|

Casa Grande Ruins

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Arizona: A Centennial History of the First Prehistoric Reserve 1892 - 1992 |

|

CHAPTER II:

THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

Many late nineteenth and early twentieth century writers believed that the early Spanish explorers Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca, Fray Marcos de Niza, and Francisco Vasquez de Coronado viewed the Casa Grande between 1537 and 1540. Some of these authors were certain that it was the "Red House" described in Coronado's journal. These men's travels, however, did not take them to the Hohokam Great House. It was not until 154 years after Coronado traveled through Arizona that the first European beheld the remains of this once great culture. [1]

In 1694, when the Jesuit padre Eusebio Francisco Kino arrived in present-day southern Arizona for the first time, he heard the Piman-speaking peoples talk of a hottai ki not far away. In November of that year, accompanied by Sobaipuri Indians from the village of Bac, Kino set out to view this hottai ki or Casa Grande as he translated it in Spanish. After traveling forty-three leagues (about sixty-four miles) north of Bac, Kino found the large building. He recorded in his journal that

the Casa Grande is a four story building, as large as a castle and equal to the largest church in these lands of Sonora. Close to this Casa Grande there are thirteen smaller houses, somewhat more dilapidated, and the ruins of many others, which make it evident that in ancient times there had been a city here. On this occasion and on later ones I have learned and heard, and at times have seen, that further to the east, north, and west there are seven or eight more of these large old houses and the ruins of whole cities, with many broken metates and jars, charcoal, etc. [2]

From that point onward, the Great House received a notoriety that caused many travelers to come to behold this work of a mysterious people and to speculate on its origin and meaning. Padre Kino led a large party which included Capts. Juan Mateo Manje and Cristobal Martin Bernal to the Casa Grande three years later. When they arrived on November 18, 1697, Kino said Mass in the Great House. Following the service, the men explored the immediate area, and Bernal and Manje wrote descriptions of the prehistoric remains. These accounts present the first detailed narrative of the Great House and its surroundings. Manje's report provided enough detail that visitors two hundred years later could note that little had changed in the structure. He wrote:

there was one great edifice with the principal room in the middle of four stories, and the adjoining rooms on its four sides of three stories, with the walls five and one-half feet in thickness, of strong mortar and clay, so smooth and shining within that they appear like burnished tables, and so polished that they shine like the earthware of Puebla. At a distance of an arquebus shot twelve other houses are to be seen, also half fallen having thick walls, and all the ceilings burnt except in the lower room of one house which is of round timbers, smooth and not thick, which appear to be of cedar or savin, and over them sticks of very equal size and a cake of mortar and hard clay, making a roof or ceiling of great ingenuity. In the environs are to be seen many other ruins and heaps of broken earth which circumscribe it two leagues, with much broken earthware, plates and pots of fine clay, painted many colors, and which resemble the jars of Guadalajara in Spain. It may be inferred that a city of this body politic was very large; and that it was of one government is shown by a main canal which comes from the river from the plain, running around for the distance of three leagues and enclosing the inhabitants of its area, being in breadth ten varas [twenty-eight feet] and in depth about four [eleven feet], through which was directed perhaps one-half the volume of the river, in such a manner that it might serve as a defensive moat as well as to supply the wards with water and irrigate the plantations in the adjacencies. [3]

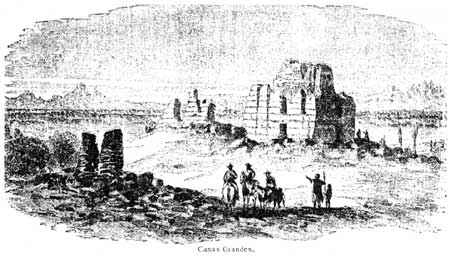

Manje also noted that the Great House measured thirty-one paces long and twenty paces wide. Bernal added that the plaster used on the interior and exterior of the Great House was reddish-colored mud. He also agreed with Manje's dimensions for the large canal, but Kino differed from them when he wrote that it was three varas deep [8.4 feet] and six or seven wide [16.8 to 19.6 feet]. The observation that the roofs had burned would be repeated by nearly everyone who subsequently visited. Later, many writers would erroneously ascribe the burning to Apache activity. It was probably not wanton destruction which accounted for the burning, but rather a method used by local Pima Indians to remove much needed construction timber from the buildings. [4]

Other padres purportedly visited Casa Grande in 1736, 1744, and 1762. Of these men, only the anonymous author of Rudo Ensayo provided a description which remains. As a result of his 1762 visit, this individual wrote that the roof was intact. The author for the first time referred to the Casa Grande as the house of Montezuma. He did so because he thought that the Aztecs had built it while on a sojourn before their travels ultimately took them to the Valley of Mexico. This misrepresentation persisted until the twentieth century. [5]

