|

FORT DAVIS

History of Fort Davis, Texas |

|

CHAPTER SIX:

REESTABLISHING THE FEDERAL PRESENCE

The Civil War left the non-Indian settlement of the Trans-Pecos in disarray. With the withdrawal of both Confederate and Union troops, Indians had stepped up attacks against intruders. The conclusion of the civil conflict, however, saw a resurgence of travel across the plains west of San Antonio. The federal government was again compelled to establish a lasting presence in West Texas if it hoped to protect its citizens. As was the case before the war, the site along Limpia Creek seemed ideal for a military garrison. This time, the intense sectionalism of the previous decade would no longer cloud the interest of the United States in fostering western development. Although the federal government remained small, it could now approach the west free of the political paralysis of the 1850s.

The War Department mustered nearly a million men out of its massive volunteer forces by late spring 1866. But in partial recognition of its western obligations and the need to reassert federal authority in the South, Congress increased the regulars, who had maintained separate status throughout the war, from six cavalry regiments to ten, and the infantry from nineteen to forty-five. It also retained five artillery regiments, giving the new regular force more than 54,000 troops. Subsequent reductions in 1869 and 1870, however, eliminated twenty infantry regiments and limited the number of enlisted men to 30,000, still larger than prewar levels. [1]

Army organization remained substantially unchanged. A colonel commanded every regiment. Cavalry and artillery units each included twelve companies; infantry regiments had ten companies. The War Department set company strength at sixty-four privates. Ten departments and bureaus—Adjutant General, Inspector General, Judge Advocate General, Quartermaster, Subsistence, Medical, Pay, Ordnance, Signal Corps, and the Corps of Engineers—comprised the army's staff and administrative agencies. Commissioned personnel, selected by often politicized boards of fellow officers, came from both the regulars and the volunteers. [2]

In April 1865 Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant selected Philip Sheridan, a crusty veteran of some of the Civil War's hardest fighting, to command Federal forces in the Lone Star state. Two immediate problems demanded Sheridan's attention. One was the presence of several thousand French troops propping up the Archduke Maximilian's reign as emperor of Mexico. Sheridan set up a powerful army of observation along the Rio Grande, forcefully demonstrating U.S. opposition to the French presence. In the wake of pressure exerted by Secretary of State William Seward, imperial French forces withdrew and Maximilian's tottering regime collapsed. [3]

The second issue—that of convincing Texans to recognize the federal government—proved more difficult. "Texas has not yet suffered from the war and will require some intimidation," asserted Sheridan, who deployed his units amongst the more populous interior communities where they could enforce federal laws. Texans protested Sheridan's dispositions, claiming that the soldiers should instead suppress Indian attacks. Texas politicians briefly entertained a proposal which would have allowed a private company to establish a farming colony along the Pecos River. The settlers, it was reasoned, would deflect Indian raids. Gov. James W. Throckmorton also wanted to raise one thousand state troops to patrol the frontiers. But Sheridan firmly opposed such moves. "I do not doubt that the secret of all this fuss about Indian trouble is the desire to have all the troops removed from the interior and the desire of the loose & lazy adventurers to be employed as volunteers," he wrote. Of the alleged Indian depredations, Sheridan judged that "these reports are now manufactured wholesale to affect the removal of troops from the interior to the frontier." [4]

The disposition of regular troops in the interior antagonized many old-time Texans. Overwhelmingly sympathetic to the Confederacy, the Texans argued that soldiers should patrol the state's frontiers. Sheridan, by contrast, blamed the Indian troubles on the Texans. Summing up operations for 1867, Sheridan explained that "a few Indian depredations occurred . . . arising principally from the adventurous character of the frontier settlers, who, pushed out toward the Indian territory, thereby incurred the risk of coming into contact with hostile Indians." He needed troops in the interior to maintain law and order and could not spare the manpower to protect those foolish enough to incite Indian attacks. Noting the mounting assaults on Texas blacks by groups like the Ku Klux Klan, Bvt. Maj. Gen. Joseph J. Reynolds supported Sheridan's position. "The murder of negroes is so common as to render it impossible to keep an accurate account of them," Reynolds argued. [5]

The army played a crucial role in Reconstruction Texas. Early state elections reflected the strength of conservative voters, intent on restoring as much of prewar society and political leadership as they could. Seeking to block the return of former Confederates to power, Unionists used the army to assist the development of Texas's nascent Republican party. Not only did the military attempt to shield blacks from the wrath of white supremacists, it often controlled electoral precincts and dominated vote-gathering and counting procedures. Such political involvement became even more pronounced with Joseph J. Reynolds's accession to command of the Fifth Military District in 1867. [6]

Many Texans bitterly opposed military rule and seized upon every army failure as an opportunity to revile the Reconstruction forces. Envisioning an Indian attack around every corner proved a popular pastime. Despite the tendency to exaggerate the Indian threat to frontier expansion, the Trans-Pecos was indeed experiencing several bloody encounters between Indians and non-Indians. In early February 1866, for instance, an N. Webb and Company wagon train left El Paso bound for San Antonio. The caravan met a few Indians herding livestock near Eagle Springs. The resulting fight saw the whites capture the Indians' animals. Reinforced, the Indians peppered the wagons well into the following night, making an unsuccessful effort to stampede the cattle and horses. Although none of the Webb men was hurt, they later reported that forts Lancaster, Stockton, Davis, and Quitman lay in ruins. [7]

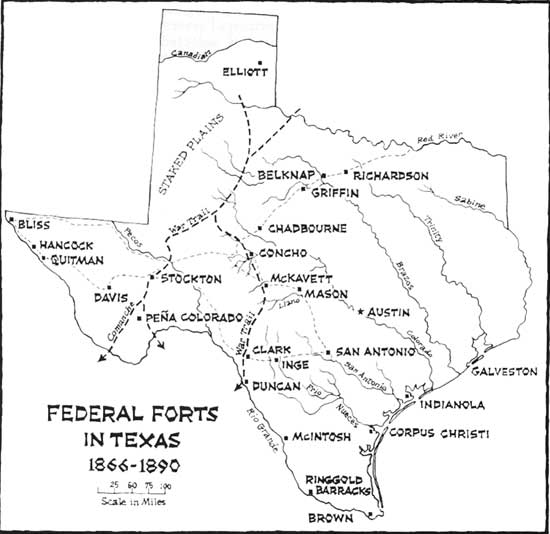

Another wagon train met a similar fate as it crossed the Trans-Pecos from the east. John and James Edgar each outfitted trains of twenty wagons and two hundred mules. John's train was several days ahead of that of James when it reached Wild Rose Pass in Limpia Canyon. An attack by Espejo's Apache band forced the first group back toward old Fort Stockton. En route, John found that a freak norther had ravaged his brother's caravan west of the Pecos River. The Edgars combined their forces and eventually reached El Paso with about half of their original cargo. [8]

The return trip to San Antonio proved equally eventful. Twenty-eight men, two women, and two children comprised the party. Soon after receiving a corn shipment from Presidio at abandoned Fort Davis, the group found itself under attack by Lipan and Mescalero Apaches. Their initial strike blunted, the starving Indians, later joined by some Navajos from New Mexico, laid siege to the train. A parlay finally broke the impasse; the Indians allowed the interlopers to pass unscathed in return for a supply of corn. [9]

Stage companies assured prospective passengers of their safety, but West Texas travelers clamored for official protection. In one unconfirmed encounter, 350 Apaches reportedly besieged 40 ex-Confederate soldiers east of abandoned Fort Stockton. Newspapers recorded the deaths of 34 men between Fort Quitman and El Paso in a period of only a few weeks and suggested that the army raise volunteer units. Governor Throckmorton, though more concerned about attacks along the northern frontiers of Texas, noted that Mescalero and Lipan Apaches harassed travelers along the road to El Paso. "The military should have orders to route [sic] them out even though they cross over to Mexico to accomplish it," argued Throckmorton. [10]

