|

Capitol Reef

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 15:

MINING AND RELATED ENCROACHMENTS AT CAPITOL REEF NATIONAL PARK

"None of the citizens of Wayne County have become wealthy through the discovery and exploitation of mineral deposits." [1] Thus a local history of the Capitol Reef area sums up mining activities in and around Capitol Reef National Park from initial settlement through the end of the 20th century. Nonetheless, mining did afford some people a living.

Miners were free to pursue their dreams of a mother lode until the National Park Service arrived in 1937, with the creation of Capitol Reef National Monument. Even after the monument and later national park were established, some miners continued to excavate within the boundaries of the supposedly protected lands. In more recent times, the effort continued on an even larger scale as various attempts were made to strip mine coal and tar sands, drill for oil and gas, and build coal-burning power plants.

While long-term impacts from mining at Capitol Reef have been relatively limited, this fact is attributable more to a lack of success than to a lack of trying: local mines were just marginally successful. If the economic climate changes, making the local low-grade ores and deposits more valuable, there will no doubt be renewed attempts to harvest the mineral resources on lands surrounding Capitol Reef National Park.

The history of mining and encroachments at Capitol Reef can be broken down into four distinct phases: 1) the early, largely unsuccessful search for precious metals, "that myth of easy money" [2]; 2) the uranium boom of the 1950s; 3) mining in the expanded monument and later national park; and 4) recent large-scale encroachments from oil and gas exploration, coal strip mines, and power plants.

The Early Search For El Dorado

The structural geology necessary for large deposits of valuable oil, gas, or minerals is generally absent from the Waterpocket Fold country. This, however, did not stop early pioneering prospectors from viewing the varied, colorful rock layers as untapped potential. After all, in a land that is little else but rock, there must be some kind of riches to be had.

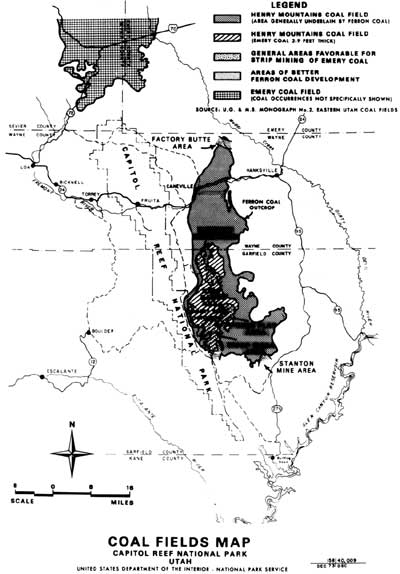

The scientific surveys toward the end of the 19th century were the first to describe the scenery and resources of the area. They concluded that hundreds of millions of years of sedimentary geology had been warped and then punctured with later plutonic upthrusts to form the rock layers found in south-central Utah. The numerous exposed sedimentary and volcanic strata were bound to hold a little bit of everything. Observed valuable minerals included copper, uranium, gypsum, silver, and gold. Several deposits of coal were also noted. Oil seeps were found near the mouth of the Escalante River, charging speculation that oil and gas would be found in some of the uplifted country surrounding the Waterpocket Fold. Virtually every report, however, predicted that only coal would be found in any abundance. [3]

Regardless of these studies, adventurous prospectors came to see what might lie in the rocks, streams, and sandbars. Reports of prospectors searching in the Henry Mountains, in the Colorado River canyons, and along the Waterpocket Fold date to the 1870s. [4] The first known prospectors through the Capitol Reef area were J. A. Call and Walter Bateman, who carved their names and the date September 20, 1871 just west of the Capitol Gorge narrows. These two men, presumably on their way to the Colorado River or Henry Mountains in search of gold, were representative of the fortune hunters who pre-dated permanent settlement of the area by a decade. [5]

By 1883, Cass Hite discovered fine traces of gold in the sandbars of the Colorado River within Glen Canyon. Hite's findings sparked a minor rush into one of the most remote and rugged areas of the country. With several hundred prospectors congregating in the isolated, lawless area, some of the first arrivals set up their own mining district to create order and establish the legitimacy of their own claims. This Henry Mountain Mining District, formed by nine men on December 3, 1883, set boundaries and mining law:

The boundaries of the district followed the Colorado from the mouth of the Dirty Devil to Halls Crossing, thence along the Waterpocket Fold to the "Big Sandy" (Fremont River), thence to the Dirty Devil, and thence to its mouth. The regulations specified the amount of 'discovery work' to hold a claim; qualifications for membership in the district were set out; penalties for 'claim jumping' and 'other fraudulent dishonorable conduct' were specified; rules for making amendments were given. [6]

These first mining regulations in the area showed these miners to be little different from those of earlier gold rushes. The Glen Canyon miners observed the federal mining laws of 1866 and 1872 and then added their own local rules to fit the existing conditions. [7] While the Glen Canyon gold rush had several peaks and valleys, the most activity took place between 1886 and 1889. Virtually every canyon opening and sand bar was explored and placer mined, some with remarkable but short-lived success. A sand bar named the "California," for example yielded almost $10,000 of gold. But most gold was too fine to be recovered by contemporary technology, and many miners left in frustration. One product of this gold rush, however, was the development of supply roads into the area, including the upgrade of the cattle trail down the east side of the Waterpocket Fold, and the establishment of a miner's trading station at Hanksville in 1884. [8]

Although the flour-like consistency of the sandbar gold suggested that the mineral had been washed a long distance downstream, miners combed the nearby Henry Mountains in search of the mother lode. [9] By 1890, Jack Sumner, who had been with John Wesley Powell on the 1869 expedition through the Grand Canyon, and his partner J. W. Wilson, found a fissure of gold at the head of Crescent Creek on the east side of Mount Ellen. They named their mine the Bromide, because of the ore's similarity to bromide ore Sumner had seen in Colorado. A five-stamp mill was erected on the site to pulverize the rock and separate the ore. It would not be long before the boom town of Eagle City was erected just down the hill. But despite the excitement, the mine and town quickly played out:

Besides a dozen homes [Eagle City] had a hotel, two saloons, a dance hall, three stores, and a post office. The Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad made preliminary surveys of a route from the main line at Green River to Eagle City in anticipation of building a branch line when the mines could produce 100 tons of ore daily. But most of the prospects proved too small. The Bromide fissure paid well for a short time but the gold was confined to a pocket and the mine could no longer sustain the town. By 1900 Eagle City had become a ghost town and today a single lone cabin marks the site. [10]

A few other attempts were made to extract gold from the Henry Mountains and the Colorado and San Juan Rivers during the 1890s. The most notable was Robert B. Stanton's failed Hoskinini Company dredging operation near the mouth of Bullfrog Creek. The gold continued to be either too fine or scarce and the harsh, isolated landscape persuaded most prospectors to venture elsewhere in the search for the mythical mountain of gold. [11]

Other Early Attempts At Mining The Waterpocket

Fold Country

Closer to Capitol Reef, copper and oil exploration occurred on the modern park boundaries through the 1920s. Southwest of Fruita is the uplift known as Miners Mountain. While it is unclear who named it this, the name probably was derived from several copper and lead deposits discovered on its exposed southeastern flanks. A geologist's report in 1920 noted, "For many years intermittent prospecting for copper has been carried on, and a few hundred pounds of high-grade ore is reported to have been shipped....In the development of the deposits several shafts have been sunk to depths of 30 to 50 feet and short tunnels have been driven." [12]

Unfortunately, little else is known about who discovered the deposits or when the last ore was mined on Miners Mountain. By 1963, these mines were reported to be "chiefly caved and inaccessible" with no evidence of recent copper production. Although the copper deposits, located in the Sinbad Limestone, were regarded as colorful, the deposits were small and the copper content of the rock was low. [13]

Nearby, less valuable but more practical limestone was quarried. The stone was excavated either from the vicinity of Grand Wash or up Sulphur Creek west of the modern visitor center, broken into small slabs, and heated at high temperatures in the lime kilns located on Sulphur Creek and near the present Fruita campground. In this way the limestone was converted to powdered calcium oxide for use in mortar, plaster, and whitewash. Another reported use was as an insecticide on the Fruita orchards. The lime kilns were active in the Fruita area from about the 1890s to 1930s, when they were last used to make mortar for the Caineville school. How much limestone was actually used and the specific locations in which it was mined are unknown. [14]

About 25 miles south, on the northwestern base of Wagon Box Mesa, there was a pioneering attempt to drill for oil during 1920-21. The Ohio Oil Company hauled the derrick, and associated equipment by truck up to the extremely isolated site by way of the old Halls Crossing road through Silver Falls Canyon. Supplies were also driven down from Notom through the mouth of Muley Twist Canyon and up the steep switchbacks of that Halls Crossing road to the drilling site. This operation was a source of great curiosity to the sleepy ranch town of Boulder, and several parties of sightseers ventured out to see the drilling progress. At reaching a depth of over 3,200 feet, the hole was abandoned on Nov. 9, 1921 for lack of oil. [15] Another drilling operation near North Caineville Mesa the following year also yielded little. [16]

Uranium and coal mining, which would later prove to be the most significant threats to national park lands in the area, also occurred on a limited scale during the early 20th century. Coal was first used for heating boilers at gold mining camps on the Colorado River. Then, about 1908, a coal mine was carved out of the badlands around Factory Butte, east of the Waterpocket Fold. [17] This mine produced relatively small amounts of coal needed for local domestic uses. The area's large coal deposits would not become a significant concern for many more decades.

