|

CRATER LAKE

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER NINETEEN:

TRAILS

by Stephen R. Mark, Park Historian, 2013

|

Crater Lake National Park Trails Administrative History of Crater Lake National Park Stephen R. Mark Pacific West Region |

|

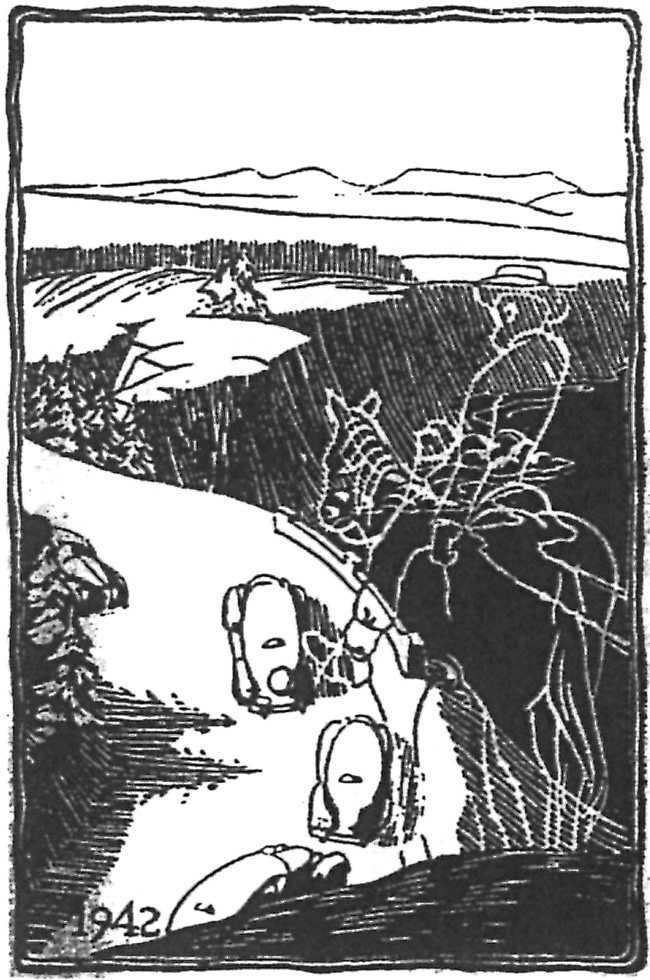

| The Trail Up Garfield Peak. Drawing by L. Howard Crawford in Nature Notes from Crater Lake 7:2 (August, 1934), 1. |

|

| Visitors on the Lake Trail, about 1910. Courtesy of the Klamath County Museum. |

|

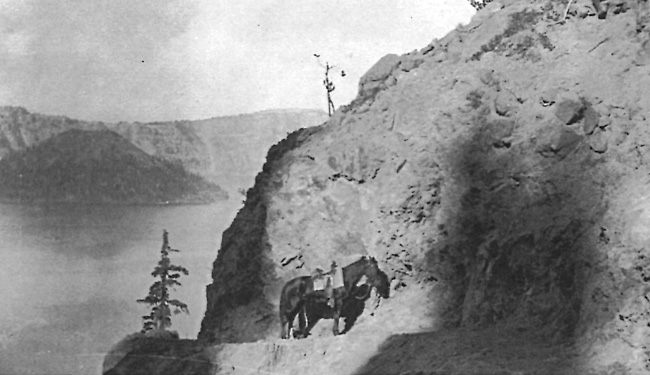

| Wizard Island and Crater Lake from the Sparrow Trail, 1917. National Park Service photo. |

Contents

Cover

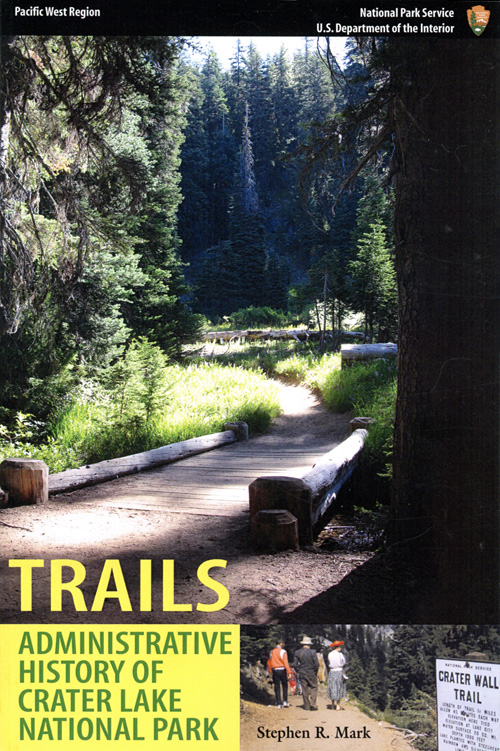

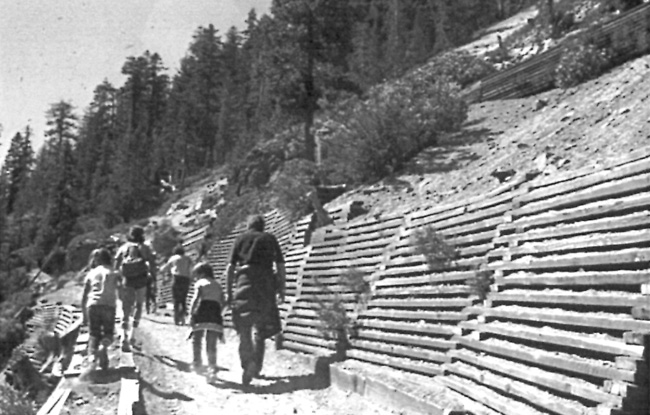

Cover Photos: (top) Footbridge on the Castle Crest Wildflower Garden Trail. Photo by the author, 2009. (bottom) Visitors on the Crater Wall Trail, early 1950s. National Park Service photo.Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Park Trails Prior to 1916

National Park Service Trail Building, 1917-21

Maintenance and Construction, 1922-28

Expansion and Re-Construction, 1929-32

New Deal Projects, 1933-41

Postwar Planning and Development, 1942-55

The Mission 66 Years, 1956-66

Austerity and a Changing Backcountry, 1967-80

A Holding Pattern, 1981-92

Convergence of Agenda and Funding, 1993-2010

Conclusion

Endnotes

Index (omitted from the online edition)

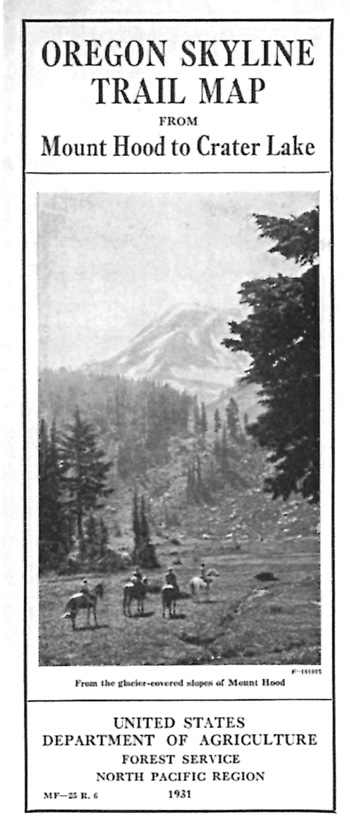

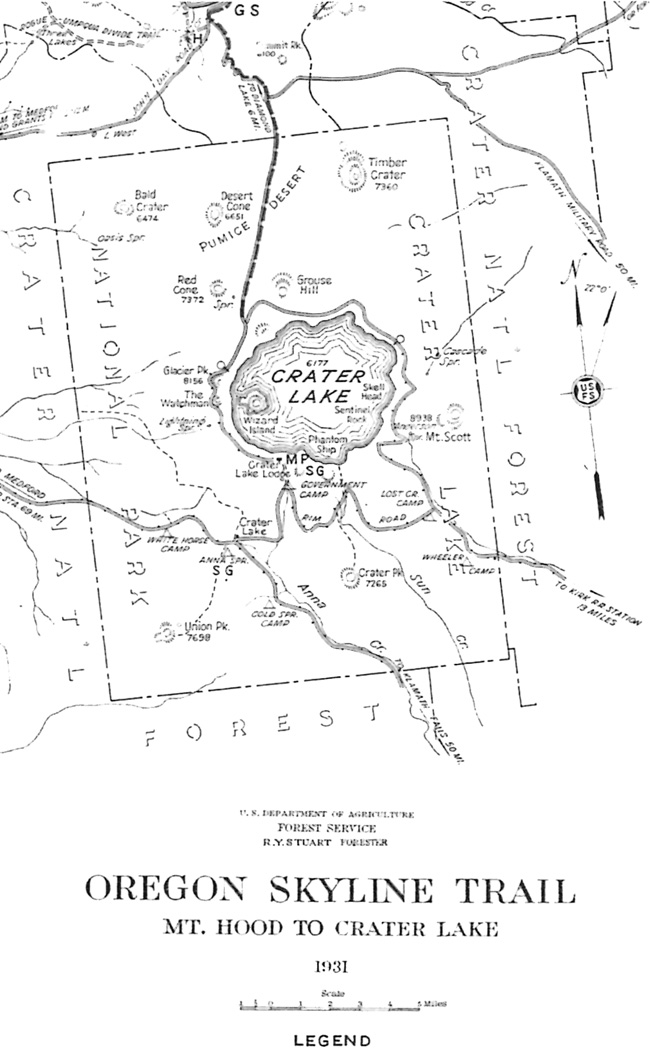

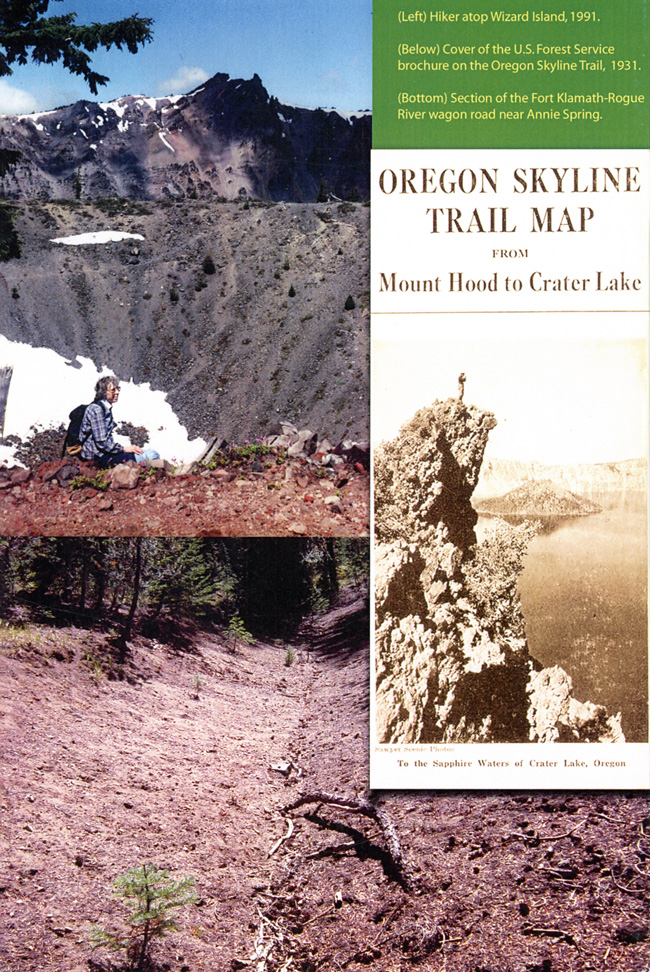

Back Cover(Left) Hiker atop Wizard Island, 1991. (Below) Cover of the U.S. Forest Service brochure on the Oregon Skyline Trail, 1931. (Bottom) Section of the Fort Klamath-Rogue River wagon road near Annie Spring.

Mary Williams Hyde did the final editing and layout. I also wish to thank Andrea Andresen, Gretchen Luxenberg, and Cathy Gilbert as this manuscript passed a critical stage in production.

Acknowledgments

This represents a third attempt to add other chapters to an administrative history of Crater Lake National Park, completed by Harlan Unrau in 1987. Some 25 years hence, it may now be time to revise or revisit the initial work, in whole or in part. While some trails received mention in Unrau's work, he did not index it, so its usefulness is limited to charting how pedestrian circulation roughly developed in the park. His is not alone in that regard, as my Historic American Engineering Record documentation, Addendum to Crater Lake National Park Roads (HAER OR-107), also contains information about trails, but is not indexed. This narrative attempts to correct that deficiency, though it also represents an effort to place trails in somewhat greater context than simply being an adjunct to park development in general, or roads in particular.

