|

Capitol Reef

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 16:

ROADS, TRAILS, AND UTILITY RIGHTS-OF-WAY

In the rugged Waterpocket Fold country, human access has historically been a concern. Led by stockmen and miners, newcomers have blazed roads and trails through narrow canyons and over rocky ridges to the wide open desert country east of the Waterpocket Fold. Because of the difficult terrain, few routes could be maintained. Even the roads that were at least graded remained extremely rough and rocky, effectively barring admittance to all but the most determined.

By the 1930s, businessmen and tourism boosters saw the lack of an all-weather road through southern Utah as the main reason the area remained poor and undeveloped. Cattle and sheep ranchers also wanted better roads to provide easier access to their winter grazing lands. Many were certain that after Capitol Reef National Monument was created in 1937, paved roads would follow. In fact, a key reason for campaigning for National Park Service involvement in the area was the belief that a park would bring about road improvements. Yet, nothing changed for 20 years.

Finally, in 1962, Utah Highway 24 was rerouted and paved through the Fremont River canyon. The new road brought more people into the area and changed circulation patterns in the monument and on surrounding lands. Within Capitol Reef, the old, traditional route through Capitol Gorge was closed by the park superintendent, and trails were built to accommodate hikers. Better access to the area encouraged more people to explore the region's backcountry. Easier travel and improved utilities benefited the local communities, stockmen, and entrepreneurs. As a result, some area businessmen and politicians continued to push for even more roads and utility corridors.

Demands for improved access coincided with the dramatic expansion of Capitol Reef National Monument in 1969 and its redesignation as a national park two years later. Concerns over transportation and utility access were key components of the congressional debate and final authorizing legislation. But even the call for wilderness and transportation studies could not resolve the growing dispute over how access should be controlled in the new park. The drawn out controversy over the paving of the Burr Trail road exemplifies the continuous conflict that typifies road development in southern Utah.

This chapter presents a historical chronology of the road and trail developments within the headquarters or old monument area, as well as on lands later incorporated into the monument and park. Specific analysis of the transportation and wilderness studies required by the park's enabling legislation, the 1982 Capitol Reef General Management Plan, the ongoing Burr Trail controversy, Revised Statute 2477, and a separate segment on power and telephone rights-of-way conclude this chapter. Since roads, trails, and utilities are a fundamental part of park operations, the other chapters of this administrative history should be cross-referenced.

Early Monument Roads and Trails

Roads Before 1937

Because only a few hundred people settled the rugged terrain of south-central Utah, state- or county-sponsored road construction was rare until well into the 20th century. The enormous amount of effort required just to survive left little time or money to invest in road construction. When a road was built in the area between the late 1800s and 1930s, it was mostly done by cooperative efforts involving local residents. Given these conditions, the roads of the Waterpocket Fold country throughout this period were crude, at best. [1]

By the mid-1930s, the only road passable by car through the Waterpocket Fold was the road that went from Sigurd, through Loa, Bicknell (then Thurber), and Torrey, and then down to Fruita. From Fruita the road veered south, following the washes and hills at the base of the towering Wingate cliffs. The wagon road from Fruita through Capitol Gorge had originally been cleared by Elijah Cutler Behunin in 1883. Further improvements were made in 1892, when the newly created Wayne County Board of Commissioners appropriated $100 of territorial road funds for improvements for the Capitol Gorge section. [2] From Capitol Gorge, the rough, two-rut road, passed Notom, cut precariously down across the steep sides of Mancos shale hills (the Blue Dugway), and went on eastward to Caineville and Hanksville. In 1910, this route was designated the first state road in Wayne County. [3]

Other roads connected to Utah Highway 24 at the turn of the century included the Grover cut-off, Notom Road, and the Fremont/Caineville wagon route. The Grover cut-off was a shortcut from Teasdale and Grover that descended the steep Miners Mountain to connect with the main road just west of Capitol Gorge. Evidence of wagon ruts and blasting can still be seen on the stretch of road in the park that is now part of the wagon road loop trail. As late as 1930, this route was included on regional maps.

Early South District Roads

Notom Road, which leads from the old community of Notom to the Burr Trail, is the oldest continuously used road now within Capitol Reef National Park. Begun as a supply route for gold miners in the 1880s, it was later used to haul wagons of supplies to winter livestock ranges, the Baker Ranch, and a 1929 oil drilling operation in the Circle Cliffs. According to Golden Durfey, a Notom resident since 1910, the roadbed is in nearly the same location as it was when he trailed sheep down it as a young boy. At The Post, the road veered east toward the Henry Mountains. As a point of reference, the Burr Trail was only a steep sheep and horse trail until the late 1940s, and the Halls Crossing Road down through Muley Twist Canyon was never used on a continuous basis (Fig. 46). [4]

|

| Figure 46. Early South District roads and trails. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Early North District Roads

According to local rancher Guy Pace, the first road to Hanksville was not through Capitol Gorge, but rather over the Hartnet in the northern section of the park. From the small town of Fremont, this road went over Thousand Lake Mountain, down the Polk Creek drainage and across the Hartnet to Rock Water Spring. From there, this wagon road went east to Willow Spring, and then down Caineville Wash to Caineville and Hanksville. [5]

Regional travel guide Ward Roylance's interpretive handout, "Four Roads Lead to Cathedral Valley's Great Monoliths," further elaborates on this early route. The road, he wrote, was named for Dave Hartnet, who purportedly drove the first buckboard through the area from Fremont to Caineville. Thereafter, the rough trail was used as a freighting route between Caineville and settlements in upper Wayne, Emery, and Carbon Counties. [6]

It is uncertain exactly when this route was first used, how often it was used, or whether this was the road traveled by the first settlers to towns east of the Waterpocket Fold in the early 1880s. It is also unknown how closely this old wagon route follows the current road alignments, since no early maps of the North District have been found.

According to Pace and fellow rancher Garn Jeffery, a switchback wagon road into the Upper South Desert was built off the Hartnet road by Alonzo Billing and some members of the Blackburn family around 1895-96. It is unclear if this road reached the Fremont River. It is known that the Blackburns attempted to farm a small section at the junction of Polk and Bullberry Creeks at about this time. [7]

Other early roads within or near the current boundaries of Capitol Reef National Park included a 1890 wagon route down Meeks Draw to the Last Chance (Baker) Ranch. This road was later realigned down Windy Ridge in the 1920s to make it passable to automobiles. Later known as the Baker Ranch road, it apparently was the first automobile road into the northern end of the Waterpocket Fold. The road south from Fremont Junction to the Last Chance Ranch was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps around 1934. A wagon road evidently was also built from this ranch down Rock Spring Bench into Upper Cathedral Valley at about this same time. Other routes via the Caineville Wash and Oil Bench Road were not used until the 1940s since there appears to have been no route through the length of lower or upper Cathedral Valley. [8]

Roads In Capitol Reef National Monument:

1937-1938

One of the key reasons why Wayne County residents wanted a national park was to draw state and federal road-builders, and thus tourist and other businesses, to the area. [9] A paved highway through the Waterpocket Fold and across the Colorado River to Blanding had been promised by Governor George Dern when Wayne Wonderland was proposed as a state park in 1925. Yet, by the time Capitol Reef National Monument was created on August 2, 1937, there was still no oiled surface in all of Wayne County. Utah 24 from Torrey to Fruita, according to National Park Service Engineer Frank C. Huston, had never actually been constructed, but merely followed an old wagon track that had been established by use over the years. Huston wrote, "For some two miles [inside the monument, the road] follows the bottom of a wash and is impassable after big storms. There are no bridges or culverts. This road continues on through the Monument, going through the bed of Capitol Wash to the crossing of Pleasant Creek at Notom, 12.5 miles from Fruita, and continues on East through Hanksville." [10]

Huston found that the road was usually 18 to 20 feet wide, with narrower sections in Fruita and Capitol Gorge. The only bridges in the monument were a 16x36-foot wood span across the Fremont River in Fruita, and a small bridge about halfway from Fruita to Capitol Gorge. There were two spurs off the main road: one went a short distance along the bottom of Grand Wash, and another headed south from the west entrance of Capitol Gorge to Floral Ranch on Pleasant Creek. There is no mention of any other roads in the monument. Huston concluded the only place a right-of-way would be needed was across Aaron Holt's land, where a proposed road realignment and bridge construction across Sulphur Creek were desired. [11]

The state highway department also recognized the poor condition of Utah 24. Engineer Huston reported that the state had already identified a new route from Torrey to Fruita, and had begun work between Chimney Rock and Sulphur Creek, just west of Fruita. [12] Later, the main improvements to Utah 24 within Capitol Reef would come as a direct result of the monument's creation.

