|

Fossil Butte National Monument Wyoming |

|

NPS photo | |

Three great lakes existed in the area of Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado 50 million years ago—Lake Gosiute, Lake Uinta, and Fossil Lake, the smallest. All are gone today, but they left behind a wealth of fossils in lake sediments that turned into the rocks known as the Green River Formation, made up of laminated limestone, mudstone, and volcanic ash. The fossils are among the world's most perfectly preserved remains of ancient plant and animal life. Some of these extraordinary fossils come from Fossil Lake, seen today as a flat-topped rock butte that stands near the center of the ancient lake. In 1972 Congress designated Fossil Butte National Monument to preserve the butte and its invaluable, fascinating record of the past.

The fossils of Fossil Lake are remarkable for their abundance and the broad spectrum of species found here—plants, insects, reptiles, birds, mammals, and over 20 kinds of fish. Paleontologists, scientists who study fossils, and private collectors have unearthed millions of specimens since the mid-1800s. Many billions more lie buried in the butte and surrounding ridges, protected and preserved for future paleontologists to study.

The fossils have striking detail. Many fish retain entire skeletons, teeth, delicate scales, and skin. Perhaps most remarkable is the story the fossils tell of an ancient life and landscape. The scene, during the Eocene Epoch of the Cenozoic Era, was quite different from today. Fossil Lake, 50 miles long and 20 miles wide, nestled among mountains in a lush forest of palms, figs, cypress, and other subtropical trees and shrubs. Willows, beeches, oaks, maples, and ferns grew on the lower slopes; forests of spruce and fir grew on the cool mountainsides. In and around the warm waters of the lake, animal life was diverse and abundant.

A variety of fish inhabited the tributaries, shallows, and deep water of the lake during its life of over two million years. Gars, paddlefish, bowfins, and stingrays survive today, as do herring, perch, and mooneyes. The shore bustled with crocodiles; primates and dog-sized horses inhabited the land; birds and bats took to the air.

This scene is gone now because of climate changes and the lake's disappearance. But the site of ancient Fossil Lake and its fossils will be protected in perpetuity at Fossil Butte National Monument, where paleontologists and park visitors can discover the past.

Fossils of Ancient Fossil Lake

For number, variety, and detail of fossil fish, few places can equal ancient Fossil Lake. Its fossils enable us to take a close look at what life was like at Fossil Lake 50 million years ago. Fish are the most common fossils found here. Millions of herring that swam in schools are preserved as images-in-stone. Specimens of bigger predatory fish, like five-foot-long gars and four-foot-long bowfins, are rarer. Over 20 species of freshwater fish have been identified in Fossil Lake. Many are recognizable as ancestors or are related to some of today's species. Besides fossil fish, hundreds of other life forms are captured in stone. The bones of fossil bats, the oldest complete bats in the world, and remarkably complete fossil snakes are preserved here. Snail shells, insect impressions, crocodiles, freshwater turtles, bird skeletons, feather impressions, and plant remains—leaves, seeds, stems, and flowers blown or washed into the lake—these, and more, are part of the buried treasure of fossils unearthed here.

Ideal Conditions for Making Fossils No one knows for sure what events led to the preservation of Fossil Lake's animals and plants. But scientists have developed theories to explain the process. One essential ingredient for preservation was burial in calcium carbonate. which precipitated out of the water and fell like a constant gentle rain to the bottom of Fossil Lake. This protective blanket covered whatever sank to the bottom—dead fish, fallen leaves. This took place, year after year, for hundreds of thousands of years. Some of the most perfectly preserved fossils come from the deep-water sediment layers of whitish to gray limestone alternating with brown organic layers commonly called the 18-inch layer.

These fossils are generally adult fish. An equally important fossil-bearing layer comes from nearer the lake shallows and is composed of a tan limestone with faint lamination that splits easily due to its lack of organic material. This layer—the split-fish layer—averages 6½ feet thick. Here are younger fish and species like crayfish and stingrays that lived in the near-shore shallows.