A chapter (19) on trails comes as staff members are embarking on a comprehensive trails plan for the park. Support for writing this chapter came from Superintendent Craig Ackerman, Acting Superintendent Vicki Snitzler, Management Assistant Scott Burch, Chief of Interpretation Marsha McCabe, and the Crater Lake Natural History Association. I started the draft in August 2010, at a time when the Plaikni Falls Trail was nearing completion, having earlier assisted on various trails projects from 1997 onward. My thanks go to former Trails Leader Cheri Killam Bomhard, who has shown how the hiking experience of visitors and staff can be improved through realignments that enhance how the landscape is seen and enjoyed. The narrative also benefitted from talks given at the park's science and learning center during the summer months to employees and the dialog that resulted. Mary Williams Hyde did the layout, with funds for printing provided by ........

Stephen R. Mark

December 2012

Introduction

It is fair to say that trails in Crater Lake National Park have received far less attention as circulation devices than roads. There are numerous reasons for this, not least being the distances required for visitors to reach the park and costs associated with ensuring safe vehicular travel. Yet trails can be as central to experiencing the park or more so, especially since they require travel by foot, horseback, and (when covered by snow) skis or snowshoes. Their origin, construction, and use is the subject of this paper, one aimed at providing background and context for how these circulation features were developed over the course of more than a century.

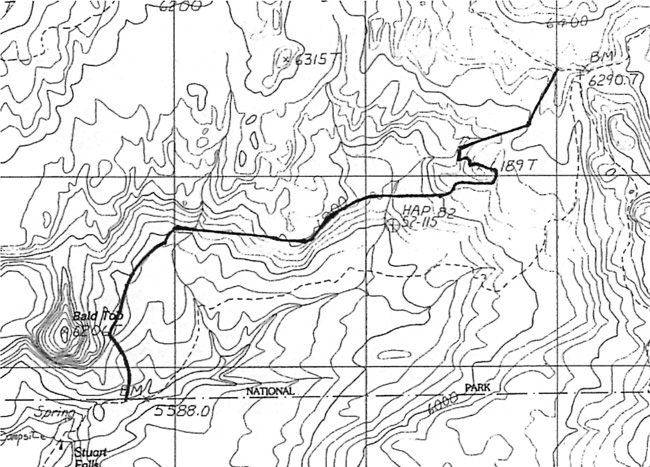

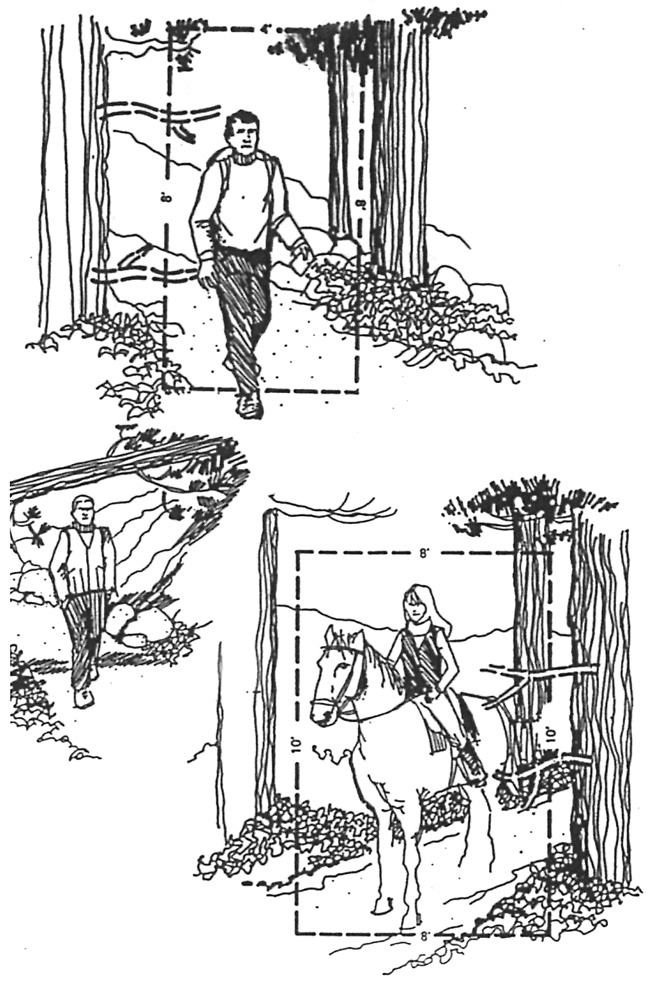

Generalizing about any "system" of trails can be difficult because the term trail has numerous meanings. In this case, trails are separated into four broad categories, beginning with those that are or were beaten paths with few efforts made to improve and maintain them for use by pedestrians or horses. Second, some trails exist with minimal location work, but have been marked by blazes, tags on trees, or signs and receive use that includes skiing and snowshoeing. The third category is limited to roads originally constructed for wagons or automobiles, but subsequent use has been limited to pedestrians and stock. The fourth category of recreational trails usually exhibit engineered qualities that in many respects make them somewhat akin to highways designed for foot travel.

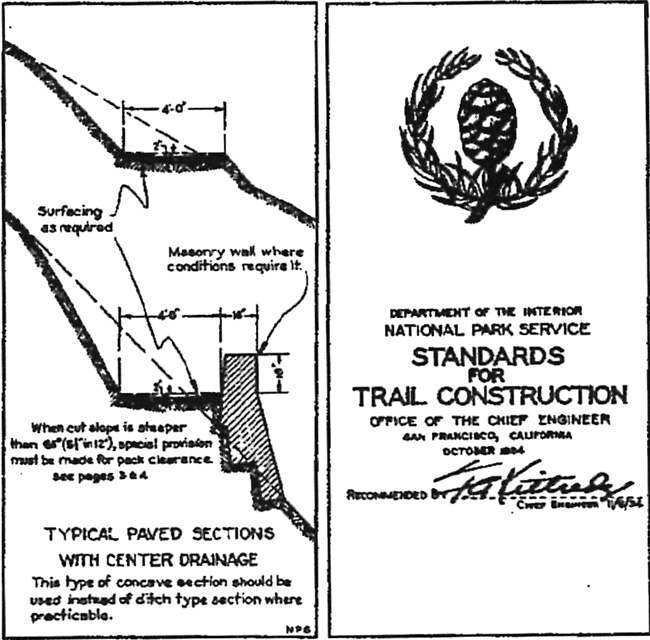

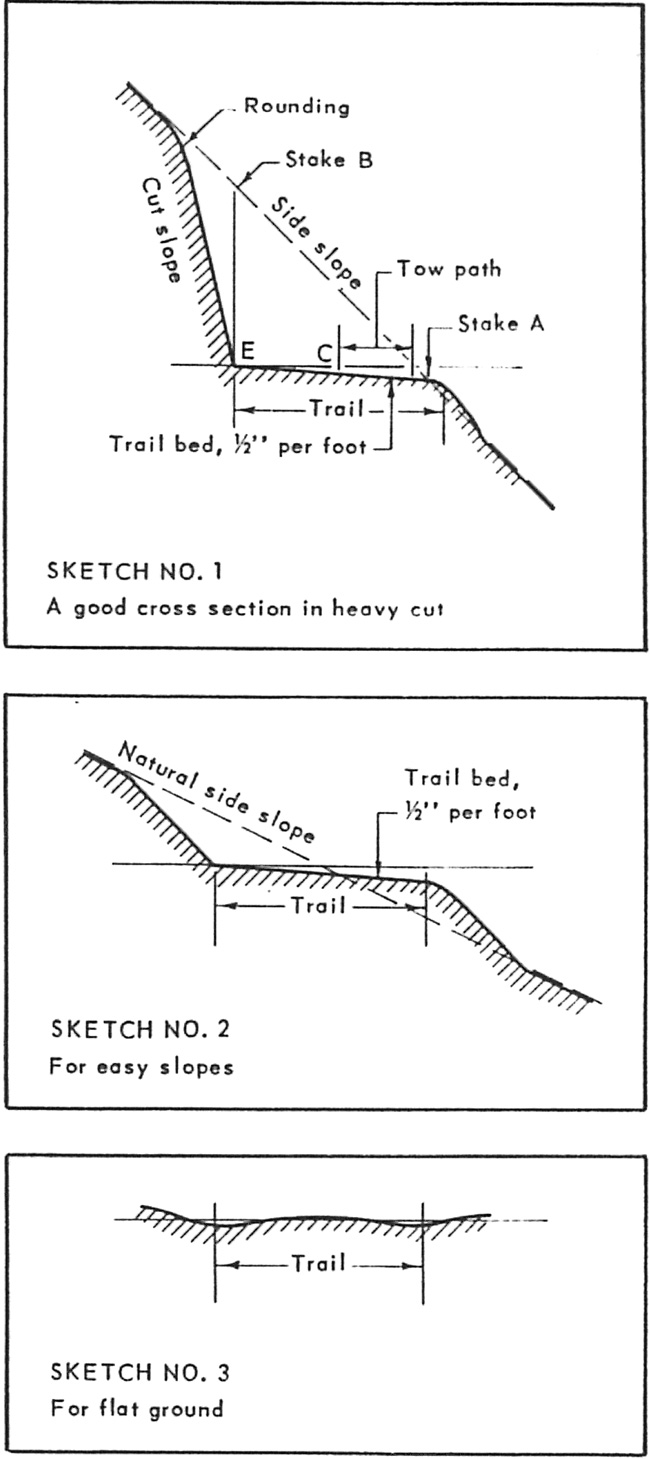

There is some overlap between categories, since some trails at Crater Lake can fit into more than one, but they provide a starting point for describing the intent of their builders, methods of construction, and subsequent realignments. Recreational trails can be further subdivided into the front- and back-country types, but even within these designations, there is often considerable variation in what can be called typical sections. It is probably safer to say that recreational trails tend to follow established standards for width, grade, curvature, and drainage features. Whether intended for pedestrians and/or stock, location work preceded their construction, and in the best examples, trail building reflected the principles expressed in the NPS standards of 1934.1

|

| Excerpts from the NPS Standards for Trail Construction, 1934. Courtesy of Electronic Technical Information Center, Denver. |

Previous documentation, notably in the second volume of an administrative history by Harlan Unrau and a historic resource study by Linda Greene, included trails as a minor component of their work relating to the development of park infrastructure. Apart from the problems associated with construction and maintenance of trails used to access the lakeshore, both accounts are largely limited to depicting the extent of park trails at selected points in time. What drove initial construction, much less changes, their maintenance, and in some cases, interpretation, has been overlooked and could prove useful to future planning efforts. So might a summary of trails that have faded into disuse and the reasons why some proposals for trails in the park did not come to fruition.

Archival records relating to most individual trails are generally fragmentary when compared to roads or other types of infrastructure. The relatively small expense of trail construction and maintenance has meant that few contracts (with their inspection reports and other information) were let for such work. As a whole, the documentation on trails at Crater Lake consists of some reporting on construction, but quite a bit less on maintenance or various changes made in the field. Planning documents, photographs, interpretive guides, and interviews can fill some of the gaps in source material. Yet detail about the factors that influenced location, realignments, and maintenance can often be elusive and sometimes vexing.

In acknowledging these limitations of the record, it is still possible to generalize about which trails have received the most attention from park managers over the past century or so. Given the challenging terrain and comparatively heavy use, it is not surprising that trails to the lake have consumed more funding and administrative time than perhaps all the other types of pedestrian routes combined. In descending order, the next group consists of trails leading to popular viewpoints along the rim and those in the main developed area of Rim Village. Other "front country" trails (that is, designed for day use hikes of relatively short duration) located away from the rim, but in proximity to paved roads, are the next in line. Visitation is considerably lighter in the backcountry, where the trail "system" makes extensive use of former fire roads. There are exceptions, however, as realignments completed by the park's trail crew since 1997 have diverged considerably from the fire roads in some places.

