|

Dayton Aviation

What Dreams We Have The Wright Brothers and Their Hometown of Dayton, Ohio |

|

Chapter 1

Historical Background

When the Wright family moved to Dayton in 1869, the Dayton region had already experienced a long history. For centuries, inhabitants and nature had shaped the region which became the Wrights' home for much of their lives. Today, the glacial landscape contains prehistoric mounds and earthworks, within the modern city of Dayton.

Approximately 12,000 years ago, the Wisconsin glacier receded northward and created a land ready for plant and animal growth. These glacial ice sheets with irregular fronts filled the Teays Stage Hamilton River bed, which is now an underground river, and shaped the landscape in the present-day Dayton area. In addition, glacial till carried forward by the ice sheets was deposited, creating such noticeable features as the Wisconsin moraine, south of Dayton. [1]

After the glacial ice retreated, Paleo-Indians inhabited the region. These nomadic people followed big game, such as mammoths and great bison, northward as the ice melted. The distribution of recovered artifacts from the Paleo-Indians in what became Ohio shows that they resided in the central counties of Ross, Pickaway, Franklin, and Licking. They also roamed what became the Dayton region in Montgomery County, but in fewer numbers. [2]

In approximately 8,000 B.C., the climate grew warmer and dryer, and Native Americans adapted by creating new ways of living. Archeologists denoted these new, post-ice age life-ways as the Archaic Tradition. The Archaic peoples migrated throughout Ohio following movements of game animals and ripening food plants. They resided in semi-permanent encampments to which they returned regularly according to seasons. As with the Paleo-Indians, these movements led the Archaic people into the Dayton region, but in small numbers. Around 1,500 B.C. the Archaic tradition began evolving into the Woodland tradition. [3]

When Europeans began to explore the Miami Valley and surrounding areas in the eighteenth century, they encountered current Native American inhabitants as well as the artifacts of earlier cultures. The most noticeable of these were an estimated ten thousand earthen mounds and earthworks scattered throughout the region from the Woodland tradition. The earthworks represented three types. Some mounds were conically shaped and ranged in height from a few yards to ninety feet. The largest of these cones in Ohio was located in Miamisburg; it measured sixty-eight feet high, 852 feet in circumference at the base, and contained 311,353 cubic feet of soil. Early excavations showed that many of these conical mounds were used for burials. Other formations, located in valleys, were geometric earthwork features, such as squares, circles, and octagons, and served an unknown purpose. Similar to the geometric earthworks were "forts," dating from 100 to 400 A.D., constructed on hilltops overlooking valleys with walls of earth sometimes reinforced with stone. [4]

MIAMISBURG MOUND (Courtesy of Dayton and Montgomery County Library) |

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, theories as to the origins of the mounds and earthworks abounded. Archeological knowledge evolved into the current belief that two cultures, known as the Adena and Hopewell, produced the earthen features. The Adena Culture preceded the Hopewell Culture, but the two groups overlapped for several centuries during the Woodland tradition, approximately 1,000 B.C. to 400 A.D., and possessed many similar characteristics. Both the Adena and Hopewell were part of the Woodland tradition whose defining traits included the use of pottery and a combined hunting, gathering, and gardening subsistence. In addition, both were cults of the dead. [5]

The Adena, among the earliest mound builders in North America, began to emerge as a culture in 1000 B.C. and vanished by 100 A.D. Located within a 300-mile diameter area centered in Chillicothe, Ohio, the culture was named for the first sites excavated on the grounds of Adena, Thomas Worthington's estate near Chillicothe. The most outstanding feature of the Adena in reference to previous populations are their burial practices. Individuals were buried either single or in groups inside conical mounds; the bodies placed on bark covered earth or in shallow pits and covered with logs or deposited as bundle burials or cremated. Late in the Adena period, some individuals of note were buried in elaborate log tombs inside the conical mounds. These burial mounds were frequently constructed in groups with a large circular earthwork located nearby. Most Adena burials included offerings ranging from pottery, blades, drills, awls, scrapers, or pipes in the simpler burials to food, trophy skulls, antler headdresses, effigy pipes, masks, mica, and copper artifacts in the most elaborate burials. The most exotic burial offerings indicate the existence of trade contacts including such locales as the Gulf Coast of Florida, North Carolina, and areas north of Ohio. [6]

Late Adena burials, fewer in number than in the early and middle styles, were characterized by the addition of elaborate log tombs inside the conical mounds. These burial mounds were frequently constructed in groups with a large circular earthwork located nearby. Each burial included offerings more elaborate than those associated with earlier Adena burials and consisted of new types of artifacts including food, trophy skulls, antler headdresses, effigy pipes, masks, mica, and copper artifacts. Many of these objects were constructed from resources obtained from trade networks that included contacts in Florida, North Carolina, and areas north of Ohio. [7]

