|

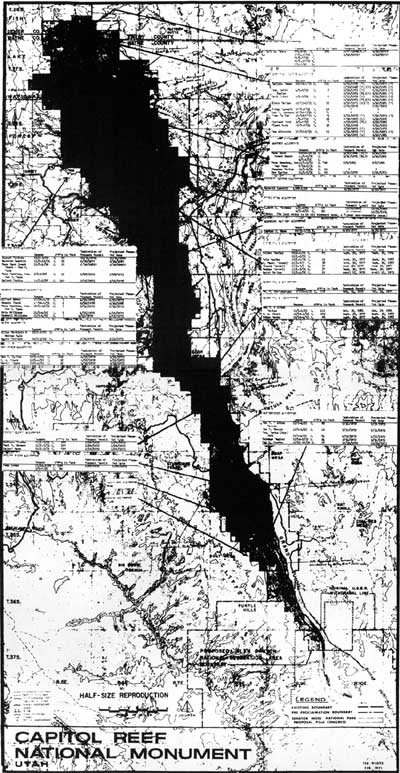

Capitol Reef

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 12:

GRAZING AND CAPITOL REEF NATIONAL PARK: A HISTORIC STUDY

Livestock grazing has been the most dominant and frustrating resource issue throughout Capitol Reef National Park's history. Because of the inherent conflicts between the local dependence on livestock and the limited-use, preservation philosophy of the National Park Service, grazing management has become a target issue for park managers, neighboring federal agencies, local communities, and single-use advocates.

For all the attention that grazing has received at Capitol Reef, there has yet to be commissioned a comprehensive history of livestock management and its impacts from the 19th century to the present. This history, nonetheless, proposes to answer some of the key questions about the nature, origin, and impacts of past grazing practices, and to describe National Park Service grazing management at Capitol Reef since the area's initial designation as a national monument.

Over the past 100 years, grazing became interwoven into the cultural and economic fabric of south-central Utah. During this time, the desert areas serving as traditional winter grazing range were heavily used and abused. When the National Park Service brought its limited-use philosophy to Capitol Reef in the late 1930s, conflict was inevitable. A lack of National Park Service attention and understanding, together with the agency's desire for quick solutions, exacerbated tensions. The steel of federal preservation management struck against the flint of local lifestyles has sparked ongoing grazing management conflicts at Capitol Reef National Park. Underlying reasons for these disputes must be analyzed and understood if the cycle of lingering conflict is to be broken so a new, more cooperative relationship among all parties can be created.

Chapter 12 is organized into seven sections. The first three sections establish the historical context by discussing how traditional livestock practices and federal grazing management evolved, first in Utah and elsewhere in the West, and then in the Waterpocket Fold country where Capitol Reef National Park is today. It was during this early period that many of the lands now within the national park were altered by a combination of overgrazing, drought, and economic fluctuations. This was also the time when the first regulation was attempted. Those early efforts at grazing management by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) and what later evolved into the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) have had a significant effect on the livestock industry and the local relationship with federal land management agencies.

The remaining four sections of Chapter 12 primarily focus on grazing management at Capitol Reef as it evolved from a small national monument to a sprawling national park. From the monument's establishment in 1937, through the controversial expansion and park designation in 1971, to the grazing phaseout debates, Capitol Reef managers struggled to find ways to protect lands already used by cattle. By the time a partial buyout of grazing permits was possible in the late 1980s, the previous conflicts had left scars that may persist for years.

The sources researched for this study came primarily from the National Park Service records, Record Group 79, found in Capitol Reef National Park's archives, superintendent's and resource management files, and at the National Archives, Rocky Mountain Region (now, Intermountain Region) in Denver. The records of the Bureau of Land Management, Record Group 49, were also examined in the National Archives, Denver, and at the Henry Mountain Resource Area files in Hanksville and Escalante, Utah. United States Forest Service records pertaining to areas adjacent to Capitol Reef were reviewed in Teasdale and Loa, Utah. The author thanks Keith Durfey for his help in examining these local BLM and USFS records.

Other primary documents came from the Utah State Historical Society archives and the special collections at Utah State University in Logan. Secondary sources and interviews provide additional insight and case examples. For more detailed background information such as a physical and historical description of the Capitol Reef area, see Volume I of this history. Copies of the legislation that established the monument and the park are provided in the appendix to Volume I.

The Evolution of Grazing in

Utah

Vegetation Before the Introduction of Domestic

Livestock

The focus of this study is the history of grazing management, but the actual impact of livestock on the park's natural resources is an important part of this history. Since ardent disagreement exists over the nature and severity of those resource impacts, it is important first to document vegetation changes within Capitol Reef National Park. The information provided here, however, is only a cursory look. For more detailed information, consult the appropriate management documents or specific grazing studies, which are listed in the bibliography at the end of this chapter.

While there have been a variety of historic and scientific accounts describing range conditions throughout Utah and the West, the isolation of Wayne and Garfield Counties prevented the recording of any comprehensive, scientific descriptions of vegetation before the 1930s. The descriptions and oral testimonies used to reconstruct earlier conditions, while illustrative, are not complete or systematic. Nevertheless, virtually every account, whether of Utah in general or the Waterpocket Fold region of Capitol Reef in particular, documents considerable vegetation change over the past 100 years. [1]

Utah's pre-settlement vegetation of the 4,000-to-7,000-foot range of elevation, which describes most of Capitol Reef, is described as follows:

Where the soils and the moisture supply was somewhat more favorable than ordinary, as along stream courses, the wheatgrasses and giant ryegrasses predominated. On drier sites sagebrush was proportionately more abundant but bore grasses between the sages in considerable amounts. Practically always the plant cover was dominantly a mixture of wheatgrass (or ryegrass) and sagebrush. [2]

The first known written description of Utah came from the journal of Friar Francisco Silvestre Velez de Escalante. Escalante, along with his fellow Franciscan, Francisco Atanasio Dominguez, circled around the Colorado Plateau in 1776. According to the journal, Utah Valley, near present-day Provo, contained bountiful "pasturage" that recently had burned. Escalante postulated that the area's native inhabitants were burning the grasses to prevent the friars' party, with its small herd of horses, from entering their lands. There are many accounts of American Indian people burning areas to maintain grasslands and otherwise manipulating natural resources well in advance of European settlement. [3]

Closer to Capitol Reef, Dr. Almon H. Thompson, who led John Wesley Powell's 1872 survey party through the Waterpocket Fold, commented that the abundant grasses on Boulder Mountain would someday be "a perfect paradise for the ranchers." [4] Expedition photographer Jack Hillers described the lush grasses and evidence of the first known cattle to graze in the vicinity of lower Pleasant Creek, perhaps within today's park boundaries:

This is the great hiding [place] of the Indians and many heads [of cattle] have found their way in here, all stolen from the Mormons, who never suspected for a moment that their friends the Utes would do the like, but thinking the Navajos the guilty party....They never dreamed that here the Indians feasted on broiled steak. Wild oats grow here the same as cultivated does anywhere else but not so heavy. [5]

Many of the first ranchers in southern Utah also recalled abundant, tall grass. Dixie National Forest Ranger William Hurst documented a 1935 conversation with Elias Hatch, one of the original ranchers in the area. Hatch recalled that, prior to livestock grazing on the eastern boundary of the forest, there was no sagebrush on nearby mountains, and forage consisted of "a heavy stand of pershia, snowberry, choice grasses, and weeds." [6]

Ranger Hurst noted that this description was accurate, supported by numerous other ranchers and by his own observations. Iinterviews corroborate the latest scientific evidence that range vegetation at Capitol Reef itself has changed during historic times.

