|

Capitol Reef

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 7:

MISSION 66 DEVELOPMENT: 1955 TO 1966

Management of Capitol Reef National Monument changed considerably once the paved road was finally completed in the early 1960s. It is no coincidence that at the same time the road construction through the Fremont River canyon finally became affordable, money was also available to buy out most of the private lands in Fruita and build a visitor center, utility building, a modern campground, and interpretive shelters.

The monument was developed during a period of intense visitation pressure on the entire national park system. As millions of post-war vacationers took to the roads, the inadequate facilities in many parks and monuments were overwhelmed. The National Park Service and Congress responded to these pressures by increasing appropriations for the development of roads, buildings, and campgrounds and by re-evaluating the private lands and concessions within the national park system. This enormous project, begun in 1955, was dubbed "Mission 66" because it was to be completed by the National Park Service's 50th anniversary in 1966.

For Capitol Reef National Monument, the results were significant. The desperately needed facilities built to accommodate the anticipated crowds transformed the park. Since the monument's creation, the lack of National Park Service investment had allowed traditional uses of the land by residents, ranchers, and the occasional visitor to continue. Isolation and minimal facilities had been the only real safeguards for the monument's protection. After Mission 66, no longer would the single employee, the superintendent, be just another neighbor at Fruita. The increase in traffic, buildings, budgets, and personnel would finally put the National Park Service in control of the monument, making it an influential and sometimes criticized part of the community. Capitol Reef National Monument was finally becoming a true, fully functioning unit of the National Park Service. While the developments were in large part what local residents had wanted, the resulting management changes were not always understood or appreciated.

Mission 66

Post-World War II America was a rapidly growing, affluent, automobile-crazed country. Better highways and increased leisure time made summer trips available to virtually every American. By the mid-1950s, it seemed every American was visiting the national parks. Visitation increased from 6 million people in 1942 to 33 million in 1950, 50 million in 1955, and 72 million in 1960. [1] Yet, few facilities had been constructed in the parks since CCC days, and appropriations (all but eliminated during World War II) had been curtailed again during the Korean conflict. Director Conrad L. Wirth, who assumed the helm of the National Park Service in 1951, had finally seen enough of the deteriorating conditions. He called for a comprehensive study of

all the problems facing the National Park Service--protection, staffing, interpretation, use, development, financing, needed legislation, forest protection, fire -and all other phases of park management. [2]

President Eisenhower enthusiastically endorsed the study and Congress responded generously to the resulting Mission 66 plan. More than one billion dollars were allocated to the national parks from 1956 to 1966, to construct new roads and trails, visitor centers, maintenance, and employee housing, and to acquire private lands and water rights. The Mission 66 project also upgraded resource management programs and re-evaluated present and future concessions within the parks. It was proposed that some parks and monuments be free of any private lodging or services within their boundaries. [3]

Mission 66 was a thorough master plan for the entire National Park Service, rather than the usual piecemeal, year-to-year planning effort. Mission 66 initiated a period of intense, National Park Service development paralleled only by CCC construction effort of the Great Depression--and even the CCC era didn't see a complete evaluation of overall park management, as occurred during Mission 66.

Not everyone concurred that Mission 66 development was good for the national parks. Objections were raised by individual senators who wanted more for their districts, and by a fledgling environmental movement that saw pristine resources being compromised for mass accessibility. Writer Edward Abbey, for one, earned his reputation in part with his protests over the paved roads and other improvements sought in the master plans of the southwestern parks. [4]

Controversy notwithstanding, the impact of Mission 66 was significant. By the mid-1950s, the park service had determined that the increasing crowds must be accommodated with a wide range of facilities and resources to make each visit as enjoyable and educational as possible. The growing traffic and overcrowding problems could not be ignored. The National Park Service hoped that by enhancing visitor experience, and thus appreciation, visitors would treat resources with more respect. These changes were bound to be controversial to both the fledgling environmental movement and traditional-use advocates.

The earliest known documentation relating to Mission 66 plans for Capitol Reef is an answered questionnaire from Zion Superintendent Paul Franke to Director Conrad Wirth, regarding needs and problems at each park. While discouraged over the inadequate amount of time allotted to conduct the survey, Franke listed numerous current problems and future needs at Capitol Reef. On his list are continued uranium mining and grazing. Of most concern, though, were private lands at Fruita and directly outside the monument at Pleasant Creek. These properties, according to Franke, "present[ed] the most serious threat...to hinder public use and destroy the area character." A case in point was the "most undesirable and messy" Capitol Reef Lodge. [5]

The bare necessities for Capitol Reef were facilities to meet the demands of an anticipated 300,000 visitors traveling on the paved highway by 1966--a 500 percent increase since 1956. Recommended developments included a visitor center and a larger campground along with self-guiding trails, parking, picnic areas, and wayside exhibits. Franke believed that the monument would continue to see almost exclusive day use, but predicted that this would soon overlap into the spring and fall "shoulder" seasons. Interestingly, while Franke saw the need for headquarters development to meet the increasing crowds, he did not view these crowds as an immediate threat to Capitol Reef's resources. Franke believed that "the brilliant colored cliffs and sparse vegetation can be visited and used by many thousands of tourists without damage." [6]

Franke believed that human use of the monument could be limited by simply regulating the kinds and areas of development. In 1955, Franke specifically saw the need to broaden the average tourist's exposure to the monument. He wrote:

The thinking now is that additional opportunities should be provided to the public to make different kinds of use than that of merely riding through the area in automobiles. The development of trails, parking and camping facilities along with an interpretive program encourage greater use. [7]

Attempting to make the average visitor stay longer than a couple of hours in the park would prove to be one of the most difficult management problems for many years to come.