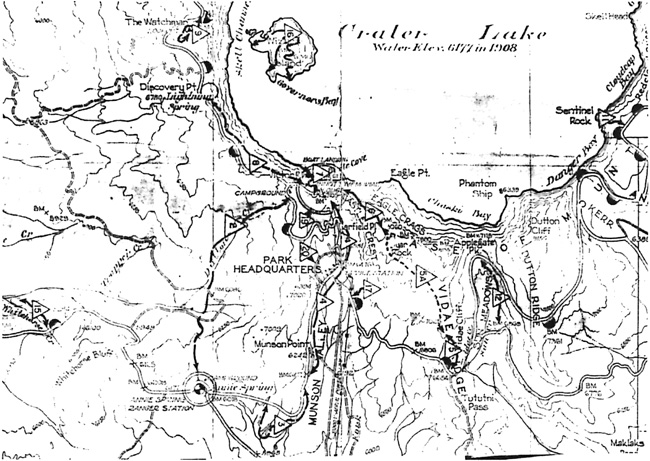

Park Trails Prior to 1916

The period preceding the advent of National Park Service administration at Crater Lake includes some antecedent trails, even if most of them can be characterized as either beaten paths or blazed tracks. Among the beaten paths are those used by tribal members resident in the Klamath Basin to reach Huckleberry Mountain and other destinations west of Crater Lake that required travel through the area that later became the national park.2 Most prominent among these was an east-west route roughly corresponding to a subsequent wagon road built by soldiers from Fort Klamath to the Rogue River in 1865.3 Two of the Indian trails remained prominent enough to be mentioned in field notes for the boundary survey of the newly established Crater Lake National Park in 1903, with one of the routes being a path to Huckleberry Mountain, located in the adjacent national forest.4

|

| Nineteenth century travelers making their way to Huckleberry Mountain. Photo credited to Ramona Hanks in Klamath Echoes (Klamath Falls: Klamath County Historical Society, 1968), 93. |

Opening of the wagon road in 1865 eventually induced a party of visitors from Jacksonville to mark a route by blazing trees from a point on the road near Dutton Creek about two miles to the rim of Crater Lake. The blazed track discouraged travel by wagon at first due to the steep and rough terrain, but had been improved enough to be called a "road" in visitor accounts from the 1890s.5 Nevertheless, many camping parties chose to remain along Dutton Creek due to the availability of water, something largely absent at the rim, and then walked to see Crater Lake. Visitors used a path to the lakeshore from the rim by 1890, though more than one account described the precipitous descent from the future site of Crater Lake Lodge as hazardous, not least due to the high likelihood of rockfall.6

Having a safe trail to the lakeshore became a management concern upon the appointment of William F. Arant as the park's first superintendent in the summer of 1902. The path necessitated a dangerous descent of 900 feet to Eagle Cove, so Arant requested $500 for improvements beginning in 1903.7 He reiterated the request, which included a cable for visitors to use in the most ominous section, in subsequent annual reports. No substantial improvements to its condition came until 1910, when a survey party from the Army Corps of Engineers made some changes in its location. As a small construction crew began work that autumn, they added switchbacks to lessen the grade and widen the route where possible. It still required what Arant described as "considerable repair work" each year due to annual washouts and other damage caused by rain and melting snow.8

|

| Visitors in the "Lower Campground" near Dutton Creek about 1900. Photo by Peter Britt, courtesy of the Southern Oregon Historical Society. |

As part of conducting the earliest scientific work at Crater Lake, J.S. Diller of the U.S. Geological Survey also compiled the first topographic map (in 1896) of what Congress would later designate as the national park. This fixed the park's boundaries in 1902, but as an aid to visitors who wanted to see important geological features, he promoted a pack trip around the rim. Depicted and described as a circuit as early as 1897, Diller noted five years later there was no trail yet in existence for those who wished to follow the route.9 Instead, the closest approximation to any piece of the route started where the "road" blazed in 1869 terminated at the rim. The boundary survey of 1903 described the path as leading west from there to the "foot" of the Watchman, past Glacier (Hillman) Peak and then north/northeast to Diamond Lake.10 Located some 400 feet in elevation above Diller's suggested pack route, Arant described the path as "not so much used." He called for its improvement as early as 1906, recommending that a "good trail" could lead from the informal campground (at what later became Rim Village) to the summit of Hillman Peak, estimating that an appropriation of $200 would be needed for the work.11

The park's total appropriation for the 1905 season amounted to only $3,000, and trail improvements did not feature as a budget item since much of the work that summer focused on completing a new wagon road to the rim through Munson Valley. In his annual report, Arant described what he considered to be the other park trail of that time, one that departed from the undeveloped campground on Dutton Creek and went west and northwest to Bybee Creek, eventually heading out of the park.12 He also thought it needed improvement, describing the trail in his report for 1909 as little more than "mere tracks of horses being ridden from one point to another."13 Appropriations had increased enough in 1908 for locating and marking a trail from the park headquarters (at that time located at Annie Spring) over to the Pinnacles on Wheeler Creek and then to Mount Scott. It, and what amounted to another set of tracks from headquarters to the base of Union Peak, scarcely rated any better in Arant's estimation than the path that went past Bybee Creek.14

Arant urged that the route to Mount Scott be converted to a wagon road in order for visitors to enjoy greater access to that part of the park, but he lacked the funding necessary (estimated at roughly $250) to make it happen. Trails, of the kind that furnished a beaten track as a precursor to more permanent development, represented an inexpensive device that had the potential to enhance the park's popularity in advance of the funding needed for automobile roads or facilities like hotels. He therefore proposed a trail along the rim to Watchman and Hillman Peak, as well as another starting from an unspecified point on the road leading through Munson Valley to what later became known as Rim Village. The latter might take visitors on horseback to Crater Peak, and then down Sun Creek.15

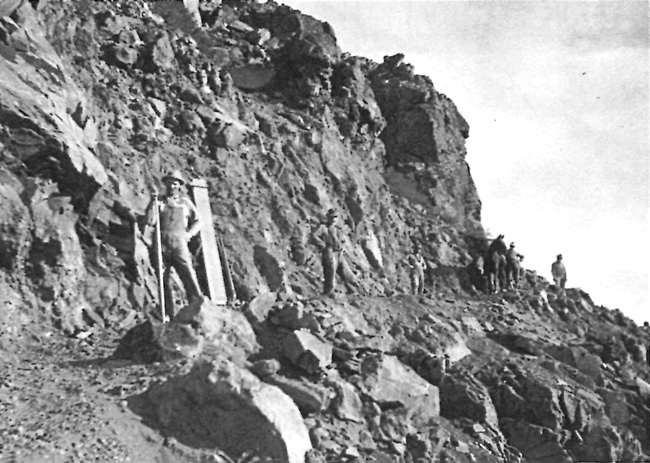

Only one of Arant's proposals for improved trails or additional routes came into being while he served as superintendent from 1902 to 1913. A small crew improved the trail down to Crater Lake in 1910, but this work largely derived from the presence of H.L. Gilbert from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, who arrived in the park that summer to begin location studies for a system of roads and trails. To be built by the Corps from annual appropriations over multiple years, the system included trails as a small item in their total estimate of the $627,000 needed for construction. The share for trails amounted to a total of $15,000, thought to be sufficient for building 100 miles of trails to "afford accessibility to points of minor interest in the park, and to portions remote from any of the [proposed] wagon roads."16

|

| Campers in what later became known as Rim Village, about 1910. Courtesy of the Klamath County Museum. |

Very little of the proposed trail mileage ultimately materialized from the Corps, mainly because work to grade approach roads and a circuit route along the rim took precedence during the project, which began in 1913 and terminated at the end of June, 1919. The Corps spent just two-thirds of the amount they originally estimated, almost all of it on a road system that never went beyond the grading phase of construction. When the Corps finally left the park, the entire project stood at roughly 50 percent complete. It included building only one trail, but even that one initially served the purpose of allowing for construction crews and equipment to pass between the ends of graded sections on the Rim Road near the Watchman. Less than a mile in length, the trail went up the south side of Watchman and over to what was later called the Watchman Overlook. One engineer described it as having been built in a "cheap" manner during the summer of 1916, varying in width between three and four feet, and on an average grade of 20 percent. He contended that it should be considered part of the proposed trail system since the route shortened distances by foot or saddle horse along the back of the Watchman and could be used by visitors to ascend the peak, where a fire lookout had been built in 1917.17

|

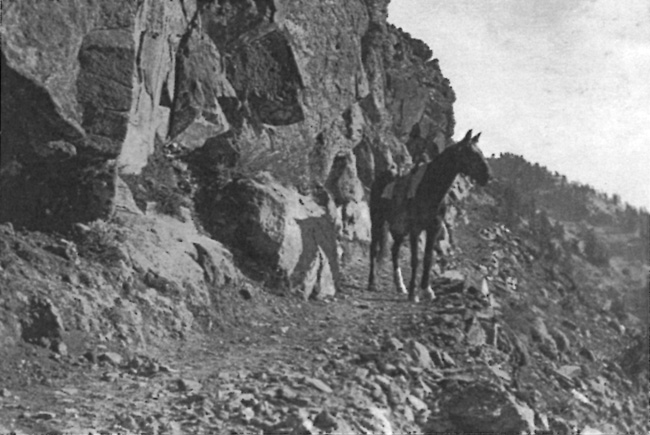

| On the way to Huckleberry Mountain from Fort Klamath, about 1900. Courtesy of the Hescock family. |

William Gladstone Steel succeeded Arant as park superintendent from 1913 to 1916. His most pressing concern in regard to trails was the route to Crater Lake, which required considerable work during his first summer in the job. As a follow up, Steel recommended that another $200 be spent to remove rocks from the trail so that burros (which he wanted the park concessionaire to rent for the use of visitors) could pass over it.18 Conditions on this trail had scarcely improved two years later, when a visit by William Jennings Bryan, the recently resigned U.S. Secretary of State, prompted Steel to pitch the need for a tunnel to the lake. Such a device could obviate the need for a "laborious one thousand feet or more steep descent and climb over a slippery and dangerous trail," something Bryan considered "almost impossible for old people."19 Despite the publicity, the tunnel proposal never gained traction, though it prompted Steel's supervisor, General Superintendent of National Parks Mark Daniels, to recommend that new trail "be built as near to the water's edge as possible and as far around the lake's shoreline as practicability will allow."20

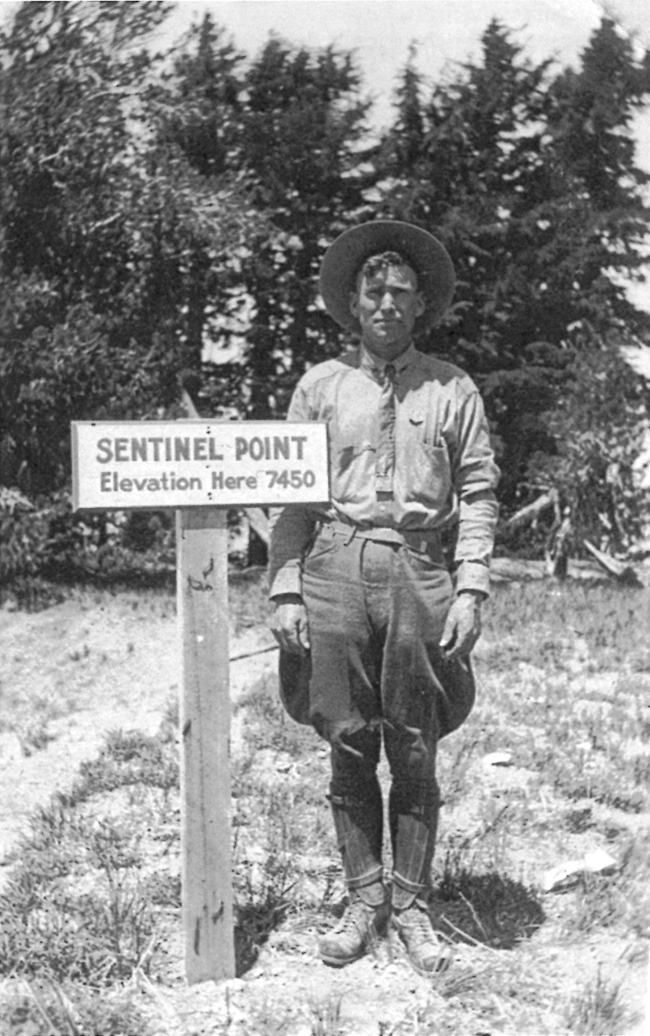

Steel did, however, expend his annual allotment of $250 for rebuilding or "improving" the lake trail, supposedly widening it from two to four feet over its 2,300 foot length.21 He also had another $250 in 1915 to build a trail to the top of Wizard Island. As something of a justification for both developments that summer, the government provided $150 to place crayfish in the lake as food the trout that Steel continued to plant in Crater Lake.22 Steel also found a way to build a four foot trail to Sentinel Point, from where the Corps of Engineers supplied a stopping point for motorists on the Rim Road. This came at the request of Assistant Secretary of the Interior Stephen T. Mather, who presumably approved paying for this relatively small project with the funding provided for paying seasonal rangers.23

Daniels, meanwhile, worked on a plan for Rim Village that summer and thus refined some of his subordinate's recommendations. He began by suggesting a suitable trail to Garfield Peak, given how visitors from the lodge often climbed partway to the summit, but turned back due to the difficulty of going any further. Daniels also recommended the views from Arant Point and Union Peak, so suggested trails to them from the camp near Park Headquarters at Annie Spring. Steel no sooner received an allotment to build a trail up Garfield Peak in 1916, but instead wanted $400 of it reallocated to repair of fences and buildings.24

|

| Visitors with a park ranger at Sentinel Point, about 1920. Photo by Alex Sparrow, courtesy of the Southern Oregon Historical Society. |

By the time Steel resigned as park superintendent in November 1916, he made a reference to outlining a system of trails in his last annual report. Although he supplied few details about the larger plan, Steel called for a route to reach the top of Mount Scott. As preeminent among park trails, he wanted it built on a grade that allowed for subsequent widening, with the eventual aim of use by motorists.25 Although not as chimerical as the tunnel proposal, the summit trail idea attracted no more support in terms of funding than had Arant's recommendation for a wagon road to reach the park's highest point.

