|

Capitol Reef

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 10:

PARK, WILDERNESS AND MONUMENT EXPANSION PROPOSALS, 1961-1969

On January 20, 1969, as his last official act as president, Lyndon Johnson signed a proclamation expanding Capitol Reef's boundary by six times its previous size. This presidential proclamation and the subsequent reactions to it had a more profound effect on Capitol Reef National Park than any previous event. Not even the creation of the national monument in 1937 or the changes made during Mission 66 compare to the effects of the 1969 expansion on Capitol Reef management, resources, and its relationship with the local community.

Hints of change were in the air as early as 1961, when the first legislation was introduced in Congress to create a Capitol Reef National Park. At the same time, there was a growing movement to protect what wilderness remained in the national parks and forests. At the wilderness hearings for Capitol Reef, the recurring animosities between local preferences and National Park Service planning emerged once again.

By the end of 1968, Washington politics decided Capitol Reef's fate. High officials in the Department of the Interior believed that the incoming Republican administration would not be as willing to expand the national parks as were the outgoing Democrats. Before leaving his Cabinet post, Secretary of the Interior Udall proposed a sweeping plan to create and expand parks and monuments in Alaska and the Southwest. Capitol Reef National Monument was among those listed. While debate and compromise in Washington whittled down the list, Capitol Reef's management was kept guessing and the local communities were left out of the decision-making process. From an initial proposal of seven new or expanded national monuments comprising over seven million acres, only four areas totaling 300,000 acres made President Johnson's final cut: one of these was Capitol Reef. The tremendous acreage added to Capitol Reef National Monument made it the largest unit of the National Park Service in Utah.

The resulting outcry from neighboring residents, ranchers, miners, and politicians was both furious and predictable. The final solution devised by Utah's congressional delegation was to make both Capitol Reef and Arches into national parks. Yet, even this legislation had its own troubled history before finally passing in late 1971.

On December 18, 1971, Capitol Reef National Park was created with the same boundaries as exist in the mid-1990s. Its new size and designation would help protect some of the Colorado Plateau's most outstanding sculpted sandstone scenery and high desert resources. Yet, most of the beautiful, sparse lands protected in this new park had been used by ranchers and miners for almost a century before its incorporation into the national park system. Park management would now be forced to balance traditional multiple resource use with resource protection and rehabilitation.

This chapter details events that led to the 1969 expansion proclamation. The ensuing controversy and legislation is covered in Chapter 11. What follows in the next two chapters is an analysis of the events and debates that impacted the creation and present management of this national park. Unfortunately, many of the primary documents relating to the period 1967-1972 are missing. The original documents that have been found are supplemented by oral interviews, congressional testimony, secondary sources, and newspaper articles.

Early Legislative Efforts

There is no record of any congressional legislation or resolutions passed before 1961 that specifically mention Capitol Reef. While Utah senators and congressmen supported local efforts both to create and improve Capitol Reef, they never seem to have vocalized that support in the House or Senate chambers. [1]

In 1961, Capitol Reef National Monument was undergoing significant change. The new paved highway through the monument was about to be constructed and Mission 66 plans were calling for over $2 million in new staff and facilities to accommodate the increasing number of visitors. Capitol Reef was no longer the quiet little national monument it once was. [2]

Republican Sen. Wallace Bennett set out to help the tourism boom in southern Utah by upgrading several national monuments to national park status. In 1961, 1963, and 1965, Bennett introduced bills to create Arches, Capitol Reef, and Cedar Breaks National Parks within their existing national monument boundaries. Bennett argued:

[I]n spite of the inspiring grandeur of these three national monuments, the number of people who visit them is relatively small. While the nearby Grand Canyon National Park received 1,187,000 visitors in 1960, only 102,000 visited Capitol Reef, 115,800 visited Cedar Breaks, and 71,600 visited Arches. A principal reason for the relatively small number of visitors is, I am sure, that fact that they have not received national park designation. Their present national monument status does not carry with it in the public mind the prestige associated with national parks. Such recognition is not only deserved, but long overdue. [3]

Sen. Bennett had also introduced bills to upgrade Rainbow Bridge to national park status and create a Canyonlands National Park straddling the confluence of the Green and Colorado Rivers. He sponsored yet another bill to construct a National Park Service Parkway connecting many of these scenic areas of southern Utah. [4] Except for the Canyonlands bill, which was significantly altered by Democratic Utah Sen. Frank Moss before passage, Bennett's proposals never made it out of committee, primarily due to unfavorable reports from the National Park Service.

The National Park Service's Mission 66 plans for southwestern parks were focused on upgrading existing facilities rather than changing names or status. Agency officials, therefore, requested that Bennett's bill changing Capitol Reef from a monument to a park be postponed indefinitely. In an advisory letter to Clinton P. Anders, chairman of the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Assistant Interior Secretary John Carr wrote:

The Capitol Reef National Monument is...one of several national monuments in this area earmarked for study to determine whether they merit status as national parks. When the results of a study of the Capitol Reef National Monument is completed, the Department will formulate recommendations covering the feasibility and desirability of according national park status. [5]

Since national park status possibilities were never mentioned in Capitol Reef master or wilderness plans during the 1960s, it is likely that the study mentioned by Carr never went very far.

