|

Casa Grande Ruins

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Arizona: A Centennial History of the First Prehistoric Reserve 1892 - 1992 |

|

CHAPTER III:

THE RESERVATION OF CASA GRANDE LAND AND ITS EARLY ADMINISTRATION

A. The Establishment and Stabilization of Casa Grande Ruins

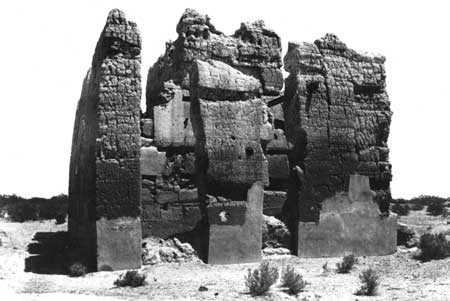

The beginning date of a movement to preserve Casa Grande ruins has never been established. Edna Pinkley pointed to 1865 as a possible date, because at that time Charles Poston, then territorial representative to the national legislature, supposedly brought Casa Grande to the attention of the United States Congress. The 1860s, however, were too early a period to identify with a ruins preservation movement. Sallie Van Valkenburgh chose 1877 as the year when "the first 'resolution' for preservation of the ruin may have been made." [1] As evidence she cited a December 13, 1877 proposal by a group accompanying Richard J. Hinton across Arizona to form an archeological society. Whether that resolve stimulated a preservation movement or not cannot be ascertained with certainty; however, Van Valkenburgh's 1877 date can most likely be considered as correct. It was in 1877 that the first photographs of the Great House were taken. These and the ones produced in the following year (figures 6-8) were placed on sale for home stereoscopic viewing and, therefore, provided the general public with the first tangible glimpse of the Great House. The photos, combined with published accounts of the ruins, seemed to have stimulated at least a local desire to preserve the last vestige of a vanished culture. It undoubtedly required a year or more before such a desire evolved into a movement. The first account of such activity appeared in the Weekly Arizona Miner, a newspaper in the territorial capital of Prescott. It carried a report in February 1879 that people wished to have an appropriation "to improve and reserve" the Casa Grande ruins. A group of New Jersey geologists, who visited the ruins in April 1879, concluded that the territorial government needed to act soon to protect it. The territorial legislature was not forthcoming with money or an act to preserve Casa Grande. It had still not acted by 1887 when H. S. Jacobs, a United States Geological Survey official, advised the Arizona people and legislature that Casa Grande had sufficient scientific and historic value that it should be protected from vandalism and natural decay. [2]

|

| Figure 6: The Casa Grande Viewed from the Southeast Ca. 1878. Courtesy of the Arizona Department of Library, Archives and Public Records. |

|

| Figure 7: The Casa Grande Viewed from the North Ca. 1878. Courtesy of the Arizona Department of Library, Archives and Public Records. |

The beginning of a national focus on Indians in the Southwest occurred in 1878 with a visit to the area by the pioneer anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan. After visiting this section of the country, he decided that it offered the opportunity to prove his theory on man's social evolution. As a result, when the Archaeological Institute of America (MA) was founded the following year, he submitted a research proposal to it for such a study. Morgan's student, Adolf Bandelier, was hired to conduct the research. Bandelier spent five years in New Mexico and Arizona collecting data. In the course of his sojourn, he visited Casa Grande in May 1883. Bandelier wrote that the ruins at Casa Grande covered a nineteen-acre area and could be divided into two groups. The southern group included the Great House. A northern group contained such features as an artificial mound resting on an artificial platform and an elliptical tank. This tank served as a reservoir for both group areas, he thought. His "groups", came to be identified as Compounds A and B, while the "tank" ultimately proved to be the ballcourt. Bandelier produced two reports on his findings — one in 1884 and a final account in 1892. In the first study he felt that the ruins at Casa Grande had served as residences, but, by 1892, he viewed the structures as places of retreat during attacks. He was led to the final conclusion because of the strength of the walls, commanding positions, and height. [3]

Within a year after Bandelier embarked on his Southwestern study, and probably as a direct result of his focus on the southwestern part of the country, Frank H. Cushing, a Massachusetts anthropologist, began his work among the Zuni and Hopi. Cushing's experience led Mary Hemenway to select him to lead the Hemenway Southwestern Archaeological Expedition which she financed for the years 1887-88. The effort of this group was directed toward excavations of Hohokam ruins in the Salt River Valley, but the party also explored along the Gila River and visited Casa Grande. Sylvester Baxter, the secretary-treasurer of the Hemenway Expedition, came to Arizona to visit the expedition in early 1888. He located the company at Casa Grande. On the evening of January 24, Cushing showed Baxter around the ruins. Baxter could see the effects of vandalism. Souvenir hunters, he wrote, had taken the few remaining timbers and undermined parts of the walls. During this visit Baxter became very attached to Casa Grande and became a champion in the cause for its preservation. He described the Great House in somewhat romantic terms. On the first night of his visit he wrote, "that night, in the full moonlight, the Casa Grande assumed a soft, poetic beauty, with its ruddy surface flooded with radiance that threw the shadows of its deep recesses into a rich mysterious obscurity ..." While the expedition members lay in their tent looking at the Great House in the moonlight, Cushing told them a Zuni folk tale about the "priests of the house." Baxter thought that "as we listened, the ancient walls before us seemed to be repeopled with the venerable old priests." [4]

When Baxter returned to Boston, he wrote an account of his Arizona visit for the Boston Herald. He also persuaded Mrs. Hemenway of the importance of preserving the Great House because it was "so precious on account of its being the only standing example of this important class of structure peculiar to the ancient town-dwellers of the Southwest, and its consequent inestimable value for archaeological study. . . ." [5]

|

| Figure 8: The Great House viewed from the Southwest 1878. Courtesy of the Sharlot Hall Museum, Prescott, Arizona. |

