|

Fort Davis

A Special Place, A Sacred Trust: Preserving the Fort Davis Story |

|

Chapter Seven:

Refining the Message, Defending the Resources: The Quest for Institutional Support, 1980-1996

On a crisp fall morning in November 1995, the buildings and grounds of Fort Davis National Historic Site stood as empty as when the post was abandoned a century before. The eery silence occurred because of the failure of the U.S. Congress and the President to agree on a budget for the federal government. For the third time in 15 years, park personnel were "furloughed," or sent home indefinitely because their parent agency, the Interior department, had received no congressional appropriation with which to operate. Thus the park staff could not fulfill the mission mandated by Congress 35 years earlier to preserve the past for the future, and to instruct the visiting public about the heritage and tradition of the Davis Mountains.

It was fitting that the restored example of the "finest frontier military post in the Southwest" had no visitors or staff in the week before Thanksgiving, as the last two decades of the twentieth century bore little resemblance to Fort Davis' first 20 years of existence. A more conservative political climate under the presidential administrations of Ronald Reagan, George Bush, and Bill Clinton reduced spending overall to public agencies. This meant that parks like Fort Davis would receive less attention and funding, especially as Congress continued to establish new units of the park service. From personnel to preservation to interpretive services, the staff and management of Fort Davis spent much of the latter part of the century consolidating the gains of the 1960s and 1970s, while trying to find more creative means to advance the cause of history in the far Southwest. [1]

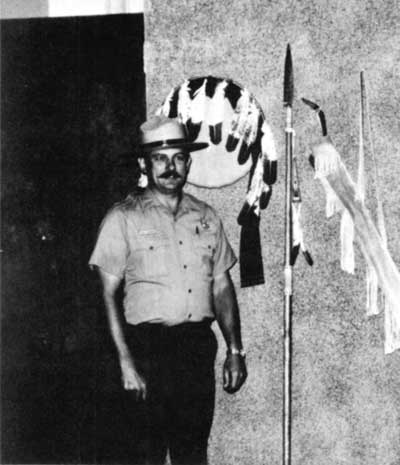

The four superintendents that managed Fort Davis in its third and fourth decades of existence all faced the challenge of enhancing the richness and variety of historic resources that the park service had inherited and preserved. From Doug McChristian (1980-1986) to Steve Miller (1986-1988) to Kevin Cheri (1988- 1992) to Jerry Yarbrough (1992-present), the park's directors and staff knew that they would not soon return to the days of 1960s restoration, or the excitement of creating the living history programs of the 1970s. Perusal of their correspondence and reports, along with oral interviews, indicates the maturing process of Fort Davis as a park service unit, along with the need for staff and managers alike to be ever more thoughtful in meeting the needs of visitors and guarding the historical tradition of the old frontier post. This process began in the spring of 1980, when former supervisory ranger Doug McChristian returned to manage the park. In a 1994 interview, McChristian remembered how he wished to "influence the history of an area," and how concerned he had been as a special assistant in the Southwest Regional Office about the "decline of quality in the living history program." His first objective became the revitalization of the work that he and Mary Williams had undertaken in the early 1970s to bring the past to life, with better maintenance of the ruins and their foundations as allied priorities. [2]

|

|

Figure 42. Superintendent Doug McChristian

(1985). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

McChristian's personnel, like many public officials in the early 1980s, found it difficult to accept the political rhetoric ushered in by the so—called "Reagan Revolution." The conservative Republican had swept to victory in the 1980 election by promising to "get government off the backs of the American people," and suggesting that those employed in public service did not measure up to the standards of the private sector. Reagan's promise to reduce federal spending for domestic programs, and expand dramatically the appropriations for the nation's armed forces, marked a significant shift in emphasis from the more generous spending habits of the Democrats in the White House and Congress. Compounding this was Reagan's choice as Interior secretary James Watt, an arch-conservative lawyer from Wyoming whose Mountain States Legal Foundation had championed the causes of the "Sagebrush Rebellion;" a 1970s protest movement originating in the public land states of the arid West, with citizens outraged at the regulatory power of federal officials and their perceived insensitivity towards the property rights of individual landowners. [3]

Even before the inauguration of Ronald Reagan in January 1981, Supervisory Park Ranger James A. Blackburn had to issue a memorandum to the staff entitled, "Support for Public Policy." He had noticed that "certain remarks made by employees in the presence of visitors have not thoroughly supported public policy of the United States Government." Conceding that his staff had the right of free speech, Blackburn nonetheless wanted no one "making remarks that might lead a visitor or other employee to feel that we do not care for the job or policy of our government (our employer)." The supervisory ranger recognized "the austerity of our present financial posture;" a condition that he agreed had "resulted in curtailed programs and reduced visitor services in the area of interpretation." Yet the Fort Davis staff "have not reduced our visitor services when it comes to quality -- if anything, we are constantly improving quality." Blackburn asked his colleagues "to provide our visitors with a positive outlook," and "to curtail negativism." If the staff would "all take a look at ourselves," they would realize that "we all experience some dissatisfaction with the restraints imposed upon us." Yet "we can gain public support," said the ranger, "by portraying to our visitors a can-do attitude; one that says we are aware of certain limitations in funding and personnel," and one that would keep "this dissatisfaction from showing to our visitors." [4]

The superintendent had to acknowledge that the ambition of the NPS in the 1960s had given way to a more conservative time. In the 1970s, the Park Service had refurnished several buildings at Fort Davis, including an officer's quarters, a kitchen and servants' quarters, and the post commissary. Yet these facilities required personnel to interpret their story to the visiting public, and historians to research that story. McChristian soon realized upon his return to Fort Davis that one reason for the perceived "decline" in living history was the reduction in staff in the late 1970s. In a memorandum to the regional office in March 1981, the superintendent provided a table of hiring trends since 1975. In the division of interpretation, for example, there had been ten seasonals that year, along with two permanent staff and three "Cooperative Education" employees. By 1980 the Park Service, responding to declines in congressional support, reduced the number of workers at the park. The regional office also lowered the pay grades for new hires; a pattern that McChristian called "a false economy because it naturally tended to lower the quality of programs and caused some activities to be canceled entirely." A second indicator of the fiscal constraints of the 1970s was the requirement by Congress that the NPS absorb the "Classified Pay Increase" (CPI) in each park's operating budget. Rampant inflation in the years after the conflict in Vietnam had driven consumer prices and wages upward in a seemingly endless spiral, as much a function of the rise in energy prices as in the explosion of government spending criticized by conservative politicians. McChristian would thus have to find money in his allocation from Santa Fe to cover 60 percent of the staffs pay raises; a situation that he called "the single most [important] factor adversely affecting the park's funding." This meant no hiring of seasonals for the summer of 1981, delays in standard maintenance procedures (such as mowing the grounds, painting the trim on buildings, clearing of nature trails, etc.). [5]

Since a commitment to public service was a hallmark of the NPS, and because Fort Davis represented a signal achievement in living history interpretation, McChristian decided to press forward with as thorough a program of storytelling, reenactments, and scholarly research as his budget limitations allowed. In May 1980, he provided his staff with a clear explanation of his principles and goals. "I believe that we have an obligation to insure that what [the visitors] are seeing, touching, tasting, and so forth," said the superintendent, "is a worthy substitute for the real thing." He challenged the idea that "visitors won't know the difference anyway" by suggesting that it was "unprofessional" and misleading to the public to denigrate the personal nature of living history. "Visitors look to us as the experts," said McChristian, "and depend upon us to be correct." He extended the quest for "authenticity" to the daily dress of his staff "from the skin out," mindful that wool undergarments were "often uncomfortable at first to a 20th Century person.' Nonetheless, accuracy in detail meant "interpreting life by their standards [the nineteenth-century frontier]," so that the staff could dramatize to visitors "the contrasts between the quality of life then and now, changes in style and custom, health factors, and the uses of energy as contrasted with the present day." [6]