The Adena residential complexes identified in Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and West Virginia all included burial mound construction and ceremonies. Adena residences were circular log houses made of posts and covered with mats woven from grass and reeds, with thatch roofs. The Adena villages were small, consisting of two to five houses; clusters of these villages were distributed over a wide area. The Adena gardened, but little evidence has been uncovered to document this. Archeologists uncovered particles of pumpkins and squash in 1938 at Florence Mound, Pickaway County, Ohio and unearthed pumpkin rind at the Cowan Mound in Clinton County, Ohio. [8]

Several Adena burial mounds were located within the Miami Valley near Dayton; the largest and most well known was the Miamisburg mound previously mentioned. In addition, within Wright-Patterson Air Force Base six mounds attributed to the Adena were located in the memorial park on Wright Brothers Hill, in Bath Township, Greene County. The mounds at Wright Brothers Hill vary in dimension from 1.7-feet high and twenty feet in diameter to 4.2-feet high and fifty feet in diameter. In August 1939 a test pit dug in one of the smaller mounds by Dr. Henry P. Shetrone, director of the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society and professor of archeology at The Ohio State University, revealed bones buried six to eight inches under the surface. No other investigations were conducted at these mounds. [9]

The second culture in the Woodland Tradition, the Hopewell, appeared around 200 B.C. and vanished by 400 A.D., coexisting in some areas with the Adena for approximately 500 years. There were two primary centers of Hopewell activity: the areas of the Scioto-Muskingum-Miami River system in southern Ohio and the Mississippi-Illinois River system in Illinois, but regional variations of the Hopewell tradition have been identified throughout the eastern United States, from Florida to Michigan, North Carolina to Kansas. Similar to the Adena, the Hopewell constructed earthen mounds, although they were more complex and elaborate. In addition to burial mounds, the Hopewell constructed geometric earthworks and hilltop enclosures either in conjunction with burial mounds or individually. [10] The interaction sphere of the Hopewell expanded from that of the Adena to include such raw materials as prized flint from South Dakota, obsidian from the Rocky Mountain region, and galena from Missouri. The Hopewell cultural tradition ended by 400 A.D. Populations aggregated into larger settlements after the decline of the Hopewell mortuary complex. These Late Woodland populations sometimes buried their dead in the tops of the mounds constructed by the Adena and Hopewell without the elaborate ceremonialism evident in the earlier Woodland cultures. Between 1000 and 1200 A.D., the Fort Ancient Culture emerged and settled in the Middle Ohio Valley. One of the first cultures to establish subsistence farming, these people also resided in permanent villages. Usually 200 to 600 individuals lived in a village which was the focus of economic, social, and ceremonial activities. Each village functioned independently, although similar characteristics in ceramics revealed interaction between the villages. The Boonshoft Museum of Discovery [11] excavated and maintains a Fort Ancient site, now called Sun Watch Village, [12] south of Dayton. [13]

In addition to the Fort Ancient, new Native American cultures began to develop and settle in the area. The emerging cultural groups included the Miami, part of the Algonquian language group, who resided in the Miami Valley starting around 1700. The majority of the Miami were driven out of the area by the more warlike Shawnees by approximately 1780. These Native American groups did not reside in what is now Dayton although they used the surrounding area as their primary hunting ground. The major trails in this region were located along the waterways. [14]

The first known European explorers in the region were from France and England. One of the earliest explorers to reach the confluence of the Great Miami and Mad Rivers was Christopher Gist, sent by the Ohio Company to survey its lands. Virginians formed the Ohio Company in 1748 as a check against French settlement and aggression. The Ohio Company received a grant of 200,000 acres at the forks of the Ohio River from England's King George III. Gist traveled north from the Ohio River in 1751, and was in the Dayton region by February. In his journal Gist recorded this favorable description of the area:

...fine, rich level Land, well timbered with large Walnut, Ash, Sugar Trees, Chaerry Trees &c, it is well watered with great Number of little Streams or Rivlets, and full of beautiful natural Meadows, covered with wild Rye, blue grass and Clover, and abounds with Turkeys, Deer, Elks and most Sorts of Game particularly Buffaloes, thirty or forty of which are frequently seen feeding in one Meadow: In short it wants Nothing but Cultivation to make it a most delightfull Country... [15]

Despite Gist's exploration and favorable reports, the land that became Dayton was not immediately settled by colonists. [16]

During the last half of the eighteenth century, the British and the French fought for control of the Ohio Valley. Being the first Europeans to settle in the area, the French claim relied upon the rights of discovery and possession. The British claim rested in the colonial charters of Virginia, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, which defined the colonial boundaries as stretching from sea to sea. With both countries and the Native Americans professing rights to the territory, many conflicts occurred. [17]