Uranium, on the other hand, has always been the most marketable mineral found within the Waterpocket Fold country. The most historically significant uranium mining operation in the monument was the Oyler Mine at the head of Grand Wash, approximately two miles south of Fruita. First filed on in late 1901 by Thomas Pritchett and H. J. McClellan, the site was initially called the Nightingale Mining Claim. In early 1902, the "Little Jonnie" claim was filed in virtually the same spot by Torrey residents Willard Pace and James and Allen Russell. Gold, silver, and copper were listed as the minerals they were hoping to find. Then on Jan. 1, 1904, Thomas E. Nixon and Jack Sumner (the same Sumner of Powell Expedition and Bromide Mine fame) filed on the same spot. They dug two tunnels into the sandstone and apparently extracted a little ore. Nixon and Sumner may also have begun the unfinished building near the entrance of the mine. Nixon kept title to this claim until 1911, when he sold part to Jacob Young and T. J. Jukes. Then the claim apparently lapsed. M. V. "Tine" Oyler of Fruita was next to file on the claim, which he did on Jan. 1, 1913. From then until 1937, the area around the Oyler Mine was filed on no fewer than 75 times. [18]

The history of the Oyler Mine is complex and fraught with legal disputes between claimants and the various federal agencies, including the National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, and the Atomic Energy Commission. Since the mine's history has been previously examined in detail by historians Lenard Brown and Patrick O'Bannon, it will only be briefly addressed here. Instead, some of the other uranium prospects found throughout Capitol Reef National Park, previously overlooked due to the concentration on the Oyler Mine, will be explored.

When establishment of Capitol Reef National Monument was proposed in the early 1930s, there had been a few, mostly unsuccessful attempts to mine in the Waterpocket Fold country. Sporadic efforts to extract gold, oil, copper, and uranium had shown that, while many different minerals occur in the area, few existed in quantities that would make the backbreaking labor of mining worthwhile.

At this time, however, the federal government actually encouraged mineral exploration on public lands. There was little regulation of mining, other than the 1872 Mining Law that was intended to standardize claims, rights, and the amount of work necessary to avoid forfeiture. Thus, as time went on, even national parks and monuments were not exempt from mining claims.

The Start of the Uranium Boom

During the early 1950s, Capitol Reef National Monument was opened to the uranium frenzy sweeping the Colorado Plateau. After development of the atom bomb and the resulting nuclear arms race, the Atomic Energy Commission had wartime-like powers over the federal land-use agencies such as the National Park Service. Spurred by price supports, thousands of ill-equipped, would-be prospectors flooded the area with their scintillators and Geiger counters in search of radioactive uranium. Mining claims that had previously been invalidated with the creation of the monument in 1937 were reclaimed, updated, or both. Shafts were dug or dynamited, and miles of road were cut, even into the sheer sides of cliffs. Over 10,000 claims were filed on adjoining lands, which later were included within the present national park boundaries. The only protection the monument had was its one-man staff: Charles Kelly.

Oil Drilling Sites Dot The Landscape

Besides uranium, oil prospects were the only other recorded mining activity throughout the early years of Capitol Reef National Monument. About 20-30 miles north of the monument in Emery County, several test holes were drilled in the late 1940s' Last Chance oil and gas fields. While the gas finds were fairly significant, the few oil stains discovered were not. [19] In early 1949, Monument Custodian Charles Kelly reported that another prospective oil well was to be drilled "a short distance north of the monument boundary." To access this site (presumably the abandoned drill hole on Little Sand Flats), Kelly heard, a road was to be built up the cliff behind Chimney Rock, into the head of Spring Canyon, and then north through a branch of Spring Canyon to the site. [20] The road was never built, and the park has no record documenting why the oil company abandoned the idea.

In 1951, a small section of road was proposed in the southwestern section of the monument to gain access to an oil drilling site on state land south of Sleeping Rainbow Ranch on Pleasant Creek. Again, there is no record as to how this was resolved, or if any drilling actually occurred. [21] That same year, the Hunt Oil Company of Dallas, Texas began its search for oil in the area. Throughout the early 1950s, the Hunt Oil Company drilled several test holes in the Circle Cliffs area and placed a scattering of drill sites in the Tantalus Flat area west of the monument. The Standard Oil Company also proposed to drill an oil well south of Notom. Again, there was little to show for all this effort. [22]

Uranium In The Waterpocket Fold

Although abandoned oil drill holes dotted the landscape during the 1950s, the uranium boom, occurring at the same time, was by far the most significant mining activity in Capitol Reef. Before delving into uranium mining within the monument, however, it is important to briefly discuss where the uranium was potentially located. [23]

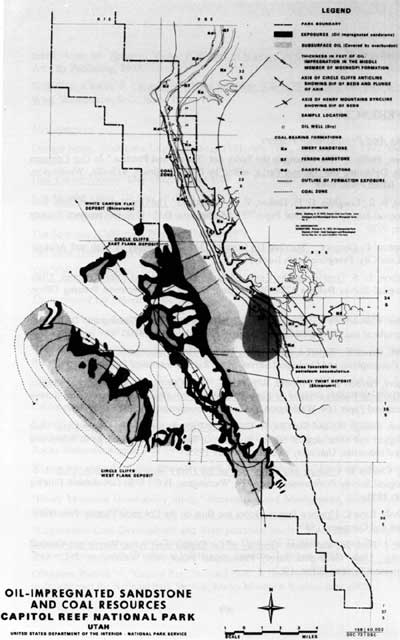

In the Waterpocket Fold country, uranium is usually found in two sedimentary layers. The one most often exposed at Capitol Reef is the Shinarump, lowest member of the Chinle Formation. Most of the uranium in this stratum lies near the contact between the Shinarump and the underlying Moenkopi mudstones. The Shinarump is a coarse sandstone and conglomerate mixture laid down by a massive river drainage system over 200 million years ago. The plant material trapped along those ancient river channels would become the primary component of uranium. When the Waterpocket Fold was uplifted and eroded eons later, the Shinarump was exposed in discontinuous outcroppings all along the western side of the Waterpocket Fold. [24]

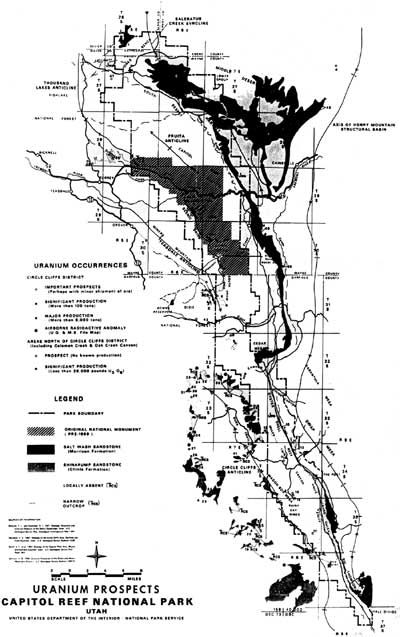

The second stratum with locally high concentrations of uranium, the Salt Wash member of the Morrison Formation, is exposed in several spots along the eastern side of the Fold (Fig. 41). [25]

These exposures constitute almost 60 linear miles of radioactive materials, which made the Capitol Reef region particularly susceptible to the uranium boom. However, concentrations of high-grade ore were minimal in this region, and transportation costs were so high that only relatively small amounts of ore were ever taken from either the monument or later park lands. Uranium mining did provide some local people with an income, but it did not make them rich.

