|

Garrison Reservoir Geology, Paleontology, Archeology, History> |

|

CHRONOLOGY IN THE MISSOURI VALLEY OF NORTH DAKOTA

Thus far, little has been said about chronology, that is, the exact time or span of years during which the archeological sites of the upper Missouri were living, functioning villages. This has been deliberate; most dates are tentative and at best are little more than guesses based upon the available evidence. This much can be said—the Long Rectangular House people lived in the region for a long period, perhaps 300 years or more, before their way of life was replaced by the Circular House tradition.

The first village people were present at least by A.D. 1350 and perhaps a century earlier. Prior to this time, related groups were settled along the Missouri River to the south. The Swanson Site, a small village a few miles north of Chamberlain, South Dakota, appears to date in the middle of the ninth century. Similarly, the Thomas Riggs Site, a village of long rectangular houses, situated in central South Dakota, was built in the thirteenth century.

In discussing the Circular House people we are on firmer ground. The lifeway characterized by circular earth lodges and associated artifacts was still functioning at the time of contact by Europeans, and continued to function, although with diminishing vigor, until the beginning of the reservation period. The circular house tradition was present in central South Dakota during the middle years of the sixteenth century, and within the next one hundred years, became widely distributed along the Missouri. In central North Dakota, circular houses irregularly arranged within a fortified perimeter were characteristic by the early seventeenth century at least. The villages in the Garrison Reservoir were merely late representatives of this long lived tradition.

Thus, the village peoples of the Missouri River can be bracketed within the last 1100 years, but sites seem to become more recent as one moves toward the north. This, again, implies an upriver drift of the village people; the earliest of their villages might well be sought in the south.

ARCHEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS IN THE GARRISON RESERVOIR

More than one hundred and fifty archeological and historic sites were found during the field surveys in and adjacent to the Garrison Reservoir. In addition to the earth-lodge villages, these included a number of small campsites, earthen mounds, eagle trapping pits, stone cairns, a military fort, several trading posts and other remains of the White man's frontier. Only a relatively small number of these could be investigated, in view of the limited time available. Furthermore, only a few could be excavated to the extent necessary for complete interpretation. Nonetheless, the work done provides an informative picture of aboriginal and early White occupation.

THE NATIVE VILLAGES

Most of the aboriginal sites excavated by the Smithsonian Institution and cooperating state agencies fall into the late period of occupation by the Village-Farmers. The presence of still earlier hunting groups, indicated by sparse remains from Rock Village, has already been mentioned. Probably other such early sites were present but are so deeply buried in terrace deposits that they were not discovered. A number of camp sites, perhaps temporary stopping places during hunting trips, were excavated but they appear to relate to the prehistoric or early historic farmer occupation. Characteristically, they contain bone and other artifacts, as well as scattered fragments of pottery similar to types known from the permanent villages.

GRANDMOTHER'S LODGE

Only one site of the early village peoples was found within the reservoir. This was a single long-rectangular house, the venerated Grandmother's Lodge, situated on a low terrace overlooking the flood plain of Missouri. Traditionally, Grandmother, "The Old Woman Who Never Dies," and her grandson dwelt here. She was the patroness of gardens and crops—the corn, beans, and squashes so important to the village peoples. Excavation showed the lodge had two parallel rows of posts outlining a floor averaging two feet below the surrounding ground level. Large posts, ranging along the center line of the structure and paralleled by auxiliary supports at the sides, suggest that the roof was gabled. This is the most northerly example of a house of this sort. They are much more frequent along the Missouri to the south, extending as far as southeastern South Dakota. The artifacts, particularly the pottery, indicate a relationship to the earliest village occupation as it is known from southern North Dakota.

NIGHT-WALKER'S BUTTE-IN-THE-BULLPASTURE

The remainder of the excavated sites are included within the historic or the late prehistoric period. Here, as before, dating is difficult except for those sites documented by the historical record.

