|

After carefully reconnoitering the Federal lines, Gordon settled on

Fort Stedman as the best place to attack. An enclosed field redoubt

located on the crest of Hare Hill, near the site of the fatal June 18

charge by the First Maine Heavy Artillery, the fort held four guns and

was closely supported by batteries north and south of it. Taking it

seemed an impossible task. The ground in front of Stedman was

crisscrossed with picket trenches, and the Fort was further protected by

two distinct lines of entangling obstacles. The main picket line was

delineated by a thick row of abatis—small, felled trees that were

piled together and interlocked. Directly girding the fort itself was a

heavy seeding of breast-high fraises—angled rows of logs with their

ends sharpened to points. These stakes were planted about six inches

apart and strung together with telegraph wire.

|

ROBERT E. LEE PHOTOGRAPHED ON HIS HORSE TRAVELLER AT PETERSBURG.

(DEMENTI-FOSTER STUDIOS, RICHMOND, VA)

|

Gordon's solution was worthy of its target. First, while it was

still dark, working parties would open avenues through the Confederate

defenses by quietly removing any obstructions. Then, using these

openings, squads of picked men would infiltrate forward, take out the

enemy's advanced pickets and listening posts, and open gaps in the

abatis. Through these holes would come fifty axmen whose task it was to

chop away sections of the fraise belt. Right on their heels were three

storming parties of a hundred men apiece who were to capture Fort Stedman and its

supporting batteries. Once the leading edge of the enemy's line had been

secured, a picked force would pass through to seize strongpoints in the

Union rear to prevent reinforcements from coming up. Only after the

last group had cleared the approach routes would the bulk of Gordon's

infantry cross the no-man's land to enlarge the initial penetration. As

an added incentive, a major Federal supply depot was located at Meade

Station, one mile behind Fort Stedman.

|

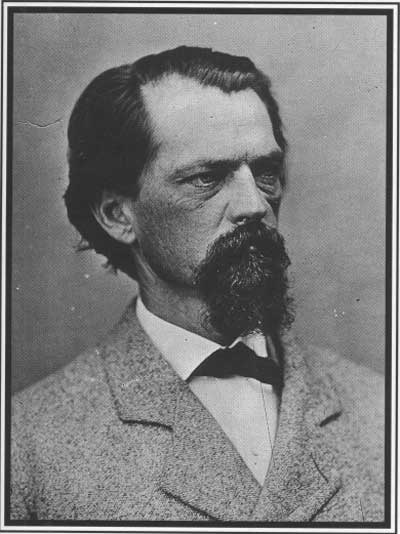

MAJOR GENERAL JOHN B. GORDON (NA)

|

For this operation Lee had allotted Gordon almost his own entire

corps plus two brigades from another division, some 11,500 men in all,

with the promise of 8,200 more once the attack developed. Additionally, a full cavalry

division would be waiting for word to dash forward here to spread havoc

and terror throughout the rear echelon. As Gordon finished his briefing,

Lee asked a few operational questions that the young corps

commander answered. After pondering matters for another twenty-four

hours, Lee gave the plan his blessing. The object, according to Gordon,

was no less than "the disintegration of the whole left wing of the

Federal army, or at least the dealing of such a staggering blow upon it

as would disable it temporarily, enabling us to withdraw from Petersburg

in safety." The attack was set for March 25.

At 9:00 P.M., March 24, while Gordon's men were beginning to mass for

their assault, a boat carrying President Lincoln, his wife, and son,

arrived at City Point. Anxious to escape the intrigues of Washington,

and wanting to be near the front when the end came, Lincoln had

gratefully accepted an invitation from Grant to visit. His schedule was

a busy one, including a review of troops that would take place near

Globe Tavern on March 25.

The opening phases of Gordon's attack plain went off with few

hitches. The working parties cleared the Confederates' own obstructions

and the advance squads silently eliminated the enemy's forward

positions. Brigadier General James Walker, commanding one of Gordon's

divisions, remembered the moment that the storming parties went

forward. "The cool, frosty morning made every sound distinct and clear,

and the only sound heard was the tramp! tramp! of the men as they kept

step as regularly as if on drill."