When Bennett reintroduced his park bills during the next Congress in 1963, his Republican ally, Rep. Lawrence Burton, sponsored a similar bill in the House. Bennett noted, "More than sufficient time has elapsed for the Department [of Interior] to conclude its studies and I am hopeful that without further delay it will bestow its full approval upon the elevation in status which Capitol Reef so richly merits." [6"]

It is hard to know exactly how much effort Bennett and Burton put into these early attempts to get national park status for Capitol Reef. The chances that these bills would even make it out of committee would have been slim, since Bennett and Burton were working in a Democrat-controlled Congress. It is also likely that debate over the Canyonlands National Park bills and interest over the rapidly filling Lake Powell, which was anticipated to be the real tourist draw in southern Utah, may have consumed congressional attention for the next few years. Once again, Capitol Reef was left alone to concentrate on Mission 66 improvements and growing visitation within the confines of the old national monument. [7]

1967 Wilderness Proposal

Throughout the early 1960s, the National Park Service continued to invest millions of dollars in roads and facilities. The upgrades, especially in previously unsupported areas such as Capitol Reef, were badly needed. Yet, environmental organizations and some members of Congress worried that Mission 66 was going too far, that park integrity and preservation values were being sacrificed to accommodate increasing tourism.

The debate pendulum between accessibility and preservation had been swinging preservation's way ever since the 1956 defeat of the Echo Canyon Dam in Dinosaur National Monument. Now, with Mission 66 plans in many parks threatening newly emphasized wilderness, environmentalists urged the National Park Service to designate roadless areas like those proposed in national forests. [8]

The strength of the environmental movement was exemplified by passage of the National Wilderness Preservation System, or Wilderness Act of 1964, as it is commonly called. This law required federal land management agencies, including the National Park Service, to study, offer hearings, and recommend to Congress specific areas within their control to be designated wilderness, thus protecting them in a wild, undeveloped condition. Each addition to the wilderness system, whether it be under U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, or National Park Service control, had to adhere to Wilderness Act requirements and be individually approved by an act of Congress. [9]

Not all National Park Service officials were enthusiastic about the Wilderness Act. Many felt that wilderness within a national park or monument was already insured protection, unlike the multiple-use lands managed by other federal agencies. Of greater concern, however, was the threat to the service's autonomy in determining long-range policy. Wilderness designation would not only affect how park lands were managed, but could very likely restrict future road and facility expansion just when development possibilities seemed limitless. [10]

The initial wilderness proposals and hearings for many of the national parks were conducted during a period of heightened environmental awareness and controversy. The controversy, for the most part, focused on proposals to build a dam within what was then Grand Canyon National Monument. This volatile issue, together with the environmental movement's nearly-perfected strategy of letter-writing campaigns, saw the National Park Service diluged with waves of letters supporting the maximum amount of wilderness possible. Local protests were drowned in this sea of wilderness support.

It was in this context that Capitol Reef National Monument conducted its own wilderness hearings in December 1967. The preliminary proposal, which was drafted in September, called for five separate units totaling 23,074 acres out of a possible maximum of 30,150 roadless acres (Fig. 26). Monument lands not designated wilderness included:

|

| Figure 26. 1967 Wilderness proposal, Capitol Reef National Monument. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

1) the areas west and south of Chimney Rock and west of the old highway down to Capitol Gorge;

2) the developed headquarters and remaining inholdings at Fruita;

3) the Fremont River canyon, with its state highway and public utilities corridors;

4) the old highway corridor to Capitol Gorge and its spurs into Grand Wash and Pleasant Creek; and

5) a 1/8-mile buffer around the entire monument, considered the minimum necessary for management needs, including fencing of the monument. [11]

The largest of the proposed wilderness units was that area, almost devoid of human footprints, north of Utah Highway 24 to the north monument boundary. The other units, south of the Fremont River, were divided by the designated stock driveways through Grand Wash, Capitol Gorge, and Pleasant Creek. Like the northern district, these southern units were also classic wilderness, with rugged, virtually impenetrable desert slickrock cliffs, canyons, and domes. [12]

Looking back at events years later, Capitol Reef Superintendent Robert C. Heyder observed that the wilderness designation would "not have changed the operation of the park at all." The areas under consideration were backcountry and would always be treated as backcountry. From a management perspective, formal wilderness might have "helped to zone, put tighter constraints on the planners if they wanted to build something," said Heyder, "and I certainly [saw] nothing wrong with that." [13]

Regardless of the minimal effects the wilderness plan would have on Capitol Reef management, the National Park Service proposal was attacked from two sides. First, the environmental organizations wanted the buffer zones and stock driveways included in two large wilderness units. Second, local residents and traditional multiple-use advocates were afraid that customary use would be further inhibited and/or that stock driveways would be blocked. Most of those who favored additional wilderness responded by letter, whereas those opposed to any wilderness showed up at the public hearing on December 12, 1967 at the Wayne County Courthouse in Loa.

According to Heyder, the two-and-a-half-hour meeting was attended by 42 people. The presiding officer was John C. Preston, with Assistant Regional Director George Miller, from Santa Fe, presenting the National Park Service proposal. [14] After outlining the initial plan, Miller and Heyder listened as ranchers and local politicians voiced their opposition. Limitations on access and development were the chief concerns raised by local residents. Hugh King, president of the Wayne County Farm Bureau, perhaps expressed local misgivings the best when he stated:

They are locking it up for a few naturalists....[T]he Park, I believe, is adequate in protecting our resources and things and I don't think we need to lock these resources from any further development. The great problem in my county and our country has been decrease in population. [We need] labor and things to keep our young people here and this park has furnished a lot of work and we appreciate that. [15]

Clearly, King wanted development in the monument to continue providing employment for local residents so they wouldn't have to move to the city. De Von Taylor, president of the Wayne County Cattlemen's Association, also expressed the need for multiple-use of monument resources by area residents when he stated:

We feel the present state of Capitol Reef is in the best interest of the people of this area and no more restrictions should be placed on these lands. But we feel that the public lands should be placed more for multiple-use and for the benefit of these people in this area. [16]

This argument, so common in the rural West, was countered by the increasing number of recreational users of the land who saw the value in preserving what remained of "America's wilderness heritage." Members of the Wilderness Society were urged to attend the hearing or write in favor of wilderness that would "provide a setting of remoteness and offer the experience of true solitude to all who visit them." [17] The Wilderness Society position, of course, was to eliminate the buffer around the monument boundary because "otherwise, new incursions will result in steadily decreasing wilderness." [18] Since the National Park Service had proposed this buffer zone in other proposed wilderness areas, this philosophical argument over wilderness boundary interpretations was not specific to Capitol Reef.

