|

FORT DAVIS

History of Fort Davis, Texas |

|

CHAPTER EIGHT:

SOLDIERS AND CIVILIANS

Civil-military relations continually provided grist for conversation among residents of Fort Davis throughout the 1870s and early 1880s. Strong-willed officers like William Shafter often antagonized local residents and government authorities. The black garrison also worried race-conscious whites. At the same time, a growing civilian population demanded greater attention from the state government; the widespread use of the Texas Rangers in the Trans-Pecos relieved the regulars of many burdens of law enforcement. In addition, local businesses and contractors were increasingly able to capitalize on the army's presence.

Within the garrison itself, basic material needs continued to dominate daily affairs, as pay, food, and shelter consumed time, thought, and energy. The post sutler remained vital. Post and regimental funds helped finance educational programs, libraries, and bands. Women, including civilians, military dependents, and laundresses, played important roles at virtually every frontier fort, with Davis no exception. Like the soldiers, women struggled to achieve better lives against the challenges of sickness, crime, and despondency. Army policy on the proper location of its western forts also continued to influence routine affairs; appropriations which could ease the hardships of frontier life depended upon changing national perceptions of the western environment and the projected development of railroads.

Health, race, discipline, and punishment remained of special importance to the soldiers throughout the period. Calls for better hygiene at the frontier military establishments led to disputes between medical personnel and line officers. Race became particularly significant at Davis, where a large black garrison and the first black graduate of West Point, Henry Flipper, faced innumerable obstacles which affected not only racial harmony but also the delicate relationship between officers and enlisted men.

Although the army proved a captive market for local merchants, civil-military relations were not always cordial. Few civilians remained ambivalent when dealing with officers like the domineering William Shafter, post commander in 1871-72 and 1881-82. Many respected his gruff efficiency; others found him impossibly rigid. Incidents in late 1871 and early 1872 exposed Shafter's forceful personality. As an example, in 1871 the Presidio County sheriff came to Fort Davis to serve several court orders. During his visit the sheriff took a break at the sutler's store, where he imbibed a bit too freely. Shafter ordered the inebriated civil servant to leave the post. The latter promptly threatened to kill Shafter. The colonel offered to throw the lawman off by force or slap him in the stockade. The sheriff slunk away, with Shafter demanding that he secure special permission to enter the military reservation in the future. Shafter refused to accept the latter's subsequent apology. [1]

A similar incident occurred the following year. On New Year's Day the duty officer ejected several drunk civilian employees from the post billiard room, a private establishment open only to officers and invited guests. At taps Shafter strolled over to the room and found that the civilians had returned. The post commander ordered them to leave; all obeyed except a government-employed saddler. Shafter described what happened next: "As there was no enlisted man convenient to enforce my order I took him by the collar and led him to the door and upon his turning to come in kicked him so as to keep him out." When the man appeared at work the following day, Shafter had him removed. The aggrieved saddler promptly charged Shafter with ill-treatment before the Justice of the Peace. Characteristically, Shafter simply ignored the claim. [2]

Though a strict disciplinarian within camp, Shafter reacted forcefully to any external criticism of his soldiers. In May 1871 private contractor and customs collector Moses Kelley, a Presidio resident who frequented Fort Davis, sharply criticized Capt. Andrew Sheridan in a private letter. By September Shafter had seen a copy of the note and strongly reprimanded Kelley. The latter claimed that he had only sought to defend a widower against Sheridan's "malicious" attack. Kelley hoped the courts could clear up the matter without jeopardizing his chances of securing contracts of flour and hay for the Davis garrison. Shafter responded to this manuever by banning Kelley from Fort Davis. Kelley eventually regained his privileges, but the dispute exemplified the often strained relationships between officers and local figures. [3]

Racial antagonisms widened the gulf between the army and many civilians. Texans sympathetic to the Confederacy bitterly resented what they believed to be federal intrusion during Reconstruction; the continued presence of black troops seemed particularly galling. Even though the region tended to be pro-Union, some found it difficult to accept black soldiers in their midst. Wrote Brig. Gen. Christopher C. Augur: "However senseless and unreasonable it may be regarded, there is no doubt of the fact that a strong prejudice exists at the South against Colored troops." Soldiers of all races occasionally encountered trouble when frequenting local businesses; blacks were often special targets for local toughs and racist law enforcement officers. [4]

In addition to the scraps between soldiers and civilians, the burgeoning community at Fort Davis suffered from increased criminal activity. In 1872 former subsistence clerk O. W. Dickerson, his wife Martha, and five children bolted from the post for San Antonio bearing $2,000 in embezzled War Department funds. In another notorious episode William Leaton (son of old Ben Leaton) killed John Burgess at Fort Davis on Christmas Day, 1875. Burgess had murdered Edward Hall, William's stepfather, who had taken over Fort Leaton. [5]

A veritable crime wave hit the Trans-Pecos in 1880 when members of the notorious Jesse Evans gang robbed several prominent businessmen. Evans, a former associate of Billy the Kid and participant in New Mexico's bloody Lincoln County War, had shifted operations to Texas the previous year. On May 19, 1880, he and two fellow gunmen hit the Fort Davis store owned by Charles Siebenborn and Joseph Sender, getting away with $900 and assorted arms and ammunition. One Fort Davis resident explained their easy getaway: "It is so common for strangers to come in on horseback and well-armed that no one took any account of seeing them around. There are some pretty desperate characters on the frontier," she added, who "do not value their lives any more than you would a pin." [6]

The robberies convinced local leaders to raise a $1,100 reward and to ask the governor for state support. In response Sgt. L. B. Caruthers brought a squad of Texas Rangers to Fort Davis by June 6. Caruthers believed the thieves were congregating along the Pecos River between the Horsehead Crossing and the New Mexico boundary line. They had rendezvoused at forts Stockton and Davis, and Caruthers soon feared that the Rangers would be overwhelmed. The gang's agent in Fort Davis was under indictment for cattle rustling in Shackleford County, but had been appointed jailer and deputy sheriff of Presidio County. The real sheriff "could not get a posse of six reliable men to guard the jail in this county," complained the Ranger. Meanwhile another Ranger squad moved into Davis, bringing with them to the new adobe jail and courthouse a previously captured member of the Evans gang. [7]

Caruthers and five Rangers rode out of Fort Davis on the night of July 1. They spotted their quarry eighteen miles from Presidio two days later. Cornering the outlaws in a rocky mountain refuge, the Rangers forced Evans and two others to surrender after a bloody gun battle. Ranger George R. Bingham lay dead, as did outlaw Jesse Graham. "With saddened heart, we wound through mountain passes, to Davis . . . people here are so happy with our success, they propose to give us 12 or $1,400 for capture," Ranger Edward A. Sieker reported. But the ordeal was not yet over, as rumor held that Billy the Kid was conspiring to rescue his confederates. Ranger Capt. Charles Nevill arrived in early August to reinforce the exhausted squad at Fort Davis. Nevill soon enlisted two local men, bringing his total strength to fifteen. From his first camp at Musquiz Canyon, Nevill swept the region, but found no evidence of new criminal activity. He then moved the Ranger camp to a site called Camp King, eight miles from present-day Alpine (then known as Osmon). [8]

In October the Fort Davis court sentenced Evans to ten years for robbery and another ten years for Bingham's death. The low bail set by Judge Allen Blocker allowed others to go free. The easy terms did not please many local residents; Nevill noted that "Dan Murphy who is opposing Judge B for the legislature is talking very heavy against him. The Judge lost many a vote in this and Pecos counties on account of it." And despite the best efforts of the Rangers, several prisoners escaped. In October three men dug their way out of the Pecos County jail. Others broke out of the Davis "batcave" two months later. Their tarnished record notwithstanding, the Ranger presence allowed the army to relinquish some of its law enforcement responsibilities. [9]

While victimized by such frontier rowdyism, the growing civilian community also grew more able to supply the army's immediate needs. Between 1875 and 1877, for example, at least eleven different bidders secured contracts at the post. The El Paso firms of Charles H. Mahle and S. Schurtz & Brother often provided beef and lumber. Presidio's C. Caldwell secured an unspecified contract in November 1875; that city's Moses E. Kelley and A. F. Wulff won the right to furnish lumber, shingles, bran, and cordwood. Closer to home Joseph Sender filled the hay contract in the fourth quarter of 1876. Peter Gallagher, who had invested heavily in lands around Fort Stockton, sold corn and barley; J. G. O'Grady peddled his hay. A former member of the Third Cavalry who had established a large farm at Fort Stockton, Francis Rooney, sold corn. Fort Davis's Otis Keesey also supplied cordwood. [10]