The predawn gloom erupted in blinding tongues of flame as the parties

met defensive fire from Fort Stedman and its flanking batteries. The

initial Union response was ineffective, and well before 4:30 A.M.

Stedman and Batteries X and XI had been captured. Rebel soldiers also

overran two regimental encampments located nearby, and many of the

sleepy Federals were clubbed down as they staggered from their tents in

alarm and panic. John Gordon himself crossed the no-man's land with the

first main wave of infantry to assess how the assault was

progressing.

|

CONFEDERATE COLQUITT'S SALIENT ACROSS FROM FT. STEDMAN. (LC)

|

|

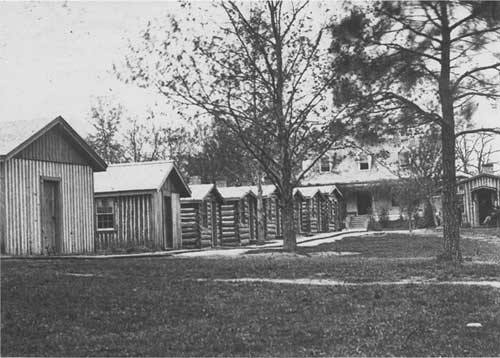

GRANT'S CABIN HEADQUARTERS (IN FOREGROUND) AT CITY POINT THE EPPES HOME,

"APPOMATTOX," IS TO THE RIGHT. (LC)

|

Gordon found that his success up to this point had been deceptive.

"Despite taking all the initial objectives, the follow-up attacks had

failed to widen the breach." South of the breakthrough, Fort Haskell

remained in Union hands, while north of it Federal Battery IX barred his

way. And then Gordon learned that the deep penetration effort of the

picked force had also failed when the guides had lost their way in the

darkness. Dawn was close at hand, and each passing minute made it that

much easier for the Yankee artillerymen holding an enfilading position

on both Gordon's flanks to target his troops. Gordon informed Lee that

the gamble had failed, and he received permission to withdraw his

men.

Some of the troops managed to scramble back across the no-man's

land, which was raked by a murderous artillery and musketry cross fire.

Those who did not immediately escape were pinned against the captured

entrenchments by a massive Union counterattack that rolled forward at

7:45 A.M. "The whole field was blue with them," recalled one dazed

Confederate.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

FORLORN HOPE

In a desperate gamble to force Grant to contract his lines long

enough to open an escape route from Petersburg, Lee commits nearly half

his available force to a surprise dawn attack on Union Fort Stedman.

Despite an initial success, the Confederate troops (under Maj. Gen. John

B. Gordon) cannot exploit their breakthrough. Union counterattacks

later that same morning (shown here) recapture all of the lost line and

many of Gordon's men. Follow-up Federal advances elsewhere capture key

portions of the Confederate picket line.

|

The Fort Stedman affair had been a costly failure. Lee had gained

nothing at a loss later estimated at about 2,700 men. Federal casualties

were perhaps 1,000 all told. What Gordon had termed the "tremendous

possibility" had proven no more than a fragile hope based on wishful

thinking.

This entire operation, which had required almost half of all the men

available to Lee, merely delayed by a few hours the review Lincoln had

planned with his troops. When, at midday, the president and his

entourage rode on the Military Railroad to Patrick Station, he was shown

1,500 prisoners taken in the morning's fight. General Meade started to

read aloud a message from the officer commanding the Stedman front, but

Lincoln stopped him and, pointing to the POWs, said, "there is the

best dispatch you can show me."

Reasoning that Lee must have had to strip his lines to supply Gordon

with troops, the commanders of the Federal Second and Sixth Corps

pressed their fronts and successfully overran large sections of the

Confederate picket lines. According to General Humphreys of the Second

Corps, "Under cover of the artillery and musketry fire of their [main]

works the enemy moved out repeatedly with strong force at several points

to recapture their picket intrenchments, but were always driven back."

