|

Casa Grande Ruins

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Arizona: A Centennial History of the First Prehistoric Reserve 1892 - 1992 |

|

CHAPTER IV:

CASA GRANDE RUINS AS A NATIONAL MONUMENT

A. The Transfer to the National Park Service

Despite the fact that the Casa Grande reservation technically remained under the General Land Office after the creation of the National Park Service in 1916, the latter bureau soon became more involved in its administration. This development was welcomed by the General Land Office leadership because it had never felt comfortable managing this prehistoric resource. Except for a brief period from 1902 to 1907, General Land Office commissioners had either tried to deny that the bureau managed the reservation (mid-1890s) or they chose to ignore it (1908-16). Consequently, in the latter part of 1916, the GLO chief clerk began the process by which Casa Grande would be designated a national monument, so that it could be transferred to the National Park Service. This procedure included having the custodian report directly to the secretary of the interior and not to the General Land Office starting in 1917. By the end of that year the secretary of the interior had given the National Park Service jurisdiction over the Casa Grande reservation, even though it legally still belonged to the General Land Office. Under that circumstance, the National Park Service Director, Stephen T. Mather, began a search for a competent custodian. [1]

On January 16, 1918, Mather contacted Frank Pinkley to determine if he would be interested in returning to his old job. To make the position more attractive, Mather wrote that Pinkley would be allowed to operate a concession to add to his income. The salary offer of $900 was the same as he had received each year from 1901-15. Pinkley replied that he did not believe that a custodian should become involved with concession management. He felt that a custodian's efforts should be directed toward resource protection and creating a learning situation through visitor instruction and publicity. If he were to return to Casa Grande, Pinkley told Mather that he would need an automobile although he offered to pay for the gasoline as a means to discourage the vehicle's overuse. After considering the matter, Pinkley wrote to Mather on March 4 that he would accept the job. He announced that his custodianship would be built on the foundation of protection, development, and publicity. In a reply dated March 16, 1918, Mather authorized his appointment as custodian, although control of the Casa Grande reservation still officially came under the General Land Office. [2]

By the time that Pinkley arrived at Casa Grande on April 1, 1918, he had already begun to exercise his authority. Based upon his previous experience at Casa Grande, he began to implement an immediate course of action. Within days of his appointment, Pinkley's first activity was to contract for the erection of a thirty-five-foot-high galvanized-iron flag pole on the reservation. He also contacted Professor Byron Cummings of the University of Arizona Anthropology Department and the State Historian T. E. Farrish who agreed to write pamphlets on the archeology and history of Casa Grande when funds became available. Pinkley began to gather books for a library. He met with the chambers of commerce of the towns of Casa Grande and Tucson and received a pledge from those groups to build a restroom on the reservation. The head of the state news agency agreed to publish stories on the ruins. As for future activities, Pinkley told Mather that he needed road signs and general National Park Service literature for visitors. He hoped to approach the United States Geological Survey to do a topographic survey on one-foot contours for the entire reservation to aid future development. Finally, Pinkley requested that Mather ask the Bureau of Ethnology to investigate a means to harden the ruins walls. He had previously thought of spraying the walls with silicate of soda, but evidently had changed his mind. [3]

Soon Pinkley had his enthusiasm dampened by the reluctance of the National Park Service Washington, D.C. office to champion the cause of his operational needs. Although he quickly received the general information literature on the National Park Service, Pinkley almost as quickly got a letter from Mather's assistant Horace Albright. He learned from this June 7 communication that neither the National Park Service nor the General Land Office intended to offer any present support. Albright attempted to attribute the lack of aid to the fact that, even if the National Park Service had any funds, it would not use any money for improvements on property legally controlled by the General Land Office. Albright observed that, if Casa Grande were to be designated a national monument, then it could be brought into the national park system. Undoubtedly hopeful of a brighter future, Pinkley readily agreed to a change in the ruin's status. [4]

B. The First Years as a National Monument

On August 3, 1918, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed Casa Grande to be a national monument. This change in status, with its inclusion in the national park system, did not produce the results that Pinkley had, no doubt, hoped. It did not bring him any substantial financial aid. He found that Casa Grande shared the same fate as all the other poorly funded national monuments. Consequently, his 1918 annual report reflected his discouragement. He wrote that "nothing" had been done at Casa Grande. There were no funds. Pinkley ended his account by stating that "this report is intended to arouse some interest in the Casa Grande with anyone who may read it." Horace Albright responded that it was a "good report." [5]

Pinkley's plea brought a $500 budget for fiscal year 1919 and more work. Mather notified Pinkley on September 10, 1918, that he had placed him in charge of a second national monument. Two months previously, Mather had advised Pinkley that he might ask him to oversee Tumacacori National Monument. Having a second monument to administer, however, did not seemingly cause Pinkley any deeper distress. He worked tirelessly to operate both national monuments. Pinkley's wife worked as an unpaid aid who ran Casa Grande during his absences at Tumacacori. Pinkley proved to be such a successful administrator that Mather further increased his responsibilities in succeeding years. [6]

Even though Pinkley received a skimpy annual budget, he began to make some improvements at the new national monument. The old well was beyond improving, so, in September 1918, he began to dig a new one. He encountered water at forty feet. While digging the well, Pinkley began to think of improvements in general. He wrote to Mather that his immediate desire was the topographical survey of the monument showing one-foot contours. Pinkley also asked Mather to send Charles Punchard, a National Park Service landscape engineer, to Casa Grande that winter so that a monument improvement plan could be developed. In the following month Pinkley hired a man to clear the brush from Compounds A and B. After that shrubbery had been cleared, Pinkley had his hired man remove the underbrush from an area between Compounds A and B and trim some mesquite trees so that a campground and picnic area could be provided for visitors. [7]

Although Punchard came to Casa Grande in January 1919 to assess development needs, more money for improvements was not forthcoming. Stephen Mather, the National Park Service Director, paid little attention to the national monuments. His focus was directed toward national parks. He considered national monuments no more than "interesting accents" to national parks. Nearly all of Mather's energy was spent in improving access to existing national parks or acquiring additional national parks. Consequently, an overwhelming proportion of the National Park Service budget was spent on these natural scenic areas. National monuments received so little money that even maintaining the status quo was difficult. In 1921 the regular budget for all twenty-four national monuments for repair, protection, and salaries came to only $8,000. It was an insignificant amount when compared to the $60,000 received by the Grand Canyon National Park or the triple figure budget of Yellowstone. Mather had his reasons for concentrating on the national parks. He wished to increase visitation and create a national constituency to support his new agency. The vast, scenic grandeur of national parks, he felt, provided the foundation on which to build a national following. To Mather, the smaller, mostly culturally oriented national monuments, though interesting, lacked glamour. Mather carried this separate and unequal approach to the two entities into administrative titles. The head of a national park was designated a superintendent, while the manager of a national monument was merely a custodian. [8]