|

| Figure 41. Shinarump channels and uranium mining claims. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Uranium Boom Comes To Capitol

Reef

While the Oyler Mine was obviously the most significant claim within the new national monument boundaries, there were seven other claims in the mining record books as of 1941. None of these, including the Oyler Mine, was even taken into consideration when Roger Toll made his initial monument investigation in 1932. In Preston Patraw's 1935 report, he noted briefly that "previous research [had] failed to reveal the presence of minerals of sufficient quantity for commercial exploitation." [26]

In 1941, the National Park Service asked the General Land Office to investigate the validity of the eight unpatented mining claims within the new national monument. Walter Koch, sent to investigate, reported that "the land was non-mineral in character and no minerals had been found within the claims in sufficient quantity to constitute a valid discovery." [27] General Land Office Commissioner Fred. W. Johnson concurred with Koch's conclusions and canceled every claim in the monument on Nov. 25, 1941. Notices were sent to all claimants informing them of this decision and specifically stating that all protests to this action must be received in writing within 30 days by the General Land Office in Salt Lake City. A final decision was delayed until October 1942 because several claimants could not be contacted by registered mail. On October 7, 1942, the General Land Office Commissioner, having followed the required procedures, declared all claims within Capitol Reef National Monument null and void. [28]

This decision to place all monument lands off-limits to mining was not questioned until the beginning of the uranium boom in 1948. Perceived threats to national security enabled the recently created Atomic Energy Commission to sponsor the "first federally-controlled, federally-promoted and federally-supported" mining boom in the nation's history. The unique geology, exposed rock, and enormous amount of unclaimed public domain made the Colorado Plateau an appealing target for modern day 49-ers. [29]

Activity within Capitol Reef National Monument began almost immediately. On June 15, 1949, Willard Christensen appealed the 1942 decision of the General Land Office canceling claim to the Oyler Mine site. Christensen argued that he and his partners had tried to appeal the judgment orally immediately after their claim was voided, but were never directed to the correct GLO authority. The problems with Christensen's complaints were, first, that he did not follow the GLO's clearly stated appeals procedure, and second, that he renewed his interest in the claim only after uranium price supports had been announced by the Atomic Energy Commission. In March 1950, officials in the Interior Department refused Christensen's request for a hearing. [30]

One month earlier, Emma Osborn of Torrey argued that she was legal claimant to the Oyler Mine because her late father had worked the mine back in 1905. Christensen and Osborn were just the first of more than two dozen hopefuls who attempted to file claim on the long-abandoned mine tunnels. From this point on, the conflicting claims to the Oyler Mine were played out in court, the federal bureaucracy, and the newspapers. The legal maneuvering effectively prevented the site from being mined by anyone. Ironically, mining was not permitted at the Oyler Mine and the 80 acres surrounding it, said to have the highest concentration of uranium in the area, during the entire boom period. Nevertheless, the publicity generated by the mine's controversy and supposed riches brought the monument's uranium potential to the attention of both prospectors and, more importantly, the Atomic Energy Commission. [31]

Mining Within The Monument: 1950-1954

At first, the uranium boom at Capitol Reef consisted of the work of a few scattered prospectors. In the first "Superintendent's Monthly Narrative Report" since the monument's official activation in May 1950, Acting Superintendent Charles Kelly observed, "Uranium prospectors continue to pass through. Some are courteous enough to ask about regulations, but most are belligerent when told they cannot mine in the monument." [32]

Throughout the rest of the year, particularly over the summer, Kelly busily fended off probing prospectors. For the most part, the search for uranium in the Waterpocket Fold country was a seasonal occupation: with the coming of winter, most prospectors were eager to leave behind the rugged dirt roads and extreme isolation of the area. [33]

Activity at Capitol Reef heated up once again the following spring. On May 9, 1951, Willard Christensen and his partners, H. O. Barney and J. R. Hoffman, began camping near the Oyler Mine. They told Kelly that they would begin mining as soon as their equipment arrived. In what was undoubtedly a heated discussion, Kelly told the claimants there would be no mining within the monument. The three, however, continued to camp on the site, exploring the area with their Geiger counters. Their presence in the area activated the rumor mill, attracting dozens of local prospectors to try to stake their own finds. Claims were filed at the mouth of Capitol Gorge and in the vicinity of Twin Rocks and Chimney Rock. "No damage has been done in those areas as yet," Kelly reported, adding wryly, "It appears that all known and reported deposits of uranium ore occur in the most scenic and most accessible parts of the monument." [34]

Rumor that the monument was open to mining no doubt was based on the ongoing negotiations between the National Park Service and the Atomic Energy Commission to do just that. In the AEC's 1951 request to open the monument up to uranium mining, Commissioner Gordon Dean wrote Secretary of the Interior Oscar Chapman, "The grade of uranium-bearing material in the vicinity of the 'Oiler Tunnel' is such as to cause us to believe, in light of our experience with development of similar deposits elsewhere, that appropriate work in this area might disclose an important uranium deposit. In addition we believe thorough prospecting and exploration of the favorable formations in this area may disclose similar deposits." [35]

In February 1952, a special-use permit governing uranium mining within the monument was agreed upon. The AEC promised to obtain National Park Service permission before any ore was taken, and to build only the roads, trails, and buildings absolutely necessary for uranium extraction. Further, the AEC would pay 10 percent of any mining profit to the National Park Service. When the seven years of the permit were over, the AEC would remove the buildings and cover the mine shafts. [36]

In May 1952, Capitol Reef National Monument was officially opened to uranium prospectors. Ranger Rudy Lueck was dispatched from Zion National Park to help Kelly with the expected rush. This rush, however, never materialized. Mostly due to confusion over the conflicting claims to the Oyler Mine area, the process of recording claims within the monument was delayed until July. Only about a dozen people bothered to file claims on lands outside the restricted Oyler section. This lack of interest, coupled with the discouraging findings by some Atomic Energy Commission investigators from the area office in Grand Junction, led Superintendent Kelly to hope that uranium mining would incur little damage to the monument, after all. [37]

By February 1953, the initial permit confusion had been resolved, and 35 mining permits for claims within the national monument were issued by the Atomic Energy Commission. On Feb. 21, one day after the opening date, only 11 claimants had registered with the monument. Kelly reported that those who did come found little:

More than half the prospectors left within 24 hours. Five claims have been staked, but the locators are not very enthusiastic over their value. One group brought in a small plane and flew over the monument for two days with a Geiger counter but found nothing exciting. Other prospectors may show up late, when the weather becomes warmer, but present indications are that the 'rush' is over and that prospecting will present no future problem. The work done so far indicates that there are no great hidden deposits of uranium in this area. [38]

Kelly also noted that there had been no activity in the reserved area around the Oyler Mine and that all permit holders had been "courteous and cooperative."

Throughout the rest of 1953, prospectors continued to pass through the area. A few filed claims, including Lurton Knee on land near his Pleasant Creek Ranch, and a couple did a little digging. The Atomic Energy Commission sent C. E. Collins to investigate the area's potential and assign permits as needed. Although he found nothing worth mining, Collins nonetheless issued several permits. The resulting piecemeal digging was soon having a noticeably adverse effect on the landscape. [39]

In June 1953, Kelly complained to the Atomic Energy Commission office in Grand Junction about its indiscriminate issue of permits. Ray Lindbloom was sent to investigate, touring the monument with Kelly to see all the various shafts and tunnels. Kelly reported, "He finally agreed that under conditions existing here, no mining contracts should ever have been issued, and promised that no more [would] be issued without proof of commercial values....The AEC has been asked to cooperate more closely with this office in the future." [40] By 1954, the uranium boom on the Colorado Plateau was at its peak. Historian Ringholtz describes the impacts:

The AEC had turned the tap and engendered a flood. To spur exploration by individual prospectors and mining companies, the Commission averaged one-million feet of test drilling per year. They paid out over $3,725,000 in bonuses. They tamed the Plateau with 993 miles of access roads. The Grand Junction office received more than three thousand visitors and processed an excess of six thousand pieces of mail each month. AEC geologists assured the inquirers that thousands of square miles on the Colorado Plateau remained to be explored. [41]