These operations cost Humphreys 690 men.

Along the lines in front of Union Forts Fisher and Welch, an officer

from the Sixth Corps watched as the Third Brigade of the Second Division

was given orders to advance and capture the Rebel picket line. "The

brigade gallantly executed the order, and, notwithstanding the rebels

brought nine pieces of artillery to bear upon it, and sent

reinforcements to the point, the ground was held." Losses to the Sixth

Corps this day were about 400. Confederate casualties in these actions

were 1,300.

This was the true Union victory of March 25. The Federal army now

held advantageous positions that could be used to launch attacks on

Lee's lines with a greater chance of success than before. The

situation was summarized by a newspaper editor who wrote: "Thus, instead

of shaking himself from Grant's grip, Lee had only tightened it by this

bold stroke." In the words of a North Carolina soldier who had survived

the operation, the Confederate attack on Fort Stedman "was only the

meteor's flash that illumines for a moment and leaves the night darker

than before."

While Grant's pressure had kept Lee fully occupied at Petersburg,

military affairs elsewhere in the Confederacy had gone from bad to

worse. Following his capture of Atlanta, General William T. Sherman had

conceived and carried out his "march to the sea," which brought his

armies into Savannah, Georgia, on December 21. After a brief pause to

regroup, Sherman had marched north into the Carolinas, fought and won a

major battle at Bentonville, North Carolina, on March 19 and 20, and was

encamped around Goldsboro awaiting dry roads to continue toward

Richmond. Confronting him, but barely opposing him, was all that

remained of the once powerful Confederate western army, now led by

General Joseph E. Johnston.

|

THE MARCH 25 CONFEDERATE ATTACK ON FT. STEDMAN. (HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

|

CAPTURED CONFEDERATE BATTERY EIGHT USED TO FIRE ON GORDON'S TROOPS. (NA)

|

In the Shenandoah, Sheridan had crushed the Rebel Army of the Valley

at Cedar Creek on October 19 and spent the next months consolidating

Union control of the region. Satisfied that there was no longer any threat there,

Sheridan brought his powerful cavalry force back to Petersburg and

rejoined Grant in late March.

With Sheridan's arrival, Grant had the mobile striking force he

needed to end the siege. He worried that Lee would still find a way

to slip out of Petersburg and march south to unite with Johnston.

|

With Sheridan's arrival, Grant had the mobile striking force he

needed to end the siege. He worried that Lee would still find a way to

slip out of Petersburg and march south to unite with Johnston,

so he was anxious to cut off Lee's best route in that direction, the

South Side Railroad. To accomplish this, Sheridan was instructed to

advance west from the Union lines to Dinwiddie Court House on the

Boydton Plank Road. From there he would ride north eight miles to reach

the railroad tracks. While Sheridan was moving, Federal infantry would

also march to the west to secure the Boydton Plank Road below Burgess'

Mill and to challenge the enemy's entrenchments dug along the White Oak

Road.

The infantry, Warren's Fifth Corps, made contact first and engaged

Lee's men in some sharp fighting along the plank road on March 29. A

large-scale follow-up action on March 31 moved the Federal

infantry closer to Lee's White Oak Road line, but the position itself

remained in Confederate hands. This proved to be a touch-and-go affair,

with several of Warren's divisions routed by much smaller Rebel units

before reinforcements stabilized the situation,

Sheridan, on March 31, fought a day-long battle around Dinwiddie

Court House. His movement had been reported to Lee,

who dispatched a force of infantry under Major General George E.

Pickett and cavalry led by Major General Fitzhugh Lee. The two proved

too much for Sheridan's men, who, by nightfall, had been pressed back to

a tight perimeter around the village. Sheridan's call for help was

answered by Grant, who ordered the nearest infantry, Warren's, to come

to his aid.

