|

CABRILLO

The Guns of San Diego Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER 6:

MODERNIZATION, 1936-1941

A. Annexes to Harbor Defense Project, 1936

San Diego Harbor's defense project was completely overhauled in 1936. A series of "annexes" outlined the organization of the seacoast guns, fire control installations, searchlights, antiaircraft gun defense, and supporting aircraft. The defenses were to be organized into three groups, a separate battery of seacoast armament, and one group of antiaircraft weapons:

| Group 1: | Batteries Whistler and John White, 12-inch mortars. Installed. Maximum range, 14,650 yards. |

| Group 2: | Battery Strong, 8-inch guns to be installed. Maximum range, 33,000 yards. Battery Point Loma, 155mm guns to be installed. Range 17,400 yards. |

| Separate battery: | Battery McGrath, 3-inch guns. Installed. Maximum range 8,700 yards. |

| Group 3: | Antiaircraft group. Two battalions. Fort Rosecrans: Two batteries, each having three 3-inch guns. Vertical range, 9,300 yards. Horizontal range, 10,550 yards. Thirty-six antiaircraft (AA) guns, .50 caliber. Seven AA searchlights, portable. All were to be installed but were never actually emplaced. South San Diego: One battery of three 3-inch AA guns, mobile. Vertical range, 7,500 yards. Horizontal range, 7,700 yards. Twelve AA machine guns, .50 caliber. Six AA searchlights, portable. All were to be installed but were never actually emplaced. |

| Group 4: | Railroad battery of two 8-inch guns. Maximum range, 33,000 yards. A battery of four 155mm guns, mobile. Maximum range 17,400 yards. Four portable coastal searchlights. All were to be installed but were never actually emplaced. |

Batteries Wilkeson and Calef were to be retained temporarily but would be abandoned when the 8-inch railroad guns arrived in San Diego. The long-range modernization project called for the additional construction of two batteries of 16-inch guns (construction nos. 126 and 134) and three batteries of rapid-fire 6-inch guns (construction nos. 237, 238, and 239). When these five batteries were armed, the Coast Artillery would abandon Batteries Whistler, John White, Wilkeson, and Calef, along with the 155mm and 8-inch railroad guns. [1]

Annex B concerned fire control installations. It noted that the fire control switchboard room was in the southeast corner of Battery John White. A second one would be located near the Group 4 station at Coronado Heights. A bombproof room in the west end of Battery Wilkeson would become home to the harbor defense radio transmitting station, while the receiving station would be put in the old mine station 1,200 yards to the south. Base-end stations were scheduled for Torrey Pines State Park (not built), Soledad Mountain, and Ocean Beach north of Point Loma (not built); at Fort Rosecrans; and at North Island, Silver Strand, Coronado Heights, and near the Mexican border to the south. When completed, the fire control system would be a complex undertaking:

Batteries Whistler (tactical no. 1) and John White (2):

Double fire control stations: Battery commanders (BC) stations and base-end stations B2S2, to be constructed near the old lighthouse, elevation 380 feet.

Emergency BCs and base-end stations B1S1 to be constructed on Point Loma, elevation 224 feet.

Base-end stations B3S3, existing stations on North Island, elevation 50 feet. Base-end stations B4S4, to be built on Ocean Beach, elevation 60 feet (not built).

Battery Strong (tactical no. 3; not yet constructed)

BC and B1S1, to be constructed 200 yards south of Whistler, elevation 421 feet

B2S2, the present commanding officer's station on Point Loma, elevation 350 feet

B3S3, a 100-foot steel tower to be erected on Silver Strand

B4S4 a 100-foot steel tower to be erected at Coronado Heights

B5S5, to be constructed near Mexican border, elevation 290 feet

B6S6, to be constructed on Ocean Beach, elevation 60 feet (not built)

B7S7, to be constructed on Soledad Mountain, elevation 290 feet

B8S8, to be erected at Torrey Pines State Park (not built)

Battery Point Loma (tactical no. 4; not yet constructed)

BC Station, to be constructed 150 yards east of the battery, elevation 250 feet

B1S1, to be constructed near the old lighthouse, elevation 253 feet

Coincidence range finder (CRF), at the battery, elevation 100 feet

Plotting room, in a plotting trailer, near the battery.