Mather's disinterest in national monuments resulted in an increased workload and salary for Pinkley. By 1920 Pinkley was not just custodian for Casa Grande and Tumacacori, for in that year the Park Service leadership found it convenient to unload its responsibilities for a number of Southwestern monuments onto him. Pinkley accepted the new assignment which was for "review of administrative and other conditions in Southwestern Monuments." This fit in well with his ambitions that reached back as early as 1906. Perhaps he also thought that there was strength in numbers; that he could command more attention for budget purposes as representative of a number of monuments as opposed to two entities. The review of "other conditions" brought such duties as inspecting various monuments and even helping with repair work. Renovation work took him to Montezuma Castle National Monument in 1920. Pinkley even filed an annual report for Montezuma Castle in that year. Soon he was traveling to inspect Chaco Canyon, El Moro, Petrified Forest, and Pipe Spring. On occasion, this extra work was considered confidential. Pinkley also had contact with the custodian at Aztec and had suggested a custodian for Gran Quivira. For this new responsibility, his salary increased in 1920 to $1,320. [9]

Pinkley performed his assignments with such efficiency that the National Park Service's leadership decided to officially recognize his work by establishing a field headquarters at Casa Grande from which national monuments in a four-state area of the Southwest would be managed. While he attended the annual National Park Service conference in Yellowstone National Park in October 1923, the announcement was made that Pinkley had been appointed as superintendent of the Southwestern National Monuments. He had twelve monuments to manage with a thirteenth created the following month. Pinkley also retained the custodianship of Casa Grande which he kept until July 1, 1931. With this increased workload, Arno Cammerer, the assistant director, recognized that Pinkley needed help, so he allotted Pinkley a $300 budget for an individual who would work part time at Casa Grande while he traveled. Pinkley hired George L. Boundey because he had "previous experience" in mound excavation. By the start of fiscal year 1925 on July 1, 1924, Pinkley had created a full time position at Casa Grande for Boundey. [10]

C. The Development of Casa Grande Ruins National Monument

The development of adequate facilities for employees and visitors was a constant struggle. Rarely were sufficient funds available to meet all of the needs. Even the creation of the Southwestern National Monuments field office did not bring much development money in the 1920s. Most of the construction funds came during the depression era of the 1930s. The last development period, in the early 1960s, evolved from the National Park Service MISSION 66 program.

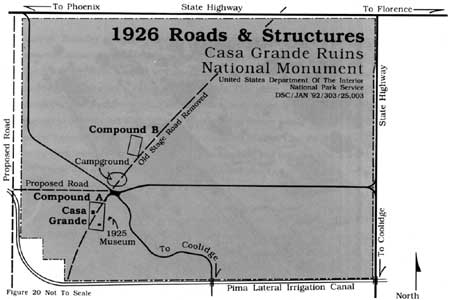

After Pinkley had expended his $500 appropriation for fiscal year 1919 on removing brush from Compounds A and B, creating a crude picnic and camping area, and digging a new well, funds evaporated for two years. In January 1919 Charles Punchard's visit to formulate a development plan brought no action. In his 1920 annual report Pinkley bemoaned the lack of money. People who hoped to camp at Casa Grande had no pleasant place to do so. Range cattle wandered over the monument without a fence to stop them. These roving livestock were more than a nuisance, they also damaged the ruins. [11]

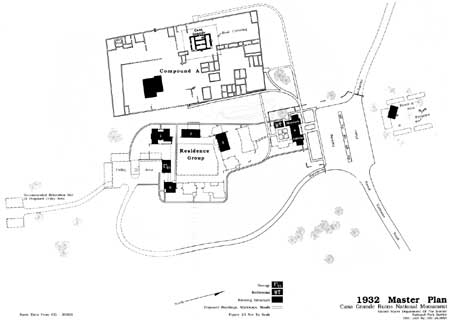

The financial picture brightened for fiscal year 1922. Casa Grande received a $2,000 appropriation of which $1,200 was specified for a museum building. With the knowledge that funds for a museum would be provided, Pinkley had Punchard deliver building drawings by June 30,1921. Construction did not occur as rapidly. The planned start for the structure in March 1922 was delayed because rain prevented the Pima laborers from making adobe. By April 3 the weather had cleared and work began on the five-room, fifty-by-twenty-two-foot museum. It had a concrete foundation and floor. The adobe walls were stuccoed on the outside and plastered on the interior. The final cost was $1340.31. [12]

While waiting for the construction to begin on the museum, Pinkley used $243.83 of the 1922 appropriation to improve his dwelling. He added a room and a screened porch to the quarters in the December 1921 and January 1922 period. [13]

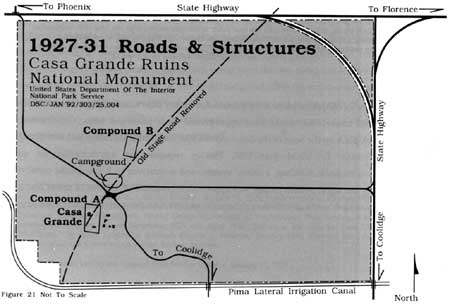

Pinkley did not receive any money for a much needed storage facility. To house monument equipment, he had resorted to constructing makeshift buildings out of scrap lumber. These unsightly structures were located out of view of visitors. [14]

In mid-1924 external pressure was brought to bear on the monument once more. On this occasion the Casa Grande land stood in the path of an irrigation canal being constructed through the area. In the 1880s white settlers had come to the Florence region because of the seemingly abundant flow of water in the Gila River. These men had constructed a crude dam on that stream about twelve miles above Florence to divert water for irrigation. With time, as more land was irrigated, quarrels began over water rights. All the while, the Pima, who irrigated land farther downstream, obtained less and less water for their fields. As a result, the Pima made their own claim for water. These conflicting interests led the United States Government to authorize a large dam on the Gila River on May 18, 1916. Dam construction, however, could not begin until an agreement was reached on how to divide the water among the various users. A settlement was reached in April 1919 at a meeting held by the secretary of the interior in Los Angeles and, thus, preparation began to build the permanent diversion dam. For a time in 1919 Pinkley sought a share of the irrigation water by which to develop a park area with trees and shrubs for visitor comfort, but his application for water was disapproved. [15]

Funds for the dam included construction of adequate irrigation ditches to replace the crude ones in use. Water for use by the Pima on the Gila River Indian Reservation was to flow there in a ditch constructed by the United States Indian Service. The route to be followed by the Pima Lateral Canal, as the ditch came to be called, was determined in June 1924. The U.S. Indian Service planned to construct the canal across Casa Grande monument land. When asked, the Interior Department Solicitor stated that it would take an act of Congress to place it there. Despite that judgment, the Indian Service told Pinkley that no other location was feasible. Pinkley sent a telegram to the National Park Service director on November 24, 1924, to ask if agency policy should be to agree with or oppose the route. Acting Director Arno B. Cammerer replied that the Park Service could release sufficient land on the monument just inside the east and north boundaries on which to build the canal rather than have it cross the monument. On November 30, 1924, the Indian Service engineers came to Casa Grande to look at the east and north boundary area. Pinkley, who thought that route would take too much monument land, proposed that they locate the Pima Lateral Canal just outside the south and west boundaries. The Indian Service engineers told Pinkley that the south and west route would be feasible if the canal right-of-way could cut through the southwest corner of the monument. This situation would require giving up 7.5 acres of monument land. Pinkley wrote to National Park Service Director Mather to state that he had agreed to permit the canal to go through the southwest corner of the monument. Mather supported that decision. Consequently, that small corner of the monument was returned to the public domain by Public Law No. 342 on June 7, 1926 (see figure 13). No succeeding legislation gave that 7.5-acre tract to the Indian Service. It remains to this day as part of the public domain. [16]

