|

Denali

A History of the Denali - Mount McKinley, Region, Alaska Historic Resource Study of Denali National Park and Preserve |

|

Chapter 6:

CONDITIONS IN ALASKA IN THE WORLD WAR I AND POSTWAR PERIODS

The new park made its debut in an Alaska that still considered itself an abused colony. From the northerners' viewpoint the limited powers of their territorial government put them at the mercy of competing bureaucracies in far-off Washington, D.C. The bureaucrats' conflicting controls stifled Alaska's development. Isolated by distance and high-latitude climate from the usual amenities and choices of economic pursuit, Alaskans depended almost exclusively on the raw products of land and sea: minerals, timber, fish, furs, and game. From these products they derived both sustenance and the cash income for imported necessities that their limited frontier economy could not produce. Yet these were the very resources, along with the land itself, controlled by the distant bureaucrats.

In an address before the Annual Meeting of the American Mining Congress in 1921, Falcon Joslin of Katalla, Alaska, described the lack of progress and the loss of population in Alaska. He attributed the decline in commerce and the ghost-town atmosphere of such cities as Fairbanks to misgovernment and the mismanagement of Alaska's resources. Critical was the lack of efficient access to freeholds on the federally owned landbase. Alaska's pioneers had to depend on leaseholds or permit titles, which could be and often enough were taken away by the agents of government. Under this uncertain regime the true pioneer lost hope, leaving the land to the rapacious. Thus did the federal government's misguided conservation policies lead to perverse result: the true conservator, the freeholder, gave way to the freebooter who cared only for quick fortune at whatever cost to the land and the animals he destroyed. The weak territorial legislature, excluded entirely from such crucial concerns as land and fish-and-game laws, could only plea and pass protest enactments against the veto powers vested in Washington. As Joslin saw it, on a foundation of laws and regulations born of hearsay and inaccurate reports from visiting firemen, the Washington bureaucrats fought amongst themselves to retain powers and jurisdictions. The shadow commissions and bureaus established by the territorial governor and legislature lacked authority to rectify and coordinate administration.

Joslin concluded his essay on Alaska's governance with these words: "Naturally, this form of government is sufficient to devastate a province. It is certainly returning the Territory to the bears." [1]

Joslin's remedy for this sad state of affairs was home rule. People involved and knowledgeable in Alaskan conditions and affairs could solve the problems of transportation, revive sagging industries, open new ones, and coordinate administration of land and resources. True representation by accountable agents of government would attract solid citizens and open Alaska to development and progress commensurate with its vast resources. [2]

Joslin's analysis and prescriptions were not without merit. And they certainly reflected the sentiments of most Alaskans. More than 30 years later Territorial Governor Ernest Gruening would say essentially the same things in his book, The State of Alaska (1954), whose title reflected an objective still 5 years from attainment.

But in the World War I and postwar periods Alaska was far from statehood. Its remoteness, its small population, and the fluctuating prices of extracted products—often more economically available elsewhere—held Alaska down. (Excepting such bonanzas as the Prudhoe Bay oil discovery, these factors still moderate Alaska's economy.) In addition, outside monied interests—the syndicates and trusts that controlled much of Alaska's extractive and transportation industry—found comfort and profit in playing off competing Congressional committees and government bureaus in Washington; they minded not at all a weak territorial government that lacked power and means to regulate their activities. Similarly, home-grown Alaskan boomers wanted the benefits of government assistance but not the controls that went with it.

Beginning in 1913 the Wilson Administration had spoken strongly to Alaska's concerns. The President himself urged a comprehensive development policy for Alaska. He wanted complete coastal surveys and charting to reduce ship losses on Alaska's long and dangerous coastline; such action would help reduce shipping rates, which had been inflated by exorbitant marine insurance. In support of this initiative Wilson's Secretary of Commerce remarked on the "peculiar habits of surveying up there . . . [whereby] we have found many rocks by running merchant ships upon them . . . ." [3]

In 1914 a friend of Alaska, Interior Secretary Franklin K. Lane, had analyzed the governance of the territory in words that foreshadowed Joslin's later remarks. Lane proposed consolidation of federal functions in Alaska under a development board that would streamline administration and give Alaskans a single governmental authority for conducting business. [4]

Pieces of the Wilson Administration program did get enacted: coal lands opened to limited entry; school lands made available; chartering of an Agricultural College and School of Mines (later the University of Alaska); and authorization and appropriation of $35 million for construction and operation of the Alaska Railroad, which would open coal and community development along the railbelt into the Interior. [5]

But then the war came. Federal energies and attention, both in the executive departments and in Congress, turned from Alaska to the national emergency. Alaska's population, depleted by the war effort, would decline from 64,000 in 1910 to 55,000 in 1920, including a significant reduction of one-third of the non-Native population. In 1920 Alaska had fewer people by 12 percent than in 1900; during the same decades the national population had grown by 38 percent. Except for a wartime surge of copper mining, Alaska's economy grew shakier, dependent largely on Outside money for its major export industries: fisheries and mining. At war's end depression and stagnation gripped the territory: lack of development, lack of jobs, lack of people. [6]

In the 1920s the U.S. Congress pursued conservation measures to protect Alaska's fish and wildlife. But continuing stagnation led to closure of many federal facilities, including mining and agricultural experiment stations and military installations (including Fort Gibbon at Tanana). Not until the Depression Era and its New Deal programs under President Franklin D. Roosevelt would Alaska feel fresh infusions from the Federal Government. [7]

|

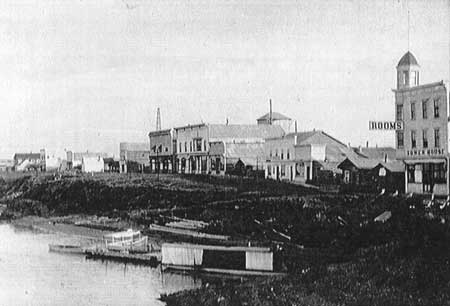

| Tanana and Fort Gibbon, at the junction of the Tanana and Yukon rivers, in 1919. Stephen Foster Collection, UAF |

Fortunately for their health and survival, specific people in specific places resist the logic of trends and general conditions. Bottomless energy and optimism distinguished the pioneers of isolated Alaska. Those who penetrated the remote Denali region possessed surpluses of both. Despite a subsistence lifestyle focused on mining and trapping, sustained by hunting and gardening, these hardy folks maintained the vision of a bountiful future. They continued their clamor for transportation relief. Access to the mineral wealth of the region—coal, gold, and other metals—would spur development, bringing progress and new communities. As water brought the rose's bloom to the desert, so would roads, trails, and rails bring "industrial advancement" to this new land. [8]

Books, petitions, tracts, and screeds of all sorts carried this theme across the country to the halls of Congress. The history of the new park and its surrounding region would largely be determined by development of a federally funded transportation system comprising the railroad and the roads and trails it spawned.

By the summer of 1922, when the first tourists came to Mount McKinley National Park, the railroad from Seward to Fairbanks lacked only one link, the bridge across the Tanana River at Nenana. A ferry in summer and rails over river ice in winter made temporary connection pending the bridge's completion in early 1923. It was now possible to make the Horseshoe Tour of Interior Alaska from the port city of Seward to the park and on to Fairbanks by rail; then by automobile on the Military Highway from Fairbanks to the ports of Valdez or Cordova. [9]

|

| Early automobile ferry, probably the Big Delta Ferry crossing the Tanana River. Fanny Quigley Collection, UAF. |

|

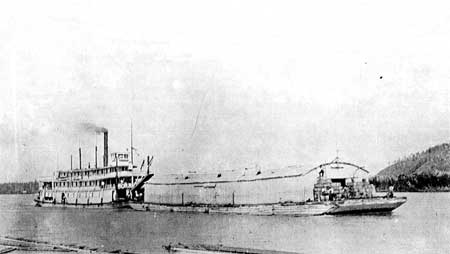

| Sternwheeler pushing a barge at Nenana, 1918. Stephen Foster Collection, UAF. |

With variations as the road net proliferated and connected with the coastal city of Anchorage, this tour system based on the arterial railroad would last for 50 years. With few exceptions throughout that period people arrived at the park by railroad. There they would be met by the park's concessioner and conveyed into the park. Not until the summer of 1972 would the new state highway from Anchorage to Fairbanks allow automobile visitors to reach the park in significant numbers. This controlled railroad and concessioner access—at peak numbering only a few hundred visitors per day—would in turn control the park's planning, development, and operations.