The hottest debate over Capitol Reef's wilderness plan concerned the stock driveways. The National Park Service plan called for the stock driveways to continue because they are mandated by the presidential proclamations establishing the monument in 1937 and expanding it in 1958. Wilderness advocates recognized these driveways as well, but felt that they could be included in designated wilderness areas since "grazing is recognized as a conforming use of wilderness in the provisions of the Wilderness Act." [19]

Local ranchers who used the driveways through the canyons to move their livestock between summer ranges in the western high plateaus to winter ranges east of the monument were, naturally, concerned about the impact that wilderness designation could have on their customary use of the land. The National Park Service plans recognized these fears by excluding those canyons from wilderness designation, thereby separating the various wilderness units. Despite objections from the flood of letters supporting the Wilderness Society position, the agency did not change these plans. [20]

After the hearings, National Park Service correspondence indicates, attempts were made to eliminate livestock drives from some of the canyons to placate the environmentalist majority. Superintendent Heyder, however, opposed that move, arguing:

[I]f we do, it will mean a complete reversal of our reasoning given at the Wilderness Hearing at Loa, Utah on December 12. At that time we made the point that the proposed wilderness designation would in no way affect the present stock driveway arrangement. [21]

Heyder's recommendations were endorsed by Regional Director Frank Kowski: the driveways would be retained. The National Park Service omitted the canyon corridors from the wilderness plan, not because of the perceived incompatibility of grazing with wilderness, but because the agency, and particularly Superintendent Heyder, recognized local objections to infringement on customary use. [22]

The 1967 Capitol Reef wilderness corridor proposal was never formally presented to Congress. As a matter of fact, the creation of wilderness areas throughout the national park system has never been as extensive as advocates hoped. [23] Once again, Capitol Reef managers were faced with balancing local customs and traditional use with resource protection. In this case, local desires to exempt the stock driveways from wilderness designation were incorporated into the wilderness plan, despite pressure from the growing environmental movement throughout the rest of the country.

The Genesis Of Expansion, 1968

Democrat Lyndon Johnson had one of the most successful conservation records of any president in history. Between 1964 and early 1969, 44 new, mostly historic areas were added to the National Park Service system, more than during any other, single president's term. As part of his Great Society, 4.8 million acres of national recreation areas such as Delaware Water Gap, Indiana Dunes, and Wolf Trap were established to benefit inner- city populations. More controversial national parks such as Redwood and North Cascades were also created during Johnson's administration; and far-reaching environmental bills such as the Wilderness Act, Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965, National Trail Systems Act, and the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act were also signed into law. [24]

Though Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird, regarded themselves as nature-lovers and personally supported these conservation measures, much credit for this tremendous record is due Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, National Park Service Director George B. Hartzog, Jr., and an American public and Congress filled with new-found environmental pride. Udall and Johnson had a good working relationship: Udall was the director, orchestrating the bills through planning and committees, while Johnson was the producer, using his manipulative strengths to insure final passage. [25]

In March 1968, Johnson surprised the nation with his decision not to seek a second term of office. Udall, who had begun as interior secretary under John F. Kennedy in 1961, would step aside when the new administration, whether it be Republican or Democrat, took office the following January. [26]

The National Park Service had never been in such a strong position as it was in the summer of 1968. Visitation was at an all-time high and Mission 66 had all but accomplished its goals of improving the park infrastructure, organization, and interpretive abilities. Resource management was being funded as never before, in large part due to the 1963 Leopold Report, which had proclaimed that "[a] national park should represent a vignette of primitive America." And, thanks to the increasing power of the environmental lobby, further expansion of the national park system was regarded by Udall and others as inevitable. [27]

It was in this setting that Secretary Udall proposed to President Johnson an outgoing gift of new and expanded national park lands for the American people. Udall was very aware that other presidents--of both parties--had used the 1906 Antiquities Act to proclaim new national monuments during their last days in office. Udall believed that, since Johnson's administration had been so environmentally successful, its gift should be the largest of all. [28]

Udall's original proposal in July 1968 was meant to probe Johnson's receptiveness to the idea. In his memorandum to the president, Udall hoped that,

[a]s a parting gift to future generations...before [Johnson left] office, [he would] consider using executive power in the tradition of the Roosevelt presidents to reserve and preserve unique lands already owned by the American people for future generations. [29]

Udall, warned, however, that such use of the Antiquities Act would meet some congressional opposition, but added that "adroit maneuvering" and national conservation organization support would "mollify enough congressional leaders so that your plans will not be upset by subsequent congressional action." Udall asked to be allowed to prepare "several proposals...involving significant additions to the permanent national estate." This simple request would lead to a confrontation between the president and his interior secretary that would forever tarnish their close partnership. [30]

With Johnson's approval, Udall went ahead with plans to study potential sites. He called in the National Park Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service directors, telling them to field their personnel and get recommendations to him by September. Udall later recalled:

[Hartzog] and the Director of Sports, Fish and Wildlife recommended some very large areas. I had to cut back their recommendations because I didn't want to rile Congress too much. On the other hand I wanted some big, significant things. [31]

The most logical places to look for "significant" additions to the National Park Service were in those parts of the country with large tracts of unoccupied federal land. The national forests, due to previous conflicts, were not considered. Thus, Bureau of Land Management public domain was an obvious target for National Park Service expansion.

