|

Denali

A History of the Denali - Mount McKinley, Region, Alaska Historic Resource Study of Denali National Park and Preserve |

|

Chapter 8:

CONSOLIDATION OF THE PREWAR PARK AND POSTWAR VISIONS OF ITS FUTURE

The 35 years between 1928 and 1963 traced a shift from meeting McKinley Park's functional necessities to defining the ideals that should shape its future.

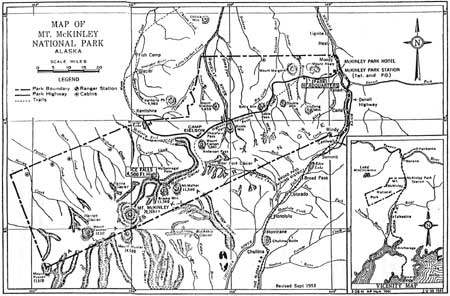

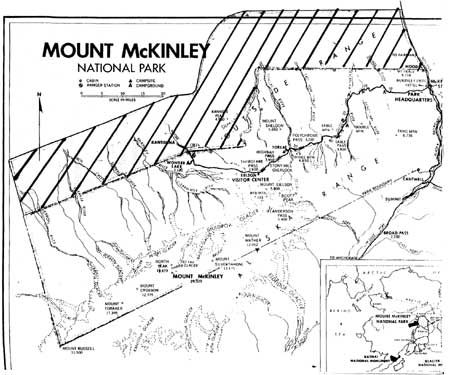

Harry Liek, Karstens' hand-picked successor as superintendent, devoted most of his energy to rounding out the early park's geography and completing its basic physical plant. During his tenure the park was enlarged to include Wonder Lake and buffer lands to the northwest, and the lands between the 149th Meridian and the Nenana River to the east. He oversaw completion of the park road, immediately followed by the ARC's construction of the short spur to Kantishna. The park hotel near McKinley Station was built and opened. Crews of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCCs) built the Wonder Lake Ranger Station—the park's operational anchor at the far end of the road—along with headquarters and other improvements.

Then came World War II. The park closed down its conventional operation and became an Army recreation center. The Park Service presence, severely cut in funds and manpower, was limited to critical maintenance and oversight of the Army occupation.

After the war—which gave Alaska a new transportation infrastructure—interest in Alaska development and tourism surged. National and territorial commissions and boards, expanding on Depression-era programs and studies, conceived Alaska as a giant reservoir of resources to expand the Nation's war-induced industrial might. The territory—visited during the war by a million soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen, plus unnumbered civilian workers on bases and roads—was now known throughout the land for its unparalleled recreational opportunities: hunting, fishing, and the wild beauty of the Last Frontier.

And this was a different nation from the depression-ridden one before the war: more populous, richer, more powerful, and victorious. Workers, not just the elite, had money and—after peacetime retooling of factories—the mobility of cars and paid vacations. After the deprivations of the past 15 years, they were ready to roll. So Alaska beckoned for industrial development, tourists, and pioneers.

The Park Service responded to these historical forces with development plans of its own, focused on Mount McKinley National Park. The Korean Conflict slowed these plans, but only for awhile.

The prospect of the park's direct connection with Alaska's expanding road system—now connected to the rest of the North American road network—both scared and inspired the park's stewards. That connection would break the pattern of limited and controlled access by rail. Here was a park whose facilities could host only a few thousand visitors a year (the highest prewar number had been 2,200 in 1939). What would happen when the lock of isolation was broken? On the one hand, unless the park's physical plant were expanded (the hotel had less than 100 rooms; campsites were extremely limited) the park would frustrate the expected deluge of visitors. On the other hand, that connection would make the park a democratic institution, a place accessible to working people from both Alaska and the States. Thus historical change brought both threat and opportunity to the Park Service in Alaska.

Responding to the drumbeat of development and tourism boomers—who were backed by high-level studies and proclamations urging Alaska's integration into the Nation's industrial and recreational systems—Park Service policy-makers and planners envisioned a conventional Stateside park with a lodge at Wonder Lake, more campgrounds, and an upgraded road to accommodate independent auto-borne visitors. The elite would continue to be served tour-and-hotel style; the average family could drive in and camp as at Yellowstone.

The park road—narrow and winding—had been adequate for the low levels of commercially conducted bus and touring-car traffic when visitors were fed into the park by the trains. But it would have to be widened and straightened to handle large numbers of private-car visitors whose eyes would wander in search of wildlife and scenery.

|

| Pulling a touring car out of Savage River. The tourist camp is in the background. Herbert Heller Collection, UAF. |

Thus, an improved park road would become the transitional link between old times and new tunes, between old park and new park.

This planning concept—given funding impetus by the Park Service's MISSION 66 program (a nation-wide catch-up in visitor facilities to be completed by the Service's 50th anniversary)—kicked off a lively debate about the park's future both in and out of the Service. Thoughtful people in or closely associated with the Service saw the park's purpose as a wildlife refuge endangered by such plans. Should these plans go forward, they feared the loss of the park's chief charm for visitors: its wild, uncrowded naturalness, its regal animals near and viewable from the low-speed, light-trafficked road because it was that kind of a road.

These arguments within were echoed and amplified by a growing conservation constituency without By 1960 Alaska conservation organizations had become sophisticated and single-minded about not repeating the land-ravage mistakes that marked the end of frontier Down Below. Mount McKinley National Park became the line in the sand in this struggle. If Alaska's wilderness could not be protected at McKinley Park where would it be safe? National organizations joined this fight, abetting the pressures on the Park Service to rethink its planning concept.

In the end, the road-improvement project and its major accessory developments were scuttled. The park ideal—the combination of wildlife and scenery envisioned by Charles Sheldon—was reaffirmed. The interior of this park would remain a wildlife sanctuary where people came truly as visitors—joining for awhile their mammalian cousins in wilderness adventure.

In this way the early Sixties marked a turning point in the park's fate. The organizations and the ideals perfected and affirmed at that time would continue to influence the Nation's sentiments about Alaska's enduring values. This force of ideas would revive and largely prevail during the struggle over the National Interest Lands a decade later.

Still superintendent of Yellowstone and assistant field director of the National Park Service in late 1928, Horace Albright recommended his trusted ranger associate Harry Liek as the man to replace Karstens at McKinley. In letters to Director Mather, Albright sketched Liek's dependability and his skill as leader and administrator. Here was a man who could work both sides of the boundary and get the park on a firm footing. [1]

Mather endorsed Liek and got Secretarial approval rapidly. Both Mather and Albright wanted quick action because Alaska's delegate to Congress was pushing local men, including parties to the disputes of the Karstens era. [2]

The park staff greeted Harry Liek's arrival with a sigh of relief. Internal and external strife had frayed the bonds of the park community and relations with neighbors. Toward the end of Karstens' administration, he and Chief Ranger Fritz Nyberg had become enemies. Salvage of Nyberg's usefulness was high on Liek's list of priorities.

In April 1929 Liek sent his first personal report to now Director Albright. He recounted his and Nyberg's trip into the park and their plans to improve existing patrol cabins and build three more along the northwest boundary, as Nyberg had long recommended. Liek relayed concerns about an earlier proposed park-hotel site at Copper Mountain, recommending instead, with Nyberg, a site on Clearwater Creek nearer the mountain. He welcomed the proposed visit of Chief Landscape Architect Tom Vint. Resolution of such planning problems should get the jump on the park road (which would reach Copper Mountain in 1934) or the road's progress would determine park development. Liek ended with an invitation to Albright to visit the park at the same time as Vint. Albright replied that he couldn't make it, but he agreed with the need for Vint's visit and said that he would assure it. [3]

During the winter of 1929-30, Nyberg—a tough Norwegian with his own Sourdough credentials—became critical of the new superintendent. He charged nepotism rampant (Liek's brother and nephew were working at the park), continued miserable conditions for patrol rangers, and misallocation of rangers' time: too much construction work on headquarters and patrol cabins instead of patrols to stop poachers. Continued minuscule appropriations had caught Liek in the bind reflected by Nyberg's inconsistency over the need for, and opposition to ranger construction of, patrol cabins and quarters.

