OPPORTUNITY AND CHALLENGE

The Story of BLM

|

|

|

AN AGENCY WITH A MISSION:

The 1970s

In light of its multiple responsibilities and the complexities of its

programs, the Bureau has long needed a Congressional statement of policy

and a modern legislative mandate.

—Eleanor Schwartz

|

AN AGENCY WITH A MISSION

The 1970s

|

|

|

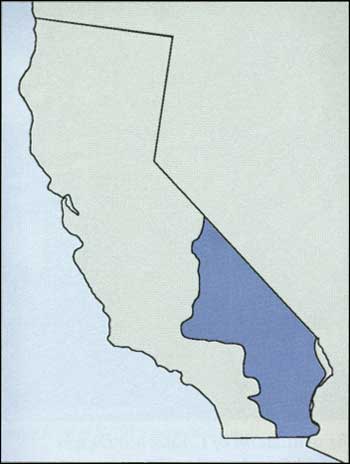

Thirty years after its formation, the Bureau of Land

Management was finally granted a mission. The Federal Land Policy and

Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA) formally recognized what BLM had been

doing on an interim basis for many years:

managing the public lands under the principles of multiple use and

sustained yield. FLPMA did much more, though—it granted BLM new

authorities and responsibilities, amended or repealed previous

legislation, prescribed specific management techniques, and established

BLM's California Desert Conservation Area. The Bureau was now in the big

leagues.

|

|

Overview |

|

The road to FLPMA proved to be dramatic. Public land

issues were discussed in three Congresses, with both old and new

constituents involved in the debate. The bill was approved at virtually

the last minute in a closed door session of a House-Senate conference

committee. It is a complex bill that reflects the nation's priorities in

the 1970s. Public participation and planning were the tools provided to

make management decisions.

The first day of 1970, however, opened with President

Nixon signing the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). NEPA

recognized that federal actions had impacts on the environment and

required that they be analyzed before management decisions were made.

The act established protection of the environment as a national goal and

encouraged federal agencies to set up environmental education

programs.

BLM and other federal land managers at first thought

NEPA was nothing new—after all, resource specialists considered

impacts of their work as a part of their jobs. But they were wrong. NEPA

brought profound changes to BLM. Its provision for environmental impact

statements changed the way the Bureau did business.

In addition to NEPA, Congress addressed specific

environmental concerns. Legislation was passed to protect air quality

and endangered species, and was amended to strengthen protection of

cultural resources and water quality. The Wild and Free Roaming Horse

and Burro Act of 1971 radically realigned BLM's management of these

animals, requiring protection and enforcement programs.

Increased public involvement showed BLM that land

management was becoming every bit as much a social and political

activity as a scientific endeavor. Advisory boards were increasingly

used at national, state, and local levels. Public meetings and hearings

became everyday components of field operations.

Congress was asked to settle disputes among land

users by specifying land uses but, more often than not, left the

decisions to land managing agencies (or the courts). Environmental litigation

seemed to become a way of life for BLM in the 1970s, as various interest

groups filed suit under the new acts.

Under Presidents Nixon and Carter, Congress was also

asked to reorganize the Interior Department—creating a Department

of the Environment and Natural Resources. In each proposal, the Forest

Service and other Agriculture Department agencies (e.g., the Soil

Conservation Service) would have been moved into the new Department;

under Carter's proposal BLM would have been remade in the Forest

Service's image. Neither effort was successful, but President Nixon was

successful in getting his fallback position accepted—the

Environmental Protection Agency was created in 1972.

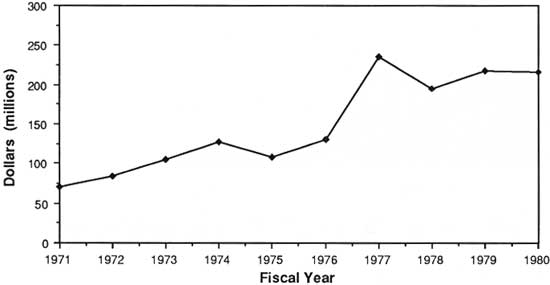

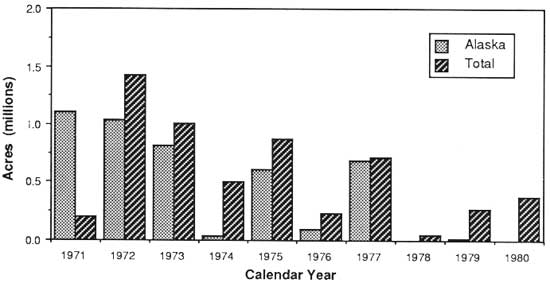

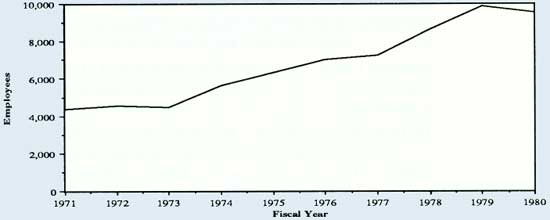

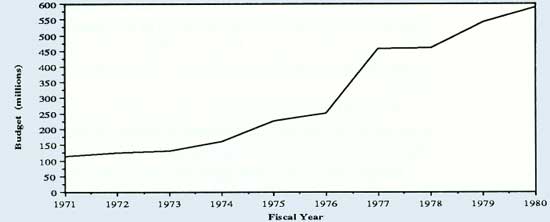

The number and type of employees in BLM increased as

the Bureau's environmental responsibilities increased. BLM's cultural

resources staff grew from one specialist at the Denver Service Center in

1970 to more than 120 (one in almost every field office) only 5

years later. Total employees in the Bureau rose from 4,300 in 1970 to

9,600 in 1980, while its budget increased from $118 million to $588

million.

In 1973, the nation was jolted by a major energy

crisis. While waiting in mile-long gas lines, millions of Americans

began to consider the nation's long-term energy needs. Although the

environmental movement never diminished in the public's consciousness,

its prominence soon gave way to concern over America's energy

future.

Despite passage of the Public Rangelands Improvement

Act in 1978, many of the Bureau's traditional constituents felt BLM had

bypassed them in a rush to embrace new public land users. The Sagebrush

Rebellion grew out of opposition to the federal government's enlarged

role in public land management. In 1979, the Nevada legislature passed a

resolution calling for state ownership of BLM public lands. Four other

western states soon passed similar legislation, but the movement quickly

dissipated with the election of Ronald Reagan to the presidency in

1980.

|

|

|

The 1970s were every bit as tumultuous—and

exciting—as the previous decade. Three new Directors served BLM

after Boyd Rasmussen: Burt Silcock (1971-73), Curt Berklund (1973-77), and

Frank Gregg (1978-81). Silcock, a career Bureau employee and Alaska

State Director from 1965 to 1971, was called upon by Secretary Walter

Hickel to handle critical Alaska issues in the early 1970s and to

continue Rasmussen's work in obtaining an "organic act" for the

Bureau.

|

|

New

Leadership |

|

Final passage of FLPMA was attained under Berklund,

who presided over a significant growth in BLM's management

responsibilities. BLM implemented a cultural resources program,

developed wilderness review procedures, and established new minerals

policies—all priority items during Berklund's

tenure—reflecting BLM's growth into a true multiple use agency.

Frank Gregg began the Bureau's implementation of

FLPMA, finalized new mineral leasing policies, and oversaw the

Bureau's efforts in securing passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands

Conservation Act of 1980.

|

|

|

A DIRECTOR'S PERSPECTIVE: 1971-1973

by Burt Silcock

Burt Silcock (Jennifer Reese)

|

Editor's Note: Burt Silcock rose through the ranks in BLM as a

range conservationist in Billings Montana in 1948, to Alaska State Director in 1965,

and Director in 1971. In 1973 he was appointed Federal Co-Chairman of the Joint

Federal-State Land Use Planning Commission for Alaska.

As I reflect back on my career, I don't believe there has

ever been such a "window of opportunity" as existed during the 50s-60s and early

70s. The atmosphere was ripe for growth, both for the Bureau and its

employees. Finally, America was beginning to recognize and acknowledge

the value of our public lands. I am extremely proud to have been involved in this period of history, and

cherish all the acquaintances of the dedicated men and women I worked

with who laid the groundwork for today's true multiple use

management.