Working up estimates for a proposed annual budget at this point involved one submitted by the War Department for road work since the Army Corps of Engineers built the Rim Road and other routes at Crater Lake on a day labor, rather than contract, basis. Another group of estimates came from Interior through the superintendent or other officials appointed to act in his place. Interior's estimates for the season of 1917 represented a more than eight fold increase (to almost $68,000) over what Congress appropriated for Crater Lake in 1916. Nevertheless, trail work totaled $11,475, of which a new trail to the lake accounted for more than half that amount. Eight other routes were included, beginning with a half mile trail from Kerr Notch to the lake. Others consisted of a trail to the top of Garfield Peak (1 mile), a graveled path along the rim near Crater Lake Lodge (.25 mile), one connecting the Rim Road from Devils Backbone to a proposed ranger station at Oasis Spring (8.5 miles), another from Cloudcap to a proposed ranger station at Cascade Spring (2 miles), a trail from Polebridge Creek to a ranger station in the Red Blanket basin (5 miles), one connecting Cloudcap to the top of Mount Scott (4 miles), and finally a route going from the West Entrance Road to Union Peak's summit (5 miles).26

|

| Wagon and team on wooden bridge in Crater Lake National Park, about 1900. Courtesy of the Klamath County Museum. |

For his part, Steel's annual cost estimates provided to Congress for trails could almost be characterized as a five year plan. In addition, to listing trails to Garfield Peak, Crater Lake, and the Watchman as his top three projects, he listed ten others. Two of them involved building routes along the lakeshore (from the boat landing in Eagle Cove to Kerr Notch and the Watchman slide, respectively), a trail to the water from Kerr Notch was proposed. So too was the reemergence of a proposed trail from the Rim Road to the top of Mount Scott, as well as foot paths suggested by Daniels from Park Headquarters at Annie Spring to Arant Point and Union Peak. Other proposals included one of some 12 miles between headquarters and "Llao Creek" (in the park's northwestern quadrant) as well as a trail near the West Entrance Road, along Castle Creek Canyon, and a more circuitous one mile route aimed at connecting Annie Creek Canyon with Dewie Falls.27

National Park Service Trail Building, 1917-21

If trail construction had to largely depend on annual appropriations made individually to Crater Lake and other national parks in the years before creation of the National Park Service, then it is hardly surprising that so little beyond a dangerous path to the lake could be used by visitors over the first 15 seasons since the park's establishment. Only once during Arant's tenure had yearly appropriations for managing and developing Crater Lake exceeded $3,000. Congress became more magnanimous while Steel served as superintendent, with appropriations reaching $8,000 per year for the period of 1913 through 1916. By contrast, the newly appointed NPS superintendent Alex Sparrow received $15,000 to administer the park in 1917.28 That figure allowed Sparrow latitude in pursuing projects that neither of his predecessors enjoyed, with a comparatively large amount of trail construction completed during the summers of 1917, 1918, and 1919.

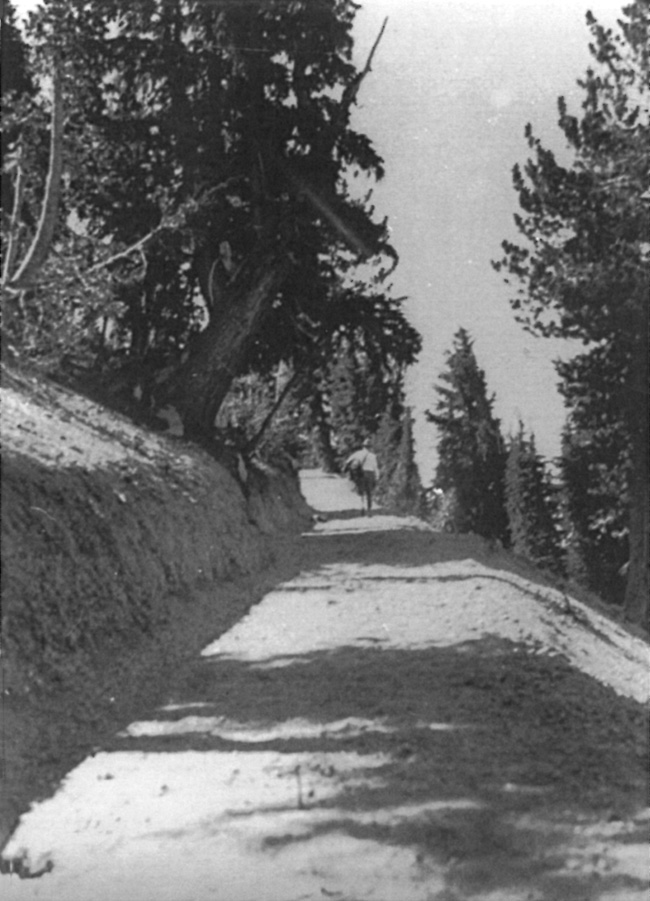

Sparrow's training as an engineer led him to Crater Lake in 1913, having been part of the Army Corps contingent assigned to build the park's road and trail system for the following three seasons.29 Although the Corps of Engineers brought only one trail into existence during their stay in the park, Sparrow in his new role as superintendent could fund construction of several new routes intended for hikers and equestrians. NPS crews built three trails in 1917, one of them accessing Garfield Peak from the Crater Lake Lodge in Rim Village. Relatively steep at only 1.25 miles in length (as opposed to 1.7 miles after realignment in 1931), the route had an average width of four feet and cost $960. The new trail also included examples of benching (used to maintain a uniform grade with rock in fill sections), dry laid retaining walls, and sheeting—which avoids cross drainage devices like culverts or water bars by building the trail so that water is shed uniformly across it. Another trail connected the Watchman with Rim Village, a distance of four miles for a mere $460. Generally aligned so that it followed a route closer to the caldera's edge than the Rim Road, it ascended the south and east sides of Watchman.30

|

| Newly-built section of the Garfield Peak Trail, October 1917. Photo by Alex Sparrow, author's files. |

With an appropriation available, Sparrow also had the trail to Crater Lake reconstructed. This amounted to acting on a recommendation made by Daniels three years earlier, though fortunately the funding exceeded Daniels' original estimate of $1,000.31 The NPS aligned it in order to avoid a wet area below Rim Village where running water led to washouts and continual maintenance. A NPS construction crew lengthened the trail to roughly 1.25 miles, lessening the grade by extending switchbacks below the lodge. Built at a cost of $4,462, it provided visitors with a way of participating in boating and fishing, but also allowed for the use of horses and burros when the trail bearing Sparrow's name opened in 1918.32

Although Sparrow reported that the park's trail system in 1918 as consisting of 22 miles, part of this total included rough one-lane service roads built in conjunction with a trail of varying standard.33 An example was the "trail" of four miles or so built in 1918 for light vehicles and horses toward the base of Union Peak. It started from a point about half a mile west of Annie Spring on the Medford Road (built by the Corps and following the same general alignment as Highway 62 later on) and ran in a southwesterly direction. Much of it consisted of a track cut about sixteen feet wide, in order to improve it for automobiles in the future. Reaching the top of Union Peak still required an almost cross country climb of some 700 feet over the last quarter mile, with a "safe and easy" ascent required to reach the summit from the end of this trail.34

Sparrow also described a point about one-eighth of a mile from the base of Union Peak, where a blazed track commenced toward Bald Top and Red Blanket Canyon, some two miles away. Described as rough and still poorly defined, but practical for pack animals, Sparrow saw it as primarily useful for future ranger patrols. As a way of preventing poaching and limiting the spread of wildfires, the route left the park near its southwest corner. It represented a link with trails built by the U.S. Forest Service on the adjacent Crater National Forest, but especially what Sparrow called an "outlet down Dry Creek toward the Wood River Valley," he pledged that the rangers using the route would improve it.35

|

| "The Imp," Superintendent Sparrow's horse, on the trail from lodge to Garfield Peak, November 1917. Photo by Alex Sparrow, author's files. |

Sparrow still counted the Bybee or Copeland route (which was likely a trace leading north from Dutton Creek and then west toward the park boundary) as part of the park's trails, but he figured its length at only 2.2 miles. He also listed some former wagon routes as trails, such as the one running from Annie Spring over to Dutton Creek and then to the rim. It covered a distance of four miles, while another wagon road segment one mile in length built by Arant connected Munson Valley with Rim Village.36 Sparrow described a foot trail to the crater on Wizard Island (built when Steel served as superintendent) as good, but wanted it widened (to four feet) and extended for a distance of 5,000 feet. The route to the top of this cinder cone had not received specific mention in the annual reports written by park superintendents to this point, though some visitors climbed to the island's summit by way of an informal track since 1896.37 The trail to Sentinel Point, built at Mather's behest in 1915, had meanwhile become popular enough for the NPS to place signs as part of alerting visitors to the viewpoint.38

|

| View on the trail to the Watchman from Rim Village, October 1917. Photo by Alex Sparrow, author's files. |

Two more trails were added during the season of 1919, though Sparrow described roughly two-thirds of each route as passable by motor vehicle. One began near where the old Rim Road crossed Sun Meadow and followed a vehicle track for one mile, then narrowing to a "very easy" foot or horse trail to Sun Notch as the terrain became more steep and rocky. He justified establishing this route by stating that the best possible view of Phantom Ship could be obtained from this point on the rim, but no doubt remembered an earlier Corps of Engineers plan for building a road linking Sun Notch with the Rim Road.39 The other trail connected the old Rim Road with Crater Peak. Sparrow wrote that light vehicles could negotiate the first 1.5 miles, after which it was possible to reach the top on horseback in less than a mile. While very steep, that last section afforded a "magnificent view of the Klamath Lake Country."40

|

| "Ranger Perl" at an overlook on the Rim Road that later became know as Victor View. Photo by John Maben, author's files. |

NPS appropriations for the park almost doubled in 1920 (to more than $28,000) over what Sparrow had on hand in 1917, so that the trail "system" grew to 34 miles. Virtually all of the mileage added that year, however, came in one project. It involved making eight miles of the Diamond Lake Trail passable for vehicles by connecting it with the Rim Road. A pack trail had previously come south from Diamond Lake, but after traversing the Pumice Desert, it cut west to terminate at Red Cone Spring instead of ascending the rim.41 Sparrow had hoped to build a connecting trail from Park Headquarters at Annie Spring in 1919 for some $3,000, an ambitious project aimed at staying below the "snow line that blocks the Rim road for about eleven months of the year."42

