|

CABRILLO

The Guns of San Diego Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER 1:

EXPLORATION AND SETTLEMENT, 1535-1846

A. Exploration, 1535-1602

In the year 1535, Hernán Cortes entered Bahía de La Paz and took possession of the peninsula now known as Baja California for Charles I of Spain (also known as Holy Roman Emperor Charles V). A few years later Francisco de Ulloa sailed up the Pacific side of the peninsula on a voyage of exploration. Although a few scholars have concluded that Ulloa reached as far north as San Diego Bay, it is generally accepted that he traveled no farther than about two-thirds the length of the peninsula, to the vicinity of Punta Baja. [1] The honor of discovering San Diego Bay belongs to another captain of the sea, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo. [2]

Little is known of Cabrillo's birth and early years. He came to Mexico from Cuba in 1520 as a soldier in the expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez. Cabrillo took part in Cortés's march on Mexico City. Besides soldiering, he was known as a skilled mariner and shipbuilder. Later, having achieved wealth through the discovery of gold, he went into semi-retirement on his estates in Guatemala. In 1542 Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza called Cabrillo back to the king's service and appointed him commander of a sailing expedition up California's Pacific coast. According to historian Samuel Eliot Morison, Cabrillo's object "seems to have been exploration pure and simple, including of course, the hope of discovering new sources of gold and silver, or a seaport in 'Quivira,' the fabled country of the Seven Cities." [3]

Manned by conscripts and natives, the flagship San Salvador and the frigate Victoria departed the Mexican port of Navidad on June 27, 1542. [4] Bartolomé Ferrer served as Cabrillo's first pilot. According to the only surviving account of the voyage, on September 28 the vessels entered a hitherto unknown port, "closed and very good, which they named Puerto de San Miguel" in honor of the feast day of the Archangel Michael. [5] Cabrillo probably landed at what later Spanish Explorers named La Punta de los Guijarros (present-day Ballast Point), a spit of land jutting into the harbor entrance from the Point Loma ridge. During their six days in San Diego Bay, as it was later named, the Spaniards contacted the Kumeyaay Indians who informed them of white explorers (Diaz in 1540 and Francisco Vasquez de Coronado in 1541) having passed through the interior country.

After leaving San Diego Bay on October 3, the ships came to the Channel Islands where the sailors spent several days on San Miguel Island. The expedition continued northward, missing the entrance to San Francisco Bay, until it reached a little north of Bodega Bay by November. From there Cabrillo turned back to winter on San Miguel Island. On Christmas Eve, while on shore aiding his men who were fighting off an Indian attack, Cabrillo fell, breaking either his arm near the shoulder or his leg. On January 3, 1543, Cabrillo died from complications resulting from his fall. Pilot Ferrer took command and again sailed northward, finally reaching above 42° north latitude, at Rogue River, Oregon, the farthest north that Europeans had yet sailed in the Pacific. Cabrillo's voyage was soon forgotten, however; even the place names he bestowed disappeared from maps. [6]

Twenty-one years later, in 1564, a Spanish fleet sailed from Mexico's west coast, crossing the Pacific to Guam and on to the Philippine Islands. One of these ships successfully returned to Mexico in 1565. She had caught the summer westerlies and the Japan Current in the North Pacific and her first landfall was California's San Miguel Island. Thus began the annual sailing of the Manila galleons from Acapulco, the nearly all-ocean route between Spain and the Orient. Before long English ships began roaming the Pacific in pursuit of the Spanish galleons. In 1579 Sir Francis Drake landed north of San Francisco and claimed Nova Albion for Queen Elizabeth I. New Spain became alarmed about the English and grew concerned about Alta California's exposed coast. Also, a northern harbor was needed for the Manila galleons in case of needed repairs or shelter. [7]

As a result of these developments, the viceroy dispatched Sebastian Vizcaino north with an exploring fleet of three ships in 1602. One of the ships was lost at sea, but on November 10, 1602, San Diego and Tres Reyes dropped anchor in Cabrillo's San Miguel Bay. Vizcaino renamed the port in honor of San Diego de Alcalá de Henares (Saint Didacus), a Franciscan saint of the 15th century. [8] They spent ten days exploring the bay. According to a surviving diary of the expedition,

On the 12th of the said month, which was the day of the glorious San Diego, the general, admiral, religious, captains, ensigns, and almost all the men went on shore. A hut was built and mass was said in celebration of the feast of Senor San Diego.

Vizcaíno was impressed with the bay calling it "the best, large enough for all kinds of vessels, more secure than at the anchorage, and better for the careening ships." As did Cabrillo, Viscaino encountered a large group of Kumeyaay Indians while exploring the harbor. [9]

Besides naming Punta de los Guijarros and San Diego Bay, Vizcaíno examined Point Loma, the grand headland that protects the bay from the sea and which today is the southwestern point of land of the continental United States. The name Loma, however, did not appear on a map until Juan Pantoja's plans of 1772. Following his examination of San Diego Bay, Vizcaíno proceeded north, landing at Monterey Bay, he, too, being unaware of magnificent San Francisco Bay. [10]

B. Settlement, 1768-1846

1. The Presidio of San Diego and the Mission of San Diego

Despite the discoveries of Cabrillo and Vizcaíno in the 16th and 17th centuries and the development of the Manila galleon route, New Spain did not became serious about the protection of Alta California until the mid-18th century. By then, Russian advances southward from Alaska and an increasing British presence in the Pacific, convinced King Carlos III of Spain that the still unknown territory must be colonized. In 1768 the crown ordered the Viceroy of New Spain, Marquez de Croix, to occupy and fortify both San Diego and Monterey.

