|

CABRILLO

The Guns of San Diego Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER 4:

FORT ROSECRANS, 1898-1920

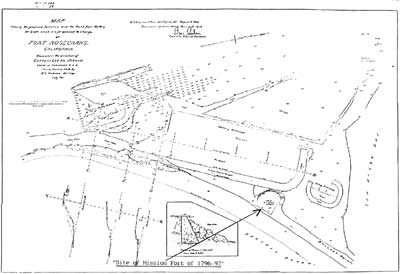

A. Endicott Board, 1885-1895

During the fifteen years that Congress refused to appropriate funds for new construction of coastal fortifications, it did allow for the "protection, preservation, and repair" of existing works. Lt. Col. Charles Stewart, in the Engineers' San Francisco office, became responsible for the maintenance of Fort Point batteries at the Presidio of San Francisco and the battery at Point Loma. About $1,500 was allotted annually for each area, most of which went to pay civilian "fort keepers." Stewart and his successors visited San Diego from time to time, but these trips involved mostly the Corps of Engineers' civil works responsibilities concerning San Diego Bay. [1]

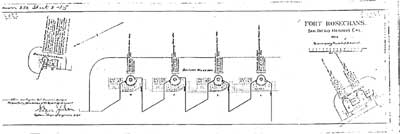

By the 1880s, a sizable segment of the American public in government and out, and in the military, became increasingly alarmed at the deterioration of coastal fortifications and the development of modern steam battleships in foreign navies. At the same time, arsenals were employing steel in building guns; breech loading and rifling were perfected; improved gun carriages were devised; and new propellants were developed. E. Raymond Lewis has pointed out that a Civil War 10-inch Rodman smoothbore had a maximum range of 4,000 yards with a 123-pound shot, while an 1890 10-inch rifled gun had a range of 12,000 yards with a 604-pound shot. In the face of mounting concern, Congress passed a bill early in 1885 calling for the executive branch to review the matter of the United States' coastal defense. [2]

The newly elected President Grover Cleveland promptly appointed a Board of Fortifications or Other Defenses on March 3, 1885. Secretary of War William C. Endicott became president of the board, thus lending his name to the undertaking. Four army officers, two naval officers, and two civilians made up the rest. The board met regularly throughout the summer and fall and in December announced a list of twenty-two American ports arranged in order of importance and the urgency necessary for their defense. The first port on the list was New York; the twenty-second, San Diego. The Endicott Board's final report, issued in 1886, recommended four high-power, 10-inch rifled guns for San Diego, two to be emplaced at Point Loma and two at Ballast Point. [3]

Despite the thoroughness of the board's investigation, Congress was slow to act. Not until 1890 did it pass the first appropriation for the modernization to begin. The Endicott Board had estimated the total cost of the project at $126 million; through the 1890s, the annual appropriations averaged $1.5 million. [4] The next recommendation for San Diego came from an Artillery Board appointed by the commanding general of the Division of the Pacific in 1889. This board proposed four high-power rifled guns, three converted rifles, and eight rifled mortars:

| Point Loma | two 10-inch guns and four 12-inch mortars |

| Ballast Point | three 8-inch converted rifles |

| North Island | two 8-inch guns and four 12-inch mortars [5] |

The next investigation resulted from a bill that the U.S. Congress passed in 1891 directing the Secretary of War to appoint a special board of officers to determine sites for a military post and harbor defenses in San Diego. The board's findings were transmitted to the Congress in December. It concluded that there should be batteries at Ballast Point and the west end of North Island. A mortar battery and a "few" guns were recommended for Point Loma. Also, batteries should be placed at the "Brickyard" southeast of the Coronado Hotel. As for a post, the board rejected the military reservation and recommended 1,030 acres of private land located two miles northeast of the reservation. [6]

These early boards set the stage for the Corps of Engineers to get down to serious business regarding the defenses of San Diego in 1894. This newest board was composed of six experienced engineers: Cols. George H. Mendell, Henry L. Abbot, Cyrus B. Comstock, and Lt. Cols. Peter C. Hains, Henry M. Robert (of parliamentary procedure fame), and George L. Gillespie. The colonels visited San Diego in May and finished their report early in 1895. They noted that San Diego's population now exceeded 30,000 and that it had railroad connections to the rest of the country. The party traveled to Point Loma on a road along the crest of the ridge and reached the summit near the old lighthouse. This summit commanded the harbor and its approaches. East of the lighthouse at an elevation of 70 to 100 feet they spotted a space sufficient for three or four guns. (The Army later called this site Billy Goat Point.) South of the lighthouse at 300 feet elevation they selected a site for a gun battery that commanded the ocean approach to the harbor (probably the later location of Battery Humphreys). The trip out to Ballast Point was on a difficult trail that wound among the steep escarpments. On examining the 1873 work, they concluded the site was suitable for a battery that would sweep the harbor entrance. As for the island across the channel (they did not know it as North Island), they disagreed with the 1891 board and recommended no battery there. The board also visited Coronado Beach where they selected a site 1-1/2 miles south of the Coronado Hotel for a mortar battery that would cover the ocean area in front of San Diego and National City. They summarized their findings thus:

Point Loma, south of old lighthouse, two 10-inch guns, non-disappearing carriages

Point Loma, east of old lighthouse, two 8-inch guns, disappearing carriages

Ballast Point, four 10-inch guns, disappearing carriages

Coronado Beach, sixteen 12-inch mortars protected by three quick-fire guns to repel landing parties.