This ability to anticipate impacts instead of reacting to them makes the Mission 66 plans for Capitol Reef National Monument different from those of many other units of the national park system. In the more popular parks, Mission 66 development responded to already overcrowded conditions. Capitol Reef, on the other hand, had the luxury of planning so that future visitation pressures could be appropriately channeled.

The Road is Coming

Before plans could be made, however, the paved road had to be constructed. The final six miles from the Twin Rocks formation near the western park boundary to Fruita was begun in September 1956 and was finished in June 1957. [8] For the first time, people could travel all the way into Capitol Reef's headquarters area by paved road. Travel through the rest of the monument would continue to be on rough dirt and rock until 1962. The new road's impact on the area was seen not only in the increased traffic numbers (67,500 total in 1956, of which only 6,200 signed the register) but on the local scene as well. The large number of workers staying in the Capitol Reef Lodge and the Gifford Motel through the winter increased demand for limited water supplies.

Meanwhile, the road's construction, according to Superintendent Kelly, was adversely affecting the headquarters area. Not only did irrigation ditches have to be re-routed, but deep road cuts made the ranger station all but invisible, and "a large number of very beautiful shade trees were removed, which change[d] the appearance of this green oasis." [9]

Once the road was paved to Fruita, the route from there had to be decided. The two alternatives for the paved highway through Capitol Reef were 1) through the Fremont River canyon, the park service preference; or 2) to continue south from Capitol Gorge and go through the Pleasant Creek drainage, which was the state's preference. [10] Utah's preference for the Pleasant Creek route may have been based on the desire to connect as many state sections by road as possible. After a good deal of negotiation, however, the state determined that it would be cheaper to have the federal government pay for six miles of road through the Fremont River canyon than to finance, itself, some 15 miles of construction through Pleasant Creek. [11]

Before the road could be built through the Fremont River canyon, however, another three years of surveys and negotiation with Fruita residents were necessary. Meanwhile, Capitol Reef saw its first change in superintendents.

Kelly's Last Years At Capitol

Reef

The uranium boom at Capitol Reef National Monument ended in 1956, leaving the Yellow Canary and Yellow Joe mines next to the old Oyler Tunnel the only active claims into the 1960s. The constant battle with prospectors all but over, Superintendent Kelly spent most of his time meeting visitors and doing what he could to protect the monument's resources and improve its facilities. By the mid-1950s, he had a seasonal ranger every summer and a couple of maintenance men available when needed. Yet, until Grant Clark arrived in May 1958 as the first permanent ranger, Capitol Reef was for the most part still a one-man operation.

Kelly often mentioned in his monthly reports that magazines such as Arizona Highways, Sunset, and Travel were writing articles promoting Capitol Reef and the surrounding areas. The increased visitation encouraged by this publicity and by the better roads was consuming most of Kelly's time. Larger issues such as boundary adjustments and the impending road construction were mostly handled at the coordinating superintendent's level at Zion National Park or from the regional office in Santa Fe.

Due to his age and declining health, Kelly was beginning to curtail his activities at Capitol Reef at the same time Zion National Park and the regional office were becoming more active in planning the monument's future developments. In 1956, Kelly wrote in his diary:

My health is slowly failing, although the doctor can find nothing wrong. Have no appetite and no energy. My eyes are also failing and I won't be able to drive for very long unless I can have a radical correction. May have to leave before 1960, but have no plans. [12]

Kelly retired in February 1959 at the age of 70, after 15 years at Capitol Reef: six years as a virtual volunteer custodian and almost nine years as a paid employee. Despite his lack of National Park Service experience (Capitol Reef was his only duty station), he served the monument and the service well. Kelly's difficulties usually resulted from occasional disputes with his Fruita neighbors. In examining his overall record, however, he single-handedly protected the monument's resources throughout its earliest years, most notably during the uranium boom of the mid-1950s. Charles Kelly planted the seeds for later growth at Capitol Reef. Yet, the increasing developments, budget, and personnel brought by the growing crowds were changing Capitol Reef from the quiet, isolated "Red Rock Eden" of Kelly's era. It was now time for more experienced managers to handle the increasingly complicated decisions affecting a rapidly evolving Capitol Reef National Monument.

William T. Krueger became the new superintendent of Capitol Reef on April 1, 1959. Krueger was well acquainted with the monument since he had spent most of his time in the National Park Service working at Zion and Bryce Canyon National Parks, and had been superintendent at Cedar Breaks National Monument. He spent a year as chief ranger at Saguaro National Monument in Tucson before transferring to Capitol Reef. Krueger was one of the new, college-educated career employees that came out of the military at the end of World War II. He was a native of Bingham Canyon, Utah, and had received his Bachelor's degree in forest management from Utah State University. [13] In contrast to Kelly, Krueger was Mormon. He and Ranger Grant Clark were also active in secular organizations, such as the Lion's Club. From his reports and correspondence, he appears to have been very business-like and concerned about Capitol Reef's resources. As the superintendent responsible for implementing the Mission 66 improvements at the monument, Krueger's legacy is almost as profound as Charles Kelly's. After his six years at Capitol Reef, Krueger moved on to Golden Spike National Historic Site, from which he retired in 1973. [14]

While he was an efficient manager, Krueger struggled with the local population over the way private landholdings were purchased and the manner in which Capitol Gorge was eventually closed. Kelly, who disapproved of many of Krueger's decisions, nicknamed the new superintendent "Kaiser William."

To be fair, no manager could have presided over such rapid change without drawing some complaints. Local residents wanted park development and the prosperity it could bring to Wayne County, yet they also resented the change to the habitual, traditional uses of the monument's land that a prosperous, tourist economy would necessitate. Perhaps the most resentment was generated by National Park Service purchase of private landholdings.

