|

Capitol Reef

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 9:

1950s EXPANSION PROPOSALS AND BOUNDARY ADJUSTMENTS

After Capitol Reef National Monument was proclaimed in 1937, it remained on inactive status for 13 years. With little money appropriated and Custodian Charles Kelly paid a nominal salary, the monument was protected more by its physical isolation than by National Park Service vigilance. After 1950, the road improvement began and the post-war tourist boom started spilling over into the rugged Colorado Plateau.

To protect and make public some of the stark, rugged landscapes north of Capitol Reef, Kelly led a long effort to expand the monument's boundaries to include Cathedral and Goblin Valleys. While neither area was brought under National Park Service control during the 1950s, the reports and publicity generated by the official surveys and Kelly's promotions led directly to establishing Goblin Valley State Park, and later to including Cathedral Valley in the monument's 1969 expansion.

Even as Kelly was urging the National Park Service to expand Capitol Reef's boundaries northward, a quieter, more limited proposal to encompass the Utah Highway 24 right-of-way west of Fruita resulted in the only boundary adjustments from 1937 to 1969.

Cathedral And Goblin Valley

Proposals

Ten miles north of Capitol Reef National Monument's original boundaries lies the Middle Desert, an open, desolate valley flanked by impressive orange and white cliffs. The enormous plateau that once stretched from the Waterpocket Fold to the San Rafael Swell has eroded away, leaving a few isolated mesas. The buttes and pinnacles of Entrada silt and sandstone rise as much as a thousand feet above the flat, barren lands and dry washes at their base. It looks like a Monument Valley made from clay, instead of stone (Fig. 23). Throughout this Cathedral Valley, as Charles Kelly named it, are dikes and sills of starkly contrasting black basalt, remnants of volcanic activity that never quite reached the surface.

|

| Figure 23. Cathedral Valley. (NPS file photo) |

This is the country through which John C. Fremont's party passed while searching for a central railroad route in 1854. It is known best by the stockmen who used the valleys and mesa tops for winter grazing. Access has always been by rough, dirt roads that are impassable when wet. In the late 1940s, Charles Kelly began a personal crusade to include Cathedral Valley within Capitol Reef National Monument.

The investigation into Cathedral Valley as monument material began with a 1948 letter from Kelly to Zion Superintendent Charles Smith, suggesting Cathedral Valley as a possible addition to Capitol Reef. Kelly proposed to annex the country north of Capitol Reef to include the South Desert and upper and lower Cathedral Valley. The South Desert was to be included for its scenery and because an access road could be built through it to Cathedral Valley. [1] Ten miles to the southeast, the smaller lower Cathedral Valley, which Kelly also wanted to include, could be accessed from a rough road running between Caineville and an oil well site northeast of the monument. With his proposal, Kelly enclosed a map on which he sketched an "L" shaped addition to Capitol Reef. Although out of scale, the sketch indicates that Kelly wanted to include only the South Desert access and the northern cliff lines of Cathedral Valley. He felt the area was worthy of monument inclusion because of its outstanding scenery. Kelly argued:

"[I]n fact, parts of it are superior to anything we have in the present monument. Since there are no roads in the area it has remained unknown; but it has lately been penetrated on foot, horseback and by jeep. Eventual construction of a road would not be difficult. Such a road would enable visitors to make a loop trip without retracing and add immensely to the scenic value. [2]

The problem with acquiring this land was, as Kelly acknowledged, the fact that it was extensively used for winter grazing. In the early 20th century, there had been a homestead, supposedly built by a Blackburn family member, on Bullberry Creek at the head of South Desert. It was abandoned when a rancher north of Cathedral Valley built a ditch on the high ground to the west, usurping the water draining off of Thousand Lake Mountain and leaving the lower ranch dry. [3] By the 1940s, the land Kelly wanted was all public domain. Nevertheless, he predicted, "there would be some opposition from cattlemen who have grazing rights there." Kelly's solution to potential resistance from stockmen was to compromise and continue to offer grazing in Cathedral Valley. In a letter arguing his case, he posited:

[T]here is good bunch grass [but] so far as I can see grazing does not injure the scenic value, and if it could be continued under some arrangement, cattlemen would be glad to have it set aside, hoping some day to get a road built through it, which they could use. Otherwise it would be difficult to prevent grazing without fencing the whole section, on the open (north) side. [4]