The Pima Lateral Canal proved to be troublesome. The heavy amount of silt deposited in the canal had to be cleaned regularly. As a consequence, when the Indian Service removed the silt it would dump it on the edge of the monument land. By 1933 this silt had been piled along 4,570 feet of the south and 630 feet of the west boundaries up to thirty feet inside the monument. In April of that year, Hilding Palmer, the Casa Grande custodian, notified the Indian Affairs commissioner that the Indian Service could dump no more silt on the monument. It had destroyed trees, brush, and cactus. Some of this silt was removed when the boundary fence was installed in 1934, but the Indian Service kept piling silt along the west boundary. As a result, in 1939 that boundary fence had to be taken down and the dirt removed. The Indian Service then installed a new fence along that 630-foot section. [17]

Misfortune struck the monument on September 25, 1925, when a storm system stalled over the area and produced an excessive amount of rain. Flooding, as the result of the downpour, weakened the museum building's adobe walls and caused the structure to collapse. Pinkley and Boundey were able to remove the artifacts and interpretive material while the structure was still intact. Boundey and his family, who lived in one of the rooms, evacuated the museum without a loss of their personal effects as well. Within ten days the National Park Service Washington office allocated $1,200 from an emergency fund to replace the museum. Pinkley reconstructed the building by using the old concrete foundation, and thus its cost was $273.96 less than the original expenditure. By the end of January 1926, it had been rebuilt and the collection moved back into it. [18]

George Boundey and his family returned to their museum quarters since no other accommodation was available for monument employees. By 1927 Pinkley had developed a plan for future employee housing at Casa Grande. He desired a residential compound with the buildings fronting on a common patio center. This patio area, Pinkley thought, could be developed into a garden without affecting the outside desert. In the early part of 1928 he began a quest to develop this plan. When it appeared that money would be approved to construct a ranger's quarters after July 1, 1928, Pinkley contacted Thomas Vint, the chief landscape architect in the Park Service's San Francisco Field Headquarters, and told him that it "must be of adobe walls to fit into the surroundings ..." Construction began on the residence in November 1928 and it was completed by April of the following year (figure 19). [19]

Although Pinkley had his vision of monument development and had obtained funds for a ranger residence, Thomas Vint decided to visit Casa Grande to make sure that eventual construction was carried out with an orderly plan. In early December 1928, Mr. Vint arrived at Casa Grande to discuss future development with Pinkley. At the time, construction on the ranger's quarters had just begun. Vint liked the southwestern adobe architectural style embodied in the Casa Grande buildings. He, however, did not think much of the museum's internal arrangement. It was not laid out for the purpose that it served. The museum was also situated too close to the new ranger habitation. In Vint's view, building arrangements should be grouped separately on a functional basis. Although poorly designed to serve as a museum, he concluded that the building could be easily converted to a residence. Vint thought that its location, combined with the new ranger dwelling under construction, could form the first structures in Pinkley's desired residential compound (figure 20). A new combination administration/museum building, with adequate visitor parking, needed to be built as a separate unit to the north of the residential group. Pinkley agreed with Vint's development ideas. Vint also stressed the need for a utility group composed of a garage and a warehouse. [20]

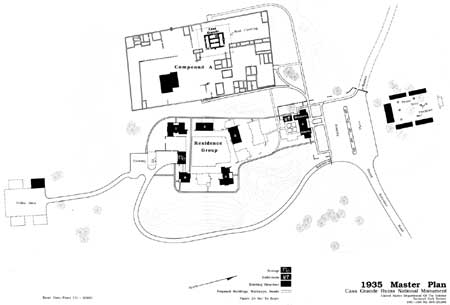

|

| Figure 19: Ca. 1931 Aerial View. The 1903 Great House roof is visible with the roof patch which was needed after the June 1930 windstorm. Pinkley's 1910 dwelling is visible above the Great House. The first building to the left is the 1929 ranger residence. Above the 1929 dwelling is the 1925 museum with the visitor parking lot above it. Courtesy of the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument |

Although these development plans were discussed, a master plan was not begun until 1932. In the meantime, construction funds were appropriated on a piecemeal basis. Construction, however, took place on the basis of the development plan that Vint and Pinkley had envisioned for Casa Grande. For fiscal year 1930, Pinkley requested an appropriation for an administration/museum building, a sewer system, and a structure to house public comfort stations. Only the sewer system money was approved. It consisted of 430 feet of sewer line, a redwood septic tank, and a distribution gallery. Construction on this system began in January 1930 and was completed by June. The tank and distribution gallery were located to the northeast of the new ranger residence. [21]

The construction appropriation for fiscal year 1931 must have seemed to Pinkley as if his dream had finally come true. Funds were provided for five buildings and a new well. These structures included the administration/museum building, a comfort station, two employee quarters, and a tool and implement shed. Mr. Vint sent the drawings to Pinkley on May 4, 1931, and began to prepare an announcement for construction bids. He had originally designed the administration/museum building to be built as a square with an open center, but the appropriation was only sufficient to complete the front part of that square. The detached restroom building to the museum's rear gave the museum/administration structure an L-shaped appearance. Assistant Landscape Architect H. A. Kreinkamp arrived at the end of May to prepare to oversee the construction. He rearranged the residential locations slightly in order to retain as much of the mesquite and creosote bushes as possible. The bids were opened on June 15 and Albert Coplen of Mesa, Arizona, won the contract for all five buildings with a combined bid of $19,432. The buildings had been designed in a modified Pueblo architectural style to complement the others on site. Dirt for the adobe brick came from the debris that Fewkes had removed from Compound A during his excavation and grading of that area in 1906-07. This earth had been dumped in an "unsightly" pile just outside of that compound. These structures were completed on January 5, 1932, including an adobe wall which partly enclosed them. One residence served as Pinkley's new quarters while the other building housed the new Casa Grande custodian. At the same time the old museum was converted into a residence. A well was dug in July 1931 to a depth of 186 feet. Water was encountered at 70 feet. Two, 525-gallon water storage tanks and a deep well pump were purchased to go with the new well. [22]

|

| Figure 20: 1926 Roads and Structures. |

|

| Figure 21: 1927-31 Roads and Structures. |

Fiscal year 1932 brought an appropriation to grade and asphalt the surface of an entrance road, construct a visitor parking lot for the new museum building, improve the picnic grounds, build a fence on two sides of the monument, and purchase an electrical generating power plant. A debate occurred on the appropriate road to designate as the entrance road. The old stage road which ran diagonally across the monument land from northeast to southwest ceased to exist by late 1925. At that time Pinkley got Pinal County to construct almost two miles of new roads on the monument. These new roads permitted visitors to converge on the museum area from three entrances — one from the northwest corner, one from the south, and a third on the east center (figure 21). This situation allowed visitors too much unrestricted access to the monument. Only one entrance road was needed. Kreinkamp from the San Francisco Field Office favored the northwest as the entrance road. Pinkley, however, settled on the east entrance road. Soon thereafter, Pinkley stepped aside as Casa Grande custodian and chose Hilding Palmer to fill the position. Palmer wrote to F. A. Kittredge, the Park Service chief engineer, that he wanted the road constructed with an abrupt drop at the edges and a ditch deep enough to prevent cars from driving off the road. In this manner he hoped to end the practice of people driving their cars off the roads into the brush where they ate lunch, built fires, and, in general, destroyed the resources. Palmer cautioned that digging deep ditches had to be done carefully since he did not want the natural vegetation destroyed. Road construction was completed in January 1932 with an entrance that contained a pair of ornamental wooden gates fixed to large, adobe covered concrete gateposts. An "artistic" copper sign was placed just outside the gates. The road led to a new forty-six-car parking lot on the north side of the museum. Ten tables, seven fireplaces, and two ramadas were made for the picnic ground which was located just north of the parking lot. At the same time the north and east boundaries of the monument were enclosed with a forty-five-inch-high woven wire fence hung on steel posts and topped with two strands of barbed wire. [23]

In addition to the fiscal year 1932 construction funds, Congress appropriated money to construct a new shelter roof over the Great House. By the mid-1920s it had become apparent that the old roof had deteriorated to the point that it needed replacement. In 1928 Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., acting in an advisory capacity to the National Park Service, sketched a design for a new roof.