Even as local commerce flourished, the post trader's efficiency of operations and quantity of merchandise continued to influence life around the military post. Simon Chaney had won the sutler's concession in late 1870. At this time the Secretary of War appointed post traders; though the system was designed to remedy past abuses, Secretary William Belknap brazenly used the trader-ships to dispense patronage and line his pockets. Although the scandal was not publicized until 1876 (forcing Belknap's retirement), officers in the subdistrict of the Pecos had long suspected that the Secretary's appointments had been less than disinterested. [11]

A Belknap appointee, Chaney's operations never satisfied his military customers at Fort Davis. Acerbic post surgeon Daniel Weisel labeled Chaney as "unreliable" and lambasted his store for offering "an inferior stock of goods." In October 1874 a post council of administration reported that Chaney had been absent for over two years. In the official sutler's absence, a brother, A. W. Chaney, had operated the store until the El Paso firm of S. Schurtz & Brother assumed control. Simon Chaney finally asked Secretary of War Belknap to transfer his appointment to his brother. Belknap, noting the stream of criticism against the sutler, assented to Simon's wishes. [12]

But A. W. Chaney proved just as recalcitrant. Following an earlier warning, on January 7, 1875, the post adjutant handed out an ultimatum: "Unless you take measures to procure and keep constantly on hand a good stock of marketable goods and conduct the business in a satisfactory manner," then "after a reasonable time measures will be taken to cause your removal." Post commander George Andrews intervened in March. Despite recent trips to El Paso and San Antonio, Chaney still had not added to his inventory. Andrews, asserting that every man on the post wanted a new sutler, concluded "that the garrison is suffering while Mr. Chaney is pursuing schemes that must prove abortive." [13]

Chaney returned to Fort Davis on May 20 after a visit to his San Antonio bankers, John Twohig & Co., to whom he owed $5,000. Two days after Chaney's return, his store closed. Colonel Andrews recommended that the War Department appoint Joseph Sender, local agent for the firm of S. Schurtz & Brother, as post trader. Sender enjoyed a good reputation among the troops, having extended credit when their pay was overdue. Inspector Nelson H. Davis urgently endorsed such action while at Fort Davis on July 27, 1875. Not only was Schurtz & Brother a reputable firm; Sender had operated a successful store just off the reservation for several years. [14]

Chaney offered his letter of resignation in November 1875, later becoming a county judge and taking up residence at "new Pat Murphy's store" on the outskirts of the fort. Despite the recommendations of both Inspector Davis and Colonel Andrews, on the advice of Rep. John L. Vance of Ohio, Secretary Belknap appointed an outsider, John D. Davis, as the new post trader. Belknap's enforced resignation the following spring led the incoming Secretary, Alfonso Taft, to insist that every post council investigate its trader. Sutler Davis won the support of both the board of officers and commander Andrews, who reported that "no complaints have reached me regarding him . . . either in regard to his manner of conducting his business, or the means he employed to obtain his appointment." [15]

In securing the sutlership, Davis beat out at least four competitors, including the hard-luck Daniel Murphy. Murphy's case is intriguing, especially considering his amiable relations with many officers at Fort Davis, his political support from Texas congressmen John M. Hancock and Edward Degener, and his repeated efforts to secure the position. Murphy, who had campaigned for the job since the darkest days of Chaney's unsuccessful regime, claimed to have Secretary Belknap's verbal support. Yet he found his application blocked, probably because of his indirect involvement in G Company's 1860 mutiny and his former service as beef contractor to the Confederacy. [16]

Whatever the circumstances surrounding his appointment, John Davis again won the unanimous support of a post council held September 30, 1876. Secretary of War James D. Cameron concurred. Davis soon took on a partner, George H. Abbott, and by September 1877 they were leasing a tract just south of the guardhouse for seventy-five dollars a month from banker John Twohig. They expanded the sprawling sutler's compound, which after 1880 included a residence, shed, bar, store, telegraph office, and two privies. As was to be expected, a few criticisms against Davis and Abbott surfaced during their tenure at Davis, which continued through the 1880s. An inspector described their merchandise as "only fair" and the whiskey "poor" in 1878. On occasion, the traders were reprimanded for allowing undesirable elements to use their bar and billiard table. Despite these complaints, Davis and Abbott satisfied the garrison's needs. [17]

The two partners also participated in one of the fort's most bizarre series of marriages. In 1877 Ellen Jane Brady, a step-daughter of Daniel Murphy, married John Davis. While still in her early teens, Ms. Brady had several years earlier married S. C. Hopkins, a nephew of Lt. Col. Wesley Merritt who worked as a carpenter at Fort Davis in 1869 and 1870. She and Hopkins had two daughters in the early 1870s. The Brady-Davis marriage also produced six children. Davis's partner, George Abbott, married one of Ellen's step-sisters, Sarah Murphy, in 1883, thus linking, if only briefly, the partnership through extended family relations. But in what community gossips must have found especially titillating, Ellen later divorced the sutler in favor of her first husband, S. C. Hopkins. [18]

Like the post traders, women played a vital function at the typical frontier post. The census of 1870 reported 134 females present at Davis; that of 1880 listed 345 women at the community and fort along the Limpia. One hundred and six women were not housekeepers; all so listed were black, mulatto, or Hispanic. An overwhelming majority (66) were laundresses. Sixteen seamstresses, 9 cooks, 5 domestic servants, and 2 laborers rounded out the list of common occupations. But not all women at Fort Davis fit these unskilled classes. Three teachers, a teamster, and a tailoress were also present. Jesusia Sanchez received the unceremonious label of "idler." At least two operated their own businesses: Dominga Learma was a widowed shopkeeper, and 36-year-old Manuella Urquedes "keeps a dance house," according to the enumerator. [19]

The federal censuses of 1870 and 1880 (during which time only black units garrisoned the fort) show twenty-nine laundresses or hospital matrons clearly associated with the United States Army. Of these women the census reported eighteen blacks, seven mulattos, and four Hispanics. Their average age was twenty-eight, with the youngest reportedly aged sixteen and the oldest forty-six. Only one of those listed as black or mulatto listed her birthplace as being outside the South or Indian territory. At least fifteen were married to soldiers. [20]

Army laundresses and hospital matrons received government transportation, rations, quarters, and fuel, along with pay rates established by the post council of administration or the surgeon. In 1885 laundresses earned 37-1/2 cents per man per week. Assuming two laundresses per company of fifty, each washerwoman would have netted $37.50 per month. By regulation laundresses collected their debts directly at the pay tables. But long intervals between the paymaster's visits often left the women, like their customers, strapped for cash. In other instances lax enforcement allowed the men to shirk their financial responsibilities. Two laundresses appealed for assistance from the post commander in October 1886. "We are a lone [sic] standing women and thought best to try for your assistance," they explained. Twenty-seven soldiers from one of their companies owed them for five months' work. [21]

At Fort Davis the laundresses occupied a variety of quarters—all of them in poor condition. Insufficient funding and post commanders who placed higher priorities on other projects left the laundresses without suitable habitation. In 1871 they lived in tents behind the enlisted barracks. The women subsequently inhabited a series of small adobe hovels situated throughout the military reservation. The laundresses had taken over an eight-room adobe structure located southeast of the parade ground near the old bakery and storehouses by 1883. Formerly the quarters of the sergeant majors and the principal musicians, the structure had been deemed "past repair" even before the laundresses moved in. In March 1884, although annual inspections again found the site "bad, past repair," the washerwomen remained. Officials demolished the structure sometime within the next twelve months. [22]

Military officials gave laundresses and hospital matrons mixed reviews. Occasionally, the army tried to help those wives in destitute condition by arranging their appointment as laundresses. Surgeon Daniel Weisel labeled his two matrons, one black and the other Hispanic, "efficient" in January 1869. But Lt. William Beck criticized the work of his laundresses a decade later: "I send you the cuff you loaned me," he wrote the son of a fellow officer. "My laundress tarried long in restoring it to a proper degree of whiteness and even now I am afraid that it is not 'good.'" Many believed the laundresses either engaged in prostitution or harbored ladies of the evening. Hoping to clear out a brothel in 1880, the post quartermaster expelled all nonlaundresses and locked up all vacant quarters in the area. [23]

