|

Garrison Reservoir Geology, Paleontology, Archeology, History> |

|

PREHISTORY TO HISTORY IN THE GARRISON RESERVOIR

THE HISTORIC BACKGROUNDS

The early years of the nineteenth century brought a remarkable influx of traders, voyageurs, and others to the Indian village communities of the upper Missouri River. Here they saw a lifeway already in decline. As unknowing participants, they witnessed the inevitable collapse of the Village-Farmer culture that had once dominated the Missouri in its long course through the northern Plains. In 1804, the Lewis and Clark expedition found the Hidatsa (or Gros Ventres) and closely allied groups living in three villages at the mouth of the Knife River, with their linguistic relatives, the Mandan, in several villages situated a short distance downstream. The Arikara, a people of similar culture but speaking a different language, were still living far to the south, concentrated in three villages above the Grand River, a short distance upstream from the modern city of Mobridge, South Dakota.

These peoples were few in number and not always at peace among themselves, but by 1800 they were clustered together in fortified villages for protection against the bands of mounted hunters who were progressively extending their control over the Plains. Once the village peoples had been more numerous. Their progenitors, or at least people with a similar culture, left their traces along the Missouri and many of its tributary streams, extending from Nebraska to central North Dakota. Disease brought by the White man, particularly epidemic smallpox, and increasing pressures from other Indian groups reduced their numbers and compressed the villagers into the pitifully few communities known from historic records. Only a portion of this long and complex story can be illustrated in and around the Garrison Reservoir, but it is an essential part, dealing with the end of aboriginal life and the beginning of the Indian reservations as they are known today.

When visited by the noted German traveler, Prince Maximilian of Wied, in 1833, the Mandan and Hidatsa were still settled in substantially the same region in which they had been met by Lewis and Clark, but drastic changes were soon to come. In 1837, both groups again suffered severely from smallpox, which depopulated the villages and hastened the decline of the old ways. The following year, the Arikara settled in the abandoned Fort Clark Village. This was not the first time that they had intruded as unbidden guests among the Mandan. In 1823, following an inconclusive clash with troops under command of Col. Henry Leavenworth, the Arikara had abandoned their villages above the Grand River and had settled briefly, adjacent to the Mandan. Soon, however, they returned to the south, to wander for a time as nomadic hunters on the Plains. Only in 1837 did they return, occupying the Fort Clark Village. The Hidatsa, with the remnant of the Mandan who had continued to live among the Arikara interlopers, moved to the north in 1845, building Like-a-Fishhook Village a short distance above the site of the present Garrison Dam. Still other Mandan remained south of the reservoir area, keeping a tenuous truce with the warlike Sioux, but by 1860 they too had taken refuge among their kinsmen to the north.

The Arikara continued to resist the pressures of the nomadic hunters, but early in the 1860's they also were in the Garrison area, established at two locations, Star Village and Heart Village, near the Like-a-Fishhook community. By 1862, the Arikara had become a part of the latter village, thus completing the consolidation of the peoples now known officially as the Three Affiliated Tribes.

The trials of the Mandan, the Hidatsa, and the Arikara were not yet over. Even in their refuge, raids by war parties of Sioux were a constant threat, until the collapse of the Plains horsemen following the military campaigns of the 1870's. For our purposes here, however, the gathering of the Three Tribes represents the end of a series of movements and counter-movements which we can see as a long, slow drift from the middle Missouri region toward the north. This is the history as we know it from traditions and from the early accounts of travelers, traders, and explorers. It is history with blank spots and uncertainties, but history nonetheless. But what went before?—these peoples were not newcomers to the Missouri, as their traditions well attest. At the moment, we have only glimpses of their prehistory, that is, their way of life and their wanderings before the appearance of European and American influences. Origin myths and traditional migrations known from the reports of early travelers and modern ethnologists may provide a clue. As an example, the Mandan tradition carries bands of wanderers up a great river, presumably the Mississippi, to the land of evergreen trees, then south and west, ultimately reaching the Missouri at a point north of the Nebraska border. Such stories might well hold a core of truth, but the ultimate solution falls within the realm of archeology.