Battery McGrath (tactical no. 5)

BC station and CRF, 150 yards south of and above the battery, elevation 100 feet.

Many of the depression position finders (DPF, M-1-4 and other models), azimuth instruments (M1900 and M1910), and observing telescopes (M1908) were already on hand for these fire control stations. The large number of base-end stations required for the long-range guns of Battery Strong was a marked contrast to Battery McGrath's single BC station.

The center of operations was the Harbor Defense Command Post (HDCP). This bombproof structure had a 12-foot by 12-foot observation station. Covered stairs led from it down to two underground rooms, one measuring 15 feet by 20 feet and containing telephones and charts, the other 20-foot by 20-foot space serving as the antiaircraft message center. Connected to the HDCP were fire control stations for Group 2 and the Group commanders. Before long a number of changes occurred for the HDCP which will be discussed farther on.

In addition to the eight coastal searchlights already installed at Fort Rosecrans and North Island, six portable searchlights were proposed for illuminating the extreme north ranges of the new armament. These sites ranged from Ocean Beach to Torrey Pines. Another four portable searchlights would be added in the south, at Coronado Heights and near the Mexican border. As a result, the two searchlight shelters now within Cabrillo National Monument on the Bayside Trail, which were originally 5 (HS5) and 6 (HS7) now became searchlights 11 and 12. [2] (By the end of World War II searchlights 1 through 27 were located at 14 sites from Cardiff to the border.)

|

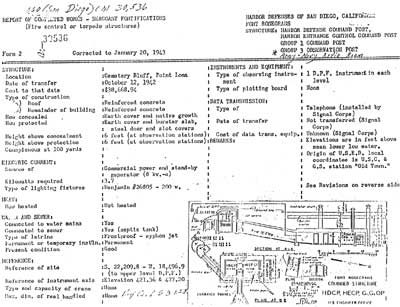

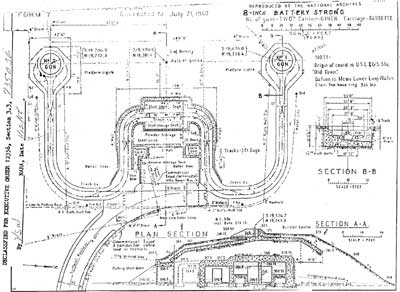

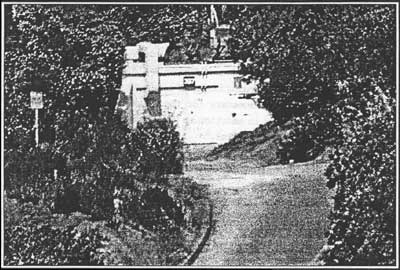

| Upper: Battery commander's station for Battery Strong. Lower: Base-end station B1/2 S1/2 for Battery Strong. Currently located on Naval Ocean Systems Center property. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

|

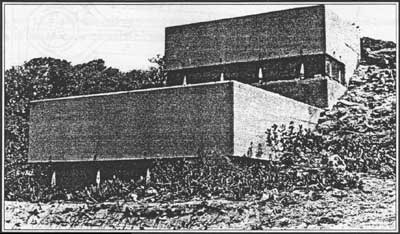

| Upper: Harbor Entrance Control Post. Lower: Harbor Defense Control Post. Structure can easily be seen from the northwest section of Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

|

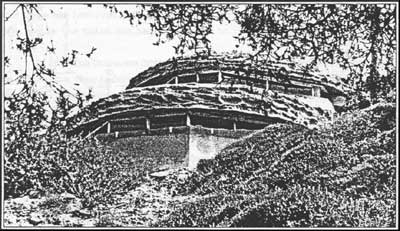

| Battery Strong, two 8-inch guns, Fort Rosecrans. The magazines were casemated with earth and concrete, but not the guns. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Although the Army had transferred Rockwell Field to the Navy, the Army retained the right to use the landing field. The annexes estimated that a flight of three aircraft would be necessary for the observation of fire for the long-range guns. These were in addition to whatever aircraft were necessary f or reconnaissance and border patrol. [3]

