|

CHACO CULTURE

Master Plan Chaco Canyon National Monument, New Mexico |

|

THE RESOURCE

RESOURCE DESCRIPTION AND EVALUATION

Archeology

Chaco Canyon National Monument is important primarily because it contains outstanding archeological remains of the Anasazi (Basketmaker-Pueblo) culture. Within the monument there are over 400 recorded archeological sites ranging from simple one-room pithouse dwellings to complex pueblos containing several hundred rooms. In addition to the thousands of living quarters and storage rooms, these archeological sites include ceremonial structures known as kivas and great kivas, pictograph sites, prehistoric stairways carved in the cliffs, and several archeologically important trash mounds. They also include complex water conservation and distribution systems which have only recently come to light. From these sites has come a wealth of stone, bone, clay, and fiber artifacts which, in combination with the physical remains, have been helpful to the archeologist in deciphering the story of man's existence here.

|

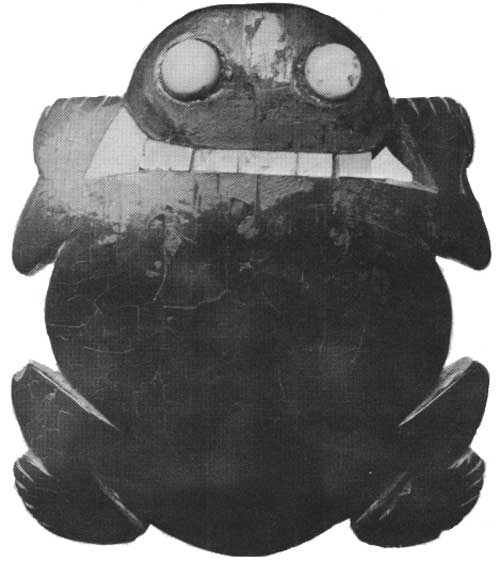

| Carved jet frog. (Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History) |

|

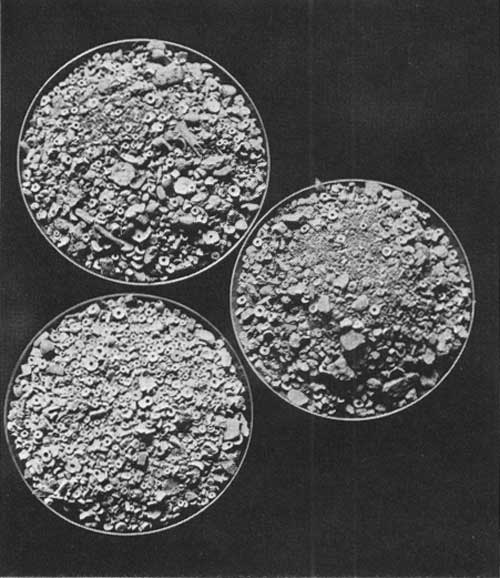

| Thousands of beads and pendants were found during the excavations. (Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History) |

Occupancy of this area dates from about A.D. 600 to about A.D. 1275, during which time the cultural traits changed quite radically from a simple farming culture to one with a high degree of sophistication. The greatest distinction of these prehistoric people lies in the massiveness of the multi-storied buildings they constructed, the excellence of their stone masonry, the high peak of proficiency shown in their arts and crafts, and the engineering knowledge evidenced by their highly developed water collecting and distribution systems.

Perhaps the most distinctive, yet least known aspect is the highly complex social and religious organization of the community which would have been necessary in achieving all they accomplished.

The economy was principally based on floodwater farming—at first corn and squash and later beans. These farm products were supplemented by the gathering of wild plants and seeds and by wild game which was snared or hunted. They did some weaving and made elaborate baskets, jewelry, and pottery. These items formed the basis for a lively trade with peoples in far distant places as indicated by the remains of numerous parrots, macaws, and copper bells.

