Secretary Udall and BLM worked throughout the decade

to develop a minerals policy, one that ensured optimum returns of

revenue to the Treasury, resolved land use conflicts, and planned for

adequate mineral reserves in the future. The Interior Department's

Annual Report for 1962 had this to say about minerals: "In the past 30

years, this Nation has consumed more minerals than all the peoples of

the world had previously used....That current demands are being met

without difficulty is primarily due to the immense technical and

exploratory efforts of the 1940s and early 1950s. But with national

requirements constantly increasing, the present availability of raw

materials will not continue unless prompt action is taken to look to the

years ahead."

|

|

|

Before the mid-1940s, coal provided over half of

America's energy needs. Oil and gas rapidly supplanted it as the

nation's preferred fuel after World War II. However, interest in public

coal reserves revived in the 1960s due to advances in coal utilization,

processing, and transportation. Coal in the West was viewed as an

important future energy source because of its low

sulfur content—an important asset in reducing

air pollution.

|

|

Coal |

|

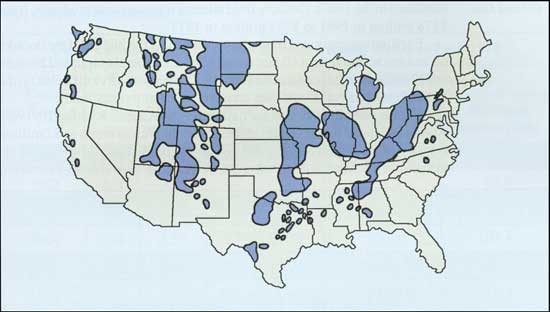

Half of the country's coal reserves occur west of the

Mississippi River and the government owns 60 percent of it, or about a

third of the nation's total. BLM was sitting on 75 million acres of

federally owned coal. Major hydroelectric facilities had already been

built and few new sites were available. Early warnings about declining

oil and gas supplies were largely unheeded by the public. The Interior

Department, however, readied itself for future demands for coal.

Secretary Udall created the Office of Coal Research to complement the

Bureau of Mines' research efforts.

|

|

|

|

Major U.S. coal fields

|

|

|

During the 40 years following passage of the General

Mineral Leasing Act of 1920, GLO and BLM issued an average of only

four coal leases a year. From 1960-69, that average increased to 31 per

year. By 1971, 17 billion tons of federal coal were under lease, enough

to satisfy America's coal needs for 25 years. Most of these leases,

however, were speculative: 70 percent were not producing. Major development of coal

came soon after, though, following the energy crisis of 1973.

|

|

|

Oil shale reserves were estimated to amount to 2

trillion barrels of petroleum, compared to onshore and offshore

oil reserves of 300 to 500 billion barrels. The problem with developing

oil shale, however, was the extreme heat (and expense) needed to process

the shale.

|

|

Oil Shale |

|

Secretary Udall appointed an Oil Shale Advisory Board

to study the situation and recommend policy. Because the group had

diverse points of view, an interim (but never final) report was released

in 1965. The board agreed that knowledge of oil shale needed to be

enhanced and that "the national interest is best served by the immediate

commencement of oil shale development."

In 1967, Udall announced a tentative oil shale

program to clear title to oil shale lands by withdrawing them from other

forms of mineral entry, blocking up oil shale ownerships through an

exchange program, issuing provisional development leases, and

cooperating with industry to develop better processing methods. The

program sought to encourage oil shale development, prevent speculation,

promote good conservation, and bring money into the Treasury. In late

1968 a number of oil shale leases were opened to competitive bidding,

but the offers were rejected by BLM as being too low.

|

|

|

The oil and gas leasing frenzy that characterized the

late 1950s stabilized in the 1960s. Onshore fluid mineral

revenues rose modestly, from $178 million in 1961 to $233 million in 1971.

|

|

Oil and Gas |

|

Exploration continued throughout Alaska. By the

middle of the decade, oil and gas accounted for 60 percent of Alaska's

mineral output and brought in $19 million to the state treasury. By

1970, there were five oil fields on the Kenai Peninsula and Cook Inlet

area and nine natural gas fields.

|

|

|

|

Offshore oil drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico (BLM)

|

|

|

The biggest oil strike was at Prudhoe Bay by Atlantic

Richfield in 1968. Alaska estimated that revenues to the state could run

as much as $1 million a day—which they eventually did. What was

needed was a pipeline to get the oil out of Alaska. In 1969, ARCO,

Humble, and British Petroleum announced plans to build a pipeline from the

North Slope to Valdez, stretching 800 miles across the state and costing

$900 million. In June the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System—later the