Congress investigated the situation in 1876, with most officers arguing that the number of laundresses could be decreased. Benjamin Grierson believed that the army could reduce from four to two the number of laundresses per company. Col. George Andrews, then senior officer at Davis, declared that he would not allow any laundresses in his company if he were again a captain. Like commanding general Sherman, Andrews thought enlisted men could handle the job. Following the hearings, the army prohibited laundresses from accompanying the troops. Only in 1883, however, did the army strip the women of their government rations. Even so, washerwomen continued to function in at least a semiofficial capacity at frontier posts like Davis for many years. [24]

Army regulations prohibited married men from enlisting, and those who later wished to take wives needed permission from their commanding officers. One survey into this little-understood field has found that of the twenty-one men from H Troop, Tenth Cavalry, who served at Fort Davis in the summer of 1880 and filed for army pensions, five were married at some point during their military service. Four served as noncommissioned officers. Fifteen married enlisted soldiers may be identified from postbellum census returns; they had thirty-one children living in their households in 1870 and 1880. Black troopers often married local Hispanic women despite Texas laws forbidding interracial marriages. [25]

The experiences of married personnel ran the gamut of human experience. Many lived long, happy lives with their wife or husband. But high death rates occasioned numerous remarriages. Guide William Joseph Bishop, for example, married laundress Mattie Howell Adams Collins. Ms. Collins already had eight children by two previous marriages; she and Bishop had four more children. Settling down held few allures for others. Pvt. Daniel C. Robinson, Tenth Cavalry, claimed his bride worked as a servant for one of the officers. To the army, however, the "marriage" was strictly one of convenience designed to allow Robinson to live outside the enlisted barracks. "It appears that they play fast for a while . . . then they play loose for a time." [26]

Others took extreme steps to extricate themselves from their personal unions. Enlisted man John F. Casey married a woman by the name of Pablo after moving to Fort Davis in 1877. He and his wife had two children; he abandoned his family upon receiving his transfer in 1885. Trooper George Goldsby and his wife Ellen had four children, but Goldsby deserted his family at Fort Concho in 1879. A laundress, Ellen remained with her company as it moved from Concho to Davis and ultimately to Fort Grant, Arizona. In 1889 she remarried Pvt. William Lynch—who previously served at Fort Davis—without first receiving a divorce from Goldsby. [27]

A few challenged social traditions. One contract surgeon, though married, was nonetheless "cohabitating" with a Mexican woman. The former wife of Lt. Calvin P. McTaggert, Seventeenth Infantry, married a First Infantry private named Daniel Davis. A United States congressman asked the army to allow Ms. Davis to join her husband in the barracks at Fort Davis. The request shocked the gruff William Shafter. "I have not quarters in the garrison for Mrs. Davis. . . . if she wishes to come here and live in the town adjacent to the post, she can do so, and Davis can see her every day." But Shafter warned that "Mrs. Davis has been the wife of an officer and I think she will find it very unpleasant living near a post." The colonel promised to support the discharge of her husband. But before any arrangements could be concluded, a soldier from another First Infantry company raped Mrs. Davis. Although the Rangers nabbed the villain (who subsequently received the death penalty), only later was Private Davis's discharge secured. [28]

Married enlisted men and their families, other than the laundresses, enjoyed but limited housing facilities. Two buildings, including as many as six rooms each and located northeast of the parade ground, provided a little shelter by 1883. In January of that year noncommissioned officers and their families lived in "two or three dilapidated adobe huts," according to the surgeon. "I would respectfully recommend," he continued, "that decent quarters be built for each soldier permitted to marry, and that these hovels be torn down and their debris hauled entirely away of the reservation." [29]

These quarters proved the scene of lively, if not always reputable, activity. On June 11, 1877, Pvt. Alfred Gradney, Twenty-fifth Infantry, entered the quarters of a Mrs. Henry Ratcliffe, laundress for the Tenth Cavalry. Finding her absent, an enraged Private Gradney kicked over a table filled with crockery, "thereby . . . disturbing the good order of the garrison." And a chief musician stormed into Sgt. James Cooper's house, complaining to Mrs. Cooper about her husband. Seizing a fistful of hair, the musician dragged Mrs. Cooper outside before a guard rescued her. Despite the offense, post officials quickly returned the musician to duty. The sergeant's wife had no recourse but to file a formal grievance with department officials. [30]

Officers' wives comprised a completely different social class at every frontier station. At Fort Davis ten of the twenty-eight officers listed in the 1870 and 1880 censuses had wives living with them. Eight of these families had children; the officers' youngsters totaled ten in number. These elite dependents formed close friendships among one another, rarely interacting with the lowly laundresses or enlisted men. In keeping with Victorian mores which often relegated women to second class status, they cared for their children, consoled their husbands, sewed, and discussed the latest fashions and military affairs. Despite their prominence, the officers' wives enjoyed no official army recognition—no rations, no protective regulations, no transportation. Embittered ladies found the lack of official status "notorious." [31]

For officers, finding a wife or woman companion at Fort Davis proved a welcome pastime. Daughters of fellow officers seemed likely targets for prospective suitors. Lt. Leighton Finley, a Princeton graduate, kept a list of "girls I have known." The young lieutenant rated his female acquaintances as to the "degree of influence they exercised over me." Of those at Fort Davis, Mary Shafter, daughter of the colonel, rated a four. One of Daniel Murphy's daughters, Kate, who married the Tenth Cavalry's John B. McDonald, merited a five on Finley's scale. May Beck (daughter of William H. Beck), earned a three in 1884, but was upgraded to a seven in 1886. [32]

Others were more successful than Finley. Lt. Millard F. Eggleston, Tenth Cavalry, married Miss Gertrude Gardner, daughter of Asst. Surgeon William H. Gardner, at the Fort Davis chapel in 1884. Two years later Miss Josephine Fink, daughter of Capt. Theodore Fink, a member of the antebellum fort's garrison, wed a civilian at her mother's hotel at Fort Davis. Officers found the Murphy clan especially enticing—four of the Murphy girls married officers. [33]

But frontier life could be horribly cruel, especially when it came to bearing children. Although generally enjoying the assistance of a surgeon, midwife, or other post females, the perilous prospect of childbirth at a military post troubled most pregnant women. Annie Nolan, wife of Capt. Nicholas Nolan, moved to Fort Davis shortly before giving birth. "Though I ought not to complain, this post being really lovely and home like," Mrs. Nolan freely admitted that she would rather bear her child among her friends at Fort Concho than among strangers at her new house. In so doing, she undoubtedly echoed the fears of every prospective mother on the western frontier. [34]

Caring for newborn babies tested even the best parents, with mothers bearing the brunt of infant care. Lt. James K. and Mary Swan Thompson handled the initial problems extremely well. Having put the infant to sleep, Mary once allowed that "all my nervousness has gone. . . . I've not an ache or pain anywhere." Their little boy received typical upper class gifts, including toys, clothes, socks, and gold buttons. With the baby awakening at regular hours to nurse, things could scarcely have been better. But four weeks later, an exhausted Mary Thompson confided to her mother and grandmother:

This is the first afternoon I've had a moment to myself in I can't tell when. . . . The baby is so wakeful all day long and keeps me so busy—but today he has just succeeded after trying for nearly two hours in howling himself to sleep. . . . It is two o'clock now—and so far today he has slept just fifteen minutes, after his bath this morning, so you can see he is an incessant scamp—and there is nobody to take him but myself. So please stop scolding me about not writing. [35]

Sickness, disease, and death also affected women at Davis. Maj. Zenas R. Bliss's wife suffered from a severe eye ailment in the spring of 1874. The post surgeon could not hope to provide the necessary treatment. Yet Bliss, as acting post commander, had to wait three weeks for his leave because the permanent commander, George Andrews, was also away from his post. Andrews's wife Emily had died in 1873, and the colonel returned east to settle her estate, not returning until the fall of 1874. While there, he married Emily Kemble (Oliver) Brown, a widow with a young daughter from her previous marriage. [36]

Fort Davis was the scene of one of the military's most bizarre set of personal relationships. 1st Lt. Louis H. Orleman, his eighteen-year-old daughter Lillie, and Lt. Andrew Geddes were all stationed at neighboring Fort Stockton in February 1879. On the twenty-first the three rode the stage to Fort Davis, where they remained for five days before returning to Stockton. In a subsequent court-martial, Lieutenant Orleman charged Geddes with endeavoring "to corrupt" Lillie "to his own illicit purposes," attempted abduction, and conduct unbecoming an officer. Orleman claimed Geddes had pressed Lillie's knees between his [Geddes's] during the coach ride under the cover of a blanket. This was while the father held his daughter in his arms. Tearfully, Lillie also accused Geddes of repeatedly propositioning her at Davis and Stockton. [37]

