|

Capitol Reef

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 14:

FRUITA MANAGEMENT HISTORY

"What do we do about Fruita?" This question has no doubt been asked by every National Park Service manager concerned with Capitol Reef. There have been no easy answers regarding Fruita, which is constricted in size by towering cliffs and mesas, and is the focus of various competing interests.

Controversy began decades ago, when private landowners struggling to maintain their way of life and monument managers trying to fulfill their mission sometimes conflicted. Later, after Fruita was acquired by the National Park Service, managers were faced with deciding which buildings would remain and which should be razed. Unfortunately, these decisions were often guided more by aesthetics and infrastructural needs than by a sense of history, and they stirred further local controversy. Once a decision was made to preserve historic Fruita, managers had to determine how to go about it. The recent National Register listing of the entire Fruita area, identified as a rural historic landscape, will help shape a long-term, cohesive policy. But even now, managers must reconcile the often conflicting needs of historic preservation and visitor services within the confines of the historic district.

This study traces National Park Service policies toward Fruita, from inholding conflicts, through Mission 66 developments, to later efforts to manage the historic resources. The purpose of this discussion is to chart the National Park Service's evolving management philosophy toward Fruita. Please consult other chapters of this administrative history or the cited references for more details on area history, prehistory, or other specific issues.

Fruita Becomes Part Of The Monument:

1931-1937

The unique landscape that brought the National Park Service to the Waterpocket Fold country has also limited the agency's ability to develop the area. The rugged, arid, slickrock topography channeled potential visitor services to the few accessible flat spots near water. The only sites that met this criterion within the original monument are those places where the Fremont River and Pleasant Creek enter and exit the Waterpocket Fold. The three most suitable locations for headquarters development -- Notom, Floral Ranch, and Fruita -- have a long record of human habitation; however, of these areas, only Fruita was included within the original monument boundaries.

For the National Park Service officials charged with studying possible boundaries and future development potential of the Capitol Reef area, Fruita was the obvious choice for headquarters development: it was easily accessible, had potable water, and included flat, open land suitable for buildings and campgrounds.

The first in a long series of difficult decisions facing the National Park Service was whether Fruita should even be included within the proposed national monument. The first National Park Service official known to visit the area was Zion National Park Superintendent Thomas J. Allen. In July 1931, at the urging of local business leaders, Allen went to "Wayne Wonderland" to investigate its possibilities as a national park or monument. In describing the region's spectacular scenery, Allen observed that the best of it was around Fruita. [1]

Allen's initial report brought official investigator Roger W. Toll to the area the following year. Toll, like Allen, traveled to Capitol Reef via the rough dirt road from Torrey to Fruita, and continued on through Capitol Gorge. Toll reported that Fruita consisted of "two ranches and a roadside store" and was "probably the best base from which to explore the country." [2]

Toll returned to the Waterpocket Fold country in November 1933 to conduct a more thorough investigation. By this time, local promoter Ephraim Pectol had persuaded the Utah State Legislature to pass a resolution proposing national park or monument status for the area, and providing specific boundary recommendations. These boundaries, presumably drawn up by Pectol himself, specifically excluded the private lands of Fruita. [3]

The problem with this first boundary proposal, according to Toll, was that the proposed monument would be broken into three separate units. After five days of study and discussions with Pectol, Toll recommended that Unit 1, between Torrey and Bicknell, be dropped from consideration, and Unit 2, which encompassed the upper Fremont River Gorge, be connected to an expanded Unit 3. This area would thus protect the Capitol Reef section of the Waterpocket Fold north, east, and west of Fruita. Toll was clear on the point that the private lands of Fruita, itself, were to be excluded from the national monument proposal. [4]

Fruita was not included in the proposed monument's boundaries until after Zion Superintendent Preston P. Patraw's more extensive investigation in 1935. This detailed analysis of lands and resources within the recommended Capitol Reef National Monument introduces the first Fruita management policy:

At the suggestion of the Director's office, Mr. E. P. Pectol, of Torrey, had worked out a boundary line which would include the private lands of rural Fruita. The wisdom of doing so and subsequently acquiring the private lands is apparent when it is realized that Fruita is the logical place for locating the center of future monument development, and that under continued private ownership uncontrolled and competitive development of tourist accommodations is bound to follow progressively with increase of tourist visitation. [5]

Patraw insightfully observed, "[Fruita] is centrally located in the area and any highway constructed must go through the town. All land suitable for administrative and tourist facilities is in private ownership." [6]

Zion's Superintendent also recognized that purchasing the private lands of Fruita would not be easy. Patraw estimated, based on the "local opinion of land values," that the total cost of purchasing the approximately 100 acres of "rich fruit lands with ample water rights" would be around $50,000. The opinions of the Fruita residents regarding this proposal were not mentioned. [7]

It should be noted that none of the other possible locations that met development criteria was recommended for inclusion within Capitol Reef National Monument. Thus, Fruita was the only possible location for National Park Service development during these early years.

Early Developments: 1937 - 1942

In the euphoria surrounding the 1937 presidential proclamation creating Capitol Reef National Monument, the inherent conflict between National Park Service development needs and continued private ownership in the same restricted area was overlooked. Correspondence among Ephraim Pectol, Superintendent Patraw, and Regional Director Frank Kittredge does not mention previous recommendations to purchase the Fruita lands. [8] Instead, development was to proceed at a slow pace. Kittredge cautioned, "We are going to have to do some thorough studying before we undertake any development. We cannot afford to make mistakes by jumping into work, perhaps scarring some of the country and then wishing we had not." [9]

Of course, lack of money even to conduct preliminary surveys of the new monument also must have played a key role in postponing any attempts to purchase the Fruita lands. Yet, both Patraw and Kittredge recognized the need to either build or acquire some kind of headquarters building and associated water rights. Patraw specifically recommended that a previously proposed Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) crew be assigned to Capitol Reef as soon as possible. [10]

From 1938 to 1942, the CCC built the ranger station, performed extensive stream bank stabilization along the Fremont River through Fruita, improved the Hickman Bridge trail, constructed a new bridge across Sulphur Creek, and realigned and otherwise improved several sections of the monument road. [11]

Because all of the most desirable property was already privately owned, the ranger station was built on public land on the western edge of the community. According to the 1939 master plan, a residence and utility area were to be built adjoining the CCC structure. [12]

After the CCC was disbanded at the beginning of World War II, federally financed construction at Capitol Reef National Monument halted until the early 1960s. Historic photographs from the 1940s and 1950s starkly contrast the lonely CCC building on barren land west of the road to the lush fruit farms on the east. These pictures can be seen as a metaphor for the National Park Service presence at Capitol Reef during this period: minimal and peripheral.

Any future growth in the agency's presence at Capitol Reef was directly tied to the acquisition of private lands at Fruita. The 1938 Development Outline for Capitol Reef National Monument clearly stated, "Monument headquarters developments logically belong at Fruita. The desirable land being in private ownership, a complete development plan for a headquarters, including visitor accommodations and services, may not be prepared until the land is purchased or otherwise acquired." [13]

World War II significantly affected National Park Service development throughout the country. Recently established units such as Capitol Reef were dealt a particularly hard blow. The war effort siphoned off money, personnel, and agency attention, leaving a minimal National Park Service presence at Capitol Reef. The land continued to be used for farming, grazing, and mining, as though the area had never been set aside as a national monument. The nearest National Park Service officials were in Bryce Canyon and Zion National Parks, nearly an entire day's drive away. This lack of federal attention must have disappointed local tourism boosters. Yet, from those living in or using the lands within the monument, there was surely a sigh of relief. Already suffering from years of agricultural depression and war-time restrictions on gas and tires, residents of Fruita struggled to continue their customary lifestyle, monument or no. The lack of National Park Service controls allowed them to do so. The situation led local residents to believe that their traditional use of lands now within the new monument would not be challenged.