Acquiring The Private

Inholdings

The dilemma over what to do with the small tracts of private land in the orchard farm community of Fruita had troubled National Park Service officials since the monument was first proposed. The first boundaries had even excluded Fruita. The early master plans had, at first, recommended the immediate purchase of all the private lands, then later concluded that they posed no imminent threat. [15]

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the limited number of tourists and the correspondingly minimal agency appropriations enabled Fruita to continue much as it always had. The social makeup of Fruita, however, was changing from solid Mormon to a mix of traditional families, non-Mormon retirees, and tourist operations residing under the newly imposed rules of the National Park Service. First to move in was Doc Inglesby, a retired, non-Mormon dentist and tour operator, followed by the National Park Service and Charles Kelly. By the mid-1940s the Capitol Reef Lodge was under construction, and a few years later the Giffords built their own motel (Fig. 12). The Mulfords also ran a small cafe and gas station at the south end of Fruita.

|

| Figure 12. Gifford Motel, Fruita. (NPS file photo) |

By the end of the 1950s, the inholdings were four original Mormon fruit farms owned by Cora Oyler Smith, Clarence Chesnut, Dewey Gifford, and Cass Mulford, and another five tracts owned by Max Krueger, Doc Inglesby, artists Richard and Elizabeth Sprang, the retired Dean Brimhall, and lodge-owner Archie Bird. There was also a portion of a state section along the proposed right-of-way east of Fruita, owned by Wonderland Stages (a Salt Lake City tour company); and Lurton Knee's Sleeping Rainbow Guest Ranch was operating out of Pleasant Creek. The old, insulated, idealized Mormon community of Fruita had indeed changed. In fact, local Mormon ownership was distinctly in the minority when proceedings began to buy out Capitol Reef National Monument's inholdings. [16]

As mentioned earlier, inholding acquisition was a priority under Mission 66. According to an agency monograph detailing the needs and purpose of the project:

Development of these [non-federal] lands as private homesites or for commercial enterprises detrimental to the parks, the hindrance they present to orderly park development, and the problems they present to management and protection, warrant their acquisition at the earliest practicable date. [17]

Given this priority to acquire inholdings, it is curious that Acting Regional Director Hugh Miller argued that the National Park Service should not make a "concentrated effort" to purchase the lands in Fruita. Miller believed park service purchase of the private lands would "destroy this little community," which was "in itself an 'exhibit in place,' a typical Mormon settlement which ha[d] retained much of its early day charm." [18]

Zion Superintendent Paul Franke, who had long dealt with the problems at Fruita, was more than a little upset at this recommendation. With Mission 66 money soon to be available, this seemed the perfect opportunity to resolve the issue. In his reply to Miller, Franke strongly objected to the idea that Fruita was of historical importance:

The historic features listed in your memorandum, and by the experts, are not visible to me. The worn out buildings are such that even the most pious Mormon would disown. Historic quaintness may be associated with the 'old timers.' However, their time in a permanent exhibit is but a passing moment....How can we build a typical 'Mormon Community' out of such temporary variables as human beings? These are transient values and we should not let our misguided sympathies for a few 'old timers' and their structures, even if adorned 'with star and crescent', divert our attention from the real values and significant points of Capitol Reef. [19]

Franke urged that plans not be considered based on the Capitol Reef of 15 years earlier or even of the present, but on the inevitable fact that the new, proposed paved road through the monument would bring hundreds of thousands of tourists into an area that was not prepared to handle them.

According to Franke, at absolute minimum, all the private holdings north of the Fremont River should be purchased for National Park Service development, and the lands south of the river could then be used for private concessions. Franke rejected the position of Kelly and Regional Land Chief John Kell that the Max Krueger land at the far eastern edge of Fruita was enough for preliminary development: that parcel was too flood-prone and could not accommodate all the needed facilities. Franke's motivation to purchase Fruita seems to be based on perceived National Park Service needs for development. If he could demonstrate that the inholdings were indeed dilapidated, then his argument would be that much more persuasive. [20]

The Mission 66 Prospectus for Capitol Reef National Monument, written mostly by Franke, recommended purchasing most, if not all, the private inholdings in the monument. The 1956 document, as approved by Director Wirth, stated:

There is no justification for maintaining the old settlement of Fruita because it is neither typical of pioneer settlements nor is there any value that might enhance understanding or appreciation of the area. Reduced to its proper perspective acquisition of the private lands within the monument is in accordance with Service policy and need not constitute a major undertaking. The total estimated cost of the proposed land purchases and water rights is $125,000. We hope to exchange out around 1900 acres of State owned land. [21]

The determination that Fruita lacked historical significance is key to understanding why there was no effort to retain historical integrity once the lands were purchased. Notably, however, all arguments about Fruita's significance are based on buildings and people rather than on the orchards, irrigation ditches, and land use patterns. Since most of the buildings and all the people are now gone, these orchards, ditches, and fields are, as of the mid-1990s, the crux of many land-use decisions. Yet these aspects were not even mentioned in most of the correspondence and planning documents related to Mission 66 or the purchase of the private inholdings.