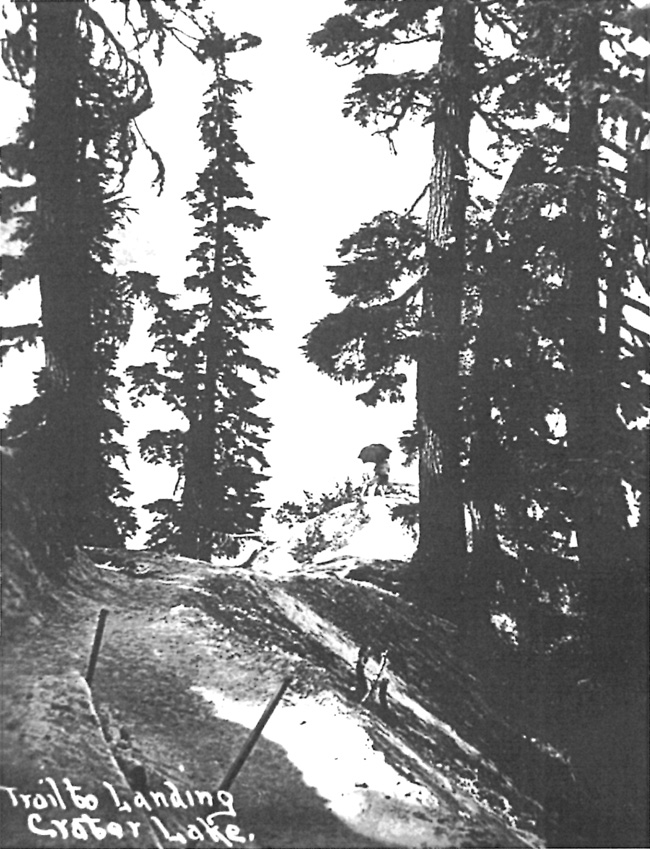

Not only would a trail 12 miles in length (and intended for light horse-drawn vehicles) connect with the "old Indian trail to Diamond Lake, between Llao Rock and Red Cone," but could also allow for branches to be run to Oasis Spring and Bald Crater.43 Parts of the larger rationale behind this effort came from two sources: an expansion proposal launched by the NPS several years earlier for the park to include Diamond Lake, and a desire to eventually shorten the travel time needed to reach Crater Lake from points north.44 Even if a state highway had yet to reach Diamond Lake or the park's north boundary, by 1920 scenic promoters pitched the idea of a road (or "Skyline Route") to run along the summit of the Cascade Range between Mount Hood and Crater Lake.45 When the Mazamas, a Portland-based mountaineering group founded by W.G. Steel, reached the rim on foot from the north over this route in August 1921, Sparrow called it the "Oregon Skyline Trail." Less than three weeks later, he and two others became the first to go between Diamond Lake and Crater Lake in a motor vehicle over the same route.46 The route remained primitive enough to also be called the "Diamond Lake Auto Trail," so that only the most confident motorist undertook a journey across it.

Maintenance and Construction, 1922-28

|

Whereas use of the words "road" and "trail" could be interchangeable at times, expenditures for maintenance tended to distinguish between them. Sparrow noted that the NPS built no new trails in 1922, but opening and maintaining the trail named for him continued to require considerable effort. While it received about 80 percent of trail use at the park, this trail to Crater Lake consumed two-thirds of the annual trail maintenance allocation. Under Sparrow's successor, Charles Goff Thomson, the NPS needed to spend three-quarters of the park's trail budget on this route in 1923 while building no new trails.47 With visitation growing and the annexes completed on an expanded Crater Lake Lodge the following year, Thomson began talking about the need for a new trail alignment. He wanted to eliminate having visitors pass behind the hotel as they entered the caldera, but also some heavy grades (the steepest was 28 percent) along it as well as some unspecified "dangers" associated with Sparrow's alignment.48

As if to illustrate the latter point, a contemporary account of opening the trail appeared in 1923, as part of a volume on travel to Crater Lake and other destinations:

"There is but one trail down to the water, and without a trail the descent is extremely difficult and dangerous, however carefully you choose your spot. On our first day at the lake, this trail was still snow-blocked, but the boatmen and one or two fishermen had been down and got a few boats out, and, being possessed of Alpine stock and a rope, we saw no reason to wait. But even as we started down, the government gang appeared, armed with shovels, and began on the trail. When we were two or three hundred feet below them, we had to work down through a sharp ravine, like a bottle neck, into which the concavity of the drift was drawing all the lumps of snow tossed out by the trailbreakers above. As they saw us approaching this chute, they redoubled their efforts, and rained upon us a veritable barrage of snow-cakes, which attained tremendous velocity long before they reached us. Some of them were large and solid enough to knock your feet out from under you, or give you a staggering blow on the head, and we clung to our rope as we passed that bombardment with more tenacity than on many a steeper slope, taken in the higher mountains.49

|

| Visitor on horseback at the boat landing, about 1921. Photo by Alex Sparrow, courtesy of the Southern Oregon Historical Society. |

Construction of a new trail to Crater Lake did not start until 1927, after scenic photographer Fred Kiser "blazed" the route and guided a NPS survey party that made the final location.50 It started some 800 feet west of his studio at a site adjoining the new plaza in Rim Village, across from where the concessionaire's cafeteria was to be built in 1928. Intended as a NPS "standard" trail for front-country use, design of what became the "Crater Wall Trail" included 24 short switchbacks in traversing 900 feet of relief over its length of 1.6 miles.51 Those switchbacks, however, represented the biggest challenge for the annual tasks of opening and maintenance over the next three decades given the combination of loosely consolidated material inside the caldera, high snowfall, and sections prone to avalanches. At the outset Thomson waxed about how the trail better accommodated visitors who did not wish to walk during a brief period when the concessionaire experimented with renting mules and burros. As such, the trail was designed to be six feet wide, with a maximum grade of 15 percent. It terminated on a natural bench with more room for docking, so that circulation there improved in comparison to the site further east where the Sparrow Trail reached the shoreline.52

Like his predecessors, Thomson saw a safe and easy trail to the lake as critical to visitor enjoyment, so he thought spending an estimated $10,000 on building the Crater Wall Route perfectly justifiable. Annual visitation almost quadrupled over the six years he served as superintendent (1923-29), and Thomson devoted much of his time to planning for enhanced park infrastructure. He had the help of a slowly growing NPS staff of landscape architects and engineers who could handle many of the technical details of design and oversee construction projects once funding had been secured. During the first few years of Thomson's tenure, construction funding of any kind could be characterized as meager, though by 1926 this had begun to change. Building new trails away from the lake did not rise to the top of NPS priorities for the park, though some small projects could still fit into Thomson's larger objectives.

Increasing visitation brought more people who wanted to camp, so the number of designated areas began to grow in number beyond the two sites (Rim Village and Annie Spring) which already possessed some amenities such as tables and a water system. Four others were shown on the park map by 1924, but they were little more than small areas where motorists could stop next to an approach road. These had a few spots cleared for camping, possibly a pit toilet, and utilized surface water from an adjacent stream.53 Thomson located one of these peripheral camps on Whitehorse Creek on the Medford Road (later known as west Highway 62), and a small crew made a couple of modest improvements that summer.

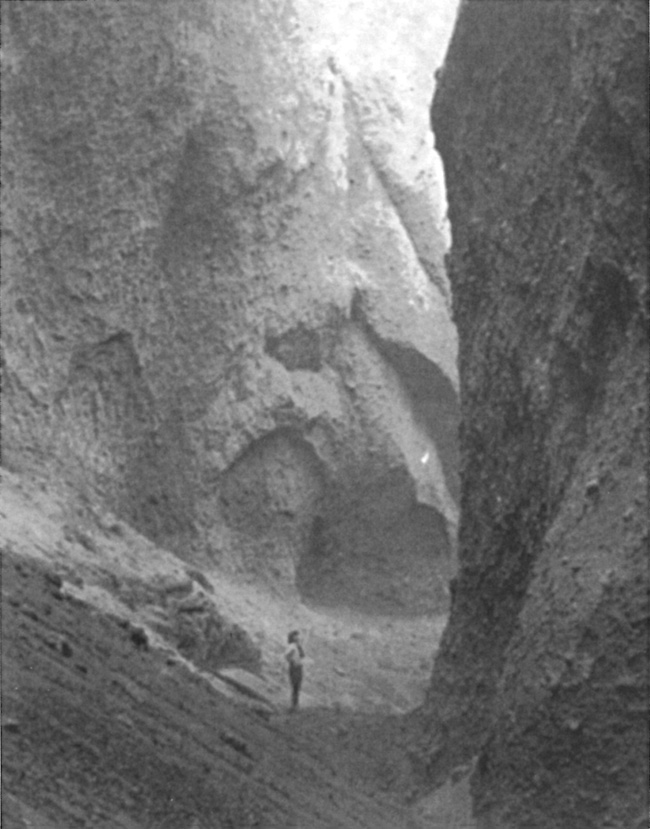

A new trail from the road bridge on Whitehorse Creek to the "Giant Nutcracker," a narrow gorge later known as Llaos Hallway, quickly became the most auspicious. The trail, as such, went for a distance of a quarter mile to where the creek met a seasonal tributary, and from there hikers had to traverse the gorge on their own.54 It came about when Thomson and Chief Ranger Pete Oard traversed Whitehorse Creek in order to access Castle Creek Canyon in September 1923. They so enthusiastically reported what they found that other NPS employees subsequently made the trip and fueled Thomson's proposal to open a trail the following spring. The Washington office approved this comparatively small undertaking almost immediately due to its low cost and potential public relations value.55

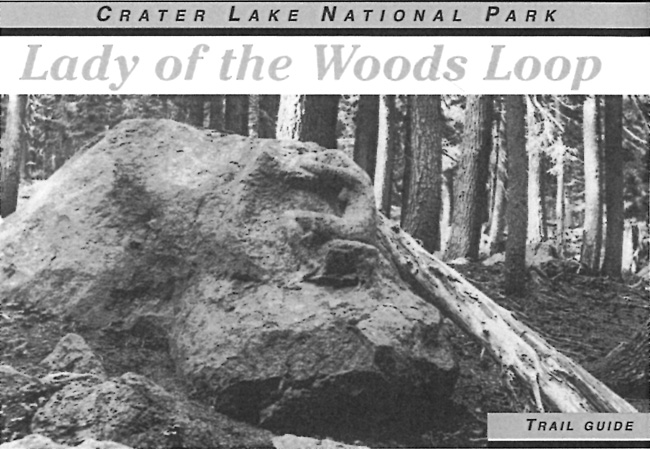

Thomson also recommended moving park headquarters from Annie Spring to "Government Camp" in Munson Valley, where, a few years earlier, the Corps of Engineers had kept their offices and staging area. As part of this shift in operations, the NPS built a short trail leading to a stone figure called the Lady of the Woods in 1924. This unfinished statue, sculpted on a boulder in 1917, had periodically received enough newspaper publicity to catch the attention of visitors traveling the road leading to Rim Village and Thomson saw no reason to discourage this interest.56

Both trail projects amounted to small undertakings in a park where Thomson stated "only four of our trails are much traveled."57 He did not identify which four, but noted in his report for 1925 that heavy spring slides required an unusual amount of work on Sparrow's trail to Crater Lake. It needed so much repair that the rebuilding practically exhausted the park's allotment for trail maintenance.58 Thomson omitted any mention of new trails in his report for 1926, though he mentioned that a fire lookout had been built on Mount Scott from U.S. Forest Service plans. Materials needed for construction were hauled to the site by pack animals over a trail some two miles in length that started from the Rim Road at Cloudcap.59

Thomson transferred from Crater Lake in early 1929, having witnessed substantial completion of the Crater Wall Trail the previous summer. With clearing and grading done by contract in 1927, the NPS found that the switchbacks needed to be widened and lengthened to permit travel by horseback. NPS engineer Ward Webber supervised a park crew to complete this work over the following summer. They also built retaining walls where needed, several parapets, and log seats at convenient intervals. Webber commented about placement of the benches, a first at Crater Lake, specifically on the care taken to permit visitors to enjoy "the play of colors on the water and the surrounding cliffs while resting."60

|

| Ranger in Llaos Hallway, about 1931. National Park Service photo. |

Finishing most of the construction on the Crater Wall Trail in 1928 came during the initial stages of redeveloping the sometimes bleak and dusty site of Rim Village, where visitor services with their associated impacts had long been concentrated. The trailhead was situated near a newly-built parking area, something largely intended for day use, as part of a larger plaza containing the concessionaire's cafeteria. The plaza still needed to be connected with other key features in Rim Village, such as the Crater Lake Lodge and Rim Campground. This could be accomplished by means of a roadway, but also through a network of walkways. Plans for pedestrian circulation at Rim Village centered on building a promenade eight feet wide and running some 2500 feet long (or roughly the distance between the trailhead and lodge), to be located along the edge of the caldera. Work on the promenade thus began in 1928 and continued over the next four summers. The NPS intended to concentrate foot traffic on the promenade and associated walkways (both of which were to be paved) as a way to harden the site, yet this allowed the agency to also take steps toward restoring native vegetation through planting. Officials also planned to use the promenade as a means to unify Rim Village, especially once masonry walls could be erected as a safety barrier on the side facing Crater Lake.61