B. Battery Strong

Construction began on Battery Strong early in 1937. The engineers selected a site on the ocean side of Point Loma toward the north end of the reservation. Barely had work got underway when U.S. Congressman Edouard V. Izac learned that several workmen on the project complained they were underpaid, their supervisors were incompetent, the work quality was poor, and there were no safety precautions. Izac queried Secretary of War Harry H. Woodring as to the circumstances. Los Angeles District Engineer Theodore Wyman, Jr., informed Washington that the complaints were unfounded. Two of the three men involved had performed unsatisfactorily and were no longer on the job, while the third man had been about to be promoted when he quit. [4]

In 1937 the Ordnance Office notified the Chief of Engineers that it would be at least a year before the 8-inch Navy, 45 caliber guns would be ready for shipment. In order to obtain the ballistics required it was necessary to redesign the powder chamber, which meant relining the guns. Also, ordnance would not complete the manufacture of the two barbette carriages until May 1938. The Watertown Arsenal supplied some statistics for an 8-inch. gun on a barbette carriage:

| Gun, recoil band, and cradle complete | 67,000 lbs. |

| Racer, side frames, and transoms | 22,000 |

| Distance ring | 1,000 |

| Base plate | 9,000 |

| Miscellaneous | 4,000 |

| Total | 103,000 lbs. [5] |

Long before the 8-inch guns arrived at Fort Rosecrans, the Adjutant General announced that the battery was named in honor of the late Maj. Gen. Frederick S. Strong, who graduated from West Point in 1880 and was appointed a lieutenant in the 4th Artillery. From 1916 to 1917, Brig. Gen. Strong commanded the Department of Hawaii. Promoted to major general in 1917, he organized the 40th Division (California National Guard) at Camp Kearny, California and took it to France in 1918. General Strong died in 1935 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. [6]

|

| Battery Strong's magazine today. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

|

| Entrance to Battery Ashburn today. The 16-inch gun tube was mounted and dismounted through this door. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

While waiting for the guns, the engineers carried out experiments in camouflage at the battery, without any great degree of success. The Coast Artillery became anxious too, stressing the fact that the navy was increasing its activities at San Diego and the battery was "imperative" for the defense. Finally, in August 1940 the Ordnance Department announced that the carriages were completed and the weapons would be proof-fired at Aberdeen Proving Ground. All good things take time and, in April 1941, the Los Angeles District Engineer reported the mounting of the armament at Battery Strong completed:

| Guns | Caliber | Model | Serial No. | Manufacturer | Mounted |

| 1 | 8-inch | 3A2 | 193L2 | Watervliet Arsenal | April 1941 |

| 2 | 8-inch | 3A2 | 195L2 | Watervliet Arsenal | April 1941 |

| Carriages | Model | Serial No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 barbette | M-1 | 2 | Watertown Arsenal |