Two vessels, San Antonio and San Carlos, arrived in San Diego Bay in April 1769, bringing the first scurvy-stricken settlers. In May and June two overland caravans straggled in. One of these overland groups was led by the governor of California, Capt. Gaspar de Portolá. The Franciscan Father Junipero Serra accompanied the overlanders. The captains selected the lower slope of a hill, now called Presidio Hill, adjacent to the San Diego River for their combination fortification and mission. Father Serra blessed the cross on July 16 and dedicated this first mission in Alta California to San Diego de Alcalá. A hut became the church. Thus began European settlement of Alta California. When Indians attacked the camp in August, the Spaniards quickly erected a stockade around the humble establishment.

Perhaps it had been predetermined that the military installation and the mission should eventually be separate installations, as was usually the case, or perhaps conflicts between soldier and missionary caused the separation; in any case a decision was reached that the mission should be reestablished six miles up the river where the land promised greater opportunities for crops and grazing. As was customary, the military retained its own chapel and padre. By the end of December 1774, the fathers had settled in their new quarters. A small detachment of soldiers guarded the establishment.

In November 1775 800 Indians attacked the mission. Father Luis Jayme and two laymen were killed and the Indians set fire to the mission buildings. A new adobe church was completed in 1777, and the mission continued in its efforts to convert Indians. Father Serra, still engaged in expanding the California missions, made his last visit to San Diego in 1783. He died a year later having established nine missions in Alta California. In 1808 still another church was constructed at the mission and was dedicated in 1813.

Mexico, which obtained her independence from Spain in 1821, passed the Secularization Act in 1833. A year later Governor Pio Pico awarded the San Diego mission lands to a private citizen, José Rocha. In 1846 the last priest moved away and the mission closed. [11]

An early report of the military camp at San Diego, in 1773, stated that "the stockade is in a certain sense a presidio, two bronze cannons are mounted, one pointing toward the harbor, and the other toward the rancheria," i.e., the Indians. [12] By then the soldiers had manufactured 4,000 adobe bricks and the construction of additional facilities was underway. A year later San Diego was promoted in status to a regular royal coastal presidio authorized to house the guards attached to the missions in addition to protecting the general interests of the Spanish crown. At that time the presidial garrison consisted of a lieutenant, sergeant, two corporals, twenty-two soldiers, two carpenters, two blacksmiths, and a storehouse keeper. Lt. José Francisco Ortega held the office of commander. By 1778 adobe walls had replaced the wood stockade and the population had grown to 125: soldiers, families, and artisans. [13]

|

| Mission San Diego de Alcalá in ruins. Photo by C.T. Collier, no date, FN - 08418. Courtesy, California Historical Society |

|

| "El Jupiter," a Spanish cannon now mounted on the site of Fort Stockton on Presidio Hill, overlooking San Diego. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service. |

|

| Undated sketch of the San Diego Barracks. Courtesy of San Diego Historical Society, Union Title Insurance and Trust Company Collection |

|

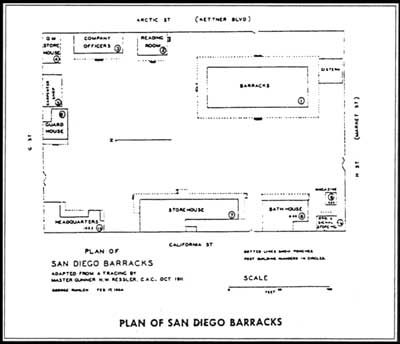

| Plan of San Diego Barracks, 1911. Courtesy of the San Diego Historical Society and the National Archives, Record Group 77, Fortification File |

The number of artillery pieces at the presidio was never large. When George Vancouver, the British sea captain, visited San Diego in 1793, he was surprised at the weakness of the harbor's defenses. He noted that the garrison comprised sixty men and three small brass cannon. Furthermore, the presidio was five miles from the anchorage where there were no defenses. The presidio "seemed to be the least of the Spanish establishments. It is irregularly built, on very uneven ground.... With little difficulty it might be rendered a place of considerable strength, by establishing a small force at the entrance of the port." [14] The acting governor of California, Capt. José Joaquín de Arrillaga, became concerned that Vancouver had learned of the weak defenses of both San Diego and San Francisco, which he had visited earlier. He reported his concern to Viceroy Revilla Gigedo who directed that the coastal presidios be strengthened with batteries of eight 12-pounders and eighty gunners. [15]

Despite its weaknesses, the presidio served as a prison for a party of American fur trappers during the Mexican period. Sylvester Pattie, his son James, and six others made their way down the Colorado River in 1828. They crossed the desert and the mountains and arrived in San Diego. The Mexican governor accused them of being spies for Spain and had them incarcerated in the presidio cells. There, Sylvester died, while James did not succeed in returning to the United States until 1830. About this time, a French visitor arrived in San Diego and reported:

Of all the places we had visited since our coming to California, excepting San Pedro, which is entirely deserted, the presidio at San Diego was the saddest. It is built upon the slope of a barren hill, and has no regular form: it is a collection of houses whose appearance is made still gloomy by the dark color of the bricks, roughly made, of which they are built." [16]

|

| The site of the Presidio of San Diego which was founded in 1769. The fencing marks the area where archaeological work has uncovered portions of the foundations. Photo by E. Thompson |

|

| Reconstructed Mission San Diego de Alcalá, 1998. Photo by E. Thompson |

After Mexico gained her independence, funds became scarce for the upkeep of California's presidios. When Richard Henry Dana first went ashore at San Diego in 1835, he and a companion rode to the presidio:

The first place we went to was, the old ruinous presidio, which stands on a rising ground near the village [Old Town], which it overlooks. It is built in the form of an open square, like all the other presidios, and was in a most ruinous state, with the exception of one side, in which the commandant lived, with his family. There were only two guns, one of which was spiked, and the other had no carriage. Twelve, half clothed, and half starved looking fellows, composed the garrison; and they, it was said, had not a musket apiece. [17]

Following Dana's visit, the presidio continued to decay. The last commandant, Alferez Salazar, prepared his final report in 1842. When American forces occupied San Diego in 1846, the establishment lay in ruins.

2. Fort Guijarros

When Viceroy Revilla Gigedo directed a battery be built, at no cost to the crown, for the protection of San Diego's port, engineers selected Point Guijarros (Ballast Point). Lumber, including 103 23-foot planks, arrived from Monterey. Santa Barbara furnished axle-trees and wheels sufficient for ten carts. Bricks and tiles came from local sources. The castillo has come down in history as Fort Guijarros despite being officially blessed as El Castillo de San Joaquín in 1796. (The castillo at San Francisco received the same name.) By early 1798, $9,000 had been spent to construct a battery, a wooden casemate, magazine, barracks, flagstaff, and a flatboat. The number of guns mounted in the battery seems to have varied greatly from time to time. Two Americans who visited the work in 1803 had differing opinions concerning the armament. One said there were eight brass 9-pounders in good order, with plenty of ball. His companion disagreed and described it as a sorry battery of 8-pounders that did not merit consideration as a fortification.

In 1803 the American merchant vessel Lelia Byrd arrived in San Diego. William Shaler, the ship captain, assured the local authorities that they had entered the harbor only for water and supplies. The suspicious Spaniards placed a guard on the ship to insure that the Americans would not attempt to purchase and smuggle out otter skins, as commercial intercourse with foreign vessels was prohibited by Spanish law. Smuggle they did, and the next morning they raised anchor and set sail. As the ship approached Fort Guijarros, the battery raised a flag and fired a blank cartridge. Lelia Byrd sailed past, firing two broadsides from her six 3-pounders. The Spaniards returned fire but inflicted little damage. Once past the fort, the Spanish guard was allowed ashore and the ship sailed on. [18]

A second incident involving the castillo occurred after Mexico had won independence. In 1828 the American ship Franklin, captained by John Bradford, entered San Diego Bay. When Mexican officials ordered Bradford to place his cargo in a warehouse as security for duties and be investigated for smuggling, he refused and prepared to leave port. As the ship passed the castillo, the Mexicans fired some forty rounds, causing some damage to the rigging and wounding Bradford. [19]

Around the same time the Frenchman Duhaut-Cilly was impressed with San Diego Bay and Point Loma, where he went on hunting expeditions:

San Diego Bay is certainly the finest in all California, and much preferable for the safety of vessels, to the immense harbor at San Francisco... it is a passage, from one to two miles wide, running at first in a north-northeast direction, then turning toward the east and southeast, forming an arc five leagues in length. It is sheltered, to the west, by a long, narrow and steep hill extending from the south-southwest, under the name of Point Loma. Two miles within from this point, juts out, perpendicularly to it, a tongue of sand and pebbles like an artificial mole, ending in a perfectly rounded bank. A deep passage, about two hundred fathoms wide, divides this natural causeway [from a sandy peninsula].

A rasant [low built] fort of twelve guns is built upon the point where this tongue of land joins Loma. On our approach, the Mexican flag was raised and enforced by a shot; at once we hoisted our own, paying it the same respect. [20]

The Franklin incident ended military activity on the bay until the Mexican-American war. Like the presidio, the castillo deteriorated rapidly in the 1830s. The garrison departed in 1835. In 1840 Don Juan Machado, a civilian, purchased the remnants of the fortifications for $40. Point Guijarros became a part of a United States military reservation in 1852. An army engineer prepared a map of a portion of the reservation in 1902 which shows the location of the castillo in front of Battery Wilkeson. Archaeological excavations of the site in the 1980s disclosed ruins of the ancient fortification, including hundreds of tile fragments and redwood planking. [21]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

cabr/guns-san-diego/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 19-Jan-2005