Alyeska Pipeline Company—filed a right-of-way application with

BLM, with plans to start construction in the spring of 1970. These plans

were contingent on settling Native claims and were ultimately affected

by the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act.

|

|

|

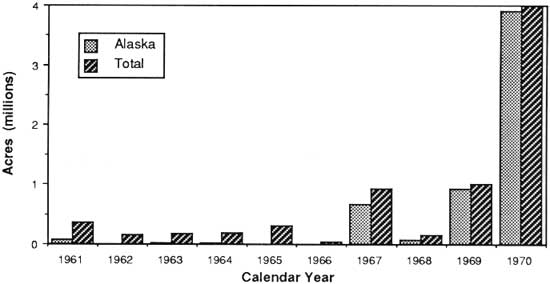

Revenues from the Outer Continental Shelf lands grew

dramatically in the 60s, from $442 million in 1961 to $1.1 billion in

1971. Development of this resource occurred from the humblest of

beginnings in 1959, when only $3.4 million was collected.

|

|

OCS Lands |

| Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Mineral Leasing Statistics 1961-1970 |

Fiscal

Year |

Gulf Coast |

West Coast |

Total Production |

Active

Leases | Acres

(millions) |

Active

Leases | Acres

(millions) |

Natural Gas

(1,000 cu. ft.) | Petroleum

(million bbl) |

| 1961 | 458 | 1.93 |

— | — | 298.1 | 48.5 |

| 1962 | 851 | 3.74 |

— | — | 354.5 | 65.5 |

| 1963 | 826 | 3.59 |

57 | .31 | 473.6 | 87.7 |

| 1964 | 824 | 3.50 |

57 | .31 | 526.2 | 107.4 |

| 1965 | 797 | 3.40 |

135 | .76 | 621.7 | 122.5 |

| 1966 | 792 | 3.29 |

116 | .65 | 645.6 | 145.0 |

| 1967 | 870 | 3.67 |

84 | .47 | 1,007.4 | 188.7 |

| 1968 | 815 | 3.41 |

85 | .44 | 1,187.2 | 221.9 |

| 1969 | 939 | 3.94 |

77 | .40 | 1,524.2 | 269.0 |

| 1970 | 931 | 3.93 |

70 | .36 | 1,954.5 | 312.9 |

|

|

In 1963 BLM opened an OCS leasing office in Los

Angeles and held its first lease sale on the West Coast, bringing in

$12.8 million for 58 tracts. But most offshore action remained on the

Gulf Coast. In 1963, OCS oil production off the Louisiana coast

represented 27 percent of total federal oil production, while gas

represented 37 percent. By 1967 more than 4 million acres of OCS lands

were leased by BLM, but this total represented less than 1 percent of

OCS lands with ocean depths of less than 600 feet.

|

|

|

ALASKA

|

|

|

The two biggest issues for Alaska in the 60s were the selection of

statehood grant lands and settlement of land claims made by Alaska

Natives. Alaska handled its state selections through its Division of

Lands. The Division's first chief was ex-BLM employee Roscoe

Bell, who had been Associate Director and then Regional Administrator in

Portland under Marion Clawson.

Bell's plan was to select lands that would further

the economic development of the state. Four million acres were selected

a year, or as he put it, "an area the size of Rhode Island every two

months," so that all 103 million acres due the state would be selected

in the 25 years allowed by Congress.

Alaska's selections during this period were

characterized by state officials as "small but carefully calculated." In

1964, the state selected lands at Prudhoe Bay that it thought had oil

and gas potential. How right they were!

To help the state select land, BLM received

additional funding for its surveys. Only 1 percent of the state was

surveyed under the Public Land Survey System by the time Alaska was

granted statehood. The Bureau therefore concentrated its efforts on

surveying state selections, planning to survey 4 million acres a year to

match Bell's selection schedule.

Alaska's sheer size required that new survey

techniques be developed. Electronic distance measuring devices were used in

the field; helicopters marked section corners and transported survey crews

throughout the state.

Problems immediately arose with the program, however.