Interpreting the authenticity of Fort Davis through living history led McChristian to develop plans to study other aspects of the park's natural and cultural resources. He asked Dr. James T. Nelson, professor of range animal science at Sul Ross State University, to undertake a vegetation study "to recreate and maintain the natural features" that "accurately reflect the historic scene of the late 19th century." The superintendent needed base maps of vegetation such as "grasses, trees, shrubs, and cacti." He also wanted to know of the "various vegetative zones," the plant life "now present but exotic to the area," and those plants "not present but.. . probably a part of the historic scene." Yet Fort Davis also faced intrusion into the serenity of the park with the increase of Air Force flight testing in the Davis Mountains. Superintendent McChristian had to write in February 1981 to Colonel Harold Dortch, commander of Tactical Training at Holloman Air Force Base (HAFB), to complain as his predecessors had of the "sonic booms" occurring as part of the overflights of high-speed aircraft. "I hope that you share our concern for preserving our nation's military history," said McChristian, since "a public that has the opportunity of understanding our military's role and traditions are more likely to be supportive of its actions today." The Air Force, however, did not respond to the superintendent's entreaties, leading McChristian in November 1981 to complain to regional officials: "Apparently, the Air Force would like me to believe that I am imagining things." McChristian and his staff contended that "when one hears a thunderbolt-like crack from a cloudless sky and feels the entire building tremble, he can assume either an F-15 has overflown the area or that the Almighty is upset with the National Park Service." The staff thus had no choice but to record the time and date of the sonic booms, since "until we have hard evidence upon which to base our complaint, we cannot present a convincing case for claiming possible damage to the structures at Fort Davis." [7]

A critical factor for the staff and management of the park was the continued imbalance of interpretation of the black experience at the post. Prompted by the NPS' inquiry about Fort Davis' "Minority Interpretation Action Plan," the staff discussed in 1980 what Mary Williams described as "the positive and negative aspects of our interpretive programs as they effect and are affected by minority cultures." As part of Doug McChristian's call for more authenticity in telling the Fort Davis story, the staff reviewed its exhibits, collections, publications, and interpretive presentations. They discovered, for example, that two slides in the museum audio-video program that supposedly depicted black troopers of the 9th Cavalry "actually were of white soldiers." The noted Southwestern artist Rogers Aston donated to Fort Davis "two beautiful historically accurate bronzes - one of an Apache Indian and the other of a Buffalo Soldier." Mary Williams acknowledged that these statues replaced "a large copy of a [Frederick] Remington sketch of an Apache and a Buffalo Soldier" because the original, "like some of Remington's other sketches of black men, . . . depicted the Buffalo Soldier as a very physically unattractive person." Fort Davis also redesigned the "shared officers' quarters" to represent the rooms of Lieutenant Henry Flipper, and also examined the possibility of commemorating in 1981 the centennial of Flipper's court martial. Less successful were the staffs efforts to hire a black seasonal. One young man from Howard University in Washington, DC, wrote that he could not afford to move to Fort Davis, while a second student from Tuskegee Institute in Alabama reported that "because of personal problems he could not accept the appointment." Fort Davis then turned to Sul Ross for help, but "no qualified black students have expressed any interest in the program." [8]

Given the ongoing problems of operating an historic site with limited staffing, Doug McChristian decided in December 1981 to speak forthrightly about the "core mission declaration" requested by the Southwest Region. He oversaw a park unit with some 120 buildings and ruins, not to mention "an unknown number of structure sites, especially with regard to the First Fort area, [that] remain to be located precisely within the 460-acre site." The superintendent also commented that "by the very nature of the historic fabric, largely adobe along with wood and stone, the primary resource is extremely fragile and subject to deterioration from natural and human causes." McChristian anticipated that Fort Davis would welcome "approximately 95,000 visitors during the target year [1982]," and suggested that he and his staff would keep open as many facilities as possible without new personnel. This meant that little if any work could be conducted on historical research or artifact cataloguing, which McChristian estimated at 30,000 items. [9]

The regional office's concern over Fort Davis' ability to meet the demands of visitors prompted a visit to the park in August 1981 by Joseph Sanchez, chief of the SWR division of interpretation and visitor services. Sanchez had worked for one month at the park in early 1980 as its acting superintendent, receiving high praise from the staff for his "keen interest in better cultural resource management and historical accuracy," the latter including his advice on "the revision of the park brochure so that it better reflects the role of the Black troops at Fort Davis." Sanchez, who in the late 1980s would direct the NPS-funded Spanish Colonial Research Center at the University of New Mexico, noted upon his arrival at the park that "Fort Davis is exceptionally and professionally run." He credited the staff with being "especially attentive to visitors," and saw them presenting "a positive image for the National Park Service." Sanchez reported that better access to the refurbished quarters could be provided to the handicapped (a situation that Superintendent McChristian agreed to correct), and then closed by commenting upon the problems of the location of the visitors center in the barracks building north of the administrative offices. "Because the administrative center is the building visitors approach first and often enter," said Sanchez, "it occurs to park management that the circulation pattern to the museum is illogical and confusing." The staff discussed with him the reversal of facilities "to provide a safe emergency exit for visitors to the museum which currently has no rear exit." In addition, "the electrical system in the museum is near the entry way and itself would become affected . . . if something would go wrong." Reversing the order of visitor and administrative facilities would obviate the phenomenon, said Sanchez, where "confused visitors approach the Superintendent's office first." [10]

One feature of Fort Davis' interpretive work that contributed to the glowing report of Joseph Sanchez was the dedication service for the Commanding Officer's Quarters. Some 400 guests arrived at the park on the morning of May 16, 1981, to join with NPS personnel from the Southwest Region, the Denver Service Center, and the Harpers Ferry Center. The COQ had been a favorite of local residents; a tie strengthened by the presence in the area of two of Benjamin Grierson's sons in the community for many years after the closing of the fort. The public speakers included Bruce Dinges, acting editor of the publication, Arizona and the West, whose specialty was the life of General Grierson, and Robert M. Utley, recently retired as assistant NPS director for park historic preservation (as well as deputy executive director for the President's Advisory Council on Historic Preservation). Utley offered the keynote address on "Fort Davis' role in westward expansion;" a subject that he had championed two decades earlier in the initiative to create the park. [11]

Doug McChristian's first two years as Fort Davis' superintendent had a salutary effect upon visitation, as patrons appreciated the ambition of the park staff and its willingness to overcome obstacles. McChristian's second year saw an 11 percent increase in visitor totals, which he attributed to the "stabilization of gasoline prices, increased attention on the Davis Mountains area due to articles in leisure magazines, and increase in population centers such as Odessa and Midland, which are experiencing rapid growth as oil producing centers." This volume of visitors also prompted record sales in the SPMA book exhibit, which increased 49 percent over 1980. In return, the Tucson-based SPMA donated over $7,000 for such items as library materials, "a wayside exhibit for the chapel to include information on the Court Martial of Lieutenant Henry O. Flipper," a "five-day training course for interpretation of the Indian Wars enlisted soldier," and to "improve women's living history attire for the site's interpretive program." Special visitation included "ten members of the State of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department," who attended a one-day seminar on living history interpretation. Superintendent McChristian also recognized the growing contribution of the park's volunteers (23), who donated over 1,000 hours as tour guides, living history interpreters at the historic buildings, and as aides in the library and photograph collection. [12]

Emphasis on the story of Fort Davis also drew the attention of scholars, donors, and public and private agencies devoted to the promotion of tourism and travel in the region. Superintendent McChristian became intrigued at the work of Dr. Robert F. Newkirk of the Cooperative Programs Study Unit in the Department of Recreation and Parks at Texas A&M University. Newkirk sought potential research projects for his students at the College Station campus, and the Fort Davis staff was only too eager to oblige. Mary Williams compiled a list of topics that included the history of the Overland Trail, the development of the town of Fort Davis, an administrative history of the park, work on the sub-posts around Fort Davis, and oral histories of descendants of military personnel stationed at the fort. McChristian himself expressed to Newkirk the need for "a historical base map covering the 460-acre site." "Considering the current low emphasis on studies," said the superintendent, "it will probably be some time before funding is available for this project." McChristian also wondered about Newkirk's interest in "a good military and structural history of the First Fort Davis." The superintendent's inquiries of the Texas A&M professor were also stimulated by the suggestion of the regional office in October 1982 that history departments might have graduate students willing to conduct the research and writing that the park service could no longer support. "Perhaps the [regional] Division of History could act as a 'clearing house' for such requests," said McChristian, as "most history related studies seem to get low priorities these days." [13]