|

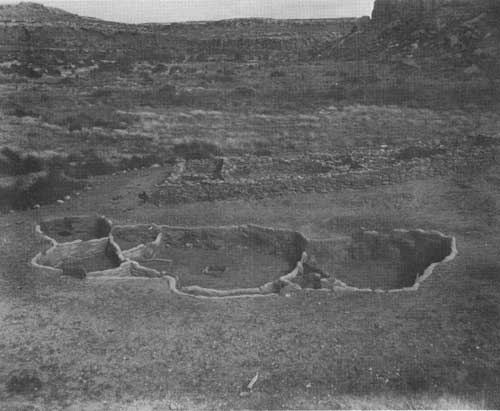

| Early pithouse contrasts sharply with an adjacent but later period Pueblo. |

During the earlier Basketmaker periods, these people lived in small circular structures called pithouses (because the floors were 1 to 3 feet below the surrounding ground level). The walls and flat roof were made of poles, chinked with bark and brush, and the whole covered with a thick layer of mud. Later these individual pithouses were replaced by multi-family dwellings built entirely above ground and with walls made of stone laid in adobe mortar. The small rectangular, flat-roofed rooms were at first built in rows or clusters. Later, additional rooms were built beside or on top of the earlier rooms and the development of the great multi-storied, multi-roomed pueblos began.

|

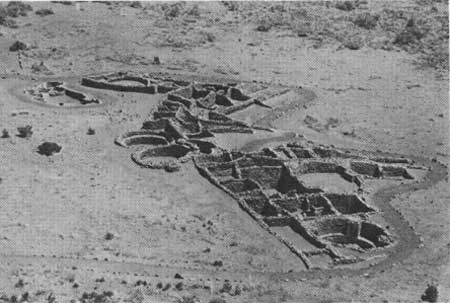

| Pueblo Bonito—one of the most outstanding Indian ruins in the Southwest. |

The largest of these villages was Pueblo Bonito which had approximately 800 rooms, including more than 30 kivas and 2 great kivas. This village covered more than 3 acres, in places was 4 or 5 stories high, and may have housed as many as 1,200 people. Other major prehistoric developments include:

|

Chettro Kettle Kin Nahasbas Una Vida Pueblo Alto (2) Casa Chiquita Tsin Kletzin Pueblo Pintado Kin Biniola |

Casa Rinconada Wijiji Hungo Pavie Kin Kletso Pueblo del Arroyo Penasco Blanco Kin Ya-ah Kin Klizhin |

|

| One of several impressive prehistoric stairways to the canyon rims. The size of the steps—often 8- to 10-feet wide—suggest ceremonial use. |

In studying the later periods of development at Chaco Canyon, archeologists have identified three main cultural phases, two of which (the Bonito and Hosta Butte) were the end products of long developing traditions in the Chaco area, and the third phase (McElmo) involved migrants who came into the area later.

