|

Denali

A History of the Denali - Mount McKinley, Region, Alaska Historic Resource Study of Denali National Park and Preserve |

|

Epilogue:

MCKINLEY BECOMES DENALI WITH DUBIOUS FUTURE

The park-road controversy had been the sharpest spur forcing reaffirmation of the McKinley Park ideal. But it had not operated alone. Threats of mining and related industrial incursions—e.g., building-stone prospects on Riley Creek near the railroad bridge, and limestone claims on upper Windy Creek near Cantwell, which augured a cement plant within the park—had aroused the Service's protective instincts. [1] The possibility of commercial development in the Kantishna area, where several business-site applications had been filed with the Bureau of Land Management, [2] increased the sense of a closing industrial-commercial environment crowding upon this park so recently secluded in wilderness. The mining developments would impair the park itself; all commercialization would bring more people to park boundaries with attendant environmental and hunting pressures, which, among other things, would interdict the migration routes of park wildlife moving to and from their trans-park ranges.

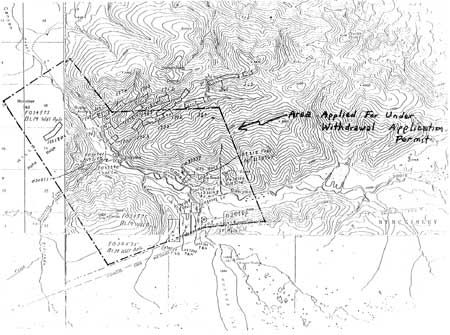

The first line of defense was to tighten the park's mining regulations to control surface uses. [3] Next came administrative withdrawals near McKinley Station and along the park road to protect against new mining entries in those areas most important for visitor use. [4] One protective withdrawal covered the limestone-cement plant area. But the Service suffered severe political damage on this score, both in Alaska and in the Department, where sister agencies—the Bureau of Mines and the Alaska Railroad—fought the withdrawal. The Service considered deleting this area from the park should the cement venture prove economically feasible, which, fortunately for park integrity, it did not. [5] In 1965 the Service worked with the Bureau of Land Management to get a protective withdrawal of 9,000 acres in the Kantishna vicinity. Though this withdrawal was not formalized because of another political storm, it still stopped new mining entries in this area, to which BLM assigned high recreation potential and the likelihood of inclusion in the park in the future. [6]

The NPS recognized that these remedies were partial and ameliorative. They were spot solutions in a changing world that demanded systematic and comprehensive solutions. Shortly, these concerns over borderland developments united with long-desired park-expansion proposals to chart a new course for park protection.

As early as 1931 the prescient Tom Vint had seen the need for a southern expansion of the park to encompass the spectacular glaciers and gorges that fronted the high mountains, only the peaks of which lay within the park. People on the trains had the impression of passing by the park, then losing sight of it—an ephemeral vision that could not be grasped. Yet, on the southside, excellent views and diverse forelands-recreation opportunities abounded. He concluded, nearly 60 years ago, with words that form the thrust of the park's modern planning: "If such an extension is found advisable McKinley Park would ultimately have two systems of tourist facilities, one north of the range the other south." [7]

|

| Area of 9,000 acre Kantishna mining withdrawl, 1965. File FBX 034575, BLM, Fairbanks District Office. |

Similarly, informed observers early noted the inadequacies of the boundary in the Wonder Lake area. Caribou and other animals drifted northerly from the park as the seasons dictated. The lowlands stretching toward Lake Minchumina and Kantishna River, and the hills and mountains curving north and east from Wonder Lake formed the other half of the wildlife ecosystem. The expansion of 1932 had caught only the fringe of this extended range. [8]

Because of concerted opposition to any further expansion of the park, these ideas lay dormant until after the war. But the wildlife studies of Adolph Murie and other biologists in the Forties kept the complete-ecosystem concept alive as an aspiration.

In 1963, consulting naturalist Sigurd Olson and NPS planner Ted Swem visited the park during an Alaska parklands survey requested by the Interior Secretary and the NPS Director. This was one of a series of agency studies stemming from George Collins' recommendations in the 1950-54 Alaska Recreation Survey. By the late Sixties these studies, in aggregate, would mark out a comprehensive park and conservation system for Alaska, the blueprint for the landmark National Interest Lands legislation of 1980. [9]

Sig Olson's report on McKinley Park stated that it was an elongated rectangle ". . . whose boundaries cut across normal game habitats irrespective of migration routes or breeding requirements." Both in winter and during spring birthing the animals strayed beyond the boundaries and had no protection. Ecologically, the park was simply too small. The Kantishna area brought the problem into focus. There, mining activities scarred the landscape; alienation of 5-acre tracts by BLM boded developments inimical to the park and its wildlife. These problems brought into the open ". . . the constant threat to the land near the borders of the park and the need of zoning, extensions, or cooperative programs with other agencies." [10] Olson's report was instrumental in the NPS-BLM negotiations that led to the Kantishna protective withdrawal in 1965.

