|

Capitol Reef

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 11:

FROM MONUMENT TO PARK, 1969 TO 1971

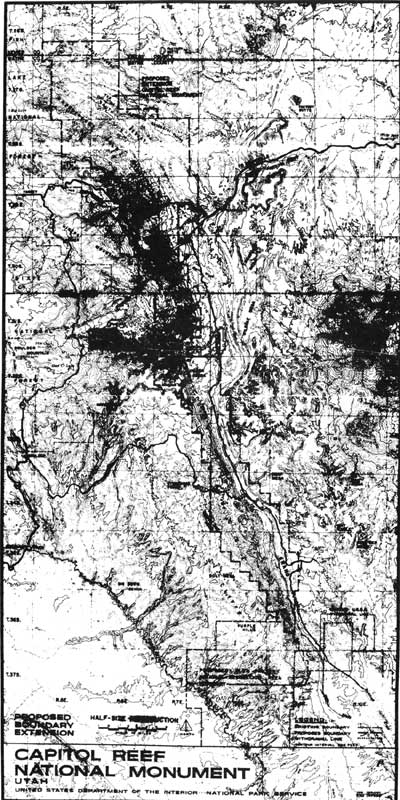

Before addressing the reaction to Capitol Reef's expansion, let us first examine the new boundaries and resources enclosed in the enormously enlarged monument. A total of 215,056 acres were added to the existing monument. This land was added to the national park system because, in the words of the proclamation,

it would be in the public interest to add to the Capitol Reef National Monument certain adjoining lands which encompass the outstanding geological feature known as the Waterpocket Fold and other complementing geological features, which constitute objects of scientific interest, such as Cathedral Valley. [1]

The key scientific qualification (required by Section 2 of 1906 Antiquities Act, which authorizes these presidential proclamations) of the Capitol Reef expansion was the same as that singled out in the initial enabling proclamation back in 1937: the unique geology of the Waterpocket Fold.

Proclamation #3888

According to the December 1968 press release that accompanied the inauguration day proclamations, "only a fraction of the dramatic structure and the geologic story" were protected within the old monument boundaries. The press release declared:

Now, with the addition of 215,056 acres, the entire Waterpocket Fold running north to south and striking downward west to east, is brought within the National Park System in order to present a complete geologic story and to preserve in its entirety this classic monocline. Seventy miles of it are now in the national monument in Wayne, Emery, and Garfield Counties [a little portion in Sevier County was also included]....Included in the north end of the enlarged Capitol Reef National Monument is Cathedral Valley. As its name implies, the valley contains spectacular monoliths, 400 to 700 feet high, of reddish brown Entrada sandstone, capped with the grayish yellow of Curtis sandstone. These colorful "cathedrals," many of them freestanding on the valley floor, provide unusually striking land forms." [2]

The new boundary lines were drawn along section lines and gave the monument the look of a long, jagged comma across the western Colorado Plateau, just like the geologic fold it now protected (Fig. 29). There was not a lot of land added to either side of the actual fold, but it included:

1) the Hartnet Mesa and South and Middle Deserts that make up Cathedral Valley north of the actual fold (an area Charles Kelly had argued worthy of National Park Service protection back in the 1950s);

2) a little land on the west and east of the former monument boundaries as requested by Superintendent Heyder to insure that the Scenic Drive was well within the monument and that the scenic views seen by most visitors were not compromised by any future encroachments; and

3) several dozen sections to the south were included at the eastern base of the Fold and also extended slightly onto the scenic Circle Cliffs plateaus to the west.

|

| Figure 29. Expanded boundary of Capitol Reef National Monument, January 1969. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The eastern boundary was likely set to include the beautiful Strike Valley as well as the north-south running Notom-Bullfrog Road. It also spread onto Big Thompson Mesa, which is directly east of and above Halls Creek. It is interesting to note that the southern boundary was just below the Fountain Tanks - natural waterpockets used by travelers and stockmen for 100 years. The spectacular Halls Creek Narrows were not included in the 1969 proclamation nor in the proposed Glen Canyon National Recreation boundary, which was southwest and southeast of the new monument boundaries. [3]

The most significant problems with this ambitious expansion concerned land use. The new monument boundaries now embraced an additional 25,280 acres of state land and 1,080 acres of private land, as well as an estimated 11,000 mining claims, 26,000 acres of oil and gas leases, and 62 grazing permits allowing as many as 6,000 AUMs (Animal Units per Month, or as much as a cow and her calf or five sheep can eat in one month). [4] The proclamation specified that all valid, existing rights, such as mining claims, would be protected. In addition, the proclamation reiterated Capitol Reef's previous proclamations of 1937 and 1958:

Nothing herein shall prevent the movement of livestock across the lands included in this monument under such regulations as may be prescribed by the Secretary of the Interior and upon driveways to be specifically designated by said Secretary. [5]

The new monument boundaries now protected a great deal of geologic and scenic splendor and an abundance of high desert resources. The problem was that, by expanding the monument at the relatively late date of 1969, any remotely promising mining or grazing land was already claimed. Thus, the National Park Service would be forced to allow mining and grazing in the new monument lands until either the claim or permit could be proven invalid, phased out, or purchased.

Managing these additional resource uses has proven to be at least as difficult as protecting the unspoiled, natural resources of older national parks and monuments. Yet, even before the staff at Capitol Reef could venture into managing its new lands, attacks from neighbors, multiple-use advocates, and the Utah congressional delegation put the National Park Service on the defensive just to save the newly expanded monument.

Initial Reaction To Capitol Reef Expansion:

Jan.-Feb. 1969

That third week in January 1969 saw a flurry of questions and responses that plunged Capitol Reef management into chaos. As mentioned earlier, Superintendent Heyder was unsure of the exact placement of the new boundaries. Thus, when the news leaked, Heyder could do no more than stall for time. The problem was exacerbated by the fact that copies of the specific proclamation and boundary map were not sent directly to the regional office or to the park. Heyder had to wait several days after the inauguration (January 24) to get a copy of the Federal Register with the exact expansion boundaries. [6]

Heyder recorded a number of information requests from ranchers, miners, reporters, forest service, and Utah highway officials, who all wanted information on the new boundaries. [7] The superintendent could only promise to let them know the specifics as soon as he, himself, knew them. In a January 23 editorial, the local Richfield Reaper reported, "Capitol Reef personnel were aware of some type of expansion plans, but indicated that what had been talked of and what the proclamation would include will be two different things." [8]

The failure to inform Superintendent Heyder immediately of the expanded boundaries enabled the opposition to spin out of control with unsubstantiated rumors. It also didn't help that Heyder and his staff had no idea what grazing and mining claims existed in the new addition.

According to Heyder, George Hatch, president of the KUTV television station in Salt Lake City and supporter of the expansion, borrowed a detailed grazing allotment map from the BLM, ostensibly for his own research. Hatch loaned the map to Heyder for two days before it had to be returned. All this happened after the proclamation had been issued. The lack of information from the Washington and regional offices was very frustrating for the superintendent. The Richfield Reaper quoted Heyder as saying:

It's embarrassing to us at Capitol Reef to be asked about the proposal when we can't give any answers. Rumors are flying at a brisk pace, including one which states that the west boundary will go to Bicknell [22 miles away]. [9]

The most celebrated initial act of opposition came from the town of Boulder, where resident ranchers and speculative miners had claims to the southern half of the Waterpocket Fold. The day after the inauguration, before any specific boundary information had been released, the five-member Boulder Town Board passed a resolution changing the name of the town to "Johnson's Folly." According to Board President Cecil Griener, the Capitol Reef addition would eliminate winter grazing for cattle raised by Boulder ranchers, thereby creating a ghost town surrounded by ghost ranches. [10] Apparently, Griener and the Boulder Town Board were under the impression that the entire Circle Cliffs area east of Boulder was to be included. This inaccurate rumor continued to spread and could not be quashed by National Park Service officials because they themselves did not know the exact boundaries. Until they did, there was plenty of grist for the opposition rumor mill.

Other immediate local resistance was voiced in regional newspapers such as the Richfield Reaper, and in a Utah House of Representatives resolution introduced by Royal Harward of Wayne County. These objections were not surprising, given Southern Utah's customary land use habits. The objections coming from Utah's congressional delegation, however, were of greater concern.