Unsolved Mystery While many of Fossil Lake's animals and plants probably died natural deaths, occasionally huge numbers of fish died suddenly. These die-offs are recorded on slabs of the Green River Formation called mass mortality layers. What killed these fish? A super-bloom of blue-green algae that used all the oxygen? A sudden change in water temperature or salinity? All of these? Ongoing research may solve the mystery.

The Age of Mammals

Life in the Cenozoic Era—the Last 65 Million Years

From simple beginnings great numbers and varieties of life forms have evolved and populated the Earth. For 140 million years before the Cenozoic Era, dinosaurs held dominion over the land. Mammals also existed, but they were small and not abundant. As the dinosaurs perished the mammals took center stage. Even as mammals increased in numbers and diversity, so did birds, reptiles, fish, insects, trees, grasses, and other life forms. The fossil record gives us a fascinating glimpse into the Cenozoic Era. Without fossils we would have little way of knowing that ancient animals and plants were different from today's. With fossils we discover that an extraordinary procession of organisms lived in North America and around the world. Species changed as the epochs of the Cenozoic Era passed. Those that could tolerate the changes in the environment survived. Other species migrated or became extinct. The fossil record tells these stories, but the study of fossil remains, paleontology, also raises many questions: What types of environments did these plants and animals live in? How did they adapt to climatic changes? How did different groups of plants and animals interrelate? How have they changed through time?

Fossils are studied in the context in which they were found and as one element in a community of organisms. Every fossil can serve as a key to unlock knowledge, so the National Park Service is especially concerned with the protection of these keys as the questions unfold. The Cenozoic: Era continues today and scientists estimate that as many as 30 million species of animals and plants now inhabit the Earth. This is a mere fraction of all life forms that have ever existed. Scientists now think that about 100 species will become extinct every day, a rate accelerated by human actions. Pollution of the air and water; destruction of forests, grasslands, and other ecosystems; and other adverse changes to Earth's environment challenge life's very ability to survive. "Looking back on the long panorama of Cenozoic life," Finnish scientist Björn Kurten has said, "I think we ought to sense the richness and beauty of life that is possible on this Earth of ours." It is no longer enough to plan for the next generation or two, Kurten suggests. We should plan "for the geological time that is ahead .... It may stretch as far into the future as time behind us extends into the past."

(Park names following captions indicate where fossils were found.)

Paleocene

Began 65 million years ago

The Paleocene Epoch began after dinosaurs became extinct. Mammals that had lived in their shadows for millions of years eventually evolved into a vast number of different forms to fill these newly vacated environmental niches. Many forms of these early mammals would soon become extinct. Others would survive to evolve into other forms.

The variety of other animals and plants also increased, and species became more specialized. Although dinosaurs were gone, birds continued to flourish, and reptiles lived on as turtles, crocodiles, lizards, and snakes.

As the Paleocene began, most mammals were tiny, like this rodent-like multituberculate. With time mammals grew in size, number, and diversity.

Palm trees and crocodilians thrived in the subtropical forests of the Paleocene and much of the Eocene.

Fossil Butte NM

Eocene

Began 55 million years ago

In the Eocene Epoch mammals emerged as the dominant land animals. They also took to the air and the sea. The increasing diversity of mammals begun in the Paleocene continued at a rapid pace in the Eocene. The many variations included some of the earliest giant mammals. Some were successful, some not. The fossil record reveals many mammals quite unlike anything seen today. Increasingly, however, there were forest plants, freshwater fish, and insects much like those seen today.

Bats, the only type of mammal ever to develop the power of active flight, took to the air more than 50 million years ago.

Fossil Butte NMMany freshwater fish lived in North American lakes during the Eocene Epoch. Gars, herring, and sunfish are similar in appearance to those Eocene fish.

Fossil Butte NMGroves of giant redwood trees once grew throughout western North America. Changes in climate were responsible for these trees' shrinking range.

Florissant Fossil Beds NMDelicate bones of shorebirds, including frigate birds, are preserved in the fine-grained sediment of Eocene lake deposits.

Fossil Butte NMThe variety of flowering plants exploded just before, during, and after the Eocene. They would populate the land with all sorts of new species of trees, shrubs, and smaller plants. Cattails grew in the shallows of Eocene freshwater lake edges.