Kelly was thus proposing the first substantial addition to Capitol Reef National Monument. To include Cathedral Valley, he was willing to allow grazing in exchange for roads and protection of the scenery. Kelly's suggestion must have been taken seriously, as it was included as a possible boundary adjustment in the 1949 Master Plan. [5]

Twenty miles northeast of Cathedral Valley (75 miles away by road) there is another, more peculiar valley shaped from the eroded Entrada Sandstone. Here, at the base of the enormous San Rafael Swell, are hundreds of chunks of the burnt orange Entrada. The sandstone is a little harder there than at Cathedral Valley, so it has eroded differently. Instead of seeing sweeping cliff lines, the visitor is greeted by a basin full of delightful hoodoos of every shape and size, sculpted by occasional summer rains, winter snows, and relentless desert winds. Stockmen have disregarded the area because it has very little grass and no water, and a large hill hides the valley from view of travelers on the old road between Hanksville and Green River. It was not until 1949, then, that the first known sightseeing party came to this bowl of bizarre hoodoos and named it Goblin Valley. [6]

Kelly inspected the valley, too, and tried to interest National Park Service in acquiring it. Actually, because the barren Goblin Valley was less attractive to grazing interests than the heavily grazed Cathedral Valley, it stood a better chance of monument status.

At the end of June 1950, an official National Park Service team investigated both Cathedral and Goblin Valleys. The team included Regional Park Planner John Kell from the Santa Fe office; Assistant Superintendent Chester A. Thomas and Chief Ranger Fred Fagergren, both of Zion National Park; Kelly; and, on the trip to Goblin Valley, Doc Inglesby, the retired dentist and avocational geologist from Fruita. The investigators spent a couple of days in the field that summer and continued their research into the fall. Kell recommended to Regional Director Minor Tillotson that more complete field studies of both areas be made the next year, but because Goblin Valley was potentially more subject to vandalism, he suggested it be considered for protection as soon as possible. [7]

Thomas reported only on Cathedral Valley. According to Thomas, Wayne County records showed no private land in the area, although the Bureau of Land Management managed grazing allotments there for about 20 ranchers. The land itself, however, had nothing but "sparse vegetative cover [which] would not seem to lend itself to economical grazing." Thomas also indicated that there were no mineral leases on record in the area, although both oil and uranium were found nearby. Emphasized throughout these reports was the unique, scenic geology; there was little obvious evidence of wildlife or archeological remains. Thomas recommended, "Because of the high scenic value and lack of other values...the area known as Cathedral Valley and the South Desert [should] be further studied as to its suitability for monument purposes." [8]

It was never firmly decided whether these areas would be administered as completely separate national monuments or as an extended portion of Capitol Reef. Kelly seemed to assume that Cathedral Valley would be annexed onto the northern boundary and that Goblin Valley would be a separate unit administered by the superintendent of Capitol Reef. As discussions progressed through the 1950s, however, Goblin Valley is mentioned more often as a separate national monument.

Those further studies of Cathedral and Goblin Valleys were postponed due to concerns over inappropriate publicity and potential conflicts with the Atomic Energy Commission. In August 1950 and again in August of 1951, the regional director wrote memoranda warning that premature publicity regarding monument investigations for Cathedral Valley and Goblin Valley could stir conflicts with state officials and private landowners. In both cases, Kelly and Zion Superintendent Smith assured the regional office that precautions were being taken, arguing that it was "ridiculous" to "disclaim all knowledge of the areas and where they are located." In fact, contemporary periodicals, particularly Desert Magazine, were promoting both locations; consequently, large numbers of sightseers, photographers and artists were taking the rough roads and trails in order to enjoy the unique landscapes. After all, it was the threat posed by increased visitation that justified proposing the area for monument protection in the first place. Also, rumors of National Park Service interest were fueled by the necessary inquiries to the BLM regarding grazing permits, and by the search for mining and homestead deeds in the Wayne and Emery County courthouses. In such small, multiple-use-dependent communities, word was bound to be widely circulated about any possible change in federal management of the lands of southern Utah. [9]