PREHISTORY

At the moment there is little firm evidence that man lived permanently in the Garrison Reservoir area prior to the appearance of the aboriginal farmers. At Rock Village, a short distance above the Garrison Dam, an early occupation was found suggesting that a hunting people were exploiting the locality before the village proper was established, but the remains are scanty and not particularly revealing.

The earliest of the primitive agriculturalists built their villages on the low terraces that are a constant feature along the Missouri. These are remnants of older river fills, reflecting climatic fluctuations that followed the waning of the great ice masses that held much of the northern Plains during the Pleistocene Period. The floodplains were not suitable for more than brief or seasonal occupancy since they were subject to flooding by the spring runoff. On the other hand, the Village-Farmer communities came to rely upon the bottomlands for their garden plots; these silty, well-watered soils were easily broken and readily cultivated with primitive tools.

|

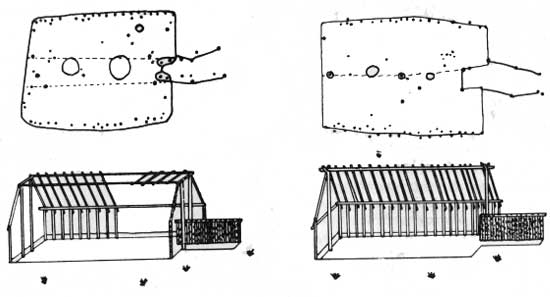

| (Left) Floor plan and suggested reconstruction of a long-rectangular house with a gabled roof. From: Wesley R. Hurt, "House Types of the Over Focus, South Dakota," Plains Conference News Letter, vol. 4, No. 4. (Right) Floor plan and suggested reconstruction of a long-rectangular house of the gambrel roof type. From: Wesley R. Hurt, "House Types of the Over Focus, South Dakota," Plains Conference News Letter, vol. 4, No. 4 |

The early village folk built large, rectangular houses, with massive framing, often of cedar timbers. Some of these structures were as much as 60 feet in length. The floor was usually a shallow excavation extending to a depth of one or two feet below the surface, with access to the out-of-doors provided by a sloping earthen ramp. Posts to form the walls were set just inside the margin of the floor excavation, with other timbers placed along the centerline to support the ridgepole. The roof was probably a simple gabled form, although in some instances, a double-sloped gambrel type may have been used. We have no good evidence for the outer covering but it is possible that mats or grass were used. One or more fireplaces were to be found along the centerline of the house, with storage space for food provided by pits excavated beneath the floor. The size and interior arrangement of such structures suggests that they housed more than one family, perhaps a lineage or group of related families. Surely the massive timbers and the magnitude of the floor excavations indicate some sort of group effort; it is obviously more than a small family unit could manage alone.

|

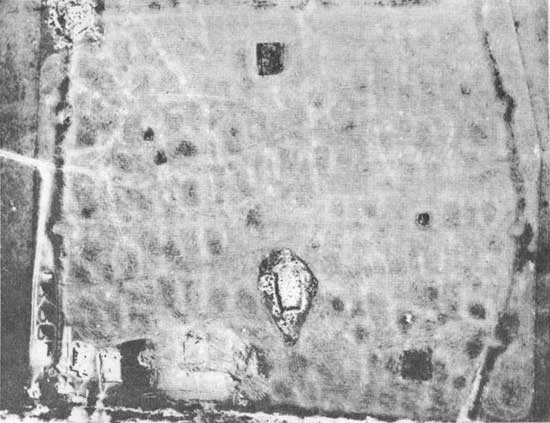

| Aerial view of the Huff Site, an early village in south-central North Dakota. The defensive ditch or moat, with projecting bastions, and rectangular house depressions arranged in irregular streets, are plainly marked by darker vegetation. The photograph was taken during the summer of 1960 while archeological excavations were in progress. Exposed house floors can be seen at lower left and lower center. Photo: Courtesy of W. Raymond Wood, State Historical Society of North Dakota |

The arrangement of individual houses within the village also implies a high degree of organization and perhaps a strong, centralized village authority. Houses were sometimes placed in regular rows, resembling streets in our own communities. This is particularly true of the older villages. With the passage of time, inroads of foraging peoples, or perhaps bloody internecine strife, brought a need for protection. Elaborately fortified villages resulted, defended by a strong perimeter formed by a ditch or dry moat, usually rectangular in plan, and backed by a timber stockade.

