|

El Malpais

In the Land of Frozen Fires: A History of Occupation in El Malpais Country |

|

Chapter V:

A GARRISON IN THE MALPAIS: THE FORT WINGATE STORY

One of the first items on Col. Edwin V. Sumner's agenda when he reached Santa Fe in July 1851, was to superintend to Indian affairs within his jurisdiction. As commander of the Ninth Military District, Sumner assumed control of a vast territory comprising present-day Arizona and New Mexico and portions of Utah and Texas. Sumner quickly established military posts to protect frontier settlements. Fort Defiance, situated north of present-day Gallup at Cañon Bonito, was authorized in 1851 by Col. Sumner. Fort Defiance, Sumner hoped would act as a deterrent against Navajo forays on the Rio Grande or pueblo settlements. [1]

In actuality, the erection of Fort Defiance failed to awe the Indians into submission. Its presence was more a symbolic deterrent than actual. Navajos persisted in raiding settlements up and down the Rio Grande corridor. Col. Sumner retaliated in 1851 with a summer campaign. The elusive Navajos managed to avoid clashes with Sumner's superior force and the army returned to Santa Fe with negligible results. In 1852, the military conferred with some of the Navajos at Jemez Springs. The gist of the talks swirled around the American's request for the cessation of Navajo strikes. The conference failed because the Navajos simply refused to attend as promised. On May 27, a dejected Sumner penned a note to Secretary of War, C. M. Conrad, stating it would be in the government's best interest to return New Mexico to the Indians and Mexicans. [2]

American efforts to induce the Navajo to sign a peace treaty persisted. Finally, in 1855, the American government assembled a significant number of Navajos at Laguna Negra, located about 14 miles from Fort Defiance. Several Navajos were prominent in the peace negotiations who acquired "chief" status from the government. Zarcillos Largos, Manuelito, Barboncito, and Ganada Mucho represented the Navajos. Governor David Merriwether, Brig. Gen. John Garland, the military district commander, and Navajo agent, Henry L. Dodge, presented the U.S. Government position. An uneasy truce prevailed until 1858. Then the fragile treaty caved in, precipitated by a series of cultural misunderstandings.

At the root of the problem stood grazing privileges. Manuelito complained to officials at Fort Defiance that the Navajo would no longer permit the soldiers to pasture their livestock on lands ensconcing the post. The treaty of 1855 stipulated the government could graze its animals on adjacent Indian land outside the garrison. Manuelito argued the Indians needed the grasses for their livestock, pointing out that the military possessed many wagons in which to haul provisions. Serving eviction notice on the soldiers, the Navajos proceeded to pasture their sheep and cattle closer to the fort. Major William T. H. Brooks, commanding at Fort Defiance, ordered soldiers to chase away the livestock. When the Indians resisted, a skirmish erupted with the big loser, the Navajo cattle. The Navajos demanded payment for the cattle, which the Army rejected. [3]

In August troops from Fort Defiance launched another expedition against the Indians. The latest confrontation between the races had been touched off by the circumstances involving the death of Major Brook's black servant who had died at the post in a scuffle with a Navajo. The Navajos justified the act claiming the servant had molested a Navajo woman, an act punishable by death according to Navajo code of ethics. When the Navajos refused to hand over the offender, Col. Thomas "Little Lord" Fauntleroy ordered retribution. Fauntleroy targeted Manuelito's village for attack. Although the army succeeded in surprising the village, Manuelito escaped the snare. The military remained active through December, but the results were minimal. Fifty Indians were purportedly slain, and the military orchestrated another worthless treaty with the Navajos.

Meanwhile, the New Mexico Territorial Legislature became impatient with the scenario. Navajo resistance continued, while the regular army seemed hapless to prevent the attacks or retaliate in kind. A public outcry for formation of militia to deal with the "Indian menace" grew proportionately larger. Army officials worried over a war to exterminate the Indians.

On April 30, 1860, violence shattered the cool morning at Fort Defiance. Estimates of one thousand or more Navajos under the combined leadership of Manuelito and Barboncito spearheaded an assault on the hated fort, making it one of the few recorded incidences in the history of the Indian Wars in which Indians attacked a fort. The strike nearly succeeded in overrunning the garrison before being repulsed. So audacious were Navajo forays that one came within eight miles of Santa Fe. Colonel Fauntleroy and Maj. Edward R. S. Canby cooperated in an operation to trap the Navajos, but they failed in their mission.

This latest chapter in the Army's ineptitude prompted New Mexico's citizens to raise militia. Without waiting for official sanction from Governor Abraham Rencher, New Mexicans organized a volunteer battalion of five companies. They marched into Navajo country bent on destroying any Indians they encountered. The militia killed and murdered; livestock was destroyed or run off; and women and children taken as prisoners of war. The brutality ended only when the militia depleted their supply of ammunition. Despite taking matters into their own hands, the harsh civilian techniques did produce an immediate if not long-lasting impact, an armistice.

But peace was fleeting. The approaching storm of sectional differences exploded in April 1861, influencing even far-off New Mexico. Federal officials reacted swiftly. Regular U.S. Army troops would have to be withdrawn from most of New Mexico's garrisons. Some of the soldiers went East to join Union armies to fight the Confederates. In addition, a Confederate threat to New Mexico, emanating from the west Texas town of El Paso, forced officials to scatter the remaining regular forces along the Rio Grande corridor, the natural route of any Confederate invasion. The second concern was to find a suitable commander for the remaining regular forces in New Mexico. In June 1861, Major Edward R.S. Canby was promoted to the rank of colonel and given the responsibility for New Mexico's defenses. A veteran officer, Canby had served in Florida during the second Seminole War, the Mexican War with Bvt. Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, and possessed extensive experience in the Southwest. Canby manifested a mild dignified manner. He preferred civilian attire over the regulation army blouse, his "prudent" appearance highlighted by a cigar habitually placed in his mouth, although seldom lit. When he did smoke, he selected a pipe. [4] Prior to the appointment of Canby, Federal officers began the concentration of troops in the Rio Grande Valley and southern New Mexico. In April Fort Defiance was abandoned. That left one post to protect west central New Mexico from Navajo attack--Fort Fauntleroy.