Mrs. Hemenway, Baxter, and some politically influential Bostonians at first sought to achieve their end of protecting Casa Grande by working through the executive branch of the federal government. They contacted Capt. John Bourke for aid. He wrote to the adjutant general of the United States Army on June 30, 1888, to state that some Boston friends requested that a measure be taken by the national government to preserve the "Casa Grande" prehistoric ruins from vandalism. These Boston friends suggested that, since the ruins were on a school section which exempted it from being claimed, the Interior Department might create a reservation and place an individual in charge of it. Bourke's letter rapidly passed from the adjutant general to the secretary of war. The secretary, in turn, forwarded it to William Vilas, the secretary of the interior, on July 6. Vilas sent the letter to S. M. Stockslager, the commissioner of the General Land Office, for his opinion. Stockslager replied that, since Casa Grande was located on a section of land legally reserved for schools, the president could not set it aside or create a reservation of that tract to preserve a ruin. It would take an act of Congress to create a reservation. [6]

When the United States Congress convened for its session during the winter of 1888-89, the "Boston friends" changed their focus to that body. Mrs. Hemenway "set about making earnest efforts to secure from Congress measures for its [Casa Grande's] protection." Sylvester Baxter wrote that she was "ably seconded by Mr. Cushing, who spent several weeks in Washington for that purpose." They persuaded Senator George F. Hoar of Massachusetts to aid their cause. On February 4, 1889, he told the assembled U.S. Senate,

I present the petition of Oliver Ames, governor of Massachusetts, William E. Barrett, speaker of the house of representatives, Mrs. Mary Hemenway, who has been eminent as a benefactress to many institutions of education, William Claflin, Francis Parkman, Dr. Edward Everett Hale, Oliver Wendell Homes, John Fisk, and William T. Harris, and the petition is also supported by an autograph letter from John G. Whittier, calling the attention of Congress to the ancient and celebrated ruin of Casa Grande, an ancient temple of the prehistoric age, of the greatest ethnological and scientific interest, situated in Pinal County, near Florence, Ariz., upon section 16 of township 5 south, range 8 east, and otherwise describing the site.

The petitioners state that this ruin, which is one of the most interesting monuments of antiquity in the world, a temple of great beauty and architectural importance, which was a ruin when Columbus discovered America, is specially worthy of the care of the Government; that it is in danger of being destroyed by visitors and also by the letting in of water on the adjacent land for the purposes of irrigation. Mrs. Hemenway has already been at large expense for the preservation of this ruin, and the investigation of the traces of the prehistoric races in that neighborhood; and the desire of the petitioners is that the Government will take proper measures to have the ruin protected from injury by visitors or by land-owners in the neighborhood. They ask no outlay of money from the Government for the purpose; that will be assumed, and they are willing that all the scientific discovery there shall go to the benefit of the Smithsonian or other Government institution.

I desire that this petition may be referred to the Committee on Public Lands, and I ask their special consideration of it. [7]

Cushing also sought to gain support in the executive branch of government by sending a "Report to the Secretary of the Interior re Casa Grande" on February 13, 1889. In addition to urging the secretary's help in protecting Casa Grande, his report described the ruins and the excavations that he had made there. To Cushing, all the ruins were once used as temples. The Great House functioned, he thought, as only one of six divisions of an enormous temple which comprised the enclosure in which it was located. His excavations occurred in the debris of the central and south rooms of the Great House and into the sides of a large oval (the ballcourt). [8]

Although the Boston petitioners did not request preservation funds for Casa Grande, Senator Hoar succeeded in getting an appropriation in addition to approval for the president to declare a reservation. Attached to the March 2, 1889 Sundry Civil Appropriations Act (25 Stat. 961) was a rider on the United States Geological Survey (USGS) budget which stated:

Repair of the ruin of Casa Grande, Arizona: To enable the Secretary of the Interior to repair and protect the ruin of Casa Grande, situated in Pinal County, near Florence, Arizona, two thousand dollars; and the President is authorized to reserve from settlement and sale the land on which said ruin is situated and so much of the public land adjacent thereto as in his judgement may be necessary for the protection of said ruin and of the ancient city of which it is a part. [9]

A month later the Rev. Isaac T. Whittemore of Florence lunched with the Arizona Presbytery within the Great House walls. It had been a year since he had been there. In that short period he noted that vandals had taken their toll. As a result, on April 6, 1889, he wrote a letter to the secretary of the interior asking him to confer with the secretary of indian affairs and to send troops to protect Casa Grande from further vandalism. Whittemore told the secretary that "speedy" attention was needed to repairs for the Great House. He then suggested that bolts and rods should be placed in the structure to keep it from falling to pieces. In addition the base of the walls needed to be rebuilt in places and a roof constructed over it. [10]

Whittemore's letter evidently had some effect. On April 12, 1889, John Noble, the secretary of the interior, met with S. M. Stockslager, the commissioner of the General Land Office to discuss the Casa Grande issue. As a result of the meeting, the commissioner issued a statement on April 16 that the $2,000 repair money would be available after July 1, 1889. Nothing was said about first placing the ruins on a reservation. Stockslager suggested that a special agent be sent to examine the ruin. As a result, he sent two letters on April 27. One letter, to Alexander L. Morrison of the Santa Fe division of the General Land Office, directed him to proceed to Casa Grande to make an inspection and report what he felt should be done to repair and protect it. The other communication was sent to Whittemore informing him that Morrison was coming. [11]

Morrison arrived in Florence, Arizona on May 7, 1889, and went with Whittemore to inspect the ruin on the following day. On May 15, he sent his report to Commissioner Stockslager. In it Morrison stated that he saw danger to the ruins from three sources: vandalism, the elements, and wall undermining. Whittemore's ideas on preservation evidently impressed Morrison because he recommended that the walls be underpinned with stone, a roof be constructed over the Great House to protect it from the elements, debris be removed from the entire building, and a fence be constructed to keep out intruders. When the report reached Washington, Morrison's recommendations were deemed to be too expensive. [12]

Despite the dismissal of Morrison's recommendations, the secretary of the interior recognized an urgent need for repairs to Casa Grande. Consequently, he contacted the director of the United States Geological Survey and asked him to take appropriate action to begin repairs without delay. Through contact with the Bureau of American Ethnology, the USGS director obtained the service of anthropologist Victor Mindeleff. On November 27, 1889, Mindeleff was asked to go to Casa Grande to view the ruins and suggest repairs. [13]

As Morrison had done, Mindeleff contacted Whittemore when he arrived in Florence and Whittemore accompanied him to Casa Grande. Again Whittemore probably provided an opinion on appropriate repairs, for, when Mindeleff submitted his report on July 1, 1890, it contained many recommendations similar to those offered by Morrison. Mindeleff stated that the main destruction to the ruins came from undermining of the walls, but visitors had also done much damage. He, therefore, advocated six measures to protect the ruins. These items included:

1.) Fence the ruins area;

2.) Provide a permanent on-site custodian;

3.) Clean the debris from the Great House;

4.) Underpin the Great House walls with brick;

5.) Remove several inches of material from the wall tops to provide a good bearing surface and then cap the walls with concrete;

6.) Reinforce the walls with tie-rods and beams, replace broken and missing lintels, and fill cavities above the lintels.