While most of this activity was east, north, and west of the Waterpocket Fold country, there would be a certain amount of spillover. Soon, a new front was opened in the Circle Cliffs area to the south of the monument. Charles Kelly provided an excellent, albeit somewhat embellished, account of the uranium boom in the Circle Cliffs during 1954. He wrote, "Nearly every man woman and child in Wayne county has been out prospecting. The local banker locked up the bank, the barber shop and several stores closed up while the proprietors prospected. Since their congregations were out in the field on Sundays, some of the bishops closed up the ward houses to go prospecting." Further, Kelly claimed, the Hunt Oil Company was then in the process of locating a thousand claims on the basis of "one claim where two men worked 20 days, took out a pickup load of ore, hauled it to Salt Lake City and sold it for $11.00." [42]

This mostly speculative filing of uranium claims on virtually every square inch of the eastern escarpment of the Circle Cliffs would have repercussions for Capitol Reef's management after the monument's expansion in 1969. Another significant result of the Circle Cliffs boom was the blasting of the Burr Trail road up the steep, boulder-strewn slope between Upper and Lower Muley Twist Canyons. Once a cow-track, this AEC road would become a primary route for ore trucks hauling samples to the uranium processing plants in Moab and Marysville, Utah. The road through Long Canyon was also improved so that, for the first time, there was a vehicle route connecting Boulder, the Circle Cliffs, and the Waterpocket Fold. [43]

Closer to the monument, uranium strikes were reported in the Caineville Wash area, the Temple Mountain area, and north of Hanksville at the rich Delta Mine, claimed by Vern Pick. [44] Kelly also recorded that several core samples were taken from Sheets Gulch, south of the monument border. Construction on a small ore-processing plant was also begun at Notom, but it never became operational. [45]

Within the monument itself, mining activity picked up again in 1954. In February, a road was graded on a state-owned section up into the Chinle on the south side of Grand Wash (opposite the Oyler Mine). [46] By the end of the summer, however, it appeared that the boom was over for good. All new claims were reported to be abandoned, and the AEC refused to investigate any new finds because all previous showings had been so poor. Due to this lack of viable discoveries, Kelly appealed to his superiors and the AEC that the monument be closed to further mining. He wrote in October 1954, "The whole area has been carefully examined and most of it staked, but no commercial deposits have been found. It is therefore recommended that Capitol Reef National Monument be closed to further prospecting as of Feb. 20, 1955." [47]

In May 1955, unlimited prospecting permits within Capitol Reef National Monument were finally stopped. Existing valid permits were given one year renewals. All other prospecting within the monument was effectively over by May 1956. [48]

The End Of The Boom: 1955-1964

In June 1955, just as it seemed the mining threat within the monument was over, the BLM had validated claims by Willard Christensen and his partners to two mines immediately south of the Oyler Mine. It appears that the claimants had filed on these locations when they filed on the Oyler Mine, but somehow the Yellow Joe and Yellow Canary claims had been overlooked during the nullification process in 1941-42. Because of the oversight, the BLM had to validate them.

The National Park Service immediately attempted to purchase the claims through condemnation before the area was spoiled. Christensen and his partners, not to be foiled again, proceeded to build a road and blast large areas within the claims. Once the landscape had been scarred, the National Park Service abandoned its condemnation proceedings. [49]

From 1955 through the early 1960s, the partners, under the name La Fortuna Mining Company, periodically worked their Yellow Canary mine as the National Park Service continued to appeal the claim's validity. The majority of this work was done in 1955-56, during which some 277 tons of uranium ore were "unprofitably sold to the Atomic Energy Commission." [50] In 1964, the Secretary of the Interior finally declared the Yellow Joe and Yellow Canary claims permanently null and void. In 1967, the National Park Service finally took possession of the mine and began site restoration. [51]

Meanwhile, legal battles surrounding the Oyler Mine continued. In 1958, in a last attempt to gain access to the mine's supposed riches, Cora Oyler Smith (daughter of the Oylers for whom the mine is named) filed a petition with the BLM to claim the mine on the basis of a technicality. The initials of her mother's name had been typed incorrectly on the original nullification notice from the General Land Office; therefore, Smith argued, she had never been legally notified and her claim remained valid. This claim was soon dismissed along with all other claims to the area, and the Oyler Mine reverted to National Park Service care. [52]

In February 1959, when the Atomic Energy Commission's special-use permits expired, the uranium boom at Capitol Reef National Monument finally ended. As stipulated by that permit, the AEC requested from the National Park Service a bill for the amount necessary to repair the residual mining scars left on the monument's landscape. The amount came to $13,500, but a ruling by the Comptroller General in June 1959 barred payments between federal agencies. The National Park Service, therefore, paid for the restoration, completing a minimum amount of work at abandoned sites in July. [53]

In the end, although there had been a great deal of excitement, a few holes dug, and several roads made, little ore was actually taken from Capitol Reef National Monument. In a 1969 interview, Charles Kelly recalled that the 10 percent royalty the National Park Service was to receive from all ore removed amounted to a total of $13.50. [54] As for the real wealth of the Oyler Mine, later measurements of radioactivity indicated that it contained only a small amount of ore worth mining. [55] It certainly would never have yielded as much as mines elsewhere on the Colorado Plateau.

Thus, the significance of the uranium boom at Capitol Reef was not the amount of ore extracted from the monument, but the fact that mining was allowed at all. In the 1950s, at the height of the Cold War, national security and mining boom hysteria combined to open up a national monument to mining where all claims had been previously nullified.

Uranium and Capitol Reef During the 1960s

Beginning in the mid-1960s, a second uranium boom hit the Colorado Plateau. The building of the first nuclear power plants once again brought adventurous prospectors into southern Utah looking for their fortune. By this time, of course, the more significant concentrations of uranium in the region had already been claimed and usually were owned by large corporations. Any new finds would most likely require a large investment of time and money before any profits would be made. [56] This situation did not, however, prevent numerous, largely speculative claims from being filed by companies and individual miners. With Capitol Reef closed to mining, most of the prospectors in the Waterpocket Fold country concentrated on the areas south of the monument. Most of the exploration centered in the Circle Cliffs and along the eastern side of the Fold. This renewed mining activity would prove troubling after 1969 when Capitol Reef National Monument was expanded to include almost the entire Waterpocket Fold. [57]

Within the old monument, the Yellow Canary claim was repossessed by the National Park Service in 1967. A Secretary of the Interior decision on May 4, 1964 declared the Yellow Canary claim invalid because "it is not shown as a present fact that the land is mineral in character and is valuable for its mineral content." [58] Not until April 1967 did Acting Superintendent Grant Clark finally receive long-awaited word that all previous and/or pending mining claims within the national monument had been declared null and void. [59] In September, the La Fortuna Mining Company was officially notified that the Yellow Canary claim had been nullified and that all buildings and equipment were to be removed within 90 days. On Nov. 20, the 90 days were up, and no one had come to claim either the small shack or related equipment. Rangers Bert Speed and Grant Clark took possession and inventoried the property. [60] The building was later removed, the mine shafts covered over, and the area restored as nearly as possible to its natural condition. [61] By the 1990s, the last scars of the uranium boom within the old monument boundaries were all but gone.

1969 Monument Expansion

On Jan. 20, 1969, Capitol Reef National Monument was expanded by presidential proclamation to more than 600 percent of its previous size. [62] This expansion not only brought most of the spectacularly scenic Waterpocket Fold into the national park system, but also reeled in a reported 11,000 mining claims, 26,000 acres of oil and gas leases, and 1,760 pending applications for coal prospecting. [63]

The presidential proclamation did not specifically address mining within the expanded monument, except to make the standard stipulation that the federal government recognized "valid, existing rights." [64] This meant that while there would be no future mining claims allowed, all valid, existing mining claims and leases could legally be worked. All current and future leases on state lands were also beyond the jurisdiction of the National Park Service. National Park Service management of these valid, existing claims, and state-owned sections within Capitol Reef was limited to controlling access to the claims that were reached by crossing monument lands. The National Park Service could only hope that most of these claims had not been actively worked so that they would soon be declared abandoned, null, and void. [65]

At first, little could be done about all these claims. The small staff assigned to the old monument lands was inadequate to monitor more than 250,000 acres of rugged, unfamiliar country. Ability to protect the new lands was also hampered by the outspoken negative reaction from the local communities and the belief that the boundaries would soon be adjusted. The fact that new boundary signs were not posted until a year later compounded confusion and difficulties of controlling mining on the new monument lands. [66]

Mining was not a primary issue during the 1970-71 debate over the boundaries and provisions of a Capitol Reef National Park. Since past mining had proven disappointing, and as future issues such as tar sands and coal were still in the speculative phase, the immediate concerns over grazing consumed the vast majority of National Park Service and congressional attention. [67] Periodic attempts to gain access to previous claims within the new monument and (after December 1971) Capitol Reef National Park, however, had a significant effect on park management concerns.