The need for this research activity was apparent to Charles McCurdy, SWR's chief of interpretation and visitor services, who came to Fort Davis in July 1982 on the regional office's annual inspection of the park's historical work. McCurdy, who had last spent time at Fort Davis in November 1980, walked with the superintendent and his interpretive chief, John Sutton, through the refurnished COQ, the post commissary, and the hospital. "The park staff," said McCurdy, "has done a nice job in making the hospital accessible through means of a catwalk passing through it and interpreting it by means of small easels that reveal facets of the world of the hospital in the late 1880's." "Park visitors seem to enjoy themselves at the Fort," the regional official noted; a condition that he attributed to the staffs "good training and good reading." Earning special mention from McCurdy was the portrayal of the soldiers, who "made a nice counterpoint to the refurnished buildings that draw so much interest." He did express concern that the 30,000 artifacts, many of which had been unearthed in the 1969 archeological survey, "remain uncatalogued and many need conservation treatment." Superintendent McChristian informed McCurdy that he would convert a maintenance position to a museum technician who could "do maintenance-type chores." Another issue for the regional interpretive chief was that "the [museum] exhibits are due for a change." Robert Utley's design, which had charmed Lady Bird Johnson at the 1966 dedication, now seemed in the 1980s to "convey more of a story about the development of the Fort than the purpose of the Fort and events on the Indian campaign." McCurdy sympathized with the constraints placed upon the staff, and suggested that the regional office provide Fort Davis with "career interpreter training [in] curatorial methods, and interpretive operations management." He could not resist closing with admiration for the location of the park, noting that "the area looked well cared for," and that "altogether, it's a nice experience to spend the day there and see a well run operation." [14]

One comment made by McCurdy that the park took to heart was his call for an "Interpretive Prospectus," which John Sutton drafted in November 1982. Superintendent McChristian asked Edwin C. Bearss, chief historian for the park service, to review Sutton's ideas. Bearss turned to a former park historian at Fort Davis, Ben Levy, then senior historian on Bearss' staff. Levy's remarks, however, left McChristian confused about their endeavors to define the park's standing in the NPS. Levy commended Sutton for his "well intentioned" ideas, but reminded the park staff that "these issues . . . need to be addressed against the backdrop of history and the reality of policies and costs." The NPS senior historian criticized what he called "the inexorable development from stabilization through rehab [rehabilitation], restoration, reconstruction, and refurnishing even though more limited objectives were the stated intention originally." Levy disliked the fact that "stabilization and restoration" had become "a cloak for more expansive ends," and he stated: "A halt should be called once and for all to the refurnishing objective." He called it "contrary to the policy and the exception that it is needed for interpretive purposes is not justified." As for the vaunted efforts to refurnish the officers' quarters at Fort Davis, Levy saw these as "essentially conjectural." "There are already questionable furnishings installed" at the park, and others concurred in his judgment. "I say let's call a halt and go back to the original intention of preserving the fort essentially through minimum protective measures," wrote Levy. The discussion about the visitor center/administrative offices location prompted Levy to remark: "I too, recognized the foolishness of placing the Offices in the south end of HB-20 and the Museum in the north end." At the same time, Levy disagreed with park staff that the "wordiness" of the museum's label copy alienated visitors. "My observation," reported the senior NPS historian, "was that the adults found every word interesting and followed the story line in an unhurried fashion." He found more irritating the park service's recent shift to "so-called open museums [a reference to the technique of displaying artifacts in open space, rather than in some pattern for visitors to follow]," with their "unacceptable visitor confusion." Levy instead called upon Fort Davis to "refurbish the existing museum," move it to the south wing, and "utilize another area for the innovative display." [15]

When Superintendent McChristian contemplated Fort Davis' achievements for 1982, high on his list were ideas for meeting the criticisms of Ben Levy and others about interpretive programs and facility enhancement. He took great pride in the fact that the park had hired its first black seasonal, James Montgomery of nearby Pecos. Montgomery majored in social studies at Sul Ross, and offered Fort Davis someone who could "interpret to park visitors the lifestyles and history of Black soldiers," either through "a barracks scene or a cavalry program with horse and Cavalry field equipment." More space was devoted in the post hospital to telling the story of health care on the nineteenth-century frontier. This helped McChristian when he brought to the park in May some 31 interpreters from around the region to participate in his Indian Wars camp of instruction. Attendees came from several NPS military parks, the Texas state parks system (Fort Richardson), the New Mexico state parks of Forts Selden and Sumner, and the Wyoming state parks system (Fort Bridger). The Institute of Texan Cultures in San Antonio also sent personnel, as did Fort Concho in San Angelo. McChristian made special mention of the participation of Fort Davis staff in the April centennial parade of the community of Alpine, wherein three staff members and two volunteers rode horseback the 35 miles from the park to the Brewster County seat "as if they were in the field with the frontier Army." Six staff members and one volunteer also traveled in June to San Angelo to join the annual Fort Concho fiesta. All these activities demonstrated the commitment of Fort Davis to keeping the story of the western military alive, and contributed to another good year of attendance, with a five percent increase (75,056). In like manner, these visitors patronized the SPMA book exhibit handsomely, resulting in an 18 percent rise in book sales. The only cautionary note about visitation in 1982 was the decline of Mexican visitors, which McChristian believed resulted from "the devaluation of the Mexican peso." [16]

By 1983, the park staff had realized, as had the NPS in general, that there would be little new money for continued expansion of the legislative mandate that Congress had given to Fort Davis. The national economy had slumped in the winter of 1982-1983 to its lowest point since World War II, and unemployment stood at its highest level since the depths of the Great Depression (nearly 11 percent). Thus the park service began serious discussions about solicitation of private funds to improve the quality of NPS programs and units. Fort Davis already had a private organization that had assisted in the creation of the park two decades earlier (the Fort Davis Historical Society). Unfortunately, as Doug McChristian would recall in 1994, the society "had become more social than advocates for Fort Davis." The group was aging, and few younger people joined. Thus McChristian decided in 1983 to create a new entity, the "Friends of Fort Davis." Their first task, the superintendent determined, would be to seek private funds to restore HB-2 1, the barracks building to the north of the museum/visitors center. McChristian had an estimate made in October 1982 of the cost of restoration (($176,000) and refurnishing ($30,000-40,000). He predicted that such an endeavor would rank low in priority with the NPS, but that a private campaign would "allow the people of West Texas and other interested parties a chance to have a personal hand in developing Fort Davis." McChristian further predicted in January 1983 that such a foundation "could very well turn into a long-term association that could provide financial support for a variety of activities at the Site, particularly by providing financial aid to continue living history programs here." [17]

The irony of McChristian's decision was that the quest for private funding of a public historic site energized the park in ways not seen since the early 1960s. By selecting the enlisted men's barracks as the target of rehabilitation, and by embracing the story of black troopers as never before, Fort Davis once again gained national attention for its innovative ideas and methods of interpretation. This in turn contributed to new monies (both public and private) for restoration and maintenance; all to be linked to the tradition of park service standards and procedures for hiring, design and construction, and visitor services. The synergy of staff commitment, funding, scholarly attention, and visitors' patronage, joined to give the park a new lease on life and validate the efforts of the park planners to make Fort Davis a showcase of western military history.