Fossil Butte NMButterflies and many other insect groups co-evolved throughout the Cenozoic with the increasing variety of flowering plants These insects became important agents of pollination.

Florissant Fossil Beds NMAncient tapirs such as Heptodon browsed near the shores of Fossil Lake in what is now western Wyoming. Unlike modern tapirs, Heptodon had a very small snout.

Fossil Butte NMTsetse flies occur today in tropical Africa and as fossils in the Florissant formation

Florissant Fossil Beds NMCoryphodon had short, stocky limbs and five-toed, hoofed feet, closely resembling the tapir. Its brain was very small. The males had large tusks. Coryphodon also lived on land not far from the shores of Fossil Lake.

Fossil Butte NMLiving in Eocene forests, the first horse-like animals were barely bigger than today's domestic cat. Throughout the Cenozoic Era their size increased. Their legs became longer, and their feet changed from many-toed to single-hoofed for faster running. Their teeth evolved from being adapted for browsing to being adapted for grazing. Fossil horses occur at many sites in the National Park System.

Oligocene

Began 34 million years ago

The Oligocene Epoch was a time of transition between the earlier and later Cenozoic Era. The once warm and moist climate became cooler and drier. Subtropical forests gave way to more temperate forests.

Late in the Oligocene, savannas—grasslands broken by scattered woodlands—appeared. These changes caused mammals, insects, and other animals to keep trending toward specialization. Some adapted to the diminishing forests by becoming grazers. Early types of mammals continued to die out as more modern groups—dogs, cats, horses, pigs, camels, and rodents—rose to new prominence.

Ekgmowechashala marked the end of the original primate lineage in North America. A small lemur-like primate, it may have used large skin folds to glide from tree to tree. Its name means "little cat man" in Lakota, which the discoverer understood to be their name for monkey.

John Day Fossil Beds NMOreodonts, a group of sheep-like animals, were successful in the Eocene and Oligocene. By the end of the Miocene they had completely died out.

Badlands NP

Miocene

Began 23 million years ago

The abundance of mammals peaked in the Miocene Epoch. The refinement in life forms that marked this epoch saw many animals and plants develop features recognizable in some species today. The forests and savannas persisted in some parts of North America. Treeless plains expanded where cool, dry conditions prevailed. Many mammals adapted for prairie life by becoming grazers, runners, or burrowers. Large and small carnivores evolved to prey on these plains-dwellers. Great intercontinental migrations took place throughout the Miocene, with various animals entering or leaving North America.

Moropus was a distant relative of the horse and one of the more puzzling mammals. For many years paleontologists thought its feet had claws rather than hooves.

Agate Fossil Beds NMLacking other defenses, some larger rodents, such as the dry-land beaver Palaeocastor, lived in colonies beneath the High Plains of North America. Their burrows remain as trace fossils today.

Agate Fossil Beds NMRhinos were varied and abundant during most of the Cenozoic Era. Around the world they ranged in size from the three-foot-tall North American species Menoceras to a giant Asian species, the largest land mammal yet found in the fossil record.

Agate Fossil Beds NMDaphoenodon was carnivorous. It differed from the earliest true dogs of the Oligocene Epoch. Its so-called "beardog" family eventually went extinct.

Agate Fossil Beds NMDaeodon (formerly called Dinohyus, "terrible hog") had bone-crushing teeth enabling it to scavenge the remains of other grassland animals.

Agate Fossil Beds NMThe tiny gazelle-camel Stenomylus probably grazed in herds for protection from predators.

Agate Fossil Beds NM

Pliocene

Began 5 million years ago

Most life forms of the Pliocene Epoch would have been recognizable to us today. Many individual species were different, but distinguishing characteristics of various animal and plant groups were present. Evidence of wet meadows and of dry, open grassland environments has been found in the Pliocene. Toward the end of this epoch grasslands spread across much of North America, brought on by an ever cooler, ever drier climate. Horses and other hoofed mammals and the powerful, intelligent predators that preyed on them continued to prosper.