By 1943, Zion National Park Superintendent Paul R. Franke, who would oversee Capitol Reef operations between 1939 and 1959, had realized that it was no longer practical to wait for acquisition of Fruita before planning monument developments. Franke wrote:

The present Superintendent recognizes the conflict of private land but can see no reason why [the] majority of present owners cannot continue to reside and operate their ranches within the Monument. With encouragement from the Service, these owners can be encouraged to develop and maintain their property in conformity with standards to be established....The type of physical developments should conform to the early Mormon type of architecture (stone). [14]

While Franke did not clarify his idea of "early Mormon type of architecture," his is the first known reference in a planning document to Fruita as a potential interpretive local for Mormon culture and history.

The problem with Franke's suggestion was that these "standards" would have to be imposed on private landowners who had resided in Fruita long before the monument was established. Further, the nearest National Park Service presence was hundreds of miles away. Until Franke could secure a habitable residence, water rights, and a staff to provide the monument with a continual National Park Service presence, any Fruita management policy was moot.

From Accommodation To Acquisition: 1943 -

1956

Superintendent Franke must have been greatly relieved to acquire the Alma Chesnut place, its .66 second feet of water, and Charles Kelly as volunteer custodian. [15] However, long-range planners continued to struggle with the Fruita dilemma.

In the 1949 master plan development outline prepared by Zion Superintendent Charles J. Smith, there is a good example of the conflicting attitudes toward Fruita. On one hand, Smith writes, "The choice building sites are [sic] in private ownership within the monument and private enterprise is at present developing a hodge-podge of cabin camps, beer joints and cheap shops on private land." [16] On the other hand, Smith observed:

It is suggested we deviate from Service policy in that we do not attempt to procure all the private lands within the area. The picturesque town of Fruita is situated within the monument. It is a part of the native scene and it is believed we should not attempt to purchase all the land which makes up the small community, at least, not for the present. [17]

Although the desirability of acquiring Fruita was recognized, lack of management control was resulting in private tourist developments deemed unacceptable by National Park Service officials. With no money to purchase the offending private facilities or construct alternative public accommodations, there was little Smith or Charles Kelly could do about the "hodge-podge" nature of tourist developments in the area.

Due to the war and extremely poor roads into Capitol Reef throughout the 1940s, visitors were mostly either local people using the monument on weekends and holidays, or a "higher-class" of adventure seekers who actually preferred the lack of developments. [18] In 1943, the only tourist accommodations were six "poor shacks without any modern conveniences" owned by Doc Inglesby and William Chesnut. [19] By 1946, a private landowner began an ambitious attempt to build a replica of the Zion Lodge at Fruita, but high costs and the owner's poor health forced compromises on the Capitol Reef Lodge's size and appearance. [20]

Although visitation to Capitol Reef began to increase during the 1950s post-war prosperity, the development of hospitality facilities at Fruita was more directly a result of the uranium boom. Capitol Reef Lodge was improved to accommodate winter guests and Dewey Gifford built a motel in his front yard to serve the steady stream of prospectors passing through the area. Local people were also counting on increasing tourism, though, once the roads into Capitol Reef were improved.

In 1950, the National Park Service contemplated purchasing Dean Brimhall's property, across the road from the ranger station, for the residential/utility area and a campground. When Brimhall declined to sell, Zion's Superintendent was actually relieved. [21] Smith believed that the time was simply not right to make long-range plans for a campground or residence on the private lands of Fruita. Smith wrote, "We believe it is just wishful thinking and not at all realistic to plan the key developments, and development which is essential in the near future, on land which we have only a remote prospect of obtaining at an early date." [22]

Smith, however, still favored minimal facilities, such as a campground to be built on the old Alma Chesnut property. He believed that such a facility would meet visitor needs for five or 10 years. Smith observed, "If such campground proves to be inadequate or in the wrong location, we can write it off when the time comes and be satisfied that it has served the people reasonably well for a reasonable time." [23]

Smith realized that acquisition of the private lands of Fruita was several years off, and that National Park Service development of visitor facilities would be delayed accordingly. Back in 1948, the cost of purchasing Fruita was inhibitive, and managers also worried about how the local economy might be affected by such a transaction. According to Smith:

To acquire all inholdings at Capitol Reef, it would be necessary to purchase the land on which the little town of Fruita lies. This land consists almost entirely of highly productive fruit farms. The cost would be great. Recent sales have amounted to $300 per acre and the bearing fruit tree acreage is held at from $800 to $1000 per acre....Purchase by the government would decrease the taxable property in Wayne County -- perhaps the poorest county in point of taxable property in the state of Utah. [24]

This concern, coupled with the desire to preserve "this picturesque pioneer Mormon settlement," [25] prompted Superintendent Smith to consider the Floral Ranch area on Pleasant Creek as a location for monument headquarters. This uncertainty over where headquarters should be located is exemplified in the following September 1948 statement by now Associate Regional Director Preston Patraw:

The choise (sic) between Fruita and Floral Ranch for Monument headquarters is a very narrow one. The Floral Ranch site has the advantage of being much less dislocating of local communities than would be involved at Fruita. On the other hand, I would consider Fruita as being the more strategic location for administrative headquarters. However, if there is a way to acquire the Floral Ranch I believe I would favor that location, because of the much greater ease and less expense with which the headquarters could be established there. [26]

Ultimately, the location of the monument's headquarters would be determined by the route of the new paved highway through Capitol Reef. In 1956, when the Utah Bureau of Public Roads agreed to build the road through the Fremont River canyon, the Pleasant Creek headquarters idea was abandoned. [27]

When Capitol Reef National Monument was officially activated in 1950, the slowly developing public facilities were still restricted to the edges of Fruita proper. A small campground was finally placed along Sulphur Creek north of the ranger station, and a few picnic tables were set out near the old schoolhouse property owned by Merin and Cora Smith. Apart from the CCC-built ranger station and the Chesnut house where Kelly lived, there were no National Park Service-owned buildings at Capitol Reef until the early 1960s.

The 1953 master plan, written by Superintendent Charles Kelly, proposed purchase of a small amount of private lands for headquarters developments. Since campground, utilities, and residential developments needed to be near the ranger station (which still had no water allocation), acquisition of the Brimhall estate was still the principle objective.

It was Kelly's continued hope that Fruita could be preserved:

The orchards on private land at Fruita, within the monument, make a very favorable impression on desert travelers during the summer. The current policy is to leave these private owners where they are, as part of the local picture, rather than eventually to acquire all private land as was done at Zion, although this will create minor problems and occasional difficulties. [28]

Thus, throughout most of the 1940s and early 1950s the management policy toward Fruita was one of reluctant acceptance. Once it became clear that purchasing the private lands of Fruita was not practical, managers could only hope that voluntary compliance with building standards might make Fruita a more "picturesque town." At the same time, minimal developments such as a campground, and even future residences, were to be constructed at the entrance to Fruita. These were to serve the needs of the monument until the situation changed. Thanks to Mission 66, these changes would occur rather rapidly.

Determining The Fate Of Fruita:

1955-56

When Director Conrad Wirth embarked the National Park Service on its unprecedented 10-year development plan, Mission 66, the acquisition of private property in Fruita became possible. Because of management and resource conflicts with inholders in many of the more famous national parks, Wirth wanted to acquire as many these private lands as possible, either through purchase or exchange. A National Park Service report describing the general objectives of Mission 66 stated, "Development of these lands as private homesites or for commercial enterprises detrimental to the parks, the hindrance they present to orderly park development, and the problems they present to management and protection, warrant their acquisition at the earliest practicable date." [29]

This service-wide goal, along with anticipated Congressional funding allocations, must have been good news to the management staff at Zion. They could finally acquire the private lands of Fruita as part of the overall Mission 66 development plans for Capitol Reef National Monument.