In 1775, Lt. Col. Juan Bautista de Anza recruited potential settlers in the area of present day southern Arizona and northern Sonora for an overland journey to establish an outpost in the area of current day San Francisco, California. These people, with their military escort, began their journey from the Presidio at Tubac in October. The Franciscan Friars Pedro Font and Francisco Garces were among the travelers. Upon reaching the Gila River on October 31, 1775, de Anza decided to give the people a day of rest. Garces and Font took the opportunity to visit the nearby Casa Grande which Font termed the "Palace of Montezuma." Garces deferred to Font's diary description rather than write his own account. Font began with the assumption that the structure had been built by the Aztecs who had "lived here when the devil took them on their long journey." These two friars were the first to make interior measurements of the Great House rooms as well as give the exterior dimensions. It consisted of five "halls" of which the three in the center were identical in size measuring twenty-six feet north to south and ten feet east to west. The two "halls" at each end were twelve feet north to south and thirty-eight feet east to west. Font found the doors to be five feet high and two feet wide. Exterior walls were four feet thick while interior walls exceeded those of the exterior by two feet. Outside dimensions ran seventy feet north to south and fifty feet east to west. The outer surface of the exterior walls sloped inward near the top. The Great House consisted of three stories and the two friars thought they detected indications of a fourth floor. Font and Garces observed that the Great House was surrounded by an enclosure inside of which there were other buildings. The enclosure walls measured 420 feet north to south and 260 feet east to west. The ruin of a "castle or watch tower" was located in the southwest corner of the enclosure. Another ruin just east of the Great House had a twenty-six by eighteen-foot dimension. The remains of this structure was ultimately called Font's room where it was thought he had said a mass. Font reported that the ground was littered with pieces of pots and jars. [6]

|

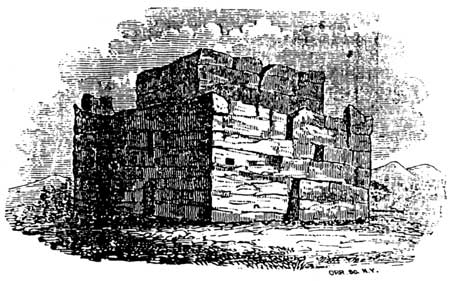

| Figure 1: 1846 Sketch of the Great House by Stanley of the Kearny Expedition. Courtesy of Casa Grande Ruins National Monument. |

For about sixty-five years after the Font and Garces visit, few white men visited Casa Grande, and no one published a description of the structure. The ten-year Mexican rebellion for independence succeeded in 1821. Politicians of the new republic, however, rarely took note of any activity outside of the Valley of Mexico. Consequently, American fur trappers began to arrive in the area in the early 1830s attracted by the beaver that inhabited the Gila River. Evidence of their presence is seen on a wall of the Great House where a trapper named Pauline Weaver scratched his name and date. Not everyone in Mexico ignored the area, however. Copies of Garces and Font's diaries evidently circulated about Mexico for years. In 1844 Eduard Muhlenpfordt, a German who had resided in Mexico for ten years, published a description of that nation. In it he wrote of having read the two friars' "incomplete" diaries. He wrote that little was known about the area of the Gila River except that there were ruins of an old city there "which is known to the neighboring Indians as Hottai-Ki." Muhlenpfordt gave the first report of artifact removal when he noted that more than one piece of pottery had been found there. As a consequence of his two-volume work, which he published in Germany, Casa Grande received greater foreign notice. [7]

On October 29, 1848, Cave J. Couts passed within sight of Casa Grande. He called it the "Aztec Castle or temple" and exaggerated its dimensions when he wrote that it "is seven stories high with walls 10 or 12 yards in thickness." The men in a neighboring Pima village told Couts that the building "was left by their grandfathers, as a sacred place." These Pima could not give a date when it had been built, but, according to their legend, all the races of mankind had come from it with the whites coming "from one side, Mexicans from another, Indians from another, etc." Since there were only four sides to the Great House, the Pima recognized only four races, but then they had not encountered other ethnic groups. [8]