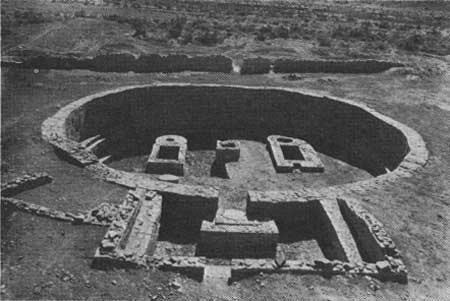

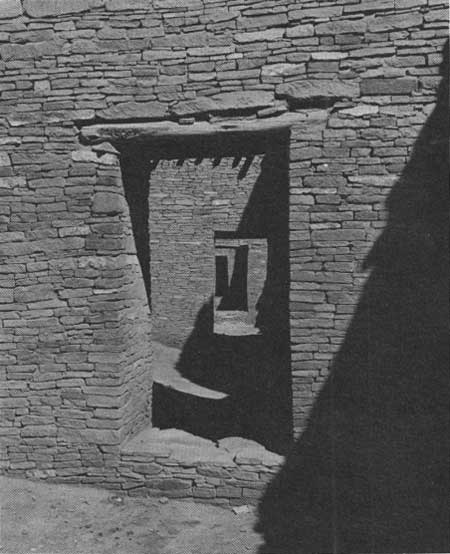

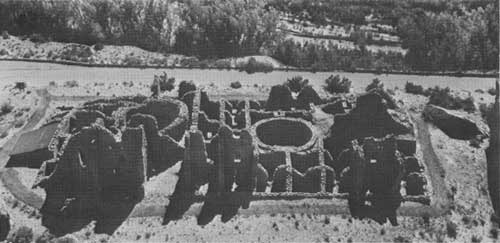

The Bonito Phase is represented by the large classic villages concentrated mainly on the north side of the canyon (Pueblo Bonito, Chettro Kettle, Pueblo del Arroyo, Hungo Pavie, Una Vida, and Wijiji); by the isolated great kivas (Casa Rinconada and Kin Nahasbas); and by certain of the outlying villages (Penasco Blanco, Pueblo Pintado, Old Alto, Kin Biniola, Kin Klizhin, and Kin Ya-ah). Architecture is characterized by preconceived plan, multi-storied structures, "D," "E," or oval-shaped ground plan with open plaza or courtyard area enclosed by rooms. Masonry is heavy, cored and with decorative veneers. Kivas and great kivas were common. The wide rock stairways of possible ceremonial significance and the extensive water conservation and distribution systems are closely associated with this phase. Artifacts from these sites contain a greater number and variety of luxury items such as turquoise mosaics and necklaces, jet or gilsonite inlays, tall cylindrical vases, painted sandstone, parrots, macaws, and copper bells.

The Hosta Butte Phase villages are generally small and scattered along the south side of the canyon. They are characterized by random, irregular clusters of rooms, generally limited to one or two stories. The house blocks enclose kivas of a different type than in the Bonito Phase. There are no open courtyards or plazas and no great kivas. Masonry is thin and fragile, not cored and without decorative veneers. The luxury-type artifacts seen in the Bonito Phase are absent.

|

| Chettro Kettle—a major Bonito Phase ruin located a short distance east of Pueblo Bonito. View looking southeast down the Chaco Canyon. |

|

| The Great Kiva in the plaza of Chettro Kettle. |

|

| Typical ruin of the Hosta located on the south side of the canyon opposite Pueblo Bonito. Excavated early pithouse site to the left of the main ruin. |

|

| Masonry detail at Pueblo Bonito, showing doorways and the excellent masonry construction representative of the Bonito Phase. |

|

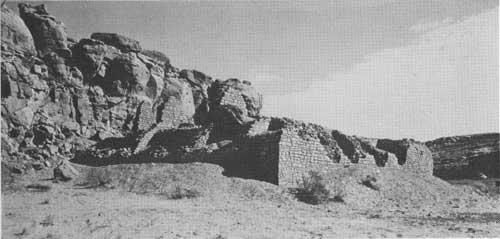

| Kin Kletso—a small, interesting McElmo Phase ruin a short distance west of Pueblo Bonito. |

|

| Casa Chiquita—a compact village downstream from the main ruins area. Compare the rock work on the walls of this McElmo Phase village with that of Pueblo Bonito, a Bonito Phase village. |

|

| This Great Kiva reflects the massive stonework and classic architecture of the Bonito Phase. |

The McElmo Phase architecture is characterized by compact, multistoried, planned villages with kivas enclosed in house blocks but no great kivas. Sites representative of this phase are Kin Kletso, Casa Chiquita, New Alto, and Tsin Kletzin. Masonry is cored, thin-walled, and often faced with large blocks of sandstone, pecked and "dimpled," with chinking between stones. Artifacts were generally poor in both quantity and diversity except for the large-scale manufacture of the distinctive McElmo black-on-white pottery.

In summary, the Bonito Phase is represented by the large multiroomed villages concentrated along the north side of the canyon.

The Hosta Butte Phase, which was present at Chaco from nearly the same time as the Bonito Phase, was largely concentrated along the south side of the canyon as small suburban units.

The McElmo Phase sites are viewed as latecomers into the area. The people of this phase were migrants from the San Juan area who came into Chaco during the period 1030-1050, bearing their distinctive architecture and carbon-painted pottery. Their arrival caused no break in activities among the large cities of the Bonito Phase or in the suburbs of the Hosta Butte Phase where these original settlers continued making iron painted pottery and pursued without disruption their own socio-ceremonial, agrarian way of life. All three groups of people henceforth lived cooperatively side by side. The inference is strong that although the urban centers of the Bonito Phase were the directing force in the fields of architecture, town planning, and irrigation systems, the populations of all three phases participated in and benefited from the construction of the wide stone stairways and the extensive irrigation developments.