|

|

Figure 43. Restored Enlisted Men's Barracks

(Late 1980s). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

|

|

Figure 44. Interior of estored Enlisted

Men's Barracks (ate 1980). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

The first step in moving the park towards McChristian's goal was selection of members of the "Friends" group. The superintendent realized that he needed a mixture of local activists and nationally prominent figures to lend legitimacy and lustre to the pursuits of the board. Local residents who accepted McChristian's offer of membership were rancher Pansy Espy, descendant of one of the first ranching families in the Davis Mountains (who also agreed to serve as treasurer); Donna Smith of Ft. Davis; Thomas Bruner of Midland, vice president and trust officer of that community's Texas American Bank; and Bob Dillard, editor of the Alpine Avalanche and the first president of the board. Joining them from other parts of the country were Dr. John Langellier, curator of the Army Museum at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; Sara D. Jackson, employee of the National Historic Preservation and Records Commission in Washington (a branch of the National Archives and Records Administration [NARA]); William Leckie, professor of history at the University of Toledo and the author of Buffalo Soldiers; and Robert Utley, now a free-lance writer of historical works living in Santa Fe with his wife, Southwest Region chief historian Melody Webb. Superintendent McChristian informed each board member from out of town that they should expect to meet at least once per year in Fort Davis, and that they would be asked to identify pertinent funding sources for a $250,000 restoration and refurnishing project. An example of the scope of the work expected from the board came in McChristian's letter to Thomas Bruner, wherein he informed the Midland banker that the barracks project had been part of the original master plan, drafted 20 years earlier. He also told Bruner that "quite honestly, Fort Davis offers the only opportunity for the black Regulars to be represented in the National Park System." Other frontier posts were preserved within the NPS, but McChristian made clear that the racial character of military service at Fort Davis would be central to any proposal to private funding agencies. [18]

Before the board came to Fort Davis for their first gathering, the superintendent asked the Denver Service Center to review the original plans for barracks restoration. A DSC staff member came to the post on June 9,1983, and offered both technical advice and guidance on fundraising. In a letter to the board members soon thereafter, McChristian said that "by using private funds [the NPS] can drastically reduce the usual amount of overhead and can reduce the amount even further depending on how much of the preparatory work we might accomplish with the park maintenance staff, day labor, volunteers, and by contribution." Thus the 1978 estimate that restoration would require $176,900 (without furnishings) "may come out closer to $100,000." McChristian himself calculated the furnishing budget to be some $25,000, and had initiated conversations with donors and replica manufacturers to receive special gifts and rates because of the nature of the barracks project. The superintendent wanted the board to meet as soon as possible, perhaps during the September meeting at Fort Davis of the Order of the Indian Wars, to which several board members belonged. Among his reasons for the accelerated pace of work were the need to establish tax-exempt status, to plan strategy, and to avoid the inevitable delays (which McChristian called the "ever-present red tape") connected to "complex government accounting procedures." [19]

To further the efforts of the Friends board, McChristian and the park staff in the spring and summer of 1983 pursued other avenues of support for the historical mission of Fort Davis. Most prominent among these was the release of a contract for $392,000 to Roof Builders, Inc., of El Paso to reshingle 20 of the historic structures, redeck all porches on Officers Row, and other work on the walkways, landings and porches of the row. This money came from the "Park Rehabilitation and Improvement Program," (PRIP), which also permitted Fort Davis to hire a temporary carpenter to assist the maintenance staff. In the area of historic interpretation, the park installed a new "photo-metal" wayside exhibit at the post chapel to "interpret the multifunctional chapel as well as commemorate the court-martial trial of 2nd Lieutenant Henry 0. Flipper." Funds for this activity came from the SPMA. A third area of interest that summer for the staff was planning for a new "park headquarters." They wanted "a more formal reception area," "separate sound-proofed offices for key personnel," "a staff room large enough to accommodate meetings and training activities," "a larger and more isolated library," "a separate, yet convenient, room for xeroxing and office supplies," and "an office for the maintenance foreman." Finally, the park began to address the backlog of unaccessioned artifacts, which would increase dramatically once excavation began on the barracks, by hiring as a museum technician Judith M. Hitzman, most recently a staff member of the NPS' Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site in Montana. McChristian directed Hitzman to bring order to the cataloguing process, and to train cooperative education students for collections work, as well as to instruct volunteers in "historic housekeeping techniques." [20]

When the Friends group assembled at the park on September 14, 1983, they faced both a challenge and an opportunity. In order to commence their own task of fundraising, the board needed specifications and plans drawn by the Denver Service Center, and quickly. Unfortunately, the park could commit no funds to this endeavor. Thus Superintendent McChristian suggested that they raise the sum of $10,000 immediately to pay the DSC to send staff to Fort Davis and prepare the planning documents. The board authorized the solicitation of memberships (at $2 per year or $25 for life members), while the staff placed a donation box in the visitors center. By year's end the Friends had collected some $4,000 toward the DSC planning. McChristian asked his staff to conduct as much maintenance work at the barracks as possible to reduce the length of time and the amount of money needed to begin rehabilitation. The most critical feature of the early phase of barracks work, however, was the use of an archeological consultant to identify the existing historic resources. The DSC had no one available at short notice to send to Fort Davis, but suggested that McChristian seek a contractor to perform the survey work. Fortunately there resided in the town of Fort Davis a married couple, Ellen and Dr. J. Charles Kelley, who had moved to the Davis Mountains after retiring from Southern Illinois University (she as curator of collections for the university museum for 23 years; he as a professor of archeology for 25 years). Each summer the Kelleys had maintained a home in the Davis Mountains, and conducted archeological digs in the Big Bend area and in Mexico. By agreeing to oversee the survey without compensation, and by utilizing a team of volunteers "Junior Historians" from Alpine High School, the Kelleys managed to complete the digging within the space of three months in the winter and spring of 1984, saving the Friends and the park some $20,000 in the process. [21]

Whether it was by coincidence or by design, the escalating pace of work at Fort Davis, especially its emphasis on the story of the black soldier, brought to the park in November 1983 William "Bill" Gwaltney as park technician (with primary duties as a ranger and law enforcement officer). Gwaltney was one of the few black NPS employees with an interest in the history of the West; a circumstance that he attributed in a 1994 interview to his family's heritage of service in the armed forces (including a grandfather who had been one of the famed "Buffalo Soldiers" of the late nineteenth-century). Gwaltney would spend three years at Fort Davis, in which time the park generated much information and publicity about the place of black troopers in the service of their country. When he first arrived in Fort Davis, Gwaltney soon recognized both the "invisibility" of the black soldier in the minds of community members, as well as the ambivalence of the staff towards interpreting the black experience with white personnel. Gwaltney decided to "normalize the dialogue" about black soldiers, realizing that to most visitors the park symbolized what he called "Texas nationalism" rather than the competing forces of discrimination and opportunity that military service implied. [22]

Throughout the spring and summer of 1984, the Fort Davis team of Bill Gwaltney, Mary Williams, Doug McChristian, and supervisory ranger John Sutton addressed all manner of historical and cultural issues at the park. The superintendent prepared a furnishings plan for the barracks, and coordinated the fundraising strategies of the Friends board. McChristian also learned of new initiatives in documentary filmmaking about the Buffalo Soldiers, especially one promoted by WHNM, the public television station of predominantly black Howard University in Washington, D.C.

|

|

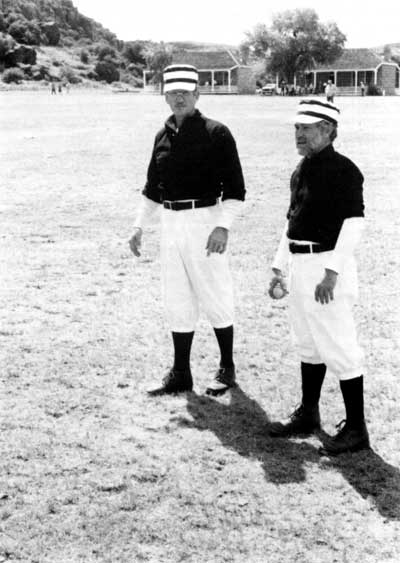

Figure 45. Park Technician William "Bill"

Gwaltney (1980s). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

The park wished to update its 1960s-vintage orientation film to reflect the sensibilities of the civil rights era, and WHNM's "The Different Drummer" seemed a logical choice to replace the existing video. Mary Williams continued to research and develop women's history activities for the park, and Bill Gwaltney approached a series of scholarly and popular journals and magazines to interest them in the black soldier story. Gwaltney and McChristian also corresponded with other NPS sites with black history themes to encourage them to incorporate western history in their slide shows and displays on black America. [23]