Little did I realize, when I started with the Bureau

in 1948, where my career would lead me. I felt I had a solid grasp of

resource problems, and the BLM employees were a real asset. However,

with all the experience I brought with me, we still had a tremendous

challenge of continuing the course of good public land management.

When I became Director, the search for a national

land use policy concerning public lands was in full swing. The Public

Land Law Review Commission had completed its study and the

Classification and Multiple Use Act and the Public Sale Act had expired.

The President had submitted a reorganization plan to Congress to

establish a Department of Natural Resources and an Organic Act for the

Bureau. The BLM had developed a long-range land use planning system for

multiple use management of the public lands.

The challenges that we faced while I was Director

were signs of a changing nation. America's demand for use and enjoyment

of public land for recreation had reached an all-time high. Off-road

vehicles (ORVs) made it possible for users to reach heretofore

inaccessible areas. Cultural, archaeological and physical features of

the landscape were being destroyed by uncontrolled use. Facilities to

provide the basic need of sanitation were rarely available and our

enforcement capabilities for desert areas did not exist. We developed

regulations for the management and control of ORV use in accordance with

the Presidential Executive Order of 1972. This finally gave BLM the

tools to control and direct this growing program.

The need for clean sources of energy to meet the

nation's demands for growth and development focused on coal, oil shale,

and geothermal steam. This had a major impact on the Bureau's energy and

minerals programs and really tested our young planning system.

The Native Claims Settlement Act for Alaska, passed

by Congress in 1971, required the most massive redistribution of land

ownership in the history of the nation. The Act provided for a transfer

of approximately 44 million acres of land to private ownership and the

withdrawal of 80 million acres of federal land for parks, refuges and

national forests. The values of these lands were previously recognized by the Bureau of

Land Management's classification process in the late 1960s, when I was

the State Director in Alaska.

The uncontrolled use of the public lands by wild

horses and burros was in direct competition with domestic livestock and

wildlife. Attempts to control this use resulted in a controversy with

the wild horse sympathizers. The Wild Horse and Burro Act of 1971 was

passed by Congress to establish a policy for management of these animals

while providing them a legitimate place on the range. We developed

procedures to provide a program for management of these animals under

the Act and setup the Adoption Program. A National Wild Horse Advisory

Council was appointed to provide federal land managers with advice based

on their knowledge and experience on this highly visible public land

use.

Under our newly formed planning system, the Bureau's

Western Oregon Management Plan was implemented July 1, 1971. This plan

met the requirements of modern legislation dealing with air and water

quality, improving the environment, protection and enhancement of other

resources located on the timber sale contract areas, construction of

roads to higher standards, protection of scenic corridors along roads,

and limiting logging adjacent to recreational sites. This new plan

resulted in an annual sale reduction of 150 million board feet. This was

due in part to environmental considerations, the destructive 1962

windstorm and the Oxbow fire of 1966.

The Environmental Impact Statement process was

refined to meet the requirements of the National Environmental Policy

Act. We initiated programmatic environmental statements on broad program

areas of coal, oil shale, upland oil and gas leasing, timber harvest,

and management of domestic livestock.

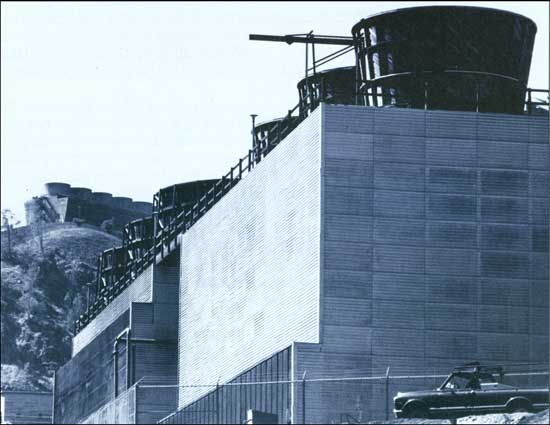

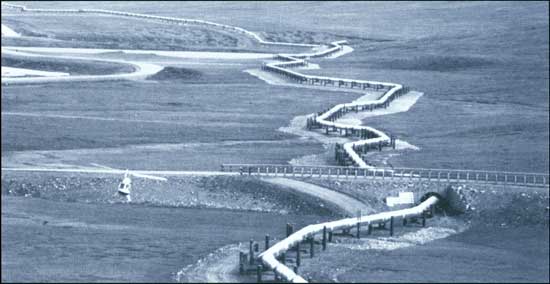

The proposed construction of the Alaska Pipeline was

a major project requiring the Bureau's workforce to develop

environmental and technical guidelines and monitoring for a safe

construction of the project. The Final EIS on the pipeline was completed

in March 1972. Environmental stipulations to manage construction of the

pipeline were far more stringent than any previously established. This

required extensive cooperation and coordination with industry, the State

of Alaska, and the federal agencies involved.

During this period of time we expanded the role of

Eastern States Office. It had been serving as a land office for many

years and the need for a full service office in that region of the

country was rapidly growing. This required a new State Director and

supporting staff.

I can't stress enough the admiration I had for the

BLM workforce then and now. Also, the relationship that existed between

my office and the Secretary of the Interior made for extremely pleasant

working conditions. I always felt that Secretary Rogers C.B. Morton and

Assistant Secretary Harrison Loesch would back us on tough decisions and

I have many examples where they stood right with us.

I'm still interested in public land management and

try to stay involved by volunteering for projects which I enjoy. It was

an interesting and sometimes hard ride from my early years in Billings,

Montana, but I feel fortunate to have had the opportunity to complete

the trip without getting bucked off.

|

|

|

NEPA: A NEW CONSCIOUSNESS

|

|

|

The same year Americans landed on the moon, Congress

passed the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA). Senator

Henry Jackson was instrumental in getting the act through Congress. In

the late 1960s, a symposium he organized recommended that Congress

establish a national policy on environmental quality. There was even

discussion on the Hill on whether Americans should have a constitutional

right to a clean environment.

Attesting to the strength of the environmental

movement, NEPA passed the Senate unanimously. President Nixon waited a

few days so he could sign the bill into law on January 1, 1970. Other

than placing environmental protection on a par with motherhood and apple

pie, few knew what the act would bring.

|

|

|

NEPA required federal agencies to consider the

potential impacts from proposed major actions and created the Council on

Environmental Quality (CEQ) to implement its provisions. According to

Ron Hofman, then acting Chief of the Division of Planning and

Environmental Coordination, the idea of environmental impact statements

(EISs) was added to the act at the last minute to provide an

"action-forcing mechanism" for agencies to (1) discuss their actions

with the public and with state and local governments, and (2) to

formulate management alternatives after extensive on-the-ground

evaluation.

|

|

Council on

Environmental

Quality |

|

Once draft statements were presented to the public

for review and comment, final statements were filed with CEQ. The

Interior Department established the Office of Environmental Project

Review to direct and approve EIS activities in the various bureaus.

Implementation of NEPA in BLM was assigned to Irving

Senzel, Assistant Director for Lands and Minerals. To handle this new

and rapidly growing workload, the Division of Program Development was

renamed the Division of Planning and Environmental Coordination

(P&EC). Under Hofman, the Division hired several new employees,

including a sociologist, an economist, and an environmental education

specialist, to review impacts on the "human" as well as the physical

environment. P&EC staffs were also established in State and District

Offices. For major projects, interdisciplinary EIS teams were set

up.

Lacking guidelines from CEQ and the Office of

Environmental Project Review, BLM first had to clarify what a "major

federal action" requiring an EIS was. The Bureau also needed to decide

when other kinds of environmental analyses would be appropriate. The

idea of doing environmental assessments (EAs) originated in BLM and was

later picked up by the Department and incorporated into CEQ guidelines.

P&EC issued a BLM Manual on NEPA requirements in 1971 that was used

as a model by other agencies.

|

|

|

IMPLEMENTING NEPA IN BLM

by Ron Hofman

Associate State Director, California State Office

Editor's Note: Ron Hofman was in charge of the

Division of Planning and Environmental Coordination in Washington when NEPA passed, and

continued in that post until 1976.

