|

El Morro National Monument New Mexico |

|

NPS photo | |

PERHAPS it was the notion of immortality, an inspiration for creativity since the dawn of the human race, that compelled people to write their lives into rock. Compared to our life spans, El Morro seems timeless. Geological and erosional forces will—in the long run—dismantle these sandstone layers, but the protective, hard rock layer at the top has delayed the process longer than on the land around it, which once rose as high.

So it seems like El Morro always existed and always will. Those wielders of stone and steel who reached out to passers-by of the future left a rare gift. An ancient Indian's carving of bighorn sheep, a Spaniard's "pasó por aquí," a precisely chiseled name from America's westward expansion These weave a variegated tapestry of the peopling of New Mexico.

El Morro is a cuesta, a long formation gently sloping upward, then dropping off abruptly at one end. The land is made up of sandstone layers deposited by wind, desert streams, and an ancient sea.

Sandwiched between the upward pressure from underground forces and the weight of newer rock above (since eroded), the sandstone has developed cracks that—gradually—weathered into the long vertical joints prominent today.

Travelers on the ancient trade route relied on El Morro's source of water, a pool of runoff and of snowmelt. Resting in the shade of the bluff, they added their messages to the rock. Today the pool waters sunflowers, cattails, and native grasses on its shore.

Pasó por aquí: Passed by here

On a main east-west trail, dating from antiquity, rises a great sandstone promontory with a pool of water at its base. The Zuñi Indians, whose Puebloan ancestors lived here, call it Atsinna—"place of writings on the rock." The Spaniards called it El Morro—The Headland. Anglo-Americans called it Inscription Rock. Over the centuries those who traveled this trail stopped to camp at the shaded oasis beneath these cliffs. They left the carved evidence of their passage—symbols, names, dates, and fragments of their stories that register the cultures and history intermingled on the rock.

The Puebloan

ANCIENT VILLAGERS

The Zuñi Indians descended from desert hunter-gatherers. About 2,000 years ago they joined in a general shift toward the cultivation of crops that gave birth to the Southwest's Pueblo culture. In time, small villages appeared along the streams of this arid land. As more centuries passed the Puebloans built large multi-storied towns laid out around plazas.

The Zuñi towns centered on the Little Colorado River drainage. As trading middlemen between the Puebloan world and other cultures of the Southwest, the Zuñi played a central role in the transmission of trade items and cultural values.

Atsinna Ruins atop El Morro dates from the time of larger towns. Archeological evidence shows that Atsinna and nearby massive pueblos were built about the same time—in the late 1200s. After only 75 years they were abandoned. (Perhaps they were meant to be only temporary: unusual heat and drought may have driven the Zuñi from the river valleys to the high ground around El Morro.)

For the Zuñi people, Atsinna and nearby sites continue to be sacred places, parts of a larger homeland that once stretched far beyond today's Zuñi Reservation. The symbols and pictures communicate both the mundane and the spiritual. Eventually a new breed of travelers took inspiration from the Indian scribes. With points of steel they continued the story in records of conquest and colonization.

HOME ON THE DESERT'S ROOFTOP

The Puebloans, ingenious farmers of the high desert, were master builders. Their earliest structures, half-buried pithouses, evolved into above-ground pueblos by 1000 CE. Soon the Puebloans were building many of their villages on mesa tops, perhaps with defense in mind or perhaps simply to be high above the plain.

Atsinna Pueblo, the largest of the pueblos atop El Morro, dates from about 1275. Its builders made use of what they had around them: flat sedimentary rock easily cut up as slabs they could pile one on top of another and cement with clay and pebbles. The pueblo was about 200 by 300 feet, and it housed between 1,000 and 1,500 people. Multiple stories of interconnected rooms—875 have been counted—surrounded an open courtyard. Square and circular kivas—underground chambers that recall the pithouse era—were spaces for informal gatherings as well as their religious ceremonies.

Corn and other crops were grown in irrigated fields down on the plain; the surplus was stored in well-sealed rooms in the pueblo against times of need. The grinding bins and firepits remain today.

Cisterns on top of the mesa collected rainwater. The pool at its base was often used too, as hand-and-toe steps on the cliff face attest. An alternate trail for the residents may have followed the one that is still in use.

The Spaniards

NEW WORLD COLONIZERS

The second generation of conquistadors—who missed the Mexican conquest—pursued a medieval myth of golden cities to be found at a place called Cibola. Shipwrecked soldiers wandering from Texas through New Spain's northern deserts heard tales of Indians living in cities yet farther north. If this was Cibola, it meant a chance to relive the glories and riches of Aztec Mexico.

