|

CRATER LAKE

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN:

RESEARCH

by Stephen R. Mark, Park Historian, revised 2003

|

Research Administrative History of Crater Lake National Park Stephen R. Mark Pacific West Region |

Introduction

This is the second chapter added to the administrative history of Crater Lake National Park that originally appeared in 1988. It utilizes both a chronological and thematic approach to how research has shaped park administration, a topic that has remained completely absent from almost all historical narrative on Crater Lake and other park areas. Readers will note particular emphasis on the relatively recent past, in part because of the comparatively high output of studies, but this is also due to how research activity has lately had a more intimate relation to administration of the park.

This narrative is not intended as an overview of past research, nor is it aimed at necessarily evaluating the relevance of that work to the present. It merely provides some background with which to organize a highly eclectic mix of studies employing methods ranging from experimental to empirical, but that generally employ some degree of comparative analysis. As to how the term is used in this chapter, research culminates in documents that address specific scientific or historical questions. The writing undergoes formal review, as part of publication or the printing required to complete contract obligations. Other kinds of information on park resources, such as unpublished field observations and data collection, or narrative reports by NPS staff, are not included in this chapter because this material was addressed (at least to some extent) in a previous chapter on resource management by Unrau.1 Like other kinds of administrative history, this narrative is organized chronologically, with emphasis placed on where research has affected park management.

As for key issues, the two most outstanding reflect their respective periods of park administration. The first was fundamentally tied to a focus on interpreting the forces that produced Crater Lake, as well as connecting it and Mount Mazama to a larger regional context. Much of that work revolved around the classic study by Howel Williams during the 1930s, yet Charles R. Bacon and others in the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) continue to revise and expand previous geological interpretation so that more is known about Crater Lake than any other caldera lake. The second arose during the early 1980s, as the NPS began to sponsor its own research efforts as a way of supporting newly initiated resource management programs. Whether the lake itself was changing became a concern, so that the need for special studies and a long-term monitoring program eventually made these endeavors a part of park operations.

Research Activities, 1886-1926

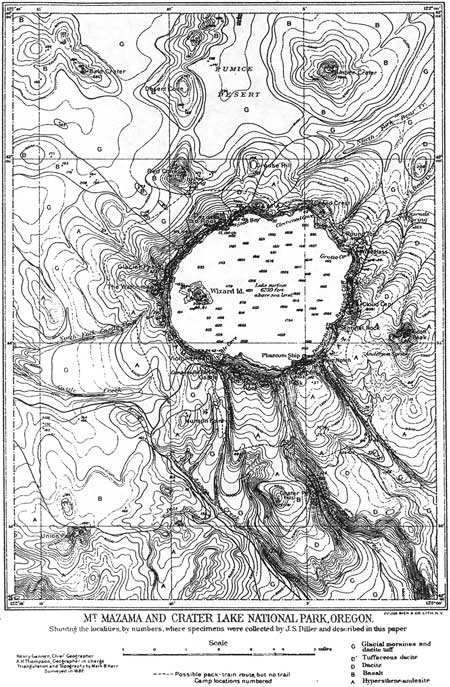

Although research may not have dominated park operations through time, it did influence establishment of Crater Lake National Park. One of the earliest bills aimed at establishing the park contains a line specifying that "said reservation shall be open to...those making scientific researches." This provision is usually attributed to the interest USGS geologist Joseph S. Diller and others had, beginning in 1883, of studying the volcanic phenomena associated with the climactic eruption of Mount Mazama. The provision for access by scientists (something Diller himself inserted) persisted in most of the bills aimed at establishing a national park at Crater Lake, including the one that proved ultimately successful in 1902. Diller also produced a special quadrangle map of the Crater Lake area published by the Government Printing Office in 1896 that allowed the successful bill to shift park boundaries from the ten townships withdrawn by President Grover Cleveland in 1886 to ones corresponding with the map. The first government-sponsored interpretation of Crater Lake appeared on the map's reverse side.2

Research conducted in support of establishing the park largely consisted of papers published by the Mazamas (a mountaineering group centered in Portland) for the first guidebook to Crater Lake. They appeared in 1897, and included papers by Diller (geology), C. Hart Merriam of the U.S. Biological Survey (mammals), Frederick Coville of the Bureau of Plant Industry (vegetation), and Barton Evermann of the U.S. Fish Commission (potential for sport fishing). Starting in 1898, their corresponding testimonials then became the report from the Department of the Interior on bills aimed at establishing Crater Lake National Park.3

Diller's professional paper on Crater Lake, one that he co-authored with Horace B. Patton in 1902, represented the first monograph to describe the park's geological story and the lake's limnological properties.4 He later condensed the information presented in his monograph for a pamphlet first printed by the government in 1912. Intended as a companion to the 1908 update of the special quadrangle for Crater Lake, Diller aimed the pamphlet as an aid to visitor interpretation.5

With no formal interpretive programs in the park until 1926, these materials virtually stood alone as sources of geological information on Crater Lake. Diller's monopoly on geological work during this period did not extend to vegetation, where John F. Pernot of the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) published a pamphlet on the park's forests with descriptions of each tree species in 1916.6 Like Diller's pamphlet printed four years earlier, Pernot's publication aimed at assisting visitors even though on-site distribution of either piece was virtually non-existent. Contributed work on park-related topics during the first half of the 1920s for the most part consisted of an article on wildflowers and some geological interpretation compiled for another guidebook to Crater Lake, a project undertaken by the Mazamas as something of a reprise to the one of 1897.7

Naturalists and Research, 1927-1952

The hiring of a few seasonal naturalists beginning in 1926 allowed for the possibility of trained personnel conducting research in conjunction with giving talks and contacting visitors. As with external investigations, the studies represented contributed work since the NPS carried no tradition of actually paying for research. Park managers could not muster funds to pay even one permanent full-time naturalist until 1931, so it is not surprising to find only one paper originating from a seasonal naturalist hired for the summer during the first five years of the summer interpretive program.8

Recruitment of university professors and graduate students to serve as ranger naturalists (later known as seasonal interpreters) became more common as a permanent chief naturalist position became an established part of the NPS organizational chart at the park. Publication of results from research studies conducted by the ranger naturalists was encouraged, even though a duty schedule aimed at visitor contact rarely permitted paid time for fieldwork. Most naturalists conducted their studies as part of a degree program or to help bolster chances for academic promotion, with some publications resulting from scholarly pride of scientists who happened to be NPS employees for about 90 days each summer. These naturalist investigators came from fields such as botany (Elmer Applegate, F.L. Wynd), aquatic biology (Arthur Hasler, O.L. Wallis, J. Stanley Brode), geology (John Eliot Allen, Warren D. Smith, Carl Schwartzlow), and zoology (Donald Farner, James Kezer, Ralph Huestis).9 Farner could even claim the distinction of being the lone NPS employee at Crater Lake to have published his findings in book-length form through a university press. This came through an external subsidy so that The Birds of Crater Lake National Park appeared in 1952.10

While much of the published research remained largely inaccessible to visitors, the naturalists regularly produced Nature Notes from Crater Lake for distribution in the park. This publication did not go through the same editorial review process as the academic journals, but the short articles in it were aimed at the general public rather than a small number of scholars. The mimeographed version appeared several times each summer from 1928 to 1938, then started up again as an annual volume beginning in 1946. The series even contained one full monograph, on golden mantled ground squirrels by Huestis, which appeared in 1951.11 With a few notable exceptions, the page count of annual volumes exceeded that of the mimeographed bulletins, partly because formation of the Crater Lake Natural History Association in 1942 eventually led to donations that underwrote conventional printing of Nature Notes. A precedent was set by the late 1940s to encourage submissions through the permanent naturalist allowing ranger naturalists one day per week as project time for the pursuit of research topics in exchange for written contributions.12

Hiring of the first permanent naturalist in 1931 came in direct response to recommendations by a group called the "Committee on Educational Problems in National Parks" sanctioned by the Secretary of the Interior. Chaired by the president of a foundation devoted to scientific research called the Carnegie Institution of Washington (CIW), the group's expenses were funded by a grant from the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial. Each of its members visited a number of parks to assess where educational facilities might be located to best advantage, how many staff members were needed, and where research problems might touch on the visitor experience.13 The chairman, John C. Merriam, took special interest in Crater Lake because of the potential to relate the scientific story of the lake to aesthetic values so as to foster what he called "nature appreciation" in visitors. Merriam believed that understanding how people reacted to natural beauty was a prerequisite before success could be achieved in getting them to truly comprehend the geological story of Mount Mazama.