In April 1955, Zion Superintendent Franke answered a general questionnaire on the problems and needs for all parks under his charge. Of the existing problems at Capitol Reef, he observed, "The alien lands, private and State, present the most serious threat, which threatens to hinder public use and destroy the area character....It is estimated that approximately $125,000 would purchase the key private holdings in area known as 'Fruita.' "

As far as concessions were concerned, Franke reported:

Public accommodations on private lands inside the boundary are undesirable and messy. The Capitol Reef Lodge and property should be acquired. Cost is probably $35,000....There appears to be no practical location outside the boundaries for centers of overnight use. The small agricultural community of Fruita is the most logical overnight center and its use and growth will not impair park values. [30]

Superintendent Franke believed that $160,000 would relieve Capitol Reef of a significant management problem as well as provide the needed space for future public facilities. The regional director in Santa Fe, however, was not so sure that all of Fruita should be acquired. In May 1955, Hugh M. Miller, who was in the process of moving from assistant to regional director, wrote Franke:

It seems to this office that probably we should not attempt to destroy this little community through the acquisition of all these tracts. The community is in itself an "exhibit in place," a typical Mormon settlement which has retained much of its early day charm....In other words, it is our feeling that it is more interesting to have these properties occupied and the normal community life carried on than to acquire the properties, remove the buildings, and let the gardens revert to weeds and the ditches fall into disuse. [31]

To solve the problem of undesirable inholdings, Miller suggested that the monument boundary be redrawn so as to exclude most of Fruita. [32]

This 1955 debate, which was to decide Fruita's fate, was centered on three points:

Was there enough room in the tiny valley for the development of adequate, long-range National Park Service facilities and for private inholdings?

Was Fruita still a "typical Mormon settlement?" [33]

If so, would it be better to simply redraw the boundaries and divest the inholdings?

Zion Superintendent Franke seemed to be the only one to answer "no" to all three questions. In passing on the regional director's memorandum to Kelly, Franke included a cover letter discussing his own opinion of Fruita's long range value. He wrote:

It seems to me that the idea of an exhibit in place featuring a typical Mormon settlement is far from the real picture and would neither reflect credit to us or to the Mormon pioneers. It is true that there are some colorful characters living in Fruita at the present time but that they are either typical or in keeping with the dignity of the National Park Service as 'exhibits in place' are concerned is questionable. When they are gone, the 'typical Mormon settlement' is likely to revert to a frontier slum town and not a dignified exhibit that is likely to add anything to the awe inspiring and natural beauty of Capitol Reef, or to the credit of the National Park Service. [34]

Superintendent Kelly opined that Fruita had indeed evolved from pioneer to modern in character over the past decade, but he argued against acquisition of all the Fruita inholdings:

If all the private lands are purchased, it means that the park service will have to operate the lodge and motel as concessions, and it also means that we would have to irrigate all the land in order to maintain shade trees and grass, since it would be unthinkable to let this little oasis revert to desert. Its green trees and fields are its greatest attraction, enjoyed by all the traveling public. [35]

Kelly also pointed out that speculation over the coming of the new highway had caused land prices to triple over their 1941 value, "beyond any real present value." This situation, coupled with Kelly's desire to preserve the Fruita "oasis," led him to make two recommendations:

The National Park Service should purchase the Max Krueger property, east of Kelly's residence, for construction of a campground and to ensure access to Hickman Bridge Trail. [36]

The monument boundary should be modified to exclude the remaining private lands of Fruita. [37]

Superintendent Franke disagreed. In a strongly worded memorandum to Regional Director Miller, he pointed out that Mission 66 charged the National Park Service with acquiring lands to provide for adequate public use. Franke argued that the monument boundary should not be changed to exclude Fruita, and that the Krueger property alone would be inadequate for monument developments. He stated:

[I]t is difficult for me to accept permanent abandonment and alienation of desirable lands within the area merely for the reason that funds for acquisition would be difficult to obtain. History has taught me that in our National parks and monuments we usually strangle ourselves by too little land with the result that objectives highly important are lost forever....History also teaches that a compromise with ideals and retreat to a line that can be defended before local citizens is a good method for increasing the 'headaches.' If a National park or monument is worthy let's fight for it. If the area is not worth that national status let's recommend its abolishment. [38]

Further, Franke argued:

We must, to be in tune with Mission 66, stop thinking of 15 years ago or of the present. Let us realize that by 1966, 250,000 visitors will come to Capitol Reef....These visitors will come in spite of our failure to properly plan and develop. To plan to develop only about 1/2 of 1 percent of the area for public use is not being realistic. We must accept the facts and that 6 or 7 percent of the area will have to be made available for public use, in order to satisfy that public, and that usable land is only around Fruita. [39]

Franke pointed out that piecemeal purchase of the Fruita inholdings (i.e., acquiring the Krueger property immediately and purchasing other properties as the need arose and/or as funding became available), would lead to administrative and maintenance problems. He wrote, "Minimum land needs in the Fruita area, from my viewpoint, are: all lands north or south of the Fremont River. My preference, if a choice has to be made, is for those lands north of the river, where we are now established." [40]

Franke recommended that all National Park Service buildings and visitor facilities be placed on public lands north of the river, but that no lodgings be provided there. Rather, lodgings could be provided by private businesses outside the monument and south of the river. Regarding the historic value of Fruita, Franke argued:

The worn out buildings are such that even the most pious Mormon would disown. Historic quaintness may be associated with the 'old timers.' However, their time in a permanent exhibit is but a passing moment....How can we build a typical 'Mormon Community' out of such temporary variables as human beings? These are transient values and we should not let our misguided sympathies for a few 'old timers' and their structures...divert our attention from the real values and significant points of Capitol Reef. [41]

Superintendent Franke believed that, given the limited area suitable for building in the Fruita valley, the National Park Service must choose between preserving "early day charm" and providing visitor facilities. To Franke, facilities were more important than sentiment, and Mission 66 provided an opportunity to upgrade the monument.

Notably, Franke's detailed, impassioned argument never mentioned Fruita's orchards. Presumably, he believed that all lands north of the river -- including the orchards -- would be needed for monument developments.

Unfortunately, there is no record of Director Miller's or Superintendent Kelly's responses to Franke's memorandum. Franke must have persuaded the regional director, however, because the initial drafts of Capitol Reef's Mission 66 Prospectus all included the "bold proposal to acquire all inholdings within the Monument which would include the entire town of Fruita." [42]

This proposal caught the attention of National Park Service Director Conrad Wirth. He favored acquisition of the inholdings, pending a more detailed report. [43] In response, Assistant Zion Superintendent Chester A. Thomas submitted a detailed table of the various private and state inholdings in the monument. The table showed:

Although there is a total of 686.92 acres of land in private ownership within the boundaries, (note this is exclusive of state owned lands) only some 130 acres is irrigated farm land suitable for development. The balance of 556 acres is wasteland very little of which would serve for development purposes. Much of it lies above the ledges of the canyon. It would seem that 130 acres of flat land is not an unreasonable acreage to request for a headquarters site and for development of campgrounds, residences and utility area. Although the acreage of useable land is small, some it is orchard land and has a high cash value. [44]

This table lists the 11 state and private inholdings (state lands are combined) within the monument in order of acquisition priority. The cost of purchasing the nine private inholdings in the Fruita was estimated at $123,000. The land was needed, according to Thomas, for visitor use, development, and roads and trails rights of way. [45]

In the final (April 1965) Mission 66 prospectus for Capitol Reef National Monument, proposed locations for the visitor center, residences, and campground were not specified. [46] The prospectus was clear, however, about private inholdings in Fruita:

Privately owned lands within the monument occupy practically all of the land suitable for development for visitor use and administrative purposes....There is no justification for maintaining the old settlement of Fruita because it is neither typical of pioneer settlements nor is there any value that might enhance understanding or appreciation of the area. Reduced to its proper perspective acquisition of the private lands within the monument is in accordance with Service policy and need not constitute a major undertaking. [47]

This proposal for acquiring the private property for Mission 66 facilities would be the basis of all development plans during this period. Given the limited area available for development, the National Park Service felt compelled to purchase the inholdings. The effects of this move on residents, their homes, and their orchards, were of lesser concern.