For the explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado and those he led in 1540, the Zuñi and other Pueblo Indian towns proved disappointing. These Pueblo Indians lived in solid towns, pueblos built of masonry or adobe. They gained a sufficiency from their agriculture. But their riches were intangible—songs and ceremonies that kept them in harmony with the spirit world and with each other—not the gold of Aztec or of Inca.

Decades passed as New Spain's frontier slowly pushed northward, lured by discovery of silver deposits. In 1581 the Franciscan brother Fray Augustin Rodríguez shared leadership of an expedition that revisited the pueblos of New Mexico. Inspired with religious zeal, Fray Augustin and another friar stayed on with the Indians when the expedition returned. This episode was important. It foreshadowed the primary purpose of New Mexico as the northern outpost of New Spain: Lacking riches, the future colony was eventually supported and justified as a field for missionizing. Salvation of Indian souls would serve both God and State.

Another expedition, sent to search for the two friars, resulted in the first historical record of El Morro. Antonio de Espejo headed north to the Rio Grande pueblos, where he confirmed that the Franciscans had been killed. Then he explored westerly toward Zuñi. On March 11, 1583, he recorded his stop at a place he called El Estanque de Peñol (the pool at the great rock). In 1598 Don Juan de Oñate officially colonized New Mexico. He brought 400 colonists and 10 Franciscans north, along with 7,000 head of stock. From the beginning, hard winters, lack of food, and the great distance from Mexico caused hardship and discontent among the colonists. Oñate's explorations finally killed the last hopes for quick riches. Returning from one of these expeditions, Oñate inscribed his name at El Morro on April 16, 1605—the first known European inscription on the rock.

There followed scores of other Spanish inscriptions as governors, soldiers, and priests took the El Morro route to Zuñi and other western pueblos. These brief notes in stone give a thumbnail sketch of New Mexico's Spanish history as it happened on those far western marches. Routine records of passage—a name and a date attached to the standard pasó por aquí—vary with accounts of battle and revenge for an ambushed detachment or a martyred priest. For this was the very fringe of the New Mexican frontier, far from Santa Fe. The western Pueblo Indians used this distance to buffer Spain's religious and secular controls.

Over the years, resentment over these controls forged Pueblo Indian unity. Revolting in 1680 they killed or drove the Spaniards from New Mexico. After the Reconquest by Don Diego de Vargas (recorded by the general on El Morro in fall 1692), peace and war alternated on the western marches, according to the character of the missionaries and governors. By 1750 the energies of both Church and State had declined in the poor, isolated province of New Mexico. Increased warfare with the encircling Navajo, Apache, Ute, and Comanche Indians was part of the cause. Few Spanish travelers passed by El Morro during this period.

A final surge of Navajo campaigns, trail blazing, and visits to the Zuñi and Hopi pueblos took place as the 1700s shaded into the 1800s. But in fact the western pueblos and El Morro stood beyond the effective dominion of Spain. During the years under Mexico, 1821-46, New Mexicans devoted their western frontier energies to war with the Navajo Indians north of the Zuñi-El Morro area. Indian travelers had the rock and its pool mainly to themselves.

OÑATE: THE LAST CONQUISTADOR

In the history of Don Juan de Oñate lies the essence of the Spanish New Mexican story. He founded the first permanent colony in New Mexico, explored its terrain, and opened a history that has lasted 400 years. He was visionary, tenacious, sometimes ruthless, and always courageous—in every way a Spaniard of his time.

Hearing persistent stories of mines, threats from other powers, and the many Pueblo Indians to be missionized, Spain's Philip II decided to found the far-northern colony. Oñate got the contract. He paid for the expedition and Philip gave him honors and titles and furnished priests. Oñate's colony proved marginal. Difficulty and danger sapped the colonists' resolve. The distance from Mexico City slowed supplies and reinforcements.

Oñate came under criticism from dissidents in his own ranks. His harsh treatment of the Acoma Indians, who resisted the conquerors, prompted charges of inhumane severity at the court of inquiry examining his governorship. But despite such troubles, Oñate persevered and held the settlement together.

Oñate's expeditions brought home the truth about New Mexico. This was a country that could sustain colonists willing to work the land. Its Indians could be converted and made citizens of Spain's empire. But New Mexico lacked precious metals, so its history would be the history of villagers, Spanish and Pueblo, adjusting to each other. Oñate and the stalwart colonists and Franciscans who had survived those first hard years laid the foundation.

The Americans

EXPANDING WESTWARD

The Mexican-American War (1846-48) made New Mexico part of the United States. Army expeditions to the Zuñi country and into troubled Navajo land began at once. Lt. James H. Simpson of the Army's Topographical Engineers accompanied one of these and, with artist Richard Kern, took a side trip to El Morro in September 1849.