Authorized on August 31, 1860, Fort Fauntleroy's primary purpose focused on combating Navajo retaliation. The garrison stood approximately 50 miles southeast of Fort Defiance and about 35 miles west of the malpais. Its location at Bear Spring, a popular stopover and gathering place for the Navajos, had been the site of Colonel Doniphan's treaty of 1846 with the Navajos. The post played host to a second treaty signing in early 1861, following the inconclusive campaign of Fauntleroy and Canby to entrap the Navajo. For the time being, Fort Fauntleroy remained an active post. Its fate hinged on the activities of Confederates in Texas. Meanwhile, following the exodus of Regular troops, New Mexico volunteers filled the void at Fauntleroy. Companies A, B, and C of the 2nd Regiment, New Mexico Volunteers, garrisoned the post after April 1861. [5]

On ration day, September 22, 1861, Navajos assembled at Fort Fauntleroy to receive their monthly food allotments, an inducement employed by the federals to keep the Navajos from raiding. As customary practice, a series of horse races between Navajos and soldiers developed. The seemingly harmless races became the catalyst for tragedy. In the grand finale, the Navajo rider lost the contest but immediately lodged a protest that the American rider had committed a foul. The Navajos declared someone had severed the reins to the Indian horse, thereby causing their jockey to lose control of his mount. Since wagers were heavy, the unsympathetic soldiers declined a re-run, foul play or not. Angry Navajos stormed the fort. A nervous sentry fired on an Indian at point-blank range. To complete the melee, the military brought out its howitzers to shell any Indians in range. When the dust cleared 12 Navajos lay dead or dying, and another 40 suffered from various wounds. The casualties included a Navajo woman and her two small children. [6]

When Col. Canby learned of the incident, neither he, and the civilian population exhibited any remorse. In fact, Canby perceived the slaughter at Fauntleroy as appropriate medicine to deter the Navajos from further raiding. It did not. If anything, it instilled in the Navajos a deep and bitter resentment towards the New Mexicans, fueling the flames of aggression. To the Navajos, the death of their kinfolks served to strengthen their perceptions of New Mexicans as deceitful and treacherous.

Because of a Confederate threat to the Rio Grande Valley, Canby in September 1861, abandoned Fort Fauntleroy leaving no military installations in west central New Mexico. He transported quartermaster stores to Cubero and housed them in rented buildings for safekeeping. Four Confederate sympathizers quickly seized the tiny garrison at Cubero and sent the supplies to Confederate authorities. [7] The Navajos interpreted the withdrawal of troops as an omen of having sapped the fighting spirit of the military. Coinciding with the receding blue troops, came the resumption of Indian strikes on villages, ranches, and mines. A frustrated Canby headquartered at Fort Craig remained powerless to halt them, for he had no available forces. In the first few months of 1862, he was committed to defending New Mexico from Confederate takeover. Defense of New Mexico frontier fell to local militia units. Not until Confederate defeat at Glorieta Pass in March 1862, could Canby redirect his efforts to blunting Indian attacks permeating the Territory at every corner.

With the retreat of the Confederates into Texas, Canby returned to Santa Fe where he established headquarters in May 1862. Canby used the next few months to organize his defenses to cover the entire territory, and he devoted time to putting administrative affairs in order. Finally, in August 1862, Canby declared himself ready for a renewal against Navajo incursions. [8] Canby formalized a campaign to both protect and punish the Navajos. New forts would be constructed in Navajo country to supplant the defunct posts. Writing Washington on the subject, Canby outlined a stratagem for Indian self-preservation. He perceived a reservation system far removed from population centers of the Territory as the only viable means of preventing the extermination of the native tribes. [9] In September, he prepared for an expedition against the Navajo. However, the closure of Forts Defiance and Fauntleroy left Canby with no base of operations in western New Mexico. To remedy the problem, Canby received authorization to erect a new garrison in west-central New Mexico to take the place of the defunct posts. The tentative site selected for the new post favored the western edge of the malpais at Ojo del Gallo. The garrison was to be named Fort Wingate, in honor of Bvt. Maj. Benjamin Wingate, 5th U.S. Infantry. Wingate, a Hoosier, received debilitating wounds to his legs during the battle of Valverde, February 21, 1862. Both legs required amputation. Complications from shock and blood poisoning set in, and the infantry captain died on June 1. [10]

But Canby never implemented his Navajo removal policy or saw the construction of Ft. Wingate. Brig. Gen. James H. Carleton commander of the California volunteers became the new departmental commander in New Mexico in September 1862. Like his predecessor, Canby, Carleton possessed extensive Indian experiences. Born in Maine, December 27, 1814, he served in the militia during the Aroostock War of 1838. His experience in the Aroostock campaign led Carleton to pursue a military career. In 1839, he was appointed a second lieutenant in the 1st Dragoons. He followed his fortunes to Mexico serving as aide to Maj. Gen. John Wool. At Buena Vista Carleton received a brevet for gallantry. Following the Mexican War, Carleton's company returned to Arizona, but Carleton remained in the East to study and correlate European cavalry tactics. In 1861 Carleton received promotion to Major of the 6th Cavalry. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Carleton took leave of the regular army to become colonel of the 1st California Infantry Volunteers, an appointment influenced by Carleton's mentor and close friend, Maj. Gen. Edwin Sumner. Sumner ordered Carleton "to retake Arizona and New Mexico." [11] Autocratic, tyrannical, and sometimes a harsh disciplinarian, he was not a man to be trifled with. [12]