Although Mindeleff thought that points five and six would be sufficient for weather protection, he included a roof plan for the Great House. The roof plan was, no doubt, placed in the report to please Whittemore who, by now, had begun to describe the roof he desired as one of corrugated iron. [14]

In the meantime, almost seven months before Victor Mindeleff submitted his report, point two had been partly resolved. On December 3, 1889, John Noble, the secretary of the interior, wrote to Whittemore to say that he authorized him to act as an uncompensated custodian of Casa Grande unless Congress provided funds in the future. The offer did not require on-site residence.

If he agreed to accept this position, then Noble asked Whittemore to notify the director of the United States Geological Survey. Whittemore replied on December 11, 1889 that he viewed it as a privilege and honor to serve as custodian. He promised to "warn all intruders and relic hunters and spoliators, to keep 'hands off'" the ruins. [15]

Despite the fact that it entailed more work to repair and protect the ruins than the discredited plan offered by Morrison, Victor Mindeleff's recommendations were approved. Mindeleff, however, did not remain with the Bureau of American Ethnology and his brother Cosmos replaced him on the Casa Grande project. Although it was recognized that not enough money had been appropriated to accomplish all of the approved plan, the USGS director decided to proceed with the work. On November 20, 1890, Cosmos Mindeleff received orders to go to Casa Grande and make as many repairs as possible within the appropriated funds. Still, the president made no move to establish a reservation. [16]

Cosmos Mindeleff arrived at Casa Grande in late December 1890. Before a bid announcement for a repair contract could be made, he had to make a detailed survey of the Great House as well as produce plans and sections of potential excavations. Although the building had weathered, Mindeleff thought that much damage had been caused by the "craze for relics" which possessed some individuals. He wrote that more damage had been done in the last twenty years by these "treasure hunters" than had been done in the previous 200 years. The south and east fronts had suffered more than the other sides from the weather. Mindeleff observed that the northeast and southeast corners had fallen. Portions of the south wall were weak and likely to fall. He thought that the greatest destruction of the walls occurred at ground level. It was at that location that ground water had risen by capillary action upward of a foot in the base of the walls and caused them to erode. Vandals on the other hand had removed all the lintels and every piece of visible wood except for a few flooring stumps imbedded in the upper portion of the walls. [17]

Having made his survey of the Great House, Mindeleff sought to attract bidders, but he had difficulty because of the small amount of money available to accomplish the tasks. He called for bids on four items which included: 1) removing the interior debris and that found in an area ten feet outward from the walls, 2) underpinning the walls with brick set to a depth of twelve inches below ground and faced with concrete, 3) restoring the lintels and filling the cavities above the openings, and 4) tieing the south wall to the building by using three internal braces. He did not include a fence and he dismissed the idea of a roof on the belief that it would destroy the picturesqueness of the ruin. Finally, with the aid of Custodian Whittemore and C. A. Garlick of Phoenix, three bids were received. Theodore Louis Stouffer and Frederick Emerson White of Florence made the low bid of $1,985 and received the contract on May 9, 1891, pending approval by the Secretary of the Interior. The contract was sent to the secretary through the director of the USGS. Secretary Noble signed it on June 20. The initial two months time limit on the contract was changed to four months. It expired on October 31, 1891. [18]

Since he had building experience, Mindeleff got Custodian Whittemore to oversee the repair work (figures 9-12). For his effort he received the $15 difference between the $2,000 appropriated for repairs and the $1,985 contract sum. Near the end of the contract, H. C. Rizer, the chief clerk of the Bureau of American Ethnology, arrived to make a final inspection. In his report submitted on November 24, 1891, Rizer found that the contractors had accomplished more than the contract specified. As a result, the two Florence men filed a claim on January 7, 1892 for $600.42 more than they were paid under the contract. The government, however, disallowed the claim on January 28. [19]

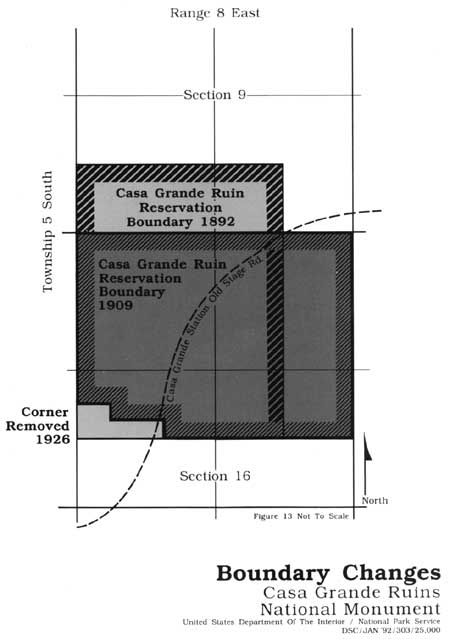

Although repairs had been made to the Great House, Custodian Whittemore still had no authority because the president had yet to set the land aside as authorized by the March 2, 1889 act. With some prodding from the Bureau of American Ethnology, the Secretary of the Interior finally recommended that 480 acres in Sections 9 and 16 of Township 5 South, Range 8 East of the Gila and Salt River Meridian be reserved. Acting on that referral, President Benjamin Harrison proclaimed the 480-acre Casa Grande Reservation on June 22, 1892 (figure 13). As the first prehistoric and cultural site established by the American Government, the Great House was finally safe from sale or claim. [20]