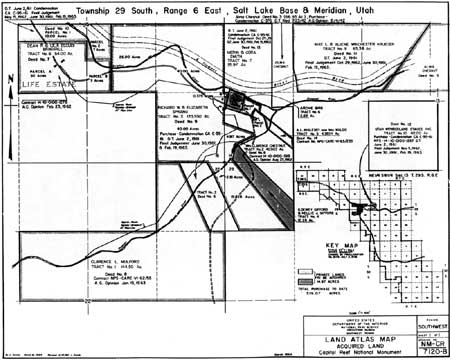

By the end of 1955 it was determined that every private inholding would be purchased in its entirety for either future developments, the road right-of-way, or both. [22] The land was to be purchased in two installments: the first would free up the proposed Fremont River corridor highway right-of-way, and the second would secure all other lands south of the proposed road. From this point on, the Fremont River road construction and purchase of most of the private inholdings would be intertwined (Fig. 13). [23]

|

| Figure 13. Fruita inholdings, 1963. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The final decision to go with the Fremont River corridor route in 1958 hastened the need for the first phase of property purchases. The Cora Smith and Max Krueger inholdings were appraised in 1958, but neither was willing to sell. [24] The difficulties with Smith and Krueger were the most cumbersome of the early land deals, portending later troubles. By the end of June 1959, the survey of the Fremont River road was complete but construction could not begin until the right-of-way purchases could be made. [25]

The tensions arising from acquisition of the inholdings were exacerbated by delays in the appraisal process. By 1960, these delays were holding up road construction. Superintendent Krueger found himself pressured from all sides. The State of Utah was ready to begin construction, and the Associated Civic Clubs of Southern Utah, the Wayne County Lions Club, and the Utah congressional delegation were insisting that the National Park Service get the money appropriated and start the road as soon as possible. It must have been frustrating for local and state tourism boosters finally to see their long-desired road within reach, only to have the project delayed again by the slow process of transferring the private landholdings into federal ownership. Added pressures from businessmen wanting a share of the expected tourist dollars from the nearly completed Glen Canyon Dam, south of Capitol Reef, didn't help the situation. [26] To put even more pressure on the National Park Service, the ceremony to open bids for the roads construction drew over 1,000 people in October 1960. [27]

The lengthy appraisal process on five separate inholdings and the continued intransigence of Cora Smith and Max Krueger forced the National Park Service to proceed with condemnation. Finally, on June 2, 1961, a Declaration of Taking was filed on five tracts of land totaling a little over 284 acres. These tracts were owned by Krueger, Smith, the Brimhalls, the Sprangs, and Utah Wonderland Stages. An additional, 37-acre tract was purchased from the Brimhalls at about the same time. Acquisition of these lands finally cleared the right-of-way for the new highway, which was begun in August only to be shut down by summer flooding until September. [28]

The bitter dispute over the Smith and Krueger properties ended up in court, where both were awarded a good deal more money than had been offered by the federal government. [29] Krueger was so upset by the whole process that he wondered "just where the difference lies between socialism, extreme bureaucracy, and communism." [30] Smith, on the other hand, never had any intention to sell and, as a matter of fact, never even gave an asking price. Today, she seems bitter that everyone else was sold out so easily. She simply "didn't want it to change." Smith recalls, "I wanted it like it was. And that's the only thing I got agin' it. I thought them people was all nuts for selling their places and they did. They sold 'em." [31]

Lurton Knee, whose Sleeping Rainbow Ranch escaped this round of private land purchases, was a witness to the buyout. According to Knee, the people of Fruita had "had enough of the hard work and the isolation, yes, but mostly the hard work." Knee added that, contrary to the opinions held by many in neighboring communities, the residents were not forced out but were more than willing to sell out. In fact, only in the Krueger and Smith cases was the amount of money an issue. As for the houses themselves, Knee recalled years later, "most of the people's homes there were just shacks and there was nothing you could do to preserve them." He added, "But the people did resent [their being torn down] because that was their home, you understand that." [32]

Because of the rapid changes that occurred in Fruita in the early 1960s, a lot of untruths have emerged. Some local residents, and even visitors from other states, believe that the National Park Service pushed these people out against their will and irreversibly altered the Fruita landscape, intending to wiping out all Mormon presence. Documents, however, argue that most landowners, who again were not of local origin, were more than willing to sell. Their land was "condemned" only because it sped the process so that roadwork could begin. Insofar as altering the landscape, it is true that most of the houses, which almost everyone agreed were in very poor condition, were torn down. That some homes were destroyed right after the residents moved out angered some in the community, but the National Park Service couldn't afford to wait.

In this author's opinion, any animosity toward Capitol Reef management as a result of the inholding purchases probably has more to do with the speed of the process than with anything else. The local residents were used to a quiet, isolated, and unchanging life in Fruita. In over 20 years of the monument's existence, nothing much had really changed. Then, in a relative blink of an eye, the residents were gone, the houses torn down, and a road was paved through the canyon. That kind of rapid change in any slow-paced, rural environment was bound to upset a few people.

Capitol Gorge Closes

Negative publicity arising from the inholding acquisitions was temporarily offset by positive relations stemming from the newly paved road and the local jobs created by that and impending projects. Bad feelings were revived, however, over the closure of Capitol Gorge to through traffic.

The new highway bisecting the monument had been so long sought by local residents and area tourism promoters that its actuality must have been hard to believe. Recall that local promotion of a national park in Wayne County back in the 1920s and 1930s was motivated primarily by the desire for this road. On the other hand, it never occurred to Capitol Reef's neighbors that once the road was paved through the Fremont corridor the old Utah Highway 24 through thrilling Capitol Gorge would be closed (Fig. 14). [33] The National Park Service, however, realized the opportunity a new road would provide. The 1956 Mission 66 Prospectus had suggested that ways should be found to encourage visitors to stay for longer periods of time. The National Park Service solution was to change the traffic circulation pattern within the monument. Once the Fremont River road was finished, the Capitol Gorge road "would be deleted except for a short section on the upper end." [34] This would avoid safety concerns arising from the seasonal flash floods through the gorge, and force visitors to turn around and drive back through Fruita to reach the through highway continuing along the river corridor.