The thought at the time, however, was that a design competition should be held for the roof. Consequently, a number of individuals submitted roof plans, but no action was taken because construction funds were not forthcoming. The force of nature helped to speed the process when wind blew part of the old shelter roof off the structure in June 1930. Acting National Park Service chief engineer A. W. Burney selected a design with a concrete roof in November 1930. He thought it would last longer and require less maintenance. The chief engineer, F. A. Kittredge, seconded the concrete approach since he believed that it would add weight to hold the structure down. A major concern on the part of Kittredge, Olmsted, and others was not that the roof would be too heavy, but that a large, open roof would be susceptible to an uplift effect by the wind. In other words, it would be similar to an individual holding an umbrella in a windstorm. Kittredge estimated that the new shelter roof would cost $42,500. [24]

Thomas Vint thought long and hard about the design of the new shelter roof. He wanted an arrangement that would let the ruin stand out. Vint noted that "if a shelter is placed over the ruin, it takes an architectural value that can't help but affect a view of the ruins." In March 1931, he advocated a flat roof on a steel frame because "it is as far a departure from the design and material of the ruin as can be obtained. The shelter should be a thing apart from the ruin, rather than blend with it." At the same time Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. wrote to Horace Albright that he preferred a hip roof to a flat one. He seemed to worry less about blending or contrasting the roof design with the ruin than about the effect of the wind. As a result, he thought the roof should be secured with a guy wire arrangement much like the rope system used on a circus tent. [25]

Because of the expenditure to control forest fires in several large parks in the fall of 1931, Pinkley and others were led to believe that the fiscal year 1932 ruins shelter appropriation would be used to offset that cost. Consequently, Pinkley, Vint, and Kittredge could only hope for funds in the next year. To their surprise, the National Park Service Washington office telegraphed the San Francisco Field Office on April 28, 1932, that funds to build the shelter were available and to proceed with the design and specifications. Soon thereafter Horace Albright, the National Park Service Director, urged that the Olmsted plan be followed. Within a month Vint sent the final design to Pinkley. With some exceptions, he followed the design suggested by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. Vint omitted Olmsted's guy wire arrangement and made a change in the cantilever trusses that supported the eaves. Otherwise, the hipped roof supported by leaning posts followed Olmsted's proposal. Pinkley did not like the leaning posts, but Vint thought that they looked better architecturally and were more useful structurally since they allowed for shorter roof trusses. In addition leaning posts had a bracing value. The transite roof covering incorporated glass skylights. A copper-louvered ventilator was designed for the roof's ridge line to reduce upward wind pressure. Consequently, the roof could withstand a wind pressure of forty pounds per square foot vertical uplift which was equivalent to a 100-mile-per-hour hurricane. [26]

Construction bids for the ruin shelter were opened in mid-June 1932. Of the eleven firms that submitted bids, Allen Brothers of Los Angeles, California, a bridge construction company, placed the lowest bid at $20,282. Allen Brothers sublet the excavation and footings to Clinton Campbell and the steel fabrication to the Virginia Bridge and Iron Company of Birmingham, Alabama. Campbell began work on September 19 to excavate for the footings. The old ruins shelter was removed and a temporary shelter constructed over the Great House to protect it during construction. When the new shelter was completed on December 12, 1932, it stood forty-six feet from the ground to the eaves. The highest point of the structure, the top of the monel metal ball used for a lightning rod, reached sixty-nine feet, three inches above the ground (figure 22). Upon completion, the shelter was painted a sage green to harmonize with the mountains and vegetation as well as provide a contrast with the ruin's walls. Its final cost was $27,724.12, which included $4,000 for engineering and design costs. [27]

|

| Figure 22: The 1932 Ruin Shelter Roof. Courtesy of the Western Archeological and Conservation Center |

The shelter has received periodic maintenance which has meant repainting it for the most part. It was repainted for the first time in 1942 at a cost of $513.10. Eight years later, in 1950, another coat of paint was applied. By that time, the cost had more than tripled at $1,597. Small cracks were also noticed to have formed in the legs, but Superintendent A.T. Bicknell was told that these cracks had no effect on the structural soundness. In January 1955, a National Park Service engineer, George Smith, looked at the shelter and saw that the cracks were split welds. He estimated that rewelding would cost $125. This maintenance work, including repainting the welds, was done in April by the Steel Engineering Company of Coolidge. The shelter was painted once more in 1959 along with some resealing and caulking of the roof. On this occasion, J. A. Bridges, the painting contractor, received $2,590. His final coat of sage green-colored paint had a fish oil base. It evidently did not prove to be of good quality because the shelter required paint in only four years. On this occasion, in July 1963, the old paint was sandblasted from the structure. Two zinc chromate primer coats were applied under a vinyl finish coat. Rust-Proofing Incorporated of Phoenix received $11,897 for the contract. In 1974, Mantikas Painting of San Pedro, California repainted the shelter for $8,500. An engineering firm, Collins Engineers Incorporated of Chicago, inspected the ruin cover in 1982 and pronounced it to be in excellent condition. That firm recommended that it be repainted on a ten-year cycle. The shelter received its latest coat of paint between November 1989 and February 1990. The Karvas Painting Company of Yuma applied a Fuller O'Brian 6-99 Oak Bark colored paint for $30,925.68. This coat of paint changed the shelter color from sage green to a light tan. [28]

Returning to more mundane construction following the erection of the new ruins shelter, fiscal year 1933 brought several improvements to the monument grounds. A new one-eighth-mile service road was built and coated with road oil. In the spring of 1933 one-half mile of walkways were laid to connect the administration/museum building to the residences and Compound A. This walkway system was constructed of broken stone which was rolled and then sprayed with an asphalt compound to bind it together. Sand was sprinkled over it and worked into the surface by traffic. [29]