Upon arrival in Santa Fe, the vigorous Carleton immediately proceeded to take measures to curb the Indian raids in New Mexico. Carleton adhered to much of his predecessor's philosophy for dealing with the Navajos such as the placement of Navajos on a reservation, far removed and isolated from any population center. Whereas Canby formulated the fate of the Navajos, Carleton enforced the plan with devastating consequences for the Navajos. [13]

Carleton upheld Canby's design for building Fort Wingate, citing its strategic location situated where soldiers could "perform such services among the Navajos as will bring them to feel that they have been doing wrong." [14] Captain Henry R. Selden headed a board of officers to pinpoint the site for the post. Based on Selden's recommendations, the lava-filled Ojo del Gallo Valley was chosen. Two prime considerations favored the malpais location. The Ojo del Gallo Valley afforded excellent pasturage. In addition, its position, astride an intersection that blanketed the approaches of two major highways--the old military road to Fort Defiance and the Spanish highway to Zuni Pueblo--provided control and access in which to block or pursue an adversary.

Captain Henry Selden in command of Companies D and G of the lst U. S. Cavalry, formerly the lst Dragoons, first occupied the site. In late October, however, an aggregate of 11 officers and 317 enlisted men of the lst New Mexico Cavalry Volunteers reached Fort Wingate to initiate their long association at the malpais garrison. [15] The establishment of Fort Wingate dates officially from October 22, 1862, by Special Orders No. 176, Headquarters Department of New Mexico September 27, 1862. Canby never witnessed the completion of Fort Wingate. His replacement arrived on September 18, 1862. [16]

The post's new commander, Lt. Col. José Francisco Chávez, assumed command of four companies of the lst New Mexico Volunteers, Companies B, C. E. and F. [17] The majority of the officers and enlisted personnel were of Hispanic origin. With an obvious ethnocentric viewpoint, General Canby had issued orders to keep the companies in his department segregated with the exception of the New Mexico units. In the New Mexico companies, Canby required at least one officer and a quarter of the non-commissioned staff to be bilingual. [18] The appointment of Chavez to command at Wingate was indeed fortuitous. He ranked as one of New Mexico's favorite sons and was stepson to Governor Henry Connelly. Born in Bernallilo County in 1833, Chavez attended schools at St. Louis University and later spent two years at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City. Prior to the Civil War he engaged in expanding the sheep industry. A staunch Unionist, he joined the 1st New Mexico Volunteers with the rank of major. When Ceran St. Vrain resigned as colonel of the 1st New Mexico, Christopher Carson became the regiment's colonel and Chavez elevated to the lieutenant colonelcy slot. [19]

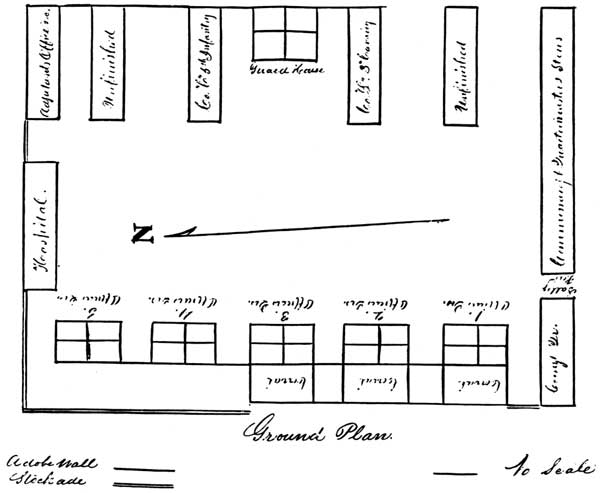

In constructing the perimeter of the post, approved designs dictated the fort's dissection at right angles and along the cardinal points for added protection against attacks. A large open space was reserved between officer's quarters and company quarters forming an imposing parade ground. Sycamore trees were planted around the edge of the parade ground offering a shaded and symmetrically pleasing atmosphere to the company street. [20]

Chavez's first order of business at Fort Wingate, per instructions from General Carleton was the preparation of shelter for the sick followed in priority order by the construction of buildings to house stores, animals, and then the men. [21] Although construction progressed at a furious pace, the post would never be fully completed due to incessant demands for scouting missions against Navajos and the fort's poor site. Built on top of a swampy plain with groundwater only two feet below the surface, the fort had major structural problems. The alkaline water extracted a heavy toll on the adobe walls reducing them in short order to a spongy, decaying mess. Officers complained that they spent more time repairing the structures than they did building them. [22] Because of the urgency for shelter, most of the buildings were built in quick and shoddy fashion. Many structures were substandard or never finished. As late as 1864 the post hospital, officers quarters, and guardhouse were incomplete. The quartermaster storehouse had a dirt floor. Enlisted men were still being sheltered in tents, which habitually fell down in heavy winds. [23]

The indefatigable Col. Chavez devoted energy and time to constructing shelter, a task made difficult with the onset of winter only weeks away. On November 7, he wrote Capt. Ben Cutler, Assistant Adjutant General in Santa Fe, that a garrison work detail had nearly completed a 2,000-yard irrigation ditch connecting Fort Wingate to the springs at Ojo del Gallo. Other soldiers, Chavez wrote, were dispatched to the nearby Zuni Mountains to fell timber for use in erecting storehouses and corrals. As a footnote Chavez added, "but I am afraid that we will not be able to have everything under shelter before cold weather on account of the small amount of transportation now at this post." [24]