In the weeks preceding the proclamation, both Utah senators were active in Utah tourism and land use issues. Sen. Moss introduced two bills to aid tourism and the southern Utah parks. This legislation would create a Canyon Country National Parkway from the Glen Canyon Dam to Grand Junction, Colorado, and sponsor a large-scale development survey for the Colorado Plateau parks and monuments. [11] Meanwhile, Sen. Bennett was resisting efforts by the interior department to raise grazing fees, as well as other plans that he believed would "have a serious negative economic impact on ranchers and their communities in Utah." [12]

Then, on Friday, January 17, Udall met with the entire Utah congressional delegation, informed members of the impending proclamations affecting Arches and Capitol Reef National Monuments, and then "swor[e] them to secrecy." According to Moss,

Secretary Udall said his department's examination showed no working mining claims in the two areas and very little grazing. He said there might be some 'tailoring' of the boundaries but that this will be up to Congress to decide. [13]

As mentioned in the previous chapter, Udall was optimistic that he had persuaded the Utah delegation that the monument expansions would be good for their state. Once the news leaked late that same day, however, Moss issued a statement calling for field hearings similar to the ones he'd conducted for his Canyonlands National Park legislation several years earlier. Also on January 17 (whether before or after the Udall meeting is unknown), Bennett reintroduced his bills to create Arches, Cedar Breaks, and Capitol Reef National Parks within their old monument boundaries. Bennett also warned, "I will insist on field hearings on my bills and I want to make certain that mining rights and the likes are fully protected." [14]

Two days after the proclamation, Moss introduced Senate Bills 531 and 532, which would "designate these enlarged areas as national parks." The purpose of this action, according to Moss, was to insure that Congress had a major role in deciding the areas' future that local opinion was considered, and that, in the long run, tourism would increase. As a Democrat who had previously guided the Canyonlands National Park legislation through Congress, Moss seemed generally supportive of the proclamations. [15]

The Utah congressional delegation's reaction to the proclamations split along party lines, lone Democrat Moss supporting expansion and the Republicans opposing any expansion at that time. Yet, they all supported changing Capitol Reef's status from a monument to a national park, primarily because national parks attracted more tourism.

By January 31, the overwhelmingly negative reaction from within Utah fueled Bennett's offensive against the "land grab." On that date, Bennett introduced into the Congressional Record several newspaper articles and editorials in opposition to the Arches and Capitol Reef expansions. [16] Moss, on the other hand, introduced a newspaper article from The Ogden Standard-Examiner that supported the monument expansions and urged national park designation for the areas. [17] Yet Moss was the lone vocal supporter in those first few weeks.

On February 5, Bennett sent a letter to 16 leaders or advocates for multiple-use, including the state directors of lands, natural and water resources, and the heads of the state mining and livestock lobbies. Bennett spelled out his plan to eliminate the expanded boundaries and make the former national monument lands into national parks. He added, however, that "maybe there is other land, less in volume than the amount taken, which perhaps should be added." He desired information, "guidance and a frank expression of the problems... that this action ha[d] created." He sought details on potential grazing and mining possibilities in the lands included in the Arches and Capitol Reef proclamations, as well as sites for future roads and facilities. This letter was an effort on Bennett's part to get additional facts on the growing controversy. Since the letter was sent only to multiple-use advocates, though, one could conclude that the senator's mind was already focused toward continued opposition. [18]

The first official step in opposition was taken when Sen. Bennett and fellow Republican Rep. Lawrence Burton introduced bills on February 7 to limit the size of any future national monument to 2,560 acres. According to Bennett, this would "preclude future unilateral executive action involving thousands of acres of land." [19] This was followed by some inflammatory testimony at the Republican-sponsored Lincoln Day meetings conducted by Bennett and Burton in Moab and Escalante one week later.

Burton and Bennett's opinions were, by now, well known. Both were adamantly opposed to what they now consistently called "that illegal land-grab," but they showed a willingness to negotiate on some land increases and/or national park status. The first stop on their southern Utah tour was Monday, February 10 in Moab, where some 200 people gathered to express their opinions on the proclamations. According to newspaper reports, the only voice in favor of the proclamations was that of Superintendent Bates Wilson of Arches and Canyonlands. He informed the senators that the expansion was needed to give the monuments enough protection to justify national park status. [20]

The overwhelming concern at the Moab meeting was the anticipated effect of the additions on the local economy. While it was reported that most in attendance favored a guaranteed phase-out of grazing and mining interests within the new boundaries, the director of the Utah Geological Survey argued that Capitol Reef National Monument should be reduced back to its previous size to free oil and tar sands deposits that were "one of Utah's greatest economic potentials." [21]

After a day touring Arches, Burton and Bennett flew over Capitol Reef before landing in Escalante for a Lincoln Day dinner and town meeting. Heyder and Chief Ranger Bert Speed drove over to Escalante and, at first, could not find the dinner site since both the gas station attendant and grocery store butcher refused to talk with National Park Service officials. Once at the dinner, Heyder was asked by Bennett and Burton to sit at the head table and provide answers at the next day's town meeting. [22]

According to Heyder, the predominant concern of those at the Escalante town meeting was the expected impact on grazing. When Heyder attempted to reassure ranchers that existing stock driveways would not be affected and that grazing privileges within the addition would be addressed in time, Burton said sarcastically, "Well, folks, that's the Department of Interior answer for you." Heyder was upset by this obvious put-down, but after the meeting Burton assured him that it was only politics and that Heyder had answered all the questions quite well. [23] There are no transcripts of these informal meetings, and the Ogden Standard-Examiner was the only Utah paper to report on the Escalante segment of the trip. After the dinner on February 11, Bennett stated:

What I heard tonight is similar to what I heard in Moab last night. These people are not so much concerned with the withdrawal as with the way it was handled. No hearings were held. No people were contacted. It was merely a last minute land-grab by the Johnson administration. [24]

With their congressmen backing it up, the local resistance rhetoric only increased. To demonstrate the negative impact Capitol Reef's expansion would have on the neighboring economies, 41 families claiming at least partial grazing rights within the new boundaries gathered at the Wayne County seat of Loa to publicize their plight. Don Pace, rancher and Wayne County commissioner, testified:

Most of us have been in the ranching business here all our lives. Our fathers and grandfathers pioneered this part of the state, long before there were any national monuments or parks. We have worked all our lives to improve the cattle industry here and have built our homes and lives on this business. Now with a stroke of the pen, all this is headed for doom. [25]

According to Pace, the families were willing to accept the new monument boundaries so long as traditional winter grazing was allowed to continue. In late February, however, the National Park Service had yet to decide what to do about the grazing privileges. Left hanging, Pace and the others pressed their case and voiced their pessimism:

We just don't know what we will do or where we can go....It's a real problem because most of us are full-time ranchers and don't have any other business to fall back on. We are just hoping that Congress will realize that we are people and not statistics, and that just because there are only 200 of us, we shouldn't have to be written off for some political whim. [26]

The outcries against expansion were inevitable in such an isolated, conservative region historically dependent on multiple-use land. No matter when or how the proclamation was announced, the monument's enlargement would have been seen as another high-handed act by a federal government oblivious to struggling local economies. Nevertheless, the political struggles that delayed the proclamations until the final hours of the Johnson administration, and the uncertainty and secrecy that left the field personnel so unprepared, fueled panicked rumors among Capitol Reef's neighbors and rhetorical attacks from Washington politicians.

Of course, not all opinion opposed the proclamations. Shortly after the Bennett and Burton town meetings, Sen. Moss met with Utah conservation leaders and tourism promoters to discuss the enlargement issue. Moss told the group that he had asked the Bureau of Land Management and the National Park Service to investigate the multiple-use potential of the areas in question. He also appraised them of the Bennett and Burton legislation proposals and of his own plans to hold Utah hearings in the near future. The group agreed that the people of the area simply didn't realize the long-term benefits the enlargements and national park status would have for tourism business. Some also pointed out that the increased grazing fees from the previous year "helped stir the emotions of the opponents of the enlargements." The group felt that the hearings should be delayed for at least another month to let resistance subside. [27]

Once the immediate furor over the proclamation died down, it was up to Bennett, Burton, and Moss to orchestrate legislation that would finalize Capitol Reef's boundaries and status. That it took an additional two years to pass the Capitol Reef National Park bill signifies the continued controversy over the initial proclamation, the strength of the multiple-use argument, and the complex resource issues involved.