I guess it was a case of being in the right place at

the right time. In 1970, I was given the job of implementing NEPA, which came to have a dramatic

impact on the entire organization.

It seems like I had been preparing for NEPA during my

entire career in BLM. When I began as a forester in Colorado in 1958, we

didn't have a specialist for every program—so I had to learn about

the range program, wildlife issues, recreation, fire, soil and

watershed. BLM was really in the job of managing all these resources

together as systems. So when NEPA required us to look at the effects our

actions were having across the board, I and other land managers could relate

to that concept. The main issue was to fit this ecosystem approach into

the Bureau's customary narrow way of doing business, in the

program-by-program channels of BLM's policy, procedure, budget.

The answer to the program "blinders" problem was to

initiate an interdisciplinary approach to analysis and problem solving,

while preparing environmental impact statements or environmental

analysis documents. Here again the tendency was for specialists to

individually start these documents. We had to put together some fairly

specific training sessions, so after issuing BLM manuals on NEPA, my

staff and I visited each state to conduct this training. Its basic

premise was to assemble specialists on an interdisciplinary team, all

working together to conduct the analyses. The Bureau's policies and

procedures for conducting analysis of environmental impacts were among

the first to be formalized by federal agencies.

Another aspect of NEPA which I think the Bureau

responded very well to, was the requirement for looking at impacts on

the "human" environment. The Bureau understood that a lot of what we

did, especially in grazing, logging, and mineral development, would

continue to have a large impact on small western communities and their

cultures. It was with some pride that I hired the first sociologist in

the Bureau in 1972. It was also nice that she was a woman and that she

was black. Many more people from the social sciences were hired

throughout the Bureau to respond to NEPA, and these folks contributed to

the learning and capability of the organization. It was a major growth

step for us in understanding ourselves as a multiple-use agency.

There was a down side to implementing NEPA, though.

The legal challenges to projects forced agencies, including the Bureau,

to think in the defensive terms of legal adequacy of documents. This

took away from the initiative and motivation of the Bureau and weakened

our opportunity to build on our ecological skills. On balance, however,

NEPA was great for BLM. It started us thinking in ecosystem terms, using

interdisciplinary teams, adding social science skills, and enhancing

peoples' knowledge of the environment.

|

|

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION

by Ron Hofman

Associate State Director, California State Office

Earth Day Number One, April 22, 1970, was an exciting

time. Elementary schools, high schools, junior colleges, and

universities were calling us asking for speakers to talk about the

environment. How was it being threatened? What could the public do about

it?

Secretary Hickel established a Youth Task Force to

respond to questions and issues that young people were raising about the

quality of the environment. Linda Bemis in the Division of Planning and

Environmental Coordination was BLM's representative on the Task

Force.

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) passed

in response to an overwhelming national concern about the environment.

It had provisions for providing citizens with a better understanding of

the environment and how to protect it. This authority, together with the

demand from the public, gave BLM the opportunity to respond and serve

the public in a positive way.

Working with the Oregon State Office, we lined up two

college biology majors to draft a teachers guide which could be used at

the elementary school level. The idea was to provide teachers with

lesson plans which would get students to observe and learn about the

environment in the classroom and in the school yard. This draft,

finalized by Linda Bemis, was tested in the Charlottesville, Virginia,

school system with much success. Later, it was adopted as required

teaching material in the entire elementary school system in the State of

Pennsylvania. The final teachers guide was called "All Around You."

We also came up with the idea of using public lands

as "Environmental Study Areas." This was accomplished by getting some

district managers excited about the idea and then directing them to do

it in annual work plan directives. A DM would typically hire a local

6th-grade science teacher to work as a summer temporary, and using a

good BLM site near town, the teacher would develop a week-long

environmental science curriculum. Once the school year started, the

teacher would schedule sessions on the BLM site and use BLM specialists

to help teach.

Students learned a great deal about biology, about

the Bureau, and especially about the importance to their local community

of maintaining a healthy environment on the public lands. Among others

we established highly successful environmental study areas at Casper,

Boise, and Billings and were gratified at the recognition and positive

support BLM received from local communities.

The idea of an environmental education program

continued through the mid-1970s in BLM and the Forest Service. It was a

major advance for BLM because it caused the public to realize the

importance of the public lands and resources in the lives of people and

in western communities, and the importance of maintaining the health of

public land ecosystems. I am very proud of the Bureau's work in

environmental education. Perhaps in a different form and context, the

idea and the work remains out there in BLM today.

|

|

|

BLM also had to decide at what level of a program it

needed to do an EIS. Allotments, resource areas, districts, states,

regions, and nationwide programs were all considered. When BLM needed to

establish national policy, it wrote a programmatic EIS. For important

on-the-ground activities, field offices wrote EISs. BLM soon realized it

would need to prepare a "hierarchy of EISs," according to Hofman, at

different levels of the organization.

|

|

|

Oil and gas leasing statements were prepared at the

state level when decisions were reached to offer a certain number of

acres for lease. BLM, however, never knew how many wells would actually

be developed; it therefore prepared environmental assessments for each

site developed and imposed protective stipulations for sensitive areas.

For geothermal steam resources, BLM estimated field sizes, came up with

development scenarios, prepared an EIS, and then did EAs on actual

development.

|

|

Hierarchy of

EISs |

|

The range program started preparing a programmatic

EIS in 1972 to address Bureauwide range concerns and to establish

national policy for the program. BLM's coal program staff analyzed

impacts at a regional level when regional leasing decisions were reached

but wrote programmatic EISs to examine potential impacts of new federal

leasing policies (see Minerals).

Many in the environmental community found NEPA a

convenient tool for asserting their criticisms of BLM and used it in

attempts to modify BLM's management of the public lands. When BLM

completed its programmatic EIS on the range program, it was sued by the

Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) for not considering the impacts

of local actions by preparing local-level statements (see Range). If the

Bureau prepared local statements that were not grouped into a

programmatic EIS, it was also criticized.

BLM also reviewed EISs prepared by other agencies.

Its workload was often quite heavy because the Bureau had assembled a

wide variety of expertise to handle NEPA requirements. BLM learned a

painful lesson reviewing the Alaska Pipeline EIS. Several BLM reviewers

were critical of the statement, and word of the criticism was picked up

by columnist Jack Anderson. The Bureau soon learned if it could

criticize other agency EISs, it could expect the same in return! An era

of "politeness" soon developed in which BLM restricted EIS reviews to

areas it was directly responsible for.

|

|

|

Environmental education was one of the most positive

outgrowths of NEPA. The net result of NEPA on BLM, however, was to cause

it to consider its actions in a new light. Examining the cumulative

impacts of its actions fostered an ecosystem approach to land

management—and strengthened BLM's multiple use philosophy. While

other legislation focused on specific resources, NEPA asked land

managers to look at all of them together. Out of this developed an

interdisciplinary approach to solving problems. According to Ron Hofman,

NEPA put BLM's decisionmaking process into a "holistic context" by

having the Bureau consider ail resources equally.

|

|

Multiple Use

Concept

Strengthened |

|

In the early 1970s, funding to prepare EISs was only

slightly increased; BLM had to divert time and effort from other

activities to handle the increased EIS workload and to stipulate

mitigation of adverse impacts for actions that were approved. However,

it soon became clear that NEPA requirements had to be met. Thousands of day-to-day

actions—permits, leases, and licenses—depended on the

completion of environmental assessments and statements. BLM's program

work would have come to a stop if funding for NEPA work wasn't

increased. In the end it was, with Bureau appropriations almost doubling

(accounting for inflation) by 1980.

NEPA also had much to do with the increasing

diversity of BLM employees. Retired State Director Clair Whitlock

recalls that BLM's first "Cauldron"—a Bureauwide employee

orientation program held in Reno, Nevada—was attended by 60 to 70

people almost evenly split between range conservationists and foresters,

with only a few wildlife biologists and women represented. In 1976, two

sessions of the Cauldron were held; 56 occupational skills were

represented, including marine biologists and cultural resource

specialists, plus many more women and minorities.

|

|

Diversity of

BLM

Employees |

|

For the public, NEPA served to heighten awareness of

resource interrelationships in natural systems. According to natural

resources professor Sally K. Fairfax, NEPA became the "cornerstone" for

the environmental movement's participation in government decisionmaking.