Chavez's fears were no exaggeration. Capt. Julius C. Shaw described Wingate in a letter of December 1862 that was printed in the March 13, 1863, San Francisco Alta California: "The fort looks vastly fine on paper, but as yet it has no other existence. The garrison consists of four companies of my regiment--The Fourth New Mexico Mounted Rifles--and we live on, or rather exist, in holes or excavations, made in the earth, over which our cloth tents are pitched. We are supplied also with fire places, chimneys, etc., and on the whole, during the beautiful pleasant weather of the past few weeks, have enjoyed ourselves quite well. Our camp presents more appearance of a gypsy encampment than anything else I can compare it to." [25]

To expedite construction, Chavez sent fatigue parties to cannibalize razed Fort Lyon and retrieve all salvageable materials. Unlike most western frontier military forts, which never built wooden stockades to surround the post, Fort Wingate did. Plans called for a stockade 4,340 feet long and 8 feet high. [26] More than one million feet of lumber went into its construction. In addition to the timber, 9, 317 feet of adobe walls, one foot thick and eight feet high were required. [27] Lieutenant Allen L. Anderson, 5th Infantry and Acting Engineer Officer, commented that $45,000 in appropriations would be required to construct the post, a cost figure approved by Washington. [28] While Col. Chavez hastened to build the post, he did not ignore his objective--the Navajos. In an effort to differentiate friendly Navajos from those disposed to be unfriendly to the government, Chavez sent notices inviting the Indians to Fort Wingate. It came to no one's surprise that few accepted his invitation. [29]

Meanwhile, General Carleton set into motion his Indian relocation plan for the Navajos and Mescalero Apaches. The Bosque Redondo at Fort Sumner became the designated collecting point and permanent home for both tribes. "The purpose I have in view," wrote Carleton, "is to send all captured Navajos and Apaches to that point [Bosque Redondo], and there to feed and take care of them until they have opened farms and became able to support themselves, as the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico are doing. Removal should be the "sine qua non" of peace." [30]

By the fall of 1862, Navajos began to reflect concern with the military buildup at Fort Wingate. A Navajo delegation journeyed to Santa Fe in December to discuss a peace proposal. A stern Carleton informed the 18 assembled Indians, including war chiefs Delgadito and Barboncito, that "they could have no peace until they would give other guarantees than their word that the peace should be kept." [31] Unless the Navajos accepted peace on unconditional terms of the U.S. Government, a war of attrition was eminent. The Navajos were noncommittal but not intimidated by white man's talk.

|

|

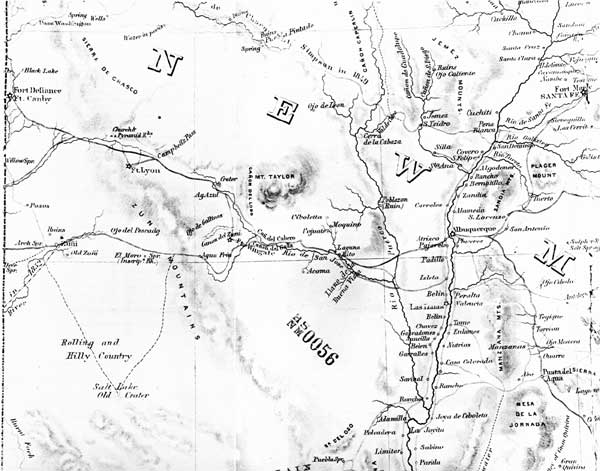

Figure 1. Fort Wingate Environs taken from territorial map of New Mexico, 1867.

Courtesy Museum of New Mexico, Neg. No. 142599. (click on map for a larger image) |

While Carleton warned the Navajos of their impending fate, Col. Chavez stockpiled mountains of supplied at Fort Wingate for a spring campaign. In February 1863, Chavez and the New Mexico Volunteers underwent their baptism of fire against the Navajos. An undetermined number of Navajos disrupted mundane post routines when they breached the corral and stole four horses. A punitive expedition sent after the perpetrators failed to apprehend the horse thieves. [32] Occurring at the same time as the horse raid, Indians ambushed and killed four Mexicans and one friendly Navajo on the Cebolleta and Cubero road east of Fort Wingate. The assailants escaped.

The ill-tempered Carleton fumed at Chavez's report that outlined the horse stealing sortie. Carleton fired a stinging reprimand to Chavez ordering him to seize 20 men and their families, and hold them for hostages until the horses were returned. He finished his missive with, "what Col Chavez does he must with a strong firm hand. Child's play with the Navajo must stop henceforth." [33]

In April General Carleton inspected Fort Wingate. He divulged to Chavez his plans for the ultimate fate of the Navajos. Peaceful factions would be transferred to Bosque Redondo. Truculent parties would be hunted down and killed if they resisted removal. About May 1 at the village of Cubero, Carleton and Lt. Col. Chavez again conferred with Navajo statesmen willing to listen to the white men. Indian dignitaries included Degadito and Barboncito. Carleton explained the options to the attentive warriors. It was not what they wanted to hear. Barboncito denounced the proposal, declaring he would neither go to eastern New Mexico nor fight. Writing on the episode, Col. Chavez quipped, "When it comes to the pinch he will fight run or go to Bosque Redondo." [34]