The board also suggested some rapid-fire guns at Ballast Point to cover the submarine minefield and repel landing parties. The colonels estimated the total cost for San Diego Harbor to be $882,000. [7]

B. The First Batteries,

1896-1900

Of the four sites selected by the 1895 board, engineers constructed a battery only at Ballast Point, the four 10-inch guns on disappearing carriages. In September 1897 Col. Charles R. Suter, the Pacific Division Engineer, visited the contractor's work at Ballast Point. "Three emplacements for 10-inch guns on disappearing carriages are being built on Ballast Point, and also a torpedo [submarine mines] casemate. This latter was well advanced towards completion and nearly ready for back-filling. The two left-hand emplacements, contracted for last year, were about completed so far as the concrete work is concerned, but the earth filling of parapets and traverses had not been commenced. The third emplacement had been begun, excavation completed, foundations laid, and erection of forms begun." Suter was generally pleased with the work which 1st. Lt. James J. Meyler, CE, supervised. [8]

Suter considered the roads on Point Loma terrible. He recommended construction of a road along the harbor shore from a wharf at La Playa to Ballast Point and beyond to Billy Goat Point and on up the ridge to the old lighthouse. Also, the old road from Ballast Point up to the old lighthouse, which had been built for the Lighthouse Board in the 1850s, should be reconstructed. He thought the road on top of Point Loma should be strengthened for the transport of heavy ammunition. [9]

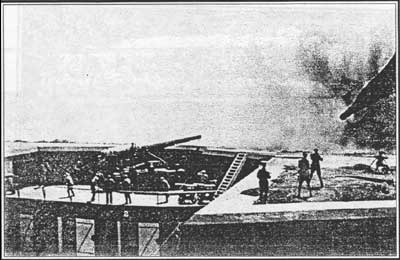

A month later, the Fortifications Board in New York, which reviewed all plans for coastal defense in the nation, had some additional thoughts on the defense of San Diego. In addition to rapid-fire guns at Ballast Point, it recommended six for "The Island" east of the entrance channel. As for the defenses on Coronado Beach, the board thought that work could be postponed until all the batteries for the protection of the entrance channel were completed. [10] By March 1898, the third 10-inch emplacement was completed and work had begun on the fourth. When completed the battery was named in honor of Bvt. Lt. Col. Bayard Wilkeson, an artilleryman killed at Gettysburg, July 1, 1863. In 1915, the battery was divided; guns 1 and 2 on the right flank retained the name Wilkeson, and rifles 3 and 4 were named in honor of Col. John H. Calef, another artilleryman who had fought in the Civil War. He retired from the U.S. Army in 1900 and died in 1912. [11]

|

| Battery Wilkeson, four 10-inch guns, 1903. As of then, Ballast Point had not been widened with fill. The magazines of this battery are said to be in excellent condition. Old Ballast Point Light Station in background. Courtesy of National Archives, Photo No. 77-CD-22D-1. |

|

| No. 2 Gun, Battery Wilkeson, firing. These 10-inch guns were mounted on disappearing carriages. At the moment this photo was taken, the gun tube was beginning to retract — note the soldiers at the rear ducking. Photo taken between 1904 and 1911. Photo courtesy of Maj. Gen. George Ruhlen, U.S.A. Ret. |

|

| A sketch showing how fire control is coordinated. From the R.O.T.C. Manual, Coast Artillery, Basic, p. 15. |

|

| Calef-Wilkeson base-end station, located in the northeast quadrant of Cabrillo National Monument. Station is located to the west of the Bayside Trail/Sylvester Road. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

|

| Interior of base-end station with bench and ring on floor intact. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

|

| General Tasker H. Bliss, Chief of Staff, U.S. Army, reviewing Fort Rosecrans' Coast Artillery in 1911. Battery Wilkeson in background. Photo by Col. George Ruhlen, U.S.A. Photo courtesy of Maj. Gen. George Ruhlen, U.S.A. Ret. |

|

| Battery Fetterman, 3-inch guns. Note apparent censorship effort in lower right. No date. Photo courtesy of Maj. Gen. George Ruhlen, U.S.A. Ret. |

|

| Fort Rosecrans, 1911. Officers' row in foreground; enlisted barracks in distance. Photo by Col. George Ruhlen, U.S.A. Photo courtesy of Maj. Gen. George Ruhlen, U.S.A. Ret. |

|

| Battery James Meed, Fort Pio Pico, 1911. A 3-inch gun firing. These weapons were later moved to Battery McGrath, Fort Rosecrans. Photo by Col. George Ruhlen, U.S.A. Ret. Photo courtesy of Maj. Gen. George Ruhlen, U.S.A. Ret. |

The cost of the battery amounted to $217,300. Data on the guns and their carriages follow.

| Guns | Caliber | Model | Serial No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 | 10-inch | 1895 | 8 | Watervliet Arsenal |

| 2 | 10-inch | 1888 M1 | 10 | Bethlehem Iron Company |

| 3 | 10-inch | 1888 M1 | 10 | Watervliet Arsenal |

| 4 | 10-inch | 1888 M1 | 4 | Watervliet Arsenal |

| Carriages | Model | Serial No. | Manufacturer | Motor |

| 1 | 1896 | 53 | Watertown Arsenal | 8 hp |

| 2 | 1896 | 7 | Niles Tool Works | 8 hp |

| 3 | 1896 | 5 | Niles Tool Works | 8 hp |

| 4 | 1896 | 6 | Niles Tool Works | 8 hp |

The destruction of the battleship USS Maine in La Habana Harbor on February 15, 1898, resulted in a fresh sense of urgency to provide additional defenses on all coasts. Within a month, Congress voted $50 million for defense. In April, the Spanish-American War began. At San Diego, three additional batteries at the harbor entrance were completed by 1900: Battery McGrath, two 5-inch rapid-fire guns on balanced pillar mounts on Battery's right flank, its primary mission being the defense of the minefield; Battery Fetterman, two 3-inch guns on Wilkeson's left flank, for sweeping the channel in case of attack by boats or small vessels; and Battery James Meed, also two 3-inch guns, across the channel on North Island (Fort Pio Pico). Battery McGrath was named in honor of Maj. Hugh J. McGrath, Fourth Cavalry, who died of wounds received in the Philippines in 1899. In 1902 the Congress awarded him the Medal of Honor for heroism. Battery Fetterman was named in honor of 2nd Lt. George Fetterman, 3rd U.S. Artillery, who died in 1844. Battery James Meed was named for Capt. James Meed, Seventeenth Infantry, who was killed in action against the British and Indians at Frenchtown, Michigan, 1813. [12]