As feared by park managers and planners alike, beginning in the 1960s as plans for the state highway matured, the rather cozy, old-style railroad park with its 1920s-30s facilities would be vaulted headlong into the mass mobility of the late 20th Century. The stories of resultant stresses and strains upon the old facilities, especially the pressures upon the designedly primitive park road (completed in 1938); the frustrations of visitors and park people alike; and the tug-of-war between resource (especially wildlife) protection and catch-up development schemes (both within the park and on its borders) properly belong in later chapters. But because the railroad-park syndrome and the radical changes wrought by the state highway have had such structuring effect upon the park's history—from the beginning to today—this foreshadowing provides a course setting for much that follows.

Construction of the Alaska Railroad was a major engineering and logistical feat. All of the classic Alaskan conditions of remoteness, terrain, and climate opposed, obstructed, and only grudgingly surrendered to the small army that surveyed, supplied, and built the railroad.

Beginning in 1915, the Alaska Engineering Commission (AEC), an Interior Department agency run by U.S. Army engineers, deployed the men and material for the giant task. From construction headquarters at the tent city that became Anchorage, the line pushed northward to tap Matanuska Valley coal, which would fuel the railroad locomotives and machinery. Along the line two different kinds of crews did the work: ABC-hired laborers built bridges and laid track; contract "station gangs" did the preliminary clearing, grading, and excavation. [10] The crews, working toward each other from Anchorage and the northern construction headquarters at Nenana, used every mode of frontier transportation: dogs and sleds, horse-drawn double-ender sledges and wagons, pack animals, and boats. Once track was laid trains shuttled supplies for the next increment. [11]

|

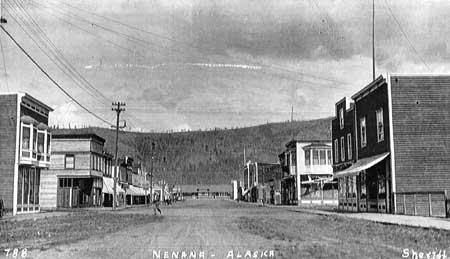

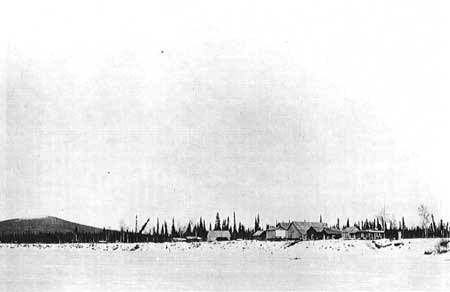

| Nenana during the 1920s. D.F. Sherriff Collection, ASL. |

People flocked to the construction camps for work. Quickly built (and as soon abandoned) roadhouses, offering amenities unavailable at the camps, sprang up along the way as workers and camp followers progressed with the railroad. Towns established at major river crossings (e.g., Nenana, Talkeetna), at division or section points (Curry, Cantwell), and at coal mining centers (Healy) would survive the construction era.

By late 1920 the gap between north and south ends of steel—between Healy and the Susitna River crossing—still stretched nearly 100 miles. [12] Centered on the Broad Pass area, this was the part of the railroad route that passed through what geologist George Eldridge had earlier described as "one of the grandest ranges on the North American Continent." Here, too, was some of the most difficult construction on the line.

These miles contain Hurricane Gulch and Riley Creek—deep incisions that required great steel bridges (still in use today). At Moody on the park's northeastern corner, a sliding mountain would require constant stabilization and periodic grade reconstruction. The 5 miles between Moody and Healy traversed the Nenana River Gorge, a place of tunnels and cliff-perched track overlooking turbulent waters that tear at the walls of the entrenched glacial river.

|

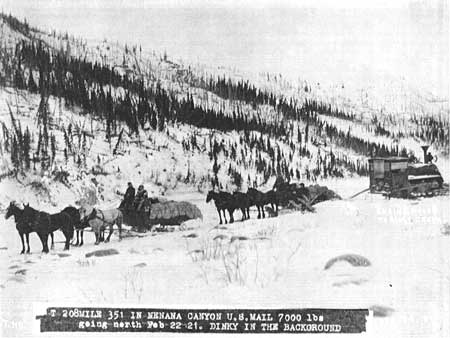

| Teams hauling the mail, and a locomotive, through the Nenana River canyon in February 1921. Alaska Railroad Collection, AMHA |

|

| Alaska Railroad engine crossing the Tanana River on the ice at Nenana, just prior to completion of the railroad. Frederick C. Mears Collection, UAF. |

In spring 1921, the AEC's chief engineer Col. Frederick Mears decided to close the gap in the line with day-and-night track-laying and trestle construction. Hurricane Gulch (Mile 284 on the railroad), Riley Creek (Mile 347), and the Nenana River Gorge south of Healy (Mile 358) posed the greatest hurdles. [13]

Standard gauge track laid southward from Nenana connected that river supply point and the large construction base camp at Healy. Now the crews forced the heavy rock work in the canyon, carving platforms for track from the cliffs, penetrating rock buttresses with tunnels. Other crews continued grading south—beyond the gorge and past the park entrance at Riley Creek to Mile 335. [14]

When winter came the Nenana River's ice made a highway for transport of heavy equipment through the gorge. Horse-drawn rolling stock, draglines, and camp equipment and supplies speeded track laying from the upper end of the canyon to the north bank of Riley Creek at Mile 347. In describing the hard push through the gorge, ABC engineer E.J. Cronin asserted, "The Pharaohs of Egypt, in building the pyramids, faced no greater difficulties and hardships than did the crews under Superintendent of Construction Bill Packer in completing this project." [15]

No less difficult had been the bridge across Hurricane Gulch, fabricated and erected for the AEC by the American Bridge Company. This single-track bridge had to span a chasm more than 900 feet across and 300 feet deep. A great arch 384 feet long provided the central support, with 120-foot riveted-truss deck spans at either end, extended at the north end by a 240-foot-long steel viaduct. Using the cantilever method, the arch was started at both ends, each end held to the shore by steel backstays. Since track and material approached Hurricane Gulch from the south, the builders had to transfer the north-end materials across the gorge by two methods: 1) cableway transfer, and 2) erecting cranes on each end of the advancing arch to lower and pick up materials from the gulch floor. An ingenious system of telescopic backstays, shims, and hydraulic jacks allowed fine adjustments so the two halves of the arch could be fitted and closed into permanent position, which occurred without a hitch. Earlier a specially made steel tape, corrected for temperature, had been stretched between the approach spans under a tension of 50 pounds to get the precise 384-foot arch-length measurement. Erection of the bridge started in early June 1921. Sixty working days later the first train passed over the structure and track-laying commenced north of the gulch. [16]

|

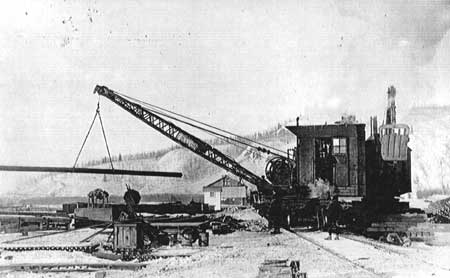

| Crane work at Nenana, ca. 1921. Stephen Foster Collection, UAF. |

|

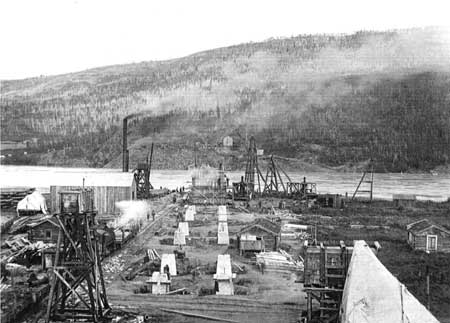

| The Tanana River bridge, at Nenana, under construction. Alaska Railroad Collection, AMHA. |

Completion of the huge bridge across the Tanana River at Nenana would wait until February 1923. But train ferries and tracks across river ice had already made the Tanana crossing operational. By late December 1921 only one gap remained to prevent trains from traveling the entire 470 miles between Seward and Fairbanks. That gap was Riley Creek at the entrance to Mount McKinley National Park. Crews from north and south had brought their respective ends of steel to the embankments flanking this deep-cut stream, but more than 900 feet separated them. The bridging of Riley Creek with a structure part steel viaduct and part timber-frame trestle focused the construction energies of the AEC, for this was the final operational link. The big construction camp on the south bank of Riley Creek overflowed with laborers and engineers. In about a month they finished the bridge and laid the last rails, thus achieving, as the New York Times of February 3, 1922, would proclaim, "the practical completion of one of the most difficult engineering projects undertaken by the United States Government." [17]

|

| Railroad bridge and sternwheelers at Nenana, during the 1947 break-up season. Alaska Railroad Collection, AMHA. |

In fact, much remained to be done. Hasty construction, inadequate ballasting, and replacement of temporary wood trestles with steel would force the equivalent of reconstruction over many sections of the line. Severe maintenance and repair problems caused by snow avalanches, earthquakes and slides, frost-heave, and other Alaska dynamics would always drain the railroad's budget. From earliest operations, deficits between income and outgo would invite critical Congressional reviews. But the government owned-and-operated Alaska Railroad did what it was intended to do. It connected Alaska's vast Interior with Seward's ice-free port, and, by ocean ships, with Seattle and the rest of the world. In conjunction with spur wagon roads and trails, it stimulated mining in isolated districts. With its low-cost freighting capacity it made possible vast, long-term dredging operations for reworking the Fairbanks placer fields. It spawned towns and agricultural enterprise. It revolutionized Interior river transportation, making Nenana the queen city of Yukon-drainage steamboating. Few informed persons expected more, and such persons wrote off the road's deficits as a debt owed to a neglected frontier, the price paid to generate social and industrial productivity in a remote and detached province. Twenty years later the railroad would become a strategic link in the winning of World War II, aiding in the repulse of Japanese invaders and hauling fuel for the aircraft ferry operations across Alaska and Siberia to the Russo-German front. [18]

|

| The Alaska Railroad during the 1930s. Prince, The Alaska Railroad in Pictures, 591. |

The railroad provided a north-south transportation backbone from tidewater to the Yukon. In the Denali region's upland country, far from deep-river ports, its effect would be multiplied by a feeder rail spur to the Healy coal mines, and wagon roads and trails that extended like ribs to east and west. This effect was intended and planned.