In due course, after Albright had investigated these charges, Nyberg was considered disloyal and suspended, eventually leaving his position. Albright reaffirmed his support for Liek, urging him to get past this episode and carry on. [4]

By January 1931, Albright was frank in his disillusionment with Liek. Why was he spending so much time at headquarters, so little in the park. Could he not drop office detail and get on with the important work? Nyberg had resigned, but Albright regretted that a man so suited to the park had not been salvaged and retained. Albright struck to the heart of the matter with these words to Liek:

I had hoped that you would not only do your work in Mt. McKinley Park in a satisfactory way, in which way I am sure you are doing it, but I had hoped that as an old associate of mine in Yellowstone you would do really conspicuous work that would be enthusiastically talked about by people who come in contact with you. As it is, I hear nothing particularly adverse to you just as I find no particular interest in you or enthusiasm for you. Consequently, I have the impression that while you are minding your own business, doing a fair job of administration and protection, you are doing nothing outstanding and that you are really spending a good deal of time at headquarters instead of moving about the park studying its problems, particularly those of wild life, making plans for the future, gathering data regarding the natural features of the park, etc.

Finally, the Director called for a personal response from Liek explaining "how you think you are getting along," both in the park and in the territory, written in the same spirit "as you would if you were still Assistant Chief Ranger at Yellowstone and I was Superintendent there." He reiterated his continuing interest and affection, and his hope that Liek could do the really big things expected of him. [5]

In another letter two weeks later, Albright referred to Nyberg's charge that rangers spent too much time on construction, particularly around headquarters. The Director recognized Liek's funding bind as the reason for such use of manpower. Nevertheless, discounting emergencies, it was not NPS policy to put rangers on construction work:

You should arrange your work this coming season so that your rangers are used in patrols all the time and you yourself should make all the patrols you can. Mount McKinley National Park is not far enough along to need much in the way of headquarters and aside from the clerk I see no reason why anyone should spend much time at headquarters. I am expecting your men to be on the go right along. If they don't make patrols we will have to assume that their living conditions in the park, in the way of cabins, equipment, etc., were not adequate to support and protect rangers while on patrol and that this was due to the fact that the rangers had no opportunity to get their buildings and equipment in shape for the winter. [6]

Under the gun of Albright's two letters, Harry Liek hastened to reply in early February 1931. His letter covered Albrights criticisms point for point:

Construction of the headquarters complex was the main project when Liek arrived at the park and he could not leave the buildings unfinished.

Funding shortages forced him to draft rangers for construction during a good part of the summer so that the park would be prepared for winter, which would be an emergency without new quarters.

The superintendent, lacking a construction foreman, as was standard in other parks, could not leave project supervision to his clerk; and as disbursing agent for the park, Liek had to be at headquarters periodically to sign checks and vouchers.

Despite these anchors he had tried to make at least one patrol every month to monitor the park's condition, and in fact had been on patrol when Albright's letters arrived, thus the delay in answering them.

The rangers had been in the field since August 15 and had carried out cabin and equipment repairs to facilitate winter patrols.

Both Nyberg and the park clerk had asserted themselves as the old timers who should run the park and tell the new superintendent what to do. When the honeymoon was over, Liek saw that this was not just advice but rather an attempt to usurp his authority as superintendent. Upon refusing further dictates from his subordinates, they got sullen and conspired with others to cause him grief. In this pattern Liek saw a replay of Karstens' troubles.

Liek challenged uncritical evaluations of Nyberg's value to park and Service, asserting that his brusque manner made many enemies.

Liek agreed that he had done nothing conspicuous to put the park on the Alaskan map. He could make little headway with Alaska public opinion because "Alaska people do not visit the park like the people in the states do." He concluded this subject with the remark: "Right now it would be hard for a person to do anything conspicuous here unless it was to climb Mt. McKinley."

Finally, Liek welcomed the Director's trip to the park, planned for summer 1931. Then he could see first hand what the country and the park were like and would not have to take somebody else's word for it. Meanwhile, Harry Liek would keep trying his best "to make a really big job" out of his superintendency. [7]

These exchanges of correspondence between Albright and Liek graphically portrayed McKinley Park's "rob Peter to pay Paul" problems. They also confirmed or set in train a series of important events in the park's history: 1) Tom Vint's 1929 visit and planning concept for the park; 2) Director Albright's 1931 visit; and 3) Liek's answer to Alaskan anonymity, the 1932 double ascent of Mount McKinley.

Upon his accession to the directorship, Horace Albright opened communications with Territorial Governor George Parks. His purpose was to reassure the governor that the NPS took seriously its charge at McKinley Park, including its contribution to the territory's economic progress. Issues important to the governor had been outlined in an earlier letter to Director Mather, before illness forced him to resign.

In that letter the governor summarized his discussions in Juneau with Service landscape architect Tom Vint and McKinley superintendent Harry Liek, who had just conducted a planning reconnaissance in the park. They had agreed that the park could contribute little to the territory's economy until provision of adequate hotels at Seward, McKinley Station, within the park, and Fairbanks. The governor assumed that the park concessioner could finance a hotel or lodge within the park. But the other three hotels would require Outside money. Investors would have to believe in Alaska's future as a tourist Mecca, which depended largely on the park's role as magnet for the pilgrims.

This chicken-and-egg conundrum repeated the usual pattern at McKinley: one could not do the first thing until the second thing was already in place.

The governor also mentioned park-boundary proposals broached by Vint and Liek. He rejected their idea of an easterly extension to the Nenana River. He stated that the strip between the current boundary (at the 149th Meridian) and the river was too busy with the railroad, landholdings, hunting and trapping, and mineral potential. Any attempt to take over this strip, even as a buffering game refuge, would enflame Alaskans against the government and cause endless administrative annoyance. He insisted that the existing park was big enough, and that development within existing boundaries should be the focus of NPS efforts. [8]

Responding to the governor, Albright touched on the need for adequate ship service to Alaska and the potentialities of a proposed international road through Canada. He was pessimistic about assurances to hotel investors that the park could be rapidly developed. The Service got only marginal appropriations for stateside parks already crowded with visitors. Remote McKinley Park's uncertain future, especially given the extremely short summer season, would make both Congress and business leery of investment. Albright added that he planned a visit to the park and direct discussions with the governor before pursuing the boundary issue further. [9] A month later, Albright wrote to the governor about McKinley Park boundary discussions in the Secretary's Office, where agreement was reached that the boundary should be extended eastward only as far as the railroad right-of-way. But no action would be taken pending the promised discussions with the governor. [10]

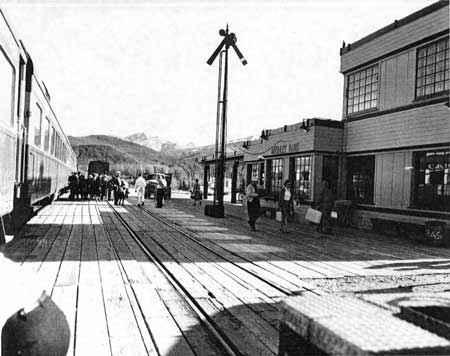

The park's economic contributions to the territory would continue to be adduced as a justification for its existence and further development. In an economic-benefits report in 1931, Harry Liek listed these benefits: tourist expenditures on the three main routes through Alaska and the Yukon; replenishment of wild game and furbearers from the protected park to surrounding areas; the park-road project as construction-materials purchaser and employer of about 200 men each year; and upon the road's completion, its expected stimulation of mining activity in the Kantishna district. [11] In 1935 the park attracted 665 railroad tourists who bought tickets and overnighted at the railroad hotel at Curry, 20 miles north of Talkeetna; they also bought lunch at the railroad's Healy lunch stop and made hotel and miscellaneous expenditures at Fairbanks, Nenana, Anchorage, and Seward—totalling an estimated $60,000 for the year. [12]

|

| Adventurous tourists sought out areas not reached by the road system. This pack train visited Polychrome Pass in the 1920s. AMHA. |

|

| A few rugged tourists took trips to McGonagall Pass or to the ice formations at Muldrow Glacier. This photo of an Muldrow Glacier ice bridge was taken in 1931. J.C. Reed Collection, USGS. |

Throughout the Thirties, because Katmai and Glacier Bay National Monuments (established in 1918 and 1925) were unmanned and rarely visited, there were no statistics from these areas. Sitka National Monument (1910), with only an intermittent custodian, attracted both local people and thousands of tourists from ships, but no expenditure figures were available. [13]

Landscape architect Tom Vint's 1929 reconnaissance at McKinley Park responded primarily to a substantive need: a professional overview to guide park planning and development. The trip also functioned as an earnest to the governor and other Alaskans that the Service wanted to develop the park for visitor use, which, as a side benefit, would bring dollars to Alaska. With a planning concept at hand the Service stood a better chance of getting funds from Congress. Moreover, lacking such a plan—designed around park principles—the park would fall prey to exploitative development schemes hatched elsewhere.