C. Mining the Harbor Entrance,

1898

The U.S. Army had perfected a system of electrically controlled submarine mines, then called torpedoes, for mining harbor entrances in the 1880s. These mines required a bombproof mining casemate, or control room, from which cables ran out into the water and from which an operator sent the impulse to explode the mines. In 1897, 1st. Lt. Meyler supervised the construction of such a casemate located one-eighth of a mile north of Battery Wilkeson. A concrete cable tank and a mine storehouse soon followed. At the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, in the national defense appropriations act of March and subsequent acts, a sum of almost $2 million was set aside for mine defenses. On the West Coast, army engineers at both San Francisco and San Diego prepared to mine the harbors. [13]

In April 1898, 1st. Lt. Meyler received orders to mine the harbor entrance with the unusual addendum to secure the help of a "corps of 120 patriotic citizens" to lay the mines. The lieutenant succeeded in organizing a volunteer company of eighty citizens: electricians, civil engineers, surveyors, telegrapher, boilermakers, steam engineers, mechanics, carpenters, divers, and laborers. Cable, explosives, and other supplies arrived by steamer from San Francisco. On May 11, five engineer enlisted men, trained in mine laying, came to add a touch of professionalism to the undertaking, "The volunteers, while willing and anxious to do their best, were constantly showing their lack of experience, which in some cases resulted in considerable delay to the work at hand. The five engineer soldiers, who had had previous experience in this kind of work, were of the greatest assistance. They not only did much of the work of loading the mine torpedoes, but they also watched over all the work done by the volunteers." Meyler succeeded in planting fifteen mines in the entrance channel, leaving a safe passage for friendly commerce. Two smoothbore cannon, model 1863, protected the minefield. Although there was no danger of a Spanish attack on the harbor, the mines remained planted until September. [14]

D. Fort Rosecrans Established,

1898-1917

In February 1898, Capt. Charles Humphreys, commanding officer of San Diego Barracks, dispatched Lt. George T. Patterson and twenty-two enlisted men of Company D, 3rd Artillery Regiment to Ballast Point to camp. Thus, the military reservation at Point Loma was finally occupied by artillerymen. The following month Humphreys led the remainder of the company to the new camp. While Humphreys soon returned to his headquarters office, the company remained at Ballast Point throughout the summer, returning to the Barracks in August. A detachment remained at Ballast Point during the following months to occupy and guard the new battery. [15]

The War Department named the reservation Fort Rosecrans in General Orders 134, July 22, 1899, in honor of Maj. Gen. William Starke Rosecrans who had died in 1898. Rosecrans graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1842 and accepted an appointment as lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers. He resigned from the Army in 1854 to enter the oil industry in Pennsylvania. He returned to active duty on the outbreak of the Civil War. Rosecrans rose rapidly in rank, becoming a major general of volunteers in 1862. At first successful against Confederate forces, he was defeated by Gen. Braxton Bragg at Chickammauga in 1863. Following the war, he resigned again to serve as U.S. minister to Mexico. Later he engaged in mining and railroad operations in Mexico and California and was well-known in San Diego. From 1881 to 1885 he served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for California. In 1889 he returned to active duty for a few days with the rank of brigadier general in the Regular Army. [16]

When the 30th Company, Coast Artillery, arrived from duty in the Philippines in 1901, it occupied both San Diego Barracks and Fort Rosecrans. Maj. Anthony W. Vodges, Artillery Corps, commanded both posts. A month later, the 115th Company, Coast Artillery, was formed. For the next two years, one company was stationed at Fort Rosecrans and one at the Barracks. They rotated monthly so that both could engage in target practice at the batteries (the company in San Diego carried out infantry and signal drills). Troop transfers were usually by water by means of the steam-propelled launch General DeRussy and the motor launch Lieutenant George M. Harris. On occasion, the companies marched overland 8.7 miles. Finally, on August 6, 1903, Fort Rosecrans was organized as a separate post and both companies were permanently stationed there. Capt. Adrian S. Fleming, Artillery Corps, became the commanding officer of both Fort Rosecrans and the Artillery District of San Diego. The garrison consisted of five officers and 192 enlisted men. To celebrate their new arrangements, the troops held a field day on August 22. The post returns show that the companies were becoming proficient at Batteries Wilkeson, McGrath, Fetterman, and James Meed. The 30th Company had eight 1st class and sixteen 2nd class gunners; while the 115th Company had fourteen and eleven respectively. [17]

The early history of Fort Rosecrans witnessed a wide array of events, some of which are recounted here with no attempt at continuity of subject. In September 1903, Maj. Gen. Arthur MacArthur, commanding the Department of California, made a two-day inspection of the post. In addition to the companies, the fort had a sizable group of non-commissioned officers, the men who really operated the Army at the time: a sergeant major, two ordnance sergeants, commissary sergeant, two post quartermaster sergeants, electrical sergeant, and a first class sergeant in the Hospital Corps. The 30th Company transferred to Fort Worden, Washington, in June 1904, and was not replaced until July 1905 when the 28th Company arrived. That same month the boilers of the gunboat USS Bennington blew up in San Diego Harbor. The Army turned over the buildings at San Diego Barracks for the use of survivors. The post surgeon and his staff went to the Barracks to care for the wounded. Forty-nine of Bennington's dead sailors were buried in the Fort Rosecrans cemetery.