Perhaps the earliest of the undocumented sites is that called Night-Walker's Butte-in-the-Bullpasture, an isolated bluff-top village in a "badland" area of McLean County. There are other such inaccessible village sites in the Garrison Reservoir area. Tradition attributes all of them to a Hidatsa chief, Night-Walker, or "He Who Walks About in the Twilight." The name is synonymous with Wolf, probably referring to the "power or supernatural helper of the chief."

A number of circular lodges were excavated within the village. Artifacts were abundant and present in considerable variety. The inventory includes hoes and knives made from the shoulder blades of bison, bone and antler fleshers, short sled-runners of bison rib, and a number of objects manufactured from shell. A scattering of metal was found within the houses, indicating that the village, or at least part of it, falls within the period of historic contact. It should be emphasized, however, that trade objects often preceded the trader, passing from hand to hand, long before Europeans appeared on the scene. The metal objects found at Night-Walker's Butte, arrow points, knife blades, and the like, are utilitarian items, made from scrap material by the Indians themselves. The abundance and variety of trade objects characteristic of the known historic sites, are not present here. This suggests a relatively early date for the Night-Walker village—perhaps the latter part of the eighteenth century would be reasonable.

|

| Grandmother's Lodge after excavations were completed. The floor, rectangular in plan, was bounded by two parallel rows of postholes which indicate the original house wall. A third row, along the center line of the structure, held columns to support the ridgepole. A fire pit can be seen at right center, and the remains of a small sweat lodge to the left. Photo: Courtesy of the State Historical Society of North Dakota |

|

| Aerial view of Night Walker's Butte-in-the-Bull Pasture Village. A number of houses have been excavated and the remains of a defensive stockade, encircling the site at the edge of the Butte top, have been exposed. Photo: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

ROCK VILLAGE

More extensive excavations were made at Rock Village, a traditional Hidatsa site in Mercer County. The village was named for Emanuel Rock, a prominent outcrop of sandstone located nearby, which, in turn, probably derived its name from Manuel Lisa, the well-known White trader of the early nineteenth century. An unknown part of the village had been destroyed by the river but 35 to 40 closely spaced earth-lodge depressions remained. Except for the riverward edge, the village area was bounded by a moat or ditch which, at some time, had been enlarged to enclose 10 lodges that were added to the original village.

|

| Aerial view of Rock Village, situated on a low terrace in the Garrison Reservoir. A long trench, excavated in alternate five foot squares has been cut through the site to expose a deeply buried occupation by hunting peoples. The excavated remains of houses built by the Village-Farmers of a later time are visible to the right and left of the main trench. Photo: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

The remains of five earth lodges were excavated, all of them circular in ground plan. One of the structures requires special mention. Situated in the center of the village area, it had probably served for ceremonial purposes. The lodge was 70 feet in diameter, constructed on a four center post foundation, but with twenty outer posts, each averaging 1-1/2 feet in diameter—a massive structure! The outer wall was composed of leaners set in an irregular trench encircling the house. The entry passage was a close counterpart of those described for Rock Village.

|

| A partially excavated house at Rock Village. The structure was destroyed by fire and many of the charred timbers were still preserved where they fell. The narrow trenches marking the entryway can be seen at the upper left. The vertical pins (lower right) indicate unexcavated postholes. Photo: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project. Smithsonian Institution |

Approximately one-third of the house depressions and a large number of other occupational features were exposed by the archeologists. Houses were circular, averaging somewhat more than 40 feet in diameter. The structural framework was based upon four central supports set about a basin-shaped fire pit. The entry passages were enclosed by split timbers set on end in shallow trenches, a feature described historically for the Hidatsa.