To combat the Navajos, Chavez mustered less than 300 soldiers with only one mounted company. [35] As spring turned to summer, Indian harassments near the malpais post escalated. On June 24, Navajos repeated their penetration of the horse corral, this time absconding with three head of oxen and driving off some horses. Chavez directed Capt. Chacón to recover the stolen stock and punish the marauders. Chacón with twenty-two men tracked the offenders up the old Fort Defiance Road. On the 28th he overtook the rear of the Navajos. Mounting a charge, the New Mexico Volunteers scattered the surprised warriors and recaptured four horses and a mule. [36]

While Fort Wingate troops parried with the Navajos, General Carleton declared himself ready to take the fight to the Navajos. And the General meant business. Messages were transmitted to Fort Wingate, informing Col. Chavez to reopen communications with the Navajos. Carleton admonished his subordinate to instruct the chiefs they had until July 20 to surrender or face dire military consequences. [37] On July 7, Barboncito, Delgadito, and Sarracino conferred with Chavez. The colonel acquainted the chiefs with the ultimatum. Barboncito, the spokesperson, appealed to Chavez that the chiefs desired peace but did not wish to move to Bosque Redondo. The meeting expired with the chiefs remaining non-committal concerning surrender or removal.

No one in the army hierarchy seriously entertained thoughts of Navajo capitulation. At the head of the list stood General Carleton. Even before the July 20th deadline, he set into motion a summer campaign to break Navajo resistance. On July 7, the aggressive Colonel Carson left Los Pinos, situated 20 miles south of Albuquerque, with a detachment of 750 soldiers and Indian auxiliaries. Marching rapidly, Carson reached Fort Wingate on July 10. The fort resembled a beehive as soldiers prepared for field service. A mountain of quartermaster supplies foretold Fort Wingate's importance as a supply depot in the ensuing months.

Carson lingered but four days at Fort Wingate before striking out to re-establish a fort in the heart of Navajo country. Carson converted the blackened rubble of former Fort Defiance into headquarters and dubbed the new site, Fort Canby. Unleashing 200 Ute scouts, Carson sent them forward in search of their old nemesis. The Navajos managed to avoid collision with the Utes and the troops but their peach orchards, fields of ripening corn, and their livestock fell to the despoilers. [38]

While Carson's forces perfected a systematic destruction of Navajo land, Fort Wingate's soldiers remained alert. Given the prevailing attitudes of the period, the predominantly Hispanic New Mexico Volunteers and the almost exclusive Anglos comprising the California column, existed in racial harmony while serving together at Fort Wingate. [39] Captain Chacón recalled in his memoirs that relations with the California troops were always cordial. [40] Whatever their ethnic differences, the two cultures found commonality in that they were Volunteers and hence were considered inferior to Regular troops. Moreover, they bonded together in a common cause--a desire to hunt down and kill, if necessary, all Navajos who did not adhere to General Carleton's Bosque Redondo plan. In an effort to harass and wear down the Navajos, scouting and reconnoitering parties flooded the region. On July 30, 1863, Major Edward B. Willis departed Fort Wingate with Company C, 1st California Volunteers, one of two California companies temporarily assigned to the post, and Company F, 1st New Mexico Cavalry. Willis' scout, which carried him into Arizona, flushed no Indians but did serve Carleton by forcing the Indians to move their camps. [41]

In August Capt. Rafael Chacón spearheaded another grueling reconnaissance. The New Mexicans overtook a party of Navajos near the Salt Lakes, south of Zuni Pueblo. Chacon dispersed the Indians, killing two warriors and capturing ten women and children. On August 28 his detachment pummeled another Navajo encampment. In a dawn attack, the New Mexicans scattered the village capturing 60 women and children, 6,000 sheep, and 30 horses. [42]

While Chacon chased Indians across portions of New Mexico and Arizona, the Navajos initiated a surreptitious visit to the malpais. On August 31, Navajos assailed a wagon train five miles from the post. The celerity of the assault succeeded in wounding one man and forcing the soldiers to relinquish their wagons to the jubilant warriors. [43] On September 16 the Indians struck again, this time stampeding Capt. Chacon's horses grazing five miles from the post. Colonel Chavez gave pursuit but halted after an abortive 30 mile chase. [44] The nettlesome assaults on Fort Wingate persisted, serving to infuriate Carleton and drive a wedge of discord between him and Colonel Chavez. Relations deteriorated in a litany of angry messages from Carleton. A proud Chavez, stung by the criticism, searched for relief from the tyrannical Carleton. [45] Probably using influence with his step-father, Governor Henry Connelly, Chavez garnered an assignment away from Fort Wingate and the martinet, Carleton. In December, he headed a battalion of Missouri and New Mexico Volunteers escorting the newly appointed Governor of Arizona Territory to Fort Whipple. [46]

Meanwhile, Forts Canby and Wingate were converted into temporary detention centers before sending prisoners to Fort Sumner. On October 21, a contingent of warriors converged on Fort Wingate for the purpose of demonstrating peaceful overtures. Again, the military response to the peace proposal remained uncompromising--"All must come in and go to the Bosque Redondo, or remain in their own country at war." [47] In November Delgadito's destitute band became the first major Navajo faction to surrender when he and 187 followers traveled to Fort Wingate. Under military escort, Delgadito's group made the long trek to Fort Sumner. [48]

But it remained to Carleton's chief war architect, Col. Carson, to strike a decisive blow against the Navajos. In January 1864, Carson took dead aim at that bastion of Navajo citadels--Canyon de Chelly. The expedition succeeded in destroying valuable Navajos supplies. Stunned by Carson's hammer blows, the Navajos faced two unpleasant alternatives--surrender and become wards of the Army, or retreat farther into the abyss of their vast domain and subsist off nature's meager bounty of pinon nuts and wild potatoes. Danger impaled the latter course. If the army did not find them, then the Utes or Puebloans might. [49] Realizing the futility of resistance, many Navajos yielded to the dictates of the government. The remaining Indians, their will unbent, determined to resist until the bitter end.