CCC Road Work: 1938-1942

Civilian Conservation Corps Foreman Marion Willis and his crew of 17 men arrived at Capitol Reef just a month after the establishment of the monument. This federally funded project, under the auspices of the Emergency Relief Administration (ERA), would continue over the next five years. Besides building the National Park Service ranger station/residence and stabilizing stream banks, crew was to improve the road and trails in the monument. [13]

Even before camp was set up at the base of Chimney Rock, workers began stabilizing the road between the proposed headquarters area and Fruita. The road was also widened to the 18-foot standard used on the state-improved section from Chimney Rock to Sulphur Creek. [14] ERA Foreman Leon Stanley described the work accomplished:

Three-tenths of a mile of road SE of the Fremont River bridge in Fruita was improved. The road was changed from 11 feet in width to 18 feet. Four hundred feet of rock wall was constructed to improve the road width, grade, drainage and to keep the road from sloughing into an irrigation ditch. Part of the ditch was relocated....Seven-tenths of a mile of road below the Fremont River bridge was improved. Some road drainage was established. An irrigation ditch was improved and repaired to keep the road dry at this point. [15]

This work, along with some minor improvements south of Fruita, consumed much of the road crew's efforts for the rest of 1938. [16]

In May 1939, work began on the stretch of road between Fruita and Capitol Gorge. This work consisted of "cut slope flattening, providing improved sight distance on the sharper curves, minor widening, and drainage improvements which included stone check dams in the road ditches that are eroding badly." [17]

As part of this "temporary" construction, one rock culvert was rebuilt and another was replaced with steel pipe. This shows that rock culverts were in place along this portion of the road before the arrival of the CCC. Because the various documents do not specify how many or exactly where culverts were built by the CCC crews, it is unknown how many of those have lasted into the 1990s. [18]

In October and November 1939, work crews began reclaiming the old roadbed between Chimney Rock and Fruita by re-establishing the original slope contours. [19]

During 1940, a wooden bridge over Sulphur Creek near the ranger station was completed, and more extensive work was started on the Danish Hill portion of the road south of Fruita. [20] In drawing the initial realignment plans, it was discovered that a small portion of the road in S26 T29S R8E was actually outside the monument boundary. The oversight may have delayed the start of the Danish Hill project until the Wayne County Board of Commissioners approved the realignment and granted a right-of-way. [21] This final CCC project was almost completed by April 1942, when the Utah State Road Commission promised to provide road equipment to finish the job. Unfortunately, the rapid mobilization for World War II canceled all further federal assistance, prematurely ending CCC work at Capitol Reef. [22]

At the same time that the CCC was working in the monument, the Utah State Road Commission paved Utah 24 from Sigurd to Torrey and state crews began grading the road to Fruita on a regular basis. The state also began planning for alternative routes through the Waterpocket Fold. [23] Throughout the late 1930s and early 1940s, commissioners conducted several reconnaissance trips through Wayne and Garfield Counties in search of a route for an all-weather highway through southern Utah. Two routes were proposed. One would pass through Garfield County from Bryce Canyon to Escalante and then around the southern end of the Waterpocket Fold. The other would follow the Fremont River from Fruita to Caineville, continue across the Henry Mountains, and go on to Blanding via the Dirty Devil and Colorado Rivers and White Canyon. [24]

In anticipation of the Fremont River route, Zion National Park Superintendent Paul Franke proposed that the current route through Capitol Gorge be made into a scenic drive. Franke told his regional director:

We much prefer that a parking area be developed at the entrance to both Grand and Capitol Gorges, and a by-pass to permit cars to the wash and travel on the wash gravel down into the gorges. In this way an unimproved road can be maintained in passable condition by removing rocks after each flood. Proper signs at each parking area can describe possible gorge hazards. Such a drive into the gorges would remain always one of the great thrills of this monument. [25]

Thus, the idea of creating a scenic drive along the old Utah 24 alignment through Capitol Gorge was considered as early as 1943. In 1947, Zion National Park Superintendent Charles J. Smith went even further, proposing to close the Capitol Gorge road to traffic once the Fremont River highway was completed. Smith wrote, "We would prefer however to retain a minor spur road through the Gorge terminating in a turnaround at the east monument boundary....It is agreeable to us to retain the Grand Gorge spur as a minor road." [26]

These plans for changing the roads, and thus the travel patterns, within Capitol Reef National Monument were put on hold for another 15 years. Despite continued promises to local residents and National Park Service officials, road commissioners postponed construction of a paved highway through the Fremont River canyon until the National Park Service acquired the necessary funding through Mission 66.

Meanwhile, the only significant change in Capitol Reef's roads occurred in 1941, when a new route was used between the Sulphur Creek bridge, past the Fruita schoolhouse, and near the upper north ditch to Alma Chesnut's property. This road, in approximately the same alignment as the present highway, replaced the old road that crossed Sulphur Creek parallel to the western edge of Chesnut's property. [27]

Hickman Bridge Trail: 1939 - 1945

One of the most significant accomplishments of the CCC era was the construction of a formal trail from the Fremont River to Hickman Natural Bridge. The graceful, 230-foot stone span is located up a small side canyon about one mile north of the Fremont River and one mile east of Fruita. Previous to the monument designation in 1937, access was provided by a rough horse trail that ascended a steep slope from the Fremont River. The CCC's job was to establish a permanent, improved trail from the river to the bridge. Crews were also to build an access trail from the proposed headquarters site through the heart of privately owned Fruita along Sulphur Creek and the Fremont River.

In 1939, the first 1.5 miles of trail were built through Fruita to the foot of the old horse trail. Early photographs of the trail indicate it ran along the Fremont river bed. [28] Property owners Orval Mott and R. A. Meeks donated a 100x440-foot right-of-way across the western edge of Fruita for the trail. The Oylers donated two sections of trail right-of-way, 10 feet wide and nearly 1,570 feet long. When the new road past the Fruita schoolhouse was blazed in the early 1940s, the trail was realigned to follow this route until it reached the Alma Chesnut property. From there, apparently, it followed the river through the Oyler property down to the present trailhead. [29]

From the river, the CCC crew constructed a dry-laid rock retaining wall to support the trail up a short stretch of steep cliff overlooking the Fremont. From there, the new trail switchbacked up to the rim and continued to Hickman Bridge. [30] From the bridge, the plan was to build additional trail up to "Bootleg" or Whiskey Spring and on to the rim overlooking Fruita. [31] As of 1948, this "rim" trail had yet to be completed. [32] There were also several other proposed trails, including as a route from Grand Wash to Cassidy Arch, that were postponed until the conclusion of Mission 66. [33]

Construction of these trails was delayed because there was no money. Since Capitol Reef had little visitation, did not even have a regular budget allocation until 1950, and was staffed solely by Charles Kelly as a "volunteer" custodian, it was unlikely that any trail -- or road -- work would be completed after the CCC left in 1942.