|

| Figure 14. Old Utah Highway 24 through Capitol Gorge. (NPS file photo) |

According to the 1959 Master Plan, the road from Fruita to Capitol Gorge (with spurs into Grand Wash and to Pleasant Creek) would serve as a dead-end scenic drive. Hiking trails could lead from each spur's terminus parking lot, thereby providing easy access further into the canyons or up to scenic view points. This scenic drive network would insure that at least some visitors would not speed directly through the monument on the new highway. Rather, they would spend several hours in and out of their vehicle, enjoying the vistas and resources of Capitol Reef. The National Park Service plan fit nicely with the desires of the Utah highways department, which wanted to rid itself of the difficult-to-maintain route through Capitol Gorge as soon as the new road was completed. [35]

The State of Utah agreed to turn over the old road to the park service and to maintain and protect the new Utah Highway 24. One stipulation was that, since the state would control the right-of-way, the park service would never charge entrance fees of those traveling through the park on Utah Highway 24. [36] This agreement was apparently finalized during an official survey of the new Fremont corridor route on April 25, 1958. Recorded Krueger:

Those making the reconnaissance were officials of the Utah State Road Commission, Bureau of Public Roads, National Park Service, Wayne County Commissioners and other individuals, including State Senator Royal T. Harward, Banker Arthur Brian, Executive Secretary Tom Jensen, Associated Civic Clubs and others. [37]

While the possibility of closing Capitol Gorge for safety and development reasons was brought up at this and subsequent meetings, the general public was never told of it. Local residents and returning visitors assumed that the gorge road would be left open to local traffic and for visitor thrills as always. Thus, when the new Utah Highway 24 was finished and the old Capitol Gorge route was turned over to Superintendent Krueger on July 16, 1962, few were aware of the road's imminent closing. [38]

The actual decision was delayed for several more weeks. Four days after the road transfer, Krueger wrote to Wayne County Commission Chairman Vance Taylor asking Wayne County road crews to put flood warning signs up at the eastern entrance to Capitol Gorge, since National Park Service rangers did not regularly patrol that side of the monument. Krueger wrote:

As part of the agreement with the Utah State Road Commission the National Park Service is entitled to close the old Utah Highway 24 in Capitol Wash at the east boundary of the Monument. If it is determined that protection of the area and its administration and service to the visitor can best be accomplished by such action then the road will be closed at the east boundary. However, until the road is closed, we believe that protection of the life and property of the unsuspecting user, particularly during flood season, can best be accomplished [by placing warning signs at the eastern entrance]. [39]

Capitol Gorge, from the eastern entrance through the narrows, was closed in August 1962. While there is no documentation specifying the exact reason for the road's closure, Krueger probably was just following the National Park Service master plan for Capitol Reef. The strain additional ranger patrols through the gorge would place on Capitol Reef's minimal protection staff would have made the decision to close the road even easier. Yet, if the road was indeed meant to be closed all along, why hadn't Krueger told Taylor back in July? [40]

Since the early 1970s, fundamental management decisions within units of the National Park Service have been subject to public review under the National Environmental Protection Act. In 1962, such action was not legally required, and failure to notify the public that the traditional route through Capitol Gorge was going to be closed created a public relations disaster. Had the general public been informed, as were the elected and business leaders, that the road closure was part of the overall Mission 66 plans to develop tourism at the monument, the uproar may have been considerably less volatile. Instead, the closing seemed like another slap at the customs and traditions of a leery, southern Utah, Mormon population. This affront, coming so shortly after the rapid acquisition of the Fruita inholdings, was particularly bitter.

One initial problem was inaccurate reporting. The first rumors and reports stated that the entire Capitol Gorge was closed, instead of only a short section through the very narrowest portion of the canyon. The Salt Lake City newspapers reporting the "hot controversy in normally peaceful Wayne County" portrayed the National Park Service as a federal bureaucracy arbitrarily making policy without the consent of the governed. [41]

Interestingly, in these stories and the resulting official correspondence, the local and state officials were actually enthusiastic about the closing of the Capitol Gorge route. After all, they had been apprised of the increased visitor hours that would result from the action. The hard feelings are attributed to the failure of Superintendent Krueger and others to recognize how much the old road through the Waterpocket Fold meant to the monument's neighbors. Utah Sen. Frank E. Moss wrote to Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, "I think the biggest mistake that was made was not having it clearly known in advance what the plan of the National Park Service would be." [42]

Assistant Interior Secretary John Carver agreed. In his apology to Moss, he wrote:

According to my information, neither the park service nor the State of Utah took the precaution of advising the press that the road would be closed. It was part of a plan that goes back several years and the most charitable explanation seems to be that all concerned felt everything was in order and complacently overlooked the matter of advanced publicity. The indignant reaction shows all too plainly how wrong it was to take that attitude. [43]

Carver's response failed to acknowledge that, had the local residents been adequately notified, then the press may never have been called down from the state capitol to investigate.

The immediate furor over the Capitol Gorge road ended by October, but long-held resentments still exist. Whenever local residents are not notified and consulted about major park policy decisions, these resentments will bubble to the surface.

Mission 66 Construction

With most of the inholdings acquired and construction of the Fremont River highway completed, the National Park Service could begin implementing its Mission 66 development plans for the Fruita headquarters area. As mentioned earlier, Capitol Reef's Mission 66 Prospectus was approved in 1956. Acquisition of Inholdings was only a small part of the plans to make the National Park Service presence felt throughout the monument. [44]

According to the prospectus, Capitol Reef's combination of unique and scenic geology, high desert flora and fauna, western history, and archeology is nationally significant. In developing these themes, management was to find ways to help the casual or "adventure-seeking" tourist to enjoy the natural setting and all its offerings. The primary need was for "a means of access to the canyons by automobile" and a "means of access to the backcountry by horseback or foot." To hold the visitor for more than a couple of hours, additional developments were needed. These would include a modern campground, "shelter and food while [the tourist] stays in the vicinity," a visitor center, numerous displays, maps, and diagrams, "safeguards to [the visitor's] life and property," and "assurances of health and bodily comfort." The actual development of Capitol Reef National Monument was estimated at $2.3 million. [45]

The problem with constructing these new facilities, however, was that "the country is so rough and water so scarce, that space for development [was] extremely limited." In other words, the same conditions that had structured past attempts to live in this beautiful but mostly inhospitable land were also going to structure National Park Service plans. The choice of Fruita, which was already developed, became even more obvious when the new highway was directed through the community. Within Fruita were several possible locations for the visitor center, campground, and maintenance shops.