Sheridan had to do something to protect the frontiers, as the government granted Frederick P. Sawyer the mail contract between San Antonio and El Paso in early July 1866. That fall Sheridan promised to move a few mounted troops to the perimeters of the state the following spring. He remained skeptical; a staff officer's uncovering of a false story of an Indian massacre near Camp Verde had strengthened the general's suspicions. But to avert a call-up of state volunteers and to display the power of the federal government, Sheridan readied several units for Indian service in spring 1867. Like Governor Throckmorton, the general initially considered northern Texas most vulnerable. Sheridan identified twelve likely sites for federal garrisons. Neither forts Davis nor Bliss appeared on Sheridan's preliminary list, though both would eventually serve as important links in frontier defenses after the Civil War. [11]

Inadequate resources, inconsistent federal policies, and a dearth of strategic planning sharply hampered the military's post-Civil War efforts on the frontiers. Manpower remained insufficient to handle every task assigned to the army. The federal government's refusal to adopt a systematic Indian policy further confused military operations against native Americans. The government vacillated between peace and war, thus discouraging long-range military planning among officers. Only the ultimate goal proved consistent—the United States believed it had the right, even the duty, to remove Indians from their native lands. Neither politicians nor army officers, however, agreed upon the best means of achieving this objective. [12]

More interested in replaying the Civil War, securing promotion, or studying European-style conflicts, few officers devoted the time or thought necessary to formulate a clear doctrine against Indians. Two geographic divisions—the Missouri and the Pacific—handled most Indian questions, although this resulted more from the need to provide every brigadier general with the command of a department rather than from a calculated effort to create specialized Indian-fighting units. Texas posed special problems. Should it be part of the sprawling Division of the Missouri, which encompassed most lands between the Mississippi River and the Continental Divide, or should it be one of the special Reconstruction districts? The army answered that question in March 1867, by organizing Texas and Louisiana into the Fifth Military District for purposes of Reconstruction. Thus, despite Sheridan's recent concessions, enforcing Reconstruction, not evicting Indians, still remained the military's primary goal in Texas. [13]

Minor administrative changes were forthcoming. Military authorities divided the state into subdistricts, or, after gaining departmental status, districts. By 1869 the Lone Star state included the subdistricts of the Presidio (including forts Bliss, Quitman, Davis, and Stockman), Brazos (Griffin and Richardson), Pecos (Concho, McKavett, Clark, and Duncan), and Rio Grande (McIntosh, Ringgold, and Brown). For many years, Fort Davis served as headquarters for the Presidio command. Higher authorities rarely meddled in the affairs of officers on the scene. In requesting information on efforts to protect mail parties in the subdistrict of the Presidio, for instance, one aide noted that "it is not intended to interfere with Sub-District Commanders . . . without full discussion and for urgent reasons." [14]

The military introduced few strategic innovations after 1865. Army forts were located with more regard to domestic politics than to Indian policy. A post meant jobs, money, and increased safety. A thin line of bluecoats manned these frontier positions, but without formalized, consistent doctrine, flailed away wildly at their Indian foes. Cavalry seemed of particular value, although even the mounted men rarely caught hostile tribesmen. And given the federal government's limited size and budget, the army never had enough cavalrymen to patrol every exposed area. Reservations and international boundary lines further shielded Indian raiders, who, after committing a depredation, often fled to the safety offered by such havens. [15]

Phil Sheridan, the army's key official in Texas during the late 1860s, seemed little troubled by cerebral questions of policy, doctrine, or morality. He believed the Indians must be shunted aside; to do this in West Texas he selected the Ninth Cavalry Regiment. The black cavalrymen would help protect the Trans-Pecos; at the same time, their new stations, isolated from the more populated areas, would remove a point of contention between the army and many whites who resented black soldiers. Lt. Col. Wesley Merritt would oversee the reoccupation of Fort Davis. A thin, boyish-looking brevet major general, Merritt brought an outstanding combat record to the frontier. Graduated from West Point in 1860 and breveted for his actions at Gettysburg, Yellow Tavern, Haw's Shop, Winchester, Fisher's Hill, and Five Forks, he had repeatedly displayed his abilities as a fighting cavalryman. Despite his relative youth, a Democratic family heritage, and his having been in Europe during the politically charged army reorganization process, he received the lieutenant colonelcy of the Ninth. [16]

The Ninth Cavalry was one of six black regiments originally created by the army reorganization bill of 1866. The decision to form such units stemmed in part from a desire to recognize black contributions during the Civil War. Others hoped to offer blacks wider opportunities for government employment, although white officers would command. Congress consolidated four of the black infantry regiments into two as a part of general 1869 army reductions; each of the remaining units—the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry, and the Twenty-fourth and Twenty-fifth Infantry—was ultimately sent to Fort Davis. Companies of the Twenty-fourth Infantry helped garrison the post from 1869 through 1872 and again in 1880. The Twenty-fifth was stationed there from 1870 to 1880. Among the cavalry the Ninth was present between 1867 and 1875; elements of the Tenth remained at Fort Davis from 1875 to 1885. [17]

|

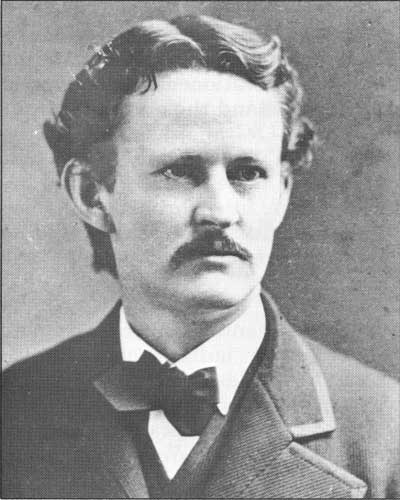

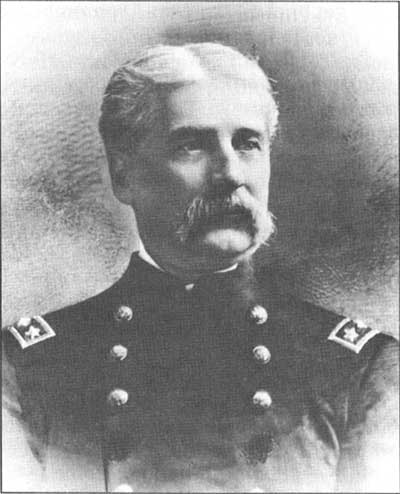

| Fig. 6:14. Lt. Col. Wesley Merritt, commander of Fort Davis in 1867 and 1868-69. Photograph courtesy of Custer Battlefield National Monument, National Park Service. |

Officers and observers held mixed opinions about the qualities of their black troops. Brig. Gen. Edward O. C. Ord, commander of the Department of Texas from 1875 to 1880, unabashedly opposed the use of black soldiers. Commanding general William T. Sherman explained that he had stationed such troops in Texas because he believed them better able to withstand the state's rigorous climate. Others denied such charges. Lt. Charles J. Crane, assigned to the Twenty-fourth Infantry upon his graduation from West Point, wrote that "though I had not desired the colored infantry . . . I have never regretted my service in that regiment." Elizabeth Custer, that romantic chronicler of army life, defended the qualities of blacks in combat: "They were determined that no soldiering should be carried on in which their valor was not proved," she explained. [18]