Col. James Steese of the Alaska Road Commission (ARC) and Col. Frederick Mears of the AEC had corresponded on this matter during the railroad's construction. In anticipation of the laying of steel the ARC conducted road-and-trail surveys and requested appropriations for their construction.

This was a mutually beneficial collaboration between the two territorial agencies, one (ABC) lodged in the Interior Department, the other (ARC) in the War Department, both run by Army engineers. The ARC had been charged by Congress at its founding in 1905 to provide transportation relief to the isolated sections of the territory, particularly those mining districts beyond easy reach of steamboat freighting. The AEC had been charged with construction and profitable operation of a railroad that would connect three small towns (Seward, Anchorage, Fairbanks) over nearly 500 miles of commercially unpopulated wilderness—with potential, but only if made accessible.

The mutual interests of the two agencies were conveniently summarized in a 1921 letter from the AEC's engineer-in-charge at Anchorage to AEC Chairman Colonel Mears:

I have read with considerable interest your exchange of communications with Colonel Steese of the Alaska Road Commission, regarding the construction of wagon roads and trails in Alaska, more particularly those roads and trails which may be considered as feeders to the new Government Railroad.

It goes without question that a main line passing through a more or less barren country, even though it may join populous sections, is working at a very great disadvantage. It, in a measure, resembles a bridge across a large stream from which there is little or no revenue and there is always considerable expense against it for operation. This, in fact, is the character of our road between Anchorage and Nenana, or shall I say, perhaps between Wasilla and Nenana. Through this intermediate section there are vast latent possibilities in the way of mines and agriculture which will produce little or no interest in the way of revenue to our road until joined to it by some means of transportation.

Engineer F.D. Browne continued with a discussion of the advantages to the railroad of tapping lode-mining districts, which had to ship bulk quartz ore to smelters:

Such a region is the Kantishna mining district, situated westerly from Mile 350 on the Government Railroad. A portion of the McKinley Park is traversed in reaching the Kantishna center of activity and a road in there, from whatever point may be selected on the railroad as a junction, will undoubtedly be one of the most favorable for the creation of an early tonnage for the road. All who have examined this territory declare that there is immense tonnage of valuable ore in sight. Even though this were not made available for some little time, it is no less important that McKinley Park be made available to the public and that a start be made in opening up the country adjacent to the head waters of the Iditarod and Kuskokwim Rivers via a route which shall pass near Lake Minchumina. Such a through line would be accessory to the proposed route through Rainy Pass to McGrath and Ophir and need in nowise conflict as two immense territories would be opened by the two different routes. This road into, and perhaps to be extended beyond, the Kantishna district, I believe, is the first and most important one that should be undertaken by the Alaska Road Commission.

..........

I believe that every effort should be made to induce Congress to appropriate funds for the extension of the railroad, and even under the assumption that this is promptly and willingly granted, that no less importance be given the necessity of improving and extending all wagon roads and trails adjacent to the railroad that they may be producing tonnage and make the railroad what it should be, i.e., a unit in the development of Alaska. [19]

|

| McGrath, on the upper Kuskokwim, in 1919. McGrath was the first sizable village west of the park. Stephen Foster Collection, UAF. |

This letter's explicit reference to McKinley Park tourist access would produce a three-way collaboration between the AEC, the ARC, and the National Park Service (NPS). All three agencies would requite their distinct objectives from the park road that connected the railroad with the Kantishna district: bulk-haul and tourist-traffic revenue for the AEC, provision of miners' transportation relief by ARC, and visitor access into the park for the NPS, which would set the standards for the road through the park and provide appropriated funds for its construction by the ARC.

Other roads and trails based on the railroad would include the road west from Talkeetna to the Cache Creek-Yentna district, a bobsled trail east from Cantwell to the Valdez Creek district, a trail from Kobe to the Bonnifield district, and various feeders off the old mail trail between Fairbanks-Nenana and McGrath, including the Lignite-Kantishna trail and the Kobe-Knight's Roadhouse trail. [20]

In September 1920 ARC engineer Hawley Sterling made a reconnaissance for a wagon road from the railroad to Kantishna. His purpose was to select the best route from a number suggested by miners in the district. Petitioners included Charles A. Trundy, U.S. Commissioner at Kantishna; K.E. Casperis, engineer for Mt. McKinley Gold Placers; and, according to ARC's Colonel Steese, "the most substantial operators in the Kantishna District," Joe Dalton, Joe Quigley, and Ed Brooker. [21]

In a 1921 letter to James Wickersham, Colonel Steese stated the objectives of ARC regarding transportation relief for the Kantishna miners: Interim relief would continue to be provided by keeping the winter dog trails open from the rail line to Kantishna, and by improving the wagon road from the Kantishna River's head of navigation at Roosevelt. The ultimate relief depended on construction of a first-class wagon road from the railroad to Kantishna. Steese noted "very violent advocacy" for various routes all along the rail corridor from Talkeetna to Nenana. (One petition called for a wagon road across main-range icefields!). With severely limited funds ARC could not indulge all these interests, but would have to choose only one best route. [22]

As it turned out, the 1920 survey and report by Hawley Sterling forced the decision on that one best route. Sterling tested two tracks. He went out by the "lower route" from Lignite to Toklat River and on to Kantishna via Clearwater Fork and Canyon, Caribou, Glacier, and Moose Creeks.

He returned by the Riley Creek or "upper route" through the high passes traversed by today's park road, coming out at what would soon be McKinley Station on the railroad.

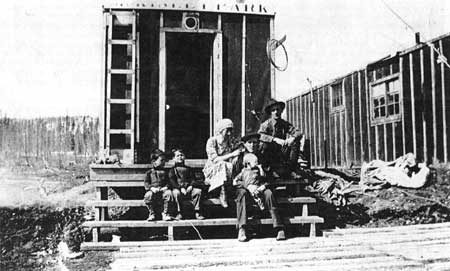

|

| The first McKinley Park station, in 1922, was a converted Tanana Valley Railroad car. R.T. Nichols, the first station agent and postmaster, is shown at right. Alaska Railroad Collection, AMHA. |

In reporting the pros and cons of the two routes (the lower route at 2200 feet average elevation; the upper at 2800 feet) he contrasted the swamps and glacial muck over 50 percent of the lower route with the drier, harder ground of the upper route. Much better timber on the upper route would aid in bridge-building over streamcourses. Despite the lower route being shorter, construction and maintenance costs would be higher, for sidehill stretches across glacial-muck slopes would require constant gravelling and reconstruction in places where gravel sources were far distant. Because of extensive dry and naturally gravelled reaches along the upper route (and better gravel sources for wet-ground base material) the initial wagon road could be easily improved for automobile and truck traffic. The lower route could never be more than a mediocre wagon road.

Upper-route stream crossings would be fewer and shorter. Better grades, generally, and less steep cutbanks at stream crossings would allow a smaller work force, for most of the work could be done with teams and graders. This was an important consideration in labor-poor Alaska.