The Tappan Claims

South of Oak Creek, in the central Waterpocket Fold, are two large box canyons called North and South Coleman Canyons. The entrances to these canyons are extremely narrow, but they soon open up to expose many of the colorful sedimentary layers of the Waterpocket Fold country. Among those exposed layers is a small outcropping of the Shinarump/Moenkopi contact.

Geologist Fred Smith led a survey party to the area in the early 1950s as part of an investigation for the Atomic Energy Commission. While they mention the Shinarump outcroppings within both canyons, the geologists implied that the radioactivity readings were insignificant, and that no uranium was found. [68] These findings did little to discourage local uranium prospectors. Beginning sometime around 1954, Caineville native Evangeline Tappan and her husband, John, began filing over 90 claims in both North and South Coleman Canyons. A crude road was constructed to the entrance of the North Coleman Canyon and a 76-foot-long adit, or slanted mining shaft, was dug into its upper end. Several buildings used to house workers and equipment were also built inside the canyon. No records have been located documenting the amount of ore removed or whether any of it was ever sold. [69]

When the monument was expanded in 1969, these canyons were brought into the national park system. Then, after years of inactivity on the site, Mrs. Tappan wrote Capitol Reef in late 1971 asking if her claim was still valid. Acting Superintendent Bert Speed evidently could not answer her question. He told her, though, that if the claim were valid she could mine it and even build a road -- so long as the National Park Service was consulted prior to construction. [70]

Mrs. Tappan took this letter as permission not only to mine, but to build the road. In July 1972, when Speed went to investigate reports of a road being built into North Coleman Canyon, he encountered blasting in progress. He advised the workers that dynamiting required a permit, though he saw no reason to prohibit the use of a front-end loader to clear out the debris. Speed's rather tolerant response to this matter suggests that he assumed at least some of Tappan's claims to be valid. [71]

When news of the road-building reached the regional office, NPS staff there demanded an immediate investigation into the validity of the Tappan claims. [72] This is all rather confusing, since a validity examination had already been completed by National Park Service Mining Engineer Robert O'Brien back in March 1972. O'Brien had concluded that there was no valid discovery of minerals on any of the unpatented claims in North Coleman Canyon. [73] This report could have been used to halt road construction before blasting began, but for some reason it was not. At the end of July, however, the National Park Service obtained a restraining order to stop the blasting and road building. After several years of hearings, the Interior Board of Land Appeals ruled on May 5, 1975 that no valuable mineral deposit had been found as of January 20, 1969 (the date the land was withdrawn into the National Park Service), thus making the claims null and void. [74]

This ruling only seemed to increase the determination of Mrs. Tappan. Being a prominent citizen of Wayne County as well as a local contributor to the Salt Lake City newspaper, The Deseret News, she knew how to appeal her case. She wrote to Utah Senators Jake Garn and Frank Moss. She also tried to persuade the National Park Service that all the time and effort she and her family had put into the Tappan claims over the years should be reimbursable. All these efforts produced a great amount of correspondence, but did not change the final decision nullifying the claims. To the end, Evangeline Tappan remained bitter toward the National Park Service for taking her claims. In a 1981 interview with former Chief of Interpretation George Davidson, she continued to argue that there was a good deal of money in the Coleman Canyons that was just being washed away. [75]

Rainy Day Mines

Located about four miles south of the Burr Trail, the Rainy Day mines have produced more uranium than all other areas within the present park boundaries combined. Geologist E. S. Davidson reported, "The Black Widow, Hotshot, Yellow Jacket, and Stud Horse prospects and the Rainy Day mine are the only workings in the Circle Cliffs district from which more than a few truckloads of ore had been shipped as of 1956; the Rainy Day mine had produced more than 75 percent of the total." [76]

The Rainy Day Mines are a series of approximately 25 claims first filed in 1954 by Leo D. Jackson, Blaine Albrecht, and Rutherford Tanner. The last time that the mines were used extensively was probably sometime in the mid- to late 1960s, since that is the latest date found on magazines located in associated buildings. [77] By the time the area was incorporated into Capitol Reef National Park in 1971, there were 12 adits up to 1,800 feet long, two wooden buildings, a large trash dump, a holding pond, and numerous improvements, all served by four miles of dirt road from the top of the Burr Trail switchbacks. Reportedly, over 8,000 tons of ore had been removed from the area. [78] Significantly larger than any mining operation on the old monument lands, this mine would require a good deal of attention in the years ahead.

In the fall of 1972, Leo Jackson leased assessment work to Virgil Adams in return for profits once the mine became active again. Adams used a grader to improve the access road but decided to delay actual drilling since there was no market at the time. Apparently, the assessment work was only being done to keep title to the claims until increasing uranium prices made the Rainy Day profitable. Even so, Leo Jackson seemed resigned to the mine's apparent lack of potential. National Park Service Mining Engineer Harold Ellingson recalled that Jackson's parting comment to him after a September 1972 interview was that "all he wanted was some money for his claims in order to keep his wife from leaving him." [79] By this time, however, the slow pace of nuclear fueled power plants and the ready supply of uranium from elsewhere had made it economically unfeasible to mine the meager sources in the Waterpocket Fold country. Jackson and the others would never get the chance either to extract ore from the mines or sell them. The next uranium boom never came.

By 1976, the National Park Service had asked Bureau of Land Management officials to declare the Rainy Day claims null and void. [80] Then, at the end of 1978, someone performed unspecified assessment work on the mines without a plan of operations, which was by then required. Superintendent Derek Hambly notified Jackson and the other owners to stop all work until such a plan had been approved. [81] On March 24, 1981, the Interior Board of Land Appeals ruled that 31 claims associated with the Rainy Day Mines were invalid due to lack of discovery of any significant ores. This decision, however, did validate two claims: Rainy Day Group 1, claims 2 and 3. [82] These two claims were the only mines to be validated out of the over 11,000 claims within Capitol Reef National Park when it was created.

In September 1981 Leo Jackson notified Hambly, as required by the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, that he intended to hold onto these claims but had no plans to begin mining. By 1984, however, Jackson and the other owners of the Rainy Day evidently had given up hope of ever mining the area again, as they did not file required notices of intention in either 1984 or 1985. In obvious relief, the National Park Service moved quickly to terminate these last remaining claims within the park. There is no record of attempts to halt these proceedings. By the end of 1986, the Rainy Day claims were declared null and void. [83]

The Rainy Day Mines were the most productive mines now within Capitol Reef National Monument. They also left the biggest scars. In 1993, the buildings were torn down, debris was placed in the mine tunnels, and the adits were blocked as part of a Utah Division of Oil, Gas, and Mining program to reclaim old mines. An initial $31,600 was allocated for this purpose, with additional money requested to naturalize and revegetate the access road as well. [84]

The Tappan and Rainy Day claims are two of 17 significant mine sites that were incorporated into Capitol Reef National Park. Several of these other sites are documented in the Historic and Active Superintendent's Files at Capitol Reef headquarters in Fruita. Examination of these files and the history of the uranium boom verifies that no one made it rich from this modern search for El Dorado, at least in the Waterpocket Fold country. Nevertheless, despite overwhelming scientific evidence and previous limited success, the search continues to the present day. It is difficult for some to realize that Capitol Reef's riches lie not in mere minerals, but in the sweeping grandeur of its geology, the color and texture of its strata. It is this wealth of scenery that now brings millions of visitors -- and their pocketbooks -- to the region.