Once management determined where the facilities would be built, actual construction was accomplished fairly rapidly and with little difficulty. When the road was finished through Fruita, construction began on the visitor center, housing, maintenance shops, and water, sewage treatment, and transportation systems. Fruita would be a very different place in only a couple of years. [46]

By the end of 1962, the first Mission 66 houses (east of the CCC ranger station) and the water treatment plant on the Fremont River were almost completed. The roads into and around the new campground, west of Dewey Gifford's old farm, were also finished by the end of the year. As an added bonus, park operations received a boost in April 1962, when telephone service was finally extended to Fruita. There had been no telephones in Fruita since its early days, when a private, problem-plagued line ran down from Torrey and through Capitol Gorge. [47]

The years 1962-65 brought the most intensive development ever within the monument. The first two residences were finished and occupied by the families of the permanent ranger and administrative assistant in February 1963. Four more houses and the four-apartment unit that would serve as seasonal quarters were completed in 1964.

Perhaps the most significant utility improvements were the water treatment plant, operational in early 1962, and the sewage pipe and septic systems to the campground and headquarters area. No longer would water have to be hauled 22 miles from Bicknell and stored in trucks or tanks for park service and visitor needs. Now water could be drawn directly from the Fremont River, treated, and sent by underground pipe throughout Fruita. Charles Kelly would have been amazed. [48]

The visitor center, begun in 1964, would be the most used and visited structure in the park. Once the location had been settled, the building's size was debated. Superintendent Krueger received the visitor center building plans in July 1963 from the Western Office of Design and Construction in San Francisco. While satisfied with the exhibit audio-visual rooms, Krueger was troubled by the minimal amount of office space. The plans called for the new building to be linked to the old ranger/contact station by a roofed breezeway, so that the historic CCC building could provide additional office space. [49]

Krueger, troubled over the lack of space in back of the proposed visitor center, proposed removing the old building in order to expand the side or back of the new building. This idea was eventually rejected. [50]

Even though the visitor center was opened for business in June 1965, it was not actually finished for several more years. Juggling office space in the back continued to be a problem, and the planned exhibits and audio visual program were not completely installed until 1967. [51]

The utility and maintenance building, behind the visitor center, was completed in early 1964. Once the access roads in Fruita were paved and landscaping was completed around the 53-site campground and new buildings, the Mission 66 construction plans for the Fruita area were accomplished. [52]

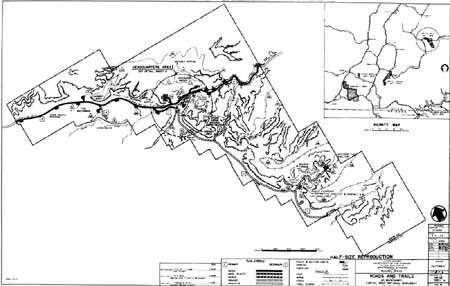

To improve visitor appreciation and knowledge, wayside parking areas and exhibits were established along the new highway through the river corridor and along the spur roads into Grand Wash and Capitol Gorge. Interpretive shelters were built at the entrance of Capitol Gorge and at the scenic drive's terminus, just west of the narrows. These shelters were intended to be manned by seasonal naturalists, who would meet visitors and interpret the natural, historical, and archeological resources. A ranger could also monitor resource protection and potential flood threats. [53] To enable the visitor to better appreciate Capitol Reef's scenery and resources, improved trails were built to the base of the Golden Throne (the most dominant of the Navajo Sandstone domes above Capitol Gorge), and up to Cassidy Arch. New trail spurs were also created to scenic viewpoints off of the Hickman Natural Bridge and Cohab Canyon trails (Fig. 15). [54]

|

| Figure 15. Proposed Mission 66 roads and trails development. |

Organization And Personnel

These Mission 66 developments would be meaningless without adequate personnel to staff the facilities and protect the monument's resources from the anticipated influx of visitors. When Superintendent Franke's prospectus was approved in 1956, personnel projections called for a gradual increase from one permanent position and two seasonals to seven permanent and seven seasonal positions 10 years later. Of those positions, 10 were to be in management and protection and four in maintenance and rehabilitation, each equally divided between permanent and seasonal.

According to the prospectus, by 1966 there were to be (in addition to the superintendent) one permanent administrative assistant, a park naturalist, and two park rangers in the management and protection branch; a roads and trails foreman; and a buildings and utilities maintenance position. Except for the unanticipated need for additional permanent maintenance positions, these plans accurately reflected the monument's staffing needs. The proposed timeframe, however, was far too optimistic. [55]

The ensuing personnel shortages were exacerbated by the "de-coordination" of Capitol Reef National Monument. After February 1, 1960, the monument was no longer under Zion National Park's coordinating supervision. Superintendent Krueger was promoted from a GS-9 to a GS-11 and given full responsibility for his monument, making Capitol Reef a full partner in the national park system. While the monument's new independence would give it greater status within the system, the increased responsibilities and paperwork were daunting. [56]

An administrative assistant would have helped tremendously, had the position been activated in 1960 as planned. Meanwhile, the rangers and superintendent had to cover the clerical responsibilities for another two years until Paul C. Bennion was hired to take them on.

