|

Dayton Aviation

What Dreams We Have The Wright Brothers and Their Hometown of Dayton, Ohio |

|

Chapter 2

The Wright Family

When the Wright family moved to Dayton in 1869, it was on the cusp of becoming a full-fledged city, and it was in this climate that Susan and Milton Wright raised their five children. The importance of their Christian beliefs was evident in the Wrights' philosophy for raising their children. Most critical to Susan and Milton was a Christian upbringing that stressed strong beliefs and the importance of one's family, both nuclear and extended. As future events illustrated, the Wrights felt that with the support of the family, anything could be overcome. Reflective of this belief, Milton, throughout his life, remained in contact with his relatives and documented the Wright family genealogy. As a result of these efforts, the Wright family ancestry was well researched and preserved.

The first Wright ancestor to immigrate to the United States was Samuel Wright who left his home in England and settled in Springfield Township, Massachusetts around 1638. By 1647 Samuel owned over forty-one acres of land, and in 1648 he became the owner of a toll bridge. Samuel, a Puritan, served as deacon of the church, and later the church appointed him to act in the place of an absent pastor. In later years, Samuel moved to Northampton, Massachusetts, where he died in 1665. [1]

Dan Wright, born in Thetford Township, Orange County, Vermont, on September 3, 1790, was Samuel's great-great-great grandson and Milton Wright's father. Born to Dan and Sarah Freeman Wright, Dan was the couple's third son. As described by Milton,

He was of excellent health and strength. He was five feet, nine inches, in height, and straight as an arrow, and weighed about one hundred and fifty pounds... He was grave in his countenance, collected in his manners, hesitating in his speech, but very accurate. Unless much excited there was little change in his countenance and manners. [2]

Educated in the local schools of Vermont, Dan taught one year of school and then moved to Genesee Valley, New York, in 1813, to join his brother Porter and his wife. The following year, the entire family-Dan, his parents, and his three siblings-moved west. The family traveled via flatboat on the Allegheny River and then the Ohio River to Cincinnati, Ohio. Once arriving in Cincinnati, they went by wagon to Centerville. [3]

Founded in 1796, Centerville was located south of Dayton in Washington Township on the land between the Little and Great Miami Rivers. The first settlers, Aaron Nutt, Benjamin Robbins, and Benjamin Archer, surveyed the land in February 1796. The three men drew lots for their land, and within several years all three moved their families to the new town. Additional settlers soon moved to the area, and by 1798 the tax assessment identified fifteen households in the area. The town was platted in 1805-1806, and in 1817 the first plat records were filed. [4]

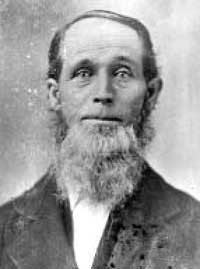

GEORGE REEDER (Courtesy of Library of Congress) |

Like his son Milton in later years, Dan remained in contact with his family. He regularly corresponded with his older brother Asahel who resided in Centerville until 1827 when he moved to a farm in West Charleston, Bethel Township, Miami County, Ohio. Asahel's house in Centerville, was located near the northeast corner of the intersection of Main and Franklin Streets. Asahel purchased the property from E. Williams on August 16, 1816 for $150 and sold it in 1826. Until 1817, Asahel operated a stillhouse located near the present site of the intersection of Alexandersville-Bellbrook Road and Dayton-Lebanon Pike. Asahel rented the property from Aaron Nutt, and he used it to manufacture liquor and peppermint oil. Common Pleas Court records also documented that Asahel operated a store at the intersection of Main and Franklin Streets from 1816 until 1824. [5]

Dan Wright also resided in the Centerville area and worked at a local distillery. His residence was further documented in his marriage on February 12, 1818, to a local Centerville girl named Catherine Reeder. Catherine's parents were George and Margaret Van Cleve Reeder. Margaret's mother was Catharine Van Cleve Thompson, reputed the first white woman to set foot in Dayton when the first settlers arrived in 1796. Born on March 17, 1800, Catherine lived in Duck Creek, east of Cincinnati, until 1811 when the family moved to a farm in Centerville. In later years, Milton Wright wrote of his mother Catherine: "From early childhood she was of delicate health, but all her life full of energy and activity. Industry, affection, and conscientiousness were three of her chief characteristics. Home was her sphere, and her children her jewels." In February 1821, Dan quit working at the distillery and focused on farming. Subsequently, Dan, Catherine, and their two young sons, Samuel and Harvey, moved west to an eighty-acre farm in what became Rush County, Indiana. [6]