On February 1, 1864, 800 half-starved and half-frozen Navajos congregated outside Fort Canby, awaiting transportation to Fort Sumner. The scenario duplicated itself the next day at Fort Wingate, where a ragtag group of 680 Navajos assembled. By March 1, the ranks of homeless Navajos mushroomed to 2,500. The Santa Fe Gazette gleefully revealed, "There are now about 1600 Indians here, and perhaps an equal number on their way to Fort Wingate so that the rate they arrive daily we will in less than three weeks have about five thousand on the reservation." [50]

On March 4, a pitiful band of 2,000 Indians departed Fort Canby on their "long walk" to Bosque Redondo. The young, the aged, and the infirmed rode in wagons, while the healthy trailed beside. Most were ill-clad, many exhibited symptoms of malnutrition. Some succumbed to exhaustion but most died from dysentery attributed to poor preparation of flour. The army issued flour but failed to provide cooking instructions. Many Navajos devoured the flour raw or mixed water with it to form a paste or gruel; still other Indians, poorly clad, succumbed from exposure to a chilling March cold. Their trail was easily identified by the number of corpses that lined the road between Forts Canby, Wingate and Sumner. One hundred and twenty-six perished. [51]

The human suffering only worsened in the succeeding weeks. Captain Francis McCabe of the 1st New Mexico Cavalry Volunteers left Fort Canby on March 20 in charge of another Navajo caravan bound for Fort Sumner. Snowstorms pelted the column making travel miserable. Reaching Fort Wingate, McCabe grimaced when he discerned that headquarters had not forwarded sufficient food or blankets for his pathetic captives.

The unexpected surrender of so many Indians at one time caught General Carleton and Fort Wingate off balance and in an embarrassing situation. Carleton instructed Fort Wingate to "place all troops on half rations." The Indians too were placed on half rations. When another 146 hungry Navajos showed up, rations were again reduced. McCabe finished his trek to Fort Sumner but not without tragedy and human suffering. In his report, McCabe revealed that 110 Indians died en route, another 25 escaped. He noted that many Indians had departed Fort Canby without benefit of warm clothing. Blankets were not issued until the column reached Los Pinos on the Rio Grande. [52] The demise of the proud Navajos caused New Mexicans to rejoice enthusiastically. Governor Connelly proclaimed the first Thursday in April as a day of prayer and thanksgiving. He honored General Carleton and his troops for their successful campaign. Santa Fe church bells rang gloriously in the wake of Navajo misery.

In the spring and summer of 1864, Navajos surrendered in droves. At Fort Wingate, the new post commander Maj. Ethan W. Eaton spent much of his time processing Navajos for shipment to Fort Sumner. Vigilance, however, could not be relaxed. Manuelito's band remained defiant. Eaton maintained patrols, scouring the territory in search of the recalcitrant warrior.

During the summer, the hard-driving Carson continued to lay waste to the Navajo homelands. Returning to Canyon de Chelly, Carson's pyrotechnics razed the ripening orchards and fields of crops, which tightened the strangulation hold on the Navajos. As summer turned to autumn, more Navajos joined their relatives at Bosque Redondo.

In October, Major Eaton reported the surrender of 1,000 Navajos at Fort Wingate, additional evidence of the effectiveness of Carson's sacking of Canyon de Chelly and the Fort Wingate patrols. With the advent of cold weather, Fort Wingate troops settled into a winter routine. Garrison life focused on the mundane chores of escorting military supply wagons to and from Fort Canby, assisting in never-ending construction activities, and superintending to the needs of the Navajos who continued to dribble into the fort. But even the cold brace of winter did not eliminate Fort Wingate troops from campaigning. On January 2, 1865, a detachment under Lt. Jose Sanchez left their creature comforts to punish sheep-stealing Indians. The column found no Indians but did blunder into a raging snowstorm near the Datil Mountains, which obliterated all traces of the marauders. Sanchez returned to the post empty-handed, reporting that his command subsisted for three days on nothing more than boiled wheat. Although they did not encounter Indians, their presence forced the Navajos who were already in a weakened condition to move their camps. [53]

To induce Manuelito's band, which represented the largest remaining contingent of Navajos opposing exodus to Bosque Redondo to surrender, General Carleton sent three Navajos to Fort Wingate for the purpose of establishing communications with the proud warrior. Near Zuni they made contact with Manuelito's camp. Despite persuasion, Manuelito remained unyielding. While he would not go to Bosque Redondo, some of his followers postulated a different viewpoint. The peace emissary returned to Fort Wingate and presented their findings. They reported that about 350 Navajos remained at large. [54]

During the winter, small groups of Navajos continued to migrate to Fort Wingate. Some endeavored to establish their camp about a mile from the post as a sign of friendliness towards the government and thus hoping their actions would sway the army to allow them to settle near the post. When Major Ethan Eaton learned of their presence he informed them they must go to Bosque Redondo--no exceptions, regardless of their peaceful intentions. [55] Rather than risk the uncertainty of eastern New Mexico, the Navajos bolted electing to take their chances on the run. After discovering the Navajos had jumped, an angry Major Eaton instructed Capt. Donaciano Montoya to take 25 men from Companies B and F of the 1st New Mexico Cavalry, who were all dismounted, and track down the runaways. Eaton admonished Montoya, "If they refuse to return and resisted, to bring them in by force--If they fought, to kill all he could. Women and children to be spared as much as possible." Montoya's foot cavalry, languishing on the trail in a snowstorm managed to capture just two women and a child. Soldiers did prevail in killing one warrior who lingered too long in an attempt to rescue the family. [56]

Meanwhile, the Hispanic communities of Cubero, San Mateo, and Cebolleta located north and east of Fort Wingate, came under repeated assaults by Navajo bands. Predominantly poor, the villagers nevertheless, accumulated large herds of sheep and other livestock, which were routinely relinquished to raiding Navajos who had never gone to Bosque Redondo, or Indians returning from Bosque Redondo. Caught in the middle, the villagers sought retribution.