Between 1150-1200 both natural and man-caused forces acted with equal vigor on the Chaco population, causing them to abandon the area. The urban centers of the Bonito Phase, the suburban Hosta Butte villages, and the intrusive McElmo Phase towns were all abandoned about the same time.

|

|

|

Although additional research on the reasons for abandonment is needed, past studies seem to indicate that there probably was no single cause but a series of complex and interrelated causes. The Chaco was an area of marginal pine forest interspersed with stand of pinyon and juniper; it was on the edge of the gradual, upward recession of southwestern pine forests that has been in progress from fairly remote times. Coupled with this natural, gradual recession, the forest border was further reduced by the profligate cutting of young trees for construction, most active over a hundred-year period beginning in the early 11th century. Intensive farming, numerous ditches, and the extension of small house sites, with their usual barren environs, out in the canyon floor, eliminated much of the perennial cover there, leaving it particularly susceptible to erosion. Local tree-ring records are not available for the Chaco in post-A.D. 1124 times. Hence it is entirely possible that a localized drought occurred of such intensity as to cause crop failures, to have triggered arroyo cutting, and to have reduced the population. In short, a receding forest, coupled with forest denudation, soil erosion, arroyo cutting, and a probably change in rainfall are viewed as the initial causes for abandonment. With the resulting crop failures would have come famine, lowered resistance to disease and a general reduction in the population. Lacking a sound understanding of the relationship of these causes and effects, this series of apparently unrelated calamities would have raised serious questions as to the effectiveness of the social and ceremonial structure which was supposed to prevent them.

The resulting internal pressures, doubts, and conflicts undoubtedly resulted in at least a partial breakdown in the previously well-organized social structure. Neighboring nomadic tribes may well have taken advantage of these disruptions in carrying out their ceaseless attempts to rob and harass the Chaco villages.

Whatever the cause or causes, the Chaco people gradually left the area and, by about 1200, the numerous villages and farms were abandoned.

At least a large part of the population who abandoned the Chaco followed the retreating forest border and the retreating arable land upstream beyond the headwaters of the presently entrenched arroyo, reestablishing themselves 25 to 35 miles east of Pueblo Bonito. Some of this group may have shortly thereafter continued on to the Rio Grande drainage to the east as forerunners of the general movement from the San Juan to the Rio Grande. Other groups lingered in the extensive area between the Chacra Mesa and the Rio Puerco where they were met by survivors from the San Juan from which some pushed on to the Rio Grande.

Between 1200-1350, small groups of Mesa Verde migrants drifted in and out of Chaco, either reoccupying some classic Chaco sites or constructing small, new units.

During the period 1350-1745, Pueblo peoples fleeing the Spaniards after the Rebellion of 1680 commingled with the Navajos, built fortified sites, lived in Navajo occupied country for awhile, and eventually returned to their original homes.

During the period 1772 to 1889 the Chaco region was populated by scattered Navajo families. Actually, this occupation extends to the present day and represents the last Indian occupation of the region.

|

| Flutes with carved figures (such as these tadpoles) were found in Pueblo Bonito. They were probably used in ceremonies. (Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History) |

History

The name Chaco, of unknown derivation, was first referred to by the Spaniards in 1768, when "Mesa de Chaca" (Chacra) appears in a document concerned with the western boundary of a tract of land. The name Chaco also appears on maps of the late 1700's, and reference to the ruins first occurs in Josiah Gregg's book, Commerce of the Prairies, published in 1844, although he did not visit the area. In 1849, Lt. James H. Simpson and the artist Richard H. Kern took notes and made sketches of some of the ruins, while accompanying Lt. Colonel John M. Washington's expedition through the Navajo country.

Aside from occasional scouting trips passing through Chaco Canyon in conjunction with military operations against Navajos to the west, no significant visits were made until W. H. Jackson in 1877 led a Hayden Survey Party into the ruins area of the canyon. Jackson's photographic record was lost, due to experimentation with a new process, but his report was published in 1878. Victor Mindeleff photographed the ruins in 1887-88 for the Bureau of American Ethnology. In the latter year, Charles F. Lummis, the prolific writer on southwestern scenes and Indians, visited the area.

In 1896, Richard Wetherill, who earlier had discovered a great many outstanding prehistoric ruins in the southwest, including the great cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde, moved to Chaco Canyon. In the same year he interested Talbot B. Hyde and his brother Frederick E. Hyde, Jr., of New York in undertaking excavations in the ruins.