Finding their promised cabin unfinished, the Wright family moved into half of the proprietor's cabin, and the following spring Dan constructed a cabin for his family. In the first year, Dan cleared five acres on which he grew corn. While on this farm, Catherine gave birth to another son, George, who died in infancy. [7]

In 1823, Dan sold the farm and the family moved to a new tract of one hundred twenty acres about a mile and a half to the southeast of the previous farm. Four new members of the family were born on this farm: Sarah on November 21, 1824; Milton on November 17, 1828; William on February 29, 1832; and Kate, who died at birth probably sometime in 1834. [8]

Many of the ideals that Milton passed on to his children he obtained from his father. High morals and defined beliefs were dominant features of Dan's personality. A confirmed Christian who converted in 1830, Dan, an abolitionist, did not join a specific church, for he could not find a denomination that adequately opposed slavery. Following his religious conversion later in life, Dan believed in temperance and refused to sell any of his corn crop to distilleries for production although this often meant accepting a lower price for his crop. Dan also opposed secret or fraternal societies. Milton followed his father's lead and supported these main ideals, and passed them on to his children. [9]

When Milton was twelve, the family moved to a new farm in Orange Township, Fayette County, Indiana. A child who pursued self improvement, Milton often practiced public speaking while he worked in the farm fields. In later years, Milton remembered he filled "the fields with speeches, which often attracted the ears of the family and sometimes the neighbors." While laboring in the fields, Milton also worked on improving his mind. As a result of his efforts, Milton found "hard thinking was so much of a habit, that I had to regulate this tendency." [10]

Following a conversation about Christianity with his mother when he was eight, Milton constantly pursued and questioned religion. In June 1843, when he was fifteen, Milton's quest ended when he experienced a conversion while working alone in his father's corn field. Unlike the typical conversions where an individual experienced the presence of God with a jolt, Milton felt an "impression that spoke to the soul powerfully and abidingly." Like his father, Milton did not immediately join a church, for he did not wholly agree with any church's religious philosophy and teachings. Four years later, though, Milton and his brother William were baptized by the Reverend Joseph Ball of the White River Conference of the Church of the United Brethren in Christ. [11]

SUSAN KOERNER WRIGHT (Courtesy of Wright State University, Special Collections and Archives) |

Two years after his baptism, on April 27, 1850, the White River Conference licensed Milton to preach and exhort, and he gave his first sermon on November 17, 1850. At this time, it was common for men to begin their ministry soon after they expressed their belief that God had called them to be a preacher. Local congregations recommended candidates for licensing to the quarterly conference. A year later, the quarterly conference could then recommend the candidate for approval at the annual conference. On August 26, 1853, Milton was approved as a preacher and became a member of the White River Conference. He was ordained by the Bishop and Elders of the White River Conference as a United Brethren minister on August 9, 1856. Milton's brothers who survived into adulthood also became ministers. Harvey became a Baptist preacher, and William became a United Brethren minister. [12]

Although he was preaching, Milton did not earn enough money to support himself, and he supplemented his income by working on his father's farm and teaching school. This circumstance was common with the ministers of the time. Many of them made their living as farmers or in another occupation and preached in their spare time. In the 1850s the General Conference of the church set the annual salaries at $150 for unmarried preachers and $300 for married ones. [13]

In April 1852, the school examiners of Rush County, Indiana, certified Milton to teach orthography, English grammar, reading, writing, arithmetic, and geography in "common schools" for one year. After a "preaching tour" in the winter of 1853, Milton received a call to serve as a teacher in the preparatory department of Hartsville College, a United Brethren institution, located in Hartsville, Indiana. While at the college, Milton took courses in addition to instructing. He did not obtain a college degree, for he left the school the following year when he became very ill with "remitting fever." [14]