But this participation was to be increasingly—and

unexpectedly—expressed through litigation. While NEPA had a

decidedly positive influence on BLM, according to Ron Hofman, "its use

as a legal playground took an edge off its grand vision."

|

|

|

THE FEDERAL LAND POLICY AND MANAGEMENT ACT OF 1976

|

|

|

FLPMA is a complex, detailed act that incorporated

provisions recommended by the Public Land Law Review Commission (PLLRC),

the Interior Department, and individual members of Congress. Getting

both houses of Congress to consider and pass an "organic act"

establishing policy for the management of BLM lands after PLLRC issued

its report in 1970 was a monumental undertaking. Bills were introduced

by the administration, the House, and the Senate in the 92nd, 93rd, and

94th Congresses. BLM employees had much to do with the eventual passage

of FLPMA, thanks to the continuing support of Directors Rasmussen,

Silcock, and Berklund, and of the Department under Secretaries Walter

Hickel and Rogers C.B. Morton.

|

|

|

Bureau employees played key roles in writing the

administration bill: Mike Harvey, Chief, Division of Legislation and

Regulation, and Eleanor Schwartz, who later took the job, drafted the

legislation and, with Associate Director George Turcott, "sold" it to the Department

and the Congress. Irving Senzel (Assistant Director, Legislation and

Plans) was the "brains" and editor-in-chief of the bill, according to Harvey,

while Bob Wolf (Assistant to Director Rasmussen) analyzed the PLLRC

report.

|

|

BLM

Employees

Play Key

Roles |

|

"My first job was to get and keep strong support from

the Department, the Office of Management and Budget, and the Council

on Environmental Quality, which in those days was a key player in the

administration. My second job was to get and keep strong support from

Congress," said Harvey, who left BLM in 1973 to take a job with Senator

Jackson, Chairman of the Interior Affairs Committee.

|

|

|

BLM'S RESPONSE TO THE PUBLIC LAND LAW REVIEW COMMISSION'S REPORT

by Mike Harvey

Editor's Note: Mike Harvey began his career with

BLM in 1960. After receiving a law degree from Georgetown University,

he became a staffer for the Public Land Law Review Commission. Harvey

returned to BLM in 1968 as Chief, Division of Legislation and Regulation,

and in 1973 became Chief Counsel for the Senate's Committee on Energy

and Natural Resources.

On June 20, 1970 the Public Land Law Review Commission

(PLLRC) presented its long-awaited report to President Nixon. This

event triggered a response by BLM that led directly to another long-awaited

event: enactment of an "Organic Act" for the public lands administered by

BLM, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA).

All of us in BLM knew the PLLRC study (originally

due in 1968) had been used as an excuse to delay much needed modernization

of the public land management mission and authority of BLM. While the

Report, containing over 300 recommendations, covered all federal lands,

its greatest significance was for BLM. Other agencies had clear statutory

mandates. BLM was the primary target of the Report and everyone knew it.

We wanted a rapid and reasonable response so no one

could speculate about or misunderstand BLM's views on the issues. Our

response also had to be factual and analytical so BLM could establish

the basic legislative parameters that would gain secretarial and

presidential approval and significant public and congressional support.

By July 8 we had critiqued the Report and by July 17

we submitted our initial analysis to the Secretary. Within the next 5

months the Bureau prepared a 250-page detailed analysis, but our initial

analysis identified the major themes and principles we thought should be

adopted. At the same time, BLM was implementing the decision by

Secretary Hickel and Assistant Secretary Loesch to being modernizing

public land laws and regulations.

On July 2, 1970 the Director stated, "This work is

obviously of utmost importance to the future management of the public

lands and resources administered by BLM. It must be given a very high

priority..." Only July 20, 1971, the National Resource Lands Management

Act was submitted to Congress. Secretary Morton did not exaggerate when

he told Congress, "This bill represents an historic proposal. The

Department is proposing legislation which, for the first time, would

state the national policies governing the use and management of 450 million

acres of the public domain..."

Three of us put both efforts together: Irving Senzel,

Assistant Director Legislation and Plans; Bob Wolf, Assistant to the

Director; and me. First we needed strong support from the Department,

OMB, and the Council on Environmental Quality, a key player in the

Administration. Second, we needed strong support from Congress. With

extraordinary support from Secretaries Hickel and Morton and Assistant

Secretary Loesch, the first task was relatively easy. The administration's

1971 proposal was the product. The second task took 5 more years and I

had to leave BLM and go to the "Hill" to get it done. The final

congressional action approving FLPMA—Senate passage of the

Senate-House Conference Report—came on my 42nd birthday: October

1, 1976. What a birthday present!

|

|

|

The administration's bill, the "National Resource

Lands Management Act," was introduced in the

Senate in 1971. This bill focused exclusively on

BLM, requiring it to inventory public

land resources, giving priority to areas of critical environmental

concern (ACECs). The bill was not considered by the full Senate and was

reintroduced in the 93rd Congress. The Senate declined to consider it,

instead passing a bill introduced by Senator Henry Jackson. The House

took no action on either bill.

|

|

Administration

Bill |

|

Jackson's bill was reintroduced in the Senate in the

94th Congress. It differed from the administration's bill "sometimes

with only subtle changes or differences in emphasis," according to

Schwartz. Like the administration bill, it authorized management of

BLM's national resource lands under the principles of multiple use and

sustained yield, and called for a return of fair market value to the

government for the use and sale of its lands.

|

|

|

Jackson's bill contained provisions on inventory,

planning, public participation and advisory boards;

authorities for law enforcement; and

provisions for sales, exchanges, and acquisitions

of land. The bill called for

a working capital fund to be established in BLM and for a land use plan

to be completed on the California Desert. It also

contained amendments to the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 to increase the

percentage of revenues paid to the states, provisions for mineral impact

relief loans and oil shale revenues, and requirements for the

recordation of mining claims. This bill finally passed the Senate on

February 25, 1976.

|

|

Senator

Jackson's

Bill |

|

The House of Representatives took a different

approach. In 1972 the House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee drafted

a bill, the "National Land Policy, Planning, and Management Act,"

incorporating many of PLLRC's recommendations. The bill proposed uniform

land use planning and management activities for all

federal land managing agencies but was not reported out of committee in time to be

considered by the full House.

|

|

House Bills |

|

In its next session, Congressman Wayne Aspinall was

absent, having lost a primary election. Under Representative John

Melcher of Montana, the Subcommittee on Public Lands rewrote the House's

legislation, following a lengthy series of meetings (about 68 in all) to

discuss public land issues. A bill was not completed in time to be considered by

the full House in the 93rd Congress, but was introduced in its next

session.

The "Federal Land Policy and Management Act" was

similar to Senator Jackson's bill but had provisions relating to both

BLM and Forest Service lands regarding grazing fee formulas, leases and

permits, advisory boards, and wild horses and burros. The bill also

created the California Desert Conservation Area and granted the Bureau

law enforcement authority.

By this time, Tim Monroe succeeded Irving Senzel as

Assistant Director for Legislation and Plans and, under Director Curt

Berklund, continued the Bureau's work with the Hill to clarify questions

on BLM's management activities and legislative needs for the public

lands.

|

|

|

HOW FLPMA PASSED

by Eleanor R. Schwartz

Division of Legislation and Regulatory Management

By August 1976, a comprehensive act relating to the

management of public lands had been passed by each house of Congress.

The Senate disagreed to amendments made by the House and requested a

conference. Conferees were appointed and Congressman Melcher was elected

chairman. Because many primaries had been scheduled for early September,

the first meeting of the conferees could not be held until September

15.

The first difference addressed by the conferees was

the title of the Act. The House called it the Federal Land Policy and

Management Act of 1976, while the Senate called it the National Resource

Lands Management Act. The Senate conferees deferred to the House on the

title and on the term to be used for BLM lands—public

lands—although they felt it was a confusing term.

And so it went. The conferees met four times between

September 15 and 22. Most issues were resolved rather easily but four

issues proved so difficult that they almost killed the bill. The Senate

conferees objected to the House provisions on grazing fee formulas,

10-year grazing permits, advisory boards and permits, and wanted a

requirement that mining claimants apply for patent within 10 years of

recording claims. The House conferees objected to that.