In May 1933, Thomas Vint mailed copies of the first Casa Grande "Master Plan" to Pinkley. The National Park Service field office in San Francisco had been working on the plan since mid-1932. It basically followed the ideas to which Pinkley and Vint had previously agreed. The plan called for considerably more construction than had been done to that date. To complete the monument housing needs, the plan proposed three more residences and a dormitory. It called for adding to the museum to finish it to Vint's original design of a square with an open center. The small, temporary pumphouse needed to be replaced. A maintenance area with three buildings was planned for the space just south of the residential quarters. During review, either Vint or Pinkley decided the proposed utility facility was too close to the residential area and, by using a pencil, drew a new location for two maintenance buildings farther to the south of the living quarters. Picnic area development included removing one ramada, extending the other existing ramada, adding four new ramadas, as well as building more fireplaces and tables (figure 23). The plan proposed that approximately two miles of old road and some old trails be covered to remove any trace of them. At the same time it called for the development of an informal footpath to follow a route from the Clan House to Compound C to Compound B to Compound E to Compound D and back to the parking lot by way of the south service road. Pinkley approved this Master Plan on September 2, 1933. He then developed a six-year program to accomplish the plan. At the same time the San Francisco field office issued a new Master Plan each year through 1941. Each new plan reflected the changes from the previous year (figures 24). Pinkley accomplished only part of what he wanted. By 1941 the Master Plan added proposals to change the design of the museum addition (figure 25). The plan also specified the need for digging a new well, obtaining natural gas by piping it into the monument, constructing an eight-stall garage, burying the electric line, building a brick incinerator, moving the east boundary fence inward to allow the state to construct better drainage along Highway 87, revegetating the area after the fence was set back, and establishing three interpretive trails to view various ruins instead of one long trail. [30]

1. Depression Era Programs

By fiscal year 1934 depression relief money began to be added to the Casa Grande budget, although by this point a large part of the construction program had taken place. Starting in September 1933, Public Works Administration (PWA) funds were used to replace the 3/4-inch water line with new 1-1/2-inch pipe, including hose valves, so that any building could be reached with a fifty-foot hose. The National Reemployment Service furnished local men to do the work. This same workforce installed a new hydrant at the picnic grounds. Two, 1,000 gallon water tanks were used to replace the two 525-gallon tanks installed in 1931. At the same time additional work was done on the picnic ground. More ramadas were added along with twenty new tables, seven fireplaces, and two swings and a teeter for children, while fifteen old tables were repainted. A Civil Works Administration (CWA) program provided men and money to bury the telephone line from the residential area to the monument boundary in December 1933. Civil Works Administration funds were used to purchase materials for the south and west boundary fences. Federal Emergency Relief Administration money paid the salary of six men in May 1934 to clear and grade that fence line in preparation for fence construction. The south fence was set back about thirty feet from the boundary to avoid silt dumped on the monument by the Indian Service from the Pima Lateral irrigation canal. Public Works Administration funds were also used to build one more residence. This final dwelling to be erected on the monument was begun in April 1934 and completed by July. At the same time the old quarters that Pinkley had built in Compound A in 1910 was repaired. It had stood empty from the time that Pinkley had vacated it in early 1932. [31]

Construction activity ceased for two years until 1936. In August of that year the Indian Service connected the monument to its power line. The line entered the monument from the south on poles until it reached an area several hundred feet south of the residential compound where, after leaving a transformer station, it connected to buildings by underground cable. By the end of 1936, the PWA supplied the money and manpower to construct a new sewer system. Work on that system began on December 19. It consisted of a new reinforced-concrete septic tank from which ran a three-inch concrete asbestos pipe for 1,600 feet southeast of the residential area. That pipe connected to a sixteen-nozzle sprinkler system which sprayed the effluent on the ground. The old cesspool was covered with concrete and became an overflow pit for the new system. [32]

In April 1937 Pinkley's old residence in Compound A was remodeled into an office for the Southwestern Monuments headquarters educational staff and quarters for two naturalists. When these men moved into the building in May 1937, they installed a homemade evaporative cooler. It was the first such cooling device to be used at the monument. The effectiveness of this "swamp cooler" resulted in a decision by Pinkley to install them in the other buildings. [33]

|

|

Figure 23: 1932 Master Plan map. (click on the above image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

|

Figure 24: 1935 Master Plan map. (click on the above image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

|

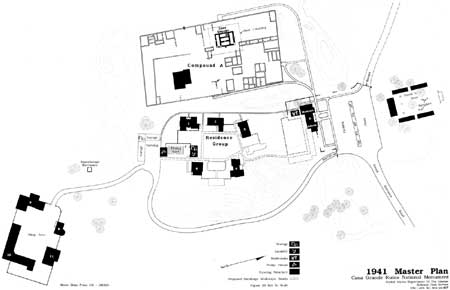

Figure 25: 1941 Master Plan map. (click on the above image for an enlargement in a new window) |

2. The Civilian Conservation Corps at Casa Grande

Although a great deal of construction had occurred at Casa Grande during the 1930s, by 1937 Pinkley still did not have a maintenance and storage facility. For this last large building project of the 1930s, Pinkley obtained the services of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). On November 16, 1937, a carpenter crew of twenty-four men and a foreman arrived at Casa Grande from the Chiricahua National Monument Civilian Conservation Corps Camp CNM-2-A to establish a fifty-man spike camp. Between that date and December 4, they built a barracks, mess-hall, washroom, storeroom, and a recreational hall in an area just southeast of the current maintenance facilities. The carpenter crew then departed for the main camp and was replaced by another group of CCC men who gave the finishing touches to their camp and then began preparation to construct the maintenance facility in an area south of the residential section (figure 25). [34]

Not all of the Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees worked in construction. During the time the camp was located at Casa Grande, two to four men were assigned each month to guide visitors through the ruins. Another one to two men were used as mimeograph operators and sometimes as clerk-typists in the Southwestern Monuments headquarters.

Since the architectural style for the new maintenance buildings copied the existing modified Pueblo style, these projects took thousands of adobe bricks. On December 14, 1937, the CCC crew began to prepare an adobe-making area and six days later produced their first adobe. Foundation excavation began at the same time for the first structure — a shop which became known as building 11. The CCC devoted its sole attention to this building until they began excavation work for a foundation for a warehouse on February 24, 1938 (Building 9). By the end of June 1938 these two structures had reached the point that only interior work remained to be done. At that time attention shifted to the erection of an oil house (Building 8). From the time excavation work began on the foundation, the CCC concentrated on the oil house so that by November 1938 it was nearly completed. In September a wash rack was built on the south side of the oil house and a gas tank and pump were installed in front. As a minor project in November 1938, the men erected protective walls around the electric transformer. In December the men devoted their attention to buildings 9 and 11. As a consequence the shop, warehouse, and oil house were finished in early January 1939. In June the shop and oil house doors and windows were painted "apple green." [35]

Sporadic work on an equipment shed (Building 10) began in October 1938. With the completion of the other three maintenance buildings the following January, the shed occupied nearly all of the men's time with the result that it was completed in March 1939. As soon as it was finished, an addition was begun to the east which would make the building into an L-shaped structure. When completed in November 1939, the addition, or section B as it was called, contained three bays of which one was oversized. [36]

In March 1939, at the same time the extension was being made to the equipment shed, a wing was built onto the warehouse on its south side. Thus this structure also acquired an L-shaped configuration. The original section contained a watchman's office and quarters as well as a storage area, but the addition had only storage space. It was completed in August 1939. [37]