Mammut was a type of mastodon that migrated to North America in the Pliocene. In the early Pleistocene another elephant group called mammoths joined the mastodons. By the late Pleistocene mastodons and mammoths both became extinct, possibly because of climatic changes or hunting by early people.

Hagerman Fossil Beds NMWillow, alder, birch, and elm grew on the ancient river plains of the Pliocene. These same plants grow along streams and rivers today.

Hagerman Fossil Beds NMHorses such as an early zebra-like version of the modern horse were superbly adapted to life on the grassy plains.

Hagerman Fossil Beds NMPleistocene

Began 2 million years agoThe Pleistocene Epoch began with widespread migrations of mammals and ended with massive extinctions. It was also a time when glaciers repeatedly covered much of North America.

Known evidence of humans living in North America dates to about 12,000 years ago. In this relatively brief period we have had a profound effect on the plants and other animals here. Do we have a responsibility to try to limit our effects on other species, or are humans simply a natural agent of extinction?

Endangered species today include the loon, timber wolf, and Kemp's ridley sea turtle. The National Park Service is among the many public agencies and private organizations entrusted with helping to protect endangered plants and animals and to preserve the diversity of life throughout North America.

The Park Today

Fossil Butte National Monument is a semi-arid landscape of flat-topped buttes and ridges dominated by sagebrush, other desert shrubs, and grasses. Can you imagine that once this was a sub-tropical climate with a lake teeming with life? Look for evidence in the rocks around you.

Green River Formation

This formation of Fossil Lake sediments appears as layers of tan rock near the

top of Fossil Butte and surrounding ridges. Millions of fish and other fossils

are found in this 200- to 300-foot-thick formation. Other fossil-bearing

formations, laid down at different times or at different sites, also exist.

Wasatch Formation

The colorful red, pink, and purple formation, composed of river sediments,

preserves fossils of plants, primitive horses, a rhino-sized mammal called

Coryphodon, early primates, crocodiles, turtles, and lizards.

Planning Your Visit

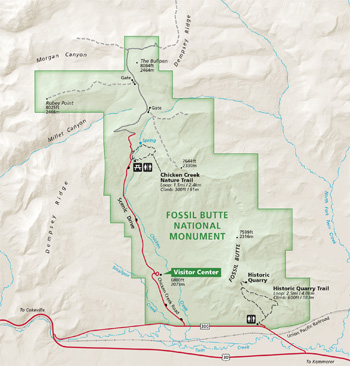

(click for larger map) |

Visitor Center Here you'll find information, over 200 fossil exhibits, and a bookstore. It is open daily except winter holidays; hours vary by season. Visit www.nps.gov/fobu.

Picnic Area A shaded picnic area has tables, fire grills, restrooms, and drinking water.

Historic Quarry Trail Strenuous: 2.5-mile loop. Climb Fossil Butte to a Green River Formation quarry worked in the 1960s. Exhibits describe the geology and history of collecting.

Chicken Creek Trail Moderate: 1.5-mile loop. This trail winds through sagebrush and an aspen grove. Exhibits tell the area's natural history.

Today's Natural World Watch for mule deer, pronghorn, elk, coyotes, and eagles in this land of sagebrush, aspen, willows, and pines. Wildflowers bloom seasonally.

Climate Temperatures range from 90s°F in summer to subfreezing in winter. High winds are common.

Accessibility Contact the park about accessible facilities. Service animals are welcome.

Food, Lodging, Services Find food, lodging, campgrounds, and services in Kemmerer. Bridger-Teton National Forest has camping.

Safety, Regulations Be alert. Remember, your safety is your responsibility. • Wear sturdy shoes and carry plenty of water when hiking. Be aware of elevation gains and steep downhill sections. • Protect yourself from the sun and insects. • Pets must be leashed and attended. • Build fires only in picnic grills. • Use caution on unpaved roads; they may be impassable if wet. • Do not feed or approach wildlife. • For firearms regulations see the park website. Emergencies: call 911.

Collecting Fossils—Past and Present

In 1856 geologist Dr. John Evans collected some of the first fossil fish from the Green River Formation. Paleontologist Dr. Joseph Leidy identified the fossils and gave them scientific names.