The artifacts made and used by the Long-Rectangular House people, their tools, weapons and ornaments, were simple but surprisingly varied. Pottery vessels with sparsely decorated rims and lips, digging tools or scoops made from the horn core and frontal bone of the bison, scapula hoes, small triangular arrow points, and a profusion of stone scrapers and knives are characteristic. Exotic items, such as ornaments of copper and sea shell, were present but less frequent. Simplicity is the keynote here, yet these people had many possessions, and must have had a keen aesthetic sense. It was a self-sufficient life, but the presence of "foreign" material (obtained by trade from other native groups) indicates the existence of widely-ranging contacts, especially to the south, and east.

Similar villages of long rectangular houses, sometimes with divergent ground plans, are found along the Missouri River to the south, with related sites occurring as far to the east as present-day Iowa. There is evidence indicating that the more southerly villages are earlier, thus suggesting an upriver drift or migration. What is the ultimate source of the early village lifeway. Unfortunately, we can suggest only possibilities. Similar fortifications are found in the southeastern United States, with one notable example as far north as Wisconsin. Exact counterparts of the rectangular house have not been found, yet there is a good chance that they, too, came from the south, perhaps with contributions from elsewhere.

With the passage of time, amounting to several centuries, a new and radically different style of house made its appearance. Dwellings were built on a circular plan with a short passage or antechamber serving as a doorway. Where present, floor excavations were shallow, often formed merely by the removal of sod or the smoothing of surface irregularities prior to house construction. The structural framework was based upon four (and sometimes more) centerposts set on radii from a central firepit and connected by sloping rafters to a row of short vertical wall timbers arranged around the perimeter of the floor. Except for a smoke hole over the hearth, the entire framework was covered with layers of grass and twigs, with a final mantle of earth. The resulting dome-shaped structure was essentially the same as the earth lodge used by the Village-Farmers during the historic period.

The circular dwelling did not appear full-blown. As yet, evidence is fragmentary, but it is increasingly certain that this house-type was preceded, here and there, by square houses, or structures that were essentially square but with rounded corners or slightly curved walls. Such house plans suggest a close relationship to certain prehistoric dwellings found in Nebraska. Indeed, it was probably an incursion of native peoples from present-day Nebraska that brought such houses into the Dakotas.

|

| An aerial view of the No Heart Creek Village, a short distance above the mouth of the Cheyenne River in north-central South Dakota. The surviving remnant of the defensive ditch is still quite deep and the circular house depressions, irregularly arranged within the enclosure, support a lush growth of grass and brush. Photo: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

Many of the earliest villages of the Circular House people are no more than a loose agglomeration of houses scattered, singly or in groups, along a terrace edge. In some instances the villages extended literally for miles. In addition, there are fortified settlements, usually a small group of houses surrounded by a ditch of circular plan. These may represent a change in the pattern of occupation, perhaps an increasing need for protection. On the other hand, they may constitute refuges, occupied in time of danger by the people who normally lived in the more scattered dwellings. The solution of this problem is for the future.

Accompanying the new type of houses and the altered pattern of fortification were new styles of pottery and new variations of other tools and implements. By the mid-eighteenth century, a few objects of European and American manufacture were being used. There is evidence of change, of new ideas, and, perhaps, of new peoples, but essentially the old lifeway continued as before.

The Circular House occupation is relatively late, but it must have overlapped the earlier occupation in time; one did not immediately supplant the other. The rectangular house complex ultimately disappeared. There must have been an intermingling of peoples and techniques, an amalgam of the old with the new, a coalescing of traits, bringing together differing lifeways from widely separated areas, from which emerged the village peoples as they were known during the early historic period.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sec6.htm

Last Updated: 08-Sep-2008