These initiatives led McChristian, Gwaltney and the Friends group to focus more closely on promotion of the black perspective on Fort Davis history in their applications to private funding agencies for the barracks restoration project. The most noteworthy of these efforts came with the Meadows Foundation of Dallas. Pansy Espy remembered how the Friends sat down with directories of philanthropic organizations nationwide, and members Bob Dillard, Tom Bruner, and herself wrote over 130 applications. The Meadows Foundation, created in 1948 by Algur H. Meadows, the founder of the General American Oil Company of Texas, had never worked before with a federal agency on a grant proposal, but they found fascinating the strength of the black heritage at Fort Davis. McChristian, Gwaltney, and Sara Jackson of the National Archives thus travelled to Dallas in July 1984 to plead their case to the Meadows board, asking for $50,000 to defray the expenses of the barracks restoration. The seriousness of the Friends' message, and the reputation of their board nationally, led the Meadows Foundation to grant their request in October of that year. The $50,000, plus some $10,500 raised that summer by the Friends at the park, helped attract other monies as well: $3,000 from the Burkitt Foundation, $2,500 from donations at the visitors center, and $35,000 in "in-kind" (non-cash) services provided by the Southwest Region's "Cultural Resources Preservation Crew." One distinctive feature of fundraising was the institution of the Labor Day weekend "Barracks Restoration Festival," which in 1984 contributed $6,000 to the private donations to the project. Overall, by January 1985, Superintendent McChristian could claim that the Friends had raised $101,000 (the total cost of barracks restoration), with the furnishings plan next for the Friends to consider. [24]

While it would have been tempting to focus all of the park's energies on the barracks restoration project, Superintendent McChristian also faced issues of management that were no less crucial to the success of his staff. Early in 1984, the superintendent asked the Southwest Region to assist him in securing funding for an historic base map and "General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan [GMP/DCP]." This latter request emanated from news that the Denver Service Center had prepared "Historic Preservation Guides" for the park that McChristian believed could serve as "the foundation of a Maintenance Management Program," which in turn would "better enable management to plan and program cyclic maintenance needs." The superintendent continued to monitor claims that Holloman AFB wished to increase its supersonic flights over the Valentine area. McChristian reported to his superiors in Santa Fe that "the environmental impact statement issued by the Air Force was hotly contested by local groups, particularly the Council for the Preservation of the Last Frontier."

Encroachments upon the air space of the park were matched by fears that Mrs. J.A. Hanchey of Lake Charles, Louisiana, would sell her tract of land adjacent to the site's south boundary, near the base of Sleeping Lion Mountain. McChristian noted that "various superintendents, past and present, have expressed concern over the development potential of this tract." The property, less than five acres in all, "lies only a few yards from the parking lot and within a few feet of the site of the Post Trader's Store," "virtually on the front doorstep of the Site." McChristian entered into conversations with Mrs. Hanchey, whom he reported "concurs completely with management's concerns and said that she would be more than happy to work with the Service in any way to see the boundary protected." [25]

These latter two issues dramatized the realities of management at Fort Davis, especially its inability to halt the intrusions of the military or the private sector because of the limited financial resources of the NPS, and the power of the armed forces in the years of the Reagan-era defense buildup. In early 1985, the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) announced that it would, at the insistence of U.S. Representative Ronald Coleman, an El Paso Democrat, and U.S. Senator Jeff Bingaman, a New Mexico Democrat, investigate the report that the environmental impact statement released by Holloman AFB would include as many as 750 sonic booms per month over the Davis Mountains. New Mexicans were outraged that the Air Force also had targeted the Gila Wilderness area known as the "Reserve MOA [Military Operations Area]," and that both the Valentine MOA and Reserve would undergo an increase of overflights of 1,000 percent (or 14,000 flights per year). The level of protest did halt the overflight expansion, but the Air Force's insistence that it needed ever more open space for testing rankled Superintendent McChristian, much as it did his colleague at White Sands National Monument, Donald Harper, who had the air base as a neighbor in the Tularosa basin of southern New Mexico. [26]

At the close of his fourth year of service as Fort Davis' superintendent, Doug McChristian had much to consider when the NPS asked him to comment upon the topic: "Where the National Park Service is Going." Buoyed by his experiences with private fundraising, yet burdened by limited operating budgets, McChristian wrote in November 1984: "I cannot escape the feeling that the Park Service is losing something, a spark or optimism that it once had." This McChristian blamed on the NPS' "becoming increasingly pre-occupied with things like regulatory compliance, 'special emphasis' programs, needless paperwork, and personnel problems." While this could be nothing more than "an inescapable syndrome inherent with being a Federal agency," yet McChristian hoped that the NPS "and its people" could be "reoriented, redirected to the traditions upon which the Park Service is founded - resources and visitors." The 15-year veteran of NPS employment conceded that "the agency must grow with and adapt to a changing and increasingly complex world." Nonetheless, said McChristian, "we should make every effort to hold fast to our principles," which he defined as "the dedication, attitudes, and ability of our employees." McChristian worried particularly about the impact of the expanded paperwork on small parks like Fort Davis, and the need for "greater understanding and cooperation between central office staff and field personnel." The superintendent had "worked on both sides of the fence," and had concluded about the regional office: "I know how they can hinder our ability to get the job done." [27]

The Southwest Region of the NPS had to recognize the sincerity of McChristian's words, given the success of his park in raising funds for the barracks restoration. Thus deputy regional director Donald Dayton, himself a former superintendent at parks like White Sands and Carlsbad Caverns, cited Fort Davis in January 1985 as "one of the few consistently well run parks in the Region." "Such compliments don't come down the line very often," McChristian told his staff, and he thanked them for their contributions to the park's recognition. "The credit for this," said the Fort Davis superintendent, "falls to each and everyone of you for doing your utmost in the big things as well as the countless details you may feel go unnoticed and unappreciated." McChristian long had felt that Fort Davis was "an above average operation," and the staff needed to know the thoughts of the regional office as it moved towards the second half of the 1980s. [28]

On January 13, 1985, Fort Davis hosted the groundbreaking ceremonies for the barracks restoration project. While donations for rehabilitation had come rather easily, support from the private sector for the furnishings lagged. At this juncture, Bill Gwaltney began another letter-writing campaign to increase awareness in the story of Fort Davis, developing a host of imaginative ventures that would earn him accolades within the NPS by the time he left the park the following year. Gwaltney's efforts began in February 1985 when he approached Victor Julian, director of national events for the Anheuser-Busch brewing company of St. Louis. Fort Davis needed "replicas of the furniture, footlockers, and uniform parts of the Indian Wars Period" for the barracks, which he estimated would cost about $30,000. Gwaltney had learned of Anheuser-Busch's interest in "supporting the shooting sports," and he proposed that the brewer "purchase 22 replica springfield carbines ($125 each) of the type used by cavalry troopers." As his incentive for Anheuser-Busch, Gwaltney wrote: "It will come as no surprise to you that one of your company's products, Budweiser beer, was a favorite of frontier soldiers," as "many archeological excavations at Western military posts have uncovered dozens of quart sized Budweiser bottles." Fort Davis itself had in its "study collection" "two complete 19th century Budweiser bottles," one of which the park hoped to display as part of the barracks project. [29]