The Europeans took official steps to ensure possession of the land. In 1749, Frenchman Célèron de Blainville [18] led an expedition authorized by Comte de la Galissoniere, Governor of New France, to travel down the Allegheny and Ohio Rivers in a show of French force to the Native Americans and the British traders. During this expedition, Célèron placed, at the confluence of each river he passed, including the Great Miami, a lead plate claiming the land for the King of France. Célèron encountered many British traders posted in Native American villages, but his presence failed to deter these British traders or to intimidate the Native Americans residing in the territory. As France and Great Britain did not reach an agreement, the land controversy erupted into the French and Indian War in 1754. The war ended in 1763 with a British victory that succeeded in expelling the French and establishing British dominance in the Ohio Valley. British colonists did not immediately settle west of the Allegheny Mountains, though, for British King George III issued a proclamation reserving the land for the Native Americans and forbidding settlement. [19]

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix, in 1768, rescinded the proclamation and opened the Kentucky territory for British settlement. Residents of western Virginia and Pennsylvania moved further west and settled in the Kentucky territory. The British government still prohibited settlement in the territory north of Kentucky and considered this region unsafe due to numerous Shawnee raids and assaults. But skirmishes also occurred between the Kentuckians and Shawnee. Kentuckians were intent on retaining possession of the land and the Shawnee, who had been forcibly removed from Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas, were determined not to move again. [20]

The American Revolutionary War delayed any answers to the disputes over land possession between British colonists and Native Americans. During the war, both sides tried to win the alliance of Native American tribes; eventually, the Ohio tribes aligned with the British. While no official battles were fought in the Ohio territory, many unofficial raids on settlements and villages occurred between the Native Americans and the European Americans. In May 1779, the Shawnee experienced the first of what became annual attacks by the Kentuckians on Shawnee villages. Colonel John Bowman led nearly 300 Kentuckians against the Shawnee at Old Chillicothe, also known as Old Town, near the present site of Xenia. Arriving at the site at night, Bowman and his troops decided to wait until the next morning to attack. During the night the Shawnee discovered the troops and fighting commenced. With the Shawnee protected in their village structures, and his troops armed only with rifles, Bowman retreated after having removed as many valuables from the village as possible. The Shawnee pursued the retreating Kentuckians, but they were only able to fire from afar. [21]

In 1780, George Rogers Clark led another military expedition from Kentucky into Ohio. On August 6, they arrived at Old Chillicothe and found that the Shawnee had abandoned and burned the town. The troops camped at the site for the night and destroyed several acres of corn and anything else left unharmed by the retreating Shawnee. Clark's troops also destroyed a Shawnee village near Piqua. Clark led another expedition in 1782 when Shawnee raids into Kentucky resumed. In the second raid, Clark led at least 1,000 men into Ohio, where at the mouth of the Mad River, they defeated a contingent of Shawnee sent to halt the troops' passage. This was the only battle that occurred on land that became the city of Dayton. Following the skirmish, Clark proceeded to the site of the present town of Piqua and burned several Shawnee villages and destroyed a British trading post. When the Revolutionary War ended in 1783, the United States became the official claimants of the territory. [22]

The United States Congress created the Northwest Territory, sometimes referred to as the Old Northwest, out of the area bounded on the east by Pennsylvania, the south by the Ohio River, the west by the Mississippi River, and the north by Canada. In order to create the territory, Congress needed to acquire the lands claimed in the colonial charters of the seaboard states and remove Native American claims to various territories. Four states claimed land in the northwest: New York, Virginia, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, but all surrendered their claims by 1786. Acquiring the Native American land claims proved more difficult. Between 1784 and 1789, the American policy focused on military conquest. In addition, Congress recognized that the Native Americans held title to the land through possession and attempted to gain control of the property through negotiations. Meanwhile, skirmishes continued between Euro-Americans and Native Americans over use of the lands. [23]

The Northwest Ordinance, passed in July 1787, established a governing system for the territory and a statehood mechanism to allow the nation to grow. Congress appointed a governor, secretary, and three judges for the territory, and when the population reached 5,000 free adult males, those eligible to vote elected a legislature. In addition, the legislation provided that once 60,000 people inhabited a section of the Northwest Territory, it could petition Congress to be admitted into the Union as a state. This was the first action by the United States to create a method by which other states could be admitted into the Union on an equal standing as the original thirteen states. [24]

John Cleve Symmes of New Jersey petitioned Congress in August 1787 for the tract of land in the Northwest Territory between the Miami Rivers from the Ohio River north to the mouth of Mad River. Born in 1742, Symmes migrated to New Jersey in 1763 and served in the American Revolutionary War. He was a member of the Continental Congress and appointed to the New Jersey Supreme Court. Following a trip west, Symmes became interested in the Miami Valley property through Benjamin Stites. Stites participated in some of the Kentucky raids into Ohio and, noting the beauty of the area, approached Symmes regarding its development potential. Congress approved Symmes's petition for the property, called the Miami Purchase, and granted him a contract in 1788 which called for Symmes to pay 66.6¢ per acre for the land. At this time, Stites and two partners planned to purchase the land at the mouth of the Tiber River, their name for the Mad River, from Symmes for 83¢ per acre. They proposed to name the town Venice. These plans never came to fruition. [25]