Geddes mounted a vigorous defense, claiming that he had seen Orleman "having criminal intercourse with his said daughter" one afternoon at Stockton. Geddes added that Lillie had told him that this had been occurring for the past five years. He also presented the affidavit of a fellow passenger, stating that he saw Lieutenant Orleman "fondling with the breast of his daughter." Other witnesses reported the commonly held belief that Orleman and his daughter slept in the same bed. After sixty-eight days of sensational testimony at San Antonio, the court found Geddes guilty, cashiering him from the service and sentencing him to three years in the penitentiary. Pres. Rutherford B. Hayes accepted the judge advocate general's recommendation that the court's ruling against Geddes be overturned. Geddes was eventually dismissed from the army on another charge in December 1880; ironically, Lieutenant Orleman, his health broken, had retired thirteen months earlier. [38]

Disputes between surgeon and commanding officer, a recurring problem at frontier military posts, also marked Fort Davis after the Civil War. These conflicts stemmed from personality clashes as well as systemic defects. In December 1868 Asst. Surgeon Daniel Weisel took charge of medical affairs at Fort Davis. A thirty-year-old native of Williamsport, Maryland, Weisel was on his first independent station. His bride of less than a year, Isabel Walters Weisel, accompanied the young doctor. Weisel's two predecessors at Davis, J. H. McMahon and Joseph Taylor, had been acting assistant surgeons under private contract. Since virtually everyone in the army distrusted contract surgeons, who had not passed the army's rigorous medical examinations, the garrison extended Weisel a warm welcome. [39]

|

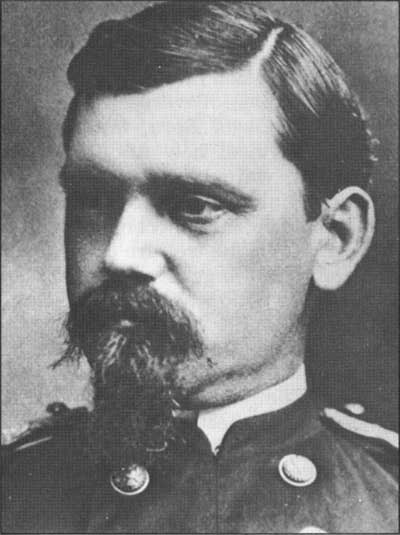

| Fig. 8:25. Asst. Surgeon Daniel Wiesel, who took over the Fort Davis Hospital in 1868. Photograph from Fort Davis Archives, AA-64. |

The new doctor immediately proved his worth. His efforts to collect locally available watercress, to make sauerkraut, onions, pickles, and citric acids part of the regular diet, and his unceasing support for the post garden prevented the recurrence of scurvy, which had broken out the previous spring. To reduce the rates of diarrhea and dysentery, Weisel encouraged the men to bathe regularly in Limpia Creek. He also suggested that rings and parallel bars be set up to encourage more exercise. Weisel reasoned that "innocent and healthful amusement" would reduce the average soldier's "inducements to seek pleasures farther away and more injurious." [40]

Seeking to improve health, the War Department directed post surgeons to inspect sanitation facilities in late 1869. Weisel welcomed the challenge. To his traditional tasks of overseeing the post hospital, making sick calls, and forwarding specimens of flora, fauna, and diseased organs to the Army Medical Museum, Weisel now undertook regular inspections of the post's physical properties, water supply, and cooking equipment. As always, the surgeon remained liable for service on boards of survey and courts-martial. He was also responsible for the post cemetery, and often served as post treasurer. In addition he checked on the welfare of troops stationed at Davis's various subposts. The surgeon was to suggest sanitation and general health improvements to the post commander, who was obliged to hear out the medical man's reports. [41]

A matron, a cook, and two male nurses assisted Weisel, with the latter positions filled by enlisted personnel. He also enjoyed the service of Acting Asst. Surgeon Thomas Landers during much of his three and one-half years at Fort Davis. One inspector recommended the transfer of one of the two doctors, as "these two gentlemen really have but very little to do." Whatever the case, Weisel oversaw a dramatic improvement in the health of the command. During his first year at Fort Davis, while the garrison's average strength fell by ten percent, the number of troops taken sick fell by forty-two percent. Malarial fevers were reduced from 48 to 32; cases of diarrhea and dysentery from 231 to 105; scurvy from 47 to 8; deaths from 17 to 2. Only the incidence of venereal disease, which increased from 2 cases to 9, showed a perceptible growth. [42]

General health continued to improve as Weisel hounded line officers to show greater concern for the physical welfare of their men. When comparing monthly averages of 1869 and 1871, Weisel proudly reported that the number of wounded or sick dwindled from 26 in 1869 to eight in 1871. Length of illness also declined—those remaining sick from the last report fell from nearly 11 to 5. Fort Davis statistics compared favorably to national averages. Between January 1869 and May 1872, the military's overall death rate was 17 per 1,000; at Fort Davis, it was only 6 per 1,000. The number of medical discharges at Davis, 21 per 1,000, was far less than the army's average of 35.5. And the garrison's sick rate of 60.2 percent remained less than one-third of the national average of 200 percent. [43]

But not everyone admired the young surgeon. Many remained skeptical of Weisel's abilities; others expected him to be on call twenty-four hours a day. Capt. Charles Hood filed an official complaint against the doctor on March 1, 1871. Although Hood hinted at several incidents, the specific charge was Weisel's "official delinquency" in refusing to pay him a visit for a sore throat. According to Hood, Weisel never responded to verbal requests sent by orderlies, instead demanding that every complaint be written. Weisel responded angrily to Hood's "whimsical, unfounded, and entirely uncalled for" grievance. "I did not tell Captain Hood that I paid no attention to verbal messages," wrote Weisel, who simply refused to accept such requests delivered by enlisted personnel. [44]

Weisel also had a falling out with post commander George Andrews. In the post's official medical record, the doctor complained that while Edward Hatch and Wesley Merritt had kept the reservation clean and sanitary, more recent commanders had been less conscientious. The general police was "not done as regularly as it should." And because of a shortage of disinfectants, particularly lime, the post sinks were "in a very bad condition." Fellow officers must cooperate, complained Weisel, if he was to do his job properly. [45]

Upon Weisel's departure, Colonel Andrews investigated the post. He went over the fort's books in painstaking detail, blasting the subsistence department for erratic and inconsistent record-keeping. Pages had been torn out and entire volumes were missing. But the colonel saved his sharpest attacks for Assistant Surgeon Weisel's hospital records, which, according to Andrews, "have been irregularly and improperly kept." Weisel had used the medical history "as a means of expressing personal spleen." When Colonel Shafter had tried to look at the book, it had mysteriously disappeared, not to resurface until Weisel handed it over to the incoming surgeon. Andrews maintained that Weisel had in the meantime changed or erased several of the most critical passages. [46]

|

| Fig. 8:26. Drawing © by Jack Jackson. Originally published in Robert Wooster, Soliders, Sulters, and Settlers (Texas A & M University Press, 1987), p. 43. Reprinted with permission. |

Andrews gleefully immersed himself in the minute details of Weisel's sloppy accounting. Enlisted men had kept most of the books and Weisel had failed to check their math or oversee their work. In fact, the surgeon discharged two of his stewards for disobedience—both probably embezzled funds from the hospital, although Weisel's poor arithmetic prevented him from discovering their worst infractions. Andrews ferreted out numerous discrepancies, of which the misappropriation of medicinal alcohol proved most serious. The colonel calculated that Weisel's liquor requisitions far exceeded that actually dispensed to patients, with the amount of alcohol on hand not nearly making up the difference. [47]

The status of the hospital remained a sore spot which helped explain the constant bickering. Weisel left the following description of the temporary infirmary in December 1871:

Despite the constant patching of the roof with mud, an ordinary rain penetrates it as a sieve; and in moderately cold weather, by reason of there being no windows in the building, it is impossible to sufficiently warm it. For windows [there] have been light wooden frames, covered with cotton cloth furnished from the Hospital, and these are now in a very dilapidated condition. There has never been a single pane of glass in the Hospital, and during a recent severe snow storm, it was necessary to cover these cotton windows with blankets to assist in warming the ward—and it was not until recently, that the cotton doors, similar to the windows being entirely destroyed, were replaced by rough wooden ones. The kitchen . . . was built entirely by the Hospital attendants of damaged adobes, that could not be used in any permanent buildings, and old lumber. It, like the remainder of the Hospital being only built for temporary purposes, is rapidly decaying. [48]