For instance, the monument's first superintendent, Charles Kelly, recorded the observations of several older ranchers regarding the altered condition of the range. For instance, Kelly made one trip east of Hanksville in the company of an old cowhand, Court Stewart (whose name is inscribed in Capitol Gorge). Stewart looked at some rather bare ground and commented that, when he was a kid, that spot -- in fact, the whole desert -- "had grass on it that would rub the stirrups on a horse." [7]

Howard Blackburn, another early cattleman in Wayne County, also remembered the land before settlement. Blackburn told Kelly in 1946 about his first trip through what is now the heart of Capitol Reef National Park, in about 1881:

Sulphur Creek was then a tiny stream and had cut no canyon. Dirty Devil river was not more than a rod wide, its course thickly lined with willows. Most of the valley at Fruita was covered with a heavy growth of squaw bushes...The whole country, now an almost barren desert, was then heavy with tall grass. [8]

These accounts and a glance at the landscape today suggest that the vegetation covering the ranges of Capitol Reef has indeed substantially changed. The rugged, slickrock nature of the region has naturally limited grazing to the flatter, more open areas on the flanks surrounding the towering Waterpocket Fold. Grazed lands in the northern Cathedral Valley, southern Sandy Creek, Bitter Creek, and Halls Creek areas have always supported sparse vegetation. Yet, where bunch grasses and willows once dominated, cheatgrass, snakeweed, and tamarisk (all exotics or recent invaders) have become abundant. Large areas of grasses grow in some locations, while other areas have a few grass clumps only a couple of inches high. [9]

Based on analysis of preserved plant remains, Kenneth Cole's 1992 "Survey of Fossil Packrat Middens" offers a scientific reconstruction of vegetation cover prior to domestic livestock grazing. Cole cautions that his examination of packrat middens in the Hartnet Draw area in the northern end of the park and the Halls Creek drainage in the southern end of the park is not definitive. Nevertheless, he did establish that the vegetation collected by packrats for constructing their nests changed dramatically over the past 100 years. This change reflects the availability of plants in the local environment, where the rodents collect their materials. While Cole noted some cyclical change among the older varieties, such as certain grasses, pinyon, and winterfat, he observed:

None of the Presettlement middens are as different from the other Presettlement middens as are The Postsettlement middens. This suggests that recent changes in vegetation have been more severe than previous natural changes. In particular, at Hartnet Draw, where the time series of middens near one site yield the most reliable results, the vegetation changes occurring the last 100 years were more severe than any that had occurred during the prior 5400 years. This perspective of natural variation emphasizes the extreme severity of the recent vegetation changes. [10]

The fact that plant communities covering the arid plateau lands of southern Utah have changed is well substantiated. What now needs to be established is exactly how and when the changes occurred. If grazing caused today's comparatively depleted or altered rangeland, did these changes occur recently, historically, or cumulatively? What activities or policies caused the present landscape legacy? By placing grazing at Capitol Reef into its historical context and developing an understanding of when and how livestock management has evolved in the Waterpocket Fold country, present and future managers at Capitol Reef will be better equipped to make long-range policy decisions.

Early Utah Settlement and Grazing Patterns

The organized Mormon settlement of Utah, being different from settlement elsewhere in the American West, has left distinctive imprints on grazing history. The early communal herds, a spiritual belief in land stewardship, and significant control by Mormon Church officials resulted in a different tradition of grazing practices here. Yet, despite the best of intentions, the abundant ranges of Utah began to see almost immediate depletion This resulted from a lack of knowledge about arid environments, the influx of large, non-Mormon owned herds, and the rapid "Americanization" of Mormon grazing practices that ensued. [11]

The first arrivals to the foothills east of the Great Salt Lake in the late 1840s were from the Midwest, as were the stock they brought with them. Geographically isolated from new livestock breeds and the spread of customs dubbed the "Texas Invasion," Utah Mormons were able to establish their small herds in Utah before the huge, non-Mormon-owned herds arrived in the 1870s. [12]

The first outlying settlements north and south of Salt Lake City were founded near rivers emerging from the Wasatch and Oquirrh Mountains. Factors considered when deciding the suitability of a new settlement site included:

The presence of good soil, water enough for irrigation and for livestock, and timber supplies suitable for buildings, fences, fuel, and farm uses, and native forages for feed....The agricultural needs of the Mormon people founding Utah were (a) for areas of dependable land for cultivation, (b) irrigation water, (c) for nearby forage suitable as feed for horses, oxen, and farm livestock, and (d) sufficient range forage in the mountains, foothills, and semidesert valleys not immediately adjacent to the settlements to support range livestock. Permanent occupation depended in a large measure on the proper combination of all four of these resources. [13]

Since most of the meager lumber supply was used for house and barn construction, and because the settlements were springing up so quickly, the individual herds of cattle and sheep were gathered into common grounds for community herding. [14] Most Mormon families had at least a few head of cattle and sheep producing milk, cheese, wool, and meat. Customarily, groups of boys would assemble the numerous small herds each morning, and range the stock "on the nearby foothills in summer or flats in winter," bringing them back in the evening. [15] This kind of cooperative, town-based herding was distinctly different from the Hispanic and Texan traditions of expansive, open range ranching that were adopted elsewhere in the West throughout the 1860s and 1870s. Most distinctive of Mormon ranching practices, however, was the role of the church in governing the range and molding cultural attitudes towards the land.

Mormon Cultural Influences on Grazing

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints inarguably established among its members a certain regard toward the land. It also created a kind of Mormon perspective, which viewed "outsiders" as threatening to property rights and traditional lifestyles.

Like many rural residents of the American West, Mormon livestock owners viewed the land in terms of its economic potential. To the settlers of the arid and semi-arid landscapes that predominate throughout Southern Utah, the country was economically useless except for grazing. A strong spiritual confidence and the need to succeed and spread motivated church members to ranch on the forbidding open lands of Southern Utah -- and to make those lands produce. Modern resistance to preserving these public lands as wilderness or national parks is rooted in these same religious and economic motivations.

Many biblical references are interpreted by Mormons as ordaining their settlement of Utah. Perhaps the clearest is Isaiah 2:2: "And it shall come to pass in the last days, that the mountain of the Lord's house shall be established in the top of the mountains, and shall be exalted above the hills; and all nations shall flow unto it." [16]

Once settled in Utah, the Mormons looked at these new, unclaimed lands as their own, to be used in the wisest, most prudent manner that would benefit the individual and the church. The Mormon Doctrine and Covenants states:

[T]he fullness of the earth is yours, the beasts of the field and fowls of the air, and that which climbeth upon the trees and walketh upon the earth; Yea, and the herb, and the good things which come of the earth, whether for food or for raiment, or for houses, or for barns, or for orchards, or for gardens, or for vineyards; Yea, all things which come of the earth, in the season, thereof, are made for the benefit and the use of man, both to please the eye and to gladden the heart;...And it pleaseth God that he hath given all these things unto man; for unto this end were they made to be used, with judgment, not to excess, neither by exhortation. [Emphasis added.] [17]

This belief that the lands were for man to use as he saw fit was tempered by strict control by church officials, which in theory should have preserved the natural resources of Utah. Historian Dan Flores writes:

With their centralized leadership and their belief that the earth and all its products were the property of a divine entity, the Mormon brand of stewardship was at once less theoretical than Christian stewardship. Individual Mormons, for example, dedicated land and projects to the divinity. Additionally, the doctrine of continuing revelation was not only a boon for coping with a new environment, but endowed church decrees on natural resources with the power of supernatural sanction. The Mormons thus provide the closest American experience of the Judeo-Christian stewardship ethic, or the 'Abrahamic Land Concept,' in action on a pristine Frontier. [18]

Perhaps the most significant outlook toward the lands of Utah by the Mormons, however, is the attitude that the land was theirs and could not be taken from them. Again, this is a belief shared by many early settlers, as well as 20th century residents of the West. Yet the perception of persecution and identification as a chosen people would reinforce the Mormon belief that they should resist outsiders entering their lands and attempting to manage their livestock and lives. The Book of Mormon states:

Wherefore, this land is consecrated unto him whom he shall bring.... And behold it is wisdom that this land should be kept as yet from the knowledge of other nations; for behold, many nations would overrun the land, that there would be no place for an inheritance. Wherefore I, Lehi, have obtained a promise that inasmuch as those whom the Lord God shall bring out of the land of Jerusalem shall keep his commandments, they shall prosper upon the face of this land; and they shall be kept from all other nations, that they may possess this land unto themselves. And if it so be that they shall keep his commandments, they shall be blessed upon the face of this land; and there shall be none to molest them, nor to take away the land of their inheritance, and they shall dwell safely forever. [19]

Thus, not only is the land rightfully theirs, but so long as Mormons remain in good faith, the use of that land can not be taken from them. This notion is reiterated in the next passage, which warns that God would "bring other nations unto them, and he will give unto them power, and he will take away from them the lands of their possessions, and he will cause them to be scattered and smitten" if his people were not faithful. [20]

Utah, unlike the other Western states where grazing would begin to dominate in the last quarter of the 19th century, was established on firm religious grounds. Here, the earth itself was consecrated to the Mormon settlers as a chosen people, and promised to them for as long as they remained faithful and good stewards of the land. Such strong belief in the rights of Mormons to be the stewards of these chosen lands also helps explain why many Utah ranchers view all their traditional grazing lands, whether on federal lands or not, in terms of private property rights.

Despite the good intentions of the original Mormon settlers of Utah and the controlling influence of church officials, the lands grazed by the Mormons' cattle and sheep quickly began to deteriorate, even before the invasion of "other nations."

American Indians were noticing the decline in grass and wild animals as early as the 1850s, and overgrazing was noticed by the Mormons themselves a decade later. Apostle Orson Hyde of Sanpete County (30 miles north of Capitol Reef National Park) warned the General Conference of Saints in 1865 of a deteriorating range:

I find the longer we lie in these valleys that the range is becoming more and more destitute of grass; the grass is not only eaten up by the great amount of stock that feed upon it, but they tramp it out by the very roots; and where grass once grew luxuriantly, there is now nothing but the desert weed, and hardly a spear of grass is to be seen. [21]

The eastern and midwestern farming methods used by most early Mormons were not appropriate to the arid, Western landscape. Again, according to Flores:

Even before the rush of individualistic Gentiles into the territory, Utah's environment was showing signs of deterioration. In its efforts to provide for the growing numbers of converts by making 'the desert bloom like a rose,' the Mormons decidedly overstrained the fragile Wasatch environment. Accustomed to eastern conditions and lacking scientific knowledge of plant succession, or the relationship between water, vegetation, and slope, and forced increasingly both to provide for larger numbers and compete for resources with non-Mormons, the church could not develop a land ethic. [22]

The arrival of huge cattle and sheep herds during the 1870s and 1880s not only worsened the problem, but forever changed livestock management in Utah.

Large Herds and the "Americanization" of Utah

Grazing

Beginning sometime in the 1870s, large herds were pushed onto Utah's open range, where only a few small, cooperative herds grazed before. The move was slow in starting, again due to Utah's geographical barriers. There was an increase from 39,180 cattle, reported in the 1870 census, to 132,655 in the 1880 census. Yet, at the same time, neighboring ranges in Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana were supporting well over twice that many cattle, most driven north from Texas. [23]

The 1880s saw the real boom in livestock numbers as cattle jumped to 200,000 by 1885 and nearly 420,000 by the middle of the 1890s. Meanwhile, sheep were also being driven into Utah at an alarming rate:

From the modest beginnings of only a few head per farm, sheep increased so rapidly after 1875 that the ranges of Utah were supporting one million head by 1885; nearly two million in 1895; 2,600,000 in 1905. [24]

According to all available accounts, this dramatic increase in livestock at the end of the 19th century was due to arrival of several large outfits financed by eastern and English capital, and to local Mormons increasing their own herds to compete on lands that were previously theirs, alone.

The federal Works Progress Administration history of grazing in Utah, compiled during the late 1930s, blamed these invading herds for much of the damage to Utah's ranges:

[T]he system of handling livestock during the boom days was simply no system at all, first come - first served, during any season of the year....This country to all appearances was yearlong range in the eighties, and it would no doubt have continued to be such and supported many head of cattle had not the large eastern companies come in. There can be no doubt but that these companies came in to get all they could, utilize the virgin range and cash in on it. [25]

Yet throughout this era, the small Mormon ranchers with herds of only a few hundred cattle continued to be the dominant operators. The extremely large herds of cattle and sheep were owned by only a handful of powerful operators "who ruthlessly grabbed all they could, while they could -- and unloaded." [26]

The Works Progress Administration estimated that there were only four large companies with over 50,000 head of cattle each. The next class of owners, about 50 total, included those holding 1,000 to 5,000 head. The majority of livestock owners continued to be those owning only a few head "that were incidental to farming...in which case they were regarded as cattle men and not farmers." [27]

Both the WPA Grazing History and the respected historian Charles Peterson have blamed these large herds for the beginning of overgrazing. Utah ranchers, responding to outside competition, increased the size of their own herds and adopted herding practices common throughout the rest of the West. Historian Flores argues that non-Mormon pressure on Utah's resources caused Mormons to lose their "affection for egalitarianism." He explains:

When [Brigham] Young's death in 1877 removed the major advocate of the old order, Mormons in Utah began a process of Americanization....Although separation of church and state and abandonment of plural marriages were the most symbolic reforms required to 'bring the territory into conformity with national standards,' Americanization in process had meant a tacit recognition that resource use was a matter of competition rather than 'state' planning. [28]

In response to pressure, Mormons abandoned the old, church-encouraged stewardship and their small, cooperative herds in favor of larger, mobile flocks of sheep and cattle that could better compete for remaining ranges. The effect of this change was an "Americanization" of grazing in Utah and an even more rapid deterioration of the fragile, arid range.

The large outfits entering Utah during the 1880s included those of Preston Nutter, who ranged cattle west and north of the Colorado River; the Pittsburgh Company, which took over some of the small ranches around La Sal; and the Carlysles from England, who bought out ranches near the Blue Mountains. Closer to Capitol Reef, many of the larger ranches that had started up during the cattle boom days of the 1880s were developed by Mormons. The Scorups, from Salina, used a great deal of range east of the Waterpocket Fold. Another Utahn, Will Bowns, of Sanpete County, developed the Sandy Ranch a few miles south of Notom. Other ranches founded around the Henry Mountains around the turn of the century included John A. Burr's Granite Ranch, and the Starr, Fairview, and Trachyte ranches, some of which were Mormon-owned. [29]

Interviews conducted for the WPA grazing history give a clear picture of the competition between the large and small outfits. Niel Ray, of Moab, recalled:

These first settlers were not trying to become big cowmen, they only wanted enough cows to give them a good living, and they wanted to keep it that way and have the range like it was to pass on to their children and grandchildren. But even before 1900 the eastern companies started buying out the little fellows and after that they had big outfits, run by foremen, and hired riders from out of the community. These riders were tough hombres, many of them wanted by the law in Texas, Oklahoma and those places. [30]

Non-Mormon livestock companies pressured ranchers around Capitol Reef, too. Guy Pace, a long-time Wayne County rancher, describes the situation:

On the winter ranges [east and north of Fruita] we were getting operators from all over. Coming in from Colorado and everyplace. Just coming in. See, there was no controls at all...And people that had big herds of livestock [were] coming from all over, providing there was grass. It was a result of that, see, it depleted the ranges to beat hell. [31]

Regardless of whether range damage was caused by the large herds coming in or by the local, Mormon-owned herds, these large cattle and sheep companies left their mark on local culture, its oral traditions and, of course, the range. Southern Utah was particularly affected:

In this wonderland the large cow outfits like the Carlysle, Pittsburgh, and Elk Mountain existed for a decade and left history colored with long ropes, fast horses, smoking six guns, Robbers Roost, outlaw gangs, and blood. Texas cow punchers, Texas cattle, and Texas methods were introduced. The punchers grew in number; the cattle were rapidly bred away from the longhorn strain; and the old methods could not be used. [32]

There was also a general mixing of the wild Texas cattle culture with that of the more reserved Mormons. Charles Peterson wrote:

Young and full of life, cowboys invaded the Mormon towns socially. As a local folksong put it, they drank at Monticello's Blue Goose Saloon, traded with Mons's store (the town's only mercantile institution) and 'danced at night with the Mormon girls.' Occasionally there was gunplay....More important was the fact that a dozen or so outside cowboys married Mormon girls. Frequently these men stayed in the country where they became the relaxed channels through which Texas and Mormon customs evolved. [33]

This "Americanization" of grazing in Utah thus resulted in social, cultural, and economic changes that have lingered to the end of the 20th century. Perhaps the most significant of these changes was the adoption of the Texas style of ranching, which encouraged larger herds, running virtually wild, with few roundups or closely guarded water supplies. This altered the traditional Mormon pattern of small, cooperative herds, closely watched and often turned in toward town or the base ranch on a regular basis. Instead, sheep and cattle herds, in excess of natural carrying capacities, were moved to pasture earlier and earlier in the spring to claim what was left of the diminishing grasses. [34]

The federal Works Progress Administration study of grazing in Utah used interviews with hundreds of "stockmen, authorities and students of the range" to establish a maximum carrying capacity for Utah of 300,000 cattle and 2 million sheep. These levels were reached sometime in the 1890s. [35] Yet, figures showed that there were as many as 420,000 head of cattle in 1895 and a gradual increase to over 500,000 by the peak year of 1920. Meanwhile, sheep numbered 2 million in 1895, increased to 2.6 million 10 years later, and then fluctuated in number before reaching peaking at over 3 million head "crowding the arid, desert winter feeding grounds." [36]

There is ample testimony that the stiff competition between livestock herds destroyed range conditions and introduced new, invasive plant species by the turn of the century. According to information the WPA gained from the United States Forest Service:

The livestock industry in this section [of the intermountain region] reached its peak as far as numbers were concerned around the turn of the century. Practically every available foot of accessible range was being intensively used. It was: first there, first served....All this time the condition of the vegetation was forgotten. Feed for the current year was the by-word. There was a race to reach the feed. Stock were placed on the range too early and in too great numbers. Summer range was at a premium and the stock were often left on the range too late in the fall....This was no fault of any stockman and no criticism is due him for the conditions that prevailed. The range was there and was free to the man who got it. [37]

Glynn Bennion, who ranged cattle throughout central Utah, recounted:

Rush Valley was all a beautiful meadow of grass when we came here with stock in 1860; but in less than 15 years she was all et out, and we had move to Castle Valley...If you pass through the old livestock-growing communities of Utah you may think that those big old houses date back to the days of polygamy. Maybe so, but they also date back to that period in the life of every Western community when the grandfathers of the present tumble-down generation were making money hand over fist off the virgin ranges. The descendants aren't making any money now off the ranges their ancestors ruined. [38]

Bennion went on to discuss the changes in vegetation as a result of overgrazing:

A resurrected pioneer couldn't even recognize the present desert flora. It bears scarcely any relation to that of 1860. For as the pioneer flocks killed out the best forage types, other plants of less flavor and nutrition took the vacant place in the sun. Then the grazing herds lowered their standard of living and 'took' the poorer forms. Again the flora was changed to still worse types until by progressive deterioration we have the bitter, spiny, worthless kinds of today. [39]

At approximately the same time, the geologist Herbert C. Gregory documented deteriorating range conditions around the Kaiparowits Plateau, southwest of Capitol Reef:

In crossing the Kaiparowits in 1915 grass for horses was abundant along the Wahweap, Warm, and Last Chance Creeks, and the mesas and dun-colored areas east of Paria....In 1922 there was insufficient forage for pack trains at all places except in the sand dune areas of the Escalante Valley. In September, 1924, no grass or browse of any kind was found in the unfenced areas of Boulder Valley and about Canaan Peak. There is no doubt that the Escalante and Paria Valleys and the Kaiparowits Plateau have deteriorated as pasture lands during the last decade, and it seems unlikely that they can be restored to the state existing during the period 1875-1890. Some system of reservation seems most likely to bring improvement. [40]

From the beginning the Mormon livestock industry affected the range. Then, the invasion of large, out-of-state cattle companies and the infusion of large sheep herds stimulated the local small ranchers to raise their own herd limits to meet the rising competition. The public lands that could be used for grazing seemed unlimited when the Mormons first arrived. Yet, by the first decades of the 20th century, not only was all the possible range being used, but competitive herding practices were reducing the carrying capacity of grazed lands at an alarming rate. Significantly, however, while livestock management practices changed during the booming 1880s, the spiritual and communal nature of the Mormon residents would remain the same. So would their resistance to outside government officials determining the fate of their chosen lands.

Origins Of Federal Grazing Regulation, 1880 To

1936

After The Boom: Economic And Range

Deterioration

As was typical in the turn-of-the-century West, it was economics -- not the actual destruction of the landscape -- that eventually led to calls for change.

By the 1870s, the American economy was coasting toward tremendous expansion, and livestock speculation went along for the ride. The rapid advance in transportation by the railroads and growth in the eastern population helped fuel the cattle boom discussed above. In 1879, ordinary range stock sold at about $8 a head by the herd. Only two years later, the price was $12, and the scramble for more ranches and more land was fueled by speculators from around the world. [41]

At the same time, favorable weather patterns lulled many novice ranchers into a false sense of security. All this would change with the infamous winter of 1886-87. While it is unknown exactly what effect this winter had on southern Utah, hundreds of thousands of head of cattle and sheep throughout the American West were lost to starvation and sub-zero temperatures. When the winter was over, the industry was devastated:

Cattle that had been valued at from $30 to $35 on the range sold for $8 to $10, if they sold at all. The 'range rights' were found to be fictitious, and the free grass, if not gone, was going under fence now very rapidly. The holiday and fair-weather ranchman and remittance men suffered along with the real cattlemen. [42]

After this "big die-off," the overstocked, overgrazed lands were subjected to several years of abnormal drought. Most large, speculative cattle operations folded by the end of the decade, leaving the smaller and mid-sized cattle ranchers to fight over the remaining public lands. [43]

Early Public Land Policy

One of the most oft-debated aspects of Western history is the role of federal public land development policy in shaping, or failing to shape, the Western public domain. The most widespread interpretation is that the disposition of federal lands from the 1780s, through such legislation as pre-emption and homestead acts, was undertaken for political reasons having little bearing on practical reality. These laws, ill-suited to the West, pitted settler against rancher or rancher against rancher, with speculation, land wars, and overgrazing as the lasting legacy. [44] As land-use policy historian Phillip Foss observes:

This incalculable waste of resources and human life was not a consequence of the forces of nature: nor was it a consequence of the operation of economic forces through the market and the price system. It was basically and fundamentally a result of political decisions which ordered social forces in such a manner as to disturb the balance of nature. [45]

While the bloody range wars did not happen in Utah, thanks to its homogeneous and church-governed majority, ardent competition for mountain and desert ranges resulted in the destruction of vegetation. Even after the removal of many of the huge herds by 1900, the damage to the landscape was, literally, coming into Mormon homes as floods.

