|

Fort Laramie and the Forty-Niners

|

|

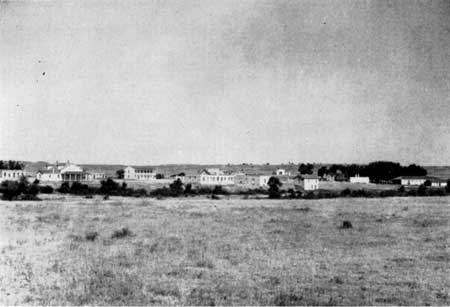

Section I One of the most historic spots in the Trans-Mississippi West lies on the tongue of land formed by the junction of the Laramie and North Platte Rivers, in eastern Wyoming. Here, at Fort Laramie National Monument, administered by the National Park Service, lie the impressive remains of a military post which, for over forty years, represented the might of the United States Government on the Great Plains frontier. Born dramatically in 1849, the year of the epic gold rush to California, within the shaky walls of an old adobe trading post, the event witnessed by a motley horde of emigrants, Indians, and squaw men, Fort Laramie's star ascended amid exciting and violent scenes of the migrations, the Mormon Rebellion, and the Sioux-Cheyenne Wars, declined with the advent of the Union Pacific Railroad, the Black Hills stage line, and the open-range cattle industry, and died tranquilly when the first wave of homesteaders reached Wyoming. Laramie's Fork was historic ground long before soldiers were stationed there. Before Fort Laramie were the trading posts of Fort John, Fort Platte, and Fort William. Before these, even, were many camps and trading sessions and savage councils. The very name of "Laramie" harks back to a tradition, of uncertain date, that an early Canadian trapper, one Jacques La Raimee, was killed by Indians and his body thrown in this stream. The natural attractions of Laramie's Fork were noted as early as 1812 by Robert Stuart and his companions, travellers en route from Fort Astoria to the States, the first white men to follow the Platte Route.

They were noted also by Warren A. Ferris, fur-trapper of the American Fur Company, in 1830:

The setting likewise engaged the attention of Captain Bonneville, heading a trapping expedition to the mountains, in 1832:

Laramie Fork itself drained a rich trapping territory in the early days, and many licenses were issued "to trade at Laremais' Point," near the foot of Laramie Peak, which region was then called "the Black Hills." [4] Zenas Leonard's journal of 1832 paints a graphic picture of a trapper's conclave here, preliminary to a general movement toward the Pierre's Hole rendezvous in the mountains, [5] while Charles Larpenteur, in 1833, records another encampment:

The strategic and commercial advantages of the location on Laramie's Fork, at the intersection of the Great Platte Route to the mountains and the Trappers Trail south to Taos, were at once apparent to William Sublette and Robert Campbell in 1834, when they paused here en route to trappers' rendezvous at Ham's Fork of the Green, to launch the construction of log-stockaded Fort William. The event is simply recorded by William Anderson:

In 1835 the enterprising partners sold their interest in Fort William to James Bridger, Thomas Fitzpatrick, and others, who in turn released it to the Western Department of the monopolistic American Fur Company (which, after 1838, assumed the official title of Pierre Chouteau, Jr. and Company). In July 1835 Samuel Parker, one of the first missionaries up the Trail, arrived in the company of fur traders at "the fort of the Black Hills." He writes:

At this time a horde of Ogalala Sioux came into the Fort to trade. Parker and his aide, Marcus Whitman, met in council with the chiefs, and then were treated to a buffalo dance. Continues Parker, "I cannot say I was much amused to see how well they could imitate brute beasts, while ignorant of God and salvation . . . what will become of their immortal spirits?" [8] In 1836 the wives of Marcus Whitman and Rev. H. H. Spalding, first white women to follow the Oregon Trail, accepted the meagre hospitality of the Fort. Particularly noteworthy were the chairs, with buffalo skin bottoms, a welcome contrast to relentless saddles and wagon-boxes. [9] The only known pictures of Fort William were made in 1837 by A. J. Miller, an artist in the entourage of Sir William Drummond Stewart. Here, in Miller's own notes, is the traditional log post,