As previously demonstrated, even in the early days such schemes abounded. And they would continue to surface as the years rolled on. Funds incident to New Deal programs provided the means to do some work in the park, but by then the park's master plan—a direct result of Vint's and subsequent planning—helped screen and channel the projects. As World War II wound down—with victory certain—a whole new generation of Alaska development studies began to proliferate. In the main, through the immediate postwar period, such studies, plans, and petitions treated McKinley Park principally as an economic asset whose yet latent value to Territory and Nation would be measured by the degree of park development and the number of tourists thus attracted. [14]

A postwar letter from Alaska Governor Ernest Gruening to the Interior Department's Office of Territories expressed the frustration shared by many Alaskans over the lack of development in the territory's parks and monuments. The trigger for this letter was a notification from the department that "The National Park Service is taking an increasing interest in tourist development of the Territory of Alaska; they have several people in the field this year studying the area." Gruening exploded:

My own view is that we have been studied ad infinitum and that we know nearly everything there is to know about recreational facilities in Alaska, including and especially the fact that they continue year after year to be virtually non-existent. We also know that Park Service officials come year after year, survey, inspect, study, look us over, etc., etc. They are fine people, know their business, and we enjoy their company. But they are captains without a ship, officers in the Swiss navy. Their trips, while enjoyed by both us and them, result in nothing but pleasant memories for government officials—at public expense. What we need is some appropriations for facilities. If the money spent on these trips were accumulated we might in time have enough to build a small lodge in Glacier Bay National Monument, or we might be able to build one-half mile of road in Mt. McKinley Park from the long proposed, but non-existent, lodge at Wonder Lake to the Mountain. The trouble with these inspection trips, however, is that they emphasize and call attention to the continued lack of action in bringing about any park development. It is not surprising that a critical attitude had developed in Alaska at the great number of Federal officials who come to Alaska in the summer to "look the situation over."

..........

Hence, while we shall continue to welcome these various Park Service officials at any time, I desire to emphasize with the urgency based on eleven years frustration in getting any favorable results—a frustration which however is much longer than my terms in office, that what we need is action at budgetary and Congressional levels before anything else.

Let us have something besides the wonders of nature for these Park Service inspectors to inspect. Let us provide some man-made achievements in Alaska's parks and monuments for their study. Let us finally have something in Alaska for the public that pays the bills and is entitled to some return in the way of service. [15]

In reality, beginning with Vint's planning concept and on through the postwar period, the Service was more ally than opponent of the economic rationale for park development—but within certain bounds defined by "the park ideal." The thwarting of additional visitor facilities at McKinley came not from the Service, but from lack of appropriations that only Congress could provide. Mounting frustration bred of no apparent developmental progress in the parks, compounded by Alaska's largely government-inspired boomer psychology in the postwar period, led even enlightened commentators like Governor Gruening to vent outrage against the very principle of preserved lands. Other public land agencies—the Forest Service and the General Land Office (later the Bureau of Land Management)—provided not only recreational uplift but solid economic benefits through timber leases, mining, and land disposals for homesteads, fox farms, and manufacturing sites. In contrast, the Park Service studied but did nothing; meanwhile the huge chunks of Alaska land that it managed produced nothing.

This attitude and perception had deeper roots. Frontier notions—still very much alive in Alaska—that wilderness is the enemy, that the shaping of landscapes to human purpose and profit is the greatest good, offered little support to an institution whose park ideal spoke the opposite. The Service's middle-ground response to development clamor—some development but not too much—suffered public rebuff in the frustration produced by funding deficiencies that aborted even these modest proposals. And by the time the Service did get some appropriations, beginning about 1960, such modest developments were viewed as "too much" by wilderness preservationists, by then coalesced as a national constituency.

So much for context. What of the plans themselves? When Tom Vint came to the park in 1929, he already had a recommendation for a permanent hotel site deep within the park. Following a summer 1927 trip partly to scout such a site, Harry Karstens championed the Clearwater Creek area south of Wonder Lake at the very foot of the mountain. He proclaimed it"... the most suitable scenic spot and there are many, many wonderful side trips to be made both for hikers, mountain-climbers or on horseback . . . also the fishing is very good." [16]

Determining the site and type for a permanent hotel or lodge under the loom of the great mountain would continue to occupy park planners and commentators-at-large until 1970 when the idea was finally rejected. Tom Vint's immediate purpose was to provide definitive data for resolution of this issue, but first he must establish the park's place in Alaska:

The Territory of Alaska is a big, new and practically undeveloped country. Some of it is still unexplored. Over 95% of the land area belongs to the Government. The larger portion of this is administered under some bureau of the Department of the Interior. The Government's activities, taken as a whole, form the greatest single influence on the life and the development of the Territory.

The commercial interests are Fishing, Mining, Furs, Pulp and Lumbering. Alaska's possibilities as a recreation area are coming to be a very important element in its development. At present it is generally conceded that commercially, recreation facilities take third place in relative importance in the list named above. It may within a few years creep ahead to second and possibly first place. The ouffitting and conducting of big game hunting parties has developed into quite a business. The general tourist trip business is, of course, the largest recreational factor. McKinley Park, it is generally conceded, is the big note of any trip which includes the interior of the territory.

The Park then holds a dominating place in the life of the territory. It contains the most important scenic area. It happens to be located where the park trip becomes the climax of any Alaska trip on which the park is included. This is a strategic position in a country where recreation plays such an important part.

On the other hand, few people will make the park the purpose of their trip. It will be the big note of a trip to Alaska. Its development will influence and equally be influenced by the development of all travel facilities that are used in making the trip from Seattle or Vancouver to the interior of Alaska. In planning and scheduling the development of McKinley Park we are obliged more than [at] any other place to work in accord with the development of the surrounding territory. If we progress too rapidly in providing accommodations, they will remain idle. If we are too slow, tourists will be denied the park trip. This dependence of the various developments is far reaching, for instance, if the steamship companies put on additional boats, hotels at the park and other points must be built and if the hotels are not provided, the additional boats cannot be put on. We find ourselves in one park where we are pioneering in a pioneer country. Our other parks came after the surrounding state was developed. [17]

This exceedingly intelligent statement illuminated much of the park's history and many of its troubles. The park, as a determining factor in the contextual development of Alaska, has never to this day achieved synchrony with its surroundings. In the early years, funding deficiencies held it back; later, and up to the present, preservation and wildlife concerns joined with continuing funding deficiencies to inhibit park developments that would match surrounding paces and pressures.

As "the big note" for Interior Alaska travelers, Mount McKinley/Denali National Park has been placed throughout its history in the incongruous position of commercial pace setter for much of Alaska and its tour and transportation links with the outer world. But should park development respond willy-nilly to match this external pressure—now at explosive levels—the park's intrinsic values would be lost, particularly in the old park-refuge interior traversed by the park road. As we shall see, modern planning concepts, based on the park's enlargement on the south side, sought an alternative to flooding the park interior with traffic and development. But yet again, funding and decision deficiencies have foiled initiation of conventional park developments on the less vulnerable south side. So the single road through the park, anchored on ever more powerful commercial winches at either end, stretches ever tauter between them.

Pending southside-development relief, designed to channel commercial pressures away from the park interior, Denali National Park will continue to be out of step with its encroaching commercial environment, and vulnerable to destruction of its historic purpose.

After a careful tour of hotel-site potentials with the superintendent and concessioner Jim Galen, including a look at the Clearwater site—which was too distant and difficult of access—Vint chose the well drained plateau below the modern Eielson Visitor Center. Here was firm ground, expansive enough for a major development and easily reached from the route marked out for the park road. It offered excellent views of the mountain and its lesser companions, though Mount Mather was blocked by the near bulk of Copper Mountain.

Vint's general plan included a hotel at McKinley Station, the concessioner facility at Savage River (serving as base camp for east-end wilderness trips), and the Copper Mountain (Mount Eielson as of 1930) hotel deep within the park (with hiking and pack trips toward the mountain). This assemblage, based on the railroad and concessioner- provided access via the park road, offered the choice of short-term or long-term visits, and both sophisticated and rustic facilities to meet differing visitor demands.

Vint saw the inevitability of direct road access to the park, but correctly predicted that private-auto access lay far enough in the future that it need not complicate this first-stage development concept.

The ARC's pioneer construction techniques on the park road worried Vint. He wanted better engineering plans to avoid later rerouting, which would leave unsightly road scars. Neither eventuality came to pass. The road, essentially as built by the ARC (beyond Teklanika), is the road still used today. As noted above, Vint's recommendation to move headquarters back to McKinley Station was rejected by Director Albright.

With the completion of the proposed McKinley Station hotel, the railroad could abandon the Curry hotel as its passenger overnighting facility and rearrange train schedules to allow overnight visits to the park.