The state refused BLM's request to select large areas forming "logical

topographic-geographic-economic units." Alaska interpreted its right to

select "reasonably compact tracts" in its statehood act as being 5,760

acres—a quarter township. With involvement of Alaska's

congressional delegation and Assistant Secretary John Carver, the issue

was resolved in the state's favor.

Alaska's biggest problem proved to be the claims of

its Natives. The U.S. had not recognized aboriginal title for Alaska

Natives, who consist of Eskimos, Aleuts, and Indians, as it did for

Indians in the lower 48 states. Instead, in 1906 Congress passed the

Native Allotment Act, which allotted each Indian and Eskimo 160 acres of

nonmineral public land but made no reference to Aleuts. Because the law

had no provision for passing title, the "allotments" were nothing more

than perpetual reservations. Provisions for patent weren't made until

1956; by 1962, only 101 allotments had been made under the

act.

Beginning as early as 1950, Alaska Natives petitioned

to have lands restored to them. In June 1963, BLM stopped processing

state selections in areas specifically protested by Natives until

Congress could act on their claims. By 1966, Alaska Natives claimed some

230 million acres of land.

Secretary Udall initiated an informal freeze that

stopped approvals on all state selections. Alaska then took Udall to

court. Facing an adverse ruling in December 1968, Udall formally

withdrew 260 million acres of public land from appropriation, asking

Congress to resolve the situation. Because Native claims were also

delaying selection of a route for the Alaska pipeline, Congress enacted

the the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971.

|

|

|

THE ALASKA STATE LAND SELECTION PROGRAM

A STATE PERSPECTIVE

by Roscoe E. Bell

Former Director of Alaska Division of State Lands

I had worked for BLM in Alaska in the mid-1950s. When

I returned to Alaska as State Director of Lands, my acquaintance with

Alaska and with BLM personnel was very helpful, and very important, and

I just wanted to compliment the BLM personnel in Alaska. They leaned over

backwards to help us get started in the State selection process. Of

course, they trained some of the people that we hired away from them,

but it was a tremendous help to have a cooperative government agency to

work with.

BLM personnel had been very influential in the draft

of the Alaska Land Act of 1959. Through them we got a really effective

land act for Alaska. They recognized the problems with the grants made

to early states and wanted to avoid the same happening to Alaska.

When it came to processing land selections, BLM was

very cooperative. When the State wanted lands in areas withdrawn from

selection, BLM did everything they could to jar loose revocation orders

to lift withdrawals so we could select the land and proceed with

leasing.

We set up our land records system along BLM lines so

we could coordinate land records, surveys, land selections, timber management, and fire

protection with the Bureau.

We had very good cooperation from BLM for protection

of the lands during the transition stage. At times, we'd make a

selection and get tentative approval of the selection. This gave the

State management authority of the land but we wouldn't get patent until

the survey was made and finally filed, which took 3 years or more. BLM

gave us free forest protection for the period between selection and

patent so we could go ahead and manage. Alaska had very little money at

that time and we needed fire protection of our future lands.

In the details of the land survey program, we had

quite a knock-down, drag-out argument with BLM Director Karl Landstrom,

but we had BLM support in Alaska. Under the Statehood Act, Alaska could

make selections of a certain minimum size and BLM would survey the

exterior boundaries of those selections. Well, Landstrom wanted us to

make larger selections, to minimize BLM's surveying job. Now, the State

of Alaska did not have any money to pay for the survey of smaller

selections. I wanted to get the maximum amount of surveys from BLM, so

we made our selections in a pattern of half-townships, which were twice

as large as the minimum size required. By this method, we would get a

pattern of survey corner monumentations that would give us a basic

survey net over land we'd selected. We went to the mat with Karl. But

with prodding from our Congressional delegation and others, we got

Assistant Secretary John Carver to go long with our idea.

There were many other places where we could have

gotten bound up forever in trying to work out problems. But as one BLM

man in Anchorage said, "why quibble over details, after all, we're

Alaskans too, and we are as anxious as you to see Alaska statehood

work." It was a good relationship, and I was real proud of the

relationship and spirit of cooperation we had with BLM.

|

|

|

Under State Director Burt Silcock, BLM Alaska

classified over 32 million acres of land in the state for retention

under the Classification and Multiple Use Act. An additional 38 million

acres of lands were proposed for classification at the time the act

expired, but most of the areas were included in Secretary Udall's Public

Land Orders withdrawing them from appropriation.

|

|

|

RECREATION: A GROWING USE OF THE PUBLIC LANDS

|

|

|

Continuing a post-World War II trend, more and more

Americans had more leisure time. They were better educated and more

aware of the nation's public land resources. In hearings throughout the

nation, the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission (ORRRC)

identified recreational opportunities on federal lands, including BLM

holdings. The public was beginning to see that BLM lands offered long

seasons of use and considerable variety.