| 2 barbette | M-1 | 1 | Watertown Arsenal [7] |

C. Batteries for 155mm Guns

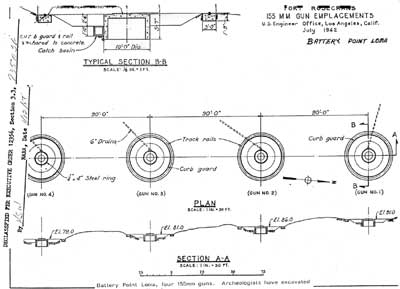

The 1936 Annex A called for two 155mm batteries of four guns each, one battery at Fort Rosecrans (later called Battery Point Loma) and one immediately north of Imperial Beach and about 2000 yards south of Coronado Heights (but it was never emplaced). The 155mm gun was a modification of the French "Grande Puissance Filloux" (GPF), a tractor-drawn gun developed in World War I. Early models had a range of 17,000 yards. Battery Point Loma's guns had a distance between gun centers of thirty yards, and each was to be emplaced on a Panama mount. The battery was situated 300 yards north of the new lighthouse at Point Loma. The first plans called for only a 180-degree traverse emplacement. When the post commander protested that in order to obtain full tactical advantage of the emplacements, 360-degree platforms should be installed, the War Department agreed. But many months passed between the arrival of the guns and the availability of funds for construction of the platforms. The 1936 cost estimates for the battery were:

| Preparation of site and installation of power plant | $5,000 |

| Four gun platforms | 6,000 |

| Concrete magazine for projectiles | 5,000 |

| Concrete magazine for propelling charges | 8,500 |

| Battery commander's station | 2,000 |

| Road to battery | 200 |

| Protective wire fence | 3,000 |

| Contingency | 1,000 |

| Four sights | 14,000 |

Total cost estimated at $44,700, of which $14,000 was ordnance, $19,000 was engineer material, and $11,700 was engineer labor. In addition, a plotting trailer would be provided. Dugouts would house first aid, restroom, and latrines. [8]

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the U. S. Army hastily emplaced 155mm guns along the Pacific Coast, including Alaska and the Aleutians, to supplement the fixed harbor defenses. But at San Diego the Coast Artillery Corps was eager to acquire these batteries long before Pearl Harbor. The arming of Battery Strong, as has been seen, was to take four years. Besides the existing batteries of Whistler and John White, Battery Point Loma was much needed during the interim to cover the water areas to the west and northwest. Its guns (and those for Battery Imperial) reached Fort Rosecrans on June 14, 1939. The guns were emplaced but without platforms, thus their traverse was limited to sixty degrees.

A year later, Col. P. H. Ottosen, commanding San Diego's harbor defenses, requested construction of the platforms. He said that the ammunition was on hand and the sights and mounts (eight sights, quadrant Model 1918, and eight telescopic panoramic sights M6) were about to arrive. He added that until the guns for Battery Strong arrived, the 155mm guns were the only means of effective fire against the types of naval ships normally used in raids. If the $44,700 were not available, he would settle for $6,000 in order to build the platforms immediately. [9]

The War Department turned down the request for funds on the grounds that the 155mm guns would be removed when the proposed 6-inch batteries were constructed. Ottosen, supported by Lt. Gen. John L. Dewitt in San Francisco, argued that he would need both the 6-inch and the 155mm works. Washington finally relented, but approved only $6,000 for the four mounts. [10]

The Los Angeles District Engineer rejected the first bids for constructing the Panama mounts, in March 1941, and readvertised. The second attempt fared no better. The low bid was for $7,935; the government's estimate, $6,576. The engineers decided to begin the work themselves immediately with hired labor. While Battery Point Loma was in full operation by September 1941, the Corps of Engineers did not get around to transferring it officially until April 28, 1942. [11]

Battery Point Loma continued to serve through the early months of the war. Then, at the end of 1942 the decision was made to add 90mm anti-motor torpedo boat (AMTB) batteries to the harbor defense. At this time, Battery Point Loma was an anti-submarine battery. Should 90mm AMTB guns be installed, they would have to assume the anti-submarine mission as well as their own, and Battery Point Loma would be put out of commission. The battery's fate was debated for several more months; in the end a four-gun, 90mm AMTB battery was constructed in front of Battery Point Loma. No date has been found for the dismantling of the 155mm guns. It probably was mid-1943 or later. The emplacements themselves continued to be listed in reports. Indeed, they remain at Cabrillo National Monument and are designated HS14 [12] Battery Point Loma replaced by 6-inch Battery Humphreys in 1943.