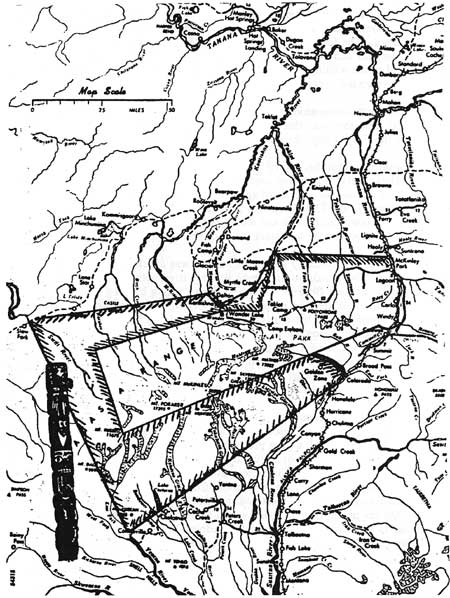

Not only biologists and bureaucrats concerned themselves with McKinley Park. In September 1965 the Fairbanks Igloo No. 4 of the Pioneers of Alaska wrote to Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall urging protective expansion of the park before the new wave of commercial development engulfed it. This branch of the Pioneers, an association of old-time Alaskans, unanimously recommended a near doubling of the park's area by means of a "U"-shaped addition from the Kantishna Hills along the northwest boundary, around the west end, and back up the south boundary nearly to Cantwell. On the north, this extension would protect wildlife wintering range (in a wide band similar to the coincidental proposal by Adolph Murie); on the west end, prime sheep habitat; on the south, the glaciers and gorges. [11]

At the same time the founders of Camp Denali, Celia Hunter and Ginny Hill Wood, proposed a modest buffer to protect Wonder Lake's biological and viewshed values. The two adventurous women had migrated to Alaska after the war (during which they were aircraft ferry pilots for the Army Air Force). With Ginny's husband, Woody, they staked land in 1951 on the ridge overlooking Moose Creek Canyon and Wonder Lake, just north of the park boundary. Here they established a wilderness camp that yet today offers quality experiences to that limited clientele that forms "the adventurous fringe" of the traveling public. Their determination to forego tinsel comforts and immerse their visitors in the Alaskan wild is captured in a paragraph from their promotional literature:

With wilderness fast disappearing in the "first 48" states, Alaska.. .offers the last large, unspoiled outdoor laboratory for the study and appreciation of undisturbed nature. Here you may still have the experience of the frontiersmen and explorers who first gazed on unbroken prairies, unharnessed rivers and undiminished wildlife."

|

| Pioneers of Alaska (Igloo No. 4) Boundary Proposal, 1965. File L1417 (Boundary Adjustments, MOMC, 1965-66), ARO. |

Wilderness advocate Roderick Nash, in his history of Alaska tourism, credits them with establishing and popularizing "wilderness touring" as a new category of recreational adventuring, made possible by "the remarkable expansion of interest in wilderness" in the decades following the war. [12]

In their critique of the Kantishna withdrawal and the ambitious expansion proposals of 1965, Celia Hunter and Ginny Wood warned of political backlash from mining interests. Moreover, they wanted Camp Denali to remain outside the park, for they feared regulatory interference with their operation. A small buffer zone defined by the line of Moose and Willow creeks would protect the physiographic setting of Wonder Lake. It would also leave out the disturbed mining landscape of the Kantishna district, which they deemed unqualified for parkland. [13]

Over the next few years—with benefit of formal boundary studies and endorsements by the Secretary's Advisory Board on National Parks—the more generous boundary proposals gained official status. In terms of rationale they boiled down to inclusion of the outstanding southside physiography and forelands-recreation potential, and the extended northside wildlife range that would complete the park's ecosystem. [14]

By this time George B. Hartzog had become Director of the National Park Service. Sensing the quickening pace of development in Alaska—given impetus by signs of major oil discoveries soon to come—Hartzog wanted action. Alaska was the last place where giant accessions to the Nation's parklands could occur. With strong backing from Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall, himself spurred by President Lyndon B. Johnson's espousal of the "new conservation," the energetic Director looked to a systems solution in Alaska. Individual park and site studies began to coalesce into an Alaska-wide plan of action. Coordination of this effort became the task of now Assistant Director Ted Swem. Hartzog then appointed a special Alaska task force, directed by George Collins, to define an "entire park complex" that would meet the long-term park and recreation needs of the American people on their last frontier. [15]

The expansion of McKinley Park now became part of what was shaping into a larger movement—pushed by the Service, other conservation agencies, and the forming Alaska Coalition, which over the next decade would focus private conservation groups on the Alaska issue. In what proved to be a premature expression of that movement, Hartzog and Udall in January 1969 presented to President Johnson seven National Monument proclamations, which, upon his signature, would constitute the outgoing president's "parting gift to future generations." Among them was a 2.2-million-acre addition to McKinley Park. Johnson rejected this and a 4-million-acre Gates of the Arctic (in Alaska's Brooks Range) proclamation because, in his view, Secretary Udall had failed to properly prepare Congress for such large-acreage executive sections. [16]