The Proposals Of Bennett, Burton, And

Moss

Bennett, Burton, and Moss each had his own plan for Capitol Reef National Monument. On March 17, Sen. Bennett introduced amendments to his bills to make Capitol Reef and Arches national parks. The amendments clarified the boundaries as being those as of January 1, 1969--prior to the expansion proclamations. [28] Fellow Republican Burton also favored reducing the monument's size, but would be willing to include some of the newly added lands with no grazing or mineral potential. [29]

If these Republican-sponsored bills became law, they would supersede President Johnson's proclamations. The problem Bennett and Burton faced was that theirs was the minority party. Because there was little chance of their bills passing without significant amendment, the legislation introduced by the Utah Republicans was clearly intended to represent local opposition to the "land-grab."

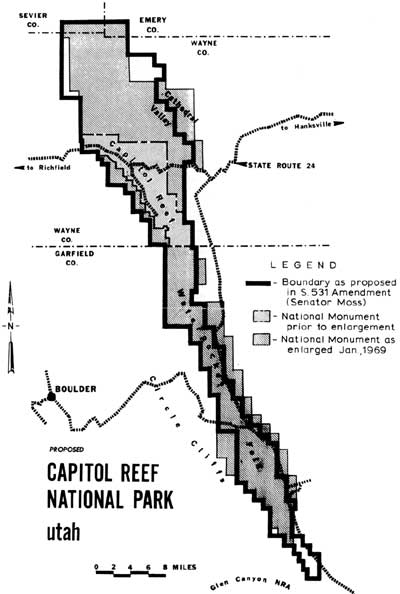

Meanwhile, Moss' plan was to eliminate 56,000 acres in favor of 29,000 acres not included in the January 20 proclamation, for a net decrease of 17,280 acres. After an inspection tour of Capitol Reef and consultations with National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, and University of Utah geologists, Moss established "what areas should be included and what might reasonably be excluded because of their unsuitability for national park status and the need to use them for other multiple-use purposes." [30]

Moss' bill, S.531, as amended, would trim lands from either side of the southern half of the fold and in the eastern Hartnet and Blue Valley areas northeast of Fruita. The goal, according to the senator, was to "remove much of the land under grazing permit." Moss also introduced amendments that would allow grazing permits to continue under the present holders and their heirs. [31] In return, Moss proposed to add land in the lower and upper Cathedral valley and extend the monument boundary to include the Halls Creek Narrows (Fig. 30). To gather support for his bill, Moss scheduled hearings in Salt Lake City on May 15, in Richfield on May 16, and in Moab the following day.

|

| Figure 30. National park boundary as proposed by Sen. Frank Moss, 1969. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Financial, Staffing And Management

Concerns

Before the hearings could be convened, however, Rep. Wayne Aspinall made good his threat to President Johnson by denying funding to any of the newly expanded monument lands. As chairman of the House Interior Committee, Aspinall had significant influence over the entire National Park Service budget. He based his decision on the principle that

Congress had not been consulted before the presidential proclamations were signed. It is interesting to note that while he refused to authorize spending for the new monuments, Aspenall was encouraging full funding of national recreation areas and expanding agency "manpower to cope with crime, crowds, and cars." [32]

It is unclear what lasting effect Aspinall's decision had on Capitol Reef, but the fact that the monument had been expanded by six times while at less than full staffing for its original size had park management worried. Even before the monument was expanded, financial constraints were felt at Capitol Reef. Superintendent Heyder had to lapse the protection ranger and maintenance foreman positions due to a reduced budget during the 1969 fiscal year. The public felt this financial pinch when the monument was forced to close the campground for the winter and reduce visitor center operations to only five days a week. [33]

Then in early March 1969, as the expansion controversy was at its peak, there was a major restructuring of the southern Utah parks and monuments. The plan called for a Southern Utah Group headquarters at Cedar City to serve as a mini-regional office for Zion and Bryce Canyon National Parks and Capitol Reef, Cedar Breaks, and Pipe Springs National Monuments. This cluster idea was designed to enable general administrative, management, and planning activities to be coordinated within one central office, thereby reducing the workload and the need for staff increases at the park level. To accomplish these goals, the Zion National Park superintendent became group superintendent; so Superintendent Oscar Dick moved to Zion from Bryce Canyon. Robert Heyder was chosen to replace Dick at Bryce Canyon, and Chief Ranger Bert Speed served as acting superintendent for Capitol Reef until a new superintendent was appointed. [34]

While this plan may have been a worthy attempt to increase efficiency, the fiscal restraints and personnel shifts could not have come at a worse time for Capitol Reef. Besides the financial and staffing hardships, the most significant damage caused by this reorganization was removing Heyder from Capitol Reef just when continuity was crucial.

As it turned out, the new superintendent for Capitol Reef, William Franklin Wallace, played a small role in the monument to park process, leaving Bert Speed to take care of virtually all the correspondence, planning, and congressional testimony.

The Southern Utah Group itself proved short-lived. In August 1972, the cluster concept was abandoned and the parks and monuments returned to their old organizational structure--with one difference. Capitol Reef was, by then, a national park. [35]

Congressional Hearings: May

1969

The U. S. Senate Parks and Recreation Subcommittee, chaired by Sen. Alan Bible of Nevada, began its Utah hearings in Salt Lake City on May 15, 1969. In his introductory remarks, Sen. Moss pointed out that he had not approved of President Johnson's method of adding National Park Service lands in Utah, since it had not involved public hearings and congressional debate. Moss was, however, impressed by the new monument lands and favored creating national parks out of the monuments with only slight alterations. [36]

Moss' proposed changes would reduce the total acreage of Capitol Reef from the 254,242-acre monument to a 242,257-acre national park. As mentioned above, the areas added to the boundaries included the Halls Creek Narrows in the south, and Cathedral Valley, Temples of the Moon and Sun, upper Deep Creek, and Paradise Flat in the northern district. Since some grazing would still remain within the newly proposed park, Moss provided amendments that would protect the permittees, proposing:

[G]razing permits held at the time the acts establishing the Arches and Capitol Reef National Parks are signed, may be continued and renewed during the lifetime of the holder and the lifetime of his immediate heirs. This is, incidentally, the same provision which was contained in my original Canyonlands National Park Bill. It was accepted in essence in the version of the bill which the Senate passed but was modified in the House. [37]

Moss believed that a few cows would add charm to the scenery, whereas large herds would be a problem. The senator felt that compromises could be reached to "realize the most out of the spectacular scenery and unusual scientific phenomenon which these two areas afford, and at the same time protect the rights of those who have a different economic stake in the regions." [38]

Moss also pointed out that with the construction of Interstate Highway 70, to be completed just north of Arches and Capitol Reef by 1972, millions of tourists would be on their way to enjoy the scenic potential of five national parks--more than any other state at that time. Increased tourism, scenic protection, and continued resource development were Moss' reasons for sponsoring his national park bills. He realized some would perceive him and fellow Utahns as "having [their] cake here in Utah and eat[ing] it too," but felt that appropriate compromises were attainable. Others testifying at the hearings were also willing to compromise--as long as their perspective carried the most weight.

The Salt Lake hearings were by far the most balanced. Of the 25 written statements included in the record, 13 opposed the Capitol Reef expansion, two were willing to accept the new boundaries so long as multiple-use privileges continued, and seven favored the Moss park bill. The National Park Service did not testify at these hearings. [39]

Don Pace, who had earlier represented the 41 families who believed their ranches would be lost to expansion, arrived with statistics to back his claims of hardship. According to Pace's figures, the 41 affected families would lose 5,331 AUMs, which would result in calf sale losses of up to $40,000 and would force the families to either go on social security or sell out and move away. Pace believed the entire economy of Wayne County would be adversely affected by the new park, testifying:

The economy of Wayne County, as are many of the counties in southern Utah, is greatly dependent on public lands. Eighty-eight percent of the land in the county is federally owned and administered. Most other counties in this region are in a similar position, with an average of about 75 percent of the land being federally owned. Any placing of large tracts of this land in single use will have serious effects on the already depressed economy in the area. Placing the land under single use, such as National Parks, terminates all oil and gas development, and all grazing rights are terminated, all mining operations stop, watershed and soil conservation stops, logging and lumbering stop, all hunting and fishing stops, and much of the tax base of the area stops. [40]

Vocalizing the feeling of many neighbors of Capitol Reef, Pace summarized:

I feel there is a great need for more local say, influence and control over factors of vital social and economic impact in the nation. Those who live in this area I know are a small minority, but we resent very much being controlled by politicians in Washington and special interest groups in other parts of the nation. Most of these people will never see our area and what few do will see it only on a passing through short visit basis, yet, they determine our livelihoods and the future course of our very existence. [41]

Pace was also concerned that the increase in monument acreage by six times could not be adequately developed for increased tourism since "even now the park service is not able to adequately care for and keep open all year the 39,000 acres included in the old National Monument." He wanted the roads and rights-of-way developed and feared that the National Park Service would be unable or unwilling to do so. In short, Pace supported Sen. Bennett's bill to create a national park from the old monument boundaries. This would make a more alluring tourist attraction while insuring that traditional land use would continue to the north and south. [42]

While rancher Pace provided an excellent example of the local opposition to the monument expansion and Moss' park bill, others testified that the multiple-use value of the land in question was vastly over-estimated. Wilda Gene Hatch, president of the expansion-supportive Ogden Standard-Examiner, agreed that hardships would occur if the grazing permits were immediately terminated. However, she wrote:

[I]t would be easy for the grazing land to be withdrawn over a period of at least 20 years. This 'staged phase-out' would permit the livestock owners to find replacement range on other lands. Over the long haul, the economic return to the country and state--and to the people involved--would be greater, we are confident, from spending of tourists than from the present, marginal livestock operations. [43]

As to the mineral potential, Hatch quoted from her paper's editorial of May 13:

[T]here are no proven reserves there of scarce minerals and the return from exploitation of the mineral resources is far more speculative than is the potential. There is no shortage in [other areas of] Utah of potash, oil, bituminous sand, oil shale, gas and uranium--the major minerals concerned. [44]

Like other supporters of S.531, Hatch believed that the loss of minimal grazing and mineral potential was far outweighed by the benefits of scenery protection and potential tourist developments. Hatch, who had attended the conservationists' meeting with Moss back in February, believed that tourist dollars would soon replace the lost ranching incomes in the affected areas.

As the hearings headed south to Richfield and then over to Moab, the testimony was similar but (as expected) heavily weighted in opposition to an expanded Capitol Reef and Arches National Parks. The testimony at all these hearings clarified the objectives of those in favor of and opposed to Moss' bill, without the hysteria that had greeted the initial proclamation news. By this time, it was clear that there would have to be some compromise of scenic, natural resources to insure grazing and mining privileges for at least several years. Supporters showed their willingness to compromise by supporting Moss' bill and amendments. Those in opposition, though, were still hoping that another, more favorable alternative could be found. When Republican Rep. Lawrence Burton arrived with his subcommittee to hold hearings in Escalante at the end of May 1969, those resisting monument/park expansion renewed their effort.

Burton invited Rep. Walter Baring of Nevada to bring his Subcommittee On Public Lands of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs to Escalante, to hear "testimony on the withdrawals of public lands by presidential proclamation for the expansion of Capitol Reef National Monument." Hearings on Arches National Monument had been conducted earlier. In addition to Baring and Burton (who was not a member of the subcommittee), Republican Rep. Don Clausen was invited to attend the hearings. Clausen, of northern California, had recently gone through his own national park debates over the newly created Redwood National Park. [45]

Robert Heyder, by this time superintendent at Bryce Canyon, was the National Park Service representative. He began the meeting by outlining the new monument boundaries. Then Clausen asked Heyder if any hearings were held or people informally contacted before the proclamation. Heyder answered that he did not know of any. [46]

Most of the testimony was similar to that at the Moss hearing, with many of the same speakers present. Garfield County Commissioner Dale Marsh spoke for the opposition:

Now, we are not opposed to national parks or monuments as such, but we would like the Government to make an economic analysis of each area as to its best use. In this way the public interests are best served. Park boundaries should be pushed back for the economical potential of the areas that are not affected. The recent monument extensions reduce the area for building our own state. This land now becomes a reserve desert or a mountain range that we can not use. [47]

One neighbor of Capitol Reef, Lurton Knee, favored the enlargement. Knee's Sleeping Rainbow Guest Ranch was one of the few tourist-oriented businesses in the area. Knee's property was also now within the new monument boundaries. Clearly, he had much to gain--or lose--with the resolution of this debate. He seemed to like Sen. Moss' bill, testifying:

We are strongly in favor of the enlargement--I should say, of modest enlargement--with the necessary adjustments for the cattlemen who need the portions of their grazing lands within the new boundary for winter feed. We feel this could be arranged for, as there is already a modified multiple-use in Capitol Reef National Monument by allowing the stock drives through the monument in the spring and fall. [48]

Knee also cautioned against any attempt to make a national park within the old monument boundaries:

We are strongly against withdrawing the new boundaries to the original 61 square miles and then attempting to make it into a national park, when there would be no necessity in trying to give such a small area 'park status,' when it could still be administered as a national monument and in turn the counties will lose the extra revenue which would be theirs if Capitol Reef is enlarged enough to become a national park. The other areas inside the new boundary are needed, not only for beauty, geologic interest, but for protection, especially lower Cathedral Valley and the unique selenite plug [Glass Mountain], as well as the magnificently awe-inspiring southern ramparts of the great Waterpocket Fold. [49]

A proponent of a modified expansion was George Hatch, president of KUTV in Salt Lake City and husband of Wilda Gene Hatch of the Ogden Standard-Examiner. Like Knee, Hatch believed multiple-use could be accommodated while also protecting the natural resources. The best way to do this, argued Hatch, was to adjust the boundaries from section lines to natural contours. This would allow grazing and oil and gas exploration in the not-so-spectacular flatlands to the east and in the Circle Cliff plateaus to the west. Hatch proposed a multiple-use national recreation area buffer zone to be created out of deleted portions east and west of the Waterpocket Fold. He also echoed Knee on the need to improve the monument in such a way that would protect natural beauty and increase the likelihood that it could be considered for national park status, arguing:

The monument can be substantially improved by adding scenic and scientific areas that have been overlooked in the present enlargement and grazing and mining can be accommodated by deleting many of the less important areas that have been included in the present enlargement and by placing substantial parts of the enlargement in a Capitol Reef National Recreation Area buffer zone in which grazing and mining exploration would be permanently permitted. Anyone who will take the time to walk through the deep canyons and spectacular formations of the Water-Pocket Fold will agree that it is well worth the time and effort to survey and draw proper boundaries for the benefit of many future generations. [50]

The opinions of Hatch and Knee aside, the vast majority of those speaking at the Escalante hearing on May 31 were ranchers, miners, and politicians opposed to the initial presidential proclamation. They did not contest a change to national park status, just so long as their traditional multiple-use lands retained that status.

The local hearings that the Utah congressional delegation had demanded back in January were now over. The focus shifted back to Washington politics as Moss, Bennett, and Burton tried to get some kind of legislation passed concerning Capitol Reef and Arches. Meanwhile, the National Park Service began to formalize its boundary alternatives and management objectives.

The National Park Service Makes A

Decision

Investigative field work began in March 1969, when Heyder, Bates Wilson, Acting Superintendent Speed, and several others made a three-day reconnaissance of the monument additions. Upon their return, Heyder developed management objectives for a very different Capitol Reef National Monument. [51]

The management objectives document, dated March 1969, stated that the purpose of the additions was to

preserve an area containing 'narrow canyons displaying evidence of ancient sand dune deposits of unusual scientific value' (50 Stat. 1856) and a world-famous monoclinal flexure–the Waterpocket Fold–which extends breathtaking scenery of stratigraphy and erosion for some 60 miles–connecting the high plateaus with the red rock rims of Lake Powell. [52]

The document continued, "The area is scenically unique, geologically significant, and biologically interesting. It offers visitors an unexcelled opportunity for exciting involvement in a fascinating wild area, ideally suited to investigation on foot."

Existing commitments listed included the stock driveway rights-of-way and special permits included in the old monument. There are no permits listed within the new additions. The major resources listed were, in order, geology, vegetative communities of which there were "numerous small niches hold[ing] endemic plant communities which are unique," and numerous historical and archeological sites "which [would] be managed under the administrative policies for historical areas."