Throughout the rest of the 19th century and into much of the 20th, towns and cities have been inundated by flood waters no longer checked by deep-rooted grasses. Manti reported nine devastating floods between 1888 and 1909, and the years 1923 to 1930 saw a total of 16 Utah counties suffer from floods much larger than ever seen before. [46] Around the Capitol Reef area, these floods had a significant impact on settlement:

Depletion of the range up country and the ploughing of banks practically to the water's edge, increased volume of floods and the result was a severe lowering of the stream bed. By the turn of the century, Mormons along the Fremont below the reef found that much of their farm land had caved away to be washed downstream and that the river itself was dropping below the level of the headgates. The result was a contraction of the original frontier of settlement as people began to move away. [47]

The combination of these floods with the depleted range conditions, continued poor livestock prices, and uncontrolled use of the public domain finally forced Congress to begin looking at regulating the federal grazing lands.

The first comprehensive examination of Western land use problems was completed by John Wesley Powell in 1878. His Report on the Land of the Arid Region of the United States proposed a new system of large, self-regulated ranching units:

The grasses of the pasturage lands are scant, and the lands are of value only in large quantities.

The farm unit should not be less than 2,560 acres. The division of these lands should be controlled by topographic features in such manner as to give the greatest number of water fronts to the pasturage farms.

Residences of the pasturage farms should be grouped, in order to secure the benefits of local social organization, and cooperation in public improvements.

The pasturage lands will not usually be fenced, and hence herds must roam in common.

As the pasturage lands should have water fronts and irrigable tracts, and as the residences should be grouped, and as the lands cannot be economically fenced and must be kept in common, local communal regulations or cooperation is necessary. [48]

These suggestions for future grazing control were undoubtedly influenced by his years in Utah observing early Mormon cooperative practices. In essence, they later became the foundation for the Taylor Grazing Act in 1934. Between 1878 and 1934, however, there were few actual attempts to institute federal grazing management, except within the national forests.

The Forest Service Experiments With Grazing

Reform

In order to place this study of Capitol Reef National Park's grazing history in context, it is important to examine how other federal agencies in the area have managed their grazing lands, particularly those later included in the national park. The U.S. Forest Service became the first federal grazing manager.

The first forest reserves were set aside by President Benjamin Harrison in 1891, as authorized by what is known as the Creative Act passed that same year. Just what would be done with these resources was not established until the late 1890s.

In 1897, in a pattern often repeated in the years to come, Western livestock industry fears of over-regulation (brought on by President Cleveland's unexpected addition of 21 million acres of forest reserves) prompted Congress to restrict the Department of the Interior's authority to enforce land management. (The forest reserves were not transferred to the Department of Agriculture until 1905.) To ensure future appropriations, initial attempts to dramatically restrict sheep grazing were softened. Cattle were not seen as a threat to national forest resources until later. [49]

For example, early attempts to prohibit sheep in some reserves suffering from overgrazing were abandoned. Instead, a system of free permits would be used to regulate sheep numbers and period of use. However, because there was no way to enforce the permit system, sheep continued to roam the reserves as before. [50]

By 1902, Theodore Roosevelt was in office and his friend, Bureau of Forestry Director Gifford Pinchot, was a rising influence in grazing management. Pinchot realized that unregulated competition between various livestock ranchers was depleting timber and watersheds. He believed that any grazing policy must include some kind of regulation, rather than prohibition and "resting upon cooperation among the user interests themselves." [51]

The Department of the Interior, in a desperate attempt to rectify its previous attempts to manage the range, patterned its new grazing regulations after Pinchot's suggestions. A 1902 circular, issued by the department to help explain its new permit system, said that preference would be given to those who lived within or owned stock ranches adjacent to the forest reserve. Local woolgrowers' associations would recommend which ranchers received permits. This kind of self-regulated permit system favoring the local, established livestock operator, would dominate federal grazing management policy for the rest of the 20th century. [52]

When the forest reserves were transferred to Gifford Pinchot's Department of Agriculture in 1905, the management policies did not appreciably change. The concerns of the now national forests were to "break down the opposition and hostile attitude that sheep and cattle men held" and at the same time "discharge faithfully the responsibility of protecting and perpetuating the priceless natural resources." [53] The solution, according to the WPA Grazing History, was to establish "the first national forest advisory boards in Western range history, for the purpose of hearing by local forest officers the problems of allotment of range, numbers of stock to be grazed, adoption of special rules dealing with local conditions, etc." The history continues, "As soon as this provision was made, stock associations were formed on all the national forests. The stockmen welcomed these organizations and practically all the national forest permittees were represented on the advisory boards. Some of the original national forest livestock associations which were formed in Utah and Idaho are still in effect." [54]

These local advisory boards, made up of permittees elected by their peers, worked with the forest officials in granting permits, establishing allotments, periods of use, and carrying capacity for cattle and sheep. Information about local patterns and needs was the primary reason for the advisory boards. It was not their role to establish or enforce U.S. Forest Service policy. The advisory boards did, however, ensure the local ranchers' perceived right to graze as many head of livestock as possible. [55]

For example, in southern Utah:

The allowance for the Aquarius Forest [the western part of Dixie National Forest] for 1907 was 11,000 head of cattle and 55,000 head of sheep. Cattle season April 15 to November 15 and sheep season lambers May 12, others June 25 to October 20. All applications for cattle and sheep were approved. All sheep applications were approved except those which applied for more than 3,000 head. [56]

Livestock numbers were sustained on the already depleted range, according to Dixie Forest ranger, in an effort to protect "the principal resource of income in Southern Utah." The ranger believed that, had the USFS in 1910 abided by established carrying capacities at that time, the range in 1935 would have supported more livestock. [57]

U.S. Forest Service officials recognized that local economic and social conditions had to be considered when determining the uses of federal lands. From the outset of the forest reserves, it was obvious that range management would be successful only if the ranchers themselves were involved. Contributing to this philosophy was the fact that most if not all the forest rangers during this time were from the local communities. While the advisory boards helped legitimize grazing policy in the national forests, the result was an inability to close off the range to ensure resource recovery. In short, grazing management in the national forests necessitated compromises by the users and federal agencies, while the resources themselves were compromised. This situation would arise again with the implementation of the 1934 Taylor Grazing Act.

Economic Problems And Regulation Of The Pubic Domain:

1918-1934

Following the establishment of national forest grazing policies, members of Congress attempted to pass legislation that would create a similar permit system on the rest of the public domain. Resistance from the woolgrowers, jurisdictional disputes between the Departments of Interior and Agriculture, and the lingering belief that the remaining public lands needed to be partitioned by the traditional homestead method, prevented action. [58]

By the 1920s, little had been done to correct range abuses, and the climate for regulation had only worsened. Grazing fees in the national forests had been low since their inception in 1906. [59] By 1918, range conditions had apparently improved enough "to charge a rate which was more in line with the benefits derived." [60] After World War I, however, congressional committees searching for ways to pay the war debt fingered grazing fees as a promising means of raising revenue. While the forest service stalled for time by urging new studies, stockmen opposed to the escalating fees "took advantage of the controversy over grazing fees to make things as uncomfortable for the forest service as possible." [61]

Congressional subcommittees were dispatched out into the field to hold hearings, which turned out to be forums for those dissatisfied with forest service grazing management. These hearings raised the hopes of stockmen that fees would be lowered or even abolished, and awoke the conservation groups who rose in opposition to any change in U.S. Forest Service operations. Historian Foss writes:

The net effect of the investigation appears to have been a weakening of the position of the forest service and a postponement of much-needed regulation of grazing on the public domain. As a result of the forest service fee controversy Western stockmen were more distrustful than ever of federal regulation. The same fee controversy convinced eastern conservationists that the stockmen were out to loot the public domain and that no legislation should be enacted which would in any way accrue to their benefit. And the range continued to deteriorate. [62]

Conditions might have remained in this state for many more years if not for a post-war livestock recession that led directly into the Great Depression. A lot of the Western livestock industry's anxiety over increased grazing fees during the 1920s was due to the agricultural slump after the war. The lower demand for meat and wool caused prices to fall and forced livestock owners to sell at basement prices. It seemed to many ranchers that the worst of the crisis was over in 1930. Then the Depression hit, coupled with an extended drought throughout the West, and the livestock economy appeared doomed. Ranchers must have been disheartened to see their smaller herds forced to graze on range that should be improving but which, because of the drought, was actually deteriorating. [63]