The ranger division was also slow in materializing. Grant Clark had come on as the first permanent in 1958, but it was 1964 before the superintendent could hire Franklin Montford as chief ranger. Thus, the two permanent ranger positions met Mission 66 goals four years behind schedule. The park naturalist position, originally to be filled in 1962, was not funded until three years later. [57]

In the maintenance division, by 1963 there were three permanent employees: Bernard Tracy, who monitored the water treatment plant and was lead maintenance man; caretaker Dewey Gifford; laborer Clarence Chesnut; and a couple of seasonal laborers. It was their combined responsibility to care for the new facilities, manage the irrigation system, maintain fencing, and monitor "the numerous buildings and other structures which [were] dilapidated and scheduled for removal" from the recently purchased inholdings. [58]

These personnel shortages, which are typical for the National Park Service and other federal agencies, limited the immediate success of Mission 66 at Capitol Reef. Most of the new personnel were also new to the National Park Service, requiring additional time for orientation and training. A real benefit to the monument, though, was that most of the new employees were from the local communities. This helped polish tarnished public relations and create a better relationship between the monument and its neighbors. [59]

Impact Of Mission 66

Capitol Reef National Monument changed significantly as a result of the Mission 66 programs. A new, paved highway brought over 100,000 visitors for the first time in 1960 and over 200,000 only two years later. This contrasted sharply with the 62,000 who passed through the monument in 1956. It was projected that 750,000 people would see Capitol Reef by 1970. While this figure proved optimistic, waves of people were indeed descending on a monument accustomed to receiving a mere trickle. [60]

Although most of the facilities were not finished until after the first busy visitor seasons, since their completion they have benefited visitors and employees alike. The visitor center, housing, campground, maintenance buildings, water and sewage systems, and most of the roads and trails built during Mission 66 continue to be the primary facilities at Capitol Reef today.

Critics of the National Park Service's Mission 66 programs point to the establishment of roads and facilities in parks that should have been (they feel) left undeveloped. This was not the case with Capitol Reef. The monument's infrastructure had to be brought up to date to provide for the education and enjoyment of increasing numbers of visitors. As a result, visitors would have a better understanding of monument resources, and would stay somewhat longer to enjoy their surroundings. The rugged backcountry of multi-colored sandstone canyons, cliffs, and domes, however, would remain virtually untouched.

The greatest change occurred in Fruita. The private inholdings, with their history and buildings, were all but gone. Remaining were the orchards and a few scattered buildings and structures that visitors saw as quaint, and which neighbors and relatives considered elements of their cultural identity. Since today's emphasis is on historical preservation, it is hard for some to understand why the old buildings of Fruita were removed. At that time, Fruita provided the best location within the monument for adequate road and facility development. Many of the existing buildings were viewed as dilapidated and unsafe eyesores; others were simply considered inappropriate or in the way. Thus, the park service could choose between long-range planning and development at Fruita, or the restricted, minimal National Park Service presence of the past.

In summation, although Mission 66 improvements benefited Capitol Reef, some of them were implemented in an impolitic manner that damaged park service credibility among local communities. The acquisition of the private inholdings was inevitable, but the process was made unduly awkward by administrative delays. Cora Smith and Max Krueger probably never would have sold of their own accord. The hurried condemnation proceedings, however, left the impression of an aggressive federal bureaucracy kicking out its own residents.

While the inholding problems were largely circumstantial, the lack of foresight over the Capitol Gorge road closure was more troubling. In that instance, the superintendent, (and to some extent, local and state officials) neglected to notify the public that its traditional and beloved route through the monument was to be closed. This may have been an oversight. The lasting perception, though, was that the National Park Service considered the monument some kind of separate microcosm that did not have to interact with its neighboring communities. Like natural ecosystems, cultural systems are not confined by political boundaries; management overlooks that fact at its own risk.

The people of southern Utah love their land and the traditional manner in which they have used it. While unpopular management decisions were made by the park service, it was not so much the decisions that caused bad feelings as it was the seemingly imperious manner in which they were made. The resulting resentments added to cultural and administrative barriers at Capitol Reef just when some of the physical barriers were finally being overcome. The misgivings of local residents toward Capitol Reef would emerge once again with the emotional debate over monument expansion in 1969.

Footnotes

1 Barry Mackintosh, The National Parks: Shaping the System (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1991) 62; John Ise, Our National Park Policy: A Critical History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1961) 546.

2 Conrad Wirth, quoted in Ise, 547.

3 Mackintosh, 62; Ise, 346-347; "Mission 66," (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, January 1956), Box 500, Folder 10, Wilderness Society Papers, Western History Collection, Denver Public Library.

4 Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire (New York: Ballantine Books, 1971) provides a good example of the opposition to Mission 66.

5 Franke to National Park Service Director, 11 April 1955, File A9815, Accession #79-67A-337, Box 1, Container #919498, Records of the National Park Service (RG 79), National Archives - Rocky Mountain Region, Denver (hereafter referred to as NA-Denver).

6 Ibid., 1-2. The common belief that the rugged-looking desert landscape is also durable has now been dispelled. Resource management plans for Colorado Plateau parks over the past decade have stressed the extremely fragile nature of desert ecosystems. Fortunately for Capitol Reef's resources, the Waterpocket Fold barriers would continue to restrict public access to all but the most well-established routes.

8 Superintendent's Monthly Narrative Reports (hereafter referred to as Monthly Reports), September 1956 and June 1957, Box 4, Folder 3, Capitol Reef National Park Archives.