Most of these lands were in Alaska; the rest were in the desert Southwest. Arizona, Udall's home state, held likely properties, as did Nevada and Utah. Several existing national monuments in Utah were surrounded by BLM lands, making them prime candidates for consideration. Of the 17 areas originally considered, the list was whittled down to the seven most promising, encompassing a proposed seven million additional acres for the National Park Service. [32]

There is no known documentation pinpointing when Capitol Reef was first considered as a part of Udall's proposed expansions. In August, Secretary Udall visited Canyonlands National Park and requested "proposals on boundary changes which might be desirable in the Canyonlands Colorado River Escalante country." [33] Arches National Monument sent in its proposed extensions at the end of August, but it is not known when Capitol Reef's changes were delivered. [34] The first that Capitol Reef Superintendent Heyder heard about proposals to expand his monument was at the dedication of Carl Hayden Visitor Center overlooking the Glen Canyon Dam on September 26, 1968. [35]

Heyder was only 37 years old, but had been in the National Park Service since his youth at Yosemite and Grand Canyon National Parks. Most recently, he had served as management assistant at Wilson's Creek National Battlefield in Missouri. His long career would see Heyder assume the superintendency of Bryce Canyon, Zion, and Mesa Verde National Parks before his retirement in 1993. He had been at Capitol Reef National Monument for only about a year when he was invited to hear Secretary Udall speak at the Hayden Visitor Center dedication. During the pre-ceremony gatherings, Regional Director Frank Kowski asked Heyder if he were aware that the park service was considering enlarging Capitol Reef National Monument. [36]

When Heyder said he knew nothing about this, Kowski explained that under consideration was a separate monument unit encompassing a portion of the Waterpocket south of Oak Creek to just above the Burr Trail. The stock driveway, water diversion, and irrigation dam in the drainage may have been why Bates Wilson and/or other field office personnel decided to exclude Oak Creek itself, and not connect this new unit directly to the southern boundary of the monument. [37]

When Heyder heard about this initial expansion idea from Kowski, he immediately pointed out that such a small additional unit was not enough. Heyder argued that any new boundary must be extended to insure protection of existing monument resources. Heyder also recommended that the entire Waterpocket Fold, from the Fishlake National Forest boundary in the north to the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area boundary in the south, be included in the expansion. Heyder later recalled that the regional director seemed surprised by these ideas, and promised to talk to him further after the dedication ceremony. [38]

After the dedication speeches by Udall and others, Kowski introduced Heyder to Secretary Udall. This was the first interior secretary Heyder had ever met and the meeting would prove to be particularly memorable. According to Heyder, Udall asked him, "Oh, what do you think about this idea of widening [the monument]?" Heyder responded that he didn't think the expansion was being done right. When the secretary asked what Heyder would do, the superintendent spoke up:

[Y]ou ought to go west of the main body [of the existing monument] and east a bit and take in Cathedral Valley up there and come off the [Thousand Lake] mountain and come all the way to the forest, you know, and take that whole thing in and then go all the way down to the recreation area. [39]

Udall responded favorably to Heyder's suggestions. Heyder recalled, "He said, 'You get with Bates the next couple of days and come up with something.'" Thereafter, the specific proposal to expand Capitol Reef would be largely in the hands of Superintendent Heyder.

The day after the dedication, Heyder drove over to Moab and consulted with Bates Wilson. There he saw a map of the original proposed boundaries, and they discussed Heyder's ideas. [40] Wilson then directed Heyder to "go back and pull the whole thing together and send it in and send me a copy." [41]