While at Hartsville College, Milton met Susan Catherine Koerner. Milton had been searching for a wife who would assist in fulfilling his strong notion of family. J.E. Hott, a fellow minister, described in later years what he viewed as an ideal minister's wife, a definition that most likely characterized what Milton saw in Susan:

A minister... knows only too well how much depends on the minister having a good wife. If she is a fashion plate she spoils all the girls; if she is extravagant in habits of living, a poor charge will not support her; if she is an untidy housekeeper, she cannot be sent to refined and cultured people; if she is a gossip from house to house, she will keep the charge in an uproar of turmoil and confusion and so on indefinitely. On the other hand if she is a quiet, devout, sympathetic Christian, and well-skilled in household and domestic affairs, her husband can leave her for a few days in a home of an outsider while he goes to a remote appointment and on returning will find that, that family is forever bound to the cause of Christ and the church with hooks of steel. May God bless our preachers' wives with this spirit and influence. [15]

Milton believed Susan possessed many of these characteristics and that she was a probable candidate for his wife. Born near Hillsboro, in Loudoun County, Virginia, on April 30, 1831, Susan possessed a strong commitment to Christianity and was extremely shy. [16]

Susan's parents, John Gottlieb and Catharine Fry Koerner, first lived with Catharine's parents on a farm three miles southeast of Hillsboro. John, a carriage maker by trade, operated a small shop on the farm and a forge in the town. The family sold the farm in 1832 and moved to a 170-acre farm in Union County, Indiana. When their grandson Orville visited the Koerner farm almost fifty years later, the property was developed with twelve to fifteen buildings, including a carriage shop. Shortly after moving, the Koerner family converted from Presbyterianism to the United Brethren Church. Susan joined the church in 1845 after experiencing a conversion. [17]

As a child, Susan spent many hours with her father in the carriage shop and developed an understanding of mechanical devices. She, instead of Milton, who was more of a scholar, repaired items and often invented items for use in the home. Through Susan, her children Wilbur and Orville developed a desire to tinker with mechanical objects until they understood how they functioned. As described in an article on the Wright brothers, Susan "was one of those rare women who can do things with her hands. She used to make bob-sleds and playthings for the boys, and of course, interested them in what they were trying to make." [18]

Milton and Susan proceeded cautiously with their relationship. They did not marry until November 24, 1859, six years after they met. Susan remained a student at Hartsville College after Milton returned to his father's farm and taught school. In August 1856, he was posted to the Andersonville Circuit of the United Brethren ministry, which was comprised of churches in Indiana. In 1857, Milton joined the church mission headed to Oregon. Prior to his departure, Milton met with Susan. In his diary, he recorded, "I supped at David's, went to Daniel's and had my first private talk with Susan Koerner. I asked her to go to Oregon with me." [19]

Susan declined and the two parted. While in New York, Milton sent Susan a letter and enclosed his photograph. According to Milton's memories, the letter "captured" Susan, and she wrote to him "determined to have me." When Milton returned to Indiana in 1859, he and Susan were married. The separation of two years was the beginning of a circumstance that lasted throughout their marriage. Milton, dedicated to the ministry, constantly traveled the circuit and was frequently away from his family. When Milton traveled, Susan remained home to care for the family. During his absences, the Wright family kept in constant contact through letters. [20]

After their marriage, Milton and Susan settled near Rushville, Indiana. Without a church appointment, Milton taught at the New Salem subscription school. They moved again in April 1860, to Andersonville, Indiana, where Milton taught at Neff's Corner. In the fall of 1860, Milton received an appointment as a preacher on the Marion Circuit, and in August 1861, the White River Conference elected him presiding elder of that circuit. Milton and Susan moved to a farm Milton owned in Grant County, near Fairmount, and lived in a log cabin on the property. During the years they resided on the farm, Milton served in the Marion, Dublin, and Indianapolis Districts of the church. [21]

Milton and Susan's first child was born on the Grant County farm. Reuchlin (pronounced Rooshlin), born on March, 17, 1861, was named for Johannes Reuchlin, a German theologian. Milton, convinced that Wright was a common name, strived to give his children unique names. On November 18, 1862, their second child, Lorin, was born at Dan Wright's home. Once again searching for a distinctive name, Milton and Susan named their new son after a town on the map. [22]