Before the end of a 5-hour session on September 22,

Senator Metcalf of Montana offered a compromise package in which grazing

fee provisions were deleted, all grazing leases would be for 10 years,

grazing advisory board functions would be limited to recommendations for

expenditure of range improvement funds, and the Senate language on

mining claims would be applicable only to claims filed after enactment

of the Act, not to pre-existing claims.

The conferees could not agree on the package that day

but agreed to meet again on September 23rd, just in advance of the conference on the

National Forest Management Act of 1976. Substitute compromises were offered by a House and

Senate conferee but both were rejected. Chairman Melcher adjourned the conference saying he

saw no point in prolonging the meeting. At that time, hopes for the enactment of a

land management act for BLM were dim.

The 94th Congress was in its last-minute rush before

adjournment. But as with many pieces of landmark legislation, a

compromise was reached at the eleventh hour. On September 28th

Congressman Melcher made a final effort to reach a compromise. He called

a meeting for 5:30 p.m. that evening. Very few persons, other than

conferees and staff, were permitted in the conference room. Within a few

minutes of coming together, the conferees took a break. Word spread

among the many persons filling the corridors that the meeting was going

badly. However, when the conferees reassembled at 7:00 p.m., those

present voted almost immediately for the compromise suggested

earlier.

In keeping with its somewhat stormy and cliff-hanger

history, the conference report was passed by the House on September 30th

and by the Senate on October 1st, just hours before the 94th session

ended. The Act was signed by the President on October 21, 1976.

|

|

THE FLPMA TIGHTROPE

by George Turcott

Editor's Note: BLM put a great deal of effort into

getting an "organic act." Former Associate Director George Turcott has another

perspective to tell in getting FLPMA passed. Mr. Turcott began working for BLM as a range

conservationist in Elko, Nevada, in 1950. He served as a district manager in Canon City, Colorado,

and Chief, Resource Management in Montana before moving to Washington in 1964. Mr.

Turcott was Associate Director from 1972 to 1979.

During the waning weeks of the 94th Congress,

senators, representatives, and committee staffs worked to fashion a

compromise acceptable to both Houses. The final hurdle, a point on

grazing fees, came late one afternoon. The conferees couldn't rewrite

the language or make compromises, even though some of the other

compromises in the bill were contradictory. The final vote called by

the joint chairman of the conference came out a tie, which in the

legislative process is non-passage—you have to have a majority of

both the Senate and House conferees voting in favor of the

compromise.

Irving Senzel, Eleanor Schwartz, and I had been

working on the Hill with Mike Harvey trying to work out language with

these people and explain the effects of different languages they

substituted in committee. I think the lowest point in my life—or my

whole career—was the day FLPMA hadn't passed.

BLM put everything it had into getting this act. Many

of us oldtimers in the Bureau said that before we retired we wanted a

basic organic act—and not all this crossword puzzle kind of stuff

we'd had to work with for 30 years.

So here we were with six years' effort apparently

down the drain. I waited until early evening and called up Senator

Metcalf, the co-chairman of the conference for the Senate, and asked if

there was anything we could do on the grazing fee issue, where he could

call everybody back together again to make one more effort. He said no:

"all the procedures are past, George, we lost."

Senator Metcalf was very much in favor of passage, so

I tried one more angle with him. I said, "well can we work some language

in there about some studies and a report back again?" Doing studies was,

and is, a common legitimizing technique—it affirmed we'd still

consider certain things, such as fair market value and the points

stockman were making as to cost of production and so forth. I finally

pleaded "just do it for me. Make one more try." He did. And, lo and

behold, that night we got one more vote—the one vote we needed—and

that's how we got FLPMA and the study on grazing fees.

FLPMA was expanded tremendously from the original

draft as it developed to the final. Section after section of it is as

detailed as a regulation or a Bureau manual procedure—and that's

detailed. I think it's a natural result of the pulling and tugging that

occurred in the Public Land Law Review Commission, of saying something

about one resource and at the same time providing counterbalances in

other areas of the act. It's a very detailed, difficult act and had to

undergo clarification by later Congresses.

|

|

|

The House and Senate reconciled their bills only at

the last minute in 1976, as described by Eleanor Schwartz and Associate

Director George Turcott. FLPMA's major provisions are as follows:

|

|

|

Congressional Review of Land Withdrawals—While

FLPMA provided for the continuation of all classifications and

withdrawals made under the Classification and Multiple Use Act, Section

202 also required BLM to review these actions when preparing new land

use plans. Congress was empowered to review sales of land in excess of

2,500 acres or withdrawals of tracts over 5,000 acres, as well as

decisions on principal uses of lands in areas greater than 100,000

acres.

|

|

Major

Provisions of

FLPMA |

|

By the end of the decade, BLM had taken little action

on reviewing existing withdrawals or classifications; it was preparing

an inventory of these actions and implementing new land use plans

(Resource Management Plans) in the field. Prior to FLPMA, 67 million

acres of the public lands had been formally withdrawn from the public

domain, including land for BLM and Forest Service recreation sites, land

adjacent to National Parks, land to protect watersheds, and land for

Forest Service roadside zones. Under the CMU Act, BLM had also

classified more than 150 million acres of its own lands in the lower 48

states for retention, plus an additional 32 million acres in Alaska.

Recreation and Public Purposes Act

Amendments—FLPMA amended the R&PP Act to increase the land BLM

could sell or lease to state and local governments, and it required

public participation in all decisions to dispose of lands under the

act.

Law Enforcement—FLPMA authorized BLM to hire a

force of uniformed rangers in the California Desert, but required the

Bureau to rely on local officials as much as possible through

cooperative agreements with local enforcement agencies.

Finance and Budget—FLPMA provided BLM with

long-needed authorities that made its work more efficient. FLPMA

established BLM's Working Capital Fund. It also allowed BLM to accept

contributions and donations for specific activities on BLM lands (e.g.,

wildlife habitat improvements or recreation developments) and allowed

BLM to establish service charges for applications and documents.

Land Exchanges and Acquisitions—FLPMA provided

for cash payments from the government to equalize values of exchanged

lands. It also gave BLM authority for acquisition under its land use

plans but limited the government's power of eminent domain. BLM was

allowed to use Land and Water Conservation funds to acquire public

recreation lands.

Special Management Areas—Section 202 of FLPMA

authorized BLM to identify areas of critical environmental concern

(ACECs) through its planning process. ACECs were defined as areas

"within the public lands where special management attention is required"

to protect "historic, cultural or scenic areas, fish and wildlife

resources, or other natural systems or processes...."

Livestock Grazing—FLPMA authorized a study of

grazing fees but prohibited any increase in the fee in 1977. To assure

long-term stability and use of BLM lands by the livestock industry, it

also authorized 10-year grazing permits and required 2-year notices of

cancellation. BLM grazing advisory boards were directed to advise BLM on

the development of Allotment Management Plans and the allocation of

range improvement funds.

|

|

|

A DIRECTOR'S PERSPECTIVE: 1973-1977

by Curt Berklund

Curt Berklund (Jennifer Reese)

|

Editor's Note: Dr. Curt Berklund was retired

when he came to Washington early in 1970. He is again retired, living

in Spokane, Washington, working the financial markets and managing a

private foundation he set up to fund, among other things, scholarships

in resource management at the University of Idaho. And he still uses

a sharp eye and quick reflexes to participate in trap shooting

competitions.

The year 1973 was a threshold year for the Bureau.

Many changes were in the wind as the nation grappled with the conflicts

of Watergate and a mid-East oil embargo. As a staff assistant and

Deputy Assistant Secretary in the office of Assistant Secretary Harrison

Loesch, I had been involved with Bureau policy development and

observed the need for administrative change. When I assumed the

Director's job in July 1973, one of my first actions was to leave

Washington and meet with the State Directors. I had the highest

confidence in the State Directors and the field structure. They

needed leadership from Washington and the opportunity to carry out

the programs and be supported, not second-guessed or "rolled." The

State Directors needed someone who treated them candidly with respect.