Finally, the upper route offered a natural gateway into Mount McKinley National Park. This would benefit the railroad through tourist-traffic income. And it offered the possibility of funding assistance from the National Park Service, thus stretching ARC's limited dollars. [23]

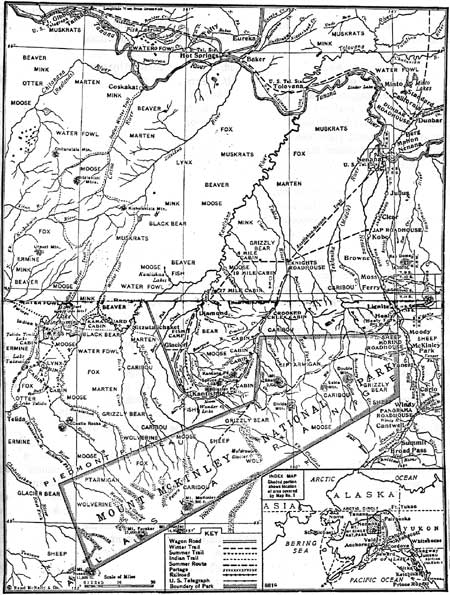

|

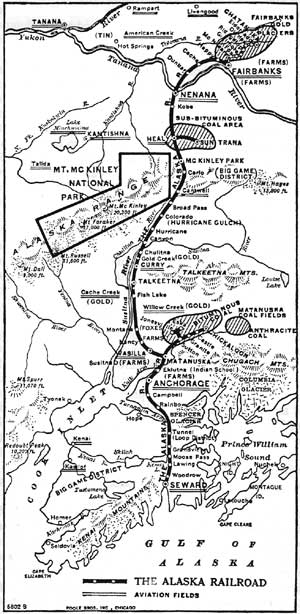

| The park and surrounding area, drawn shortly after the 1922 park expansion. Rand McNally, Rand McNally Guide to Alaska and Yukon, 8-9. |

It would be difficult to overestimate the importance for regional and park history of Hawley Sterling's report. It forged into one the three distinct interests of the ARC, the ABC, and the NPS, leading directly to the 1922 NPS-ARC road-construction agreement, which was aided and abetted by the ABC. By selecting the upper route through the park for the transportation artery between the railroad and the Kantishna district, Sterling's report produced a kind of shotgun wedding between the miners and the NPS, one that over the years demonstrated the stresses of such forced alliances.

Because it was a long and difficult project—dragged out further by skimpy funding—construction of the park road consumed ARC energies on the north flank of the Denali region. Steese's original intent to push the road southwesterly into the Kuskokwim drainage was never realized. Alternate routes, such as through Rainy Pass, never got beyond primitive trails. Moreover, upon completion and upgrading of the park road for auto and truck traffic (plus the increased reliance on airplanes in the Thirties) even river transport and winter trails in the Kantishna area faded except for occasional hauls of ore with tractors.

Thus the park road emerged as the only significant surface connection between the railroad and mining and other interests beyond the park's northwest boundary. This circumstance inevitably produced conflict between the park and these economic interests.

The eventual 90 miles of park road, bought and paid for by NPS appropriations, was from the NPS viewpoint primarily a visitor access road. Only incidentally, in that view, was it a link in an industrial transportation system, whose other links were a railroad loading platform at McKinley Station and a 6-mile spur road to Kantishna beyond the park boundary. From other viewpoints, particularly the miners', the primacy of the road's industrial function was self evident. In their view NPS restrictions to preserve the scenic and wildlife-viewing function for visitors created red tape and bottlenecks.

|

| McKinley Park station and display booth, August 3, 1930. Alaska Railroad Collection, AMHA. |

Thus a mutually beneficial and fiscally efficient interagency agreement of 1922 built a dual-purpose road whose built-in conflicts have haunted park management up to the present day. From the time of its completion in 1938, the park road has been pressed into plans and schemes to equalize its park and economic functions, and—because the road remains the only surface access to this part of the country—to proliferate its functions at Kantishna and beyond.

Today's conservation concerns over the fate of the park road can be neatly summarized: The growing momentum of added economic purposes threatens the fragile balance that allows visitors to view the park's wildlife against its mountain scenery. Given the park founders' charge to preserve this scenery/wildlife combination the NPS has had to stand in opposition to these schemes. This historical progression, with all its present portents, had its origins in Hawley Sterling's 1920 report to the road commissioners.

Despite some disgruntlement at Kantishna (particularly the protests of Charles Trundy and K.E. Casparis) over choice of the upper or park route for the main road, that decision would stand. In a letter to Trundy, responding to his advocacy of the Lignite-Toklat route, the ARC declined responsibility for that trail and the old miners' cabins on it that travelers used for shelter. ARC stated that pending completion of the main road through the park, ARC would maintain only the Roosevelt-Kantishna wagon road and the sled road and shelter cabins from Kobi to Kantishna via Knights Roadhouse, Diamond City, and Glacier. [24]

In the early 1920s mining activity began to pick up at Kantishna, [25] thus the pressure on the ARC for this route or that route, depending on the future road's proximity to the particular miner's claims. As time would prove, the old-style gold placer methods—open cuts, shoveling in, and ground sluicing—would continue until the late Thirties to be the district's mainstay. But a brief excitement came in the years 1920-24, product of new thinking and new money—some of it from Outside. Two outfits—McKinley Gold Placers, Inc., on lower Caribou Creek and Glacier Creek, and Kantishna Hydraulic Mining Co. on Moose Creek—put in major developments for large-scale hydraulic mining of bench deposits. Volume of processed material would make up for the sparse gold in the gravel—so ran the theory. But costs of transportation wrecked that notion and the big companies soon folded. New management and local partnerships took over the hydraulic operations for a season or two, but they could not make a profit either.

Improvements in ground-sluicing techniques—using automatic boomer dams to uncover paydirt—extended the lives of some placer claims and opened up a few new ones, including a revival of Joe Dalton's old claims on Crooked Creek at the north end of the district. All of these were small operations typically employing two to four men.

The legacy of these Twenties and Thirties placer operations includes the remnants of the system (dam, ditch, and siphon) that brought water from Wonder Lake to the Moose Creek hydraulicking site (opposite the mouth of Eureka Creek); the camp buildings, equipment, and workings on Caribou and Glacier creeks; and remains of boomer dams and subsequent small-scale hydraulicking at places like Twenty-Two Gulch.

As the placers flattened toward subsistence levels, lode prospects became more attractive. Joe Quigley worked and leased claims on the ridge that bears his name. The Humbolt prospect near Glacier Peak and the Alpha prospect high on Eldorado were also active. Silver-lead ore paid handsomely after World War I, which stimulated more lode prospecting throughout the district. Again, costs of transportation—particularly painful for lode miners, who had to ship their bulk ore to Outside smelters—made losers of mines that elsewhere would have shown profit. Lode gold mines, suffering the same problems, kept a few miners supplied with staples but made no fortunes. Joe Quigley, for example, grossed only $5,000 from his Red Top claim in the period 1920-24. Charles Trundy fared no better.

In 1920 Joe and Fanny Quigley found promising copper-zinc deposits at Copper Mountain (now Mount Bielson) within the park. Hundreds of claimants staked this and nearby mineralized zones, including Slippery Creek in the Mount McKinley foothills. But commercial values eluded the miners, and most of these claims—often after years of hopeful assessment work—were abandoned and lapsed.

By early depression days the population of the Kantishna district and surrounding mining areas had dwindled to less than 20 souls. In 1930 only two miners wintered over at Eureka. One trader and one trapper lived at Diamond. This was a far cry from the distant days of stampede—a cabin or two with smoke in the pipe, the rest falling and smothered with alders.

Quigley's serious injury, in a 1931 tunnel cave-in, ended his underground mining career. But his prospect there would pay handsomely in a few years.

By the mid-Thirties low metal prices—tagged on to high transportation, equipment, and labor costs—had just about whipped mining enterprise in the Kantishna and surrounding districts.

Then came a series of breaks that produced the Golden Years of Kantishna mining, 1937-42. President Roosevelt raised the price of gold to $35 an ounce. The park road reached Kantishna. And the depression's duration had spawned a roving army of cheap labor.

Kantishna's resurgence in the late Thirties and early Forties broke all production records for gold mining, indeed surpassing district totals of all the years preceding. Central to this revival was the Red Top Mining Company's 1935-38 development of the Banjo Mine under option from the Quigleys. When production started in 1939 the plant included road, airstrip, mill, assay shop, bunkhouses, blacksmith shop, and other facilities to tap the commercial-grade gold ore in the Banjo vein. Never before had commercial-scale milling of lode gold been attempted in this district. Banjo became the fourth largest lode mine in the Yukon Basin, producing in the years 1939-41 more than 6,000 ounces of gold and 7,000 of silver. As World War II approached the Banjo's success raised hopes that the district's marginal days had ended.

Lode-mining excitement extended to the antimony deposit at Stampede Creek, discovered long before but latent until the approaching war boosted prices for this critical metal. By 1941, 2,400 tons of ore yielding 1,300 tons of metallic antimony had been shipped from Stampede, making it Alaska's prime producer of this metal and one of the largest in the country. Earl Pilgrim, operator and eventual owner of the Stampede Mine, would be a continuing force in the Denali region's history, as will be demonstrated in Chapter 8.