Impacts of Floods: 1938 - 1951

Late summer flash floods that wash out existing roads and trails have been an almost yearly problem for Capitol Reef managers. A 1938 flood that destroyed the bridge across the Fremont River should have been a clue that any road or trail along the floodplain would not last. [34] In August 1945, another flood washed large pieces from the Hickman Bridge trail where it followed the Fremont River. By December 1945, Charles Kelly had worked to make the trail passable to horses once again. Kelly also tried to improve the first part of the trail from the river up to the bridge, but could make only temporary repairs. He recommended that "the entire trail be rebuilt on a more permanent basis." [35]

Then in early August 1951, three cloudbursts struck the Capitol Reef area within two days, dumping almost 3.5 inches of rain and creating tremendous flash floods. The floods raced down the Fremont River, burying large sections of the Hickman Bridge trail in sediment. This flood ultimately was beneficial to the trail, since a work crew from Zion National Park was assigned to rebuild the rock walls and switchbacks first constructed by the CCC. According to Kelly, the crew blasted a new approach to the natural bridge. "This is a permanent improvement," he wrote, "and will eliminate much annual labor." [36]

The 1951 flood also wiped out the road into Grand Wash and made the main highway through Capitol Gorge impassable for several days. While a state road crew was able to open Capitol Gorge by the middle of August, it would cost the National Park Service around $250 to bulldoze enough rocks out of Grand Wash to make that spur road accessible to automobiles again. [37]

Road Improvements And Boundary Changes:

1951-1958

When the monument was created in 1937, the boundary ran along the northern edge of Utah 24's right-of-way from southwest of Twin Rocks, past Chimney Rock to the Castle formation. This boundary line had been suggested by monument investigator and Yellowstone Superintendent Roger Toll during the final boundary revisions in 1935, in order to avoid complications over the road's maintenance. [38] The problem with this boundary line, however, was that the road in those days followed wash bottoms in several locations. When a summer storm brought flood waters down the washes, the repaired road was realigned to one side or the other. This meant that the monument's boundary changed every time the grader came through to clear the road. The situation was exacerbated in 1952 when a new, graveled section of Utah 24 was completed between Twin Rocks and Chimney Rock: it swung the road's alignment northward by almost one mile. [39] Construction of a completely realigned and paved Utah 24 from Torrey to Fruita in the late 1950s caused further confusion. Toll's idea of making the road's northern right-of-way the boundary was simply not working. [40]

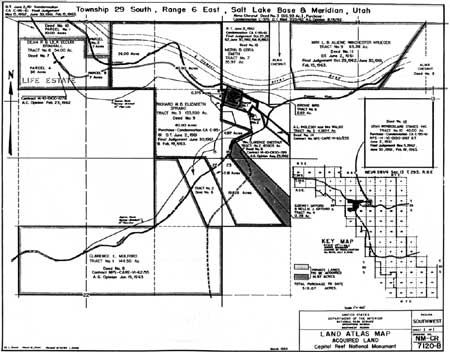

The obvious solution was to extend the monument's boundaries to include the entire road from the western boundary all the way through the monument. This change would avoid changes to the monument every time the road was realigned, and would give Capitol Reef more efficient control over future road construction and maintenance. A limited boundary adjustment to include at least some of the road was proposed in the monument's 1949 master plan, which described the road as primitive, unimproved, and subject to rerouting by floods and by users (Fig. 47). The plan noted, " It would seem more desirable to place the boundary by section lines or a natural feature less subject to change." [41]

|

| Figure 47. 1949 Master Plan, roads and trails. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The 1951 Boundary Status Report proposed that new boundaries be adjusted to run along section lines that would include the entire western approach of Utah 24 from the hill west of Twin Rocks (the monument and park's western boundary) to Fruita. Other small sections proposed for possible boundary expansion along the western side of the monument included an additional 80 acres between Danish Hill and Grand Wash, in order to incorporate the entire road within monument boundaries. Two 40-acre tracts were also proposed north of Sleeping Rainbow Ranch so that the Pleasant Creek access road would be in the monument, in case it was chosen as the later route for Utah 24. [42] The National Park Service decided to postpone any boundary adjustments until after construction of a new alignment west of Fruita. This left several hundred acres in the status of "no-man's land" throughout most of the 1950s. [43] Finally, in June 1957, the final six miles from the Twin Rocks formation near the western monument boundary to Fruita was completed. [44] With the new road's alignment firmly established, the proposed boundary revisions were approved by the director, faced no opposition in public hearings, and were formally authorized by President Dwight D. Eisenhower's presidential proclamation on July 2, 1958. [45] Besides extending the boundary south to Sulphur Creek, the 1958 proclamation also incorporated the remaining 240 acres of the section between Danish Hill and Grand Wash, a small section near the Egyptian Temple formation, and the two 1951 proposed small tracts north of the Pleasant Creek. The entire boundary extension was 3,040 acres, which increased the total size of Capitol Reef National Monument to 39,185 acres. [46]

Thus, by the end of the 1950s, Capitol Reef's boundaries had been adjusted, primarily to bring Utah 24 under monument control from the northwestern boundary all the way through Capitol Gorge. The next step was to coordinate the construction of a new paved highway along the Fremont River.

Mission 66 Road Improvements:

1956-1966

The dramatic changes and controversies that occurred at Capitol Reef National Monument as a result of Mission 66 have been discussed earlier in this administrative history. This section will therefore merely summarize the changes and focus on administrative details regarding rights-of-way, multi-agency agreements, and alignments. [47]

Funding And Fee Collection Issues: 1956 - 1958

The construction of a new road along the Fremont River involved multiple state and federal agencies, as well as private property owners. Because of the complexities involved, road construction east of Fruita, formally authorized in January 1958, was not started until the fall of 1961.

Once the decision was made to go ahead with the Fremont River route, the next step was determining which agency would fund which sections of the road. In January 1958, at a meeting of state, county, and National Park Service officials and Fruita land owners, the park service agreed to fund work along the Fremont River through Capitol Reef National Monument. The Utah State Road Commission would seek additional federal funds to complete the highway from the east boundary to Caineville, and would assume responsibility for the maintenance of the entire road through the monument. [48]

The other major issue involved the charging of National Park Service entrance fees on the new highway. In December 1956, the Utah Bureau of Public Roads District Engineer F. W. Smith wrote Superintendent Paul Franke that no fees should be charged on the new road. Smith reasoned that "a charge should not be made on a State highway for vehicles using the road since a large sum would be required to complete the improvement outside of the monument, and ...[since it had] been a State road since 1910." The State of Utah, he told Franke, wanted "a definite commitment of policy on this matter." [49]

Franke, in response, indicated that the National Park Service would not waive these fees. Pointing out that "the Utah parks needed 'stepping stones' not 'stumbling blocks'," Franke urged the state roads officials to reconsider their position. He reminded them:

You may recall that some thirty years ago there was a compromise reached on the construction of Federal roads in Zion, Bryce Canyon, and the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. Regulations were issued providing for free passage only to local residents in pursuit of their usual occupation or business. This has never been satisfactory. State residents outside of the local area protest and claim it is discriminatory. Truckers have abused the privilege and greatly endanger the park visitor. Action is now being taken to repeal such exemption. [50]

Franke concluded, "At present there are no instrucions or regulations requiring the collection of fees at Capitol Reef. We assume we will be instructed to initiate fees at this area when the developments and facilities provided for park enjoyment by the Federal government warrant such charges." [51]

Regional Director Hugh M. Miller did not agree with Superintendent Franke. In an appeal to National Park Service Director Wirth, Miller stated his concern about charging fees on the new highway:

It would be unfortunate if this minor problem should loom so large as to jeopardize all past efforts to reach an agreement with the State. You are referred to our memorandum of May 18 which outlines our conclusions...in which we expressed our doubts that a fee should ever be collected for travel over the through road section. This would not preclude the charging of a fee at the entrance to the monument facilities proposed south the junctions of what would then be a monument road exclusively. [52]

Director Wirth agreed with Miller and issued the following memorandum on January 25, 1957:

The State Highway officials may be assured that the Service will never propose collection of fees on the Fremont Gorge section of the road so long as it remains a segment of a through highway and an alternate route not involving unreasonable additional mileage is not available for through traffic or local residents. This would not, of course, preclude the charging of fees at the entrance to the monument facilities proposed south of the proposed State route. [53]

Thus, the National Park Service agreed with the state that no fees would be charged on the new highway through the monument. The decision, however, was based on the fact that there was no nearby alternative route, rather than on the concept of traditional use or the fact that the citizens of Utah were funding the western portion of the highway to the monument. During the multi-party meeting in January 1958, this promise not to charge fees was formally accepted and written into the cooperative agreement governing operations for the new highway on May 16, 1961. [54]