9 Monthly Reports, October and December, 1956.

10 Ibid., April, 1956; Regional Director site visit report, 30 July 1956, File D30, 79-67A-337, Box 1, RG 79, NA-Denver.

11 Regional Director to National Park Service Director, 21 December 1956, Ibid.

12 Charles Kelly diary, 1 December 1956, Charles Kelly Manuscript Collection, MSS 100, Box 1, Folder 1, University of Utah Special Collections, Manuscript Division, Marriott Library, Salt Lake City (hereafter referred to as Kelly diary).

13 National Park Service Press Release, 11 March 1959, File K3415, #79-65A-580, Box 1, Container #SB202684, RG 79, NA-Denver.

14 Harold P. Danz, Historical Listing of National Park Service Officials, revised ed. (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, May 1991) 114.

15 See Chapter 8 for more information.

16 "Land Atlas Map, Acquired Lands," 16 March 1964, Drawer 5, Folder 2, Capitol Reef National Park Archives.

17 "Mission 66 for the National Park System," 111.

18 Acting Regional Director to Zion Superintendent, 6 May 1955, File L1415, 79-67A-337, Box 1, RG 79, NA-Denver.

19 Zion Superintendent to Regional Director, 10 June 1955, Ibid.

21 "Mission 66 Prospectus, Capitol Reef National Monument, Utah," 17 April 1956, Ibid.

22 "Proposed Land Acquisition Program, Capitol Reef National Monument," 1 November 1955, File L1415, 79-67A-337, Box 1, RG, NA-Denver.

23 Zion Superintendent to Regional Director, 15 October 1958, Ibid. For a comprehensive examination of each inholding, see Cathy Gilbert and Kathleen McKoy, "Cultural Landscape Report: Fruita Rural Historic District," prepared for National Park Service, on file, Intermountain Regional Office, Denver, 1993).

26 Zion Superintendent to Regional Director, 28 January 1958, and 12 letters petitioning for road construction, 1958, File D30, 79-67A-337, Box 1, RG 79, NA-Denver.

27 Monthly Report, October 1960.

28 Monthly Reports, June-September 1961. While acquisition of all but one small, private inholding dragged on until the 1970s, the tracts needed for the road and future development of National Park Service housing, campground, picnic areas, and a water treatment plant were purchased by 1964. See Volume II, Chapter 14.

29 The final offer to Smith was $13,000 for her 35 acres. The court awarded her over $27,000. Krueger was offered $30,000 for his 64.40 acres, and the court awarded him over $44,000 ("Congressional Committee Report, Lands Acquired by Condemnation, FY 1959 through FY 1963," File L1415, 79-67A-505, Box 1, RG 79, NA-Denver).

30 Max Krueger to William Krueger, 14 September 1961, Ibid.

31 Cora Oyler Smith, interview with Kathy McKoy, 8 May 1993, tape and transcript, Capitol Reef National Park Unprocessed Archives, 40.

32 Lurton Knee, interview with Brad Frye, tape recording, 18 September 1992, Capitol Reef National Park Archives; David White, "By Their Fruits Ye Shall Know Them: An Ethnographic Evaluation of Orchard Resources," February 1994, 51-52, prepared under contract for the National Park Service, on file, Capitol Reef National Park Division of Resource Management.

34 "Mission 66 Prospectus," 12.

35 William Krueger to Vance Taylor, Chairman, Wayne County Commissioners, 20 July, 1962, File D30a, 79-67A-337, Box 1, Container #919498, RG 79, NA-Denver.

36 Director Wirth to Regional Director, 25 January 1957, Ibid.

37 William Krueger to Vance Taylor, Chairman, Wayne County Board of Commissioners, 20 July, 1962, File D30a, 79-67A-337, Box 1, Container #919489, RG 79, NA-Denver.

38 Deseret News, 24 August 1962; Monthly Report, July-August 1962.

40 Monthly Reports, July-August 1962.

41 Deseret News, 24 August 1962. Also see Salt Lake Tribune, 3 September 1962.

42 Moss to Udall, 19 September 1962, File D30, 79-67A-337, Box 1, RG 79, NA-Denver.

43 Carver to Moss, 6 November 1962, Ibid.

44 "Mission 66 Prospectus, Capitol Reef National Park," 17 April 1956.

46 Monthly Reports, May-July 1962.

47 Monthly Reports, March-December 1962.

48 Monthly Reports, 1963-64. There were also improvements to the irrigation system obtained through purchase of the inholdings. See Gilbert and McKoy's "Cultural Landscape Report" for specifics of when and how the irrigation system was renovated.

49 Krueger to Regional Director, 8 July 1963, File D3415, 79-67A-505, Box 1, Container #342490, RG 79, NA-Denver. The Western Office of Design and Construction developed most of the Mission 66 plans for Capitol Reef.

51 Robert Heyder, interview with Brad Frye, tape recording and transcript, 1 November 1993.

52 Krueger to Regional Director, 18 July 1961, File D22a, 79-67A-505, Box 1, Container #342490, RG 79, NA-Denver.

54 Krueger to Regional Director, 6 December 1960, File D3415, 79-67A-505, Box 1, RG 79, NA-Denver.

55 "Mission 66 Prospectus," 21-22.

56 Monthly Reports, January - February 1960.

57 "Mission 66 Prospectus," 21-22; Monthly Reports, 1958-65.

58 Krueger to Regional Director, 4 September 1963, File D3515, 79-67A-505, Box 1, RG 79, NA-Denver; Monthly Reports, 1960-63.

59 "Annual Report on Manpower Utilization," 22 September 1963, File A6423, 79-67A, 337, Box 1, Container #919498, RG 79, NA-Denver.

60 Press release, undated, File K3417, 79-67A-505, Box 1, RG 79, NA-Denver.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

care/adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 10-Dec-2002