The prospectus also called for eliminating all motels, rental cabins, and other lodgings from the monument, at least until 1966. Small concessions for gas, meals, souvenirs, and camping supplies would be permitted. The 50-car campground proposed for Fruita could be expanded to 100 sites, and could later be moved or supplemented by a campground at Pleasant Creek (once the land was acquired). [48]

The prospectus does not detail plans for Fruita's buildings and orchards. The only mention of trees in Fruita is a recommendation to spray periodically the "large number of valuable shade trees in the area" to control parasites and disease. [49] At least some of the old irrigation ditches would be maintained to water vegetation in the campground. [50]

Additional water rights, which were to come with the purchase of the inholdings, would be utilized for irrigating vegetation in the campground and around public buildings. Planners evidently assumed that this, plus the water needs for the visitor center, residences, and other National Park Service buildings would require all available water rights. None of early Mission 66 planning documents or correspondence mentions the need to irrigate the Fruita orchards to protect these accumulated water rights. Further, no documentation has ever been found suggesting that the Fruita area be restored to its natural vegetative condition. [51]

From Removal To Restoration: 1959 -

1966

As mentioned above, the early Mission 66 plans did not specify how land and buildings would be used once the private inholdings were acquired. These specifics could not be planned until the routing of the new highway, which would require right-of-way through the monument, was settled. Once it was realized that most of the land north of Sulphur Creek and north of the Fremont River after its junction with Sulphur Creek would be needed for this right-of-way, it became much easier to justify purchasing the remaining inholdings. The Brimhall, Sprang, Inglesby, Smith, and Krueger lands were acquired for the Utah 24 right-of-way and future developments. The Mulford and Chesnut properties were purchased for potential campground expansion, amphitheater, and picnic areas. This left the Brimhalls' house and a portion of their orchards, Capitol Reef Lodge, and the Gifford farm as the only private property remaining in Fruita.

By the early 1960s, planners had a better understanding of the acreage needed for development. Because some areas were prone to flooding, and because the park service preferred to centralize monument facilities, the actual area available for development was quite restricted. This meant that Mission 66 developments would not necessitate eliminating all traces of the old Fruita community: structures in undesirable locales could be left standing. [52] A 1959 draft master plan development analysis observed:

[T]he physical characteristics of the narrow Sulphur Creek and Fremont River Canyons create a development problem. Occasional flooding of large areas topographically suitable for development precludes their use for housing or visitor center facilities. Sulphur Creek's meanders cut that Canyon into several areas, some of which are too small for any developments proposed. [53]

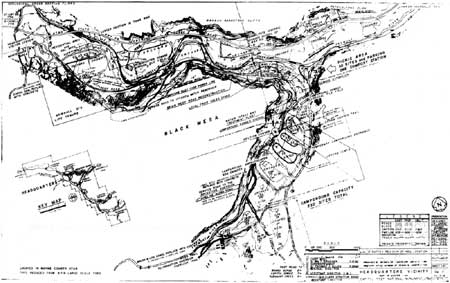

If stream meanders and flooding precluded some areas from construction, what would be done with those "unusable" areas -- many of which were planted in fruit trees? Proposals offered in 1959 were contradictory. The 1959 master plan narrative acknowledges, "Fruit orchards watered by irrigation from the Fremont River cover a large percentage of the Canyon Floor and present a striking contrast to the red cliffs surrounding them." [54] However, preservation of the orchards was not addressed by management policy or actual development plans. In fact, 1959 master plan development drawings show the Fruita area as being occupied by National Park Service developments, or as empty floodplains. Orchards are not shown on these maps (Fig. 36). [55]

|

| Figure 36. 1959 Master Plan. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

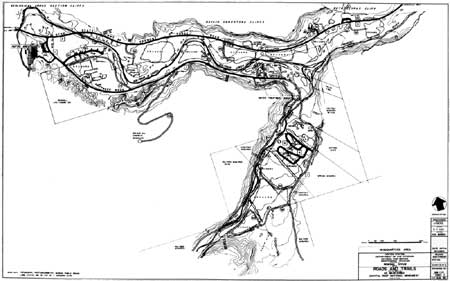

| Figure 37. 1962 Master Plan, Fruita area roads and trails. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Thus, just prior to purchase of most private inholdings, construction of the new highway, and construction of Mission 66 developments, there was no clear plan for management of Fruita. The decision to preserve these orchards and a few remaining buildings came several years later. While the reasons for this decision are not documented, they probably resulted from a combination of practicality and a slowly evolving acknowledgment that Fruita had some historic value.

Practical considerations were paramount, given that there was limited area available for development. Fruita's settlers had built their homes on those few sites that were relatively safe from flooding, but which were close to water. Those happened to be the only practical places to build a campground, visitor center, utility buildings, and staff residences. Ultimately, operational and visitor needs took priority over preservation of existing conditions.

Further restricting National Park Service plans was the fact that some of the old Fruita homes were continuously occupied and their orchards cultivated throughout the development period of the early 1960s. These private lands and residences included the Fremont River farm where park employee Dewey Gifford and his family resided, Clair Bird's Capitol Reef Lodge, and the Brimhalls' life estate. Throughout the early 1960s, then, the decision to keep some of the orchards and several original buildings was made by default. Continued occupation of some homes would insure that part of historic Fruita would survive, at least for a time.

Managers would next have to decide how to manage Fruita's orchards and any structures not razed to make room for National Park Service improvements. Over a period of several years, the idea evolved to administer these resources as an historic Mormon village. There was little guidance available for such an approach. National Park Service officials were left to work out their own unique -- and often contradictory -- guidelines.

The first task was to clarify the historical significance of Fruita's remaining original buildings and structures. According to a draft 1961 master plan narrative, the legacy of the Mormon pioneers was found in "their landmarks [which] are the orchards, the cultivated fields and the houses and log school at Fruita." [56]

Within the same document, under the heading, "Design a Park Program that Has a Distinctive Capitol Reef Flavor" the potential value of a historic Fruita landscape was also acknowledged. It advised:

In addition to the usual planning and design practices, retain the distinctiveness by capitalizing upon the existing atmosphere created by the Mormon pioneers at Fruita through their more than fifty years of open ditch irrigation. Retain, so far as possible, their cultivated fields, orchards and certain buildings. Plan developments, including campgrounds and other public use areas, to take advantage of the existing ditch. Retain as many of the fruit trees and fields as possible and fit the use areas to the irrigation system. Lease out farming operations and fruit orchards, if necessary, to retain this character. [57]

In another draft of this 1961 master plan narrative, someone wrote the marginalia, "Which buildings?" and then listed in order, "Sprang, Inglesby, log cabin at Mulfords, and schoolhouse." Of these, only the former Sprang cottage (which today is not considered historic under National Register criteria) and the schoolhouse were saved. [58] The place of orchards in historic Fruita seemed assured, as the 1962 master plan drawings show the fruit trees intermingled with Mission 66 developments (Fig. 38). [59] Even so, the idea of retaining the "flavor" of Fruita was contradicted by construction of the new highway right through the heart of the valley and by development of a new campground where orchards had stood. The conflict between historical preservation and the need to provide visitor and staff facilities had begun.

|

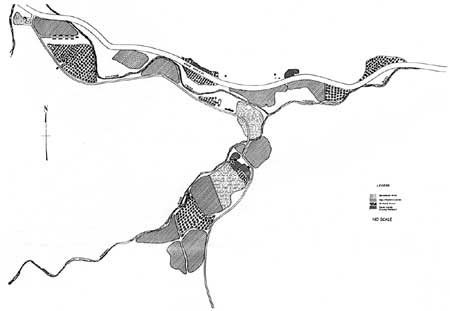

| Figure 38. Proposed historic agricultural area, 1977. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