His ideas about Crater Lake are perhaps best expressed through an essay published in 1933, followed by a section on the park in his book on nature appreciation that appeared a decade later.14 The only other related publications resulted from the efforts of his protégé Doris Payne in 1943-44, though there are also exist a considerable number of unpublished reports and memoranda on interpreting the contrast of spectacular power that produced Crater Lake with the peaceful beauty of its present setting.15 Interest in nature appreciation and aesthetics on the part of Merriam's associates at the University of Oregon also gave rise to a short-lived summer session course cosponsored by the university and the NPS. Poor attendance and logistical problems limited the Crater Lake Field School of Nature Appreciation to the season of 1947.16

Although better interpretation through linking aesthetics with science remained elusive, Merriam succeeded in bringing about a classic study of the park's geological story. It originated when two geologists who worked as ranger naturalists at the park advanced an "explosion" theory to explain the origin of Crater Lake, this being in direct opposition to the "collapse" of the caldera interpreted by Diller. Merriam then placed funds from the CIW for restudying this question in the hands of volcanologist Howel Williams from the University of California.17 Williams, whose earlier work included monographs on Mount Shasta, Lassen Peak, and Mount Theilson, conducted his fieldwork at the park from 1936 to 1940. He essentially supported Diller's interpretation of Crater Lake as a feature of the caldera's collapse, but also expanded upon the earlier USGS work.18

Merriam encouraged Williams to take the unusual step of publishing a popular guide to the geology of Crater Lake through a university press, one that appeared before the technical volume. More than any other single factor, the appearance of Crater Lake: The Story of its Origin in 1941 provided impetus to form the Crater Lake Natural History Association. Superintendent Ernest P. Leavitt and Chief Park Naturalist George Ruhle formally organized the cooperating association in June 1942, though it undertook no business activity until the summer of 1946 due to staff reductions during World War II.19

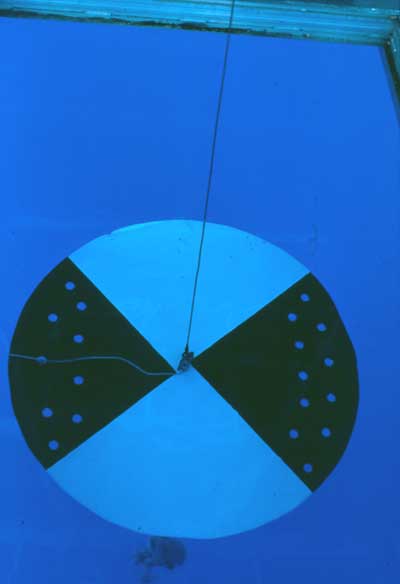

Williams periodically drew on the naturalists for help in the field starting in 1936. Two years later chief naturalist John Doerr began assisting Williams by taking charge of re-sounding Crater Lake for three summers.20 Although the project faced obstacles (the pressure of public contact work by the naturalists and having to rent boats from the concessionaire), Doerr was able to obtain sounding equipment from the USGS.21 These measurements refined those obtained by Diller in 1886, and even helped to lure the first university-sponsored research efforts to Crater Lake. A team of oceanographers from the University of Washington came in the wake of a fledgling limnological program, one outlined by ranger-naturalist Arthur Hasler in 1937 and continued upon his departure by Donald S. Farner. Hasler, later renowned for his work in aquatic ecology and fisheries at the University of Wisconsin, also supplied the basis for later conclusions about a downward trend in the clarity of Crater Lake with his Secchi disk readings that summer.22 The studies initiated by Hasler and Farner centered on fish, but in July 1940 the UW investigators expanded the breadth of study by measuring vertical penetration of bands in the visible light spectrum and took water samples to examine the quantity and kinds of phytoplankton present in the lake.23

Merriam previously solicited a report on Crater Lake's optical properties, one to serve as the basis for interpreting to visitors how the lake appears as blue. He recruited an astronomer who worked for the CIW at the Mount Wilson Observatory for the work. Edison Pettit's report was thus subsequently distilled into a CIW news bulletin for mass distribution. It prefaced explanation of "Why is Crater Lake So Blue?" with citations from Merriam's essay of 1933 in order to tie the physics of scattered light to why the lake held such great appeal for visitors.24

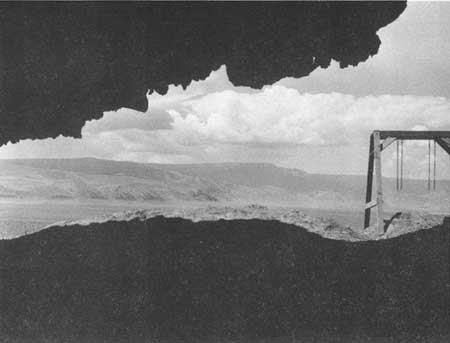

The centerpiece of what Merriam orchestrated at Crater Lake, however, lay in Williams' geological study, one funded to allow for collaboration with related investigations. Most prominent among the cross-disciplinary work involving Crater Lake were the archeological investigations of Luther S. Cressman, who excavated caves east and north of the park beginning in 1935. Cressman related the formation of Crater Lake as a time marker to prehistory in the northern Great Basin and, like Williams, published both technical monographs and a popular account.25 Merriam orchestrated funding for much of Cressman's work in the late 1930s, partly in hopes that it could assist with tying Crater Lake to a larger regional study of change in recent geological time. The CIW also funded studies by Henry P. Hansen on forest succession within the past 10,000 years through pollen analysis at various localities in south central Oregon.26

As a catalyst for the interpretive program at Crater Lake, Merriam viewed research not merely as a means to protect national parks. He saw the main purpose of the NPS as educating visitors, with research as the way to deepen the understanding and enhance the credibility of the naturalists. By 1944 he found himself in disagreement with the director (his long-time associate in the Save-the-Redwoods League, Newton B. Drury) over the idea that scientific research had a place in the NPS. Drury's objections stemmed not so much from hostility to science, but from the reality of running a bureau whose tiny infrastructure for support of research had been gutted prior to his appointment in 1940. The soft money supporting staff positions in biology, forestry, and geology during the work relief programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps almost vanished after 1938, with all but three NPS biologists transferred to the U.S. Biological Survey in 1939.27

While the NPS slowly recovered from the deep cuts in staffing taken during war years, the agency continued to encourage (rather than fund) research. Naturalists, as they had prior to World War II, conducted studies on a part-time basis for small rewards at places like Crater Lake. Many of them, as Merriam observed in 1944, lacked training to conduct the critical studies to serve as the basis for an interpretive program.28 For more than a decade after 1945, the naturalists nevertheless continued to supply the bulk of what little research output the NPS could claim to have fostered.

Science on a Shoestring, 1953-1973

Increased federal funding for scientific research beginning in the mid-1950s profoundly influenced the number and scale of studies throughout the United States. Crater Lake and other national parks began to receive increased attention from university-affiliated scientists who could tap grants from the National Science Foundation or other newly created funding sources. Naturalists served as the primary points of contact with outside researchers, though the NPS could do little in the way of providing direct financial support or equipment for these studies.