The Wrights moved again in 1864 while Milton rotated between the circuits in the Marion, Dublin, and Williamsburg Districts. As Milton's duties changed, the family moved and lived in rented houses. In September 1864, Milton purchased a five-acre farm eight miles east of New Castle and two and a half miles northeast of Millville. Milton paid $550.00 in cash for the property and promised $200 without interest in two years. The family did not move into the three room house on the property until April 13, 1865. [23]

The couple's third son, Wilbur, named for Wilbur Fiske, a preacher that Milton respected, was born on the farm on April 16, 1867. In later years, Milton reflected that, "perhaps there is now nothing very remarkable in the size or shape of his head, but then it was so high that a hat becoming him was hard to find." Wilbur, or Willy as Milton called him, began walking when he was nine and a half months old. An active child, Milton remembered Wilbur as being able to locate the greatest possible mischief in a room. [24]

In 1868 the family moved once again. This time the destination was Hartsville where Milton served as the first professor of theology and developed the theological department at Hartsville College. In 1869 those at the General Conference elected Milton the editor of the Religious Telescope. [25] The newspaper was published weekly and carried official church news to members throughout the United States. Milton's appointment as editor of the newspaper meant that the Wright family moved once again, this time to Dayton, for the church housed the publishing operations in a building on the northeast corner of Fourth and Main Streets in the city. [26]

During the same meeting where Milton was elected editor, discord developed among the rulers of the church on the question of approval or disapproval of secret societies. The 1841 constitution of the Church of the United Brethren in Christ included an anti-Masonic statement. However, new ministers within the church felt that the statement should be removed. Following the Civil War, secret societies grew rapidly in popularity and were no longer seen as negative organizations. Those backing the secret societies were branded Liberals, while the conservatives, including Milton, that remained against the societies were called Radicals. Throughout the discussion, Milton firmly stood on the side against secret societies. The Radicals prevailed at the 1869 convention, and the church continued to condemn secret societies. Milton, in his new position as editor of the Religious Telescope, controlled the church's publication and allowed proportional coverage to both sides of the argument in relation to the number of people on each side of the issue. [27]

FITCH HOUSE (Courtesy of National Park Service) |

Arriving in Dayton in June 1869, the family chose to live in West Day ton, an area west of the Miami River that was newly annexed to the city. They first rented a house on West Third Street at the corner of Sprague Street. In November they moved into John Kemp's brick house on Second Street east of the railroad. In February 1870, while the family lived at the Second Street house, Susan gave birth to twins, Otis and Ida. Both died shortly after birth, and they were buried in Greencastle Cemetery located at the corner of Broadway Street and Miami Chapel Road in West Dayton. [28]

The area of Dayton that the Wright family chose for their new home, West Dayton, developed as a street car suburb of Dayton with an urban flavor. The main thoroughfare, which contained the majority of the businesses and some homes, was West Third Street. Residential areas stretched to both the north and south of the street. The lots were small in size and the houses were constructed close together. In most instances, only a foot or two separated neighboring homes.

One of the first homes in the area was built by Daniel G. Fitch. A native of New Jersey, Fitch moved to Dayton in 1848 and became the joint owner of the Western Empire, a weekly newspaper. He served as the newspaper's editor until 1855 when he was elected Montgomery County Recorder. Located on the southwest corner of Fourth and Williams Street, the home was constructed around 1856. [29]

The West Side began to rapidly develop after annexation to the city of Dayton in 1869. That same year W.P. Huffman and Herbert S. Williams established the "Dayton Street Railroad" that connected neighborhood areas to the city. Huffman owned property on the east side of town and Williams on the west side, or West Dayton. The two investors hoped that the rail transportation into the city would promote development and increase the value of their property. [30]

As property values rose, Williams sold various lots on the west side to builders. The builders then developed the lots and sold the homes to individual buyers. On December 21, 1870, Milton purchased a home for $1,800 in West Dayton from James Manning, a builder who had purchased some of the land platted by Williams. The house was still under construction when Milton bought it, and the family did not move into it until April of the next year. Located at 7 Hawthorne Street, [31] the house was a modest two story frame structure. The Wrights' new neighborhood included many working class residents, and most of the houses were newly constructed, like the Wrights' home, by either builders or the families themselves. [32]