The Hyde expedition of 1897-1900 was the first to conduct scientific excavations in Chaco Canyon. These were under the direction of F. W. Putnam of the American Museum of Natural History, with George H. Pepper as the Field Director. Included was a geological survey of the canyon under Richard E. Dodge of Columbia University. The final results of these investigations in 198 rooms were published by Pepper in 1920 in the Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History (Volume 27). Several articles of specific interest were published earlier in other scientific outlets.

|

| A Hyde Expedition photograph of Kin Biniola in 1899. F.W. Putnam of the American Museum of Natural History on horseback in center of picture. (Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History) |

|

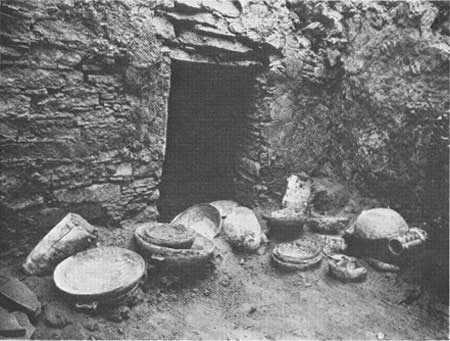

| A Hyde Expedition photograph made in 1896 of an archeological excavation in progress; Room 62, Pueblo Bonito. Baskets, pottery and other objects have been uncovered but are still in place. (Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History) |

|

| Pottery collection from Room 28 in Pueblo Bonito. Hyde Expedition, 1896. (Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History) |

|

| Human head in clay. Suggestions of hair styles, decoration and personal adornment are often found on these fragments. (Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History) |

In early 1900, Wetherill applied for a homestead which encompassed three of the major ruins—Pueblo Bonito, Chettro Kettle, and Pueblo del Arroyo. In his affidavit of 1901, Wetherill indicated that he would cooperate with the Government and relinquish title to the ruins when requested to do so.

In 1902, Dr. E. L. Hewett, who later became the prime mover for the "Antiquities Act of 1906," mapped the ruins of Chaco Canyon. Passage of the Antiquities Act to preserve the country's prehistoric ruins from vandalism or unauthorized search was enacted on June 8, 1906. In January 1907, Wetherill relinquished any claim that he had previously held on the 36.75 acres containing the three ruins and on March 11, 1907, Chaco Canyon National Monument was established.

Three years later, Richard Wetherill, who was operating a trading post in the canyon established during the days of the Hyde expedition, was murdered. His grave is located in a small cemetery a short distance down the canyon from Pueblo Bonito.

In 1916, N.C. Nelson and Earl Morris trenched refuse mounds at Pueblo Bonito, and Hewett, then with the School of American Research, conducted a reconnaissance of the ruins. In 1920-21, the School initiated its first project in the monument but discontinued further work while the National Geographic Society project of 1920-27 was in operation.

The Society's excavation was under the direction of Neil M. Judd, Curator of Archeology at the U.S. National Museum and included tree ring studies in 1928-29 directed by Dr. Andrew E. Douglass of the University of Arizona. The results of these intensive studies of the large pueblos, including Frank H. H. Robert's report, Shabik'eshchee—An Early Site, have since appeared in a number of journals and monographs, the most recent in 1964.

In 1929 the School of American Research renewed work under Hewett's direction in cooperation with the University of New Mexico and conducted a number of excavations yearly through 1937. Since that date the National Park Service has made periodic research studies, salvaged ruins threatened by erosion, and maintained a continuing stabilization program to preserve standing ruins.

There are few historic remains at Chaco. Richard Wetherill's trading post, built against the back wall of Pueblo Bonito in 1897, has long since been razed, as have the numerous buildings and hogans built by the University of New Mexico to house its field school in archeology between 1936 and 1947. The ruin of a coal mine, developed and used by Richard Wetherill and others, is located in the South Gap section of the monument. The only other evidence of occupancy, other than Indian, is the remains of a small masonry building located under the cliff north of Penasco Blanco, which was built by a cattle company prior to 1896.

Natural History

Geology—The walls of Chaco Canyon are part of a geological formation known as the Mesaverde Group. Two strata of this group are visible in the canyon walls. The upper rust-colored strata, characterized by the presence of marine fossils, is called Cliffhouse sandstone. Below this lies the Menefee formation—1,800 feet thick and composed of strata of coal, shale, and buff-colored sandstone, in which fossil plants predominate. The Mesaverde Group, of the Upper Cretaceous period, is overlain in the northern sections of the monument by Lewis shale and Picture Cliffs sandstone.

These sedimentary formations were laid down in ancient seas and lakes. Subsequent earth movements elevated the area to form the southern reaches of the San Juan Basin, a part of the Colorado Plateau. Erosional forces have continuously eaten away at the great beds of sandstone following the uplifting of the area.