The delays caused by the AEC concerned potential uranium finds within Capitol Reef National Monument. In early 1951, the extent of uranium was not yet known, so all investigations regarding potential additions to Capitol Reef were postponed indefinitely. By July, however, an informal agreement was reached whereby the expansion-related investigations could continue so long as the AEC was consulted before any such action was formally proposed. [10]

The more extensive investigations of Cathedral and Goblin Valleys finally began in September 1951. A large party of National Park Service officials, including Leo Deiderich from the Washington office, John Kell and Harold Marsh from Santa Fe, and BLM representatives from Salt Lake City and Richfield spent two days in each area photographing and discussing potential boundaries and conflicts. Their guides were Charles Kelly and tour guide Worthen Jackson, of Fremont, and their report was similar to the one issued a year earlier. The one significant change was the elimination of Cathedral Valley from further consideration. For Goblin Valley, however, national monument status was still a possibility. [11]

By the summer of 1952, the National Park Service determined that Goblin Valley was perhaps better suited to be a state park, although the justification for this is not explained in the documentation. [12] The only problem with this plan was that Utah did not have an established state park system, and there was little money to begin one. Thus, Utah Gov. J. Bracken Lee argued that Goblin Valley should be given national monument status, instead. Goblin Valley was being tossed between the National Park Service and the State of Utah like a hot potato. [13] Until the National Park Service could determine how to proceed with Goblin Valley, the regional office decided at least to petition the BLM to withdraw the proposed lands from potential mining while continuing to allow grazing privileges. [14]

The land, however, was never officially withdrawn from mining, and the issue was suspended until 1956. In March, Utah Sen. Arthur Watkins wrote a scathing letter to Interior Secretary Douglas McKay, opposing any new national monuments in Utah unless the local people were adequately consulted and the lands were adequately developed, in contrast to "the almost complete neglect" the National Park Service had shown toward Arches, Capitol Reef, and Natural Bridges National Monuments. [15]

In the summer of 1956, newly appointed Regional Director Hugh M. Miller determined to see Goblin Valley for himself. According to Miller, the area was interesting and unique, but, he wrote,

I do not feel that it is an area of great importance....It seems to me that the better strategy would be to have the citizens, and the officials, of the state of Utah 'chase us' with this area rather than for us to pursue its establishment vigorously. [16]

Miller felt the area was not significant enough to do battle with the local residents and state officials over national monument status: if the people of Utah wanted a Goblin Valley National Monument, they had to demonstrate that desire. So far, that had not been the case. By 1958, newly elected Gov. George D. Clyde liked the National Park Service idea of Goblin Valley as a state park, and so "accordingly the NPS will take no further action to secure National Monument status for this area." [17]

Thus ended initial attempts to increase dramatically the size of Capitol Reef National Monument by adding Cathedral Valley to the north, and to annex Goblin Valley or establish it as a separate national monument. Goblin Valley eventually became a state park many years later. As for Cathedral Valley, its future is told in the next chapters.

The 1958 Boundary Expansion

At the same time that Cathedral and Goblin Valleys were being proposed as possible extensions to Capitol Reef, other suggested boundary adjustments were also being considered.

When the monument was created in 1937, the boundary ran along the northern right-of-way to Utah Highway 24 from southwest of Twin Rocks, past Chimney Rock, to the Castle formation. This boundary had been suggested by Roger Toll during the final boundary revisions in 1935, in order to avoid complications with the road's maintenance. [18] The problem was that the road in those days followed the usually dry wash bottoms in several locations. When summer floods changed the course of the wash, the repaired road was realigned to one side or the other, thereby changing the monument's boundary each time the grader came through. The situation was magnified in 1952 when a new, graveled section of Utah Highway 24 was completed between Twin Rocks and Chimney Rock, swinging the road's right-of-way northward by almost one mile. [19] Construction of a completely realigned and paved Utah Highway 24 from Torrey to Fruita in the late 1950s would cause further confusion. Toll's idea of making the road the boundary to avoid road construction concerns was simply not working. The obvious solution was to extend the monument to include the entire road from the western to the eastern boundary. Besides avoiding boundary realignments, this would give Capitol Reef more control over future road construction and maintenance. A limited boundary adjustment to include at least some of the road was proposed in the 1949 Master Plan. According to the plan, the road boundary was of concern because it was

a primitive, unimproved one running across the prairie and through sandy washes[.] [I]ts location [was] frequently changed by floods and the vagaries of the traveling public. It would seem more desirable to place the boundary by section lines or a natural feature less subject to change. [20]