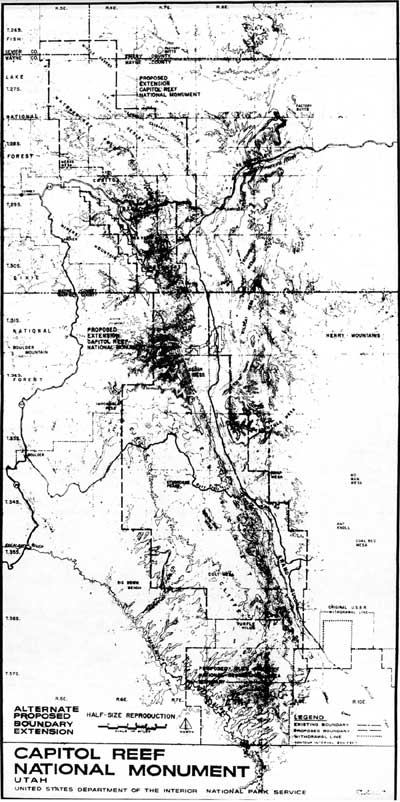

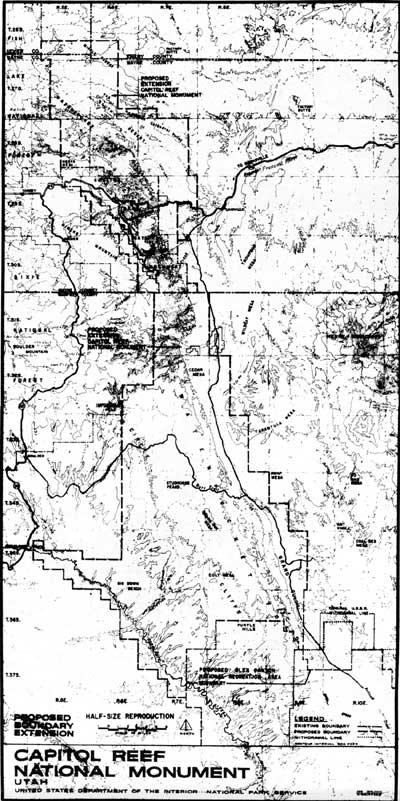

When Heyder returned to Capitol Reef, he took Chief Ranger Bert Speed into his confidence, and the two of them worked "the better part of three nights" poring over the maps and coming up with various alternatives. The first closely approximated the final January 1969 proclamation boundaries. Other possibilities, which considered adding the Henry Mountains or the Circle Cliffs, were not submitted because Heyder feared the acreage would be too big, too controversial. Later, a separate proposed boundary drawn by agency officials included the Circle Cliffs. The maps and descriptions were sent on to the regional office and from there directly to Secretary Udall (Figs. 27-28). All of this work was accomplished secretly. In fact, the text of the proposal was typed by Heyder's wife, since his secretary was Afton Taylor, wife of Wayne County rancher Don Taylor. [42]

|

| Figure 27. 1968 boundary expansion, Proposal 1, Capitol Reef National Monument. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| Figure 28. 1968 boundary expansion, Proposal 2, Capitol Reef National Monument. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Heyder was handicapped in making his boundary proposals because he could not determine what specific multiple-use claims existed in the areas involved. He believed that grazing permits were not extensive outside of the Henry Mountains, and he knew that there had been mining claims filed throughout the area. Moreover, Heyder felt that since all multiple-use claims and permits would be eliminated within the expanded boundaries of the national monument, the specific details of ownership were not a major concern at that time. Besides, even if the superintendent wanted to know these facts, there was no way he could obtain the information without alerting BLM personnel. [43]

Although these alternatives were later adjusted by park planner Norm Herkenham into the final proclamation boundaries, the initial idea to expand the monument to the park's modern configuration apparently originated with Robert Heyder. Even though specific documentation has not been located to corroborate Heyder's account, the superintendent evidently played a leading, crucial role in this significant expansion of Capitol Reef. [44]

Udall Vs. Johnson And The Monuments In Between:

December 1968 - January 1969

The final list of seven national monument expansions and establishments was presented to President Johnson by Stewart Udall on December 11, 1968. In a memorandum to the president dated December 5, Udall listed the national monument and wildlife refuge possibilities. In order, they were a 2 million-acre addition to the southern half of Mt. McKinley National Monument in Alaska; establishment of a 3.6 million-acre Arctic Circle National Monument, Alaska; a new 26,000-acre Marble Canyon National Monument, Arizona; a new, 911,000-acre Sonoran Desert National Monument, Arizona; a 94,000- acre addition to Alaska's Katmai National Monument; a 49,000-acre addition to Arches in Utah; and the 215,000-acre proposed addition to Capitol Reef National Monument in Utah. Also included were two additions to Alaska wildlife refuges totaling an additional one million acres.

It is unknown whether the list was created in order of preference or potential controversy but, in any case, Capitol Reef was far less important in the ensuing debate than the huge proposals for Alaska, or than a Sonoran Desert Monument that would encompass a military firing range in southern Arizona. [45]

During the closing months of Johnson's administration, the president increasingly surrounded himself with a circle of advisors. One of his closest advisors, Special Consul W. DeVier Pierson, would become the key liaison between Udall and the president in the weeks to follow. In his analysis, which accompanied Udall's December 5 memorandum, Pierson initially supported Udall's proposal, telling Johnson, "It would be the last opportunity to cap off your exceptional record of additions in the park system." [46]

On December 11, Udall presented his case, complete with slides, maps, and graphs, to the president and the first lady. The presentation was followed by cabinet members and aides grilling Udall on the proposed areas and on the general consequences of the president issuing such controversial proclamations during his last days in office. After the meeting, Udall believed he had persuaded Johnson to sign, once a few minor legal questions were settled. The secretary was convinced the whole package would be signed by the mid- December, as Johnson's "parting Christmas gift to the American people." [47]

Unbeknownst to Udall, Pierson was now questioning the political implications of adding such a tremendous amount of acreage to the national park system without congressional approval. On December 12, Pierson wrote the president to point out that, while the Utah and Arizona monuments engendered little controversy, the Alaska proposals were particularly senstive. Questions of oil reserves accessibility and native land claims could be expected, as well as opposition from Gov. Hickel, Nixon's recently-announced nominee for Nixon's Secretary of Interior. Pierson also pointed out the potential opposition from congressional leaders, such as House Interior Committee Chairman Wayne Aspinall of Colorado, who opposed any presidential use of the Antiquities Act to create or expand monuments. [48]

This need to clear the proposals with congressional leaders would prove to be the major bone of contention between Udall and Johnson. Udall had already talked with park supporters such as Democratic Sen. Henry Jackson, who was chairman of the Senate Interior Committee, and Republican Rep. John Saylor, minority leader on the House Interior Committee. As to the opposition, Udall believed that discussing the matter with Aspinall would be a waste of his time, as the representative would oppose the idea in any format. [49]

The secretary later recalled:

[Johnson] was much too concerned about congressional reaction, because I couldn't clear this all the way through Congress. After all, after January 20, his relations with Congress are not important. He didn't have any legislation to get through. The question was had he done what he thought was right for history and right for the country in terms of a final conservation achievement. [50]

Clearly, Udall thought of this entire issue as the deciding legacy he and Johnson would leave to conservation history. Johnson and Pierson, on the other hand, were more concerned with a possible legacy of controversy during the president's last days in office.