No one disputed the high morale in the black regiments. Black cavalrymen, particularly those of the Tenth, carried the nickname "buffalo soldiers" with pride. One Trans-Pecos traveler admitted that while black troops "were ridiculously pompous, they were polite," and focused upon one man, Sgt. John Woodson. Extremely formal with his white officers, Woodson became a different man on detached duty. "It was plain to be seen that Sergeant Woodson was hail fellow with all of his clan." The illiterate Woodson gave his marching orders to a white woman who informed him of their contents. The same writer also pointed out that "we should have felt depressed, escorted by white soldiers; while the four colored men delighted us, as we looked upon them not only as our protectors, but as a company of fellow travelers." [19]

|

| Fig. 6:15. Frederic Remington, one of the West's most famous artists, often specialized in military topics. Here is his classic sketch of a black cavalryman. Photograph from Fort Davis Archives, F-45. |

Composed largely of former slaves, more than one-half of the Ninth Cavalry's enlisted personnel had fought in the Civil War. Racial discrimination made the army an attractive choice for many black males. Steady income, food, clothing, and education seemed especially good to those with only limited employment options; in black communities, military service became a respected career choice. In 1867, while desertion rates for the army as a whole reached an astonishing twenty-five percent, only four percent of blacks deserted. Although the differences were rarely so marked, whites consistently deserted at higher rates than their black counterparts. Indeed, one officer serving in Texas concluded that "if a garrison like the one here could be introduced into every northern town for six months, the opponents of universal suffrage would be few in the legislature." [20]

Official recruiting for the Ninth began with the arrival of its first officers in November 1866. To expedite the process, Col. Edward Hatch set up recruiting stations in Louisiana and Kentucky. The first volunteers had almost no education—the only enlisted man in the regiment able to read and write found himself promoted to sergeant-major. Several officers deeply resented their appointment to the regiment, complaining both of the social stigma attached to such positions and the extra work necessitated by the paucity of enlisted men capable of handling clerical tasks. [21]

Despite such complaints, the Ninth Cavalry sailed from New Orleans to Indianola, Texas, where it disembarked on March 29, 1867. Five companies reached San Antonio on April 4 and camped just north of the city proper at San Pedro Springs. But only eleven line officers accompanied the regiment, far too few to maintain adequate discipline. [22]

Problems were indeed brewing in Lt. Edward M. Heyl's Company E. Having enlisted as a quartermaster sergeant at the onset of the Civil War, Heyl was commissioned a second lieutenant of volunteers in 1862. He was honorably mustered out of the service two years later, only to receive his first lieutenant's bar in July 1866. Like his fellow cavalry officers, Heyl had to pass an examining board before joining his regiment. The board soundly rejected Heyl's first application for a captaincy in November. The prospective officer displayed a fair talent for math, but his scant knowledge of geography and politics betrayed severely limited horizons. In addition to not knowing the location of the Amazon River, Heyl, when asked to "Give the principal rivers of Europe," responded simply, "Nile." "How is the pres. of the U.S. selected by the Constitution?" inquired the board. "He is chosen from the Senate," answered Heyl. [23]

Heyl proved a poor match for the Ninth. A heavy drinker, he often out brutal punishment to his unfortunate command. Just outside of San Antonio his troops rebelled. In a melee between officers and enlisted personnel, one sergeant was killed and two officers wounded. Loyal soldiers rounded up several rioters the following week. In June a court-martial sentenced two ringleaders to death. Another board heard testimony on Heyl's actions, with Merritt concluding that the sadistic lieutenant was "much to blame for cruel not to say brutal treatment of his men." Merritt wanted to conduct a thorough investigation as soon as Heyl had recovered from his wounds. "I am much deceived if many facts do not come to light which will prove him to have been without good sense or sound judgment," added Merritt. With this in mind, the judge advocate general's department remitted the sentences of the enlisted men. They and the other participants ultimately returned to duty. But in an astonishing turn of events, Lt. Edward M. Heyl received a promotion to captain effective July 31, 1867, was transferred to Ranald Mackenzie's Fourth Cavalry Regiment in 1870, participated in nine Indian fights, won three official citations for gallantry, and received an arrow wound during the Red River campaign. [24]

Amidst the controversy, Merritt's column again took up the trail to West Texas. Misfortune still dogged the unlucky Ninth, as two troopers drowned while attempting to cross the Pecos River. It was ironic that such troubles beset Merritt's command; two years earlier, he had led a 5,500-strong division on a model six-hundred-mile march from Shreveport, Louisiana, to San Antonio. He finally led Troops C, F, H, and I, Ninth Cavalry into the crumbling remains of the post on Limpia Creek on June 29. [25]

Other regulars also entered West Texas. By August 1868 elements of the all-black Forty-first Infantry (later merged with the Thirty-eighth to form the Twenty-fourth Regiment) joined the garrison at Fort Davis. Troops then reestablished Fort Quitman as a subpost and base for operations into the Guadalupe Mountains. Federal soldiers remained at Fort Bliss, occupied during the war. In addition, troops began staking out Fort Concho, at the present-day city of San Angelo, by early June 1867. Along the San Antonio road, the army briefly reoccupied Camp Hudson, only to abandon the site in April 1868. And shortly after Merritt rode into Fort Davis, Edward Hatch and four companies established regimental headquarters at Fort Stockton. [26]

The army's reoccupation of West Texas signaled dramatic changes for mail services and local government. Frederick P. Sawyer's struggling mail company hired veteran stageman Benjamin F. Ficklin to manage operations between El Paso and San Antonio. The renewed military presence encouraged the company to establish new stations and improve others along the Trans-Pecos line. Four of these outposts—Barrilla Springs, lying on a barren flat near the entrance to Limpia Canyon, twenty-eight miles east of Fort Davis; the Davis station, a half mile from the post; Barrel Springs, thirteen miles west of Fort Davis and named for the wooden water collection barrels sunk near the station; and El Muerto, the dangerous site nineteen miles from Barrel Springs—were directly influenced by the Fort Davis garrison. Troops from Fort Davis also occasionally guarded two other sites to the west, Van Horn's Well and Eagle Springs. [27]

The typical mail station included two adobe rooms, one used for cooking and eating and the other for sleeping and storage. Hungry travelers could grab some bacon, bread, and black coffee at such an establishment. Quality of accomodations varied; Barrilla Springs had "a very good adobe room, with dirt roof and fair facilities for cooking" but no space for overnight passengers. Eagle Springs was "an old tumble down adobe building"; El Muerto consisted solely of "adobe hovels." [28]

Protecting the mails served as one of the garrison's primary functions. By December 1867 Wesley Merritt was detaching a noncommissioned officer and a handful of enlisted men along with the coaches. The troopers accompanied the stages east to Barrilla Springs or west to Eagle Springs, then escorted return coaches back to Fort Davis. An attack by a hundred Apaches on the eight men guarding an eastbound mail from El Paso quickly tested the system. Lashing his mules into a dead run, the stage driver raced toward Eagle Springs. Both sides opened up a furious fusilade, with Pvt. Nathan Johnson and three of the escort's horses hit during the wild chase. By chance, Capt. Henry Carroll's company of the Ninth Cavalry happened to be camped at the spring; upon hearing the shots Carroll's men deployed to ambush the enemy. As the coach careened wildly toward the station, the troopers unleashed a volley into the unsuspecting Apaches, who promptly broke off the chase. [29]

Although the cavalry had been on hand to save that day, mobile escorts usually offered little protection to the one or two company employees at each station. In response, Merritt dispatched infantry detachments from Fort Davis to guard the positions. By December 1868 eighteen men were at El Muerto and another fourteen guarded Barrel Springs. Content with the beefed-up protection, Merritt wrote smugly: "This arrangement of Guards on this line will I think be a thorough protection against Indians in this direction." [30]