Weisel had repeatedly asked Colonel Shafter to requisition new hospital funds. Shafter, however, vetoed Weisel's suggestions. The commander believed the building had "answered the purpose very well for several years and is as good now as it ever was." He later rationalized his decision: "Hospital is built of adobe, mud roof and dirt floor. For a building of this description [it] is in fine order." [49]

Shafter's departure removed a major obstacle to hospital remodeling. Maj. Zenas R. Bliss, who commanded Fort Davis for twenty months between 1873 and 1876, supported efforts to improve the infirmary. Flooring was finally added during the spring of 1873. That September Bliss forwarded plans for a twenty-four-bed hospital, based on the Surgeon General's blueprints, to departmental headquarters. Cost estimates exceeded eleven thousand dollars. As officials examined the proposal, torrential rains on November 2 and 3 forced attendants to move patients from the leaky hospital back to their barracks. Requests for tarps to cover the roofs fell upon deaf ears. [50]

Plans for a big new twenty-four-bed structure finally won the approval of departmental medical director L. F. Hammond, Asst. Q.M. Gen. Samuel B. Holabird, and department commander Christopher C. Augur. However, in the sixth endorsement to the proposal, an officer in the divisional quartermaster's office claimed that a twelve-bed hospital was sufficient. Division commander Phil Sheridan also opposed the measure. As the Fort Davis climate was "very healthful," wrote Sheridan, "I consider a twelve bed hospital abundantly large for the garrison." [51]

In September 1874 surveys for the smaller twelve-bed infirmary were concluded following the return from leave of Colonel Andrews. Construction started on October 26. Some two hundred yards behind officers' row, the adobe structure boasted a stone foundation with reinforcements at each corner. The main building stood 63 by 46 feet, with a 41-by-27-foot wing to the north and a 19-by-17-foot southern addition. The nine-room complex had a tin roof. Construction was not, however, without complications. The Treasury Department's withholding of funds temporarily delayed work in January 1875; on March 5, 1876, strong winds ripped away nearly a third of the roof. [52]

Asst. Surgeon Charles S. DeGraw headed the post's medical operations from November 1872 to September 1876. He and his acting assistant surgeons S. S. Boyer, Ira Culver, and Joseph Harmar administered to a wide range of ills. In May 1873, for instance, DeGraw noted that he spent most of his time treating Hispanic civilians, "as no other medical attendance could be procured at a distance of 200 miles." Gonorrhea, diarrhea, rheumatism, and neuralgia proved among his most common diagnoses. Scattered cases of smallpox were reported in December 1874, with the dread disease threatening to reach epidemic proportions the following spring. Pvt. Alpheus Rankin of D Company, Twenty-fifth Infantry, the daughter of one of DeGraw's servants, and an unnamed citizen all caught the virus. Fearing its further spread, DeGraw isolated the patients "a considerable distance from the post." By August, however, the scare had ended. [53]

Violence occasionally shattered the post's reverie. While fooling around with a carbine, Pvt. Jesse Warren of the Ninth Cavalry accidentally shot and killed fellow trooper David Boyd. During the Independence Day ceremony in 1873, Pvt. John Jourdan of G Company, Twenty-fifth Infantry, lost the sight in his right eye when his weapon prematurely discharged. Another private killed himself while cleaning his rifle three years later. In 1874 DeGraw discharged a private for injuries stemming from a mule's powerful kick. Following a July 4 celebration in 1876, a civilian murdered musician Charles Hill. Later that year, Cpl. Abraham Lincoln, Twenty-fifth Infantry, was found dead near the post, a suspected victim of foul play. [54]

Asst. Surgeon Henry P. Turrill succeeded DeGraw in October 1876; in turn, Turrill was followed by Ezra Woodruff in June 1877, Joseph B. Girard in May 1879, and Harvey E. Brown in April 1881. All save Brown were assistant surgeons, equivalent to line ranks of lieutenant or captain. Turrill won few friends by calling for more thorough policing of the notoriously unsanitary company sinks in only his second month there. Likewise, Girard bitterly complained about the removal of his best hospital cook, Pvt. Alfred Russell, to serve Capt. Thomas Lebo. In a much heralded exhibition, Woodruff secured an ambulance in December 1878. But while ten admiring passengers road tested the new equipment, one of the rear wheels collapsed. Doctor Woodruff diagnosed the trouble as "weak timber" in the spokes. [55]

The case of Surgeon Brown was more tragic. A twenty-year veteran who won his majority in February 1881, Brown showed up drunk to a court-martial of which he was president six months later. Reluctantly, post commander Shafter placed Brown under arrest, but hoped to avoid pressing charges against the doctor. "His ability is not questioned," Shafter reasoned, "but besides his liability to get drunk, he is in very poor health, and is not, in my opinion, fit to be in charge of a large Post." He recommended clemency for Brown, whom doctors diagnosed as having tuberculosis, coughing, indigestion, hemorrhaging, and "general debility and depression of spirits." Departmental medical director Joseph R. Smith made a brief inspection on September 15. Two months later, a new assistant surgeon replaced Brown at Fort Davis. [56]

Land ownership remained an issue of dispute throughout the era. Since the Lone Star state retained control of its public domain, the army was forced either to lease or purchase sites for its posts. The military's presence inevitably increased property values. Wherever the army went, speculators moved also, buying up potential sites and then renting them at high rates to the federal government. One member of the House of Representatives ruefully observed that "the lands at these places are of little value till occupied by the military authorities, when they suddenly become valuable and their owners exact high rents." Exasperated by the lingering problem, Secretary of War Belknap explained that "in consideration of the protection afforded the State of Texas by the presence of the U.S. troops, I think it should use its utmost power to provide suitable sites for forts." Belknap warned that "unless such assistance be rendered, the [Federal] Government may be compelled to withdraw troops from Texas altogether." [57]

Threats notwithstanding, all parties knew that the army would not abandon Texas. In 1871 Secretary Belknap and Q.M. Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs asked Congress to empower the War Department to buy land within the state. The House Committee on Military Affairs reported the bill favorably in January 1873. With annual rents ranging from $500 for Fort Davis to $2,500 for Fort Bliss, paying the high leases seemed foolish—it would be more economical to purchase the property outright. Congress formally approved the measure in March. [58]

Pursuant to congressional instructions, a military board of survey met in San Antonio in November 1873. Including Lt. Col. Samuel B. Holabird, Maj. Albert P. Morrow, and Capt. William T. Gentry, the board noted that the present lease for Fort Davis ran for fifty years. Negotiations opened as landowner John James asked $15,000 for all tracts leased to the government. Seeking to reduce costs, the military board excluded all lands except the 640 acres upon which the post stood. Called upon to offer a new amount, James again demanded $15,000. After both Morrow and Gentry visited Fort Davis, the board set $9,000 as a fair price for the military reservation. The board noted the government's previous investments and "very substantial character" of the buildings in justifying its assessment. In addition to the recommended purchase of Davis, the board called for $3,840 for nearby Fort Quitman and $12,000 for Fort Stockton. Suggested acquisitions in Texas totalled $106,360. [59]

Following the board's recommendations, Secretary Belknap suggested that the army divert the $100,000 already appropriated for purchasing a San Antonio depot to buy the other positions. But in command of the sprawling Division of the Missouri, Phil Sheridan added a note of caution. As he explained, "The rental of the ground is in most cases reasonable. The purchase will cost a good round sum, and it may soon be necessary to change many of the posts, especially if the Pacific Railroad goes on." [60]

Department commander Christopher C. Augur concurred with Sheridan's reasoning in 1874. Augur believed the posts along the Rio Grande should be purchased outright for reasonable prices. But all forts north of Clark and Duncan should be located along the Southern Pacific Railroad, projected to undergo major expansion in the near future. Augur thus believed it premature to buy any sites which the railroad might make obsolete. General Sheridan likewise supported the immediate acquisition of Rio Grande posts, but entertained "grave doubts of the propriety . . . of the purchase of the sites on the northern frontier, namely, Forts Richardson, Griffin, Concho, McKavett, Stockton, and Davis." In particular, Sheridan predicted that "Forts Davis and Stockton will go to the Pecos River." [61]