While both the Crater Wall Trail and a promenade in Rim Village represented improvements to pedestrian circulation in an area where more visitors congregated than anywhere else in the park, they were not the only construction projects undertaken by the NPS at Crater Lake during the summer of 1928. Federal funds aimed at new buildings and roadwork continued to far outstrip those for trails and walkways, but more money paralleled another trend; that of annual appropriations for the park having almost doubled since 1925. It reached more than $62,000 in 1928, a figure meant to cover maintenance costs, utilities, equipment, and staff salaries.62 Most of the money spent on trail maintenance that year still went toward opening Sparrow's route to the lakeshore, just as work proceeded on finishing its replacement. Thomson, meanwhile, saw a need to "recondition" several other trails now that most had been in use for a decade. Without more funding dedicated to maintenance, however, their condition could deteriorate to a point where a full or partial reconstruction became necessary.63

|

| A section of the Sparrow Trail in the 1920s. Photo by Frank Patterson, author's files. |

By this time Thomson had given up his earlier idea for a trail up Llao Rock, one that might culminate with a fenced platform located some 2,000 feet directly above the lake. He thought it could be a "Mecca" for visitors, made accessible by walking a few hundred yards from the Rim Road, and an attraction that could "hold tourists for a while: too many now come, take a look at the Lake and depart."64 In his earlier refusal of the $1,600 initially requested by Steel for a trail down Kerr Notch, Thomson explained that such a development will not be used "except by the very few who might come in the East entrance, go down to the water's edge at the proposed trail, climb back in their cars and depart without seeing the Lodge, the Garden of the Gods [Godfrey Glen] or anything else." He also doubted that the view obtained of the Phantom Ship might equal that already available on the boat trips, much less whether a trail down Kerr Notch could be finished for the amount appropriated. Thomson also wondered about how to cover the maintenance expense brought about by slides along a new trail, as costs associated with opening a trail below Rim Village just seemed to escalate.65

|

| A planting bed along the promenade, Rim Village, in 1931. NPS photo in the National Archives, San Bruno, California. |

Expansion and Reconstruction, 1929-32

Trail projects received a relatively small share of the steadily increasing appropriations for construction and park operations that began in the latter part of the 1920s and which continued through much of the following decade. It is not surprising that trail mileage at Crater Lake increased during this period, as part of an unprecedented growth and development of park infrastructure in general, yet as one observer commented in 1932:

"I was told at the Park that little money will be given for trails because few people use the trails. It is more important to build trails for the few who have interest enough to use them than to build roads for the many..."66

Park employees nevertheless undertook a limited amount of trail construction, something that could usually be accomplished inexpensively in comparison to other kinds of infrastructure. One project came from the staff of three ranger-naturalists hired for the summer season of 1929. By the end of July they submitted plans for a nature trail to go through a wildflower "garden" located east of Park Headquarters in Munson Valley.67 This wetland, found on the lower slope of "Castle Crest" (Garfield Ridge), contains a rich variety of floral species native to the park and allows most visitors relatively easy access once the snow disappears. The NPS expended $140 to build a trail to the garden that summer, a project that included five log bridges, six "rustic" benches, and a number of aluminum labels for identifying the flowers.68 After the trail was repaired and rebuilt in several places the following year, ranger-naturalists began leading regularly scheduled hikes on it.69

Adding new trails like one to the Castle Crest Garden expanded recreational opportunities at the park but did not change what had long since emerged as the top priority for pedestrian circulation. The goal of easy visitor access to Crater Lake seemed to have finally been achieved in early July 1929, when Superintendent E.C. Solinsky accorded the honor of being the first to reach the bottom of the Crater Wall Trail on horseback to Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur. Yet getting the trail open the following year involved removing several slides of mud and rock on the switchbacks as well as repairing damaged tread, so the NPS programmed a post construction project for 1931 in an attempt to address these problems. In any event, reverting to the Sparrow Trail appeared to be out of the question since park crews had already obliterated portions of the route to deter any subsequent visitor use.70 In reporting on the post construction project in the fall of 1931, NPS engineer W.E. Robertson pointed to inherent problems posed by unstable slopes, the number of switchbacks, and an exposed boat landing situated in deep water.71 By that time the superintendent's view of the trail had soured considerably, writing that opening and maintaining it was out of all proportion to the original construction cost, stating the NPS had to practically rebuild the entire route that season. He argued for the trail to be relocated, not only due to the ongoing expense, but also to lessen the chance of visitor injuries caused by loose rocks that could tumble over a long series of switchbacks located one over another.72

Landscape architects began playing a more direct role in the design of roads and trails by this time, though the engineers continued to take the lead in location work as well as provide direct supervision of park crews during construction. The landscape architects furnished site plans and could also make adjustments in the alignments located by engineers as part of making development better fit the park setting. With the re-development of Rim Village underway by 1929, Ernest Davidson and other landscape architects from the NPS office in San Francisco made regular visits. Davidson came to the park in July of that year to stake some walkways intended to connect the still unfinished promenade with a roadway running through Rim Village.73 Solinsky and other NPS officials agreed that paved walkways varying in width between four and six feet were necessary for handling greater numbers of visitors at the park's main developed area, but so was the addition of a better trail to reach its most popular viewpoint.

|

| The promenade and roadway near the entrance to Rim Village, about 1932. National Park Service photo. |

One of Davidson's colleagues, Merel Sager, spent much of the 1930 summer season at Crater Lake designing and then overseeing construction of the Sinnott Memorial located just below the promenade. A beaten path had formerly followed a short ridge down to Victor Rock, where visitors regularly gathered some 900 feet above the lakeshore, but the Sinnott Memorial's construction on that site pointed to the need for a wider and safer route. Sager designed the Victor Rock Trail to start on the promenade just west of Kiser's Studio and run about 200 feet to the parapet of the Sinnott Memorial. Opened in 1931, the trail was paved like the promenade and walkways nearby, but included two flights of stone steps, tread eight feet wide, and lined on both sides by stone masonry walls.

For projects on longer trails, such as reconstructing the one up Garfield Peak, Sager made adjustments in alignment and grade in consultation with Robertson and Solinsky. Intended to replace the earlier route built by Sparrow's crew, the NPS intended the realignment to provide a wider tread surface for horses and pedestrians, but also reduce the trail's average grade to 15 percent. The NPS spent $4,000 that summer on the lower half, building it four feet wide. Sager commented that the trail's visibility as seen from below had been kept to a minimum by using dry laid rockwork for fill sections and he mentioned introducing stone at irregular intervals on the trail's outer edge in order to reduce a line that could be both visible and uniform.74

|

| Benching on a portion of the Garfield Peak Trail, 1931. National Park Service photo. |

The NPS spent another $5,000 in 1931 to widen the lower portion another two feet after first building the slightly longer upper section six feet wide. Robertson explained that six feet allowed for operation of a mechanical oiler intended to reduce dust on the trail. Crews also built smaller trails between two and four feet in width at several prominent viewpoints. These totaled roughly 800 feet in length and included rest stations with stone seats, all "carefully selected for the beautiful and interesting views to be had of the lake and surrounding country."75 In addition to the rest stations, Solinsky also commented on the precautions taken to protect vegetation along the new route, measures which included leaving at least one live whitebark pine in the trail. Like Robertson, he supported applying road oil to reduce dust, since a "very large" percentage of visitors were seen to take the route.76

|

| Portion of the Watchman Trail that has been oiled and shows edge treatment with boulders, 1932. National Park Service photo. |

Only the Garfield Peak and Crater Wall routes were oiled at first (a move intended to prevent losing the tread surface during rainy weather or from melting snow), but the NPS expanded this practice upon completion of trails to the Watchman and Discovery Point in 1932.77 Planning for a trail to the Watchman's summit started in 1931, when Sager and Robertson agreed that the location of a temporary route used to haul construction materials for a new fire lookout should be utilized as much as possible for a permanent hiking trail.78 When work on the permanent trail began the following summer, Sager wrote that the crew did the same good work as had characterized construction of the Garfield Peak Trail.79

The new trail to Watchman started from a point where the old Rim Road crested on a southwest slope as it went around the peak and from there, the summit trail ran some 2,750 feet with a maximum grade of 15 percent.80 Intended to be five feet wide except at switchbacks, the trail incorporated features similar to those on the Garfield Peak route. These included dry-laid retaining walls, considerable benching, and a couple of stone seats intended as rest stations. The crew also placed singular rocks on its outer edge at irregular intervals as a way of minimizing the trail's visual impact as seen from a distance, though the practice did not extend to a section of the old Rim Road which effectively became part of the trail. Its trailhead also migrated down to the Watchman Overlook because construction of the new Rim Drive followed a lower line around the peak than the old road, which the NPS subsequently closed to vehicle traffic.81

With construction of the new route to Watchman essentially completed in three weeks, trail building activity in 1932 shifted toward improving the linkage between Rim Village and Discovery Point. This project covered a total of 1.5 miles, of which more than half (4,280 feet) consisted of new trail. The staked location worked out between Robertson and Sager kept grades under 12 percent, but did require some benching and other rockwork. They utilized portions of the existing trail, originally constructed when Sparrow served as superintendent, though it was widened to five feet to match the new sections. In all, construction lasted barely three weeks and concluded with oiling the trail.82

Robertson predicted that the Discovery Point Trail might prove to be quite popular, something helped by the fact that the ranger-naturalists in the 1930s promoted use of this route in the day's waning hours. For a time it became officially known as the "Sunset Trail," a route where hikers could start at the trailhead located on western end of the promenade and obtain views along the rim that were otherwise screened by trees and topography from the sight of motorists traveling on Rim Drive.83 The section receiving the most use, however, served as a link between Discovery Point (the place where a party of miners in 1853 supposedly "discovered" Crater Lake) and a newly built parking lot below it. Part of the use, at least initially, came from the ranger-naturalists leading car caravans around the rim which stopped there, as they also did at the Watchman Overlook. The actual "observation stations" such as Victor Rock, Discovery Point, and Watchman where the naturalists could give talks, were meant to be reached by trail, though this took time and the Rim Caravan as an educational offering eventually fizzled. It remained alive long enough to give rise to other, more informal, trails leading from points along west Rim Drive. One accessed the top of Devils Backbone from a small parking area, while another went to the top of Merriam Point from the junction of Rim Drive and the North Entrance Road.84

|

| Crew building the Watchman Trail, 1931. National Park Service. |

Construction of a new trail to the top of Wizard Island resulted from a visit by NPS senior park naturalist Ansel F. Hall, who had come to the park in July 1931 from his duty station in Berkeley, California. Hall and an assistant used surveying equipment and stakes to lay out a trail on an eight percent grade, intending it to replace an earlier, but steeper, route. This had a direct connection to the naturalists starting a ranger-led boat tour of Crater Lake that summer, something which included a hike to the top of Wizard Island.85 They built what Hall called the "spiral return trail" without clearance from Sager or the other landscape architects, but with the consent of Superintendent Solinsky, who evidently thought its attributes outweighed being more readily seen from the rim. At 30 inches wide, the drifting of cinders quickly began to obscure the line even during the first season. Put on the defensive, Hall and other naturalists pointed to its value in conducting guided walks on the island; not only were marked changes in flora evident on the cinder cone depending upon aspect, but a circular route made tree patterns and geological formations more striking.86

|

| A ranger and visitors at Merriam Point, 1936. Part of the "spiral return trail" is visible in the distance. Photo by George Grant, NPS Historic Photograph Collection. |

Hall also marked a trail along the shoreline to what was later called Fumerole Bay, though the route went from the summit crater down to the water along the island's north side. It still lacked a connection with the boat landing at Governors Bay, something recommended in a report written the following summer by Worth Ryder, an art professor from the University of California. At the behest of cooperating scientists who served as volunteer advisors to the NPS, Ryder made a series of suggestions as part of studying the park's aesthetic qualities so that ways could be found for visitors to better appreciate them. His report of August 1932 mentioned new trails in several places, marking the first time that anyone outside the NPS provided suggestions about what additional routes might enhance the experience of visitors.87

Among Ryder's recommendations was for building a trail from Cleetwood Cove to the rim above it, something that he believed could make possible a combination boat trip and road tour. The NPS took no action on that idea, nor did it act on his suggestion to construct a trail from Garfield Peak to Sun Notch. Ryder may have had some influence in urging that Rim Drive be kept at least 200 yards away from the rim at Sun Notch, a site that he considered the most important viewpoint in the park.88 In emphasizing that great care had to be taken in designing a pedestrian route along that portion of the rim, he went so far to urge that every foot of potential trail be studied prior to construction since Sun Notch could be made into "the most delightful scenic wonder of the entire Park."89

No such study followed from Ryder's recommendation, though a group of faculty members from the University of Oregon took up the question of how visitors could best appreciate nature at Crater Lake the following year. This eventually resulted in a collection of short reports and observations made throughout the park over the course of several summers and included some references to existing trails, insofar as they might contribute to visitor understanding of scenic features.90 Unlike Ryder, the UO authors did not suggest where to build new trails or which of the existing routes to reconstruct. For the most part, trail projects continued to emerge on an ad hoc basis through the superintendent or one of his key subordinates, but on the whole represented only a small fraction of the undertakings aimed at improving park infrastructure during the decade of the 1930s.