Attempts to organize a county government also accompanied the return of the military. Presidio County, which included Fort Davis, remained unorganized; as such, El Paso County served as the closest judicial center. But growing criminal activity increased the need for local law enforcement. In one instance civilians Samuel H. Butler and Henry Young appeared outside Patrick Murphy's house near Fort Davis. "Come out here you damned old fool and look after your property," shouted Butler. Murphy refused; later testimony suggested that Butler had previously threatened to kill Murphy over a family dispute. The army slapped Butler and Young into irons and sent them to San Antonio on attempted murder charges. But the two prisoners escaped en route to San Antonio, illustrating the problems inherent in depending on such distant civilian authority. [31]

With the military still dominant in Texas, a response came quickly. On September 28, 1868, Fifth Military District commander Reynolds appointed Patrick Murphy as Justice of the Peace and Diedrick Dutchover as constable for Fort Davis. The new civil officers got off to a rocky start. In October Daniel Murphy (no relation to Patrick), who had occupied a 160-acre tract adjoining Fort Davis since 1857, sought a writ of possession order against post sutler Jarvis Hubbell. Murphy had abandoned the property with the federal evacuation in 1861; the defendant, who had moved onto the site in 1867, exhibited a patent secured during the Civil War. The jury decided in favor of the plaintiff. When Hubbell refused to leave, Justice of the Peace Patrick Murphy requested that the military enforce the decision. Post commander Merritt refused, arguing that he needed approval from his superiors before he could interfere in the matter. By coincidence, Indians later killed Hubbell and Murphy took over the quarters by default. [32]

A subsequent incident also pointed up the ineffectiveness of local government. On January 5, 1869, Merritt wanted to organize a military commission to try a civilian laborer named Schmitt, accused of killing a fellow mechanic. Hoping to make an example of Schmitt, Merritt simply ignored Murphy's continued presence as justice of the peace, claiming that civil authority was incapable of meting out justice in the frontier environment. Reasoned the colonel, "there is great necessity of one or more examples of vigorous administration of the law to prevent crime in future." [33]

Unknown to Merritt, military officials were already stirring. Maj. Gen. E. R. S. Canby, former defender of New Mexico against Sibley's invasion and recently named commander of the Fifth Military District, was determined to restore civil order. R. G. Hurlbut succeeded Murphy as justice of the peace on January 6, 1869. Patrick Murphy protested his removal, only to be informed "that this action was taken upon complaint made . . . that you lived at such distance from Fort Davis, as to render you almost inaccessible." Furthermore, Murphy had demanded "extortionate" fees for taking affidavits. [34]

Hurlbut, the county's lone civil officer, found enforcement just as difficult as his predecessor. As Merritt sympathized: "Crimes are not frequent . . . but the distance from the seat of Justice and the neglect of the civil officers who have prisoners in charge has prevented, so far as I am informed, any criminal act from being punished for the past two years." Fifth Military District officials asked Merritt to supply a list of prospective officeholders. The colonel found it impossible to fulfill the order. "There is not a sufficient number of citizens in this county to comply," he explained. [35]

The army took an even more active role in enforcing Reconstruction with the presidential election of Ulysses S. Grant. The day after his 1869 inauguration, the new president returned Joseph J. Reynolds to command of the Fifth Military District. Reynolds began replacing moderate Republican officeholders with those of more radical inclinations, reportedly filling nearly two thousand local government jobs with his minions. He did not act on Fort Davis until February 1870, when he named John Moczygemba justice of the peace, Peter Johnson district clerk, and Peter Donnelly sheriff. Yet the army continued to play a role in local law enforcement. The Davis guardhouse held a variety of offenders (many of whom were discharged soldiers or government employees) on charges that included vagrancy, fraud, theft, assault with intent to kill, and murder. Those accused of serious crimes were transferred to San Antonio when transportation and escort became available. [36]

At the state level, controversial statewide elections established a civil government in Texas acceptable to the national Republican party in late 1869. The military handed over the reigns of government to the staunchly Republican Gov. E. J. Davis the following April. Another attempt to organize a separate Presidio County was soon forthcoming, with Republican party bosses seeking to capitalize upon the pro-Union tendencies of local voters. Separate status for Presidio County would probably mean another Republican in the state senate. In July the legislature authorized Patrick Murphy to head a three-man board to oversee a county election at Fort Stockton. The 1870 measure was ignored, as still another act for the organization of Presidio County followed on May 12, 1871. Daniel Murphy and Moses E. Kelley joined Patrick Murphy as election commissioners. On this occasion, voting was to be conducted at Fort Davis. [37]

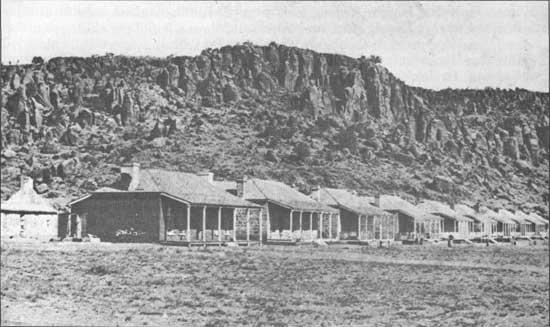

Such efforts again failed to secure separate county status for Presidio. From San Elizario, district judge Simon B. Newcomb claimed that there were fewer than a hundred "legal" voters in the Presidio and Pecos districts combined. The "whole business" was a "dam [sic] fraud," he believed, because the state constitution stipulated that a prospective county have at least 150 voters. Newcomb could not even muster a grand jury. Most voters, in his view, did not want separate county status. Unenthusiastic about making the treacherous journey from El Paso via Fort Davis to Presidio three times yearly, Newcomb personally opposed the measure as well. [38]

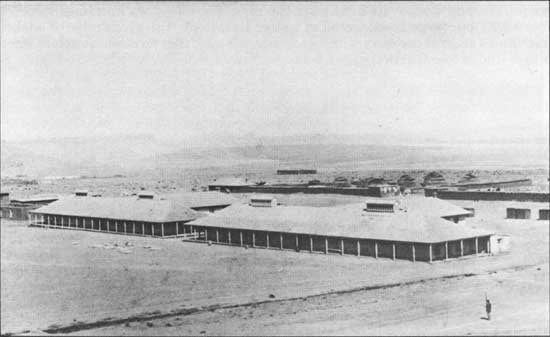

Statewide contests brought more conflict and confusion in 1872. Newcomb passed through Fort Davis on the second day of the election, finding that the registrar had quit after quarreling with election judges. Determined to complete the election, unsupervised judges kept the polls open, thus opening up the results to charges of fraud. As for El Paso, Democrats had organized to oust the Reconstruction regime. Catholics who voted Republican risked excommunication by their parish priests. Himself a Republican appointee, Newcomb declared that he would not hold court again until soldiers could be detailed for his protection. [39]

Despite the best efforts of Republican loyalists, the Democratic party steadily regained control of the Lone Star state, first securing the state legislature and then ousting the Republican Edmund J. Davis from the governorship. In addition to overturning much of the Reconstruction legislation, the Democratic resurgence meant that the army would turn away from intrastate politics in favor of the frontier.