Battery Imperial's history was quite similar to Point Loma's. The 1936 Annexes had called for the four 155mm guns to be retained at Fort Rosecrans until an "incident of emergency." The emergency came and, on December 9, 1941, they were moved to their permanent position directly north of Imperial Beach on the Coronado Heights Military Reservation, later named Fort Emory. However, this was not the location proposed in the 1936 project. In contrast to the concrete magazines at Point Loma, Imperial's dugouts were splinterproof, earth-covered dugouts of board and timber. As with the other 155s, artillerymen undoubtedly manned Imperial's guns long before the District Engineer got around to transferring them "for the use and care of troops," October 24, 1942. Battery Imperial gave way to 6-inch Battery Grant in 1943. [13]

D. The Build-up Continued,

1939-1941

Although the 1936 Annexes called for two battalions of antiaircraft artillery, the 3-inch guns were slow in coming to San Diego. In 1937, however, Fort Rosecrans carried out antiaircraft gun practice with machine guns. The San Diego Union announced that air and surface craft must stay clear of the area west of Point Loma between 9 and 11 a. m., each Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday from August 30 to September 30. The danger area, it said, was a semicircle with a radius of 6,000 feet horizontal and 12,000 feet altitude with a center point 1,000 yards south of the radio towers. The results of this practice have not been determined. [14]

Fort Rosecrans looked forward to acquiring 3-inch AA guns, however. In the spring of 1939, it requested permission to demolish the 3-inch coastal Battery Fetterman at Ballast Point. It was no longer in the defense project and its magazines were unfit for storage. The commander of the harbor defenses wished to use the site for the erection of sheds to protect 3-inch antiaircraft guns, their equipment, and the additional searchlights authorized for the harbor. The War Department was quick to approve. The demolition was completed on May 28, 1940. [15]

With Europe at war in 1939, a build-up of strength at America's harbors was a natural response. Inspectors-general visiting Fort Rosecrans that year noted the presence of the naval destroyer base at San Diego and recommended the garrison be increased to two batteries (6 officers and 233 enlisted men) and that a housing program be initiated. An inspector-general in 1940 remarked on the rapidly expanding airplane manufacturing industry in San Diego and warned that the army was not prepared for the industry's security from domestic disturbance and sabotage. Col. Ottosen reported in September 1940 that units of the 19th Coast Artillery Regiment were being activated at Fort Rosecrans and others would be formed in the near future. He requested additional funds to train the men at Batteries Calef and Wilkeson since the guns for Battery Strong had not yet arrived. Then, in October 1940, the construction quartermaster received orders to erect temporary buildings for an increase in enlisted strength of 2,022 men. To take care of the increase in land use, a dredging project in San Diego Harbor in 1940 resulted in adding about twenty acres of fill to the reservation at Ballast Point to provide a level space for drilling. [16]

The local Harbor Defense Board met in April 1940 to consider the future of the 10-inch Batteries Wilkeson and Calef. While already considered outmoded, they were the only large guns in operation at San Diego at that time. The board recommended they be retained as one battery and made part of the permanent fortifications. It noted that these guns were still valuable for the defense of the outer channel area, particularly in the absence of a submarine mine project. The War Department approved and the four guns were once again one battery, this time called Calef-Wilkeson. [17]

During the months before the United States entry into the war, funds became available for the construction of additional fire control stations particularly for the proposed 16-inch and 6-inch batteries, and the enlargement of existing stations. Of particular concern were the Harbor Defense Command Post (HDCP), the Harbor Entrance Control Post (HECP), and the Navy's signal station.

E. HDCP, HECP, and Signal

Station

Engineers constructed the Harbor Defense Command Post adjacent to what later became the northwest corner of Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in west Fort Rosecrans. The large bombproof structure was buried under a covering of earth with two large concrete and steel observation stations facing the sea. As first constructed, it contained the harbor defense operation post and command post, the harbor defense intelligence center, Group One command post, Group Three command post, and the antiaircraft intelligence center. It became operational in 1941.