Sheridan reported directly to Grant, while Warren took his orders

from Meade (who got them from Grant), so there was some delay and

miscommunication as Warren carried out his new instructions. His march

toward Sheridan was detected by Pickett, who, fearing the enemy would

get in his rear, pulled back. Pickett wanted to take position behind

Hatcher's Run, but Lee ordered him to halt short of that point to protect a key road

junction known as Five Forks.

|

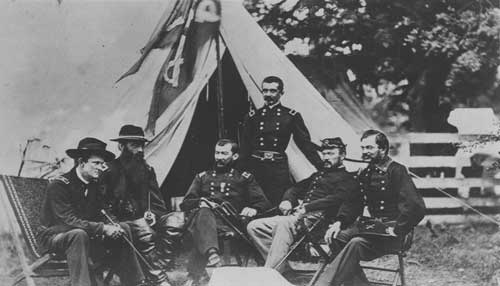

PICTURED (L—R) ARE WESLEY MERRITT, DAVID GREGG, PHILIP SHERIDAN,

HENRY E. DAVIS, JAMES H. WILSON, AND ALFRED TORBERT. (NA)

|

Grant had placed Sheridan in overall command of the operation and,

worried about Warren's past lack of aggressiveness, had taken the

unprecedented step of providing Sheridan with advance approval to

relieve Warren of command should the cavalryman feel it was necessary to

do so. By midmorning Sheridan's men had located the entrenchments Pickett's

men had thrown up along the White Oak Road at Five Forks. In addition

to the cavalry and infantry that manned the mile-and-three quarters

line, the Confederates had also posted cannon at a few points with a

field of fire. Sheridan's men spread out to develop the extent of the

position, and their scouting reports erroneously placed the enemy's

left flank much farther east than it was.

|

THE HISTORY OF POPLAR GROVE NATIONAL CEMETERY

The Virginia dogwoods were in blossom in the

spring of 1865 when the Civil War, America's greatest tragedy,

finally came to an end. The four years of conflict on Virginia's bloody

battlefields would close with a gentleman's peace at Appomattox Court

House on April 9, but not without a great loss of human life. Over

618,000 Northern and Southern men would give their lives as a direct

result of this war, many actual battlefield casualties. In July of

1862, the United States Congress passed legislation giving President

Lincoln the authority to purchase cemetery grounds "for the soldiers

who shall die in the service of their country." Thus efforts began for

the establishment of national cemeteries for Northern soldiers killed

on Southern battlefields.

In Petersburg and surrounding areas, work

would not commence on this directive for about a year after the war

ended. During the nine-month campaign most Federal soldiers were buried

on the field where they fell. In 1865, the U.S.

Christian Commission located over ninety-five separate burial sites

for the approximately 5,000 Union soldiers killed in action during the

siege.

|

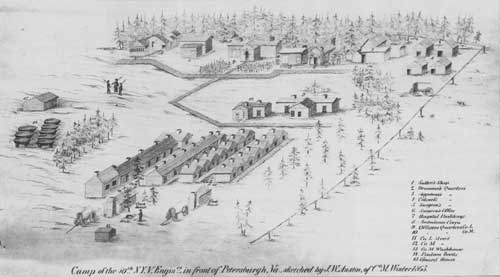

THE FUTURE SITE OF POPLAR GROVE NATIONAL CEMETERY DURING THE SIEGE.

(COURTESY OF VIRGINIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

On April 17, 1866, Lt. Colonel James M. Moore began his survey of

the Petersburg area for a possible location to establish a permanent

national cemetery. Rev. Mr. Thomas B. Flower's farm on Vaughan Road,

about four miles south of the city, was chosen.

During the war the area had been used as the campground of the 50th

New York Engineers, who had constructed a gothic-style pine log edifice

named Poplar Grove Church. Left by the army, it was used by local

residents to replace the nearby Poplar Springs Meeting House, destroyed

during the fighting.

With their base now established, a "burial corps" was assembled to

recover the scattered graves. About one hundred men were equipped with

twelve saddle horses, forty mules, and ten army wagons. Using this

equipment, the actual search and recovery began.

An observer described the operation:

Some had been buried in trenches, some singly, some laid side by

side and covered with a little earth, leaving feet and skull exposed;

and many had not been buried at all. Throughout the woods were scattered

these lonely graves. The method of finding them was simple.