As the political tide shifted, building suitable quarters dominated the life of the new garrison at Fort Davis. In a crucial decision, Lieutenant Colonel Merritt opted to rebuild the post well outside the canyon walls, as several officers had suggested throughout the 1850s. The August 1867 arrival of two steam powered sawmills facilitated the work at the pineries, located twenty-five miles up Limpia Canyon. Sandstone quarries were opened one-half mile from the post and limestone was found thirty-five miles distant. Enterprising soldiers set up a kiln at the site to burn and prepare lime for the mortar used in construction. [40]

Skilled mechanics began arriving in early September. A boiler of one of the steam sawmills exploded a month later, temporarily slowing progress. Still, by December 1 the commanding officer's quarters stood complete save for the roof. One captain's quarters was finished and foundations for the other officers' houses were laid. Seventy thousand shingles, 90,000 board feet of lumber, and 422 bushels of lime had been used so far. Employees included a clerk, two foremen, an engineer, a sawyer, twenty-eight masons, thirty-six carpenters, a wheelwright, a blacksmith, nine quarrymen, a lime-burner, a wagonmaster, two teamsters, and ten laborers. In contrast to the prewar building program, which had depended almost entirely upon the soldiers' extra duty labor, only $1,069.95 had been paid to such workers by December 31; during the same period, civilians had received more than $40,000. Construction costs nearly equaled those at Fort Stockton, which had totaled $43,301 at this time. [41]

Bureaucratic trouble arose in April 1868, for the Quartermaster's Department had not given its blessing to Merritt's building program. Workers had erected several officers' quarters, a guardhouse, a company storeroom, and stables. An enlisted barrack was finished, with three more sets in progress. But the Quartermaster's Department halted construction until July, when it authorized work to begin anew. [42]

Other problems delayed completion of the new post along the Limpia. An officer shortage slowed work efforts. The exhaustion of the old pinery also contributed to the holdup; although the garrison found a fresh timber stand, the road from the new site proved so tortuous that logs were often simply hurtled down the side of a mountain into a nearby wood yard. Incompetent civilian mechanics contributed to the confusion. One worker complained that most of his fellow employees were "loafing a round the lumber pile at the back of the shop." One man, he claimed, was hired because "he fetched fore [four] game cocks and too [two] bull dogs to Captain Moffit [probably Isaac F. Moffat]." [43]

Influenced by racial prejudice, officers at Fort Davis believed their black troops incapable of handling construction work and attempted to rely upon civilian workers despite the problems. Between May 1867 and June 1868 more money had been spent on wages at Davis (more than $72,000) than at any other post in Texas, with Fort Stockton ($68,000) a close second. By contrast, construction materials for Davis, costing just over $11,000, ranked behind similar projects at Concho, Richardson, and Stockton. [44]

However the laconic pace frustrated members of the garrison, construction crept ahead. In January 1869 two hundred civilians were still at work. Four stone officers' quarters stood complete and five adobe houses were ready for roofing. Of the enlisted barracks, four were "well advanced," with one scheduled to be ready for occupation within the month. Miscellaneous structures, including two forage rooms, three mess halls, the guardhouse, the magazine, and assorted quartermaster and commissary buildings, were also progressing nicely. [45]

Army bureaucracy struck again on March 20, 1869, when the department quartermaster suspended all construction save that on two officers' quarters, one barrack, and the commissary. About half of the civilian workers, including most of the masons, left the post. Sharp budget restrictions led the garrison to send home all but twenty of the civilians. A frustrated onlooker described the confusion:

The vast multitude of mechanics gathered here in the past two years, to assist in rebuilding their post, have been dismissed and dispersed; and the role of economy and reform has been fully inaugurated here, by the presiding genius at Washington. To my mind it is a question capable of much doubt, whether, or not, it was genuine economy to abandon the buildings nearly completed to the drenching rains and driving storms, and witness the unprotected adobe walls slowly but surely returning to a shapeless heap of mother earth. Had the work on the unfinished buildings progressed during the past Spring and Summer, the early Autumn would have found the Post completed, and most truly it would have been the pride of the frontier; but, looking upon it to-day, with its bare and roofless walls, the passer-by is forced to exclaim, "what a masterly failure." It is truly a melancholly [sic] abortion of what was intended to tower aloft, as a monument to martial pride and architectural vanity. [46]

With appropriations limited, the enlisted men grimly erected rudimentary shelters which would enable them to abandon their tents. In face of the chronic lumber shortages, the second barrack, like the first, had only dirt floors. Six sets of officers' quarters were also occupied by December 1869. Eighteen civilian mechanics remained at Davis in May 1870, but their small number and the garrison's heavy military duties slowed work to a snail's pace. Commanding general William T. Sherman concluded that "the huts in which our troops are forced to live are in some places inferior to what horses usually have." [47]

|

| Fig. 6:16. Officers' row, ca. 1871. Note the ruins of a barrack from the first fort at the far left. Photograph from Fort Davis Archives. |

At Fort Davis, nine completed officers' quarters formed a neat line running north and south across the mouth of Hospital Canyon by January 1871. All post residents envied the commanding officer's house. The structure measured 48 by 21 feet, with a 41-by-18 foot wing. As originally built, the commander's residence boasted stone walls, shingle roof, and two chimneys. Three captains' quarters also graced officers' row. Like the commanding officer's quarters, the captains each had two front rooms, each 15 by 18 feet, separated by a wide entranceway. Another 15-by-15-foot room served as a rear wing. Five smaller lieutenants' quarters were finished. Each set of officers' quarters had front and rear porches, six pillars, and a separate kitchen in the rear. The one-story buildings were 14 feet high; four were constructed of native limestone, the remainder of adobe; each had a central doorway with two front windows. Eleven other quarters were either under construction or projected for future development. [48]

Six companies of unmarried enlisted men crowded into two barracks, each 186 by 27 feet. A 12-foot passageway separated each barrack into two equal sections, and led to a rear wing measuring 86 by 27 feet. The latter edffice included a mess room, kitchen, and storeroom. The two squad rooms were each 24 by 82-1/2 feet. An orderly office occupied one end of the squad rooms. Two hundred feet behind each barrack lay a communal sink that was 8 by 24 feet and 12 feet deep. Like the officers' quarters, open fireplaces heated the barracks, which had three front windows each. A large ceiling ventilator improved circulation. The unimposing structures had dirt floors, and were altogether "very untidy, dirty, and disorderly," according to the post surgeon. Even so, the barracks must have seemed quite cozy to the cavalry company still living in tents. The married men and laundresses were still without permanent quarters. [49]

The situation had not improved by 1873. Attempts to heat the barracks during a severe January cold spell nearly suffocated the enlisted men. Considering the minus ten degree temperature and the overworked ceiling ventilator, "and that the only means of warming the room, is by one open fireplace, the condition of the men can be readily understood," explained one officer. Needless to say, a wave of sickness accompanied the norther. An inspector's report that March concluded that the enlisted quarters were overcrowded and poorly ventilated. He instructed company commanders to keep the windows open as much as possible. [50]

Auxiliary buildings also dotted the canyon floor. The post bakery had been rebuilt by April 1870. The 40-by-20-foot adobe building stood two hundred yards from the southeast corner of the parade ground. Under the twice-daily inspection of post surgeon Daniel Weisel, the six-hundred-loaf capacity oven "has all the appliances of a first class bakery—and all materials necessary for baking are obtainable—consequently the bread is the best." Weisel boasted: "No complaints are ever made." A subsequent inspector agreed with the effusive Weisel—the bakery was "in very good order." [51]

|

| Fig. 6:17. Enlisted barracks at Fort Davis. Note the construction of a new barrack at the far left. Photograph from Fort Davis Archives. |

During the late 1860s and early 1870s the post hospital remained inadequate. Although planners foresaw a fine stone building as early as November 1867, a few tents clustered deep in Hospital Canyon served as the first infirmary for postwar Fort Davis. In exchange for treatment from Acting Asst. Surgeon Joseph K. McMahon, civilian workers threw up a temporary hospital behind officers' row in the summer of 1868. The 50-by-19-foot adobe structure held fourteen beds. An adobe kitchen and mess room soon fleshed out the ramshackle complex. [52]

By July 1870 the crumbling adobe hospital, "hastily and temporarily constructed," was "almost untenable." Heavy rains made further occupancy doubtful. But although the limestone walls were nearing completion, work on the permanent hospital had stopped in March 1869, along with most of the other projects. "Both the Post Surgeon and the Post Quartermaster have made urgent and frequent presentations regarding the necessity of at once providing a permanent Hospital, but all it seems have been greatly disregarded," objected surgeon Weisel, who found it odd that work on officers' and enlisted mens quarters continued while the hospital decayed. In January 1871 Inspector James H. Carleton agreed that the makeshift structure remained "too small and stuffy" and recommended further improvements. [53]