Raids continued between the Kentuckians and the Native Americans until General "Mad" Anthony Wayne led the U.S. Army and part of the Kentucky militia against Native Americans in 1794 in response to General Arthur St. Clair's defeat by Native Americans on the Wabash River in 1791. Wayne and the troops under his command defeated the Native Americans at Fallen Timbers near Toledo and secured the U.S. position in the territory. As a result of the victory, Native Americans ceded most of Ohio to the United States as part of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. The Treaty of Greenville established a boundary line separating Native American land and area now open to European-American settlers. This officially opened southeastern Ohio for that settlement, and many European-Americans, feeling an increased sense of safety due to the establishment of the treaty line, moved into the new territory. [26]

Not all Native Americans agreed with the Treaty of Greenville. Tecumseh, a Shawnee war chief, led the resistance against European-American settlement. Tecumseh's people originally resided along Deer Creek, a tributary of the Mad River, but he later moved to the headwaters of the White River in Indiana. Shawnee and other Native Americans throughout the region knew of Tecumseh and his fight for the property and supported him in his campaign to preserve the lands for Native Americans. [27]

Seventeen days after the ratification of the Treaty of Greenville, Symmes sold the property that is now Dayton to General Arthur St. Clair, Governor of the Northwest Territory; Colonel Israel Ludlow; General James Wilkinson; and Jonathan Dayton. The purchase, known as the Dayton Purchase, included the entire seventh and eighth ranges between the two Miami Rivers. The four purchasers of the property between the Little Miami and Great Miami Rivers near the mouth of the Mad River chose to name the new town Dayton, the most pleasing surname they felt of the four purchasers. On September 21, 1795, two survey parties left Cincinnati for Dayton. Daniel C. Cooper led a team which surveyed and marked a road between the two towns and Captain John Dunlap's team ran the boundaries of the purchase. Following the initial surveys, General Israel Ludlow platted the town. In commemoration of the founders, St. Clair, Ludlow, and Wilkinson, the city's major streets still bear their names. [28]

The first Dayton settlers traveled from Cincinnati. During the winter of 1795, forty-six people made arrangements to move to Dayton and drew lots for the newly platted town. Though only nineteen of the original forty-six moved, three separate parties left Cincinnati for Dayton in March 1796. One group, led by Samuel Thompson, left Cincinnati by pirogue and traveled up the Great Miami River. The party included Samuel Thompson's wife, Catherine Van Cleve, and her young children from a previous marriage, Mary and Benjamin Van Cleve. The other two parties, led by George Newcom and William Hamer, traveled overland on the road cut by Daniel Cooper. The number of pioneers totaled nearly sixty men, women, and children. Thompson's party, which traveled via the river, reached Dayton first on April 1, 1796. The other two parties arrived four days later. Cooper and his family and two other families joined the first settlers during the summer. [29]

During the winter of 1796, several additional families settled in the Dayton region. Families settled adjacent to Hole's Creek near the present site of Miamisburg, near Clear Creek, and the lower parts of what is now Montgomery County. Another settlement area included Mercer's Station near the present site of Fairborn on the Mad River. One of the first settlers outside the Dayton area was William Hamer, who led individuals up the Mad River upstream from Dayton to what is now Van Buren Township. Pioneers also arrived in the Washington Township area in 1797, near Hole's Creek. Shortly thereafter, a blockhouse and stockade were built there by Dr. John Hole, the first physician in the county and for whom the creek was named. [30]

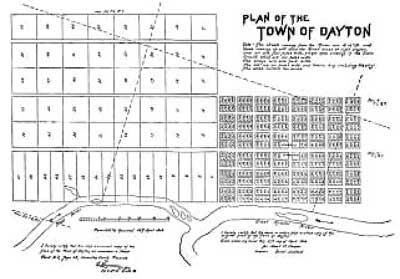

The offer of free land motivated many of the first Dayton settlers. Each individual received an "inlot" for a house and a ten-acre "outlot" away from the center of town for farming. Each settler was also entitled to purchase up to 160 additional acres at about $1.13 per acre. In the first summer the families erected homes, cleared farmland, planted crops, and prepared for the winter. In 1796, Dayton Township, a large area containing parts of current Montgomery, Greene, Miami, Clark, Champaign, Logan, and Shelby Counties, was formed. Daniel Cooper was appointed tax assessor and George Newcom the tax collector. In 1798, the first Dayton township tax assessed 138 taxpayers for a total of $186.662 in revenue; the average tax for property was $1.30. The highest tax assessed was Daniel Cooper's $6.25, which included the grist mill he operated.