The roads mentioned included Utah Highway 24 along the Fremont River, and the Burr Trail, which if paved would "change the traffic patterns of visitation" for all of southern Utah. The document recommended that National Park Service managers closely attend to the master plans of adjacent USFS and BLM lands. As for the local communities, Heyder described a growing investment of capital toward a tourist industry, but noted that it still had a long way to go. [53]

Heyder recommended that studies be made to determine "the carrying capacity of the several environments," since much of the area was fragile, desert landscape. Camping should be restricted to the main headquarters campground, with only small, primitive campgrounds at outlying areas. While hiking should be encouraged ("It is a hiker's park"), four-wheel drive use was appropriate along marked routes such as the Halls Creek, Oak Creek, and Pleasant Creek drainages, and in Cathedral Valley.

Heyder also recommended that mining and grazing be eliminated as soon as possible, as "grazing is directly incompatible with maintenance and restoration of the environment." Perhaps not surprisingly, this view was never mentioned by any expansion or park proponents during the congressional hearings in May.

The document also proposed that all inholdings be acquired "as funds and properties become available," and recommended that all future power and telephone lines be buried. To meet these concerns, Heyder proposed a variety of management objectives.

He recommended that visitor use and interpretation continue to be concentrated in the Fruita headquarters area, with the only outpost ranger stations to be built on the Burr Trail in the south and Cathedral Valley area in the north. Only established roads should be paved; mine access roads should be converted to hiking trails.

To insure continued preservation of the monument's expanded resources, the 1969 management objectives document gave priority to development of a plan that would:

obtain a complete and comprehensive inventory and evaluation of the area's resources which will provide the guidance for knowledgeable management decisions in preservation, interpretation, and development. A research program [would] be carried out to provide the basic knowledge in the dynamics of the various natural ecosystems involved. With such data steps [w]ould be taken, if practicable, to restore and maintain natural ecological conditions which existed before their alteration by Western Civilization. Areas of the monument... determined to be of historical significance [w]ould be managed as to perpetuate this value. [54]

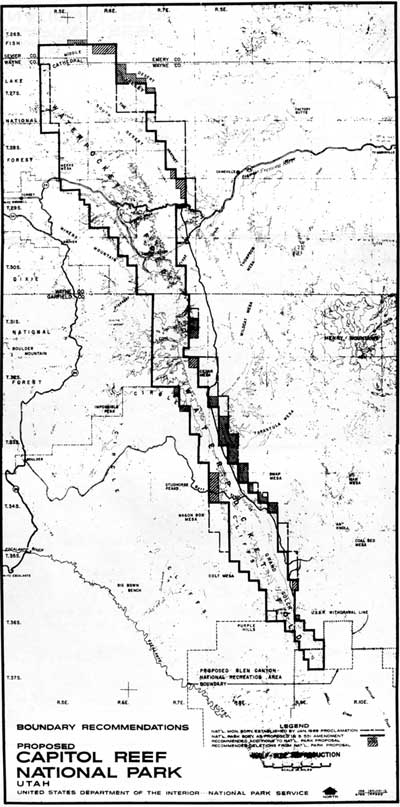

The objective of this plan was to gather a natural resource data base and then attempt to restore those natural conditions to areas altered by past grazing and mining practices. This could be accomplished if grazing and mining were significantly removed from the monument. This goal would become a resource management priority throughout the rest of the twentieth century. By June 1969, the National Park Service had determined its preferred boundaries for Capitol Reef National Park (Fig. 31). Except for a few additional sections added and some deleted from the proclamation boundaries, the National Park Service proposal was remarkably similar to Moss' S. 531. This proposal was slightly modified in August, mostly in the northwest corner of the proposed Capitol Reef National Park (Fig. 32).

Data-gathering related to the new monument resources and fiscal, physical, and personnel requirements would take a little longer to resolve. Since no bill pertaining to Capitol Reef National Monument made it out of committee for the rest of 1969, park service officials had the time they needed to gather data and proposals that could sway Congress to their point of view.

|

| Figure 31. National park boundary, as proposed by the National Park Service, June 1969. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Congressional Debate, 1970

By April 1970, the proposed Capitol Reef National Park legislative data had been compiled. Hearings in both the Senate and House were scheduled before the November elections, and the National Park Service was asked to respond to the various bills proffered by the Utah delegation. These hearings offered the National Park Service an opportunity specifically to address Congress on Capitol Reef legislation for the first time: all previous creation and expansion decisions regarding Capitol Reef had taken place solely through interior department investigations and presidential proclamations.

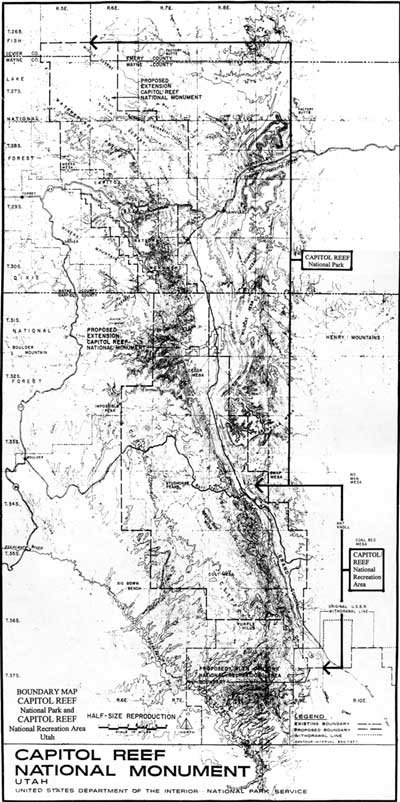

On April 23, 1970, Rep. Burton introduced his compromise to the Capitol Reef dilemma. His bill, H.R. 17152, would create a combined Capitol Reef National Park and Recreation Area of approximately 218,000 acres (Fig. 33). Burton's proposal was similar to both the park service and Moss plans, but it eliminated the heavily-grazed eastern half of Cathedral Valley and made the area south of the Burr Trail a multiple-use recreation area with grazing and mining. [55] By this time, Sen. Bennett was no longer actively promoting his bill (S.399) to return boundaries to their pre-proclamation size, instead throwing his support to Burton. This left the Republican Burton and Democrat Moss proposals the only ones working their way through committee during the second session of the 91st Congress. It should be noted that this Congress was still controlled by a Democratic majority that was in the midst of passing a significant amount of new environmental legislation largely encouraged by Richard Nixon, a Republican president.

|

| Figure 33. Rep. Burton's 1970 proposed boundaries, "National Park and Recreation Area." (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

An additional hearing on Moss' S. 531 bill was held on May 28, 1970. Since this hearing took place in Washington, it was poorly attended. In stark contrast to the Utah hearings, only Sen. Bennett issued a statement in opposition to the Moss bill. [56]

By this time, Moss' proposal had been refined from the one he had hastily offered the previous year. His park proposal would now include 230,837 acres--somewhat less than proposed the previous year. Moss' Amendment 17 would further clarify the private and multiple-use lands within the proposed park. Moss determined that all private lands within the new boundaries should be purchased. As for grazing rights, the senator proposed to:

allow holders of existing grazing permits to continue in the exercise thereof for up to 25 years, and beyond in the case of existing permittees or members of their immediate family; and [to include] a disclaimer as to the effect of the act on the rights of stockmen to trail their cattle and sheep in the park and to water them on lands within the park. [57]

The National Park Service responded to the bills sponsored by Moss, Bennett, and Burton by requesting amendments that would actually increase the 1969 expanded monument boundaries by another 23,500 acres. The reason for the increase, according to Interior Under Secretary Fred Russell, was to ensure that "the boundary encompass to the greatest extent possible the geological features of the area, and that the boundary follow natural lines of terrain." Russell added:

The proposed boundary is the result of a thorough study conducted over a period of 12 months. We believe it represents the optimum in terms of assuring continued preservation of the unique formations of the area. [58]

The National Park Service justified the new boundaries on the basis that Strike Valley, east of the Fold between Cedar Mesa and Halls Creek, is "an integral part of the geologic structure known as Waterpocket Fold, a monocline," and further argued:

The valley is a textbook example of a 'Strike Valley,' i.e. where the valley follows the strike of the geologic strata. Amendment No. 17 of S.531 would locate the boundary inside the valley where a county road [the Notom-Bullfrog Road] would cross and recross the boundary. Since the valley itself is a single geological and topographical unit, it ought to be interpreted, protected, and managed as a unit. [59]

The National Park Service boundaries would add 17,245 acres of former BLM lands, 1,278 acres in state-owned sections, and 4,347 acres of Fishlake National Forest in the vicinity of upper Deep Creek.