The deadline for approving the wildlife refuges in Alaska was 30 days before Nixon was sworn into office on January 20. While Udall could have authorized the wildlife refuges himself, he really wanted his entire package signed by Johnson in those last days before Christmas. Johnson, however, postponed signing any proclamations because he was dissatisfied with Udall's minimal congressional checks in mid-December. Further delay occurred when Johnson became ill and was hospitalized for several days, and then spent Christmas recuperating at his home in Texas. When Udall pressed about the monument approval, Pierson replied that Johnson would not decide until he personally contacted congressional leaders in January. [51]

Throughout early January, Udall continued to push for approval and Johnson kept delaying final action. On January 14, Udall delivered a breakdown of the extensive use of the Antiquities Act by previous presidents during their last weeks in office. This was attached to a memorandum to Johnson stating that everything would soon be in order and that the president could proceed with the signing the next day. An accompanying memorandum from Pierson advised continued caution:

I still have reservations as to the desirability of taking this action during the last week of your Administration. However, some of the proposed areas are very exciting. Consequently, you may wish to examine them on a case-by-case basis and act on some while deleting others. [52]

Pierson included an annotated list of the proposed national monument additions for the president's review. Capitol Reef National Monument was lumped with Arches and Marble Canyon national monuments and was "justified on the basis of unique geological or scientific qualities." Pierson had no problem with these acquisitions, provided the congressional delegations went along. The small Katmai addition posed little problem, but the proposed Sonoran Desert National Monument and the Gates of the Arctic and Mt. McKinley additions were generally seen as too large and too controversial.

Johnson wrote "OK" next to Capitol Reef, Arches, and Marble Canyon; "maybe" next to Katmai and Mount McKinley; and nothing next to the other two. The president also noted that he wanted further congressional checks "at once in depth." Thus, it seemed that Johnson was moving toward a compromise to include only the smaller additions--once congressional leaders were consulted. Capitol Reef's 215,000-acre addition would increase the monument's size by six times, yet this paled in comparison to the almost 6.5 million- acre proposals in Alaska and southern Arizona. [53]

It is unlikely that Udall was aware of this new course toward down-sizing his original proposal. On Friday, January 17, only three days before the inauguration, Udall reported to Johnson that he had discussed the idea with the Utah delegation, which had "a surprisingly good reaction." He wrote, "Even Sen. Bennett, who fought the Canyonlands National Park, favors our proposal." [54]

Udall also recounted a conversation with Aspinall, reporting that the Democrat opposed any plan that did not include congressional endorsement, but would respect Johnson's prerogatives. Udall told Johnson:

Mr. President, this is a better reaction than I had expected. I predict to you that the overwhelming praise you will receive from the conservation-minded people of this country will drown out the few complaints. [55]

Johnson, however, was not so sure. He decided to contact Aspinall personally. When the congressman told the president that Udall had never consulted him on this project, Johnson must have been more than a little surprised. Aspinall also warned that he would adamantly oppose any action not approved by Congress. According to Aspinall, Johnson called back a couple of days later, proposing a reduction to 345,000 acres from the original, 7 million-acre Udall proposal. Aspinall later recalled replying,

Mr. President, you're my president. I'm not going to raise hell, but I still stand on the principle that it isn't your responsibility and it isn't your authority to do this. This is Congressional authority....I won't object but you'll never get any money to administer it as such until Congress has a chance to look at it. [56]

At the same time this conversation tarnished Udall's credibility, the interior secretary found himself trying to keep the lid on press releases detailing the president's signing of all 7 million acres. These releases were apparently written specifically to answer questions raised by the president's State of the Union address on the previous Tuesday, when Johnson had ad-libbed that he was not yet finished with his conservation effort. This veiled reference forced Udall to field inquiries from the press and concerns from congressmen over exactly what Johnson intended. [57]

Udall and his director of information, Charles Boatner, tried to stall the press for as long as possible. Finally, Udall, believing that all seven proclamations would be signed on the Friday or Saturday before the inauguration, instructed Boatner to release the information on all seven for Monday's news. By Saturday morning, Jan. 18, the New York Times, for one, was aware of the possible proclamations and the information was out over the news wires. [58]

Udall was going to warn Johnson of these press releases at their scheduled Saturday meeting to discuss the monument proposals, but the meeting was postponed. When Johnson saw the releases coming over the news ticker on Saturday afternoon, he called Udall. The secretary recalled, "The president was very unhappy and bawled me out good that he hadn't made a decision and we turned it loose." This was the last official conversation Udall and Johnson ever had. [59]

On that same afternoon, Pierson was also pressuring Udall to help him on a completely separate issue dealing with Venezuelan oil rights. When Pierson implied that the proclamations would have a better chance if the secretary cooperated on the oil issue, Udall was infuriated. He had just been reprimanded by the president, and now his special council was telling him to play politics with the monument proposals that had become his personal crusade.