The beautiful inscriptions inspired the men to spend two days copying them. Midway through their task, they paused before the "exquisite picture" of the shaded pool, then climbed to El Morro's crest. From the aerie of the abandoned ruins, they took in the "extensive and pleasing prospect" below. Simpson's was the first written description of what he named Inscription Rock, and Kern's drawings were the first recording of the inscriptions.

Emigrants to California used the El Morro route. One group, escorted by a company of dragoons, passed through in 1849. Another party that same year robbed the hospitable people of Zuñi, who traditionally welcomed and fed all travelers. A later party left 26 names on the rock.

Army exploration and railroad-survey expeditions stopped at El Morro in 1851 and 1853. A few years later (1857) the Army experimented with camels for desert transportation. Thus did a caravan more Arabic than American pass by El Morro.

An 1868 Union Pacific survey party looked for a rail route past El Morro. But the 35th parallel route, earlier recommended by the Topographical Engineers, took the trains through Campbell's Pass some 25 miles north of El Morro.

When the first train steamed over the Continental Divide in 1881, the old trace past El Morro was obsolete as a long-distance thoroughfare. Traditional traffic between Acoma and Zuñi persisted. The Navajo Indians and Mormon settlers of the nearby Ramah district continued to pass by as trade, herding, and ranching demanded. But the shift of mainline transportation north of the Zuñi Mountains ended the historic function of El Morro as a watering place and camp on the long trail between the Rio Grande and western deserts.

THE U. S. ARMY CAMEL CORPS

Inscriptions reading "Beale" and "Breckinridge" recall a novel 1850s experiment by the U.S. Army. Major Henry C. Wayne and Edward F. Beale, the superintendent of Indian Affairs in California, had long tried to solve the water problem on the route from the Mississippi River to California through Southwest desert. In 1855, some men went to Europe and Africa to study the habits of camels in captivity. Buying 33 camels in Egypt and Turkey, they took on three Arab handlers, sailed back to Texas, and began training. People living near Camp Verde, Texas, admired the camels; a woman sent President Franklin Pierce a pair of socks knitted "from the pile of one of our camels."

When the westward expeditions started in 1856, the officers reported their camels superior to horse and mule trains. Another 41 camels were added to the corps in 1857. P. Gilmer Breckinridge of Virginia, in charge of 25 camels. inscribed his name as a caravan passed El Morro that year.

"The camels are coming," read a newspaper headline when these exotic beasts pulled an express wagon into Los Angeles in December 1857. "Their approach made quite a stir among the native population, most of whom had never seen the like." The article told how camels could pull a load over a mountain where mules balked, ate cactus, and could "live well where our domestic animals would die."

Camp Verde fell into Confederate hands at the beginning of the Civil War, ending the camel corps. Most of the animals were sold at auction, and some ended up in zoos and circuses. Some simply escaped; as late as the early 1900s sightings of feral camels might still be reported from Mexico to Arkansas.

Your Visit to El Morro

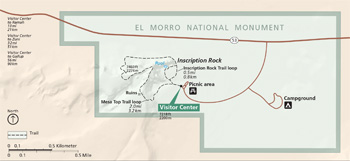

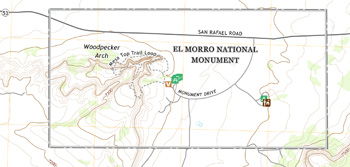

(click for larger maps) |

El Morro National Monument is 125 miles—216 hours by car—west of Albuquerque, N.Mex.

From I-40 at Grants (42 miles): go southwest on N. Mex. 53 to the park entrance on left. From I-40 at Gallup (56 miles): go south on N. Mex. 602, then east on N. Mex. 53 through Ramah to the park entrance on right. Service animals are welcome.

Facilities

There are campsites and picnic areas in the park; an RV park is near the

park entrance. Supplies and food service are available in Ramah and

lodging in Grants or in Gallup.

Climate

Expect hot, dry weather in summer, with afternoon thunderstorms in July

and August. Temperatures can dip well below freezing in winter. Adverse

weather may force temporary closure of Mesa Top Trail.

Things to see and do

The park is open year-round every day except Dec. 25 and Jan. 1. The

visitor center and trails are open daily; hours vary by seasons. Please

call or visit the website for seasonal hours. You may not enter park

trails later than one hour before the general park closing time. Check

at the visitor center for information on special events scheduled for

the day. Call or write in advance to arrange group orientation

talks.

Stop first at the visitor center. The museum has exhibits on the 700 years of human activity at El Morro. A 15-minute video gives an introduction to the park, and children can examine rock, plant, and wildlife specimens at the visitor center's touch table.