While endorsing these conclusions, Sherman refused to rule out purchases along the western and northern frontiers at "a reasonable price." Congress refused to divert the $100,000 allocated for the depot at San Antonio to other sites in Texas. But to the delight of military officials, it authorized additional monies for forts Brown, Duncan, and Ringgold. As negotiations for these Rio Grande posts began, Congress also investigated calls by General Sherman, newly appointed Secretary of War George W. McCrary, and new commander of the Department of Texas, Brig. Gen. E. O. C. Ord, for additional forts along the Mexican border. [62]

Ord championed the idea of erecting another permanent position in the Big Bend. The mouth of the Devil's River or the city at Presidio held strategic importance. In addition, Ord estimated that sixteen army companies in Texas had no permanent quarters; he could easily divert forthcoming construction monies to new positions along the Rio Grande. Similarly, department officials began investigating the possibility of establishing a post near San Carlos to block Apache raids from Mexico in early 1878. Far from the "grog shops and disreputable places" of any towns, such an environment would also foster good discipline. [63]

Congress deferred action on the additional Rio Grande posts until 1880. Finally, with the support of Pres. Rutherford B. Hayes, former Secretary of War McCrary, generals Ord and Sherman, and both House and Senate Committees on Military Affairs, a measure passed on April 16 appropriating $200,000 for the purchase of sites "on or near the Rio Grande." As one congressman reasoned, such action would forestall any disturbances which might lead to war between the U.S. and Mexico. He also reminded his fellow representatives of the government's obligation to protect "the life and property of every American citizen." [64]

Strangely, however, the army failed to move. As one clerk informed Secretary of War Alexander Ramsey five months after the appropriation: "The expenditure of $200,000 for sites of posts and buildings in Texas does not appear to move forward. This office is without knowledge of the places chosen or plans and estimates for the erection of buildings." In its response the army in Texas emphasized the disruption caused by the Victorio campaign throughout that summer. Notwithstanding that preoccupation, Capt. William R. Livermore had attempted to examine the Trans-Pecos. [65]

In November, General Ord submitted his official rejoinder. Having located no likely spots along the Rio Grande between the mouth of Devil's River to Presidio, he believed Congress should remove the restrictions limiting funding to new positions "on or near the Rio Grande." In a January 1882 response to a House inquiry, Secretary of War Robert T. Lincoln again explained the failure to implement the act of April 16, 1880. "Points for the location of forts other than on or near the Rio Grande are deemed more desirable and better adapted to the purpose contemplated in the act," argued Lincoln. Congress relented, and on June 30 granted the army permission to use the special appropriation on posts anywhere in Texas. Although title to Fort Davis would remain largely in private hands, subsequent commanders at the post on the Limpia sought to capitalize on these newly available funds. [66]

As negotiations with Congress proceeded, garrison life at Fort Davis remained roughly comparable to that before the war. Fatigue duty, drills, patrols, and construction took up the majority of the garrison's time and energies. Everyday tasks kept the troops "well-occupied," assured one Fort Davis surgeon. The chief difference came in the composition of the enlisted men. Once the exclusive purview of whites, the Civil War had opened military service to thousands of blacks. [67]

Reflecting the pervasive effects of racism in the nineteenth-century United States, racial incidents occurred on a regular basis at Fort Davis. Those who tested the color line risked ostracization or intimidation. Pvt. William Layton deserted rather than face action for his involvement "in a most disgraceful affair with a colored soldier." Pvt. Charles M. Douglas, K Company, Sixteenth Infantry, became the target of an unending stream of racist jokes because of his dark complexion. Following a series of fist fights at the post pinery, Douglas finally cracked under the pressure. As a reviewing officer explained:

He defiantly proclaimed himself a "nigger" and . . . began to associate exclusively with colored men. This aroused a bitter feeling against him in his company and they have no doubt treated him cruelly telling him that as he had confessed himself colored he must get out of the company. He is now in a state of frenzy bordering on mental aberrration wants to transfer to a colored company says he will never serve in his own but will desert as soon as he can if returned to it. Meanwhile [he] will fight no more with his fists but will kill some of them or they shall kill him. [68]

Fort Davis was also the scene of two spectacular racial confrontations. The first occurred about one o'clock in the morning of November 21, 1872. Lt. Frederic Kendall, Twenty-fifth Infantry, was away from the post; the sound of breaking glass outside her bedroom window awakened his wife. Mrs. Kendall raised the curtain to find Cpl. Daniel Talliferro, Ninth Cavalry, trying to force his way inside the house. After a frantic warning Mrs. Kendall seized a revolver and killed the intruder with a bullet through the head. [69]

News of the incident spread like wildfire. The idea of a black enlisted man attacking a white officer's wife threatened the foundations of military society. Shocked by the alleged challenge to white womanhood, post commander George Andrews claimed that in the seventeen months he had commanded black troops, attempts had been made to enter officers' quarters at forts Duncan, Stockton, Davis, "and I think McKavett and Concho." Five such break-ins had occurred at Fort Clark. Of the Kendall-Talliferro incident, Andrews claimed that this "was the second attempt within three weeks at this post; the first one was made while an officer was absent from his quarters for only ten minutes to attend tattoo roll call." According to Andrews, married officers were reluctant to leave their families alone after dark. Detached service now became "a positive cruelty." [70]

In the view of Andrews, married enlisted men shared these fears. Musician Martin Pedee, Twenty-fifth Infantry, had recently been accused of attempting to rape the white wife of a fellow corporal. The lack of army retribution in the Pedee case worried Andrews. "When the result of the case was published, one and all exclaimed 'what shall we do to protect ourselves,'" he noted. In response to Andrews's account of the incident, Judge Advocate Gen. Joseph Holt concluded that Mrs. Kendall had been justified in shooting Corporal Talliferro. In the Pedee case, however, the accused assailant's identity had not been established. [71]

Racial tensions mounted. Black troops at Fort Stockton nearly mutinied in response to a surgeon's alleged mistreatment of a sick patient in July 1873. Another ugly racial confrontation occurred at San Antonio. "The fact cannot be disguised, that there is anxiety at every post garrisoned exclusively by colored troops," concluded the normally fair minded department commander, Christopher C. Augur. "They are so clannish, and so excitable—turning every question into one of class, that there is no knowing when a question may arise which will annoy in a moment the whole of the garrison against its officers not as officers, but as white men." [72]

Yet another incident involved West Point's first black graduate, Lt. Henry O. Flipper. Born in Thomasville, Georgia, in 1856, Flipper was educated at Atlanta before going to West Point. Despite being shunned by the other cadets, the young man was graduated fiftieth in a class of seventy-six in 1876. He took a commission in Benjamin Grierson's Tenth Cavalry and served at Fort Sill. There Flipper befriended his captain, Nicholas Nolan, and Nolan's sister-in-law, Mollie Dwyer. Flipper and Miss Dwyer often rode horses together, a practice they continued when the company was transferred to Fort Davis in 1880. [73]

Flipper encountered a series of difficulties at the post on the Limpia. Post commander Maj. Napoleon B. McLaughlin seemed to Flipper "a very fine officer and gentleman." But most of the other officers were "hyenas." Only Lt. Wade Hampton, nephew of a former Confederate general, visited Flipper's quarters on New Year's Day, a traditional time of celebration and gaiety at the frontier communities. At Fort Davis, Flipper served as post quartermaster and commissary of subsistence. Even the most meticulous officers found themselves entangled in the morass of paperwork entailed in both jobs. The lieutenant proved no exception. In January 1881 guide Charles Berger deserted. On the quartermaster's payroll, Berger had served only the first week of the month, but Flipper had charged the whole of January (sixty dollars) to the government. Major McLaughlin assumed responsibility for the incident when a board of inquiry failed to reach a verdict. [74]