Fremont River Road Construction: 1961 - 1962

In June 1959, the survey of the Fremont River road was complete, but construction was delayed until the right-of-way through privately owned lands in Fruita could be obtained. [55] Delays in the appraisals of the inholdings would postpone construction for an additional two years. These delays were coupled with pressures from local and state officials and politicians to begin road construction. Hence, the National Park Service was pushed to initiate condemnation proceedings on tracts owned by Dean Brimhall, Max Krueger, Cora Smith, and Elizabeth Sprang. Right-of-way through 40 acres east of Fruita owned by the Campbell brother's Wonderland Stages was also required. Final condemnation of lands needed for the highway's right-of-way through Fruita was granted on June 2, 1961. Within one month, a $570,000 National Park Service contract for 5.73 miles of new road within Capitol Reef National Park was awarded to low bidder Whiting and Haymond Construction Company of Springville, Utah. Construction of the new route for Utah 24 began in August 1961 (Fig. 48). [56]

|

| Figure 48. Fruita inholdings and proposed highway route. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Despite the annual fall floods and other minor problems, road construction progressed through the rest of 1961. With construction more than half completed, work was suspended on Dec. 15 due to weather, to begin again the following February. On July 18, 1962, the Bureau of Public Roads accepted the new highway as satisfactorily complete. Capitol Reef Superintendent William T. Krueger estimated that the total cost of the road construction was $747,548.19, of which $677,548.19 were actual construction costs. Within one month, travel on the new highway had increased by more than 60 percent since the month before construction began. [57]

One reason for the increase in traffic on the new road was the larger number of visitors attracted by the new paved highway through the monument. Another reason was the fact that, once Utah 24 was paved all the way to Green River, this road became the shortest truck route between Los Angeles and Denver. Thus, prior to the late 1970s completion of Interstate 70 north of the park, semi-truck traffic through the heart of Capitol Reef was heavy. [58]

Perhaps the most noticeable resource alteration caused by the road's construction was near the current eastern boundary, where a cut was excavated to divert the Fremont River from its natural course. (In 1962, of course, the monument's eastern border along the Fremont River was west of this road cut, near the Behunin Cabin.) Rather than building the highway to follow the bend of an old riverbed meander, on property owned by Wonderland Stages, highway officials blasted directly through a soft sandstone cliff. Then, instead of building a bridge over the Fremont River and allowing the flow to continue along its natural course, they blasted out a new channel that cut off the meander and kept the river on the north side of the highway. The diversion takes the river on a new course over a small cliff, thereby creating a waterfall that has become a popular swimming hole for visitors and local youngsters. The old meander in wet seasons still holds water and provides habitat for a number of plant and animal species. Because this road cut and river re-channeling took place outside the monument, the National Park Service had no voice in the matter and apparently kept no records documenting this portion of Utah 24 construction. [59]

Scenic Drive

Once the new Utah Highway 24 was completed along the Fremont River, the old route through Capitol Gorge reverted to National Park Service control. As per the 1961 cooperative agreement and Capitol Reef's master plans, the road was closed off at the head of the Capitol Gorge narrows. The road from Capitol Gorge to Pleasant Creek remained open to vehicle traffic (Fig. 49). [60]

|

| Figure 49. 1962 Master Plan, monument roads and trails. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The increased traffic brought by the new highway led to a corresponding increase on the Scenic Drive as well. Approximately 40 percent of all visitors traveled at least part of this road, which was dirt south of Fruita. It was washboarded, rutted, and dusty most of the time, and the road turned to mud in the wet season. In July 1966, the National Park Service improved and graded Scenic Drive between Fruita and Capitol Gorge. Twelve new culverts helped solve the drainage problems. Superintendent Harry Linder considered the road to be "in excellent condition for visitor enjoyment with the exception of the dust which the summer rains should take care of." [61]

In 1969, Scenic Drive was scheduled to receive further attention, including chip-sealing the entire length from the campground to the mouth of Capitol Gorge. [62] However, the unexpected expansion of the national monument and all of its attendant worries evidently canceled that project, which would be revived in the spring of 1990.

Mission 66 Trails And Access Roads: 1956-1966

During 1955-56, various drafts of the Mission 66 Prospectus developed the initial philosophy toward new trails within the monument. A November 1955 draft stated:

As the area is difficult to access and due to the type of visitor, a large portion of the monument should always be reached by trails in preference to construction of roads. A note of caution, however, is necessary; we should not over-build on trails as they are very expensive to maintain in this country and changing patterns of use may mean too heavy a burden if trails buildings (sic) is overdone. [63]

This preference for trails over roads would become a predominant theme in Mission 66 development of the monument. The final, director-approved prospectus acknowledged that utility roads would have to be constructed to the new campground and possibly to Pleasant Creek. Nevertheless, trails would provide the primary access routes into the spectacular backcountry of the Waterpocket Fold. The prospectus continued:

Short trails to the natural bridges (sic) and some of the outlying canyons will be constructed to give safe access to hikers or horseback parties. These trails will be designed as to take visitors to vantage points. It is believed that at least one wilderness trail of low standard is justified to give access to the primitive area north of the Reef. This would enable those who wish to get into the true desert wilderness to do so with some effort. [64]

Trail mileage would significantly increase during the Mission 66 period from 1956 to 1966. In the 1956 estimates, only 8.6 miles of additional trails were planned. These included two miles added onto Broad Arch (Hickman Bridge) Trail, which would take visitors to Whiskey Spring and an overlook high above Fruita; 1.1 miles of trail into Cohab Canyon; and various walks and paths in the Fruita area. [65] Not listed were undeveloped trails along the bottom of Grand Wash and up to Cassidy Arch. [66]

By 1958, four miles of additional trails "to points of interest" were included in a revised development outline. [67] Then, in 1960, proposed total trail mileage in the monument was dramatically increased to 24.5 miles. This included seven miles of new construction and 17.5 miles of reconstruction or relocation. [68]

That same year, Superintendent Krueger raised the possibility that, since problems with purchasing the private inholdings needed for the new highway's right-of-way were delaying its construction, those funds could be shifted to trails and access roads. Krueger's first priority was the reconstruction and partial relocation of the Goosenecks Road, parking areas, and trail. Apparently, the road out to the goosenecks overlook had existed for some time, but there is no known documentation that gives an initial date for its construction.

As part of this same funding request in 1960, Krueger desired construction of the long-promised Whiskey Spring and rim overlook additions to the Hickman Bridge Trail, as well as rehabilitation of 1.9 miles of the Cohab Canyon Trail. Further trail work was also proposed for the previously unimproved routes to Cassidy Arch, Cohab Canyon spurs, through Pleasant Creek and up to the base of the Golden Throne. Unfortunately, no known record pinpoints exactly when these projects were initiated. [69]

The 1964 master plan drawings of established and proposed roads and trails show a total of 35.78 miles of trails within the monument. Which of these were improved trails, which were simply routes, and which trails were actually completed by 1964 is undetermined. [70]

Although trail construction records are sketchy, most trail building was apparently postponed until 1966. At that time, Superintendent Harry P. Linder reported, "The rehabilitation of the Cassidy Arch Trail was completed in July. This completes rehabilitation work on all but two trails which should be finished by end of summer. Everyone tells us the trails are in better shape than they have ever been." [71]

By October 1966, the Fremont River Trail was completed and work was begun on the Frying Pan Trail connecting Cohab Canyon with the Cassidy Arch Trail. [72]

By 1973, improved trails in the headquarters area of Capitol Reef National Park also included the three-mile Chimney Rock loop and a half-mile extension of the Fremont River Trail to the campground overlook. Unimproved routes included the narrows of Grand Wash and Capitol Gorge, along Pleasant Creek, out to Sunset Point off the Goosenecks access road, and through Spring Canyon to the north. Another traditional but unimproved route followed Sulphur Creek from the Chimney Rock parking area to the visitor center . [73]

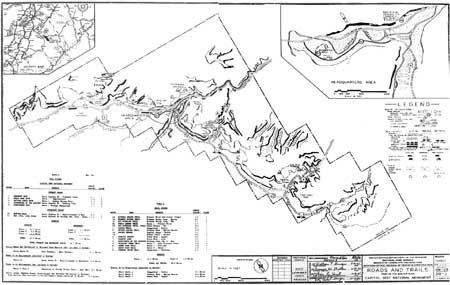

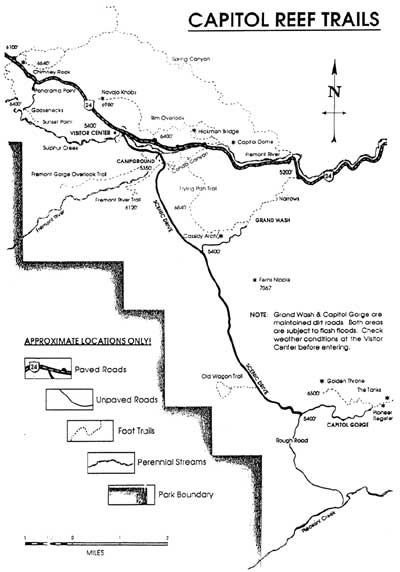

Additional trails were built by Capitol Reef rangers during the late 1980s and early 1990s. These included an extension of the Rim Overlook Trail another two miles to Navajo Knobs, new trails to a high point above the Fremont River Gorge west of the visitor center, and a three-mile loop trail following parts of the old Grover wagon road (Fig. 50).

|

| Figure 50. Capitol Reef trails, 1994. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Development of new roads and trails in Capitol Reef National Monument was hindered by rugged terrain and isolation. Yet, miles of road and trail work were completed in the equally rugged Zion and Bryce Canyon National Parks from the 1930s through the 1960s, suggesting that isolation was the more important factor delaying construction at Capitol Reef.