DAYTON MALLEABLE IRON WORKS (Courtesy of NCR Archives at Montgomery County Historical Society) |

In addition to residential housing, manufacturing businesses began appearing on the West Side. One of the largest was Dayton Malleable Iron Works located on the north side of West Third Street between Summit Street and Dale Avenue. Established in 1866, the iron works produced carriage hardware and malleable iron castings. By 1882 the company conducted $150,000 in annual business. Other west side manufacturing companies included John Dodds, who manufactured grain and hay rakes, and A.L. Bauman's cracker factory on West Third Street. [33]

One of the characteristics of the developing West Side was the large concentration of Eastern Europeans. In 1898 the Dayton Malleable Iron Works placed an advertisement in a Toledo newspaper for a foreign labor contractor. At this time, the Dayton economy was booming and demands on the factories exceeded the available supply of labor. To find labor, Dayton Malleable Iron Works chose to recruit foreign workers. A Hungarian, Joseph D. Moskowitz, was hired as the foreign labor contractor, and for the next few years he recruited skilled mechanics and laborers from Hungary to move to Dayton to work at the Dayton Malleable Iron Works. [34]

Located north of West Third Street and west of Broadway Street, the Hungarian community consisted of homes for the workers, a clubhouse, meat shop, and general store. By 1904 the settlement included approximately 700 inhabitants, most employed by Dayton Malleable Iron Works. Moskowitz financed all of the construction, and he continued to own and operate the businesses until 1902. Called the West Side Colony, this area continued to attract Hungarian and Eastern European immigrants even after Moskowitz left in 1901. By 1910, about six thousand Eastern Europeans, including two to three thousand Hungarians, resided in the neighborhood. [35]

The West Side Colony, while near the Wright home, was a completely separate part of West Dayton. The Hungarians continued to speak their native language and follow Hungarian traditions. The Wrights' neighbors were middle and working class residents mostly from Ohio. By 1900 90 percent of the Wright family's immediate neighborhood was working class families and 10 percent were professionals. In addition, 5 percent of the neighborhood population were immigrants and 1 percent African American. A quarter of these residents owned their own homes. Despite these statistics, it was hard to develop a description of the typical family, for the residents varied greatly in the number of people per house, occupations, and heritage. [36]

ORVILLE WRIGHT (Courtesy of Wright State University, Special Collections and Archives) |

Orville Wright, Milton and Susan's sixth child, was born in this neighborhood in the family's new home at 7 Hawthorne Street on August 19, 1871. Milton named him after Orville Dewey, a Unitarian minister he admired. The couple's last child, and only surviving daughter, Katharine, [37] was born in the house three years to the day after Orville. [38]

The five surviving Wright children experienced a typical childhood in West Dayton. When the Wright family moved to the West Side, it was a small newly developed suburb of Dayton. The small size allowed for most of the residents to know and socialize with most of their neighbors. There was one school for the community, which was located on the west side of Perry Street between First and Second Streets. By the time that Orville entered the first grade, there was a school located on the west side of the river at the southwest corner of Fifth and Barnett Streets. [39]

The Wright children spent part of their days attending school and completing chores, but there still remained a significant amount of time for play. One of the common games on the west side was "fox," which was similar to "hide and seek." Several children, playing foxes, received a head start and then blew a horn. The remainder of the participants pursued them, and the "hunt" continued until all the foxes were captured. In many of the games, Reuchlin, Lorin, their friend Al Feight, and other older children played the foxes, while the younger children, like Wilbur and Orville, were the hunters. [40]

WILBUR WRIGHT (Courtesy of Dayton and Montgomery County Public Library) |

Wilbur and Orville also participated in games of marbles and top spinning. Throughout the neighborhood, Orville was known as the best marble player. He was often seen with his pockets bulging from his winnings at the game, and Wilbur often borrowed marbles from Orville. On the other hand, Wilbur was a proficient top spinner, who often destroyed his companions' tops. In later remembrances, the brothers' childhood playmates remembered them as honorable children, who never cheated or took advantage of anyone. [41]