Refuse, the debris of every-day life, was abundant in abandoned storage pits, in the defensive ditch, and, thinly spread, was found over much of the surface of the site. Objects of European or American origin were frequent but most of the tools were of native materials. Projectile points, tinklers and scraps of brass and iron constituted the bulk of the metal objects, but in addition, there were glass beads and even clay pipe fragments of European manufacture. Again, there is no exact date for the site but an examination of the trade objects present in the collection suggests that the village could have been inhabited in the 1830's, or even later. Construction of the village may have begun as early as 1800 or 1810.

|

| A small pottery vessel excavated at Rock Village. Photo: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

|

| Aerial view of Star Village, one of the last settlements of the Arikara prior to their amalgamation with the Mandan and the Hidatsa. The village was surrounded by a shallow moat and the lodge depressions were well preserved. The white areas mark excavated earth lodges; the large house near the center served for ceremonial purposes. Photo: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

The defensive ditch was notably shallow, reaching a maximum depth of two feet from the surface; however, the excavated dirt had been piled to form a low berm or encircling ring, thus adding to the effectiveness of the defenses. The bastions or strong points characteristic of the earlier village defenses were present neither here nor at Rock Village.

In view of the recency of Star Village and the brief period during which it was occupied, it is not surprising that artifacts were not found in large numbers and that objects of Indian manufacture, in particular, were few. A number of stone projectile points and nondescript items of bone and shell were excavated as well as a small quantity of native pottery. Objects of White origin, such as beads, files, knives, and nails, were some what more abundant.

|

| Bone-handled dagger found at Star Village. The blade is delicately engraved and is touched with gold leaf. Weapons such as this were common items in the Indian trade of the early 19th century. Photo: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

Heart Village, possibly a contemporary of Star Village, deserves a brief discussion. Tradition has it that, like the latter settlement, Heart Village was occupied during the winter of 1861-1862 by the Arikara as the last step in their upriver movement prior to their final settlement at Like a-Fishhook Village. The Heart Site was found in the wooded bottoms of the Missouri on what probably was once an island. The protected location is typical of a winter village. No material remains were found on the surface but thirty-five lodge depressions were apparent beneath the lush vegetation. The village was not excavated but appearances suggest that the life of the settlement was short at best.

With the brief occupation of Heart and Star Villages by the Arikara, the independent existence of the last of the Village-Farmer peoples of the Dakotas came to an end. Henceforth they were clustered together at Like-a-Fishhook Village, dependent on traders for necessities and upon troops for protection. In effect, the old life, precarious and crumbling for generations, was now at an end.

|

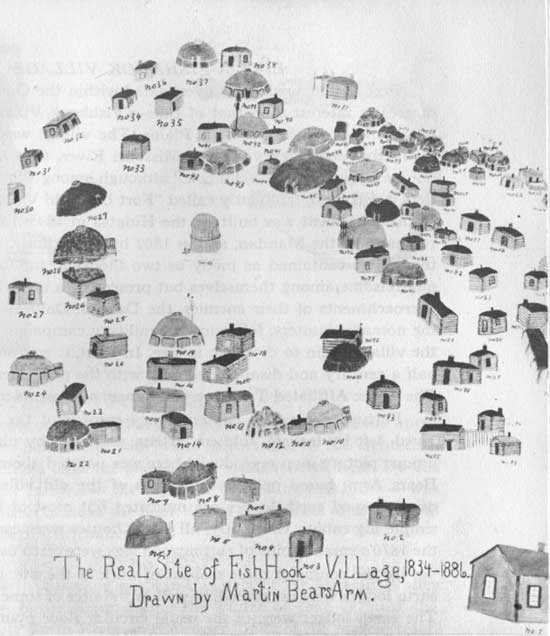

| A painting of Like-a-Fishhook Village (actually built in 1845), as recalled in later years by Martin Bear's Arm, a Hidatsa (Gros Ventres), showing the native earth lodges and log cabins used by the villagers. The frame building at lower right may represent the Indian Agency although the government buildings were actually located some distance beyond the village. Photo: Courtesy of the State Historical Society of North Dakota |