The Bureau had few trusted constituencies. Strong

political support was needed to build a record as a professional

natural resource agency that would manage the programs on-the-ground

in the full multiple-use context. One of my desires was to establish

a way of building our credibility outside the government and have groups

and key individuals we could count on. We went to work with state and

county governments through the Western Governors and the National

Association of Counties to help build a constituency among those who

were closest to the everyday decisions BLM managers were making. Over

the years, this effort really paid dividends. We also worked on

improving our relationships with the news media.

One of the more important tasks to begin building

credibility with Congress. We organized the Bureau's first formal,

well-staffed, Congressional liasison organization; trained the people;

and gave them support and information necessary to deal effectively

with Congress. I also spent countless hours working with key members

of the Senate and House of Representatives to assure that BLM's message

was presented from a foundation of professionalism in natural resource

management. Former Members such as Julia Butler Hansen, Alan Bible,

and Wayne Aspinall, already supportive of the Bureau's mission, needed

a source of credible information. During my tenure as Director, we

effectively tripled the Bureau's budget and added skills to district

and resource area offices that were unheard of in the 1960s. I was

adamant during this period of growth that the Washington Office would

not siphon off the increased positions and budget dollars. We stayed

lean and efficient. I split energy mineral programs from the renewable

resource programs in order to give better leadership to both. This

resulted in giving our offshore and onshore leasing programs more

visibility and effectiveness. We leased more acreage (OCS and public

domain) for oil and gas exploration than had been leased previously.

We cleared lots of hurdles in setting up a geothermal leasing program,

and today a considerable amount of electricity is generated in

the West from that source.

Delegating the authority and responsibility to the

field comes to mind as one of my most notable achievements. I felt that

if the field organization had leadership, authority, and support from

Washington it would give confidence to the field managers that they were

in charge and were accountable for their program assignments. Then, they

would make their decisions with knowledge that Washington wouldn't cave

in to some real or perceived political challenge and "roll" the

decisions. This also helped the Washington staff realize their role was

to develop policies and procedures and evaluate the field manager's

performance, not dictate how the field should operate.

We won control over our NEPA implementation processes

in the Bureau previously centralized in the Secretary's office. We

accomplished it only because the professionals in the Bureau were given

the responsibility to show we could write, edit, and review our own

environmental documents. That road was rocky at times but the superb

help from countless individuals allowed us to internalize the program

and make it work as part of the overall decision process.

We worked very hard to secure approval of an "organic

act" for the Bureau. Trying to administer programs governed by over

3,000 land laws was virtually impossible. The task divided us and did

not generate the constituent support we needed. We received special

dispensation from the Department and the administration to work out the

legislation, because I had chaired the Department's committee to review

the Public Land Law Review Commission's report and make recommendations

for implementation. Former Secretary Tom Kleppe was instrumental in

providing BLM the support we needed to cut the deals and work out the

language we felt was required to formulate the legislation. We fought

hard on key issues such as wilderness review, law enforcement authority,

the California Desert National Conservation Area and administrative

provisions needed to streamline our approach to multiple-use

management. I personally opposed making the Director a presidential

appointee; however, we were able to legislate some level of protection

for the career ranks. I established the organization to implement FLPMA

and implementation began while I was still Director. We set up a

multi-disciplinary committee of Washington managers and staff and made

considerable progress in setting out basic guidelines.

One of our additional achievements was securing

congressional approval of the Payments In Lieu of Taxes legislation.

Recognized as truly "good neighbor" legislation, this helped to reduce

much of the friction with local governments in the West. We modified the

Alaska pipeline environmental statement and secured approval for the

construction permits.

We started a record search through the Eastern States

Office to identify federal coal resources in the Appalachian Region. We

were losing federal coal simply because the records were inaccurate.

This program prevented more serious criticism of the Bureau by Congress

and others because we identified the problem and sought solutions.

As I look back beyond the dozen years or so since I

had close association with the Bureau, I appreciated the opportunity to

have served. I made some close friends and learned much. While my

association with BLM is fairly limited, I still keep in touch with a few

friends and welcome calls at any time.

|

|

|

Wilderness—Section 602 of FLPMA directed BLM to

review the public lands for wilderness potential as set forth in the

1964 Wilderness Act. The act also directed BLM to conduct early

wilderness reviews on all lands designated as primitive or natural areas

before November 1, 1975.

Wild Horses and Burros—FLPMA amended the Wild

and Free Roaming Horse and Burro Act to authorize the use of helicopters

in horse and burro roundups. Wild horse and burro populations had more

than tripled since passage of the Wild and Free Roaming Horse and Burro

Act in 1971—horse numbers on BLM lands in the West were estimated

at more than 60,000, compared to 17,000 in the late 1960s.

Minerals Management—FLPMA modified the formulas

for distribution of funds collected under the Mineral Leasing Act of

1920 and the Geothermal Steam Act of 1970. It also required persons

holding claims under the General Mining Law of 1872 to record their

claims with BLM within three years. FLPMA authorized loans to state and

local governments to relieve social and economic impacts of mineral

development and directed the Secretary to develop stipulations that

would prevent unnecessary or undue degradation of the land.

|

|

|

|

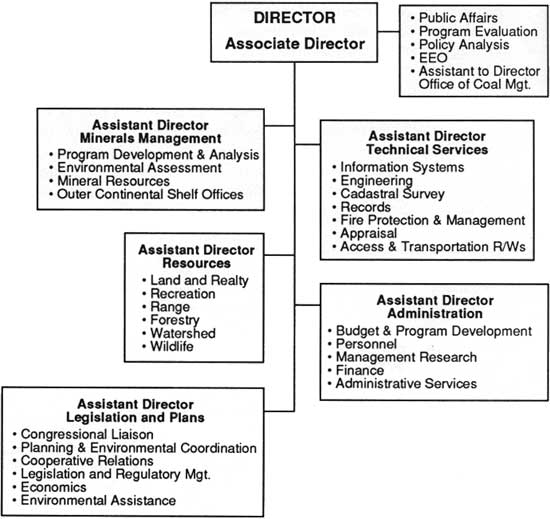

BLM organizational structure in 1977

|

|

|

Other Provisions—FLPMA established the

California Desert Conservation Area and directed BLM to develop a land

allocation plan for the area by 1980. FLPMA also repealed the Homestead

Act (except in Alaska where it was given a 10-year life) and other

settlement acts. The act also decided how future directors of BLM would

be selected—by the president, with approval from the Senate.

|

|

|

PLANNING

|

|

|

In the 1970s, systematic land use planning was

implemented in the field. Management Framework Plans (MFPs) were

prepared for 80 to 85 percent of BLM lands in the lower 48 states by

1976. Data from resource inventories was considered with economic and

social information to develop and compare management alternatives. After

holding a series of public meetings, BLM Resource Areas revised and

finalized the MFPs, and implemented them as management tools.

Ironically, NEPA had much to do with the demise of

BLM's first successful, Bureauwide planning system. Court decisions had

made EISs the Bureau's primary tool for analyzing resources, impacts,

and management alternatives on the ground—especially for BLM's

range activities. MFPs were becoming duplicative. Also, Section 202 of

FLPMA required BLM to develop a more comprehensive land use planning

system for "developing, displaying, and assessing" management

alternatives; it also directed the Bureau to strengthen its coordination

with state and local governments.

Therefore, starting in 1977, BLM began developing

Resource Management Plans (RMPs), which were to be prepared in the field

in conjunction with Environmental Impact Statements. In 1979, BLM phased

in a transition from MFPs to RMPs, whereby scheduled updates of MFPs

would be replaced by RMPs. By 1988, 61 RMPs were completed

Bureauwide—about half of the RMPs that will eventually be prepared.

The Bureau has scheduled replacement of all its MFPs by 1994.

The basic steps in completing an Resource Management

Plan are:

1. Develop public participation plan.

2. Identify issues.

3. Develop planning criteria (set standards for data

collection and formulation of management alternatives).

4. Gather information, inventory resources.

5. Analyze management situation.

6. Formulate management alternatives.

7. Estimate effects of alternatives.

8. Select preferred alternative.

9. Publish draft RMP/EIS (90-day comment period).

10. Publish final RMP/EIS (30-day protest period).

11. Monitor and evaluate overall plan.

12. Prepare activity plans.

|

|

|

FROM MFPs TO RMPs

by Robert A. Jones

Editor's Note: Bob Jones began his career with BLM in

1953. After holding lands and realty positions in Montana and the

Washington Office, he became Chief Office of Program Development—later

the Division of Planning and Environmental Coordination.