B. The Era of Isaac T. Whittemore and H. B. Mayo

From the time Whittemore accepted the Casa Grande custodianship in December 1889 until its establishment as a reservation on June 22, 1892, he served in name only, for there was no plot of ground for him to administer. Whether he made any efforts in that period to warn intruders not to vandalize the ruins, as he stated in his acceptance letter, remains unknown. Whittemore did have an enthusiastic interest in preserving the ruins and frequently visited the site. [21]

With the establishment of the reservation in June 1892, Whittemore had the responsibility to administer it. He reported to the commissioner of the General Land Office. In addition, he no longer performed any tasks for free. As soon as the land was reserved, the General Land Office commissioner requested that the Interior Department provide $720 per year for the custodian's salary. That department, however, allowed only $480. This sum would be the custodian's annual salary until Frank Pinkley accepted that position in December 1901. [22]

At first no government department or agency provided Custodian Whittemore with a list of duties. Since no government land had previously been set aside to preserve a cultural site, it was undoubtedly difficult to decide what duties a custodian should perform. It was possible that the General Land Office commissioner wrote to Whittemore for suggestions, but no record remains if such a letter were written. In November, however, Whittemore wrote to the Land Office commissioner and reported that his duties were to visit Casa Grande and report any spoliations or deteriorations. He stated that he had received no instructions on how frequently he needed to visit Casa Grande. Whittemore felt that one visit per month was sufficient considering his salary and the distance he had to travel from Florence to the ruins. It soon became evident that one visit per month or even one visit per week would never prevent vandalism when Whittemore reported that, since his last visitation, people had marked the walls with pencil or nails. [23]

|

| Figure 9: The Great House Viewed from the South 1891 This photograph shows the brick work before it was faced with concrete. Courtesy of Casa Grande Ruins National Monument |

In his November 1892 report to the General Land Office commissioner, Whittemore again mentioned his favorite subjects. He wrote that the Great House walls were sound, especially since they had been repaired in the past year. The walls of the upper story, however, needed to be protected by a roof. In addition, the area needed fencing. The heads of the various agencies and department, through which Whittemore's correspondence circulated, had similar reactions to his requests. At first, they either found a roof objectionable or they had no funds. The director of the USGS unsuccessfully sought funds from his agency for a fence. Whether by accident or on purpose, the General Land Office leadership even tried to pass off Casa Grande to another agency. On February 20, 1893, the assistant commissioner of the General Land Office reported that their records showed that Casa Grande had been placed under the control of the Bureau of American Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution. Therefore, the assistant commissioner suggested that Whittemore make no more reports to his agency. Whittemore must have felt like an unwelcome stepchild. [24]

Despite rejections, Custodian Whittemore did not quit submitting requests. In fact, he broadened his appeal when he reported to the secretary of the interior in September 1893. Whittemore asked for $7,000 or $8,000 to fence forty acres, construct a corrugated iron roof over the Great House, and make excavations in all adjacent ruins. In his view "the necessity of roofing the Ruin is imperative" to prevent the upper wall surface from further erosion. Whittemore requested money for an excavation because he believed that artifacts found in the area were similar to those used in China. Consequently, he wished to have an investigation "in the interest of scientific research" to learn more about the builders' origin. Whittemore also informed the secretary of the interior that, after he found two men painting their names on the Great House walls in July, he had posted a sign which read "Property of the US Government, $300 fine for further defacing this Ruin." By so doing, Whittemore exceeded his authority because no law existed until 1906 to fine vandals. [25]

Unfortunately, the 1893 depression resulted in reduced government spending. Under this circumstance, Whittemore waited until mid-1895 to renew his appropriation request. On this occasion, W. J. McGee, the acting director of the Bureau of Ethnology, supported Whittemore. He told the secretary of the interior that only a roof could protect this one-of-a-kind ruin. Consequently, McGee was sent to examine the great house. In his November 1895 report, McGee concluded that the rate of destruction had advanced with "cumulative rapidity." He also recommended a roof for the ruin, but without success. [26]

|

| Figure 10: The Casa Grande Viewed from the South Ca. 1902. This photograph shows the concrete facing on the brick. Courtesy of the Colorado Historical Society. |

|

| Figure 11: The Casa Grande Viewed from the East Southeast Ca. 1902. William Henry Jackson Photograph #14395. Courtesy of the Colorado Historical Society. |

|

| Figure 12: The Casa Grande Viewed from the Northwest Ca. 1902. William Henry Jackson Photograph #14397. Courtesy of the Colorado Historical Society. |

As a final act of his custodianship, Whittemore wrote to Binger Hermann, the General Land Office commissioner, in January 1899 to remind him once more of the critical need for a roof over the ruins. Whittemore again failed in this effort. H. B. Mayo replaced Whittemore as custodian on October 2, 1899. He inherited Whittemore's concern for a roof. Consequently, Mayo contacted a "good" Los Angeles architect who recommended an asphaltum roof. The architect estimated that, whether an asphaltum or corrugated iron roof were used, the cost would be $2,000. Surprisingly, in February 1900, the secretary of the interior requested a $2,000 appropriation to roof the Great House. A number of Florence residents added their support for a roof by prevailing upon a local General Land Office agent to contact the General Land Office commissioner with their concerns. This local agent, S. J. Holsinger, described the ruins as "fast going to pieces." He urged the General Land Office commissioner to provide for a roof to protect the Great House. Congress, however, did not approve the funds. [27]

In his annual report for fiscal year 1900, Custodian Mayo stated that he had visited the ruins from three to six times per month and had thoroughly inspected the Great House at least twice per month. Mayo wrote that his other duties included preventing settlement and wood cutting on the reservation as well as guarding against the ruin's defacement. He, however, could not prevent vandalism without residing at Casa Grande. Even then he felt that security required a fence around the ruins. Mayo regretted the failure to obtain roof funds. He added that more iron rod braces needed to be placed in the ruins to better secure the walls. [28]