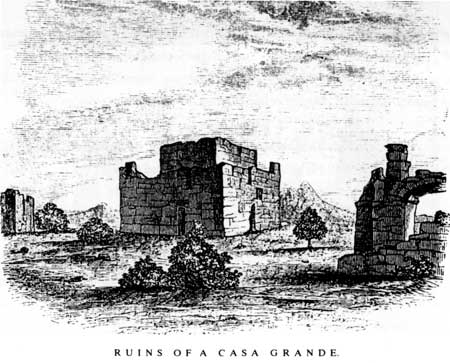

Soon after Muhlenpfordt's work was published, the start of the Mexican-American War caused Casa Grande to be visited by ever increasing numbers of people from the United States. The first such group, a military detachment on its way to California under the command of Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny, arrived at noon on November 10, 1846. At the time the party halted for its midday meal, Major William Emory, among others, sighted the Casa Grande and went to investigate it. Emory called it the remains of a three-story mud house. He pronounced the relic to be sixty feet square with walls four feet thick. Ceiling timbers had been burned out of their seats in the walls to a depth of six inches. In fact Emory felt that the whole interior had been burned. As would become the fashion of future visitors, Emory and the others made a "long and careful search for household furniture, or other implements of Art." These early treasure seekers seemed not to have too much success, for they found only a corn grinder (metate) and a few marine shells which had been cut into various ornaments. While Emory inspected the ruin, a fellow traveler, Stanley, sketched it (figure 1). Dr. John Griffin, a surgeon for the detachment, called the Great House "Casa Montezuma". He probably talked with the local Native Americans who passed on the name they had heard mentioned by the Spanish. Griffin pronounced the structure to be an excellent house, built of cement and sand. Inside, it had a very fine finish. Although Emory did not mention anyone removing the remains of rafters from their wall seats, some were taken out because Griffin wrote that he had been told the butt ends had been cut with a stone ax. E.G. Squire incorporated Emory's account in his 1848 description of the region and provided a drawing (figure 2). [9]

|

| Figure 2: Drawing of the Casa Grande. E.G. Squire, "New Mexico and California," American Review, November 1848 |

Not all travelers were happy with the route through the Casa Grande region. If Brantz Mayer had had his way, the Great House would have been spared the destructive visits of graffiti makers and souvenir hunters. After his 1852 visit, Mayer hoped for the day when steam routes would create the situation whereby "travellers will not be compelled to pass either the desert or those more southern regions where the moldering ruins of Casas Grandes [sic] denote the ancient seat of Indian civilization." Despite his dread of the desert, Mayer did appreciate the Great House enough to include a drawing of it in his work (figure 3). [10]

|

| Figure 3: Sketch of the Casa Grande in 1853. Brantz, Mayer, Mexico, Aztec, Spanish and Republican, Vol. 2, Hartford: S. Drake, 1853. |

Probably the most learned man to describe and draw (figure 4) the Great House in the antebellum era came to the area to establish the new boundary between the United States and Mexico following the war between those two nations. Not only would John Bartlett offer the first interpretation for the use of the Casa Grande, but he suggested means by which it could be preserved. Bartlett speculated that the inner rooms must have been used to store corn and perhaps the whole building had been a granary. He noted that the base of the outside walls had crumbled and had been cut inward some twelve to fifteen inches. Since this destabilized the structure, he thought that a couple days spent in restoring the wall bases with mud and gravel would keep the building durable for centuries. [11]

|

| Figure 4: 1852 Drawing of the Great House. John R. Bartlett, Personal Narrative of Explorations, Vol. 2, NY.: D. Appleton & Co., 1854. |

Bartlett was quite familiar with Casa Grande before he arrived there since he had read the accounts of Juan Mateo Manje and Pedro Font. While marking the international boundary along the Gila River on July 12, 1852, Bartlett found the Great House. He wrote that two or three miles before getting there he noticed irrigation canals and broken pottery. The surrounding countryside was covered with twelve-to twenty-foot high mesquite. On the site, he noted that there were three buildings. The Great House, with three stories and a dimension of fifty by forty feet, was the best preserved although its top had crumbled. Bartlett decided that there must have been a fourth story, otherwise he could not account for all the rubbish inside the structure. The thick walls consisted of large square blocks of mud which Bartlett thought were prepared by pressing earth into boxes that were about two feet high and four feet long. Exterior walls tapered inward toward the top. The southern front wall had fallen in places and had long fissures, but the other three sides were "quite perfect." On the outer surface, the walls had been given a rough plaster, but on the inside the surface had received a hard finish. Inside the rooms, he saw the charred ends of four-to five-inch diameter beams in the walls. [12]

Numerous ruins could be seen in the immediate area of the Casa Grande. Near the Great House to the southwest, a second ruin stood with a two-story central section. A third ruin was located just northeast of the Casa Grande, but it was in such poor condition that its original form could not be discerned. In fact Bartlett saw mounds of dirt in every direction, suggesting the remains of a large number of structures. Bartlett was the first to describe a semi-circular embankment with an eighty-to 100-yard circumference located just northwest of the Great House. He had found the ballcourt although he did not realize it at the time. Interspersed with the mounds were numerous pottery fragments. Bartlett collected some of these pottery pieces. [13]