Air touring of the park, with its easily attained overviews of McKinley's vast landscapes and mountain architecture, appealed to Vint. He urged approval of a pending aviation permit and an adequate airfield. [18]

Wonder Lake still lay north of the park boundary when Vint was there, so he could not consider it as a hotel or lodge site. In 1929 the Copper Mountain area, with its views of McKinley and easy access to Muldrow Glacier and the range, formed the logical terminus of the park road. The boundary expansion of 1932 took in Wonder Lake, making the lake the logical terminus of the park road, and the preferred site for the interior-park hotel. The Copper Mountain/Mount Eielson site would become an intermediate viewpoint and concessioner camp, and, in later years, the site of an interpretive center.

Excepting that major variation, Vint's concept provided the park's planning frame for nearly 40 years. Lack of funds kept putting off construction of the Wonder Lake hotel/lodge, but it remained in the plans and was periodically revived as a hot project until about 1970.

|

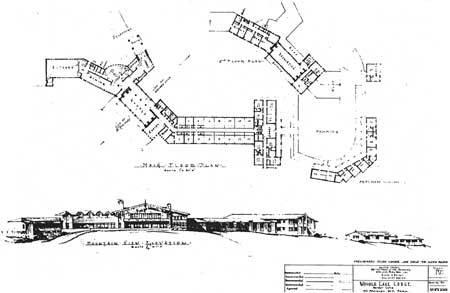

| Architectural rendering of the proposed Wonder Lake Lodge, 1935. NPS, Mount McKinley National Park Planning Concept, 1935, in DENA archives. |

With the postwar advent of private-auto access (quite modest until 1972), auto campgrounds would replace the concessioner camps of the railroad era. The outermost of these auto-era campgrounds was established at Wonder Lake, at the south-end site originally reserved for the hotel/lodge.

In terms of actual visitor access and use, Vint's scheme—hinged on the park road, and adjusted for the 1932 boundary change, the failure to build an in-park hotel, and the onset of direct highway access—determined the park's essential infrastructure that is still in place today. In fact, terrain and the railroad determined the park entrance; terrain and in-park objectives determined the route of the park road. Vint's and subsequent planning simply embellished these determinants. Significant private-car access to the park since 1972 has determined all further adjustments, physical and operational. Terrain, transportation, and funding or lack thereof for alternate visitor-use sites will continue to dictate the substance of plans no matter how nicely phrased their rationale. The politics of preservation versus development will determine the real results of such plans. The park ideal will continue hostage so long as an inadequate single-option infrastructure constricts the mounting pressures of commercialization.

Director Albright and his associates in Washington endorsed the substance of Vint's report, the Director calling it "the most useful report that has yet been submitted on this park." [19] After a year's delay Albright visited the park in summer 1931. His appendicitis attack aborted his horse trip to hotel sites, but he flew over all of them, going on to Wonder Lake, which captured his imagination. Seeing it confirmed his intention to expand the park not only on the east end but also to include Wonder Lake and the buffering lands on the northwest boundary. He wanted the park road to extend to the lake and considered it a prime site for a fishing camp for visitors, perhaps even for the hotel. He liked Vint's hotel-site choice but counseled moving slowly for two reasons: First, the concessioner had been hard hit by the Depression-caused dearth of visitors. Thus, Jim Galen, president of the Mt. McKinley Tourist and Transportation Company, lacked finances to build an in-park hotel. Giving him use of the proposed hotel site for a temporary camp would help revive his fortunes, at the same time providing an immediate visitor facility in the heart of the park. Second, because the park was still in the pioneer stage of development such a sequence (camp then hotel) was appropriate. The temporary camp could be easily dismantled and the experience gained from its operation could prove useful for hotel planning. [20]

|

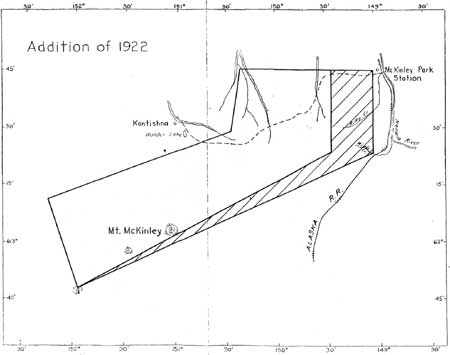

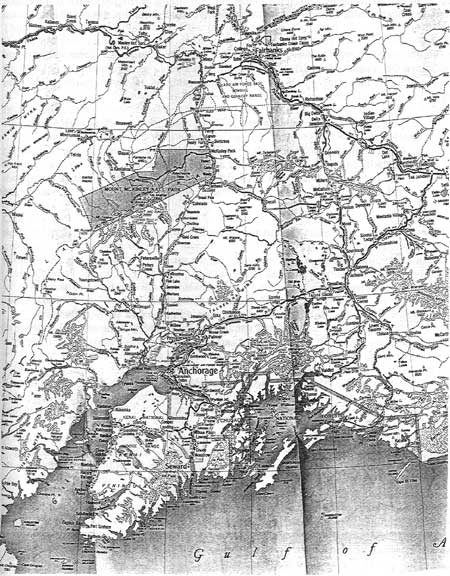

| Map showing 1922 park addition. Kauffmann, Mount McKinley National Park, Map 2. |

In another letter, Albright praised Vint's scenic "high line" routing of the park road between the Toklat forks, and the design by Vint's office of the East Fork bridge. Albright praised the park road:

Let me say also that I am very well pleased with the road that is being built in this park. It is frankly a pioneer highway for occasional use mainly by transportation buses. We will not live probably to see the time when many private automobiles will use this road. No other kind of a highway could have been justified in this park. I am not worried about curing the scar some decades hence. This country goes back to Nature about as fast as the Great Smokies. I flew over the park twice, and from the air the highway, except in the passes, is hardly traceable. So, as long as I am the Director of the Service, I shall hold to the present standards of highway building, except, of course, in the case of opportunities such as that you seized between the East Fork and main Toklat.

One more thing I am disposed to let the road be built on to Wonder Lake, provided, of course, we can get an addition to the Park to include the Lake. I want you to cover the country between your hotel site and Wonder Lake before the road gets too far over that way . . . . [21]

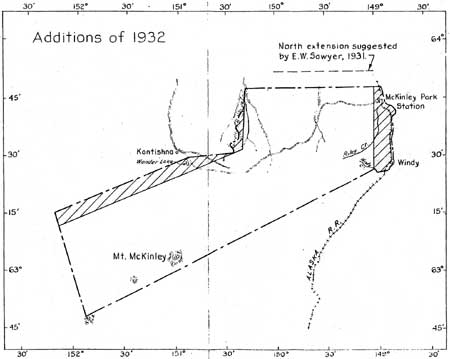

Both the 1922 and 1932 extensions of the park cited wildlife protection as their principal rationale. Secondarily, these extensions were proposed to protect key natural features (e.g., Wonder Lake in 1932) and to encompass lands critical to park administration, particularly on the east end.

In April 1921 Charles Sheldon had talked with Director Stephen T. Mather, Alaska Delegate to Congress Dan Sutherland, and representatives of the General Land Office, getting agreement from all of them that the original park boundary (running north-south near Sanctuary River) should be moved 10 miles east toward McKinley Station. [22] The 149th Meridian met this criterion and was chosen as the new north-south line at the park's east end. The headquarters relocation of 1925 would still be some two miles east and outside of the new boundary, but within the 1922 Executive Order withdrawal that protected the park entrance.

The Senate Committee report on the 1922 extension noted that the mountainous area east of the original park boundary, especially the headwaters of Riley and Windy creeks, were prime breeding grounds for Dall sheep and much frequented by caribou herds. [23] In an after-the-fact critique of the extension, Col. Frederick Mears, chairman of the AEC, wanted additional extensions to north, east, and southeast for still more protection of the game animals, which would be the primary attraction to tourists using the railroad. He warned that delay in moving the east boundary to Nenana River would cause the NPS untold grief by way of annoying and unsightly development in the park's forelands. [24]

As enacted, the January 30, 1922, extension took in the 10-mile strip east of Sanctuary River (but still west of Nenana River and the railroad), plus a narrow slice of land along the southeast boundary that captured the divide of the Alaska Range, giving that side of the park topographic definition. Even this extension was not without its opponents, who argued that further reservations around McKinley Park would deprive hunters and miners of choice land. [25] But the idea of capturing additional gamelands and the park's administrative forelands to the Nenana River, though delayed, would surface again.