The Wrights taught their children to earn whatever money they spent, and some of Orville's childhood activities focused on ways to earn money. One of his early ventures was collecting old bones in the neighborhood alleys and vacant lots. Orville and a friend then sold the bones to a fertilizer factory. In several instances, Orville borrowed money from Wilbur, who was more of a "saver" than Orville. The boys arranged that any money Orville borrowed would be repaid with the next money he earned. [42]

Their inquisitive minds led Wilbur and Orville to pursue various scientific experiments and inventions. Orville filled the kitchen with various devices, experimented with them, and then moved on to other projects. Susan would place Orville's inventions on a shelf for a time when they might interest him again. Both Milton and Susan encouraged their children's curiosity and felt that it was another form of education and learning. [43] In later years Katharine recalled the uniqueness of her parent's approach to parenthood:

I wish you could know what Father and Mother were like. They were so independent in the way they ran the family. I used to wish they would be more like other people! No family ever had a happier childhood home than ours had. I was always in a hurry to get home after I had been away for half a day. [44]

Shortly after his fifth birthday, Orville started kindergarten. The school was a short walking distance from the Wrights' Hawthorne Street home, and Orville would leave shortly after breakfast and promptly return home after class. After approximately a month, Susan met with Orville's teacher to make sure that Orville was behaving satisfactorily and doing well in school. The teacher was surprised to see Susan, for Orville had not attended class since the first few days. Upon returning home and questioning her son, Susan discovered that he spent each day with his friend Edwin Henry Sines, or Ed, at the Sines' house at 15 Hawthorne Street, which was two doors down the street from the Wrights' home. Orville was not severely punished when his parents discovered that the boys were focusing their attention on repairing an old sewing machine in the Sines household. [45]

In 1877 the General Conference of the United Brethren elected Milton a bishop, and he was assigned to the region between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. In his duties, Milton traveled quite extensively. For a while, the family stayed in Dayton while Milton visited the conferences throughout the region. In June 1878, when the extra mileage to return to Dayton became too much travel for Milton, the family moved to Cedar Rapids, Iowa. [46]

Returning from a trip in the autumn of 1878, Milton brought a rubber band powered toy helicopter home for Wilbur and Orville. Milton came into the house with the toy concealed in his hands, and then threw it into the air. Instead of falling to the ground as Wilbur and Orville expected, the helicopter "flew across the room till it struck the ceiling, where it fluttered awhile, and finally sank to the floor." The toy was designed by the French aeronautical experimenter Alphonse Pénaud. Consisting of a cork and bamboo frame that was covered with paper, the toy was propelled into the air with a rubber band. Wilbur and Orville, who called the toy a bat, played with the toy frequently ,but due to its fragile construction it soon broke. Despite the short life of the toy, it remained in the memories of the brothers. [47]

The fond memories of the toy helicopter led Wilbur and Orville, several years later, to construct their own helicopters. Each version of the toy they built became larger, and the boys discovered that the bigger the frame, the less the helicopter flew. This conclusion led Wilbur and Orville to quit their first venture into aviation research. [48]

In later years, Orville's second grade teacher, Miss Ida Palmer, remembered Orville bringing a toy flying machine to class. She attempted to discourage him in pursuing the problem of flight, but Orville did not listen to Miss Palmer's advice. In later years, he identified the toy helicopter as the object that triggered the brothers' interest in solving the problem of flight. [49]

The Wright family moved once again in 1881 to Richmond, Indiana. When he was not re-elected bishop, Milton returned to the White River Conference and served as editor of the Richmond Star. This was a monthly journal which Milton founded to promote the conservative cause within the church. [50]

Both Wilbur and Orville assisted Milton at the Richmond Star by folding papers to earn extra spending money. Wilbur, thinking the manual labor tedious, designed and built a machine to fold the papers. At this same time, Wilbur and Orville together built a treadle-powered wood lathe. Orville in later years recalled this as the first joint venture by the brothers in mechanics. [51]

While living in Richmond, Orville developed an interest in both flying and constructing kites. In another example of Orville's ingenuity for locating ways of making money, he made kites not only for himself but others to sell to his playmates. Orville's kites had frames as thin as possible to decrease the overall weight of the kite. This often resulted in the kite bending to create an arc during flight. [52]