At the height of Mission 66 construction in 1964, a new master plan design analysis encouraged the purchase of the last two remaining private tracts, on which stood Gifford Motel and Capitol Reef Lodge. It further recommended expanding the campground from 53 to 230 sites, developing the Brimhall property as soon as it could be obtained, and eliminating the old superintendent residence once the new facilities were in operation. The orchards, vineyards, and pastures were determined to be part of the landscape, which should be preserved. [60] Maximum irrigation of the Fruita area was to continue so as to maintain its water rights, orchards, and oasis character. To improve water distribution, the plan called for replacing, realigning, and otherwise improving irrigation ditches and flumes. [61]

A September 1965 master plan, never approved by the regional office, specified that preservation of the "early pioneer atmosphere" would be accomplished by retaining "certain old buildings and portions of the fruit orchards." Fruita would be interpreted mostly with the aid of mimeographed leaflets and a taped message at the restored Fruita schoolhouse. [62]

The 1965 master plan also acknowledges the regard of local residents for Fruita. In justifying issuance of a special-use permit to Worthen Jackson to maintain the orchards, managers observed:

Since the first settler came in 1882 the orchards of the old community of Fruita in the headquarters area of the park have been a source of fruit for the entire locality. Local residents take pride in this fruit orchard area. In order to retain the historic character of the area and to retain public relations these orchards are retained and are maintained by special use permit. [63]

This is the first time that Mission 66 plans acknowledge local opinion concerning Fruita management. In the decades to follow, this local attachment to Fruita would become a key consideration in any management plan for the area.

By the end of Mission 66 development, Fruita had significantly changed. The Smith and Krueger houses, outbuildings, and sizable sections of their orchards were gone in the wake of the new highway right-of-way. A large portion of the old Brimhall property was now occupied by the monument residential area, and the new campground on former Sprang land south of the Fremont River had replaced fruit trees and pasture. The Inglesby house and cabins were gone, as were the buildings on the William and Dicey Chesnut property. The log cabin, fruit cellar, animal sheds, and corrals on the Mulford land at the southwestern edge of Fruita were also removed during this period.

While Fruita was definitely different, a surprising amount of the old private community remained. The schoolhouse, Holt/Chesnut house, Brimhall and Sprang residences, and almost the entire Gifford farm were still standing, as were two fruit cellars, two lime kilns, and the Pendleton rock walls. Most of the orchards, pastures, and irrigation system were also still intact. The Capitol Reef Lodge remained as well, although continuing clashes with owner Clair Bird compelled most National Park Service officials to urge its acquisition and removal as soon as possible. [64]

At the beginning of Mission 66, it seemed as if the fate of Fruita had been determined: fruit trees and farms would be replaced by National Park Service facilities and visitor use areas. However, development limitations, continued occupancy of some houses, and the need to maintain newly acquired water rights delayed development while a growing appreciation of Fruita's qualities emerged. Ultimately, a large portion of the historic landscape was preserved. Now park service managers had to determine what exactly could be done with all the inherited buildings and fruit trees.

Managing Fruita As An Historic District:

1962-72

As soon as the National Park Service acquired the inholdings, it turned over the management of orchards and fields over to Worthen Jackson, who paid $100 annually for a special use permit. Jackson, who spent summers with his family in the old basement house on the Sprang property, had previously managed orchards for Brimhall and Sprang. Since the National Park Service had little orchard experience or desire to invest time and money in tree maintenance, this arrangement was advantageous to both parties. [65]

Under the special-use permit, Jackson was given all rights to fruit produced, provided he would preserve "the character of the land area in a similar manner as existed prior to the acquisition of the property, and...protect, through beneficial use, the water rights acquired with the land." [66]

Jackson was responsible for all orchard operations, including "ditch cleaning, proper fertilization, and pruning, weed control, proper irrigation, etc." [67] Throughout the 1960s, Jackson, his son Kent, and hired help pruned the dead wood, sprayed the trees, picked the fruit, and cut the hay. They took orders from towns as distant as Salina and Circleville, and peddled the ripened produce door to door throughout Wayne County. The Jacksons also sold fruit from a produce stand near their house. In good years, their fruit business could be very profitable. Yet, it seemed every good year was followed by a late freeze or some other problem that reduced the fruit crop, and thus the profit margin, considerably. [68]

There were occasional problems with the arrangement between Capitol Reef and Jackson. For example, in October 1968, concerns over potential health risks forced Superintendent Robert Heyder to halt Jackson's practice of selling canned fruit from his fruit stand. [69] At other times, promised assistance from National Park Service maintenance crews was redirected to other projects. [70] In early 1971, while the final steps toward national park status were being taken by Congress, Jackson decided that he'd had enough. According to Jackson, new irrigation and fertilization requirements plus additional demands to maintain the hay fields were costing "more than the orchards would bring in for all fruit sold." Contributing to Jackson's frustrations were several consecutive late freezes during the late 1960s. Whatever the reasons for quitting, Jackson implied in a statement published by newspapers throughout Utah that, without him, the orchards would soon fall into disrepair. [71]

In an effort to counteract any negative publicity from Jackson's statements to the press, General Superintendent Karl T. Gilbert of the Southern Utah Group wrote a letter to the editor of the Richfield Reaper. According to Gilbert, Jackson had refused to provide the proper amount of fertilization, pruning, weed control, and irrigation as recommended by the Utah State University Agricultural Extension Service. Gilbert also maintained that, while the orchards were ultimately the responsibility of the National Park Service, "operation of the orchards should be the responsibility of the permittee, and should not involve the expenditure of public funds to ensure a fruit crop for the permittee." [72]

By June 1971, Robert Sweet of Taylorsville, Utah had been granted the special-use permit for the orchards, and Superintendent William F. Wallace had promised that "'realistic resources management practices [would] be used to upgrade the quantity and quality of fruit." [73] Sweet, however, lasted only one season. In 1973, the National Park Service issued special-use permits to local residents and organizations for the various fruit crops. The Torrey Ward of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints harvested the cherries, and local resident Colleen Shelley was responsible for the apricots and peaches. The Wayne County Jeep Posse was in charge of the apples and pears. The following year, the National Guard was contracted to take care of some of the fruit crops, but the allure of hunting season drew members away at the critical time, leaving bushels of fruit to rot on the ground. [74]

It soon became apparent that Capitol Reef National Park had to assume direct control of the orchards and fields in the headquarters area, and authorize the funds necessary for their upkeep. Nevertheless, the process of taking over full, active control of the orchards was slow. In 1973, Worthen Jackson's son Kent, who had helped his father manage the orchards as a teenager, was hired along with Richard Jensen to work as seasonal laborers in the orchards. In 1975, Emmett Clark, a permanent National Park Service maintenance employee, was selected by Superintendent Wallace to manage the orchards full time. Clark continued as orchard manager until his retirement in 1985. For several years following, Clark would return during fruit harvests to help run the pay stations for U-pick fruit. Kent Jackson became orchard manager in May 1985, following in the footsteps of his father. [75]

Other changes were also occurring in orchard management. For instance, a new underground irrigation system was installed in 1975, increasing watering efficiency and reducing the labor needed to keep the old, open ditches flowing. [76] Perhaps most significantly, managers finally recognized the historical significance of the entire Fruita community, orchards and all.