Not all early collectors were scientists. In the 1860s Union Pacific Railroad workers discovered the Petrified Fish Cut near the Green River station. In 1881 the Oregon Short Line Railroad was routed near Fossil Butte, improving access to the area.

Men, women, even families came here for what became a life's work. Robert Lee Craig spent 40 years (1897-1937) quarrying and preparing fossils for museums and private collections throughout the world. David C. Haddenham worked here into the 1960s.

Many of these fossils are exhibited today in museums across the United States, including Chicago's Field Museum, New York's American Museum of Natural History, Laramie's University of Wyoming Geological Museum, and Washington, D.C.'s Smithsonian Institution.

Collecting continues outside the park on private land and on state land leased by permit only. Rare finds on state land are given to the Wyoming Geological Survey for study.

Collecting within Fossil Butte National Monument is limited to special permit research projects that advance scientific understanding of Fossil Lake.

Stewardship

Fossil Butte National Monument was established to protect the fossils and geologic features within its boundary. Do not disturb or damage any fossil; If you find a fossil, leave it in place and report it to a ranger. All natural and historic features are protected by federal law.

Warning Non-permit removal of fossils violates the National Park Service Organic Act (16 U.S.C.) and 36CFR2.1 (a) (1) (iii). Violators will be prosecuted.

Source: NPS Brochure (2010)

|

Establishment Fossil Butte National Monument — October 23, 1972 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

An Exceptionally Preserved Specimen From the Green River Formation Elucidates Complex Phenotypic Evolution in Gruiformes and Charadriiformes (Grace Musser and Julia A. Clarke, extract from Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, Vol. 26, October 2020)

Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora, Fossil Butte National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2009-205 (Walter Fertig and Clay Kyte, May 2009)

Archeological Assessment, Fossil Butte National Monument (George M. Zeimens, 1976)

Combined phylogenetic analysis of a new North American fossil species confirms widespread Eocene distribution for stem rollers (Aves, Coracii) (Julia A. Clarke, Daniel T. Ksepka, N. Adam Smith and Mark A. Norell, extract from Zoological Journal, Vol. 157 Issue 3, November 2009)

Complete specimens of the Eocene testudinoid turtles Echmatemys and Hadrianus and the North American origin of tortoises (Asher J. Lichtig, Spencer G. Lucas and Steven E. Jasinski, extract from Fossil Record 7, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 82, 2021)

Dam Removal and Channel Restoration at Fossil Butte National Monument (Clayton R. Kyte, Vincent L. Santucci and Richard R. Ingles, Jr., extract from Wildland Hydrology, June/July 1999)

Eocene giant ants, Arctic intercontinental dispersal, and hyperthermals revisited: discovery of fossil Titanomyrma (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Formiciinae) in the cool uplands of British Columbia, Canada (S. Bruce Archibald, Rolf W. Mathewes and Arvid Aase, extract from The Canadian Entomologist, Vol. 155, 2023)

Foundation Document, Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming (March 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming (January 2017)

General Management Plan: Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming (March 1980)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Fossil Butte National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2012/587 (J. Graham, October 2012)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Fossil Butte National Monument

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Fossil Butte National Monument: 2008 Pilot Field Season NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2009/234 (Dustin W. Perkins and Rebecca Weissinger, July 2009)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Fossil Butte National Monument: Annual Report 2009 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2010/322 (Dustin W. Perkins, May 2010)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Fossil Butte National Monument: Field Seasons 2008-2012 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2013/751 (Dustin Perkins, May 2013)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Fossil Butte National Monument: 2014 Field Season NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCPN/NRR-2015/988 (Dustin W. Perkins, July 2015)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Fossil Butte National Monument: 2016 Field Season NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCPN/NRR-2017/1555 (Dustin W. Perkins, December 2017)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Fossil Butte National Monument: 2018 Field Season NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCPN/NRR-2019/1920 (Amy Washuta and Dustin W. Perkins, May 2019)

Junior and Senior Ranger, Fossil Butte National Monument (2011; for reference purposes only)