LIKE-A-FISHHOOK VILLAGE

Perhaps no single site investigated within the Garrison Reservoir is of greater interest than that of Like-a-Fishhook Village, the last earth-lodge village in the northern Plains. The village was established on a distinctive double curve of the Missouri River, thus accounting for the unique name, "Like-a-Fishhook," although among White traders and settlers it was more frequently called "Fort Berthold Village." The first unit of the settlement was built by the Hidatsa in 1845, followed shortly by remnants of the Mandan, and in 1862 by the Arikara. In the late 1860's the village contained as many as two thousand inhabitants, sometimes quarrelsome among themselves but presenting a united front against the encroachments of their enemies, the Dakota. Only after the collapse of the nomadic hunters, following the military campaigns of the 1870's, did the village begin to diminish in size. In total, it was occupied for nearly half a century and disappeared only with the permanent resettlement of The Three Affiliated Tribes on small farm allotments in the late 1880's.

Fortunately, many contemporary records of the village have survived, left by traders, soldiers, artists, and even by photographers. The unique picture map reproduced here was painted about 1900, by Martin Bears Arm, based upon recollections of the old village. A number of dome-shaped earth lodges are indicated but most of the structures are simple log cabins. Originally, all of the houses were earth lodges, but by the 1870's small cabins of cottonwood logs were often used.

In the course of three seasons of work at the site, a large number of earth lodges were excavated, as well as the sites of some of the log houses. The earth lodges were of the usual circular floor plan with four center posts and twelve to fifteen outer wall posts surrounded by an outer row of small leaners. The entryways were short passages of the sort previously described. The Arikara houses differed from the others in that the floors were shallower and the central posts were more widely spaced. Such distinctions are of considerable importance when attempting to disentangle the strands of history and prehistory in the Missouri Valley.

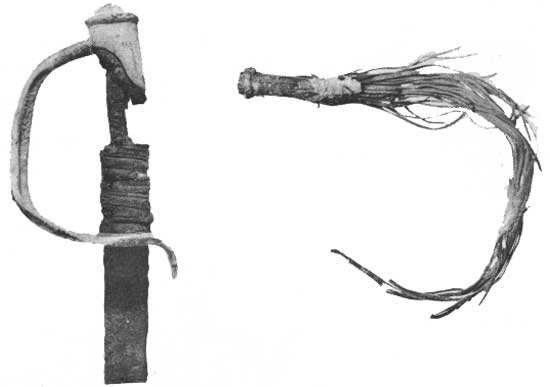

Tools and other artifacts of Indian manufacture were notably few but objects of White manufacture were present in abundance. Knives, axes, fragments of tableware, ornaments, and even a U. S. Cavalry saber were found by the excavators. Such objects are important indicators of a changing lifeway. The trading post or frontier store was replacing the self-sufficiency of the old life. Thus the rag-tag of debris has its story to tell, adding materially to our understanding of a primitive culture disintegrating under the impact of the modern world.

|

| (Left) U. S. Cavalry Saber, Model of 1840 excavated at Fort Berthold II. (Right) Remains of a leather quirt from Fort Berthold II. Photos: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

TRADING POSTS AND FORTS

Serious attempts at exploitation of the natural resources of the upper Missouri by White men began with trade in furs late in the eighteenth century, and continued until the period of permanent settlement. By this time, trade with the Indians—the suppliers of the furs and hides—was no longer profitable because of the depletion of the sources of supply and the changed nature of the frontier.

KIPP'S POST

One of the earliest trading posts in this part of the Missouri Valley was that built by James Kipp during the winter of 1826-27, near the mouth of the White Earth River, in the upper limits of the present reservoir. This post was the direct predecessor of the better-known major establishment of Fort Union, near the mouth of the Yellowstone River, the site of which is now a North Dakota State Park.

Kipp's Post seems to have been designed to open trade with the Assiniboin Indians (related to the Dakota or Sioux), one of several wandering nations of the upper Missouri, probably in an attempt to draw them away from British traders on the Saskatchewan River to the north. With Kipp was the famous Kenneth McKenzie (nephew of the Scottish explorer, Sir Alexander Mackenzie), who, in later years, was to rule the trade from Fort Union, and to be commonly referred to by other traders as "king" of the Upper Missouri Outfit, the principal operation of the Pierre Chouteau, Jr. Company.