The 1949 Master Plan also recommended some additional lands be added to the monument to buffer the scenic Waterpocket Fold from public domain to the west. Another continuing problem with the boundaries was that they were both unfenced and largely unsurveyed. In such rugged, rocky terrain covered by numerous steep, narrow canyons, cliffs, and terraces it was difficult to determine exact boundary lines in the field. Even near Fruita, the lack of boundary markers caused problems. For example, in early 1949, Kelly erected an entrance sign on "a section corner just east of Sulphur Creek crossing." The sign was torn down every few days until Kelly learned that Cass Mulford claimed the western half of the section was his. While this matter was eventually resolved, the exact boundary lines on the ground, especially the northern and southern lines where they crossed the Waterpocket Fold, would not be adequately determined for several years. [21]

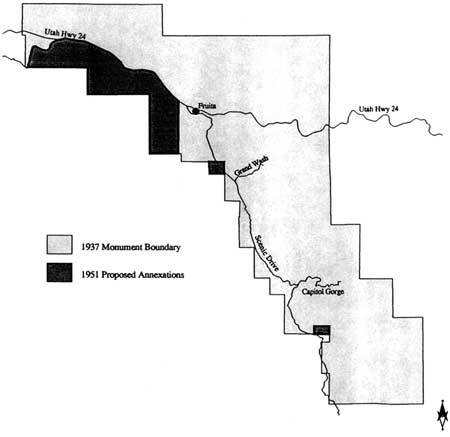

Meanwhile, attempts to include the highway within the monument continued. The 1951 Boundary Status Report proposed that new boundaries be adjusted to run along section lines that would include the entire western approach of the state highway, from the hill west of Twin Rocks (today's western boundary) to Fruita. The state's Section 16 (all Sections 16 were set aside for the state to generate revenue for public schools), immediately west of Fruita, was included in the proposal to insure adequate protection in case the state decided to sell or lease the land. Section 21, immediately south of the state section, was also proposed as part of this boundary revision. Much of Cass Mulford's ranch lay within this section, but planners believed he wouldn't object to this. An additional 80 acres were needed to add a portion of the state highway between Fruita and Capitol Gorge (in its old alignment) (Fig. 24).

|

| Figure 24. 1951 proposed annexations to Capitol Reef National Monument. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Two 40-acre tracts were also advocated, to incorporate the Pleasant Creek access road just in case it was chosen as the later route for Utah Highway 24. [22]

The justification for these additions was primarily to include roadways not initially encompassed by the original boundaries. Scientific justification for adding land south of Utah Highway 24 was to protect fossil tracks, which "promise[d] to be even more important scientifically that those within the monument on the other side of the road." [23]

These trackways, later identified as the footprints of swimming Chirotheria (reptilian precursors to the dinosaurs, that lived 200 million years ago), had been studied by Dr. Charles Camp and others for several years. Charles Kelly was adamant about protecting them. [24] (Kelly saved several blocks of Moenkopi siltstone with these trackway impressions from almost certain destruction during construction of Utah Highway 24 in 1956, leaning them up against the ranger station, where they still stand today.) [25] Thus, there were resource issues as well as practical issues whose resolution depended on the boundary amendments.

Throughout the 1950s, the uncertain status of the road created "several hundred acres of 'no-man's land.'" [26] The National Park Service decided to postpone making boundary adjustments until after construction of the new road. Meanwhile, the southern boundary, which was the Wayne/Garfield County line, was finally surveyed in July, 1952. With a clear southern boundary, Kelly and the omnipresent uranium miners could now tell whether tunnels were being dug in the monument. Fortunately, most of the mining claims along the southern border were in Garfield County, outside of the monument. [27]

By June 1957, the newly aligned and paved Utah Highway 24 was finished from Torrey to Fruita. [28] The paved road brought renewed hope to Wayne County residents who had been waiting 20 years for tourist dollars. The finished road delighted Superintendent Kelly because of the visitation it would bring, and because those visitors would induce the park service to spend a good deal of Mission 66 money developing facilities at Capitol Reef. The most immediate effect of the road's completion, however, was that it enabled National Park Service officials finally to propose specific boundary revisions for the area west of Fruita.