PLAN OF DAYTON SHOWING THE INLOTS AND OUTLOTS. (Courtesy Montgomery County Historical Society) |

The lowest tax paid was $.372 each by eight individuals. This early tax assessment also recorded one of the first African Americans in the area. The tax rolls listed "William Maxwell (including his negro)." [31]

These early tax records also revealed the construction in 1796 of one of the most famous early buildings in Dayton, George Newcom's Tavern, which was located at the southwest corner of Main and Water (now Monument Avenue) Streets. [32] The original section of the tavern consisted of two stories with one room on each floor. A ladder provided access from the first floor to the second. The outer walls of the structure were oak logs chinked with lime mortar. In 1798, Newcom enlarged the tavern to include another room on each story and a stairway. Newcom's Tavern was the center of early town life. Besides providing lodging for all travelers, the tavern served as the community's meeting place. Individuals gathered in the main room to discuss the new town as well as other news. In the absence of many buildings, Newcom's Tavern also served as the early courthouse, church, and school. [33]

While the threat of Native American attacks decreased as a result of the Treaty of Greenville, settlers still perceived the possibility of violence. As a result, Daytonians constructed a blockhouse at Main and Water Streets in 1799. The blockhouse never served its original purpose, instead becoming the first school. Benjamin Van Cleve, one of the first European-American settlers, taught school beginning September 1. School closed the first of October so Van Cleve could harvest his corn. [34]

The pioneers continued to shape and form the new town of Dayton until near disaster struck in 1798 when the land titles held by the inhabitants were declared invalid. Symmes, who sold the property to the original four proprietors, never had legal right to the property, for he had not fulfilled the purchase obligations with the federal government. In addition, Ludlow, St. Clair, Wilkinson, and Dayton waived their right to purchase the property from the government. In 1800, the U.S. Government offered to sell the property to the residents at the rate of $2.00 an acre, but this was far beyond the means of the inhabitants. Some families left instead of paying the fee, and many potential settlers migrated to other locations. By the time the matter was settled in 1802 only five families resided in Dayton; those headed by George Newcom, Samuel Thompson, John Welsh, Paul D. Butler, and George Westfall. [35]

Daniel Cooper saved the town of Dayton by purchasing the townsite and replatting the town using the original survey with minimal alterations. The original settlers were once again given an "inlot" within the city and an "outlot." When original owners left the property, new settlers were required to pay $2.00 an acre and $1.00 for the city lot. In addition, Cooper donated property for a church to be built at Third and Main Streets, a cemetery on the block along Fifth Street between Ludlow and Wilkinson Streets, and the block known as Cooper Park bounded by Third, St. Clair, and Second Streets. Once land ownership was determined, settlers began arriving in Dayton, and the town grew steadily. In 1803, Ohio was admitted to the Union, and in 1805, Dayton was named the county seat of newly formed Montgomery County. Newcom's Tavern was appointed as the temporary seat of justice. Newly constructed buildings included a county jail on West Third Street, a post office, and the first commercial building, a store built by Henry Brown on Main Street. In 1805, the town of Dayton was incorporated, and for the next few years the city's growth and recurrent floods symbolized Dayton's history. [36]

Dayton's first recorded flood occurred in 1805. Reportedly water levels at Third and Main Streets reached eight feet, and city fathers discussed moving the city eastward to higher ground. By this time, the first library, a graveyard, and the first two brick structures, a tavern and house, also stood in Dayton, so they elected to construct a levee. As the town grew, the center shifted from along Water Street on the Great Miami River southward along Main Street. In 1806, Montgomery County let a contract to construct a brick courthouse that was forty-two by thirty-eight feet and two stories tall. The courthouse opened in the winter of 1807. In 1808, a two-story brick school, Dayton Academy, opened at the northwest corner of Third and St. Clair streets. The town benefactor, Daniel Cooper, donated the site, as well as two additional lots at Third and Main Streets that were sold to fund the construction. [37]

At this same time many immigrants arrived from the eastern United States to live on farmland surrounding Dayton. These additional settlers led to a rapid increase in Montgomery County's population. In the 1808 election, 564 votes were tabulated within the county. The voting by township within the county was Dayton Township, 196; Washington Township, 112; German Township, 125; Randolph Township, 47; and Jefferson Township, 84. [38]

Daniel Cooper brought an African American female servant to his farm in 1802; the first African American woman of record in the area. In the Population of Record, the woman was recorded as "Black Girl." While her name is not known, her children, Harry Cooper, born in 1803, and Polly Cooper, born in 1805, were documented. The children became indentured servants to Cooper until they were twenty-one and eighteen, respectively. Harry learned farming and milling while Polly trained in housekeeping. [39]

As free African Americans began to move to Ohio, the laws restricted the settlement of African Americans in the state. The Northwest Ordinance had provided that the territory would be free, but any escaped slaves in the territory could be lawfully reclaimed by their master. When Ohio became a state in 1803, the provisions on slavery within the Northwest Ordinance were adopted. This stance was strengthened in 1804, when the Ohio legislature passed a law stating that a person with African blood could not settle in the state without proof of freedom. Any African Americans already residing in the state also needed to furnish the proof, and no African Americans could be employed without it. [40]