In the spring of 1941, the Army and Navy got together to determine a site for the Harbor Entrance Control Post. Gen. George C. Marshall and Adm. H. R. "Dolly" Stark had announced jointly that an officer of the Army and of the Navy continuously manned a HECP. The ideal location was one that commanded a complete view of the harbor approaches and the harbor itself. The ideal housing was in the HDCP. At San Diego, one site that commanded the harbor and its entrance was the old lighthouse on Cabrillo National Monument. But in a March meeting between Col. Ottosen, CAC, and Capt. L. E. Gunther, USN, the decision was reached to place the HECP in the HDCP and not in the old lighthouse because it did not have sufficient room. Three weeks later, the same officers rejected the HDCP and decided on a separate building to be constructed 100 yards south of the old lighthouse. On May 17, 1941, the Secretary of the Interior issued a special use permit to the War Department that turned over Cabrillo National Monument for military use.

Despite the decisions reached earlier, the Los Angeles District Engineer announced in July that he had designed a signal mast in connection with the conversion of the old lighthouse into a HECP and a signal station. He estimated that alterations to the lighthouse would cost $1,500; the signal mast, $3,100; a generator, $500; and office furniture for the lighthouse, $1,500.

But the issue was not yet a closed subject. In September the Western Defense Command in San Francisco desired a reconsideration of the project, with the view of placing the HECP in the HDCP and using the lighthouse as a watch tower and signal station. The reasons for rejecting the lighthouse were that it was not bombproof, too small, its use would duplicate communication systems already in the HDCP, and it would cause dangerous exposure of important personnel.

Thus ended the debate. The HECP moved into that portion of the HDCP that had been occupied by Group Three command post and the antiaircraft intelligence center. These latter functions eventually moved to the old mine casemate near Ballast Point. The lighthouse now became the signal station and was equipped with a signaling searchlight, an observation instrument, and telephone communication to Battery McGrath, the alert battery, and the alert searchlight. A temporary signal mast was installed along with a set of flags for visual signaling to surface craft. [18]

F. Modernization Program, 1941

By September 1940, the Nazis had overrun Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. By mid-1941, German troops had invaded Russia. The Battle of Britain had been fought and the Battle of the Atlantic was underway. In North Africa, Gen. Erwin Rommel had begun a counteroffensive, driving the British back into Egypt. Japan had occupied French Indo-China and Japanese credits in the United States had been frozen. It is not a surprise that the local board of the Harbor Defenses of San Diego chose that time to update the modernization project.

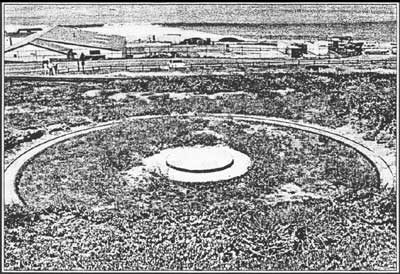

A year earlier, the War Department's Harbor Defense Board came forth with a new report that recommended the adoption of the 16-inch gun as the primary weapon and the 6-inch gun as the secondary weapon in seacoast armament. The board proposed for national defense the construction of twenty-seven new 16-inch two-gun batteries and fifty new 6-inch two-gun barbette batteries of a new design having a 15-mile range. The general staff approved this report in September 1940. Now, the local board applied the new program to San Diego's defenses. As has been noted, two 16-inch and three 6-inch batteries had been projected for the harbor. [19]

The board first prepared a list of the existing and authorized seacoast batteries that would remain when the modernization program was completed:

| Tactical No. |

Battery | Caliber | Number of Guns | Location |

| 1. | 237 (Woodward) | 6-inch | 2 | North Fort Rosecrans |

| 2. | Strong | 8-inch | 2 | North Fort Rosecrans |

| 3. | 126 (Ashburn) | 16-inch | 2 | West Fort Rosecrans |

| 4. | 238 (Humphreys) | 6-inch | 2 | South Fort Rosecrans |

| 5. | McGrath | 3-inch | 2 | East Fort Rosecrans |

| 6. | 134 | 16-inch | 2 | Coronado Heights |

| 7. | 239 (Grant) | 6-inch | 2 | Coronado Heights |

The 16-inch batteries were to be casemated and the 6-inch guns would be protected by steel shields. The completion of Battery Strong had powerfully reinforced the harbor in the north. Now Battery 238 (Humphreys) received construction priority so as to reinforce the defense of San Diego Bay at its weakest point, toward the south.