Bob Jones and his staff developed and implemented BLM's land use

planning system in the 1960s and 1970s. Indeed, Bob Jones was the

Bureau's planning system until his retirement in 1981.

One of the most interesting periods in the history of

BLM's planning program was the change from Management Framework Plans

(MFPs) to Resource Management Plans (RMPs). This is how it happened. The

Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) requires land use plans

as a basis for public land decisions. It also requires the Department to

publish regulations specifying how these plans are to be prepared. BLM

initially felt that MFPs would meet requirements of FLPMA.

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requires

federal agencies to analyze and consider environmental impacts of all

major federal actions, and to prepare and publish Environmental Impact

Statements (EISs) when these actions significantly affect the environment.

These EISs are then filed with the Council on Environmental

Quality (CEQ). The Departmental Office of Environmental Project Review

(OEPR) directed NEPA implementation in Interior. OEPR exercised the

Secretary's authority to approve and file EISs, and was heavily involved

in the EIS process. They often specified alternatives to be analyzed and

the level of analysis. The bureaus could not approve and file EISs even

when they had authority and responsibility for the decisions involved.

These overlapping responsibilities created much tension between OEPR and

BLM.

While there was much pressure on BLM to file EISs for

proposed MFP approvals, no BLM director wanted to invite the OEPR

involvement that would follow. Instead, BLM held that where

implementation of features of many MFPs constituted a major federal

action, one EIS would be prepared to analyze the cumulative

environmental impact. We used this approach for the grazing EISs

required by a court judgment, and it worked, as far as NEPA compliance

was concerned. However, livestock grazing is widespread and influences

most public land decisions. As a result, since the grazing EIS process

was so much better publicized and drew so much wider public attention

than MFP preparation, it was, by default, assuming a major portion of

the multiple use planning role.

In mid-1977, Director Frank Gregg decided that

compliance with FLPMA required substantially upgrading the MFP process,

and that BLM should coordinate with the Forest Service, which at that

time, was revising its multiple-use planning process. We hoped to

reestablish the resource allocation decision process in the multiple-use

plan as required by FLPMA, break OEPR's hold on EIS filing authority,

and substantially upgrade the planning system to meet the needs of the

1980s, all at one time by using the same basic planning components being

developed by the Forest Service. The details would, of course, differ to

accommodate BLM needs. BLM called its product the Resource Management

Plan (RMP). The big gamble was whether RMP/EIS filing authority would be

delegated to BLM. OEPR was strongly opposed. We won! In 1979 filing

authority was delegated by Secretary Andrus thru regulations he approved

which launched the Resource Management Planning process.

|

|

|

Public meetings conducted by the employees developing

the plan are required during issue identification, development of

planning criteria, and publication of both the draft and final RMP/EIS.

Once the RMP is approved, BLM prepares more specific activity plans for

specific programs (e.g., Allotment Management Plans, Habitat Management

Plans, or others); the activities proposed in these plans must conform

to the RMP. For actions that don't, the District Manager prepares a plan

amendment, again with participation from the public.

|

|

|

MINERAL

|

|

|

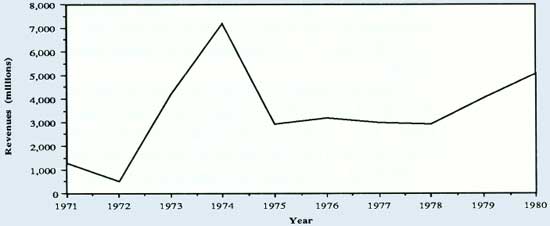

Mineral policy in the 1970s was largely influenced by

the Arab oil embargo. In 1973, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting

Countries (OPEC) imposed a four-fold increase in the price of oil, and

in response to the Yom Kippur War, several countries placed an embargo

on oil exports to the United States. This action, combined with an

increased reliance on automobiles for personal transportation by the

public, created the infamous gas lines of 1973. The nation's dependency

on foreign oil had risen to 36 percent, with 10 percent coming from Arab

countries.

|

|

| Outer Continental Shelf (OCS)

Mineral Leasing Statistics 1971-1981 |

Fiscal

Year |

Gulf Coast |

West Coast |

Atlantic Coast |

Alaska |

Active

Leases |

Acres

(millions) |

Active

Leases |

Acres

(millions) |

Active

Leases |

Acres (millions) |

Active

Leases |

Acres

(millions) |

| 1971 | 1010 |

4.27 | 70 |

.36 | — |

— | — |

— |

| 1972 | 965 |

4.01 | 70 |

.36 | — |

— | — |

— |

| 1973 | 1027 |

4.33 | 69 |

.35 | — |

— | — |

— |

| 1974 | 1258 |

5.59 | 69 |

.35 | — |

— | — |

— |

| 1975 | 1607 |

7.41 | 68 |

.35 | — |

— | — |

— |

| 1976 | 1678 |

7.75 | 124 |

.66 | 93 |

.53 | 76 |

.41 |

| 1977 | 1794 |

8.67 | 121 |

.64 | 93 |

.53 | 76 |

.41 |

| 1978 | 1703 |

7.81 | 108 |

.58 | 136 |

.77 | 163 |

.90 |

| 1979 | 1757 |

8.09 | 148 |

.79 | 175 |

1.00 | 131 |

.73 |

| 1980 | 1688 |

7.70 | 142 |

.76 | 232 |

1.32 | 113 |

.57 |

| 1981 | 1941 |

8.84 | 273 |

1.55 | 128 |

.68 | 150 |

.79 |

|

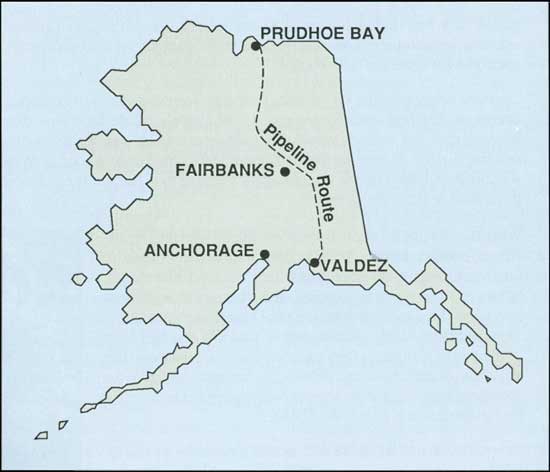

ALASKA'S OUTER CONTINENTAL SHELF

OFFICE

by Edward J. Hoffmann

Manager, Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Office (1973-1978) - Retired

On a hot summer day in 1973 a cryptic message reached

me in the Arizona State Office from Ed Hastey approving my reassignment

to Anchorage as head of a newly established Alaska Outer Continental

Shelf Office. After spending a decade in Alaska in the '50s and early

'60s, the opportunity was most welcome.

The initial charge was to assemble a small

multi-disciplinary team to begin assessing the probable environmental

impacts of exploratory oil and gas drilling in federal waters off

Alaska. The Arab oil embargo and the administration's ensuing Project

Independence quickly changed the mission to a full-blown effort with

responsibilities ranging from environmental assessment to actual leasing

of offshore tracts for exploratory drilling.

This unique program required specialists with unique

disciplines—oceanographers (chemical, physical, geologic,

biologic), paralegals, petroleum engineers, economists, computer types,

geographers. There were also some garden-variety

skills—administrative types, natural resource specialists and the

all important clerical positions.

The first Alaska Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) sale

was conducted for tracts in the Northern Gulf of Alaska on April 13,

1976. Preparations for the sale surfaced major objections from state

government and Native (Indian) groups. There was a good bit of

give-and-take before the sale came to being—accommodations were

made on both sides. About $1.75 billion was offered in bids, with

accepted bids netting $571,900,000 to the Treasury. Disappointingly, no

discoveries were made during exploratory drilling. The staff received a

unit citation from the Secretary of the Interior for the excellent work

done in bringing to reality the first sale in a frontier area.

The second and final sale of my tenure was in Lower

Cook Inlet. It netted over $211 million in bonus bids to the Treasury.