Colonel Shafter again took over as commander in mid-March 1881. One onlooker had previously observed that "all the other officers are mad" at Flipper's having been placed in a position of authority. Shafter reshuffled the post's staff, replacing Tenth Cavalry officers with officers from his own First Infantry Regiment. He removed Flipper from his quartermaster's responsibilities, retaining the young lieutenant as commissary officer pending the arrival of a suitable replacement. He also kept Flipper at the fort while his company served in the field. The arrival of Lt. Charles E. Nordstrom made matters worse for Flipper. With a fine new buggy, Nordstrom lured Miss Dwyer away from the horseback rides which had so uplifted the lieutenant's morale. The two rivals shared a set of quarters, but rarely spoke to one another. Ostracized by his fellow officers, Flipper found companions among the townspeople, a move Shafter resented. Friends warned Flipper that Shafter and his minions were out to get him. "Never did a man walk the path of uprighteousness straighter than I did," Flipper later remembered, "but the trap was cunningly laid and I was sacrificed." [75]

|

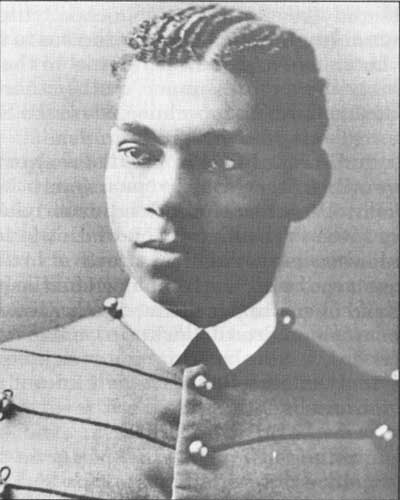

| Fig. 8:27. Lt. Henry Flipper. Photograph from Fort Davis Archives, AA-47. |

In August 1881 Flipper was arrested for misappropriating army funds and concealing a discrepancy of about $2,400 in his commissary accounts. Three officers searched the lieutenant's quarters. There they noted three Mexicans—two men and a woman—in his back room, an incident they believed peculiar. Closer investigation revealed that one of Flipper's two servants, Lucy Smith, stored her clothes in the locked trunk in which Flipper kept the commissary funds and thus enjoyed free access to the key. Shafter found $2,800 in uncashed checks from military personnel to the commissary on her person at the time of Flipper's arrest. Flipper, on the other hand, maintained that he had concealed the shortfall only because he feared Shafter was out to ruin him. [76]

Realizing that Flipper might go to prison for his indiscretion, local residents took up a collection to repay his debt to the commissary fund. About a thousand dollars was donated outright; the balance came in the form of loans. Ironically, Shafter, who pitched in one hundred dollars to the loan fund, was the only officer to contribute. A ten-man court-martial board began meeting September 17 at the post chapel, where a stream of witnesses soon attested to Flipper's good character. Flipper claimed that he never suspected any deficiency greater than several hundred dollars until mid-August. Upon discovering the total to be much higher, he set about making good the missing funds. But because of his "peculiar situation" and Shafter's well-known severity, Flipper decided to "endeavor to work out the problem alone." [77]

Flipper's plan went awry when projected royalties from his autobiography were delayed. His bank balance could not cover a check he wrote to make up the difference. Pleading for leniency, his lawyer, Capt. Merritt Barber, acknowledged Flipper's inexperience and carelessness. Still, his decision to cover up the matter seemed perfectly logical: "He has had no one to turn to for counsel or sympathy. Is it strange then that when he found himself confronted with a mystery he could not solve, he should hide it in his own breast and endeavor to work out the problem alone as he had been compelled to do all the other problems of his life?" [78]

Unable to prove Flipper guilty of embezzlement, the court-martial instead dismissed him from the service for "conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman." Despite pleas for clemency from regimental commander Benjamin Grierson and Judge Advocate Gen. David G. Swaim, Flipper was forced out of the army. The young man went on to become a successful mining engineer, but spent much of the rest of his life in a futile effort to clear his name. [79]

The Flipper case symbolized white attitudes toward black advancement after the Civil War. Many white colleagues resented and feared both Flipper's commission and his friendships with nonwhite civilians. A sloppy accountant, the lieutenant was a poor choice as commissary officer. But such failings were scarcely unique to Henry Flipper. He deserved a sharp reprimand; still, the severity of his punishment suggests that racism dictated the final decision. A white officer would not typically have received such a stiff penalty for a comparable transgression. The harsh judgment also suggests the wide acceptance of the myth of black inferiority. Despite the excellent record compiled by its black troops, this myth would not be shattered at the post along the Limpia. [80]

The racial problems only exacerbated the age-old problems of discipline within any military force. In the postbellum army, overly harsh disciplinary measures tended to ruin morale and encourage desertion. Persnickety officers risked gaining the unflattering sobriquet of "dust inspector" and losing the respect of their men. Virtually every action in the day, from getting out of bed to performing fatigue duty to drilling to inspection to going to bed, risked breaking one of the articles of war, slightly altered during the Civil War but substantially unchanged until 1890. As was the case before 1861, noncommissioned personnel or officers thus dealt individually with a thousand petty transgressions. [81]

Of those formally accused of breaking official regulations, violation of Article 62—"conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline"—proved most common. Assorted minor offenses included neglect of duty, insubordination, profanity, fighting, and petty theft. For such misconduct garrison courts-martial meted out small fines, short terms in the guard house, or took away privileges. The 1878 case of Horace Brown, K Troop, Tenth Cavalry, is typical. A garrison court-martial found Brown guilty of "failing and neglecting to wash the Dispensary floor, . . . and when asked why he had neglected to do, did reply 'God damn you, go to hell.'" For this transgression, Brown paid a five-dollar fine. Found guilty on another Article 62 charge, 1st Sgt. Thomas H. Allsup, a splendid combat veteran, was reduced to the ranks. [82]

Punishment for more serious crimes at Fort Davis tended to be milder than at other posts; still, military justice could be brutally cruel. Congress had abolished flogging in 1861, but allowable punishments called for prisoners to be tied up and spread eagled, to carry heavy logs, or to lug about a heavy ball and chain. Some officers like Lt. Charles J. Crane seemed reluctant to hand down such sentences. But when faced with a near mutiny while escorting his men via railroad from Fort Davis to Fort Sill, Indian Territory, even Crane resorted to draconian measures. He ordered the drunken ringleader bound and gagged. "My method of quieting the man was the best under the circumstances, as was proven at the time and on the spot," explained Crane, "but I would not advise it as something to be practiced lightly and without feeling very sure." [83]

Violent crimes also disrupted military life, with a spectacular example occurring on June 13, 1878. That morning Sgt. Moses Marshall, Twenty-fifth Infantry, stormed into the barracks cursing an unidentified man for insulting his wife. One witness speculated that Marshall had been drinking. About two o'clock that afternoon, Marshall and Cpl. Richard Robinson exchanged "pretty rough words." Half an hour later, Marshall entered the barracks and shot Robinson through the head with his Springfield rifle. As the startled enlisted men came in to investigate, they asked Marshall what had happened. "Oh, nothing, only I have killed Corporal Robinson," replied Marshall coolly, who followed with a series of diatribes against any man who dared impugn his mother's reputation. A criminal jury quickly found Robinson guilty of "a cool, wilful [sic], and deliberate murder." [84]

As had been the case before the Civil War, many of these crimes were related to the abuse of alcohol. One chaplain rued that "drinking of the vilest kind of whiskey, and gambling, I am sorry to say, seem inevitably on the increase in the command." It seemed as if nothing could dam the tide of alcoholic beverages. The paltry fines assessed for inebriation were a feeble deterrent. In 1881 Pres. Rutherford B. Hayes forbade the sale of whiskey at military posts; one student has concluded, however, that a "marked increase" in knife and gunshot wounds occurred after the temperance order. [85]

Loneliness proved a common problem—"tis naught but a deserted Post," wrote one surgeon whose wife had gone back east. Maj. Napoleon B. McLaughlen, Tenth Cavalry, seemed a particularly tragic case. In 1880 a visitor described the major as "very kind, and seemed to enjoy having people about him." At one of the Murphy parties, McLaughlen "did his duty too on the 'light fantastic.'" But the journalist concluded that "his life is a sad and pathetic one; having much sorrow and little pleasure." McLaughlen subsequently found himself committed to an insane asylum. [86]

Although all officers did not consume large quantities of alcohol, liquid spirits proved the undoing of many. Former post commander James G. Birney died of "acute inflammation of the stomach produced by intemperance." Surgeons frequently administered to those who imbibed too freely. Commanding officer Frank D. Baldwin called upon surgeon John V. Lauderdale's services after consuming "too much lobster and beer." And in 1889 Lauderdale noted that he hospitalized one alcoholic officer and feared that another would soon require similar treatment. [87]

In 1871 Congress reduced the pay of enlisted men to prewar levels—ranging from thirteen dollars per month for a private to twenty-two dollars for first sergeants. The first reenlistment added two dollars to the regular pay; each subsequent reenlistment was rewarded with another dollar. Desertion rates promptly sky-rocketed from just over nine percent to nearly thirty-three percent. The resulting outcry from army officials convinced Congress to add longevity supplements of one dollar per month in each of the soldier's third, fourth, and fifth years of enlistment. The army would retain the bonus until the soldier's honorable discharge as a deterrent to desertion or misconduct. [88]

Many soldiers worked on extra duty, thus garnering extra income. Through most of the period regulations established rates at twenty cents per day for laborers and thirty-five cents per day for skilled mechanics. Even when considering that the army added room, board, and uniform allotments, the pay for skilled craftsmen scarcely equaled that of local civilians. Assuming work was available, a private working as a carpenter could expect $23.50 a month ($13 base pay plus $10.50 extra duty pay). The civilian carpenter, on the other hand, earned $60 per month, often with a government ration included. Civil blacksmiths, wheelwrights, and saddlers received slightly more. This reflects general trends—army pay for unskilled workers seemed competitive, even lucrative, when compared to civil life; a skilled worker, however, clearly lost money by joining the army. [89]

Irregular visits of army paymasters proved a chronic problem. Official guidelines called for the men to be paid at least every two months, but most frontier soldiers received their money less frequently. The practice thus left disgruntled troopers without any cash on hand for long periods of time. The robbery of the government paymaster bound for forts Davis and Stockton in the spring of 1883 only added to their woes. But when he did come, the paymaster immediately rejuvenated life on the post. Creditors flocked to the area to collect their debts; hucksters hawked their wares; gamblers tempted the soldiers with their games of chance; dram shops did a booming business.