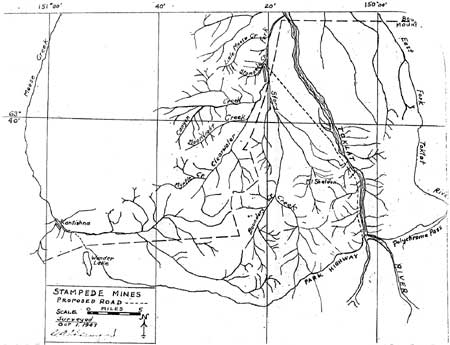

The 1932 extension began with a report from Tom Vint to the Director in early 1930, following up on his just-completed planning report. Vint deplored the unnatural boundary formed by the straight line 149th Meridian, pushing instead for extension of protected lands to the natural boundary of the Nenana River. (This proposal revived the idea earlier expressed by Colonel Mears as he was completing construction of the Alaska Railroad.)

Because Governor Parks opposed extension of the park as such, but would accept a game-refuge designation on the park's east end—in effect a protective withdrawal against hunting and random development—the game refuge formed the heart of Vint's proposal. The Park Service would administer the buffer zone to the Nenana, but would not call it a park. [26]

A year later, Director Albright put fresh steam behind the east-extension idea, calling for outright extension of the park to the river. With this support, Vint joined the chorus for direct action. The park extension to the river—excluding the railroad right-of-way—would provide an unambiguous natural boundary and facilitate patrol and game protection. He noted that Governor Parks and General Manager Otto Ohlson of the Alaska Railroad still opposed park extension. Ohlson wanted development along this section of railroad as a source of freight revenues for his trains; [27] thus he differed from his predecessor, Colonel Mears, who had seen protected parklands all the way to the Nenana as a lure for tourist traffic. This institutional shift may have reflected differences in temperament between the two men; it surely reflected the deficit-ridden railroad's growing disillusionment with tourist traffic as a significant source of revenue.

Then ensued a series of letters and negotiations between Director Albright and Governor Parks. By late 1931 the governor had shifted his position. Instead of urging the railroad as the park's eastern boundary, he now counseled Albright to go to the river to avoid "administrative problems that may be exceedingly difficult to control." He was talking about "undesirable citizens [who] have squatted on the lower reaches of Riley Creek and conducted bootlegging establishments to the detriment of the railroad employees and others." [28]

Albright, having become aware of these problems, had meanwhile reversed his position and was now loath to go beyond the railroad. There were enough problems even with the line of the railroad, including the Morino homestead, which would have to be bought out. Why acquire more?

At the other end of the park, the Governor had long favored the acquisition of Wonder Lake as a hotel site. He had further urged that lands in the lake's vicinity and along the northwest boundary be taken to capture game-rich but mineral-free hills and drainages. The Anderson homestead and fox farm at Wonder Lake's north end would also have to be acquired in time. Albright eventually acceded to the governor's views.

With the governor's support, Judge Wickersham introduced the bill extending the park eastward to the Nenana, northward to include Wonder Lake, and with adjustments northwest and westerly to acquire game ranges in the Kantishna Hills-McKinley River quadrant. [29]

|

| Map showing 1932 park addition. Kauffmann, Mount McKinley National Park, Map 4. |

In a memorandum to the Secretary, published in the Senate Committee report on the park-expansion legislation, Director Albright neatly summarized the advantages of these additions, which, when enacted and approved on March 19, 1932, would define the nearly 2-million acre park until 1980:

The east side extension from Windy Creek north brings the park boundary to the right of way of the Alaska Railroad. There are a few isolated tracts lying east of the Alaska Railroad right of way and the west bank of the Nenana River which should also be included in the park, as proposed by amendment No. 4, hereinafter recommended. This would make the west banks of the Nenana River for all practicable purposes a natural boundary line for the park. This extension will bring into the park the administrative headquarters development now constructed on lands withdrawn for this purpose. The National Park Service already maintains roads and trails within this area, and the main park road begins at the railroad station. A new hotel will sooner or later be erected near the railroad and this park road. This hotel should be on park land and built under park policies regarding architecture. Furthermore, better protection can be given the mountain sheep in this section, because the present line is now high up on the side of mountains and can not be observed by hunters to avoid trespass and for the same reason can not be physically patrolled by rangers.

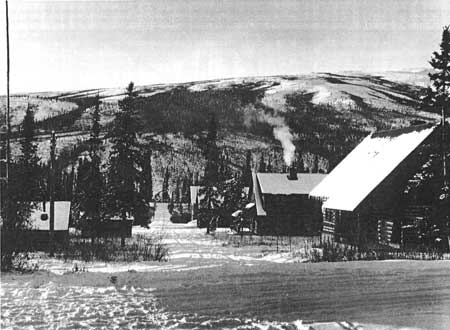

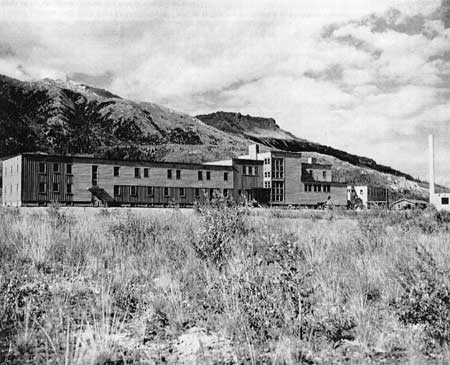

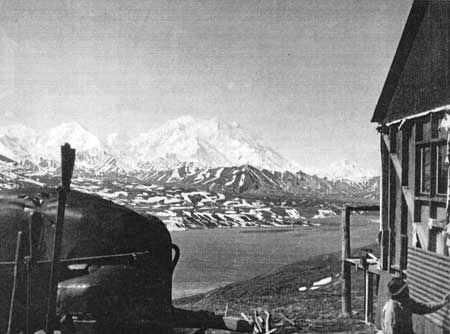

Park headquarters complex, ca. 1932. File 3-34, Denali National Park and Preserve historical archives. The proposed extension to the northwest will bring Wonder Lake into the park. The shores of this lake would provide an advantageous site for another hotel-lodge development and would afford a finer view of Mount McKinley than any now had in the park. The extension would permit us to continue to this scenic region the road now being constructed. In the most part this area consists of lowlands well adapted for game uses, especially during winter, and will form a better boundary line from a game-protection standpoint. It will also aid in better conserving the moose in the park by giving them winter range protection. An additional benefit from Alaska's standpoint would come from the opening of the Wonder Lake region under the park program. It would then be a comparatively simple matter for the territory to connect up with the Kantishna district making that region accessible. [30]

The administrative problems that came with the new lands made prior warnings about them seem woefully understated. Critical inholdings included: those surrounding McKinley Station (Maurice Morino, 120 acres; Dan Kennedy, 5 acres; and D.E. Stubbs, 35 acres); the 130-acre John Stevens claim at Windy, on the railroad at the park's southeast corner; and the 160-acre Paula Anderson homestead at the north end of Wonder Lake. In addition to these valid homesteads and trading-manufacturing sites were a score or more squatters' cabins tucked into the new park landscapes by wintering miners, hunters and trappers, and bootleggers. Exclusion of the squatters, though a painful and thankless task, occurred fairly rapidly. Most of these cabins—after salvage of the occupants' personal effects, if the men could be found—were burned or dismantled.

But owners with valid holdings made claims for damages incident to the boundary change: Dan Kennedy complained that his guiding business had been ruined; D.E. Stubbs asserted that park rangers loosed dogs near his fox pens, to the ruination of his fox-farm business. Some of these claims resulted in payment of damages by the government.

Because the private establishments bordering the railroad were derelict and unsightly—as well as being haunts of "undesirable citizens," as Governor Parks had phrased it—negotiations to purchase these properties were recommended by General Land Office investigators. Lack of funds delayed timely purchase by the government, even from the few willing sellers. As these deals dragged out, resentments fanned by Stubbs and others—plus episodes incident to NPS law enforcement, e.g., breaking up stills—embittered the entire process. Resultant condemnations to rid the park of noxious and hazardous establishments clinched the adversarial attitudes. Not until late 1947, with transfer of the deed to the long-contested Morino estate, were all privately owned lands within the park acquired—not counting unpatented mining claims, which did not involve land ownership. [31]

It had been 15 years of stress and strain for all involved. As the years went on, new judges and juries rendered condemnation judgments. Apparent inconsistencies of legal interpretation and land prices, plus overt political interventions, produced widely varying judgments: thousands of dollars awarded in one case, paltry hundreds in another. Indeed, there was pain and attrition on both sides of these land dealings as the voluminous records of the cases indicate. For the park people, these unpleasant and seemingly endless tasks were the price paid to cohere the park and assure its legally mandated protection. [32]

After the war—with Morino long dead and buried at the park (March 1937), [33] and the bitter days fading into the past—the pioneer roles of Maurice Morino and his roadhouse spurred then-Supt. Frank Been to consider the building's preservation as a historic site. Investigation of the collapsing remains by an NPS landscape architect in 1948 put a damper on this idea: they were dilapidated beyond repair and an eyesore at the very entrance to the park. The issue was resolved when Jessie L. Shelton, bumming through the park on May 30, 1950, took shelter in the roadhouse and, while reposed on a cot, dropped a cigarette on the littered floor. Perhaps in gratitude for his beneficent arson—and in practical recognition of his destitution—Jessie was not prosecuted. [34] Remains of the charred ruin were razed in 1951. [35]

It will be recalled that Harry Liek's debut as superintendent struck Horace Albright as a bit plodding. He wanted Liek to do something outstanding and conspicuous to get the park back in the good graces of Alaskans. Liek replied that in Alaska's climate of opinion he would have to climb Mount McKinley to make a mark.