Behind the temporary infirmary and near the north side of the canyon bluffs lay the post's stone magazine, completed by September 1869. The stone magazine held the garrison's ammunition for small arms, as well as shells for two model 1861 three-inch field guns and cartridges for two .50 caliber Gatling guns ultimately housed at the fort. The garrison erected a second magazine storehouse, this one of adobe, by 1873; both were judged to be of inferior construction. The danger of explosion always worried inspectors, who believed that the first magazine lay too close to the temporary hospital. [54]

Other structures also appeared. The executive office building stood on the north side of the parade grounds. Each of the structure's three rooms had a window and door facing the post grounds. Company and quartermaster stables and corrals lay seven hundred feet behind the enlisted barracks. Adobe walls enclosed each structure. The dimensions of the stables changed frequently; in June 1873 an inspector reported one of the stables as being "in very bad condition." About one hundred feet north and south of the corrals stood the quartermaster's and commissary storehouses, respectively. The quartermaster's warehouse held bedding, tools, fuel, clothing, and construction materials; the commissary housed the garrison's food supplies. [55]

Commanding the south side of the parade ground, the limestone guardhouse drew vituperative criticism. It included a 13-by-15-foot guard room, three smaller cells, and a 15-by-16-foot prisoners' room. In October 1870 post surgeon Daniel Weisel complained of inadequate ventilation for the larger holding tank in October 1870. That month an average of thirty prisoners had been confined, leaving each man only seventy-nine cubic feet of air space. Minimum levels, he argued, should be no less than two or three hundred cubic feet per man. The situation had further deteriorated three months later. As prisoners from forts Bliss, Quitman, and Stockton had been sent to Davis for court-martial, forty-six men packed the little guardhouse. Temporary post commander John W. French ordered the expansion of the prisoners' room and installation of better ventilation for the older structure. Although designers went to great lengths to ensure security during construction, two prisoners escaped in April 1871. [56]

Supplying the garrison also proved a frustrating proposition. The army continued its contract freighting system after the Civil War and advertised for contracts for subsistence and quartermaster supplies (except clothing and equipage) within each military department. Long distances from department headquarters (for most of the postwar era at San Antonio) and ports of entry (Corpus Christi and Indianola) to Trans-Pecos forts like Davis frequently broke down the system. Poor roads, inadequate storage and warehouse facilities, the relative scarcity of locally available supplies, insufficient draft animals, limited federal funding, unscrupulous contractors, and lazy army inspectors compounded the geographic problems. Natural hazards also plagued attempts to supply Trans-Pecos forts; the unsteady pontoon bridge at the Horsehead Crossing of the Pecos River terrified virtually everyone involved in West Texas travel. [57]

As had been the case before the Civil War, seasonal freighting rates varied, with summer costs generally lower than those in winter. A typical freigher, Charles Elmendorf, charged $1.75 per pound per hundred miles from San Antonio to Fort Davis in spring 1871. A leading government contractor was H. B. Adams, a former Confederate soldier and old partner in the Adams and Wickes freighting firm. Whistle-blowing officials frequently challenged the system. Costs could be reduced, they argued, by taking better care of the animals, preventing the overloading of trains, and more diligent inspection of goods on the part of army officials. [58]

From Fort Davis, Colonel Merritt fired off a stream of complaints about the inadequacy of supplies. Even before reoccupying the outpost along the Limpia, Merritt had called upon military authorities to force contractors to make their deliveries "in a reasonable length of time." The problem continued throughout the summer of 1867. In July no vegetables were available at Davis. The poor quality of beans made "it impossible to cook them soft, even after twenty-four hours uninterrupted boiling." The flour was "lumpy and bad"; sugar was "dirty, and of poor quality." He would throw away an entire September shipment of flour, Merritt noted, if anything else were available. As it was, he condemned eighteen barrels of flour and demanded that San Antonio authorities inspect goods more closely before shipping them west. [59]

Merritt continued to scold San Antonio officials. If the costs of transportation were factored in, he argued, stores could be procured at tremendous savings from local suppliers. According to Merritt, such was not the case because the commissary department, eager to show a small savings on its own books, bore only the purchase costs. Cheaper prices elsewhere led commissary officials to purchase goods in the east. The commissary then turned them over to the quartermaster's department, which paid freighting costs out of its own budget. The availability of trade with Mexico bore out Merritt's claim. In 1871, for example, as authorities loosened the centralized contract system, John D. Burgess of Fort Davis secured a contract to supply Fort Concho with 255,000 pounds of barley. [60]

Waste and spoilage claimed many of the supplies bound for Davis, concluded a board of survey following its investigation in May 1872. Lt. H. Baxter Quimby, regimental quartermaster for the Twenty-fifth Infantry, intercepted one convoy east of Fort Stockton and inspected a cask of bacon which had broken open. He found only 768 of the 1,000 pounds of bacon intact. The board concluded that the bacon, along with 263 pounds of rice, 187 pounds of sugar, 129 pounds of soap, and a number of other goods had been lost to "natural waste" along the hard journey. A similar board convened the following November, concluding that broken casks ruined 395 pounds of sugar. This time, however, the officers recommended that the freighter bear a portion of the costs. [61]

Despite the efforts of conscientious officers like Lieutenant Quimby, spoilage continued to claim considerable amounts of provisions. In May 1873 a board of survey found almost 1,000 pounds of potatoes, 25 pounds of bacon, 100 pounds of pork, 20 pounds of mackeral, and a can of salmon had rotted. Worms had infested vermicelli, macaroni, a box of herring, some dried peaches, and ten heads of Holland cheese. Mice had spoiled 3 pounds of tapioca, 3 pounds of laundry starch, and 2 pounds of corn starch. Thirty pounds of butter and more than 10 pounds of lard were "rancid," as was 2 pounds of chocolate. Ten pounds of crackers had gotten wet and spoiled, while dirt and sawdust had contaminated 20 pounds of white sugar, 16 pounds of brown sugar, and a can of yeast. A can of oysters and 8 cans of assorted fruits and vegetables were described as "fermented." Seventy-two pounds of flour were "mushy and sour." [62]

This board recommended that the quartermaster not be held responsible for the losses. Hoping to salvage whatever it could, the officers believed that the soldiers could eat some of the cheese, though "worm eaten" and "crumbled." Furthermore, 140 pounds of beef tongues, "dried so that they resemble hard wood," could be offered for sale to the troops. Recognizing the limited appeal of such foodstuffs, the board advised that the quartermaster tempt unwary bargain hunters by reducing the tongues to half-price. [63]

Fraud and theft also frustrated the efforts of Fort Davis quartermasters. In one instance, the post officer, upon opening a box labeled ginger, instead found ground bark. Inadequate storage facilities forced Lieutenant Quimby to store such less perishable provisions as corn outside the guardhouse. Covering the bags of corn with canvas, Quimby warned the guards to keep a close watch over his stores. Despite his precautions, the corn supply soon dwindled. The only guard who spotted anyone raiding the corn pile was on his way to the latrine, and the thief escaped before the sentinel could summon help. The unfortunate lieutenant also found himself under a board of survey's investigation when the post herders failed to control fifteen head of stampeding army cattle for which he was responsible. [64]