When Mayo filed his annual report for 1901, his uppermost thoughts were for a roof, but he added two other items to the request. He observed that some concrete patchwork was needed in crumbled or undermined portions of the Great House walls and a fence was required for better security. Mayo estimated the cost of these three improvements to be $2,200. By the time the secretary of the interior requested an appropriation for that sum in January 1902, Mayo had vacated the Casa Grande custodianship. When Frank Pinkley, Mayo's successor, penned his first letter to the General Land Office commissioner in February 1902, he attempted to undo the work of the past twelve years. Pinkley stated that he did not recommend a roof for the Great House because it would mar the view of it and, besides, he did not believe the wall tops were wearing away. In addition, he saw no need for a fence. Since there was no forage within 100 yards of the Great House, he thought that range cattle would not stray into the area. Pinkley soon changed his mind. [29]

|

| Figure 13: Boundary Changes. |

C. Frank Pinkley's First Tenure

When Frank Pinkley arrived at Casa Grande in December 1901, he began the first of two lengthy residencies there. His appointment marked a short, renewed interest in Casa Grande by the General Land Office perhaps because the ruins now had a resident custodian. Pinkley was a mere youth of twenty at the time he accepted the custodianship of this first reserved cultural site. He was born on May 27, 1881, about four miles south of Chillicothe, Missouri. After high school in 1898, he worked in a Chillicothe jewelry store. In the fall of 1900 a doctor found that Pinkley had tuberculosis and ordered him to go to Arizona. He arrived in Phoenix in September and spent several months in a desert camp following which he and a cousin leased a small farm. [30]

Toward the end of 1901, Pinkley's uncle, the General Land Office commissioner for Arizona, offered his nephew the job as Custodian of Casa Grande. He accepted the offer. On December 14, 1901, Pinkley received his instructions from the commissioner of the General Land Office. These read:

You will immediately assume charge of the reservation and take the necessary steps to protect the said ruins and to prevent any settlement or encroachment on the said reservation. In order to do this most satisfactorily you are directed to live upon the reservation within the immediate neighborhood of said ruins. If no part of the ruins is habitable you are authorized to erect such building as you choose thereon without expense to the government.

Your daily presence on the reservation is required and you are not to absent yourself there from, unless after obtaining a regular leave of absence from this office.

Blanks are forwarded to you as well as envelopes, under separate cover. Upon the report blanks you will at the end of the month fill out the lines thereon, reporting the condition of the reservation and the number of days in each month, which you remained thereon, as well as any other information you may deem of interest to the Department. [31]

Although his salary of $900 per year more than doubled that of the previous custodians, Pinkley could not afford to build a residence at Casa Grande at first. Instead, he lived in a tent just east of the enclosure which came to be known as Compound A. Within a short time, he constructed a frame with a cast-iron roof over the tent. The shade obtained from this arrangement reduced the summer heat inside of his dwelling. This living quarters served until 1906 when he built a frame-sided tent. He also dug a forty-five-foot-deep well. Soon, his parents moved to Arizona and, in March 1902, he received permission from the General Land Office commissioner for them to live at Casa Grande with him. His father Sam was an invalid. As a means to augment his annual salary, Pinkley opened a trading post at nearby Blackwater. His parents operated it for him. By 1905 he met Edna Townsley. Her father had brought his family to Arizona from Vermillion, South Dakota, when he accepted a teaching position on the nearby Gila River Reservation. Frank and Edna were married in 1906. [32]

From his beginning at Casa Grande, Pinkley displayed an innate organizational ability despite his youth. He had his vision of how to develop and promote the ruins. Although, in his first correspondence with the General Land Office commissioner on February 6, 1902, Pinkley discounted the need for a roof or fence, he gave a thorough account of the ruin as he found it as well as a description of the surrounding countryside. He included a short summary of the repairs he felt were needed for the Great House. Pinkley requested that the reservation boundary be surveyed and marked, and the entrance roads be posted to discourage curio seekers and native wood cutters. He asked that the $300 fine for defacing the Great House be extended to cover anyone caught excavating or removing artifacts. Finally, Pinkley sought permission to excavate the surrounding mounds. He believed that excavation would not only further scientific knowledge, but it would also attract national interest and, therefore, promote visitation. [33]

After reading Pinkley's first report, the General Land Office personnel made two separate replies. One response involved the boundary survey, entrance posting, and fine extension. The agency leadership discounted the need for a boundary survey since the reservation had been established in accordance with government surveys. Posting the entrance roads was a good idea, the assistant commissioner believed, but no funds were available to do so. The agency, however, had no objection to Pinkley using his own money to erect entrance signs. No one in the General Land Office understood the reference to a $300 fine for defacing the Great House, and the assistant commissioner asked Pinkley to explain. Pinkley did not know that Isaac Whittemore had posted this unauthorized warning. All he could reply was that, when he arrived at Casa Grande, a sign existed on the Great House; therefore, he concluded that some law authorized the fine. Since no legal authority existed for a fine, Pinkley was instructed to report any cases of theft of government personal property so the offender could be prosecuted under existing larceny laws. Since artifacts were not personal property, Binger Hermann, the General Land Office commissioner, asked the secretary of the interior to recommend to Congress that it authorize the secretary

to make a provision for the preservation and protection of the [Casa Grande] reservation against destruction or injury by defacing buildings or ruins, by excavation, by removal of curios, or any other wilful injury to the ruins.

Hermann suggested that a $500 fine and/or imprisonment not to exceed twelve months be levied against those convicted of such activity. Whittemore's posting and Pinkley's inquiry aided the move which led to the 1906 Antiquities Act. That act established, for the first time, a legal basis to prosecute anyone excavating or removing artifacts from public property. [34]

The General Land Office commissioner's other correspondence with Pinkley involved ruins repairs. Although Pinkley had summarized repair needs in February 1902, the commissioner asked for exact requirements. Consequently, Pinkley got George Eaton, the mason for the 1891 repairs, to help him specify areas needing repair as well as the quantity of materials. They identified five doors and windows in the Great House with missing lintels. In addition three large cavities required brick and mortar fill. The walls of the ruins to the south and to the east of the Great House needed underpinning. In a letter to the commissioner, Pinkley listed the quantity of repair material and its estimated cost, including labor. He thought that $880 would cover the repairs. The General Land Office commissioner felt that Pinkley had underestimated the cost and that it would be closer to $1,000. As a result, Pinkley was asked in July 1902 to make another report of the repair needs. Pinkley provided the same quantity for materials. On this occasion, he raised the cost for material and labor to $1,019.35. [35]