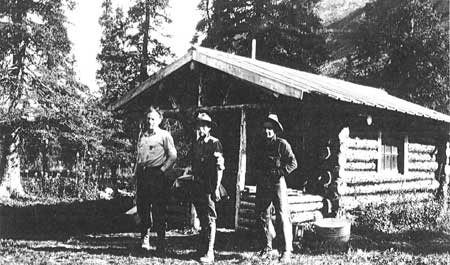

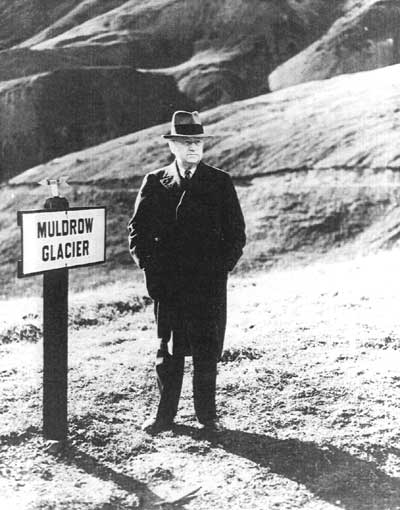

So that is what he did, in 1932, with Minneapolis attorney Alfred Lindley, Norwegian skier Erling Strom, and park ranger Grant Pearson. This last of the old-time mountaineering expeditions used dog teams to freight supplies to the 11,000-foot camp on Muldrow Glacier. These were the first men to ascend both peaks, climbing South Peak via Karstens Ridge and Harper Glacier, then traversing Denali Pass to North Peak.

|

| Grant Pearson (fourth from right) with a group of government officials and Kantishna prospectors, 1931. Pearson began as a ranger in 1926, and was active in park affairs for the next 30 years. J.C. Reed Collection, USGS. |

On their return to Muldrow Glacier they found the abandoned camp of the 1932 Cosmic Ray Party, led by Allen Carpe. A research engineer and mountaineer, Carpe had been commissioned by the University of Chicago to measure cosmic rays on Mount McKinley's high flanks. The Lindley-Liek group searched the camp vicinity and found the body of Theodore Koven, Carpe's assistant. Apparently he had died from exposure after being injured in a nearby crevasse, where signs pointed also to Carpe's fate: ski tracks, a broken snow bridge, and silent, blue depths. Study of this scene indicated that Koven, in trying to help Carpe, had injured himself. Koven's body was eventually retrieved from the mountain, but Carpe had to remain in his tomb of ice.

These were the first fatalities on Mount McKinley. The Cosmic Ray Party also inaugurated the technique of air transport and glacier landings by ski plane. Bush pilot Joe Crosson had set them down at the 5,700-foot level on Muldrow. This mode of access broke the logistical lock on Mount McKinley and became standard practice for later expeditions.

In 1934 the Charles Houston party made the first ascent of Mount Foraker, using pack horses for the overland approach. Bradford Washburn of Boston's Museum of Science began his long association with the mountain in 1936. Sponsored by the National Geographic Society and Pan American Airways, he made an aerial photographic exploration of the massif, taking 200 photographs that revealed the mountain 's most remote and intricate secrets. On this trip he discovered the Kahiltna Glacier-West Buttress route to South Peak, which he would pioneer 15 years later.

Washburn joined the U.S. Army Alaskan Test Expedition of 1942, led by Lt. Col. Frank Marchman. This 17-member party camped in the high basin of Harper Glacier for lengthy testing of cold-weather food, tents, and clothing. Seven members, including Washburn and Terris Moore, chronicler of the pioneer climbs, made the third ascent of South Peak.

In succeeding years, the pace of climbing and route pioneering accelerated. Glacier landings gave access to high base camps that would have been inaccessible by ground approach. The massif's secondary peaks and isolate features were climbed by parties seeking "firsts" in mountaineering annals.

Highlights include:

1947, first ascent of Mount McKinley (both peaks) by a woman, Barbara Washburn. On this expedition Brad Washburn performed survey observations from the peaks, and cosmic ray studies at Denali Pass.

1951, Washburn and Moore land on Kahiltna Glacier during mapping expedition, setting stage for Washburn's South Peak ascent via West Buttress a month later.

1954, Glacier Pilot Don Sheldon makes first commercial flight from Talkeetna to Kahiltna Glacier, thenceforth the standard approach for McKinley climbers.

1960, Brad Washburn's map of Mount McKinley published by Boston Museum of Science, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research. The result of 15 years of exploration, survey, and laboratory work, this masterful cartographic and artistic production remains the standard map for climbers.

1961, Italian Alpine Club party ascends South Peak via its sheer 6,000-foot ice-and-granite south face, called by Washburn at the time "the greatest achievement in American mountaineering history."

1963, a seven-man party led by Henry Abrons climbs North Peak via the 14,000-foot Wickersham Wall.

1967, Art Davidson, Raymond E. Genet, and David Johnston make first winter ascent of South Peak, via West Buttress.

1967, seven members of Muldrow Glacier-South Peak expedition die in storm during descent, the worst McKinley climbing disaster.

1970, first solo ascent of South Peak by Naomi Uemura of Japan (who would die in 1984, on descent, after first winter solo ascent of South Peak).

From the mid-Sixties on, climbing at McKinley began to proliferate and fall into broad categories: 1) standard guided climbs by parties following established, non-technical routes; 2) expedition parties seeking to pioneer ever more difficult routes, including climbs of highly technical features and lesser peaks; and 3) party and solo climbs and traverses that sought "firsts" in new combinations of mode (skis, dogs, hang-gliders, etc.), route, difficulty, and season.

All categories suffered increasing fatalities. More and more people climbed the standard routes, which were less demanding technically, but killed by storm, exposure, altitude sickness, and simple fatigue that led to accidents. As more experts stretched human capabilities to break point with technical feats and innovative combinations, more of them died, too.

All of these hazards came together in 1976—the Nation's Bicentennial—when 95 expeditions assaulted the massif. That year 33 climbers, out of 671 registered, suffered accidents—10 of them fatal. They required 21 separate rescue operations at great cost to the taxpayers. [36]

The NPS has been criticized both for imposing climbing regulations and experience—equipment screening, and for lack of screening and control over climbers. Improved procedures and facilities, spurred by the 1976 crisis, have saved many. These improvements include the ranger station-reception center at Talkeetna, with its specialized mountaineering rangers; medical camps on the mountain; and a network of public and private rescue groups who regularly accomplish prodigies of skill and courage—and sometimes die in their attempts to rescue others.

Modern mountaineering at McKinley has become a philosophical thicket: attitudes toward the mountain (conquest? caper? or spiritual quest?); freedom vs. restraint; life and death, for one's self and perhaps others; and the issue of park and wilderness ideals. Does freedom include freedom from rescue and from the Service's obligation to rescue? How far must people go to prove themselves against this enduring mountain? How bizarre their methods? And at what cost to the mountain's dignity, to rescuers, and to the taxpayer? Seeking the balances between mountaineering freedom and social responsibility, between intrinsic park values and transient human exploit will go on, probably indefinitely, but we must leave it here. [37]

Harry Liek's 1932 climb did help him gain public acceptance as "a real Alaskan." His association with Alaskan leaders on Depression-era commissions, boards, and recreation and economic surveys gave him access to public gatherings where he could push the park message and achieve first-name recognition in the territory's higher councils. [38]

Meanwhile, day-by-day work at the park moved along. Liek queried Washington about his jurisdiction over hunting in the railroad right-of-way, now included in the expanded park. The departmental solicitor's opinion held that it was the intent of Congress that the right-of-way ". . . should be subject to the provisions of law and regulations, applicable to lands within the National Park, not inconsistent with the operation and maintenance of the railroad." [39]

A 1935 report by the Interior Department's division of investigations indicated that Superintendent Liek had worked constructively with concessioner Jim Galen to provide adequate and comfortable visitor facilities at the Savage River camp, which now contained 100 "thoroughly clean and sanitary" tent houses, "10 x 12 feet, with board floors and sides and canvas roof. They contain two single iron beds, a small wood- burning stove, and table and chairs." Meals cost $5.50 a day, tents $3 per person, $4 for two. Round-trip transportation between station and camp cost $7.50.

|

| Savage River cabin and cache, 1946. Both were built in 1931; the cache is no longer standing. C.A. Hickock Collection, USGS. |

|

| Park rangers at Stony Creek cabin, 1931. Built in 1926, the cabin is now in ruins. J.C. Reed Collection, USGS. |

|

| Alaska Railroad Tour Limousine at Igloo Cabin, 1948. Alaska Railroad Collection, AMHA. |

Train service had been adjusted so that visitors could stay at least 24 hours in the park. Two package auto-touring trips, including lodging and meals, (24 hours at $25; 48 hours at $42.50) gave visitors access to Polychrome Pass or farther on to Eielson for close-up views of Mount McKinley. Guided horseback trips cost $15 per day. The flight-seeing trip from Savage River camp to the mountain cost $35.