In May, Antonio Mexicano and citizens of Cubero paid a visit to Fort Wingate complaining of loss of livestock. With so few troops available for patrols, and the lack of serviceable horses, Eaton could offer little assistance. Mexicano proposed that Cuberoans assemble a citizen-armed force and hunt down the marauding bands who pillaged the countryside. The military normally held citizen-formed armies in low esteem, due to their excess in killing and plundering. New Fort Wingate commander, Lt. Col. Julius Shaw, endorsed the concept and forwarded the plan to Santa Fe. General Carleton realized that his Volunteers alone could not finish the job, and he too, perceived the citizen army as a means of breaking Navajo spirit.

Mexicano's contingent joined with 75 Zunis to form a formidable command. Returning to Fort Wingate May 25, Mexicano boasted a successful campaign. In less than 10 days the Cubero-Zuni column, claimed Mexicano, killed 21 Navajos and captured 5 women in a fight 9 miles from Zuni. To back his brag, Mexicano displayed 16 pairs of ears but did not elaborate from what age or gender his grisly trophies originated. [57] On the same day that Col. Shaw learned the details of Mexicano's expedition, Navajos assaulted a timber camp just 6 miles from the post wounding one teamster. A military escort drove off the assailants. Colonel Shaw, a strong supporter of the use of civilian columns in repelling attacks, sent a dispatch to General Carleton justifying the employment of civilians to hunt down the Navajos. Shaw grumped that incessant scouting missions reduced his effective fo [58]rce to a mere 69 privates and 35 serviceable horses. [59]

In June the energetic Mexicano returned to the field. On July 10 Shaw reported to Carleton that approximately 50 Hispanics under the direction of Mexicano attacked Manuelito's camp 75 miles southwest of Fort Canby. Although Manuelito escaped, the command captured 18 horses plus all camp impedimenta. Pleased with Mexicano's campaign, Shaw informed Carleton that if the military would provide ammunition and food at cost to the citizens, that the communities of Cebolleta and Acoma would place more men in the field. [60]

With army endorsement, civilian raiding parties escalated. In June Juan Vigil led fellow Abiquiu citizens on an expedition that penetrated Arizona. Vigil's party fought several running engagements with the Navajos reporting the death of 9 Indians and capturing 85 while losing two men. His force recovered a thousand head of horses and sheep, which they commandeered for themselves but promptly lost to a Navajo counterattack. [61] In August Shaw announced another non-military success as Zunis collided with Navajos near that pueblo. In the ensuing fight, Zunis killed four and captured seven while losing only one warrior. [62]

Compared to the citizen expeditions, Shaw's troops remained impotent. Two August missions led by Captains Montoya and Nicholas Hodt proved dismal. Montoya tracked Navajos toward Canyon de Chelly but netted only 4 women captives. [63] Captain Hodt's scout drifted to the southwest in search of Indians fleeing from Bosque Redondo. In a grueling march, Hodt trekked 401 miles but found no one. [64]

Because of the increased military and citizen forays, which enslaved some of their people, Navajo incursions persisted and intensified in the Ojo del Gallo region. In October Indians ambushed a party of soldiers providing escort for the mail 7 miles from Fort Wingate. The soldiers managed to return safely to the fort but citizen Manuel Martín was not as lucky. Martin fell in a rain of arrows and lead. Although severely wounded, he held off his attackers and was brought to the fort. In conjunction with the mail attack, Indians assaulted a civilian couple on the Cubero road, killing the woman and wounding the man. [65]

So persistent were the Navajo thrusts that Ramón Baca, Justice of the Peace for San Mateo, petitioned Col. Shaw to detach 20-25 soldiers to protect the settlement from numerous gangs of Navajos who robbed and murdered. [66] Shaw declined, stating he could not spare the men. He suggested that the citizens form another private expedition to punish the Navajos promising to provide a thousand rounds of ammunition. [67] The citizens accepted Shaw's offer and promptly elected the venerable Antonio Mexicano to head the expedition. With most of San Mateo's eligible males away on campaign, Carleton ordered Col. Shaw to station troops at San Mateo to protect women and property. Lt. John Feary and 11 men were detached to San Mateo for 60 days if needed. Local citizens provided quarters for the men. [68]

Based on the success of San Mateo citizens in receiving military aid against Navajo attacks, a delegation from Cubero on March 8 delivered at Fort Wingate a signed petition seeking assistance. The petition enumerated outrages committed on the citizenry between February 1 and March 6. In that span, Navajos lifted more than 2,200 head of livestock and killed one herder. [69] A sympathetic Shaw declined assistance to the beleaguered assembly noting he simply did not have any extra troops.