During the 1870s the daily ration included 20 ounces of fresh beef, 12 ounces of bacon, or 14 ounces of dried fish. In addition, each soldier was allotted 18 ounces of soft bread, 2.4 ounces of beans, 2.4 ounces of sugar, .6 ounces of salt, and 1.28 ounces of roasted coffee beans. Actual costs varied by region—on a national level, the price for a ration fell from just over 23 cents in 1868 to 16.77 cents in 1874. Cooks and subsistence officers able to manipulate standard provisions introduced rice, hominy, sauerkraut, and cheese. In the field wild game and vegetables supplemented the regular ration. Robert Grierson described "prairie cabbage," which from his description seemed to be the mescal plant, as tasting "like boiled cabbage would cooked up with bacon." But the lack of vegetables led one army surgeon to conclude that the "ration is not only deficient in quantity, but that it does not contain the elements necessary to preserve the health of the soldier." [90]

Troubled by such concerns, Joseph R. Smith, medical director of the Department of Texas, compiled an extensive study of the army ration in 1880. He found that in order to secure a balanced diet for his command, the company commander (or, more often, a junior officer, first sergeant, or cook) sold or bartered surplus rations for vegetables. Up to one third of the bread allowance was commonly sold to private citizens. The resulting proceeds built up post, regimental, and company funds, which were in turn used to support schools or the library, supplement the mess, buy garden seeds and utensils, or provide miscellaneous comforts approved by the company commander. Smith advocated increasing the ration; food purchases ate up too many of the extra funds. By reducing amounts of salted meat, sugar, and coffee, the government could offer more potatoes, fresh meat, and flour to improve health and give the companies additional bread for barter. [91]

The commissary general of subsistence, Robert Macfeely, believed that Smith's proposed increases were too expensive. Instead, Macfeely demanded that cooks be trained and given extra pay. The current practice of detailing cooks from the ranks for ten-day stints could prove disastrous. Even if the cooks made palatable food, the troops' dependence upon his ability to manipulate savings from their daily ration to provide for a post or company fund made a system of trial and error impractical. A stingy Congress, however, refused to provide for permanent cooks until 1898. [92]

At Fort Davis Lieutenant Colonel Shafter inherited a particularly difficult situation regarding food in 1871. Nearly one thousand dollars of improper assessments against private merchants doing business on the military reservation had been refunded, leaving the post fund nearly penniless. As the balance was again built up, the army introduced fruits and vegetables preserved by the "Allen process" to Fort Davis. Enlisted men flatly refused to purchase the experimental foods; on the other hand, officers found the onions, corn, potatoes apples, and peaches superior to canned products. The commissioned personnel acknowledged the inferior quality of the cranberries and tomatoes. Lacking funds to buy better food, the garrison's options were thus severely limited. [93]

Among products stocked by the subsistence office and sold to the troops at cost, tobacco proved particularly popular. Butter, dried fruits, canned vegetables, crackers, lard, and yeast were other common offerings. More refined palates found hams, oysters, syrup, and jelly usually available. Canned lima beans, on the other hand, simply collected dust—inspectors found 825 cans of the slow moving beans on inventory in April 1876. A board of survey had destroyed 848 cans of lima beans just a year earlier. [94]

Inadequate storage facilities and lax inspection hampered efforts to improve Davis's food supply. An 1875 board found "that old and an inferior quality of stores are often sent to this post . . . and others are packed so badly that in their arrival here are totally unfit for issue." Within the past 6 months, boards had destroyed 2,357 pounds of hard bread, 900 pounds of hominy, 384 pounds of hay, 151 pounds of crackers, 97 gallons of molasses, 208 pounds of vermicelli, 256 pounds of macaroni, 588 cans of condensed milk, 9 heads of cheese, 49 hams, 154 cans of sardines, 20 gallons of onions, 198 cans of sweet potatoes, 120 pounds of creamed tartar, 143 cans of onions, 508 pounds of lard, and the aforementioned 848 cams of the dreaded lima beans. Although repairs were frequent, an inspector still found the commissary storehouse "too small," with inadequate ventilation and a poor cellar in 1881. [95]

War Department officials counted on post gardens to augment the regular ration. The Fort Davis garrison's effort did fairly well except in 1873, when grasshoppers destroyed virtually the entire crop. Potatoes seemed to be about the only vegetable not grown successfully. By 1879 an older garden in Limpia Canyon was also under cultivation. Post commanders detailed troops to the latter site for up to six weeks at a time. Bad weather hampered production in the early 1880s; in 1883 and 1884, animals belonging to Diedrick Dutchover ravaged much of the produce. [96]

When properly collected and spent, post and company funds provided needed supplements to regular army issues. A list of equipment purchased in October and November 1885 serves as an instructive example. During this two-month period, the post fund provided 200 pounds of salt, 4 pounds of hops, 5 cans of lard, 1,225 pounds of potatoes, 1 can of mineral oil, 2 pounds of candles, and 38 books. This was in addition to the materials already on hand: 24 bake pans, a dough trough, a strainer and tin kettle, a sieve, 14 benches, a work bench, a clock, a composing stick, 14 boxes of crayons, 6 slate pencil boxes, 34 library files, 2 maps, 2 sets of checkers, chess pieces, dominoes, a printing press, 6 hoes, a plow, a rake, two watering pots, a dust brush, and an organ. [97]

|

| Fig. 8:28. Miscellaneous noncommissioned officers and their families. Those pictured (left to right): Cpl. Robert Dickson; child of Sgt. Thomas H. Forsyth; Beulah Rolehouse (niece of Forsyth); Sgt. John Wylie [standing]; Sergeant McHale; Hospital Steward Appel; Clara Wharton Forsyth; Sgt. Thomas H. Forsyth; Forsyth child; Sgt. G. Fahlbush (ca. 1888-89). Photograph from Fort Davis Archives, AB-17. |

On the cultural front, soldiers at Fort Davis enjoyed access to fairly substantial libraries. Attendance at the reading room averaged a healthy 67 of the 343 enlisted men on post in January 1881. Most reading material was purchased using post and War Department funds; during the later 1870s Chaplain George Mullins secured supplementary magazines and newspapers from the New York City and Chicago Young Men's Christian Associations. By 1882 periodicals included Scribner's Magazine, United Service, Harper's Magazine, Appleton's, Popular Science, The North American Review, Frank Leslie's Illustrated, London Graphic, Nation Army and Navy Register, and the Washington Sunday Herald. Daily newspapers from New York, St. Louis, Chicago, Boston, Houston, San Antonio, and Philadelphia were also available. Three years later the post boasted 1,660 books. [98]

Individual regiments also sponsored their own collections. As Fort Davis served as headquarters to several regiments over the years, its garrison benefited from such libraries. The best was undoubtedly that of the Twenty-fifth Infantry, which boasted some twelve hundred volumes. Housed in the adjutant's office, the collection nearly burned at the hands of an arsonist in December 1873. Only energetic action by the troops saved the books. [99]

Regimental bands had long been an army institution. After the Civil War, however, Congress halted appropriations for the musical groups, save for a single chief musician per regiment. It did allow sixteen (later twenty) privates and a sergeant to be detached from their units to form a band. The troops would have to provide their own music and instruments. Congress "has done a wrong thing," protested one officer, and most regiments kept their musicians by private subscription. In addition to playing at parties and hops, the band serenaded the garrison at inspection, roll call, and special military occasions. [100]