Placer mining, too, resurged in this period. Reworking of previously mined creeks with new methods—notably the Caribou Mines Co. work with dragline and other mechanized equipment—gave a foretaste of modern mining procedures that would become standard in Alaska placer fields after World War II. These techniques allowed enormous increases in production. Kantishna's aggregate placer-gold return of $139,000 in 1940 broke all previous records. The district's three all-time high production mines operated during this period.

Then, again, came a war. Transportation, manpower, fuel, supplies, and equipment all funnelled to the war effort, effectively crippling the boom. It died with the wartime order that banned gold mining as non-essential. A few small operations not covered by the ban limped along through the war years. Limited production, using bulldozers, loaders, and small-scale hydraulic outfits resumed in the late Forties. But the golden years were over.

Even the strategic-metal antimony mines on Stampede and Slate creeks—at first stimulated by the war—suffered from wartime transportation and manpower limitations. The drop in demand for strategic metals after the war would dampen further the marginal interest in Kantishna's remote antimony mines. The small tonnage of ores and concentrates these mines managed to ship meant little in the general mining collapse, which reached nadir in the Fifties and Sixties.

It would be 30 years before the Kantishna would know another boom, and that really a boomlet. In the mid-Seventies, after abandonment of the gold standard the price of gold would soar to unimagined heights and the trek to the Kantishna Hills would again pick up its pace.

Other mining districts in the isolated Denali region experienced similar though locally varied histories in the years between the wars. As at Kantishna, the continuity of small outfit mining bridged the lean years between short-lived and usually disappointing excitements.

Life in the Kantishna carried on despite the somber progressions of history. Two fresh-eyed visitors in the early Twenties left verbal snapshots of day-to-day events that otherwise would have gone unrecorded. One, Mary Lee Davis, was the first woman to reach the camp via the yet unmarked park-road route over the high passes. She accompanied her mining-engineer husband on a business trip that, for her, was a pilgrimage to the land of The Most High. At the request of a prospector, the couple veered from course so John Davis could assess the man's claim. Mary wrote of long travel into the headwaters of a remote creek, "up the blackest gulch I think I ever saw, cracked open into the heart of barren hills that grew more eerie and more shadowed the further we reached into them. The 'cabin' was a mere hole blasted from the face of a mountain, and our 'bed' was a mere ledge, down which rock water dripped all night." [26]

Again en route they passed a cold night on spruce boughs and woke to a celestial sunrise that revealed the "unutterable majesty," the "patient stillness" of Mount McKinley. "A streamer of cloud, the hallmark of the very loftiest summits, drifted above like alder smoke. One seemed to see the very gate of heaven thrust open . . . with golden and crimson light draping this highest altar." [27]

Mary spent most of her Kantishna time with Fanny Quigley—and most of that time tramping the hills with pack dogs, for, said Fanny, "I can't be shut up in a cage." Her conversation ranged the spectrum of a frontier woman's life, from hauling logs for firewood to hunting, one of her favorite pursuits:

One hunter is better than two when you're after big game, because you have to be changing your mind all the time. You'll change a whole day's hunting plan in a second, while one foot is in the air just ready to put down—if your eyes or ears tell you something new. And you can't be bothering to explain to the other fellow all about it. When Joe and I hunt together, we hunt separate. And you don't want to waste shots. It costs too high, in lots of ways. I'd be ashamed not to fetch in a hundred pounds of meat to a cartridge. A 30-30 is big enough artillery for black bear or moose, but a 30-40 is a heap sight better. And caribou, though they aren't large-bodied, will walk off with a load of lead. That's serious when your rifle means eighty per cent of your grub-stake, and you have to make every shot count. Quick death means clean butchering; and that counts, too, when you've got a carcass to handle alone, like I do. Heart, brain, or spinal cord is the mark. One well-put bullet is enough—or should be! A shot in the guts means a messy job of butchering, if you're out for meat, and a flank shot ruins a good hide if you're out for fur. You may be thinking of the mercy of it—that's open. I'm thinking about grub-stake. [28]

Years later, after Joe's crippling mine accident, while Fannie carried the whole load with the help of her dogs, she would write to Mary: "Went down six miles for some meat I killed. Then I have about fifteen cords of wood to haul, so you see when night comes I am tired." [29]

In 1922-23 Ed Brooker, Jr., took time off from his senior year in high school Outside to join his parents in Kantishna, where Ed Brooker, Sr., was U.S. Commissioner and Postmaster. [30] After riding the train from Seward young Ed was greeted by his mother at McKinley Station where she had been working as a cook at Morino's Roadhouse. Together they travelled by pack train through the park to Kantishna.

As Kantishna's commissioner, the elder Brooker was judge, chief law officer, mining claim recorder, and, generally, "the Government" as it existed in bush Alaska in those early days. He had just finished leading a posse that subdued and shipped out a deranged German miner who had been shooting up the Glen Creek camp. When young Ed and his mother arrived unexpectedly at Brooker's tent on Friday Creek at midnight, the youngster shook the tent frame without saying a word, wanting to surprise his dad. Still jittery from the ordeal with the German, Brooker cried out, "Who's there?" Ed didn't answer, but shook the tent again, whereupon he heard: "Tell me who you are or I'm coming out shooting!" "Needless to say," Ed recalls, "I spoke up. We had a happy reunion."

That summer of 1922 Ed and his dad built a log cabin on Friday Creek, on the flat where it breaks out of the hills. They made it eight logs high so they would not have to stoop when they moved around inside. Frank Ten Byck, who also lived at the foot of the hill, helped them saw lumber for the roof, which they tarpapered and sodded.

Father and son climbed Monument Dome often that summer, so called because of the USGS survey marker on top. It is now called Brooker Mountain after Ed's dad. Ed accompanied Joe Quigley and "Dirty" Pete Pemberton on a trip out to the railroad and Fairbanks so he could visit old school friends. "Joe was a regular mountain goat in hiking, and Pete and I were dragged out at the end of each day. We went light and ate light. This was the way Joe traveled." Joe stayed on in Fairbanks so Ed and Pete traveled back without him over the still unmarked trail through the park. They carried a rifle for bear protection but didn't need it. "We saw all manner of wild game which was a thrill."

During winter keeping body and soul together was the main activity at Kantishna. When weather allowed, the miners used the frozen, snow-covered ground as a highway to ship out silver ore for the Tacoma smelter. Hawley Sterling, who would later supervise ARC construction of the park road, was one of the miners; Little Johnny Busia (Boo-SHAY), a Croat who had come over from Europe some years before, was another.

One time Jim O'Brien and Mace Farrar left Copper Mountain by dog team, bound for Kantishna in minus 40 degree weather. In camp on the McKinley River Mace chopped his lower leg to the bone when his axe glanced off a frozen cottonwood. He quickly smeared sugar on the wound to stop the bleeding. Then O'Brien loaded him in the dog sled and drove him non-stop more than 100 miles to get medical help. "Mace was OK again in a few weeks."

Ed clerked for his dad in the latter's role of recorder for the mining district. Ed's description of the recording procedure shows how miners established their claims:

When one stakes land and calls it either a lode or placer claim, a location notice is placed on a stake at the point of discovery. Usually, this piece of paper was put in a Prince Albert tobacco can fastened upside down on the discovery stake (protection against the weather). To be binding and legal, it was (and is) necessary to take the location notice to a recording office where a typed or hand written copy is made and filed in a recorder's book.

Ed notes that these books were legal size and loose leaf, so notices could be typed and inserted. He used his dad's old portable Royal, commenting that the typewriter under his management at age 16 made many mistakes. Miners had to perform at least $100 dollars worth of work each year on each claim to retain their rights, then had to so swear by affidavit, which was also copied and filed in the recorder's book. Many recorders could not type, so wrote their entries; among them were calligraphers who produced "real works of art."

The isolation of the winter camp—125 miles by winter trail from Nenana—forced the miners to hunt wild meat for subsistence. Besides, Ed comments, "Canned corned willie gets a bit tiresome." Spurred by the need for fresh meat Ed and John Bowman, who also lived on Friday Creek, set out with dogs for Copper Mountain to get a sheep. Mace Farrar and Fred Jungst—grubstaked by Ed's mother to prospect that mountain—had a tent below it in the Thorofare Basin. There the hunters aimed, planning to use the tent as a base camp. A sudden blizzard caused white-out conditions, and after miles of zero visibility, guiding themselves by contours and wind direction, the half-frozen nimrods luckily stumbled onto the tent. It was 10 miles from nearest timber, but the absent owners had left dry wood and shavings by the stove for quick fire and warmup, as demanded by the Code of the North. Next day they begun climbing to the wind swept ridges, where the sheep could dig down to forage through the shallow snow. The constant wind had packed Copper Mountain's snow slopes, forcing the hunters to kick steps in the plaster-like crust. After a day of futile labor, and another night in the tent, they returned to Friday Creek empty handed.