In the meantime, the secretary of the interior requested a $2,000 appropriation for fiscal year 1903 for ruins protection. That sum was included in the Sundry Appropriation Act of June 28, 1902 (32 Stat. 454). Despite the fact that Pinkley had been sending repair estimates to the General Land Office, the commissioner wrote to the local General Land Office agent on September 9, 1902, with the request that he inspect Casa Grande. S. J. Holsinger, the local agent in the Phoenix office, arrived on October 22. After viewing the ruins, Holsinger decided that no improvement was needed as much as a roof over the Great House. He said that Pinkley concurred with him. Pinkley had changed his mind about the roof after the July and August rains had seemingly eroded more material from the Great House than he had expected. Holsinger secured the necessary data from which to design a roof. He decided that it could not take the form of Victor Mindeleff's 1890 design, which had all the support posts inside the ruin. [36]

While he was at Casa Grande, Holsinger looked at areas of the ruins that Pinkley had indicated required repair. He decided that no more brick or concrete should be used on the ruins as Pinkley had proposed, instead any restoration work should be done with as much original material as possible. He had Pinkley make a mixture from the debris and apply it to several cracks to see how it worked. Holsinger pronounced the effort a success. Holsinger also indicated a source for future repair material. He wrote that Pinkley had recently dug a forty-five-foot-deep well. At the seven-or eight-foot level, he had encountered a stratum of cemented gravel which was identical with the original construction material. That soil could be used for future repairs. As for the replacement of lintels, Holsinger thought that reservation mesquite would serve the purpose. [37]

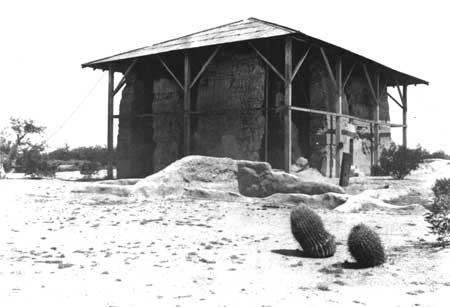

By May 1903, Holsinger had designed a covering for the ruins. It had a galvanized, corrugated iron roof with a six-foot overhang. The framework was supported on 10-by-10-inch redwood posts set four feet in the ground. Anchor cables ran from the top of each corner to dead-men set twenty feet away. An advertisement for construction bids was made toward the end of May 1903. By June 8, Holsinger had received two bids from Phoenix, each for just under $2,000. These were followed by a $1,900 bid from W. J. Corbett of Tucson. Corbett was awarded the contract on June 22. Work was to be done by September 22. Corbett's men arrived on August 25, 1903 and immediately noticed a mistake. The Great House walls were two feet higher than stated in the specifications. Consequently, the 10-by-10-inch redwood posts could only be set two feet into the ground. The roof was completed on September 10, 1903, with one change order of an additional $75 to paint it (figure 14). It must have presented a terrible contrast with its surroundings because the roof was painted with one coat of red paint to protect the corrugated iron. [38]

With the roof completed, Pinkley turned his attention to an appropriation for excavations. He had asked for permission to excavate in his first report of February 1902. Without waiting for a reply, he wrote on March 1, 1902 that he had "found" four stone axes, a stone wedge, and two bowls. That statement proved to be a mistake for Pinkley. Binger Hermann, the General Land Office commissioner, believed that the prehistoric antiquities of the Southwest had to be protected from indiscriminate excavations made by untrained individuals. To permit such exploratory digging fell into the same category as tolerating the looting being done at other ancient sites. Hermann believed that only trained archeologists should conduct excavations. Consequently, he wrote to Pinkley that all excavations would be under the control and supervision of the Bureau of Ethnology. Pinkley accepted that pronouncement, and, when he requested a $2-3,000 appropriation for fiscal year 1904 for excavations, he made it clear that he understood that the Bureau of Ethnology would be involved. With no money forthcoming for 1904, Pinkley again made excavation funds his only request for fiscal year 1905. On this occasion, in May 1905, Scott Smith came to confer with Pinkley and make a recommendation for an investigation. No records remain of this meeting, but Pinkley did get his excavation appropriation for fiscal year 1907. J. Walter Fewkes of the Bureau of Ethnology was appointed to conduct the work. He was instructed to inspect the ruins for needed repairs in addition to excavations. Fewkes had visited Casa Grande in April 1891 before Mindeleff had repaired the Great House, so he was no stranger to the area. When he arrived on October 24, 1906, he examined the remains and concluded that the Great House was in fair condition. Several doors and windows in that structure needed lintels and the roof badly required paint. Fewkes concluded that the Great House covering was no thing of beauty and ventured that it should have had a mission style architectural design. Moving from the Great House, Fewkes found that the ruin fragments to the south and to the east needed to have their foundations strengthened. As a result, Fewkes made minor repairs and painted the roof. [39]

|

| Figure 14: The First Ruins Shelter Roof Constructed in 1903. This ca. 1925 photograph sows the anchor cables that provided stability. Courtesy of the Western Archeological and Conservation Center. |

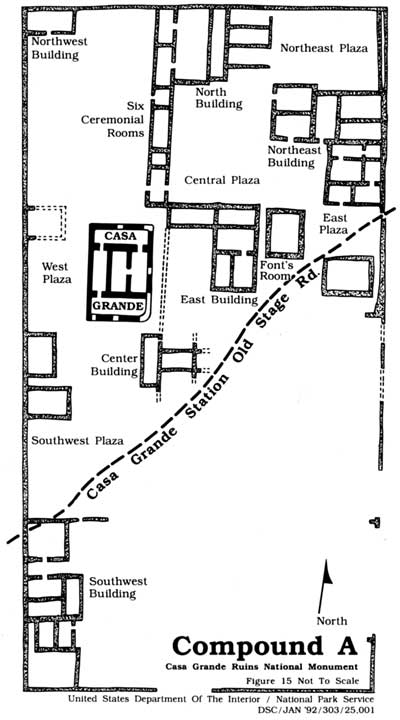

To develop an excavation plan, Fewkes systematically viewed the Casa Grande ruins. He determined that most of the ruins could be characterized as laid out in rectangular areas which were surrounded by walls. The remains inside the walls were rooms, courts, and plazas. Fewkes decided to designate each rectangular walled area as a compound. Having found six such compounds at Casa Grande, he named them A, B, C, D, E, and F. Because the Great House was the most important building in the largest compound, he called its enclosure Compound A. Fewkes also identified another class of ruins which he termed clan house. These remnants consisted of single buildings without a surrounding wall. He found the remains of four such structures of which two were east and two west of Compound A. [40]