"I've made my last arguments on the parks," Udall told Pierson. "You can do what you damned please...I'm through...I've made my case and if you don't want to do anything on the parks, that's fine." [60]

Udall believed, at that point, he had quit only two days before Nixon's inauguration. He retracted the news releases and went hiking along the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal all day Sunday, his last hours in office. Nevertheless, he had National Park Service Director Hartzog wait in Udall's office throughout the day just in case Johnson changed his mind and decided to sign the proclamations. [61]

Meanwhile, back in Utah, Superintendent Heyder was completely in dark about what was happening in Washington. After submitting his maps in early October, he had fielded a few clarification questions, yet he had no idea what the final boundary decision was. He didn't even know that the Capitol Reef National Monument expansion was part of a seven million-acre proposal. If any correspondence or memos were circulating, they were doing so well over the head of the superintendent of Capitol Reef National Monument. [62]

Then, just a few days before the end of Johnson's term, Heyder received an "eyes only" package from Washington that contained the press releases and maps for each of the seven proposed monuments. According to Heyder, there were two different maps of an expanded Capitol Reef National Monument, one with the eventual proclamation boundaries and one which also included the Circle Cliffs and Escalante canyons. There were also two different press releases for the monument's expansion, apparently depending on which one Johnson chose to sign. Heyder did not know which alternative would be included in the official proclamation. [63]

Then, on Friday, January 17, Heyder's wife was driving to Richfield when she heard over the radio that the monument was going to be enlarged. She called the superintendent, who in turn phoned Regional Director Kowski in Santa Fe. Kowski was just as surprised as Heyder. The regional director called back later that afternoon and told Heyder that nothing had been signed. According to Kowski, the news leak had apparently come from the Utah delegation, which had been briefed on the Arches and Capitol Reef proposals the day before. There was still no word about which Capitol Reef National Monument expansion boundary plan had been chosen or what was actually happening in Washington. According to Heyder, at that stage, "nobody knew anything." [64]

On Monday morning, January 20, Lyndon Johnson's last day in office, the president called his special consul into his bedroom as he dressed for the inaugural ceremonies. Pierson later recalled that the two of them spent an hour discussing the various proposals,

going over these cases one last time while he was deciding whether or not he would sign any or all of them. [Johnson] finally decided that he would sign the smaller ones and not sign the larger ones. [65]

The president's decisions were made public that morning in a White House news release. The "smaller" monument proclamations that Johnson approved and signed established Marble Canyon National Monument (which was later added to Grand Canyon National Park), and enlarged Katmai in Alaska and Arches and Capitol Reef in Utah. Of the approximately 300,000 acres added to the national park system, the largest portion was attached to Capitol Reef. [66] Even though the seven million acres originally proposed by Udall had been slashed significantly because of size and controversy, the 215,000-acre addition to Capitol Reef would prove extremely significant.

As for Stewart Udall, he believed Johnson had capitulated to unwarranted concerns over the response from Congress. Years later he complained:

Any President who defers to Congress in something like this was doing what I had said all along. He ought to decide what was good for the country; because I had the Congressional backstopping done. Jackson and Sayler (sic) between them, if anybody had tried--you know the Congress could undo these. In fact, I had briefed the whole Utah delegation. I had practically at one point sold them on the fact that the two in Utah--that this was a good thing. [67]

Udall was, of course, disappointed in Johnson's eventual decision to approve only the smaller monument additions. The last two months of turmoil certainly did not help to ease Udall's disillusionment. Had Johnson signed all the proclamations, National Park Service lands would have been increased by 25 percent. Udall's record as Secretary of the Interior was already very impressive: It would have been remarkable with this last legacy. As it turned out, however, most of Udall's proposals regarding Alaska were eventually included in the 100 million acres protected by the Alaska Lands Act during Jimmy Carter's last days as president in 1980. [68]

Lyndon Johnson's conservation record would have remained impressive even had he refused to sign any of the proclamations. His refusal to sign the larger area proclamations, however, illustrated his political priorities as opposed to the aesthetic values of Stewart Udall. According to historian John Crevelli, Johnson eventually agreed to the 300,000 acres to salvage some of his political prestige and because

it would be another small step in protecting the natural environment he really loved and in giving the people one last gift in his goal of the Great Society. He needed to go out with love. His ego demanded it. [69]

President Johnson may have given a smaller gift of love than Udall would have liked, but to many native Utahns, the enlargement of Capitol Reef was an outrage. They considered it too big, too surprising, and too much an example of an arbitrary, uncaring federal government. Lyndon Johnson's fears that the proclamations would be controversial were about to be realized. The negative reaction from neighbors and politicians ensnared Capitol Reef in a swarm of controversy that has never been completely resolved.

Yet, if Johnson had not enlarged Capitol Reef National Monument, would the Waterpocket Fold be a national park today? Conflict and controversy are inevitable when land use policy changes, especially when those changes occur so quickly and dramatically. It was now up to Congress, the National Park Service, and concerned residents to wade through the ensuing rhetoric and find legislative solutions to the seeming incompatibility between traditional use and preservation at Capitol Reef. Those final, difficult steps from monument expansion to park creation are described in the next chapter.

Footnotes

1 Congressional Record, 84th Congress, 2nd session, 1956, 102, Part 4:5415-17, is evidence that there was some support for the national parks from Utah's delegation.

3 Congressional Record, 87th Congress, 1st Session, 11961, 107, Part 9:12258.

5 Carr to Anderson, 15 January 1962, Bill Folder S2234, Accession SEN 87A-E11, Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Records of the United States Senate, Record Group 46, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

6 Congressional Record, 88th Congress, 1st Session, 1963, 109, Part 10:12124, 12062.

7 Canyonlands National Park was established September 12, 1964, but debate over enlargement went on until 1971. Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, which regulates Lake Powell, was authorized in 1958, but had no legislative mandate until 1972.

8 Roderick Nash, Wilderness and the American Mind (New Haven: Yale University Press, 3rd revised ed., 1982) 200-237, details the growth of the wilderness movement, the Echo Park Dam controversy, and the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964.