John Bowman was used to failure. After making a small fortune in the Klondike, he lost it in the saloons of Dawson. Subsequent mining in the Koyukuk district, 400 miles north of Denali, and in the Kantishna, had not improved his finances. But somehow he always got enough booze. Ed recalls a Bowman birthday party in mid-winter. One of his cronies on Slate Creek constructed a wooden birthday cake, then covered it with tasty frosting. Following a convivial dinner, Bowman tried to cut the cake, finally giving up with the comment, "It musht be froshen."

Commissioner Brooker had finally married Joe and Fanny Quigley after they had consorted for many years without benefit of nuptials. It was rumored in camp that the commissioner, lacking a Bible, sealed the sacrament with a Montgomery Ward catalogue. Upon recordation in the commissioner's ledger, however, all was legal and binding.

Personal feuds and friendships tempered neighborliness at Kantishna, as elsewhere. In 1954 Johnny Busia told Ed Brooker that around 1950 only Johnny, Joe Dalton, and Pete Anderson wintered in Kantishna. Dalton had given Johnny trouble over mining claims. So when Dalton died, Johnny—in his words—"wrapped him in a blanket and put him in a shallow hole with an old board to mark his grave." Later, Johnny found his friend Pete Anderson dead in his bunk: "I made a good box, put Pete in carefully, dug a good hole, buried Pete and put a good fence around the grave and put up a good marker."

Ed's mother told him of the flu epidemic that spread from Fairbanks to Nenana in March 1920 when "bigshots" traveled through by train and broke quarantine. His mother closed her restaurant to serve as a volunteer nurse. Whiskey, used by some as a cure, proved negative. The Nenana Indians were nearly wiped out. "Wooden boxes (rather than coffins) could not be built fast enough. Several bodies were put in a single box."

When Ed went into Nenana, he attended Joe Burns' movie house, where Vic Durand provided music to accompany the silent film on the screen, "playing the piano with his feet, playing the mouth organ from a rack over his shoulders, and playing a violin with his hands." Fanny Quigley got into Nenana about once a year to see a film. "Fanny, with a dress on top of her overalls would, in a loud voice, explain what the movie was all about and what was going to happen next. No one had the nerve to ask her to keep quiet."

About midway through the 1922-23 winter, Ed Brooker departed to resume his schooling:

Dad and I loaded back packs with grub and blankets and started walking to the Alaska Railroad and Nenana from which I could go outside. We elected to go out with the carrier of the U.S. mail who made the 125 mile trip about once a month using a single horse and a type of sled called a double ender. This was a flat bed job about three feet wide and approximately 14 ft. long. The winter trail led north a few miles beyond the Kantishna foothills and east to Healy station on the railroad. I'm guessing that we made about 20 miles each day and had cabins of one sort or another to stay in at night. One stop for the night was at Knight's Roadhouse on the Toklat River. A Mr. and Mrs. Knight with one son had lived here for a number of years. In summer they saw no one because the terrain both east and west of them was swamp, and mosquitoes, almost impassable. They were self sufficient with their garden, their game and perhaps some fish, though the Toklat River is muddy.

Their place stands out because it was the only stop we made where the cabin was warm when we arrived and we did not have to cook our own grub. In passing, I have heard that the Knight family stayed on for a number of years till both Mr. and Mrs. Knight passed away and were buried by their son. I have lost the story of the son.

In due time we arrived at Nenana, Dad put me on a train bound for Seward (on the coast) where I boarded a salt water ship for Seattle. Again, there was a long tedious train trip from Seattle to Palo Alto, but this time, I had a bit more experience behind me. Dad went back to Friday Gulch where Mother and he spent the winter.

Recent correspondence with Ed Brooker, in his eighties a man of sharp recall, has helped resolve the construction date of the two-story log structure known locally as the Kantishna Roadhouse. According to Ed, coincident with the post-World War I mining boomlet, spurred partly by a pegged price for silver, a man named Wilson along with his wife and child, came to Eureka (the early name for Kantishna) about 1919 or 1920 and built the two-story log cabin for his family. Wilson preceded Ed's dad as Postmaster and U.S. Commissioner in the Kantishna. [31] These remembrances are independently supported by a telegram dated March 29, 1921, to Col. James Steese requesting ARC's completion of the Roosevelt-Kantishna road, and listing concerned citizens of Kantishna and Nenana as signatories. Joined with familiar names such as Joe Dalton, the Quigleys and the Hamiltons is the name and title: C HERBERT WILSON COMMISSIONER. [32] A USGS photograph by geologist P.S. Smith in 1922 shows the two-story structure at the Eureka townsite surrounded by tents and small cabins. Another informant, Art Schmuck (presently of Nenana but formerly a Kantishna miner) recalled to this author the structure's door-lintel date of 1919 when he first saw it in 1955. The carved date on the lintel (no longer in place) reflected traditional practice for noting a cabin's construction date. The carved 1919 stuck in Art's memory because that was the year of his birth. With all of this evidence assembled we can state with certainty that the cabin was in place by summer 1922 (from the photo). And, by way of the Brooker and Schmuck remembrances, plus the supporting wire, we can assign with reasonable certainty a 1919 or 1920 construction date. The contextual occurrence of the 1920-1924 mining boomlet, which attracted professional "boomers," including Ed's dad, is also supportive of construction during this period. The building's ongoing roles as post office (Johnny Busia always called it "the post office"), as informal roadhouse (a place where visitors not otherwise accommodated could spread their bedding), and as community meeting place lends substantive significance to "the Roadhouse."

Ed Brooker's life spans the revolution from 19th Century to 21st. In his reflections on those long-ago days at Kantishna he wrote a simple profundity that riveted this writer: "One thought in this account is that, never again, will children be born and grow in an environment without cars and airplanes, but rather with horses, dogs and their own two feet."

Distinct from the older mining camps, the railroad created new towns that began as construction camps and persisted as trading and transportation centers. Nenana, Cantwell, and the revived Talkeetna illustrate this progression. Healy, just north of the park, also got its start as a town with arrival of the railroad builders. Its continuing history would rest on a combination of railroad operations and mining of the great coal deposits bordering Healy and Lignite creeks, which opened up with the advent of railroad transportation.

Healy's early settlers came in the train of strikes at the Bonnifield and Kantishna fields. Soon appeared a roadhouse and a store, a moonshiner's still, a cafe, and the cabin of a commercial meat hunter named Colvin who also trapped and guided. As more trappers and prospectors came into the camp, they settled near Colvin's cabin on the Nenana River bluff opposite the mouth of Healy Creek. The ABC's Construction Camp 358 (from the railroad milepost) suddenly picked up the settlement's pace. Flanking Camp Creek was a big camp of 120 people, a construction headquarters designed to push the rails through the Nenana Canyon. By 1920 the AEC had built dormitory, mess hall, hospital, store, warehouse, barn, and blacksmith shop. Thus the straggling settlement transformed into a railroad "company town." The imminence of the railroad's completion spurred development of a succession of coal mines: up Lignite Creek, in the Nenana River terrace underlying the railroad camp and townsite, and about 4 miles up Healy Creek at Suntrana. The greater Healy-Suntrana community was evolving into a dual company town as a railroad and coal-mining center.

Once the line was completed freight trains overnighted at Healy. Passenger trains overnighted at Curry to the south, but stopped for lunch at Healy, where as many as 200 passengers filed daily into the new railroad-hotel dining room. Singleton's private roadhouse-hotel deferred to this modem accommodation, becoming a store where railroad workers swapped yarns with Healy's old-timers around the pot-bellied stove.

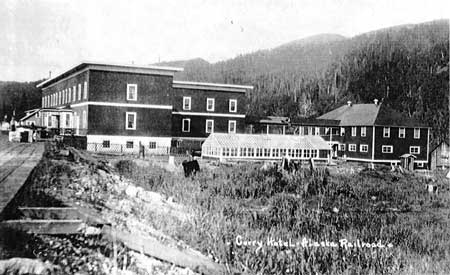

|

| Curry Hotel, on the Alaska Railroad near Talkeetna. Herbert Heller Collection, UAF. |

At the end of World War II the railroad reestablished Healy's center about one-half mile north of the old depot and town, which had suffered a fire that destroyed the hotel. More urgently, the settlement, perched on the eroding river bluff, was sliding into the water. What was left of the old town was torn down and scattered, except for Colvin's cabin, which was guyed to its precarious overhang for sentimental reasons.