After completing his survey, Fewkes decided to expose prehistoric remains, and repair and preserve them. He felt that, since the ruins at Casa Grande resembled other unique prehistoric remains in the Gila Valley, these uncovered remnants would then "serve as a type with which to compare and to interpret" other similar mounds in the region. [41]

During the winter of 1906-07, Fewkes expended the $3,000 appropriation for work in Compound A where he excavated and repaired the compound wall, buildings, and plazas. Approximately sixty percent of the area was exposed, which included forty-three rooms, and several courts and plazas (figure 15). He removed a great amount of debris from the compound. Wall protection included laying concrete at wall bases on an inclined clay plane to carry water from the newly exposed walls, and grading the compound surface so that water would be drained through a large ditch at the northeast corner. Fewkes also diverted the old stage road, which crossed the compound, to pass around its southern end. [42]

In the course of the 1906-07 excavations, Fewkes recovered some 1,000 artifacts which he shipped to the Smithsonian Institution. Custodian Pinkley objected because he thought it would be better to keep such implements and utensils at Casa Grande where they could be seen in their surroundings. He requested a $2,000 appropriation to construct a museum in which to display Casa Grande artifacts. Richard Rathbun of the Smithsonian Institution answered Pinkley by citing the statute which read, "all collections, rocks, minerals, soils, fossils, and objects of natural history, archaeology, and ethnology" made by any federally funded group had to be deposited with the Smithsonian Institution. He did consent to leave some items at Casa Grande. No money for a museum, however, was forthcoming, so Pinkley displayed artifacts on home-made shelves in the north room of the Great House. [43]

|

| Figure 15: Compound A. |

|

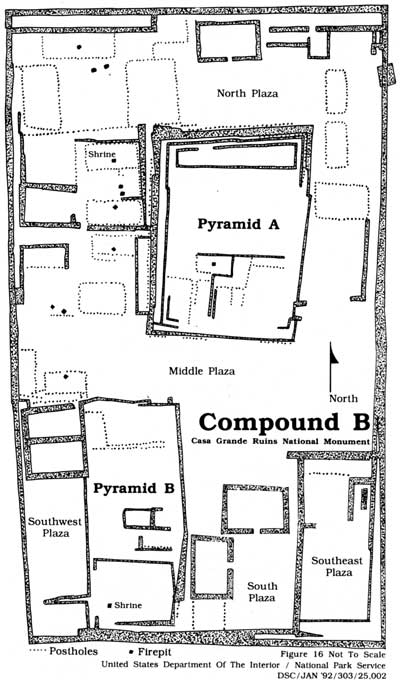

| Figure 16: Compound B. |

An additional $3,000 appropriation made it possible for Fewkes to return to Casa Grande during the winter of 1907-08. On this occasion he focused on Compound B where he did extensive excavations, including exposing the surrounding wall. At this site he found two large pyramids which had rooms on top of them (figures 16 and 17). He installed a drainage system by digging a ditch around the whole exterior Compound B wall. Fewkes also did some work at Compounds C and D and Clan House 1. He found that Compound C was covered with rows of houses while Compound D had a massive central building. Clan House 1 was a self-standing structure composed of eleven rooms around a plaza. [44]

Beginning with his annual report for fiscal year 1905, Pinkley sought to expand the area under his supervision. He asked that three parcels of land located three, five, and eight miles to the east of Casa Grande be withdrawn from settlement and placed in his charge to prevent excavations. Among these three properties were the Adamsville and the Escalante ruins. The secretary of the interior noted that two of the three tracts had been temporarily withdrawn for the San Carlos water storage project. Authorization to have the third plot (N-1/2 of Section 27, Township 4 South, Range 9 East) temporarily withdrawn from settlement and placed under Pinkley's control was granted on May 9, 1906. It is not known how long he administered this tract of land because no references are made to it in National Park Service records. He campaigned through fiscal year 1910 for the other two parcels of land, but without success. [45]

Having gained an additional 320 acres under his administration, Pinkley's ambition to spread his control to a much broader base surfaced. In his 1906 annual report, he suggested that all the ruins on forest reserve and Indian reservation land in Arizona be placed in his care. To acquire supervision of these sites would have given Pinkley a far-flung empire of thousands of acres. He admitted that "I could not, of course, give each particular group of ruins much care, but I could make a visit at least once a year to each group, post notices that they were under the care of the Department [of the Interior] and prevent in every way possible further depredations." Pinkley also assured the General Land Office commissioner that his duties at Casa Grande would not be neglected because his father, though an invalid, could act in his stead. No reply to this proposal exists, but the General Land Office commissioner, no doubt, told Pinkley to curb his desire because he never again proposed such a scheme during his first tenure at Casa Grande. [46]

In his 1906 annual report, which he wrote on July 16, 1906, Pinkley also asked to have some printed literature such as a free pamphlet to distribute to visitors. He continued to ask for such material in each of his annual reports until, almost seven years later, in May 1913, Pinkley's request was fulfilled. This thirty-one-page pamphlet thoroughly described the ruins and gave information about the early Spanish expeditions there. The pamphlet author also advised that, because of the extreme heat, visitors should not plan to view the ruins in the summer. [47]

By 1909, Pinkley began to submit only one page annual reports. They basically indicated that there had been no appropriations and no money spent at the ruins. His requests for a museum building and interpretive material went unanswered. In the 1910 annual report, Pinkley began to comment that the exposed ruins had begun to suffer the effects of erosion "from which there seems no practical method to protect the greater part of them." In the zeal to understand more about the inhabitants of Casa Grande, the excavated ruins had been left to the elements. [48]