Attempts To Preserve Fruita: 1976 -

1979

The Fruita schoolhouse was nominated for listing on the National Register of Historic Places and $10,000 were authorized for refurbishing the building in 1966. This action suggested that Fruita in its entirety might soon be officially recognized as an historic district. [77] Nevertheless, managers continued removing buildings, adding new ones, and altering the landscape, not considering the effects on the area's historical integrity. [78]

This trend changed in 1974 when Gerald Hoddenbach was hired as the first resource specialist at Capitol Reef National Park. Although hired as a research biologist, Hoddenbach soon developed a keen interest in the history of Fruita. His interest was first piqued by the history of his assigned residence, the old superintendent's house that had been built by Leo Holt and sold to the National Park Service by Alma Chesnut in 1944. From there, Hoddenbach began looking into other aspects of the old settement's past, thereby launching the first investigation into Fruita history since Charles Kelly's early years at Capitol Reef. [79]

Hoddenbach's research culminated in a draft cultural resource management plan in November 1974. In it, he proposed to create a "Fruita Living Community," combining existing structures and orchards with living agricultural history exhibits and possible historic building reconstructions (Fig. 38). The "Living Community" would illustrate early pioneer settlement and life as it existed in the 1920s, and would also "vividly represent and synthesize the lifestyle and agricultural methodology found in many such local communities." [80] According Hoddenbach's research, "the height of development and population occurred about 1930 and settlers began to leave the valley in 1938. Thus, the most appropriate period in time to focus on seems to be 1920-1930." [81]

Even in the final drafts of his plan, Hoddenbach struggled to define the interpretive emphasis and focus of the living community. For instance, in the November 10 draft he removed a reference to "Mormon" pioneer settlement and substituted "early," instead. He also changed the name from "Fruita Living Community" to "Historical Fruita Community" in one place, and reduced the proposed size of the district from 300 to 200 acres.

Hoddenbach argued that such a historic living community would be representative of an agricultural and farmer's frontier under the National Historic Landmark Program, and would also meet the goals of the National Park Service guidelines for historic areas. The plan also included the first known list of historically significant structures within Capitol Reef National Park. [82]

The National Register multiple resources nomination forms were completed in September 1977. Included in the nomination were all structures that had existed in the Fruita area prior to the arrival of the National Park Service in 1937, as well as the Sulphur Creek lime kiln, the Behunin cabin (on private land owned by Wonderland Stages) and the Oyler Mine tunnels and related ruins. Also contributing to the historic district would be Fruita's abundant archeological sites -- primarily Fremont Culture petroglyph panels -- and the orchards. The focal point of the historic district was to be the Pendleton-Gifford farm. Finally, the nomination now defined Fruita's historic period of interpretation as the 1930s. [83]

This National Register nomination summarizes how past, current, and future management of Fruita were regarded in 1977. The nomination narrative stated:

Since emphasis was upon the spectacular scenery of the reef and Waterpocket Fold, Fruita structures were [torn] down, with few regrets, to make room for park amenities. Fruita was simply not recognized as an historical resource. Now the value of this isolated Mormon village is realized, almost too late. The structures that remain not only reflect early pioneer life, but also reflect the remarkable continuity of life in the 60 year period prior to Park Service acquisition. The Pendleton-Gifford Ranch stops the clock just prior to the point in time the national monument was formed. This decade, the 1930s, is about as representative of Fruita development as any other since Fruita's existence is not marked by a hiatus. [84]

Regarding the orchards, the statement continued:

More than 3,000 fruit trees at the park are of historic and interpretive value. Pear, apple, peach, apricot, and cherry trees occupy the historic orchard sites, as well as more recently cultivated areas. Though plans call for the abandonment of the non-historic orchards, historic orchards are considered as significant as the historic structures. The trees are not being nominated at this time. [85]

National Park Service managers had clearly stated that Fruita's remaining structures and orchards were of historical significance and should be preserved. However, the multiple property nomination emphasized individual buildings and structures, rather than the landscape as a whole. The concept of cultural landscapes had not yet been well defined or utilized. While Hoddenbach's initial nomination was eventually rejected for "deficiencies in preparation," his work was not fruitless. It would later be incorporated into the National Register nomination of the Fruita Rural Historic District, a vernacular cultural landscape that included all components -- buildings, structures, orchards, fields, roads, and ditches -- of Fruita.

Hoddenbach's proposal to remove "non-historic" orchards was part of a new orchard management plan being devised even as the National Register nomination was in the submission process. In late September 1977, Superintendent Wallace circulated a preliminary "Historical Agricultural Management Area Plan" for public review and comment. According to the park's press release, the plan would divide the headquarters area in four sub-zones:

Historic Farming. This sub-zone would include Gifford Farm, the Brimhall place, and Fruita Schoolhouse.

Greenbelt. This sub-zone would have five single-fruit orchards (as opposed to mixed stands of fruit trees) with pasture crops cultivated between them.

Development. This sub-zone would include park headquarters, residences, campground, and picnic areas.

Private Ownership. This sub-zone would include Capitol Reef Lodge and a small parcel at the junction of the Fremont River and Sulphur Creek. [86]

The goal of this plan was to maintain historic structures and the surrounding orchards and fields as they would have appeared in the 1930s. To meet that goal, park officials estimated that the number of fruit trees would have to be reduced by almost half. That proposal brought an immediate outcry from the residents of surrounding communities, demonstrating (perhaps to the surprise of the National Park Service) the magnitude and nature of local regard toward Fruita. [87]

At an Aug. 2, 1978 community meeting in Loa, newly appointed Superintendent Derek O. Hambly walked into a room of angry neighbors to hear their opinions of his predecessor's plan. While many liked the park service recognition of the historic and cultural importance of Fruita, they were upset that so many fruit trees were to be cut down to duplicate the appearance of the 1930s. The historical era to be represented, they argued, was just an arbitrary date, and did not justify destruction of more recent orchards. [88] Of course, it did not help Hambly that former Superintendent Wallace had already ordered the removal of approximately 500 trees -- including an entire prized peach and apricot orchard on land formally owned by Cass Mulford. [89]

Evidently, too, some local people used this occasion to vent frustrations lingering since the unpopular expansion of Capitol Reef a decade earlier. Overall, though, the group's main concern was that the fruit-picking tradition at Fruita was coming to an end. Superintendent Hambly must have taken these complaints seriously, because after this meeting he revised the tree count. Instead of 1,700 trees in five single-crop orchards, Fruita would have approximately 2,500 trees in eight orchards. Some of these would be single-crop orchards, but others would retain mixtures of fruit trees. Since the park in 1978 had 2,563 fruit trees, this revised plan meant that few trees would have to be culled. [90]

For perhaps the first time, local residents had been given a voice in the management of historic Fruita, and they overwhelmingly favored preserving Fruita's orchards and remaining structures. Later, many of the participants in this hearing credited their protests over the 1977 plan with saving the orchards. [91]

Fruita Historic District: 1982 - 1988

Through the efforts of Hoddenbach and other Capitol Reef personnel, the historical significance of Fruita was finally formally acknowledged by park managers. Needed next was a cohesive management plan that would treat Fruita as a holistic system instead of a group of isolated features. With such a plan, managers could better evaluate the effects of National Park Service actions on the historical integrity of Fruita.

At the time, though, the concept of cultural landscapes and their eligibility for National Register listing was not widely recognized or understood. Most nominations were multiple property nominations, based on a collection of separate features -- mostly standing buildings and structures. Because many of Fruita's buildings had been razed or significantly altered during Mission 66 development, Fruita as a whole appeared to lack the historical integrity required for a National Register multiple property nomination.

In the 1982 general management plan, the headquarters area is called "The Fremont/Fruita Archeological/Historic District." It encompassed 840 acres in the Fruita area, and included prehistoric rock art panels, historic period structures, and the historic scene. Fields and orchards were identified as contributing to resource significance. This district was being submitted for listing, along with the archeological/historic districts at Pleasant Creek, Capitol Gorge, the Oyler mine, and an individual nomination for the Behunin cabin. [92]

According to the 1982 general management plan, the Fruita area was to be managed as a two-part historic zone. The preservation subzone would encompass "those areas that are significant because of their association with personages, events, or periods of human history and prehistory. Included [would] be archeological sites, prehistoric rock art panels, historic period structures, and the historic scene." [93]

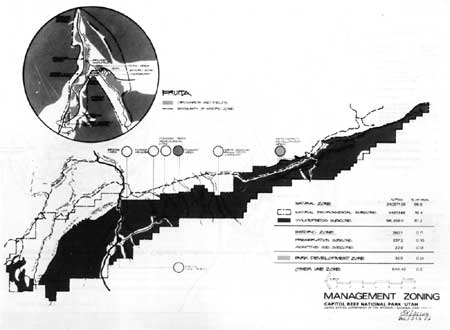

The other adaptive-use subzone would include sites that had been modified in some way by the National Park Service. These areas included the headquarters/residence area, campground, roads and utilities, as well as the "Chesnut-Pierce" and Gifford houses, which were being used at the time for employee housing (Fig. 39). [94]

|

| Figure 39. Park management zoning, 1982 General Management Plan. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The development alternative advocated by the 1982 general management plan called for removing Capitol Reef Lodge, employee trailers, and the Sprang house. This would provide an additional 2.8 acres of "historic pastoral setting." It is not clarified whether this land would be planted with fruit trees or left as open space. It was argued that this additional historic acreage would somewhat offset the plan to displace five acres of orchards with an enlarged Fruita campground. The CCC-built ranger station, which had been partially attached to the visitor center in 1964-65, was also to be protected from any future headquarters expansion. [95]

Thus, by the early 1980s, the variety of historic resources in Fruita had been acknowledge and a definitive preservation and development plan had been devised. It seems, however, that park managers were still looking at each resource on an individual basis rather as part of a whole. Until managers could take the larger view, adequate protection and interpretation of Fruita would not occur.