The most important changes affecting management concerned grazing. The National Park Service believed Moss' more politically expedient and flexible 25-year phase-out would not guarantee adequate resource protection. The agency, instead, requested a strict, 10-year phase-out. The Washington office was thus supporting Heyder's field investigation and management finding that cattle grazing and resource protection were incompatible. Under Secretary Russell said:

We believe that continued grazing use is not compatible with optimum protection and interpretation of the park. There are approximately 60 permittees grazing several thousand animal-unit-months of cattle and sheep within the area. A major consideration in arriving at our recommended boundary was the elimination of grazing lands wherever feasible. The remaining lands are necessary for the protection and interpretation of the park, and we believe a 10-year phase-out of grazing would be appropriate. [60]

It was estimated that if the annual and term grazing permits issued before January 1969 were considered, termination dates under a 10-year phase-out plan would range from June 30, 1971 to June 30, 1978. This desire to phase out grazing as soon as possible became a cornerstone of Capitol Reef management philosophy from that point. The National Park Service-suggested amendments did include a proviso insuring the continued right to use stock driveways across park lands, so long as the Secretary of Interior could set guidelines for their use. [61]

As part of the legislative support data, the National Park Service also came up with staffing, budget, and development projections for the next five years. It was anticipated that personnel would grow from 11 FTE (full time equivalent persons per year) in 1970 to 23 FTE in 1975, of which 21 would be permanent. The key additions would include a GS-11 chief ranger, a GS-9 "maintenance superintendent," and additional clerical and seasonal help. [62]

Projected development outside the Fruita headquarters area called for a ranger station, primitive campground, picnic area, and road improvements in both and north and south districts. An additional three miles of road (from the top of the Burr Trail from Upper Muley Twist Canyon to Strike Valley Overlook) and 14 miles of trails were to be built in the southern part of the park. [63]

The entire package was estimated to increase Capitol Reef's budget from $450,000 in 1970 to $2.5 million in 1975. An additional $328,000 was earmarked to purchase the remaining inholdings, which now included the Sleeping Rainbow Guest Ranch, the Campbell section (encompassing the old Behunin Cabin), and the Capitol Reef Lodge property of Clair Bird. Needless to say, these projections were optimistic.

On June 24, 1970, Sen. Moss' bill, S. 531, was favorably reported out of committee and was passed smoothly by the whole Senate on July 2. Since this bill still called for the smaller additions and 25-year grazing phase-out, the National Park Service now focused on amending Burton's national park/national recreation area bill to create the 254,000-acre park with a 10- year phase-out. [64]

In September, the House Subcommittee on National Parks and Recreation of the Committee of Interior and Insular Affairs held hearings on Burton's H.R.17152 and Moss', S.531 which had already passed in the Senate. The subcommittee was chaired by Rep. Roy Taylor of North Carolina. Again, the hearing was poorly attended, with only San Juan County Commissioner Calvin Black, an outspoken critic of national park expansion in Utah, testifying in favor of Burton's multiple-use recreation area concept. Black did not mind giving Capitol Reef national park status so long as recreational development, such as the paving of the highway from Boulder to Bullfrog by way of the Burr Trail, and utility and grazing rights-of-way were guaranteed. According to Black, Burton's bill offered the best option for southern Utah. [65] When asked by Chairman Taylor if the local residents agreed with him, Black answered:

I have been to meetings in Moab and Escalante and all of these communities. I know this is virtually 100 percent [in agreement]. About the only people in our area that might disagree with this position are people who have moved in very recently and are strictly in the tourist business [and] have no other interest. [66]

The Washington hearings also enabled the conservation lobby to express its support for an expanded, single-use Capitol Reef National Park. George Anderson of the Friends of the Earth not only testified in favor of the 254,000-acre National Park Service proposal, but also suggested that the new name should be Waterpocket Fold National Park. Anderson believed that tourism would replace lost ranching income. He also expressed the common opinion of many national park expansion advocates that continued multiple-use of the park lands would "not only leave the Waterpocket Fold open to the kind of niggling deterioration and uncoordinated planning that [would] tear down a great resource, but it would also waste the opportunity to make this part of Utah famous." [67]

In a seeming contradiction, however, the Friends of the Earth legislative director also urged that compromises be pursued to ensure "ways of providing for grazing and other existing uses." Anderson argued that "none of these uses need interfere with establishing a great national park here." [68]

National Park Service Director George B. Hartzog, Jr., also testified at this hearing. He was joined at the witness table by Chief Ranger Bert Speed (even though Superintendent Wallace had now been at Capitol Reef for over a year) and Mike Lambe of the Washington office legislative division. Hartzog reiterated the National Park Service proposal outlined above. The director specifically recommended that the entire unit be administered as a national park, rather than splitting the southern end into a recreation area. This led to an interesting exchange between Hartzog and Rep. Wayne Aspinall. As full committee chairman, Aspinall carried considerable weight in determining the fate of this bill. Aspinall was particularly concerned about why Capitol Reef should be changed from a national monument to a national park:

Mr. Aspinall: After all, Mr. Director, under the present nomenclature, there is not very much difference between a national monument and a national park, is there?

Mr. Hartzog: No sir; there really is not....If there is one central, single feature, they have tended to make it a national monument. If there is variety, they have tended to make it a national park. At one point acreage was a significant distinction, but more recently, acreage has become blurred as a criterion.

Mr. Aspinall: But there is, because of the advertising that is put out by the National Park Service and also because of most of the news media, the idea that it is supposed to be a little more important to be a national park area than to be a national monument, is that not true, in the public's mind?

Mr. Hartzog: In the public's mind, I think that is what has developed. Actually, however, I think more and more, with the Congress' insistence on the quality of these national parks, it is becoming a real psychological distinction.

Mr. Aspinall: I think also the fact that we no longer are friendly toward the designation of areas under the Antiquities Act as national monument. I think that we are asking now to update all of these areas as soon as possible with statutory authority. I think this will bring us into a closer relationship as far as national park areas and national monument areas are concerned than we have had before. [69]

This exchange made it clear that not only was national park designation more favorable in the eyes of Congress and the public, but that monument creation was no longer such a viable alternative in creating additional National Park Service lands. Capitol Reef would be one of the last areas south of Alaska to be expanded through presidential proclamation. If it could withstand the controversy surrounding that expansion, Capitol Reef's future as a national park was all but assured.

Shortly after the November national elections, Aspinall went on an extended honeymoon, leaving instructions that no legislation was to pass in his absence. Meanwhile, Burton lost his attempt to dislodge Moss from his Senate seat. With Bennett's quiet departure from the issue, only Moss was left to carry on the struggle for a Capitol Reef National Park into the next session. [70]

Congressional Debate And Park Creation,

1971

In early January 1971, Sen. Moss reintroduced his bills to create Capitol Reef and Arches National Parks. When introduced, S.29, "a bill to establish the Capitol Reef National Park in the State of Utah," was almost identical to the S.531 that had died in the previous Senate. [71] The only difference was a new shaping of the eastern boundary in the southern portion of the park to conform to the natural cliff line east of the Waterpocket Fold. This idea had been proposed by the National Park Service the year before. This boundary would add about 11,000 acres to Moss' previous bill, but would still be approximately 12,000 acres smaller than the expanded monument or the National Park Service proposal. [72]

Moss was not only concerned with Capitol Reef and Arches. During the same session he also sponsored bills to create a Canyon Country Parkway, give statutory authorization to Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, and to add 80,000 acres to Canyonlands National Park. All this congressional focus on southern Utah must have kept National Park Service officials very busy. Meanwhile, at Capitol Reef, additional resource data were gathered and management concerns were refined.

In an advisory Environmental Statement for Capitol Reef National Park first drafted in May 1971, Southern Utah Group Superintendent Karl Gilbert focused on resource descriptions, impacts, and alternative considerations. This document was apparently used in-house to draft the legislative support data for the 1971 congressional hearings, since many of the same ideas can be found in both. [73]

Issues affecting the new park included the following:

An anticipated doubling of the 226,000 visitors in 1970 was predicted due to the completion of Interstate 70 and Utah 95 from Hanksville to Blanding. Increased visitation was seen as a potential problem if not properly controlled through management and "sound design of facilities."