|

| 12 Lb Napoleon and Limber. Saluting cannon at left. Circa early 1900s, Fort Rosecrans. Photo courtesy of Point Loma Camera, San Diego, California. |

|

| 28th Company, Coast Artillery Corps, Fort Rosecrans, circa early 1900s. Photo courtesy of Point Loma Camera historic photo collection. |

|

| 115th Company, Coast Artillery Corps, Fort Rosecrans, circa early 1900s. Photo courtesy of Point Loma Camera historic photo collection. |

|

| A unit of Coast Artillery Corps in WWI uniform. Photo courtesy of Point Loma Camera historic photo collection. |

|

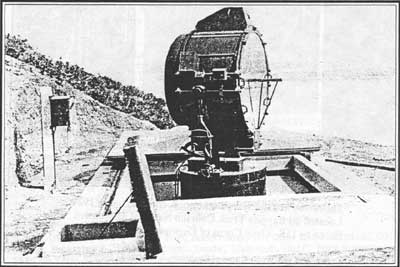

| Battery White, October 25, 1916. This Endicott Mortar position is currently located on the Naval Submarine Base. Photo courtesy of Cabrillo National Monument. |

|

| Battery White, aerial photo circa 1922. Photo courtesy of National Archives. |

|

| Construction of Battery Whistler. Photo taken looking south, Battery Whistler currently located on Naval Ocean Systems Center property. Photo courtesy of Cabrillo National Monument. |

|

| Battery Whistler, October 25, 1916. Photo courtesy of Cabrillo National Monument. |

In August 1905, the Italian cruiser Umbria visited San Diego. Undoubtedly, the fort's salute gun welcomed the vessel. Lt. Col. John McClellan, commanding the post, visited the cruiser. The ship's captain, his officers, and twenty sailors visited the post two days later and placed a large wreath of flowers on the graves of Bennington's dead. Inspecting officers came and went with a certain regularity, such as Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston who stopped by in October 1905. A month later Battery Fetterman saluted German cruiser Folke and again the post's commanding officer visited the ship. In April 1906 the new post commander, Maj. Charles G. Woodward, visited USS Chicago, the flagship of the Pacific Squadron, and cruiser USS Marblehead. The admiral and his staff returned the visit to the post and cemetery. Not to be outdone by its European neighbors, French cruiser Catinat entered San Diego Harbor in July 1906. The usual salutes and visits were exchanged. At this same time, Maj. Gen. Adolphus W. Greely inspected the troops and fortifications. The post returns for July 1907 noted the twelve-day annual "Joint Army and Militia Coast Defense" exercises had been completed. The militia this year consisted of over 200 personnel from the 5th Infantry, California National Guard. [18]

The routine was broken in January 1911 when a detachment of officers and men was dispatched to Calexico on the Mexican border "for the purpose of aiding in the enforcement of the neutrality laws of the United States." Mexico was in the throes of a revolution. By the end of February, detachments had moved to Calexico, Tijuana, Campo, Tecate, and Jacumba Spring. The department commander, Brig. Gen. Tasker H. Bliss, visited the post regularly during this period. A climax of sorts occurred in June 1911 when a detachment from the fort went to Tijuana to bring back 105 "insurrecto" prisoners who had crossed over to the American side of the border. The Army interned them at the post where it discovered that two of them were deserters from the 28th Company. These two men were confined to the guardhouse, while the Mexican rebels occupied the post gymnasium. Later, five others turned out to be deserters from the U.S. Navy and Marines. The Army turned them over to the Pacific Fleet. On June 25 all but five of the insurgents were released. Of the five, two remained in the post hospital and the other three were turned over to U.S. Marshal H. V. Place on warrants issued by the U.S. Commissioner in San Diego.

The name Lt. George Ruhlen, Jr., first appeared in Fort Rosecrans post returns in January 1911, when he was assigned to the 28th Company. He was to have a long association with the post both directly and indirectly. In February he led one of the detachments to the Mexican border. By May 1912 he had become the commanding officer of the 28th Company. He and the company participated in the Memorial Day Parade in San Diego on May 30. In August he transferred to the Coast Artillery School at Fort Monroe, Virginia. Several years later, in 1918, Maj. Ruhlen returned to Fort Rosecrans temporarily to act as umpire for practice at the 10-inch rifles. From 1927 to 1931, he was stationed in San Diego as a coast artillery instructor for the California National Guard. He served as commanding officer of Fort Rosecrans from 1933 to 1935. After retirement from the Army in 1944, Col. Ruhlen settled in San Diego where he became president of the San Diego Historical Society. His many publications on the history of the military in San Diego have been cited herein. [19]

Another incident related to the United States-Mexico boundary occurred in April 1913. Acting upon instructions from the Western Department in San Francisco, a small guard from Fort Rosecrans crossed the harbor to San Diego. There, it apprehended Gen. Pedro Ojeda, three lieutenant colonels, a paymaster, three captains, nine lieutenants, a telegrapher, and an enlisted man of the Mexican "Federales." The group was interned in the post exchange building until the Western Department ordered their release. They left the port by steamer. [20]

On the whole, the artillerymen found Fort Rosecrans to be an agreeable station. Despite the marches to the border, they had ample time for intensive training. The schedule of instructions for 1915-1916 illustrated the thoroughness of their projects:

| March 1915 | gunners' examination post and garrison school work one week on water and mine practice |

| April-June | drill and instruction one week per month on water and mine practice |

| June 15-July 31 | service gun practice mine practice |

| August | militia encampment and militia service practice |

| September | infantry field training and exercises mine practice |

| October | aiming and sighting drills gallery practice small arms, machine gun, and field gun practice mine practice |

| November | complete target practice mine practice post and garrison school work |

| December | drill and instruction one week on water and mine practice small arms target practice post and garrison school work |

| January-February | drill and instruction [21] |

Troubled Mexico caused more marches to the Mexican border in the years before World War I. But more pleasant marches occurred in September 1913 when San Diego celebrated "Carnival Cabrillo." The three-day carnival celebrated the 400th anniversary of discovery of the Pacific Ocean by Balboa, the 371st anniversary of Cabrillo's discovery of San Diego Bay, and the 144th anniversary of the founding of the California missions by Father Serra. The purpose of the celebration was to draw attention to San Diego, whose Panama-California International Exposition was to open in 1915. On September 25 Fort Rosecrans' battalion of coast artillery marched to the old lighthouse on Point Loma where dedication ceremonies were held for a proposed 150-foot statue of Cabrillo that was to be erected there. The next day the battalion marched in a street parade in San Diego in connection with the dedication of the site where a Balboa monument was to be built. On the third day, the 28th Company took part in the unveiling of a large cross that honored Father Serra on Presidio Hill. [22]