|

|

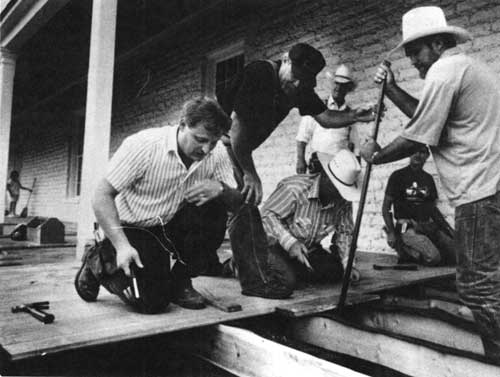

Figure 46. Pablo Bencomo (left) receives

certificate at retirement dinner (March 1984). At center is

Superintendent Doug McChristian; at right standing is SWR Deputy

Director Donal Dayton. Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

Gwaltney drafted similar letters to many organizations nationwide in search of furnishing monies, and read widely in magazines and newspapers that carried stories about the black military experience. In February 1985, Gwaltney agreed to travel to Odessa to speak to a black church service on the meaning of the black soldier's life. In like manner, Superintendent McChristian notified Colonel James Revels, U.S.A. (retired), of El Paso that he had read the latter's article in the El Paso Times entitled, "Buffalo Soldiers Defended Southwest." "Quite honestly," the superintendent informed Revels, "we need assistance in the greater El Paso area as we have no representation there at present." McChristian suggested that "one or a series of news articles would be valuable in drawing public attention to the project." Also solicited by McChristian in El Paso was Keith Kochenour, director of creative services for the Publishers and Advertising Specialists of that city. Kochenour organized the Paso Del Norte Gun Show in April 1985, and Fort Davis had asked for exhibit space there. McChristian wished to draw attention to the barracks refurnishing program at the gun show exhibit, and sent publicity materials to the advertising agent to demonstrate the merits of the Fort Davis request. [30]

Little else seemed to matter to the Fort Davis staff as the Friends group generated interest and donations to the barracks restoration project. Doug McChristian authorized Mary Williams in June 1985 to travel to Washington for an extended research trip in the military records of the National Archives. Her task was to collect the materials that park historian Ben Levy had not consulted in the mid-1960s, primarily the documentation on the "First Fort [1854-1861]." The superintendent also contacted the nation's most prominent black publication, Ebony Magazine, that month to submit an article on the Buffalo Soldiers. Revealing the shift from the generic soldier's story to that of African-Americans, McChristian told Charles Sanders of Ebony that "today Fort Davis National Historic Site is a major facet of Park Service efforts to place black history in [its] proper perspective in the interpretation of American history to the visiting public." In July, Bill Gwaltney corresponded with Bernie Casey, former professional football player for the Los Angeles Rams and one of the officers of the Black Screen Actor's Guild. Gwaltney hoped that Casey could interest filmmakers in Hollywood in telling the black soldier's story; a scenario that he also presented to perhaps the most prominent black director and actor of his generation, Sidney Poitier, known for his Oscar-winning role in Lilies of the Field (1963), and his direction and starring role in Buck and the Preacher (1972), a black version of the 1950s television series, Wagon Train. [31]

These efforts at promotion and publicity for the park and its barracks restoration project met with mixed success in the summer and fall of 1985. Neither Casey nor Poitier demonstrated interest in the queries of McChristian and Gwaltney. In addition, Ebony Magazine shocked Gwaltney with their "quite noncommittal and terminal response" to the request for an article about Fort Davis. The park technician felt betrayed somehow by the publication, stating in November that "as a black growing up in Washington, D.C., I enjoyed your magazine not just as a journal of progress in black equality and self awareness, but as an historical record as well." Gwaltney referred to himself as "a black Park Ranger" who believed that "it is critical that the black publishing community (in which your publication plays a major role) open lines of communication with those areas of the National Park Service that deal with black American history." Ebony could highlight "an important aspect of American history that has been ignored for many years by race-conscious writers, historians, and movie producers." The Fort Davis story could also correct the assumption "by the press in general, that the ranks of the Park Service and other 'non-traditional' organizations do not contain black individuals." "From entrance station duty to backcountry patrol," said Gwaltney, "and from search and rescue missions to managing National Park Service areas, black park service professionals are involved with the history of the past, the protection of the resources of today and the future of the National Parks." He hoped that Sanders and his magazine would rethink their decision to reject a Fort Davis narrative so that the nation could read of "the proud military tradition of the Buffalo Soldiers," whose "voices are now stilled but their story deserves to be told." [32]

While the rebuff from a national black magazine may have rankled Gwaltney, an incident involving the famed novelist James A. Michener and the black park ranger nearly proved more disastrous for Fort Davis. Michener, known for his massive works on such topics as Space, Hawaii, and Centennial (the latter a historical treatment of Colorado), had agreed to write a novel entitled, Texas, as part of that state's 1986 sesquicentennial. In his inimitable style, the author wished to see as much of the Lone Star state as possible during his research phase. One place that he wished to visit was the Davis Mountains and their NPS park. He accepted the offer of Clayton Williams, a Davis Mountains rancher, cable company owner, and later candidate for governor of Texas (1990), to ride in Williams' helicopter around the Trans-Pecos region. When the party reached Fort Davis, Williams decided to have his pilot land in the parking lot of the federal facility; a violation of codes and of the safety of the visitors. Bill Gwaltney, as the ranger on duty that afternoon, came out to the helicopter, informed a rather irate Williams that he could not permit them to land on park property, and watched as Michener et al., lifted off for their return to Williams' ranch. [33]

The Fort Davis staff thought no more of the Michener incident until October 1985, when Random House publishers released the novel in time for the kickoff of the 150th anniversary of the fall of the Alamo. Doug McChristian and his employees were thus shocked to open the book and read in its introduction: "I also had the honor of being thrown out of Fort Davis, a U.S. National Park and perhaps the best of the restored of the Texas forts. Alas, I never saw it." The superintendent considered it "regrettable that such a remark has to mar an otherwise fine work, especially since you made no attempt to describe the circumstances." McChristian then reiterated the incident report filed by Ranger Gwaltney, which clearly articulated NPS policy on unauthorized flight landings on park property. "As an author and historian," said the superintendent, "you can well-imagine how disruptive a low-flying aircraft is to a park visitor on the ground who is trying to immerse himself in the 19th century." In addition, "there is always the potential for malfunction or pilot error." "Damage or destruction of any historic building," McChristian suggested, "would be an irretrievable loss." The superintendent also took exception to "one of your party's uncomplimentary remarks about the Federal Government." Ranger Gwaltney' s offer to drive Michener from an off-site location to the park was rejected, leading McChristian to conclude: "We feel that your claim that you were 'thrown out' of Fort Davis. . . is an exaggeration that is misleading to anyone unfamiliar with the circumstances." He realized that "there is little that might be done at this time to remedy the situation," but hoped that Michener would return so that "it will be our pleasure to provide you with a 'cook's tour' of the Site." [34]

The irony of Michener's pique at Fort Davis was that the "Texas Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History" had wanted to include information on the park in the Lone Star birthday celebration. Doug McChristian wrote to the association's president, Melvin Wade, to solicit his support for the barracks restoration project, especially its fundraising campaign for the furnishings. One feature of that campaign was an idea developed by Bill Gwaltney to produce and sell "a Buffalo Soldier Commemorative Revolver." The superintendent believed that, "to our knowledge this is the first such commemorative to honor the black American soldier." Gwaltney had convinced two magazines that appealed to weapons enthusiasts, Guns and Ammo, and the American Rifleman, to publish articles on the commemorative revolver. Other activities that the park undertook on behalf of the new barracks included acceptance of a $15,000 bust of a Buffalo Soldier by sculptor Eddie Dixon of Lubbock, and receipt of the traveling exhibit "Ebony Odyssey." Put together by the Fort Bliss Museum of El Paso, the exhibit received what McChristian called "many favorable comments," and "served as a striking and dramatic focal point for visitors as they enter the museum and park visitor center." Word of the project had reached as far east as New York City, where Robyn Alexander, a teacher at the "General Daniel 'Chappie' James Jr. School," solicited materials on the Buffalo Soldiers. John M. Sutton, acting superintendent of Fort Davis, sent Ms. Alexander's students copies of articles written for Black History month, as well as a bibliography that the park staff used to prepare its interpretation of the black experience. [35]