Many ranchers have claimed that drought did more to damage the range than overgrazing. [64] Others, such as to Utah rancher Glynn Bennion, saw things differently:

If the range be considered the principal part of the grazer's capital stock, then we grazers have just about finished consuming our capital. We've got nothing much left to do business with. And all the time we've been kidding ourselves that we could eat our cake and have it. 'It's the drough[t],' we say when looking sourly out upon a depleted range. 'If we could only get the rainfall they used to have.' Let's quit kidding ourselves. [65]

The Works Project Administration's history of grazing in Utah found a depressing scenario for the state's livestock industry:

Ranchers and stockmen who were mortgaged were in many cases closed out, a good many turned their sheep, cattle or ranches over to the banks voluntarily; not however, until after they had been harassed beyond their endurance and could see no future ahead. Those who had kept their property unencumbered and now needed money and credit were unable to obtain it. The years from 1930 to 1934 were the darkest in the history of the livestock industry, and from the viewpoint of the men themselves, the darkest years in the history of local endeavor. Their resources were exhausted; there was nobody or no place to turn. They were finished and merely to watch their animals starve to death. [66]

In Utah and throughout the rest of the West, the stockmen were in such a weakened state that they no longer fought, and in many cases welcomed, federal grazing regulations for the remainder of the public domain.

The Taylor Grazing Act: Passage And

Implementation

By 1934, the economic and climatic devastation of the Depression years combined with the New Deal belief in federal assistance to make grazing reform inevitable. With many of the national livestock associations urging reform, and with Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace and Secretary of Interior Harold Ickes in strong favor of complete federal control of the remaining public domain, all that was left to decide was the exact wording of the enabling legislation. [67]

There was some reluctance among Western states to give up hope for some control of the lands, but the states had little budget or manpower to manage what lands they did control. Taking on marginal grazing lands would add to the burden. Utah Governor George Dern observed, "The States already own, in their school-land grants, millions of acres of this same kind of land, which they can neither sell nor lease, and which is yielding no income. Why should they want more of the precious heritage of desert?" [68]

In order to win the state-control advocates over to the Taylor Grazing Bill, Secretary Ickes promised to deliver Civilian Conservation Corps crews to help develop range improvements, such as fence, water holes, and stock driveways, in the more impoverished areas. He would do this, though, only if the range was under federal regulation. [69]

While the grazing reform bill sponsored by Congressman Edward T. Taylor (Colorado) was moving through the House with relative ease, Western senators, traditionally opposed to any federal regulation of land use, set about to block its path. The summer of 1934, however, saw the worst dust storms in the country's history, which weakened the last resistance to the Taylor bill. The Taylor Grazing Act was passed by the Senate on June 12, 1934, and signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 28, 1934. [70]

The reasons for supporting the Taylor Grazing Act are best summed up in the words of its sponsor:

I fought for the conservation of the public domain under Federal leadership because the citizens were unable to cope with the situation under existing trends and circumstances. The job was too big and interwoven for even the States to handle with satisfactory coordination. On the Western slope of Colorado and in nearby States I saw waste, competition, overuse, and abuse of valuable ranges and watersheds eating into the very heart of Western economy....The livestock industry, through circumstances beyond its control, was headed for self-strangulation. Moreover, the States and the counties were suffering by reduced property taxes and decreasing revenues. [71]

On November 26, 1934, President Roosevelt signed an executive order that withdrew from classification all previously unclaimed public lands in Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming. These lands, considered valuable chiefly for grazing, were originally supposed to comprise no more than 80 million acres. When Congress realized two years later that this did not go far enough, the amount of land subject to the grazing act was almost doubled to 142 million acres. Of this land, 95 percent would be in areas of the West that received less than 15 inches of annual rainfall. [72]

As stated in the legislation's preamble, the purpose of the Taylor Grazing Act was to "stop injury to the public grazing lands by preventing overgrazing and soil deterioration, to provide for their orderly use, improvement, and development, to stabilize the livestock industry, dependent upon the public range, and for other purposes." [73]

In order to accomplish these goals, the Secretary of the Interior was authorized to:

make rules and regulations...enter into such cooperative agreements, and do any and all things necessary to accomplish the purposes of this Act and to insure the objects of such grazing districts, namely to regulate their occupancy and use, the preserve the land and its resources from destruction or unnecessary injury, to provide for the orderly use, improvement, and development of the range. [74]

The secretary was given a great deal of flexibility in determining proper sale of some lands, leasing small parcels to owners of contiguous property, and exchanging lands with states or private interests in order to consolidate federal lands within each grazing district. [75]

Perhaps the most important components of the Taylor Grazing Act have been:

the Secretary of the Interior's authorization to determine and collect grazing fees;

the instructions to the secretary to provide "cooperation with local associations of stockmen, State land officials and official State agencies engaged in conservation...of wild life" [76]; and

the granting of preferential grazing privileges to "those within or near a district who are landowners engaged in the livestock business." [77]

The first provision gave the secretary the power to charge fees and enforce regulations, the second attempted to comfort Western livestock owners by providing for what Congressman Taylor called "home rule on the range," and the third ensured that local, traditional use by established property owners would be guaranteed. [78]

In a further effort to appease state governments, the 1934 act stipulated that 50 percent of grazing fees would be returned to the states, with the remainder to be split between range use and direct contributions to the U.S. Treasury. In 1947, the state cut was reduced to 12.5 percent. [79]

No regulations or fees were established during the first year of the Taylor Grazing Act. This was intended to permit a slow transition that would accommodate the Western stockman, and also to provide an information-gathering period during which many of the lasting policy interpretations could be made. [80]

From December 1934 to January 1935, the first director of grazing, Farrington R. Carpenter (a rancher and lawyer from Congressman Taylor's district), met with stockmen in 10 different states. Stockmen were then elected to a state committee that was charged with recommending grazing district boundaries. The most difficult problem Carpenter faced was trying to acquire as much detailed information in the shortest time possible about range conditions and carrying capacity for each individual district. [81]

The grazing director's solution was to establish district advisory boards, elected by the permittees themselves. These would "provide much of the information necessary and at the same time assist in the decision making process both on detail matters and major policy items," and would also assist in gaining the compliance of local ranchers. [82]

The advisory boards, somewhat patterned after the U.S. Forest Service advisory boards, evolved into powerful groups that guaranteed local input into virtually every facet of public grazing management. Since there was little money or time for scientific surveys, district advisory boards helped determine the carrying capacities of grazing lands. Those numbers could later be revised, if necessary. [83]

In 1936, a year after the grazing districts had been established, the Taylor Grazing Act was amended to specify who should be hired into the grazing service. The Civil Service Commission was ordered to consider those with prior "practical" range experience. The amendment further stipulated that "no Director of Grazing, Assistant Director, or grazier shall be appointed who at the time of appointment or selection has not been for one year a bona-fide citizen or resident of the State or of one of the States in which such Director, Assistant Director, or grazier is to serve." [84]

Thus, in another concession to Western livestock interests, federal grazing officials were required to be a resident of the state in which they were assigned.