Vegetation—The flora of the Chaco Canyon area is of neither great abundance nor wide diversification.

Mesa tops are sparsely spotted with juniper and pinyon pine. Numerous species of shrubs, annuals, and grasses are also found on the mesa tops; some of the predominate are saltbush, the snakeweeds (Gutier reziasarothrae and microcephala), prickly pear cactus, gramma, Indian wheat, and rice grass.

Greasewood and saltbush predominate on the canyon floor and rabbitbrush is common in many sections. The exotic tumbleweed is very common. Shrubs, including mountain privet, sumac, and wild cherry, are found mainly in the sheltered breaks.

This general region was seriously overgrazed in the past and, as a result, the vegetative cover was greatly altered and the land was badly eroded. Because the monument was fenced and grazing was eliminated in 1946, the vegetative cover is now gradually returning. Extensive soil and moisture conservation work has been done in the area in an effort to stabilize the land and prevent further erosion and danger to priceless ruins. In addition to constructing check dams, diversions, and dikes, considerable areas have been seeded to native grasses. In attempting to control streambank erosion, jetties have been installed and several species of cottonwood and willow were planted. In the early days the exotic salt cedar was utilized in this work and it continues to thrive.

|

| Chaco Wash—south across Chaco Canyon towards Fajada Butte, showing eroded channel of the Chaco River. Junction with Gallo Wash in foreground and with Fajada Wash in distance. Many of the trees in the wash were planted to prevent further erosion and channel changes. |

Wildlife—Wapiti and pronghorn are known to have been hunted by the prehistoric inhabitants of Chaco Canyon, and these animals are reported to have been seen in the monument on rare occasions within the past 30 years. The monument, however, does not constitute a complete habitat for the larger animals and space is too limited for reintroduction.

Observations of mule deer are common within the monument at all seasons. Bobcats are also commonly observed. Desert fox are common but are not often seen by visitors since they are nocturnal in habit. The population of coyotes is reduced periodically by predator-poisoning projects conducted by other agencies beyond the exterior boundaries.

The most important rodents to the visitor are the antelope ground squirrel, prairie dog, and the cottontail rabbit.

The most important of the resident birds are the scaled or blue quail, the brown towhee, loggerhead shrike, great horned owl, and rock wren. Turkey vultures, red-tailed hawks, common raven, cliff swallows, and numerous other migrants are commonly observed by visitors.

Visitors find the several species of small lizards which inhabit the ruins interesting to watch. Gopher snakes and bull snakes are common. The one poisonous snake, a prairie rattler, is common, but seldom seen by visitors.

FACTORS AFFECTING RESOURCE AND USE

Legal Factors

Establishment—Chaco Canyon National Monument was established by Presidential Proclamation No. 740. March 11, 1907 under authority of the Antiquities Act of June 8, 1906. The area thus established consisted of the monument itself (31 sections of land) and four detached areas; Kim-me-ni-oli (now Kin Biniola), Kin-Yai (now Kin Ya-ah), and Casa Moreno (now Casa Morena), each containing 160 acres, and Pueblo Pintado with 320 acres.

A resurvey of the lands in this area revealed that some of the lands described in the proclamation did not, in fact, contain the described ruin and a second proclamation was required to correct this situation.

The second proclamation—No. 1826 of January 10, 1928—added one section of land to the monument itself (a section containing the Tsin Kletzin Ruin) and added 40 acres of land to the Kin Biniola detached area so as to include the Kin Biniola Ruin itself. It also added a new 40-acre detached tract containing the Kin-Kla-Tzin Ruin (now Kin Klizhin). On the map which accompanied the original proclamation, this ruin was shown one mile to the east and in the main monument section. A 160-acre area containing the Pueblo Pintado Ruin was also established by this proclamation. This unit is 1-1/2 miles west of the 320-acre tract erroneously established by the previous proclamation to protect this ruin.

The second proclamation corrected previous errors by adding lands on which the ruins were actually located, but did not delete any of the previously authorized lands.

The Seventy-first Congress, in an Act dated February 17, 1931 (46 Stat. 1165), authorized the exchange of private lands within the monument for Federal lands elsewhere in New Mexico; authorized stock driveway use across monument lands to owners of certain lands in and adjoining the monument; and specified certain means by which the University of New Mexico, the Museum of New Mexico, and/or The School of American Research could continue scientific research on their former lands, or—at the discretion of the Secretary of the Interior—on other lands within the monument.