For all these activities, park ranger Bill Gwaltney received much praise from his colleagues at Fort Davis, and from his peers in the park service. In May 1985, McChristian nominated Gwaltney for the "Fourth Annual Freeman Tilden Award for Outstanding Contribution to Interpretation." This competition was named for the "father" of park service interpretative programs, who worked in the pre-World War II era. The superintendent, himself an expert in matters of living history, described Gwaltney as "an excellent interpreter," with "a natural ability to communicate effectively with his audience, to alter his presentation to the audience's interest level, and to stimulate conversation with visitors which leads to further theme discussion." Then in December, supervisory ranger John Sutton recommended Gwaltney for the "Southwest Region Special Events Team." This award provided its participants with "additional experience in law enforcement and visitor protection." Gwaltney had "a full law enforcement commission, firefighter 'red card,' current standard first aid and CPR certification," along with "automatic weapons training from Quantico Marine Base," and certification from the National Rifle Association (NRA) as an expert in "rifle, pistol and shotgun." He had taught courses at nearby Sul Ross State University in weapons use, and "in tae-kwon-do Korean martial arts." Gwaltney for his part informed G. Ray Arnett, executive vice-president of the NRA, of his own support of the organization's goals and objectives. "You are no doubt well aware," the ranger told Arnett, "of both the budget cuts affecting the National Park System and the feeling on the part of anti-gunners that the role of firearms in building our country should be minimized or ignored completely." He then used his Freeman Tilden nomination to campaign for the barracks restoration project, specifically the 10th Cavalry revolver sale. "These black soldiers," said Gwaltney, "many of them combat veterans, showed time and again, courage, patriotism and sacrifice in the execution of their duties." [36]

The intense focus upon the accomplishments of black soldiers, and the role of Fort Davis' first black ranger therein, meant that the park had an opportunity to become a national center for the promotion of frontier black history. While this would have required a staff and budget far beyond the scope of the NPS, Bill Gwaltney's endeavors provided a window on the possibilities of the park service as a player in the national dialogue about race and ethnicity. One example of that came in the spring of 1985, when Superintendent McChristian wrote to the mayor of Thomasville, Georgia, M. Tom Faircloth, to support that community's efforts to convince the U.S. Postal Service to print a commemorative stamp of Henry 0. Flipper. Thomasville was Flipper's hometown, and there the former Fort Davis officer was buried after his death in 1940. McChristian described his park as having the "dubious distinction of being the scene of his 1881 court-martial." McChristian and Mary Williams prepared a lengthy biographical sketch for the Thomasville mayor, as well as for Ray 0. MacColl, assistant superintendent of schools for Pelham, Georgia. Speaking in a forthright manner about Flipper and race not seen at Fort Davis since the days of Frank Smith, McChristian characterized the posthumously exonerated black lieutenant as someone who "accomplished what many dared not dream of." Flipper's attendance at West Point rendered him "the first of his race to pursue careers in fields previously closed to blacks." The engineering graduate, despite his legal problems, in the words of McChristian, "was undoubtedly a pioneer for equal rights in a time when the phrase was uncommon to most Americans." Thus it was no surprise in the summer of 1985 that Fort Davis, along with Sul Ross State University, sponsored a one-act play, "Held in Trust," based upon the life of Henry Flipper. An El Paso actor, Bob Snead, a former Army aviator, portrayed Flipper to audiences in his hometown and around the Southwest, and appeared in Alpine as part of Fort Davis' second annual barracks restoration festival. [37]

Fort Davis could not focus solely on a high level of historical promotion, as the park had standing obligations of maintenance and service, as well as responding to research inquiries about a wide range of historical phenomena. Mary Williams continued to develop her programs on women and the frontier military, with the NPS sponsoring Women's History Week in early March. While not as high in profile as Black History Month, women's stories had finally gained some recognition within the male-dominated park service. Superintendent McChristian asked the "Federal Women's Coordinator" for the Southwest Region to indicate "how many other areas . . . recognized Women's History Week." Another indicator of changes in gender roles in the NPS was the invitation extended in April to Sandra Myres, professor of history at the University of Texas at Arlington, to speak to the Indian Wars' training program to be held at Fort Davis. Bob Utley was also asked to appear in the Memorial Day weekend activity, addressing the topic: "Popular attitudes towards western expansion." Myres, a specialist in the history of the Spanish Southwest who had moved in the early 1980s into the story of women in the region, was asked to speak on "women's attitudes towards life at a frontier military post." John Sutton suggested that Myres explore "such subthemes as women's expectations of frontier life during the last half of the 19th century, women's attitudes towards raising a family at a frontier military post, and the differences and similarities of the frontier army family in relation with the remainder of 19th century American society." [38]

Gender and service to the park also surfaced in the area of volunteerism; a dimension of interpretation that would become all the more critical as the barracks restoration project moved to closure. A group of local women, including Fort Davis' Mary Williams, organized the "Davis Mountains Quilters' Guild" in 1985 to make quilts for the barracks. Original planning for the refurnishing of the facility identified the need for seven quilts, and research revealed that "the use of quilts appears to be characteristic to black enlisted men." The quilters donated coverings to be auctioned as part of the refurnishing fund, which by early 1986 had reached $15,000 (or half of the target of $30,000). Ranger Williams, the mother of an adolescent daughter, also realized that the Girl Scouts could provide services as volunteers that equalled those of the Boy Scouts. The Department of the Interior had entered into a "Memorandum of Understanding [MOU]" with the Boy Scouts, which Williams believed should be extended to young girls so that the "work the girl scouts are doing in the parks will received official recognition." Williams saw their contribution as essential to the success of a park like Fort Davis, which had a small volunteer base and needed all the help that it could command. She went so far in the fall of 1986 to inform the Southwest Region's VIP coordinator that the program needed significant reforms. Her own successful VIP program included a newsletter, but would benefit from more formal gestures of recognition: an appreciation luncheon, awards, on-site housing or camping facilities, and extended training and mentoring. "From personal observation," said Williams, "it is better not to have a volunteer program than to have a poor one." She wondered if all parks in the region shared Fort Davis' commitment to the support of volunteers, and she reminded her superiors in Santa Fe: "To help parks realize successful volunteer programs, the lines of communications between parks, regions, and Washington need to be expanded." [39]

The role of the Friends' group in expanding the interpretive programs of Fort Davis also concerned Superintendent McChristian in the winter and spring of 1986, as the barracks awaited the last of their furnishings. He faced continued reductions in funding from the NPS, but "with the end of the barracks restoration in sight, the [Friends'] group is enthusiastic about pursuing future projects." This eagerness, and proven ability at fundraising, confronted the superintendent with an historical dilemma: the lack of a master plan to guide the staff and Friends. "Management needs a document," said McChristian, "either outlining development plans, or one clearly defining the logic for not continuing restoration." Another feature in need of clarification was "the proposed switch of the museum and administrative areas at park headquarters." What McChristian could discuss with the Friends was a plan to restore and refurnish the post hospital. The Friends, McChristian remembered eight years after leaving Fort Davis for the second time, had first expressed interest in the rehabilitation of the chapel. "Fort Davis is a very religious area," said McChristian, where the community's many uses of the facility rendered the chapel "a social and religious center." In shifting their attention to the hospital, the superintendent told the Southwest Region that the building "represents perhaps the best extant example of a frontier U.S. army hospital in the Southwestern United States." Despite the modest efforts to provide access to the hospital, "the building evokes a great deal of visitor interest and curiosity about medical facilities and practices of the late 19th century." McChristian drafted a plan that received little support to spend $450,000 to prepare the facility for visitation of some 75,000 per year. "Since virtually everyone can relate to illness and contemporary medical science," said the superintendent, the park could reach visitors in new ways by explaining such topics as "medical personnel and their duties, routine hospital operations, 19th century diseases and treatments, the hospital's role as an entity of the fort, relations with the civilian community, and the contributions of frontier army surgeons to medical and natural science. [40]