In his narrative, Bartlett included the accounts of Casa Grande produced by Lt. Juan Mateo Mange and Padre Pedro Font. He wrote that in 1775 Font had thought the Aztecs had built the Great House some 500 years before that date. Bartlett professed not to understand how the Aztec story had originated since there was not one shred of evidence to support such a tale. He observed that even the Aztec language differed from that of tribes to the north. [14]

In 1853 the United States approached the Mexican government seeking to purchase land south of the Gila River for a southern transcontinental railroad. James Gadsden, the American negotiator, succeeded in reaching an agreement on December 30, 1853. It was approved in Washington in June 1854. At that time Casa Grande fell within American territory. Since the Apache had established pre-eminence in that area, few white men chose to travel in the vicinity of the Casa Grande in the latter 1850s and 1860s. J. Ross Browne and Charles Poston accompanied by a contingent of California Volunteers and guided by Cyrus Lennan, a local trader, did visit the ruins in January 1864. The route from the Pima headquarters at Sacaton along the Gila River proved difficult because of the numerous groves of dense mesquite. Once at the Great House, the party found the ruins in the same condition as previous viewers. Like Bartlett, Browne made a drawing (figure 5) and noted that the upper part of the structure had been washed and furrowed by rain, while the base had worn away to such depths that it threatened the whole building. Much of the group's time was spent in collecting souvenirs. The guide, Lennan, told Browne that on previous occasions he had dug at Casa Grande and had found a number of bone awls. Others, Lennan stated, had uncovered items of flint, bone, and stone. When the assemblage departed, they left "well laden with curiosities." Everyone had his pottery fragments as well as specimens of adobe and plaster. [15]

|

| Figure 5: 1864 Drawing of the Great House. J. Ross Browne, Adventures in the Apache Country Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1974 |

All of the "curiosities" removed from the site evidently whetted Charles Poston for more. As Commissioner of Indian Affairs in Arizona, he wrote to his superior in Washington, D.C. that he and Browne had just visited a ruin that had been built by a "very superior civilization." Since remnants of stone and earthenware were strewn for miles around it, Poston thought,

if some excavations could be made about this old ruin it might lead to the discovery of relics throwing some light on this obscure subject.

A considerable examination might be made for an expenditure of five hundred dollars if done under supervision of the Indian Agent at the Pima Villages or some officer of the government stationed in the vicinity. [16]

Poston's recommendation was the first plan advanced for an archeological excavation, but nothing came of this proposal. He never wrote of returning to Casa Grande to "recover" more "curiosities."

By the late 1860s and early 1870s more people came to view the Great House ruins and non-Native American settlers began to farm and ranch along the Gila River. When Ralph Norris surveyed the interior township lines for Township 5 South, Range 8 East during the summer of 1869, he noted four Mexican families farming along the Gila within several miles of Casa Grande. It was possible that they used some of the old Hohokam canals to irrigate their fields. Obtaining water from the Gila adjacent to their fields would have proved difficult, for Bartlett reported in 1853 that the river bank north of Casa Grande was some fifteen feet above the water. John Devine erroneously reported later that, when he visited the ruins in the 1860s, the Great House had five complete stories and the floor joists were in place and perfect. Visitors for more than 160 years had never found the ruins in such condition. It certainly was not in that pristine form when Charles Clark rode to the ruins in 1873. To investigate the interior of the Great House, Clark crawled through a door opening which was nearly filled to the top with debris. Some Indians interrupted him as he was trying to remove one of the floor joist remains from a wall. He remained hidden in the ruins and watched as they took his food and the bridle from his horse before departing. Clark spent the night in the Casa Grande in fear of the Indians' return. When none had reappeared by the next day, he rode to "Decker's ranch" on the Gila River just north of the ruins. Clark's Indian experience did not stop him from returning the next year. This time he was accompanied by a Professor Hodge from Ann Torbar [Ann Arbor?], Michigan. The two men crawled back into the ruin where they removed two charred stubs of floor joists from a wall. Just as Clark and the professor were preparing to dig in the center part of the Great House, a representative of the Indian agent at Sacaton arrived and told them that the Pima would not permit digging in the Casa Grande. As a result, they packed their equipment and left. Subsequent Indian agents at nearby Sacaton did not take as much interest in the ruins and artifact removal ultimately became a common practice. [17]