Beneficial environmental effects would occur as grazing was phased out. It was also believed that "well-defined regulations" drawn up by the National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management (which would continue to administer the grazing permits) would guarantee a "realistic carrying capacity."

Existing mining claims were seen as a "definite environmental factor." It was hoped that acquisition and cancellation of claims would be started as soon as possible. Access to claims would be strictly controlled and reclamation of old sites would begin as soon as possible.

Private lands were to be purchased from willing sellers, or acquired by condemnation "should adverse and damaging use develop."

It was believed that national park designation would insure environmental protection. Management activities would be "geared towards the return of natural conditions." Once grazing and mining were eliminated, bighorn sheep and pronghorn antelope could be reintroduced into the park. Other wildlife species were expected to "increase to a natural carrying capacity."

In summary, the Environmental Statement reported that ending short-term, multiple-use would gradually give way to long term benefits. The statement argued:

Marginal grazing and equally marginal mining activity in the recently added lands must be considered as existing local short-term uses. Both must be considered as noncompatible (sic) with national park purposes. It is believed that the long-range benefits–cultural, economical and sociological–normally associated with a full-fledged national park will far exceed those resulting from the local short-term uses. In addition to improved environmental considerations, the long-range impact of the proposed area, with the predicted visitor traffic, could well be the major source of adjacent area economy in the future. [74]

Thus, the National Park Service was beginning to realize the tremendous resources and complex management issues facing the proposed Capitol Reef National Park. Notably, however, there is very little said in any of the legislative support documents about possible adverse economic and political reactions to a 10-year phase-out of grazing. Without doubt, the absence of multiple-use practices was going to improve the natural environment of the park. Yet, the question of how to improve local relations, severely damaged over the last two years, was not even addressed. It was evidently assumed that an eventual tourist boom would ease the distress of local residents.

By mid-1971, opposition to an expanded Capitol Reef was no longer read in newspapers or heard on the floor of Congress. Residents may have continued to complain among themselves, but for the most part had resigned themselves to the inevitable expansion. The one benefit seen by neighboring communities was that it also appeared Capitol Reef would finally become a national park, a goal sought by local boosters since the 1920s.

The Senate hearings in 1971 drew little opposition; most of the time was spent refining the bill. [75] On June 22, in less than a minute each, the Senate passed all four of the Moss bills concerning southern Utah. [76]

At the same time, newly elected Democratic Rep. Gunn Mackay, who replaced Burton, introduced similar legislation (H.9053) in the House. The hearings in the lower chamber were equally quiet. Calvin Black was back to testify against the bill, but even he realized that he was just "one voice crying in the wilderness." [77] In early October, the House passed its version of the bill, with even Aspinall speaking in favor. [78]

In November, a conference committee convened to iron out differences between the House and Senate versions. The final wording and disagreements were easily worked out and a favorable report sent back to both chambers. The compromises worked out in the conference committee both concurred and dissented with National Park Service recommendations. Because of the importance of the final wording of the bill, it is necessary to examine the difference between the House and Senate versions and the reasons for the bill's final language. [79]

1) The boundaries were identical in both the Senate and House bills. The National Park Service calculation of 241,671 acres was now being used exclusively.

2) With regard to the important issue of grazing, the Senate version supported Moss' desire for a 25-year or longer phase-out, whereas the House version limited grazing privileges "to the term of the lease, permit, or license, and one period of renewal thereafter." [80] Because the House version was identical to Canyonlands National Park's enabling legislation, the conference committee voted to use it instead of the more flexible 25-year plan. Since the final wording was much closer to the National Park Service desire for a 10-year phase-out than was the Moss plan, agency officials must have been pleased.

3) The House and Senate versions both included provisions for stock driveways, but the House wording was accepted because it permitted the Secretary of Interior to designate the trailway locations. An additional amendment was included by the conference committee that "assured the recognition of traditional trailways across the park by the Secretary, but, at the same time, to allow him to establish reasonable regulations for their use." [81]

4) The Conference Committee decided to go along with the House and delete the Senate wording dealing with "proper development of the park" on the grounds that there was already ample authority for this, so the statement was not needed.

5) Both the Senate and House bills had a section dealing with easements and rights-of-way. In recognizing the need for utility rights-of-way across such a large, elongated park, the conference committee proposed to compromise the two versions and require the granting of easements and rights-of-way unless "the route of such easements and rights-of-way would have significant adverse effects on the administration of the park." [82]

6) Both Senate and House bills called for wilderness investigations on the new park lands, but the House version was accepted because it more closely resembled wording in "other comparable measures."

7) The Senate and House versions equally addressed the need for a transportation study. The final wording of the bill stated that the study would include "proposed road alignments within and adjacent to the park. Such study shall consider what roads are appropriate and necessary for full utilization of the area." [83] This study was most likely included to address local and state worries that the national park would not develop access to the outlying areas.

8) The last difference involved the appropriation of money needed for private land purchases and development costs. The House amendment was chosen because it specifically limited the authorized amounts to $423,000 for immediate purchase of private lands and $1,052,700 for development of the new national park. [84]

In summary, the conference committee favored the House version of the Capitol Reef National Park bill because it was more specific and more in line with the requirements of other southern Utah parks.

The House of Representatives passed S.29 with the conference committee changes on December 7, and the Senate passed the bill on December 9. It was now up to President Richard Nixon to sign the enabling legislation for Capitol Reef National Park into law.

The Department of the Interior recommended the bill be signed. In correspondence with George Shultz, then director of the Office of Management and Budget, Assistant Interior Secretary Nathaniel Reed pointed out that there were some significant differences between S.29, as passed by the Senate and House, and the National Park Service proposal. The agency, however, would have little trouble living with the changes. The money approved was consistent with park service figures and the road and wilderness studies would, most likely, not cause financial hardship. The decrease of approximately 12,000 acres from the National Park Service plan was not seen as a major problem. [85]

The only major concerns were with grazing and rights-of-way. According to Assistant Secretary Reed, stipulations permitting rights-of-way that did not inflict "significant adverse effects on the administration of the park" were not enough of a safeguard. The "adverse effects" qualifier would be interpreted as broadly as possible to protect the park's resources.

Insofar as grazing was concerned, the National Park Service had argued for a 10-year phase-out plan throughout legislative battle. While the one-time renewal was not what the agency requested, it had to be more pleased with this alternative than with the 25-year or greater period proposed under the Senate bill.

In short, the bill did not concur entirely with the National Park Service plans for Capitol Reef, but it was close enough to recommend passage. After all, a new, 242,000-acre national park had to be a more pleasant alternative than a return to 39,000 acres or a split national park and recreation area. With the able assistance of Sen. Moss and newly elected Rep. Mackay, the National Park Service and Capitol Reef supporters had finally succeeded in creating an expanded Capitol Reef National Park, just as Stewart Udall had envisioned back in December 1968.

President Nixon signed the Capitol Reef National Park bill into law on December 18, 1971. [86] The park supporters had prevailed over the multiple-use advocates--for the time being. Now the question was, could Capitol Reef management develop and protect its newly-gained resources in the manner befitting a true "crown jewel" like Yellowstone, Yosemite, or Zion National Parks?

Summary and Conclusions

Capitol Reef National Park protects one of the most spectacular physical barriers in the world. Its first human explorers, whether of American Indian or European descent, must have been in awe of the beautiful, twisted landscape. Later, Mormon farmers and ranchers would become economically dependent on the isolated, mostly unregulated public lands that surrounded their small communities.

When early boosters sought national park status for Wayne Wonderland, their goal was not so much resource protection as further economic development through roads and tourism. At the same time, the National Park Service was looking at expanding its influence and services into the scenic Southwest. The movement to establish Capitol Reef National Monument thus served the interests of both local businessmen and the fledgling environmental movement, but for different reasons.

After its establishment in 1937, continued isolation and the outbreak of war meant that Capitol Reef was virtually ignored for the next 20 years. The wealthy tourists and writers who visited the more accessible national parks did not come to Capitol Reef. Instead, the vast majority of visitors to Capitol Reef National Monument were Utah residents who, while still enjoying the scenery, usually viewed the monument from the perspective of traditional, multiple- resource use. This point of view was, and still is, in sharp contrast to the National Park Service mission to provide for aesthetic enjoyment and resource preservation.