Bad luck, theft, inadequate storage facilities, and nature thwarted efforts to improve efficiency. Fed up with the continued excuses, one group of officers took matters into their own hands. In early 1871 a board comprised of Capt. John W. French, Lt. Washington I. Sanborn, and Lt. William Hugo, found that only 16,852 pounds of the 19,172 pounds of bacon allegedly shipped from San Antonio had arrived at Fort Davis. Exposure and spoilage had ruined that which had been received. Striking wildly, the board held quartermaster officials in San Antonio responsible for the loss. [65]

Repercussions swept through Fort Davis almost immediately. Rumor held that a court-martial of the board's officers was imminent. Defending his subordinates against retribution by the quartermaster's staff, post commander William Shafter assured department officials that "I am well satisfied that they intended to do their duty. I believe their judgment in the case to be erroneous but I do not think they ought to be humiliated by being brought to trial for it." He added that "they are all good officers and I think will be very careful in the future that their recommendations are more carefully made." [66]

The post garden provided sporadic relief to the supply problem. Scurvy and dysentery had swept through the garrison in 1867. Hoping to check the disease, surgeon Daniel Weisel compiled an antiscorbutic cookbook and sent it to the post adjutant. Weisel also called upon the troops to establish a new post garden. In 1868 agricultural efforts went awry, owing to the lack of proper seeds and the lateness of planting. The following year's crop seemed more promising. Post officials hired a civilian, James Feuerty, to oversee the work. The four-acre plot, located about half a mile northwest of the fort along Limpia Creek, produced a mixture of fresh vegetables and melons. Unfortunately, military officials soon fired Feuerty for selling stolen seeds and produce to fellow civilians. [67]

The garrison undertook more extensive agricultural efforts in 1870. Deeming the existing plot too small, the troops established a garden at the old Musquiz ranch. The soil seemed adequate, but dry weather and the scarcity of soldier labor ruined the experiment. The following spring an inspector relocated the post garden closer to the military reservation. "Twelve miles out and back over a rough road is a long ways to go for a head of lettuce or a bunch of radishes," he reasoned. Accordingly, the troops planted a new five-acre garden near the southeast corner of the post in 1871. Worked by various fatigue details, the little farm supplied the post with "all kinds of vegetables including Irish and sweet potatoes and melons." [68]

Similarly, the War Department's attempts to reform the system of post traders clearly affected the quality of life at Fort Davis. Past abuses with the regimental sutler system led Washington officials to allow more persons to enter the military trade. In July 1867 General Orders No. 68 permitted individuals "without limit as to numbers" to sell merchandise at posts between longitude 100° west and California. E. D. S. Wickes, the recently authorized sutler at Fort Davis, suddenly found himself in competition against Patrick Murphy, who had brought along "a considerable stock of merchandise." [69]

Officers at Fort Davis distrusted Patrick Murphy, whose trading with the Confederacy during the Civil War engendered no sympathy among those who had risked their lives for the United States. A council of administration again nominated Wickes as post sutler in August 1867. Lt. Isaac F. Moffett, Ninth Cavalry, asked Murphy to stop selling alcohol to soldiers and civilian employees that same month. If complied with, the petition would have severely restricted Murphy's business. Another trader entered the competition three months later, when A. J. Buchoz requested permission to establish a trading post near Fort Davis. Merritt promised to give Buchoz full government protection, but ordered him not to locate within five hundred yards of any post building. [70]

For the privilege of his official status, Wickes paid a monthly tax of ten cents per soldier. The money supported the post fund, which bought assorted items not covered by official requisition. Officers attempted to protect Wickes in return for his regulated contribution. In May 1868 acting commander Bvt. Capt. James G. Birney warned that the government would not guarantee credit extended to soldiers by nonauthorized traders. In a further attempt to assist Wickes, Colonel Merritt forbade "any and all traders except the Authorized Post Sutler" from selling liquor to the enlisted men or government workers two months later. His order forbidding collection of their debts at the company pay tables further restricted the nonofficial traders. [71]

In the meantime Patrick Murphy had completely antagonized the officers at Fort Davis. The military never approved of his actions as justice of the peace and his loud criticism of Birney's order limiting credit obligations only made matters worse. In a sharp rebuke Captain Birney reminded Murphy that he was responsible only to his military superiors, not to Murphy. The latter promptly lodged a protest with district commander Joseph J. Reynolds. The storm of controversy led Reynolds to call for additional applications at Fort Davis. Three traders—Jarvis Hubbell, R. G. Hurlbut, and C. H. Lesnisky & Co.—won official approval for the work on October 19, 1868. The only recorded applicant not receiving such recognition was Pat Murphy, whose second unsuccessful request was classified as being "totally unfit for the position." [72]

In early January 1869 Daniel Murphy sought recognition for his trading operations at Fort Davis. The army refused Murphy's petition on the grounds that the three authorized sutlers could serve the garrison's needs. After Indians killed Jarvis Hubbell near Fort Quitman, Daniel Murphy was again refused permission to sell his wares at Davis. Instead, Robert W. Hagelsieb joined Hurlbut and Lesnisky & Company as authorized merchants. [73]

Congress revamped the post trader system in 1870. At his discretion, Secretary of War William Belknap was authorized to appoint one or more sutlers per post. Secretary Belknap selected Simon Chaney trader for Fort Davis on October 6, 1870. Chaney arrived by the following January and demanded that post officers evict merchant A. J. Buchoz, located a quarter of a mile northeast of the flagstaff, from the military reservation. Chaney also asked that his private competitors not be allowed to collect their debts at company pay tables. "I am regularly appointed Post Trader and am the only Merchant in this vicinity entitled to full military protection," he argued. [74]

Washington acted accordingly, rejecting the last ditch efforts of Buchoz and Moses F. Kelley to secure the post sutlership. Buchoz claimed to have spent $4,300 in improving his store, which he was now forced to vacate. Although local officers recommended that he receive government compensation, such a onetime payment could scarcely replace all of his future profits. And in accord with post trader Chaney's wishes, department officials severely chastised Bvt. Capt. Andrew Sheridan, then commanding officer at Fort Davis, for allowing civilian traders to collect their debts directly as the men were paid. [75]

Preliminary attempts to expand the size of the military reservation also affected Daniel and Patrick Murphy, when in early 1871 a board of officers recommended that the post encompass a four-mile-square reservation. Patrick had opened a new store five hundred yards behind the stables and two hundred yards from the post hay stacks. Daniel Murphy's post-Civil War establishment lay south of the fort. Except for the Murphys, only "transient Mexican families, deriving their support from the soldiers at the post; many of them by lewd habits—the keeping of dance houses, gambling places, etc." would be affected by the proposed expansion. Pat Murphy, who owned his property, should receive $500 per annum and "be allowed a reasonable time to remove from the reservation." Daniel Murphy was also a landholder but merited more generous treatment. The army should allow Daniel to maintain his current residence and pay him $1,000 annually. "This recommendation is made from the fact that Mr. Dan Murphy and family enjoy deservedly a high reputation for social and moral qualities," advised the board. [76]

At district headquarters, Reynolds disagreed, asserting that both Patrick and Daniel Murphy opposed the proposal. Owing to the still uncertain post boundaries, the Murphys' undisputed title, and the projected cost, Reynolds blocked attempts to enlarge the military reservation. In denying the motion, Reynolds apparently believed the Murphys to be related and thus associated the military's disputes with Patrick to Daniel as well. Reynolds never understood the essence of the problem, claiming that efforts to enlarge Fort Davis "were based upon unpleasant relations existing between the commanding officers and Messrs. Daniel & Patrick Murphy." He added that "considerable correspondence has taken place on the subject (most of it not very good tempered) between the post commanders and Messrs. Murphy." In fact, relations between Daniel Murphy and most officers were good, as witnessed in the board's favorable recommendation. [77]