In 1840 the illustrious Father De Smet paused at this "Fort la Ramee," where he found some forty lodges of the Cheyennes, "polite, cleanly and decent in their manners. . . . The head chiefs of this village invited me to a feast, and put me through all the ceremonies of the calumet." [11] In the fall of that year, or the spring of the following, a rival establishment appeared, on the nearby banks of the North Platte. This was adobe-walled Fort Platte, built by Lancaster P. Lupton, veteran of the South Platte trade, and taken over in 1842 by Sybille, Adams and Company. This development, coupled with the rotting condition of Fort William, prompted the Chouteau interests to build a new adobe fort of their own, again on the banks of the Laramie, officially christened Fort John, but popularly dubbed "Fort Laramie." The decade of the 1840's was characterized by bitter rivalry among the trading companies, the coming of the first emigrants to Oregon and Utah, and the appearance of many notable travellers. The open traffic in firewater characterized the degenerate condition of the fur trade at this time. Reports Rufus B. Sage, in November 1841:

Coincident with the construction of the rival forts, in 1841, came the Bidwell expedition, usually conceded to be the first bona fide covered wagon emigrants. In July 1842 Fort John was visited by Lt. John C. Fremont, on his first exploring expedition to the Rocky Mountains. Of this post he writes:

The "cow column," the first great migration to Oregon, consisting of near 1,000 souls, passed by in 1843. Thereafter, the white-topped emigrant wagons became a familiar sight in May and June of each year. Many travellers have left their impressions of the clear swift-flowing Laramie, the neat white-walled fort, the frequent Indian tepee villages nearby. In 1843, writes Johnston: "The occupants of the fort, who have been long there, being mostly French and having married wives of the Sioux, do not now apprehend any danger." [14] In 1844, John Minto records: "We had a beautiful camp on the bank of the Laramie, and both weather and scene were delightful. The moon, I think, must have been near the full . . . at all events we leveled off a space and one man played the fiddle and we danced into the night." [15] The year 1845 was a banner one for Oregon-bound emigrants, who numbered upwards of 3,000. The classic account of that year is Joel Palmer's journal, which vividly describes the two rival posts at the Junction of the Platte and the Laramie, and a great feast given by the emigrants on behalf of the multitude of Sioux Indians there assembled. [16] Brotherly love also prevailed later that same year when five heavily armed companies of the First Dragoons, led by Col. Stephen W. Kearny, arrived and encamped in the vicinity. At a formal council the savages were diplomatically reminded of the might and beneficence of the Great White Father. [17] Francis Parkman in his famous book, The Oregon Trail, has left an indelible impression of the situation at Fort Laramie in 1846, whence he travelled in the role of historian and ethnologist, sojourning that summer in the region in company with Oglala Sioux. Less well known than the book is the recently published journal, in which he notes the passing of Fort Platte, and the appearance of the ill-starred Donner party:

In 1847 the Mormon Pioneers made their appearance here en route to the Promised Land. They investigated the place thoroughly, making detailed measurements of Fort Laramie and the abandoned Fort Platte, the latter being near their crossing of the Platte River. [19] The Mormons developed the trail on the north side of the Platte, commencing at Council Bluffs, and as the "Mormon Trail" it has always been distinguished from the main Oregon-California Trail, south of the Platte. At Fort Laramie the two at first joined, although in later years the Mormon Trail continued westward without crossing at the Fort. In 1847 there was a sizeable migration to Oregon and California as well as Utah, but in 1848 the "Saints" had the field pretty much to themselves. It was also in 1848, as every school boy knows, that James Marshall discovered gold at the millrace near Sutter's Fort on the Sacramento River, California Territory, thus touching off the epic California gold rush. As the year 1849 dawned, the craze was beginning to sweep the country. There were not a fraction enough ships to provide passage for all those who wanted to get to the mines, by way of Cape Horn. Thousands converged on the Missouri border towns. Wagons, oxen, mules, gear of all kinds, commanded premium prices. It was clear that something was about to happen to "the Great American Desert" and the adobe-walled trading post on the Laramie. | |||

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

Fort Laramie and the Forty-Niners ©1949, Rocky Mountain Nature Association mattess/chap1.htm — 10-Mar-2003 | ||