The strong beliefs in family and Christianity that Milton and Susan brought into their marriage were conveyed and passed on to their five children. While these ideals were important to Milton and Susan, the family members did not readily communicate them in conversations or writing. Ivonette Wright Miller, Lorin's daughter, wrote:

The Wrights were a family with deep feelings and convictions. There were some subjects they did not talk about. They didn't think it was necessary. They didn't discuss what they believed anymore than they discussed their devotion for one another-and for us. There was never any doubt in our minds about that, though they never made that statement in writing. [53]

While the Wright family did not communicate emotions to each other in letters, they did keep in constant contact. Since Milton traveled much of his life, he maintained contact with his friends, family, and church acquaintances through letters. Jeannette Whitesell, a neighbor of the Wright family in West Dayton, remembered as a child noticing the large correspondence that Milton produced each day. She watched him make daily trips to the mailbox, "a fine-looking old gentleman, tall, white-haired and always buttoned to the neck in his long black coat, always wearing his broad-brimmed black hat and red bedroom slippers." In addition to the large quantity of church associated letters he sent, Milton when traveling corresponded regularly with his wife, and as the children grew, he also wrote to them. [54]

In later years, Wilbur, Orville, and Katharine kept up regular correspondence with each other and with their father when they were in different locations. One of the earliest surviving letters is an 1881 letter from Orville to his father. The letter not only illustrated the family's commitment to correspondence, but Orville's inquisitive nature.

April 1, 1881

Dear Father,—I got your letter today. My teacher said I was a good boy today. We have 45 in our room. The other day I took a machine can and filled it with water then I put it on the stove I waited a little while and the water came squirting out of the top about a foot. The water in the river was up in the cracker factory about a half a foot. There is a good deal of water on the Island. The old cat is dead. [55]

The deep and affectionate relationship between the youngest three Wright children is apparent in the childhood nicknames that they continued to use in correspondence throughout their adult lives. Known as Will, Orv, and Katie to their friends and even other family members, among the three of them Wilbur was Ullam, short for Jullam, the German equivalent of William; Orville was Bubbo or Bubs, the best Wilbur could pronounce brother at Orville's birth; and Katharine was Swes or Sterchens, both affectionate diminutives of Schwesterchen, the German word for little sister.

Being closer in age the bond between Orville and Katharine was greater than that between Wilbur and Katharine. As the three grew older, this was not often apparent, for the three siblings were a trio that stuck together. However, during disagreements and discussions, Katharine almost always sided with Orville against Wilbur. [56]

In June 1884, Milton decided to move the family back to Dayton. This could not have been an easy decision. The family was happy in Richmond, and they were located near both Milton and Susan's families as well as childhood friends. The Wright farm was located in the middle of Milton's preaching circuit and he was home more often. Yet, Milton felt it was time to prepare for the General Conference of 1885. He believed it would be easier to gather support for the Radicals in Dayton, the unofficial headquarters of the church and the home of its publishing house. [57]

This was not a simple move for the family. Susan was in poor health, and she would be leaving behind the support from her mother, sister, and friends. Wilbur was nearing completion of his senior year at Richmond High School, and the hastiness of the move prevented him from attending the commencement ceremonies and completing the requirements for graduation. The move prevented Wilbur from officially completing high school or obtaining a degree. [58]

Milton, Wilbur, and Orville packed the family goods and shipped them to Dayton on June 14. The boys, along with Lorin and Reuchlin who lived in Dayton, supervised the moving of the household items into the family's new home at 114 North Summit Street. The Wrights leased the home on Summit Street, for the house on Hawthorne Street was leased for another sixteen months. Susan and Katharine left for Dayton on June 17, and Milton followed a few weeks later after completing business requirements in Richmond. Once they arrived in Dayton, the Wright family reacquainted themselves with their old neighborhood and friends. [59]

Throughout their childhood, Milton and Susan encouraged their children to follow their individual interests. Although it appears that Susan had a stronger influence on Wilbur and Orville's mechanical and inventive interests, their father, reinforced by their mother, contributed much to his sons' fortitude. Through their encouragement, support, and guidance, both parents contributed to the industrious nature of not only Wilbur and Orville, but all the Wright children.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

daav/honious/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 18-Feb-2004