In early 1957, with the new road's alignment established, the proposed boundary revisions were approved by the director and Utah congressional delegation and were aired in public hearings in Cedar City on June 12. Arches Superintendent Bates Wilson and Les Arnesberger, of the regional office, attended the meeting and told Kelly on their way home that "there was no opposition at the hearings and the meeting only lasted two hours." [29]

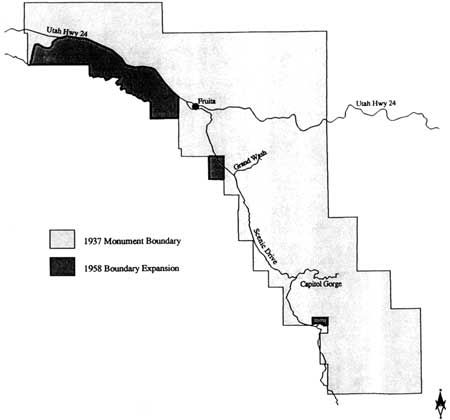

The proposed boundary expansion received little attention because it was very modest, including no land then being mined or grazed. Documentation regarding the final adjustments is lacking, but something motivated National Park Service officials to change the boundary west of Fruita from section lines to the natural outline created by the deep, impressive Sulphur Creek canyon. Such an obvious--and very scenic--border would be easier to patrol and monitor than would invisible section lines. Now the complete landscape between Spring Canyon and Sulphur Creek would be within the monument. Agency officials also decided to include all of Section 16, just west of the ranger station, but to eliminate the Mulford property in Section 21 from the final boundary adjustment.

South of Fruita, other small adjustments were made. The remaining 240 acres of the section west of Grand Wash were added to include a small section of the old highway's alignment near the Egyptian Temple formation, which had been left out of the original monument. A couple of small tracts north of the old Floral Ranch were also added to the revised boundaries to include the old Pleasant Creek access road. Only the road itself was included within the new boundary, leaving Lurton Knee's land untouched (Fig. 25). The entire boundary extension added 3,040 acres, increasing the total size of Capitol Reef National Monument to 39,185 acres. The boundary revision was formally authorized by President Dwight D. Eisenhower's proclamation on July 2, 1958. [30]

|

| Figure 25. 1958 boundary expansion, Capitol Reef National Monument. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Thus, by the end of the 1950s Capitol Reef's boundaries were set. Southern and northern boundary surveys had pinpointed the exact location of the monument, and the 1958 expansion brought all of Utah Highway 24 under monument control, from the northwestern boundary through Capitol Gorge. During these 1950s boundary questions, official correspondence did not address any disagreements between local residents or elected officials and the National Park Service concerning the various proposals. An adamant letter from Utah Sen. Watkins may have influenced National Park Service officials to re-evaluate monument status for Goblin Valley, but they were already leaning toward state control, anyway. The minimal expansion of 1958 seems to have been noncontroversial. In short, it seems the National Park Service was willing to move slowly and/or compromise in regard to expansion and development, to insure good will toward Capitol Reef. In turn, local residents and elected officials seemed more concerned with finally developing Capitol Reef than with minor adjustments to its boundaries. This lack of conflict stands in stark difference to the battles waged over the impacts from Mission 66 development, and to the volatile debate over the monument's next expansion in 1969.

Chapter 7 provides a general overview of Capitol Reef management concerns from 1955 to 1966; the following chapters cover the 1969 monument expansion to the 1971 creation of Capitol Reef National Park.

Footnotes

1 The existence of more than one name for areas in Capitol Reef's North District is confusing. South Desert is the valley drained by Polk Creek between the Waterpocket Fold and the Hartnet Mesas. The lower end of this valley is sometimes referred to as South Draw. Charles Kelly changed the name of the area where most of the escarpments and pinnacles are found from "Middle Desert" to "Cathedral Valley." Ranchers who use the area still refer to it as the Middle Desert.

2 Kelly to Charles Smith, 28 August 1948, File 601, Accession #79-60A-354, Box 2, Container #63180, Records of the National Park Service (RG 79), National Archives - Rocky Mountain Region, Denver (hereafter referred to as NA-Denver).