Again, no commercial discoveries resulted from exploratory drilling.

As my tenure began winding down, we were negotiating

with the State of Alaska to hold a joint state-federal sale in the

Beaufort Sea off Prudhoe Bay. These negotiations were complex, involving

disputed ownership of the seabed. The Eskimos were greatly concerned

that any further industrialization of their areas would adversely affect

their subsistence way of life. Finally, an agreement was reached and the

sale consummated well after my retirement in August 1978.

The OCS offices, while within BLM, were unique in

that they were responsible to the director rather than a state director.

Since the programs were highly visible, politically sensitive, and

controversial, the Office of the Secretary took a more than casual

interest. The OCS offices eventually were transferred to Minerals

Management Service.

In retrospect, the 5 years I spent as Manager of the

Alaska OCS office were the highlight of a varied career spanning over

three decades. It was especially gratifying to have had the opportunity

to gather a highly motivated crew from a wide variety of disciplines in

an interesting and controversial program.

|

|

|

President Nixon reacted to the situation by

announcing Project Independence on November 7, 1973. The project called

for making the U.S. self-sufficient in energy by 1980. Development of

federal mineral reserves were an important part of this equation.

Nixon's policy was followed by succeeding presidents.

|

|

|

Mineral leasing increased dramatically in response to

the embargo. Drilling and production were up all over the nation,

in the East as well as the West. Mineral development was further spurred by

Congressional tax cuts for the domestic petroleum industry. BLM began

leasing Outer Continental Shelf lands off Alaska and the mid-Atlantic states in

1976. By 1980, the Bureau administered 113 leases for 570,000 offshore

acres in Alaska and 232 leases covering 1.3 million acres off the

Atlantic Coast.

|

|

Increase in

Mineral

Leasing |

| Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Mineral Leasing

Statistics 1971-1981 |

Fiscal

Year |

Total Production |

Natural Gas

(1,000 cu. ft.) |

Petroleum

(million bbl) |

| 1971 | 2,620.2 | 403.4 |

| 1972 | 2,893.3 | 419.6 |

| 1973 | 3,042.4 | 394.9 |

| 1974 | 3,548.1 | 391.9 |

| 1975 | 3,382.6 | 339.3 |

| 1976 | 3,492.6 | 322.8 |

| 1977 | 3,652.7 | 301.6 |

| 1978 | 4,251.7 | 291.6 |

| 1979 | 4,628.3 | 290.1 |

| 1980 | 4,707.3 | 284.6 |

| 1981 | 4,879.2 | 283.9 |

|

|

The problem of speculation in oil and gas leasing

soon reappeared. Private filing companies told the public they could

strike it rich in the federal oil and gas "lottery" (the simultaneous

oil and gas noncompetitive leasing program, or SIMO) for a small fee.

While BLM was charging $10 for SIMO applications, filing companies

charged up to $100, and, for the vast majority of noncompetitive lease

holders, chances were quite good that they would not realize any profits

from their risks.

|

|

|

A 1970 Bureau study found that federal coal was being

leased at a fast pace, but that little production was occurring. Coal

reserves were being tied up with few royalties coming into the U.S. Treasury.

In response, Secretary Rogers C.B. Morton stopped BLM from issuing coal

leases and prospecting permits in May 1971.

|

|

Coal |

|

In February 1973, the Department announced BLM was

developing a new coal policy for the nation. A year later, the

Energy Mineral Allocation Recommendation System (EMARS) was

announced. The policy called for BLM to determine the rate at which

federal coal should enter the market, select sites where good quality coal (and good land

rehabilitation) could be had, and only then determine a leasing schedule.

|

|

New Coal

Policy |

|

EMARS was spelled out in BLM's draft programmatic EIS

for coal. Both the EIS and EMARS were criticized in 1974 as

being too general, and Interior withdrew the proposed policy. By 1975, the

Department drafted and released the Energy Minerals Activity

Recommendation System (EMARS II).

EMARS II emphasized market planning; it was designed

to set up regulations and incentives that would, according to William

Moffat of the Department's Office of Policy Analysis, "lead industry,

acting in its own interest, to do what we think the nation needs." This

plan called for leasing coal by competitive bid at no less than fair

market value. The intent of the policy was to lease only those lands

that needed to be leased; it was supposed to halt speculation by

enforcing the diligent development provision of the Mineral Leasing Act

of 1920.

The programmatic EIS issued with the release of EMARS

II, however, was attacked by environmental groups as being of poor

quality—so poor as to "preclude meaningful comments" according to

the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). NRDC subsequently

threatened to sue. It had recently won its challenge to BLM's grazing

EIS, but Interior decided to proceed with EMARS II. NRDC sued the

Department and won in 1977. The District of Columbia District Court

ruled that BLM's EIS was inadequate and stipulated how this was to be

corrected—largely through a new EIS that would incorporate

additional comments from the public.

|

|

|

By this time several other things had happened. The

Coal Leasing Amendment Act of 1976 set a federal royalty rate for

coal at 12-1/2 percent on leases issued after mid-1976

(prior to this, rates were inconsistently set).

It also abolished preference right

leasing, which had been authorized under

the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 in

cases "where prospecting or exploratory

work is necessary to determine the existence or

workability of coal deposits in any unclaimed, undeveloped area..."

|

|

Coal Leasing

Amendment

Act of 1976 |

|

The Surface Mining and Reclamation Control Act of

1977 was passed to ensure rehabilitation of surface-mined

lands—most federal coal lands were to be mined in this

manner—and created the Office of Surface Mining. The National

Energy Act of 1977 called for increased coal development, energy

conservation, decontrol of natural gas pricing by 1985, and development

of alternate energy sources, such as solar, geothermal, wind, and

"mini-hydro" sources.

And finally, FLPMA had been enacted and President

Carter was in the White House. Before the court's decision on the NRDC

suit, Carter called for reform of the Federal coal leasing program,

wanting coal mining to be compatible with other uses of the land. He

also called for an investigation of current leases to determine if they

were being diligently developed in an environmentally sound manner.

After the Department reviewed BLM's coal program,

another policy review was mandated by the NRDC decision. In 1979,

Interior issued a final environmental impact statement on BLM's coal

program. As described by Frank Gregg, BLM's policy was to resume coal

leasing by "limiting sales to foreseeable needs, providing strong voices

for state and local interests, and enforcing stringent environmental

protection." The policy also sought to keep consumer prices down. With

this policy in mind, Interior projected a coal production shortfall

starting in 1985. Plans were made for coal lease sales to be held in

1981 and 1982, but a new administration would handle the sales.

|

|

|

In 1970, President Nixon reopened the idea of leasing

oil shale. A presidential task force recommended the government offer

20-year leases by competitive sealed bid at fixed royalty rates.

Secretary Hickel backed off the idea, saying that it was premature to

lease shale without more fully assessing the environmental consequences.

The discovery of oil on Alaska's North Slope may have influenced him

too.

|

|

Oil Shale |

|

Western Senators were up in arms about this perceived

about-face. In 1971, a prototype oil shale leasing program to develop

extraction technology was announced, provided that environmental

concerns could be resolved. BLM first asked the minerals industry to

nominate tracts. In 1973, it issued a six-volume EIS on the program. By

early 1974, four of the six tracts offered were leased by competitive

bid; the "C-a" tract in Colorado provided the largest bonus bid yet

received for a federal lease—$210 million—but it was never

fully developed. Although oil prices were up at the time, the cost of

oil shale retorting was still too high to make it economically

feasible.

|

|

|

The General Mining Law of 1872 came under increasing

criticism after the 1960s, but had not been repealed. In a letter to

Wayne Aspinall in 1969, Stewart Udall said, "This outmoded law has

become the major obstacle to the wise conservation and effective

management of the natural resources of our public lands."

|

|

Mining |

|

The Public Land Law Review Commission (PLLRC) took a

middle road on this issue. It recognized the law had problems—like

permitting people not really interested in developing minerals to obtain

mining claims for other purposes—but they also knew the mining

industry favored obtaining title to public lands.

PLLRC called for a new mining policy that

incorporated features of the 1872 act and the current mineral leasing

scheme. PLLRC suggested that only minerals be patented under the law.