Two weeks later Carleton received a report from Fort Wingate detailing another attack on troopers escorting the mail. This time the expressmen were not so fortunate. Three soldiers fell in the assault, the fourth was missing but later turned up unharmed at Cubero. [70] The new post commander, Capt. Edmund Butler of the 5th United States Infantry, could spare only ten men under Capt. Hodt to give pursuit because other columns were already in the field--reconnaissances to Canyon de Chelly and Datil Mountains. Hodt's small punitive force pressed the Indians. On the fourth day, Hodt ambushed the warriors, killing 1 and wounding several. As proof that these Indians were responsible for the expressmen killings, Hodt found in the camp a horse belonging to one of the dead troopers. He noted that most of the Indians appeared to be Apaches, not Navajos. Hodt pursued the Indians toward Sierra Blanca but turned back because of worn-out horses. [71]

Expeditions from Fort Wingate increased after the death of the expressmen but proved largely ineffective owing to the vastness of the territory and the guerrilla-like tactics of the Navajos and Apaches. Nevertheless, Capt. Butler predicted that if the Indians were hotly pressed, they will either "starve or surrender because of shortage of food." [72] Butler's assessment of the Navajo's plight was accurate. Military patrols combed the region. Citizen caravans roamed the countryside. Puebloan Indians organized war parties. And now the Utes, arch-enemies of the Navajos, initiated a war on the suffering Navajos. The few Navajos who remained in their shrinking domain, crumbled under the constant pressure. It was either death by starvation or acceptance of Bosque Redondo. On September 1, Manuelito sent word to Fort Wingate that he, too, desired to lay down his arms. In company of officers, Capt. Edmund Butler rode out to the Navajo camp located southwest of the post in the direction of Agua Fria. Butler found Manuelito and 23 of his followers. Manuelito presented himself to the cadre of officers, his left arm dangling uselessly by his side, pierced by a bullet in a skirmish several weeks earlier. [73] Manuelito's capitulation spurred the remaining holdouts to surrender. On November 7 the redoubtable Barboncito, a defector from Bosque Redondo, turned himself in at Fort Wingate with 64 of his people. By mid-December, Butler reported to headquarters the processing and deportation of more than 550 Navajos. [74]

The surrender of Manuelito marked the high point of Fort Wingate's service in the Navajo wars. Companies B and F of the 1st New Mexico Cavalry, who served the longest stint at the post, along with Company G, 1st California Volunteers, witnessed Manuelito's surrender. A week later the Volunteers were ordered to Albuquerque for mustering out of the Army. [75] Indian attacks diminished but did not vanish following the capitulation of Manuelito's and Barboncito's forces. U.S. Regulars from Company C, 5th U.S. Infantry and Company L, 3rd U.S. Cavarly, stationed at Fort Wingate in 1867, were constantly engaged in blocking the path of Navajos streaming from Bosque Redondo. Indian sightings by San Mateo citizens and the report of Hispanic killings at Cebolleta kept Capt. Butler's garrison in a state of flux. [76]

While Butler endeavored to maintain a representative force to deter sporadic Navajo and Apache raids, he focused his summer attention to dealing with the rapid deterioration of the fort's fabric, which rendered the post unfit for human habitation. A Board of Officers convened on July 29 to examine the allegations and report recommendations. In their inspection, the board found the post "insufficient and so much out of repair as to be unfit for use." The board noted that the walls of the officers quarters, company quarters, commissary, and quartermaster building, hospital, and guardhouse were gradually settling due to an absence of a foundation to support them. Moreover, they added, "alkaline is eating away portions of the walls" and that adobes used in the construction were of inferior quality. The board recommended that the buildings be condemned as unsafe and unfit for use. [77]

Major General George Getty, Carleton's replacement as district commander, returned the report to Capt. Butler requesting his recommendations. Butler responded suggesting the post's abandonment and reconstruction 1500-2000 yards to the southwest, away from the alkali swamp that now inundated and infested the fort. Butler characterized the adobe decay as so wretched that "in some places a ramrod can be pushed through the foot of the walls." In other places, walls listed so much that orders to tear them down had be issued. [78]

Superiors vacillated on Fort Wingate's course--to repair or rebuild. In May 1868, General William T. Sherman, now commanding the Military Division of the Missouri, provided some persuasive advice. On an inspection tour, he denounced the Bosque Redondo experiment as a failure citing "that the Navajos had sunk into a condition of absolute poverty and despair." [79] Sherman advocated the return of the Navajos to their homeland. In addition, he saw the need to build posts closer to the seat of Navajo activities to better manage their affairs. Fort Wingate, at Ojo del Gallo, was too far removed from the Navajos. Sherman suggested that it be closed and another post built closer to the Navajos. Military officials bit on Sherman's recommendations.

|

| Figure 2. Ground Plan of Fort Wingate, 1867. See Captain Edmund Butler to AAG, August 21, 1867, LR, Dist NM, roll 3, RG 98, from New Mexico State Archives and Records Service, Santa Fe. |

Fort Wingate was officially abandoned on July 22, 1868, the same day that the Navajos passed under the walls of the crumbling adobe post. [80] A new or second Fort Wingate was ordered constructed some 50 miles west at the ruins of Fort Lyon, near present-day Gallup. After the military closed the malpais garrison, nearby Hispanics moved into the region and utilized the surplus lumber and adobe to build new homes. Today the largely Hispanic community of San Rafael occupies the site of the former post.

Fort Wingate played a pivotal role in shaping the destiny of the Navajos serving as a staging ground for the Navajo war and as a deportation center for forwarding Navajos to Fort Sumner. Today no extant ruins of Fort Wingate exist, but its significance is recalled in the dynamics of two cultures struggling to control portions of arid New Mexico. In its brief six-year life, Wingate had played a leading role in pacifying the Indians. Thousands of Navajos had been channeled through Wingate on the way to Fort Sumner. The establishment of Wingate went far beyond its military life, 1862-1868, for its creation had expanded the frontier from Cubero to the malpais themselves. With its demise, the frontier did not recess, instead Wingate spawned the foundations for future frontier settlements. [81]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

elma/history/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 10-Apr-2001