The Bird Flagstone Mine

Actually, it was the color and texture of the rock just west of the visitor center that brought about one of the most controversial but short-lived mining conflicts within Capitol Reef. In 1964, Clair Bird obtained a commercial operations lease on State Section 16, Township 29 South Range 6 East, and a mineral lease on the northeast corner of the same section. [85]

The focus of Bird's mineral lease was not uranium, but rather, the deep red ripple rock occurring in large, horizontal layers in the Moenkopi Formation. Remnants of ancient stream beds and mud flats, this ripple rock resembles textured flagstone used in construction. The ripple rock within Capitol Reef had been quarried on a limited scale by Fruita and other local community residents since the area's settlement back in the 1880s. In the 1930s, rockhound Arthur "Doc" Inglesby, the first non-Mormon settler, built his house and fence using some of this flagstone and ripple rock. (His fence rock was apparently later re-used for many of the directional signs within the headquarters area of the park.) Ripple rock was also the main construction material for the CCC road, trail, and building projects in the monument, including the old ranger station and the visitor center, begun in 1964. So, Clair Bird was not the first to mine construction rock within the monument, just the first to do so commercially. [86]

Clair Bird had been continually at odds with Capitol Reef management since the early 1960s. Descended from Fruita pioneer Jorgen Jorgensen, Bird had inherited the Capitol Reef Lodge operation from his father, Archie, and ran it with his mother, Emma. One sore point with park staff was that Clair Bird rarely followed concession policy. He would serve meals and drinks only to guests staying in his lodge, and closed his lodge at some of the busier times of the year. [87]

At first, it appeared that Bird would not be using his state mineral lease. Instead, he used his state section lease to build a Conoco service station and curio shop next to the highway, less than 1/4 mile directly uphill from the visitor center. [88] While this gas station, in plain sight of headquarters, was obviously troubling to park managers, it wasn't a major problem. The situation changed dramatically in October 1970, when bulldozers began cutting an access road from the highway to a mining site west of Bird's service station. According to the terms of Bird's 1964 state mineral lease, mining was to commence within the first year of the lease and be "pursued diligently" after that time, if the lease was to remain valid. Although Bird did not initiate work until six years later, he continued to pay $80 annually to the state, which therefore never began termination proceedings on the claim. [89]

Bird declared that he was planning to use his bulldozers to excavate the rock on both sides of the highway below the scenic Castle formation, and market the material to building companies throughout the West. [90] Once the bulldozers arrived, the National Park Service sought to purchase or exchange other federal land for the mining locale. A state/federal land swap fell through after Bird indicated that he would settle for no less than a prime location on the newly completed Interstate 70 north of the park, or compensation in excess of $100,000. Bird evidently was pressing his advantage to leverage himself a profitable deal. [91]

In early April 1971, National Park Service attempts to acquire Section 16 intensified when Bird began excavating about 20 tons of ripple rock. [92] With the support of the Green Hornet Mining Company of Bloomfield, Col. and supposed markets in Utah, California, and Oklahoma, Bird's flagstone mining operation had a lot of earnings potential. [93] At the request of the National Park Service, Utah Governor Calvin Rampton declared a 30-day moratorium on the mining operation. During this period, the state was able to transfer the property to National Park Service management -- with the stipulation that Bird's valid lease be carried over. "Within hours thereafter," Assistant Secretary of the Interior Nathanial Reed reported, "the National Park Service acting on behalf of the Department of the Interior canceled the lease. The basis of the lease termination was that Bird was doing irreparable damage to an aesthetic, readily visible portion of the monument and his lease was terminated automatically when he failed to begin mining in 1965." [94]

Clair Bird would not concede defeat. The battle raged, with the National Park Service determined to halt the mining and Bird refusing to compromise. A blow-by-blow account was reported in the local and regional newspapers. Since this mining conflict was taking place at the very time the final legislation for Capitol Reef National Park was being debated in Congress, several of the newspaper articles emphasized the local support for Bird. This support, though, was not particularly strong. On one hand, some local citizens were glad to see a local entrepreneur giving the National Park Service fits. On the other hand, others voiced concern about the damage his actions inflicted on the scenery, and the impact of negative publicity on tourism. [95]

Despite Bird's previous actions, the National Park Service apparently believed that he would agree to the lease termination, and was thus unprepared for his next move. Declaring that the National Park Service termination notice was invalid because it failed to allow the 30-day notice stipulated in his lease, Bird announced that he would immediately resume mining. On Sunday, July 11, nine days after the National Park Service acquired the land and served the termination notice, Bird resumed mining flagstone. Caught off guard, the National Park Service was not able to stop the mining for two days, until federal marshals served Bird with a temporary restraining order. [96]

From that point, the mining was halted while the conflict shifted to federal court. Bird won the first round in 1973, when U.S. District Court Judge Willis W. Ritter ruled that the U.S. government owed Bird and Green Hornet Mining $250,000 for wrongfully terminating their mining lease. [97] This judgment was reversed in 1974 by the U.S. Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals. While the appellate court ruled that the district court had no jurisdiction to award federal money to Bird, it could not judge the validity of the mining lease because that issue was not part of the appeal. This left the issue unresolved. [98]

Throughout the rest of 1974, both sides attempted to gain the upper hand. The National Park Service put a halt to any immediate attempt to mine the flagstone by requiring Bird to submit a detailed operations plan for the superintendent's approval and to put up a substantial reclamation bond. Clair Bird responded by offering to sell out for $300,000. This could have been the end of the entire episode, except that Capitol Reef had already overspent its land acquisition money authorized by Congress. The National Park Service then asked The Nature Conservancy to help purchase the land. The Nature Conservancy initially approved of the plan but requested that the National Park Foundation also endorse the project. When the foundation refused, the plan fell apart. Once again, the issue was at a stalemate. [99]

Then, in July 1975, Bird quarried two shipments of ripple rock without first submitting the required plan of operations. This brought an immediate reminder from Regional Director Lynn Thompson that Bird must submit not only a mining plan, but also a substantially larger bond than the $5,000 offered to Superintendent Wallace. [100] This proved to be the last attempt by Bird to mine ripple rock. A combination of the rigid National Park Service regulations and the lack of customers for his flagstone put Bird out of the building stone business. Nevertheless, he still held the lease and still posed a potential threat. [101]

In a syndicated article that appeared throughout the country, Bird stated that he was no longer willing to sell. Rather, he declared defiantly, "I may just stay here and mine for 100 years. I'm a bachelor and have no one depending on me, so I don't need their money. And I'd just as soon fight them." [102]

Bird used the article as leverage to re-enter negotiations. In December, 1975 and again in August 1976, Clair Bird notified National Park Service officials of his intent to sell or exchange all his lands within the monument, but the status of the mining lease remained uncertain. There is no record of the National Park Service response. [103]

With his efforts to quarry ripple rock stymied, Bird decided to add a few outbuildings to his lodge operation during the summer of 1977. At this point, the National Park Service had enough. In November, Director William Whalen wrote Sen. Henry Jackson of Washington State, requesting his Senate Interior and Insular Affairs Committee to approve a declaration of taking so that all of Bird's interests at Capitol Reef could be acquired. Director Whalen argued, "Since there is no possibility of a negotiated settlement with Mr. Bird, it is imperative that his holdings be acquired by filing a declaration of taking to preclude further mining operations and to prevent additional development on the land." [104]

As part of the proceedings to buy out Clair Bird, his mining lease was analyzed in May 1978. The examination showed clearly that if Bird had ever had a market for his ripple rock, it had long since vanished. This lack of a market, the failure to follow the requirements of his lease, and the fact that an insignificant amount had either been taken from the site or royalties paid to the federal government, proved to the appraiser that the mining lease on section 16 "had a NIL VALUE as of January 13, 1978." This date was the official date of closing for all of Bird's properties within the park and he was notified to vacate his Capitol Reef properties by June 15, 1978. [105]

The park service tore down Capitol Reef Lodge and the Conoco gas station about a year later, and naturalized the Bird ripple rock quarry as best it could. In 1994, visual evidence of Bird's business ventures at Capitol Reef is hardly visible.

The quarrying of ripple rock at Capitol Reef was not very profitable. For one thing, Capitol Reef's isolation meant high shipping costs to get the raw materials to the buyers, who evidently lost interest and withdrew from the deal. After that, Clair Bird seemed determined to continue his quarry operations more to defy the National Park Service than to make an actual profit. Possibly, Bird's goal from the beginning was to win compensation from the National Park Service in exchange for his mining lease. In any case, Bird cost the National Park Service a great deal of time and money in trying to stop him, virtually daring the agency to condemn his holdings within the park. This exasperating case is a strong argument for the National Park Service to acquire all state sections within the park as soon as possible.