Excavations made at the site of Kipp's early post provided wholly new information on the appearance of such small trading centers. This example included four modest log buildings within a small rectangular stockade and was equipped with a single bastion or blockhouse. An array of artifacts was obtained that is of significance because they include not only objects used in the trade at this relatively early date—even parts of a small cannon that may have provided some sense of security for the post—but numerous objects of native manufacture as well. The latter revealed that the years of this trading post were years of rapid change in the material culture of the native peoples of the region. With the entry of the traders, the Indians quickly found desirable substitutes for their own native artifacts—not only firearms, replacing the bow and lance—but other metal objects and glazed earthenware that supplanted many native tools and utensils. Here, too, were luxury goods such as glass beads and a host of other objects to catch the Indian eye.

|

| (Left) Half-axe or woman's axe, excavated at the site of Fort Berthold II. Photo: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution (Right) Silver gorget found at Fort Berthold II; an interesting example of the varied ornaments traded to the Indians. The object is engraved with the figure of a beaver, long the basis of commerce in the Missouri Valley. Photo: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

FORT BERTHOLD

White traders played an important role in the life of Like-a-Fishhook Village; indeed, they probably had a hand in the planning of the community. In 1845, the powerful Chouteau Company of St. Louis established a trading post immediately adjacent to the village. The first of the posts to bear the name Fort Berthold, so called in honor of a prominent partner in the firm, it continued as an important Company enterprise, operated by James Kipp and others, until destroyed by fire in 1862.

Meanwhile, opposition traders had also built near the village, but as usual, the "Company" succeeded in the old art of squeezing out the competition, eventually purchasing a large "opposition" fort as a replacement for Fort Berthold. The name of the earlier post was then transferred to the later one, which became a familiar landmark for the increasing number of visitors to the region. In the 1860's during the troubled years of the Indian Wars, Fort Berthold II became a base for military operations under command of General Alfred Sully and subsequently, served as headquarters for the first Indian agents for the Three Affiliated Tribes. Throughout the useful life of the fort, first as a trading post, then under military and civilian control, other lesser posts appeared to garner their share of the lucrative trade. These were of short duration and lack useful documentation. We know that they grew, competed briefly and disappeared, leaving a confused trail of local history, but their influence could never have been great.

Apart from the excavation of Like-a-Fishhook Village proper, investigations were also made at the sites of the two Fort Bertholds. The results were highly productive of new information, especially so for the earlier post. The location of this site had been completely obliterated with the passage of time. It was only after careful search, and finally, by the meticulous use of earth-moving machinery that the outline of the fort was exposed. The timbered stockade had been rectangular in plan, almost square, but with evidence that it had been enlarged at some time. A surviving sketch shows blockhouses at two corners. No direct evidence of these was found although the palisade line was broken or missing at the appropriate places. Perhaps the blockhouses were set on the surface, without deep foundations, so that no traces were preserved.

|

| One of the corner blockhouses of Fort Berthold II, photographed in 1879 by O.S. Goff. Photo: Courtesy of the State Historical Society of North Dakota |

The second Fort Berthold was larger, but otherwise very similar in plan. Excellent contemporary photographs show us the corner blockhouses, the high stockade, and the sod-roofed store houses within the enclosure. Although no part of the old buildings remained above ground, the archeologists were able to trace the stockade line, re-establish the foundations of the interior structures, and to recover many details of construction. The many artifacts excavated provide a unique picture of the give and take of daily life at the post, the sort of things that history books frequently do not reveal. Here we have the actual exchange of the fur trade, the knives, the beads, and the sundry items that Indian, trader and soldier used in his day-to-day activities. All this is doubly important in view of the fact that this was the scene of long and intimate contact between the first White residents and the native villagers, and at a critical time, when the old life of the villagers was disappearing, shattered by the White man's way, and merging into the modern era.