Special Agent S.E. Guthrey gave high marks to park administration and to the propriety of the superintendent's dealings with the concessioner and with cinematographers employed for a promotional film by the Alaska Steamship Company. Questions on these matters had caused the investigation. [40]

In 1935 Liek proposed a number of physical improvements to be funded by the Public Works Administration, a New Deal agency that provided work for the jobless. In addition to employee quarters and housekeeping items, he wanted a radio telephone system for connections with outlying patrol cabins, a new administration building to replace the old one-room office, an interpretive museum at Eielson, and a ranger station at the Wonder Lake end of the road. He also wanted straight poles for the telephone line between headquarters and Eielson camp because the tripods supporting the line kept blowing down. These improvements were disapproved but would be revived under the CCC's program a few years later. [41]

By 1937, Washington officials, concerned that McKinley Park's purpose as a game preserve continued to be eroded by remote-area poaching, advocated aerial patrols. Living quarters for park personnel were still inadequate for the park's climate. And there were rumblings about a road connection to the park from Richardson Highway that would require significant changes at the park. [42]

That same year the American Consulate General in Calcutta, India, wrote to now Director, Arno B. Cammerer:

I was interested especially in one statement in . . . [your] press release in which it was pointed out that Mt. McKinley rises higher than any other mountain in the world above its own base. That this was so insofar as North American mountains are concerned, I already knew, but from the world standpoint this statement does not stand. I thought you would be interested to know that the famous Himalayan peak, Nanga Parbat, rises to an even greater height on its northern side than the total height of Mt. McKinley. Where the Indus washes the northern base of Nanga Parbat, the river has an elevation of just under 3,500 ft., and less than ten miles back from the river Nanga Parbat pushes its head into the blue to an elevation of 26,620 ft., thus at this point there is a sheer elevation of 23,120 ft., which so far as I am aware is the greatest sheer elevation attained by any mountain above its base. I have not yet had the good fortune to see this mighty spectacle, but I am still hoping that it will be possible before I leave India.

A cryptic and perhaps glum marginal note on this letter states: "verified by U.S.G.S." [43]

Matters of deeper substance also simmered during these years. The National Park Service had inherited a congeries of new areas under the Government Reorganization Act of 1933: many historical areas and a number of lesser reserves that, in the opinion of critics, did not match up to the pure parks created under the original National Parks impulse. The watchdog National Parks Association in 1936 tackled this problem with a paper on "The Place of Primeval Parks in the Reorganized National Park System." Robert Marshall and Robert Sterling Yard stated the gist of the association's thinking: The great primeval parks constitute a separate, superior class, which by title, mode of administration, and permitted uses must always stand distinct from parklands that bear the human signature. The association denied any deprecation of other park types in this segregation. They had their useful purposes, but they were different purposes.

Of the great parks the writers said: "The brilliance of these primeval areas results from their unaltered condition of descent from the beginning. There is no mistaking primeval quality." As modern civilization and exploitation cut across America's wild landscapes only remnants of the primitive remained—the few primeval parks (including Mount McKinley) and certain unexploited segments of National Forests. [44]

Of course this was an old idea, the notion that Nature untrammeled, unaltered by human purpose was yet of value to humans for the uplifting of the spirit inspired by untamed majesty and beauty. This concept treated not only of esthetics, but also of ethics and science. The Deists of the late 18th Century—a number of them founders of the nation—conceived Nature as a great watch assembled and set in motion by the Deity. It was only proper that some zones should run on Nature's time, that human beings should respect and care for the Creator's creation. In such zones scientists could study Nature's unmodified processes and the relationships between its parts. In this view ecology became a sort of intellectualized mysticism.

Thus was revived in the Thirties—a time of desperation, Dust Bowl, and reflections on the Nation's plundered patrimony—the distinction between Nature and natural resources, between superior value and economic benefit, between awe and board feet. This split in conservation philosophy played out a fascinating subset at McKinley Park—a struggle that helped to save it as a National Primeval Park.

As the result of a series of unusually hard winters at McKinley Park in the late Twenties and early Thirties, the Dall sheep population dropped precipitately. [45] Extremely deep snows and severe cold prevented the usual wind-clearing of snow cover from the high ridges where sheep found their winter forage. Many sheep died of starvation and those that survived faced the next hard winter in weakened condition. This condition, only partly recouped each summer, made the sheep easier prey for disease and wolves. Here was a classic combination for a population "crash," which came with a vengeance. Where there had been thousands of sheep, suddenly there were scattered hundreds.

The organizations that had helped found the park had focused their interest on the big game animals, particularly Dali sheep and caribou. The sheep, given Charles Sheldon's interest in them, symbolized the park for the game-protection groups that had worked so hard for its establishment. Responding to Alaskan reports that as many as 1,000 sheep and an equal number of caribou had been killed by wolves over the 1930-31 winter, William B. Greeley of the Camp Fire Club of America enquired of Director Albright in July 1931 how he planned to control predators and preserve the game animals. Greeley's letter ended with a pointed comment that the club's conservation committee ". . . does not in the least share the views of those sentimentalists who would rather let the mountain sheep be wiped out by depredators than to destroy any of the depredators." [46]

This letter and line of argument kicked off a jurisdictional and philosophical struggle that lasted 20 years. The main questions were: Did the Founding Father game-protection groups run this park, or did the NPS? Was specific game-species management—with its corollary of predator control—the proper management scheme for a National Park? Or were all native species protected under an ecosystem-management concept in which predators, by culling the weaker ungulates, kept those species vital and healthy over the long term?

Early on the Service defined its position as one of "preserving all forms of wildlife in their natural relationship." [47] Opponents of this position marshalled alarming figures on McKinley game-species deaths by predation, which could not be proved and were considered suspect by the NPS. The Service attributed declining wildlife populations to weather, migration patterns, and other natural dynamics, including predation as a contributing cause. Next the NPS was accused of bureaucratic foot-dragging in predator control; its theoretical and romantic approach toward predators produced carnage on the ground, leading to destruction of the park's choice game animals. [48] This position fitted well with prevailing game-management and bounty-hunter attitudes in Alaska. Thus, ironically, the Eastern game-protection elite, which had chastised Alaska's "wanton killers of game" during the earlier Alaska Game Law debates, now found itself aligned with the locals against the NPS. [49]

It must be understood that both sides to this controversy, bitter though it became, were moved by the highest motives. Moreover, the successive NPS directors drawn into this maelstrom had no interest whatsoever in alienating the game-protection groups whose efforts had led to McKinley Park's establishment. The differences between them were philosophical at base. These differences were fanned by other parties, for example by those Alaskans who wanted predator control both to increase huntable game and to keep bounty income flowing. But it was the difference in philosophy that counted. The depth and political volatility of the controversy forced the Service to refine its all- species-in-natural-relationship position through scientific studies. In aid of this work, the Service solicited help from some of the Nation's leading mammologists and ecologists. To avoid threatened imposition of statutory requirements for control of wolves, the Service compromised with a limited wolf-control program, a course legitimized by Adolph Murie in 1945. It is to the Service's evolving philosophical position, and the use of science to support it, that we now turn.

