|

CABRILLO

The Guns of San Diego Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER 5:

INTERLUDE, 1920-1935

In 1925 the Coast Defenses of San Diego were renamed the Harbor Defenses of San Diego.

Following the war, defense activities at San Diego declined rapidly. Soon, the garrison at Fort Rosecrans diminished to one company of Coast Artillery and an occasional detachment from another arm. In 1931 the Headquarters and Headquarters Company, Sixth Brigade, and a detachment of the 11th Cavalry Regiment were temporarily at the post, along with Battery D, 3rd Coast Artillery, the permanent garrison. The following year, a 35-man detachment of the 9th Cavalry Regiment (Black) was temporarily at the post in connection with the Equestrian Olympic Team. At one point the Army considered disposing of the fort but quickly changed its mind. In March 1932 Headquarters, 9th Coast Artillery District, San Francisco, stated that Fort Rosecrans had been withdrawn from the list of reservations to be disposed of and it was retained in entirety for military purposes. [1]

The fort came to the attention of scientists in 1923 when Point Loma was the most suitable and most accessible place in the United States to make observations of a solar eclipse. Dr. Walter S. Adams, Acting Director of the Mount Wilson Observatory, sent workmen to construct concrete foundations and pillars for mounting observation instruments. Among the visitors were John C. Merriam, President, Carnegie Institution, Washington, D.C.; S.A. Mitchell, Director, Leander McCormick Observatory, University of Virginia; and a French mission under C. LeMorvaux, Astronomer at the Paris Observatory. September 10 brought bad weather and the scientists were disappointed, yet they praised the Coast Artillery effusively for its hospitality and cooperation. [2]

|

| The post of Fort Rosecrans, 1937; (a) U.S. Coast Guard Station; (b) Battery Fetterman, 3-inch guns; (c) Batteries Wilkeson and Calef, 10-inch guns; (d) Battery McGrath, 3-inch guns (formerly 5-inch); (e) Battery White, 12-inch mortars. Photo courtesy of San Diego Historical Society — Ticor Collection. |

In 1933 the War Department transferred the 1/2-acre Cabrillo National Monument to the Department of the Interior. When Superintendent John R. White, Sequoia National Park, made his first visit to the monument in 1934, he held meetings with interested citizens to discuss the monument's future. Lt. Col. George Ruhlen, then commanding Fort Rosecrans, attended the meetings. Greatly interested in San Diego's history, Ruhlen proposed a resolution to make the historic lighthouse, the principal structure at the monument, a permanent feature. This resolution was passed unanimously. Ruhlen had additional plans for Point Loma. He wrote a friend that he had procured several thousand Monterey cypress and Torrey pines from the County and City of San Diego and they would be planted all along the peninsula. [3]

San Diego celebrated 1935 with the California-Pacific International Exposition. Rosecrans' tiny garrison could not supply the personnel that it had at the Panama-California International Exposition in 1915, but it did what it could. In July a reporter from the San Diego Union visited the fort and found it "dressed up" for the exposition and open daily to visitors. A detachment of 100 soldiers was coming to help the 48 officers and men at the fort. Each Tuesday and Thursday, at 2 p. m., the artillerymen would give a special demonstration of loading one of the 10-inch disappearing guns. [4]

While life at Fort Rosecrans was relatively uneventful in the 1920s and early 1930s, its existence was not forgotten in the offices of the Engineers and Coast Artillery in the War Department. The state of San Diego's harbor defenses came to the attention of the National Harbor Defense Board in 1932. The Chief of Coast Artillery informed the Board that some railroad guns, all of which were then stored on the Atlantic seaboard, should be moved to the Pacific Coast as soon as possible, because such transportation would take an extensive period of time. The Board's examination of San Diego showed that the five existing batteries were inadequate both in range and volume. It concluded that new seacoast guns had to be added, at which time the 10-inch guns could be removed. The new project called for two 8-inch (Navy) guns on barbette carriages, two 8-inch (Navy) guns on railway mounts, and eight 155mm guns in two batteries. [5]

|

| Dignitaries gathered to celebrate the completion of a paved road to the Old Point Loma Lighthouse, 1934. Col. George Ruhlen, commanding Fort Rosecrans and dedicated to Point Loma's history, is in uniform. To his left is Assistant Superintendent Daniel J. Tobin, Sequoia National Park. Photo courtesy of Maj. Gen. George Ruhlen, U.S.A. Ret. |

|

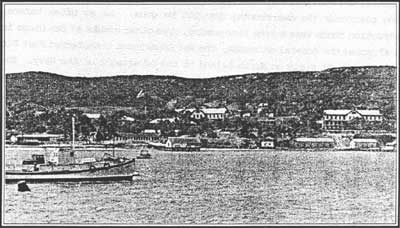

| Fort Rosecrans from Ballast Point, 1933. Photo by Col. George Ruhlen, U.S.A. Photo courtesy of Maj. Gen. George Ruhlen, U.S.A. Ret. |

A local board, composed of Engineer and Coast Artillery officers, met at San Diego in 1933 to select sites for the new weapons. For the 8-inch battery it selected a site near Battery Whistler. The board chose a site for one battery of 155mm guns at Point Loma near the new lighthouse, and recommended a location 1,500 yards south of Coronado Heights and west of south San Diego, on the former Camp Hearn site, for the other 155mm battery, which was never built. The board identified sites for the railroad guns but these weapons were not destined to arrive in San Diego. It also chose locations for two 3-inch antiaircraft guns which had been added to the project, one 100 yards south of the old lighthouse, the other north of Whistler near the boundary. [6]

In 1935 the War Department notified the Los Angeles District Engineer that it seemed probable emergency relief funds would become available for defense projects in the harbor defenses of Los Angeles and San Diego. For Fort Rosecrans it directed the engineers to prepare plans for six 3-inch antiaircraft gun blocks, the 8-inch fixed battery and its four fire control stations, and four firing platforms (Panama mounts) for 155mm guns. As so often before, construction funds were a long time coming. Two other events at San Diego in 1935 affected the coastal defenses. The War Department transferred Fort Pio Pico and Rockwell Field on North Island to the Department of the Navy. The commanding officer at Fort Rosecrans, Lt. Col. Edward L. Kelly, announced that two of the mortars would be fired on July 22, the first time in eleven years. This practice required eighty-five officers and men to fire twenty-four projectiles 18,000 feet into the air toward a target eight miles away. Things were beginning to stir at Fort Rosecrans. [7]

|

| The road to the lighthouse in 1934, prior to its reconstruction and paving. Cabrillo National Monument at that time consisted of the lighthouse and the road around it. Photo courtesy of Maj. Gen. George Ruhlen, U.S.A. Ret. |

|

| Old Point Loma Lighthouse, early 1920s. The building was used as a residence by a sergeant from Ft. Rosecrans. Photo courtesy of Cabrillo National Monument. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

cabr/guns-san-diego/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 19-Jan-2005