The Taylor Grazing Act, like the U.S. Forest Service grazing policies 30 years before, left as its legacy a system of federal range management that favored close cooperation with the concerned local ranchers. The purpose of this partnership was to reduce competition on the depleted ranges and thus provide desperately needed stability for the rancher. It was hoped that if the local ranchers were a willing, integral part of the decision making process, then future resource protection was assured. The federal government seemed to realize that Western livestock owners knew how to play the game, but just needed a few referees to prevent fouls and fights. [85]

Through all this legislation and early federal grazing management decisions, resource utilization was considered to be the only interest in these lands. It was further assumed that the only ones interested in these lands were the ranchers and their multiple-use neighbors, the miners and timber harvesters. By the 1930s, few recreationists or tourists were using -- let alone traveling through -- most of the lands "valuable only for grazing." The only visitors that would come through these desert and mountain ranges were, most likely, on their way to a national park or monument where (supposedly) there was no grazing. It would take several more decades before tourists and environmentalists recognized the recreational potential of the Western ranges. In the meantime, as the federal advocate of preserving natural resources as scenery, the National Park Service would continue to confront the prospects of grazing on its own lands.

One of those confrontations, of course, centered on, Capitol Reef. Before examining the impacts of grazing and its management on national monument and park lands, it is first important to look at the evolution of grazing in the Waterpocket Fold country of south-central Utah.

Grazing In And Around Capitol Reef Prior To

1937

Early Grazing Patterns In The Waterpocket Fold

Country

The first livestock ranchers in or close to what is now Capitol Reef arrived in the 1870s and 1880s. Due to the area's small population and its physical isolation, however, there are few outside accounts detailing ranching practices in the Waterpocket Fold country prior to the Taylor Grazing Act. [86]

In this rugged, varied land, ranchers were free to graze their herds between the high-elevation summer pastures, on mountainsides rising over 10,000 feet, and the surrounding labyrinth of desert canyons and mesas, which provided winter range. Those who came later, especially after the national forest permit system was established in the early 1900s, ranged their sheep and cattle on the still unrestricted deserts year-round.

The effects of this unrestricted and highly competitive grazing were noticed in the Waterpocket Fold country in the early 1900s. Nethella Griffin, a long-time Boulder resident and daughter of prominent rancher John King, described the situation then:

[It was a] period of struggle between cattlemen and sheepmen and among individuals for control of the range. Every year the country became worse overstocked until, beginning in 1902 there were several years of drought that naturally intensified the evil of overgrazing. Cattle died by hundreds....By 1905 the rich meadows on the mountain plateau had turned to dust beds. Sheep, bedded in the headwaters of the mountain streams and dying in the water ditches, so befouled them that ranchers' families could hardly get a decent drink of water. Cattle bones bleached on the dry benches and around mudholes and 'loco' patches, these poisonous weeds seeming to grow after other forage was dead and to attract starving animals with a false promise of food. [87]

The U.S. Forest Service arrived on the scene when Fishlake National Forest was established northwest of the present National Park Service boundary in 1897. Powell (later part of Dixie) National Forest, adjoining Capitol Reef to the west, was created in 1905. The first known figures for cattle and sheep grazing near Capitol Reef are the Powell National Forest numbers, which presumably cover the summer pastures of those who grazed the Waterpocket Fold areas in the winter. In 1909, the U.S. Forest Service issued permits for 67,000 sheep and 11,000 head of cattle. These numbers gradually rose to 75,000 sheep and 13,800 head of cattle 10 years later. [88]

According to a draft history of the Dixie National Forest, the early years of U.S. Forest Service jurisdiction were not easy:

From the time the National Forests were established Dixie Forest officers have worked long and hard to find out what was actually taking place on the ranges due to heavy grazing use. Vegetative changes were so very slow that it was always difficult to be sure whether the range was getting worse, holding its own, or in some cases getting better. Differences of opinion were nearly always present. Stockmen generally felt that the range was getting better. World War I brought demand for more meat and as a result permitted stock in 1917 reached the peak numbers on the Dixie Forests. Since that time there has been a sustained effort to reduce numbers. In most cases the productivity of the ranges fell faster than reduction of livestock numbers which resulted in cut after cut with no apparent improvement of the range as a result. Reductions down to 1/3 of the 1917 load were not uncommon. In spite of this there was no apparent upward trend of the range established. [89]

Geologist Herbert Gregory, who made extensive geographic and geologic surveys of southern Utah throughout the early 20th century, confirmed the findings of the forest service:

The pioneer settlers, with small herds and flocks, before the native vegetation had been disturbed, were surrounded by conditions usual for stock ranges. 'Good years' of the period ending in 1893 were followed by bad years, culminating in 1896, when 'about 50 percent of the range stock died of drought and starvation.' Increased rainfall combined with the extension of grazing area...brought more favorable conditions. Overstocking of the range in response to the increased values of cattle during the World War appears to have been the first step toward the present unfortunate state. [90]

This pattern of use likely was common in the areas adjacent to the forest service and the Escalante area as reported by Gregory. In that case, is safe to say that southern Utah was following the cycles of good and bad years determined by climate, economics, and range deterioration found throughout the rest of the West.

As discussed earlier, the small, sometimes cooperative herds that were first on the range in the 1870s were soon increased by local ranchers responding to competition. By the early 1890s, the livestock depression reached into the isolated canyon country and combined with drought to bring on the first range crisis. By the beginning of World War I, increased demand for livestock and a series of wet years once again brought larger herds of sheep and cows onto both the forest and lower desert ranges. Then, the post-war agricultural recession and a return to drier times throughout the 1920s left the range and the livestock owners in the worst shape yet.

Other accounts concur that the range in and around Capitol Reef was already severely damaged by the early 1930s. A West Henry Mountains range survey, completed by the Bureau of Land Management in 1963, provides a brief description of past grazing use on the east side of the Waterpocket Fold. [91]

According to this survey, there was no domestic livestock use prior to 1875-76. Then in the early 1900s, Willard and George Brinkerhoff, William Meeks, and Will Bowns brought large herds of cattle to the area. At about the same time, Bowns also introduced the first large herds of sheep. By 1914, according to the report, sheep began to replace cattle on the range, and by 1928 sheep had largely replaced the cattle. [92] The U.S. Forest Service permit system also played a significant role in pushing more woolgrowers onto the still unrestricted desert range for the entire year. [93]

The BLM survey also includes portions of a 1948 interview with Mr. and Mrs. George Durfey, who brought their family and sheep to Notom in 1919. [94] The interviewer, Range Conservationist Ben S. Markham, recorded the situation that existed when Durfey first arrived:

[T]he range was heavily loaded with stock. The Bowns ran seven big herds of sheep, averaging 2,500 to 3,000 head per herd. Mr. Durfee [sic] ran 600 head of cattle and he was considered a small operator. Mr. Durfee said that at that time the same vegetative types were in existence, but with much better density than at the present time. The Sandy Ranch development was started in 1904. Mrs. Durfee remembered that in 1911 the Sandy Ranch was raising alfalfa. Mr. Durfee stated that the deep wash cut in the bedrock on the north side of the Sandy Ranch on Oak Creek was there when he first went into the country....The wash on Bitter Creek Divide has cut in the last forty-five years [since the early 1900s]....He attributes the accelerated erosion that is present in much of the Henry Mountain area to overuse by grazing livestock. [95]

George Durfey's son, Golden, spent much of his early life herding sheep in the Henry Mountain and Waterpocket Fold country. In a 1992 interview, Golden Durfey recalled that before the Taylor Grazing Act there were numerous herds, all in competition for the same ranges. [96]

Contributing to the impacts on the range were the enormous sheep-shearing pens at the Durfeys' Notom Ranch and at Sandy Ranch just a few miles to the south. Golden Durfey remembered that his family's sheep shearing operation lasted for about 45 days each spring, when as many as 30,000 sheep would be shorn. [97] The BLM survey reports:

From the year 1900 up to 1934 when the Taylor Grazing Act was passed, some 50,000 sheep were sheared annually at pens in Notom on the north and at Sandy Ranch. During the shearing period these sheep were allowed to graze unrestricted on the surrounding public domain. This condition, with unrestricted grazing from the ranches, depleted the range forage in the upper valley to a point where Russian thistle predominates, and sheet, gully and wind erosion is prevalent. [98]

While heavy, competitive sheep grazing predominated on the eastern side of the Waterpocket Fold, sheep and cattle were also roaming unrestricted in what is now the northern district of Capitol Reef National Park. On the Hartnet Mesa section, between the South and Middle Deserts, another BLM survey described past use:

Prior to passage of the Taylor Grazing Act in 1934, large numbers of livestock were brought from Wayne, Sevier, and Emery Counties to winter on these lands. Many of the animals remained on the range year-long, resulting in progressive destruction of soils and vegetation. Reports from stockman [sic] in the area indicate that many trespass horses used the area until about 1955. Prior to 1946 there were at least 163 cattle and 20 horses licensed yearlong in this area. [99]

Guy Pace, a prominent rancher whose livestock graze on the Hartnet, believes that the majority of these large herds belonged to out-of-state operators. [100]

This pattern of unregulated, competitive range coupled with economic depression and drought is the same pattern found elsewhere in Utah and throughout the West led to the perceived need for federal regulation. That regulation turned out to be first the U.S. Forest Service permit system and, ultimately, the 1934 Taylor Grazing Act.

