|

LAKE ROOSEVELT The Grand Coulee Dam and the Columbia Basin Reclamation Project |

|

Section III.

THE COLUMBIA RIVER AND ITS WATERSHED (continued)

THE COLUMBIA LAVA PLATEAU

THE ORIGIN OF THE PLATEAU

Millions of years ago many successive floods of highly fluid basaltic lava poured out through fissures in the earth's crust and spread over the surface of central and eastern Washington, northeastern Oregon, and southwestern Idaho. These floods of lava cooled and solidified to form the generally horizontal rock strata of basalt which characterize the Columbia Lava Plateau. As the lava flows spread northward and westward they gradually pushed the Columbia River out of its ancient course from the Colville Valley toward Pasco, and forced it to detour far to the west around the edge of the lava flows where they met the older igneous rocks of the rising Cascade Mountains and the Okanogan Highlands. Thus was formed what is popularly known as the "Big Bend" region of the Columbia River. In this region of the Columbia Lava Plateau, one of the two largest lava flows now exposed on the earth's surface, are 1,200,000 acres of rich soil to be irrigated from Grand Coulee Dam.

In its new position the river eventually cut for itself a canyon as much as 1,600 feet deep, in many places bounded on one side by precipitous cliffs of lava and on the other by granite hills. At the site chosen for the Grand Coulee Dam granite is exposed on both sides of the river and forms the abutments and the base of the dam.

|

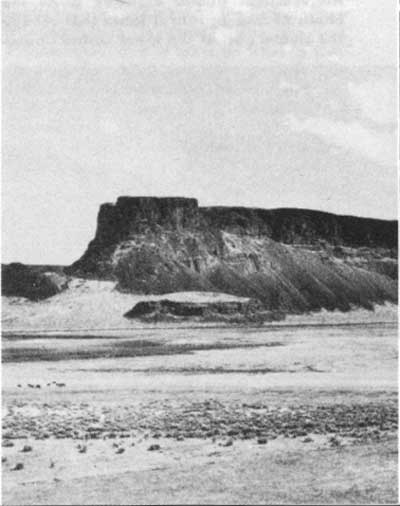

| Forty cubic miles of hard basalt cut out of the Columbia Lava Plateau left the Grand Coulee |

THE GRAND COULEE

The Grand Coulee is a prehistoric river bed, 52 miles long, 1-1/2 to 5 miles wide, and at places nearly 1,000 feet deep. It is one of a number of southwest-trending channels which were cut in the lava plateau of central Washington by the displacement of the normal Columbia River drainage during the period of the last great Ice Age.

Thousands of years ago, during the Ice Age, a thick sheet of ice moved southward into northern Washington. A portion of this ice sheet crossed and completely filled the gorge of the Columbia River at some point west of the site of Grand Coulee Dam. As a result of this ice obstruction, the upstream part of the gorge was converted into a great lake whose rising, turbid waters laid down hundreds of feet of sediment in the river canyon and ultimately spilled over through several low points in the south wall of the gorge, and flowed southwestward across the Columbia plateau. This temporary overflow swept away accumulations of surface soil, cut a complex series of channels into the lava sheets, and deposited millions of acre-feet of fine material in the lake created south and east of the Big Rend of the Columbia. In this manner were formed the scablands which are a prominent and interesting feature of geology of eastern Washington. The Grand Coulee, largest of these channels, is one of the scenic wanders of the Western United States.

|

| Two miles long and 900 feet high, Steamboat Rock is a spectacular landmark in the upper Grand Coulee |

A short distance north of Coulee City the generally horizontal lava flows of the plateau dip sharply to the southeast, forming an immense wrinkle in the plateau surface before they again flatten out at a lower elevation. It is believed that the waters of the glacial Columbia River, flowing down this steep surface, initiated a waterfall which gradually cut its way northward and formed the rock trench known as the Upper Grand Coulee. Steamboat Bock is a remnant of the plateau surface, 2 miles long and 1/2 mile wide, left as an island as the falls retreated northward.