Mining Regulations And The End Of Claims

Within Capitol Reef

As shown by the cases presented above, the National Park Service historically has not had as much control over mining within its units as one might assume. In fact, prior to the 1976 Mining in the Parks Act, the Bureau of Land Management actually controlled all mining claims on the public lands subject to the antiquated Mining Act of 1872. [106]

Virtually every national park and monument, including Capitol Reef, has been created subject to continuance of valid, existing rights. This stipulation meant that those holding valid, existing mining claims and oil and gas leases could continue working, and that the park or monument had virtually no say in the matter. This fact, together with the lenient regulations of the 1872 Mining Act, allowed uranium mining to proceed within Capitol Reef National Monument during the 1950s. It also enabled owners of the Tappan, Rainy Day, and other unpatented claims to continue blasting, mining, and making road improvements even after Congress created a national park in the area.

The Hard Rock Mining Act of 1872 was passed to legitimize previous claims and stimulate new mining operations on public lands. Under this act, a person could stake a claim, both on the ground and by filling out a one page application in the county recorder's office. An individual claim encompassed 20 acres, but the number of claims a person could acquire was unlimited. A group of up to eight individuals could create an association and claim up to 160 acres. These claims are called "unpatented" because the surface of the land was still owned by the federal government, but the claimant could pretty much do what he wanted on the property: build a home, divert water, cut timber, or graze livestock, for instance. The courts and federal agencies have been continually lenient in this regard. [107] Fortunately for Capitol Reef, the mining claims were on fairly inhospitable lands, which made continued occupation of the site undesirable.

The key to maintaining any mining claim under the 1872 act was to make a "discovery" of a valuable mineral deposit, and prove $100 worth of assessment work every year. Of course, the term "valuable" is open to broad interpretation, with the result that nullification proceedings can be dragged through years of appeals. The annual $100 assessment in 1872 constituted a substantial investment, but is virtually nothing now. Renting a caterpillar tractor and blading the road into the mine once a year could easily cost the required $100. Thus, so long as the claimant could prove a "discovery of valuable minerals" prior to acquisition of the land by the National Park Service, and so long as he kept up with the required assessment work, there was little the agency could do to nullify the existing claim. [108]

The situation changed in 1976 with passage of the Mining in the Parks Act. [109] As part of the 1970s federal land reform movement (which also saw passage of the National Environmental Policy Act and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act), the Mining in the Parks Act sought to give National Park Service officials tighter control over mining within parks and monuments. [110] The act requires claim holders to register all active claims, provide a detailed plan of operation for park manager approval, and purchase a substantial performance bond that must cover all reclamation costs. The law also prohibits new claims in any national park or monument. National recreation areas, however, are specifically exempted from these provisions. [111] Plans of operation and performance bond requirements have been used to prevent work on the Rainy Day mines, and similar requirements were used previous to the 1976 act to challenge Clair Bird's ripple rock operation.

While it could be argued that the 1976 Mining in the Parks Act was not strict enough, especially toward privately owned or patented claims, this act has proven to be a useful tool for National Park Service managers trying to prohibit mining within their parks. [112] One of the most useful aspects was the law's stipulation that all claims must be recorded with the Bureau of Land Management by Sept. 28, 1977, or be declared null and void. This provision enabled many parks to summarily dismiss thousands of outdated claims throughout the West. In Capitol Reef National Park, a total of 189 unpatented claims were recorded by the September 1977 deadline. The National Park Service challenged each of these claims, usually on the inability to prove a valid discovery prior to the 1969 withdrawal of the land. By 1982, all but the Rainy Day Mines #2 and #3 and been declared invalid. [113] When the Rainy Day claims were finally nullified in 1986, the threat of resource damage from hard rock mining within Capitol Reef was over. [114]

There were, however, three oil and gas leases remaining on state-owned sections within park boundaries in 1986, down from 13 in 1970. [115] Since the State of Utah had assured Capitol Reef managers that these leases would not be renewed, and because the possibility of their becoming active was extremely remote, oil and gas leases within the park were effectively curtailed as well. [116] Thus, by the end of the 1980s, mining and mineral exploration within Capitol Reef National Park had been either suspended or eliminated.

Outside encroachments on Capitol Reef National Park, however, are another matter. Since the park was created in 1971, several large energy-extraction ventures in and near the park have been proposed. The first of these were proposals to build power plans southwest and northeast of the park; later came proposed coal, tar sands strip-mine operations, and imaginative plans for tapping oil and gas in the southern end of the park.

Oil And Gas Exploration

There has been periodic drilling of oil and gas in various areas surrounding Capitol Reef National Park since the 1920s. By the time the national park was created in 1971, there were approximately 6,000 acres of leases within the park, mostly on state-owned sections. There were also hundreds of other leases immediately adjoining two-thirds of the park boundary. [117]

By 1974, all but five oil and gas leases within Capitol Reef had either expired or were withdrawn. While the specific reasons for the lease withdrawals are not known, it seems likely that the hindering presence of national park regulations, coupled with high recovery costs, outweighed the possibility that valuable deposits could be found beneath park lands. [118]

The remaining five leases, scheduled for termination by mid-1980, were all located in the southern end of the park. One was just north of the Burr Trail, three were in the vicinity of the Rainy Day Mines, and all of section 18, Township 36 south, Range 9 east was claimed by Viking Exploration, a subsidiary of Sun Oil. This latter lease, along with similarly owned leases in adjoining sections in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, proved the most troubling of all the oil and gas leases in the immediate area. [119]

Trans Delta/Viking Exploration Lease: 1972-1982

In August 1972, Trans Delta Oil and Gas Company, the designated operator for Viking lease U-9406, notified the regional Bureau of Land Management office in Kanab of its plans to begin initial exploration on leases soon to be incorporated into the new Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. These were less than a half-mile south of Capitol Reef National Park. To gain access, Trans Delta would improve the existing road and build additional road into this rugged, scenic area along the eastern escarpment of the Circle Cliffs. [120]

Trans Delta faced dealing with numerous federal agencies with conflicting missions, mandates, and agendas. The United States Geological Survey, which was responsible for the lease, actively encouraged exploration of the potentially major oil field under the Circle Cliff/Waterpocket Fold contact. The fledgling Glen Canyon National Recreation Area was struggling to comply with congressional requests for wilderness studies, while also permitting mineral exploration. The Bureau of Land Management was placed in the unenviable position of coordinating all the paperwork and correspondence, as well as controlling most of the access route to the drill site. Capitol Reef National Park was involved only because Trans Delta had determined that it would be less expensive and less destructive to detour its access road around the head of a canyon, which meant building a small section within the park. [121]

Throughout 1973, the USGS, the BLM, and the National Park Service attempted to coordinate the necessary environmental assessment. The National Park Service objected that the environmental assessment was not thorough or detailed enough, and argued that an environmental impact statement was needed. The U.S. Geological Survey disagreed, unilaterally approving the Trans Delta drilling application. [122]

At this point, the National Park Service had a choice. It could refuse to issue any special-use permits for the road building and drilling, thereby alienating the USGS just as its support was needed in the upcoming wilderness designations for Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Or, the National Park Service could reluctantly issue the permits, hoping that environmental organizations would seek an injunction against the operation on the grounds that an environmental impact statement was needed. This second alternative would also show the local communities that some mineral exploration would be approved within the new recreation area. This was the alternative chosen by Regional Director J. Leonard Voltz. For the sake of federal agency unity and positive local publicity, and gambling that the environmentalists' lawsuit would hold up the project, both Capitol Reef National Park and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area were instructed by Voltz to issue the appropriate special-use permits. [123] National Park Service Acting Utah Director James L. Isenogle stated:

We have absolutely no fear of losing the respect or cooperation of the conservationists in the State of Utah as a result of the Trans-Delta case. They perceive our purpose in the sequence of events leading to the litigation and fully understand that the Service can, and probably will win more wilderness in Glen Canyon by losing this case in court than we could hope to by arguing our differences with USGS at the Departmental level and our position with residents of southern Utah and the State Government. [124]

The Sierra Club did indeed seek an injunction against Trans Delta and the various federal agencies in early December 1973. As a result, all oil and gas leases in Glen Canyon were suspended until a comprehensive mineral management plan could be completed. The strategy chosen by the National Park Service had worked. [125]

Then, in 1982 Viking Exploration resumed its request to drill in the same area. [126] This time, an elaborate plan to pipe the oil across Capitol Reef National Park ensured that park managers would be closely involved.