The year 1913 brought the highest-ranking brass ever to visit the fort. Secretary of War Lindley M. Garrison arrived to inspect the post. Accompanying the Secretary were Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood, Chief of the Quartermaster Corps, and Brig. Gen. Erasmus M. Weaver, Chief of the Coast Artillery. Unfortunately, the results of the inspection have not been found. [23]

The U.S. Corps of Engineers completed the Panama Canal in 1914, and San Diego planned to celebrate. Despite the training schedule, the companies at Fort Rosecrans played an important role in the Panama-California International Exposition throughout 1915. In addition to the regular garrison (28th and 115th Companies), the 30th and 160th Companies arrived from Washington State for temporary duty. Another important element in the celebration was the 13th Coast Artillery Corps band which came from Fort DuPont, Delaware. Time after time, officials requested the presence of troops on the exposition grounds. The companies paraded for the visit of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, in the Spanish-American War Veterans parade, for U.S. Vice President Thomas R. Marshall's arrival, and many other occasions. In return, the exposition gave annual passes to all the army wives at the fort. On two occasions, the commanding officer was directed to fire the 10-inch guns for the benefit of visiting congressmen. [24]

The border troubles with Mexico climaxed in 1916 when President Woodrow Wilson ordered Maj. Gen. John J. Pershing to head a punitive expedition of 15,000 men to pursue freebooter Pancho Villa into Mexico and called out 150, 000 National Guard to guard the border. Between this activity and World War I raging in Europe, Fort Rosecrans tightened security. Vessels entering the harbor were required to identify themselves. The coming of war brought a sense of urgency regarding San Diego's coastal defenses. [25]

E. Advances in Coastal Defense, San Diego

Harbor, 1901-1920

Twenty years after the Endicott Board made its report on seacoast fortifications, President Theodore Roosevelt directed Secretary of War William Howard Taft to review the national program and to evaluate recent developments. Among the Taft Board's more important findings were the organizing of coastal searchlights in batteries for illuminating harbor entrances and approaches; the electrification of fortifications, including lighting, communications, and ammunition handling; and a modern system of aiming. Of this last, historian E. Raymond Lewis writes that it was the most significant advance made in harbor defense fire control until the introduction of radar. Until now aiming had been done from individual guns with elementary instruments.

The new system, in contrast, was based on a combination of optical instrumentation of great precision, the rapid processing of mathematical data, and the electrical transmission of target-sighting and gun-pointing information. Of the several methods of fire control devised about the time, the most elaborate and precise made use, for a given battery, of two or more widely spaced sighting structures technically known as base-end stations. From these small buildings simultaneous optical bearings were continuously taken of a moving target, and the angles of sight were communicated repeatedly to a central battery computing room. Here sightings were plotted and future target positions were predicted.... The computed products were then translated into aiming directions which were forwarded electrically to each gun emplacement or mortar pit. [26]

In September 1905, a high-powered committee of officers visited Fort Rosecrans with the mission of revising the Endicott Board's findings regarding San Diego Harbor. [27] The Los Angeles District Engineer had been busy making improvements at San Diego even before the committee's arrival. Among other things, a central power plant had been constructed in "Power House Canyon" behind Battery Wilkeson in 1905. It served all the batteries and a 30-inch coastal searchlight that had been installed near Battery McGrath in 1902. Now the Board recommended the installation of three additional searchlights on Point Loma. [28]

The Taft Board did not recommend any additional artillery for San Diego, but as a result of its findings there was a definite, if gradual improvement in fire control for the existing batteries. The first fire control stations were often temporary in nature and few in number. Gradually, permanent stations were constructed with concrete walls and tar and gravel roofs. But a standard fire control system did not get installed at San Diego until World War I. When first built, these concrete structures were "open type stations." Then, in 1919, the Chief of Engineers directed that roofs be constructed for all of them. The base-end stations at this time received concrete and earth coverings, while the fort commander's and the fire commander's roofs were flat steel.

Maj. William C. Davis, commanding Fort Rosecrans, noted in 1913 that the completion of the Panama Canal would increase the commercial and strategic importance of San Diego Bay. It was time for the installation of standard fire control equipment. Army Engineers soon began preparing such a plan for Battery Wilkeson that called for two battery commanders' (BC) stations (Wilkeson was soon to be divided into two batteries), two primary stations (B1), and two secondary stations (B2), the last to be built at Fort Pio Pico across the channel. Also, stations were to be built for the fort and fire commanders. [29]

By the end of World War I eight base-end stations, four on Point Loma and four at Fort Pio Pico, were in operation. Two of these stations, then called B1/3 and B1/4, remain on the east side of Point Loma within Cabrillo National Monument and are on the List of Classified Structures as HS8 and HS9. At that time they were the primary stations for Batteries Wilkeson and Calef. Also by 1918, all of North Island had become federal property, the Navy using the north half for aviation purposes and the Army having established Rockwell Field in the southern half. The Engineers took advantage of this situation and moved four base-end stations from Fort Pio Pico farther east on the newly acquired land, thereby lengthening the base lines by nearly 2,000 feet. (Sufficiently long base lines at Point Loma had long been a problem because of the rugged terrain of the reservation.) In 1917 the Chief of Ordnance notified the Coast Artillery that fourteen Warner and Swasey azimuth instruments, Model 1910, would be sent to Fort Rosecrans for use in the new fire control stations. The position finder instrument in use at that time was the Swasey Depression Range Finder, Type A, Model 1910. [30]