The Taylor Grazing Act's Impact On The Waterpocket Fold

Country

While the onset of grazing regulations in the national forests exposed many ranchers to the allotment and permit system as early as 1905, passage of the Taylor Grazing Act in 1934 made it impossible to avoid federal supervision. The first director of grazing, Farrington Carpenter, had determined that the only successful means of enacting grazing regulations was through the hands-on cooperation of local ranchers, just as the U.S. Forest Service had concluded at the turn of the century.

At a meeting on October 22, 1934, Carpenter and his staff met with a delegation of 300 Utah cattle and sheep operators in Salt Lake City to familiarize the area ranchers with the Taylor Act's details and to gather information unique to Utah's ranges. In December, another meeting was held. This one was attended by approximately 200 livestock representatives, who met in Salt Lake to draw the boundaries for eight grazing districts in Utah. [101]

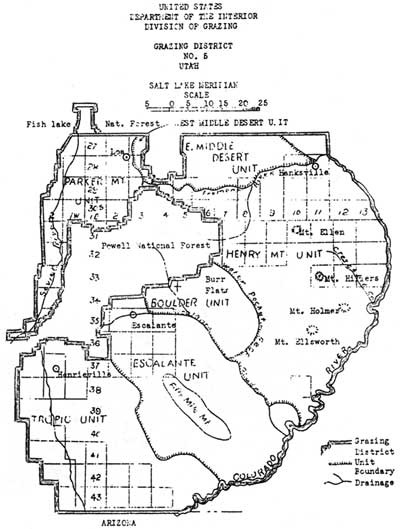

The area that includes Capitol Reef National Park was placed in Grazing District 5, officially established on May 7, 1935 (Fig. 34). [102] Each district had an advisory board, elected by its permittees, responsible for setting the original carrying capacities and the first line in settling disputes. The districts were then divided into allotments with one or several common users. Community and individual allotment committees were charged with setting up their own preliminary capacities and periods of use. [103] While it appears permits were issued almost immediately, they must not have carried much weight since permit priority was not clarified until January 1936 and the district offices were not established until a year after that. [104]

|

| Figure 34. Utah Grazing District #5. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

At the January 1936 meeting in Salt Lake City, representatives from all the district advisory boards throughout the West gathered with the fledgling grazing service to decide on long-term regulations, the most important being the establishment of range fees and standards for grazing permits. Fees were initially set at five cents an Animal Unit Month (an adult and unweaned infant per month) for cattle and horses, and one cent an animal unit for sheep and goats (5 sheep = 1 AUM). [105]

Grazing permits, patterned after the forest service requirements, were to be issued according to a specific order of preference. First choice went to those with prior use (those with range claims for the previous five years) who had sufficient private or commensurate lands adjoining or close to the range in question. This decision was in line with the Taylor Grazing Act's original wording, and was also consistent with the traditional tenets of private property and prior use. Secondary permit priorities were for those with commensurate property but no prior use, followed by those with prior use but little or no property, and finally, everyone else. [106]

The link between property, prior use, grazing fees, and district advisory boards ensured that local, established users would carry the most weight in determining how the public domain would be used. The stabilization of the livestock industry, one of the primary motivations for the passage of the Taylor Grazing Act, was virtually guaranteed by this kind of system. It would be up to the U.S. Grazing Service and, after 1946, the Bureau of Land Management, to develop the other motivation: rehabilitation of the range.

At first, and some would say ever since, the federal officials charged with monitoring these new regulations were too few, and were too poorly funded to implement successful range conservation. Due to the lack of appropriations and manpower, the district graziers concentrated on means by which they could constructively cooperate with the local ranchers to gain their trust for the future.

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (ERA) range improvement program was significant in showing ranchers that federal action could be positive. In its first year, the grazing service was given 60 Civilian Conservation Corps camps with approximately 12,000 workers to develop range improvements throughout the West. At that same October 1934 meeting with the ranchers and Director Carpenter, the Utah office of the ERA discussed potential improvement projects with the livestock operators. They determined that "work consisting of development of springs and seeps, construction of small reservoirs, drilling of wells, and the installation of tanks and troughs, would best serve the most pressing needs." [107]

Roads and stock driveways were also built with this unique federal assistance. With $200,000 of ERA money allocated to Utah one week later, advisory boards of ranchers met with the ERA engineers to determine what projects would benefit the most people. [108] In Garfield and Wayne Counties alone, 37 springs were improved for livestock use, four wells dug, four stock reservoirs built, and five trails either constructed or improved. While it is hard to determine if any of these range improvements is within Capitol Reef National Park, the names of these projects (which often reference local landmarks) suggest that at least a half dozen of these federal relief range improvement projects were completed within what is now the park boundary. [109]

Another early focus of federal management of the Waterpocket Fold country was eliminating some of the competition between sheep and cattle on the desert winter ranges. In 1935, competing Wayne County sheep owners and Garfield County cattle ranchers went to a U.S. Grazing Service hearings officer in Richfield to plead their cases. The sheep owners said they needed at least one month of winter grazing in the Circle Cliffs as part of their annual herding cycle. The cattle owners, who lived in the Boulder area close to the Circle Cliffs range, complained that the sheep grazing had destroyed their traditional, and now federally approved, range. During the course of testimony, Boulder rancher John King emphasized the adverse vegetation change resulting from this competition between cattle and sheep:

[All that's left is] a little shadscale, sagebrush, about all killed. No grass at all to amount to anything, only way on the ridge farthest away from water. But along the head of Horse Canyon or in the Flats there is some sagebrush there but it is pretty well killed. All the [Brigham] Tea is killed out there. Not much grass or browse. Spots of shadscale and sagebrush. [110]

The hearings officer concluded in favor the Boulder cattlemen, principally because they had prior use and could demonstrate closer commensurate property. Specific cattle and sheep allotment lines were drawn that effectively eliminated the Wayne County sheep herds from legally venturing onto the Circle Cliffs. Anne Snow observed that this curtailment of the range, coupled with cuts in the national forest sheep permits, drove some sheep owners out of business and caused others to switch over to cattle. [111]

Increased regulation, a lack of herders, and predators were the main reasons why sheep numbers steadily declined after the Taylor Grazing Act. The impacts of uncontrolled, year-long competition between sheep and cows throughout the late 19th century and into the 1930s is still evident on much of the grazed land along the Waterpocket Fold, including much of Capitol Reef National Park. Later attempts to rehabilitate the land by the Bureau of Land Management will be examined below.

Early Relationship Between Ranchers And Federal Land

Managers

As mentioned earlier, the beginning of the forest permit system had exposed some tensions between traditional users and new federal attempts to regulate resources. The Great Depression and war years of the 1930s and 1940s created further hardships, as well as determined resistance, from some ranchers opposing further U.S. Forest Service controls.