When the long-promised highway was finally constructed, circulation patterns within the monument changed significantly. The new highway brought an increasing number of visitors. With additional money and staff, Capitol Reef slowly extended its trail system, thereby enticing visitors to spend more time in the canyons or hiking to scenic view points. Fortunately, planners for Mission 66 and later developments in Capitol Reef had anticipated increased visitation. As of 1994, the roads and trails in the headquarters area, except for the most popular routes up to Hickman Natural Bridge and in the narrows of Grand Wash and Capitol Gorge, remain relatively uncrowded.

Post-Park Roads And Trails

Roads And Trails In New Park Areas: 1971-1973

When Capitol Reef National Park was established in December 1971, its managers inherited 48.5 miles of county roads, 13 miles of former Bureau of Land Management roads, and approximately 32 miles of four-wheel drive roads. There were no additional trails aside from backcountry routes used by ranchers, their stock, or wilderness explorers. [74]

The county roads included 25.6 miles to the north of Utah 24 and 22.9 miles in the southern portion of the new park. These county-maintained roads included the Caineville Wash and Cathedral Valley roads built in the 1940s (the Upper Cathedral switchbacks were cut around 1949), and the Hartnet and Notom Roads. [75]

It is unclear which 13 miles were built with Bureau of Land Management funds. In the North District, according to rancher Garn Jeffery, the two rough access roads from his ranch (often called Baker Ranch) and the Oil Bench road down Rock Spring Bench were improved by the BLM during the mid-1940s. [76] Those who built the road from the river ford up the bentonite clay hills to the Hartnet road are not clearly identified. Ward Roylance claimed that this road was built by the BLM during the mid-1950s. [77] Rancher Guy Pace, on the other hand, recalls that Wayne County, with his help, built the road during the late 1940s and early 1950s. More research is needed to accurately determine the history of the roads in the outlying areas of the park. [78]

The four-wheel drive roads presumably included the 13 miles of jeep track following Halls Creek south of The Post, as well as several dead-end spur roads in the North and South Districts, used for mining and grazing access. The ranching access roads included the Lower South Desert Overlook (originally built into the South Desert in 1958 for oil exploration), Upper Cathedral Valley line shack and corral, Gypsum Sinkhole and Lower Cathedral Valley access roads in the north, and the Swap Canyon and Red Canyon roads in the south.

Mining access roads included a few small spur roads off the South Draw road from Pleasant Creek to Bowns Reservoir; the Rainy Day Mine road off the Burr Trail; a spur into North Coleman Canyon from a Sandy Ranch road accessing the Oak Creek dam and canal; four-wheel drive routes from Dixie National Forest into Oak Creek Canyon; the Terry Mines road near Bitter Creek Divide; the 1956 oil exploration road past Jailhouse Rock into Little Sand Flat; and a connecting road into the Upper South Desert built in 1959 by seismographers, presumably looking for oil. [79]

Congressional Testimony And Requirements

Immediately after President Lyndon Johnson's presidential proclamation in 1969 expanded Capitol Reef to over 250,000 acres, an immediate outcry of protest arose from the area's traditional multiple-use operators. [80] Since access to many areas of the Waterpocket Fold was limited to a few dirt roads, users feared that some roads might be closed. During the May 31, 1969 subcommittee hearings over the monument expansion, South Desert rancher and Wayne County Commissioner Guy Pace stated:

With the present trend to put all national parks into natural wilderness areas, additional restrictions are placed on use of the parks. Road development in the area stops, and frequently existing roads and trails are blocked within the boundaries of these areas, and recreational expansion stops. We have had the experience in the old Capitol Reef National Monument of having scenic roads in the monument blocked. Capitol Gorge and Grand Wash have been closed to vehicle travel. Only those who have the time and energy to hike considerable distance can now enjoy this part of the park. [81]

As Pace implied, there was particular concern that the monument's expansion would terminate future road development.

The National Park Service attempted to placate road development advocates while defending the agency's management philosophy. The inherent conflict between these two objectives is expressed in a 1971 draft environmental statement issued for in-service use by Southern Utah Group General Superintendent Karl Gilbert. According to Gilbert, Capitol Reef should attempt to limit visitation into the fragile backcountry while at the same time promoting road improvements. [82] The final environmental statement provided a few more specifics on how this incongruous need for both better roads and protected resources would be managed:

Additional park roads are not proposed; however, the upgrading of existing roads is proposed. Generally this will be of environmental benefit to the area. The present roads are low standard and have been rerouted here and there to meet erosion conditions. Drainage structures are nonexistent and crossings of washes have been relocated at the whim of the individual maintaining the road. Flash flooding is commonplace. Great care will be used in determining the final location of these roads and in designing the roads so as to minimize adverse environmental impacts. [83]

One reason for the delay in formulating a roads and trails policy was the agency's unfamiliarity with the outlying regions of the proposed park. This delay, coupled with local concerns over roads, convinced sponsors of both the Senate and House bills to include a clause requiring a detailed transportation study for the new park. In November 1971, the congressional conference committee, which ironed out the discrepancies between the Senate and House versions, recommended that the Department of the Interior have sole responsibility for this "comprehensive" study and that it be coordinated with the studies for other National Park Service areas in the same region. The conference report specified, "Because of its importance to the future of the communities involved, the report and the recommendations are required to be completed and transmitted to Congress within two years after the date of enactment." [84]

The Department of the Interior seemed to have no objections to this requirement, provided that adequate funding was available. [85] Thus, with no apparent opposition, the following wording was included in the final enabling legislation for Capitol Reef National Park signed into law by President Richard Nixon on Dec. 18, 1971:

The Secretary, in consultation with appropriate Federal departments and appropriate agencies of the State and its political subdivisions, shall conduct a study of proposed road alignments within and adjacent to the park. Such study shall consider what roads are appropriate and necessary for full utilization of the area for the purposes of this Act as well as to connect with roads of ingress and regress to the area. [86]

Similar wording was also included in the legislation creating Arches National Park and expanding Canyonlands National Park earlier in 1971. Notably, however, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area legislation was not passed until the following year and was therefore not formally involved in this particular road study.

Transportation study projections and analyses are often ignored in the political arena. By the 1970s, any road development in such a sensitive area as southern Utah was bound to lead to intense conflict that would be resolved either through compromise or court action. Thus, the only historical significance of such a transportation study would be contemporary listing of various options.