In 1961, BLM's Oregon State Office issued a

recreation handbook containing policy, planning, site design,

development, and maintenance criteria. The Bureau hired its first

landscape architects in the field that year and gave them recreation

assignments. State Offices began to hire full-time recreation

specialists.

The Public Works Acceleration Act of 1962 provided

federal assistance to areas hard hit by recession and provided the

Bureau its first major funding for recreation site development ($1.9

million), mainly for campgrounds and picnic sites. In New Mexico, picnic

sites, trails, and campgrounds were built at the Rio Grande Gorge in the

Taos Resource Area.

When the ORRRC's final report was issued in 1962, a

logjam of pending legislation was introduced in Congress, including the

Outdoor Recreation Cooperation Act, the National Wilderness Act, and the

Land and Water Conservation Fund Act. Secretary Udall created the Bureau

of Outdoor Recreation that year to coordinate federal, state, and local

recreation planning and to provide grants to states that drew up outdoor

recreation plans.

In 1963 a Bureauwide recreation inventory was begun

to identify recreation sites, areas, and complexes, with this

information being passed along to the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation.

While most of this work was site-oriented, several trails were

identified. In its 1965 report, "Trails for America," the Bureau of

Outdoor Recreation identified over 3,600 miles of trails on public lands

and noted BLM's proposal to add 5,000 miles of new or rebuilt

trails.

In 1964 the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF)

Act authorized funds for the development of state and local parks and

expanded federal land acquisition programs for recreation—including

acquisitions for BLM recreation areas. Funds were raised from taxes on

recreational equipment, user fees in recreation areas, and general

appropriations. Amendments to the act in 1968 provided a broader

financial base and direct appropriations from OCS revenues to achieve an

annual minimum of $200 million. In 10 years this base was increased to

$900 million.

|

|

|

OFF-ROAD VEHICLE MANAGEMENT

by Ralph M. Conrad

Natural Resource Specialist, Division of Lands

Large and frequently successful programs often have

small innocent beginnings. BLM's beginning in off-road vehicle

management, as I recall, is a case in point. Some of the dates are fuzzy

with the passage of time, but the players and circumstances are well

remembered.

It all started in 1967 in a remote desert canyon in

Arizona. The initial players, a group of Girl Scouts and their leader, a

Phoenix newspaper man (Don Dedera), were still in their sleeping bags in

the early light of dawn. As later reported by Mr. Dedera in the

Arizona Republic, an annoying mosquito buzz steadily grew into a

roar as two motorcycles bore down on the sleeping-bag-encumbered Girl

Scout troop. Mr. Dedera successfully removed himself from his sleeping

bag and flagged down the second biker. Upon being asked what was going

on, the biker reportedly said, "If you think this is something, wait

until this afternoon—we have a race coming through here." When

asked who authorized the race the reply was, "No one—these are

public lands." Orren Beaty, then Four Corners Commissioner, clipped the

Dedera column and forwarded it to Secretary Udall with a short note

asking if something could be done about uncontrolled motor vehicle use

in the desert. The Secretary bucked the Dedera column and Beaty note to

Director Rasmussen with the added instructions: "Do something."

The Secretary's instructions filtered down through

the BLM Directorate to the Chief of the Recreation Staff (Eldon Holmes).

The Bureau's outdoor recreation program was in its infancy; most of its

funding was derived from BLM's lands program. There was no policy or

regulatory base upon which to justify a program. Draft regulations to

establish the outdoor recreation program had been developed by the time

the Secretary's instructions arrived but were having little success

getting through the surname process. Therefore, since ORV regulation had

the support of the Secretary, it was decided to interweave the ORV

regulations into the draft outdoor recreation regulations and kill two

regulatory birds with one stone. This would respond to the Secretary's

specific instructions while establishing the needed regulatory base for

the Bureau's outdoor recreation program.

Even with Secretarial backing, the regulatory package

had limited success. The Democratic Administration lost the election in

November 1968. A new administration would take its place on January 20,

1969. By mid-January, last minute programs of the outgoing administration

were being finalized. At about that time, word was received