Troubles with Patrick Murphy finally boiled over in May 1871. Lt. Andrew Geddes testified that about eleven o'clock on the evening of the twelfth, "Mr. Pat Murphy shot at me deliberately, and with intent to kill, the ball from his revolver wounding me in the head." Geddes asked for a transfer from Fort Davis, claiming that Murphy had since threatened to "kill me on sight." Geddes's written complaint stirred Brevet Captain Sheridan, who took Patrick Murphy prisoner the following day. Murphy died later that year, leaving his wife of eleven years to carry on operations at the post. [78]

Problems relating to construction and supply consumed much of the garrison's time and energy. Crucial were the army's efforts to keep pace with developments in armaments and equipment after the Civil War. The Springfield rifle-musket, left over from the war but altered to fire a metallic cartridge, served as principal infantry arm immediately following the Civil War. Testing for a new breech-loading rifle was underway by 1871, when Fort Davis's G Company, Twenty-fifth Infantry, participated in a series of field experiments. During the process, its soldiers carried seven Springfield model 1868 .58 caliber, twenty Springfield model 1870 .50 caliber, twenty Sharps .50 caliber, and twenty Remington .50 caliber weapons. All were single shot, metallic cartridge rifles; repeaters were deemed too expensive, too prone to misfire, and too limited in range. [79]

An 1872 board of survey formally investigated the new weapons and tests, once again selecting the Springfield, modified with the breech-loading metallic cartridge Allin conversion. The following year, production began on the model 1873 .45 caliber Springfield rifles and carbines. Though many complained about the weapon's single-shot capacity, most observers believe it served the army well until 1892, when the War Department adopted the Krag-Jorgensen magazine rifle. Indians, on the other hand, often preferred the Winchester six-shot repeater, despite its shorter range and more limited penetrating power. [80]

The army also adopted the Colt 1872 revolver, a powerful .45 caliber single-action six-shooter. Rival pistols, including the Remington .44 caliber and the Smith and Wesson .45 caliber, offered limited competition. The Hotchkiss "mountain gun" howitzer added long range punch. Light and easily managed, the 1.65-inch cannon was accurate to 4,000 yards. Less successful was the Gatling gun, which could fire 350 rounds per minute by virtue of its hopper-fed ten revolving barrels. The weapon's short range, maddening proclivity to jam, and cumbersome carriage severely limited its use in the American West. [81]

An equipment adoption which most affected soldiers at Fort Davis was the army's standard issue cartridge belt. Army belts initially used black leather cartridge boxes designed for paper ammunition. With the widespread introduction of metallic ammunition, sheepskin lining or cloth loops were added. Despite the remodeling, the cartridges still tended to clatter about and the weight remained unevenly distributed. Several officers, including Capt. Anson Mills, devised belts with loops to hold metal cartridges which proved immensely popular with frontier soldiers. Mills, who ultimately served at Fort Davis, secured official adoption of his prairie belt and made a good deal of money. Of course, budgetary restrictions often delayed the purchase and distribution of new regulation equipment. [82]

But Indian opposition to new migration to western Texas remained a major concern. In addition to the escorts and guards detached to the mail stations, the troops at Fort Davis also launched several expeditions into the Trans-Pecos, with Lt. Patrick Cusack leading the most significant of these patrols in September 1868. With sixty soldiers from K and F Troops, Ninth Cavalry, and a few Mexican volunteers, Cusack caught two hundred Apaches eighty miles south of the post. Cusack claimed that his men killed between twenty and thirty Indians, wounded an equal number, captured a pony herd, recovered two hundred head of stolen cattle, and freed two Mexican prisoners. Two soldiers were severely wounded and two horses killed. On the triumphant return to Davis, pranksters dressed up in their captured booty and pretended to be Apaches. The "Indians" surprised a group working on the rock quarry about a mile from the post. "You can imagine how fast those men ran trying to get back to the post," remembered one soldier. [83]

Despite the success of the Cusack scout, assorted hostilities continued. Indians killed two men near old Fort Quitman in January 1869. That summer they stole a number of stock from the stage station at Dead Man's Hole. The army's failure to check such attacks by Indians or outlaws outraged local citizens. From Presidio John D. Burgess claimed that "the Mexican thieves driven from Fort Davis . . . have taken refuge on my plantation, and are nightly committing depredations on my goat and sheep herds." In his annual report for 1869 Reynolds admitted that Indian raids had been "unusually bold." And in 1870 a strike against Milton Faver's ranch claimed one life and four hundred sheep. A late spring foray against the Fort Davis pinery snatched fifteen government mules. Against such widely ranging attacks, the efforts of the overburdened garrison at Davis proved futile. No less than nine scouts had been launched by January 1871, but no end to the problem seemed apparent. [84]

The mounting frustrations proved too much for Lt. Col. Wesley Merritt, whose calls for more troops fell upon deaf ears. In Merritt's view, it was unreasonable to expect his four or five companies to build a military post, cultivate a garden, protect mail and emigrant travelers, guard the stage stations, and campaign against the skilled Apaches. Furthermore, the wilds of West Texas never appealed to Merritt. He had attempted to escape the arduous duty entirely, unsuccessfully requesting a one-year's leave upon being ordered to the frontier. Arriving at Davis in the summer of 1867, he contracted acute dysentery and was unable to inspect his command in October. [85]

Merritt finally secured sick leave in November 1867. With extensions granted in January and February, the lieutenant colonel stayed away from his station until June 1868. A succession of temporary commanders headed the post during his absence. Upon Merritt's return, he was humiliated in an embarrassing incident the following January. Attempting to leap into a moving wagon just outside his quarters, Merritt "missed his foothold and fell." The wheel of the heavy vehicle crushed his exposed left forearm. As his arm healed, Merritt remained in command at Fort Davis for eight more months. Col. Edward Hatch assumed command in November, a position he would hold for thirteen months. An old friend of General Sheridan, Hatch had compiled an excellent record during the Vicksburg campaign of 1863. A solid officer, Hatch nonetheless lacked the intense ambition and luck needed to excel along the frontiers. He would die in 1889, still a colonel of regulars. [86]

|

| Fig. 6:18. Col. Edward Hatch, commander of Fort Davis in 1870. His uniform reflects the trappings of his brevet rank—major general. Photograph from Fort Davis Archives, AA-15. |

Fort Davis had changed dramatically. Instead of the all-white regular force stationed there before the Civil War, black troops now comprised the garrison. Racial discrimination, along with the bitterness engendered by the army's role in the Civil War and Reconstruction, created numerous disputes between the military and civilian communities at Fort Davis. Still, the two groups obviously depended upon one another—the civilians for protection, law enforcement, and business from the army; the troops for skilled employees, entertainment, and essential services from the nonmilitary population. Cogent observers recognized the interdependency. One officer believed the nonmilitary community, which save for the stage line depended almost totally on the military, "can hardly be regarded as a settlement. . . . Nothing is being done toward a permanent settlement of the country," he wrote. [87]

Political disputes also affected the Fort Davis community. During the height of Reconstruction, Republicans attempted to form a separate Presidio County government in this traditionally Unionist area. However, the sparse population hampered such organizational efforts. With local government so limited, the army was forced to assume nonmilitary responsibilities. Disputes between the army and local officials often resulted from the confusion. Despite the problems, the civilian population at Fort Davis would grow rapidly in the postwar years.

The military had also assumed a more active defence. Soldiers escorted the mails and guarded the stage stations throughout the region. Patrols and expeditions periodically combed the Trans-Pecos, though with the exception of the column led by Lt. Patrick Cusack, rarely caught any Indians. At the fort itself, supply shortages, disputes over land title and the post tradership, and attempts to cultivate a post garden characterized life during the late 1860s and early 1870s. And as had been the case before the Civil War, construction proved a never-ending task, although civilians played a much greater role in this process than they had earlier.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

foda/history/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 13-Feb-2008