In June 1984, the divisions of interpretation and natural resources each produced comprehensive management plans. The cultural resource management plan, written by Chief of Interpretation George Davidson, focused on the historic structures, whereas the natural resources management plan, prepared by Norman Henderson, was limited to insect and mammal management in the orchards. [96] The two crucial components of the landscape were not yet being managed as one.

Davidson's background in historical interpretation was perfectly suited for helping to develop a Fruita historic district. In his 13 years at Capitol Reef National Park, Davidson had compiled historic photographs and oral history interviews from Fruita and area residents. He had also acquired historic farm machinery for display in orchards and fields, provided oral and visual interpretation of the Fruita schoolhouse and Merin Smith's old workshed, planted historic-variety fruit trees where the lodge once stood, and developed a visitor center exhibit centering on early Fruita. In addition, Davidson wrote a short, popular book on the people and lifestyles of historic Fruita, and organized a yearly historic crafts demonstration fair known as Harvest Homecoming Days. Davidson did more to interpret Fruita than had anyone before him. [97]

Davidson's 1984 plan detailed the prehistoric and historic significance and interpretive themes of the Fruita area, and identified the need for maintenance of the remaining historic structures. [98] In order to better document those who lived in or were acquainted with historic Fruita, Davidson proposed a comprehensive oral history program. [99] The cultural resource management plan also proposed to plant trees to screen modern National Park Service developments from view. Wrote Davidson, "Both the GMP and National Register nominations now recognize the value of maintaining -- even recovering -- the rural, bucolic, atmosphere of Fruita." [100] The proposed solution was the drafting of a historic scene enhancement plan that would soften the disharmony between new and old structures as well as provide guidelines for future developments.

In 1988, the revised orchard management plan finalized the idea of managing Fruita as an integrated cultural landscape. Influenced by Robert Z. Melnick's 1984 Cultural Landscapes: Rural Historic Districts in the National Park System, Chief Interpreter Davidson, Chief Ranger and Acting Superintendent Noel Poe, Resource Management Chief Norman Henderson, and Superintendent Martin Ott proposed nominating Fruita to the National Register as a rural cultural landscape. They argued, "[I]t is critical to maintain and preserve the total impression of an earlier day that is created by a balance of orchards, pastures, hayfields, and remnant historic buildings." [101]

Once aware of the possibility of cultural landscape designation, park managers seized upon it as a way to guide management of the various prehistoric and historic resources found throughout the headquarters area. Before such a management document could be produced, however, the National Park Service first had to determine whether Fruita met the criteria for listing as a rural cultural landscape.

The Fruita Rural Historic District Debate:

1990 - 1994

From 1989 through 1994, the Fruita landscape was the focus of two extensive examinations. First, in 1989, the National Park Service decided to contract a comprehensive, park-wide historic resource survey and multiple property nomination. One goal was to survey and evaluate both prehistoric and historic resources of the park and then integrate the two studies into a multiple resource nomination. The main objective, though, was to evaluate any potential cultural landscapes according to the instructions found in National Register Bulletin 30. [102] The scope of work was issued in early 1990 and that September, John A. Milner Associates, a Philadelphia firm with experience in cultural resource management and historic preservation, was selected as the contractor for the $51,600 project. [103]

Chief of Resources Management & Science Norman Henderson, whose division was responsible for both natural and cultural resources, was to be the park contact; Supervisory Regional Historian Michael Schene was the technical representative and overall coordinator for the project. [104]

Milner Associates' project manager, principle researcher, and editor was Dr. Patrick O'Bannon, who had extensive experience with historic structure nominations in the eastern United States. In mid-October 1990, O'Bannon came to Capitol Reef to met with Schene, Regional Archeologist Adrienne Anderson, and the park's management staff. During a quick reconnaissance of the park's resources, the contract's specific details were discussed. Participants concurred that a cultural landscape study or report would not be required of the contractor, after all. [105] Park managers, however, did request that O'Bannon continue to evaluate the Fruita's eligibility as a cultural landscape. [106]

The author of this administrative history served as guide and associate park contact for O'Bannon through the rest of 1990 and early 1991. Throughout his on-site investigations during November and in follow-up conversations, O'Bannon voiced the opinion that Fruita had been significantly and adversely impacted by National Park Service developments. He concluded that National Park Service management of Fruita, particularly during development of the 1960s, had destroyed historical integrity and rendered the area ineligible for nomination as an historic district or landscape. [107] In his final survey report, O'Bannon wrote:

Perhaps the most significant result of the survey was the determination that the Fruita area, the core of the park and a former Mormon farming community, had suffered a considerable loss of integrity during the past fifty years. Photographs, homestead proofs, tax records, and other documents clearly indicated that the present appearance of Fruita's cultural landscape and built environment differ significantly from their pre-1940 appearance. Consequently, it was determined that Fruita no longer retained sufficient integrity to warrant designation as a historic district or cultural landscape. [108]

O'Bannon did, however determine that 13 historic resources in the Fruita area were individually eligible for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places. Ten of these qualified under the "Mormon Settlement and Agriculture" context, while the remainder were associated with CCC developments prior to 1942. O'Bannon also regarded nine other structures throughout the rest of the park to be eligible for nomination. These included Behunin Cabin, Oyler Mine, the Pioneer Register, the Hanks dugouts on Pleasant Creek, CCC improvements on old Utah 24 (Scenic Drive), Oak Creek Dam, and the Upper Cathedral Valley line cabin and corral. Thirty-five other sites or resources investigated within the boundaries of Capitol Reef National Park were determined to be non-contributing and not eligible for National Register protection. [109]

As O'Bannon was writing his recommendations, an unrelated archeological survey of Capitol Reef National Park from the Fremont River to Pleasant Creek was also in progress. Under a professional services contract with Archeological-Environmental Research Corporation, F. Richard Hauck, principal investigator, undertook an exhaustive rock art and site inventory and multiple property national register documentation. These reports were to be integrated with the results of the historic survey into a multiple property nomination. [110]

O'Bannon's recommendations were accepted by both Michael Schene and Roger Roper, of the Utah State Historic Preservation Office. Capitol Reef and other Rocky Mountain Region officials, however, were dissatisfied. They criticized the generalized statements and lack of specific information on many sites included in the original scope of work, but were particularly upset about O'Bannon's assessment of Fruita. At a time when Superintendent Charles Lundy was contemplating building more employee housing, and park and regional officials were preparing the groundwork for a new general management plan, guidelines for managing Fruita were desperately needed. National Park Service staff, believing that Fruita would be found eligible for listing as a cultural landscape, thought a National Register nomination would help provide that direction. O'Bannon's conclusions, then, were a surprising disappointment . [111]