Nevertheless, trails could enhance both the park's recreational potential and factor into larger operational goals like suppressing wildfires in the backcountry. As an example, Chief Ranger Bill Godfrey reported in July 1930 that a NPS crew built a trail from the base of Crater Peak to its summit. He described it as being of a standard width and holding a grade of roughly 15 percent in order to reach the top, which Godfrey saw as valuable as an observation point during fire season.91 The new trail climbed the peak's north side by heading west with an elongated curve so that the summit could be reached on a steady grade without switchbacks. Godfrey made no reference to any earlier trail, though he mentioned following "an old wagon road" to reach the base of Crater Peak; most likely the route built during Sparrow's tenure as superintendent.92

Construction of the trail to Crater Peak came in conjunction with building a network of access roads to aid with fire suppression. In this case, the "motorway" or "truck trail" started from the Rim Road near Tututni Pass and was intended to allow park crews to reach places where lightning strikes had caused fires. Limited to administrative use for vehicular travel, these roads were routed in order to minimize the time needed for park crews to reach smokes or wildfires on foot. They could also form part of the hiking or horseback route to a backcountry destination, as at Crater Peak. Although not intended as trails, some of the motorways at Crater Lake received use by visitors in the absence of routes engineered and built for pedestrians.

Motorway construction began in 1930 after location work was initiated with compass surveys, then followed by field drawings and stakes that set road locations.93 This effort took place at Crater Lake and other national park units once the NPS received dedicated funding for fire suppression activities in 1929. It eventually resulted in 130 miles of motorways in the park (a figure which almost doubled that of paved highways at Crater Lake) with grades ranging from flat to ten percent. Built with a bulldozer, the operators simply scraped litter down to mineral soil and pushed material to one side. This created a swath 12 feet wide after some clearing of trees, but inadequate provision for drainage and lack of maintenance meant that sporadic work was needed to keep the motorways serviceable for NPS use.94

The motorway toward Crater Peak included some new construction where Godfrey and others thought the "wagon road" to be problematic or too steep. It more or less followed the older route with some reconstruction to the base of Crater Peak, along the ridge separating the Annie Creek and Sun Creek drainages.95

|

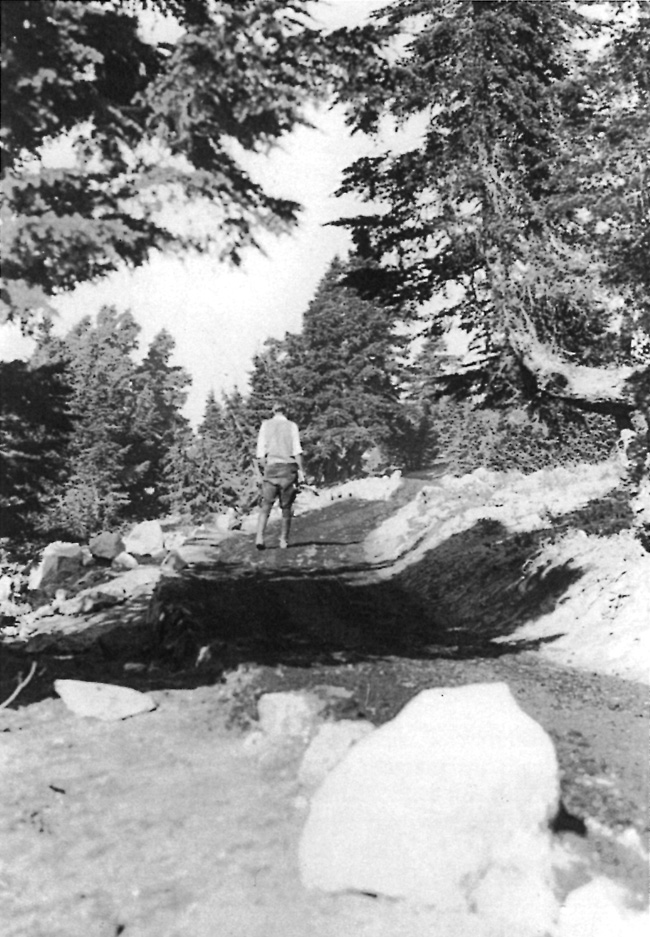

| Map showing several motorways in the southwest quadrant of Crater Lake National Park, author's files. |

Hikers and equestrians traversed only that initial portion of 1.5 miles in order to reach the trail leading to the summit, though the motorway was extended southward to the boundary over the next three summers. This came in accordance with Godfrey's desire to provide administrative access to the park's southeast corner, where it could be linked with other motorways.

Godfrey also reported on reconstruction of the Union Peak "Trail" in the summer of 1930. He made a distinction between the trail (for the most part a road since its initial construction in 1918) and a motorway. This was due to the former remaining open to vehicles driven by visitors, even though down trees had prevented such use for several years prior to 1930. With rocks and stumps removed, in addition to grading done to fill in high centers, the "trail" was reopened that summer from a turnoff located along the West Entrance Road to the base of Union Peak. It came with some realignment of the older route, including the addition of more than a half mile from the end of the "trail." The extension was to create a linkage, if only for the NPS, with a new motorway built to cross the Cascade Divide from the South Entrance Road. This one traversed Pumice Flat on its way toward Union Peak and could form something of a loop, taking in several miles of highway to complete the circuit.96

Building motorways through the park's backcountry proceeded apace in 1931 and 1932, despite NPS Director Horace Albright expressing some hesitancy to Solinsky about allotting funds for their construction.97 The possibility of cost overruns concerned him the most, so Albright urged the superintendent to provide more oversight of these projects now that they were funded from appropriations earmarked for the relief of high unemployment. With some 75 miles of motorways already constructed by the summer of 1932 in the park, Albright decided there was enough justification to continue building them. While the motorways overtopped earlier roads or trails in some places, most of the mileage held little interest for hikers and equestrians. This was largely due to the motorways being located without reference to views or necessarily leading to points of interest.

The NPS attempted to remedy these shortcomings, at least in part, by creating a network of bridle trails for equestrians between Annie Spring and Rim Village. Like the motorways, their construction began in 1930. Eleven miles of equestrian paths were built by the end of that season, starting with a trail down Dutton Creek from Rim Village that incorporated some of the nineteenth century wagon route.98 It was to form part of a large loop, one that continued toward Annie Spring by way of a pass used by the earlier wagon route to cross the watershed divide. From Annie Spring the bridle path ran north of the highway toward Munson Creek, and then to Park Headquarters where it began the climb on the lower slopes of Castle Crest to Rim Village. With one exception, other bridle paths branched from this larger loop. One of them linked Dutton Creek with Park Headquarters by climbing over Munson Ridge and could thus split the larger loop into two smaller ones. Another bridle path diverged from the main loop near Godfrey Glen and formed a smaller circuit in order to reach an area located only a short distance from the highway. The lone exception to utilizing the larger loop connected the top of Garfield Peak with the old Rim Road, but was routed east of the ridge forming Castle Crest.99

|

| A section of one bridle trail, 1931. National Park Service photo. |

In all, park crews built a total of approximately 13.5 miles of bridle paths during the seasons of 1930 and 1931 for $4,000. As with other trails, Sager worked with the engineers to approve final locations and any changes needed during construction. NPS engineers Webber and Robertson noted the numerous inspections by the Landscape Division in their completion report and included one photograph of a typical section.100 It showed a trail four feet wide on a moderate grade sloped slightly inward to better expedite drainage. This reflected the use of standardized approaches meant to minimize the need for maintenance or future reconstruction, yet also made a trail better fit into the park setting. Completion of the bridle paths more than doubled the mileage of "standard" trails at Crater Lake, but it also represented the most coherent effort made so far toward bringing about some type of system through interconnection and loops.

The bridle paths were one, albeit small, piece of a larger improvement program in the park, one funded at the unprecedented level of $177,000 in 1930. This funding came in response to the continuing rise in annual visitation (to a record setting 157,000 in 1930 and then 175,000 in 1931), but also the Hoover Administration's aim to relieve unemployment caused by the onset of the Great Depression. Building infrastructure to support the national parks found favor with President Herbert Hoover and Congress, so NPS budgets received funding for more projects than at any time since the agency's creation in 1916. Bridle paths had already appeared in several other national parks, with this type of trail tending to emphasize recreational riding over necessarily reaching specific points of interest. The paths at Crater Lake were signed for visitors, but the NPS otherwise did little to promote their use by equestrians. The Great Depression's onset terminated any plans the park concessionaire might have had to offer horse rentals, so equestrian use was limited to the few who could bring riding animals with them. Hikers occasionally traversed portions of these trails, though with day use visitation increasingly dominant at Crater Lake, their interests tended to center on the rim rather than the largely forested areas traversed by the bridle paths for the time they had available.

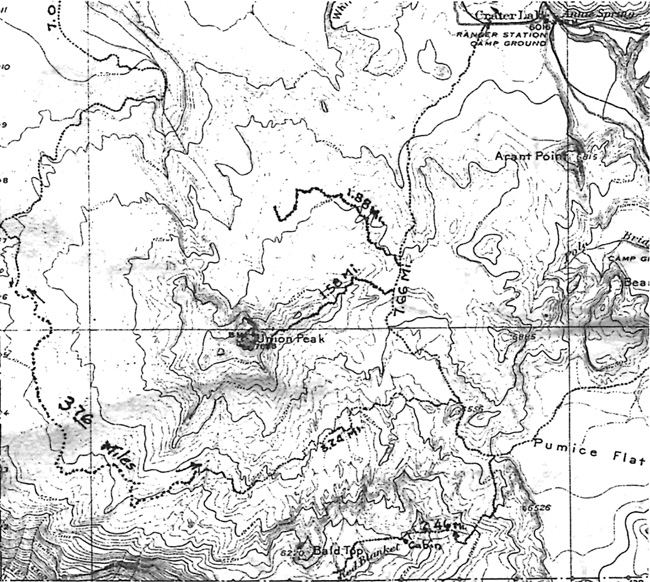

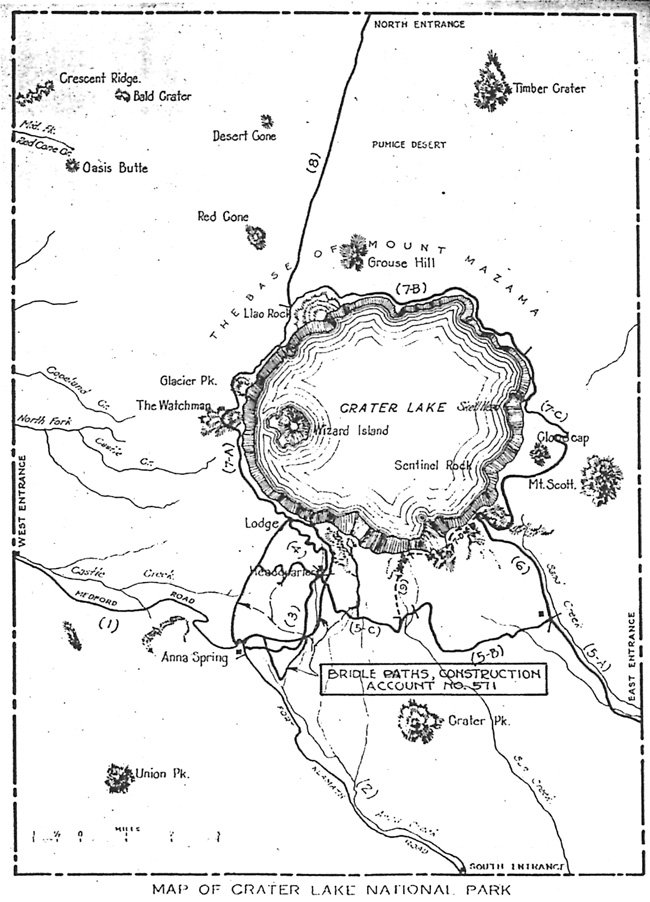

|

| Map showing the location of bridle trails, 1932. Note the Munson Valley area. National Park Service. The numbers indicate roads. |

New Deal Projects, 1933-41

An infusion of project money aimed at building park infrastructure continued to reach Crater Lake during the first eight years of the Roosevelt Administration, fueled by the need to put people to work. Nevertheless, a perception that most of the necessary trails had already been built or reconstructed by that time meant that the park's inventory of pedestrian routes grew slowly during the last half of the 1930s, with much of the funding for trails going toward maintenance while plans for any new trails usually received low priority for funding. Even so, a few projects for new trails received funding through a job training program called the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and an agency that hired temporary workers known as the Public Works Administration (PWA).