9 Public Law 88-577 in U.S. Statutes at Large, 78:890-896; Roderick Nash, 225-226; Alfred Runte, National Parks: The American Experience (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2nd revised ed., 1987) 240-241.

11 "Description of Wilderness Proposal for Capitol Reef National Monument, Utah," September 1967, Box 2, Folder 7, Capitol Reef National Park Archives.

12 Ibid.; "Wilderness Proposal, Capitol Reef National Monument, Utah," September 1967, Map #CR-7400A, Box 2, Folder 7, Capitol Reef National Park Archives.

13 Robert C. Heyder, interview with Brad Frye, 1 November 1993, tape recording.

14 Superintendent's Log of Significant Events, December 1967, Box 4, Folder 9, Capitol Reef National Park Archives (hereafter referred to as Superintendent's Log).

15 "Wilderness Proposal, Public Hearing," Transcript of Proceedings, Wilderness Report Material #12, 12 December 1967, Box 2, Folder 3-4, Capitol Reef National Park Archives, 60.

16 De Von Nelson Testimony, Ibid., 61-63.

17 Special Memorandum to Members and Cooperators of the Wilderness Society, 9 November 1967, Wilderness Report Material #12, Ibid.

19 Colorado Open Space Council to Hearings Officer, 10 January 1968, Box 2, Folder 8, Capitol Reef National Park Archives.

20 Of the 492 total responses to the 1967 Capitol Reef Wilderness Proposal, 392 or 80 percent were in favor of the Wilderness Society Proposal; Official Hearings Record, Section B, #4, Box 2, Folder 12, Capitol Reef National Park Archives.

21 Heyder to Regional Director, 29 July 1968, Box 2, Folder 12, Capitol Reef National Park Archives.

22 Regional Director to Director, 8 August 1968, Ibid.

24 Barry Mackintosh, The National Parks: Shaping the System (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1991) 81-83; John P. Crevelli, "The Final Act of the Greatest Conservation President," Prologue (Winter 1980): 173-191; Melody Webb, "Parks for People: Lyndon Johnson and the National Park System," no date, copy in author's possession.

26 Stewart Udall, interview with Joe B. Frantz, tape recording and transcript, 29 July 1969, Lyndon B. Johnson Library, Austin, Texas, 25.

28 Stewart Udall, interview with Joe B. Frantz, October 31, 1969, Lyndon B. Johnson Library, 2.

29 Udall to Johnson, 26 July 1968, in staff files of Dorothy Territo, Office of President File, "Udall- National Monuments," Lyndon B. Johnson Library (hereafter referred to as Territo File), photocopy in Capitol Reef National Park Archives, administrative history notes.

30 Ibid.; Crevelli, "The Final Act of the Greatest Conservation President"; Webb, "Parks for the People."

31 Udall interview, 31 October 1969, 4.

32 William C. Everhart, The National Park Service (New York: Praeger Publishers, Inc., 1972) 175. See Runte 236-258 and Nash 272-315 for the complete account of Alaska land battles.

33 Acting Regional Director Jerome Miller to Director, 28 August 1968, Folder 32, Administrative Collection, Arches National Park Archives.

34 Acting Superintendent, Canyonlands National Park to Regional Director, 23 August 1968, Ibid.

35 Heyder, interview with Brad Frye, 1 November 1993, provides most of the information specific to Capitol Reef in this regard. The date of dedication was confirmed by an invitation found in Division of Resource Management Archives, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Page, Arizona.

40 Unfortunately, there is no record of this map in the Arches, Capitol Reef, or National Park Service Technical Information Center Archives.

42 Heyder interview; Heyder, Administrative History draft review comments, 14 December 1994.

45 Udall to Johnson, 5 December 1968, Territo File; Crevelli, 176; Everhart, 175-176.

46 Pierson to Johnson, 6 December 1968, Territo File.

47 Udall interview, 31 October 1969, 3-7. All further references to Udall interview were taken from this October 1969 interview.

48 Pierson to Johnson, 12 December 1968, Territo File; Crevelli, 177-179.

49 Udall interview, 8; Crevelli, 180.

51 Pierson to Johnson, 18 December and 23 December 1968, Territo File; Crevelli, 179.

52 Pierson to Johnson, 14 January 1969, Territo File.

54 Udall to Johnson, 17 January 1969, Ibid.

56 Wayne Aspinall, interview with Joe B. Frantz, transcript, June 14, 1974, Lyndon B. Johnson Library, 28, photocopy in Capitol Reef National Park Archives, administrative history notes.

58 Crevelli, 187, Udall interview, 13.

63 Ibid. A press release dated December 1968 and a map showing the eventual proclamation boundaries are in Box 2, Folder 5, Capitol Reef National Park Archives. There is no known copy of the other press release concerning the proposed Circle Cliffs addition.

64 Ibid.; Superintendent's Report, January 1969. Beginning on January 19, Heyder began keeping a telephone conversation log, which he subsequently gave to Chief Ranger Bert Speed when Heyder was transferred to Bryce in May 1969. It is located in Box 2, Folder 5, Capitol Reef National Park Archives.

65 W. DeVier Pierson, interview with Dorothy Pierce McSweeney, transcript, 19 March 1969, photocopy in Capitol Reef National Park Archives, administrative history notes, 20-21.

66 White House Press Release, 20 January 1969, FG-145-9, National Park Service Box 209, Lyndon B. Johnson Library.

68 Runte, 246-255, details the fight for the Alaska Lands Bill.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

care/adhi/chap10.htm

Last Updated: 10-Dec-2002