Meanwhile, historic changes were coming to a head in Alaska. The Statehood Act of 1958 had granted Alaska the right to select 104 million acres of the state's 375-million-acre total to be used as its economic and natural-resource base. The state's initial selections aroused the ire of Alaska Natives, whose traditional lands were threatened by wholesale alienation. Political mobilization by the Natives—Indians, Eskimos, Aleuts—resulted in a land freeze first imposed in 1966 by Interior Secretary Udall, pending resolution of the Native land-claims issue by Congress. The freeze stopped dead the parcelling out of Alaska's land. Thus was halted the great shift from an unbounded and almost totally public domain owned by the Federal Government to a diversified land tenure system—from open range to "fenced" range.

Coincidentally, the hints of giant oil discoveries became reality in extreme northern Alaska, at Prudhoe Bay. Transfer of the oil from the ice-bound Arctic to an ice-free port in southern Alaska required a pipeline, and the pipeline required an 800-mile-long right-of-way. The land freeze frustrated acquisition of this right, and temporarily put on hold Alaska's greatest bonanza.

The resultant remorseless and building pressures gave birth to a second system and a third system for divvying up Alaska's land base. Under the terms of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971, Alaska Natives would select 44 million acres of traditional and resource lands for their cultural and economic stake in Alaska. Under pressure from conservation agencies and organizations, Congress included a provision in the act, Section 17(d)(2)—"d-2" in popular parlance—that mandated recommendations from the conservation agencies to Congress for the setting aside of National Interest Lands Conservation Units: parks, wildlife refuges, wild and scenic rivers, and forests. The Settlement Act lifted the land freeze. State, Native, and National Interest selections soon blanketed the map of Alaska with a kaleidoscopic array of multicolored, 36-square-mile townships. Each of these 16,000-plus townships got its color code at the price of political, economic, and ideological struggle. In particular, the d-2 townships, including 11 park proposals—one of them being the additions to McKinley Park—caused storms of development-vs.-preservation conflict. It took nine years of intense scrutiny, strife, horse-trading, and political maneuvering for the Nation to sift out its vision for Alaska. This was only proper, the price of constitutional government, the way we as a people compromise our conflicts.

In the end, after the episode of the blanket National Monument proclamations of 1978—a holding-action to spur Congress to fulfill its own mandate—the legislators passed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980. [17] ANILCA, as the law is acronymed, set aside 106 million acres of conservation units, nearly 44 million of them in new and expanded national parklands. Close to 4 million acres were added to McKinley Park, tripling its size. The new complex of park and preserve lands was designated Denali National Park and Preserve. Old McKinley Park forms the wilderness-wildlife core of the complex. The 2.4-million-acre National Park additions extend north, northwest, and south; two National Preserves—lands on which sport hunting is allowed—rim the National Park to the northwest, west, and southwest.

These additions—the joint product of NPS and Alaska Coalition efforts, and confirmed by Congress—incorporated and expanded upon the Murie-Pioneers of Alaska recommendations of 1965. They capture the northern wildlife range so important to Ade Murie and the other biologists who have studied the park; the south flank and recreation forelands of the range; and the spectacular Cathedral Spires and neighboring mountainous areas to the southwest.

Included in the lands immediately north of Wonder Lake is the Kantishna district, where nearly 1,000 acres of patented private lands give prospect of major resort development. This old but new-in-scale prospect is part of an evolution stemming from the effects of the Mining in the Parks Act of 1976 and a recent conservationist lawsuit that forces tighter environmental controls over mining. For marginal operators, these stricter regulations make mining unattractive. But resort investors will bid high on privately owned acreage that is retired from mining.

How ironic it would be if major in-park facilities—long proposed and only recently firmly rejected by the NPS—were developed at Kantishna. Then the stresses on the "narrow and winding" park road, plus constant air access, would break the lock on the wilderness, despite the vast, buffering additions of 1980.

Solution of the Kantishna problem—which builds toward irresistible pressures for unrestricted access upon and inevitable "improvement" of the park road—paired with provision of a politically palatable southside alternative to the current single-option, interior-park visitor use, are the prerequisites of the park's salvation. Lacking these critical and costly moves the park road will become a stake in the park's heart.

Then the vision of Charles Sheldon, even now faded from his original ideal, will vanish entirely. And the park's potentially great role as an International Biosphere Reserve will be aborted. And the visitors who come to see the bears and caribou and wolves and moose and sheep will see them no more.

In the midst of all these complications, threats, and imperatives, the question posed 30 years ago by Adolph Murie still remains unanswered: Will this park survive as symbol and standard of our civilization's higher aspirations, or will it be sacrificed to the lowest common denominator? The absolute relevance of this question today testifies to the enduring themes of the park's history, and its meaning to a society still trying to find its way.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

dena/hrs/epilogue.htm

Last Updated: 04-Jan-2004