Railroad cutbacks of recent years led to the operational demise of the second-generation railroad depot, hotel, and utility functions. Except for the concrete-block engine house the buildings were auctioned off and moved. Today, trains pass through but seldom stop. With opening of the Parks Highway in 1972, Healy began its second relocation, now centering on the highway 11/2 miles west of the river. [33]

In 1922, Mining engineer John A. Davis (the same who in 1921 journeyed to the Kantishna with his wife Mary) documented the shift in the nature of Denali region coal mining—from small-scale local to big-scale export—with the coming of the railroad. He reported that the Healy River Coal Company mine at Suntrana was the sole producer of coal in the Nenana fields. A 4-mile-long railroad spur line, completed that year, now connected the mine with the mainline of the railroad, and bulk shipments could begin. The earlier hauling of coal from mine to railroad—by horse-drawn sleds in winter and tractor-drawn wagons in summer—could meet local AEC and domestic needs. But it took the mine-mouth railroad to establish the bulk market in Fairbanks. [34]

Once that market was established—for Fairbanks' power and domestic uses, and for dredge and dragline placer operations in surrounding gold fields—the underground Suntrana mine would weather Alaska's boom-and-bust economy for 40 years. (World War II increased the demand for coal, and soldiers helped man the mine and the railroad.)

Today, the successor Usibelli Coal Company employs a giant dragline to strip-mine the vast deposits between Lignite and Healy creeks (the underground mine at Suntrana flooded in the early Sixties). Long trains load at a slow roll through a modern tipple opposite Lignite Creek, whence the coal is transported to Seward, then loaded in ocean ships bound for Korea.

Community history and Healy and Suntrana included founding of one-room schools in 1937 (Healy) and 1942 (Suntrana). Before then children studied by correspondence, as was (and still is) typical in isolated bush communities.

The poor road between Suntrana and Healy and lack of an automobile bridge across the Nenana encouraged motive innovations. In the late Thirties one boy ice-skated the frozen creek from Suntrana to Healy for his classes. The Healy River Coal Company rigged an old truck with railroad wheels to shuttle local residents across the railroad bridge. This conveyance, called the Doodlebug, also took ladies of the evening to the Goat Ranch near Suntrana on payday weekends. "Goat Mary" Thompson had opened a beer parlor there in 1935. Her establishment converted to a brothel when payday came. One informant told local historian Beverly Mitchell that her first husband went up to the goat ranch one night "to settle a disturbance." When he failed to return she went up herself and shot the place up with a shotgun, whereupon several customers in various states of undress cleared the premises.

More typical of community recreation were the practical pastimes of hunting, gardening, and berry-picking. The self-sufficient residents of these isolated communities filled evening hours with readings, dramatic presentations, cards, and dancing. Summer holidays were observed with baseball games and community picnics. [35]

To provide a base for railroad construction, the AEC laid out the Nenana townsite and built the yards, government structures, and a hospital. The new town joined the Indian village of Tortella and St. Mark's Episcopal Mission (est. 1907) at the confluence of the Nenana and Tanana rivers. By 1920 what had started as the railroad's northern construction headquarters had grown to an Alaskan metropolis of more than 600 people.

Private businesses served and supplied the AEC and its workers. Other entrepreneurs laid the groundwork for river transportation systems, which, upon completion of the railroad from Seward, would make Nenana the chief port of the Yukon-Tanana drainage. Known as the Hub City of Interior Alaska, this crossroads of rail and riverine transport gave access to the world's products, brought first by ocean ships to the railroad's southern terminus at Seward.

For the isolated camps and settlements of the northern Denali region—their own industry limited to frontier blacksmithing—the crated machinery in Nenana warehouses meant a future of progress and prosperity. Here, too, shined bright lights that illuminated the trappings of civilization: hotels, taverns, restaurants, and a high-class billiard hall. Groceries, hardware, clothing, and modern domestic fixtures filled the racks and floors of Nenana's stores.

During the early history of Mount McKinley National Park—its orientation northward as dictated by the Alaska Range—Nenana's goods and services provided a mercantile Mecca, a chance to get out of the bush and meet old friends, and medical help unavailable on the far creeks. [36]

Some of the men on the far creeks—the lone or partnered trappers—looked to the trading centers only for bare necessities: ammunition, steel traps, and a few staples. They were going backwards in time, trying to find in Alaska a last resort for the mountain-man life that had ended in the Rockies a century earlier. One of these, Fabian Carey of the Minchumina area, described in later years the rewards of this historic lifeway: "Only a handful of us live to fulfill our boyhood dream of following the far trails and seeking lost horizons. . . . My blazes are weathering at many a remote campsite and along many an unmapped stream and mountain glade. . . . I am well content." [37]

Perhaps less romantic, less conscious of reliving a past era was the austere Hjalmar "Slim" Carlson. One story about him shows the difference between his kind of loner and the camp and community people—who, though on civilization's edge, formed a loose society that sought progress and its benefits. It seems that Joe Quigley went over to see Slim at one of his cabins on Birch or Slippery Creek, taking some coffee as a treat. As the two men sat down to a meal of wild meat Joe offered a steaming cup to Slim. He refused, saying that he could not afford coffee or tea, so didn't want to taste it and then be unhappy about not having it later. His usual hot drink was Hudson Bay tea brewed from the leaves of a local plant. [38]

A Native of Sweden, Carlson had immigrated to the United States as a youth and made his way across the country to the Northwest where he worked in logging camps. He came to Alaska in 1914 for railroad work, and in 1918 crossed over Anderson Pass to the sheep hills and McKinley River country north of Mount McKinley. For several years he prospected and worked as a mine laborer in the Kantishna, but finally decided against them as uncertain and not worth the effort, given camp prices. So he settled into hunting and trapping. Establishment of the park would force him northward to the Castle Rocks area. Later he trapped along Birch and Slippery Creeks. Cabin remains and place names within the old and expanded park trace the course of his wanderings. [39]

Carlson was a practical man. Once he walked up Muldrow Glacier with an old dog, thinking he might climb the mountain. Near the head of the glacier he contemplated the distance yet to go:

I said, my goodness, what the dickens, I got nothing up there. Why should I go up there? I decided, I'm going to go back again, there's no use for me to go up there, but to look around . . . . Well then I went down to my camp again. Took it easy and stayed home a few days.

Slim got his meat in the fall ("caribou as thick as buffalo on the plains"), trapped until it got too cold, then hibernated in the cabin until it warmed up a little in February. He took his furs to trade for supplies in Nenana: '"nothing but flour and sugar and a little salt . . . . That was just about all I could afford to buy. I almost lived on the country. I made my own clothes out of caribou and moose skin."

Carlson was hard and strong. Cold didn't seem to bother him while on the trail. One time he met some Indians while driving his sled "with no hat or cap on me, no coat, and plenty warm." The Indians were freezing and told him that he must be a tough man. "And I probably was."

Once while sheep hunting near McGonagall Pass, Slim found some boxes of tea left by early mountaineers. That night he cooked up some sheep and brewed a big pot of tea. Next morning he had terrible diarrhea ("thought I was going to die"). Was it caused by the sheep meat or the old tea? Carlson's friend Slim Avery was expected at the hunting camp the next day. Avery drank tea morning, noon, and night. So before Carlson took off to hunt, he left the tea out. Avery arrived and helped himself to a kettle-full. When Slim got back he observed that Avery seemed to be feeling fine, then told him about the diarrhea. Avery laughed at the joke on him—Carlson's testing the tea on him. Then, applying the logical process of elimination, they blamed the sheep meat and brewed another batch.

Trapping right under the mountain did not pay. Slim got only a few mink and wolverines. About that time, too, in the early Twenties, the park rangers began cruising into his territory. So he moved north to the woods, beyond the park boundary. There he hunted black bear, rendered their fat ("just as clear as the regular lard you buy") and sold what he didn't need to the families at Kantishna for 40 cents a pound.

It was about 1924 that Carlson left his cabin on Clearwater Creek in the park. He first built a cabin at Castle Rock, then bought out Gus Johnson's productive trapline on Birch Creek, where he built a fine home cabin. Yet later, the overflow and flooding on Birch Creek impelled him to shift over to Slippery Creek where he built another big cabin. This was rich country and he "made it pretty good after that."

Slim liked this independent life with nobody to argue with or tell him what to do. He left prospecting and wage labor behind to trap exclusively. Shortly he mastered the trapper's art, devising his own techniques after exhausting the arcane scent and set formulas published in trappers' books and magazines. Fur prices were high in the Twenties: $80 for a red fox, $45 to $60 for a lynx. Marten were closed then, but sometimes one wandered into a trap. "Of course you were supposed to turn them into the territory, and I guess most of the trappers did." With good trapping, high fur prices, and plenty of caribou it was a good life.

When caribou declined in the Thirties, particularly in the park in the vicinity of his old Clearwater cabin, Slim rejected the theory that wolves were to blame. "There was very few wolves up there." He figured that wolves had got a bad name, and he did not favor the bounty for their control. He speculated that the caribou had just migrated out, shifted their range.