1973 Transportation Study

A professional services contract was issued to Environmental Associates of Salt Lake City, Utah to complete a joint transportation study for Arches, Canyonlands, and Capitol Reef National Parks and separate master plans for each. Unfortunately, no further documentation, such as a scope of work, has been found to indicate what the National Park Service wanted included in this study, how much money was authorized, or whether the project should be done in-house or under contract. Since the locations of Capitol Reef's records from the early 1970s are unknown, there is also no documentation of the park's and region's reactions to the joint transportation study when it was issued at the end of 1973. [87]

It is known that the recommendations concerning Capitol Reef National Park were never approved. Further, the 1973 master plan for Capitol Reef, prepared by the same consulting firm and including the same detailed transportation analysis, was rejected as unsatisfactory. [88]

In developing the joint transportation study and the separate master plans for each area, Environmental Associates evaluated existing and potential regional road systems and visitor services. In conjunction with the evaluations, the consultants also considered the various proposals submitted by the Utah State Department of Highways and various federal agencies, including the National Park Service. The purpose was to derive transportation management proposals that would enhance visitor experience, avoid congestion, maximize capitol investment, and minimize non-visitor traffic. The goal seems to have been to combine the various proposals into an acceptable compromise. [89]

The Utah State Department of Highways proposals were, naturally, the most far-reaching. Ever since the tourist potential of southern Utah was first realized in the early 1900s, state planners, often in cooperation with the National Park Service, had advocated building scenic highways through the rugged and beautiful terrain. By the 1970s, the state was pinning its hopes on a spectacular Lake Powell Parkway from Glen Canyon City through Canyonlands National Park and across Cataract Canyon to Moab. Other paved roads, some of which were of more immediate concern to Capitol Reef, would act as arteries to this highway through the heart of the Colorado Plateau. The new roads and upgrades proposed by the state included paving the Boulder-Bullfrog road and Utah Highway 12 over Boulder Mountain. The plan also called for rerouting and paving a road from Fremont Junction to Notom Road, which in turn would be paved all the way to Bullfrog Marina on Lake Powell. If any one of these roads was completed as planned, it would significantly change the volume and nature of visitation to Capitol Reef National Park. [90]

The consultants' recommendations, termed the "National Park Service Proposal," called for substantially less. According to the contractors, Capitol Reef managers should strive for the worthy but still contradictory goals of increased access and minimal visitor impact. Specifically, the joint transportation study recommended that the section of the Notom-Bullfrog road inside the park boundary be paved, that the Burr Trail be upgraded to an all-weather gravel road, and that the existing dirt road from Utah 24 north to Lower South Desert Overlook be widened and paved. [91]

In its 1973 master plan for Capitol Reef National Park, Environmental Associates recommended further road improvements. These included a new highway from Fremont Junction southeast to Hanksville, as an alternative to the Fremont Junction-Bullfrog paved road proposed by the state. Another was the possible paving of the entire Notom-Bullfrog Road and the Boulder-Bullfrog Road (except for the Burr Trail, which would be graveled). In the park's North District, a one-way, paved loop road should be constructed to follow the existing dirt roads from Utah 24, through Cathedral Valley, and then over the Hartnet. The plan also recommended that Scenic Drive be improved and paved, that additional trails be built in the Fruita area, and that the jeep track along Halls Creek be restricted to foot and horse traffic. [92]

Thus, only two years after Capitol Reef National Park was created, there was a wide range of ambitious proposals to improve the roads and trails in the newly expanded area. The plan proposed by Environmental Associates did achieve the goal of blending the various options into a compromise proposal. Yet, even if its recommendations were less than the state or counties desired, they were still too ambitious for the National Park Service -- especially since the park was so new, so little was known about its existing resources, and the political climate in southern Utah was so contentious.

Wilderness Constraints

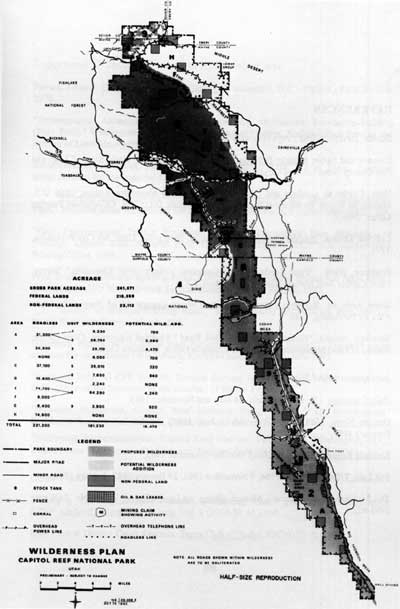

In addition to the transportation study, Capitol Reef's enabling legislation required that a wilderness study of the new park be completed within three years. [93] Any extensive roadless wilderness within Capitol Reef would obviously restrict road construction or circulation changes proposed in the 1973 master plan and transportation studies. While the wilderness proposals took the transportation and master plans into consideration, there seems to have been no actual coordination between the National Park Service wilderness study and the privately contracted transportation and master plan.

In November 1974, after several preliminary proposals and public hearings, the National Park Service formally recommended that 179,815 acres of roadless wilderness be designated in Capitol Reef National Park. There were to be nine distinct wilderness units, each separated by a road or proposed utility corridor (Fig. 51). The recommendation specified:

No existing roads that are to remain or routes of proposed roads are included in the proposed wilderness. However, a number of old roads not needed for park use are included. There are also many vehicle tracks associated with mining or seismic exploration during the uranium boom of the 50s. While too numerous to show on maps, they also lie within the proposed wilderness. All of these are to be obliterated and the land restored to as natural an appearance as possible. [94]

|

| Figure 51. Proposed Wilderness, 1974. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Two other proposed roads in the vicinity of Lower Muley Twist Canyon were also rejected, due to their tremendous cost and potential resource destruction. These roads, routes Q and V on the 1974 Proposed Wilderness Map, were initially recommended as part of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area enabling legislation in 1974. They were summarily rejected in the Capitol Reef Wilderness Plan and were never seriously considered again. [95]

While a wilderness plan for Capitol Reef National Park has never been formally approved, it is the stated policy of the National Park Service to manage any proposed wilderness areas as if they were designated wilderness. Later additions in 1984 mean that management is now empowered to restrict road construction from the nine proposed wilderness areas that make up 90 percent of Capitol Reef National Park. [96]

Because of this policy, there have been only a few times when road machinery was used in the backcountry. In 1976, a bulldozer was illegally brought in to clear the Oak Creek stock driveway, and in 1986, Superintendent Robert Reynolds reluctantly allowed the reconstruction of two stock ponds in the South Desert area of the North District. [97] In reality, the wilderness recommendations have had more of an impact on roads and trails in Capitol Reef National Park than either the 1973 master plan or transportation study.

By the end of the 1970s, little road and trail building had occurred since the park's creation at the beginning of the decade. This was mostly because park-wide development plans were postponed until resource surveys were completed. [98] Meanwhile, the 1974 wilderness recommendations mandated that 75 percent of Capitol Reef National Park be managed as roadless wilderness. That stance prevented road-building and ensured gradual deterioration of many of the old grazing and mining jeep trails. By the early 1980s, however, preparation of the first general management plan for the park, right-of-way issues, and the growing Burr Trail controversy would push roads and trails management at Capitol Reef into a more active phase.

1982 General Management Plan Proposals

In October 1982, Capitol Reef National Park finally had a comprehensive, director-approved General Management Plan (GMP). [99] Because of their significance to park management, roads and trails were prominently featured in the 1982 GMP. Until a new general management plan is finished and approved sometime in 1998, the 1982 plan provides the operational guidelines by which Capitol Reef National Park manages its resources.

Overall, the 1982 plan instructed park managers to seek an active role in all future road developments. It stated:

It is not in the interest of the Park Service to finance improvements of the through-roads in the South and North districts during the lifetime of this plan. Should the county and/or state propose improvements in any of these roads, the Park Service will retain a voice in the design of these roads and in the regulation of traffic on them within the park to protect park lands, resources, and visitors. [100]

This statement meant that park managers would work with county and/or state road planners, but would retain the National Park Service's right to determine final road alignments, speed limits, vehicle size limitations, and permitted periods of use. [101]

The 1982 general management plan called for construction of one new road, the paving of another, and several new trails, all in anticipation of increased visitation. A total of five action or plan alternatives were considered during the planning process. What follows is a description of roads and trails existing in 1982, and a summary of the desired changes expressed in the general management plan. (See that document for a complete table of alternatives).

A. Headquarters District

Current Conditions. Utah 24 was still the only paved road through the park. Along this road there were 11 scenic pullouts, including the graveled Goosenecks/Panorama Point spur road constructed and maintained by the National Park Service. Scenic Drive was a paved, two-lane road to the campground, with a one-lane bridge over the Fremont River. South of the campground, the road became a two-lane gravel road to Capitol Gorge, where it then reverted to a graded dirt road. The road to Pleasant Creek was a narrow, graded dirt road. There was also the one-mile dirt spur road into Grand Wash, plus seven scenic pullouts. The entire Scenic Drive was owned and maintained by the National Park Service. [102] The South Draw jeep track that runs south of Pleasant Creek and continues on to Lower Bowns Reservoir in Dixie National Forest is not mentioned in the GMP.