Just as they had before the war, some of the naturalists continued to work on Crater Lake. A couple of short reports and several articles in the annual volumes of Nature Notes summarized these activities. Assistant (later Chief) Park Naturalist C. Warren Fairbanks and ranger naturalist John Rowley also contributed to the published literature on diatoms in Crater Lake.29 Despite Fairbanks' resignation in 1958 and the departure of Rowley after the 1955 season, investigations on Crater Lake subsequently became more ambitious. The budget for scientific research for the entire national park system totaled only $28,000 that year, but NPS acquisition of a launch and a skiff at Crater Lake allowed for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey to produce a bathymetric map. By employing echo-sounding technology, the Coast and Geodetic Survey obtained 4,000 individual depth measurements on the lake over a period of six weeks in 1959.30 A new bathymetric chart (one that showed the lake floor contours in much greater detail than previously) was eventually interpreted by three short papers generated by scientists outside of the NPS, including one by Howel Williams who memorialized Merriam in naming a newly discovered underwater cinder cone.31

The bathymetric work allowed a new ranger naturalist, C.H. "Hans" Nelson, to begin the first study on sediments in Crater Lake. It was something intended to be the cornerstone of his master's thesis, and eventually resulted in Nelson's first scientific publication.32 Chief Park Naturalist Bruce Black recognized the potential significance of the project, and so made the somewhat unusual allowance for Nelson to have two duty days per week away from public contact work in order do his fieldwork.33 The occupational makeup of the naturalists had, by this time, shifted away from a seasonal staff dominated by college professors to one composed of graduate students, one or two faculty members, and several high school teachers.34

A research orientation (thought by Black to be fairly unusual in most national parks of the period) persisted among the naturalists at Crater Lake into the 1960s. While Black cooperated with researchers where he could, his one-time assistant Dick Brown became the leading promoter of scientific study at the park. Brown arrived as a seasonal in 1952, and then became the permanent Assistant Park Naturalist just a year later. After leaving Crater Lake in 1960, he returned as the Chief Park Naturalist once Black departed in 1963. A vascular plant taxonomist by training, Brown provided specialized assistance to the seasonal staff members such as Elizabeth Mueller, who undertook a thesis on the ecology of the Pumice Desert.35 He also made a point of hiring one or two professors each summer. This provided the NPS with some employees who had experience in front of groups and the possibility of obtaining studies at bargain prices.36 Dwayne Curtis of Chico State College, for example, produced two short pieces on discoveries made about the park's nonvascular plants, while Marion Jackson of Indiana State University co-authored a classic ecological study of Wizard Island.37

Brown's acceptance of a new position in 1967, that of research biologist, formalized his role as broker for studies at the park. His goals supposedly differed than those of being chief naturalist since the focus of the previous job was visitor contact rather than supplying the basis for which to manage resources. In practice, however, funding for the NPS science program of the time rarely allowed him much more than continuing the studies begun when he was chief naturalist, or as he put it, "conning people to do things for the park for next to nothing."38 Brown could devote more time to coordinating research efforts fortuitously funded by other government agencies or universities through grant programs. His ability to actively assist researchers, however, decreased the further away a project moved from his interests in botany, zoology, or forestry. He actively supported geological and limnological studies, but could provide little more than some limited logistical support for them.39

Many of the problems plaguing Brown's effectiveness as a research biologist were similar to those experienced by others holding similar positions in the NPS at that time.40 In addition to possessing limited ability to influence funding decisions, Brown and other research biologists had an administrative supervisor (the park superintendent) and a research supervisor (regional biologist), an arrangement that led to "all kinds of conflicts."41 Brown transferred to Point Reyes National Seashore in 1970, in part due to the difficulties imposed by two supervisors, and was succeeded by James Blaisdell, a biologist from the Western Regional Office in San Francisco.

Blaisdell worked from the Klamath Falls Group Office, established by Superintendent Donald Spalding and approved by NPS Director George Hartzog in 1969 to serve Crater Lake, Lava Beds, and Oregon Caves. The new location allowed Blaisdell to participate in an ambitious big horn sheep restoration project at Lava Beds National Monument, something which got underway in 1971 and resulted in one publication aimed at interpreting a resource management (rather than research) effort.42 NPS-sponsored research, especially in biology, rarely went to press; it instead aimed at a final report, and left implementation to park operations. Scientists based in regional offices or in Washington provided review of the findings, and the research process generally concluded with the report's release.43 For Crater Lake in the early 1970s, NPS-sponsored research resulted in just two reports. One came about as the park finally moved to close the last open garbage dump in 1972, mostly to reduce the dependence of bears on this source of food.44 The other centered on elk in order to determine relative numbers and their distribution, its purpose being to provide the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife with data so that better projections of an elk "harvest" could be made outside the park.45

Substituting a research biologist (whether stationed at Crater Lake or Klamath Falls) for the chief park naturalist as coordinator for scientific studies had little effect on limnological or hydrological investigations conducted in the park. Any research effort in either field was almost entirely dependent on outside funding and expertise. The NPS, through a long-range aquatic resources management plan approved in 1969, articulated some fairly general research needs: 1) describe fully the stream and lake ecosystems; 2) determine the extent of human influence on the aquatic resources, especially in regard to Crater Lake and fishing on Sun Creek; 3) determine the feasibility of eradicating all fish from Crater Lake and exotic fishes from park streams.46

These needs, of course, were secondary concerns to those conducting research from outside the NPS. Most of the USGS work, for example, related to water supply needs of the region.47 The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) underwrote several studies starting in 1967 that centered on whether nuclear fallout deposited uniformly on land or sea. Scientists considered Crater Lake as the perfect study site to obtain measurements of radioisotopes associated with nuclear weapons testing since the complexities of circulation and currents in ocean waters led to conflicting interpretations of the data.48 Concurrent with the AEC work were studies funded by grants from the National Science Foundation and other sources on optical properties of the lake, culminating with one that compared Crater Lake with Lake Tahoe.49 The NPS could be credited with some logistical support in all of these research efforts, but its contribution did not include funding. The agency simply encouraged, and in some cases promoted, scientific study in line with its policy.50

NPS policy in the late 1960s also voiced the need for a mix of basic and applied science, something it dubbed "mission-oriented research." This work, presumably to be funded by the agency, was aimed at assisting the process of internal decision making. Irrespective of needs expressed in the park's long-range aquatic resources management plan, the NPS limited its staff and funds to a precious few studies related to terrestrial biology. This course reflected the existing expertise in the agency to some extent, though the policy allowed for enlisting universities and other independent scientific entities in the same way Merriam orchestrated studies at Crater Lake during the 1930s.51 Chronic shortages of even minimal funding, however, became the main obstacle to sustaining the NPS science program of the 1960s and 70s. It was thus an almost foregone conclusion that a limnology program for Crater Lake initiated by Oregon State University (OSU) professor John R. "Jack" Donaldson would quickly grind to a halt.

Donaldson launched the limnology program in the summer of 1967, but had to borrow a boat and motor from a colleague at OSU.52 The program, as such, was entirely dependent on a grant from a short-lived bureau in the Department of the Interior, the Office of Water Resources, whose focus in funding research at that time included studies of eutrophic (nutrient-rich) lakes. Donaldson's grant was funneled to the Water Resources Institute at OSU, which then made funds available to study Crater Lake as a baseline (it being classed as oligotrophic, or nutrient-poor) for studying the process and impacts of nutrient enrichment.53 Although meager, the grant allowed Donaldson to work on the lake with three graduate students: Owen Hoffman, Douglas Larson, and James Malick. Their work resulted in two master's theses, one doctoral dissertation, and several journal articles before Donaldson's funding disappeared in 1970.54 The borrowed boat remained at the park long enough to assist three OSU oceanographers interested in the lake's thermal properties. Funded by a grant from the Office of Naval Research, their work began in 1969 and eventually included the first research ever conducted on the lake during winter.55 The latter took place in February 1971 after four previous attempts.56

Naturalists, now called interpreters, were no longer involved with research by the early 1970s due to several factors. Probably the most critical stemmed from NPS reorganization of the time that led to a merger with the ranger division while also reducing the number of permanent employees at Crater Lake with an interpretive function to one technician.57 The educational program was now lodged in the park's organization chart under "Interpretation and Resource Management," a misnomer that resulted from trying to disguise the contraction in NPS staffing during the Vietnam War era.58 Visitor programs persisted throughout the summer season due to seasonal staffing, but interpretation's traditional link with research (especially that conducted on the lake) was almost severed from 1971 to 1978. When limnological studies at Crater Lake finally resumed after this hiatus lasting seven years, they came about due to the interest of an outside researcher, not because interpretation's status as a separate division in the park had been restored.