The dissatisfaction over O'Bannon's recommendations caused park and regional officials to look elsewhere for an alternative evaluation. Even before Milner Associates submitted its final draft in June 1992, Historic Landscape Architect Cathy Gilbert, of the Pacific West Regional Office, was invited to reassess Fruita's potential as a cultural landscape. After a scope of work was finalized in May 1992, Gilbert arrived at Capitol Reef with Kathy McKoy, a historian from the Rocky Mountain Regional Office, to examine Fruita. [112] Gilbert had previously worked on historic landscape reports and designations for several National Park Service areas in the Pacific Northwest and was well versed in the concepts needed to evaluate the potential of Fruita as a cultural landscape. [113]

After a week of preliminary investigation, Gilbert concluded that Fruita retained enough spatial and system integrity to be eligible for nomination as a rural historic district. As Gilbert explained it, a landscape is made up of small, medium, and large scale components. Her initial impression was that the medium and small scale components (buildings, roads, and individual orchards) had changed over the last 50 years, whereas spatial organization, cultural response to natural features, vegetation, and land use patterns had remained intact. This was enough to qualify Fruita as a rural cultural landscape. [114]

In September 1992, Gilbert and McKoy completed a cultural landscape assessment, which established Fruita as a landscape worth protecting. The introduction of this document states:

[T]he emphasis [of this report] is on evaluating the landscape as a system rather than as a series of isolated features. This perspective is fundamental to understanding the landscape on several scales of significance and in assessing the type and degree of change that can occur before integrity is lost. In any cultural landscape some characteristics will carry greater weight and value than others. In an agricultural landscape the presence of large-scale historic relationships, patterns of use, and overall organization are among the most significant characteristics. In this regard, individual structures were considered as one of many types of features, patterns, and relationships that contribute to the overall landscape organization, land use, response to natural features, and cultural traditions. While some aspects of the landscape have changed in Fruita, the large-scale patterns and relationships have a strong degree of integrity and contribute to the historic character, feeling, and association of the district as a whole. It is recommended that this significant cultural landscape be nominated to the National Register of Historic Places as the 'Fruita Rural Historic District.' [115]

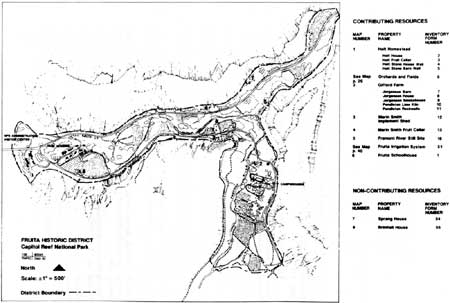

In evaluating the individual features within this rural, agricultural landscape context, Gilbert and McKoy added six eligible resources to O'Bannon's list. These included the Fruita orchards and fields, the irrigation system, and the Holt house and Pendleton lime kiln and stone walls (Fig. 40). [116]

|

| Figure 40. Fruita Rural Historic District, Cultural Landscape Assessment, 1992. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Determining Fruita's eligibility, however, was only the first phase of the cultural landscape evaluation. Next, an extensive cultural landscape report was initiated, to be completed by Gilbert and McKoy by April 1993. This document would identify the character-defining features of the landscape and provide recommendations for ensuring historic integrity of the district during development planning. [117]

Meanwhile, the Determination of Eligibility for the Fruita Rural Historic District was forwarded to the Utah State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) for review. That office concurred with Gilbert and McKoy's assessment and with the determination of eligibility. [118]

During this process, the Utah SHPO wondered whether Fruita really was a "typical Mormon village." [119] The National Park Service asked Dr. Charles Peterson, a highly regarded expert on Utah and Mormon history, for his opinion on the matter. Peterson responded that there were several ways in which Fruita could be called "typical." For instance, the role of the church and the spatial organization at Fruita were different from other rural Mormon towns. However, he also argued that habit, family, and response to environment were equally important qualities of "Mormonness." He also pointed out that geographic constraints limited Fruita's spatial composition, such that typical Mormon patterns of landscape use could not be adopted by settlers. Peterson concluded that Fruita was typically Mormon, without necessarily being a "typical Mormon village." [120] While this was a minor point in determining eligibility, the degree to which Fruita has represented the Mormon culture has been difficult for park managers to ascertain.

In July 1993, Gilbert and McKoy submitted their draft cultural landscape report. While the resource history and the analysis and evaluation of specific features within the landscape report are extremely valuable, the recommendations for future management decisions will no doubt prove the most useful. Gilbert "targeted the landscape report to provide the framework or parameters for making decisions." [121] Among the 60 specific recommendations concerning management concepts, circulation patterns, vegetation, orchards, and structures were the following:

All contributing and thus nominated landscape patterns, relationships and features should be preserved.

The rural character of Fruita should be retained, meaning approximately 60 percent of the 65 acres in agricultural use should be orchards and 40 percent should be open pasture or field.

There should be responsive management of the other resources within the Fruita district -- including natural slopes and cliffs and the riparian community along the stream courses -- with both natural and cultural resource specialists involved in the management of the area.

The campground is an intrusive element which should either be removed or screened. [122]

The orchards and structures of Capitol Reef's most heavily used area had finally been integrated into a long-range proposal for management, interpretation, and protection. For the plan to work, however, managers must view Fruita from the perspective of a holistic, interrelated system in which future National Park Service development respects the spatial integrity of the historic agricultural landscape.

The cultural landscape report, together with the cultural landscape assessment and O'Bannon's historic resource study and survey, have contributed substantially to filling a management void at Capitol Reef National Park. The exhaustive research of primary documents, coupled with the application of new concepts of historic landscape protection and management, provides the background and guidance needed to make educated decisions regarding Fruita's multiple resources.

REFERENCES

Books And Department Of Interior

Documents

Brown, Lenard E. Capitol Reef Historical Survey and Base Map. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 30 June 1969.

Davidson, George E. "Cultural Resource Management Plan, Capitol Reef National Park, Utah." 1983.

______. Red Rock Eden. Torrey, Utah: Capitol Reef Natural History Association, 1986.

"Final Environmental Impact Statement, General Management Plan, Statement of Findings: Capitol Reef National Park." 1982.

Gilbert, Cathy A., and. McKoy, Kathleen L. "Cultural Landscape Assessment: Fruita Rural Historic District, Capitol Reef National Park, Torrey, Utah." 1992.

______. "Cultural Landscape Report: Fruita Rural Historic District, Capitol Reef National Park." Draft prepared for National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Region, July 1993.

"Guidelines for Evaluating and Documenting Rural Historic Landscapes." National Register Bulletin #30.

"Guidelines for Evaluating and Documenting Traditional Cultural Properties." National Register Bulletin #38.

"Historic Agricultural Area Management Plan for Capitol Reef National Park." 1979.

"How to Evaluate and Nominate Designed Historic Landscapes." National Register Bulletin #18.

Melnick, Robert Z., Sponn, Daniel, and Saxe, Emma Jane. Cultural Landscapes: Rural Historic Districts in the National Park System. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1984.

"Natural Resource Management Plan and Finding of No Significant Impact: Capitol Reef National Park." June 1984.

O'Bannon, Patrick W. "Capitol Reef National Park: A Historic Resource Study." Prepared under contract by John Milner Associates, Inc., for the National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Region, June 1992.

"Orchard Management Plan, Capitol Reef National Park." 1988.

'Statement for Management: Capitol Reef National Park." 1984, 1987, 1989.

White, David R. M. "'By Their Fruits Ye Shall Know Them': An Ethnographic Evaluation of Orchard Resources at the Fruita Rural Historic District, Capitol Reef National Park, Utah." Prepared under contract for the National Park Service, Capitol Reef National Park, February 1994.

Newspapers

Deseret News. (Salt Lake City) 4 August 1978, 23 February 1979.

Richfield Reaper. (Richfield, Utah) 4 March 1971, 29 September 1977.

Salt Lake Tribune. 5 June 1966, 25 February 1971, 16 June 1971.

Archives

National Archives - Rocky Mountain Region, Denver, Colorado

Record Group 79: Records of the National Park Service Accessions:

79-60A-354

79-67A-337