During May 1939 the CCC men constructed an adobe, modified Pueblo style checking station at the entrance to the monument. Pinkley had been told to begin to charge a 25 cents admission fee starting May 1939 to each individual entering the monument. As a result, the checking station was erected to provide a building from which monument personnel could collect the charge. This practice had two effects. It angered 38.9 percent of the people who attempted to enter the monument with the result that they refused to pay and left. With CCC help to collect the entrance fee, there was no problem, but, when the CCC left in February 1940, the situation changed. At that time, there was an insufficient number of employees to handle the entrance station and museum, as well as conduct guided tours. As a result, on February 23, 1940, permission was granted to end the entrance fee. Only a 25 cents charge was collected at the museum from those taking a guided tour. Consequently, the checking station was dismantled. [38]

Beginning at the end of October 1939, work started on a one-room addition to the south side of the shop building. It was designed for use as a blacksmith shop. Work proceeded quickly, and it was completed in January 1940. [39]

From mid-1938 until December 1939, the CCC men periodically occupied their time constructing 417 lineal feet of adobe wall around the maintenance compound. A gateway with posts was completed in the northeast corner of the wall in August 1938 and gates were hung soon thereafter. In sections, such as that between the oil house and the shop, the compound wall was tied into the back wall of the buildings. [40]

The Casa Grande Civilian Conservation Corps spike camp was abandoned in February 1940 and the men returned to the main Chiricahua camp. On March 8, 1943, a group from the United States Army Corps of Engineers came to the monument and demolished the buildings. Salvageable material was hauled away in twenty-five trucks on March 10 and 11, 1943. [41]

3. After the Civilian Conservation Corps

The early 1940s at Casa Grande saw only minor changes mostly because the Second World War severely reduced funding and visitation. In 1940 the tool and implement storage shed (Building 15) was no longer needed for that purpose, so it was converted into a laundry and storage area for monument employees. In that same year, the superintendent's residence received a 140-square-foot addition and a screened porch was added to the west side of the custodian's house in place of a brush ramada. On December 16, 1940, construction began on a small room attached to the administration building. It was designed for a private office for Hugh M. Miller, who became superintendent of the Southwestern Monuments in February with the death of Frank "Boss" Pinkley. In April 1941, ninety percent of the east fence was set back ten feet to provide a wider right-of-way for drainage along the state highway. A decision was then made to replace the entrance gates and sign. In November 1941 demolition began on Pinkley's old house located in Compound A. By March of the following year it had been removed. [42]

Only a few changes occurred at Casa Grande through the remainder of the 1940s and the 1950s. In October 1942 the headquarters of the Southwestern Monuments was transferred to the regional office in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Consequently, several of the residential buildings were vacant. When a prisoner-of-war camp opened near Florence late in 1942, two of the quarters (Buildings 1 and 4) at Casa Grande were rented to army personnel from that camp. One of the quarters (Building 1) was occupied until May 1946 when the POW camp closed. On November 6, 1948, greater recognition was given to the individuals responsible for the national monuments when the title of custodian was replaced by superintendent. The skyline over the residential area changed at the end of April 1953 when Superintendent A. T. Bicknell was given permission to install a television antenna that extended twenty feet above the roofs. In 1956 the former campground was converted to form part of the picnic area. No one used the campground anymore as visitors preferred motels to camping. At the same time the Park Service encouraged surrounding communities and the state highway department to develop facilities to attract picnickers, while the number of tables at Casa Grande were reduced from fifty to ten. [43]

Water continued to be a problem in the 1940s and early 1950s. Farmers surrounding the monument had begun to drill irrigation wells in such numbers that the water table started to drop rapidly. By February 1942 water was being drawn from the monument well at a depth of eighty-eight feet. In 1945 the water dropped to the 102-foot level which was below the end of the suction pipe. At that time, the local Indian Service personnel loaned the monument equipment by which the pipe could be lowered another twenty-three feet into the well. In early 1948 the water level in the well had fallen to 140 feet as farmers had begun to pump from a number of new irrigation wells. In June it dropped another ten feet. By August 1949 irrigation pumping operations could temporarily drop the water table an additional thirty to thirty-five feet. For a time in December 1950 the water table slipped below the bottom of the well (186 feet). Over the next four months it returned to the 163-foot level. It was obvious that either the well had to be dug deeper or, as it was hoped, the monument could be connected with the Coolidge water. system. In December 1951 an announcement was made for bids to connect Casa Grande with the Arizona Water Company which also served the city of Coolidge. The job was completed none too soon on July 26, 1952. By June 1956 the area water table was reported to have dipped to 300 feet. [44]

At times the national monument could be a dangerous place to work or visit. In January 1951, while touring the ruins with his parents, a five-year-old boy was struck in the head by a stray bullet and killed. Several Coolidge youths caused the death when they randomly fired their rifles while walking along the canal outside of the monument boundary. In late December 1955, more shots were fired onto the monument by boys who were shooting the rifles they had gotten for Christmas. No injuries occurred on this occasion. Another tragedy happened on November 30, 1974, when Seasonal Ranger Gregory Colin Wayt was struck and killed by a bullet fired from outside the monument. A visitor was hit in the left leg by another bullet. Once more a Coolidge boy was found to be responsible. [45]

4. MISSION 66

For more than a decade from America's entry into World War II in 1941 to the mid-1950s, the National Park Service spent very little money for new buildings or to repair existing structures. The growing number of visitors during that time greatly crowded the existing facilities. At the same time buildings slowly deteriorated. As a result, the National Park Service director, Conrad Wirth, developed a program to build better visitor facilities as well as repair some existing structures. Because he hoped to achieve his plan by 1966 to coincide with the National Park Service fiftieth anniversary, it became known as MISSION 66. National Park and Monument superintendents were asked to submit a prospectus in which their needs were presented.

At Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Superintendent A. T. Bicknell wrote a MISSION 66 Prospectus and sent it to John M. Davis, the General Superintendent of the Southwestern Monuments, on July 14, 1955. Bicknell did not request any new development because he thought everything at the monument was adequate to meet employee and visitor needs. Davis did not agree with Bicknell's assessment. He thought that the long-proposed museum addition was necessary whereby the building would be enlarged to form a hollow square. The open center could be planted with native vegetation, Davis felt. When Hugh M. Miller, the Region Three director, received the Casa Grande prospectus, he made stronger comments. Miller wanted the museum/administration building removed and a new visitor center and parking area built closer to the entrance. He considered the employee housing to be an eyesore and wanted it, along with the picnic area, eliminated. Finally, Miller wanted the Great House roof replaced by a transparent air-conditioned cover over the entire ruin. [46]

Consequently, John Davis revised the prospectus to reflect some of Miller's comments. In this November 1955 version, Davis wrote that the employee housing would be removed and employees encouraged to live in Coolidge. The pumphouse would be torn down as well. Davis also added that despite the roof protection over the Great House, the upper area of that building had continued to crumble and the windward side suffered from blown sand. As a result, he requested that it be enclosed with steel reinforced plastic or glass. When it came to the museum/administration building Davis did not follow Miller's desire. Again Davis asked that the existing structure be expanded along with the parking area. Although there was some feeling in the Southwest regional office that the revised prospectus should follow Miller's comments exactly, the regional director approved it and sent it to Washington, D.C. for the National Park Service director's approval. Director Wirth reviewed the prospectus and approved it in January 1956 with two exceptions. He disapproved of a museum addition. Instead, he thought that the existing museum could be expanded by removing some of the administrative offices. Wirth felt that one of the employee residences should be kept for office space. [47]