Museum Management Plan (Arvid Aase, Kent Bush, Linda Clement, Ann Elder, Lynn Marie Mitchell and Matthew Wilson, 2002)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Haddenham Cabin (Christine E. Maylath, Benjamin Brower and Kathy McKoy, February 23, 1995, revised May 10, 2000)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Fossil Butte National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/FOBU/NRR-2017/1394 (Kevin M. Benck, Kathy Allen, Andy J. Nandeau, Lonnie Meinke, Anna M. Davis, Sarah Gardner, Matt Randerson and Andy Robertson, February 2017)

Observations of Elk Movement Patterns on Fossil Butte National Monument (Edward M. Olexa, Suzanna C. Soileau and Leslie A. Allen, Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative, October 2014)

Preliminary Mammal Survey of Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming (Tim W. Clark, extract from Great Basin Naturalist, Vol. 37 No. 1, March 1977)

Paleogeography and Paleoenvironments of the Lower Unit, Fossil Butte Member, Eocene Green River Formation, Southwestern Wyoming (©Roberto E. Biaggi, Master's Thesis Loma Linda University, June 1989)

Paleontology of the Green River Formation, with a Review of the Fish Fauna The Geological Survey of Wyoming Bulletin 63 (Lance Grande, 1984, 2nd ed.)

Park Newspaper (Fossil Butte Shore Lines): Vol. 1 (Date Unknown)

Past ecosystems drive the evolution of the early diverged Symphyta (Hymenoptera: Xyelidae) since the earliest Eocene (Corentin Jouault, Arvid Aase and André Nel, extract from Fossil Record, Vol. 24, 2021)

Phylogenetic relationships of Icaronycteris, Archaeonycteris, Hassianycteris, and Palaeochiropteryx to extant bat lineages, with comments on the evolution of echolocation and foraging strategies in Microchiroptera (Nancy B. Simmons and Jonathan H. Geisler, Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History No. 235, 1998)

Preliminary Report of the U.S. Geological Survey of Wyoming and Portions of Contiguous Territories (F.V. Hayden, 1872)

Proposed Fossil Butte National Monument (August 1964)

Railroads, Tourism and Fossils Park Paleontology Vol. 6 No. 3 (Vincent L. Santucci, Fall-Winter 2002)

Soil Survey of Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming (2015)

Statement for Management — Fossil Butte National Monument: September 1985 • March 1988 • March 1991

The anatomy and taxonomy of the exquisitely preserved Green River Formation (early Eocene) lithornithids (Aves) and the relationships of Lithornithidae (Sterling J. Nesbitt and Julia A. Clarke, Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, no. 406, 2016)

The Geologic History of Fossil Butte National Monument and Fossil Basin (HTML edition) National Park Service Occasional Paper No. 3 (Paul O. McGrew and Michael Casilliano, 1975)

The oldest known bat skeletons and their implications for Eocene chiropteran diversification (Tim B. Rietbergen, Lars W. van den Hoek Ostende, Arvid Aase, Matthew F. Jones, Edward D. Medeiros and Nancy B. Simmons, extract from PLoS ONE, Vol. 18 No. 4, April 12, 2023)

The second North American fossil horntail wood-wasp (Hymenoptera: Siricidae), from the early Eocene Green River Formation (Corentin Jouault, Arvid Aase and André Nel, extract from Zootaxa, Vol. 4999 No. 4 July 13, 2021)

Vascular Plant Species Checklist and Rare Plants of Fossil Butte National Monument (Walter Fertig, October 9, 2000)

Vascular Plant Species Discoveries in the Northern Colorado Plateau Network: Update for 2008-2011 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2012/582 (Walter Fertig, Sarah Topp, Mary Moran, Terri Hildebrand, Jeff Ott and Derrick Zobell, May 2012)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report, Fossil Butte National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2010/319 (Beverly Friesen, Steve Blauer, Keith Landgraf, Jim Von Loh, Janet Coles, Keith Schulz, Amy Tendick, Aneth Wright, Gery Wakefield and Angela Evenden, May 2010)

fobu/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025