In those days a good salmon run came up Birch Creek. Slim trapped enough fish to feed his dogs, so he didn't need to kill deer for them.

Living by himself, and with only 3 or 4 other trappers scattered in the flats north of the park, Slim seldom saw anyone except during town visits. People in Nenana wondered how he stood it, why he didn't go crazy. "But it didn't interfere with me at all. I had no trouble there . . . . I never thought of it."

But one thing, I always was busy, always had something to do. In the summer when the mosquitoes was so thick, well I didn't rush out and cut no trail or make no cabins then, but so soon as they thinned down a little I was on the trail and went out the trap lines and scouted over the country and looked around all the time. Always busy.

Slim remembered that mosquitoes seemed more vicious then. And no one came up with any dope that worked. In fact the bugs homed in on the various mixes of lard and Creolin and other ingredients that people tried. The dogs suffered horribly. When Slim put mixtures on them, though, they just licked them off. Nets, hats, gloves, and the thickest underwear you could get were the only protection.

Once in a while something happened that made him blue (like when he axed his thumb off and nearly bled to death) and he wished he could talk to someone to shake it. But usually he just worked harder and the blues went away. Sure he talked to himself, but he didn't come back with feisty answers. Slim said that was the time to get out, a sure sign that a man had got "bushed." The secret was a nice disposition and not being the worrying kind.

Slim's adventures included scrapes with bears, but mainly he tried to get along with them as fellow travelers in the woods. One September he killed several caribou, then went back for his dogs to pack in the harvest. Meanwhile, a big grizzly had taken over his kills. Slim didn't want to mess with the bear, but he did want his meat. So he loosed the dogs, which got into a running, dodging battle with the bear. While this went on Slim built a temporary 12-foot-high cache in the trees. There he put his meat to freeze and be retrieved later.

Once Slim caught a handsome black wolf in a trap. He was caught by two toes and couldn't get away. "So I sat and talked to him for a while, and he wagged his tail to me and kind of whined . . . . I talk to him just like a big man. I got to kill you, that's all there is to it." He had tried to release the wolf, but it grabbed his leg in its jaws, not breaking the skin. That scared Slim, so there was nothing else to do, though "I hated like the dickens to kill him."

Slim got on well with the Indians. He was glad to see them when they came by ("because I never seed no body else") and he always laid a big spread for them. If he had something they needed he gave it to them, if he could, and accepted no pay even though they offered. He respected them and what they did; they respected him and his trapping territory.

Slim Carlson died in 1975. His life in the country had spanned nearly the entire history of the park. Fittingly, friends at Minchumina—where he spent his last years—buried his ashes near a lake called Lonely, under the shadow of Mount McKinley.

As the modern world moved into the Denali region, the environment of the Native people underwent drastic change. These shifting conditions, many of them devastating to the lifeways of traditional people, called for radical adaptive responses. Change and movement had distinguished Native culture long before white men came into the country. But the acceleration of change brought by the newcomers, and the breakdown of protective isolation—both physical and cultural—severely distorted the patterns of Indian life.

Even in the remote region north of the Alaska Range disease had early wreaked havoc with the Kolchan, Koyukon, and Tanana bands. Smallpox brought by 19th Century Russian and Yankee traders and travelers had spread into the Interior along the rivers, reaching remote places by intermediate Native traders. By the turn of the century the Kuskokwim-Tanana Lowlands had suffered significant population losses and relocations. Hudson Stuck noted in 1911 that the Minchumina people were a weak band of survivors, most of them destroyed by measles in 1900 and diphtheria in 1906. Influenza in the 1920s and 1930s, along with hideous forms of tuberculosis, further depleted the region's Native population. [40]

Bands and families regrouped and consolidated. Some went to Nenana or villages on the Yukon. Others grouped together at Telida and Nikolai on the upper Kuskokwim. Once populous seasonal camps such as Bearpaw, Birch Creek, and Toklat now numbered only one or two families comprising the survivors of many families. Nearby cemeteries held the relatives who made up entire family trees, now reduced to only a few living representatives.

For the survivors, the influx of gold miners, explorers, mountaineers, and other travelers on the Nenana-Kantishna-McGrath trail had brought temporary economic opportunity. The services rendered by the Indians in transport, accommodations, and provision of meat made them functional in the evolving economy. Cash earned from these services buttressed their basic economy of trapping, hunting, and fishing.

But growing dependence on the cash economy had its downside. Time on the land for family hunting and fishing—and for training young people in these arts and skills—decreased. Individualized hunting with rifles replaced communal hunting patterns, which weakened the social elements of the hunt: ceremonials, family integration through participation, joint processing of the harvest of the hunt, and the sharing of products amongst all members of the society.

Trapping itself, though a land-based activity, accentuated dependence on cash income. Trapping took time from hunting and fishing, thus forcing more dependence on trading-post foods. Money spent for store food was wasted. Native food offered better nutrition—physically, socially, and spiritually.

In time fixed villages replaced the seasonal rounds and camps of semi-nomadic tradition. The family stayed home while the hunter-trapper roamed. In-place domestic functions were different from those of the nomadic family. Old social roles and integrative divisions of labor—necessary when the whole family moved from camp to camp—ceased to apply.

From the fixed villages, fast travel (as distinct from deliberate seasonal migration) was required to get to hunting places, to run extensive traplines, and to visit towns for trading. This style required more dogs, more dependence on fish to feed them, less time for the season-long hunts in the upland caribou ranges. Lacking game meat, the family itself depended more on fish as the staple food. The adoption of fishwheels about 1918 contributed to removal of families and bands toward the big rivers where these large contraptions could be used. These movements took the people farther away from the highlands bordering the range. Thus, even before World War II, except for a few families pursuing more traditional patterns in the Minchumina and near-rivers area, the Indian population of the northern Denali region had largely evacuated to its fringes.

A few hunters and trappers still made seasonal forays in the northside highlands. They came from Minchumina, Nenana, and Telida. Men from Nikolai still hunted sheep in the mountains north of Rainy Pass. But the old rounds that had long led whole bands of hunters to the very foot of the Denali massif were essentially over by the time the new park became operational in the early Twenties.

Both north and south of the range, white miners had occupied the near foothills bordering the future park. Some of these stampeders, cursed with barren claims, shifted to full-scale market hunting to supply their luckier fellows. When the early rushes ended, the remaining miners turned to a combined mining and subsistence lifestyle, with hunting and trapping critical elements. Their influence thus spread to the fringing hills and lowlands where game and furs were plentiful. Coincidentally, the number of full time white trappers was gradually increasing. Some of these hunters and trappers, knowing the country well, began guiding Outside trophy hunters. Among them were rich clients who could spend weeks killing animals whose meat was only selectively used.

Depopulation, relocation, and competition from newcomers on the land had worked together to severely reduce the Indian presence in the central Denali region. Transportation innovations played a strong part in this transition. On the northside, the introduction of airplanes for transportation and hauling of mail and freight had by 1930 made obsolete the old trail systems, roadhouses, and supply services that for awhile gave the Indians a functional role in the new economy. Contributing to this demise, the park road, even before its completion, siphoned transportation through the park and away from the old trails.

The airplane also opened up the most remote regions with amazing rapidity. Prospectors, hunters, trappers, scientists, and others suddenly showed up at places where distance and terrain had once held the map blank, where logistics had blocked all but the most temporary traverse. There were no longer refugia where Native people could pursue their own ways in isolation. To the south and east the railroad transformed the Susitna-Nenana corridor into a string of transportation and supply centers catering to the mining camps and towns along the way. Indian life at places like Talkeetna, Cantwell, and Nenana was overwhelmed by wage-work opportunities and the flood of non-Native people and activities. Here the Natives' integration into the cheap labor phase of the transportation and mining economy was nearly complete. For many of these people, hunting, fishing, and trapping became adjuncts to wage work instead of the other way around as in more isolated places. [41]

As ties to traditional territories and activities attenuated, and as relocation to permanent villages accelerated, schools—both mission and government—exerted ever stronger influence on Indian life. St. Mark's Mission and School at Nenana, founded by the Episcopal Church in 1907, offered benign assistance to many Indian children, including health care, education, and spiritual instruction. Given the tragedies of mass death by disease and the orphanage of many Indian children, the mission is remembered by students of those days as an oasis of order in a disordered world. This memory was enhanced by the school's philosophy, which was shaped by Archdeacon Hudson Stuck's knowledge of bush life. He knew that Indian students must not be torn whole from traditional ways, that they must apprentice in the wilderness arts and skills employed by their elders. The schools under his jurisdiction were instructed to give the young people time on the land with their Native guardians to get that training. Otherwise, he maintained, they would become disfunctional in their own societies, unable to support their families in adulthood.

|

| Tanana Mission, at Tanana, 1934. J.B. Mertie, Jr. Collection, USGS. |