Attempts at Linking Resource Management with Research, 1974-1983

The NPS found a new way to obtain scientific studies with the advent of cooperative park studies units (CPSUs). Although a CPSU had been established at the University of Washington (UW) as early as 1970, studies at Crater Lake through this conduit were not initiated until a CPSU came into existence at Oregon State University in 1974. Over the following decade this CPSU acted as something of a broker, one that sometimes induced graduate students to do their theses work at the park. Paid staff at the CPSU in Corvallis during the first fiscal year of operation consisted of NPS research biologist Edward E. Starkey (who served as coordinator at first, then became project leader in later years), one secretary, and a technician. The "research assistants" often pursued their thesis work with a small stipend in exchange for progress reports.59 Where a proposed thesis study generated sufficient interest from park management, a contract to produce a separate report might then be offered to a student through the CPSU.60

Situated within the School of Forestry at OSU, the CPSU remained elastic enough to provide some funding for fieldwork at Crater Lake and other parks while occasionally utilizing the expertise of USFS scientists like Jerry Franklin or faculty members outside forestry such as geographer James Lahey.61 It accommodated Starkey's research interests (which lay mostly in Olympic and Mount Rainier national parks) while expanding staff to include sociologist Donald R. Field and writer-editor Jean Matthews by the end of 1983.62 As the CPSU in Corvallis seemed to widen the scope of its activities, support for thesis projects began to dissipate in favor of funding for studies led by collaborators holding academic appointments at OSU.63 This shift in the early 1980s was repeated at other CPSUs, but the resource management priorities at Crater Lake dictated that the NPS continue with seeking research conducted by graduate students.

Prescribed fire dominated NPS resource management efforts at Crater Lake in the late 1970s, but the program had its roots earlier in the decade when Robert "Bob" Martin and Dave Frewing from the USFS silviculture laboratory in Bend identified a need for fire history information.64 They piqued the interest of Donald B. Zobel from the Department of Botany, who then served as major advisor to a pair of graduate conducting studies of forest types in the park with funding provided by the NPS through CPSU contracts. One of the graduate students pointed to how the reintroduction of fire might perpetuate ponderosa pine and sugar pine in the "panhandle" portion of the park, thus leading directly to management-ignited burns which began in 1976.65

Superintendent Frank Betts banned such burns in the park the following year due to severe drought conditions while park staff completed a fire management plan. With a plan in place for 1978, NPS crews conducted a management-ignited burn of more than 3,000 acres in the northeast corner of the park that fall. They also allowed six lightning-caused fires to burn over 540 acres in the summer, marking the debut of prescribed natural fire among units of the National Park System located in the Pacific Northwest.66 Although formerly something of a backwater for the practice of forestry in the national parks, Crater Lake possessed the combination of aggressive leadership in fire management and a few ongoing studies whose scope went well beyond the mixed conifer stands dominating the panhandle.67 Lodgepole pine forests in the park were the subject of another thesis completed at OSU in 1978, while another investigator affiliated with the University of Idaho conducted studies on how the burns of 1976 and 1978 affected the dynamics of vegetation change.68 Control of fire effects research at Crater Lake eventually passed to James K. Agee, a research biologist stationed at UW. He initiated three studies through the CPSU in Seattle in 1980, resulting in several subsequent reports completed through contracts.69

Fire management was also destined to be virtually the only area where research played a role in the planning process at Crater Lake during the 1970s. Even then, it simply featured as citations at the back of documentation prepared for compliance purposes in 1976 and 1977.70

The park's first general management plan (GMP), meanwhile, proceeded toward approval by Regional Director Russell Dickenson in December 1977 by borrowing heavily from previous master plan drafts which emphasized the need for improved facilities at Rim Village and other developed areas in the park. With the planning process well underway by the time two contracted CPSU studies on visitor use were begun in the summer of 1977, it is perhaps understandable why the GMP glossed over their findings. One of the studies focused on social impacts of design changes at Rim Village and on Rim Drive, while the other contained the modifications needed in park facilities to allow for handicapped accessibility.71

If research seemed largely disconnected from park planning of the time, its linkage with operations other than fire management remained weak ever since Dick Brown left Crater Lake in 1970. Funding for a "resource management specialist" at the park somewhat improved the situation, and came about when Blaisdell accepted a transfer from the group office in Klamath Falls. Mark Forbes filled the new position, one aimed at better coordination of resource management projects in the park and improved logistical support for scientific investigation. Resource management specialists promoted studies like the biologists had, but did not delve into research design nor provide peer review of methods and findings. They instead provided more focus on legislative compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 and served to centralize the resource management function, rather than it being divided among park rangers as a collateral duty to law enforcement."72

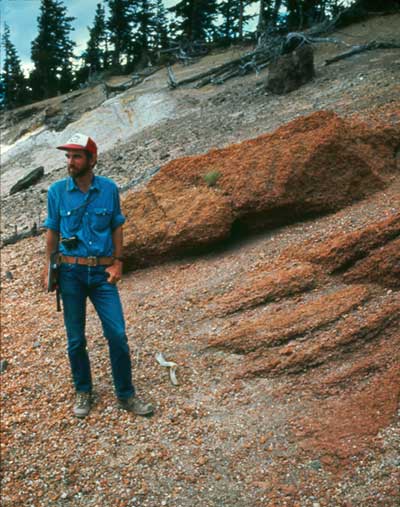

Forbes arrived at Crater Lake in 1978 and then served as the first point of contact with outside researchers. He took a lead role, for example, in coordinating the logistical aspects of two USGS studies on Crater Lake that began in 1979. Both projects eventually provided dramatic reinterpretations of previous work, with one building on a previous temperature study by oceanographers at OSU in order to emphasize the importance of hydrothermal processes in Crater Lake.73 The other started by mapping the caldera walls, an endeavor that resulted in discovery of the only known pair of nesting peregrine falcons in Oregon at that time. Park personnel subsequently cooperated with the state game department and other partners in a recovery program.74

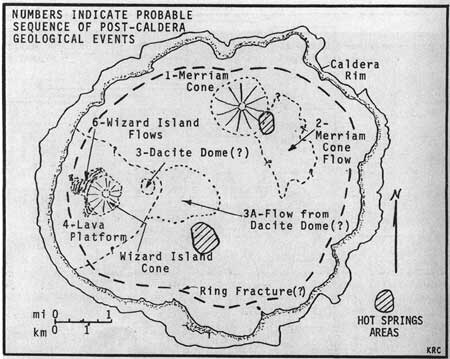

The mapping and other components of a study by Charles R. Bacon gave the NPS far more than merely triggering an effort to insure the continued presence of an endangered bird. His first publication focusing on the park appeared in 1983 and represented the first significant revision of the study by Howel Williams that had stood virtually unmodified for four decades.75 Bacon's paper directly influenced many of the interpretive programs given by park staff (given its direct connection to the primary interpretive theme at Crater Lake), something nicely coincident with USGS funding aimed at analyzing Mount Mazama's geothermal system and assessing associated volcanic hazards. Although Bacon had a technical emphasis, he gave occasional training talks for park staff and assisted a seasonal interpreter who revised his guide to the park's geological story accordingly.76