Although the standard fire control system for the defenses of San Diego had not been completed by 1920, the Corps of Engineers turned over a substantial number of stations to the commanding officer that year:

| B 1/1 | and BC, primary and battery commander's station, Battery Whistler |

| B 2/1 | secondary station, Whistler |

| B 3/1 | tertiary station, Whistler |

| B 4/1 | base-end station, Whistler, North Island |

| B 1/2 | primary station, Battery John White |

| B 2/2 | and BC secondary and battery commander's station John White |

| B 3/2 | tertiary station, John White |

| B 4/2 | base-end station, John White, North Island |

| B 1/3 | primary station, Battery Wilkeson |

| B 2/3 | secondary station, Wilkeson, North Island |

| 8 1/4 | primary station, Battery Calef |

| B 2/4 | secondary station, Calef, North Island |

| C | fort commander's station |

| F 1/1 | first fire commander's station |

| F 1/2 | second fire commander's station |

| M1 | mine primary station meteorological station fire control switchboard room, located in Battery John White battery commander's station (BC) [31] |

San Diego's Endicott batteries had concentrated on defending the entrance channel. Only Battery Wilkeson could have participated in a major naval engagement. While batteries had been projected for Point Loma and elsewhere, they had not yet been funded. In 1913, Maj. William C. Davis wrote the Adjutant General of the Army outlining the deficiencies of the defenses. A modern naval power, with its new long-range fighting power and efficiency, could attack and maneuver in the area south of Coronado and far outclass Wilkeson's 10-inch guns. An enemy fleet off Ocean Beach could bombard and take in reverse all the fort's batteries and bombard downtown San Diego and all the inner harbor. [32]

In a similar vein the Los Angeles District Engineer described the defenses: "Only Battery Wilkeson is apt to participate in a naval engagement of serious magnitude, for the other batteries cover the mine fields and the immediate entrance to the harbor only." The weak point in the defenses, he said, was the west side of Point Loma where even enemy gunboats could approach unopposed: "There is no gun of any calibre now available to protect this side of the Point." Before the end of 1915, help was on the way. The commanding general of the Western Department learned that four 12-inch mortars, authorized at the last session of Congress, would be shipped from Fort Morgan in Mobile, Alabama. [33]

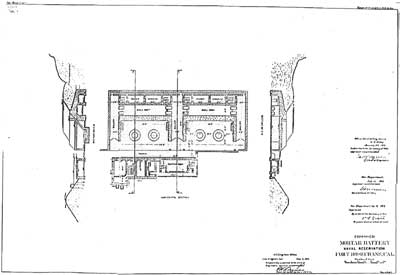

The Engineers began work on two mortar batteries, each having four mortars in two pits, at the end of 1915. Battery John White was constructed in a deep ravine (Power House Canyon) behind the post and Battery Whistler was constructed near the northern boundary of the reservation. The first was named in honor of Col. John Vassar White, a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy and a veteran of the Artillery Corps. Battery Whistler honored the memory of Col. Joseph Nelson Garland Whistler, an infantry officer who fought in both the Mexican and Civil Wars. Although the engineers completed construction in 1916, the mortars and their carriages were delayed in arriving. The mortars were not proof-fired until the end of 1918 and the batteries were officially transferred from the Engineers to the commanding officer of the Coast Defenses of San Diego in August 1919.

Engineers emplaced the mortars and carriages as follows:

Battery Whistler

| Mortars | Caliber | Model | Serial No. | Manufacturer | Mounted |

| Pit A, 1 | 12-inch | 1890M | 76 | Watervliet Arsenal | Dec. 31, 1917 |

| Pit A, 2 | 12-inch | 1890M | 85 | Watervliet Arsenal | Dec. 31, 1917 |

| Pit B, 1 | 12-inch | 1890M | 107 | Watervliet Arsenal | Dec. 31, 1917 |

| Pit B, 2 | 12-inch | 1890M | 127 | Watervliet Arsenal | Dec. 31, 1917 |

| Carriages | Model | Serial No. | Manufacturer |

| Pit A, 1 | 1896M | 186 | American Hoist & Derrick Company |

| Pit A, 2 | 1896M | 188 | American Hoist & Derrick Company |

| Pit B, 1 | 1896M | 189 | American Hoist & Derrick Company |

| Pit B, 2 | 1896M | 190 | American Hoist & Derrick Company |

Battery John White

| Mortars | Caliber | Model | Serial No. | Manufacturer | Mounted |

| Pit A, 1 | 12-inch | 1890M | 3 | BIF, Providence, Rhode Island | Dec. 31, 1917 |

| Pit A, 2 | 12-inch | 1890M | 27 | Bethlehem Iron | Dec. 31, 1917 |

| Pit B, 1 | 12-inch | 1890M | 9 | BIF, Providence Rhode Island | Dec. 31, 1917 |

| Pit B, 2 | 12-inch | 1890M | 4 | BIF, Providence, Rhode Island | Dec. 31, 1917 |

| Carriages | Model | Serial No. | Manufacturer |

| Pit A, 1 | 1896M | 76 | R. Poole & Son |

| Pit A, 2 | 1896M | 83 | R. Poole & Son |

| Pit B, 1 | 1896M | 56 | R. Poole & Son |

| Pit B, 2 | 1896M | 87 | R. Poole & Son [34] |

At the same time considerable planning took place for adding six 6-inch rapid-fire guns to the harbor's defenses: two at Billy Goat Point on the east side of the peninsula, at elevation 99 feet; two at the south end of Point Loma, one-quarter mile northwest of the new lighthouse, elevation 78 feet; and two on the western side of Point Loma near the north boundary, elevation 128 feet. The estimated cost of the three batteries and the necessary fire control stations came to a grand total of $842,000. The Secretary of War approved the project in February 1918 and directed that the cost figure be included in the 1920 defense estimates. The Congress did not make funds available and many years passed before 6-inch guns again were considered for San Diego. [35]