Beginning with grazing and mining conflicts, and continuing through the road construction and other monument developments funded by Mission 66 appropriations, these different land-use philosophies became glaringly apparent. During and after each conflict, the barriers of culture and attitude would continue to hinder constructive dialogue and understanding. It was as if the two sides were traveling different roads and, coming to a crossroads, collided--instead of looking to see where the other side was coming from.

The controversy over the 1969 monument expansion and eventual creation of Capitol Reef National Park in December 1971 was the biggest, loudest collision of all. The barriers that had prevented understanding and fueled prior conflicts were exposed for all the rest of the country to see. Again, compromises were made that quieted local opposition to National Park Service management policy, but only for a limited time.

Future conflict is inevitable when land is claimed by both environmentalists and multiple-use advocates. If the next confrontation concerning Capitol Reef National Park is to be handled constructively, National Park Service managers must be willing to understand not only the history of the area, but the perspectives of those who made that history. It is crucial that managers, local residents, and preservationists anticipate and welcome a crossroads where all parties can sit down, listen, and see where the other sides are coming from.

Footnotes

1 Presidential Proclamation, "Enlarging the Capitol Reef National Monument, Utah," Proclamation #3888, Federal Register, 34, No. 14, 22 January 1969:907.

2 Enlargement Press Release, December 1968, Box 2, Folder 5, Capitol Reef National Park Archives.

3 Capitol Reef National Park Map 158-2001-B, May 1969, National Park Service, Denver Service Center, Technical Information Center, Denver (hereafter referred to as TIC).

4 "Authorized Uses of Public Lands Recently added to Capitol Reef National Monument," Folder 33, Administrative Collection, Arches National Park Archives.

6 Robert Heyder, interview with Brad Frye, tape recording, 1 November 1993.

7 Heyder to Speed, May 1969, Box 2, Folder 5, Capitol Reef National Park Archives.

8 Richfield Reaper, 23 January 1969.

10 Salt Lake Tribune, 24 January 1969.

11 Congressional Record, 91st Congress, 1st session, 1969, 115, Pt. 1:1019.

12 Bennett to Udall, 9 December 1968, Series 1E, Carton 3, Folder 2, Wallace F. Bennett Collection, MSS 20, Special Collections, Brigham Young University Library (hereafter referred to as Bennett Collection MSS 20).

13 Salt Lake Tribune, 18 January 1969.

15 Congressional Record, 115, Pt. 1:139.

18 Bennett to Charles Hansen and Others, 5 February 1969, Series 1E-Carton 3, Folder 2, Bennett Collection, MSS 20.

19 Congressional Record, 91st Congress, 1st session, 1969, 115, Pt. 3:3118.

20 Daily Sentinel, Grand Junction, Colorado, 11 February 1969.

24 Ogden Standard-Examiner, 12 February 1969.

25 Richfield Reaper, 27 February 1969.

27 Meeting on Enlargement of Arches and Capitol Reef National Monuments Held in Office of Senator Frank Moss, Salt Lake City, 19 February, Folder 33, Administration Collection, Arches National Park Archives.

28 Congressional Record, 115, Pt. 5:6572-6573.

29 Salt Lake Tribune, 13 February 1969.

30 Congressional Record, 115, Pt. 8:11084.

31 Salt Lake Tribune, 15 May 1969.

32 The Daily Sentinel, 13 May 1969.

33 Heyder to Regional Director, 14 October 1968, File 6435a, Accession 79-76A-1229, Container #790695, Records of the National Park Service, Record Group 79 (RG 79), National Archives - Rocky Mountain Region, Denver (hereafter referred to as NA-Denver).

34 Gilbert to Area Superintendents, 25 March 1969, and Regional Director to Director, 2 November 1968, File 6435, 79-73A-136, Container #790695, RG 79, NA-Denver.

35 The Southern Utah Group office was abandoned on 4 August 1972, according to the Records Transmittal for Accession 79-73A-136, RG 79, NA-Denver.

36 Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Subcommittee on Parks and Recreation, "Hearing on S. 531 and S. 532." 91st Congress, 1st session, 15 May 1969, Statement #3, Box 2, Folder 6, Capitol Reef National Park Archives (published hearing report not included). The hearings dealt with both Arches and Capitol Reef, but the focus of this discussion is on the latter.

39 Senate Subcommittee, Salt Lake Hearings, May 15, 1969, Index, Ibid.

40 Statement of Don Pace, Hearings Statement #15, 3, Ibid.

43 Statement of Wilda Gene Hatch, Statement #11, Ibid., 1.

45 House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, "Withdrawal of Public Lands by Presidential Proclamation for the Expansion of Capitol Reef National Monument," and HR 17152 and S. 531, "Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Public Lands," 91st Congress, 1970, 1.

51 Heyder to Regional Director, 14 March 1969, File D18, 79-73A-136, Box 3, Container #790697, RG 79, NA-Denver; Heyder interview.

52 "Capitol Reef National Monument, Management Objectives," March 1969, Ibid.

55 Thow, "Capitol Reef: The Forgotten National Park," (M.A. Thesis, Utah State University, 1986) 132; Capitol Reef Map 258-91,000, March 1979, Drawer 11, Folder 1, Capitol Reef National Park Archives (also in TIC).

56 Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, "Hearings on S. 531 to Establish the Capitol Reef Park," 91st Congress, 2nd session, 28 May 1970.

57 Under Secretary Fred Russell to Chairman Henry Jackson, 27 May 1970, File W3815 (69-71), 79-73A-136, Box 4, Container #790698, RG 79, NA-Denver.

58 Senate Committee, Capitol Reef National Park, 3.

61 Senate Committee, Capitol Reef National Park, 5.

62 William L. Bowen, Director, Western Service Center, to National Park Service Director, Attn.: Assistant Director, Legislation, 24 April 1970, File D18, 79-73A-136, Box 3, Container #790697, RG 79, NA-Denver.

64 House Subcommittee Hearings, Expansion of Capitol Reef, 1970, 87; Thow, 137.

65 House,Subcommittee Hearings, Expansion of Capitol Reef, 1970, 92-93.

71 U.S. Congress, Senate, Sen. Moss speaking for S.29 and S.30, Congressional Record, 92nd Congress, 1st Session, 117, Pt. 1:333.

72 Different acreage figures are found in a variety of sources. Moss estimated that his January 1971 proposal would be 242,472 acres, as specified on Map #158-91,002, January 1971, TIC. This, incidentally, is the map that is referred to in the final act, Public Law 92-207, which created the present Capitol Reef National Park. The National Park Service estimated this same area to be 241,671 acres--a figure used in several 1970s-era planning documents. In the "1989 Statement for Management," the acreage had been revised to 241,904.26 acres (Superintendent's Files, Capitol Reef National Park). Presumably, this figure is correct and was adjusted during a 1980s boundary survey, as there have been no additions or deletions since 1971.

73 "Environmental Statement for Capitol Reef National Monument," draft dated 25 May 1971, Superintendent's Files, H1415. The final draft, undated, is in Box 2, Folder 2, Capitol Reef National Park Archives.

75 U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Hearings on S.29 to Establish Capitol Reef National Park, 92nd Congress, 1st session, 3 June 1971.

77 U.S. Congress, House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Hearings on H.R. 9053 to Establish the Arches National Park and Capitol Reef National Park, to Revise the Boundaries of the Canyonlands National Park, and for Future Purposes, 92nd Congress, 1st session, 14-15 June 1971, 56; Thow, 138-139.

78 U.S. Congress, House Debate Over H.R.8213, Congressional Record, 92nd Congress, 1st session, 1971, 117, Pt. 26:34790.

79 House, Joint Statement of the Committee of Conference, 92nd Congress, 1st session, Report 92-685, 30 November 1971, 1-4; Congressional Record, 92nd Congress, 1st session, 1971, 117, Pt. 33:43360-61. The conference committee report is also in Box 2, Folder 1, Capitol Reef National Park Archives.

80 The conference committee report is the basis for all information; the quote is from Capitol Reef National Park's enabling legislation, Public Law 92-207, 92nd Congress, 1st session, 18 December 1971.

81 House Committee of Conference Report, House Report #92-605, 4.

84 Ibid.; Committee of Conference Report, 5.

85 Nathanial Reed to George Shultz, 14 December 1971, Box 2, Folder 1, Capitol Reef National Park Archives.

86 P.L. 92-207, U.S. Statutes at Large 85 (1971): 739-740.