Resumption of limnological studies on Crater Lake more or less coincided with the return of USGS scientists, but remained a volunteer effort for several years. The First Conference on Scientific Research in the National Parks preceded it, where Owen Hoffman (formerly one of Donaldson's students, but now an environmental scientist) trumpeted how the lake made an ideal benchmark for future research in limnology. He made a compelling point at the conference held in 1976 about how little emphasis the NPS had placed on studying lakes anywhere in the National Park System, yet also identified a number of "mission oriented" questions that could be addressed through a monitoring program on Crater Lake.77 Hoffman was not positioned to spur action by the NPS, so the matter of a monitoring program dropped until Douglas W. Larson (another of Donaldson's former students) returned to Crater Lake in 1978 after an absence of eight years. Larson collected data for four summers with some assistance from seasonal interpreters who also volunteered their time in an effort to establish a baseline for future comparisons.78

Papers from Larson's initial efforts focused on the differences from previous surveys of phytoplankton and an apparent decline in optical properties, but he refrained from speculating publicly as to the causes for these changes.79 Larson discussed his suspicions about an anthropogenic cause of elevated nitrate levels at one inner caldera spring with Forbes and Superintendent James S. Rouse as early as September 1978, but Rouse dismissed the possibility. The superintendent finally came around to endorsing the need for a monitoring program, but this came only after Larson's recommendation in 1980 for such a program "to head off possible irreversible lake degradation."80 Rouse had Forbes draft a funding request aimed at establishing a monitoring program in the spring of 1981, something estimated to cost $13,500 as start up and $4,500 on an annual basis.81 Revising the cost estimates for monitoring upward to more realistic figures that fall brought the request no closer to funding until Larson's annual report to the NPS for 1981 somehow reached congressional staff in Washington.82 A portion of the report discussed a continued decline in clarity from what it had been prior to 1970 and linked the drop to nutrient enrichment, a situation that demanded study as to whether this was linked to human activity (such as sewage) or other causes.83

Legislation mandating a monitoring program initially came through Denny Smith, a congressman from Oregon who entered the House of Representatives in January 1981. Smith sat on the House Committee for Interior and Insular Affairs, and was thus situated to offer an amendment to legislation aimed at correcting the inadvertent inclusion of a timber sale on national forest land when Congress voted to expand the park in 1980.84 The congressman acted on the basis of one conversation between his legislative director and Rouse just a few days earlier. This amendment to the bill aimed at deleting the timber sale directed the Secretary of the Interior to instigate studies "as to the status and trends of change in the water quality of Crater Lake."85 These investigations were to last for a period of ten years and allow for the application of findings in much the same fashion that other federal agencies at that time received prescribed direction to link basic and applied research in order to address certain land management problems.86 Smith introduced the amendment on December 10, 1981, stating in his explanation that the NPS "has developed an initial research program to address this concern [of diminished clarity] and should be prepared to move ahead promptly."87

Conference on the amended bill was not scheduled until midway through 1982, but the likelihood of passage made the NPS regional office in Seattle take notice. After briefing Regional Director Daniel Tobin on January 8, Regional Chief Scientist James W. Larson set up a research planning meeting in Corvallis for later that month.88 Formulation of some objectives prior to the meeting helped interested scientists and NPS staff members generate a list of alternative hypotheses to address recorded changes in the lake's clarity before providing specific recommendations. The latter included urging the NPS to conduct and coordinate a long-term monitoring program, followed by one that highlighted the need for a limnologist to run it.89

As much as the prospect of such a program represented a great leap forward, Smith's bill said nothing about putting any new money toward monitoring Crater Lake, so one of the stated objectives at the meeting in Corvallis involved identifying low cost tasks to address specific needs. The regional office in Seattle, largely through the efforts of James Larson and his assistant Shirley Clark, pieced together $30,000 to start the program in 1982. This amount allowed the NPS to reimburse the Army Corps of Engineers for ten percent of Douglas Larson's time and allowed Larson, a limnologist with the Corps, to set up a laboratory, buy equipment, go to meetings, and train NPS personnel.90

The legislation mandating study of Crater Lake became law on September 15, 1982, roughly one week after the final sampling day for the year.91 Monitoring could be described as a shoestring operation, but served the purpose of demonstrating to Congress that the NPS had begun a program in advance of prescribed direction.92 The program consisted of a seasonal biotech, Mike Gillmore, and Douglas Larson, whose responsibility as investigator included writing an annual report. This document became the basis for comment by members of a peer review committee, a body initially convened in February 1983 at OSU.93 Although respondents represented a number of academic institutions, Larson received the most substantial comments from a group of scientists at the University of California, Davis. They represented the research group that studied the limnology of Lake Tahoe for two decades and pointed to the need for an investigation of nutrient enrichment among their eleven recommendations, urging that the NPS fund such work during the coming summer.94

As Larson pointed out in the report's recommendation section, monitoring per se is not research, but instead a mechanical process of data collection for future interpretation and possible determination of causal relationships. He urged the launch of an initial research project "to determine the cause or source of reported deterioration of Crater Lake's optical transparency."95 The project, as envisioned through a work plan prepared by Larson in July 1983, consisted of several studies to be conducted in conjunction with the established protocols for monitoring.96 Larson identified a potential source for the deterioration, in that some springs within the caldera below Rim Village contained high nutrient concentrations suggestive of a possible link with sewage influx. He and Clifford Dahm at OSU cautioned, however, that further investigation was needed to conclusively evaluate hypothesized linkages between enriched spring water going into the lake and the dynamics of algae affecting clarity.97

Jack Dymond and Robert Collier, two oceanographers at OSU, widened the range of possible explanations for the apparent decline in the lake's clarity by using sediment traps to measure the flux and composition of particles falling through the water column of Crater Lake. Initiated independently of the park program coordinated by Larson, the work by Dymond and Collier introduced the possibility that trace metals such as zinc and iron could be limiting the lake's biological productivity. They also suggested that hydrothermal springs located on the bottom of Crater Lake might contribute to the particle flux (this reflects outside inputs of nutrients and inorganic particles) and perhaps cause turbidity in deep water.98

Even if other funding sources absorbed much of the costs associated with the two examinations conducted on Crater Lake by Dymond and Collier in 1983, the NPS needed to increase its budget for its monitoring infrastructure. Roughly $160,000 became available (compared with only $30,000 the previous year) to purchase equipment (this included a boat for winter sampling, a floating boathouse, and a water quality laboratory located at Park Headquarters) and pay for contracted work. The funds also provided two new biotechnician positions, one as a seasonal and the other as permanent, in line with recommendations made in the annual report on the program for 1982.99

This quadrupling of the lake monitoring budget largely came through the Natural Resources Preservation Program (NRPP), a competitive funding source established by the NPS in the early 1980s to address high-profile issues in the parks. NRPP came as part of the agency's response to criticism initially leveled by the National Parks and Conservation Association that existing natural resource management capability of the NPS could not deal with a rising number of external threats. A new training program that began in September 1982 represented another part of this response, one where employees aiming for careers in natural resource management divided their time between off-site coursework and regular duties in parks for a period of two years. Jonathon B. "Jon" Jarvis came to Crater Lake to participate in the program and joined Forbes as a resource management specialist, just as the park received the NRPP funding to monitor the lake. As far as officials in the regional office were concerned, such a boost in budget and staffing could be justified by Crater Lake serving as an example of how the NPS was working to meet a legislative mandate. It also helped to show what the agency could do in light of criticism that very few parks possessed baseline information needed to identify incremental change possibly affecting the integrity of natural resources.100

From an operational standpoint, this buildup in the park's infrastructure came not only in response to an expanded summer monitoring program, but also in anticipation of the first winter sampling trip sponsored by the NPS. Set for January or February 1984, the operation would involve lowering personnel and equipment down a snow chute near the Crater Lake Lodge to an all-weather dock and boathouse, where researchers could launch a boat and "set course for a quick trip to the sampling location."101 This prospect vanished in a windstorm that raged from November 7 to 11, 1983, an event which damaged the winter boat, destroyed the boathouse, and sank the vessel used for summer sampling.102