By 1810, Dayton's population numbered 383, of which 131 were men aged sixteen or older, and 7,722 people resided in Montgomery County. The 1810 tax assessment raised $865.782 in tax revenue reflecting the many new structures in the city. The number of homes in the town grew to five brick houses, twenty-six frame houses, nineteen log houses, and seventeen cabins. Local businesses included a printing office, six taverns, five stores, two nail factories, a tannery, a brewery, three saddler shops, three hatters, three cabinetmakers, a gunsmith, a jeweler, a watchmaker, a sickle maker, and a wagon maker. Other professions included smiths, carpenters, masons, weavers, and dyers. Merchandise was moved in and out of the city on keelboats and flatboats along the Great Miami River. In addition, suburbs developed south of Third Street called Cabintown; at Wilkinson and Water Streets called Rattlesnake, or Specksburg; and east of St. Clair and north of Third Street called Commons, which existed until 1820. [41]

In 1811, warlike relations between Americans and Native Americans resumed. Tecumseh, in a continuation of his efforts begun after the ratification of the Treaty of Greenville, rallied the Shawnee in a plan to expel the Americans once and for all from the western lands. In November, as Tecumseh recruited followers, his brother Tenskwatawa, or Prophet, led troops against William Henry Harrison at Tippecanoe. Harrison, Governor of the Indiana Territory, and his troops defeated the Shawnee. As a result, Tecumseh aligned with England in the War of 1812 with the agreement that, following the war, Native Americans would regain possession of southern Ohio. In April, President James Madison called on Ohio to supply 1,200 militia for one year of service to be commanded by General William Hull, Governor of the Michigan Territory. The troops assembled in Dayton on April 29, causing the population to grow to almost three times its original size with the addition of the soldiers. While in Dayton, the soldiers camped to the east and south of town. On June 1, 1812, the militia left for Detroit and on June 16, the United States declared war on England. [42]

On August 16, General Hull surrendered to General Brock of the English military in Detroit. The news brought fear to southern Ohio of possible invasion from the north by British troops and Native Americans. Preparations were undertaken to fortify and protect Dayton and the surrounding area. Within several days of Hull's defeat, Montgomery County organized six militia companies and collected supplies of food and ammunition. In upper Montgomery and Preble Counties, residents constructed blockhouses. In addition, Dayton once again served as a gathering point for the troops heading northward. To protect Dayton, Colonel Robert Patterson continued to collect local military stores. Citizens assisted him in collecting grain, horses, and cattle from the surrounding area, and women assisted by making and assembling clothing and blankets for the soldiers. [43]

The main role of the city was providing support to the war effort, for it was never attacked. Many of the troops heading northward passed through the region, and those Daytonians not involved in the fighting only saw the preparations and aftermath of the battles. Many soldiers, sick and wounded from the fighting in the north, were cared for in Dayton. Also, government agents purchased all available crops and supplies from area farmers and merchants. The normally quiet city was bustling with activity during the war. Once the war was over and the United States had reclaimed the territory lost in Hull's surrender, soldiers began returning home. Many of the troops marched through Dayton, and many relatives of the soldiers flocked to Dayton in hopes of being reunited with their family members. [44]

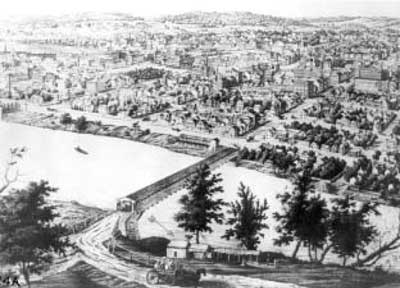

BIRDSEYE VIEW OF DAYTON LOOKING EAST ACROSS THE MIAMI RIVER, C. 1822. (Courtesy of Dayton and Montgomery County Public Library) |

Following the War of 1812, despite the growth to support the war efforts, Dayton was still quite small and centered on the banks of the Great Miami River along Water Street between Ludlow and Mill Streets. The first market opened on the Fourth of July in 1815. Located in a long wooden building on Second Street between Main and Jefferson Streets, the market was the first central location in Dayton where supplies could be purchased. The market operated two days a week, Wednesday and Saturday, in the early morning. In the interior of the market, butchers' stalls lined either side of the large room. Farmers sold produce outside under the building's eaves. [45]

In 1814, another flood struck the city. Instead of creating concern, it had the positive effect of initiating discussions in regards to constructing a canal stretching between the Ohio River and the Mad River. Prior to the 1814 flooding, Dayton experienced a drought and was unable to transport goods on the river. Then, when the rain increased the depth of the river, and shipping resumed, boats foundered on sand bars and lost all or portions of their cargo. The experiences with drought and flooding magnified the undependable nature of shipping goods via the Great Miami River, and a canal, it was felt, would provide a dependable method of conveying goods into and out of Dayton and improve the local economy. [46]