Lt. Col. W. F. Hase inspected the Fort Rosecrans batteries early in 1918 and discovered that the sea was undermining 3-inch Battery James Meed at Fort Pio Pico. His recommendation that the guns be dismounted and the battery abandoned was approved. Since the 5-inch guns at Battery McGrath had gone to war, the Engineers modified its emplacements and mounted Meed's guns in their stead in May 1919. [36]

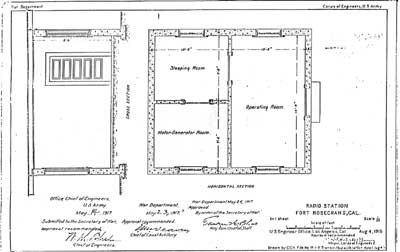

World War I stimulated several developments in San Diego coastal defenses. Among them was the 1917 authorization to construct an army radio station at Fort Rosecrans. Engineers located it 1,000 feet northwest of the old lighthouse with the towers between the two. The building cost approximately $2,500 and the towers $1,150. It was operational in 1918 but for some reason it was not turned over to the Coast Artillery until 1919. This did not prevent a "very zealous and enthusiastic radio instructor, Lt. MacFadden" from placing the apparatus in service prematurely. The district engineer demanded an explanation and got an apology. A couple of months later, a naval lieutenant officially tuned in the equipment and the artillery engineer took charge of the station. [37]

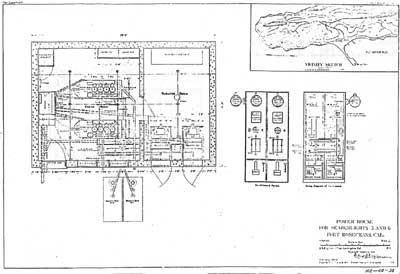

The Taft Board's recommendations for batteries of coastal searchlights became a reality on Point Loma between 1918 and 1919. The Chief of Engineers approved plans for eight 60-inch searchlights arranged in four batteries:

Searchlights 1 and 2 - near the base of a hill on land in the northwest part of the reservation, land that was recently transferred from the naval reservation, at elevations of 190 feet and 97 feet respectively. Both to be new lights on elevating lifts. Power house nearby in a ravine.

Searchlights 3 and 4 - near the extremity of Point Loma, elevations 97 and 285 feet. Number 3 to be in upright shelter and mounted on a track (a reconstruction of an existing installation). Number 4, a new light on an elevating lift. The power house to be a reconstruction of existing house.

Searchlights 5 and 6 - near base of a hill on southeast portion of Point Loma at elevations 218 and 144 feet respectively. Both to be new lights. Number 5 to run on a track between operating position and naturally protected aboveground shelter. Number 6 to be on elevating lift. Power house in a ravine affording partial protection between the two lights.

Searchlights 7 and 8 - on a sand spit at Fort Pio Pico. One is the existing 60-inch light, the other, new. Power house to have artificial protection. Lights to be on tilting towers with a sand parapet in front.

The plans called for roads, "mere graded roads without surfacing," to the power house for searchlights 1 and 2 and for searchlights 5 and 6. Because the site selected for Searchlight 6 potentially interfered with the proposed 6-inch battery on Billy Goat Point, it was constructed just to the west at an elevation of 210 feet. Four 25 kw, D.C. generation sets were purchased for searchlights 1, 2, 5, and 6. The Engineers completed shelters for these four searchlights in April 1919, at an approximate cost of those shelters having elevators of $2,300 each. All shelters were reinforced concrete; those above ground had steel doors; and those underground had sliding steel roofs. [38]

|

| Shelter for coastal searchlight no. 5, constructed in 1920. Located on Bayside Trail, Cabrillo National Monument. Photo by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1920. Courtesy of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Los Angeles District. |

|

| Searchlight Number 5 in operating position, 1920. Searchlight Number 6 is located directly behind and to the north of this searchlight. Photo by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1920. Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Los Angeles District. |

|

| Searchlight Number 6 in operating position, 1920. Photo by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1920. Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Los Angeles District. |

|

| Searchlight shelter Number 6 today. Portion of rails still in place. Located on Bayside Trail, Cabrillo National Monument. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

|

| Searchlight Number 5 in operating position. Photo by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1920. Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Los Angeles District. |

|

| Old Point Loma Lighthouse between 1912 and 1914. The wife of an army noncommissioned officer, who was living in the structure, wrote that since the photo was taken a porch had been built along the front of the building. She also said there was a store where the window was broken and she had her kitchen where the curtains show. Photo courtesy of Maj. Gen. George Ruhlen, U.S.A. Ret. |

|

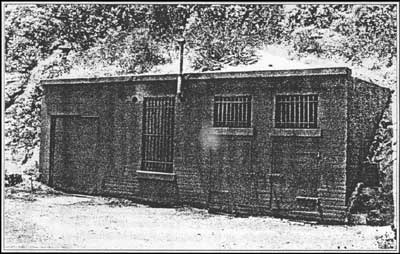

| Fort Rosecrans' first army radio station, built in 1918. This structure later served at the National Park Service's early superintendent's office. It is now a storage building. Photo by E. Thompson. |

|

| Roof of searchlight shelter Number 15. This oceanside searchlight is found west of Gatchell Road at Cabrillo National Monument. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

|

| Sixty-inch coastal searchlight. Three of these were mounted within today's Cabrillo National Monument: Nos. 5, 6, and 15. Photo courtesy of National Archives, Los Angeles Branch, RG 77, OCE, Box number lost. |

|

| Power plant for searchlights 5 and 6 as it looks today. Located on Bayside Trail, Cabrillo National Monument. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

|

| Power plant erected in 1920 on the Bayside Trail to serve coastal searchlights 5 and 6. Photo by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1920. Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Los Angeles District. |