Expanded Limnological and Geological Studies, 1984-2002

The ravages of that November windstorm were not a major setback to plans for winter sampling, but they did delay the trip until March 1986. Several changes took place in the mean time that profoundly affected the limnological program's focus and appearance. Monitoring continued during the summer of 1984 with approximately the same funding level as the previous year, once another peer review session conducted in November 1983 found existing protocols defensible and well-structured. When it came time to hire a full-time principal investigator, however, NPS officials passed over Douglas Larson in favor of Gary Larson, an aquatic ecologist already working for the agency as regional chief scientist at the Midwest office in Omaha.103

Gary Larson's appointment at the CPSU in Corvallis became official in September 1984. It came less than six months after a new superintendent, Robert E. Benton, arrived at the park.104 Benton magnified his predecessor's uneasiness with the suggestion by Douglas Larson that sewage or elevated nitrate levels from one inner caldera spring might have a role in Crater Lake's perceived decline in clarity.105 He noted in the superintendent's annual report for 1984 that hiring Gary Larson constituted "perhaps the greatest improvement during the year in the lake research program," while the discovery of some new historical data might dispute "the early conclusions that the lake clarity has diminished."106

At an organizational meeting held near the end of October, Gary Larson said that the lake program should concentrate on "loss of clarity" rather than more tangential "interesting projects."107 He recommended the monitoring program continue in a form similar to previous practice, but with certain additions. These included studying atmospheric chemistry, zooplankton, fish, and the lake's paleolimnology. The latter project was enticing since it held the potential to provide evidence of how biological conditions had changed through time, but did not receive the necessary additional funding.108

Larson did, however, hire the first two graduate students funded specifically by the NPS to conduct research on the lake. Elena Karnaugh completed her masters thesis in 1988 on the structure, abundance, and distribution of pelagic zooplankton populations, and Mark Buktenica completed his masters thesis in 1989 on the ecology of kokanee salmon and rainbow trout in the lake, with reference to their long-term impact to the ecosystem. Buktenica later became an aquatic ecologist in charge of coordinating the monitoring program on Crater Lake. Although he did not hold a research appointment, Buktenica was the first park employee with a position description that included conducting independent scientific research. Work by Buktenica eventually included sole or joint authorship of papers on fish ecology, benthic biological communities, zooplankton, lake morphology, bull trout restoration, water clarity, and submersible studies.

A peer panel convened in April 1985 supported the recommendations of the new principal investigator, though one committee member remarked

"objectives of the (limnological) program are broader than just monitoring optical properties...it is apparent that the Park Service is also able to support a variety of limnological studies within the program, as long as such studies are potentially related to management goals."109

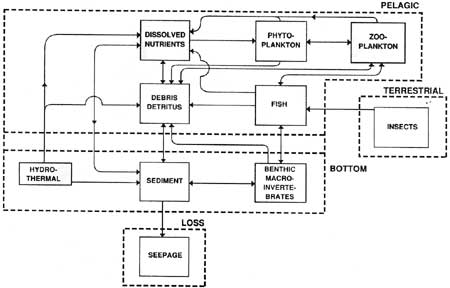

Another respondent, Jack Dymond, advanced his mass balance modeling approach to studying the lake as a way of defining specific goals from what he called "very general objectives" of the mandated ten year study.110 For his part, Gary Larson saw the monitoring program as essentially "in place." With clarity readings of early July 1985 for Crater Lake being a cause for optimism (one of 37.1 meters was exceptional and seemed to contradict fears of steady downward spiral), the monitoring program's direction could shift toward the "interrelationships among environmental, terrestrial, cultural, and aquatic aspects of the (lake) ecosystem." Larson also developed a conceptual model from which specific research objectives were established and areas needed additional study identified.111

With sampling periods extended to March and May in 1986, adding to the data collected during the summer season, Gary Larson ventured a tentative explanation of Crater Lake's clarity in his annual report. The apparent decline in readings during August, he surmised, could probably be explained by "small increases in the densities of light scattering particles in the water column."112 Larson went on to state that particle density is affected by natural environmental factors, loading of anthropogenic material from atmospheric and on-site sources, and perhaps internal lake processes such as hydrothermal vents and biological activity. If nothing else, one of two special studies conducted that summer (one aimed at replicating Pettit's work, but with new technology) found that the color of Crater Lake had changed little over the past half century, though month to month variation could be substantial.113

Results from the other special study of 1986 helped push clarity away from central position as the focus of the limnological program, at least in the short term. Work by Dymond and Collier over three summers found that approximately 95 percent of total productivity in the lake's euphotic zone (that part of Crater Lake where light penetrates) was derived from recycled nutrients rather than input of new nutrients from the atmosphere or point sources. They also studied deep lake waters and found evidence of hydrothermal venting, leading them to propose a four-year program, one aimed at evaluating the influence of hydrothermal systems on Crater Lake's composition and ecology. It involved instruments towed from boats, a remotely operated vehicle sent to the bottom and even manned submersibles to precisely locate and sample the vents.114

The fact that Dymond and Collier believed such work to be feasible could be attributed, at least in part, to what the NPS had achieved in the enhancement of its support for the limnological program. Not only had the agency sought to bring additional staff and funding to Crater Lake, but it also handled complex logistics needed for conditions that resembled what scientists often encountered on the ocean. It supplied a laboratory at Park Headquarters to process water samples and made replacement of the boat house on Wizard Island a top priority so that a new one could be completed during the summer of 1985.115

An impetus for more funding to support the study of the lake's hydrothermal processes came in the form of legislation passed late in 1986 which instructed the Secretary of the Interior to publish a proposed list of significant thermal features within selected units of the National Park System. The NPS included hydrothermal vents on the floor of Crater Lake in its list published on February 13, 1987. Crater Lake was nevertheless dropped from the final list transmitted by the Department on June 30 due to "insufficient information," with any determination of significance deferred, pending additional research and review.116 Passage of amendments to the Geothermal Steam Act in September 1988 superceded the earlier legislation and directed the Secretary to report on the presence or absence of significant thermal features at Crater Lake (among other national parks) within six months of becoming law.117

As wording in the House Report on the amendments explained, the legislation passed in 1986 sought to address "a long standing concern with potential geothermal development activities near certain units of the National Park System."118 In the case of Crater Lake, the concern arose when geothermal leases were awarded on the adjacent Winema National Forest in 1984.119 California Energy Company of Santa Rosa subsequently gained approval through the Bureau of Land Management's environmental assessment process to drill four test wells within five miles of the park boundary.120 Drilling began in September 1986 near Mount Scott and the "panhandle" as part of the company's search for hot water that could be further developed as an energy source.121 For the moment NPS officials did not publicly express their anxiety about future geothermal development and its impact, though Benton certainly had his suspicions about the company's request to amend the environmental assessment.122

Cal Energy called for a meeting hosted by the Geothermal Resource Council once it learned that the NPS intended to recommend Crater Lake be added to the list of significant thermal features mandated by P.L. 99-591. Two days of discussions in late February 1987 failed to produce anything other than some lively debate about whether Crater Lake merited a place on the list.123 The NPS and BLM remained on opposite sides two months later as the question went to the Secretary of the Interior's office for resolution.124

Crater Lake remained off the list of significant thermal features, at least for the time being, pending some resolution of the hydrothermal question. BLM meanwhile approved a revised environmental assessment allowing continued geothermal exploration under relaxed procedures for drilling, though two conservation groups quickly filed appeals.125 Dymond entered the fray over drilling as he and Collier began their work on Crater Lake in August 1987. He cautioned that "any drilling or activity around [park] boundaries may upset the ecology of the lake."126 After 20 days on the lake with instruments such as a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) which took the first video images of the lake floor, Dymond and Collier felt they had demonstrated the presence of thermal waters in the south basin. The draft report, however, qualified this position with a statement about how the exact location and characteristics of the [hydrothermal] inputs were still unknown, though they "significantly narrowed down the target for the proposed submersible work."127