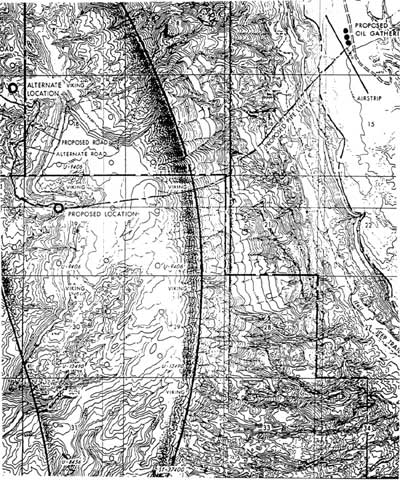

Viking planned to use the access route initially identified by Trans Delta back in 1973. If a valuable discovery were made, Viking would drill on other leases in the immediate area, including those within Capitol Reef. To get the oil from the isolated drill site, Viking proposed constructing a pipeline down the east face of the Waterpocket Fold, across Halls Creek near the Fountain Tank tinajas, and up to an oil storage and loading facility near the abandoned air strip on Thompson Mesa (Fig. 42). Most of this route would be through a state-owned section of land within the national park. [127]

|

| Figure 42. Viking pipeline proposal. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Over two days of meetings (Sept. 28-29, 1982) at Page, Ariz., Viking representatives laid out their proposals to the management staffs of Capitol Reef and Glen Canyon. Superintendent Hambly reported that, while the meetings were cordial, the proposal to construct a pipeline across the lower Waterpocket Fold was a cause of great concern. Viking had already contacted the Utah State Trust Lands Office, which had advised the company to construct the pipeline right away. This action would allow Viking to avoid any entanglements resulting from the likely transfer of state land to Utah's national parks, under consideration as part of the "Project Bold" proposal. This attitude on the part of the State of Utah, according to Hambly, gave Viking the impression that state school sections were "fair game for some sort of activity." [128]

Hambly also thought the Viking representatives were unfamiliar with the topography of the landscape on which they were planning to build. He wrote:

It was pointed out that aside from the undesirability of having pipelines through Halls Creek, Viking would have to contend with a 2,000 foot vertical drop at 50-60 degrees on the east side of the canyon with an additional 800-1000 foot vertical cliff on the east side of Halls Creek - all of this over rock where a pipeline could not be buried or the area reseeded to reclaim the land. Flight over the area on September 29, seemed to convince Viking of the unfeasibility of pipeline construction through Section 16 [the state section in question]. [129]

But Viking did not give up on the pipeline altogether. As an alternative to the climb up Thompson Mesa, the company tentatively proposed building the oil collection facility at the bottom of Halls Creek. Hambly objected to the proposed drilling within park boundaries. Viking responded that directional drilling from outside the park could be done, but it would be prohibitively expensive. [130]

In the end, Viking's elaborate plans never came to fruition. When the company was denied permits in 1981, it renewed efforts the following year. However, Viking was never able to prove it had a valid lease within the park, nor did it ever submit the required plan of operations. Consequently, all of Viking's permit applications were summarily denied. [131] The protections provided by the Mining in the Parks Act put a halt to Viking's plans early in the process.

As of 1994, all oil and gas leases are terminated within Capitol Reef National Park. Under current law and in the current political climate, it is safe to say that oil and gas drilling will not be a threat in the immediate future. Nevertheless, the potential for drilling has been identified and is well known. Future drilling ventures can be anticipated once there is a pivotal change in price of oil.

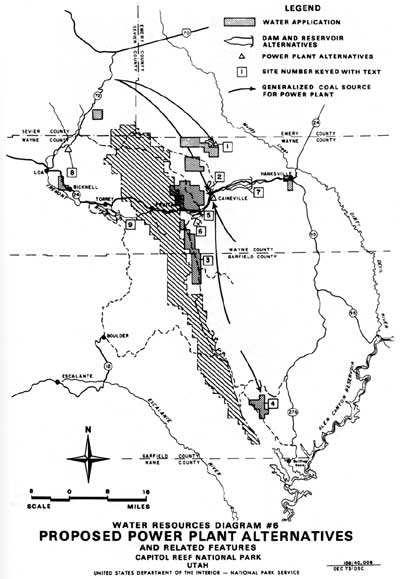

Coal-burning Power Plants

In the early 1970s, a proposal to build a large coal-burning power plant on top of the Kaiparowits Plateau, 30 miles southwest of Capitol Reef, received national attention. [132] Even while this classic battle between developers and environmentalists was shaping up, another enormous power plant was proposed for construction only 10 miles east of Capitol Reef. Located on Salt Wash at the base of Factory Butte, this $3.5 billion plant was projected to bring over 11,000 workers to the area, use 10 million tons of coal a year from neighboring Emery County, and consume 50,000 acre feet of water per year. This water would be provided by a dam and reservoir on the Fremont River, and by supplemental ground water wells. In return, the plant would produce a peak 3,000 megawatts of electricity for several Utah and southern California communities for 35 years (Fig. 43). [133]

|

| Figure 43. Proposed power plant alternatives. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The Intermountain Power Project (IPP) was funded by a loose consortium of Utah, Nevada, and California communities. In the early 1970s, the IPP was considered only a pipe dream. Then, when the Kaiparowits Project was withdrawn after lengthy court battles made production too costly, IPP was resurrected in 1976. [134]

The close proximity of low-sulfur coal, the unclaimed water in the Fremont River, the assumed support of local communities desperate for economic growth, plus the relative isolation of the Salt Wash site combined to make the Caineville-area site appear ideal. The only stumbling block was the presence of a national park only 10 miles away.

Why IPP officials believed they would be permitted to build an enormous power plant so close to Capitol Reef National Park is unclear. In an apparent attempt to pre-empt objections, IPP emphasized in all its planning documents that its pollution control measures were the most stringent available, and pointed out that prevailing easterly winds would carry smokestack emissions away from the park. Officials predicted that for just a few days of the year would the wind shift and bring an estimated 10 tons of nitrous oxides, 1.6 tons of sulfur dioxide, and 0.4 tons of fly ash per hour into the Waterpocket Fold. [135]

IPP also maintained that considerable thought had gone into selecting the plant location. The facility would be built in a valley surrounded by high Mancos cliffs, so that only the tips of the smoke stacks would ever be visible to passersby. Further, the water necessary to cool the plant operation would consist of the unclaimed winter runoff in the Fremont River. IPP managers argued that their water storage system would actually stimulate agricultural development in the eastern end of Wayne County. Finally, the 11,000 construction workers and 500 full-time employees needed to operate the plant would be accommodated by building one or more complete towns in the area between Caineville and Hanksville. [136]

Although countering objections were raised by some local residents in a rare partnership with environmentalists, air quality regulations would prove to be the silver bullet that killed the proposal. Even while IPP was finalizing its plans, Congress, as part of renewing the Clean Air Act, was deciding whether all national park lands should be designated as Class I airsheds -- meaning that park air quality would be protected by the strictest standards. Even if Congress passed the 18-day variance supported by the Utah delegation, IPP would probably be unable to meet the new requirements. [137] As IPP Project Engineer Jim Anthony complained to the press, "The unrealistic standards of the proposed [Clean Air] legislation would prevent construction of the Intermountain Power Project because of its proximity to Capitol Reef." [138]

Unfortunately for IPP, Congress passed and President Jimmy Carter signed the revised, more restrictive Clean Air Act into law the next year. The August 1977 act states, "National parks which exceed six thousand acres in size and which are in existence on the date of enactment of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977 shall be class I areas and may not be redesignated." [139]

Even though Congress allowed each state to permit some variance to the strict Class I requirements, the president, through his secretary of interior, would have the final say. This virtually guaranteed that Capitol Reef National Park would be protected from any nearby coal-burning power plant, so long as environmental protection was a presidential priority. [140]

It soon became clear that the Carter Administration would not condone such a variance for Capitol Reef. Secretary of Interior Cecil B. Andrus quickly notified IPP managers that they had better start looking at other possible sites. [141] Project President Joseph C. Fackrell was understandably "disappointed." After all, $7 million dollars had been spent on background environmental research for the Salt Water location. Secretary Andrus recognized the burden this put on IPP, but maintained that the location so near Capitol Reef was simply unacceptable. Instead, Andrus urged IPP planners to focus their attention on a site near Lynndyl, Utah, just north of Delta and about 100 miles northwest of Capitol Reef. [142]