F. Wartime Fort Rosecrans,

1917-1918

As the United States moved toward war in 1917, the Navy and the Army clashed in an event involving Fort Rosecrans. On January 15 the captain of USS Pueblo, the flagship of the U.S. Pacific Fleet Reserve Force, wrote a sharply worded communication to the commanding officer of Fort Rosecrans. He began by quoting from Naval Instructions as to what the senior naval officer on board a naval vessel should do when entering an American harbor: communicate with the outer group of fortifications and identify himself, where he came from, and the length of his stay. A similar exchange will be made upon leaving a harbor. He said that USS Pueblo called Fort Rosecrans by radio at 9:15 and 9:20 a.m. that day. Since Fort Rosecrans' radio did not reply (Fort Rosecrans did not have a radio station at that time), the message was sent via the Point Loma Naval Radio. At 10:30 a.m. Pueblo came within visual signal distance of Fort Rosecrans and signaled with the wig-wag flag until 10:45. Again, the call was not acknowledged. The post commander, Lt. Col. G. T. Patterson, replied in writing a few days later briefly stating that the incidents were being investigated and the appropriate action would be taken. He deeply regretted the affair. The record fails to show the outcome of the investigation. [39]

Once the United States was at war, the Army and the Navy cooperated fully. The Secretary of the Navy notified the Army that for the duration of the war, naval ships would not radio coastal defenses because recognition signals were now in effect and, also, it was necessary to reduce radio communication to a minimum. Later that year, Fort Rosecrans was informed to exchange recognition signals no longer unless the identity of the approaching vessel was in doubt. It is not known if the fort had to check any identities, but it was notified in 1917 that an enemy raider had been sighted in the Pacific. [40]

During the war, three coast artillery companies, the 4th, 18th, and 15th, garrisoned Fort Rosecrans. Elsewhere in the San Diego area were the 21st Infantry Regiment and the 14th Aero Squadron, Training. In the summer of 1917, the U. S. Attorney in Los Angeles was ordered to San Diego to arrest and detain enemy aliens. Among the half-dozen or so people arrested were three army privates, all from Rockwell Field: Wilhelm F. Streibart, Erich Rosenhagen, and Johannes W. Grief. They were detained at Fort Rosecrans before being sent to the War Prison Barracks, Fort Douglas, Utah. During that brief period at the fort, Private Streibart was court martialed for assaulting a guard."

One of the important activities at the post during the war was the organizing of antiaircraft batteries for overseas duty. These men were not trained in antiaircraft fire simply because Fort Rosecrans had no antiaircraft guns, except for machine guns. In November 1917, the first battery, two officers and sixty-two men from personnel of the Coast Defense Command, left Fort Rosecrans for France. Early in 1918, Batteries A and B, 2nd Antiaircraft Battalion, were organized at the post. Other units organized there and sent overseas included the 65th Coast Artillery and the 54th Ammunition Train. [42]

Before the war ended, the commanding officers of the Army and Navy shore stations held a conference in San Diego to discuss the defense of the harbor. Col. James R. Pourie, commanding the Coastal Defenses, and Maj. W. B. Burwell, commanding the Signal Corps Aviation School at Rockwell Field, informed their naval counterparts of steps taken by the Army to defend the harbor. Burwell said that his airplanes could be used for observation purposes, provided they remained within gliding distance of land. Pourie noted that Battery Fetterman's two 3-inch guns were held in readiness for immediate service at all times, and at Battery James Meed, which had not yet been abandoned, a gun detachment was held in readiness at all times. Although the new coastal searchlight project was not yet in place, four searchlights (one 30-inch, one 36-inch, and two 60-inch) were ready for instant service. An operator stood duty at the new radio station from 6:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. No submarine mines had been laid but they could be if necessary. Finally, Pourie said, "Constant outlook is kept from Signal Station at old Lighthouse." [43]

|

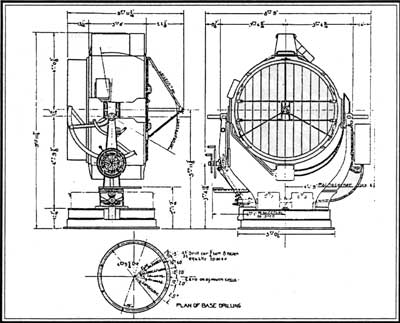

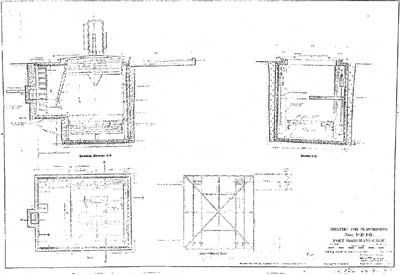

| Plans for Battery John White, four 12-inch mortars, Fort Rosecrans. The battery is now in the U.S. Naval Reservation, Point Loma. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| Fort Rosecrans' first radio station. Maj. Gen. Tasker H. Bliss approved these plans. Earlier he had reviewed the troops at Fort Rosecrans. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| Powerhouse for Coastal Searchlights 5 and 6, on the Bayside Trail. National Archives, RG 77, Fortifications File, Dr. 102-40-38. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| Plans for the underground shelter for Searchlight No. 6, 1918. Located on the Bayside Trail within Cabrillo National Monument. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

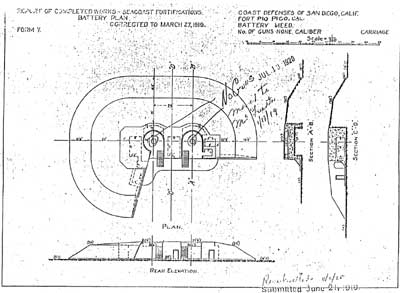

| Report of completed works, seacoast fortifications, battery plan: Fort Pio Pico Battery Meed. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

cabr/guns-san-diego/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 19-Jan-2005