In light of Wirth's statements, a revised version of the MISSION 66 Prospectus was circulated on April 19, 1956. It proved not to be the final product. Superintendent Bicknell was asked to change it one more time in May 1957. On this occasion, the decision to remove four of the five employee quarters was changed to retain two of the buildings. The prospectus received final approval on July 30, 1957. With that acceptance, the Master Plan, which had received some updating in 1952, was rewritten to conform with the MISSION 66 Prospectus. It was approved in 1961 and has not been revised since that date. [48]

Regional Director Miller's desire to have the so-called unsightly and ineffective roof over the Great House replaced with a complete covering resulted in exploring ways to have a more effective ruin shelter. Consequently, the famous architect R. Buckminster Fuller was invited to Casa Grande to discuss the possibility of building a plastic dome over the Great House. After his March 1956 visit, Fuller concluded that he could design a geodesic dome for the ruin and promised to build a model. When Fuller completed his model, it was sent to Washington, D.C. for inspection. The Chief of Interpretation, Ronald Lee, reported that he and the Chief Archeologist John Corbett as well as Mr. Vint had looked at the model and concluded "that the dome did not appear particularly desirable at Casa Grande." Lee gave four reasons for this view: 1) the dome would require expensive air-conditioning; 2) it would have more effect on the ruin profile than the existing shelter; 3) wind-carried sand could sandblast the plastic parts; and 4) a dome would cost more than modifying the current structure. Fuller returned to Casa Grande and explained that holes in the dome's base and top would permit a natural air flow so that no air-conditioning would be necessary. In addition modern plastics could be made to withstand the sandblast effect. Despite this assurance, Regional Archeologist Dale King thought the cost would be too great. Although the provision for a new ruin covering remained in the MISSION 66 Prospectus when it was given final approval in 1957, no attempt was made to carry out such a scheme after that date. [49]

The MISSION 66 Prospectus served as an imperfect planning tool. Although some of its provisions were carried out, in general many sections were ignored and projects not considered in the prospectus were approved. Instead of removing the pumphouse, it was converted to a storage facility in 1960. Later, in 1989, Superintendent Donald Spencer had the interior remodeled so it could be used for the monument library. In 1963 the laundry and storage building was converted to a three-stall garage. Late in that same year construction began on the museum/administration building addition despite the fact that it had been disapproved in the MISSION 66 Prospectus. When it was completed in 1964, the restroom building to its rear had been incorporated into the structure and an L-shaped wing had been added to achieve the hollow-square building. Restrooms were relocated into the front part of the structure with entrances off the new, covered porch which ran the length of the building's north side. This expansion provided more than double the previous area for display space. Native plants were placed in the open hollow center. The size of the public parking lot was increased as well to allow for sixty-six cars. Two of the five employee residences (the former 1925 museum and the 1929 ranger's quarters) were removed in 1965-66 along with the adobe wall which enclosed the quarters. Instead of destroying the 1931 Southwestern Monument Superintendent's house (building 1), as intended in the Mission 66 Prospectus, this building was given a major rehabilitation in 1965 including adding a new room in place of the west porch. It ultimately came to serve as a seasonal dormitory. Between July 19 and August 25, 1965, a final MISSION 66 project resulted in the reconstruction of the water distribution system. An 8-inch asbestos cement water main was connected to the Arizona Water Company supply, and secondary lines were installed from it to the buildings, picnic area, and three separate bubbler-type irrigation systems. In addition four fire hydrants with hose houses and hose were connected to the system. [50]

5. Casa Grande Ruins in the Nuclear Age

At the height of the cold war, as home owners were building bomb shelters in their basements, the National Park Service leadership decided to develop its own plan for an emergency response to a nuclear attack. On November 21, 1962, the Region Three director sent a memorandum to Aubrey Houston, the Casa Grande superintendent, in which he requested that a three-member Emergency Operations Committee be established to deal with civil defense emergencies, especially a nuclear attack. In the following year, Houston was asked to develop a handbook to be used for emergency operations as well as employee and visitor protection. The handbook author recognized that a nuclear attack on either Phoenix or Tucson could cause heavy fall-out at the Casa Grande Ruins. Since there were no fall-out shelters in the county, the civil defense plan was survival in place at least for some of the monument employees. All monument services would be reduced to protection by an emergency force of two individuals — the superintendent and a maintenance man. Visitors, the plan read, would be evacuated. It did not state to where they would be evacuated. Presumably, it would be to the monument entrance where they would be told to seek their own protection. In the meantime, at the end of the emergency, Casa Grande Ruins employees were to go to the nearest post office and obtain an Emergency Registration Card (SF-45). After they had filled it out, they were instructed to send the form to the Civil Service Commission in Washington, D.C. Then they were to await a call for Civil Defense duty. No recognition was given to the fact that a nuclear attack would undoubtedly have disrupted postal service and have destroyed the Civil Service Commission office in Washington, D.C. [51]

6. After MISSION 66

MISSION 66 proved to be the last major construction program to affect Casa Grande Ruins. Because of its small area, the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument superintendent has always had difficulties competing for funds. No relief was gained even after the 1971 reorganization when the monument was shifted from the Southwest Region to the Western Region. After 1966, maintenance for the existing facilities became the norm although some minor construction activity did take place. More tables were added to the picnic area in 1976. Energy saving measures took place in that year as well when the exposed glass in the visitor center was replaced by tinted safety glass to reflect the sunlight. Picnic area improvements again were made in 1977. A concrete slab was poured and a ramada built over it to accommodate more picnic tables. The water line was also extended to provide a tap near this new ramada. In February 1983 Casa Grande Ruins was annexed to the city of Coolidge. This meant that the monument fell under that city's fire, emergency medical, and law enforcement services. At the same time Coolidge began to collect the monument's garbage thus relieving monument personnel of the job of hauling it to a dump site. Because of this new relationship, the monument sewer system was tied into the Coolidge system on March 16, 1990. A sewage lift station was placed between the residential and maintenance areas. Superintendent Donald L. Spencer aided the interpretive program with the construction of a ramada-covered seating area in 1988 where visitors could sit in the shade to hear ranger talks. Two years later a steel platform was built so visitors could view the prehistoric ballcourt. [52]

From 1978-82, Superintendent Sam R. Henderson took part in the Youth Conservation Corps (YCC) program. Between two and four young people worked at the monument during the summer to help with stabilization and maintenance projects. Henderson dropped the program in 1983, but Superintendent Spencer reapplied for YCC aid in 1986. He has since employed an average of three YCC youths per summer who help with the preservation/stabilization of Compound A, maintain .46-mile of trail, repair and dean boundary fence, and repair and maintain picnic tables. [53]

In the latter half of the 1980s Superintendent Spencer began two cooperative ventures with the surrounding community. In 1986 when Ranger Richard Howard retired, he removed his art collection from the visitor center walls where it had hung. Faced with blank wall space, Spencer decided to hold an annual art fair for local artists. After discussing the idea with several area residents, he called a meeting on September 25, 1986 at which a Casa Grande Ruins Art Council was established. This council consisted of six members — two people from the national monument and four individuals from Coolidge. A decision was made that only Pinal County artists were eligible to compete for prizes at the fair. The winners could display their art in the visitor center for a year until the next art fair. The Coolidge Chamber of Commerce consented to join as sponsors. In 1990 the Pueblo de Los Suenos Art Association of Coolidge also joined as sponsors of this successful fair. Another successful venture occurred in 1989 when a cooperative agreement was concluded between the monument and the city of Coolidge to develop an interpretive rest stop in an area opposite the monument's northeast corner. When it was constructed in 1990, the monument superintendent supplied three wayside exhibits to display in the structure. [54]

7. Special Use Permits

Starting in 1927 the National Park Service leadership began to approve special use permits for Casa Grande. These permits were granted to various organizations basically to install or maintain such things as roads, electric lines, and a canal on the edge of monument land.