Legal Provisions

Oil, gas, and mineral rights on Sections 3 and 11, T.21N., R.11W. (except for that portion of Section 11 which was originally included in the Ackerly Tract) are still outstanding, as the owners retained these rights when they sold the land to the University of New Mexico.

Under provisions of the Act of February 17, 1931, a memorandum of agreement between the U.S. Department of the Interior and the Regents of the University of New Mexico was prepared to reserve their rights to continue scientific research, This memorandum of agreement, which was signed by the Secretary of the Interior on June 3, 1949, grants the Regents perpetual preferential rights to conduct research on lands within the monument formerly owned by the University.

This same Act provides that "any owner of patented lands in the monument now owning other lands adjoining said monument, which may be separated by the acquisition of land in the monument . . . shall be . . . authorized to drive stock across said monument at an accessible location . . . which right shall also accrue to any successor in interest to said adjoining lands or to any lessee of such lands." As a result of the checkerboard pattern of railroad land grants which existed in this area, the above provisions, in effect, give perpetual rights to drive stock across the monument to owners or lessees of most of the adjoining lands. Although in recent years nearly all the stock is trucked rather than driven, the right to drive stock across the monument still exists.

Land Status

The acreage of land within the existing boundaries is as follows:

| Federal | 21,149.35 | |

| Non-Federal: | ||

| Kin Klizhin Ruin | 40.00 | |

| Penasco Blanco Ruin | 160.05 | |

| Casa Morena Ruin | 160.00 | |

| 360.05 | 360.05 | |

| TOTAL | 21,509.40 | |

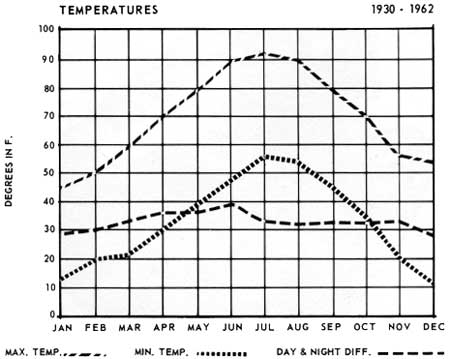

Climate

The climate at Chaco Canyon is generally mild, dry, and sunny. Temperatures range from a high of 108° to a low of minus 38°. Precipitation averages 8.42 inches per year. Approximately 18 to 19 inches of snow accounts for less than 1 inch of the total precipitation. Snowstorms usually deposit about 4 inches of snow, which normally evaporates within 2 or 3 days except on north-facing slopes. Most of the precipitation comes from thundershowers which occur somewhere in the immediate vicinity almost daily in July and August.

Windstorms of several days' duration, with speeds up to 40 or 50 miles per hour, can be expected in the spring. Generally winds are from the west and carry varying amounts of dust and sand.

First frosts come about September 1 and the last frost of the season occurs about April 30. The ground may be frozen to a depth of 3 feet during January, February, and March. Rainstorms and flash floods which cause gully-cutting and make access roads temporarily impassable can be expected periodically from about June 15 through September 15.

Fire History

Fire seasons extend from March through June and September through November. Only one fire, burning less than an acre, has occurred in the past 10 years, but the vegetative cover is dense enough on the canyon floor to support a wild grass and brush fire at any time during the fire seasons.

Terrain

Chaco Canyon extends from the west boundary of the monument for 25 miles in a southeasterly direction to its headwaters at the base of the Continental Divide. At about the southeast boundary of the monument, the relatively flat canyon floor widens to a maximum width of about 1 mile. The sandstone cliffs rise vertically to a height of 100 to 150 feet and a short distance above these cliffs is a second broken cliff line about 50 feet in height which runs parallel to the first. The Chaco Wash itself is a 30-foot-deep vertical-walled channel almost 300 feet wide, which meanders down the center of the canyon floor.

The Chaco and three main tributaries, the Gallo, Fajada, and Mockingbird Washes, come together within the monument. Near the west boundary the Chaco Wash joins the Escavada Wash to become the Chaco River, which flows into the San Juan River near Shiprock, New Mexico, some 65 miles to the northwest.