The seriousness of the interpretive program needs at Fort Davis had their more wistful counterpart in the 1986 sesquicentennial of Texas. Ironically, the major push to highlight the distinctiveness of the Lone Star state ran into trouble just as the year began. In January 1986, Texas' central economic feature, oil production, collapsed in value as the consortium known as the Oil Producing and Exporting Countries (OPEC) reduced prices in the space of 60 days from nearly $30 per barrel to less than ten dollars. This downward spiral in earnings and tax revenue caught Texas and the nation by surprise, with the former suffering both economic and psychological trauma for years. The lack of funds, as well as state pride, rendered the ambitions of the sesquicentennial moot, and Fort Davis thus had few requests from Texas officials to conduct joint programs 150 years after the fall of the Alamo. In fact, the only venues of note that engaged the staffs time were the plans of Bob Reinhadt, whom Superintendent McChristian described as the only member of the local sesquicentennial committee, to "create a self-guided auto tour of the old El Paso stage route through Fort Davis," and the inquiry of William Sandidge of San Antonio to retrace the journey of the 1850s camel trains of the U.S. Army. The superintendent conceded that this could "undoubtedly rank among the most unusual during the Sesquicentennial." Unfortunately, Fort Davis believed that "keeping live animals here in permanent exhibit would be neither economically feasible nor necessary from an interpretive standpoint." Sandidge persisted with his plans to raise some $30,000 to send the camels through the Davis Mountains, but Fort Davis could not agree to provide monies to pay for one animal on the route. [41]

In May 1986, Doug McChristian decided to accept reassignment to Hubbell Trading Post in northeastern Arizona as superintendent. He recounted for the Alpine Avalanche the changes that the Texas park had undergone since his return in 1980. McChristian was most proud of the formation of the Friends group, which triggered more interest in the upkeep of the physical plant of Fort Davis. The park also had prepared its first vegetation plan, a historic scene management plan, and had begun the process to acquire a general management plan. An initial archeological survey resulted in an historic base map consisting of 223 identified historic structures, including some 70 sites "previously unknown or not located." The Southwest Region sent in McChristian's place Steve Miller, most recently the superintendent of Arizona's Navajo National Monument. The New York state native had spent five years at the isolated park on the Navajo reservation, and the previous five and one-half years at western New Mexico's El Morro National Monument. Miller described himself to the Alpine Avalanche as a "Civil War buff," and indicated that he, his wife Char, and their two daughters looked forward to the transfer to the west Texas mountains. [42]

The Steve Miller era at Fort Davis was marked by a stream of awards and plaudits for the commitment of the staff in the 1980s to emphasize the complexity and richness of the park's history. Much of this recognition belonged to the departed superintendent Doug McChristian, whose belief in the efficacy of living history and his skills at organization made Fort Davis a better institution. For the next two years (1986-1988), park staff and management participated in celebrations and historical programs that showed the wisdom of McChristian's leadership. From the 25th anniversary of the park's creation (September 1986), to the long-delayed dedication of the enlisted men's barracks in February 1988, public attention focused on the park in ways not seen since the star-studded ceremonies of 1966. In addition, park staff received publicity for their contributions to history and the NPS, both individually and collectively.

Whenever a new superintendent arrives in a park, there is a period of assessment and contemplation prior to the implementation of distinctive plans and projects. For Steve Miller, so much work was in motion that he would oversee its completion before he could put forth his own concepts and designs. Ongoing in the summer of 1986 was Jerome Greene's historic structures report, as well as the final initiative to fund the refurnishing of the barracks. The park maintenance staff also built and installed five new exhibits in the post commissary building, and displayed three artillery pieces in the barracks wing: a gatling gun, mountain howitzer, and ordnance rifle. The maintenance workers also adapted the grounds to accommodate handicapped visitors. Central to these successful programs was the work of students from Sul Ross State University, who benefitted from the Cooperative Education Program agreement that Fort Davis had signed in the early 1970s with the college. Steve Miller arrived at his new post only to learn that the state of Texas contemplated closing the Alpine campus, or merging its services with other institutions of higher learning. The superintendent thus asked his staff to conduct an inventory of the working relationship between the park and Sul Ross. They itemized all manner of reciprocal services, from museum training courses to graduate research in history and ecology to employment of some twenty students at the park. Among these were eight women and seven Hispanic students; numbers that indicated Fort Davis' sincerity in meeting federal goals of equality in hiring and training. [43]

The fulltime staff at Fort Davis were also recognized for their expertise and commitment to history by a variety of organizations in the region. Supervisory park ranger John Sutton was invited to join the groundbreaking ceremonies of historic structure rehabilitation at Fort Stockton. The Annie Riggs museum had learned of the successes of Fort Davis in a similar endeavor, and asked Sutton to speak to an audience of 75 persons about "soldier life and cavalry field service." Then in November 1986, Sutton traveled to the San Antonio Missions National Historic Park to supervise rehearsals of their living history drama, "The Immortal 32." Bill Gwaltney provided similar services in June 1986 when the Center for the Study of African and Afro-American Life at the University of Texas invited the Fort Davis ranger to participate in its "Juneteenth" celebration. Designed to mark the date in 1865 when slaves learned that the South had surrendered in the Civil War, Juneteenth (so named for the pronunciation of the date of June 19th by the slaves) became in the 1980s a major historical event for blacks in the West and Southwest. Gwaltney delivered public lectures to school groups on the Buffalo Soldiers, appeared on local Austin television, and conducted a slide show for dignitaries gathered in the state capitol (among whom was Texas native and famed civil rights leader Dr. James Farmer). The Fort Davis ranger then graced the pages of the Austin American-Statesman as it covered the Juneteenth festivities, attended by some 6,000 guests. Upon his return to Fort Davis, Gwaltney, who by then had applied for a transfer to Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site in La Junta, Colorado, reported to Superintendent Miller that "appropriate programs [like Juneteenth] can help to educate the public, stimulate interest in the site and provide publicity for the interpretative mission of the National Park Service." [44]

|

|

Figure 47. Superintendent Steve Miller

speaking at Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Dedication Ceremony (September

1986). Courtesy Fort Davis NHS. |

Fort Davis' own history received much attention in the fall of 1986, as Steve Miller and the staff coordinated the 25th anniversary of the signing of the enabling legislation by President John F. Kennedy. The park wanted to recapture some of the lustre of the 1966 dedication, and invited individuals like Lady Bird Johnson, now living in Austin. On September 7, some 400 people gathered on the parade ground to witness the silver anniversary celebration, listening to speeches from Martin Merrill, who had testified before Congress on behalf of the park; Donald Dayton, deputy Southwest Region director; and Bob Crisman, chief ranger at Fort Davis in the late 1960s. This event came one week after the Friends Festival on Labor Day weekend, which raised some $4,000 for the barracks furnishing project. Superintendent Miller reported to the region that Fort Davis stood within $17,000 of ending the fundraising campaign, and that the latest Friends event was the most popular ever, with its "antique auction, historic weapons demonstrations, women's fashion review of the 1880s, old-fashioned children's games, wagon rides, barbecue, concert by the 62nd Army Band and a baseball game using 1884 rules." [45]

Staff work to guarantee such successful activities as the Friends festival and the silver anniversary earned deserved respect from the NPS' support agency, the SPMA. Mary Williams received that organization's "Superior Performance Award," the first such designation in its history. SPMA executive director Timothy J. Priehs announced on November 7, 1986, that the long-time Fort Davis employee stood out among all NPS personnel in the region's nearly 50 units for her "outstanding contribution to the programs and operations of SPMA . . . and for tireless dedication to the Association's purpose, helping to ensure the preservation of the National Park System." In the previous five years, Fort Davis' SPMA sales had increased some 200 percent, the proceeds of which could be applied to refurnishing purchases, or Mary Williams' travel to Washington that summer to conduct research in the National Archives. "Without organizations like SPMA," said Miller, "I don't know how we would do those extra special things that really put the polish on." One example was the private agency's donation every year of $500 for discretionary park spending that could not be absorbed by federal appropriations. Mary Williams had used the 1986 allocation for such items as "a Christmas tree and historical Christmas decorations for the CO's quarters, a copy of the 1884 baseball rules, library books, subscriptions to scholarly journals, special awards for volunteers, and the reception for the 25th anniversary celebration of the signing of legislation which created Fort Davis NHS." [46]