Responding to alarming figures for game animals, especially sheep, published by the game protection alliance, Supt. Harry Liek in 1935 made an aerial survey with Alaska game warden-pilot Sam White. They estimated 3,000 sheep in the park. Liek thought that this represented neither a decrease nor a significant increase from the past few years, but rather a restabilization of the sheep population at a lower level after the crash. [50]

In 1938 the Service announced publication of Joseph Dixon's Birds and Mammals of Mount McKinley National Park using that opportunity to further explain a natural regime in which variations of animal populations follow cycles dictated by habitat conditions and other dynamics. "Preservation of the native values of wilderness life," said author Dixon, is the ideal that differentiates NPS policy from those of sister agencies. The National Parks, as Director Cammerer had frequently stated, allow wild animals to behave like wild animals in their natural settings. [51] This let-Nature-take-its-course philosophy might register some disturbing perturbations, such as animal-population crashes. But this non-manipulative approach took the long view of natural rhythms and balances, and was the price of preserving the naturalness that gave ultimate meaning to wilderness parks.

In 1939 the Service sent Dr. Adolph Murie to the park to study predator-prey relationships. Exaggerated accounts of wolf numbers and their slaughter of wildlife would not die. The Service realized that it must develop a sound, science-based rationale for its hands-off (in reality, its light hands-on) wolf/sheep policy, or political pressure would force wolf extermination at the park. NPS biologist L.J. Palmer emphasized the importance of Murie's work both for McKinley Park and for other parks facing similar problems. Only accurate and complete data would validate Service policy and provide precedent across the country. [52]

The voluminous files of the wolf-sheep controversy furnish a fascinating case study of this ecologically motivated agency moving across fields of fire directed by the entrenched attitudes of an earlier age. The notion of favored animals derived from an older philosophy, manifested in game preserves and game-management practices of Europe's hunting nobility. Predators and particularly wolves symbolized the antithesis of Man's rationality imposed on chaotic Nature; to allow them free rein was to regress to pre-civilized times. For the advocates of wilderness and naturalness—called forth by the destructive impacts of industrialized civilization—opponents of the inclusive tenets of ecology were themselves regressive. Into this ideological maelstrom marched Doctor Murie who, respected on all sides, would do his best to reconcile these differences in thought.

Murie's conclusions, after field research in 1939-41, acknowledged that the sheep population was down and had not recovered from the hard winters of the 1927-32 period. But the current relationship between sheep and wolves seemed to have reached equilibrium. In fact, the limited predation by wolves probably had a salutary effect on the sheep, as a population, by eliminating weak and sick animals from the stock. [53]

As a result of Murie's analysis the Service decided to terminate a limited wolf-control program that had been in effect since 1929. [54] This change of policy created a virulent backlash. A petition to the President and the Congress from the Alaska Legislature, backed by nearly all public and private organizations in the territory, called for extermination of wolves in McKinley Park and other NPS areas which, said the petition, served as sanctuaries for breeding wolves that migrated and spread havoc across the land. [55] NPS Director Newton B. Drury, though a strong supporter of his biologists' ecosystem approach, read the signs of the petition and coincident drumming for a wolf control law by stateside game protectionists as omens too strong to ignore. In an ironic note to his chief biologist, Victor H. Cahalane, he asked, "Hadn't something better be thrown to the wolves?" [56]

This message coincided and comported with the results of Murie's second survey, which rang alarm bells. In 1945 Murie counted only 500 sheep in the park. This was getting close to a critical population that might not be able to sustain any further shocks—including wolf depredations—without danger of extinction from the park. [57]

Interior Secretary Harold L. Ickes joined Drury in advocating resumption of limited wolf control with his endorsement of a program that called for destruction of 15 wolves in the park. This control program would be conducted under direction of Adolph Murie, who would become the park's resident biologist. [58]

The rules of the wolf-sheep controversy changed qualitatively with introduction of H.R. 5004 in December 1945. This bill would require the Service to rigidly control wolves and other predators in McKinley Park in favor of game animals. [59] As a precedent with System-wide implications, this proposed legislation posed great danger. It would sabotage the Service's painfully established policy of preserving all native flora and fauna as necessary elements of the ecosystem. This challenge forced the Service beyond compromise and delaying tactics, for the very foundation of its wildlife philosophy now came under fire.

Director Drury and his associates worked with key friends of the Service to mobilize opposition. In May 1946 esteemed scientist Aldo Leopold of the University of Wisconsin joined the fight against the bill, volunteering his willingness "to do anything I can within reason to help kill it." [60] Ira N. Gabrielson of the Wildlife Restoration Institute responded positively to Drury's plea for assistance. Kenneth A. Reid of the Izaak Walton League of America urged Congress to reject the legislation on the basis that executive agencies could not respond to changing wildlife conditions if their discretionary powers were abrogated by gross statutory control over Nature's "minute mechanics." The Boone & Crockett Club, though ambivalent on the issue, refused to endorse the bill. William Sheldon, the principal Founder's son, argued not only the biological case but also the ethical and aesthetic ones for keeping wolves in Nature's sanctuaries. For him the park's 500 sheep with wolves was better than more sheep without wolves, for "the wolf is the essence of what we refer to when we speak of 'wild' animals." He concluded with the formula: Necessary control, yes, in the present critical situation; but extirpation, no. With this support at hand, in April 1947, Interior Secretary Julius A. Krug recommended against the bill, pledging such administrative control of wolves as necessary to preserve McKinley's sheep and other ungulates. [61]

Though the wolf-sheep controversy and limited wolf control continued for a few more years, the legislative threat was dead. The Service had threaded its way through both biological and political thickets. By 1952, with noticeable recovery of the sheep and a reduced wolf population, the control program was ended, having destroyed some 70 wolves since 1929.

Among a series of reports from distinguished biologists, solicited by the Service at the height of the controversy, was one by Dr. Harold E. Anthony, Chairman and Curator of the American Museum of Natural History. He advocated the Murie concept of wolf control—for both biological and political reasons—for the term necessary to assure sheep recovery. He made the distinction between beneficial, manipulative control to rectify an extreme natural situation, and the atavistic drive to exterminate wolves as a malignant species—the view that had clouded the wolf-control debates. In the letter forwarding his report to Director Drury, Doctor Anthony neatly summed up the Service's stresses and compromises, and the formula finally adopted for surviving this crisis:

I know [Victor] Cahalane has been holding out valiantly for the principle involved in this problem. He believes the wolf has just as much right in the Park as the sheep. I agree with him on that if this can be kept as a matter of theory. Unfortunately, the situation in the Park, for more reasons than one, has passed to the stage where the average man will not accept it on a theoretical basis. Furthermore, I consider that when one really believes in a principle he should maintain it and not make concessions to expediency. But if a conservationist is trying to get the best possible break on any particular issue, he may reach the point where it is necessary to decide whether he will take a stand that calls for all or nothing. Personally, I fear for the future of the wolf in the Park unless some concession in the way of active control is made now. And I really believe that the welfare of the sheep at this time requires it. [62]

A byproduct of Adolph Murie's assignment to the park during the wolf-sheep controversy was publication of his reports and observations in The Wolves of Mount McKinley (1944). Its portraits of the wolf and associated predator and prey species comprise a brilliant tapestry whose interwoven threads lead painlessly to ecological understanding. In his footsteps the distinguished wolf authority, Dr. L. David Mech, today continues studies of Denali's wolves and the ecosystem that sustains them. It seems that all students of this singular animal—so highly social, so symbolic, so powerful and cunning—fall under the spell of its primeval cry, the very essence of that which is wild.

Wrapping up the first-stage development of the park occupied the last few years before World War II. Critical to McKinley Park's function as a partner in Alaska's economic development—via attraction of tourists to the territory—was construction of a first-class hotel at the McKinley Station entrance. Alaska Governor Ernest Gruening and Interior Secretary Harold Ickes worked together to get funding for the hotel through the Works Progress Administration, with $350,000 appropriated in 1937. [63]

Two principles framed Secretary Ickes' approach to this project: As a staunch New Dealer he believed that visitor facilities in the National Parks should be government-owned and -operated to avoid any deviation from the public purposes of such accommodations. On a broader scale, he felt that Alaska had flirted long enough with the gambling psychology of mining. If the territory were to advance to statehood, thus avoiding the fate of a vast, abandoned mining camp, it must ". . . build up a civilization based upon a more stable and widely prevailing economy." Because of its many charms and splendors Alaska should look to tourism as the long-term base for permanent development. [64]

As affirmed by an NPS-conducted Alaska recreation survey of 1937, the plans for McKinley Park visitor accommodations called for a hotel at McKinley Station and a lodge at Wonder Lake. Planning Chief Tom Vint's office drew up preliminary plans for the rustic-design buildings. Money problems cut out the lodge and forced a revised, spartan design for the hotel. [65]

Following Secretary Ickes' principle of public ownership and operation, the Alaska Railroad was directed to use the WPA funds for construction of the hotel, and was charged with its operation once built. The NPS acted as the railroad's agent for design and construction. [66]