USGS personnel provided initial review of the draft report and supported the need for a submersible since only the collection of additional data could provide unequivocal proof of whether hydrothermal vents existed. This meant obtaining fluid samples and temperatures form several of the vents observed by the ROV. Officials in the Department of the Interior therefore recommended that the Secretary not revise the list of parks containing significant thermal features until a manned submersible could gather affirmative evidence from the vents. They also wanted the existing moratorium on new leasing in the area around Crater Lake left in place for another year.128 A member of the Oregon congressional delegation, Senator Mark Hatfield, then attempted to preempt any deferment by introducing a bill in January 1988 aimed at placing Crater Lake on the list. He did so in the aftermath of Dymond and Collier having presented findings in their draft report at a national scientific meeting.129

With Hatfield's provisions for Crater Lake incorporated as part of Senate amendments to the Geothermal Steam Act, this piece of legislation went to the House Committee for Interior and Insular Affairs. The Crater Lake language faced opposition from one committee member who attempted to insert a provision allowing the Secretary to remove parks from the list if conclusive evidence showed that no thermal feature could be harmed by leasing. Legislators instead crafted a compromise that kept Crater Lake on the list, but required the Secretary to report to Congress within six months of passage as to whether or not thermal features actually existed on the lake floor.130 The clock began for such a report when S. 1889 became law as P.L. 100-443 on September 13, 1988.131

It quickly became evident, however, that even peer review of the research conducted during the 1988 season could not be conducted during the six months prescribed by legislation.132 Charles Goldman of the Tahoe Research Group at the University of California, Davis, chaired the peer panel on May 2, 1989. He and other members of the panel were charged with evaluating extant data and examine the hydrothermal program as part of focusing the latter on providing "more evidence for both scientists and decision makers on the geothermal heating question."133 The panel demurred on the question of whether hydrothermal vents in the floor of Crater Lake were significant by accepting Dymond and Collier's plan for another field season, one aimed at completing a final report by June 30, 1990. The deadline was then extended to late summer 1991 once the NPS submitted an interim report to Congress.134

No immediate answer concerning the vents could be made because none of the eleven dives made with the manned submersible in the south basin study area during August 1988 could find hydrothermal features other than several "bacterial mats" with water temperatures too low to qualify as thermal features.135 The major goal of the hydrothermal program, however, was "to evaluate the environmental significance of hydrothermal activity in the lake as part of an overall ecological model of the lake." This meant that the grand total of twenty-one manned submersible dives during August 1988 served a variety of purposes, among them the collection of rock samples during the four dives underwritten by the USGS.136 Despite the breadth of goals for the submersible work, finding the vents became even more of a focus for the NPS in light of the Interior Board of Land Appeals rejection in early 1989 of a motion to stop the drilling filed by several conservation groups.137 Drilling by Cal Energy resumed on July 3, 1989, one month prior to the submersible's return to Crater Lake.138

The NPS readied itself to capitalize on the publicity expected when the dives started on August 5 by formulating a media plan and several advance press releases.139 Five days later, during the fourth dive, Dymond found a "blue pool" near the bacteria mats. He dubbed the kidney shaped pool, one whose aqua blue color reminded scientists of a miniature Crater Lake, "Llao's Bathtub." This discovery, which press accounts immediately linked to hydrothermal vents, was followed by announcement of a new species of mite found on some rock samples taken from the bottom of Crater Lake.140 Vents or springs hot enough to qualify as significant thermal features remained elusive over the following week, though scientists hoisted samples of pitch black, granular mud from a blue pool.141 Collier then piloted the submersible to a bacterial mat on August 19 and obtained a temperature several degrees warmer than the difference of ten degrees Celsius (between the thermal feature and surrounding water) needed to show significance. An even hotter temperature of 18.9 degrees Celsius was measured at another mat three days later, to the delight of park staff.142

Collier cautioned that temperatures represented only one factor in substantiating the existence of hydrothermal input to Crater Lake, and pointed to a number of data sets produced from the dives that still had to be analyzed and evaluated over the coming year. Cal Energy, on the other hand, responded to the temperatures found in the bacterial mats with a press release of its own. The company attempted to cast doubt on whether the evidence was conclusive, since no one had observed any flow of water in association with the bacterial mats.143 It seemed a half-hearted effort at best, because drilling east of Mount Scott found temperatures of only 265 degrees Fahrenheit when Cal Energy officials had hoped for ones around 450 degrees.144 Test drilling outside the park continued in 1990, but continued to produce lower than expected temperatures.145

Any further drilling near the park became virtually moot in February 1991, when BLM suspended the leases held by Cal Energy for two years.146 The company responded by announcing layoffs in its Portland office, though a spokesman for Cal Energy maintained for several weeks that they "had no intention" of backing away from projects in the Pacific Northwest.147 Although Cal Energy eventually announced plans for a geothermal power plant on the flanks of Newberry Crater near La Pine in September, they simultaneously agreed to plug their test wells east of Crater Lake.148 With their terms set to expire, Cal Energy formally relinquished leases near the park in February 1994, roughly a year after another spokesman admitted that the company had made a mistake in pursuing exploration there.149

The announcement by Cal Energy in February 1993 came only a month after Secretary of the Interior, Manuel Lujan, Jr., confirmed the presence of significant thermal features in Crater Lake.150 His cover letter to Congress, meant to accompany the report mandated by passage of P.L. 100-443, represented an end point to a process that saw the NPS pitted against both Cal Energy and BLM. Opposition to listing by the latter resulted in the NPS citing a technicality to omit BLM's comments, as expressed in the report to Congress, even though it (very much like the USGS) had the status of consulting party.151 The lone USGS consultant hedged on the question of presence or absence of thermal features, though participants at a peer review meeting in January 1991 generally supported the affirmative position.152

Although the pronouncement by Lujan derived its basis from scientific findings, it also signified that the NPS had won the battle of public relations. Cal Energy operated almost exclusively on the defensive about its drilling near Crater Lake, with spokesmen being forced to either dispute evidence gathered by the dives or blame the alleged sewage influx from Rim Village for fluctuations in lake clarity.153 Both tactics crumbled in a wash of publicity favoring the NPS that surrounded the submersible in 1988 and 1989. Superintendent Benton publicly put further exploration of the lake at the top of his Christmas wish list, though he scarcely needed it after Soviet scientists from the Lake Baikal region visited the park in September 1990.154 The visit came two months after a Soviet-American research team found evidence of a hot vent field in the world's deepest lake. It provided Benton an opportunity to link the two lakes as "sisters," but he also subsequently allowed Buktenica to join Dymond on a follow up visit to Lake Baikal that resulted in joint studies on Crater Lake.155

The cooperative work with scientists on Lake Baikal capitalized on momentum provided by studies conducted on Crater Lake in 1988 and 1989, when the submersible obtained samples to substantiate an evaluation of the early volcanic evolution and post caldera volcanic history of Mount Mazama. In addition to allowing for analysis of rocks and sediments, as well as identification of subaqueous post caldera volcanology, the submersible provided the means to document life residing in the deepest part of the lake. These life forms included flatworms, nematodes, earthworms, copepods, ostracods, and midge fly larvae. Plant communities and their associated invertebrates were also found at great depths (85 to 460 feet beneath the surface) in a band that encircled the lake.156

Although the hydrothermal question occupied central position for a short time in park operations and public perception of Crater Lake, it was never divorced from the limnological program despite the series of separate reports. Collier and Dymond went back to their water column investigations upon submitting a final assessment of hydrothermal processes in May 1991. They again joined other researchers who conducted special studies of varying length connected with the limnological program. The CPSU at OSU served as the funding conduit for these studies, with most investigators being either graduate students or faculty members holding research appointments.157 Progress reports or summaries on the studies appeared in the limnological program's annual reports, with a final report with full presentation of results projected for 1993.