Two self-guiding trails begin at the visitor center. Guide booklets are available there; wayside exhibits mark points of interest. Inscription Rock Trail (a paved, 16-mile loop) passes the carvings at the base of the cliff.

Mesa Top Trail, two miles round-trip from the visitor center, continues upward from the lower trail. Wear sturdy shoes, carry water, and be prepared for a steep climb over varied terrain. At the top are the ancient pueblo ruins and a panoramic view.

Accessibility

The parking lot, picnic tables, campground, restrooms, and visitor

center are wheelchair-accessible. Inscription Rock Trail is paved and

wheelchair-accessible with assistance; Mesa Top Trail is not.

Safety and regulations

The hike to the top of the rock can be strenuous. Stay on the marked

hiking trails. The mesa top has 200-foot dropoffs in places. It is

illegal to disturb plants, animals, or ruins. Do not touch the

inscriptions or mark the stone in any way. For firearms regulations see

the park website.

Also nearby

El Malpais National Monument, named for the Spanish for "badlands,"

features a rough volcanic landscape that Spanish explorers wrote about

in the 1500s. The park is south of Grants off N. Mex. 53 and N. Mex.

117.

Source: NPS Brochure (2016)

|

Establishment El Morro National Monument — December 8, 1906 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Comparative Study of Epoxide Resin and Cementitious Grouts for the Delamination of Sandstone at El Morro National Monument, New Mexico (Dawn Marie Melbourne, 1994)

Birds of El Morro National Monument, Valencia County, New Mexico (D. Archibald McCallum, September 30, 1979)

El Morro: The Stone Autograph Album (George P. Godfrey, extract from The Denver Westerners Roundup, Vol. 29 No. 2, February 1973; ©Denver Posse of Westerners, all rights reserved)

El Morro Trails, El Morro National Monument, New Mexico (Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, 1994)

Foundation Document, El Morro National Monument, New Mexico (September 2014)

Foundation Document Overview, El Morro National Monument, New Mexico (October 2014)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, El Morro National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2012/588 (K. KellerLynn, October 2012)

Historic Structure Report: The Historic Pool, El Morro National Monument, New Mexico (Jerome A. Greene, February 1978)

Hydrologic Monitoring in El Morro National Monument: Water Years 2012 through 2014 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS-2018/1162 (Stephen A. Monroe and Ellen S. Soles, May 2018)

Inscription Rock (extract from El Palacio, Vol. 21 No. 9, November 1, 1926)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

El Morro (Inscription Rock) (Dwight T. Pitcaithley, August 1977)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, El Morro National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/ELMO/NRR-2016/1192 (Patricia Valentine-Darby, Allyson Mathis, Kimberly Struthers, Lisa Baril and Nina Chambers, April 2016)

Park Newspaper (InterPARK Messenger): c1990s • 1992

Paso Por Aqui: A History of Site Management at El Morro National Monument, New Mexico, U.S.A. (Antoinette Padgett and Kaisa Barthuli, extract from Management of Rock Imagery, ©Australian Rock Art Research Association, Inc., 1995; all international rights reserved)

Report on Sullys Hill Park, Casa Grande Ruin; the Muir Woods, Petrified Forest, and Other National Monuments, Including List of Bird Reserves: 1915 (HTML edition) (Secretary of the Interior, 1914)

Report on Wind Cave National Park, Sullys Hill Park, Casa Grande Ruin, Muir Woods, Petrified Forest, and Other National Monuments, Including List of Bird Reserves: 1913 (HTML edition) (Secretary of the Interior, 1914)

Romance of Emigrant Names at El Morro Southwestern Monuments Special Report No. 23 (Robert R. Budlong, May 1938)

The Analysis of Sandstone Deterioration at the Northeast Point of Inscription Rock at El Morro National Monument (©Christina A. Burris, Master's Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 2007)

The Archival Records of El Morro National Monument 1906-1962 (1993)

The Water Supply of El Morro NM (HTML edition) USGS Water-Supply Paper 1766 (Sam W. West and Hélène L. Baldwin, 1956)

The Writing on the Wall: A Cultural Landscape Study and Site Management Recommendations for Inscription Trail Loop, El Morro National Monument (©Taryn Marie D'Ambrogi, Master's Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 2009)

Vegetation Classification and Distribution Mapping Project, El Morro National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR-2010/365 (David Salas and Cory Bolen, August 2010)

Wind, Water, and Stone: The Evolution of El Morro National Monument (A. Dudley Gardner, April 1995)

Without Parallel Among Relics: An Archeological History of El Morro National Monument, New Mexico Intermountain Cultural Resources Professional Paper No. 71 (James E. Bradford, 2013)

elmo/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025