A hundred men were deployed in a line a yard apart, each examining

half a yard of ground on both sides as they proceeded. Thus was swept a

space five hundred yards in breadth. Trees were blazed or stakes

set along the edge of this space to guide the company on its return. In

this manner the entire battlefield had been or was to be searched.

When a grave was found, the entire line was halted until the teams

came up and the body was removed. Many graves were marked with stakes,

but some were to be discovered only by the disturbed appearance of the

ground. Those bodies which had been buried in trenches were but little

decomposed, while those buried singly in boxes, not much was left but

bones and dust.

To confirm the latter, "On the 30th of July, 1866, 300 bodies

were taken out of the crater and the corpses were as perfect in flesh as

the day they were consigned to the pit, two years before. They were

fresh and gory, the blood oozing from their wounds, and saturating

still perfect clothing."

Remains were disinterred, then placed in plain wooden coffins.

When identifying headboards survived, they were nailed to the coffins.

Wagons transported remains to the cemetery.

A local resident who lived near Petersburg, Jennie Friend,

remembered these men: "The summer of 1866 was a time of searching through the country for

the Union dead, to place in the cemetery. Five dollars was given for

every collection of bones with a skull. So called spies, deserters, and

anything resembling the form of a man was money." All were taken up and

sold, and are now enshrined as heros in their well kept cemeteries . . .

the many dead lying about, with partially covered bodies, and worse yet

the un-earthing of these bodies, made the whole country sickly. In

August a terrible form of dysentery swept the community. In every

family sickness, and often death added to the distress that already

abounded.

The search for burials not only included the battlefields around

Petersburg but extended into the Virginia counties of Amelia,

Appomattox, Campbell, Chesterfield, Dinwiddie, Nottoway, Prince Edward,

Prince George, and Sussex. Many of these were locations traversed by the

armies during the final campaign to Appomattox. Bodies were recovered as

far west as Lynchburg. From July 1866 to June 30, 1869, disinterring

continued until the remains of 6,178 men were placed in Poplar Grove

Cemetery. Sadly, only 2,139 of these were positively identified.

Upon completing their assignments, the burial corps returned to

their work at the grounds chosen for reinternment around the New York

engineer's log church. An early visitor to the site remarked: "The

gem of the place was the church. Its walls, pillars, pointed arches,

and spire, one hundred feet high, were composed entirely of pines

selected and arranged with surprising taste and skill." The pulpit was

in keeping with the rest. Above it was the following inscription:

Presented to the members of the Poplar Spring Church, by the 50th

N.Y.V. Engineers. Capt. M.H. McGrath, architect. Another recalled:

We rode out to the Federal Soldiers Cemetery at Poplar Grove, and

tying our horses in the pine wood outside went in to wander for a while

among the graves. The place is laid out in sections, each section with

its melancholy forest of white head-boards on which are painted the

names and regiments of the dead men below. . . . I wondered who

the man was who lay beneath where his home was whether his mother was

still alive, away, perhaps,

in some far-off part of the world, wondering what had become of her

boy, that she had not heard from him for so long, but still hoping that

one day he would return to gladden her heart in her declining years.

Here he lay, alas! sleeping his long sleep among the unknown dead.

|

DEAD CONFEDERATE SOLDIER IN TRENCH OF FT. MAHONE, APRIL 3, 1865. (LC)

|

The church survived until April 1868, when, because of its

deteriorated condition, the structure was torn down. The area where it

stood was then used for burial purposes.

The War Department administered the cemetery until August 10, 1933,

at which time the responsibilities were turned over to the National Park

Service. The only major change since that period of time was in 1934,

when the upright headstones were cut off and placed flush with the

ground to facilitate mowing. Only fifty non-Civil War internments

have been added to Poplar Grove since its inception, the last being in

1975. Today the cemetery is closed to burials. Some of the last Civil

War soldiers to be buried there were twenty-nine recovered on the

Crater Battlefield in 1931. They were buried with full military

honors.

—Chris Calkins

|

|

|