The limnological program held both a review of results obtained thus far and a symposium at roughly the halfway point in its ten-year study of Crater Lake. The symposium convened in Corvallis on June 21, 1988, as an annual meeting of the Pacific Division of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and led to publication of an anthology on the topic of Crater Lake as an ecosystem. It also allowed for presentation of divergent views, something discussed at length by the senior editor in her introduction to the volume.158 She made specific reference to controversies over possible hydrothermal activity and whether the clarity of Crater Lake might be affected by long-term sewage influx. A paper by Douglas Larson and two other investigators hypothesized a link between sewage and declining clarity, supplying some contrast to Gary Larson's more open-ended model of the lake, where multiple variables interacted to produce a dynamic lake ecosystem.159

Charles Goldman played the role of respondent at the symposium, in effect utilizing components of Gary Larson's conceptual model to compare Crater Lake with Lake Tahoe. This served to validate the approach Larson developed in 1985, but Goldman did not discount the possibility of sewage leading to elevated nitrate levels when he made specific recommendations for further study. His concluding statement even recalled Merriam's emphasis on cooperative research, though the modern aim was protection rather than visitor appreciation.160

Douglas Larson did not dispute the merits of a broad approach to the study and monitoring of Crater Lake, yet grew increasingly vocal about the limnological program failing to directly confront the possibility of sewage contamination. The NPS could point to removal (in 1991) of the septic leach field identified by himself and others as the potential source of trouble, given its geographic proximity to the relatively high nitrate levels associated with Spring 42 below Rim Village.161 Park staff routinely monitored this and other inner caldera springs, but did not study the hydrology and groundwater of the Rim Village area using the florescent dyes or salt tracers recommended by Stan Gregory and other OSU investigators who reported on the ecology of selected park streams in 1987.162 During peer review of this report, however, scientists on the panel recommended against conducting a tracer study because samples could not be taken from the spring at regular intervals during the year. Even if the leach field was connected to spring 42, they knew the dye could be missed if it surfaced during the winter months. The panel concurred with the Gregory report's recommendation for removing the leach field and sent this finding to Benton, who then worked with officials in the regional office to have a new system of waste treatment become part of the NPS line-item construction program.163

Another symposium held to observe the ninetieth anniversary of the park's establishment in 1992 triggered an exchange between Douglas Larson and Park Superintendent David Morris over whether the NPS had allowed sewage to reach the lake.164 The controversy quickly faded from public view, but Douglas Larson renewed his allegations the following year about how the NPS had not investigated the septic leach field as a possible source of contamination. In a letter to the chairman of the House committee on natural resources, he contended that the abundance of limnological data assembled in the report mandated by P.L. 97-250 did not meet direction previously given by Congress through the legislation.165

Panelists conducting a peer review of the ten-year study in February 1993 nevertheless concluded that the limnological program met the goals and objectives for monitoring and study on Crater Lake, but had gone well beyond what was envisioned by researchers in 1982. One member of the panel, Raymond Hermann, stated that the clarity question had been settled by the report, though he added a caveat about the processes controlling clarity were still imperfectly understood. The panel's chairman, Stanford Loeb, observed that Crater Lake stood alone among units in the National Park System in possessing a well-developed data chain. He made reference to the fact that only six or seven other parks had so much as a data set that might serve as a starting point for meaningful monitoring efforts. Loeb cautioned, however, that any future monitoring efforts should be driven by a hypothesis and statistically based experimental design. In a fairly direct way, Loeb tried to interest the NPS in a marketing program for long-term monitoring, one where collection of baseline data was integrated with compelling research questions. He threw out two possible focal points that reached beyond the confines of Crater Lake: global change (aimed at better understanding the processes affecting lake clarity) and the sensitivity of the lake's food web in relation to introduced fish.166

This program review, it should be noted, came at a time when Gary Larson and park staff lacked funding to proceed with long-term monitoring in conjunction with additional special studies.167 The process of authorizing another study of the lake's water quality began in 1992 when Oregon congressman Bob Smith drafted legislation aimed at providing $160,000 annually for monitoring over a period of ten years. Introduced in January 1993, his bill insured that funding for the limnological program held the top regional priority in an initiative intended to further professionalize natural resource management enacted as part of the NPS budget for 1994.168 Smith withdrew the bill once the initiative incorporated the amount requested for Crater Lake so that it became part of the park's annual (or "base") budget in October 1993.169

With the additional funding in hand, the NPS initially chose to replace an antiquated pontoon-style research boat designed for recreational use on calm water with an all-weather vessel. Hiring a second aquatic biologist, Scott Girdner, followed in order to assist the monitoring program with operations, data management, and reporting. The new boat and additional staff represented significant additions to existing infrastructure (such as previous installation of a laboratory at Park Headquarters and the boathouse on Wizard Island) so that a full-fledged monitoring and research program was now essentially in place.

Although monitoring the lake could be assured of a permanent place in park operations, special studies still depended upon project funds obtained largely with the assistance of staff working at the regional office in Seattle. The number of special studies subsequently declined in comparison to those conducted during the original ten-year study, though contributions to refereed journals on the limnology of Crater Lake appeared almost annually during the 1990s.170

Published research and attendant publicity surrounding the limnological program nevertheless led to creating a separate natural resources management division at the park in 1993, if only indirectly. The move stemmed from recommendations by personnel specialists at the regional office in Seattle who stressed that such a move would "reflect the importance of resource management programs and [create] a professional image" for the NPS in dealing with other agencies.171 This division initially consisted of two permanent employees and some seasonals hired with project money, then grew as funding opportunities permitted, but without publications having a direct effect on grade levels.172 Meanwhile, the only NPS employee working under a research appointment in relation to Crater Lake was stationed at the CPSU in Corvallis. This arrangement lasted until October 1993, when Gary Larson and his colleagues throughout the agency were involuntarily transferred to a "National Biological Service" by order of Bruce Babbitt, the Secretary of the Interior.173 After the NBS failed to gain congressional authorization as a separate bureau, however, Larson and other scientists initially hired by the NPS landed in the Biological Resources Division of the USGS. He continued in his role as principal investigator for the limnological program at Crater Lake and remained in Corvallis, while park staff and personnel based at OSU assisted with the operational aspects of long-term monitoring.174

The limnological program dwarfed other resource management activities at Crater Lake, however, its infrastructure of personnel and equipment allowed Buktenica, assisted by Gary Larson, to start a fishery restoration effort on Sun Creek in 1989. It targeted bull trout, the only native fish species in the park, which had been under threat through competition from introduced eastern brook trout. By 2000, three publications came of what was essentially a resource management effort, with the first (a habitat survey) printed as a report in 1993, followed by papers comparing methods of eradicating brook trout.175

As compelling as restoring bull trout or any resource management project in the park's backcountry might be, the bulk of scientific interest remained squarely fixed on Crater Lake and its geologic setting. Led by Bacon, journal articles by USGS authors referencing the park through 1995 greatly exceeded the number produced by limnologists and other specialists in aquatic biology. Pursuit of broader questions in volcanology and the use of funding sources other than the NPS may have been the reasons for this disparity in output, though USGS research also seemed to carry less political sensitivity than the limnological work. USGS publications (which also included open-file reports, field guides, and maps) had some effect on interpretation among park operations, with a few papers containing revisions to the geological story being presented to visitors.176 What was perhaps the most significant contribution appeared in May 1994 and presented the sequence of Mount Mazama's climactic eruption and subsequent formation of the lake as part of a cycle in the evolution of small calderas.177 It not only synthesized information about the lake floor (much of which was derived from the submersible dives in 1988 and 1989) for interpreters, but also gave them a new way of using Crater Lake as a model when making comparisons with other caldera lakes.178

Subsequent USGS work to discern volcanic and earthquake hazards that could affect the park or nearby communities had little effect on park planning or operations, even when the NPS contracted for seismic evaluations of several buildings as part of initiating construction projects at Crater Lake in 1999.179 Park managers and staff, however, eagerly embraced an opportunity to have the USGS oversee mapping the lake floor using new sonar technology in July and August 2000. The NPS provided ground support and most of the funding so that a research vessel could take more than 16 million echo soundings and produce a map where objects as small as one meter across could be identified.180 Multicolor bathymetry and selected views of Crater Lake were made available to the public as one result from the work. Bacon and others meanwhile capitalized on survey data to better assess morphology, volcanism, and mass wasting in the lake.181

Other Research, 1984-2002