3 Guy Pace, interview with Brad Frye, 13 February 1991, tape recording and transcript, Capitol Reef National Park Archives, 30-31. According to Pace, Blackburn put up some fences but never built a house, which is probably why there is no documentation associated with this homestead. There are also pieces of steel machinery and evidence of attempts to plow the ground.

4 Kelly to Smith, 28 August 1948.

5 "1949 Master Plan and Development Outline," File 600-01, 79-60A-354, Box 2, RG 79, NA-Denver, 6.

6 "Field Report on Goblin Valley," September 1951, Box 2, Folder 8, Capitol Reef National Park Archives, 10.

7 "Cathedral Valley and Valley of the Goblins, Summary," 24 November 1950, Box 1, Folder 7, Capitol Reef National Park Archives.

8 Thomas to Zion Superintendent, 26 July 1950, File 610-02, 79-60A-354, Box 2, RG 79, NA-Denver.

9 Smith to Regional Director, 30 August 1951; Kelly to Zion Superintendent, 19 August 1950; and Preston Patraw to Smith, 10 August 1951, all in File 610-02, 79-60A-354, Box 2, RG 79, NA-Denver.

10 Director Demaray to Regional Director, 19 March 1951 and 6 July 1951, Ibid.

11 "Field Report on Goblin Valley," September 1951, Kelly to Kell, 2 January 1952, Ibid. There is nothing in the reports or correspondence that specifies why Cathedral Valley was dropped from consideration. Former concerns over the amount of grazing in Cathedral Valley plus the mention that Goblin Valley had no grazing permits at all suggests that grazing was the reason for excluding Cathedral Valley at this time.

12 Regional Director to BLM Region 4 Administrator, 3 July 1952, Ibid. From here on, the records pertaining to Goblin Valley are sketchy.

13 Patraw to National Park Service Director, 9 November 1953, File L58, 79-67A-505, Box 1, Container #342490, RG 79, NA-Denver.

14 Patraw to BLM Region 4 Administrator, 8 September 1952, File 610-02, 79-67A-354, Box 2, RG 79, NA-Denver.

15 Senator Arthur Watkins to Secretary Douglas McKay, 29 March 1956, File L58, 79-67A-505, Box 1, RG 79, NA-Denver.

16 Regional Director's Report to Files, 1 August 1956, Ibid.

17 Ibid. Also see map showing "Status of Area Investigation Activities, Region Three," July 1958, in the same file.

19 "Roads and Trails Map," February 1949, Document #158-2101, National Park Service, Denver Service Center, Technical Information Center, Denver.

20 "1949 Master Plan and Development Outline," 6.

21 Kelly to Smith, 27 February 1949, File 602, 79-60A0354, Box 2, RG 79, NA-Denver.

22 "Boundary Status Report," 11 June 1951, Ibid. Also see Chapters 6 and 7 on the debate over Pleasant Creek or Fruita as the eventual headquarters location.

24 Charles Kelly, "Ancient Trackways," Charles Kelly Unpublished Writings, Capitol Reef Unprocessed Archives.

25 Superintendent's Monthly Reports, December 1956, Box 4, Folder 3, Capitol Reef National Park Archives (hereafter referred to as Monthly Reports).

26 Patraw to Zion Superintendent, 25 November 1952, File 602, 79-60A-354, Box 2, RG 79, NA-Denver.

27 Thomas to Regional Director, 8 August 1951; Kelly to Zion Superintendent, 20 February 1952 and 27 July 1952, Ibid.

30 Presidential Proclamation, "Enlarging The Capitol Reef National Monument, Utah, Proclamation #3249," 3 C.F.R. 160 (1954-58 Compilation). There is confusion over the exact acreage of the expanded monument. If one adds the 37,060 acres listed in the 1937 presidential proclamation to the 3,040 acres in the 1958 expansion proclamation, the total acreage should be 40,100 acres. Yet, in the 1964 Master Plan (Box 3, Folder 1, Capitol Reef National Park Archives) the new acreage is listed as 39,172.63 acres; and in the National Park Service's 1970 Legislative Support Data, the figure is 39,185 acres (File W3815, #79-73A-136, Container #790698, Box 4, RG 79, NA-Denver). While more research is needed to explain these discrepancies, I suggest that the differences are due to more recent, precise boundary surveys.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

care/adhi/chap9.htm

Last Updated: 10-Dec-2002