Soil

Barren rock, or a very light soil cover, is usually found on the mesas in the vicinity of cliff tops, with progressively deepening soil cover on more sheltered locations beyond the edges of the cliffs. Core drilling, made in 1963 to a depth of 200 feet on the canyon floor immediately adjacent to the monument's Gallo entrance, showed uninterrupted deposition of sandy-clay soil over the entire depth of the test.

The soil composing the canyon floor is predominately very fine wind-blown or water-borne clay-like particles mixed with coarser particles of disintegrated sandstone. When dry it is very hard and compact to at least a depth of 6 to 8 feet. Percolation is generally slow. The surface washes away rapidly during summer rainstorms. A distinctive quality of the soil is that it is very subject to "piping" which is said to be caused by the presence of a high ratio of salts and alkalis, which dissolve in water to leave voids in the soil composition. Pumice-block buildings and concrete slab floors, walks, and entries, built from 1952 to 1958, have cracked badly.

Water

There are no permanent lakes, streams, or impoundments within 15 miles of the monument. Domestic water for the Fajada (Headquarters) area is obtained from two shallow wells excavated in the Chaco Wash. A more adequate and dependable supply of water is expected from the recently completed and tested deep well located in the utility area.

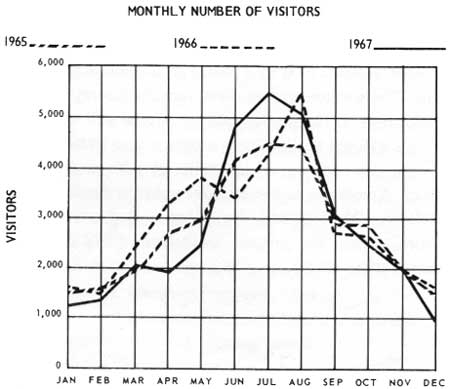

VISITOR USE

Visitor use at Chaco Canyon has increased steadily in recent years—from 2,013 in 1950 to 28,830 in 1960 and 32,943 in 1967. This is in spite of road conditions which most travelers of today consider intolerable and try to avoid. As access roads are improved and paved in this vicinity, substantial increases in visitation can be anticipated.

All visitors to Chaco Canyon now arrive by car and out-of-state travel accounts for approximately half of the total. Most of the visitors come in family groups, with about 4 percent in organized or special tour groups. The average length of stay is 4.5 hours for non-campers and 18 hours for campers. At the present time only about 8 percent of the visitors camp. During the heavy travel season, which extends roughly from April through September, weekend travel is heaviest with a second peak during midweek. Slightly over half of the visitors arrive at the monument from the north.

VISITOR USE

| Activities | 1958 | 1963 | 1966 | 1967 |

| Conducted Trips | 1,200 | 2,519 | 4,321 | 2,565 |

| Self-Guiding | 4,409 | 10,446 | 12,660 | 12,797 |

| Evening Program | ---- | 586 | 1,378 | 1,446 |

| Overnight Use: | ||||

| Tents | 919 | 1,473 | 2,302 | 2,438 |

| Trailers | 25 | 125 | 260 | 330 |

| Picnicking | 1,259 | 2,100 | 3,600 | 4,200 |

|

| This highly stylized bird-shaped pitcher demonstrates the abstract skills of some unknown potter. (Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History) |

LAND CLASSIFICATION

No lands at Chaco Canyon have been identified as Class I (High Density Recreation) or Class IV (Outstanding Natural).

The campground, visitor center, residential and maintenance area and all major public roads including the one-way loop road on the floor of the canyon have been identified as Class II (General Outdoor Recreation). Portions of the mesa tops with no significant ruins have been designated Class V (Primitive).

Only the major ruins have been identified as Class VI (Historic and Cultural) and the major portion of the area is Class III (Natural Environment). As additional study and research identifies other significant prehistoric features, they will also be identified as Class VI.

|

| LAND CLASSIFICATION. (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

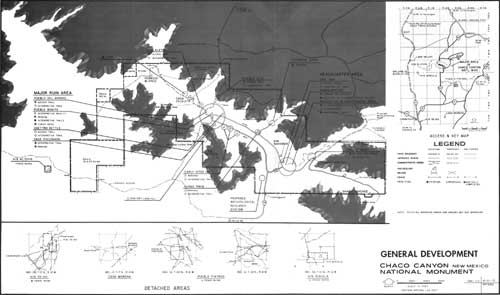

| GENERAL DEVELOPMENT. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

master_plan/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 16-Apr-2010