CCC enrollees from a camp at Lost Creek built a trail to the lookout on Mount Scott in 1933. Sager referred to it as a horse trail, one originally intended for packing supplies to the lookout a little more than two miles away. As a National Park Service "standard" trail four feet wide, its maximum grade did not exceed 15 percent.101 This new route superceded the longer trail from Cloudcap, since the road circuit around the lake was realigned to employ a long sinuous curve that got closer to the base of Mount Scott. Once contractors completed grading this section of Rim Drive, visitors could now start about a mile closer to Mount Scott than formerly. The trailhead maintained a weak sense of arrival, however, since the initial section of trail involved a quarter mile of travel over an unpaved track resembling a motorway.

|

| Ranger on the Mount Scott Trail, 1933. NPS photo in the National Archives, San Bruno, California. |

Enrollees from the same camp may have worked on reconstructing or improving portions of the old "motor trail" leading to Sun Notch that summer, though records for the project are sketchy. A more ambitious undertaking was proposed for the 1934 season involving construction of a horse trail from a point on the old Rim Road where it crossed Sun Valley, then to Sun Notch, and over to Garfield Peak. The idea for a prospective link to Garfield seemed to come from Superintendent Solinsky, once NPS Director Horace Albright had decided against locating Rim Drive next to the caldera at Sun Notch.102 The NPS landscape architects objected to any proposed trail going past Sun Notch, so the effort shifted to building a route that could link Garfield Peak with Vidae Falls. Enrollees started construction of the trail where Vidae Creek crossed the old Rim Road in August 1934, but it only went about a mile toward Garfield Peak by October, and terminated at an overlook located above the falls.103 Another group of enrollees began building a trail from Lost Creek toward Vidae Falls that season, though the project was quietly abandoned after its initial stages. The only other CCC trail project of 1934 consisted of a short trail approximately six tenths of a mile along Lost Creek.104

|

| Benching on a section of the abandoned Vidae Falls Trail, 2010. Photo by the author. |

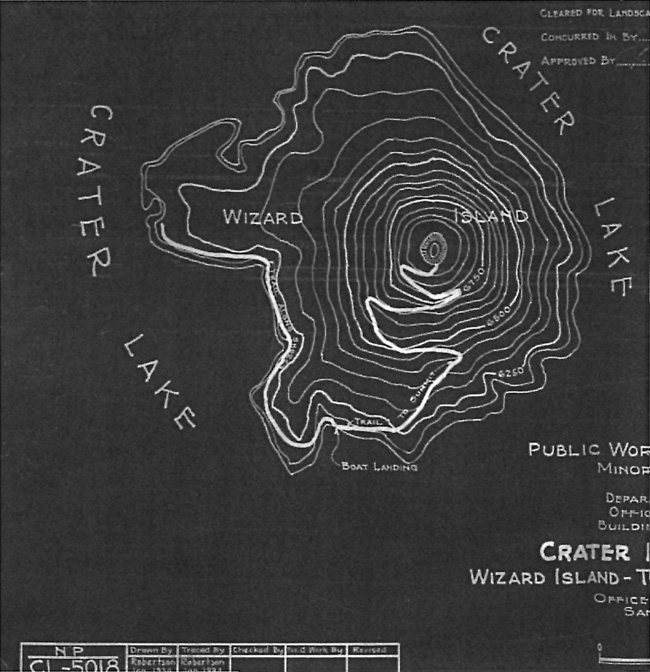

Temporary employees hired by the PWA also contributed to trail improvements beginning in 1933. By early fall of that year, $450 had been spent to make the Crater Peak Trail some 4,000 feet long, 30 inches wide, and provide a maximum grade of 15 percent. At the same time, double that amount of PWA funds went toward improving the Union Peak Trail. It had the same length and maximum gradient, but a full three feet of width upon completion in October.105 A PWA crew also undertook building yet another trail on Wizard Island the following year, this one utilizing three switchbacks on the south side of the cinder cone.106 Finished by September 1934, the trail extended 5,500 feet from the boat landing on Governors Bay to the summit crater. The project also provided a connection with a shoreline trail to Fumerole Bay, one pioneered by Ansel Hall in 1931. This project came amid debate over whether Hall's "spiral return trail" should be retained as part of ranger-led trips on the island since it circled the cone and allowed visitors to note differences in vegetation based on their aspect.107

Trail maintenance became a CCC responsibility at Crater Lake during the New Deal, though this activity did not take place on an annual basis except for work to open the Crater Wall Trail, a task usually involving considerable snow removal. Unusually heavy thunderstorms in July 1935 also carried thousands of yards of material over the trail, requiring much additional work by CCC crews.108 The other project for the summer of 1935 involved a group of enrollees maintaining and repairing 18 miles of horse trails in the park. This figure included the 13.5 miles of bridle paths built by NPS crews in 1930-31, but presumably other trails (such as the one to Mount Scott) receiving more use.

|

| Public Works Administration map of the Wizard Island Trail project, 1934, author's files. |

The CCC did not construct any new trails at Crater Lake that summer, though several proposals had been floated by the NPS. One project had been initially programmed, that of building a one mile trail to the top of Red Cone from the motorway below it, but this prospect fizzled in the face of other priorities.109 The NPS regional geologist visited Crater Lake that summer and suggested that the CCC construct trails to several points of geological interest.110 One of these proposals persisted on the main park planning document (a master plan) for more than a decade and consisted of a trail some two feet wide leading from the North Junction to Llao Rock. The project remained a low priority, however, and was never undertaken.111

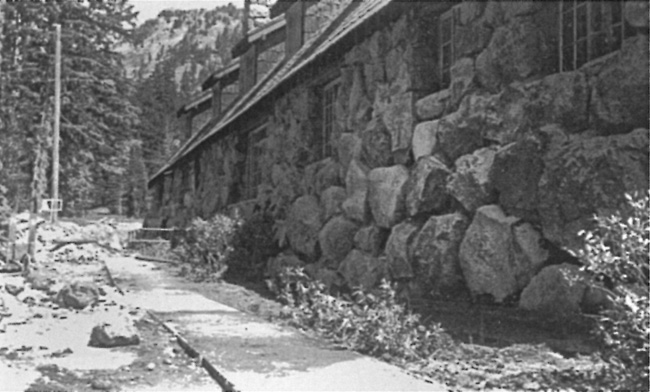

|

| Crater Lake National Park. Footbridge and Ranger Dormitory, 1936. NPS photo by Francis G. Lange, included in volume 1 of Park and Recreation Structures (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1938), 183. |

Apart from maintenance (which included snow removal, clearing, and oiling of the most heavily used pedestrian routes), trail improvements at Crater Lake were limited to the area around Park Headquarters in 1936. CCC enrollees built a footbridge over Munson Creek, one designed by resident landscape architect Francis G. Lange. It replaced a more modest structure behind the Ranger Dormitory on the Lady of the Woods Trail, a route they also surfaced that trail with gravel over its entire length. They maintained and improved the existing trail through the Castle Crest Wildflower Garden, as well as a trail that linked the popular wetland area with the newly completed Administration Building.112

By 1937, some components of the park's "system" met with criticism from NPS staff. Lange's report on grading a portion of Rim Drive contained an observation that the old "motor trail" to Sun Notch could be seen within a thousand feet of the new road. In keeping with the NPS practice of removing old roads visible from Rim Drive, he suggested obliterating the "trail" and noted that plans now called for its removal.113 Wildlife technician E. Lowell Sumner, meanwhile, protested the use of a small tractor for oiling the Garfield Peak Trail after his field visit in July 1937. He attributed the "surprising" width of this and several oilier trails to the machine used to oil them. At six feet wide, however, such a trail actually discouraged use by hikers who had since shortcut the "highway" by making a path of their own with a width of some 18 inches. Sumner noted that the wider trail had an "aggravated tendency" toward bank erosion and often led to situations where work crews more often undermined important trailside trees by chopping away lateral roots. In his view, trails of that width conveyed "no feeling of isolation, no feeling of primitive nature no matter how rugged the surroundings into which they are introduced."114

Beyond opening the park's most heavily used pedestrian routes, the CCC placed a total of 20 log benches along the Garfield Peak and Crater Wall trails that summer. These features utilized logs cut in half and further divided into sections of six feet, then placed into smaller supports on the ground that were notched to hold the seat.115 Enrollees then added two "rock seats" to this number, stone features that were presumably similar to the benches located along the Watchman Trail in 1932. The CCC also completed the final stage of building walks at Rim Village that summer, with some of the enrollees focusing their efforts on the parking area south of Crater Lake Lodge, in addition to linking a new comfort station near the plaza with visitor parking. They also added a walk at Park Headquarters, effectively connecting the Ranger Dormitory with the Messhall.116

A small number of enrollees took on reconstructing the Castle Crest Wildflower Trail in 1938, a project that included several major changes to what had been built nine years earlier. The most conspicuous involved a new trailhead, now that contractors were grading the last section of Rim Drive. Enrollees moved the trailhead to a new parking area located along the road, but also obliterated several confusing cross trails and moved a telephone line that had formerly crossed the "garden." They repaired log footbridges, built rock steps in several spots, and placed larger flagstones where the trail crossed wet ground.117

|

| Walkway at rear of the Ranger Dormitory, 1937. NPS photo by Francis G. Lange in the National Archives, San Bruno, California. |

Funding and enrollment in the CCC had declined to where one of the two camps in the park was eliminated for the 1939 working season. Just as before, priorities for trails consisted of opening the Crater Wall Trail and maintaining the most heavily used routes, but enrollees did not undertake any new construction. They instead placed a wooden footbridge across a small stream near the Lady of the Woods and a virtually identical structure over Munson Creek between the Ranger Dormitory and three employee residences located above the dormitory. Enrollees also continued with a project started in 1937, which involved replacing metal signs with hand carved markers designed by Lange at various places frequented by visitors. Included in the program were signs at trailheads such as those for Lady of the Woods and Mount Scott.118

|

| Footbridge across Munson Creek, Park Headquarters. NPS photo by Francis G. Lange in the National Archives, San Bruno, California. |

Another trail sign came into existence once the NPS and USFS agreed on how to indicate a change in jurisdiction where the Oregon Skyline Trail crossed into the park from the Rogue River National Forest. This did not mean that a viable trail traversed the park, even if the NPS publicly supported the idea of a larger route extending from the Columbia River to the California state line. Although the initial concept of a Skyline route in 1920 had more to do with a road connection between Mount Hood and Crater Lake, Forest Service personnel worked steadily throughout the following two decades to build and connect trail segments in the high Cascades. A small band of outside supporters liked the idea and helped the Forest Service publicize the Oregon Skyline Trail with maps and leaflets, but they also began to think in terms of a backcountry route only available to hikers and equestrians that might link the border with Canada to the one shared with Mexico.119