In the latter part of the 1920s, the Arizona State Highway Department constructed an improved road between Tucson and Phoenix. This Highway 87 passed along the east boundary of the monument. The state asked to be granted a special use permit for an eighty-foot-wide right-of-way through the monument's northeast corner to allow a curve to be built in the road (see figure 21). Arno Cammerer, the acting National Park Service director, granted the state this special use permit. It was issued on a year-to-year basis beginning on January 1, 1927, with a provision for an automatic twenty-year renewal. At the time, however, the state did not construct a curve in the highway. It developed a T intersection with Highway 287 instead and allowed the permit to expire in 1947. In the 1930s the Arizona Highway Department asked to be allowed to build a roadside park on monument land at the outer side of the proposed curve, but the Park Service opposed such a park for safety reasons. The National Park Service leadership did not wish to lose control of that narrow strip of land because it offered a means to restrict commercial development. Failing to achieve its roadside park, the state asked that the boundary fence be set back ten feet in that area supposedly to make it easier to landscape the intersection. Superintendent Bicknell granted the request. The state highway department, however, stripped the vegetation from the ten—foot—wide area and opened a barrow pit. [55]

Since the Arizona Highway Department had received a special use permit from the National Park Service, the San Carlos Irrigation Project could not be denied when its project engineer made a request for a permit in 1929. As a counterpart to the Indian Service irrigation project, the San Carlos project brought water to white farmers. In January 1929, the San Carlos project engineer contacted Pinkley and told him that in order to bring water to the section of land just north of the monument, a lateral canal would have to be constructed through the northeast corner of the monument parallel to the state highway right-of-way. Pinkley had no objection since a surface examination of the area indicated to him that a canal in that location would not damage any ruins, but he felt that the Park Service had no authority to grant such a special use permit for the proposed ditch. A. E. Demaray, acting National Park Service associate director, confirmed Pinkley's view. He indicated that the Washington office would take Pinkley's suggestion and seek legislation for a special use right-of-way permit. Senate Bill 4085 was introduced on April 2, 1930 to grant a right-of-way not to exceed fifty feet on each side of the canal for the San Carlos project. It passed and became Public Law No. 350 on June 13, 1930. [56]

Probably the most unnecessary special use permit was granted to Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph Company on March 5, 1942. This five-year permit was given on December 31, 1941 for the installation of a pay telephone in the Casa Grande headquarters office. Mountain States removed the telephone in 1947 and the permit was cancelled. [57]

As mentioned earlier in this report, a special use permit was issued to the United States Army between November 1942 and May 1946 for the rental of quarters 1 and 4 to house army personnel attached to the Florence Internment Camp. [58]

A potential request for a special use permit for a farm road right-of-way along the monument's west boundary developed in March 1943. The men who farmed to the west of the monument thought that such a road would save them from having to go around the monument to reach their land. The Pinal County engineer decided to wait until the end of the war before building a road. The need for a road was periodically mentioned until late 1951, but nothing came of it. [59]

The subject of the construction of a highway curve across the northeast corner of the monument came up once more in 1960 when a state highway survey party conducted a survey at that location. Casa Grande Superintendent Aubrey Houston wrote to the state highway department to ask for plans and proposals. The state engineer did not reply until August 25, 1961, and then he sent the plans to Emil Haury who headed the Arizona State Museum. Houston made another request to the highway department with the result that he received the plans. In the meantime Howard Shelp, the Arizona Highway Department right-of-way engineer, wrote to the Region Three director to request that the state receive a special use permit for the triangular piece of land in the monument's northeast corner along with a thirty-five-foot right-of-way on both the north and east boundaries. Regional Director Thomas Allen denied the state the thirty-five-foot right-of-way, but wrote that he would grant a renewable special use permit for the triangular piece of land. Dissatisfied with Allen's reply, William Willey, the Arizona state highway engineer, contacted Conrad Wirth, the National Park Service director, and insisted that the state needed the thirty-five-foot right-of-way for safety purposes. He assured Wirth that the state would only move the fence back thirty-five feet and not even disturb the natural growth. Wirth recalled the barrow pit incident in 1936 when the Park Service moved the northeast corner boundary fence back ten feet at the state's request. In the end a twenty-year special use permit (CAGR-1-62) was granted for the period January 1, 1962 to December 31, 1981 for the triangular piece of ground in the monument's northeast corner. In the summer of 1962 the state highway department constructed its curve through the corner, widened Highway 87, and included an island at the approach to the monument entrance. Workmen also set the east boundary fence back to accommodate the widened road. In October of that year the state constructed a new entrance into the monument. [60]

The state never used the entire triangular piece of ground in the monument's northeast corner. About one and a half years before the state highway special use permit expired, Casa Grande Superintendent Sam Henderson wrote to Howard Chapman, the Western Regional Director, to express his opinion that the Park Service should renew the state highway permit only as a right of-way for the road itself and not for the entire piece of land. Chapman agreed. Consequently, a three-year permit was negotiated in 1980 with only the roadway included in the right-of-way (CAGR-1-80). It was renewed for three years beginning January 1, 1984, but plans were already underway to eliminate the curve and return to the T intersection for safety purposes. The Arizona Department of Transportation completed the curve removal in December 1984. The area was fertilized and seeded. As a result, a new special use permit (ADOT F-005-1-702) was negotiated with the state for a short piece of land on the north side of the northeast corner for a right-turn lane. The permit expired in 1988 and is in the process of renewal. [61]

Two electrical lines run along the monument's eastern boundary. One is an overhead line owned by the Arizona Public Service and one is an underground line owned by the Electric District No. 2. The latter company is a publicly owned Rural Electric concern. On November 1, 1970, the Arizona Public Service received a twenty-year special use permit for an overhead transmission line within the Arizona Highway Department special use permit area. That company paid $10 per year for the permit. When it expired on October 31, 1989, the permit was renewed for one year and then switched to a ten-year right-of-way grant in 1990 (WR-CAGR-90-1). The assessment of a yearly fee under this new policy took into account land appraisal and administrative costs. As a result, the Arizona Public Service annual payment rose to $120. The Electric District No. 2 received a special use permit for an underground transmission line on November 1, 1970. Its permit expired on December 31, 1986, and was not immediately renewed. With the District's consent, Superintendent Spencer renewed the permit in 1989 for a five-year period starting on January 1, 1987. When it expired on December 31, 1991, the permit was not renewed because, under Title 36 CFR, the District does not need a special use permit since it was developed as a Rural Electrification Administration project. [62]

The final special use permit (WRO CAGR 5100 001) was granted to the city of Coolidge in 1983 for a nineteen-foot four-inch-by-eleven-foot two-inch area along the eastern boundary to erect and maintain a sign which read "Coolidge." A second renewal period ended December 31, 1991. A new permit is currently under review.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

cagr/adhi/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2002