Eventually these ancient falls died out as they ate away the last of the rock barrier which separated them from the valley of the Columbia River. As a result the upper coulee intersects the south wall of the valley of the Columbia River about 1 mile south (upstream) from the site of Grand Coulee Dam. At this point the floor of the coulee hangs about 500 feet above the level of the present river.

|

| An excellent public highway skirts the chain of four beautiful lakes that occupy the greater part of the lower Grand Coulee |

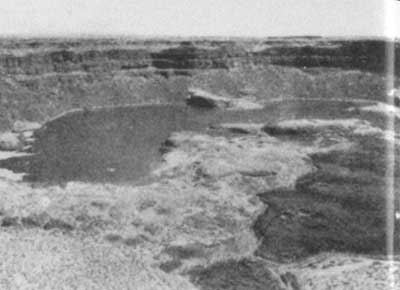

THE DRY FALLS OF THE COLUMBIA

The lower Grand Coulee was formed in a similar manner by retreating waterfalls which originated in the vicinity of Soap Lake. When the ice obstruction which had dammed and diverted the waters of the Columbia River finally melted away, the river resumed its old course and left at the head of the lower Grand Coulee a relic of its former might—the Dry Falls of the glacial Columbia River. They are located in the Dry Falls State Park a few miles south of Coulee City, on the road to Soap Lake. Here, from the roadside or from a vista house in the park, one can look at the site of the ancient waterfalls, more than 400 feet high and 3 miles wide, whose northward retreat cut the channel of the lower Grand Coulee. They are two and a half times as high and five times as wide as Niagara Falls, and according to some authorities the torrent of silt-laden water which poured over them is estimated to have had a volume as much as 100 times that at the present Niagara Falls.

Two of the five largest recesses in the 3-mile northern brink of the extinct cataract are within view from the vista house. In the plunge-pools at the foot of the first are Fall Lake and Perch Lake. In the second alcove is an alkaline lake, or an alkaline flat in dry weather. Opposite the point separating the first and second horseshoe falls is Umatilla or Battleship Rock, and beyond that the left wall of on extensive section of the Coulee extending eastward, and providing a bed for Deep Lake, a mile and a half long. Near the east end of Deep Lake are two alcoves on the north and one on the east.

|

| Dry Falls, head of the lower Grand Coulee, was the site of a cataract two and a half times as high and five times as wide as Niagara Falls |

LOWER GRAND COULEE

Along the State highway below the Dry Falls are Park Lake, Blue Lake, and Lake Lenore, each overflowing into the next in high-water periods, and all finally into Soap Lake which, having no outlet, is highly alkaline.

In the Coulee walls there are visible at least seven lava flows. The time intervals between some of the flows were so long that surfaces disintegrated into soil, and vegetation flourished. On the shores of Blue Lake below the sixth flow, are casts of huge trees buried by the lava as it flowed over the land. In the soils between lava strata, explorers have found fossil remains of the ginkgo tree, which now grows only in the Orient, of the Sequoia, now growing only in California, of oak, elm, yew, cypress, gum, and of other varieties of trees now growing elsewhere, proving that long periods elapsed between successive flows, and that sometimes semitropical climates existed here millions of years ago.

|

| The construction at the base of the Grand Coulee Dam across the Columbia River channel nears completion in the fall of 1937 |

Glacial floods removed deep soil from hundreds of square miles of the Columbia Lava Plateau, and from the Grand Coulee alone cut out and carried away 40 cubic miles of hard basalt. Some 25 cubic miles of such materials are estimated to have been deposited in a 250-square-mile lake in the Quincy Basin. This lake disappeared when a southerly outlet to the east of Frenchman Hills, and three westerly outlets to the Columbia, one now traversed by the highway to Vantage Bridge, were worn down below the level of the lake bottom, and left part of the land which is to be irrigated by means of the Grand Coulee Dam.

|

| The river now flows through low gaps in the dam in many low cascades that will, in time, grow into a 350-foot waterfall |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

grand_coulee_dam/sec3b.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2008