There were approximately 16 miles of constructed or marked trails in the Headquarters District. These included maintained trails to Hickman Bridge, Chimney Rock, Goosenecks, Cassidy Arch, along the Fremont River, and up to the base of the Golden Throne. Other routes, such as those along the bottom of Grand Wash and Capitol Gorge, were unmaintained routes. Some, such as like the Frying Pan Trail, were marked by rock cairns. [103]

Preferred changes to Headquarters District. The only proposed change was to widen and pave spur road out to the Goosenecks Overlook at a cost of $228,000. Alternative 3 had also proposed spending almost $6 million to pave the Scenic Drive as far as Pleasant Creek, but the preferred alternative would keep the Scenic Drive gravel. [104]

The only new trail proposed was a two-mile loop through the historic Fruita area, connecting the campground with the picnic area, orchards, schoolhouse, Hickman Bridge trailhead, and visitor center. It was also proposed that trailhead parking be added at Pleasant Creek to encourage use of the canyon route, as well as more backcountry use in general by backpackers and equestrians.

B. South District

Existing Conditions. The only South District roads mentioned in the GMP are the Notom and Burr Trail roads, which intersect near The Post, and an unmaintained four-wheel drive road up Upper Muley Twist Canyon to the Strike Valley viewpoint trailhead. The Burr Trail and lower section of the Notom Road were maintained by Garfield County; the portion of the Notom Road north of the county line was maintained by Wayne County. Other known roads, such as the Halls Creek jeep road and the Rainy Day, Terry, and North Coleman Canyon mine access roads were not mentioned, most likely because they were considered permanently closed. All trails in the south district were unmaintained, backcountry routes. [105]

Preferred Changes. No major alterations were seen for the Notom Road. It was proposed that small, five-car parking areas be added at Burro, Cottonwood, and Five-Mile washes and Sheets Gulch. While it was assumed that some change would occur to the Burr Trail, no specific alternatives were considered in the GMP. According to the general management plan, the anticipated increase in visitation resulting from the road's improvement might necessitate construction of a permanent contact station, employee housing, and a primitive, expandable campground at the foot of the Burr Trail switchbacks. [106]

The only new road proposed anywhere in the park would change the access to Strike Valley Overlook. The plan recommended that the old road through Upper Muley Twist be turned into a foot trail, and that a new, 2.5-mile gravel road be constructed from a point further west on the Burr Trail to a 15-car parking area at the Strike Valley trailhead. Gravel would also be applied to the rough, often impassable road over Bureau of Land Management land out to the Brimhall Bridge/Halls Creek Overlook Trail. New trails in the South District would be built at Bitter Creek Divide, with a spur trail to the Oyster Shell Reef. [107]

It should be emphasized that all these improvements were contingent on road improvements and the corresponding increase in visitation. Until the roads were upgraded, the NPS preferred that little change occur in the South District of Capitol Reef.

C. North District

Existing Conditions. The two main access roads into the North District were the Caineville Wash and Hartnet roads. Both were graded dirt, maintained by Wayne County. Like the roads in the South District, they were considered impassable when wet, but the North District roads were much rougher and passable only to high clearance two-wheel or four-wheel drive vehicles. Short spur roads led from the Hartnet road to Lower South Desert Overlook, the Upper South Desert Viewpoint, and the Cathedral Valley Viewpoint. Spurs off Caineville Wash Road led to lower Cathedral Valley and the Temples of the Sun and Moon. It is assumed that these roads were also maintained by the county. The access roads up to Fremont Junction to the north or over Thousand Lake Mountain to the west are also mentioned. [108] By 1982, the former roads into the South Desert were closed and off-road vehicle use was prohibited.

Preferred Changes. Unlike the 1973 master plan proposals, no new development or road improvements were sought for the North District. Visitor access would be limited to the existing roads and hiking routes from Lower South Desert Overlook to Jailhouse Rock, from the Hartnet Road out to Middle Desert Viewpoint and the Lower Cathedral Valley Overlook. An additional trail was planned around the Wall of Jericho in Upper Cathedral Valley.

1994 Conditions

The 1982 Capitol Reef General Management Plan called for few significant changes in terms of roads or trails. The new Strike Valley access was the only new road planned, and only the short Goosenecks access was recommended to be paved. New trails would be limited to increasing the marked backcountry routes and creating a new, two-mile loop trail through Fruita.

Since 1982, little has changed in the still-isolated backcountry areas of Capitol Reef National Park. There are a few widened trailhead parking areas and improved trail markings in Upper and Lower Muley Twist Canyons in the South District. There is also a new dirt access road into the Oak Creek trailhead, necessitated by complaints from Sandy Ranch that the old access road crossed its property. [109]

In the north, a new trail was constructed by former Backcountry Ranger Larry Vensel out to the Wall of Jericho in Cathedral Valley. There are have been no other significant changes to the North District's roads or trails.

While Scenic Drive was paved in 1987 as far as Capitol Gorge, the Goosenecks Road is still gravel. New trails to Navajo Knobs and the wagon road loop and better access to Spring Canyon have increased trail variety in the headquarters area. Rangers have also marked a new trail from the highway across from the visitor center going up behind the "castle" formation. Surprisingly, after a steady increase during the early 1980s, backcountry use in the park has remained relatively stable during the 1990s.

The History Of The Boulder-Bullfrog

Road

The 66-mile-long Boulder-to-Bullfrog Road that crosses the southern part of Capitol Reef National Park has developed into one of the most controversial roads issues in recent history. Because of the spectacular switchbacks named for rancher John A. Burr, the entire road is commonly called the Burr Trail. This road has had more of an impact on the contemporary management of Capitol Reef National Park than any other, with the possible exception of Utah Highway 24.

The following summary history of the Boulder-to-Bullfrog Road was taken from the author's "Boulder-Bullfrog Road: Comparison of Sections Before and After 1942," which was later abbreviated and included in the 1993 "Environmental Assessment for Road Improvement Alternatives, Boulder-to-Bullfrog (Burr Trail)" (see Fig. 46). [110]

Section 1 - Boulder To Capitol Reef National Park:

1880-1942

Until 1942, the main reason anyone ever went east from Boulder to the Circle Cliffs was to trail livestock. Given the lack of motorized transportation in eastern Garfield County, it is easy to understand why there was no road on the stretch from Boulder to what is now Capitol Reef National Park until after World War II.

According to Garfield County ranchers, a well-used cattle trail went east- southeast from Boulder across Deer Creek, into The Gulch, and then through Long Canyon and onto the flats at the base of the Circle Cliffs. This trail probably looked similar to other cattle trails in the area, varying in width according to the terrain. If the livestock were being driven over the more wide open benches of pinyon and juniper vegetation, the trail could have been over 50 yards wide in places. When the trail descended steep sandstone ledges toward canyons, such as Deer Creek and The Gulch, the animals would line up and move single file. [111]

Unfortunately, it is impossible to document exactly where the cattle trails lay in relation to modern roads. Places where some of the trails descended into canyons are still visible today. But in more vegetated areas and in flood-cleansed wash bottoms, there is little to follow. Therefore, it is unclear if the road from Boulder to Long Canyon follows the exact alignment of a traditional cow trail.