While discussion of transporting goods continued, Dayton grew as a city and expanded beyond the natural boundaries of the Great Miami and Mad Rivers. Simultaneous with, and contributing to, this growth and expansion were the improved transportation modes. Montgomery County contracted for the first bridge to cross the Mad River in 1817. Prior to the bridge's construction at Taylor Street, the only way to cross the river was via a ferry or ford. In June 1818, Daniel Cooper and John Piatt, of Cincinnati, developed a freight line running between Cincinnati and Dayton with various stops. Also, in May 1818, a Mr. Lyon operated a passenger coach between Dayton and Cincinnati. A second coach began operating in 1820 under the ownership of John Crowder and Jacob Musgrave. Crowder and Musgrave's coach was the first African American-owned business in Dayton. Despite these improvements, shipments of locally produced commodities continued along the Great Miami River; but the river remained an unreliable means to transport goods to market. Prior to the development of these services, the only form of travel between Dayton and Cincinnati was by private means. [47]

The idea of a canal connecting the Ohio and Mad Rivers gained further support when work started on the Erie Canal between Albany and Buffalo, New York, in July 1817. Ethan Allen Brown of Cincinnati, who became Governor of Ohio in 1818, began campaigning for an Ohio canal in 1816. Daytonians joined the crusade in 1821 when they appointed a committee to consider the canal issue and raise funds to pay for a survey for a canal route. Discussions of a canal occurred frequently throughout Dayton. Stephen Fales spoke at a Fourth of July dinner in 1825 about a canal connecting the Mad and Ohio Rivers. The Governor of New York, De Witt Clinton, came to Dayton after dedicating a canal in Newark, Ohio, to discuss the potential of a canal in Dayton. Governor Clinton's speech, according to Dayton history books, did more than any other event to foster support for a canal. [48]

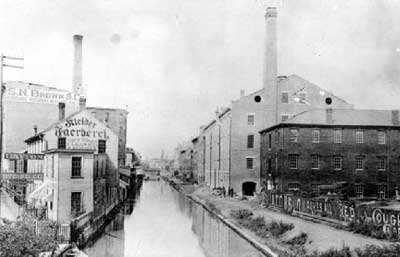

Once a canal was determined feasible, the questions of funding and routing arose. In January 1822, the Ohio Legislature passed a bill authorizing the governor to employ an engineer and appoint commissioners to conduct canal surveys and prepare cost estimates. James Geddes, an engineer who worked on the Erie Canal, surveyed possible routes and suggested five, one of which was the Great Miami River route. In 1825, the Canal Commission recommended construction of part of the canal system. The Ohio Legislature then passed an act authorizing the construction of two canals, including the Miami Canal along the Great Miami River valley between Dayton and Cincinnati. Ground was broken for the Miami Canal in Middletown on July 21, 1825. Locally, the canal traveled along what is now Patterson Boulevard, terminating into a large basin east of Cooper Park. On January 25, 1829, almost seven years later, the first canal boats from Cincinnati arrived in Dayton. The canal established Dayton as the head of navigation for areas north, for it was the closest dependable water connection to the Ohio River for northern farmers. [49]

MIAMI CANAL IN DOWNTOWN DAYTON. (Courtesy of Dayton and Montgomery County Public Library) |

In addition to increased transportation via the canal, turnpikes developed along the country roads throughout the region and greatly increased individual travel. After the National Road circumvented Dayton, the town council directed the mayor to forward information to Congress for a route passing through Dayton to be reconsidered. When this failed, attention turned towards improving the existing country roads. In February 1833, three turnpike companies were chartered: the Dayton & Covington; Dayton, Centerville & Lebanon; and Dayton & Springfield. The first construction began in Centerville by the Dayton, Centerville & Lebanon Company in April 1838. More turnpikes developed throughout the 1840s, connecting most of the towns and cities within the region. [50]

Discussions of railroads began in Dayton in the early 1830s, but no service was developed until 1849. In July 1831, Dayton citizens were invited to experience a railroad that was built inside a large building on East Third Street. The railroad consisted of a circular track of wooden rails and a small car and locomotive that carried two people at a time. A ride cost twenty-five cents. Despite this initial interest, Dayton did not develop a railroad system until much later than surrounding towns. Xenia and Springfield first connected to southern and northern railroads and soon became the central connections. For many years, Daytonians had to travel to either of those cities to catch a train. It was not until 1851 that Dayton completed a railroad connection with Springfield and soon at least four railroads serviced Dayton: the Dayton and Western; the Cincinnati, Hamilton and Dayton; the Greenville and Miami; and the Dayton and Union. The first passenger station was constructed on Sixth Street west of Ludlow Street in 1856. [51]