|

| Interior of Fort Berthold II. Photographed by Stanley W. Morrow, Yankton, Dakota Ty., c.1869. Photo: Courtesy of the W. H. Over Museum, University of South Dakota |

|

| The site of Fort Berthold II (1858-c. 1885) under excavation. The smaller rectangles projecting from opposing corners (lower left and upper right) are the sites of the two blockhouses. The unexcavated strips crossing the cleared area were balks left in place for study during excavations. The wider strip (center) provided access for earth-moving equipment. Photo: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

|

| Excavated site of the Commandant's Quarters, Fort Stevenson (1867-1883). The masonry foundation was found largely intact, and portions of decayed sill were still present. This was the last of the buildings of the post to disappear—about 1945, only six years before the site was excavated. Photo: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

FORT STEVENSON

With the 1850's, the United States Army made its appearance on the northern Plains, following the Indian agents and the missionaries, and leaving its own trail of historic sites along the upper Missouri. One of these, Fort Stevenson, used from 1867 until 1883, lay in the area of the proposed reservoir, not far above the site of the Garrison Dam. Fort Stevenson had served also as the location of an Indian school after its abandonment by the military and gave a name to the city of Garrison, nearby, and, in turn, to the dam and reservoir.

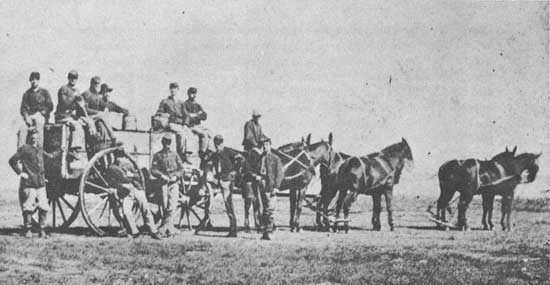

In view of the abundance of documentary evidence concerning the plan and appearance of the post during use, excavations were limited in scope. Apart from official archives of the fort, still preserved, there was even the published personal diary of General Philippe Regis de Trobriand, the officer commanding during the period of its construction, together with photographs and sketches made while the buildings were still standing. None of the buildings had survived above ground when the investigation was begun—the last, the home of the commandant, having been pulled down a mere five years before archeologists went to work studying the site.

|

| Water-wagon detail at Fort Stevenson, Dakota Territory ca. 1870. The teamsters, not in uniform, were probably civilian employees at the post. Drinking water was hauled from the Missouri River at this period; drive wells later simplified the problem of water supply. Photo: Courtesy of Dr. J. W. Robinson, Garrison, North Dakota |

|

| Indian children at the Fort Berthold Indian school, after 1883. The "Office" was previously an officers' quarters of Fort Stevenson, whose first commanding officer was General Philippe Regis de Trobriand, U. S. Army. His diary, published as "Military Life in Dakota," was written at the post in 1867. Of French ancestry and related to the famous explorer of the eighteenth century, de Trobriand participated in many of the major battles of the American Civil War and had served with the Armies of France. Photo: Courtesy of Dr. J. W. Robinson, Garrison, North Dakota |

Despite the abundance of surviving evidence contemporary with the use of Fort Stevenson, excavations added to knowledge of its plan and architecture, as well as to further understanding of everyday affairs at the post.

The story of man, as it is told in the upper Missouri, is long and complicated by the ebb and flow of cultures. It is a story of continued change, the old falling before or adapting to the new. Village Indians, Nomadic Hunters, Explorers, Traders, Soldiers, and Ranchers represent changing trends, new ideas and new forces, in short, new ways of life that have played their part in the shaping of the region. This is a continuing process. The construction of dams and the taming of the river are just one more step, bringing new ideas, new technologies, and new problems—another phase in the long history of the northern Plains.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sec7.htm

Last Updated: 08-Sep-2008