Scholastic interest in Casa Grande did not end with Professor Hodge of Michigan. Educational and scientific inquisitiveness about the ruins developed in the 1870s. To stimulate the curiosity of school children, a January 1877 issue of the Juvenile Instructor carried an article on the Great House. The first real scientific investigation of the ruins occurred in April 1879. Led by Henry Hanks, an assemblage of New Jersey geologists including Professor George Cook set out to explore and document Casa Grande. Hanks wrote his impressions of the countryside and the ruin. As they rode west from Florence, the party found the ground to be covered with broken pottery. Although the mesquite trees were low, they hid the Great House until the group was almost at the site. As he approached the Casa Grande, Hanks was disappointed. He found that his romanticized image of a stately building, that he had gained from published descriptions, did not hold true. Hanks wrote that one saw

only a huge dun colored, almost shapeless mass, looming up strangely from the desolate plain. There is nothing architectural about the structure. It is, at best, but a mud house; though, as he examines it more closely, it seems more and more wonderful, and the mind is filled with conjecture as to the uses to which this great building may have been put, and why it stands so lonely and isolated. [18]

Professor Cook took samples of the wall material from the Great House. Analysis of this soil showed the walls contained seventeen percent carbonate of lime. This amount of lime led to the speculation on how the prehistoric inhabitants had obtained it. Some thought that it could have come from sea shells from the Gulf of California, but this solution was ruled impossible since that much lime could not have been carried that distance. Others believed that the soil had a high degree of calcium, but most decided that the lime was burned with the building material. [19]

While at the ruins, Hanks, with the group of New Jersey scholars, took exact measurements of the Casa Grande. Its walls were 3.7 feet thick. The highest point was thirty-five feet although it was thought to have originally been four or five stories. The central series of rooms were still one story higher than the outer walls. Its length was 58.5 feet with a forty-three-foot width. A check of its alignment showed that the structure was almost, but not quite in line with the cardinal points. Some parts of the building's exterior were still smooth while other areas had cavities. Years of rain storms and natural sand blasts had taken a toll. Interior walls showed signs of a fire from long ago, but the rafter ends were preserved in the walls. When Hanks and the group removed some of these rafter ends, they could see that blunt instruments had been used to cut them. [20]

The New Jersey group conjectured about the uses made of the Great House. Some offered the idea that it had been a grain warehouse since the irrigation canals led them to believe that the original inhabitants had raised extensive amounts of crops. Further thought led to the conclusion that the small floor rafters would not hold the weight of much grain. One individual decided it served as a temple, but he changed his mind because the small, multiple rooms with a great number of doors and "port-holes" ruled against such a function. In the end, the party determined that all speculation was absurd because no clue remained of its use. Their only hope was that the building be preserved before vandals carried it off piece by piece. People had already dug in and around the structure. Hanks thought that the territorial legislature needed to pass a law soon to protect the Great House, but neither he nor any member of the group made an effort to communicate with the legislature. [21]

Less than six months after the New Jersey party departed, the Phoenix Herald reported that Indian Inspector Hammond had spent several days at Casa Grande making "careful and scientific examination" of the ruins. Hammond did not confine his activities to the Great House as his predecessors had done. In addition to measuring and describing the main building, he measured the quadrangle enclosure wall and the remains of other structures within that area. Outside of this area, which later became identified as Compound A, Hammond measured other ruins including an artificial platform which he found northeast of the Great House. This platform undoubtedly was one of two such platform mounds uncovered in an area later named Compound B. Hammond's examination included excavations that he made around the expanse of remains. He found no weapons or tools. Hammond recovered "immense quantities" of pottery and exposed a four-to six-inch layer of charcoal as well as grass from "thatched roofs." [22]

Greater opportunity for looting and vandalism occurred after the Southern Pacific Railroad completed a line through the area in the winter of 1879-80. The railroad honored the ruin by naming its station twenty miles to the west Casa Grande. Soon a stage line opened between Florence and the Casa Grande station. It ran within a few feet of the Great House. The stage driver would frequently stop to permit passengers to explore the grounds. This situation undoubtedly led many people to return to the ruins to dig among the remains. Railroad officials probably helped to encourage such activity after the Arizona Daily Star published a story that one Southern Pacific official intended to take some men and tools and investigate the ruins. [23]

It was not long before publications began to remark on the amount of artifacts being recovered at Casa Grande. Patrick Hamilton wrote in 1884 that "a number of stone axes, bone awls and other implements of the stone age have been excavated from the ruins." Another author stated that people who had dug in the ruins had found whole pottery of which some pieces were large ollas like those used by modern Indians. A Florence merchant even defaced the Great House by using it as an advertisement billboard. It was no wonder that concerns for the preservation of the Great House were raised. [24]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

cagr/adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2002