In 1909 the first external pressure on the reservation occurred. A demand arose to decrease the reservation boundary by restoring 120 acres of Casa Grande land, located in Section 9, to the public domain (see figure 13). This action was viewed as necessary because, it was thought, the reservation occupied land required for an irrigation canal. Pinkley contacted J. Walter Fewkes to ask his opinion of the proposed withdrawal. He observed to Fewkes that, if the 120 acres were removed from the north side of the reservation, then a 120-acre tract along the east side should be added. Fewkes had no objection to removing the 120 acres in Section 9 because he did not think it contained any outstanding ruins. He also agreed with Pinkley that the reservation acreage should not be reduced, but, instead, an exchange be made to acquire the 120 acres on the east side. This area, he felt, contained some important mounds. Consequently, when President William Howard Taft issued Proclamation No. 884 on December 10, 1909, the reservation boundary was not merely reduced by 120 acres on the north side. In exchange for the loss on the north side, the reservation was expanded to the east in Section 16. [49]

For fiscal year 1910, Pinkley decided that he needed a house to replace the semi-tent accommodation that he and his wife had inhabited since 1906. He asked for a $2,500 appropriation to build a custodian's residence, but, as with his other requests for funds, he was turned down. Using $600 of his own money, he constructed a one-story adobe house in the unexcavated southeast corner of Compound A (figure 18). Local Pima Indians made and laid the adobe while he did the carpentry work. [50]

By 1912 Pinkley's well began to cause a problem. The wooden curbing had rotted. He requested that the General Land Office provide $75 to repair it, along with $150 to purchase a small gasoline engine or windmill to lift water from the well for visitors' convenience. That agency chose to ignore Pinkley's request until July 1914 when he informed the commissioner that, if funds were not forthcoming to fix the well, he could not supply visitors with water. The General Land Office leadership replied that it had no money with which to repair the well. Perhaps this response caused Pinkley to decide to seek another vocation, for he soon determined to run for the state legislature. [51]

One other issue which Pinkley raised during the last four years of his first Casa Grande tenure was the need to repaint the roof and support members of the Great House cover. At first he estimated the cost for paint and labor to be $75, but he later raised that figure to $100. No funds were approved for this task. [52]

In November 1914 Pinkley won a seat in the state senate and, as a result, had to resign as Casa Grande custodian before taking office. Since the state legislature did not meet until later in 1915, Pinkley remained at the ruins into that year. His final annual report, written on September 1, 1915, consisted of five sentences. Basically, he noted that erosion was still occurring and, therefore, an appropriation was needed to repair and protect the ruins. [53]

|

| Figure 17: Compound B Ca. 1925. One of the compound pyramids is visible. The stakes insde of the compound wall outline various rooms. Courtesy of the Western Archeological and Conservation Center. |

|

| Figure 18: Frank Pinkley's 1910 House, Ca. 1925. The 1921 room addition is visible at the left corner. The house was lcoated within Compound A. Courtesy of the Western Archeological and Conservation Center. |

D. The James P. Bates Interlude

Following Pinkley's departure, several candidates sought to become the new custodian at Casa Grande. Seventy-two-year-old James Polk Bates was selected. Bates had been born in Kentucky in 1843 and, during much of his life, he had worked first as a druggist and then as a lawyer. He came to Arizona in January 1907 and resided in Phoenix. Bates assumed the custodian position on December 1, 1915. According to his 1916 annual report, the situation at Casa Grande was even worse than Pinkley had indicated. He wrote that, when he arrived at the ruins, he found that both whites and Indians had been constantly removing mesquite for wood and fence posts. He stated that, for the most part, he had succeeded in ending this practice. Another irritation stemmed from the fact that ranchers permitted their cattle and horses to graze all over the reservation. At night the stock would rub against the ruins' walls and cause irreparable damage. These animals had also created paths over the mounds. Bates asked that a fence of five barbed wires be placed around the entire 480 acres. [54]

Soon after his arrival, Bates asked for funds to improve the well and to purchase an engine and pump. He received $300, but he considered this sum to be insufficient. He wrote that the pine used for the well casing had rotted making the water impure and posed a danger to anyone attempting to repair the well. Bates wanted to abandon the old, weak-flowing well and drill a deeper one closer to the custodian's house. As a resuit, he asked for an additional $200 for a well and an upright tank. With this greater water supply, Bates hoped to cultivate a small garden and raise some rapid-growth shade trees for the visitors' comfort. [55]

While Bates wished to provide for the visitors' comfort, he also wanted to keep them from driving randomly about the reservation. He noted that the main road, which entered the southwest corner of the Casa Grande land and exited to the northeast, had no lane to restrict individuals from leaving it. In addition Bates felt that gates should be put across other roads that entered the reservation. [56]

The condition of the Great House roof and the ruins in general did not escape Bates' attention. He recommended that a new, galvanized iron roof be constructed over the Great House because the old one had holes in it. Bates feared that water leaking through the holes would cause the wood frame to deteriorate. He wrote that the excavated ruin walls remained exposed to the elements and had begun to crumble and fall. In Bates' view, they needed a top coating of concrete to keep them from wearing away. [57]

As his final request in the 1916 report, Bates asked for a Ford or other car of that class. Such a vehicle would aid his travel to Florence for mail and supplies, he thought. [58]

The General Land Office commissioner saw the creation of the National Park Service (NPS) on August 25, 1916, as the means to sever ties with Casa Grande. Although the General Land Office chief clerk soon discovered that the Park Service organic act did not permit the transfer of Casa Grande to that bureau, the General Land Office commissioner was eager to distance his organization from that reservation. Until a transfer could be legally accomplished, the commissioner took steps to have the custodian report to the Interior Department. Starting in 1917, Bates sent his reports to the chief clerk of the Interior Department instead of to the General Land Office. [59]

Reporting directly to the Interior Department did not change the funding circumstances for Casa Grande. In fact fate seemed to deal harshly with James Bates. In late July 1917 a windstorm blew the roof from the custodian's house. He succeeded, in this instance, in getting the Interior Department to quickly approve a new roof. At the same time, however, he never got money for a new well, car, or a fence to prevent livestock from entering the reservation. In April 1917, Bates did remove some of the dirt and rotted casing that had fallen into the well, but the casing continued to collapse. By September he pronounced the well to be unsanitary from rotting wood, and decaying crickets and toads. As if that were not enough, the post office in Florence burned just after he had mailed his 1917 annual report. Consequently, he had to rewrite it. Finally, and worst of all, in early 1918 Bates was dismissed from the job after he was caught selling artifacts. This situation opened the door for the return of Frank Pinkley who had managed only one term as state senator. [60]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

cagr/adhi/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2002