Along with transportation, Dayton grew demographically and economically. By 1840, Dayton's population numbered 6,067 and reached 20,081 by 1860. In 1845 there were 880 brick buildings, 1,086 frame buildings, and six stone houses within the city. Improvements continued, and in 1847 the city began work to replace the courthouse with a new building at the same location, the northwest corner of Third and Main Streets. The new courthouse was constructed of Dayton limestone and completed in the spring of 1850. About the same time, J.D. Phillips constructed the Phillips House on Third Street near the courthouse. This hotel was a prominent fixture in Dayton until its demolition in 1926. [52]

ENTRANCE GATE TO WOODLAND CEMETERY. (Courtesy of Dayton and Montgomery County Public Library) |

In 1841 among the businesses located in Dayton and the surrounding area were five cotton factories, two carpet factories, one hat factory, five flour mills, five sawmills, one gun barrel factory, two paper mills, two turning lathes, four foundries, four soap and candle factories, one clock factory, four distilleries, two breweries, and two rope walks. The total number of manufactories was 144. In 1849, E.E. Barney and E. Thresher established E. Thresher & Company, which became the Barney & Smith Manufacturing Company in 1867. The firm manufactured railroad cars and grew so rapidly that by the 1880s the factory covered over four acres. Other prominent businesses that developed in the 1840s and 1850s included Dayton Wheels Works, Baird and Brothers Planing Mill, Pritz & Kuhnst, Commercial Mills, Mead Paper Company, and G. Stomps &Co. Chair Factory. [53]

In 1840 discussions began regarding a new cemetery for the city. The desired location was somewhere on the outskirts of the city as those located within the center of town were being threatened by urban growth. Daniel Cooper donated land for the first cemetery following his purchase of the city property in 1802. It sat adjacent to the Presbyterian Church on the northeast corner of Third and Main Streets. By 1805 the cemetery property was in demand for development, and Cooper donated a new cemetery site on the south side of Fifth Street between Ludlow and Wilkinson Streets to replace the original. As the city grew, this second cemetery filled and once again the property was desired for development. John Van Cleve established a new cemetery and located a potential site one mile south of Dayton. The new cemetery site of forty acres was purchased in 1841, and Van Cleve led the organization effort by the Woodland Cemetery Association. The Ohio General Assembly passed the cemetery's charter on February 28, 1842 and the Woodland Cemetery Association subsequently adopted it on April 10, 1842. Woodland Cemetery was officially dedicated on June 21, 1843. [54]

Dayton experienced further change when another flood occurred on January 2, 1847. In response to the rising river level, many merchants along the Canal Basin moved their goods to the second stories of their buildings. The two levees protecting the city failed during the night and escaping water flooded a portion of the city. Many people predicted a possible flood and evacuated the lower story of buildings, greatly decreasing the damages. Following the flood, another levee was constructed to protect Dayton. [55]

As the town grew, additional land was platted and developed. The area west of Dayton across the Great Miami River began to develop in the 1840s. In 1845, Herbert S. Williams platted the town of Mexico, which consisted of thirty-nine lots along Third Street west of Williams Street. New Mexico, located near the same area, was platted shortly thereafter. In 1854, George Moon and Joseph Barnett platted the town of Miami City, located south of Wolf Creek running south to the railroad. In addition to these towns, other areas were platted between the 1840s and 1850s leading to the growth of a suburban area west of Dayton. In 1943 Charles F. Sullivan, a long time resident of Dayton, remembered Miami City as, "...the name of the town from Olive to Summit streets and they had their own post office, railroad station and city officers...." The development of trolley lines, such as the Dayton Street Railroad chartered in 1869, fostered this suburban growth, by providing an easy transportation to and from the city's center. [56]

The Civil War began with the battle at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, in April 1861. President Lincoln's call on April 15 for 75,000 soldier volunteers affected Daytonians. The Lafayette Guards, Dayton Light Guards, and Montgomery Guards volunteered for three months of service and left Dayton, marching through cheering crowds. Later, when a three-year enlistment was instituted, Camp Corwin developed two and a half miles east of Dayton. In August, the first of three companies of the First Regiment of Ohio Volunteer Infantry were ordered to Corwin and the Dayton Cavalry soon followed.

BIRDSEYE VIEW OF DAYTON LOOKING EAST ACROSS THE MIAMI RIVER, C. 1853. (Courtesy of Dayton and Montgomery County Public Library) |

When all of the troops left to join General McCook's brigade in October, the camp was abandoned. Among the effects of the Civil War on Dayton was the absence of young, able-bodied men. The threat of Confederate invasion concerned citizens, but troops never got nearer to Dayton than Oxford, Ohio, and areas in Kentucky. [57]

When the Milton Wright family moved to Dayton in 1869, the city was growing rapidly. It reached a population of 30,473 by 1870, and manufactories and businesses continued to establish in Dayton. The business section of Dayton centered between Second and Fourth Streets on Main. The city's upper class located in the area west of Wilkinson. The Wrights lived in a suburban section of West Dayton that developed during the mid-nineteenth century. [58]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

daav/honious/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 18-Feb-2004