A second list named the existing seacoast batteries that were outmoded and would be excluded from the project when all the new batteries were completed:

| Tactical No. |

Battery | Caliber | Guns & Carriages | Location |

| 8. | Whistler | 12-inch | 4 mortars | North Fort Rosecrans |

| 9. | John White | 12-inch | 4 mortars | East Fort Rosecrans |

| 10. | Point Loma | 155mm | 4 GPF mobile | West Fort Rosecrans |

| 11 | Calef-Wilkeson | 10-inch | 4 guns DC | East Fort Rosecrans |

| 12. | Imperial | 155mm | 4 GPF mobile | Coronado Heights |

The War Reserve Allowance of ammunition for the seacoast batteries was shown as follows:

| Rounds per battery | |||||

| Name | Tactical No. |

Type of Projectile | War Reserve |

Battle Allowance | Place of Storage |

| 237 (Woodward) | 1 each | 105 lb. AP | 1080 | 1080 | 1,200 rds. of Battle in emplacement; rest in reserve magazine |

| 238 (Humphreys) | 4 each | 105 lb. HE | 360 | 360 | |

| 239 (Grant) | 7 each | ||||

| 126 (Ashburn) | 3 each | 2340 lb. AP | 360 | 360 | 200 rds. of Battle in emplacement; rest in reserve magazine. |

| 134 (16-inch) | 6 each | ||||

| Strong | 2 | 260 lb. AP | 450 | 450 | Emplacement |

| McGrath | 5 | 15 lb. AP | 720 | 720 | 400 rds. of Battle in emplacement; rest in reserve magazine. |

| Whistler | 8 each | 1046 lb. DP | 200 | 200 | Emplacement |

| John White | 9 each | 700 lb. DP | 400 | 400 | Emplacement |

| Point Loma | 10 each | 95 lb. HE | 1440 | 720 | Entire war reserve in reserve magazine except that placed in improvised dugouts at the battery position |

| Imperial | 12 | ||||

| Calef-Wilkeson | 11 | 617 lb. AP | 648 | 648 | Emplacement |

Excess rounds were to be stored in the reserve magazine, including ammunition for twenty-eight antiaircraft machine guns and sixteen antiaircraft 37mm automatic cannon. A site had been selected at the fort for the reserve magazine. It was to be constructed as a tunnel or tunnels with one or more entrances and with lateral tunnels; it was, however, never built.

The permanent batteries were organized into four groups, each with its own command post:

Group One - The two 16-inch batteries. Its command post to be in the top level of the two-level observation station connected with the HDCP (then occupied by the old Group Two CP).

Group Two - Batteries 237 (Woodward) and Strong. Its command post to be located on high ground 650 yards to the south of the north boundary and just west of the highway.

Group Three - The automatic antiaircraft weapons. The command post to be in the old mine casemate.

Group Four - Batteries 238 (Humphreys) and 239 (Grant). Its command post to be an underground concrete structure on Point Loma 135 yards directly south of the old lighthouse. [20]

|

| Battery Point Loma number 4 155mm Panama gun mount, currently located at Cabrillo National Monument. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

|

| Battery Point Loma ammunition storage. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

|

| Battery Point Loma, inside bunk room showing two-tiered bunk frames. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

|

| Barbed wire fence post establishing the northern perimeter of Battery Point Loma. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

cabr/guns-san-diego/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 19-Jan-2005