It is known, however, that the Boulder to Long Canyon route was not the preferred livestock driveway by the early 1930s. Instead, the route agreed upon by cattle ranchers "follow[ed] the road through Boulder thence down through Draw east of Durfey Bench to Deer Creek, Cross Steep Creek Bench to Steep Creek, down [S]teep Creek to the Gulch and on to Egg Box Canyon." [112] This route was improved in 1935-36 by the new Grazing Services and Emergency Relief Administration, in cooperation with affected ranchers. Wagons of supplies and tools could get up The Gulch and out Egg Box Canyon to the improved Brinkerhoff Spring and other water holes at the northern end of the Circle Cliffs by this route. [113]

In either 1935 or 1937, a crude wagon road was blazed up Long Canyon's wash bed and out into the Circle Cliffs basin as far as Horse Canyon. Wagons and horse or mule teams pulling dirt scrapers were used to make the boulder-strewn wash bed accessible by wagon. It is unclear what the road looked like between Long and Horse Canyons, but the switchbacks on the 1953 United States Geological Survey (USGS) topographic quad map and the current alignment are definitely different. [114]

Significantly, no county road east of Boulder is in evidence on the official Garfield County road map of 1938. Thus, the wagon road east from Boulder through Long Canyon must have been extremely rough and seldom used. [115]

By 1942, the section of the Boulder-Bullfrog Road east from Boulder to Capitol Reef National Park included a wagon road, in approximately the same alignment as today, southeast from Boulder across Steep Creek Bench. Here, one either descended Steep Creek or went south into The Gulch at its junction with Long Canyon. Once in the canyon bottom, a crude wagon road followed the canyon wash bed up to the head of Long Canyon and descended to Horse Canyon, where the road stopped. This road, like the trails before, was still used primarily for moving livestock. There is no evidence of anything but livestock trails across the Circle Cliffs basin along today's park boundary.

Nor is it clear if any livestock trail followed close to the Boulder-Bullfrog Road's present alignment. What is clear is that the route through Long Canyon was only one of many into the Circle Cliffs. [116]

Section 1: Post-1942

After World War II, BLM range improvements and the uranium mining boom caused additional work on this section of the Boulder-Bullfrog Road. Improvements were made to the wagon and, later, jeep road in 1947 and 1950. Yet, the road continued in the bottom of Long Canyon.

The 1951 Garfield County road map is, unfortunately, not very detailed, but it does indicate that the road out of Long Canyon had not yet progressed much past Horse Canyon by the end of 1950. The road appears to be in roughly the same alignment as it travels southeast from Boulder, across Deer Creek, and up onto Steep Creek Bench. An additional switchback into The Gulch is indicated on the 1951 map, that is not shown on the 1964 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) quad. On the 1951 Garfield County map, no drainage is indicated as Long Canyon. Nevertheless, the 1951 map and a 1953 USGS quad map both show a road following the same general direction out of Long Canyon, crossing Horse Canyon, branching, and then ending. Evidently, as of 1951 there was still no connection with either the Silver Falls-Lampstand Road, which runs north/south through the heart of the Circle Cliffs, or with the Burr Trail to the east. [117]

The 1953 USGS topographic maps of the area compiled from aerial photos taken a year earlier show a four-wheel drive road all the way from Boulder, through Long Canyon and across the Circle Cliffs to the present western park boundary. This road would be used throughout the 1950s by stockmen driving cattle, by hundreds of uranium miners and their ore trucks, and by a few tourists, too.

Further improvements and realignments of the road were made from 1961-72. These included a new dugway down into The Gulch, partial realignment of the road through Long Canyon and into the Circle Cliffs, and a new cut-off near the Lampstand Road. [118]

The road remained essentially unchanged from 1976 to 1988, except for minor improvements and maintenance. From 1988-91, major development of the road included improving the stretch into The Gulch, and general widening, realigning, and chip sealing of the 26 miles between Boulder and Capitol Reef's western boundary. A new bridge was built over Horse Canyon, but the wash crossings over Deer Creek and The Gulch were only slightly improved.

By 1995, the section of the Boulder-Bullfrog Road from Boulder to Capitol Reef was quite different from the rough wagon road of 50 years earlier. The significant changes in alignment are documented above. It is the traveler's experience, however, that has really changed. The winding, narrow dirt road that took the adventurous traveler through the incomparable beauty and isolation of the Circle Cliffs region has become a smooth, curving highway accessible by any type of vehicle.

Section 2 - Western Capitol Reef Boundary To Eggnog

Junction: 1880-1942

The steep, 600-foot slickrock and scree slope on which the Burr Trail road is located is the only relatively easy crossing over the entire southern Waterpocket Fold. The route was probably used initially by American Indians, but was later improved by sheep and horse ranchers to allow their livestock to move between summer and winter ranges. The narrow, precarious livestock trail probably began in the Burr Canyon wash bottom to the east of the slope and then started up the north side before beginning to switchback across the slope to the rim above. [119]

Once at the top, herds were driven in many directions within the Circle Cliffs. Sheep were driven to the north, up around the Lampstand and Corner Flats. Though documentation is absent, this livestock trail probably went through the Studhorse Peaks, just as the modern road does. This is the most likely route because the cliffline to the north and east of the Studhorse Peaks would have prevented travel in those directions. Any other route would have meant a lengthy detour to the south and west before looping back around toward the Lampstand. [120]

Less than a mile from the bottom of the switchbacks, the trail along the wash bottom would have intersected with the Notom supply road coming from Capitol Gorge and down the eastern side of the Waterpocket Fold. [121] This supply road was used by wagons since the 1880s to bring food, water, and other necessities to those tending livestock in the Circle Cliffs and Henry Mountains. Supplies were left in large, wooden storage boxes located near The Post, about two miles south of the Burr Canyon Wash-Notom Road Junction. Herders in the Circle Cliffs would go down the Burr Trail switchbacks to The Post, load up their pack mules with supplies, visit with others there for the same purpose, and then head back up the trail. [122]

The Notom Road continued past The Post, cut between two ridges to the east (passing the modern Capitol Reef boundary in one mile), and then went south-southeast for another seven miles to the present Eggnog Junction. From there, the old wagon supply road headed east and up unto the base of Mt. Hillers in the Henry Mountains.

This section of the Boulder-Bullfrog Road did not change much from 1880 to 1942. There is no recorded evidence of road or trail improvements along this stretch during that time. The physical description of the road is substantiated by two maps. The topographic map of the Henry Mountains region surveyed between 1935 and 1939 clearly shows the Notom supply road -- almost identical to its present alignment -- as a double-dashed line going south past The Post and continuing on past today's Eggnog Junction. The Burr Trail is clearly labeled and marked as a switchback trail ending at the top of the Fold. There are no indications of trails continuing to the west from the top of those switchbacks. [123]

The September 1939 map of Henry Mountain and Boulder Unit, Utah Grazing District No. 5 also represents the Notom Road with a double-dashed line road south from Notom. The Burr Trail is also labeled and represented by a straight, double-dashed line due west for about one mile before stopping. This map does not indicate switchbacks on the Burr Trail or the part of the road heading off toward Eggnog Junction. [124]

From 1880 to 1942, the physical characteristics and use of the Burr Trail switchbacks and section of the Notom road from Burr Canyon past The Post to Eggnog Junction did not change. There are two likely reasons why a wagon road was not cut up the Burr Trail. First, the slope was too steep to cut a road into with the roadbuilding technology available at the time. Second, a wagon road was already available through the rough, seldom-used, Halls Crossing route through the southern end of Muley Twist Canyon. [125]

Section 2: 1942 To Present

The most significant alteration to the Burr Trail occurred in 1948 when the Atomic Energy Commission brought in a caterpillar tractor to cut a crude road up the Burr Trail switchbacks, improving access to uranium claims within the Circle Cliffs. [126] It is still unclear whether this new "road" followed the old livestock trail up the switchbacks or how far west of the switchbacks this road continued when it reached the top. It is most likely that at this time the route was diverted from the Burr Canyon wash bed onto the southern bench.

At the base of the steep slope, it appears the tractor began at the north side (exactly where the trail began) and then cut immediately back to the south to create the first switchback. A small section of what maybe the old trail is still visible, climbing some yellow tinted sandstone on the north side between this first and second switchback. If so, it is the only visible remains of the old trail.

Once on top, the 1948 road most likely followed the Muley Twist wash bottom just as the present road does, since there is no physical evidence of any other road. The original route after the road leaves Muley Twist Wash is undetermined. According to the 1953 Wagon Box Mesa topographic map, the route (still marked as a single dashed line signifying a simple pack trail) follows a side wash coming in from the west. But close examination of this presumed route shows no clear evidence of any roads except ones leading south to the Rainy Day mines. Since this road would have been used extensively by miners and ore trucks by 1952 (when the aerial photos for the USGS map were taken), and since there is no evidence of major road improvements until the 1960s, the road should still be visible where it followed and crossed this drainage. Therefore, either the map is wrong or the road was not built west of the Burr Trail until after 1952. [127]